Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic and irreversible neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive deficiency and development of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, comprising hyperphosphorylated tau. The number of patients with AD is alarmingly increasing worldwide; currently, at least 50 million people are thought to be living with AD. The mutations or alterations in amyloid-β precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PSEN1), or presenilin-2 (PSEN2) genes are known to be associated with the pathophysiology of AD. Effective medication for AD is still elusive and many gene-targeted clinical trials have failed to meet the expected efficiency standards. The genome editing tool clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 has been emerging as a powerful technology to correct anomalous genetic functions and is now widely applied to the study of AD. This simple yet powerful tool for editing genes showed the huge potential to correct the unwanted mutations in AD-associated genes such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2. So, it has opened a new door for the development of empirical AD models, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic lines in studying the complexity of the nervous system ranging from different cell types (in vitro) to animals (in vivo). This review was undertaken to study the related mechanisms and likely applications of CRISPR-Cas9 as an effective therapeutic tool in treating AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Clinical trial, CRISPR-Cas9, Genome editing, Therapeutic tool

Key Summary Points

| At present, over 50 million people have dementia globally and this figure will be beyond 131 million by 2050 with a global cost of around US$818 billion |

| Mutations or alterations in amyloid-β precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PSEN1), or presenilin-2 (PSEN2) genes are known factors associated with the pathophysiology of AD |

| Yet there are no effective and stable therapeutic strategies for AD and the failure rate in clinical trials (99.5%) is higher than any other disease |

| Genome editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 has been emerging as a powerful technology to correct anomalous genetic functions and is now widely applied to the study of AD |

| Off-target mutations are one of the biggest hurdles that can impair the functionality of edited cells; that is why gene delivery to the target sites of cells might be futile |

| Non-viral vectors (nanocomplexes, nanoclews, gold nanoparticles) show better efficacy and safety than viral vectors |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features (summary slide) to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.13020026.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that typically affects the adults of society and is the most common reason for dementia [1]. It is the sixth leading cause of death in the USA. Often, families with anyone suffering from AD have to pay a huge financial price as extra care and attention is required for the management of those patients with AD [2]. Reports forecast that in the future, this financial crisis among the affected communities will rise extensively at domestic and international level [3]. Currently, over 46 million people have dementia and this figure will be beyond 131 million by 2050 with a global cost of around US$818 billion [4]. Similar observations have been made in Bangladesh where more than 450,000 people live with different types of dementia. Patients with AD experience symptoms including cognitive decline, memory loss, and changes of behavior with language, mood, movement, and physiological dysfunction [5, 6]. The pathological hallmarks of AD are extracellular senile plaques largely composed of amyloid-β peptides and intracellular hyperphosphorylated neurofibrillary tangles rich in tau protein [7, 8]. Several structures of Aβ were observed to prompt cellular dysfunction and toxicity in vitro and in vivo [9].

Increase of age is the best-known risk factor for AD. On the basis of age, AD cases are generally categorized into two groups: early-onset AD (EOAD) that usually starts early in one’s life (before 65 years) and late-onset (LOAD) or sporadic AD (SAD) that commonly starts after 65 years [10]. Furthermore, different non-genetic factors including oxidative stress, inflammation, lipid metabolism, and gene–environment interactions are responsible for inducing the disease [11]. Genetically most EOAD is caused by dominantly inherited mutations in amyloid-β precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PSEN1), and presenilin-2 (PSEN2) genes. Globally more than 400 mutations were reported in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes that result in change of Aβ production level (alzforum.org/mutations) [11]. Perhaps, elevated levels of Aβ42 or altered Aβ42/40 ratios by a mutation in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes are the pieces of evidence that hinted about the pathogenicity behind AD [12]. Although the pathogenicity for sporadic LOAD is complex to understand and the main genetic factor is still unknown, various genes were nevertheless identified which are linked to the disease onset. Over 20 genetic loci together with apolipoprotein E (APOE) have been identified by genome-wide association studies which increase the risk of LOAD by causing excess production of Aβ and clearance [13].

A site-directed mutagenesis in vitro study showed an extended level of Aβ42 production in plasma from different cell lines which can be correlated with in vivo data. The well-known model mutations of the APP gene are KM670/671NL (“Swedish APP” for HEK293) and V717I which demonstrated an elevated Aβ42/40 ratio [14, 15].

The diagnosis of AD is still perplexing and depends on clinical symptoms. Current understanding indicates that biomarkers have a significant role in the identification of the pathogenic development of AD through clinical tests of blood-based and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers or molecular imaging systems that are also being used to infer the disease etiology [16]. The role of biomarkers in diagnostic may vary slightly at each stage of the disease and in the development of pathological variations of AD in the preclinical stage, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia stages [17]. A similar pattern was seen in drug development to treat AD. Yet, there are no effective and stable therapeutic strategies for AD and the failure rate in clinical trials (99.5%) is higher than any other disease for the years 2002–2012 [18]. In the last decade, over 200 research investigations were futile or have been dumped. The most likely reasons for failures of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) for AD might include starting of treatments late during the course of AD progress, inappropriate drug doses, invalid target selection, and predominantly an insufficient knowledge of the complex pathophysiology of AD, which may require specific and combination treatments [19].

Insightful observation of AD and its relevant pathways can be explored through in vitro study and the findings may help to discover potential diagnostic and therapeutic tools in vivo. However, to be optimistic, a newly developed gene editing system called clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 is presenting its great potential to be employed in the study of mutagenesis and neurodegenerative disorders.

At present, CRISPR-Cas9 is such a promising gene editing tool that reasonably can be applied as a therapeutic mediator of AD because of the greater capability of this tool to correct a mutation in the genome of brain cells [20]. AD model generation with the CRISPR-Cas9 system is gradually proving its acceptability for analyzing disease pathogenesis, phenotypes, and therapies [21]. CRISPR-Cas9 has been used to make a model of the APP and PSEN1 mutations and displayed a precise strategy of genome editing using gRNA synthesis [22]. CRISPR-Cas9 can target any gene of different cell lines, tissues, or animal model for modification, and allows a new roadmap for AD research.

In this review, we summarize the mechanism of and collected information on the potential applications of CRISPR-Cas9 to edit the genomes for AD specifically in vitro or in vivo. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9

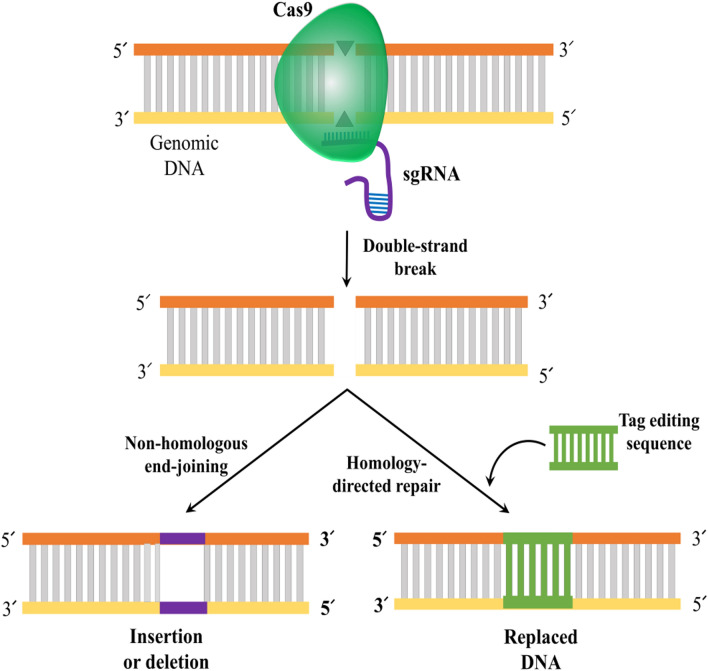

The CRISPR-Cas9 system was discovered from the adaptive immune system of prokaryotes, basically from that of bacteria and archaea [23]. Type II CRISPR-Cas9 is a commonly used system that consists of three core components: the endonuclease Cas9, CRISPR RNA (crRNA), and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [24]. Among these three components, Cas9 is an enzyme responsible for cleaving the target DNA and consists of six domains: (i) REC I, (ii) REC II, (iii) bridge helix, (iv) protospacer adjacent motif (PAM)-interacting domain, (v) HNH, and (vi) RuvC [25]. REC I domain helps the guide RNA to bind with the target sequence. The arginine-rich bridge helix is critical for initiating cleavage activity upon binding of target DNA and the PAM-interacting domain is subsequently responsible for initiating the binding with target DNA. crRNA–tracrRNA duplex can be fused to form a chimeric single guide RNA (sgRNA) for the successful development in genome engineering [24, 25]. The sgRNA consists of a 20-nucleotide guide sequence that is complementary to the target site. When the sgRNA recognizes the target sequence, it binds by Watson–Crick base-pairing and guides Cas9 to cleave the DNA strand and forms a double-stranded break (DSB) at the target site. RuvC and HNH nuclease domains are responsible for cutting the target DNA. Two major repair mechanisms are mainly responsible for repairing the breaks: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR) (Fig. 1) [26].

Fig. 1.

Genome editing mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9. Cas9 identifies its DNA-binding sites and single guide RNA (sgRNA) binds with a piece of complementary genomic DNA via RNA–DNA complex. Cas9 endonucleases create a double-strand break resulting in DNA mutagenesis through either error-prone NHEJ or the HDR pathway. NHEJ repair is the outcome of insertion or deletion (indel) mutations that can lead to a frameshift mutation. Alternatively, the HDR pathway can be used to introduce precise genetic modifications when a homologous DNA template is present

The HDR repair mechanism uses a donor DNA template to precisely repair DSBs for gene modification with low efficiency, whereas the NHEJ repair mechanism frequently results in genomic insertions or deletions (indels) for gene disruption with higher efficiency. Normally, the NHEJ is error-prone and can directly join the break sequences; it also can introduce random insertions or deletions (indels) at the DSB site [27]. High-efficiency cleavage of any target sequence can easily be achieved by combining the expression of sgRNA and Cas9 [28].

Study in Early-Onset AD (EOAD) Models

Generally early-onset dominant familial forms of AD can be initiated by point mutations or deletions in the genes responsible for amyloid precursor protein APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 [29]. The majority of cases or factors which induce AD remain unknown. Though more than 300 mutations were detected in the PSEN1 gene, those support a common cause of early-onset disease; whereas a missense mutation in PSEN2 is a rare cause of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (https://www.alzforum.org/mutations). Both PSEN1 and PSEN2 are a subunit of γ-secretase which leads to the heightened production of β-amyloid peptide [30]. Authors [31] also reported that mutations of these two genes cause enhanced production of β-amyloid perhaps by shifting the cleavage site in APP. CRISPR-cas9 can potentially correct these types of mutations. CRISPR-Cas9 was used to correct a PSEN2 dominant mutation in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons generated from basal forebrain cholinergic iPSC neurons of an individual carrying the PSEN2N141I mutation [32] (Fig. 2).

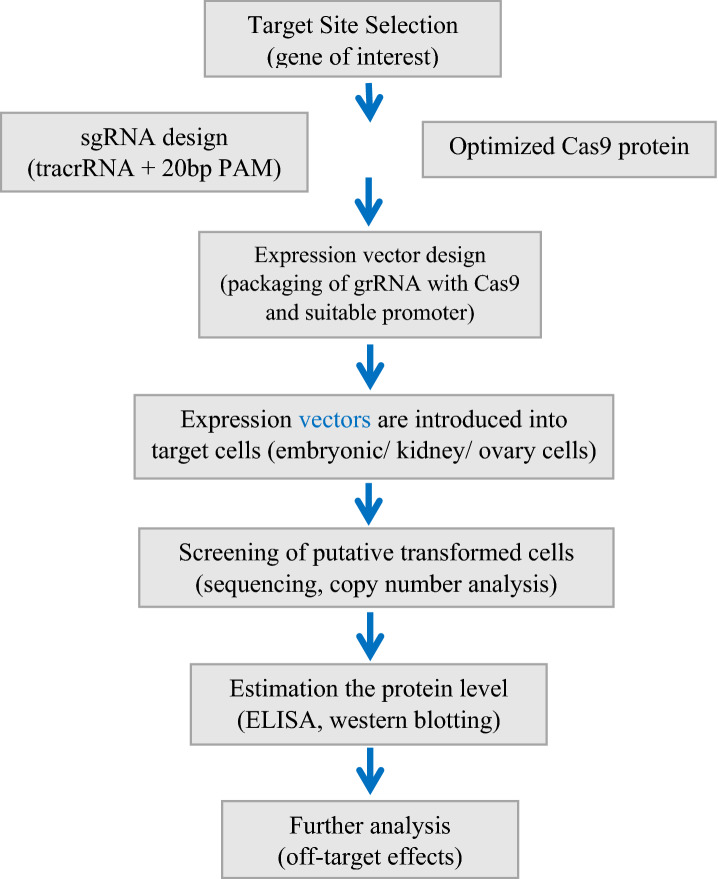

Fig. 2.

Basic flowchart of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome modification in the target cell for AD. After the selection of the target site, sgRNAs are designed using various bioinformatic tools and packed into specific expression vectors with optimized Cas9. After delivery into target cells, putative transformant cells can be screened and validated (next gene sequencing ELISA, copy number analysis, etc.)

It is also possible to target the APPSwe mutation in patients with AD by the CRISPR-Cas9 system that accounts for selective disruption of the mutated allele, leaving the wild-type alleles intact which abrogate Aβ formation. The Swedish mutation that is immediately adjacent to the β-secretase site in APP is actually a double mutation resulting from the substitution of two amino acids, lysine and methionine to asparagine and leucine, respectively [29, 33]. György et al. designated a vector with coding sequences for the APPSwe-specific guide RNA and Cas9 in adeno-associated viral (AAV) carrier and injected it into the hippocampus of transgenic mice. Those authors were able to show some disruption of the APP Swedish gene, mostly in the form of single base pair insertions and thereby decreased pathogenic Aβ formation [29].

Study in Sporadic AD (SAD) Models

SAD is a multifactorial disease and different rare genetic variants (70%) with environmental factors (30%), such as diet, toxic chemicals, and hormonal factors, may simultaneously induce the SAD [34, 35]. The major risk factors for late-onset AD are the apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) allele and mutation in the APOE gene that transcribes apolipoprotein E protein [36, 37]. Human APOE is polymorphic with three major isoforms, APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4 [38]. The scarcest form of APOE is E2 while carrying one copy seems to reduce the risk of developing AD by up to 40%. APOE3 is the normal form and does not appear as a risk factor but APOE4 exists in nearly 10–15% of people, increasing the risk for AD. The presence of one copy of E4 (E3/E4) might increase the risk by 2–3 times and the incidence of two copies of E4 (E4/E4) escalates the risk up to 10–15 times [36, 39]. Mostly adverse effects of APOE4 appear to be linked with β-amyloid; a new finding supports that APOE4 may stimulate disease pathology such as tau phosphorylation in human iPSC-derived neurons [40]. The CRISPR-Cas9 system has the capability to convert APOE4 to APOE2 or E3 form. Structural and functional alteration of APOE4 to APOE3 or APOE2 through CRISPR-Cas9 may be a viable approach to allow recovery from AD in carriers of APOE4 [20]. Wang et al. demonstrated that altering APOE4 to APOE3 by CRISPR-Cas9 prevents the pathology connected with APOE4 in a model system [40]. Moreover, many new associated genes including ABCA7, BIN1, CASS4, CELF1, CD33, CD2AP, CELF1, BIN1, PICALM, EPHA1, SORL1, CR1, EPHA1, HLA, IL1RAP, INPP5D, MS4A, TREM2, and TREM2L have been identified that are involved in neuroinflammation in AD [13, 41–44].

Delivery System of CRISPR-Cas9 in AD

CRISPR-Cas9 is a promising genome editing approach for therapeutic treatment of AD. However, a safe and efficient delivery system is still a big challenge that needs to be updated to translate this technology into real-life applications. The CRISPR-Cas9 system can be delivered via viral or non-viral approaches.

Viral Vectors

Using viral vectors to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 is a classical approach in vitro and in vivo. Viral vectors are the most efficient delivery systems of the plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas9 system. However, they can introduce accidental mutations with serious side effects. The most commonly used viral vector is AAV owing to its mild immunogenicity, high infection ability, and inefficient to integrate into the human genome generally [45, 46]. The AAV genome consists of a single-stranded DNA, with greater than 200 variants [47].

The viruses were tested in vitro and in vivo via intrahippocampal injection in Tg2576 mice. This treatment led to a 60% reduction in Aβ production in the human-derived fibroblasts [29]. As AAV has a lower packaging capacity of only 4.7 kb, the co-injection of two viruses might be necessary, which complicates the process as both might not infect the same cell simultaneously. Compared to AAV, lentivirus is comparatively difficult to purify in large quantities and is more likely to provoke immune reactions and integrate into the human genome at high efficiency [46]. However, incorporation of long DNA inserts (8–10 kb) is possible into lentivirus, but with a lower brain spreading efficiency [48]. Researchers showed the possibility of using lentivirus to target three different genes in SAD and familial AD, which are APP, APOE E4, and caspase-6 [49–51].

Non-Viral Vectors

Non-viral vectors offer higher well-being, better cost-adequacy, and flexibility as far as the size of the transgenic part. Subsequently, they are more appropriate for applications in AD. Nanocomplexes can easily be formed by complexing the negatively charged nucleic acid cargo with the positively charged peptides of CRISPR-Cas9. They are known to be less immunogenic than the viral vectors. As they can work with ligands, they would serve various applications.

However, it is challenging to deliver nanocomplexes to the brain, as they cannot cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) efficiently via the systemic route, and they get actively removed from the blood circulation by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). Therefore, intrathecal and intracerebroventricular injections are typically used. Direct injection methods, however, require multiple injections to achieve a proper distribution across the brain, limiting their applicability. Park et al. [52] prepared nanocomplexes made of R7L10 peptide complexed with Cas9–sgRNA ribonucleoprotein targeting the specific gene BACE1. They state that the nanocomplexes successfully targeted the BACE1 gene, attenuating the expression without a significant off-target mutation rate in vivo.

Aside from CRISP-Cas9 delivery, other vehicles conveying short interfering RNAs (siRNA) have been created to target AD across the BBB. Polymeric nanocomplexes of poly(mannitol-co-polyethylenimine) carrier (PMT) modified with rabies infection glycoprotein (RVG) have recently been reported [48]. The polymer is complexed to siRNA against BACE1. The nanocomplexes were proposed to have an improved conveyance ability because of the RVG ligand, which improves BBB crossing and focuses on neuronal cells. Transfection efficiency is diminished by polyethylene glycol (PEG) as it creates a positively charged shield thwarting connection to cell membranes. It was proposed that the RVG ligand overcomes this issue, thereby improving the cellular uptake of the nanocomplexes. The silencing capability of nanocomplexes was further verified by the reduction of Aβ1-42 levels in the brain cortices. An unknown body distribution may lead to a significant loss of therapeutic potential, since the adequacy of such a delivery system ought to be explored in AD models because AD affects the permeability of the BBB, and could potentially impact the targeting and viability of nanocomplexes.

The following delivery systems could be promising for applications in AD.

DNA nanoclews can be a possible methodology for conveying the Cas9–sgRNA complex. The traditional assembly of DNA nanostructures is based on base-pairing, which is complicated and time-consuming. DNA nanoclews, which were first reported by Sun et al. [53], are nanosized confined DNA moieties that contain polyethylenimine to apply a positive charge for better endosomal escape and cell uptake. Nanoclews carrying sgRNA–Cas9 complex targeting enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) were locally injected into the tumors of EGFP tumor-bearing mice and manifested about a 25% decreased expression of EGFP 10 days post treatment [53]. Despite their advantages, nanoclews might induce immunogenic reactions that still require further investigation.

Lipid nanoparticles and polymeric nanoparticles have potential as CRISPR-Cas9 delivery tools as well. They have been extensively employed before delivering gene editing cargos in cancer [54], hepatitis, and other viral conditions [55]. However, their possible application in AD management remains to be investigated.

Gold nanoparticles have additionally been used in an investigation by Wang et al. [56]. CRISPR-Gold targeting the CXCR4 gene attained 3–4% HDR efficiency in numerous human cell types. A single local infusion of CRISPR-Gold into the gastrocnemius and tibialis frontal muscle in mdx mice was able to correct the mutated dystrophin gene which is responsible for inborn Duchenne muscular dystrophy [56]. Moreover, the inflammatory cytokine profile did not meaningfully change after the injection of CRISPR-Gold, indicating the latter’s tolerability and low toxicity.

Recently, the use of microvesicles for CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutics delivery has attracted attention. Generally, a “producer” cell line is transfected with sgRNA, Cas9 protein, and a microvesicle-prompting protein (RAB proteins) [57]. The cells produce microvesicles containing the Cas9–sgRNA complex. Microvesicles get shed into the medium and which is consequently decontaminated and re-used to convey their gene-altering load to the target cells.

Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in AD

The CRISPR-Cas9 technique can be used for therapeutic purposes in both early-onset and sporadic AD models. CRISPR can effectively target any specific gene sequences to correct mutation and introduce genetic elements to the target regions of DNA in the cells or tissues. This tool is showing efficiency to generate better cellular and molecular replicas, knock out function, explore the fatal neuronal damage, mimic the disease model, and insert the guide gene sequence into the genome [58, 59]. CRISPR-Cas9 is capable of carrying out the whole screening of associations between the risk variants and the cellular pathways, the pathogenesis-related specific pathways, and the phenotypic variations [60]. CRISPR-Cas9 has been applied to correct certain gene sequences and demonstrated significant consequences for AD (Table 1). It has been largely trialed both in vitro and in vivo. Knock-in mice models were developed with CRISPR-Cas9 components that transfected successfully and reported competent results [61, 62]. Different studies already revealed that physiological effects of Aβ and abnormal misfolded Aβ protein generation can be normalized and controlled through the CRISPR-Cas9 system [63, 64]. This technique also could be involved in epigenetic modifications and has been applied to edit a gene in post-mitotic neurons of the adult brain [52], correct endogenous APP at the extreme C-terminus that reciprocally manipulates the amyloid pathway [65], and improve astrocyte capacity to clear the accumulated Aβ by knocking down calpain [66]. CRISPR-Cas9 gives a positive indication in treating AD from those studies. Currently, an alternative cell-based therapy is under trial to enable the reversal of neurodegeneration in AD.

Table 1.

Clinical trials with CRISPR-Cas9 for Alzheimer’s disease

| Targeted genes for CRISPR-Cas9 | Mutations that can be corrected with CRISPR-Cas9 | Consequences | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| APP | Deletion of Swedish mutation | Reduced pathogenic Aβ production ex vivo and in vivo | [29] |

| APP | Several mutations (T48P, L52P, and K53N) | Made a model for the impact of APP mutations in γ-secretase cleavage and notch processing | [73] |

| APOE | APOE E4 allele to E3 allele | Conversion of Arg158 to Cys158 in 58–75% | [74] |

| PSEN1 | Met146Val | More efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations | [14] |

| PSEN2 | N141I | Increased Aβ42/40 was normalized through CRISPR-Cas to correct the mutation of PSEN2N141I | [32] |

| APP | Reciprocally manipulate the amyloid pathway | Attenuating β-cleavage and Aβ production | [65] |

| APPS | Homology-directed repair (HDR)-mediated mutation | Disease models generated by CRISPR | [22] |

| PSEN1M1 | Homology-directed repair (HDR)-mediated mutation | Disease models generated by CRISPR | [22] |

| MAPT | Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-mediated exon removal | Generation of a new Tau knockout (tau∆ex1) line in mice | [75] |

| Bace1 | Manipulation amyloid-β (Aβ)-associated pathologies | Significant reduction of Aβ42 plaque accumulation in mice | [52] |

| PSEN2 | PSEN2N141I mutation | Reduction in the Aβ42/40 ratio | [76] |

New In Vitro, In Vivo, and Clinical Model Development Using CRISPR

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has achieved reliability in genome modification and can correct the genome of different cells and animals such as human pluripotent cells, somatic cells, zebrafish, mice, and pigs. CRISPR-Cas9 has shown its suitability for the generation of isogenic human iPSC lines. Currently, this technique helps to understand the effect of specific mutations in cells and tissues which could be generated in “diseased” and “healthy” cell lines with the same set of genes [63, 67].

PSCs were developed for studying neurodegenerative diseases including AD. Paquet used for the first time the CRISPR-Cas9 approach for the generation of human iPSCs with heterozygous and homozygous dominant early-onset Alzheimer’s disease-causing mutations in APP (APPSwe) and PSEN1 (PSEN1M146V). They evaluated the Aβ42 intensities and Aβ42/40 ratio in human in APPSwe and PSENM146V knock-in cell lines. While neuronal differentiation in those iPSCs happened, the derived cortical neurons showed genotype-dependent disease-associated phenotypes revealed by the altered Aβ metabolism [22].

Sun and his team generated 138 mutations in PSEN1 from neuroblastoma (N2a) cell lines and applied the CRISPR-Cas9 system to create mutant cells. This finding evaluated the gain or loss of function effects of mutations depending on amyloid production and the Aβ42/40 ratio [68].

Sigma-1 receptor (S1R) is a transmembrane protein located at the endoplasmic reticulum and plays a role in the stability of mushroom spines in hippocampal neurons. The agonists of the receptor display neuroprotective properties in cellular and animal models of AD [69]. Ryskamp et al. studied the association of S1R in the maintenance of mushroom spine stability in hippocampal neurons from wild-type or PSEN1 knock-in mice using CRISPR-Cas9 [70]. CRISPR-Cas9 could also target the nerve cells in older animals. It is thought swine disease models may replicate the phenotypes of human diseases more faithfully than mice models. Using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, Holm et al. endeavored to produce transgenic pigs expressing disease-associated mutations in 2016 [71]. Sasaguri et al. applied this tool in which catalytically deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) or Cas9 nickase (nCas9) was united with cytidine deaminases to transform C:G base pairs to T:A base pairs at target sites with a reduced rate of indel formation in the presence of sgRNAs, for production of multiple animal models with a number of distinct disease-related and disease-unrelated point mutations in the PSEN1 and APP genes. To create this, they inoculated RNA solutions containing several types of base editors and sgRNAs into the cytoplasm of C57BL/6J zygotes and then embryos at the 2-cell-stage were transported to host ICR female mice. Later, they analyzed the functional consequences of these mutations in vivo and found higher levels of Aβ42 [72].

In vivo genome editing in post-mitotic neurons of the older brain may be a beneficial approach for handling neurological diseases. In this process, CRISPR-Cas9 nanocomplexes composed of R7L10 peptide complexed with Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein showed efficacy in the adult mouse brain, with the lowest off-target consequences. CRISPR-Cas9 nanocomplexes target BACE1-suppressed Aβ-associated pathologies and cognitive deficits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Park et al. examined CRISPR-Cas9-loaded nanocomplexes that can efficiently target BACE1 in the post-mitotic neurons of the adult mouse brain and reveal their therapeutic application in five familial Alzheimer’s disease (5XFAD) and APP knock-in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models [52].

Challenges and Future Directions

CRISPR has gained keen attention as a therapeutic tool for genome editing in mammals and is experiencing prominent growth by implementation and trials. There are still many relevant shortcomings that must be overcome before their clinical implementation in the treatment of AD. Nowadays, gene therapy possesses the potential to reverse several degenerative disorders; nevertheless, current use is limited because of practical challenges. CRISPR technology application in AD is under challenge since most of the AD cases are sporadic and have various unidentified causes. Only a small (> 0.1%) percentage of patients have a mutation in the gene encoding APPs [77]. Additionally, there is uncertainty in getting optimum identified subjects who can be diagnosed and treated earlier in the course of symptomatic diseases [78]. Researchers have found maximum late-onset AD progress for a long time before the clinical manifestation of symptoms, thereby creating an uncertain window for intervention [79].

The specificity and sensitivity of CRISPR-Cas9 are a basic priority for its therapeutic action. In this matter, off-target mutations are one of the biggest hurdles that can impair the functionality of edited cells; that is why gene delivery to the target sites of cells might be futile. The outcome of aimless or off-targeting events induces an adverse iatrogenic effect in healthy tissue, which could potentiate germline mutations [80]. Cho et al. stated that off-target cleavage was almost untraceable when cleavage sites are unique with homologous sequences absent elsewhere in the genome [81]. Lack of complete knowledge of CNS biomarkers is another major barrier for proper cell targeting and cell signaling responses; however, improvements in CSF biomarker, brain imaging, and diversified vector modeling are poised to improve the specificity [82].

A range of sensitive readout methods for identifying genome-wide Cas9 off-target activity have been developed that provide useful tools for evaluating specificity and safety of Cas9 applications in basic and clinical research [83, 84]. On-target specificity can be further improved by using double-nicking [85, 86] or truncated sgRNA approaches [87, 88]. They managed to perform seventh-generation adenine base editing (ABEs), allowing the conversion of A-T to G-C in genomic DNA by RNA adenosine deaminase to operate in DNA, through the fusion of a CRISPR-Cas9 mutant to its catalytic site. The results exhibited 50% editing efficiency in human cells with high purity (99%) and low rates of indels (0.01%), producing a more efficient approach for the introduction of specific mutations.

In AD treatment, all sorts of endeavors need to reach affected cells in the CNS, which have complexity and cellular diversity posing the additional challenge of penetrating the BBB [89]. To sort out the targeted cells a proficient method was developed; fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) is used to illuminate fluorophore-tagged nuclei of target cells to allow purification and path-imaging of genomic DNA and nuclear RNA. Swiech et al. interrogated an in vivo genome assay where AAV containing SpCas9-sgRNAs applied via stereotactic injection, targeting MECP2, Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b genes in the adult mice brain, and they found multiple-gene modification in post-mitotic neurons in brain imaging [90].

Designing an efficient delivery system that encodes gRNA and Cas9 is vital for transfection and gene editing events. Though various viral and non-viral vectors were developed strategically, efficient and specific gene replacement is quite perplexing, and ideal delivery systems remain to be developed. In vivo gene editing in post-mitotic cells has not been perfected yet, and virus-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 editing is associated with complications owing to the integration of carriers into the host genome, so the risk of an immune response against Cas9 should be addressed. In vivo delivery utilizing a virus vector can trigger an intense immune response if the therapy does not become successful; when in vivo gene editing is concerned, immunogenicity issues associated with the Cas9 protein should be considered [91]. Similarly, it has been found that AAV vectors have limited transgene capacity and the large size of the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes) Cas9 variant poses a significant challenge for AAV-mediated delivery [90]. Plasmids containing gRNA and Staphylococcus aureus sequences might be integrated into host genome randomly, resulting in recognition problems and may show the toxic effect to host cells [11]. Smaller Cas9 orthologous, such as those derived from S. aureus, are easier to pack [92], making them an attractive option for in vivo genome editing in the brain. Charlesworth et al. [93] showed the presence of humoral responses and specific antigen presenting T cells against SaCas9 (Cas derivative of S. aureus) in a healthy human [93]. Delivery of genetically engineered gene therapy vector using adeno-associated virus serotype 2 delivering NGF demonstrated promising results and there was no evidence of accelerated decline post gene therapy delivery [94].

CRISPR-based gene editing in microglial cells as therapeutics has proven to be challenging. Researchers assayed in vitro microglial cell gene editing using two different approaches to achieve GMF gene editing in BV2 microglial cells: the first approach used AAV-SaCas9-GMF-sgRNA and the second approach used a dual lentiviral vector system (LV-EF1α-Cas9) that expresses S. pyogenes Cas9. They got valid findings and confirmed successful GMF gene editing in BV2 cells, which might lead to developing the next generation of personalized molecular medicine for AD [95].

Some reports have indicated to improve HDR efficiency by biochemically altering the HDR or NHEJ pathways. A study in human cells explained that the use of asymmetric ssDNA donors of optimal length increased the rate of HDR by up to 60% for a single nucleotide substitution [96]. Liang et al. achieved up to 56% efficiency in precise genome editing in HEK293 cells for the cutting efficiency of gRNAs, though the HDR pathway remains a rate-limiting step for seamless genome editing [97].

However, a long path needs to be overcome when applying the CRISPR-Cas approach to treat the AD; to manipulate advanced CRISPR-Cas technology in AD modeling and therapeutics development, a plethora of open challenges have to be addressed together with safety and ethical concerns [98]. Delivering Cas9 proteins and guide RNA into brain cells must be optimized through trials to meet standard efficacy, specificity, and sensitivity requirements.

Conclusion

CRISPR-Cas9 has opened a new window for treating any target disease efficiently and can correct mutant protein expression in specific cells, tissue, or animals. It expedites the screening of probable deterioration in metabolic pathways, regulates the exposure of inflammatory molecules, and includes epigenetic modifications. It can be function on several numbers of autosomal-dominant mutations that induce early-onset AD or any genetic risk factors that relate to late-onset AD. For the CRISPR-Cas9 technique to succeed in treating AD, specific targeting genes, cell lines, expression vectors, and animal model trials need to be validated and revealed.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Nirmal Chandra Barman and Md. Niuz Morshed Khan contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures

Nirmal Chandra Barman, Md. Niuz Morshed Khan, Maidul Islam, Zulkar Nain, Rajib Kanti Roy, Md. Anwarul Haque and Shital Kumar Barman have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Jones EL, Kalaria RN, Sharp SI, O’Brien JT, Francis PT, Ballard CG. Genetic associations of autopsy-confirmed vascular dementia subtypes. Dement Geriatr Cogn. 2011;31(4):247–253. doi: 10.1159/000327171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(9):1–77. [PubMed]

- 3.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prince M, Comas-Herrera A, Knapp M, Guerchet M, Karagiannidou M. World Alzheimer report 2016: improving healthcare for people living with dementia: coverage, quality and costs now and in the future. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2016.

- 5.Budson AE, Price BH. Memory dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(7):692–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1–1. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD): part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41(4):479–479. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong S. Molecular and cellular basis of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Cells. 2017;40(9):613. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penney J, Ralvenius WT, Tsai LH. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease with iPSC-derived brain cells. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;7:1–20. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0468-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr DB, Goate A, Phil D, Morris JC. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med. 1997;103(3):3S–10S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Giau V, Lee H, Shim KH, Bagyinszky E, An SS. Genome-editing applications of CRISPR–Cas9 to promote in vitro studies of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:221. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S155145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Giau V, An SS. Optimization of specific multiplex DNA primers to detect variable CLU genomic lesions in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. BioChip J. 2015;9(4):278–284. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karch CM, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang B, Jia L, Jia J. Chinese presenilin-1 V97L mutation enhanced Aβ42 levels in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Neurosci Lett. 2006;406(1–2):33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Citron M, Oltersdorf T, Haass C, et al. Mutation of the β-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer's disease increases β-protein production. Nature. 1992;360(6405):672–674. doi: 10.1038/360672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frisoni GB, Boccardi M, Barkhof F, et al. Strategic roadmap for an early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease based on biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:661–676. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30159-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jack CR, Jr, Albert MS, et al. Introduction to revised criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer Association workgroups. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings JL, Morstorf T, Zhong K. Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimer's Res Ther. 2014;6(4):1–7. doi: 10.1186/alzrt269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yiannopoulou KG, Anastasiou AI, Zachariou V, Pelidou SH. Reasons for failed trials of disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer disease and their contribution in recent research. Biomedicines. 2019;7(4):97. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines7040097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rohn TT, Kim N, Isho NF, Mack JM. The potential of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing as a treatment strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism. 2018 doi: 10.4172/2161-0460.1000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mungenast AE, Siegert S, Tsai LH. Modeling Alzheimer's disease with human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2016;73:13–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paquet D, Kwart D, Chen A, et al. Efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations using CRISPR/Cas9. Nature. 2016;533(7601):125–129. doi: 10.1038/nature17664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315(5819):1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimasu H, Ran FA, Hsu PD, et al. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell. 2014;156(5):935–949. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan MN, Islam KK, Ashraf A, Barman NC. A review on genome editing by CRISPR-CAS9 technique for cancer treatment. World Cancer Res J. 2020;7:e1510. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen M, Mao A, Xu M, Weng Q, Mao J, Ji J. CRISPR-Cas9 for cancer therapy: opportunities and challenges. Cancer Lett. 2019;447:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lander ES. The heroes of CRISPR. Cell. 2016;164(1–2):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.György B, Lööv C, Zaborowski MP, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated disruption of the Swedish APP allele as a therapeutic approach for early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2018;11:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dabrowska M, Juzwa W, Krzyzosiak WJ, Olejniczak M. Precise excision of the CAG tract from the huntingtin gene by Cas9 nickases. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:75. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vetrivel KS, Zhang YW, Xu H, Thinakaran G. Pathological and physiological functions of presenilins. Mol Neurodegener. 2006;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortiz-Virumbrales M, Moreno CL, Kruglikov I, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-correctable mutation-related molecular and physiological phenotypes in iPSC-derived Alzheimer’s PSEN2 N141I neurons. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0475-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullan M, Crawford F, Axelman K, et al. A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer's disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of β-amyloid. Nat Genet. 1992;1(5):345–347. doi: 10.1038/ng0892-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vilatela ME, López-López M, Yescas-Gómez P. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(8):622–631. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones L, Lambert JC, Wang LS, et al. Convergent genetic and expression data implicate immunity in Alzheimer's disease. International Genomics of Alzheimer's disease Consortium (IGAP) Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(6):658–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenstein M. Genetics: finding risk factors. Nature. 2011;475(7355):S20–S22. doi: 10.1038/475S20a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolli N, Lu M, Maiti P, Rossignol J, Dunbar GL. Application of the gene editing tool, CRISPR-Cas9, for treating neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem Int. 2018;112:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weisgraber KH, Rall SC, Mahley RW. Human E apoprotein heterogeneity. Cysteine-arginine interchanges in the amino acid sequence of the apo-E isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1981;256(17):9077–9083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C, Najm R, Xu Q, et al. Gain of toxic apolipoprotein E4 effects in human iPSC-derived neurons is ameliorated by a small-molecule structure corrector. Nat Med. 2018;24(5):647–657. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0004-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carrasquillo MM, Zou F, Pankratz VS, et al. Genetic variation in PCDH11X is associated with susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41(2):192–198. doi: 10.1038/ng.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seshadri S, Fitzpatrick AL, Ikram MA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1832–1840. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramanan VK, Risacher SL, Nho K, et al. GWAS of longitudinal amyloid accumulation on 18F-florbetapir PET in Alzheimer’s disease implicates microglial activation gene IL1RAP. Brain. 2015;138(10):3076–3088. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dorszewska J, Prendecki M, Oczkowska A, Dezor M, Kozubski W. Molecular basis of familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13(9):952–963. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160314150501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaj T, Epstein BE, Schaffer DV. Genome engineering using adeno-associated virus: basic and clinical research applications. Mol Ther. 2016;24(3):458–464. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Recchia A, Perani L, Sartori D, Olgiati C, Mavilio F. Site-specific integration of functional transgenes into the human genome by adeno/AAV hybrid vectors. Mol Ther. 2004;10(4):660–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimm D, Kay MA. From virus evolution to vector revolution: use of naturally occurring serotypes of adeno-associated virus (AAV) as novel vectors for human gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2003;3(4):281–304. doi: 10.2174/1566523034578285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dissen GA, McBride J, Lomniczi A, et al. Controlled genetic manipulations. Berlin: Springer; 2012. Using lentiviral vectors as delivery vehicles for gene therapy; pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun J, Carlson-Stevermer J, Das U, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing of APP C-terminus attenuates β-cleavage and promotes α-cleavage. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1–1. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07971-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Offen D, Rabinowitz R, Michaelson D, Ben-Zur T. Towards gene-editing treatment for Alzheimer's disease: ApoE4 allele-specific knockout using a CRISPR cas9 variant. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(5):S18. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Offen D, Angel A, Ben-Zur T. Caspase-6 knock-out using CRISPR/Cas9 improves cognitive behavior in the 3xTg mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(5):S94–S95. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park H, Oh J, Shim G, et al. In vivo neuronal gene editing via CRISPR-Cas9 amphiphilic nanocomplexes alleviates deficits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(4):524–528. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun W, Ji W, Hall JM, et al. Self-assembled DNA nanoclews for the efficient delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome editing. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:12029–12033. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aghamiri S, Talaei S, Ghavidel AA, et al. Nanoparticles-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 delivery: recent advances in cancer treatment. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;56:101533. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kulkarni JA, Cullis PR, Van Der Meel R. Lipid nanoparticles enabling gene therapies: from concepts to clinical utility. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2018;28(3):146–157. doi: 10.1089/nat.2018.0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang D, Zhang F, Gao G. CRISPR-based therapeutic genome editing: strategies and in vivo delivery by AAV vectors. Cell. 2020;181(1):136–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature. 2019;576(7785):149–157. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu C, Zhang L, Liu H, Cheng K. Delivery strategies of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing system for therapeutic applications. J Control Release. 2017;266:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryan SD, Dolatabadi N, Chan SF, et al. Isogenic human iPSC Parkinson’s model shows nitrosative stress-induced dysfunction in MEF2-PGC1α transcription. Cell. 2013;155(6):1351–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dow LE, Fisher J, O’rourke KP, et al. Inducible in vivo genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(4):390–394. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doench JG, Hartenian E, Graham DB, et al. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(12):1262–1267. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pires C, Schmid B, Petræus C, et al. Generation of a gene-corrected isogenic control cell line from an Alzheimer's disease patient iPSC line carrying a A79V mutation in PSEN1. Stem Cell Res. 2016;17(2):285–288. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuruvilla J, Sasmita AO, Ling AP. Therapeutic potential of combined viral transduction and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in treating neurodegenerative diseases. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(11):1827–1835. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun J, Carlson-Stevermer J, Das U, et al. A CRISPR/Cas9 based strategy to manipulate the Alzheimer’s amyloid pathway. 2018. 10.1101/310193.

- 66.Offen D, Anidjar A, Simonovitch S, Ben-Zur T, Michaelson D. Increase in autophagy and amyloid beta uptake in apoe expressing astrocytes after calpain knock down by CRISPR-Cas9. Cytotherapy. 2019;21(5):e6. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poon A, Schmid B, Pires C, et al. Generation of a gene-corrected isogenic control hiPSC line derived from a familial Alzheimer's disease patient carrying a L150P mutation in presenilin 1. Stem Cell Res. 2016;17(3):466–469. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun L, Zhou R, Yang G, Shi Y. Analysis of 138 pathogenic mutations in presenilin-1 on the in vitro production of Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides by γ-secretase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(4):E476–E485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618657114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maurice T, Volle JN, Strehaiano M, et al. Neuroprotection in non-transgenic and transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease by positive modulation of σ1 receptors. Pharmacol Res. 2019;144:315–330. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryskamp DA, Zhemkov V, Bezprozvanny I. Mutational analysis of sigma-1 receptor’s role in synaptic stability. Front Neurosci. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holm IE, Alstrup AK, Luo Y. Genetically modified pig models for neurodegenerative disorders. J Pathol. 2016;238(2):267–287. doi: 10.1002/path.4654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sasaguri H, Nagata K, Sekiguchi M, et al. Introduction of pathogenic mutations into the mouse Psen1 gene by base editor and target-AID. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05262-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu TH, Yan Y, Kang Y, Jiang Y, Melcher K, Xu HE. Alzheimer’s disease-associated mutations increase amyloid precursor protein resistance to γ-secretase cleavage and the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. Cell Discov. 2016;2(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2016.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533(7603):420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tan D, Yao S, Ittner A, et al. Generation of a new tau knockout (tau Δex1) line using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(2):571–578. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moreno CL, Della Guardia L, Shnyder V, et al. iPSC-derived familial Alzheimer’s PSEN2 N141I cholinergic neurons exhibit mutation-dependent molecular pathology corrected by insulin signaling. Mol Neurodegener. 2018;13(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s13024-018-0265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bettens K, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C. Genetic insights in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(1):92–104. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Isik AT. Late onset Alzheimer’s disease in older people. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:307. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S11718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ross CA, Aylward EH, Wild EJ, et al. Huntington disease: natural history, biomarkers and prospects for therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(4):204–216. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O’Geen H, Abigail SY, Segal DJ. How specific is CRISPR/Cas9 really? Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2015;29:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim JM, Kim JS. Targeted genome engineering in human cells with the Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):230–232. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shen F, Fan Y, Su H, et al. Adeno-associated viral vector-mediated hypoxia-regulated VEGF gene transfer promotes angiogenesis following focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Gene Ther. 2008;15(1):30–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsai SQ, Zheng Z, Nguyen NT, et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(2):187–197. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim D, Bae S, Park J, et al. Digenome-seq: genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nat Methods. 2015;12(3):237–243. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154(6):1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, et al. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fu Y, Sander JD, Reyon D, Cascio VM, Joung JK. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(3):279–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, et al. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. 2017;551(7681):464–471. doi: 10.1038/nature24644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mikkelsen RB, Frederiksen HR, Gjerris M, et al. Genetic protection modifications: moving beyond the binary distinction between therapy and enhancement for human genome editing. CRISPR J. 2019;2(6):362–369. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2019.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Swiech L, Heidenreich M, Banerjee A, et al. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(1):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Crudele JM, Chamberlain JS. Cas9 immunity creates challenges for CRISPR gene editing therapies. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05843-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX, et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature. 2015;520(7546):186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature14299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Charlesworth CT, Deshpande PS, Dever DP, et al. Identification of preexisting adaptive immunity to Cas9 proteins in humans. Nat Med. 2019;25(2):249–254. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0326-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rafii MS, Baumann TL, Bakay RA, et al. A phase1 study of stereotactic gene delivery of AAV2-NGF for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10(5):571–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raikwar SP, Thangavel R, Dubova I, et al. Targeted gene editing of glia maturation factor in microglia: a novel Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic target. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(1):378–393. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1068-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Richardson CD, Ray GJ, DeWitt MA, Curie GL, Corn JE. Enhancing homology-directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(3):339–344. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liang X, Potter J, Kumar S, Ravinder N, Chesnut JD. Enhanced CRISPR/Cas9-mediated precise genome editing by improved design and delivery of gRNA, Cas9 nuclease, and donor DNA. J Biotechnol. 2017;241:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Setten RL, Rossi JJ, Han SP. The current state and future directions of RNAi-based therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(6):421–446. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]