Abstract

Neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) are the mainstay antiviral drugs against influenza infection. In this study, a ligand fishing protocol was developed to screen NAIs using neuraminidase immobilized magnetic beads (NA-MB). After verifying the feasibility of NA-MB with an artificial mixture including NA inhibitors and non-inhibitors, the developed ligand fishing protocol was applied to screen NAIs from the crude extracts of Duchesnea indica Andr. Twenty-four NA binding compounds were identified from the normal butanol (n-BuOH) extract of D. indica as potential NAIs by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC–Q-TOF-MS) assisted with Compound Structure Identification (CSI):FingerID, including 12 ellagitannins, 4 brevifolin derivatives, 3 ellagic acid derivatives, and 4 flavonoids. Among them, 9 compounds were isolated and tested for in vitro NA inhibitory activities against NA from Clostridium perfringens, and from oseltamivir sensitive and resistant influenza A virus strains. The results indicate that compound B23 has the NA inhibitory activities in both the oseltamivir sensitive and resistant viral NA, with half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 197.9 and 125.4 μmol/L, respectively. Moreover, B23 can obviously reduce the replication of oseltamivir sensitive and resistant viruses in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells at the concentrations of 40 and 200 μmol/L.

KEY WORDS: Neuraminidase inhibitors, Duchesnea indica Andr., Ligand fishing, Magnetic beads, HPLC–Q-TOF-MS, Influenza A, Virus

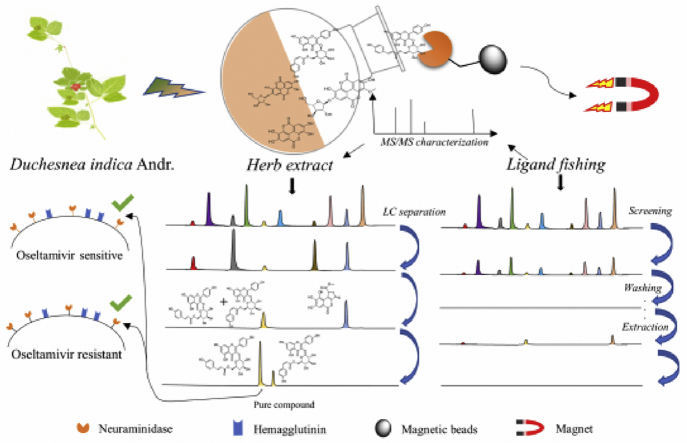

Graphical abstract

An efficient neuraminidase ligand fishing protocol was developed and verified to rapidly screen the neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) from natural sources. Twenty-four potential neuraminidase inhibitors were identified from Duchesnea indica as potential NAIs by HPLC–Q-TOF-MS. One compound can inhibit neuraminidase activities in both the oseltamivir sensitive and resistant virus strains.

Highlights

-

•

An efficient ligand fishing protocol was developed to rapidly screen the neuraminidase inhibitors from natural sources.

-

•

24 potential neuraminidase inhibitors were identified from Duchesnea indica as potential NAIs by HPLC-Q-TOF-MS.

-

•

One compound can inhibit neuraminidase activities in both the oseltamivir sensitive and resistant virus strains.

1. Introduction

Influenza is an acute respiratory disease, causing by influenza A, B and C viruses. Among these, types A and B influenza viruses can lead to seasonal epidemics or even worldwide pandemic. Influenza infection is still an imminent threat to public health especially when affecting elders, children as well as people with chronic diseases1,2. Influenza virus neuraminidase (NA) is a key enzyme in viral replication, transmission, and pathogenesis, which is highly conserved for both influenza A and B viruses3. Therefore, NA has been proved as one of the most promising targets for combating against influenza. Presently, four drugs targeting NA, namely zanamivir, oseltamivir, paramivir and lanimivir4, are on the market. However, the appearance of drug-resistant strains and drug toxicity revealed urgent need to discover new alternative drug leads targeting NA5.

Natural products are a rich source of active compounds for this highly infectious pathogen2. Many traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) for clearing heat and detoxicating are used singly or as a component of TCM formulas to cure influenza infection in China6, 7, 8. Among these, Duchesnea indica Andr., locally called mockstrawberry, has been used for thousands of years in treatment of fever, inflammation, cancer, etc.9. In one study, D. indica has been screened out to be one of five potent anti-influenza plants from 439 TCMs using NA inhibitory and anti-influenza assay; however, the active components in it are still unclear10. The methods for isolating NA inhibitors from natural products include traditional separation and bioassay-guided fractionation, but both are time consuming and labor-intensive for screening active compounds11. The binding ability of a natural compound to a drug target protein is crucial for assessing the biological activities of the natural product12. Thus, a targeted protein oriented ligand fishing method would be an efficient strategy for identifying active compounds from complex systems like natural product extracts or microbes13. Herein, we developed an immobilized NA microreactor to screen neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) from the plant extract of D. indica (Fig. 1). At first, we used an artificial mixture including NA inhibitors and non-inhibitors to verify the feasibility of NA microreactor in complex systems. Next, a screening of NAIs from the crude extract of D. indica was carried out. 24 NA binding compounds were fished out and identified using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC–Q-TOF-MS) assisted with Compound Structure Identification (CSI):FingerID from the normal butanol (n-BuOH) extract of D. indica. Furthermore, nine compounds were isolated. An in vitro NA inhibitory assay indicated that these compounds showed obvious NA inhibitory activities on NA from Clostridium perfringens, and oseltamivir sensitive and resistant influenza A virus strains. Among these, compound B23 showed an equal NA inhibitory activity in both the oseltamivir sensitive and resistant virus strains, and can greatly reduce the replication of oseltamivir sensitive and resistant viruses in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells at the concentrations of 40 and 200 μmol/L.

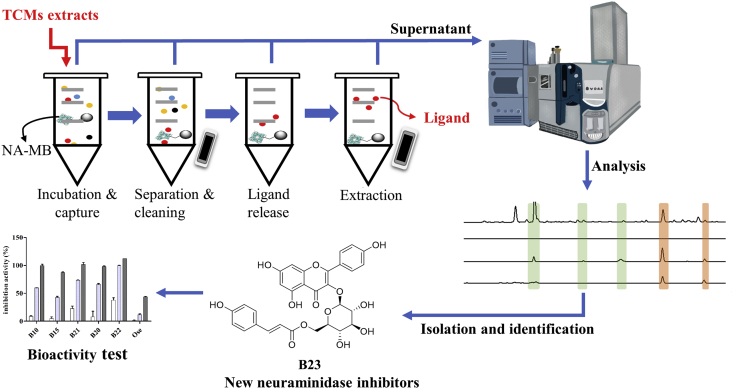

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of NAIs screening using NA immobilized magnetic beads combined with HPLC–ESI-Q-TOF-MS.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Materials and reagents

NA from C. perfringens (Type V, 6 UN, lyophilized powder) and 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid sodium salt hydrate (MUNANA) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The BeaverBeads™ Mag NH2 amine-terminated magnetic beads (2 μm, 10 mg/mL) were the products of Beaverbio Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). Pyridine, Tris(hydroxymethyl) methyl aminomethane (Tris), 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES), 50% glutaraldehyde, ammonium acetate, and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) were all obtained from Aladdin Chemistry (Shanghai, China). Standard compounds, including galantamine, jatrorrhizine, galuteolin, quercetin, luteolin, and isorhamnetin were obtained from Shanghai Yuanye biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Acetonitrile and methanol (HPLC grade) were purchased from Merck (Germany). Deionized water purified by a Milli-Q water-purification system from Millipore (Bedford, MA, USA) was used for reagent and sample preparation and dilution. All buffer mentioned in this article were freshly prepared before experiments.

2.2. Instrumentation

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on an Agilent 1100 HPLC system equipped with a diode array detector (Agilent Technologies, Ltd., Santa Clara, CA, USA), using a Waters Symmetry C18 column (5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). HPLC–Q-TOF-MS analysis was accomplished on a Shimadzu Nexera Prominence Liquid Chromatography system coupled to AB SCIEX X500R Quadrupole time of flight tandem mass spectrometry (AB SCIEX Co., Redwood City, CA, USA), which was equipped with an Electrospray Ionisation (ESI) source, using a Waters Symmetry C18 column (5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, Waters Corporation). Data acquisition and analysis were controlled by SCIEX OS software (Ver. 1.3.1, AB SCIEX Co.). Column chromatography was performed on YMC-Pack Phenyl (YMC Co., Ltd., Kyoko, Japan). Preparative HPLC was performed on a QBH-LC2000 system (Beijing QingBoHua Technologies Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) which was equipped with binary-channel ultraviolet (UV) detector, using a Phenomenex Kinetex C8 preparative column (250 mm × 21.2 mm, 10 μm) and Phenomenex Luna C18(2) column (5 μm, 250 mm × 10.0 mm) (Phenomenex Inc., USA) for preparative purification. The flow rate of preparation was 15 mL/min and of the semi-preparation was 5 mL/min. The Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR, 500 MHz) and Carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (13C NMR, 125 MHz) spectra were measured on Bruker AV-500 M spectrometer (Bruker Instrument, Inc., Zurich, Switzerland) while using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard.

2.3. Preparation and validation of NA immobilized magnetic beads

NA immobilized magnetic beads (NA-MB) were synthesized following the previously published method with slight modifications14. Briefly, a suspension of 0.8 mL of BeaverBeads™ Mag NH2 amine-terminated magnetic beads (Beaverbio Co., Ltd.) was magnetically separated from the supernatant using a magnetic separator and washed 3 times with 1 mL of coupling buffer (10 mmol/L aqueous pyridine, pH 6.0). The beads were then re-suspended in 1 mL of 5% glutaraldehyde solution in coupling buffer and rotated in the orbital rotator at 4 °C for 3 h in the dark. After the beads were washed with 1 mL of coupling buffer for 3 times, 0.18 mg NA lyophilized powder (15.3 units/mg) was reacted with the activated beads in coupling buffer. The mixture was rotated at 4 °C for 16 h. After magnetic separation, the magnetic beads were washed 3 times with 1 mL of an end-capping solution (100 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.0). Finally, the supernatant was removed and amine-terminated-coupled NA-MB (2.754 units NA/mg magnetic beads) were washed with 1 mL storage buffer (15 mmol/L ammonium acetate, pH 5.5) and stored in 1 mL at 4 °C. The control group (denatured NA-MB) was denatured at 80 °C for 1 h after synthesized in the same way.

The HPLC conditions of NA-MB activity verification including detection wavelength and the elution gradient were optimized. Acidified water (0.1% formic acid water solution, A) and methanol (B) were used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The solvent gradient was as follows: 30%–70% B at 0–10 min. HPLC separations was performed on a Phenomenex Gemini C18 column (3 μm, 100 mm × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex Inc.) and UV detector was set at 310 nm.

2.4. In vitro NA inhibition assay

2.4.1. Virus source

Oseltamivir sensitive NA from A/Puerto Rico/8/34 virus source: A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) (PR8) virus is preserved in the laboratory. Oseltamivir resistant neuraminidase from recombinant virus source: the H274Y mutant is obtained by H274Y mutation of NA gene and saved through reverse genetic manipulation based on the PR8 virus in our laboratory. The two viruses are purified by the chicken embryo amplification. NA enzyme solution is prepared by lysis of purified virus with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% Triton. The viral protein concentration is 1 mg/mL.

2.4.2. NA inhibitory assay

The NA activity was measured basing on MUNANA as the substrate15,16. A NA inhibitory assay was carried out in 96-well plates containing 25 μL of NA solution (final concentration: 0.021 U/mL) and 25 μL of a sample. All samples were dissolved in DMSO (Aladdin Chemistry) and diluted to the corresponding concentrations using substrate buffer [in MES buffer (32.5 mmol/L MES, 4 mmol/L CaCl2, pH 6.5)] and the final substrate concentration was 0.05 mmol/L. The enzymatic reactions lasted for 30 min at 37 °C. The intensity of the fluorescence product 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) was measured using a Synergy™ HTX Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, Doraville, GA, USA) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 and 460 nm, respectively. Each assay was performed in no less than 3 times. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for reducing the NA activity was then determined. The data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The inhibition ratio was calculated using the Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where I, Ib and I0 are the fluorescence of the tested samples (enzyme, buffer, sample solution, and substrate), the blank control (buffer and substrate) and the negative control (enzyme, buffer, and substrate) after 15 min of incubation, respectively.

2.5. Plant extraction and sample preparation

D. indica were collected from Anhui Province, China in September 2016 and identified by Professor Guangxiong Zhou (Jinan University, Guangzhou, China). Dried D. indica (1000.0 g) was extracted with 75% ethanol three times, each time for one hour to give 126.0 g crude extract, which was suspended in deionized water and was subsequently partitioned by petroleum ether (PE) and normal butanol (n-BuOH).

2.6. Ligand fishing analysis of a mixture of natural products

A mixture of natural products [0.01 mg galantamine, 0.01 mg jatrorrhizine, 0.03 mg galuteolin, 0.02 mg quercetin, 0.06 mg luteolin, and 0.03 mg isorhamnetin (Shanghai Yuanye biotechnology co.) in 1 mL storage buffer which contains 5% DMSO (Aladdin Chemistry), M-S0] was added to the above freshly prepared NA-MB, and the mixture was gently mixed for 3 h at room temperature by a rotating mixer. The supernatant (M-S1) was separated by magnetic separator. The beads were washed 4 times with storage buffer (1 mL), and each time mixed at room temperature for 8 min on a rotary mixer, the supernatant of each wash was M-S2–M-S5. In the extraction step, 50% methanol (MeOH) was first added to the beads, followed by extraction with methanol to obtain supernatants M-S6–M-S9. 500 μL of M-S0–M-S9 were filtered and analyzed by HPLC. HPLC separations were carried out using a Waters Symmetry C18 column (5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, Waters Corporation) with a 45 min linear gradient from 10% to 100% methanol containing 0.1% formic acid. UV detector was set at 280 nm.

2.7. Application of ligand fishing in D. indica extracts

Weigh 1.0 mg n-BuOH part of D. indica exactly, and dissolved in 1 mL storage buffer which contain 5% DMSO (SM-S0). The mixed solution (1 mL, SM-S0) was added to 8 mg of the NA-MB. The incubation time was optimized to be 12 h at room temperature, and the supernatant (SM-S1) was collected. The beads were washed with 8 × 1 mL of storage buffer (SM-S2–SM-S9) and followed extract with 50% MeOH and 3 × 1 mL of MeOH to yield SM-S10–SM-S13.

These samples (SM-S0–SM-S13) were separated in the following gradient program, analyzed by HPLC–Q-TOF-MS, using a Waters Symmetry C18 column (5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, Waters Corporation) with the mobile phase containing acidified water (0.1% formic acid) (A) and methanol (B): 5%–10% B at 0–10 min, 10%–32% B at 10–40 min, 32%–38% B at 40–45 min, 38%–50% B at 45–60 min, 50% B at 60–65 min, 50%–65% B at 65–70 min. Q-TOF-MS/MS analysis was performed in negative ion mode with a mass range of 50–1500 Da for TOF-MS scan and 50–1500 Da for TOF-MS/MS scan. The following optimized operating parameters were used: source voltage, −4500 V; source temperature, 550 °C; the pressure of Gas 1 (Air) and Gas 2 (Air), 55 psi; the pressure of Curtain Gas [nitrogen (N2)], 35 psi; collision energy, 35 eV; Mass tolerance, ±50 mDa. The experiments were run with 0.15 s accumulation time for TOF-MS and 0.04 s accumulation time for TOF-MS/MS.

The control NA-MB was also prepared in the same procedure as the NA-MB. By comparing the chromatograms of the experimental and control samples, “hit” compounds in the natural product extract can be screened as potential NA ligands.

2.8. Isolation of the target ligands by preparative HPLC

The air-dried and powdered D. indica (1000.0 g) were ultrasonic extracted with 75% ethanol. After filtered and removal of the solvent, the ethanol extract (126.0 g) was suspended in water (H2O) and was subsequently partitioned by PE and n-BuOH. Then the n-BuOH layer (18.1 g) was subjected to column chromatography (YMC-Pack phenyl:MeOH/H2O, 10:90 to 100:0, in gradient) to give nineteen fractions (Frs. 1–19). The HPLC–MS guided fractionation was carried out as follows to obtain the individual compounds. Fr. 4 (450.2 mg) was subjected to semi-preparative HPLC (MeOH/H2O, 15:85) to yield compound B3 [4.6 mg, retention time (tR) = 22.2 min] and compound B4 (6.2 mg, tR = 24.5 min). Fr. 5 (302.7 mg) were subjected to preparative HPLC (MeOH/H2O, 15:85) to yield compound B10 (2.0 mg, tR = 15.4 min) and compound B15 (3.6 mg, tR = 22.5 min). Fr. 9 (1502.2 mg) were subjected to reversed phase C18 silica gel (MeOH/H2O, 10:90 to 100:0, in gradient) to give fourteen sub-fractions that were further purified by semi-preparative HPLC to yield B20 (3.9 mg, tR = 20.5 min), B21 (4.1 mg, tR = 25.7 min), B22 (5.0 mg, tR = 30.5 min). Fr. 11 (280.5 mg) was subjected to semi-preparative HPLC (MeOH/H2O, 50:50) to yield compound B23 (10.6 mg, tR = 18.4 min) and compound B24 (4.2 mg, tR = 19.1 min).

2.9. Inhibition of influenza virus growth in MDCK cells

MDCK cells grew in 96-well plates confluent and were infected with PR8 virus (oseltamivir sensitive strains or resistant recombinant virus with H274Y mutation) at 0.01 multiplicity of infection (MOI). The infection medium [0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma–Aldrich) and 1 μg/mL tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK, Sigma–Aldrich) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Sigma–Aldrich)] with virus was removed 2 h post infection, and then the infection medium with compounds at indicated dilution were added in 96-well plate. The virus infected cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 24 h post infection. The viral protein expression in the cells was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with anti-PR8 mouse serum. The inhibitory activity was showed as relative value of the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) of experimental wells normalized to average OD450 of viral control wells. Results were representative of three independent experiments and analyzed with Graphpad prism (GraphPad Software Inc.).

3. Results

3.1. Immobilized NA activity study

Prior to the application of NA-MB to screen NAIs, the final immobilized enzymes required to retain NA activity for further ligand capture. A simple activity evaluation of each NA-MB was performed using the NA specific substrate (MUNANA). The following four groups of parallel assays were performed to determine the activity of the immobilized NA: (1) NA immobilized magnetic beads (group 1); (2) NA immobilized magnetic beads (denatured, group 2); (3) magnetic beads (group 3); (4) MUNANA. If the peak of the hydrolyzed product (4-MU) of MUNANA appears after incubation, it proves that the substrate has been completely hydrolyzed and that group was enzymatically active. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S1, only the NA immobilized magnetic beads can hydrolyze MUNANA, which proved that the hydrolysis activity of NA was retained after the immobilization.

3.2. Ligand fishing and high performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC–DAD) analysis of an artificial mixture

With the NA-MB in hand, the ligand fishing protocol was first verified and optimized using an artificial mixture of five known NA inhibitors (jatrorrhizine, galuteolin, quercetin, luteolin and isorhamnetin) and one NA non-inhibitor (galantamine). The method includes three steps: loading, washing and extraction. Firstly, the NA-MB was incubated with the loading solution (M-S0) at 37 °C for 3 h. Then the supernatant (M-S1) was removal after magnetic separation of the beads. The NA-MB residue was further washed four times by a washing buffer (M-S2–M-S5) to ensure the removal of compounds with low or no affinity to NA. In the extraction step, we used 50% (M-S6) and 100% (M-S7–M-S9) organic solvent to release binding ligands with different affinities. As shown in Fig. 2, galantamine was identified to be in M-S1, which supported it is a non-inhibitor of NA, while jatrorrhizine was gradually washed out from M-S2 to M-S6, indicating that it might bind to both the inactive site and active pocket of the enzyme. Galuteolin and isorhamnetin started to release from the enzyme when NA-MB was extracted using 50% organic solvent, while quercetin and luteolin were fished out with the highest amount using 100% organic solvent in M-S7, confirming that they are specific inhibitors of NA. In order to exclude the non-specific absorption of NA, NA-MB was denatured by heating at 80 °C for 1 h in the control group which followed by a parallel experiment as the experimental group. The results (Supporting Information Fig. S2) show that all compounds except jatrorrhizine were washed out at the initial wash step (M-C-S1), which confirmed the affinity of all selected inhibitors to NA is specific. It's not surprising that jatrorrhizine was gradually washed out in the washing step, as it was supposed to bind to inactive site of NA observed in previous experiment. The above results demonstrate that the NA-MB has a forceful screening potential for specific ligands of NA from complex systems.

Figure 2.

HPLC profile obtained from different extraction (M-S0 to M-S9) of model mixture containing of galantamine (I), jatrorrhizine (II), galuteolin (III), quercetin (IV), luteolin (V), and Isorhamnetin (VI).

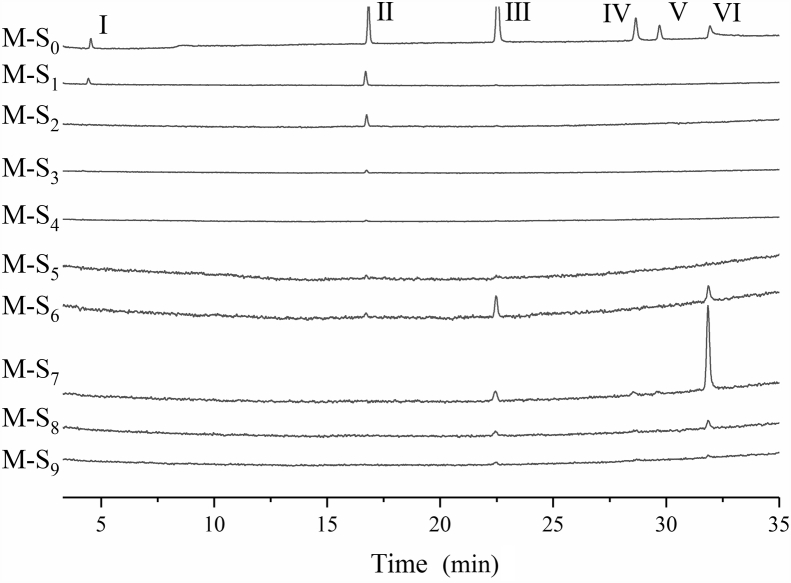

3.3. Application of ligand fishing in D. indica extracts

The 95% ethanol extract of D. indica was subsequently partitioned between different organic solvents and water to yield three fractions (aqueous, PE and n-BuOH parts). A following in vitro NA inhibition assay revealed that the n-BuOH part has significant NA inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 8.24 ± 0.16 μg/mL (Supporting Information Fig. S3), and therefore it was selected as the target sample for ligand fishing.

The n-BuOH layer of D. indica was screened using the optimized ligand fishing procedure outlined in Section 3.2. In order to exclude the non-specific binding to NA, the magnetic beads with denatured NA were used as the control group. Repeated washing steps (SM-S2–SM-S9) ensured removal of no or low affinity ligands. As shown in Fig. 3, comparison of the high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with high resolution mass spectrometry (HPLC–HRMS) extraction ion chromatography (EIC) peaks of the loading solution (SM-S0) with the first extraction fraction (SM-S10), we can find 24 potential peaks (B1 to B24) in the n-BuOH layer of D. indica. All of these peaks did not exist in the extraction fraction (SM-C-S10) of the control group, indicating they could be potential specific NA ligands (Fig. 3 and Supporting Information Fig. S5).

Figure 3.

Overlaid extraction ion chromatograms (EICs) acquired of different solutions obtained from NA-MB-based ligand fishing from n-butanol extract of D. indica.

3.4. Identification of target ligands using HPLC–Q-TOF-MS/MS assisted with CSI:FingerID

In order to identify all “fish out” peaks, the possible ligands were analyzed with HPLC–Q-TOF-MS/MS. The captured peaks have higher intensities in negative ion mode than in positive ion mode. Then CSI:FingerID was applied to interpret the MS and MS2 spectra of each potential peak and predicted matched structures from Pubchem library using the software SURIUS 4.0.117,18. The molecular structure searching results gave us a fast annotation of 24 “fished out” ligands (B1–B24), ascribed to ellagitannins, ellagic acid derivatives, flavonoids and other phenolic compounds. The ultimate structures of B1–B12 and B14–B24 were confirmed by analyzing their tR, fragmentation behaviors and proposed fragmentation pattern referred to literatures. LC–MS information for all marked potential NA ligands, including tR, m/z value, formula, MS/MS data and the proposed structures are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

MS/MS data and identification of 24 active peaks of n-butanol extract of D. indica obtained by ligand fishing (SM-S10).

| Peak | tR (min) | Measured m/z ([M–H]–) | Δ(ppm) | Formula | MS/MS spectra | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ellagitannins | ||||||

| B1 | 24.29 | 783.0679 | −0.2 | C34H24O22 | 275.0191 (92) 300.9988 (227) 481.0620 (35) |

Bis-HHDP-glucoseb |

| B2 | 26.27 | 633.0733 | 0.1 | C27H22O18 | 300.9988 (2746) 275.0191 (462) 463.0498 (253) 169.0135 (225) 481.0620 (230) |

Galloyl-HHDP- glucoseb |

| B3 | 27.55 | 633.0733 | −0.2 | C27H22O18 | 300.9990 (3568) 275.0200 (664) |

Sanguiin H-4 |

| B4 | 33.66 | 633.0733 | 0.6 | C27H22O18 | 300.9996 (3006) 275.0207 (277) 463.0533 (175) |

Strictinina |

| B5 | 34.78 | 635.0890 | 0.3 | C27H24O18 | 465.0668 (1753) 169.0140 (1570) 313.0564 (1248) 421.0774 (192) 295.0455 (175) 483.0784 (150) |

Trigalloyl-glucose isomer 1b |

| B6 | 36.64 | 785.0836 | 0.6 | C34H26O22 | 300.9988 (409) 275.0197 (112) 249.0402 (82) 483.0767 (57) |

Bis-galloyl-HHDP-glucoseb |

| B7 | 38.03 | 483.0772 | −0.7 | C20H20O14 | 271.0453 (337) 169.0139 (272) 211.0250 (115) 313.0565 (112) 331.0671 (65) 125.0242 (45) |

Bis-galloyl-glucoseb |

| B8 | 41.38 | 935.0800 | 0.4 | C41H28O26 | 300.9991 (175) 633.0733 (169) |

Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucoseb |

| B9 | 44.15 | 635.0887 | −0.5 | C27H24O18 | 465.0670 (1792) 169.0138 (150) 313.0559 (137) |

Trigalloyl-glucose isomer 2b |

| B11 | 48.99 | 635.0887 | −0.6 | C27H24O18 | 169.0140 (425) 465.0676 (374) 313.0564 (240) 483.0770 (135) 423.0556 (75) 211.0244 (65) |

Trigalloyl-glucose isomer 3b |

| B12 | 49.38 | 787.0998 | −0.8 | C34H28O22 | 617.0782 (903) 465.0667 (551) 169.0143 (281) 635.0880 (162) 447.0569 (131) 573.0864 (106) |

Tetragalloyl-glucose isomer 1b |

| B14 | 51.68 | 787.0998 | −0.4 | C34H28O22 | 617.0776 (986) 169.0133 (83) 449.0732 (83) 465.0671 (75) |

Tetragalloyl-glucose isomer 2b |

| Brevifolin and its derivatives | ||||||

| B10 | 48.51 | 291.0146 | −1.5 | C13H8O8 | 191.0348 (2025) 145.0299 (966) 219.0301(915) |

Brevifolin carboxylic acida |

| B15 | 52.68 | 305.0303 | −1.3 | C14H10O8 | 217.0143 (5447) 273.0040 (5118) 245.0091 (4686) |

Methyl brevifolin carboxylatea |

| B16 | 53.92 | 247.0249 | −0.9 | C12H8O6 | 191.0352 (2683) 145.0295 (1974) 219.0304(1016) |

Brevifolinb |

| B17 | 58.98 | 319.0454 | −0.4 | C15H12O8 | 273.0040 (4946) 217.0141 (3974) 245.0091 (3453) |

Ethyl brevifolin carboxylateb |

| Unknown | ||||||

| B13 | 50.52 | 444.0575 | ND | ND | 299.0078(453) 309.9986(448) 354.0256(1076) |

ND |

| Flavonoids | ||||||

| B18 | 60.28 | 431.0981 | −1.3 | C21H20O10 | 311.0557 (3326) 283.0610 (1425) 341.0664 (1304) |

Isovitexinc |

| B19 | 60.99 | 447.0926 | −0.6 | C21H20O11 | 285.0403(1888) 284.0323(806) 174.9560(237) |

Luteolin-7-O-galactosideb |

| B23 | 70.83 | 593.1301 | 0.2 | C30H26O13 | 147.0441 (3005) 287.0550 (705) 309.0983 (162) |

Tilirosidea |

| B24 | 71.33 | 593.1301 | −1.0 | C30H26O13 | 147.0441 (2929) 287.0550 (1726) 309.0983 (205) |

cis-Tilirosidea |

| Ellagic acid derivatives | ||||||

| B20 | 62.32 | 433.0412 | −0.3 | C19H14O12 | 299.9915 (12324) 300.9989 (7285) |

4-O-α-l-Arabinofuranoside Ellagic acida |

| B21 | 65.66 | 300.9990 | −0.6 | C14H6O8 | – | Ellagic acida |

| B22 | 68.52 | 447.0569 | −0.2 | C20H16O12 | 315.0143 (670) 284.0320 (538) 299.9911 (463) |

Ducheside Ba |

ND, can't be determined based on current MS data.

–, no fragments detected.

The structure was identified by NMR.

Identified based on the published literature.

Verified by reference standards.

3.4.1. Ellagitannins

Twelve ellagitannins (B1–B9, B11, B12, and B14) have been fished out from the BuOH part of D. indica. Typical neutral losses of ellagitannins during fragmentation include galloyl (152 Da), galloyl acid (170 Da), galloyl glucose (332 Da), hexahydroxydiphenic acid (HHDP) (302 Da), HHDP-glucose (482 Da) and galloyl-HHDP-glucose (634 Da). Besides, the ellagitannins show a characteristic fragment ion peak at m/z 301 due to a lactonization procedure to produce ellagic acid19. B1 with a pseudo-molecular ion at m/z 783.0679 [M–H]– delivered fragment ions at m/z 301 [ellagic acid–H]– and 481 [M–302–H]– (loss of HHDP), corresponding to a bis-HHDP-glucose fragmentation pattern. B2–B4 are isomers with identical pseudo-molecular ion at m/z 633.0733 [M–H]– with a base peak at m/z 301 [ellagic acid–H]– and a minor fragment peak at m/z 463 [M–170–H]– (loss of galloy acid) in their MS2 spectra, consisting with a galloyl-HHDP-glucose. B5, B9 and B11, possessing a pseudo-molecular peak at m/z 635.0890 [M–H]–, are identified as trigalloyl-glucose isomer on the presence of three main fragment ions at m/z 465 [M–170–H]– (loss of galloy acid), 169 [gallic acid–H]–, and 313 [M–170–152–H]– (loss of galloy and galloyl acid). B6 is tentatively assigned as bis-galloyl-HHDP-glucose based on its quasi-molecular ion peak at m/z 785.0836 [M–H]– and fragmentions at m/z 483 [M–302–H]– (loss of HHDP), 301 [ellagic acid–H]– and 169 [gallic acid–H]–. B7 is designated as bis-galloyl-glucose, which displays a quasi-molecular ion peak at m/z 483.0772 [M–H]–, and fragment ions at 313 [M–170–H]– and 169 [gallic acid–H]–. B8 is identified as galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose with a quasi-molecular ion peak at m/z 935.0800 [M–H]–, and MS/MS fragment at m/z 301 [ellagic acid–H]– and 633 [M–302–H]– (loss of HHDP). B12 and B14 are the isomers of tetra-galloyl-glucose, with a quasi-molecular ion peak at m/z 787.0998 [M–H]–, whose fragmentation pattern consists of ions at m/z 617 [M–170–H]– (loss of galloyl acid), 465 [M–170–152–H]– (loss of galloyl and galloyl acid), and 169 [gallic acid–H]–.

3.4.2. Brevifolin derivative

The molecular weight of B16 is 44 Da less than B10. They show quasi-molecular ion peaks at m/z 247.0249 [M–H]– and m/z 291.0146 [M–H]–, respectively and two identical fragment ions at m/z 191 and 219, which coincide with MS/MS data of brevifolin and brevifolin carboxylic acid9. B15 has an [M–H]– ion at m/z 305.0303 and fragment ions at m/z 273, 245, and 229, suggesting a methyl ester derivative of brevifolin carboxylic acid (B10)9. B17 has an [M–H]– ion at m/z 319.0454, 14 Da higher than that of B15 and identical fragment ions at m/z 273, 245, and 229, indicating it's an ethyl ester of B10. Thus B10 and B15–17 are tentatively identified as brevifolin carboxylic acid, methyl brevifolin carboxylate, brevifolin, and ethyl brevifolin carboxylate. Brevifolin and its analogues have been reported to be present in D. indica20.

3.4.3. Flavonoids

An on-line molecular structure search assisted by CSI:FingerID gave us a well matched result of each flavonoid, i.e., peaks B18, B19, B23 and B24. B18 has an [M–H]– at m/z 431.0975, and characteristic flavonoid-C-glycoside fragment ions at m/z 341 [M–90–H]– and 311 [M–120–H]– thus is identified as isovitexin and confirmed by comparison of the retention time with standard. B19 shows a quasi-molecular ion at m/z 447.0926 and fragment ions at m/z 285 [M–162–H]– (loss of hexose) and 174, which coincides with MS/MS data of cinaroside21. B23 and B24 are isomers with the same quasi-molecular ion at m/z 593.1301 [M–H]– and similar fragment ions at m/z 285, 255 and 145, and are identified to be tiliroside and cis-tiliroside assistant with CSI:FingerID and comparison with lieteratures.

3.4.4. Ellagic acid derivative

B20, B21 and B22 are ellagic acid derivatives based on their MS and MS/MS data. B20 shows a quasi-molecular ion peak at m/z 443.0412 [M–H]– and fragment ions at m/z 301 [M–132–H]–, supporting it's a glycoside of ellagic acid. B22 has an [M–H]– ion at m/z 447.0669, 14 Da higher than that of B20, indicating it's a methylation derivative of B20. B21 has an [M–H]– at m/z 300.9990 and fragment ions at m/z 257, 285 and 229, which is typical fragment ions of ellagic acid.

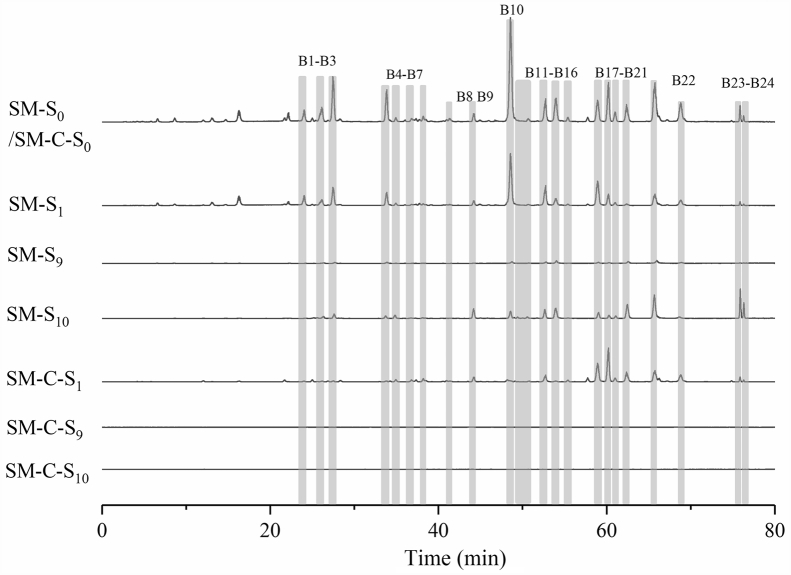

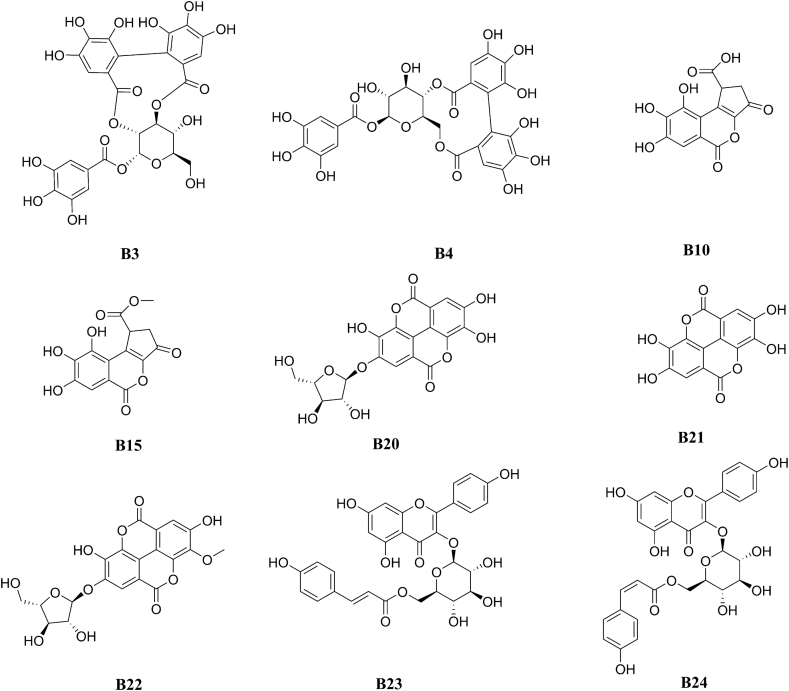

3.5. Isolation of the target ligands by preparative HPLC

Under the guidance of the above results, nine target compounds B3, B4, B10, B15, B20, B21, B22, B23, and B24 were isolated and identified by NMR. Their structures were shown in Fig. 4, including two ellagitannins, two flavonoids, two brevifolin derivatives, and three ellagic acid derivatives. The structural patterns of the isolated NA ligands are the same as those identified by MS/MS data. By comparison of their NMR data with those reported in literatures, the ellagitanins B3 and B4 are determined to be sanguiin H-4 and strictinin22,23, the brevifolin derivatives B10 and B15 are brevifolin carboxylic acid and methyl brevifolin carboxylate24,25, the flavonoids B23 and B24 are tiliroside and cis-tiliroside26, while the ellagic acid derivatives B20, B21 and B22 are 4-O-α-l-arabinofuranoside ellagic acid, ellagic acid and ducheside B25,27.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of isolated compounds.

To the best of our knowledge, all the isolated compounds, except B428 and B2129, are identified as NA ligands for the first time. More importantly, with potential NA inhibitors in hand, we can further verify the in vitro NA inhibitory activities.

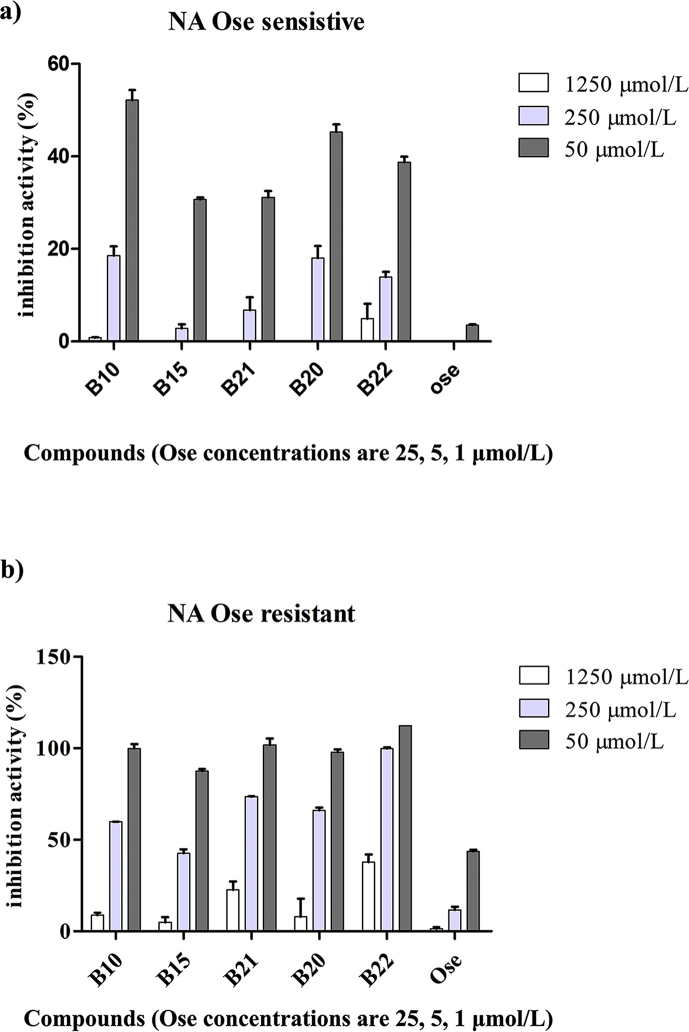

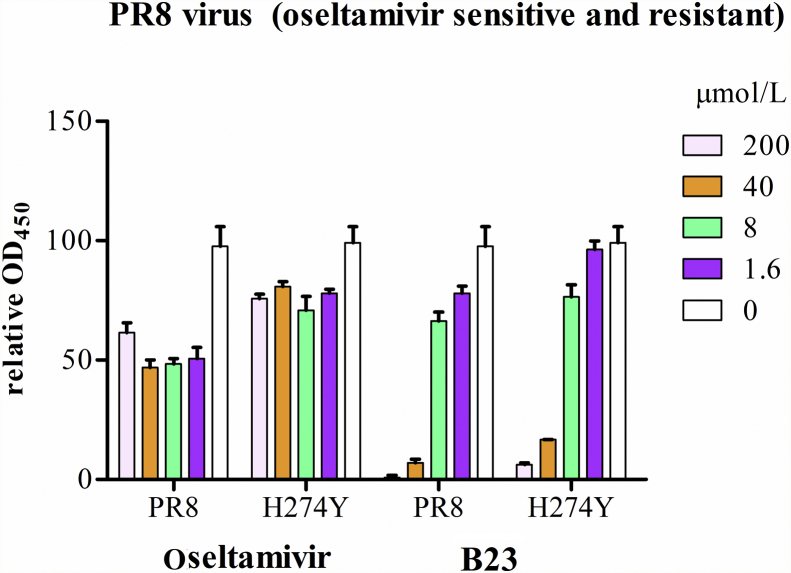

3.6. Inhibitory effect of isolated compound on NA and influenza virus

In order to verify if the isolated NA ligands possess NA inhibitory activities, an activity screening was performed using previous reported methods with a slight modification. As shown in Table 2, all of the tested compounds can inhibit NA from C. perfringens with IC50 values in a range of 10–100 μmol/L. Furthermore, we tested their NA inhibitory activities on oseltamivir sensitive or resistant NA, the results show that compounds B10, B15, B20, and B21 can obviously inhibit NA activities at 250 and 1250 μmol/L (Fig. 5). Notably, compound B23, a coumaroyl flavonoid, showed similar inhibitory activities against the oseltamivir sensitive and resistant viral NA, with IC50 values of 197.9 and 125.4 μmol/L, respectively (Table 3), which encouraged us to test the anti-virus effects of B23 on influenza virus. The results show that B23 can obviously reduce the sensitive and resistant PR8 virus replication in MDCK cells at the concentrations of 40 and 200 μmol/L, respectively (Fig. 6).

Table 2.

Inhibitory activities of NAIs on NA from Clostridium perfringens.

| Compounds | IC50 (μmol/L) |

|---|---|

| B3 | 17.48 ± 2.9 |

| B10 | 98.68 ± 4.7 |

| B15 | 138.26 ± 0.8 |

| B20 | 54.00 ± 3.0 |

| B22 | 90.32 ± 2.6 |

| B23 | 17.83 ± 0.9 |

| B24 | 11.45 ± 1.2 |

| Quercetin | 59.21 ± 1.5 |

Figure 5.

NA inhibitory activities of B10, B15, B21, B20 and B22 on NA from oseltamivir sensitive (a) and resistant virus strain (b).

Table 3.

NA inhibitory activities of B4 and B23 on NA from oseltamivir sensitive and resistant virus strains.

| Compd. | NAC (μmol/L) | NAS (μmol/L) | NAR (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B4 | – | 107.8 | 500.5 |

| B23 | 17.8 | 197.9 | 125.4 |

| Quercetin | 40.4 | – | – |

| Oseltamivir (nmol/L) | – | 1.323 | 527.3 |

NAC: neuraminidase from Clostridium perfringens.

NAS: oseltamivir sensitive neuraminidase.

NAR: oseltamivir resistant (with H274Y mutation) neuraminidase.

–: not test.

Figure 6.

The effects of B23 on virus replication of oseltamivir sensitive and H274Y mutatant PR8 viruses in MDCK cells.

4. Discussion and conclusions

NAIs are the most ideal drugs for anti-influenza virus infection. However, drug resistance may emerge during drug exposure, particularly among young children. For example, influzenza virus H1N1 with H274Y NA mutation can cause drug resistance of oseltamivir, which is the most widely anti-influenza drug, thus might generate a future pandemic influenza strain30. Currently, NA-based drug development aims to find alternative therapy options and search for new NAIs to treat predominant H274 and H274Y mutant strains31. Natural products from traditional medicinal plants can serve as a source of new anti-influenza drug leads and may help in the development of safer and less toxic NA inhibitors against influenza virus31. In this study, we used an efficient “NA ligand fishing” protocol to rapidly screen the NAIs from the plant D. indica, leading to the identification of 24 potential NAIs. Furthermore, 9 compounds are isolated and elucidated by NMR, among which 7 compounds were identified as NAIs for the first time. In addition, an in vitro bioassay of some isolated compounds revealed ellagitannins like B4 and coumaroyl flavonoids like B23 can significantly inhibit NA activities from different sources. Especially, B23 showed a similar NA inhibitory activity on both the oseltamivir sensitive and resistant virus NA with H274Y mutation. Furthermore, B23 can obviously reduce oseltamivir sensitive and H274Y mutatant PR8 virus replication in MDCK cells. It should be noted here, although oseltamivir can inhibited the NA activities at nanomolar range, but 100 μmol/L of oseltamivir only reduces 50% PR8 viral replication, and didn't show obvious anti-virus effects on the resistant virus with NA H274Y mutation (Fig. 6), since oseltamivir can't inhibit virus infection to adjacent cells via cell-to-cell transmission32. This distinction underlined that B23 should have some special anti-virus mechanism relating NA inhibition. Besides, our toxic test revealed that B23 showed no toxicities until to 1 mmol/L concentration (data not shown). The in vitro and in vivo anti-influenza activities of some lead compounds, as well as their anti-influenza mechanisms are currently ongoing.

Acknowledgments

This research work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation, China (81872830, 31970884, and U1801287), the International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of Guangzhou, China (201807010022), and National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2019A1515011489).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.04.001.

Contributor Information

Chufang Li, Email: li_chufang@163.com.

Zhengjin Jiang, Email: jzjjackson@hotmail.com.

Haiyan Tian, Email: tianhaiyan1982@163.com.

Author contributions

Luo Sifan: investigation and visualization; Linbo Guo: investigation; Caimin Sheng: investigation; Yumei Zhao: validation; Ling Chen: resources; Chufang Li: conceptualization and methodology; Zhengjin Jiang: conceptualization and supervision; Haiyan Tian: conceptualization, methodology, and original draft preparation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Paules C., Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390:697–708. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ge H., Wang Y.F., Xu J., Gu Q., Liu H.B., Xiao P.G. Anti-influenza agents from traditional Chinese medicine. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:1758–1780. doi: 10.1039/c0np00005a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grienke U., Schmidtke M., von Grafenstein S., Kirchmair J., Liedl K.R., Rollinger J.M. Influenza neuraminidase: a druggable target for natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:11–36. doi: 10.1039/c1np00053e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watanabe A., Chang S.C., Kim M.J., Chu D.W., Ohashi Y., Laninamivir Prophylaxis Study Group Long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor laninamivir octanoate versus oseltamivir for treatment of influenza: a double-blind, randomized, noninferiority clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1167–1175. doi: 10.1086/656802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobson J., Whitley R.J., Pocock S., Monto A.S. Oseltamivir treatment for influenza in adults: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2015;385:1729–1737. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X., Jia W., Zhao A., Wang X. Anti-influenza agents from plants and traditional Chinese medicine. Phytother Res. 2006;20:335–341. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng L., Guo Q., Liu Y., Chen M., Li Y., Jiang J. Indole alkaloid sulfonic acids from an aqueous extract of Isatis indigotica roots and their antiviral activity. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2017;7:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin J., Ma L., Wang H., Yan H., Hu J., Jiang W. Chinese herbal medicine compound Yi-Zhi-Hao pellet inhibits replication of influenza virus infection through activation of heme oxygenase-1. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2017;7:630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu M., Dong X., Guo M. Phenolic profiling of Duchesnea indica combining macroporous resin chromatography (MRC) with HPLC–ESI-MS/MS and ESI-IT-MS. Molecules. 2015;20:22463–22475. doi: 10.3390/molecules201219859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian L., Wang Z., Wu H., Wang S., Wang Y., Wang Y. Evaluation of the anti-neuraminidase activity of the traditional Chinese medicines and determination of the anti-influenza A virus effects of the neuraminidase inhibitory TCMs in vitro and in vivo. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaudencio S.P., Pereira F. Dereplication: racing to speed up the natural products discovery process. Nat Prod Rep. 2015;32:779–810. doi: 10.1039/c4np00134f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arai M.A., Ishikawa N., Tanaka M., Uemura K., Sugimitsu N., Suganami A. Hes1 inhibitor isolated by target protein oriented natural products isolation (TPO-NAPI) of differentiation activators of neural stem cells. Chem Sci. 2016;7:1514–1520. doi: 10.1039/c5sc03540f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciesla L., Moaddel R. Comparison of analytical techniques for the identification of bioactive compounds from natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2016;33:1131–1145. doi: 10.1039/c6np00016a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y.M., Wang L.H., Luo S.F., Wang Q.Q., Moaddel R., Zhang T.T. Magnetic beads-based neuraminidase enzyme microreactor as a drug discovery tool for screening inhibitors from compound libraries and fishing ligands from natural products. J Chromatogr A. 2018;1568:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vavricka C.J., Liu Y., Kiyota H., Sriwilaijaroen N., Qi J., Tanaka K. Influenza neuraminidase operates via a nucleophilic mechanism and can be targeted by covalent inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1491. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potier M., Mameli L., Belisle M., Dallaire L., Melancon S. Fluorometric assay of neuraminidase with a sodium (4-methylumbelliferyl-α-d-N-acetylneuraminate) substrate. Anal Biochem. 1979;94:287–296. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duhrkop K., Fleischauer M., Ludwig M., Aksenov A.A., Melnik A.V., Meusel M. SIRIUS 4: a rapid tool for turning tandem mass spectra into metabolite structure information. Nat Methods. 2019;16:299–302. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duhrkop K., Shen H., Meusel M., Rousu J., Bocker S. Searching molecular structure databases with tandem mass spectra using CSI:FingerID. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:12580–12585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509788112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seeram N.P., Lee R., Scheuller H.S., Heber D. Identification of phenolic compounds in strawberries by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2006;97:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wendong X.U., Houwen L.I.N., Feng Q.I.U., Wansheng C. Chemical constituents of Duchesnea indica Focke. J Shenyang Pharm Univ. 2007;24:402–406. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S., Hao L.J., Zhu J.J., Wang Z.M., Zhang X., Song X.M. Comparative evaluation of Chrysanthemum Flos from different origins by HPLC–DAD–MSn and relative response factors. Food Anal Method. 2015;8:40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yagi K., Goto K., Nanjo F. Identification of a major polyphenol and polyphenolic composition in leaves of Camellia irrawadiensis. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2009;57:1284–1288. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pang K.C., Kim M.S., Lee M.W. Hydrolyzable tannins from the fruits of Rubus coreanum. Korean J Pharmacogn. 1996;27:366–370. [Google Scholar]

- 24.N’guessan J., Bidié A., Lenta B., Weniger B., André P., Guédé-Guina F. In vitro assays for bioactivity-guided isolation of antisalmonella and antioxidant compounds in Thonningia sanguinea flowers. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:1685–1689. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudjaroen Y., Hull W.E., Erben G., Wurtele G., Changbumrung S., Ulrich C.M. Isolation and characterization of ellagitannins as the major polyphenolic components of Longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour) seeds. Phytochemistry. 2012;77:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung M., Park M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition by flavonoids from Agrimonia pilosa. Molecules. 2007;12:2130–2139. doi: 10.3390/12092130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yean M.H., Kim J.S., Hyun Y.J., Hyun J.W., Bae K.H., Kang S.S. Terpenoids and phenolics from Geum japonicum. Korean J Pharmacogn. 2012;43:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saha R.K., Takahashi T., Kurebayashi Y., Fukushima K., Minami A., Kinbara N. Antiviral effect of strictinin on influenza virus replication. Antivir Res. 2010;88:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran T.T., Kim M., Jang Y., Lee H.W., Nguyen H.T., Nguyen T.N. Characterization and mechanisms of antiinfluenza virus metabolites isolated from the Vietnamese medicinal plant Polygonum chinense. BMC Compl Alternative Med. 2017;17:162/1–/11. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1675-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bao J., Marathe B., Govorkova E.A., Zheng J.J. Drug repurposing identifies inhibitors of oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:3438–3441. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen Z., Lou K., Wang W. New small-molecule drug design strategies for fighting resistant influenza A. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori K., Murano K., Ohniwa R.L., Kawaguchi A., Nagata K. Oseltamivir expands quasispecies of influenza virus through cell-to-cell transmission. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9163. doi: 10.1038/srep09163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.