Abstract

Following V. Frankl’s (in the 1950s) and J. Frank’s (in the 1970s) historical definitions of the constructs Meaning in Life (MiL) and demoralization, there have been a multitude of studies which have described them from different theoretical perspectives. These constructs are closely linked, with the lack of MiL as one of the subconstructs underlying the definition of demoralization. Numerous studies have shown that MiL and demoralization affect suicidality, as protective and risk factors, respectively. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS) is a more recent framework conceptualized by T. Joiner (in the 2000s) to provide an additional possible reading key in the effort to better understand suicidality. By analogy to a previous study by E. Kleiman & J. Beaver (2013), examining MiL and demoralization in suicidality through a perspective of the IPTS framework can be of considerable interest. This study showed, in a cohort of undergraduate students, that MiL mediated the relationship between two variables associated with IPTS (perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness) and suicidal ideation (SI). Taking into consideration future studies that these latter authors advocated, our aim is to verify this finding using a cross-sectional study. Differences in our approach would include a) studying a clinical population (suicidal patients attending an emergency department), b) analyzing relationships not only with SI but also with suicidal attempts (SA), and c) in consideration of the interconnection between MiL and demoralization, exploring also the possible role of demoralization as a mediator. The clinical implication lies in identifying multi-faceted targets that may be useful to mitigate suicidality risk in individuals, both in prevention and therapy intervention.

Keywords: suicide, suicidal behavior, suicidal ideation, meaning in life, demoralization, interpersonal theory of suicide

In recognition of the importance of meaning to the well-being of humans, V. Frankl provided a historical definition of the construct Meaning in Life (MiL), which arose from three inherent assumptions: a) perception and the search for beauty, b), creativity, and c) the effort to choose one’s attitude, also under despondent circumstances.1 The past 20 years have seen a surge in defining MiL from different theoretical perspectives.2–6 Among them, C. Park proposed an integrated model of meaning-making in the context of a particular environmental encounter.2 This author not only distinguished between global and situational meaning but also suggested that meaning and meaning-making efforts should be considered in the evaluation of the process aimed at adjusting one’s experiences of events that are discrepant with one’s larger beliefs, plans, and desires.2 M. Steger proposed a model of MiL in which two sub-constructs are distinguished: the presence of MiL and the search for MiL, each having different clinical implications.3 He also proposed that a consensus in various MiL’s conceptualizations could be reached on three dimensions, respectively the cognitive, motivational, and evaluative: a) coherence, or a sense of comprehensibility and self-concordant ability of making sense centered on the perception that stimuli are predictable and conform to recognizable personal patterns. It is especially activated in situations where meaning is disrupted and the individual experiences distress and the related necessity to construct or reconstruct a framework to understand and transcend chaos; b) purpose, or a feeling of core goals, aims, and direction in life; and 3) significance, or a focus on how important and inherently valuable one’s life as a whole feels beyond trivial or momentary elements.4 When all three components are taken together, a definition for MiL emerges from “the web of connections, interpretations, aspirations, and evaluations” that “1) make our experiences comprehensible, 2) direct our efforts toward a desired future, and 3) provide a sense that our lives matter and are worthwhile”.3,4,6

First introduced in the psychiatric literature by J. Frank, demoralization was defined as a specific cluster of symptoms arising from a

persistent failure to cope with internally or externally induced stresses that the person and those close to him expect him to handle. Its characteristic features, not all of which need to be present in any one person, are feelings of impotence, isolation, and despair.7

Similar to MiL, multiple refinements of this initial definition and supplementary theoretical contributions have followed over time.8–10 A widely used model of demoralization is the one proposed by D. Kissane D. and D. Clarke, in which the construct of demoralization is supported by the presence of five sub-constructs: 1) loss of meaning, 2) hopelessness, 3) helplessness, 4) sense of failure, and 5) dysphoria.11,12 The two concepts of MiL and demoralization are closely linked, with the lack of MiL as one of the sub-constructs underlying the construct of demoralization.11,12

Both MiL and demoralization play a role in affecting suicidality, respectively as protective and risk factors. This concept has recently been summarized in a systematic review13 and supported by some previous analyses by our group in a cohort of patients attending an emergency department for suicidal ideation (SI) and suicidal attempt (SA)14–16

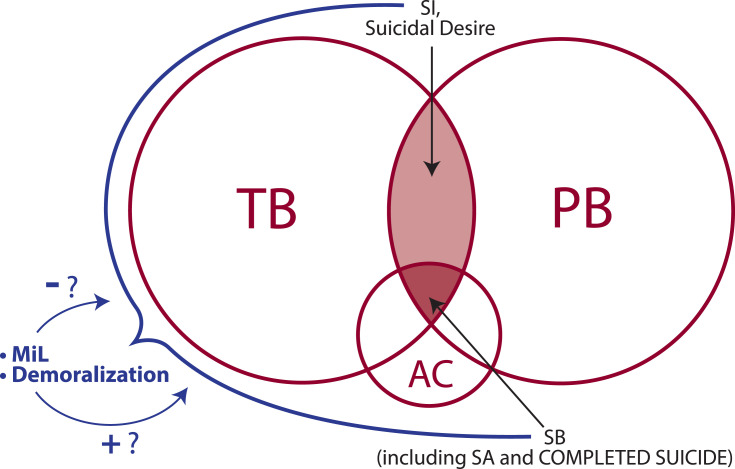

The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS), conceptualized by T. Joiner, posits that the desire to die by suicide is fostered by the amalgamation of two constructs, the perceived burdensomeness (PB), ie, the belief that one is a burden to others, and the thwarted belongingness (TB), ie, the belief that one does not belong to a group. The third construct, the acquired capability for suicide (AC), is conceived as an essential prerequisite for executing the desire to die and moving on to the suicidal behavior (SB), including SA and completed suicides.17,18 Also this theory, similarly to a multitude of previous studies, was confirmed by some of our above-mentioned analyses.19–23

The role of MiL in the framework of IPTS was examined for the first time in an elegant work by E. Kleiman & J. Beaver.24 Given that both PB25,26 and social exclusion (which can be related to TB)27 can predict decreased MiL, and since PB and TB can predict SI,17,18 the authors hypothesized that MiL can mediate the relationship between SI and these IPTS constructs. This was demonstrated in non-clinical population (a cohort of undergraduate students).24

Taking into consideration the perspectives for future studies that E. Kleiman & J. Beaver advocated,24 we aim to verify their hypothesis of MiL as a mediator in the relationship between PB/TB of IPTS and SI by a cross-sectional study. Differences in our approach would include: a) using a clinical population (a well-characterized population of suicidal patients attending an emergency department that was investigated in our previous studies14–16,19–23), b) analyzing the relationship not only with SI but also with SA, and c) extending the exploration to a possible mediator role also for demoralization, considering the interconnectedness between MiL and demoralization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study hypothesis scheme.

Abbreviations: AC, acquired capability for suicide; MiL, Meaning in Life; PB, perceived burdensomeness; SA, suicide attempt; SB, suicidal behavior; SI, suicidal ideation; TB, thwarted belongingness.

Exploration of the etiopathogenetic role in suicidality of these non-neurobiological factors is intended to be only complementary to recognized neurobiological factors, which span and intersect on multiple levels, including genetic, epigenetic, biochemical, neurotransmettitorial, hormonal, anatomic, and neuro-(conventional or functional) radiological.27–30 Finally, the clinical purpose of creating and verifying hypotheses related to the etiopathogenesis of suicidality lies in identifying multi-faceted targets that may be useful to mitigate suicidality risk in individuals, both in prevention and in therapeutic interventions.31–35

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to Dr. Sara De Vita for her precious graphical contribution. Editorial assistance, in the form of language correction, was provided by professional native speakers of XpertScientific Editing Services, whom we thank.

Funding Statement

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Frankl VE. Man’s Search for Meaning. From Death Camp to Existentialism. 1st ed. New York: Beacon Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(2):257–301. doi: 10.1037/a0018301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steger M. Meaning in life In: Lopez S, Snyder C, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009:679–688. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martela F, Steger MF. The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J Posit Psychol. 2016;11(5):531–545. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reker GT. Theoretical perspective, dimensions, and measurement of existential meaning In: Recker GT, Chamberlain K, editors. Exploring Existential Meaning: Optimizing Human Development Across the Life Span. New York: SAGE Publications Inc; 2000:39–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong PTP. The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications. Wong P, editor. New York: Routledge; 2012:xxvii–xliv. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank JD. Psychotherapy: the restoration of morale. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(3):271–274. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.3.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Figueiredo JM, Frank JD. Subjective incompetence, the clinical hallmark of demoralization. Compr Psychiatry. 1982;23(4):353–363. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(82)90085-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fava G, Fabbri S, Sirri L, Wise T. Psychological factors affecting medical condition: a new proposal for DSM-V. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):103–111. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.2.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tecuta L, Tomba E, Grandi S, Fava GA. Demoralization: a systematic review on its clinical characterization. Psychol Med. 2015;45(4):673–691. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kissane DW, Clarke DM, Street AF. Demoralization syndrome — a relevant psychiatric diagnosis for palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2001;17(1):12–21. doi: 10.1177/082585970101700103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke DM, Kissane DW. Demoralization: its phenomenology and importance. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(6):733–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costanza A, Prelati M, Pompili M. The meaning in life in suicidal patients: the presence and the search for constructs. a systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(8):465. doi: 10.3390/medicina55080465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costanza A, Baertschi M, Richard-Lepouriel H, et al. The presence and the search constructs of meaning in life in suicidal patients attending a psychiatric emergency department. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:327. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costanza A, Amerio A, Odone A, et al. Suicide prevention from a public health perspective. What makes life meaningful? The opinion of some suicidal patients. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(3–S):128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costanza A, Baertschi M, Richard-Lepouriel H, et al. Demoralization and its relationship with depression and hopelessness in suicidal patients attending an emergency department. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2232. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joiner TE. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baertschi M, Costanza A, Richard-Lepouriel H, et al. The application of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide to a sample of Swiss patients attending a psychiatric emergency department for a non-lethal suicidal event. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baertschi M, Costanza A, Canuto A, Weber K. The function of personality in suicidal ideation from the perspective of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4):636. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baertschi M, Costanza A, Canuto A, Weber K. The dimensionality of suicidal ideation and its clinical implications. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28(1):e1755. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costanza A, Ambrosetti J, Wyss K, Bondolfi G, Sarasin F, Khan R. Prévenir le suicide aux urgences: de la « Théorie Interpersonnelle du Suicide » à la connectedness [Prevention of suicide at emergency room: from the « interpersonal theory of suicide » to the connectedness]. Rev Med Suisse. 2018;14(593):335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleiman EM, Beaver JK. A meaningful life is worth living: meaning in life as a suicide resiliency factor. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Orden KA, Bamonti PM, King DA, Duberstein PR. Does perceived burdensomeness erode meaning in life among older adults? Aging Ment Health. 2012a;16(7):855–860. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.657156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TE. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: construct validity and psychometric properties of the interpersonal needs questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2012b;24(1):197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stillman TF, Baumeister RF, Lambert NM, Crescioni AW, Dewall CN, Fincham FD. Alone and without purpose: life loses meaning following social exclusion. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;45(4):686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turecki G, Ernst C, Jollant F, Labonté B, Mechawar N. The neurodevelopmental origins of suicidal behavior. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Heeringen K, Mann JJ. The neurobiology of suicide. Lancet Psychiat. 2014;1(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70220-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costanza A, D’Orta I, Perroud N, et al. Neurobiology of suicide: do biomarkers exist? Int J Legal Med. 2014;128(1):73–82. doi: 10.1007/s00414-013-0835-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costanza A, Rothen S, Achab S, et al. Impulsivity and impulsivity-related endophenotypes in suicidal patients with substance use disorders: an exploratory study. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00259-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chytas V, Costanza A, Piguet V, Cedraschi C, Bondolfi G. Démoralisation et sens dans la vie dans l’idéation suicidaire: un role chez les patients douloureux chroniques? [Demoralization and meaning in life in suicidal ideation: a role for patients suffering from chronic pain?]. Rev Med Suisse. 2019;15(656):1282–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costanza A, Baerstchi M, Weber C, Canuto A. Maladies neurologiques et suicide: de la neurobiologie au manque d’espoir [Neurologic diseases and suicide: from neurobiology to hopelessness]. Rev Med Suisse. 2015;11:402–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costanza A, Amerio A, Aguglia A, et al. When sick brain and hopelessness meet: some matters on suicidality in the neurological patient. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2020;19(4):257–263. doi: 10.2174/1871527319666200611130804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costanza A, Amerio A, Radomska M, et al. Suicidality assessment of the elderly with physical illness in the emergency department. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:558974. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.558974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costanza A, Di Marco S, Burroni M, et al. Meaning in life and demoralization: a mental-health reading perspective of suicidality in the time of COVID-19. Acta Biomed. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]