Abstract

Background:

The impact of postoperative opioid use on outcomes for children with perforated appendicitis is unknown.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was performed using the Pediatric Health Information System® (PHIS) database from 2005–2015. Children 2–18y with perforated appendicitis who underwent an appendectomy were identified. Postoperative day (POD) analgesic use was categorized as non-opioid analgesia (NOA) alone, opioids (±NOA), or no analgesics. The impact of postoperative opioid use on postoperative length-of-stay (pLOS) and 30-day readmission was evaluated using multivariable mixed-effects regression analysis.

Results:

Overall, 47,726 children with perforated appendicitis were identified. On POD1, 17.7% received NOA alone, 77.6% received opioids, and 4.7% received no analgesics. On adjusted analysis, POD1 opioid use was associated with a 0.75 day (95% CI: 0.54–0.96) increased pLOS. Starting opioids after POD1 was associated with 2.21 days (95%CI:1.90–2.51) longer pLOS. Among children who received opioids on POD1, continued use of opioids after POD1 was associated with a 1.88 day (95%CI:1.77–1.98) longer pLOS. POD1 opioid use did not significantly impact 30-day readmission.

Conclusions:

Early and continued postoperative opioid use is associated with prolonged pLOS in children undergoing appendectomy for perforated appendicitis. Minimizing opioid use, even on POD2, may result in a decreased postoperative length-of-stay.

TOC

This study found that children with perforated appendicitis who underwent appendectomy and received opioids early in their recovery experienced prolonged hospitalization, and that opioid use later during hospitalization was also associated with 30-day readmission. The importance of this finding underscores the need to develop opioid-sparing pain management protocols for children undergoing appendectomy.

Introduction

In the United States, appendicitis is one of the most common diagnoses in children, making appendectomy the second most common pediatric surgical procedure.1 Approximately 70,000 children are diagnosed with appendicitis each year, of which roughly 30% are perforated.2 Postoperative pain management after appendectomy for perforated appendicitis remains variable, with many surgeons using opioids for pain management.3–5 However, opioid analgesics come with considerable risks, which may complicate recovery including, sedation, vomiting, constipation, respiratory depression, and the potential for dependence.6

Following the addition of pain as the “fifth” vital sign by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) as part of their 2000 recommendations to reducing pain, it is believed that opioid use began to increase significantly,7 contributing to the opioid epidemic.8 Recent opioid stewardship efforts emphasize opioid-sparing strategies as a cornerstone to improve recovery.9,10 Non-opioid analgesics (NOA) such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications can be part of a multi-modal approach for postoperative pain that minimizes opioid use.4,11 However, the timing of opioid administration after surgery and its impact on clinical outcomes is unknown.

The present study identifies a group of healthy children undergoing appendectomy for perforated appendicitis and explores the relationship between postoperative opioid use and clinical outcomes. Specifically, this study aimed to evaluate the timing of opioid and non-opioid analgesic administration to determine how opioid-sparing approaches during postoperative recovery impacted postoperative length-of-stay (LOS) and 30-day readmission.

Methods

Study Design, Participants, and Data Collection Procedures

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the Pediatric Health Information System® (PHIS). The PHIS database is maintained by the Children’s Hospital Association (CHA; Lenexa, KS) and includes clinical and resource utilization data for both inpatient and outpatient encounters for 47 children’s hospitals throughout the United States. All data is de-identified prior to its release for analysis. Data quality is assessed by the PHIS data quality program, which issues quarterly data quality reports to participating hospitals. Overall, PHIS represents approximately 20% of all pediatric hospital admissions in the United States.12 Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles.

All pediatric patients between the ages of 2 to 18 years with a diagnosis of appendicitis (ICD-9-CM 540.9, 540.1, 540.0) who underwent an appendectomy (ICD-9-CM 47.01, 47.09) from January 1, 2005 to October 1, 2015 were identified. Patients with a complex chronic condition, those without pharmacy data, those without LOS available, patients discharged on the same day of surgery and those with missing insurance or gender data were excluded. Patient demographic data included age, gender, race, ethnicity, and insurance status. Hospital characteristics included the United States census region.

Definition of Analgesic Exposure

Analgesic medications of interest included both intravenous and oral opioids and intravenous, oral, and rectal NOAs. NOAs included acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and ketorolac. Medication use was determined from PHIS pharmacy billing data using generic pharmacy codes, which are time-stamped for date of exposure. PHIS does not capture dosage strength and frequency of administration and thus these data were not included in the analysis.

In order to determine the impact of early cessation of opioids, postoperative opioid and non-opioid exposure were stratified by day of administration, starting on postoperative day one (POD 1) and then stratified during POD 2–5. Opioid medications were defined according to Womer et al.’s review of opioid use in hospitalized children using PHIS.13 Postoperative opioid and NOA use was dichotomized into ‘exposed’ versus ‘unexposed’ for each unique postoperative day that a pain medication was prescribed to a patient. Patients discharged on POD 1 were removed when investigating outcomes related to POD 2–5.

Definition of Perforated Appendicitis and Open Appendectomy

Perforated cases were identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) 540.0 (peritonitis, perforation, or rupture), 540.1 (with peritoneal abscess). Acute nonperforated appendicitis cases were identified by ICD-9-CM 542 (other appendicitis; chronic, recurrent, relapsing, subacute), 541 (appendicitis, unqualified), 540.9 (without mention of peritonitis, perforation, or rupture) and excluded. Open procedures were defined by ICD-9-CM 47.09. Laparoscopic procedures were defined by ICD-9-CM 47.01 (laparoscopic appendectomy).

Definition of Outcomes

Outcomes of interest were postoperative length of stay (LOS) calculated by the number of days between the date of surgery and the date of discharge. Inpatient readmission within 30 days of surgery was similarly captured. Emergency room visits and outpatient clinic evaluations were not captured. A subgroup analysis of children with opioid use on POD 2–5 was performed after eliminating children discharged on POD 1.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation. Frequencies were calculated to describe categorical variables. Patient demographic and hospital-level data were compared using bivariate analyses. Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed using Chi-square and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests, respectively. Histograms and Q-Q plots assessed normality for continuous variables.

Multivariable regression with mixed-effects was used for modeling continuous response variables, and logistic regression analysis with mixed-effects was used to determine odds ratios (OR) for postoperative pain management categories and 30-day readmission. Mixed-effects modeling was used to control for unmeasured hospital characteristics that may confound any associations. Covariate selection was based on clinical assessment, availability from the PHIS databases, and variables with a significant bivariate association (p<0.01). Adjustment for the following confounders was performed for each regression analysis: sex, race, ethnicity, age, insurance status, open appendectomy, year of surgery, and hospital region. Patient demographics were included as fixed-effects, while the hospital was a random effect. By using the hospital as a random effect, we controlled for differences in measurement between hospitals. Linear regression was used to analyze continuous response variables, and logistic regression analysis was used to determine odds ratios (OR) for postoperative pain management categories and 30-day readmission after performing multiple imputations for missing race. Model fit and selection was assessed by using likelihood ratio tests, Akaike information criterion (AIC), and Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

Missing race data were handled using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE). Multiple imputation was done assuming that race was missing at random.14,15 Race had 45,104 complete observations (2,622 missing) and was imputed by multinomial logistic for categorical race. Variables used for MI included patient and hospital characteristics, patient insurance status, hospital number and hospital region, patient gender, age, and ethnicity.

Continuous postoperative LOS was evaluated, and significance was tested by comparing results with natural log-transformed outcomes. Results between the continuous and log-transformed length of stay outcomes were consistent at p <0.001. An additional sensitivity analysis was conducted removing outliers with LOS > 30 days; nevertheless, estimates and significance trends were similar at p <0.001.

To assess the degree of unmeasured confounding, an E-value (evidence value) analysis was conducted, which quantifies the minimum strength an unmeasured confounder would need with both the exposure and outcome to remove an association identified in the regression analysis.16 The higher the E-value of an observed result, the less likely the observed exposure-outcome association is affected by an unmeasured confounder. The calculation is based on the risk ratio scale and can be adjusted for other effect measures including odds ratios and continuous outcomes. Separate E-values were calculated for point estimates and lower bounds of the 95% CI.

Data were analyzed using SAS® software 9.4 (copyright © 2016 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and StataCorp (2017) Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. A p-value <0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results

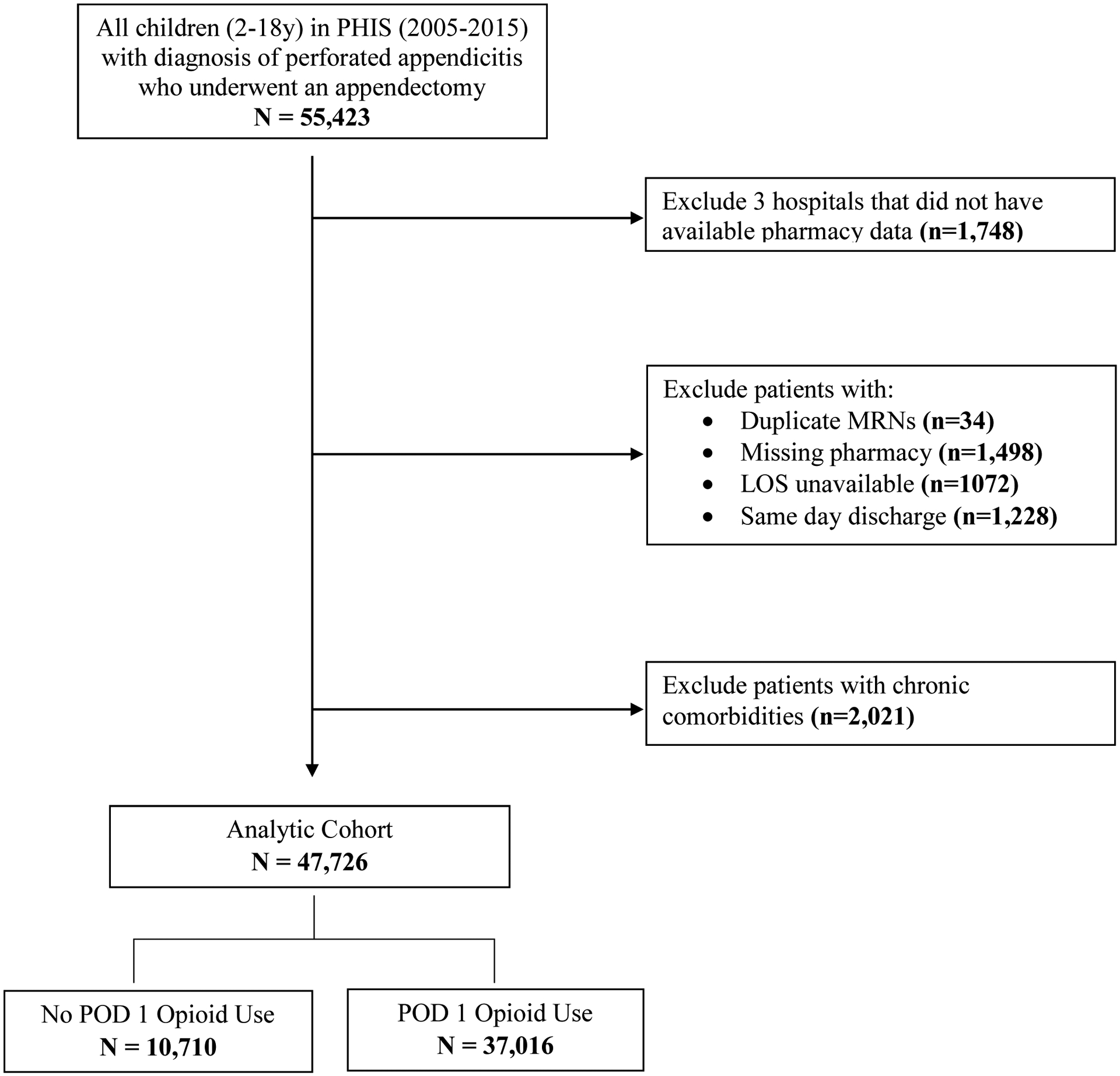

Overall, 47,726 children with perforated appendicitis who underwent an appendectomy at 47 children’s hospitals within PHIS from 2005–2015 were identified (Figure 1). The mean age at admission was 9.6 (±3.9) years and did not differ between groups. Mean postoperative LOS was 5.1 (±3.6) days overall, with a median of 5 days. Mean postoperative LOS was lower for children receiving NOA on POD 1 compared to children who received opioids ± NOA, (4.4 ± 3.4 days vs. 5.3 ± 3.5 days, p<0.0001). Overall, postoperative LOS gradually decreased for the entire cohort over time from a mean of 5.7 (±3.9) days in 2005 to 4.3 (±3.2) days in 2015.

Figure 1:

Flow diagram of cohort selection

LOS = length of stay; PHIS = Pediatric Health Information System; POD = Postoperative Day

The cohort’s overall postoperative opioid use decreased from 88.15 in 2005 to 73.05% in 2015, while NOA use increased from 11.9% to 27.0% (Figure S1). Of this cohort, 77.6% (N=37,016) received an opioid with or without NOA, 17.7% (N=8,448) received NOA alone, and 4.7% (N=2,262) received no analgesics on POD 1. From bivariate analyses, the children who received an opioid on POD 1 were more likely to be white (66.8% vs. 60.2%), have a longer postoperative LOS (5.3±3.5 vs. 4.4±3.4 days, P<0.0001), and a lower incidence of 30-day readmission (16.0% vs. 17.8%, P<0.0001) compared to those who received NOA only (Table 1). After adjustment for potential confounders, opioid use on POD 1 was associated with a 0.75 day (95% CI: 0.54–0.96) longer postoperative LOS compared to children who received NOA only (Table 2). Opioid use on POD 1 was not significantly associated with 30-day readmission.

Table 1.

Cohort Demographics by Postoperative Day 1 Analgesic Use.

| Total N= 47,726 | NOA Alone N=8,448 | Opioid (±NOA) N=37,016 | No Analgesia N=2,262 | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Hospital Region | |||||||||

| Midwest | 8536 | 17.9 | 1727 | 20.4 | 6454 | 17.4 | 355 | 15.7 | <0.0001 |

| Northeast | 4556 | 9.6 | 557 | 6.6 | 3589 | 9.7 | 410 | 18.1 | |

| South | 19203 | 40.2 | 3024 | 35.8 | 15298 | 41.3 | 881 | 39.0 | |

| West | 15429 | 32.3 | 3140 | 37.2 | 11673 | 31.6 | 616 | 27.2 | |

| Male gender | 28179 | 59.0 | 4938 | 58.5 | 21894 | 59.2 | 1347 | 59.6 | 0.2375 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 19569 | 41.0 | 3654 | 43.3 | 15096 | 40.8 | 819 | 36.2 | <0.0001 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 18478 | 38.7 | 3378 | 40.0 | 14289 | 38.6 | 811 | 35.9 | |

| Unknown | 9679 | 20.3 | 1416 | 16.8 | 7631 | 20.6 | 632 | 27.9 | |

| Race | |||||||||

| Missing | 2622 | 5.5 | 558 | 6.6 | 1925 | 5.2 | 139 | 6.2 | <0.0001 |

| White | 31210 | 65.4 | 5085 | 60.2 | 24726 | 66.8 | 1399 | 61.9 | |

| Black | 3828 | 8.0 | 558 | 6.6 | 3034 | 8.2 | 236 | 10.4 | |

| Asian | 1093 | 2.3 | 244 | 2.9 | 806 | 2.2 | 43 | 1.9 | |

| Indigenous Nations and Pacific Islands* | 701 | 1.5 | 42 | 1.9 | 55 | 0.7 | 604 | 1.6 | |

| Other | 8272 | 17.3 | 1948 | 23.1 | 5921 | 16.0 | 403 | 17.8 | |

| Insurance | |||||||||

| Private | 13759 | 28.8 | 2650 | 31.4 | 10548 | 28.5 | 561 | 24.8 | <0.0001 |

| Public | 20050 | 42.0 | 3944 | 46.7 | 15264 | 41.2 | 842 | 37.2 | |

| Other | 13917 | 29.2 | 1854 | 22.0 | 11204 | 30.3 | 859 | 38.0 | |

| Open Appendectomy | 6255 | 13.1 | 949 | 11.2 | 4963 | 13.4 | 343 | 15.2 | <0.0001 |

| 30-day readmission | 7770 | 16.3 | 1501 | 17.8 | 5918 | 16.0 | 351 | 15.5 | <0.0001 |

American Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

LOS = Length-of-stay; SD = Standard Deviation

Table 2.

Association* Between Postoperative Day 1 Analgesic Use and Postoperative LOS and 30-Day Readmission

| Postoperative LOS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative Analgesia | Estimate | 95% CI | |

| NOA Alone | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No Analgesia | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.89 |

| Opioid (± NOA) | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.96 |

| 30-Day Readmission | |||

| Postoperative Analgesia | OR | 95% CI | |

| NOA Alone | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No Analgesia | 0.97 | 0.85 | 1.11 |

| Opioid (± NOA) | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.13 |

Multivariable regression analysis controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance, open appendectomy, year of surgery and hospital region. Reference group is NOA alone.

OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; NOA=non-opioid analgesia; LOS = Length-of-stay

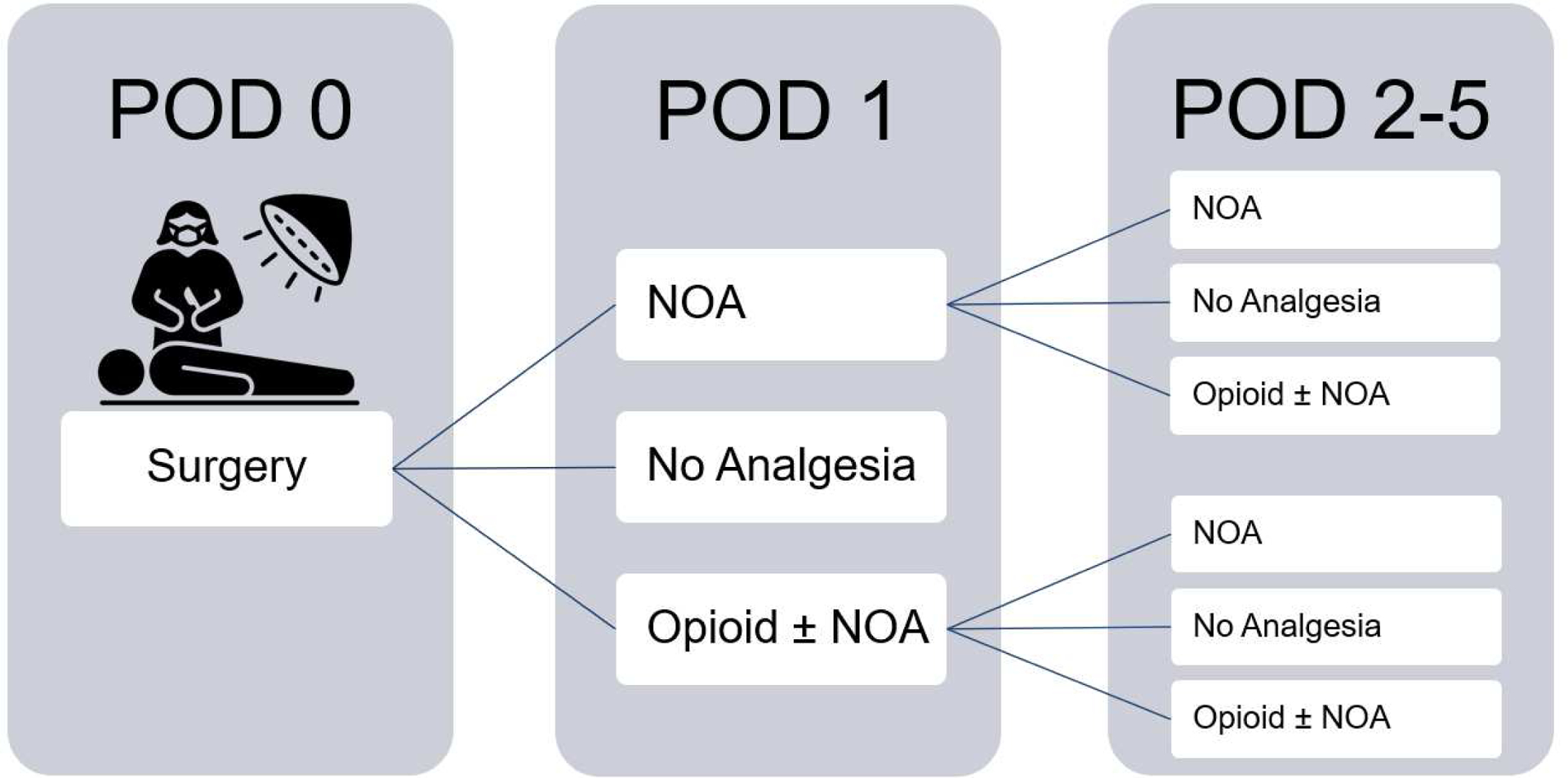

Figure 2 outlines the study flow through subgroup analysis. In a subgroup analysis of children who received only NOA on POD 1, 8.7% (N=762) received no further analgesics on POD 2–5, 49.6% (N=4355) received only NOA, 41.7% (N=3659) received opioids with or without NOA. Starting opioids on POD2 was associated with 2.21 days (95% CI: 1.90–2.51) longer postoperative LOS and increased odds of 30-day readmission (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.17–1.53) (Table 3A) compared to children limited to NOA.

Figure 2.

Postoperative Analgesia Stratified by Day of Administration

POD = Postoperative Day; NOA=non-opioid analgesia

Table 3.

Association Between* of Postoperative Day 2–5 Analgesic Use and Postoperative LOS and 30-Day Readmission

| A. No POD 1 Opioid Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative LOS | |||

| Postoperative Analgesia | Estimate | 95% CI | |

| NOA Alone** | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No Analgesia | 1.13 | 0.66 | 1.61 |

| Opioid (± NOA) | 2.21 | 1.90 | 2.51 |

| 30-Day Readmission | |||

| Postoperative Analgesia | OR | 95% CI | |

| NOA Alone** | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No Analgesia | 1.30 | 1.05 | 1.62 |

| Opioid (± NOA) | 1.33 | 1.17 | 1.53 |

| B. POD 1 Opioid Use | |||

| Postoperative LOS | |||

| Postoperative Analgesia | Estimate | 95% CI | |

| NOA Alone | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No Analgesia | −0.39 | −0.62 | −0.17 |

| Opioid (± NOA) | 1.88 | 1.77 | 1.98 |

| 30-Day Readmission | |||

| Postoperative Analgesia | OR | 95% CI | |

| NOA Alone | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No Analgesia | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.84 |

| Opioid (± NOA) | 1.35 | 1.24 | 1.48 |

Multivariable regression analysis controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance, open appendectomy, year of surgery and hospital region. Reference group is NOA alone.

Children who received no opioids on POD 1 and NOA alone on POD 2–5 received no opioids during postoperative recovery and were the reference group.

OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; NOA=non-opioid analgesia

In a subgroup analysis of children who received an opioid on POD 1, 81.6% (N=28,161) continued to receive an opioid during the remainder of their hospitalization, 14.6% (N=5,027) transitioned to NOA, and 3.8% (N=1,318) had no further analgesic use. In this group of children who received opioids on POD 1, continued use of opioids on POD 2 or later was associated with a 1.88 day (95% CI: 1.77–1.98) longer postoperative LOS and increased likelihood of 30-day readmission (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.24–1.48) (Table 3B) compared to those limited to NOA after POD 1.

Supplemental tables S1 and S2 outline E-value sensitivity analyses for each regression model. E-values of 1.72 and 1.20 were calculated for the multivariable regression of postoperative day 1 opioid use and postoperative LOS and 30-day readmission (Table S1). For children who did not receive an opioid on POD 1, an E-value of 2.83 for postoperative LOS and 1.57 for likelihood of 30-day readmission was observed for children who received opioid analgesics on POD 2–5 (Table S2). Finally, an E-value of 2.64 for postoperative LOS was noted for children who did receive an opioid on POD 1 and continued to receive opioids on POD 2–5, alongside an E-value of 1.60 for 30-day readmission.

Discussion

In this large, multicenter retrospective study of children with perforated appendicitis who underwent appendectomy, we evaluated the impact of opioid use on postoperative LOS and 30-day readmission. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the timing of postoperative opioid use and cessation compared with NOA in children with perforated appendicitis. We found that the use of opioids on POD 1 was associated with a prolonged postoperative LOS. Furthermore, the timing of postoperative opioids used later during hospitalization was associated with both postoperative LOS and 30-day readmission. Children who did not receive opioids on POD 2 or later exibited a shorter postoperative LOS and a decreased likelihood of 30-day readmission, although severity of perforated appendicitis was unable to be assessed.

Opioids are commonly used for the management of postoperative pain in children with perforated appendicitis.17 However, retrospective reviews of electronic health records show that opioid use after surgery can be associated with respiratory depression, constipation, and abdominal pain,18 all factors that can contribute to prolonged hospitalization. Ultimately, the clinical reasons leading to prolonged postoperative length of stay in this study cannot be determined from an administrative database. One of the cornerstones of enhanced recovery after surgery management algorithms is the minimization of opioids in the postoperative phase.19 Previous reports of children with simple appendicitis found that elimination of IV opioid analgesia decreased oral opioid use and shortened hospitalization.20 The current study underscores similar effects in children with perforated appendicitis, showing that eliminating opioid use on POD 2–5 is associated with a significantly decreased postoperative stay. However, future studies aimed at minimizing opioid use for children with perforated appendicitis must be balanced by measurement of patient-reported pain scores as children with perforated appendicitis typically report more pain, use more opioids, and have a higher incidence of respiratory depression than children with simple appendicitis.4

In the modern era of opioid stewardship, maximizing the use of non-opioid analgesia is an increasingly essential component of postoperative recovery protocols. Historically, opioid-sparing strategies began prior to 2015,21,22 but increased signficantly in more recent years.11,23–25 In the present study, utilization of NOA early in the postoperative phase and continuing utilization during hospitalization was associated with decreased postoperative LOS. Studies of other painful pediatric surgical procedures such as tonsillectomy26 and humerus fracture fixation25 have also demonstrated improved outcomes and expedited recovery when maximizing nonopioid analgesia. Other studies evaluating the effect of extended release liposomal bupivacaine injection as a form of long acting non-opioid local analgesic27 on postoperative pain following single-level lumbar spine surgery28, pharyngoplasty, and palatoplasty29 demonstrated low postoperative opioid use and decreased overall hospital length of stay. Further studies of optimal timing, dosing, and extended use of NOA, including long acting local anesthetics such as liposomal bupivacaine, after surgery are warranted in an effort to maximize the effectiveness of NOA alongside other opioid-sparing strategies for children with perforated appendicitis.

The present study also demonstrated that 30-day readmission was not associated with POD 1 opioid administration, but was associated with opioid use later during hospitalization. Early postoperative opioid use is unlikely to clinically impact a child’s readiness for discharge several days later. However, previous studies have shown that extended inpatient opioid use, particularly prior to discharge, is associated with increased likelihood of receiving an opioid medication at discharge.30,31 Anderson et al.’s retrospective study of 590 children who underwent appendectomy found that children receiving an opioid prescription at discharge were more likely to return to the ER or be readmitted with complaints of abdominal pain and constipation.32 Opioid use during the latter days of hospitalization could be associated with a child’s likelihood to receive an opioid prescription at discharge, however, the present study was unable to determine whether children receiving opioids during POD 2–5 were then discharged home with an opioid prescription. Further, granular studies examining the timing and dosage of inpatient opioids alongside discharge prescriptions for children with appendicitis are warranted.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the PHIS database and the lack of detailed information available regarding dosing of analgesics, pediatric pain scores, and clinical the severity of perforated appendicitis. It could be that children with more severe perforated appendicitis stay longer in the hospital or receive more oral morphine equivalents of opioids. The longer a child is in the hospital, the more likely they are to receive opioid pain medication and have a greater cumulative opioid exposure. Furthermore, children with more severe perforated appendicitis likely have more pain and receive more opioid medication, also contributing to prolonged hospitalization. This study was designed to identify associations between timing of postoperative opioid use and outcomes. Timing of postoperative opioid use and overall opioid prescribing patterns have changed in more recent years and could be incorporated into future predictive models for children requiring surgery. However, any algorithm predicting outcomes after surgery must include clinical factors of disease severity, which are not captured in administrative datasets. Alternatively, adequate pain control postoperatively (a proxy being no need for opioids post-procedure) could be associated with lower postoperative LOS. However, in the present study, the strongest odds ratio and the largest E-values were observed in children who stopped using opioids after POD 1 and continued to receive only NOA. This likely indicates that the precise timing of opioid administration is not as influential as an overall postoperative protocol geared towards opioid minimization in the early stages of recovery. In addition, administrative datasets have poor sensitivity and specificity for identifying surgical complications such as postoperative infection33 and we therefore are unable to determine whether the reason for readmission was an infectious complication versus a child presenting with abdominal pain and constipation. Also, the current study was not able to evaluate patient-reported pain scales as these may drive reliance on opioids early in postoperative recovery. However, the higher prescription opioid dose has been reported to be associated with worse patient-reported pain outcomes and more healthcare utilization.34 Future efforts to implement opioid stewardship in children after surgery must use validated pediatric measures of patient-reported pain and determine limitations of NOA to maintain goals of opioid stewardship alongside our duty to provide patient-centered care.

Conclusions

Postoperative opioid use is associated with prolonged postoperative length of stay in children undergoing appendectomy for perforated appendicitis. Opioid use that continues after POD 1 is also associated with an increased likelihood of 30-day readmission. However, eliminating opioid use, even on POD 2 was associated with a decreased postoperative length of stay. Future studies including a comprehensive assessment of inpatient and outpatient pain scores alongside inpatient and outpatient opioid use and postoperative outcomes are needed to build a holistic, patient-centered approach to minimizing opioid use while maximizing postoperative recovery for children.

Supplementary Material

Funding/Support:

Dr. Kelley-Quon is supported by grant KL2TR001854 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Findings from this study were presented during a podium presentation on February 6, 2020, at the Academic Surgical Congress in Orlando, Florida.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure:

None of the authors have any personal or financial conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Witt WPMPH, Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays for Children in the United States, 2012.; 2012. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb181-. Accessed January 14, 2020. [PubMed]

- 2.Barrett ML, Hines AL, Andrews RM. Trends in Rates of Perforated Appendix, 2001–2010: Statistical Brief #159.; 2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24199256. Accessed January 14, 2020.

- 3.Pergolizzi JV, Raffa RB, Tallarida R, Taylor, Labhsetwar SA. Continuous Multimechanistic Postoperative Analgesia: A Rationale for Transitioning from Intravenous Acetaminophen and Opioids to Oral Formulations. Pain Pract. 2012;12(2):159–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00476.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Seipel C, Lopez ME, et al. A retrospective study of multimodal analgesic treatment after laparoscopic appendectomy in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(12):1187–1192. doi: 10.1111/pan.12271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wininger SJ, Miller H, Minkowitz HS, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter, Repeat-Dose Study of Two Intravenous Acetaminophen Dosing Regimens for the Treatment of Pain After Abdominal Laparoscopic Surgery. Clin Ther. 2010;32(14):2348–2369. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S105–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker DW. History of the joint commission’s pain standards: Lessons for today’s prescription opioid epidemic. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2017;317(11):1117–1118. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gostin LO, Hodge JG, Noe SA. Reframing the opioid epidemic as a national emergency. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2017;318(16):1539–1540. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gostin LO, Hodge JGJ, Noe SA. Reframing the Opioid Epidemic as a National Emergency. JAMA. 2017;318(16):1539–1540. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnie RJ, Kesselheim AS, Clark DJ. Both Urgency and Balance Needed in Addressing Opioid Epidemic. JAMA. 2017;318(5):423. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manworren RCB, McElligott CD, Deraska PV, et al. Efficacy of Analgesic Treatments to Manage Children’s Postoperative Pain After Laparoscopic Appendectomy: Retrospective Medical Record Review. AORN J. 2016;103(3):317.e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane JM, Colvin JD, Bartlett AH, Hall M. Opioid-Related Critical Care Resource Use in US Children’s Hospitals. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173335. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Womer J, Zhong W, Kraemer FW, et al. Variation of Opioid Use in Pediatric Inpatients Across Hospitals in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(5):903–914. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.12.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, Leaf PJ. Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(1):40–49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Der Weele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268–274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lasky T, Greenspan J, Ernst FR, Gonzalez L. Morphine Use in Hospitalized Children in the United States: A Descriptive Analysis of Data From Pediatric Hospitalizations in 2008. Clin Ther. 2012;34(3):720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cepeda MS, Gonzalez F, Granados V, Cuervo R, Carr DB. Incidence of nausea and vomiting in outpatients undergoing general anesthesia in relation to selection of intraoperative opioid. J Clin Anesth. 1996;8(4):324–328. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(96)00042-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Echeverria-Villalobos M, Stoicea N, Todeschini AB, Fiorda-Diaz J, Uribe AA, Weaver TBS. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS): A Perspective Review of Postoperative Pain Management Under ERAS Pathways and Its Role on Opioid Crisis in United States. Clin J Pain. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cundy TP, Sierakowski K, Manna A, Cooper CM, Burgoyne LL, Khurana S. Fast-track surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis in children: a matched case-control study. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87(4):271–276. doi: 10.1111/ans.13744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong I, St John-Green C, Walker SM. Opioid-sparing effects of perioperative paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(6):475–495. doi: 10.1111/pan.12163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pergolizzi JV, Raffa RB, Tallarida R, Taylor R, Labhsetwar SA. Continuous Multimechanistic Postoperative Analgesia: A Rationale for Transitioning from Intravenous Acetaminophen and Opioids to Oral Formulations. Pain Pract. 2012;12(2):159–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00476.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sola R, Desai A, Gonzalez K, et al. Does Intravenous Acetaminophen Improve Postoperative Pain Control after Laparoscopic Appendectomy for Perforated Appendicitis? A Prospective Randomized Trial. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2019;29(02):159–165. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1615276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Echeverria-Villalobos M, Stoicea N, Todeschini AB, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS): A Perspective Review of Postoperative Pain Management Under ERAS Pathways and Its Role on Opioid Crisis in the United States. Clin J Pain. 2020;36(3):219–226. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams AJ, Buczek MJ, Flynn JM, Shah AS. Perioperative Ketorolac for Supracondylar Humerus Fracture in Children Decreases Postoperative Pain, Opioid Usage, Hospitalization Cost, and Length-of-Stay. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(6):e447–e451. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly LE, Sommer DD, Ramakrishna J, et al. Morphine or Ibuprofen for Post-Tonsillectomy Analgesia: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):307–313. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Candiotti K Liposomal bupivacaine: an innovative nonopioid local analgesic for the management of postsurgical pain. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(9 Suppl):19S–26S. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01183.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puffer RC, Tou K, Winkel RE, Bydon M, Currier B, Freedman BA. Liposomal bupivacaine incisional injection in single-level lumbar spine surgery. Spine J. 2016;16(11):1305–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day KM, Nair NM, Griner D, Sargent LA. Extended Release Liposomal Bupivacaine Injection (Exparel) for Early Postoperative Pain Control Following Pharyngoplasty. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(3):726–730. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.J. K, C.W. S, C.H. C, et al. Patterns of inpatient, intensive care, and post-discharge opioid prescribing to opioid-naive patients in a large health system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:A7667. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill MV, Stucke RS, Billmeier SE, Kelly JL, Barth RJ. Guideline for Discharge Opioid Prescriptions after Inpatient General Surgical Procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(6):996–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson KT, Bartz-Kurycki MA, Ferguson DM, et al. Too much of a bad thing: Discharge opioid prescriptions in pediatric appendectomy patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(12):2374–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawson EH, Louie R, Zingmond DS, et al. A comparison of clinical registry versus administrative claims data for reporting of 30-day surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2012. December;256(6):973–81. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b4c4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morasco BJ, Yarborough BJ, Smith NX, et al. Higher Prescription Opioid Dose is Associated With Worse Patient-Reported Pain Outcomes and More Health Care Utilization. J Pain. 2017;18(4):437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.