Abstract

More than 80% of patients with Crohn's disease (CD) will require surgical intervention during their lifetime, with high rates of anastomotic recurrence and stenosis necessitating repeat surgery. Current data show that pharmacotherapy has not significantly improved the natural history of postoperative clinical and surgical recurrence of CD. In 2003, antimesenteric hand-sewn functional end-to-end (Kono-S) anastomosis was first performed in Japan. This technique has yielded very desirable outcomes in terms of reducing the incidence of anastomotic surgical recurrence. The most recent follow-up of these patients showed that very few had developed surgical recurrence. This new approach is superior to stapled functional end-to-end anastomosis because the stumps are sutured together to create a stabilizing structure (a “supporting column”), serving as a supportive backbone of the anastomosis to help prevent distortion of the anastomotic lumen due to disease recurrence and subsequent clinical symptoms. This technique requires careful mesenteric excision for optimal preservation of the blood supply and innervation. It also results in a very wide anastomotic lumen on the antimesenteric side. The Kono-S technique has shown efficacy in preventing surgical recurrence and the potential to become the new standard of care for intestinal CD.

Keywords: stapled functional end-to-end anastomosis, supporting column, surgical recurrence, Crohn’s disease

More than 1.5 million patients have Crohn's disease (CD) worldwide, with a recent significant increase in Asia. The incidence of CD in Japan has increased dramatically during the last two decades, and the nationwide population of patients with CD is currently approaching 50,000. Despite the advances in medical therapy, ∼80% of patients with CD will require intestinal resection for complications related to stricturing or penetrating disease during their lifetime, with high postoperative rates of anastomotic recurrence and stenosis necessitating repeat surgery. 1 2 3 4 In one study of patients treated with surgical anastomosis, endoscopic recurrence at 6 months was observed in up to 60% of those who underwent ileocolic resection, and 20% to 30% of patients who underwent surgery required a second surgery within 5 years. 3 Anastomosis and recurrence are intrinsically related. Postoperative recurrence typically occurs at the anastomotic site or in the neoterminal ileum in patients with previous ileal involvement. 5 Although several studies have shown the efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents in preventing postoperative endoscopic recurrence rates in patients with CD, 6 a recent prospective randomized controlled study showed that the clinical recurrence rates were not different between the infliximab group and the placebo group. 7 Therefore, the ability of anti-TNF agents to reduce clinical recurrence and surgical recurrence has not yet been determined. 8 Moreover, no surgical strategies have been developed to prevent postoperative surgical recurrence. 9 10 Therefore, efforts should be made to optimize surgical techniques and offer the best possible operative treatment to the right patient at the right time.

In September 2003, Kono et al began using their unique surgical technique (Kono-S anastomosis) to prevent anastomotic strictures in patients with CD at the Asahikawa Medical University Hospital in Hokkaido, Japan.

Kono et al first reported the outcomes of this novel technique in a comparison between 69 patients who underwent Kono-S anastomosis and 73 patients who underwent conventional anastomosis (hand-sewn end-to-end, hand-sewn side-to-side, or stapled functional end-to-end [FEE]). Surgical recurrence was significantly less likely with this new anastomosis technique (0 vs. 15%, p = 0.0013). 11 Since 2010, Kono-S anastomosis has been adopted in 23 leading medical centers, including 18 university hospitals in Japan. 12 13 14 In May 2010, Kono-S anastomosis was introduced at the University of Chicago and subsequently at the University of Washington, Weill Cornell Medical Center, and University of North Carolina. Fichera et al evaluated 44 patients who had undergone 46 Kono-S anastomoses and reported no surgical recurrences during the study period. 15 In 2016, an international multicenter study conducted at five university hospitals (4 in Japan and 1 in the United States) analyzed 187 patients who had undergone Kono-S anastomosis for CD with a median follow-up of 60 months. 13 In the Japanese cohort (144 patients), surgical recurrence occurred in only two patients, with a 5-year cumulative surgical recurrence rate of 1.7% during a median follow-up of 65 months. In the United States group (43 patients), no surgical recurrences occurred during the follow-up period of 32 months. This excellent result suggests that Kono-S anastomosis appears to be safe and effective in reducing the risk of surgical recurrence in patients with CD. Multicenter prospective randomized trials comparing Kono-S anastomosis with conventional side-to-side anastomosis are currently underway in the United States (NCT03256240) and Europe (NCT02631967). 10

We outlined the standard Kono-S anastomosis procedure, adopted at the Second International Consensus Conference on Kono-S Anastomosis held in October 2015 in Nagoya, Japan. 16 We also described the theoretical background of this procedure and the fundamental differences between Kono-S and stapled FEE anastomosis as well as other conventional anastomotic techniques.

Kono-S Anastomosis Procedure

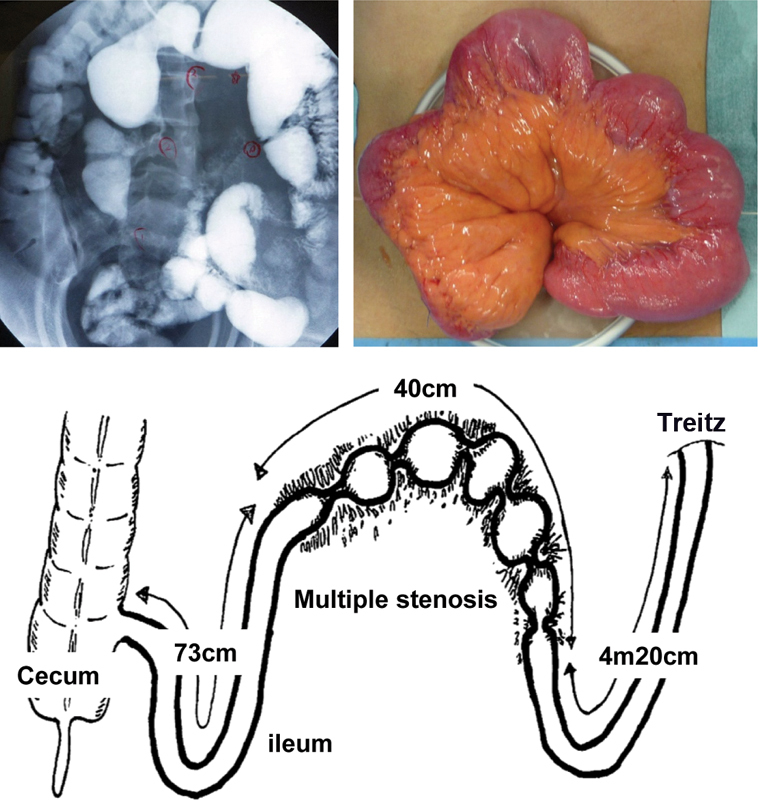

The Kono-S anastomosis technique is illustrated in Fig. 1 using the example of multiple ileal stenosis, one of the most common types of CD lesions in Japan. 13

Fig. 1.

Multiple ileal stenoses in a patient with Crohn's disease. A 36-year-old man had Crohn's disease complicated by multiple stenoses in the small intestine. Six strictures spanning 40 cm were located within the distal 73 cm of the terminal ileum.

Confirmation of the Lesion

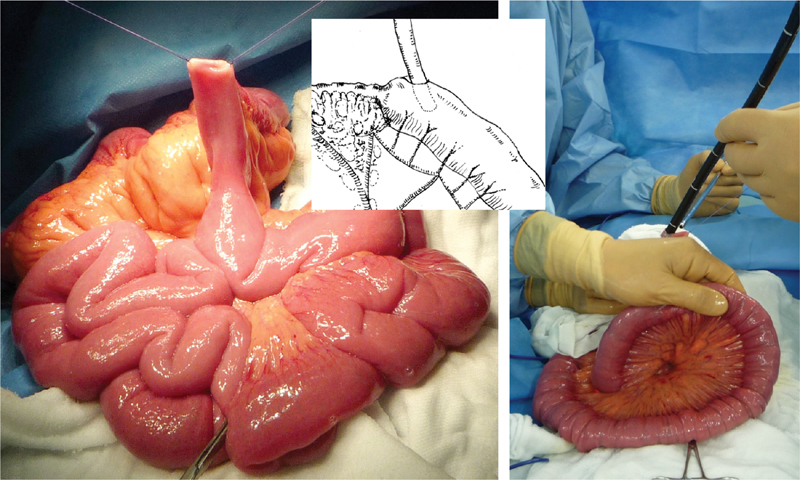

Surgical success is dependent upon a detailed preoperative evaluation of the lesions and other parts of the intestinal tract, which are often compromised by adhesions, multiple disease foci, and other abnormalities. Whether using the open or laparoscopic approach, the surgeon must carefully trace and observe the patient's small bowel starting from the ligament of Treitz ( Fig. 1 ). Surgical lysis of adhesions may be necessary for mobilization of the gastrointestinal tract. The surgeon determines the length of the small intestine as well as the extent of the disease using a sterile tape measure or other appropriate tools ( Fig. 1 ). Before making the final decision on the surgical procedure intraoperatively, the surgeon may need to endoscopically observe the identified lesions and the future remnant tract segments to ensure that no active lesions were missed in the preoperative assessment ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative endoscopy. The whole bowel is carefully inspected for diseased segments using an endoscope via an enterotomy placed at the stenotic site. Intraoperative endoscopy is performed by a gastroenterologist when unexpected incidental surgical findings are noted upon exploration.

Determination of Anastomosis Location and Resection Margin

Attention must be paid to exclude ulcers and other active lesions from the anastomotic site. Although the presence of inactive lesions may be permitted, the surgeon should ideally select an area completely free of disease, keeping in mind that the bowel must be spared to the maximum extent possible. A 2-cm margin proximal and distal to the edge of the macroscopically visible diseased bowel is recommended. 17

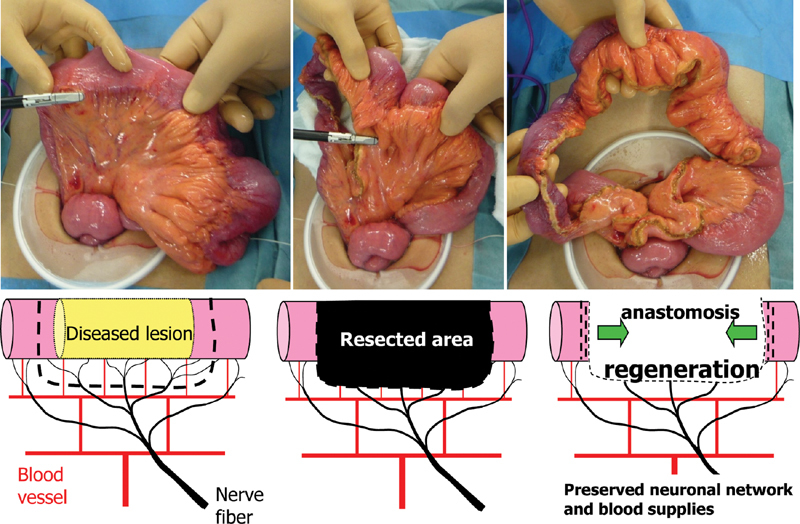

Division of Mesentery for Maximum Preservation of Vascularization and Innervation

CD is a chronic, recurring transmural inflammatory process that also damages the intrinsic intestinal nervous system. The submucosal plexus is particularly susceptible to damage because of its location and morphology. Regeneration of nerve fibers takes much longer (years) than mucosal healing (weeks). Therefore, even after mucosal healing is complete, neuronal regeneration is incomplete. In fact, the regional total intestinal and mucosal–submucosal blood flow in patients with CD is reduced to half than that in healthy individuals, probably due to reduced levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide, a potent vasodilator, in the submucosal plexus. 18 19 Poor mucosal blood flow contributes to intestinal ulceration in patients with various clinical conditions such as perforation, fistula, and excess fibrosis, which causes intestinal stenosis.

During peripheral nerve regeneration, it is difficult for nerves to regenerate across large gaps because nerve regeneration cannot be sustained for long periods of time. Therefore, after reviewing the conventional method of dividing the mesentery where lymphovascular vessels and nerves branch into the intestinal wall, we decided to adopt the herein-described new approach.

A fan-shaped portion of the mesentery spanning the proximal and distal resection margins is usually resected to allow for the removal of lymph nodes. However, this procedure likely delays postoperative neural regeneration because the nerves are severed relatively proximally. The nerves should be divided as close to the intestinal wall as possible to allow for early neural regeneration at the anastomotic site, which will contribute to maintenance of its blood supply ( Fig. 3 ). Postoperative decreases in intestinal blood flow may contribute to anastomotic recurrence. 18 Retaining as much of the mesentery as possible is critical for optimizing the blood supply to the anastomosis.

Fig. 3.

Mesenteric incision line. The mesentery is divided using a tissue-sealing device close to the intestinal wall to preserve the vascularization and innervation.

The use of a tissue-sealing device is recommended wherever possible. Because mesenteric nerves and vessels are severed close to the intestinal wall, suture ligatures should be avoided to prevent surgical site infection. Hemostasis should be carefully performed in patients with mesenteric inflammation and hypertrophy, which may cause unexpected bleeding. The surgeon must take special care to leave the mesentery in the vicinity of the resection margins intact to the greatest extent possible for optimal postoperative reinnervation and revascularization of the anastomosis.

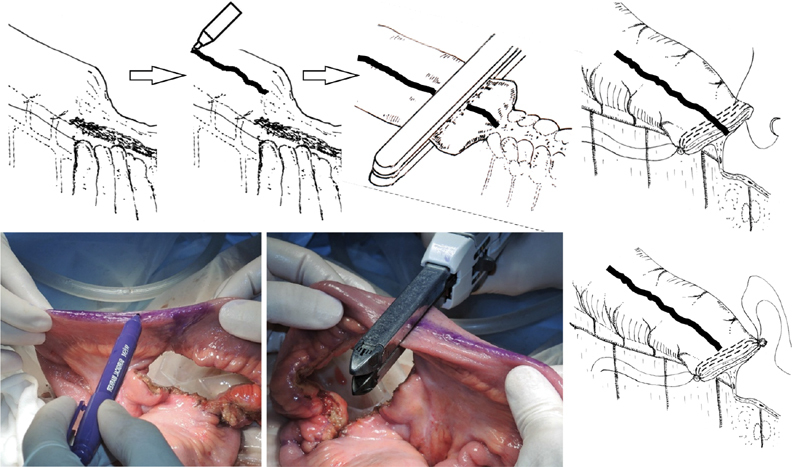

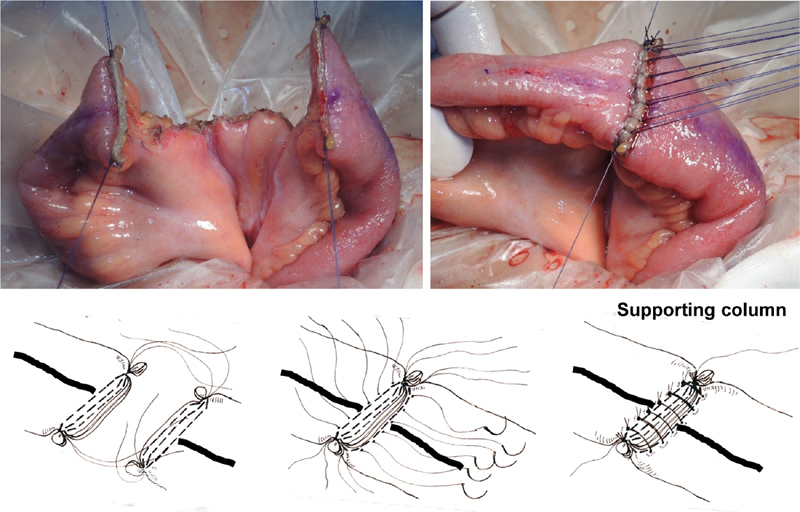

Creation of the Supporting Column

According to conventional anastomotic procedures, the bowel is divided with the long axis of the automatic cutting stapler parallel to the mesenteric plane. In our procedure, however, a two- or three-row automatic stapler is positioned perpendicular to the mesentery and longitudinal axis of the intestine so that the mesenteric plane will fall at the midpoint of the transverse staple line ( Fig. 4 ). Three-row staplers are preferable to two-row staplers with respect to the mechanical rigidity of the structure that will be created using the stapled ends. At this point, the surgeon may use a surgical skin marker to draw an ∼10-cm longitudinal line along the antimesenteric wall of both sides of the segment to be resected. These lines will serve as a useful indicator for the location and orientation of stapling ( Fig. 4 ). Experimental data suggest that the surgeon should wait a minimum of 2 minutes so that the intestinal tissue can be evenly compressed for secure staple closure ( Fig. 3 ). 20 It is advisable to wait 1 additional minute after firing the device, especially in patients with edematous tissue.

Fig. 4.

Transection of the intestinal tract and reinforcement of the corners of the staple line. Before dividing the bowel, a longitudinal line is drawn on the antimesenteric side. The bowel is divided transversely by placing the linear stapler perpendicular to the intestinal lumen, and the mesentery is located in the middle of the staple lines. The corners of the staple line are at risk of leakage and bleeding. Both corners of the staple lines are reinforced and imbricated. The sutures are tied together to construct the “supporting column.”

Automatic stapling may result in less effective closure at the corners ( Fig. 5 ). Consequently, the surgeon is advised to imbricate and reinforce the corners of the staple lines with absorbable sutures ( Fig. 5 ). The sutures used to reinforce the proximal and distal ends are tied together to approximate the corresponding corners of the stumps ( Fig. 5 ). The two staple lines are then sewn together with 3–0 or 4–0 absorbable sutures to construct a “supporting column,” a structure that helps to prevent mechanical deformation of the anastomosis ( Fig. 5 ). The supporting column will be located immediately behind the posterior wall of the anastomosis.

Fig. 5.

Creation of the supporting column. The suture threads used to reinforce the proximal and distal ends are tied together to create the supporting column. Adjustments are made to compensate for differences in stump sizes. The staple lines are securely sewn together using interrupted stitches. The supporting column helps to prevent distortion caused by relapse at the anastomotic site.

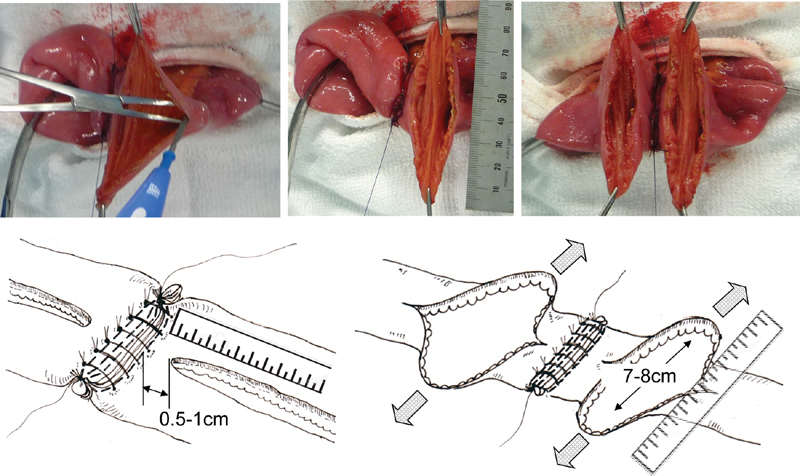

Construction of the Anastomosis

An incision is made along the longitudinal line marked on the antimesenteric wall, starting at a position 5 to 10 mm from the edge of the supporting column ( Fig. 6 ). If the incision starts within 5 mm of the supporting column, it will render the anastomotic procedure technically difficult and increase the risk of an insufficient blood supply. In contrast, if the incision starts more than 10 mm away from the supporting column, the mechanical reinforcement of the supporting column may be compromised. With the first assistant holding the incision open with forceps, the surgeon extends the longitudinal opening until a transverse lumen of 7 to 8 cm is created. Because the elasticity of the intestinal tract may vary significantly among patients with CD, the size of the opening must be accurately measured. The desired diameter of the anastomosis is 7 and 8 cm for the small and large intestine, respectively ( Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Creation of the anastomotic stoma. Antimesenteric longitudinal enterotomies are performed on each stump starting 5 to 10 mm away from the edge of the supporting column to maximize the effect of the supporting column on the anastomosis. The enterotomies are extended to allow a transverse lumen of 7 to 8 cm.

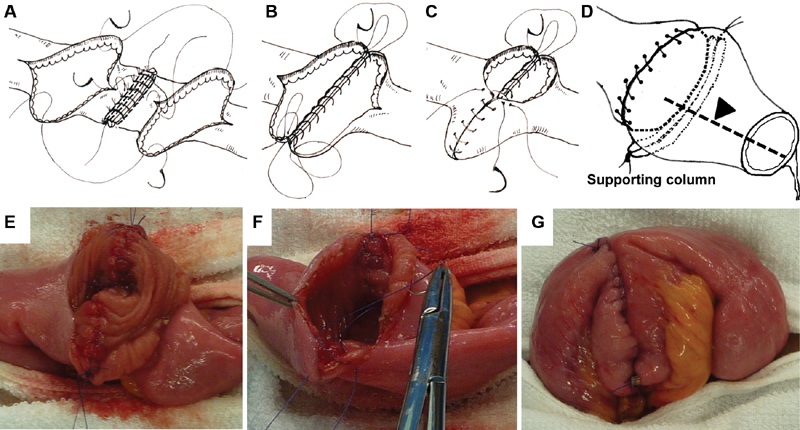

Either a vertical mattress or Albert suture pattern can be used to close the posterior wall. If the wall thickness of the two ends differs considerably, the vertical mattress suture technique is preferable. The proximal side of the distal lumen and the distal side of the proximal lumen are approximated by passing long sutures on nondetachable needles from the inside to the outside of one opening and from the outside to the inside of the other at the points most distal to the long axis of the intestine ( Fig. 7 ). Next, a short suture with a removable needle is used to join the midpoints of the anastomotic edges using the vertical mattress suture technique. Separate long sutures on nondetachable needles are used to close the posterior wall, starting from the center (i.e., proximal to the long axis) ( Fig. 7 ). These sutures are tied to the pre-existing long sutures with nondetachable needles, which are subsequently used to close the anterior wall. The supporting column will be located immediately behind the posterior wall of the anastomosis. The surgeon is advised to maintain a stitch distance of at least 7 mm for continuous sutures to ensure sufficient blood flow to the anastomosis. To ensure that the blood flow does not become limited, care must be taken to avoid pulling too hard on stretchable sutures when tying them.

Fig. 7.

Closure of the anastomotic stoma and completion of the Kono-S anastomosis. ( A ) Posterior wall stitches. Two vertical mattress sutures are placed: one at the point most distal to the long axis of the intestine and one at the center of the posterior edge. Another nondetachable suture is placed to close the pre-existing suture at the point most distal to the long axis and will be used for subsequent closure of the posterior wall. ( E ) Posterior wall closure. ( B ) The posterior wall sutures are used to close the anterior wall. ( C ) The surgeon sutures the proximal half of the anterior wall and ties another short suture with a detachable needle, which is placed at the center of the anastomosis. ( F ) Next, the surgeon closes the distal half of the anterior wall and ties this suture to the pre-existing suture. ( G ) Completion of the Kono-S anastomosis. ( D ) The arrowhead indicates the mesenteric side of the wall that is located at the center of the supporting column.

Either Gambee or layer-to-layer suturing can be used to close the anterior wall. The suture-carrying needles that were used to suture the posterior wall are passed through the edge of the stoma from the inside to the outside. On the side closer to the surgeon, the needle is passed through the ileum (distal end), and on the side farther from the surgeon, the needle is passed through the ileum (proximal end). The surgeon sutures the proximal half of the anastomotic edges and ties the suture ( Fig. 7 ). Another short suture with a detachable needle is placed and tied at the center of the anastomosis. The long suture with the nondetachable needle is left in place. Next, the surgeon closes the distal half of the stomal rim and ties this suture to the pre-existing suture ( Fig. 7 ). With this technique, the mesenteric attachment, a frequent site of pathological changes, ends up aligned with the midpoint of the supporting column ( Fig. 7 ). The supporting column provides rigid mechanical support that will prevent mechanical deformation and functional constriction of the lumen of the anastomosis.

Closure of the Mesenteric Defect and Coverage of the Anastomotic Structure

Closure of the mesentery is usually unnecessary because the mesentery is divided close to the intestinal wall. Because both ends of the supporting column extend beyond the edges of the anastomosed intestinal tract, the anastomotic structure should be covered by omentum or other appropriate fatty tissue to prevent intestinal adhesions. The surgeon may fix the anastomosis to the omentum or other fatty tissue placed over the anterior wall with a few stitches to relieve the anastomotic structure of excess mechanical tension. In such cases, the stitches should be placed along the short axis of the intestinal tract to prevent interference with the intestinal blood flow.

Potential Application

To form a wide anastomosis, the Kono-S technique requires healthy intestinal segments extending at least 10 cm both proximal and distal to the area to be resected. Consequently, this technique requires careful preoperative surgical planning and intraoperative decision making, especially when it is used to treat terminal ileal stenosis requiring preservation of the ileocecal valve, rectal stenosis, or multiple short skipped strictures. With this technique, the anastomosis is hand-sewn. Sewing by hand renders this technique technically difficult to perform using a totally laparoscopic approach.

One major advantage is that the supporting column can help to reduce mechanical tension on the anastomotic site. Therefore, the Kono-S technique is also suitable for ileorectal anastomoses or any types of anastomoses that are likely to sustain undue tension. This approach is also effective for anastomosing segments of significantly different calibers because incisions are made along the long axis of the intestinal tract, allowing similar lumen sizes to be created irrespective of diameter.

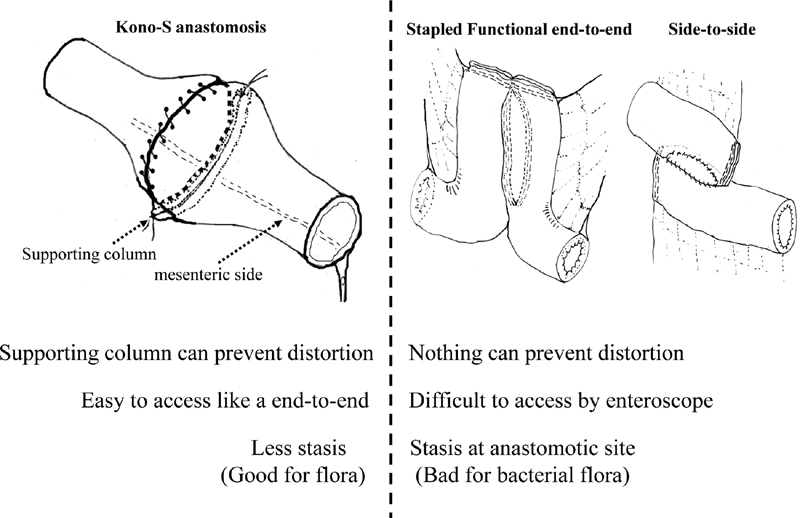

Theoretical Advantages of Kono-S Anastomosis

Supporting Column

In terms of the anatomic configuration of the anastomosis, one advantage of Kono-S anastomosis might be that the creation of a supporting column located immediately behind the posterior wall of the anastomosis prevents flow-limiting alterations of the fecal stream and maintains the orientation and large diameter of the anastomosis, especially on the mesenteric side.

The mesenteric side of the intestine is the initial site of macroscopic anastomotic recurrence. In Kono-S anastomosis, this side is positioned in the center of the posterior wall of the anastomosis; the supporting column fixes it in position, reinforcing the central portion of the posterior wall suture line from the outside. Therefore, even if macroscopic recurrence originates on the mesenteric side of the anastomosis, the supporting column can prevent distortion of the lumen of the anastomosis. In contrast, conventional anastomosis (end-to-end, side-to-side, and stapled FEE anastomosis) does not take into account this characteristic recurrence behavior at the anastomosis site.

Wide-Lumen Side-to-Side Anastomosis with the Heineke–Mikulicz Method

Theoretically, an end-to-end anastomosis could predispose to recurrence by creating a functional obstruction at the site of the anastomosis with proximal fecal stasis and a reduction in the blood supply to the proximal bowel due to increased intraluminal pressure.

Caprilli et al found that patients with end-to-end anastomoses had a more than threefold higher risk of recurrence than patients with other types of anastomosis. 21 Therefore, many surgeons have advocated the use of a wide-lumen side-to-side anastomosis (i.e., FEE anastomosis). A multicenter randomized controlled trial confirmed the lack of a significant difference in the perianastomotic recurrence and surgical recurrence rates between conventional end-to-end anastomosis and FEE anastomosis. 22 Fecal stasis after ileocolic anastomoses is likely to play a role in the pathogenesis of CD recurrence. 23

We compared the transporting time between Kono-S and FEE anastomosis models in animals. The Kono-S anastomosis model had a significantly shorter transporting time than the FEE anastomosis model (unpublished data). Although long incisions were made in both anastomoses, Kono-S anastomosis can diminish the dissected length of circular muscle using a short-axis anastomosis (Heineke–Mikulicz method). The length of circular muscle is associated with luminal transportation. The final shape of the Kono-S anastomosis is similar to an end-to-end anastomosis. Therefore, Kono-S anastomosis may not lead to proximal fecal stasis. In addition, the FEE anastomosis with a “trumpet” shape facilitates postoperative endoscopic observation and treatment (e.g., endoscopic balloon dilatation).

Preservation of Both Innervation and Blood Supply

A theoretical advantage of Kono-S anastomosis is preservation of both the innervation and blood supply, which are crucial for the healing process of the anastomosis and further prevention of endoscopic recurrence. The blood flow of the bowel is significantly decreased by more than 50% in patients with CD because of depletion of calcitonin gene-related peptide, a strong vasodilator; this has been observed in both patients with CD and animal models of CD. 18 The blood supply is likely to be even more severely compromised at the anastomotic site. Decreased blood flow is associated with recurrence at the anastomotic site. 24 When mobilizing the mesentery, we divide it as close as possible to the bowel wall to avoid any unnecessary denervation or devascularization, especially at the anastomotic site. The mesentery is completely excluded from the anastomotic lumen. Both primary and recurrent CD originates from the mesenteric side of the bowel wall. The mesenteric adipose tissue clearly plays a role in disease progression, 25 and excluding it from the anastomotic lumen has theoretical advantages.

The differences between Kono-S anastomosis and other anastomotic techniques are summarized in Fig. 8 .

Fig. 8.

Comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of hand-sewn and stapled functional end-to-end anastomoses.

Conclusion

Surgical recurrence of CD is common and most often noted at the anastomotic site after bowel resection. Anti-TNF therapy has not yet been proven to prevent surgical recurrence, and the cost–benefit ratio of such an approach remains to be determined. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to offer patients the operative treatment with the lowest proven risk of recurrence. Kono-S anastomosis is a safe and feasible anastomotic technique that is suitable for both the small and large intestine. Current data suggest that Kono-S anastomosis helps to reduce anastomotic surgical recurrence in patients with CD. The Kono-S procedure has the potential to become the standard of surgical treatment for CD in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was not supported by any grants or funding. No author has commercial associations or financial involvements that might pose a conflict of interest. The authors thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS, from Edanz Group ( www.edanzediting.com/ac ), for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Baumgart D C, Sandborn W J.Crohn's disease Lancet 2012380(9853):1590–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I, Beaugerie L, Afchain P, Tiret E, Gendre J P. Impact of the increasing use of immunosuppressants in Crohn's disease on the need for intestinal surgery. Gut. 2005;54(02):237–241. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.045294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fichera A, Schlottmann F, Krane M, Bernier G, Lange E. Role of surgery in the management of Crohn's disease. Curr Probl Surg. 2018;55(05):162–187. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nos P, Domenech E. Postoperative Crohn's disease recurrence: a practical approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(36):5540–5548. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terdiman J P. Prevention of postoperative recurrence in Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(06):616–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakouny Z, Yared F, El Rassy E. Comparative efficacy of anti-TNF therapies for the prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of prospective trials. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53(06):409–417. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Regueiro M, Strong S A, Ferrari L, Fichera A. Postoperative medical management of Crohn's disease: prevention and surveillance strategies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(08):1415–1420. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masaki T, Kishiki T, Kojima K, Asou N, Beniya A, Matsuoka H. Recent trends (2016-2017) in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2(04):282–288. doi: 10.1002/ags3.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto T, Watanabe T. Surgery for luminal Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(01):78–90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michelassi F. Crohn's recurrence after intestinal resection and anastomosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(07):1352–1353. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kono T, Ashida T, Ebisawa Y. A new antimesenteric functional end-to-end handsewn anastomosis: surgical prevention of anastomotic recurrence in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(05):586–592. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318208b90f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimada N, Ohge H, Kono T. Surgical recurrence at anastomotic site after bowel resection in Crohn's disease: comparison of Kono-S and end-to-end anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23(02):312–319. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-4012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kono T, Fichera A, Maeda K. Kono-S anastomosis for surgical prophylaxis of anastomotic recurrence in Crohn's disease: an International Multicenter Study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(04):783–790. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-3061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsuno H, Maeda K, Hanai T, Masumori K, Koide Y, Kono T. Novel antimesenteric functional end-to-end handsewn (Kono-S) anastomoses for Crohn's disease: a report of surgical procedure and short-term outcomes. Dig Surg. 2015;32(01):39–44. doi: 10.1159/000371857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fichera A, Zoccali M, Kono T. Antimesenteric functional end-to-end handsewn (Kono-S) anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(07):1412–1416. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1905-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kono T, Fichera A.Recurrent CD: Surgical Prophylaxis-Kono-S anastomosis Switzerland: Springer; 2015227–236.. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-14181-7 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fazio V W, Marchetti F, Church M.Effect of resection margins on the recurrence of Crohn's disease in the small bowel. A randomized controlled trial Ann Surg 199622404563–571., discussion 571–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr N D, Pullan B R, Schofield P F. Microvascular studies in non-specific inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1986;27(05):542–549. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.5.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hultén L, Lindhagen J, Lundgren O, Fasth S, Ahrén C. Regional intestinal blood flow in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1977;72(03):388–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakayama S, Hasegawa S, Nagayama S. The importance of precompression time for secure stapling with a linear stapler. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(07):2382–2386. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caprilli R, Corrao G, Taddei G, Tonelli F, Torchio P, Viscido A. Prognostic factors for postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio del Colon e del Retto (GISC) Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(03):335–341. doi: 10.1007/BF02049478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLeod R S, Wolff B G, Ross S, Parkes R, McKenzie M. Recurrence of Crohn's disease after ileocolic resection is not affected by anastomotic type: results of a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(05):919–927. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a4fa58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Haens G R, Geboes K, Peeters M, Baert F, Penninckx F, Rutgeerts P. Early lesions of recurrent Crohn's disease caused by infusion of intestinal contents in excluded ileum. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(02):262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70476-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angerson W J, Allison M C, Baxter J N, Russell R I. Neoterminal ileal blood flow after ileocolonic resection for Crohn's disease. Gut. 1993;34(11):1531–1534. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.11.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coffey C J, Kiernan M G, Sahebally S M. Inclusion of the mesentery in ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease is associated with reduced surgical recurrence. J Crohn's Colitis. 2018;12(10):1139–1150. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]