Abstract

Introduction:

Although CRT is the standard of care for patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC (LA-NSCLC), most patients relapse. Tecemotide is a MUC1 antigen-specific cancer immunotherapy vaccine. Bevacizumab improves survival in advanced NS-NSCLC and has a role in immune modulation. This phase II trial tested the combination of tecemotide and bevacizumab following CRT in patients with LA-NSCLC.

Methods:

Subjects with stage III NS-NSCLC suitable for CRT received carboplatin/paclitaxel weekly + 66 Gy followed by 2 cycles of consolidation carboplatin/paclitaxel ≤ 4 weeks of completion of CRT (Step 1). Patients with PR/SD after consolidation therapy were registered onto Step 2, which was six weekly tecemotide injections followed by q6 weekly injections and bevacizumab q3 weeks for up to 34 doses. The primary endpoint was to determine the safety of this regimen.

Results:

70 patients were enrolled, 68 patients (median age 63, 56% male, 57% stage IIIA) initiated therapy, but only 39 patients completed CRT and consolidation therapy per protocol, primarily due to disease progression or toxicity. 33 patients (median age 61, 58% male, 61% stage IIIA) were registered to Step 2 (tecemotide + bevacizumab). The median number of step 2 cycles received was 11 (range 2–25). Step 2 worst toxicity: gr 3 N=9, gr 4 N=1, gr 5 N=1. Grade 5 toxicity in step 2 was esophageal perforation attributed to bevacizumab. Among the treated and eligible patients (n=32) who were treated on Step 2, median OS was 42.7 months (95% CI 21.7–63.3) and median PFS was 14.9 months (95% CI 11.0–20.9) from Step 1 registration.

Conclusions:

This cooperative group trial met its endpoint, demonstrating tolerability of bevacizumab + tecemotide after CRT and consolidation. In this selected group of patients, the median PFS and OS are encouraging. Given that consolidation immunotherapy is now a standard of care following CRT in patients with LA-NSCLC, these results support a role for continued investigation of antiangiogenic and immunotherapy combinations in LA-NSCLC.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Non-small cell lung cancer accounts for 80–85% of cases, and 30% of patients present with stage III disease. Multiple phase III trials have resulted in adoption of concurrent chemoradiotherapy as the standard of care for unresectable or inoperable stage IIIA and IIIB non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with good performance status.(1) Chemoradiotherapy with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy concurrent with 60 Gy radiotherapy daily over six weeks with or without two additional cycles of consolidative chemotherapy(2) is superior to either modality alone or sequential delivery of chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy.(3–5) Despite multiple advances, concurrent chemoradiotherapy without additional therapies yields a median overall survival (OS) of only 20–28 months and 5-year OS rates of 15–20%.(6)

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibition has radically altered therapy and survival expectations for patients with NSCLC. The PACIFIC trial, a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating the immune checkpoint inhibitor, durvaluamab in patients with stage III unresectable NSCLC who did not have progression after concurrent chemoradiotherapy, demonstrated significantly longer progression free and overall survival than placebo (median OS NR vs. 28.7 months; HR 0.68 (p=0.0025) .(7) These practice-changing results support enthusiasm for further investigation of immunotherapy and combination therapies in this setting.

An alternative immunologic approach under investigation is therapeutic cancer vaccination. One such vaccine is tecemotide (L-BLP25, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), a mucin 1 (MUC1)-specific agent that induces T-cell responses to MUC1.(8,9) MUC1 is overexpressed and abnormally glycosylated in NSCLC,(10,11) which leads to inappropriate activation of signaling pathways and the subsequent growth, proliferation, and survival of cancer cells.(12) Although the trial did not meet its primary endpoint in the overall population, the phase III START (Stimulating Targeted Antigenic Response To NSCLC) trial of tecemotide versus placebo as maintenance therapy in patients with stage III NSCLC who received chemoradiotherapy indicated potential OS improvement over placebo (30.8 versus 20.8 months) in the subgroup of patients who had received primary concurrent rather than sequential chemoradiotherapy.(13)

Because of the known improvements in response rate, progression-free survival and overall survival when bevacizumab is added to carboplatin/paclitaxel in advanced non-squamous NSCLC, there was significant interest to study this therapy in patients with earlier stages of disease.(14,15) Moreover, in addition to the known antiangiogenic effects of bevacizumab, the inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has multiple immunomodulatory effects(16–18) and could potentially improve the efficacy of immunotherapy.

The current study was conducted primarily to determine the safety of combination therapy of tecemotide plus bevacizumab after concurrent chemoradiation and consolidation chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced, non-squamous NSCLC. Salient secondary objectives were to evaluate the overall survival, toxicity, and progression-free survival for patients treated with tecemotide plus bevacizumab in addition to chemoradiation and consolidation chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the respective institutional review boards at all participating sites. Study participants provided a written informed consent before undergoing any study-related procedures. The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Patient Selection

Eligible patients were those aged 18 years or older with histologically confirmed stage III (AJCC V7), unresectable non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer, without pleural effusion, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–1. Stage was confirmed and documented by CT, MRI or PET. Pathologic confirmation of mediastinal lymph nodes was not required for lymph nodes > 2 cm. Patients with mediastinal lymph nodes that were > 1 cm but < 2 cm were required to have pathologic confirmation of disease to rule out resectability. Patients were excluded if they had prior chemotherapy or monoclonal antibodies for other cancer within 5 years or any prior chemotherapy for lung cancer, prior chest radiotherapy, history of gross hemoptysis, ongoing infection, pre-existing medical condition requiring chronic steroids or immunotherapy therapy, or significant organ dysfunction.

Treatment

The study was designed as a single-arm, phase II trial. Treatment consisted of 2 distinct phases of therapy.

After registration, patients started concomitant chemoradiation (step 1). All patients received paclitaxel 45 mg/m2 and carboplatin AUC 2 weekly for 6 weeks and definitive radiation therapy 6600 cGy at 2.0 Gy/fraction for 6.5 weeks to all areas of known macroscopic primary tumor and nodal metastases. Intervening nodal stations between the primary tumor and stations of known nodal involvement received 5000 cGy in 5 weeks. Radiation therapy started within a 72 hour window of the start of chemotherapy. Three-dimensional treatment planning was required, but the use of intensity-modulated radiation therapy was not allowed.

Within four weeks of completing concomitant chemoradiation, patients with complete response (CR), partial response (PR) or stable disease (SD) at disease evaluation after chemoradiation and with resolution of all radiation-related toxicities, received two cycles of consolidation chemotherapy (paclitaxel 225 mg/m2 and carboplatin AUC 6 q 21days) as completion of step 1 treatment. Patients with progressive disease, unresolved radiation-related toxicities, and unevaluable response were discontinued from treatment.

Patients underwent disease evaluation at the end of consolidation chemotherapy. Patients with progressive disease or unevaluable response discontinued protocol therapy. Patients had to meet all eligibility requirements from initial registration for protocol maintenance treatment on step 2. An amendment in October 2013 allowed patients with platelets ≥ 100,000/mm3 to remain on maintenance treatment if all other parameters were met. Maintenance therapy was a single dose of cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 three days prior to cycle 1, followed by bevacizumab 15 mg/kg on day 1 of every 21 day cycle and tecemotide immunotherapy 806 mcg subcutaneously on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycles 1 and 2, then day 1 of every other cycle (ie, cycles 4, 6, 8, etc). Cyclophosphamide was given to overcome immune suppression due to malignant disease that might have interfered with responses to tecemotide. After the initial 2 cycles, maintenance treatment consisted tecemotide injections q6 weekly s and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg q3 weeks for up to 34 doses, progression or toxicity.

Statistical considerations

The schema of this trial is shown in Figure 1. A two-stage design was employed to evaluate safety of the maintenance therapy (tecemotide plus bevacizumab in step 2) after concomitant chemoradiation and consolidation chemotherapy (step 1). A true toxicity rate of ≤ 5% in step 2 (for clearly attributable grade 4–5 hemorrhage, esophagitis, fistula, thrombocytopenia, encephalitis, infection, or hepatic failure) was considered worthy of further study, while a toxicity rate of 25% was considered to be excessive. Eighteen patients would be enrolled into step 1, anticipating that 10 patients would achieve a CR, PR, or SD at the end of step 1 and start maintenance therapy. The study would then be suspended for 18 weeks for toxicity evaluations. If < 2 clearly attributable target adverse events were observed during the maintenance therapy among the first 10 treated patients, an additional 37 patients were to be accrued into step 1 with the expectation that 20 patients would receive maintenance therapy. If ≥5 clearly attributable adverse events of interest were observed during the maintenance therapy among the total 30 treated patients, the new regimen would be considered unacceptable. This design had 8.6 % probability of stopping early and 9% probability of declaring the regimen unacceptable if the true toxicity rate of interest during the maintenance therapy was 5%, and 93% probability of declaring the regimen unacceptable if the true toxicity rate was 25%. Given the disease control rate at the end of step 1 was less than expected (38% vs. 60%), the accrual goal was increased from 55 to 88 patients in order to ensure a sufficient number of patients in the maintenance phase of this study.

Figure 1:

Study Schema

The primary safety analysis was performed on all patients who started protocol maintenance therapy. Toxicities were evaluated using NCI Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 4.0). Objective response was evaluated using the revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.1). Overall survival (OS), was defined as the time from registration to death from any cause. Patients who were alive or lost to follow-up at the time of this analysis were censored at date last known alive. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from registration to disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients who died >3 months after the last disease assessment that showed progression-free or who were alive and free of progression were censored at the date last known progression-free.

Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) were used to describe adverse events of interest, with the two-stage binomial confidence interterval of the target toxicity rate computed by the method of Atkinson and Brown(19). The same descriptive statistics were used to characterize patients at baseline, toxicity, and response. The Kaplan-Meier method(20) was used to estimate OS and PFS, with 95% confidence interval reported as well.

RESULTS

Accrual and Disposition of Patients

This study was activated on December 22, 2010, and enrolled 70 patients at 19 institutions before termination on October 13, 2014. The study was suspended per protocol on January 12, 2012, for interim toxicity analysis. At that point, only 8 patients had received maintenance treatment and no targeted adverse events were observed. The study was reactivated on October 9, 2012, to stage 2 accrual, under the condition that step 2 toxicity data of the two new patients being closely monitored. This trial continued thereafter as planned. Among the 70 enrolled patients, 2 never started protocol therapy and eligibility for 2 additional 2 cases could not be finalized. Thirty-three patients were further registered to step 2 (with 1 unfinalized eligibility status) and all started maintenance therapy.

Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

Details of demographics and disease characteristics of all 68 patients starting step 1 treatment are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics at Study Entry (Step 1, Treated Patients, N=68)

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 38 | 55.9 |

| Female | 30 | 44.1 |

| Race | ||

| White | 59 | 95.2 |

| Black | 3 | 4.8 |

| Unknown | 6 | - |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 | 4.6 |

| Non-Hispanic | 62 | 95.4 |

| Unknown | 3 | - |

| PS | ||

| 0 | 38 | 55.9 |

| 1 | 30 | 44.1 |

| Weight Loss in Previous 6 Months | ||

| <5% | 58 | 86.5 |

| 5 - <10% | 4 | 6.0 |

| 10 - <20% | 5 | 7.5 |

| Unknown | 1 | - |

| Histology Type | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 62 | 91.2 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 3 | 4.4 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer, NOS | 3 | 4.4 |

| Disease Stage at Entry | ||

| IIIA | 39 | 57.4 |

| IIIB | 29 | 42.6 |

| Pleural Effusion | ||

| No | 63 | 92.6 |

| Yes, clinical assessment only | 4 | 5.9 |

| Yes, but cytologically negative | 1 | 1.5 |

| Smoking History | ||

| Current smoker (quit less than 1 year ago) | 33 | 48.5 |

| Former smoker (quit at least 1 year ago) | 28 | 41.2 |

| Never smoker (<100 cigarettes in lifetime) | 7 | 10.3 |

| Metastatic Site(s) | ||

| No | 5 | 7.4 |

| Yes | 63 | 92.6 |

| Hilar Nodes | 32 | 47.1 |

| Mediastinal Nodes | 47 | 69.1 |

| Supraclavicular/Scalene Nodes | 13 | 19.1 |

| Ipsilateral Lung | 3 | 4.4 |

| Pleura | 2 | 2.9 |

| Other | 16 | 23.5 |

| Age (Median (Minimum, Maximum)) | 62.5 (36, 83) | |

Treatment Delivery

Of the 68 patients who started step 1 treatment (chemoradiation and consolidation chemotherapy), 39 completed step 1 treatment (57%). The most common reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression (16%), followed by toxicity complication (15%). Thirty-three patients began step 2 treatment (bevacizumab and tecemotide) with median number of 11 cycles (range 2–25, excluding 1 patient with incomplete treatment information). The main reason for maintenance treatment discontinuation were treatment-emergent toxicities (41%), followed by disease progression (34%)

Toxicity

Table 2 and Table 3 summarize toxicity incidence of grade 3 and higher (possibly, probably, or definitely related to protocol treatment) in step 1 and step 2, respectively. Among the 68 patients treated on step 1 of therapy, 27 had grade 3 toxicities with the most common adverse events as leucopenia (N=10), lymphopenia (N=7), neutropenia (N=6) and fatigue (N=6). Eleven patients had grade 4 toxicities, and one lethal adverse event due to sepsis occurred. Of the 33 patients who received protocol treatment on step 2, there was one grade 5 death, (not otherwise specified (NOS)), one patient with grade 4 sepsis, and transaminitis) and 9 patients had grade 3 toxicities, including 6 with grade 3 hypertension.

Table 2:

Treatment-related Toxicities for All Treated Patients (Step 1, Reported by CRFs)

| Treatment Arm A (n=68) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Type | Grade | ||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| (n) | (n) | (n) | |

| Anemia | 2 | 1 | - |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 | 2 | - |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 | - | - |

| Fatigue | 6 | - | - |

| Diarrhea | 1 | - | - |

| Esophageal pain | 1 | - | - |

| Esophagitis | 3 | - | - |

| Mucositis oral | 1 | - | - |

| Vomiting | 3 | - | - |

| Anaphylaxis | 1 | - | - |

| Bronchial infection | 1 | - | - |

| Device related infection | 1 | - | - |

| Lung infection | 2 | - | - |

| Meningitis | 1 | - | - |

| Mucosal infection | 1 | - | - |

| Sepsis | - | 2 | 1 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | - | - |

| Dermatitis radiation | 1 | - | - |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 7 | - | - |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 6 | 5 | - |

| Platelet count decreased | 2 | 1 | - |

| White blood cell decreased | 10 | 4 | - |

| Anorexia | 1 | 1 | - |

| Dehydration | 5 | - | - |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 | - | - |

| Hypokalemia | 1 | - | - |

| Hyponatremia | 1 | - | - |

| Arthralgia | 1 | - | - |

| Myalgia | 1 | - | - |

| Headache | 1 | - | - |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 1 | - | - |

| Syncope | 1 | - | - |

| Bronchospasm | 1 | - | - |

| Flushing | 1 | - | - |

| Hypertension | 1 | - | - |

| Hypotension | 1 | 1 | - |

| WORST DEGREE | 27 | 11 | 1 |

Table 3:

Treatment-related Toxicities for All Treated Patients (Step 2, Reported by CRFs)

| Treatment Arm B (n=33) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Type | Grade | ||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| (n) | (n) | (n) | |

| Anemia | 1 | - | - |

| Heart failure | 1 | - | - |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 | - | - |

| Death NOS | - | - | 1 |

| Esophageal ulcer | 1 | - | - |

| Hemorrhoidal hemorrhage | 1 | - | - |

| Sepsis | - | 1 | - |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | - | - |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | - | 1 | - |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | - | 1 | - |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 1 | - | - |

| Weight loss | 1 | - | - |

| Treatment related secondary malignancy | 1 | - | - |

| Hypertension | 6 | - | - |

| Thromboembolic event | 1 | - | - |

| WORST DEGREE | 9 | 1 | 1 |

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the safety of bevacizumab and tecemotide after concurrent chemoradiation and consolidation chemotherapy in patients with stage III unresectable non-squamous NSCLC. Per protocol, a two-stage toxicity analysis plan was performed to evaluate the safety of the combination of tecemotide immunotherapy with bevacizumab. The target adverse events for the combined treatment were: grade 4–5 hemorrhage, esophagitis, fistula, thrombocytopenia, encephalitis, or hepatic failure. The stage I safety evaluation confirmed the safety rule was not violated, so the study continued to stage 2. In stage 2, one case of lethal esophageal fistula was reported which was attributed to bevacizumab. Per protocol, if at least 5 or more clearly attributable grade 4–5 adverse events of interest were observed during the maintenance therapy amongst the total 30 treated patients, the new regimen would be considered unacceptable. Because only one of the 33 treated patients in step 2 (3.0%; 80% CI, 0.3–11.3%) experienced a target adverse event, the combined treatment of tecemotide with bevacizumab was thus deemed safe for this patient population.

Efficacy

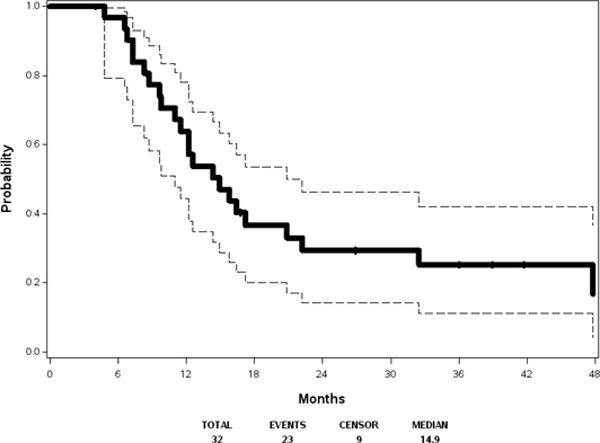

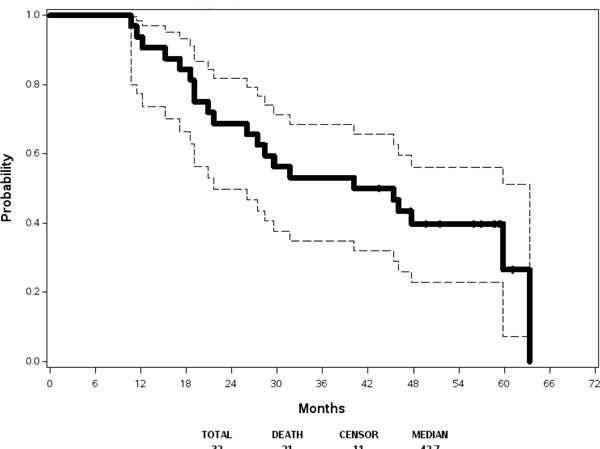

With respect to the best overall response, 2 CR, 34 PR, and 19 SD were observed among the 66 eligible and treated patients in step 1. For the 32 evaluable patients in step 2, Table 4 displays best overall response in step 1 and step 2. Figure 2(a) and Figure 2(b) show Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS and OS, respectively, based on the 32 eligible patients receiving maintenance therapy. Among these 32 cases, 23 patients developed progressive disease. The median progression free survival was 14.9 months (95% confidence interval 11.0, 20.9). The two-year progression free survival was 29% (95% confidence interval 14%, 46%). With a median follow up of 56.9 months among the 11 patients still alive, median overall survival was 42.7 months (95% confidence interval 21.7, 63.3). The two-year overall survival was 69% (95% confidence interval 50%, 82%).

Table 4:

Changes in Best Overall Response between Steps

| Step 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 2 | Partial Response | Stable Disease | Total |

| Complete Response | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Partial Response | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Stable Disease | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| Progression | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Unevaluable | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 23 | 9 | 32 |

Figure 2(a):

Progression-free Survival

Figure 2(b):

Overall Survival

DISCUSSION

This phase 2 cooperative group trial met its primary endpoint, demonstrating acceptable safety of maintenance therapy with bevacizumab and tecemotide after concurrent chemoradiation and consolidation chemotherapy in patients with non-squamous NSCLC. Moreover, in this highly selected group of patients, consolidation therapy with bevacizumab and tecemotide resulted in encouraging outcomes. Comparisons to contemporary trial outcomes are somewhat difficult given that this population was highly selected based upon timely completion and resolution of toxicity from chemoradiation.

Bevacizumab has been an important addition to cancer treatment, improving outcomes when combined with chemotherapy in patients with non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, glioblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, cervical cancer, and ovarian cancer. In addition, there is growing interest in combining bevacizumab with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (21) as well as with immune checkpoint inhibitors (22). Although widely used, bevacizumab also is associated with distinct toxicities that include hypertension, vascular events, proteinuria, delayed wound healing as well as tracheoesophageal fistula. When this trial was designed, there was considerable interest by a number of groups in bringing bevacizumab to the curative setting. Unfortunately, concurrent thoracic chemoradiation and bevacizumab resulted in an unexpectedly high number of fatal tracheoesophageal fistulas.(15,23,24) It was hypothesized that antecedent mucosal injury, evidenced as esophagitis, from combined modality treatment followed by impaired neovascularization and healing resulted in these events. Therefore, in the design of this trial, we required that subjects met quite stringent eligibility criteria at several points and that they had total recovery from radiation toxicity (including esophagitis), prior to receiving bevacizumab. Moreover, a two-step design with strict stopping rules for toxicity was employed.

With this approach, we were able to limit toxicity and demonstrate tolerability of the regimen. Nevertheless, a greater than expected number of patients were unable to complete the prescribed treatment due to progressive disease and ongoing toxicities attributed to chemoradiation. Although 68 eligible patients started therapy, only 33 (49%) were able to advance to step 2 of the protocol treatment (bevacizumab and tecemotide). This observed attrition has significant implications in the design of clinical trials for the stage III patient population in whom toxicities from concurrent chemoradiation are common and may preclude aggressive, potentially curative, therapy for many patients.

Patient outcomes in this trial are encouraging as both PFS and OS appeared superior to historical controls of concurrent chemoradiation—prior to the adoption of consolidative immunotherapy—in patients with stage III NSCLC. We investigated the use of tecemotide, a tumor vaccine with the MUC1 protein as the antigen target. The phase III placebo controlled, randomized START trial assessed tecemotide following concurrent or sequential chemoradiotherapy for stage III NSCLC.(13) No significant difference in median OS was observed between patients who received tecemotide and those who received placebo (25.6 versus 22.3 months). The authors observed a favorable effect of the tecemotide vaccine in the predefined large (n=806) subgroup of patients initially treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, with a remarkable improvement of 10.2 months in median OS (30.8 versus 20.8 months in the placebo group). In contrast, patients who had previously been treated with sequential chemoradiotherapy did not obtain clinical benefit. Importantly, tecemotide was very well tolerated. However, a follow up randomized phase I/II study in Japanese patients with stage III NSCLC could not support the initial promising results and the sponsor decided to stop the development of the drug.

We hypothesized that combining tecemotide with bevacizumab could augment the immune response to the vaccine. There is considerable evidence that angiogenesis and the immune system interact in complex relationship. VEGF not only promotes angiogenesis but also acts as a key mediator of the immunosuppressive microenvironment that enables tumors to evade immune surveillance(25). VEGF signaling has been shown to diminish the antitumor response through a variety of mechanisms including perturbation of cellular trafficking of immune cells. VEGF also has a systemic effect on immune-regulatory cell function through multiple mechanisms, including: induction and proliferation of inhibitory immune cell subsets, such as T-regulatory cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs); suppression of dendritic cell maturation; and inhibition of T-cell development from hematopoietic progenitor cells.(16,26,27) Thus, given the immunosuppressive role of VEGF and angiogenesis within tumors, it is not surprising that there is evidence that antiangiogenic agents stimulate the immune response and enhance the efficacy of immunotherapies. We collected correlative samples to assess dendritic cells as well as other markers that are undergoing analysis and will be reported separately.

Although currently there are no antigen-specific immunotherapies that are indicated in patients with NSCLC, combination consolidation strategies that modulate the tumor vasculature, tumor microenvironment and enhance tumor-specific antigenicity are feasible and could lead to improved outcomes in patients. In particular, investigation of combination strategies utilizing immunotherapy and angiogenic pathways as consolidation could be undertaken.

Clinical Practice Points.

Although chemoradiation is the standard of care for patients with unresectable locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer, many patients relapse with fatal metastatic disease.

Durvalumab immunotherapy after chemoradiation has improved survival for patients, but efforts to further enhance rates of cure are essential.

Antiangiogenic therapy has a role in immune modulation, and bevacizumab improves survival in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer.

Therapy with bevacizumab after chemoradiation in carefully selected patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer is feasible.

Incorporation of bevacizumab in future immunotherapy trials after chemoradiation is reasonable.

Acknowledgments

This study was coordinated by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (Peter J. O’Dwyer, MD and Mitchell D. Schnall, MD, PhD, Group Co-Chairs) and supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the following award numbers: CA180820, CA180794, CA233327, CA233331, CA233270, CA180870, CA189830, CA189808, CA233247 and CA189873. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auperin A, Le Pechoux C, Pignon JP, Koning C, Jeremic B, Clamon G, et al. Concomitant radio-chemotherapy based on platin compounds in patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a meta-analysis of individual data from 1764 patients. Ann Oncol 2006;17(3):473–83 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdj117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoon SM, Shaikh T, Hallman M. Therapeutic management options for stage III non-small cell lung cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2017;8(1):1–20 doi 10.5306/wjco.v8.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curran WJ, Jr., Paulus R, Langer CJ, Komaki R, Lee JS, Hauser S, et al. Sequential vs.concurrent chemoradiation for stage III non-small cell lung cancer: randomized phase III trial RTOG 9410. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103(19):1452–60 doi 10.1093/jnci/djr325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delbaldo C, Michiels S, Rolland E, Syz N, Soria JC, Le Chevalier T, et al. Second or third additional chemotherapy drug for non-small cell lung cancer in patients with advanced disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007(4):CD004569 doi 10.1002/14651858.CD004569.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Chevalier T, Arriagada R, Quoix E, Ruffie P, Martin M, Douillard JY, et al. Radiotherapy alone versus combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy in unresectable non-small cell lung carcinoma. Lung Cancer 1994;10 Suppl 1:S239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley JD, Paulus R, Komaki R, Masters G, Blumenschein G, Schild S, et al. Standard-dose versus high-dose conformal radiotherapy with concurrent and consolidation carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without cetuximab for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer (RTOG 0617): a randomised, two-by-two factorial phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(2):187–99 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71207-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R, et al. Overall Survival with Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2018;379(24):2342–50 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1809697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butts C, Murray N, Maksymiuk A, Goss G, Marshall E, Soulieres D, et al. Randomized phase IIB trial of BLP25 liposome vaccine in stage IIIB and IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(27):6674–81 doi 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wurz GT, Gutierrez AM, Greenberg BE, Vang DP, Griffey SM, Kao CJ, et al. Antitumor effects of L-BLP25 antigen-specific tumor immunotherapy in a novel human MUC1 transgenic lung cancer mouse model. J Transl Med 2013;11:64 doi 10.1186/1479-5876-11-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bafna S, Kaur S, Batra SK. Membrane-bound mucins: the mechanistic basis for alterations in the growth and survival of cancer cells. Oncogene 2010;29(20):2893–904 doi 10.1038/onc.2010.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raina D, Kosugi M, Ahmad R, Panchamoorthy G, Rajabi H, Alam M, et al. Dependence on the MUC1-C Oncoprotein in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. 2011;10(5):806–16 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-1050%J Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehla K, Singh PK. MUC1: a novel metabolic master regulator. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1845(2):126–35 doi 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butts C, Socinski MA, Mitchell PL, Thatcher N, Havel L, Krzakowski M, et al. Tecemotide (L-BLP25) versus placebo after chemoradiotherapy for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer (START): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15(1):59–68 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355(24):2542–50 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spigel DR, Hainsworth JD, Yardley DA, Raefsky E, Patton J, Peacock N, et al. Tracheoesophageal fistula formation in patients with lung cancer treated with chemoradiation and bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(1):43–8 doi 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, Cunningham HT, Meny GM, Nadaf S, et al. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Med 1996;2(10):1096–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabrilovich DI, Ciernik IF, Carbone DP. Dendritic cells in antitumor immune responses. I. Defective antigen presentation in tumor-bearing hosts. Cell Immunol 1996;170(1):101–10 doi 10.1006/cimm.1996.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oyama T, Ran S, Ishida T, Nadaf S, Kerr L, Carbone DP, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor affects dendritic cell maturation through the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B activation in hemopoietic progenitor cells. J Immunol 1998;160(3):1224–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson EN, Brown BW. Confidence limits for probability of response in multistage phase II clinical trials. Biometrics 1985;41(3):741–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric Estimation From Incomplete Observations. American Statistical Association 1958;53(282):457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuya N, Fukuhara T, Saito H, Watanabe K, Sugawara S, Iwasawa S, et al. Phase III study comparing bevacizumab plus erlotinib to erlotinib in patients with untreated NSCLC harboring activating EGFR mutations: NEJ026. 2018;36(15_suppl):9006- doi 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.9006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2018;378(24):2288–301 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1716948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Socinski MA, Stinchcombe TE, Moore DT, Gettinger SN, Decker RH, Petty WJ, et al. Incorporating bevacizumab and erlotinib in the combined-modality treatment of stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(32):3953–9 doi 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.9820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wozniak AJ, Moon J, Thomas CR, Jr., Kelly K, Mack PC, Gaspar LE, et al. A Pilot Trial of Cisplatin/Etoposide/Radiotherapy Followed by Consolidation Docetaxel and the Combination of Bevacizumab (NSC-704865) in Patients With Inoperable Locally Advanced Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: SWOG S0533. Clin Lung Cancer 2015;16(5):340–7 doi 10.1016/j.cllc.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohm JE, Carbone DP. VEGF as a mediator of tumor-associated immunodeficiency. Immunol Res 2001;23(2–3):263–72 doi 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finke JH, Rini B, Ireland J, Rayman P, Richmond A, Golshayan A, et al. Sunitinib reverses type-1 immune suppression and decreases T-regulatory cells in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14(20):6674–82 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabrilovich D, Ishida T, Oyama T, Ran S, Kravtsov V, Nadaf S, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits the development of dendritic cells and dramatically affects the differentiation of multiple hematopoietic lineages in vivo. Blood 1998;92(11):4150–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]