Abstract

Background

Individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D) demonstrate varied trajectories of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline. The molecular pathways underlying rapid eGFR decline in T1D are poorly understood, and individual-level risk of rapid eGFR decline is difficult to predict.

Methods

We designed a case-control study with multiple exposure measurements nested within four well-characterized T1D cohorts (FinnDiane, Steno, EDC, CACTI) to identify biomarkers associated with rapid eGFR decline. Here, we report the rationale for and design of these studies as well as results of models testing associations of clinical characteristics with rapid eGFR decline in the study population, upon which “omics” studies will be built. Cases (n = 535) and controls (n = 895) were defined as having an annual eGFR decline of ≥3 ml/min/1.73m2 and <1 ml/min/1.73m2, respectively. Associations of demographic and clinical variables with rapid eGFR decline were tested using logistic regression, and prediction was evaluated using area under the curve (AUC) statistics. Targeted metabolomics, lipidomics, and proteomics are being performed using high-resolution mass-spectrometry techniques.

Results

At baseline, mean age was 43 years, diabetes duration was 27 years, eGFR was 94 ml/min/1.73m2, and 62% of participants were normoalbuminuric. Over 7.6 years median follow-up, the mean annual change in eGFR in cases and controls was −5.7 ml/min/1.73m2 and 0.6 ml/min/1.73m2, respectively. Younger age, longer diabetes duration, and higher baseline HbA1c, urine albumin-creatinine ratio, and eGFR were significantly associated with rapid eGFR decline. The cross-validated AUC for the predictive model incorporating these variables plus sex and mean arterial blood pressure was 0.74 (95% CI 0.68, 0.79; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Known risk factors provide moderate discrimination of rapid eGFR decline. Identification of blood and urine biomarkers associated with rapid eGFR decline in T1D using targeted omics strategies may provide insight into disease mechanisms and improve upon clinical predictive models using traditional risk factors.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, eGFR, biomarkers, omics

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 25-40% of individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D) develop diabetic kidney disease (DKD), defined as a reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) or onset of albuminuria [1,2]. In this population, the reported incidence of kidney failure ranges from 2-35% over 30 years of T1D duration, and up to 60% over 50 years of T1D duration [3,4].

Progressive eGFR decline is largely a monotonic process that occurs early in the course of T1 DKD [5]. The annual rate of decline varies across affected individuals, with more rapid rates conferring higher risk of kidney failure [6]. Additionally, eGFR decline may precede the onset of albuminuria, suggesting the presence of disease activity before clinical signs are apparent [5,7]. While various pathophysiological processes including hyperglycemia, microvascular dysfunction, inflammation, and fibrosis, are implicated in DKD, the mechanisms underlying the observed differential decline in kidney function across individuals remain poorly understood [8,9]. Insight into the mechanisms of eGFR decline in T1D is important for early identification of individuals at risk for DKD progression and for development of new therapies.

The search is ongoing for novel biomarkers that can parse through the heterogeneous nature of DKD pathophysiology and improve the predictive and prognostic abilities of existing clinical models for DKD progression [10]. A number of candidate biomarkers have been associated with putative pathogenic pathways (including inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and fibrosis) and functional kidney outcomes (such as eGFR decline, albuminuria, and kidney failure) in DKD [11]. However, their widespread use is limited by lack of validation and diagnostic precision [12-14].

The development of “omic” approaches has facilitated biomarker identification in DKD via quantification of low-molecular weight proteins, metabolites, and lipids in blood and urine using refined mass spectrometry techniques [15,16]. A new multidimensional urinary proteome classifier (CKD273) has identified new peptide markers of interest and demonstrated promise in detecting individuals with diabetes who are at risk for progression of DKD, though studies have primarily focused on individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [17,18]. Recently, 125 plasma amino acid, triglyceride, and lipid metabolites were cross-sectionally associated with eGFR in a large T2D meta-analyses [19]. Among individuals with T1D, use of omic technologies may allow for better characterization of the molecular pathways responsible for eGFR decline and enable application of this insight to the development of predictive models.

Recently, an international consortium funded by JDRF was established to identify metabolite, lipid, and protein markers of eGFR decline in individuals with T1D using novel multi-omics techniques. The aims of the JDRF consortium are (1) to discover and validate a set of biomarkers associated with rapid eGFR decline in T1D using novel omics platforms which may provide insight into disease mechanisms, and (2) to use resulting omics data to develop predictive models for rapid eGFR decline in T1D. In this paper, we describe the rationale, design, cohorts, and methods of the JDRF Biomarkers Consortium, and examine associations of clinical variables with rapid eGFR loss as well as prediction of eGFR loss by clinical variables to establish common, appropriate models upon which to add omics measurements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We designed a case-control study with multiple exposure measurements to test associations of blood and urine biomarkers, measured at baseline, with subsequent rapid eGFR decline in T1D. The case-control study was nested within four T1D cohorts. Cases were defined as having an annual decline in eGFR of ≥ 3 ml/min/1.73m2 and controls were defined as having an annual decline in eGFR of < 1ml/min/1.73m2. Blood and urine samples obtained at baseline are being applied to metabolomics, lipidomics, and/or proteomics platforms for measurement of pre-specified biomarkers. A discovery-validation approach will be taken to test associations of biomarkers with eGFR decline.

Study population

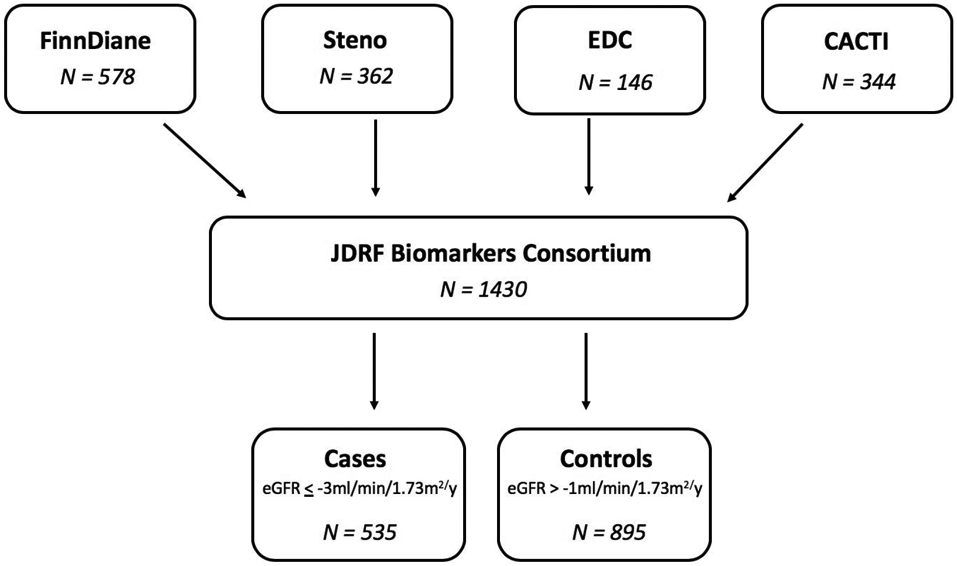

Our study sample is composed of 1,430 participants (535 cases and 895 controls) from four well-characterized T1D cohorts: the Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy study (FinnDiane), the Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen study (Steno), the Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications study (EDC) and the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes study (CACTI) (shown in Fig. 1) [20-23]. Subjects were included based on the following criteria: eGFR ≥ 30 ml/min/1.73m2 at baseline, follow up of at least 2 years, ≥ 3 longitudinal eGFR measurements, and baseline urine and blood sample availability. In FinnDiane, cases and controls were frequency-matched by albuminuria strata (normoalbuminuria, microalbuminuria, macroalbuminuria). In the three remaining cohorts, all participants who met the definition of case or control and met the stated criteria were included. To maintain consistency across cohorts given their extended durations, only participants examined between 1995 and 2011 were included.

Fig. 1.

Study design of JDRF Biomarkers Consortium, a case-control study nested in four T1D cohorts.

Details on protocols and data collection for each cohort have been previously published and are summarized in the Supplementary Text. Briefly, the FinnDiane cohort includes adults with T1D from healthcare centers across Finland who were evaluated regularly [20]. The Steno cohort includes adults with T1D who attended the Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen and were followed for a median of 4.7 years [21]. The EDC cohort includes subjects with childhood-onset T1D diagnosed or seen within one year of diagnosis at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh between 1950-1980 who were examined in 1986-88, then biennially for 10 years with additional examinations at 18 and 25 years [22]. The CACTI cohort includes adults with T1D without a history of cardiovascular disease at enrollment who were assessed at a baseline examination, then 3 and 6 years later [23].

Outcome

Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the CKD-EPI creatinine equation in all cohorts [24]. Laboratory methods for serum creatinine measurements differed by study cohort and are detailed in the Supplementary Text. Annual rate of eGFR decline was calculated by fitting regression lines to serial eGFR values (FinnDiane, Steno) or by dividing absolute eGFR change from baseline to last study visit by the number of years between these (EDC, CACTI).

Measurement of biological samples

Baseline timed urine and fasting plasma samples were obtained from each cohort. Coordinated shipping and storage efforts were undertaken to preserve biosample integrity and reduce the number of freeze-thaws. Frozen biosamples were stored in a central laboratory at University of California San Diego (UCSD), where they were entered into a sample-tracking database. Sample aliquots were transferred to platform sites for omics analysis and remain stored at −80°C.

Targeted metabolomic, lipidomic, and proteomic measurements and analyses are currently being performed concurrently at UT Health Science Center San Antonio/UCSD, University of Michigan, and University of Washington, respectively. Biomarkers measured in each platform are pre-specified based on existing scientific evidence of an association with DKD (Supplementary Table 1). Biomarkers are being quantified using targeted mass-spectrometry with inclusion of stable isotope-labeled standards to enhance accuracy and reduce variation across measurements. Strict quality control methods are employed to monitor instrument accuracy and batch-to-batch variation. The same techniques are being used to measure biomarkers in discovery and validation sets. Biomarkers that differ significantly between cases and controls will be considered for more precise quantification using orthogonal high throughput, quantitative assays.

Metabolomics

Previously, 13 out of 94 urine metabolites were found to differ between DKD and diabetes alone in a cross-sectional study of 108 participants [25]. These 13 metabolites, along with select organic acids, amino acids, purines, and pyrimidines identified by collaborators as being associated with DKD, are being measured in baseline urine and plasma samples using targeted gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and tandem liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) techniques [26,27].

Lipidomics

Earlier works identified plasma lipid alterations associated with CKD and T2 DKD progression [28-30]. A targeted LC-MS/MS assay was developed to quantify free fatty acids, acylcarnitines, and other members of complex lipid classes hypothesized to have an association with rapid eGFR decline in T1D. This targeted platform is being applied to baseline plasma samples.

Proteomics

Urine proteins were selected for measurement following a comprehensive literature review which identified 179 candidate proteins from 12 signaling pathways involved in DKD across animal and human studies. Thirty-eight tryptic peptides derived from 20 of these proteins could be reliably measured using protein precipitation and proteolysis-LC-MS/MS with adequate sensitivity and specificity. These peptides are being quantified using LC-MS/MS in baseline urine samples.

Statistical analyses

Clinical variable association and prediction studies

We developed and evaluated models of eGFR decline using clinical covariates to understand these associations and provide a foundation for biomarker analyses.

We first summarized the distribution and central tendencies of clinical variables, then fit clinical covariate data in logistic regression models to test associations of clinical variables with case versus control status. We developed three nested models: Model 1 included demographics (age at entry and sex); Model 2 included demographics, diabetes duration, and baseline HbA1c levels, urine albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR), and mean arterial pressure (MAP, defined as [(systolic blood pressure + (2 × diastolic blood pressure))/3]); Model 3 added baseline eGFR level to Model 2. Odds ratios with 95% CIs were calculated for each variable.

Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC) values were calculated to evaluate model discrimination, and DeLong’s test was used to compare nested model AUCs [31]. To accurately estimate model performance in future samples, we used repeated random sub-sampling validation, training models on a random 4/5th of the sample then testing these on the held-out 1/5th AUCs were calculated on the 1/5th sample. This training-testing process was repeated 500 times providing a distribution of test AUC estimates, from which a median and 95% CI were estimated.

Next, we compared model parameters according to four baseline eGFR strata: 30≤eGFR≤60 ml/min/1.73m2; 60<eGFR≤90 ml/min/1.73m2; 90<eGFR≤120 ml/min/1.73m2; and 120<eGFR≤150 ml/min/1.73m2. Interaction terms between this categorical eGFR variable and covariates were tested via likelihood ratio tests. If model fit improved significantly at 5% significance, separate models were fit for each stratum and cross-validated AUCs were calculated for stratified models. Finally, to test if the stratum-specific models improved discrimination, we used bootstrap resampling to compare AUCs of stratified and full models [32]. AUCs were calculated on each of 500 bootstrap samples. The difference between the full sample and stratum-specific AUCs were recorded. The 500 bootstrapped differences were used to calculate percentile intervals and test if stratum-specific AUCs differed from the full sample AUC. If the interval excluded zero, we inferred that the AUCs were statistically different. This analysis was repeated for baseline albuminuria strata defined by normoalbuminuria (UACR <30mg/g), microalbuminuria (30≤UACR<300 mg/g), and macroalbuminuria (UACR ≥300mg/g). When sample size was sufficient, we examined combined albuminuria and eGFR subgroups.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Our sample comprised 1430 subjects from the four T1D cohorts, including 535 cases and 895 controls (Table 1). Subjects’ mean age was 43 years, 50% were female, and mean (SD) diabetes duration was 26.8 (12.6) years. The mean (SD) HbA1c and eGFR were 8.5 (1.3)% and 94 (24) ml/min/1.73m2, respectively, and median UACR (25th, 75th %ile) was 12 (5, 64) mg/g. Subjects were followed for a median (25th, 75th %ile) of 7.6 (4.9, 11.7) years.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of participants in the JDRF Biomarkers Consortium by cohort and case-control status

| Overall n = 1430 |

By cohort | By case-control status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FinnDiane n = 578 |

Steno n = 362 |

EDC n = 146 |

CACTI n = 344 |

Case* n = 535 |

Control** n = 895 |

||

| Cases | 535 (37) | 299 (52) | 53 (15) | 66 (45) | 117 (34) | - | - |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Female sex | 721 (50) | 300 (52) | 154 (43) | 75 (51) | 192 (56) | 277 (52) | 444 (50) |

| Age (years) | 42.8 (12.7) | 41.3 (12.4) | 52.8 (12.0) | 37.3 (7.9) | 37.2 (9.1) | 39.6 (12.6) | 44.7 (12.4) |

| Race & ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 1400 (98) | 578 (100) | 362 (100) | 140 (96) | 320 (93) | 518 (97) | 882 (99) |

| Black | 11 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (4) | 5 (1) | 6 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Hispanic | 10 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (3) | 8 (1) | 2 (0) |

| Smoking history | |||||||

| Never | 579 (40) | 266 (46) | 0 (0) | 91 (62) | 222 (65) | 245 (46) | 334 (37) |

| Past | 238 (17) | 131 (23) | 0 (0) | 33 (23) | 74 (22) | 103 (19) | 135 (15) |

| Current | 213 (15) | 153 (26) | 0 (0) | 16 (11) | 44 (13) | 114 (21) | 99 (11) |

| Medical history and clinical characteristics | |||||||

| Diabetes duration (years) | 26.8 (12.6) | 25.6 (12.3) | 30.9 (16.0) | 29.3 (7.6) | 23.5 (9.0) | 25.8 (12.2) | 27.4 (12.8) |

| Retinopathy status | |||||||

| Present | 658 (46) | 263 (46) | 228 (63) | 71 (49) | 96 (28) | 235 (44) | 423 (47) |

| Not present | 709 (50) | 309 (53) | 77 (21) | 75 (51) | 248 (72) | 278 (52) | 431 (48) |

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mmHg) | 94.6 (11.3) | 98.6 (11.1) | 96.4 (10.2) | 85.3 (9.4) | 90.2 (9.5) | 95.8 (11.7) | 94.0 (11.0) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 129.9 (19.5) | 137.0 (18.7) | 136.5 (17.0) | 116.3 (14.9) | 116.8 (14.5) | 131.3 (20.6) | 129.1 (18.7) |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 77.0 (10.2) | 79.3 (10.2) | 76.4 (10.4) | 69.8 (9.7) | 76.8 (8.8) | 78.0 (10.6) | 76.4 (10.0) |

| ACEi or ARB use | |||||||

| Yes | 440 (31) | 290 (50) | 230 (64) | 33 (23) | 117 (34) | 246 (46) | 424 (47) |

| No | 624 (44) | 284 (49) | 132 (36) | 113 (77) | 227 (66) | 286 (53) | 470 (53) |

| Hypertension diagnosis | |||||||

| Yes | 643 (45) | 395 (68) | 74 (20) | 25 (17) | 149 (43) | 283 (53) | 360 (40) |

| No | 725 (51) | 179 (31) | 231 (64) | 121 (83) | 194 (56) | 230 (43) | 495 (55) |

| Laboratory data at baseline | |||||||

| HbA1c (%) | 8.5 (1.3) | 8.7 (1.6) | 8.7 (0.7) | 8.4 (1.4) | 8.1 (1.3) | 8.7 (1.6) | 8.3 (1.1) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 94 (24) | 94 (25) | 87 (15) | 102 (17) | 97 (30) | 100 (27) | 90 (21) |

| UACR (mg/g), median (IQR) | 12 (5.2-63.5) | 23.4 (6.4-123.5) | 13.0 (6.0-41.0) | 13.6 (6.8-47.8) | 6.3 (4.2-16.6) | 20.8 (6.4-196.6) | 9.3 (5.03-5.3) |

| UACR group (mg/g) | |||||||

| Macro: ≥ 300 mg/g | 143 (10) | 80 (14) | 24 (7) | 13 (9) | 26 (8) | 99 (19) | 44 (5) |

| Micro: >30, < 300 mg/g | 323 (23) | 159 (28) | 91 (25) | 34 (23) | 39 (11) | 134 (25) | 189 (21) |

| Normal ≤ 30 mg/g | 881 (62) | 286 (49) | 246 (68) | 99 (68) | 250 (73) | 269 (50) | 612 (68) |

| eGFR slope (ml/min/1.73m2/y) | −1.8 (4.4) | −3.0 (4.0) | −0.2 (5.0) | −2.5 (2.7) | −1.1 (4.2) | −5.7 (4.5) | 0.6 (1.9) |

Case: eGFR slope/yr ≤ −3 ml/min/1.73m2

Control: eGFR slope/yr > −1 ml/min/1.73m2

Entries are mean (SD) for continuous variables and N (%) for categorical variables, unless otherwise indicated. Percentages are calculated as percent of total values.

Number (%) of missing values for each variable in the overall study population: race & ethnicity 9 (1), smoking history 400 (28), diabetes duration 1 (<1), retinopathy status 63 (4), MAP 7 (<1), SBP 7 (<1), DBP 7 (<1), antihypertensive medication 4 (<1), hypertension diagnosis 62 (4), HbA1c 8 (1), baseline UACR 83 (6).

JDRF = Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation; CACTI = Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 diabetes study; EDC = Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications study; FinnDiane = Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy Study; Steno = Steno Diabetes Center Study; ACEi = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker

Compared with control participants, cases were on average younger, had higher average baseline levels of HbA1c, blood pressure, eGFR, and UACR compared to controls (Table 1). The mean (SD) annual eGFR slope was −5.65 (4.53) ml/min/1.73m2 in cases, versus 0.57 (1.87) ml/min/1.73m2in controls.

Characteristics associated with eGFR decline

Younger age at study entry was associated with greater risk of rapid eGFR decline in the demographics-only model (Model 1), which had an AUC of 0.61 (Table 2). In Model 2, younger age, higher HbA1c, and higher UACR were associated with rapid eGFR decline. Compared to the demographics-only model, Model 2 had a significantly higher AUC of 0.69 (p = 0.0015). In the fully-adjusted model (Model 3) comprising demographic and clinical variables, younger age, longer diabetes duration, and higher HbA1c, UACR, and eGFR conferred greater risk of rapid eGFR decline. Specifically, every 10 more years of age was associated with a 24% lower odds of rapid eGFR decline, every 10 more years of diabetes duration was associated with a 20% higher odds of rapid eGFR decline, each 1% higher HbA1c was associated with a 15% higher odds of rapid eGFR decline, each two-fold greater UACR was associated with a 30% higher odds of rapid eGFR decline, and every 10 ml/min/1.73m2 greater baseline eGFR was associated with a 31% higher odds of rapid eGFR decline. Compared to the demographics-only model, Model 3 had a significantly higher AUC of 0.74 (p < 0.001).

Table 2:

Associations of clinical characteristics with rapid eGFR decline among participants from the JDRF Biomarkers Consortium

| Model 1 OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 OR (95% CI) |

Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.72 (0.66, 0.79)* | 0.63 (0.56, 0.72)* | 0.76 (0.66, 0.87)* |

| Sex (ref: female) | 0.99 (0.80, 1.24) | 0.89 (0.70, 1.13) | 0.82 (0.64, 1.05) |

| Diabetes duration (per 10 years) | 1.13 (0.99, 1.29) | 1.20 (1.05, 1.37)* | |

| HbA1c (per 1%) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.29)* | 1.15 (1.05, 1.27)* | |

| Mean Arterial Pressure (per 10 mmHg) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.21) | 1.11 (0.99, 1.25) | |

| UACR (per doubling) | 1.19 (1.13, 1.25)* | 1.30 (1.23, 1.38)* | |

| eGFR (per 10 ml/min/1.73m2) | 1.31 (1.23, 1.41)* | ||

| AUC median (95% CI) | 0.61 (0.56, 0.67) | 0.69 (0.63, 0.75) | 0.74 (0.68, 0.79) |

Full Cohort: N = 1430; N (cases) = 535. Cell contents are odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI from logistic regression models, as well as cross-validated area under the curve (AUC; median 95% CI).

p < 0.05

Consideration of additional risk factors

When added to Model 3, the presence of hypertension (as a binary indicator) was significantly associated with rapid eGFR decline (OR 1.46; 95% CI 1.09, 1.96). Neither angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) use, presence of retinopathy, nor smoking history (past, current, never smoker) were significantly associated with rapid eGFR decline. When added to Model 3, neither the presence of hypertension, ACEi or ARB use, the presence of retinopathy, nor smoking history improved model discrimination. Thus, we conducted all subsequent subgroup analyses based on Model 3 to minimize the impact of missing information (Supplementary Table 2).

Subgroup analysis

Addition of interactions between baseline eGFR or UACR strata and clinical variables improved the fit of the logistic model significantly (likelihood ratio p-value < 0.001). Hence, we applied Model 3 to eGFR, UACR, and combined eGFR and UACR strata with sufficient sample-sizes (Supplementary Table 2). The directions of association for the predictors with rapid eGFR decline in the stratified models were similar to those in the full cohort models. Notably, the magnitude of the association of UACR with rapid eGFR decline was greater in the eGFR 60-90ml/min/1.73m2 group (OR 1.39; 95% CI 1.27, 1.53) compared to groups with higher eGFRs (OR 1.10-1.24). Additionally, while higher HbA1c was significantly associated with rapid eGFR decline in groups with microalbuminuria (OR 1.36; 95% CI 1.14, 1.65) and macroalbuminuria (OR 1.66; 1.24, 2.29), this association was not observed in the normoalbuminuria group.

Figure 2 depicts the median (95% CIs) cross-validated AUCs. There was substantial variability in discrimination across baseline kidney function categories compared to the full cohort AUC, with cross-validated AUCs ranging from 0.59 to 0.76. The lowest AUCs were observed in the eGFR 120-150 ml/min/1.73m2 group (AUC 0.59), the macroalbuminuria group (AUC 0.65), and the combined normoalbuminuria and eGFR 90-120 ml/min/1.73m2 group (AUC 0.65).

Fig. 2.

Performance of demographic and clinical variables in the prediction of rapid eGFR loss according to baseline eGFR and urine albumin-creatinine ratio. Presented values are cross-validated area under the curve (AUC; median 95% CI).

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

We have assembled a collection of well-defined T1D cohorts to identify biomarkers associated with rapid eGFR decline. While demographic and clinical variables were significantly associated with rapid eGFR decline in these cohorts, these do not predict rapid eGFR decline with sufficient precision. Our expectation is that omics-derived urine and plasma biomarkers will be associated with rapid eGFR decline, independent of demography and clinical variables, and enhance the predictive ability of our models.

Our use of four large, multi-national, rigorously-derived T1D cohorts leaves us well-positioned to identify biomarkers associated with rapid eGFR decline. These T1D cohorts have large sample sizes, prolonged follow-up, and excellent participant retention. Additionally, each cohort has used standardized methods for participant recruitment, data collection, and biosample preservation. Furthermore, availability of timed urine and fasting plasma samples in all cohorts increases the precision of biomarker measurements and facilitates comparisons across cohorts. The clinical models developed here will be used as the base for discovery and validation omics analyses. Biomarkers associated with rapid eGFR decline will be incorporated into predictive models made using clinical variables and AUC values for these will be calculated to assess model discrimination.

We found that younger age, longer diabetes duration, and higher baseline HbA1c, UACR, and eGFR were associated with rapid eGFR decline in our study population. Overall, these findings are consistent those observed in other T1D and T2D populations [33-36]. Notably, a two-fold higher UACR was associated with 30% greater odds of rapid eGFR decline in our fully-adjusted model. However, this association is difficult to interpret and may be biased towards the null because of matching of case-control status by albuminuria strata in one of our study cohorts. To build a foundation for assessing the predictive ability of measured biomarkers, we derived prognostic models using these clinical variables. We found that overall model discrimination was moderate (AUC = 0.74) using age, sex, diabetes duration, HbA1c, blood pressure, albuminuria, and baseline eGFR as predictors of rapid eGFR decline. Similarly-derived models focusing on incident DKD or major kidney-related events as outcomes have had greater predictive success [14, 37].

The relatively low discriminatory potential of our model could be explained by our focus on an outcome which occurs early in the course of DKD as well as by the high average baseline eGFR in our cohort [33]. Interaction testing confirmed that associations between covariates and rapid eGFR decline differed according to baseline kidney function. Subgroup analyses revealed that model discrimination varied by strata of baseline eGFR and albuminuria. Specifically, the model demonstrated poor predictive ability among those with baseline eGFR 120-150ml/min/1.73m2 (AUC = 0.59), baseline macroalbuminuria (AUC = 0.65), and baseline eGFR 90-120ml/min/1.73m2 and normoalbuminuria (AUC = 0.65). The difficulty in predicting eGFR decline in these subgroups may reflect variable biologic underpinnings of eGFR decline, though regression to the mean may also contribute to these findings. Overall, weak-to-moderate AUCs, especially when eGFR and albuminuria are in the normal range, highlight the need for prognostic biomarkers capable of early identification of high-risk individuals.

Using novel, targeted omics strategies, we plan to identify plasma and urine biomarkers associated with rapid eGFR decline which elucidate mechanisms of T1 DKD and build on clinical predictive models. Numerous biomarkers belonging to pathways implicated in DKD, including inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and fibrosis, have been associated with DKD-related outcomes in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [11]. At the same time, questions remain regarding the specific molecules comprising these pathogenic pathways and how they contribute to eGFR decline in DKD. This is partly because of heterogeneity across existing studies in clinical outcomes, chosen biomarkers, and methods of biomarker quantification, which has made biomarker validation challenging [11].

There has been increasing interest in the association of biomarkers with eGFR decline in DKD [38, 39]. Our panel of 13 urine metabolites was recently found to correlate with eGFR slope in 1,001 subjects with T2D in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort study [40]. Notably, this panel was responsive to therapy with dapagliflozin and atrasentan, suggesting potential as a surrogate indicator for mitochondrial dysfunction in T2D [41,42]. Members of our group have also identified 125 plasma metabolites associated with eGFR in a meta-analysis including 3,089 samples from participants of five independent Dutch T2D cohort studies [19]. Similar biomarker advances have also been made in T1D, albeit in relatively smaller study populations. Serum lipidomic measurements of 669 individuals with T1D from Steno identified cross-sectional associations between phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin species and eGFR and albuminuria, out of which 13 lipids were longitudinally associated with eGFR or albuminuria slope [15]. Serum metabolomic measurements in this cohort additionally revealed ribonic acid and myo-inositol to be inversely associated with ≥30% eGFR decline [16] Also, in a study of 465 individuals with T1D from CACTI, a panel of 4 out of 252 urine peptides identified in a label-free discovery analysis improved prediction of annual eGFR decline ≥ 3.3% and/or development of albuminuria when added to DKD risk factors (increase in AUC from 0.84 to 0.89) [43].

These promising results underscore the need to further study eGFR decline in T1D using large cohorts and refined, combined multi-omic assays. In our study we propose to use these strategies to develop a robust set of biomarkers which are specific to this population, internally and externally validated, and have multi-national applicability. Additionally, our use of a hypothesis-driven, targeted omics approach that will yield highly precise, quantitative, and reproducible results is conducive to our goals of deciphering mechanisms of eGFR decline and improving prediction of this outcome.

Our work may serve as a foundation on which future omics research can build. Added insight into pathological pathways may encourage generation of new diagnostic tests and therapies. Following extensive validation and assay optimization, identified biomarkers may be able to act as surrogates for risk of eGFR decline in T1D. This could facilitate recruitment and increase efficiency in clinical trials, as those at increased risk for poor outcomes are more likely to benefit from therapeutic interventions. Ultimately, we hope to integrate metabolomic, lipidomic, and proteomic biomarker data with kidney tissue-derived genetic and transcriptional network data using systems biology and computational bioinformatic techniques with the goal of mechanistically defining pathologic DKD subgroups. By then associating molecularly defined subgroups with clinical characteristics and kidney outcomes, we aim to develop a functional framework for rapid eGFR decline in T1D.

Our study has several limitations. Our population is primarily white, limiting applicability of results to wider ranges of races and ethnicities. We defined case-control status using a linear estimation of eGFR decline, though eGFR trajectories may exhibit non-linear patterns. However, existing evidence suggests that non-linear eGFR decline occurs only in a minority [33]. A substantial proportion of our study population has a baseline eGFR >90 ml/min/1.73m2, a range in which changes in eGFR are difficult to ascertain. The observation that cases had higher baseline eGFR than controls is likely due to participant selection, as subjects with higher baseline eGFR have more capacity to reach the threshold for case definition. In this group, a “therapeutic” decline in eGFR resulting from reduced “hyperfiltration” is difficult to distinguish from a “pathologic” one. We have defined rapid versus slow decline based on extremes of the eGFR slope distribution and have determined slopes over prolonged follow-up periods, which should reduce misclassification. At the same time, since models were developed using extremes of the eGFR slope distribution, the discriminatory ability of these models would be attenuated by application to a broader cohort with a wide range of eGFR slopes. Also, as mentioned above, the association of UACR with rapid eGFR decline should be interpreted with caution due to matching of case-control status by albuminuria strata in one of our study cohorts. With respect to our biomarker analyses, prolonged storage and inconsistencies in biosample collections across cohorts could influence the accuracy and sensitivity of measurements. Additionally, though biomarkers present in small quantities may be difficult to detect, our targeted approach represents the optimal strategy for increasing measurement precision.

In conclusion, we have assembled a large, multinational T1D cohort for determining metabolic, lipid, and protein biomarkers associated with rapid eGFR decline. In this cohort, clinical factors alone are insufficient in predicting rapid eGFR decline, especially among those with normal baseline kidney function. Our application of novel, targeted omics approaches may help improve understanding of the mechanisms underlying rapid eGFR decline and may facilitate identification of those at risk for this outcome.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Text. Description of the four study cohorts

Supplementary Table 1. Biomarkers measured using targeted omics assays in the JDRF Biomarkers Consortium

Supplementary Table 2. Associations of clinical characteristics with rapid eGFR decline stratified by baseline eGFR and UACR in the JDRF Biomarkers Consortium

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The skilled technical assistance of Maikki Parkkonen, Mira Korolainen, Anna-Reetta Salonen, Anna Sandelin, and Jaana Tuomikangas is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also acknowledge all the physicians and nurses at each center participating in the collection of patients.

FUNDING SOURCES

JDRF Network grant 3-SRA-2016-104 (PI:KS) provided major support for this study. The FinnDiane study was funded by the Folkhälsan Research Foundation, the Wilhelm and Else Stockmann Foundation, the Liv och Hälsa Society, the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF OC0013659), the Helsinki University Hospital Research Funds, and the Academy of Finland (299200, 275614, 316664). The EDC study was funded by NIH grant DK34818 and the Rossi Memorial Fund. The CACTI study was funded by NIH grants R01HL113029, R01HL079611, RC1DK086958, and R01DE026480. CL was funded by NIDDK grants T32DK007467 and R01DK088762, and Northwest Kidney Centers. LN was partially supported by NIDDK grant 1R01DK110541-01A1. FA was funded by NIDDK grants K08-DK106523 and R03-DK121941. SP was funded by NIDDK grants R24DK082841 and P30DK081943, and JDRF Center for Excellence (5-COE-2019-861-S-B)

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF ETHICS

Research protocols for FinnDiane, Steno, EDC, and CACTI were approved by each center’s respective ethics committee or institutional review board. All participants provided informed consent.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

CPL, LN, JZ, EV, FA, TC, JSB, RGM, MD, NS, CF, TO, SP nothing to disclose. IHdB has obtained research funding from the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA), received equipment and supplies for research from MedTronic and Abbott, and consults for Boehringer-Ingelheim and Ironwood. P-HG has received investigator research grants from Eli Lilly and Roche, and lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Elo Water, Genzyme, Medscape, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. P-HG is an advisor for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cebix, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medscape, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. PR has received consultancy and/or speaking fees (to his institution) from AbbVie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Novo Nordisk, Vifor, and Sanofi Aventis, and research grants from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk. KS is on the Advisory Board for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen and has received research support from Merck and Boerhinger Ingelheim. TSA has a research grant from Novo Nordisk and holds shares in Zealand Pharma A/S and Novo Nordisk A/S.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Boer IH. Kidney Disease and Related Findings in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):24–30. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for diabetes and CKD: 2012 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(5):850–886. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costacou T, Orchard TJ. Cumulative kidney complication risk by 50 years of type 1 diabetes: The effects of sex, age, and calendar year at onset. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(3):426–433. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakris GL, Molitch M. Are all patients with type 1 diabetes destined for dialysis if they live long enough? Probably not. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(3):389–390. doi: 10.2337/dci17-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krolewski AS, Niewczas MA, Skupien J, et al. Early progressive renal decline precedes the onset of microalbuminuria and its progression to macroalbuminuria. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):226–234. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krolewski AS, Skupien J, Rossing P, Warram JH. Fast renal decline to end-stage renal disease: an unrecognized feature of nephropathy in diabetes. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1300–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Ostrander BE, et al. Microalbuminuria and the risk for early progressive renal function decline in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(4):1353–1361. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma K, Susztak K, Pennathur S. Introduction: Systems Biology of Kidney Disease. Semin Nephrol. 2018;38(2):99–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas MC, Brownlee M, Susztak K, et al. Diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2015;1(July):1–20. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahluwalia TS, Kilpeläinen TO, Singh S, Rossing P. Editorial: Novel biomarkers for type 2 diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10(September):1–3. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colhoun HM, Marcovecchio ML. Biomarkers of diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia. 2018;61(5):996–1011. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gohda T, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, et al. Circulating TNF Receptors 1 and 2 Predict Stage 3 CKD in Type 1 Diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(3):516–524. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsblom C, Moran J, Haijutsalo V, et al. Added value of soluble tumor necrosis factor-α receptor 1 as a biomarker of ESRD risk in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2334–2342. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjornstad P, Pyle L, Cherney DZI, et al. Plasma biomarkers improve prediction of diabetic kidney disease in adults with type 1 diabetes over a 12-year follow-up: CACTI study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(7):1189–1196. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tofte N, Suvitaival T, Ahonen L, et al. Lipidomic analysis reveals sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine species associated with renal impairment and all-cause mortality in type 1 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52916-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tofte N, Suvitaival T, Trost K, et al. Metabolomic assessment reveals alteration in polyols and branched chain amino acids associated with present and future renal impairment in a discovery cohort of 637 persons with type 1 diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10(November):1–11. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cañadas-Garre M, Anderson K, McGoldrick J, Maxwell AP, McKnight AJ. Proteomic and metabolomic approaches in the search for biomarkers in chronic kidney disease. J Proteomics. 2018;(July). doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tofte N, Lindhardt M, Adamova K, et al. Early detection of diabetic kidney disease by urinary proteomics and subsequent intervention with spironolactone to delay progression (PRIORITY): a prospective observational study and embedded randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8587(20):1–12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tofte N, Vogelzangs N, Mook-Kanamori D, et al. Plasma metabolomics identifies markers of impaired renal function: A meta-analysis of 3,089 persons with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020:1–30. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy003/4791932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorn LM, Forsblom C, Fagerudd J, et al. Metabolic syndrome in type 1 diabetes: Association with diabetic nephropathy and glycemic control (the FinnDiane study). Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):2019–2024. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferreira I, Hovind P, Schalkwijk CG, Parving HH, Stehouwer CDA, Rossing P. Biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction as predictors of pulse pressure and incident hypertension in type 1 diabetes: a 20 year life-course study in an inception cohort. Diabetologia. 2018;61(1):231–241. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4470-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orchard TJ, Dorman JS, Maser RE, et al. Prevalence of Complications in IDDM by Sex and Duration: Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study II. Diabetes. 1990;39(9):1116 LP–1124. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.9.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dabelea D, Kinney G, Snell-Bergeon JK, et al. Effect of type 1 diabetes on the gender difference in coronary artery calcification: a role for insulin resistance? The Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study. Diabetes. 2003;52(11):2833–2839. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.4172/2161-0959.1000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma K, Karl B, Mathew AV., et al. Metabolomics reveals signature of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(11):1901–1912. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niewczas MA, Sirich TL, Mathew A V, et al. Uremic solutes and risk of end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes: Metabolomic study. Kidney Int. 2014;85(5):1214–1224. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pena MJ, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Hellemons ME, et al. Urine and plasma metabolites predict the development of diabetic nephropathy in individuals with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2014;31(9):1138–1147. doi: 10.1111/dme.12447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Afshinnia F, Rajendiran TM, Soni T, et al. Impaired B-oxidation and altered complex lipid fatty acid partitioning with advancing CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(1):295–306. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017030350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afshinnia F, Rajendiran TM, Karnovsky A, et al. Lipidomic signature of progression of chronic kidney Disease in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort. Kidney Int Reports. 2016;1(4):256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Afshinnia F, Nair V, Lin J, et al. Increased lipogenesis and impaired B-oxidation predict type 2 diabetic kidney disease progression in American Indians. JCI Insight. 2019;4(21). doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.130317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delong ER, DeLong DM, CLarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Efron B, Tibshirani R. Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Stat Sci. 1986; 1(1):54–77. doi: 10.2307/2246134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skupien J, Warram JH, Smiles AM, et al. The early decline in renal function in patients with type 1 diabetes and proteinuria predicts the risk of end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2012;82(5):589–597. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrésdóttir G, Jensen ML, Carstensen B, et al. Improved prognosis of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015;87(2):417–426. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang W, Wang J, Shen X, et al. Establishment and validation of a risk prediction model for early diabetic kidney disease based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 cohorts. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(4):925 LP–933. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radcliffe NJ, Seah JM, Clarke M, MacIsaac RJ, Jerums G, Ekinci EI. Clinical predictive factors in diabetic kidney disease progression. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8(1):6–18. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elley CR, Robinson T, Moyes SA, et al. Derivation and validation of a renal risk score for people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3113–3120. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morita M, Uchigata Y, Hanai K, Ogawa Y, Iwamoto Y. Association of urinary type IV collagen with GFR decline in young patients with type 1 diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(6):915–920. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer G, Heerspink HJL, Aschauer C, et al. Systems biology-derived biomarkers to predict progression of renal function decline in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(3):391–397. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwan B, Fuhrer T, Zhang J, et al. Metabolomic markers of kidney function decline in patients with diabetes: evidence from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. May 2020. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulder S, Heerspink HJL, Darshi M, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on urinary metabolites in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, Obes Metab. 2019;21(11):2422–2428. doi: 10.1111/dom.13823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pena MJ, de Zeeuw D, Andress D, et al. The effects of atrasentan on urinary metabolites in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Diabetes, Obes Metab. 2017;19(5):749–753. doi: 10.1111/dom.12864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlatzer D, Maahs DM, Chance MR, et al. Novel urinary protein biomarkers predicting the development of microalbuminuria and renal function decline in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):549–555. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text. Description of the four study cohorts

Supplementary Table 1. Biomarkers measured using targeted omics assays in the JDRF Biomarkers Consortium

Supplementary Table 2. Associations of clinical characteristics with rapid eGFR decline stratified by baseline eGFR and UACR in the JDRF Biomarkers Consortium