Abstract

Background

Electrical Stimulation is a traditional tool in neuroscience and is commonly used in vivo to evoke behavior and in vitro to study neural mechanisms. In vivo intracerebral microdialysis, also a traditional technique, is used to assay neurotransmitter release. However, the combination of these techniques is highly limited to studies using anesthetized animals; therefore, evoking and measuring exocytotic neurotransmitter release in awake models is lacking. Combining these techniques in an awake animal preparation is presented here with evidence to support the mechanistic action of electrical stimulation in vivo.

New Methods

This report presents converging evidence to validate the combination of intracerebral electrical stimulation with microdialysis as a novel procedure to study exocytotic-like dopamine release in behaving animals.

Results

It is shown that electrical stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle can be used to evoke frequency- and intensity-dependent exocytotic-like dopamine overflow and rotational behavior that are sensitive to Na+ channel blockade and Ca++ availability.

Comparison with Existing Methods

Studies using modern techniques to evoke neurotransmitter release, combined with in vivo intracerebral microdialysis, and measured behavioral output are scarce. In contrast, commonly used pharmacological methods often are less precise and inefficient to evoke exocytotic dopamine release and behavior. Here we demonstrate, the combination of in vivo intracerebral microdialysis with electrical stimulation as a simple approach to simultaneously assess physiologically relevant neurotransmitter ‘release’ and behavior.

Conclusions

Research that aims to understand how dopamine neurotransmission is altered in behavioral disorders, can utilize this innovative combination of electrical stimulation with in vivo intracerebral microdialysis.

Keywords: Electrical stimulation, rotational behavior, nigrostriatal dopamine, exocytosis, sodium channels, calcium

1. Introduction

The strength of in vivo intracerebral microdialysis (IVMCD) is its ability to estimate changes in neurotransmitter release simultaneously with ongoing changes in behavior. Therefore, this technique is commonly utilized to study the neurochemical bases of behavioral disorders in animal models. However, a caveat of this approach is that changes in dialysate levels of neurotransmitter are only an epiphenomenon – that is, changes in extracellular levels of neurotransmitter do not necessarily indicate how or what presynaptic mechanisms regulating exocytosis are altered. Therefore, it is critical to incorporate available methodologies that activate targeted presynaptic modulators of neurotransmitter overflow.

An inordinate number of studies utilize pharmacological challenges to evoke neurotransmitter overflow as a measure of “releasability.” However, many of these manipulations do not recruit physiologically relevant aspects of exocytosis. For example, amphetamine is often used because it evokes DA overflow that correlates very well with elicited psychomotor stimulant behavior (Robinson et al., 1994; Meyer & Bardo 2015; Wan et al., 1996). Amphetamine increases extracellular DA by an exchange/diffusion mechanism at the level of the DA transporter protein (Fischer & Cho, 1979; Parker & Cubeddu, 1986; Levi & Raiteri, 1993; Raiteri et al., 1979; Kahlig et al., 2005, for review see Sulzer et al., 2005) that primarily relies on the cytoplasmic DA pool. Therefore, a major shortcoming of amphetamine-evoked release is that it does not reflect the depolarization, calcium (Ca++)-mediated, release of DA from vesicular pools. To address this shortcoming, potassium stimulation has been used to produce depolarization-based overflow that more likely reflects release from the vesicle-bound pool of DA (Abercrombie & Zigmond, 1989; Lindefors et al., 1989; Casanova et al., 2013; Tran-Nguyen et al., 1996, Ton et al., 1988, Stanford et al., 2000). Unfortunately, potassium-induced depolarization fails to evoke behavioral activation. Therefore, a major limitation of both amphetamine administration and potassium stimulation is the protracted pharmacokinetics of these approaches. A parenteral injection of amphetamine produces a response that lasts approximately two hours, and a prolonged infusion of potassium is necessary to observe DA overflow via IVMCD. There is a need for a methodological approach that produces a functional index of DA release that more closely mimics exocytosis during behavioral flux.

Electrical stimulation (ES) has been historically used due to its regulatory properties upon voltage-dependent membrane ion permeability (Hodgkin & Huxley 1952), synaptic calcium (Ca++) signaling (Llinas et al., 1981), and vesicle-based neurotransmission (Katz & Miledi, 1965; Llinas & Heuser, 1977). There is also a historical precedence for using ES to activate brain systems to understand its behavioral organization (Krug et al., 2015). Early studies used ES to map the motor homunculus (Fritsch & Hitzig, 1870; Penfield & Jasper, 1954; Woolsey, 1979), to localize reward centers (Olds & Milner, 1954), and to explore the nature of motivational states (Hoebel & Teitelbaum, 1962; Valenstein et al., 1970; Berridge & Valenstein, 1991). ES continues to be used in present day research, such as to understand the neural organization of the prefrontal cortex in fear conditioning (Milad & Quirk, 2002), the subfornical organ in feeding (Smith et al., 2010), and the habenula in modulating sucrose intake (Friedman et al., 2011). These studies support the notion that ES reliably evokes physiologically relevant activation of exocytotic properties and behavioral responses.

In this parametric study we report an animal preparation to validate the use of ES in behaving animals to induce activation of endogenous presynaptic mechanisms regulating exocytosis simultaneously with stimulus-bound behavior. This report describes the feasibility of using ES to evoke reliable and reproducible exocytotic-like DA release that results in Electrically-Stimulated Rotational Behavior, i.e. ESRB (Pycock, 1980; Castañeda et al., 1985). Unilateral ES evokes a robust rotational behavior exclusive of other locomotor and stereotypical behaviors when electrodes are accurately placed at the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) of the nigrostriatal pathway. We further demonstrate that IVMCD combined with ES at the MFB produces reproducible, stimulus-bound ESRB and DA overflow that are 1) sodium (Na+) channel-dependent, 2) intensity-dependent, 3) frequency-dependent, and 4) and calcium (Ca++)-dependent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Forty-three adult male and female rats (Sprague-Dawley/Wistar) weighing 250–400 g were maintained on a reversed 12:12 hr light/dark cycle (lights on 20.00 h), and ad lib food and water were available at all times. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by both the Arizona State University (Protocol # ASU 02–641R) and University of Texas at El Paso (Protocol # A201106–1) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

2.2. General Procedures

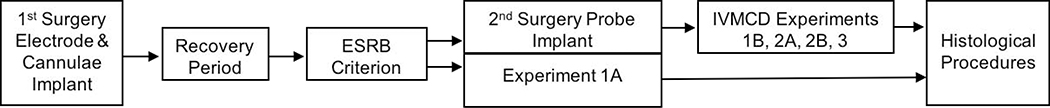

Figure 1 shows the general timeline of procedures used to conduct ES validation experiments.

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline. See text for full description.

2.2.1. Stereotaxic Procedures

A surgical level of anesthesia was induced via three approaches: 1) anesthetic cocktail (50 mg ketamine, 5 mg xylazine, 1 mg acepromazine/kg body weight) given either i.m, or i.p. for experiments conducted at Arizona State University; and 2) 2% isoflurane inhalant anesthesia or 3) a combination of the cocktail and isoflurane anesthetics to improve surgical outcomes at the University of Texas at El Paso. All implants were conducted with a flat skull in reference to bregma and dura. Implantations were secured by forming a dental cement cap around stainless steel screws anchored to the skull. Bipolar twisted stainless-steel electrodes were purchased from Plastics One (MS303/3, 0.150, 0.125 mm diameter). The coordinates for bilateral electrode implantations were: P 2.5, L 1.8, V 8.4, except for Experiment 1B. In Experiment 1B coordinates for the electrodes were adjusted to: P 4.4, L 1.2, V 8.7 to accommodate guide cannulae aimed at the MFB.

In Experiment 1A, guide cannulae for microinfusions of lidocaine were constructed from 23 ga stainless steel tubing (0.635 OD, 0.330 ID). The coordinates to implant bilateral guide cannulae aimed at the caudate/putamen (Cd/P) were: A 0.5, L 2.5, V 4.0. In Experiment 1B, microinfusions were aimed at the MFB so coordinates for guide cannulae were adjusted to: P 2.5, L 1.8, V 5.0. Microdialysis probes (4 mm effective length, 250 μm OD) were constructed as previously described by Robinson & Whishaw (1988). The coordinates to implant microdialysis probes aimed at the Cd/P were: A 0.5, L 2.5, V 7.0. All microdialysis experiments utilized bilateral probe implants except for Experiment 1B which utilized a unilateral implant.

2.2.2. ESRB (A Priori Criterion)

Three to five days after the first stereotaxic surgery animals were tested for ESRB. At the beginning of each test day, the stimulator was calibrated on a Tektronix (model # TDS 320) oscilloscope for pulse duration and frequency. Animals received monophasic rectangular pulses to the MFB delivered by a Grass Model S2 stimulator. Current was administered in an ascending order of intensity (50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 μA) at 50 Hz with 0.1 ms pulse duration, 10 sec train duration, and 120 sec ISI as described in Castañeda et al., (1985). A Grass Model CCU 1A constant current unit was used to adjust the current across increasing intensities, first with normal (positive) current flow. Then the intensity curve was repeated with reversed (negative) current flow on each electrode. This procedure was repeated for five days. To be included, an a priori criterion was required of at least 8 quarter turns during the 10 s train at 300 μA from one of the two electrodes at either normal or reversed current flow. Rats that met this criterion either proceeded to behavioral testing for Experiment 1A or underwent a second stereotaxic surgery for implantation of microdialysis probes into the Cd/P (Experiments 1B, 2, 3).

2.2.3. Microdialysis Procedures

Dialysate values were corrected for recovery. Prior to implantation in a second surgery, all microdialysis probes were tested for in vitro recovery to account for differences in sampling efficiency as previously described by Castañeda et al. (1990). In vitro recovery was conducted using 0.2 μm-filtered Ringer’s solution, consisting of 128.3 mM NaCl, 1.35 mM CaCl2, 2.68 mM KCl, 2.0 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.3. Probes were placed into a dish with quiescent monoamine standard in Ringer’s solution and two 10-min dialysis recovery samples collected. The standard was stirred just prior to starting each sample collection. The mean (±SEM) percent recovery values for the probes used in Experiment 1B (conducted at UTEP) were: DA, 27.3% ± 1.1; 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl acetic acid (DOPAC), 23.8% ± 0.7; Homovanillic acid (HVA), 22.9% ± 0.8; and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic (5-HIAA), 22.5% ± 0.9. For Experiments 2 and 3 (conducted at ASU), the values were: DA = 21.0% ± 0.1, DOPAC = 19.6% ± 0.1, HVA = 16.2% ± 0.1, 5HIAA = 16.5% ± 0.1.

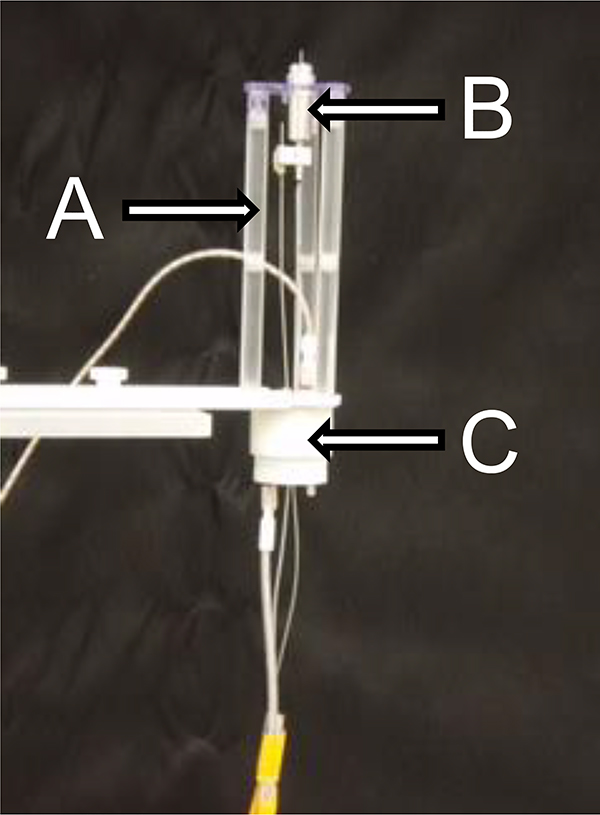

Animals underwent a second surgery to implant dialysis probes the day before IVMCD testing and subsequently placed into a plexiglas test chamber (30 X 35 X 37 cm) to recover overnight. The experimental setup consisted of a head pedestal with fluid lines from the microdialysis probe and electrical wires connected to the previously implanted electrode ascending to a horizontal L-shaped plexiglas support stand (22 cm vertical length X 13 cm horizontal length X 10 cm wide, 0.8 cm thick) located 46 cm above the test chamber floor. To prevent these fluid and electrical lines from becoming tangled during behavioral testing, Figure 2 shows the plexiglas support stand on which a swivel flange (Plastics One Model FSM-1) was mounted to integrate an Instech fluid commutator (Model 375/D/22QM) and an electrical commutator (Plastics One Model SL2C). The general protocol was initiated with baseline collections (10 or 20 min) until three samples varied <10% from each other. Subsequently, an experimental manipulation was implemented as detailed in each of the specific experiments involving 10-min sample collections. Dialysate samples were collected using Ringers solution (see above), and immediately assayed for DA, DOPAC, HVA and 5HIAA using standard HPLC-EC procedures (Castañeda et al., 1990).

Figure 2.

Integration of Electrical and Fluid Commutators to Prevent Tangling During Movement. The image depicts (A) the plexiglas swivel flange (Plastics One, Model FSM-1) placed immediately above the testing chamber that integrates (B) the fluid commutator (Instech, Model 375/D/22QM) used to deliver Ringers for IVMCD and (C) electrical commutator (Plastics One, Model SL2C) used for ES.

2.2.4. Histological Procedures

All animals received 100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (ip) to achieve deep anesthesia. Next, standard intracardiac perfusion was conducted, first with buffered saline followed by 4% formaldehyde in buffered saline. Extracted brains were cryoprotected by placing into 30% sucrose with 4% paraformaldehyde. Coronal sections were obtained on a Leica CM 1850 cryostat, stained with cresyl violet, and examined for accurate placement of electrodes, infusion cannulae, and microdialysis probes.

2.3. Experiment 1: Na+ Channel Dependence

2.3.1. Experiment 1A: The Linear Relationship of ESRB with Increasing Intensity of ES and Na+ Channel Dependence

For rats used in this study, the data collected during five days of a priori testing was used to calculate a linear regression between ESRB and ES intensities. On a separate test day, baseline ESRB was collected immediately before Na+ channel blockade. Using the guide cannula, 4% lidocaine or saline was infused (0.5 μl/min, 12 min) through a 30 ga infusion cannula aimed −7.0 mm below dura into the Cd/P ipsilateral to the stimulating electrode. The dose of lidocaine was chosen after an extensive literature review (eg, Bracha et al., 1993; Delfs et al, 1990; Ikemoto & Goeders, 1998; Martin, 1991; Mura et al., 1998). After infusion, the cannula was left in place for three min to allow for diffusion. Animals were subsequently tested for ESRB, with stimulus intensities randomized, beginning one minute after the cannula was removed.

2.3.2. Experiment 1B Na+ Channel Dependence of Electrically Evoked DA, ESRB, and DA Metabolites

Experiment 1B was conducted to establish Na+ channel dependence of ES-evoked DA overflow, DA metabolites and concomitant ESRB. After stable extracellular DA levels (20-min samples) were established, unilateral ES was applied at 300 μA, for 10 sec every 2 min during a 10-min time bin. ESRB was recorded during ES only. Post ES, two 10-min samples were collected to reestablish baseline. Next all animals received a 4% lidocaine microinfusion as described in Experiment 1A; except that the infusion cannula was inserted 8.4 mm below dura surface through the previously implanted guide cannula, targeting the MFB. Three 10-min samples were collected thereafter to establish a steady-state baseline under lidocaine conditions. ES was applied as previously described and ESRB was counted. Subsequently, two 10-min post ES samples were collected to re-establish baseline. To serve as a positive control, 1.5 mg/kg/ml of amphetamine was administered intraperitoneally to verify the animal preparation was viable by evoking high levels of DA overflow (data not shown). One 20-min sample was collected immediately thereafter. Dialysate samples from all microdialysis experiments were quantified using HPLC/EC based on standards injected into the system.

2.4. Experiment 2: Current-Specific Activation

2.4.1. Experiment 2A: ES-evoked Intensity-Dependent DA Overflow and ESRB

Experiment 2A was conducted to establish intensity dependence of ES-evoked DA overflow and concomitant ESRB. After baseline dialysate was established, unilateral ES was applied in a 2-point stimulation manner randomly applied at either 150 or 300 μA (50 Hz, 0.1 ms pulse duration, 10 sec train duration, and 120 sec ISI) for 10 sec every 2 min during a 10-min time bin and ESRB was recorded.

2.4.2. Experiment 2B: ES-evoked Frequency-Dependent DA Overflow and ESRB

Experiment 2B was conducted to establish frequency dependence of ES-evoked DA overflow and concomitant ESRB. After baseline dialysate was established, unilateral ES was applied in a 2-point stimulation manner randomly applied at either 25 or 50 Hz (300 μA, 0.1 ms pulse duration, 10 sec train duration, and 120 sec ISI) for 10 sec every 2 min during a 10-min time bin and ESRB was recorded.

2.5. Experiment 3: Ca++ Dependence of Electrically Evoked DA and ESRB

Experiment 3 was conducted to establish Ca++ dependence of ES-evoked DA overflow and concomitant ESRB. Rats from Experiment 2 that showed an intensity or frequency driven increase in DA or ESRB were used in Experiment 3 on the same test day. After baseline dialysate was established, unilateral ES was applied using the same parameters as Experiment 1. ESRB was recorded during ES only. Next, a modified Ca++-free Ringer’s solution containing 13.5 mM of the calcium chelator EGTA (Sigma Chemical Co.), and 33.5 mM of MgCl2 to maintain osmolarity was substituted for normal Ringer’s solution. This modified Ringers solution was infused for the duration of the experiment. Two 10-min samples were collected to allow EGTA efflux to stabilize through the microdialysis probe. Next, ES (using the same parameters under control conditions) was applied in the presence of EGTA and a 10-min dialysate sample was collected during this time.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Prism™ (GraphPad software v6). In Experiment 1A, analyses included a Pearson correlation coefficient and a two-way mixed ANOVA. In Experiment 1B, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to test for differences before and after lidocaine treatment. The Geisser-Greenhouse correction was used when sphericity was violated (i.e., epsilon < 1.0). Post hoc analyses included planned t tests, Sidak (Abdi, 2007), and Tukey pairwise comparisons. Student T tests were used for Experiments 2 and 3. The critical value was set to p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Histological Results

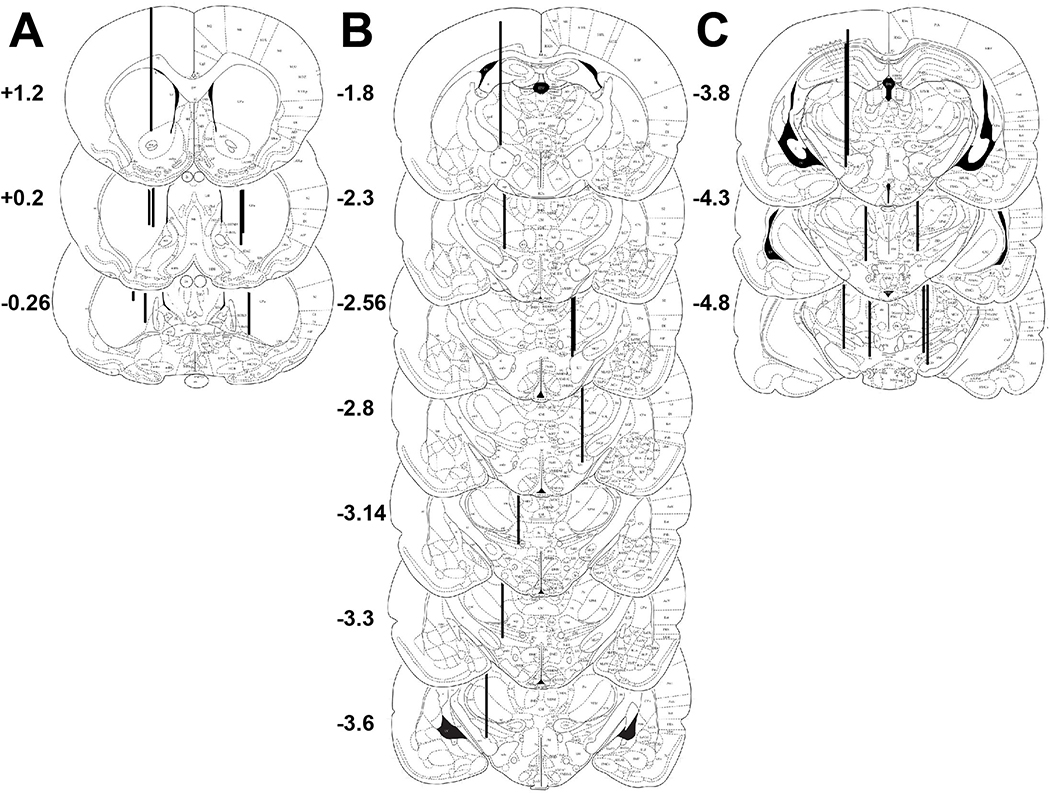

Figure 3 illustrates successful stereotaxic placement of implants in Experiment 1B. Similarly, animals that were included in all other experiments showed similar accurate placements. When this was not the case, rats were culled from all analyses.

Figure 3.

Histological Verification of Accurately Placed Microdialysis Probes, Cannulae and Electrode Implants. Schematics along the coronal plane, mm AP to bregma (Paxinos & Watson, 2006), illustrate successful placement of A) dialysis probes, B) infusion cannulae, and C) electrodes, in 8 out of 9 animals from experiment 1B. Animals with inaccurate placements were excluded from the study and not depicted in this figure.

3.2. Experiment 1: Na+ Channel Dependence

3.2.1. Experiment 1A: The Linear Relationship of Electrically-Stimulated Rotational Behavior (ESRB) with Increasing Intensity of Electrical Stimulation (ES) and Na+ Channel Dependence

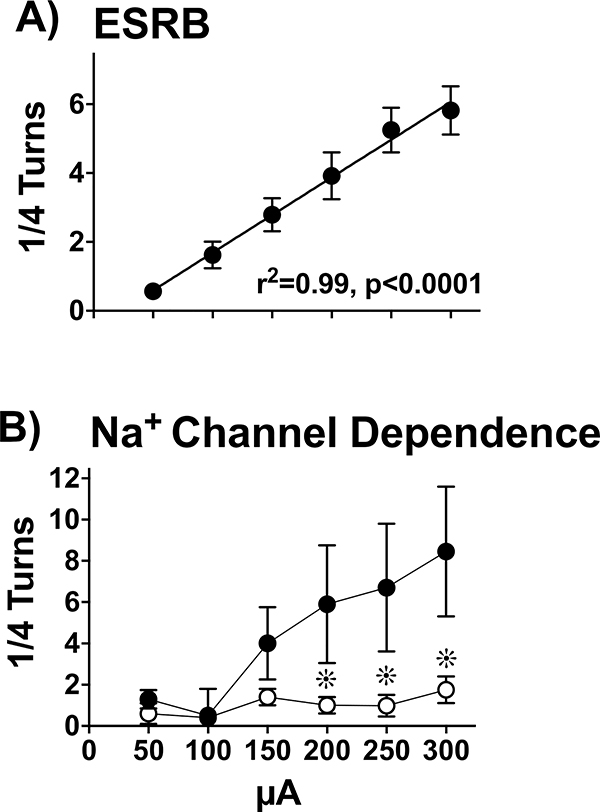

Experiment 1A explored the hypothesis that there is a positive linear increase in ESRB as a function of increasing intensity that depends on sodium channels. In Figure 4A, a Pearson correlation coefficient revealed a significant positive linear relationship between ESRB and intensity (r2 = 0.99, p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

The Linear Relationship of ESRB with Increasing Intensity of ES and Na+ Channel Dependence. A) ESRB was measured in quarter turns evoked by increasing intensity (10-sec trains, 2-min ISI) and averaged across five days (± SEM); see Methods, a priori criterion (n=22). ESRB contraversive to the stimulated hemisphere increased as intensity was increased from 50–300 μA in 50 μA intervals (r2 = 0.99, p < 0.0001). B) Similar to Figure 4A, ESRB (Mean ± SEM); was measured following infusions of 6 μl of saline (●, n=11) or 4% lidocaine (○, n=11). Na+ channel blockade significantly decreased ESRB at 200, 250 and 300 μAs (∗, p’s< 0.05) compared to saline control.

Figure 4B illustrates ESRB across increasing intensities after microinfusion of saline or lidocaine. A 2-way (saline, 4% lidocaine) between subjects ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between treatments (F5,100 = 9.91, p < 0.01). Planned T tests demonstrated that, compared to saline, lidocaine significantly attenuated ESRB across increasing intensities at 200 (T20= 4.16, p < 0.01), 250 (T20= 3.81, p < 0.01), and 300 μA (T20= 4.96, p < 0. 01).

3.2.2. Experiment 1B: Na+ Channel Dependence of Electrically Evoked DA, ESRB, and DA Metabolites

Experiment 1B explored the hypothesis that electrically evoked DA, ESRB, and DA metabolites are attenuated by Na+ channel blockade. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted for the 3 baseline samples of dialysate DA collected before ES (data not shown). There was no change across time for both conditions, before lidocaine (F1.59, 12.72 = 0.30, p > 0.05) or after lidocaine microinfusion (F1.33, 10.61 = 0.08, p > 0.05). Therefore, the average of these baseline samples was used in subsequent analyses.

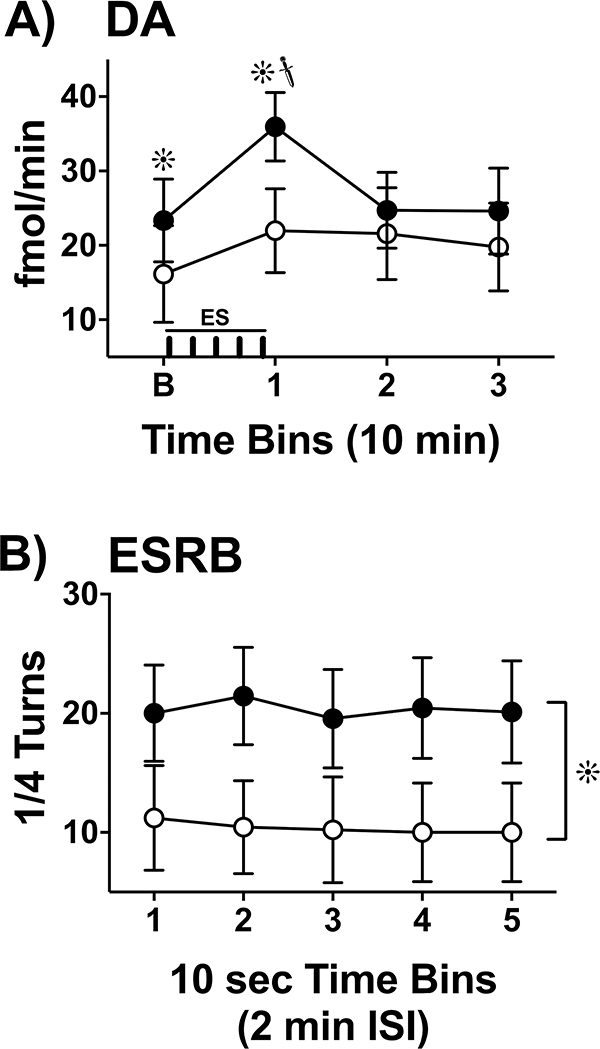

Figure 5A illustrates DA levels within the time course of ES before and after lidocaine microinfusion. A 2-way (lidocaine, time) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. A significant effect of lidocaine treatment was found (F1, 8 = 17.56, p < 0.05), indicating that in general lidocaine decreased DA levels. During baseline, a post-hoc test revealed a significant decrease in DA levels in response to lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p < 0.05). During ES, there was also a significant decrease in extracellular DA levels under lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p <0.05).

Figure 5.

Na+ Channel Dependence of Electrically Evoked DA and ESRB. A) Extracellular levels of DA (fmol/min, Mean ± SEM) were collected across the following timeline (see X-axis): during baseline (B), a 10-min collection interval during which ES (|||||; 5 X 10-sec trains, 2-min ISI) was applied (1), and two additional 10-min intervals to establish a response timeline (2,3). Animals (n=9, within subjects) were tested under two treatment conditions: during control conditions (Before Lidocaine, ●) and following treatment (After Lidocaine, ○). During baseline measures (B), lidocaine decreased spontaneous levels of extracellular DA compared to control conditions (∗, p< 0.05). ES evoked a significant increase in extracellular DA from the control baseline condition ( , p< 0.05) that returned to baseline levels immediately upon termination of ES. In the lidocaine condition, there were no significant differences across time. Na+ channel blockade significantly attenuated ES-evoked extracellular DA compared to control conditions (∗, p< 0.05). B) ESRB (Mean ± SEM) was measured in quarter turns during each 10-sec train of ES applied during the 10-min dialysis interval immediately following baseline measures (see Interval 1 of X-Axis in Fig. 5A). Prior to lidocaine (●) all animals demonstrated vigorous contraversive turning in response to ES. Lidocaine (○) significantly reduced ESRB compared to control conditions (∗, p< 0.05). Note that the rate of turning was sustained across the 5 trains of ES in both conditions.

, p< 0.05) that returned to baseline levels immediately upon termination of ES. In the lidocaine condition, there were no significant differences across time. Na+ channel blockade significantly attenuated ES-evoked extracellular DA compared to control conditions (∗, p< 0.05). B) ESRB (Mean ± SEM) was measured in quarter turns during each 10-sec train of ES applied during the 10-min dialysis interval immediately following baseline measures (see Interval 1 of X-Axis in Fig. 5A). Prior to lidocaine (●) all animals demonstrated vigorous contraversive turning in response to ES. Lidocaine (○) significantly reduced ESRB compared to control conditions (∗, p< 0.05). Note that the rate of turning was sustained across the 5 trains of ES in both conditions.

A significant main effect of repeated measures across time was found (F3, 24 = 12.40, p < 0.05). A follow-up 1-way repeated measures ANOVA conducted during the control phase (before lidocaine treatment) revealed a significant change in DA across time (F2.07, 16.57 = 11.50, p < 0.05). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed a significant increase in extracellular DA levels during ES compared to all other timepoints (Tukey, p’s < 0.05). A 1-way repeated measures ANOVA for the lidocaine phase was not significant (F1.54, 12.32 = 3.01, p > 0.05). A significant interaction (lidocaine X time) was found (F3, 24 = 3.90, p < 0.05), indicating that extracellular DA levels after lidocaine were lower than controls as a function of time.

Figure 5B illustrates ESRB before and after lidocaine microinfusion. A 2-way (lidocaine, ES) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. A significant main effect of lidocaine treatment was found (F1, 8 = 7.74, p < 0.05), indicating that in general lidocaine decreased ESRB. During every ES train, post-hoc tests revealed a significant decrease in ESRB in response to lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p’s < 0.05). There was no significant main effect for ES (F4, 32 = 0.72, p > 0.05), indicating that ESRB remained consistent throughout the five ES time bins. There was no significant interaction (lidocaine X ES) found (F4, 32 = 1.16 p > 0.05).

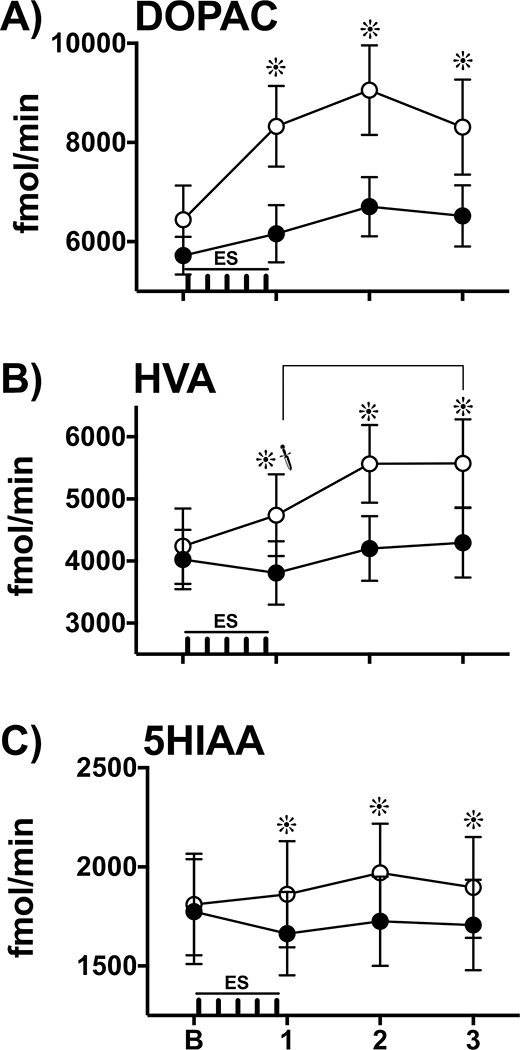

In contrast to our predicted results, Na+ channel blockade enhanced ES-evoked monoamine metabolite overflow. Figure 6A illustrates extracellular DOPAC levels across the time course of ES before and after lidocaine microinfusion. A 2-way (lidocaine, time) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. A significant effect of lidocaine treatment was found (F1,8 = 9.13, p < 0.05), indicating that in general lidocaine increased DOPAC levels. During ES, a post-hoc test revealed a significant increase in DOPAC levels in response to lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p < 0.05). During both post-ES samples, there was also a significant increase in extracellular DOPAC levels under lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p’s < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Na+ Channel Blockade Enhances ES-evoked Monoamine Metabolite Overflow. Extracellular levels of monoamine metabolites (fmol/min, Mean ± SEM) were measured during baseline (B), a 10-min collection interval during which ES (|||||; 5 X 10-sec trains, 2-min ISI) was applied (1), and two additional 10-min intervals to establish a response timeline (2,3). Animals were tested under two treatment conditions: during control conditions (Before Lidocaine, ●) and following treatment (After Lidocaine, ○). During baseline measures (B), lidocaine did not alter spontaneous levels of extracellular metabolites compared to control conditions. A) DOPAC: Regardless of treatment condition, ES increased overall DOPAC overflow (average of samples 1, 2, 3) compared to baseline levels (planned T tests, p’s ≤ 0.053; data not shown, see Results). Extracellular DOPAC levels were enhanced by lidocaine during and after ES compared to the control condition (Sidak, ∗, p’s< 0.05, pairwise comparison within each time interval). B) HVA: In the control condition, HVA levels increased significantly during the last post-ES sample (3) compared to sample 1 during which ES was applied ( , p<0.05). After lidocaine, ES increased overall HVA overflow (average of samples 1, 2, 3) compared to baseline levels (planned T test, p < 0.05; data not shown, see Results). Extracellular HVA levels were enhanced by lidocaine during and after ES compared to the control condition (Sidak, ∗, p’s< 0.05, pairwise comparison within each time interval). C) 5HIAA: In the control condition, 5HIAA levels did not change across repeated sampling. In contrast, after lidocaine, ES increased overall 5HIAA overflow (average of samples 1, 2, 3) compared to baseline levels (planned T test, p < 0.05; data not shown, see Results). These statistical analyses reveal a main effect by lidocaine and an interaction effect by lidocaine and ES to enhance extracellular 5HIAA levels compared to the control condition (Sidak, ∗, p’s< 0.05, pairwise comparison within each time interval).

, p<0.05). After lidocaine, ES increased overall HVA overflow (average of samples 1, 2, 3) compared to baseline levels (planned T test, p < 0.05; data not shown, see Results). Extracellular HVA levels were enhanced by lidocaine during and after ES compared to the control condition (Sidak, ∗, p’s< 0.05, pairwise comparison within each time interval). C) 5HIAA: In the control condition, 5HIAA levels did not change across repeated sampling. In contrast, after lidocaine, ES increased overall 5HIAA overflow (average of samples 1, 2, 3) compared to baseline levels (planned T test, p < 0.05; data not shown, see Results). These statistical analyses reveal a main effect by lidocaine and an interaction effect by lidocaine and ES to enhance extracellular 5HIAA levels compared to the control condition (Sidak, ∗, p’s< 0.05, pairwise comparison within each time interval).

A significant main effect of repeated measures was found (F3, 24 = 7.05, p < 0.05) indicating a general increase in DOPAC levels across time. Follow-up 1-way repeated measures ANOVAs for each treatment condition, before and after lidocaine, revealed no significant changes in DOPAC levels across time. There was no significant interaction (lidocaine X time) found (F3, 24 = 1.28, p > 0.05).

To explore the overall effect of ES upon DOPAC overflow (Figure 6A), a planned T-test was conducted between the averaged baseline samples and the average of the last three samples (data not shown). Before lidocaine, ES significantly increased extracellular DOPAC levels (T8= 1.83, p = 0.053). After lidocaine, ES also significantly increased extracellular DOPAC levels (T8= 1.99, p < 0.05).

Figure 6B illustrates extracellular HVA levels across the time course of ES before and after lidocaine microinfusion. A 2-way (lidocaine, time) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. A significant effect of lidocaine treatment was found (F1, 8 = 16.04, p < 0.05) indicating that in general lidocaine increased HVA levels. During ES, a post-hoc test revealed a significant increase in HVA levels in response to lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p < 0.05). During both post-ES samples, there was also a significant increase in extracellular HVA levels under lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p’s < 0.05).

A significant main effect of repeated measures was found (F3, 24 = 8.26, p < 0.05) indicating a general increase in HVA levels across time. A follow-up 1-way repeated measures ANOVA conducted during the control phase (before lidocaine treatment) revealed a significant change in HVA across time (F2.17, 17.36 = 5.12, p < 0.05). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed a significant increase in extracellular HVA levels during the last post-ES sample compared to ES (Tukey, p < 0.05). A 1-way repeated measures ANOVA conducted during the treatment phase (after lidocaine treatment) revealed a significant change in HVA across time (F1.50, 11.97 = 6.15, p < 0.05), although there were no significant differences in post-hoc pairwise comparisons. A significant interaction (lidocaine X time) was found (F3, 24 = 3.61, p < 0.05), indicating that extracellular HVA levels after lidocaine were higher than controls as a function of time.

To explore the overall effect of ES upon HVA overflow (Figure 6B), a planned T-test was conducted between the averaged baseline samples and the average of the last three samples (data not shown). Before lidocaine, ES did not alter extracellular HVA levels (T8= .57, p > 0.05). However, after lidocaine, ES significantly increased extracellular HVA levels (T8= 2.75, p < 0.05).

Figure 6C illustrates extracellular 5HIAA levels across the time course of ES before and after lidocaine microinfusion. A 2-way (lidocaine, time) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. A significant effect of lidocaine treatment was found (F1, 8 = 15.01, p < 0.05) indicating that in general lidocaine increased 5HIAA levels. During ES, a post-hoc test revealed a significant increase in 5HIAA levels in response to lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p < 0.05). During both post-ES samples, there was also a significant increase in extracellular 5HIAA levels under lidocaine treatment compared to control conditions (Sidak, p’s < 0.05). There was no significant main effect of repeated measures (F3, 24 = 1.36, p > 0.05). However, a significant interaction (lidocaine X time) was found (F3, 24 = 3.39, p < 0.05), indicating that extracellular 5HIAA levels after lidocaine were higher than controls as a function of time.

To explore the overall effect of ES upon 5HIAA overflow (Figure 6C), a planned T-test was conducted between the averaged baseline samples and the average of the last three samples (data not shown). Before lidocaine, ES did not alter extracellular 5HIAA levels (T8= 1.14, p > 0.05). However, after lidocaine, ES significantly increased extracellular 5HIAA levels (T8= 2.82, p < 0.05).

3.3. Experiment 2: Current-Specific Activation

3.3.1. Experiment 2A: ES-evoked Intensity-Dependent DA Overflow and ESRB

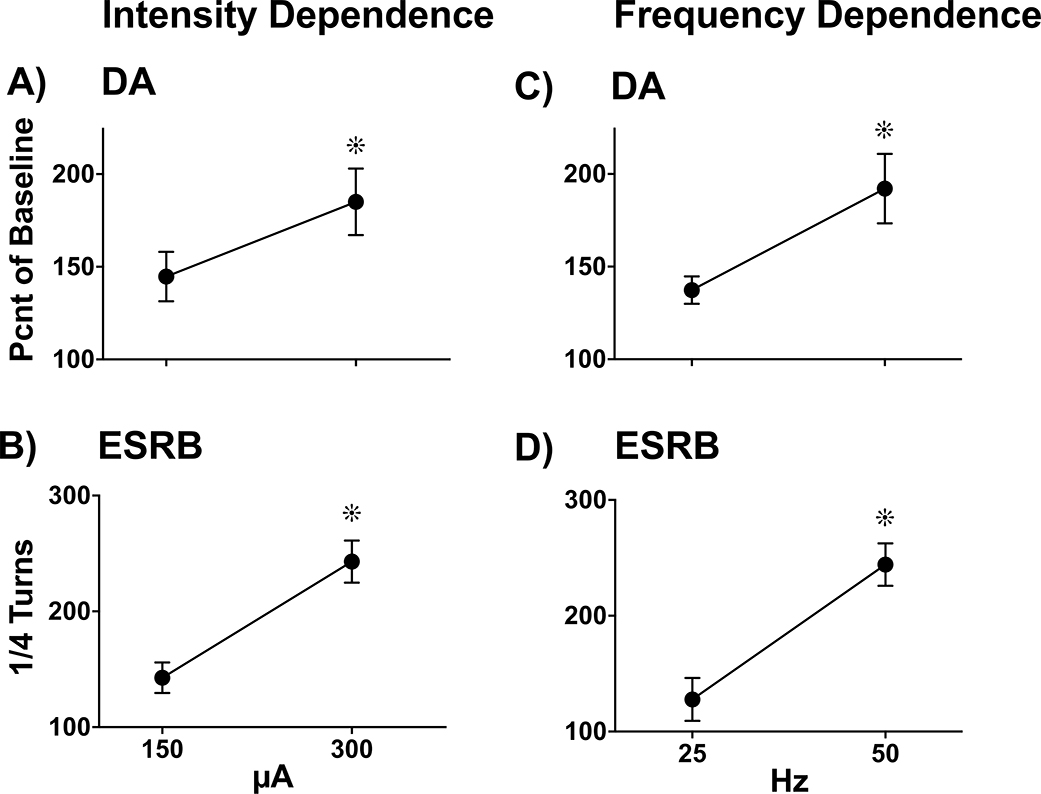

Experiment 2A explored the hypothesis that ES evokes DA overflow and ESRB that increases with increasing intensity. Figure 7A illustrates DA levels across two points of increasing intensity (150 & 300 μA) of ES parameters. A planned T-test revealed a significant increase in overall extracellular DA levels with increasing intensity. (T5= −3.43, p < 0.05). Figure 7B illustrates ESRB across the same two points of increasing intensity of ES parameters. A planned T-test revealed a significant increase in ESRB with increasing intensity (T5= 7.87, p < 0.01).

Figure 7.

ES-evoked Intensity- and Frequency-Dependent DA Overflow and ESRB. DA overflow and ESRB were simultaneously measured during two 10-min dialysis collection intervals in which ES was differentially applied (5 X 10-sec trains, 2-min ISI). Extracellular DA (Panels A, C) and ESRB (Panels B, D) were converted to percent of spontaneous baseline levels (Mean ± SEM. A & B) To assess the effects of intensity upon ES-induced DA overflow (Panel A) and ESRB (Panel B), frequency was held constant at 50 Hz and intensity was set to 150 μA and subsequently to 300 μA. There was a significant intensity-dependent increase in DA overflow and ESRB (∗, p’s < 0.05, n=6). C & D) To assess the effects of frequency upon ES-induced DA overflow (Panel C) and ESRB (Panel D), intensity was held constant at 300 μA and frequency was set to 25 Hz and subsequently to 50 Hz. There was a significant frequency-dependent increase in DA overflow and ESRB (∗, p’s < 0.05, n=6).

3.3.2. Experiment 2B: ES-evoked Frequency-Dependent DA Overflow and ESRB

Experiment 2B explored the hypothesis that ES evokes DA overflow and ESRB that increases with increasing frequency. Figure 7C illustrates DA across two points of increasing frequency (25 & 50 Hz) of ES parameters. A planned T-test revealed a significant increase in overall extracellular DA levels with increasing frequency (T5= −3.24, p < 0.05). Figure 7D illustrates ESRB across the same two points of increasing frequency of ES parameters. A planned T-test revealed a significant increase in ESRB with increasing frequency (T5= 7.80, p < 0.01).

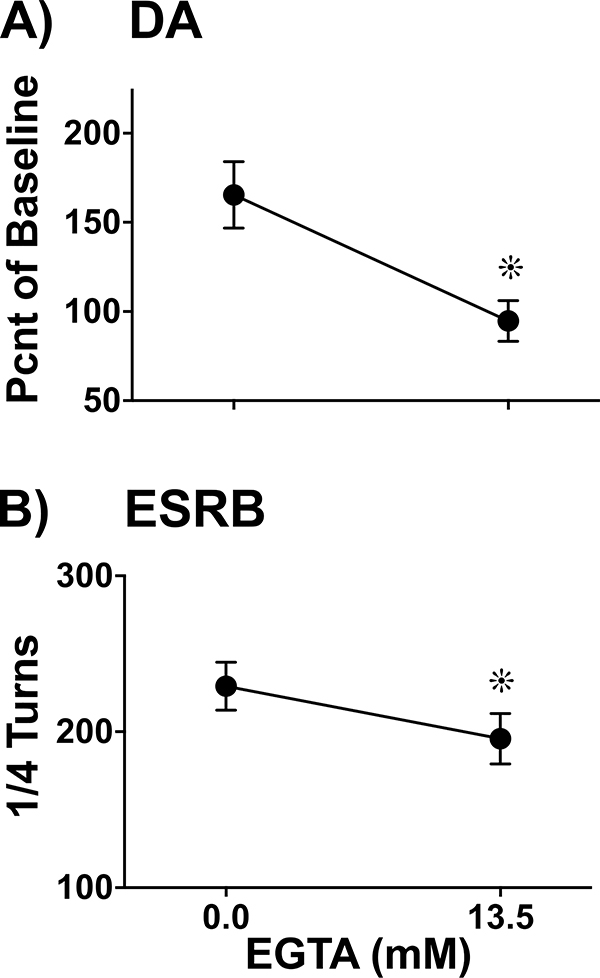

3.4. Experiment 3: Ca++ Dependence of Electrically Evoked DA and ESRB

Experiment 3 explored the hypothesis that ES-evoked DA overflow and ESRB are attenuated in the absence of Ca++ availability. Figure 8A illustrates DA levels across two time points of ES, during control conditions (0.0 mM EGTA) and treatment conditions (13.5 mM EGTA). A planned T-test revealed a significant decrease in overall extracellular DA levels after treatment with EGTA (T4= −3.03, p < 0.05). Figure 8B illustrates ESRB across the same two conditions as per Panel 7A. A planned T-test revealed a significant decrease in ESRB after treatment with EGTA (T4= 8.53, p < 0.01).

Figure 8.

Ca++ Dependence of Electrically Evoked DA and ESRB. DA overflow and ESRB were simultaneously measured during two 10-min dialysis collection intervals in which ES was applied (5 X 10-sec trains, 2-min ISI). Extracellular DA (A) and ESRB (B) were converted to percent of spontaneous baseline levels (Mean ± SEM). A) To test for Ca++ dependence of ES-evoked DA, ES was applied during control conditions (0.0 mM EGTA) and again with 13.5 mM EGTA. There was a significant decrease in DA overflow after Ca++ availability was depleted (∗,.p < 0.05, n=5). B) To test for Ca++ dependence of ESRB, ES was applied during control conditions (0.0 mM EGTA) and again with 13.5 mM EGTA. There was a significant decrease in ESRB after Ca++ availability was depleted (∗,.p < 0.05, n=5).

4. Discussion

The present results show that electrical stimulation (ES) produces frequency- and intensity-dependent electrically-stimulated rotational behavior (ESRB) and DA overflow that is sensitive to Na+ channel blockade and Ca++ availability. Therefore, in the present paradigm, ES activates exocytotic-like DA overflow and a closely linked behavior that conforms to criteria required to establish a physiologically meaningful relationship.

It is well accepted that ES in vitro produces depolarization to activate Na+ channel-dependent action potentials, subsequently producing exocytosis (Mulder et al., 1983). Consistent with this, results from Experiment 1A revealed that in vivo ES of the MFB induced intensity-dependent rotational behavior are dependent upon Na+ channels. Furthermore, Experiment 1B revealed that both ES-induced DA release and rotational behavior are attenuated in the presence of Na+ channel blockade. Ultimately, these data support the idea that in vivo ES leads to neuronal depolarization by triggering action potentials that activate voltage-gated Na+ channels in vivo.

Na+ channel blockade by lidocaine alone did not alter resting state extracellular levels of DOPAC, HVA and 5HIAA. DOPAC levels were mildly elevated with ES alone but HVA and 5HIAA levels did not change. Na+ channel blockade together with and after ES significantly enhanced extracellular metabolite levels. At first glance, this result is counterintuitive because lidocaine blocked ES-evoked DA overflow and it would be expected that turnover would be downregulated to decrease metabolite output, yet we report increased DOPAC, HVA and 5HIAA in the presence of ES and lidocaine. Perhaps the finding that lidocaine increases metabolite levels is reflective of lidocaine induced increases in tonic DA levels found by Sircuta et al. (2016). However, in the present study lidocaine treatment decreased resting state DA levels for 30 min (across three serial 10-min baseline samples) before ES was applied. Sircuta et al. (2016) used an in vitro superfusion method to bathe lidocaine over isolated fragments of caudate nucleus, comprised essentially of DAergic terminal boutons. Our in vivo experimental preparation was designed to test whether ES evokes depolarizing signals, from axons as they project away from the substantia nigra, by infusing lidocaine aimed at the lateral hypothalamic MFB axonal projections to block evoked exocytotic-like DA release at the distal end terminals within the caudate nucleus. Thus, these different outcomes might be explained by methodological differences.

It is also possible that increases in DA metabolites could simply be due to an order effect given animals received two bouts of ES. Subjects first underwent ES for DA release under normal control conditions, followed by ES again after lidocaine treatment. Thus, observed increases in DA metabolites following lidocaine may reflect DA turnover produced by repeated ES. It has been long noted that indexes of metabolites alone are inadequate markers of neurotransmission. It has long been established that pharmacological interventions can alter metabolic rates distinct from neurotransmission (Commissiong, 1985). Therefore, the dynamic equilibrium that exists between synthesis-vesicular storage-release-reuptake-degradation can be disrupted to alter the balance of neurotransmitter/metabolite ratios that does not reflect an increase in utilization. For example, in the present results, the combination of ES and Na+ channel blockade may have increased DA biosynthesis (Murrin et al., 1976) and/or metabolism (Miu et al 1992), subsequently leading to an enhanced accumulation of metabolites as compared to ES in the absence of lidocaine. More research is needed to understand the specific mechanisms involved in the increases of extracellular DOPAC and HVA that are observed in this report. Similar effects may occur with serotonin, given that 5-HIAA shows the same pattern as the DA metabolites. It is clear that evaluating the dynamics of metabolite levels simultaneously with measures of DA and behavior may be prudent to enhance interpretability of future studies.

Finally, it is important to discern significant differences between the parameters for electrical stimulation used in the present methodology and high frequency stimulation (HFS) used to treat Parkinson’s disease. HFS is utilized to dissociate input and output signals to disrupt abnormal information flow through the stimulation site (Nambu & Chiken, 2015), such as to mitigate excessive output from the subthalamic nucleus (Benabid et al., 1994). Animal studies utilizing IVMCD in combination with HFS of the subthalamic nucleus have reported downstream decreases in serotonin release from neostriatum and medial prefrontal cortex (Tan et al., 2012). The goal of the present parametric study was to validate that ES using the parameters in this report activate DA neurons in an exocytotic-like manner and that mediates a highly correlated behavioral response (rxy = 0.99, see Figure 2). HFS utilizes intensities and pulse durations similar to our parameters but delivers frequencies that are approximately three times higher and continuously for a prolonged time in contrast to the present study. Applying our parameters continuously for 10–20 min resulted in decreased DA levels and a cessation of rotational behavior (data not shown). To avoid this “fatigue,” we found that the optimal conditions to evoke the neurochemical and behavioral responses sought was to deliver 10 sec trains with intertrain intervals of 2 min across 10 min.

In conclusion, results from Experiment 2 revealed that both ES-induced DA and rotational behavior are frequency- and intensity-dependent. Moreover, Experiment 3 revealed that both ES-induced DA and rotational behavior are attenuated when Ca++ availability is reduced. These types of manipulations are historically believed to reflect activation of physiologically relevant mechanisms of exocytosis in contrast to pharmacological manipulations that induce atypical neurotransmitter overflow.

Taken together, the data from these parametric studies support that ES in vivo mimics the depolarization of the membrane produced by an action potential. In response, voltage-dependent Ca++ channels are activated, leading to vesicular-based DA release into the synapse. The significant contribution of the methodology developed in this research is the ability to correlate changes in exocytotic-like DA release with a simultaneously evoked behavioral response.

ES is an excellent choice to study presynaptic mechanisms of DA release with simultaneously evoked behavior, but an inherent limitation is the nonspecific activation of multiple neuronal populations. The present methodology combining ES with in vivo intracerebral microdialysis (IVMCD) provides innovative opportunities to assess empirical questions and further complement current genetic techniques (e.g., optogenetics, DREADDs) to assure isolation of targeted neural circuits (Parrot et al., 2015).

5. Conclusions

Historically, research utilizing IVMCD has been restricted to pharmacological manipulations, but the innovative methodology described herein combines IVMCD with ES to achieve more precise control of presynaptic modulators of exocytosis. Ultimately, this novel approach can achieve more neurologically relevant insights about plasticity of DA neurotransmission. For example, in models of substance abuse disorder there is an enhancement of DA release in response to neutral stimuli paired with cocaine (Duvauchelle et al., 2000). These DA fluxes in response to conditioned stimuli are thought to reflect craving and incentive motivational states (Volkow et al., 2006; Cox et al., 2017). Likewise, the positive symptoms of schizophrenia are largely attributed to DA overactivity (Reith et al., 1994; Abi-Dargham et al., 2000), and in Parkinson’s disease there appears to be a compensatory response to preserve normal extracellular DA levels (Castañeda et al., 1990; Nandhagopal et al., 2011). The neuronal mechanisms by which these alterations in the efflux of DA remain elusive. Thus, there is a dire need to further clarify mechanistic alterations in exocytotic release in these disease states, because observed changes in extracellular DA levels is only phenomenological. This research method contributes a refinement in the use of ES and IVMCD by which the combination of these techniques provides the opportunity to assess exocytotic alterations in rodent models studying neurotransmission simultaneously with relevant changes in behavior.

Research highlights.

Simultaneous electrical stimulation with microdialysis is a feasible technique.

Evoked dopamine release and rotational behavior are intensity dependent.

Evoked dopamine release and rotational behavior are frequency dependent.

Evoked dopamine release and rotational behavior are sodium channel dependent.

Evoked dopamine release and rotational behavior are calcium dependent.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from The Vulnerability Issues in Drug Abuse training grant (NIDA R24-DA029929), the Arizona Institute for Mental Health Research (Phoenix, AZ), the Arizona State University Hispanic Research Center, the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (NSF HRD-1301858), and Research Initiatives for Scientific Enhancement (NIGMS R25-GM069621-11). We thank Steve Austin for his technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- (ES)

Electrical Stimulation

- (IVMCD)

In Vivo Intracerebral Microdialysis

- (DA)

Dopamine

- (MFB)

Medial forebrain bundle

- (ESRB)

Electrically-stimulated rotational behavior

- (Cd/P)

Caudate/putamen

- (DOPAC)

3,4-dihydroxyphenyl acetic acid

- (HVA)

Homovanillic acid

- (5-HIAA)

5-hydroxyindoleacetic

- (EGTA)

Ethyleneglyco-bis 2 amino-ethylether-N,N,N,N-tetra acetic acid

- (HFS)

High frequency stimulation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdi H (2007). The Bonferonni and Šidák corrections for multiple comparisons In Salkind NJ (Ed.), Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics (pp.103–107). Sage; 10.4135/9781412952644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abercrombie ED, & Zigmond MJ (1989). Partial injury to central noradrenergic neurons: reduction of tissue norepinephrine content is greater than reduction of extracellular norepinephrine measured by microdialysis. The Journal of Neuroscience, 9(11), 4062–4067. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-11-04062.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, Zea-Ponce Y, Gil R, Kegeles LS, … & Gorman JM (2000). Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(14), 8104–8109. 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi YU, Satomoto M, Higuchi H, Watanabe K, Yamada S, & Kazama T (2005). Halothane enhances dopamine metabolism at presynaptic sites in a calcium-independent manner in rat striatum. British Journal of Anesthesia, 95(4), 485–494. 10.1093/bja/aei213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass CE, Grinevich VP, Vance ZB, Sullivan RP, Bonin KD, & Budygin EA (2010). Optogenetic control of striatal dopamine release in rats. Journal of Neurochemistry, 114(5), 1344–1352. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06850.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benabid AL, Pollak P, Gross C, Hoffmann D, Benazzouz A, Gao DM, Laurent A, Gentil M, & Perret J (1994) Acute and long-term effects of subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg, 62, 76–84. 10.1159/000098600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste H, Hansen AJ, & Ottosen NS (1989) Determination of brain interstitial concentrations by microdialysis. Journal of Neurochemistry, 52, 1741–1750. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07252.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste H, & Hüttemeier PC (1990). Microdialysis—theory and application. Progress in Neurobiology, 35(3), 195–215. 10.1016/0301-0082(90)90027-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, & Valenstein ES (1991). What psychological process mediates feeding evoked by electrical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus? Behavioral Neuroscience, 105(1), 3 10.1037/0735-7044.105.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracha V, Stewart SL, & Bloedel JR (1993). The temporary inactivation of the red nucleus affects performance of both conditioned and unconditioned nictitating membrane responses in the rabbit. Experimental Brain Research, 94(2), 225–236. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF00230290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova JP, Velis GP, & Fuentealba JA (2013). Amphetamine locomotor sensitization is accompanied with an enhanced high K stimulated DA release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Behavioral Brain Research, 237, 313–317. 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda E, Robinson TE, & Becker JB (1985). Involvement of nigrostriatal DA neurons in the contraversive rotational behavior evoked by electrical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus. Brain Research, 327(1), 143–151. 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91508-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda E, Whishaw IQ, & Robinson TE (1990). Changes in striatal DA neurotransmission assessed with microdialysis following recovery from a bilateral 6-OHDA lesion: variation as a function of lesion size. The Journal of Neuroscience, 10(6), 1847–1854. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-01847.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commissiong JW (1984). Synthesis of catecholamines in the developing spinal cord of the rat. Journal of Neurochemistry, 42(6), 1574–1581. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb12744.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commissiong JW (1985). Monoamine metabolites: their relationship and lack of relationship to monoaminergic neuronal activity. Biochemical Pharmacology, 34(8), 1127–1131. 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90484-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JR, & Roth RH (2003). The biochemical basis of neuropharmacology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cox SM, Yau Y, Larcher K, Durand F, Kolivakis T, Delaney JS, … & Leyton M (2017). Cocaine cue-induced dopamine release in recreational cocaine users. Scientific Reports, 7, 46665 10.1038/srep46665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfs JM, Zhu Y, Druhan JP, & Aston-Jones GS (1998). Origin of noradrenergic afferents to the shell subregion of the nucleus accumbens: anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing studies in the rat. Brain Research, 806(2), 127–140. 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00672-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K (2011). Optogenetics. Nature Methods, 8(1), 26–29. 10.1038/nmeth.f.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvauchelle CL, Ikegami A, & Castaneda E (2000). Conditioned increases in behavioral activity and accumbens dopamine levels produced by intravenous cocaine. Behavioral Neuroscience, 114(6), 1156 10.1037/0735-7044.114.6.1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essman WD, McGonigle P, & Lucki I (1993). Anatomical differentiation within the nucleus accumbens of the locomotor stimulatory actions of selective DA agonists and d-amphetamine. Psychopharmacology, 112(2), 233–241. 10.1007/BF02244916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JF, & Cho AK (1979). Chemical release of DA from striatal homogenates: evidence for an exchange diffusion model. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 208(2), 203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A, Lax E, Dikshtein Y, Abraham L, Flaumenhaft Y, Sudai E, Ben-Tzion M, Yadid G (2011) Electrical stimulation of the lateral habenula produces an inhibitory effect on sucrose self-administration. Neuropharmacology, 60, 381–387. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch G, & Hitzig E (1870). Electric excitability of the cerebrum (Über die elektrische Erregbarkeit des Grosshirns). Epilepsy & Behavior, 15(2), 123–130, 2009. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, & Huxley AF (1952). A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. The Journal of Physiology, 117(4), 500–544. 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebel BG, & Teitelbaum P (1962). Hypothalamic control of feeding and self-stimulation. Science, 135(3501), 375–377. 10.1126/science.135.3501.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, & Goeders NE (1998). Microinjections of dopamine agonists and cocaine elevate plasma corticosterone: dissociation effects among the ventral and dorsal striatum and medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Research, 814(1), 171–178. 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01070-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo-Serra M, Trauner D, Llobet A, & Gorostiza P (2013). Optical control of calcium-regulated exocytosis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects, 1830(3), 2853–2860. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, & Miledi R (1965). The effect of calcium on acetylcholine release from motor nerve terminals. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 161(985), 496–503. 10.1098/rspb.1965.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlig KM, Binda F, Khoshbouei H, Blakely RD, McMahon DG, Javitch JA, & Galli A (2005). Amphetamine induces dopamine efflux through a dopamine transporter channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(9), 3495–3500. 10.1073/pnas.0407737102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug K, Salzman CD, & Waddell S (2015). Understanding the brain by controlling neural activity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 370(1677), 20140201 10.1098/rstb.2014.0201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi G, & Raiteri M (1993). Carrier-mediated release of neurotransmitters. Trends in Neurosciences, 16(10), 415–419. 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90010-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R and Heuser J (1977) Depolarization-release coupling systems in neurons. Neurosciences Research Program Bulletin 15:557–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Steinberg IZ, & Walton K (1981). Presynaptic calcium currents in squid giant synapse. Biophysical Journal, 33(3), 289 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84898-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindefors N, Brodin E, Tossman U, Segovia J, & Ungerstedt U (1989). Tissue levels and in vivo release of tachykinins and GABA in striatum and substantia nigra of rat brain after unilateral striatal DA denervation. Experimental Brain Research, 74(3), 527–534. 10.1007/BF00247354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH (1991). Autoradiographic estimation of the extent of reversible inactivation produced by microinjection of lidocaine and muscimol in the rat. Neuroscience Letters, 127(2), 160–164. 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90784-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AC, & Bardo MT (2015). Amphetamine self-administration and dopamine function: assessment of gene×environment interactions in Lewis and Fischer 344 rats. Psychopharmacology, 232(13), 2275–2285. 10.1007/s00213-014-3854-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MM & Quirk GJ (2002) Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature, 420, 70–74. 10.1038/nature01138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner JD, & Wurtman RJ (1984). Release of endogenous dopamine from electrically stimulated slices of rat striatum. Brain research, 301(1), 139–142. 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90410-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miu P, Karoum F, Toffano G, & Commissiong JW (1992). Regulatory aspects of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Experimental Brain Research, 91(3), 489–495. 10.1007/BF00227845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder AH, van Amsterdam RG, Wilbrink M, & Schoffelmeer AN (1983). Depolarization-induced release of histamine by high potassium concentrations, electrical stimulation and veratrine from rat brain slices after incubation with the radiolabelled amine. Neurochemistry International, 5(3), 291–297. 10.1016/0197-0186(83)90031-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mura A, Feldon J, & Mintz M (1998). Reevaluation of the striatal role in the expression of turning behavior in the rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Research, 808(1), 48–55. 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00791-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrin LC, Morgenroth VH, & Roth RH (1976). Dopaminergic neurons: effects of electrical stimulation on tyrosine hydroxylase. Molecular Pharmacology, 12(6), 1070–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu A, & Chiken S (2015). Mechanism of DBS: inhibition, excitation, or disruption? In Itakura T (Ed.) Deep brain stimulation for neurological disorders. Springer, Cham: 10.1007/978-3-319-08476-3-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nandhagopal R, Kuramoto L, Schulzer M, Mak E, Cragg J, McKenzie J, … & Stoessl AJ (2011). Longitudinal evolution of compensatory changes in striatal dopamine processing in Parkinson’s disease. Brain, 134(11), 3290–3298. 10.1093/brain/awr233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds J, & Milner P (1954). Positive reinforcement produced by electrical stimulation of septal area and other regions of rat brain. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 47(6), 419 10.1037/h0058775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker EM, & Cubeddu LX (1986). Effects of d-amphetamine and DA synthesis inhibitors on DA and acetylcholine neurotransmission in the striatum. I. Release in the absence of vesicular transmitter stores. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 237(1), 179–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrot S, Denoroy L, Renaud B, & Benetollo C (2015). Why optogenetics needs in vivo neurochemistry. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 6(7), 948–950. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, & Watson C (2006). The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Access Online via Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolino M (1997). Luigi Galvani and animal electricity: two centuries after the foundation of electrophysiology. Trends in Neurosciences, 20(10), 443–448. 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01101-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, & Boldrey E (1937). Somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 10.1093/brain/60.4.389 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Jasper H. Epilepsy and the functional anatomy of the human brain. London: J. & Churchill A; 1954. 10.1212/WNL.4.6.483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pycock CJ (1980). Turning behaviour in animals. Neuroscience, 5(3), 461–514. 10.1016/B978-0-08-025501-9.50029-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiteri M, Cerrito F, Cervoni AM, & Levi G (1979). DA can be released by two mechanisms differentially affected by the DA transport inhibitor nomifensine. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 208(2), 195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith J, Benkelfat C, Sherwin A, Yasuhara Y, Kuwabara H, Andermann F, … & Dyve SE (1994). Elevated dopa decarboxylase activity in living brain of patients with psychosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 91(24), 11651–11654. 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JNJ, & Wickens JR (2000). Substantia nigra dopamine regulates synaptic plasticity and membrane potential fluctuations in the rat neostriatum, in vivo. Neuroscience, 99(2), 199–203. 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00273-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Noordhoorn M, Chan EM, Mocsary Z, Camp DM, & Whishaw IQ (1994). Relationship between asymmetries in striatal DA release and the direction of amphetamine-induced rotation during the first week following a unilateral 6-OHDA lesion of the substantia nigra. Synapse, 17(1), 16–25. 10.1002/syn.890170103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, & Whishaw IQ (1988). Normalization of extracellular DA in striatum following recovery from a partial unilateral 6-OHDA lesion of the substantia nigra: a microdialysis study in freely moving rats. Brain Research, 450(1), 209–224. 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91560-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söllner T, Whiteheart SW, Brunner M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Geromanos S, Tempst P, & Rothman JE (1993). SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature, (362), 318–24. 10.1038/362318a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PM, Rozanski G, Ferguson AV (2010) Acute electrical stimulation of the subfornical organ includes feeding in satiated rats. Physiology & Behavior, 99(4), 534–537. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sircuta C, Lazar A, Azamfirei L, Baranyi M, Vizi ES, & Borbély Z (2016). Correlation between the increased release of catecholamines evoked by local anesthetics and their analgesic and adverse effects: Role of K+ channel inhibition. Brain Research Bulletin, 124, 21–26. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachowiak MK, Keller RW Jr, Stricker EM, & Zigmond MJ (1987). Increased DA efflux from striatal slices during development and after nigrostriatal bundle damage. The Journal of Neuroscience, 7(6), 1648–1654. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-06-01648.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford JA, Giardina K, & Gerhardt GA (2000). In vivo microdialysis studies of age-related alterations in potassium-evoked overflow of DA in the dorsal striatum of Fischer 344 rats. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 18(4), 411–416. 10.1016/S0736-5748(00)00009-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A (2005) Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: A Review. Progress in Neurobiology, 75(6), 406–433. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SK, Hartung H, Visser-Vandewalle V, Steinbusch HW, Temel Y, & Sharp T. (2012) A combined in vivo neurochemical and electrophysiological analysis of the effect of high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus on 5-HT transmission. Experimental Neurology, 233(1):145–153. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton JM, Gerhardt GA, Friedemann M, Etgen AM, Rose GM, Sharpless NS, Gardner EL (1988) The effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol on potassium-evoked release of dopamine in the rat caudate nucleus: an in vivo electrochemical and in vivo microdialysis study. Brain Research, 451(1), 59–68. 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90749-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Nguyen LT, Castañeda E, & MacBeth T (1996). Changes in behavior and monoamine levels in microdialysate from dorsal striatum after 6-OHDA infusions into ventral striatum. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 55(1), 141–150. 10.1016/0091-3057(96)00068-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein ES, Cox VC, & Kakolewski JW (1970). Reexamination of the role of the hypothalamus in motivation. Psychological Review, 77(1), 16 10.1037/h0028581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, … & Wong C (2006). Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. Journal of Neuroscience, 26(24), 6583–6588. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1544-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan RQ, Giovanni A, Kafka SH, & Corbett R (1996). Neonatal hippocampal lesions induced hyperresponsiveness to amphetamine: behavioral and in vivo microdialysis studies. Behavioural Brain Research, 78(2), 211–223. 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00251-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey CN, Erickson TC, & Gilson WE (1979). Localization in somatic sensory and motor areas of human cerebral cortex as determined by direct recording of evoked potentials and electrical stimulation. Journal of Neurosurgery, 51(4), 476–506. 10.3171/jns.1979.51.4.0476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]