Abstract

Objective:

The Zika Contraception Access Network (Z-CAN) was a short-term emergency response intervention that used contraception to prevent unintended pregnancy to reduce Zika-related adverse birth outcomes during the 2016 2017 Zika virus outbreak in Puerto Rico. Strategies and safeguards were developed to ensure women who chose long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) had access to no-cost removal, if desired, after Z-CAN ended.

Study Design:

We assessed the number of women who chose LARC at their initial Z-CAN visit who filed complaints regarding challenges with LARC removal within 30-months after the Z-CAN program ended. Complaints and program responses were categorized.

Results:

Of the 29,221 women who received Z-CAN services, 20,381 chose a LARC method at their initial visit (IUD = 12,276 and implant = 8105). Between September 2017 and February 2020, 63 patient complaints were logged, mostly due to LARC removal charges (76.2%) which were generally (71.4%) determined to be inappropriate charges. All complaints filed were resolved allowing LARC removal within an average of 28 days.

Conclusion:

Safeguards to ensure prompt LARC removal when desired are critical to ensure women s reproductive autonomy.

Implications:

Strategies and safeguards used by Z-CAN to ensure women have access to LARC removal might be used by other contraception programs to prevent reproductive coercion and promote reproductive autonomy to best meet the reproductive needs of women.

Keywords: Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), LARC removal, Reproductive autonomy, Zika, Emergency response

1. Introduction

The National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Foundation), with technical assistance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), established the Zika Contraception Access Network (Z-CAN), a short-term emergency response intervention that used contraception to prevent unintended pregnancy to reduce Zika-related adverse birth outcomes during the Zika outbreak [1–4].

Reproductive autonomy, or the ability to decide and control contraceptive use, pregnancy, and childbearing, was a fundamental principle that informed Z-CAN, given Puerto Rico s history of coerced sterilization and unethical testing of oral contraceptives [5–10]. Increasing access to the full range of reversible contraceptive methods expands contraceptive options for women [6,11,12] and allows them to choose a method that best meets their needs. To ensure reproductive autonomy, it is critical women can discontinue their LARC method at any time. Barriers to removal may inhibit use of LARC if women lack assurance that removal will be an option or if they perceive resistance from providers when they raise the possibility of removal [13].

As previously reported, Z-CAN incorporated ethical considerations and best practices for contraception service delivery including offering women the full range of reversible contraceptive options at no cost and access to prompt no-cost long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) (intrauterine device (IUD) and implant) removal services when desired [2,14]. To ensure that LARC users who participated in Z-CAN would have access to no-cost LARC removal, a safety net was established that will operate for 10 years after the program ended.

From May 2016 to September 2017, 29,221 women received Z-CAN services; 70% (n = 20,381) chose a LARC (46% levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, 15% copper IUD, and 40% implant); 23% chose injectables, pills, patch, ring; 3% chose condoms only; and 4% chose no method at the initial visit [14]. While the program was active, 4% (n = 719) of women who chose a LARC at the initial visit had it removed; data on LARC removal are limited post program [14].

This report describes safety net components and patient complaints regarding challenges with LARC removal within 30-months after the program ended.

2. Material and methods

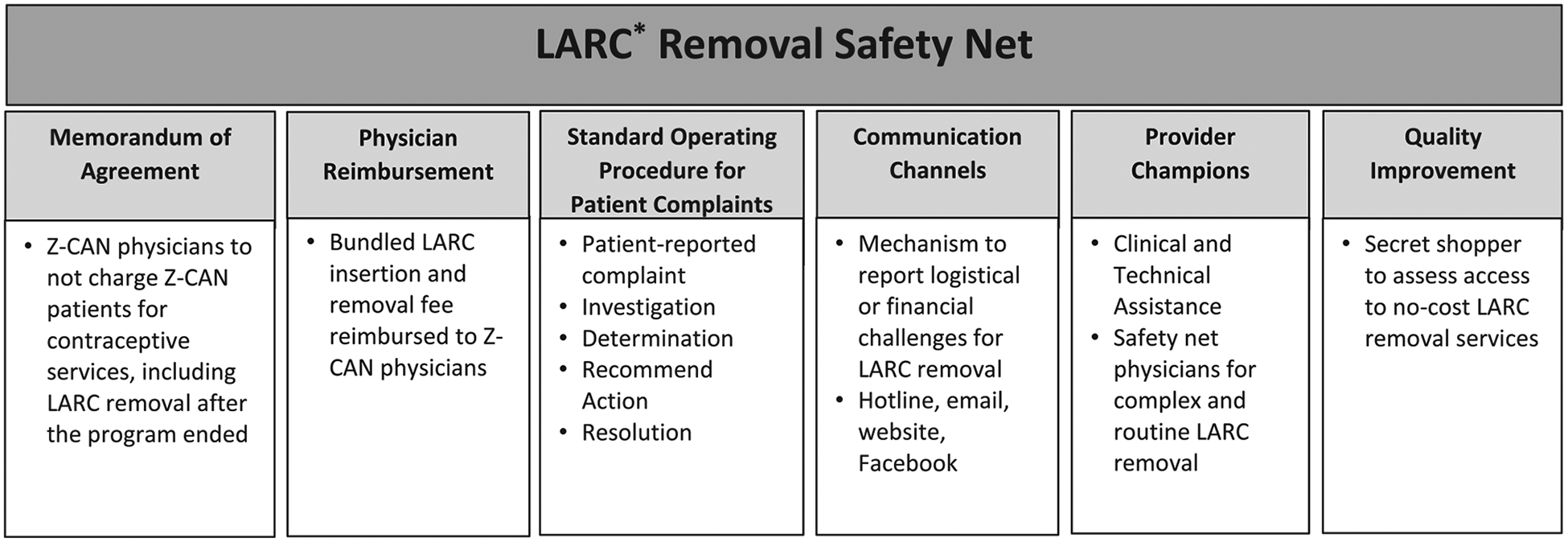

A multi-component safety net (Fig. 1) was developed to address potential challenges with LARC removal. The CDC Foundation secured a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with each participating Z-CAN physician to not charge Z-CAN patients for contraceptive services, including client-centered contraceptive counseling; any contraceptive method received through Z-CAN; or the insertion, injection, or removal fees associated with a contraceptive method. If other related services were provided during the same visit (e.g., Pap smear), the patient could be charged or insurance billed. Z-CAN physicians were reimbursed fees for client-centered contraceptive counseling and method provision commensurate with Medicaid fee schedules in the continental United States. When a LARC device was placed, private practices received bundled reimbursement that included both insertion and removal fees paid at the time of placement, with the understanding that the clinician would provide LARC removal services when desired in the future, even if that was after the Z-CAN program ended. Z-CAN physicians working in federally funded community health centers were not provided the bundled reimbursement but were provided the full range of reversible methods at no cost for patients.

Fig. 1.

Zika Contraception Access Network (Z-CAN) LARC Removal Safety Net. *Long acting reversible contraception (LARC) includes intrauterine devices (IUD) and contraceptive implants.

Z-CAN patients received information at their initial visit that no-cost LARC removal was included in the program and that communication channels were available to report complaints by email or telephone hotline. In addition, a patient education website with a Z-CAN clinic locator and information about the hotline and email was established and a Facebook page that redirected patients to the patient education website. Z-CAN patients that left Puerto Rico could contact the program for assistance finding a physician or clinic to remove LARC outside of Puerto Rico, with the understanding that the woman would be responsible for some additional costs.

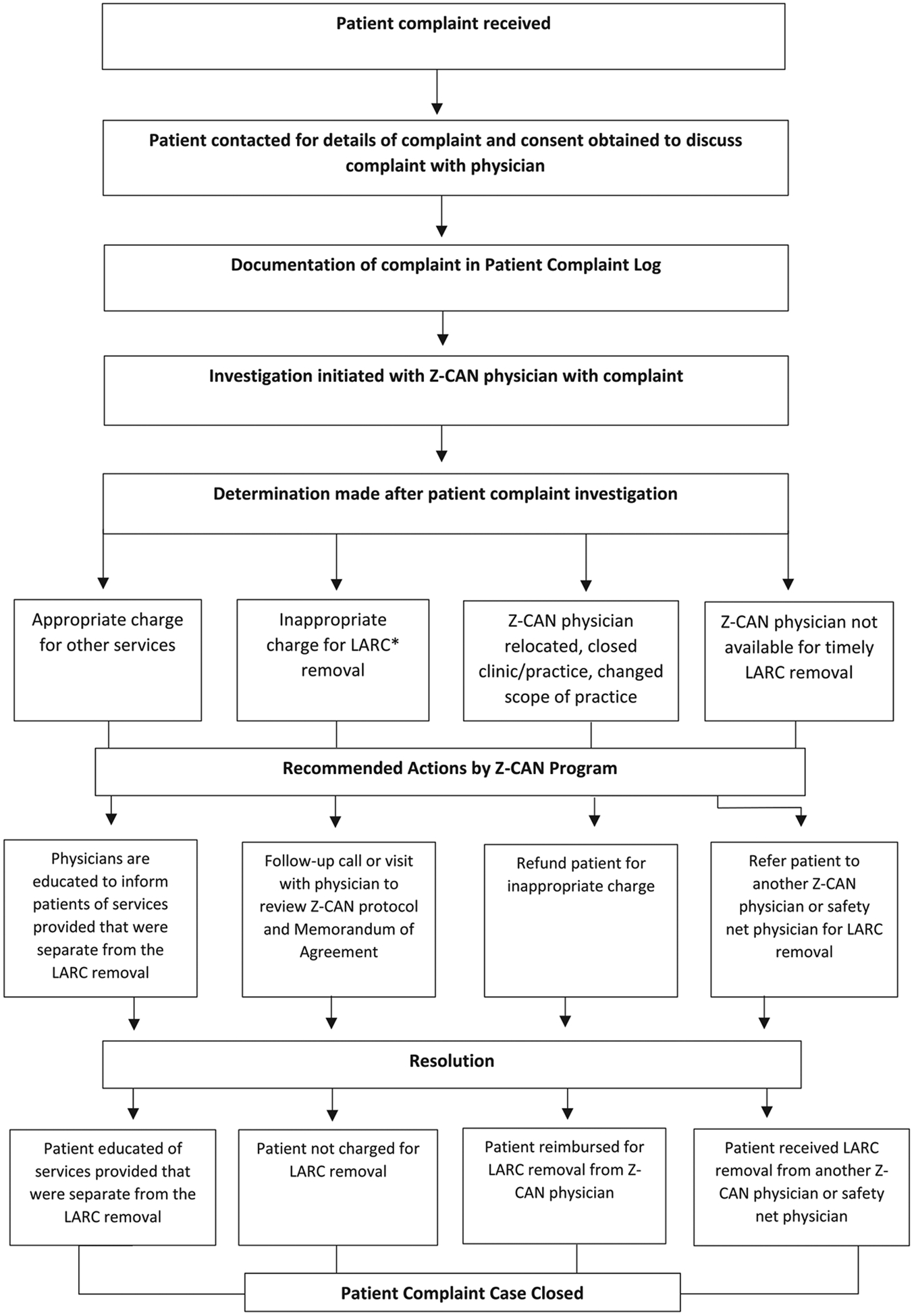

A standard operating procedure was developed to manage the complaint process for post-Z-CAN LARC removal charges (Fig. 2). The CDC Foundation documented each patient complaint on a Z-CAN patient complaint form. Detailed information was entered into a patient complaint log database and stored on a secure server. Each patient reported complaint was investigated to determine if the charge was appropriate, and the recommended action steps and resolution for each complaint were documented. CDC Foundation staff investigated each complaint by contacting the patient to gather information, and with patient consent, discussed the complaint with the physician. CDC Foundation documented the complaint as a potential LARC removal charge (i.e., patient informed of cost for removal), a LARC removal charge (i.e., patient charged and paid for removal), or the Z-CAN physician was not available for LARC removal. Following the investigation, a determination was made whether the charge was appropriate (e.g., unrelated service provided at the visit) or inappropriate (e.g., charge for LARC removal). Recommended actions were documented. For appropriate charges, physicians were educated to inform patients of services provided separate from the LARC removal. Physicians with inappropriate charges were followed up with a call to review MOA and Z-CAN protocol, clarify policies that Z-CAN patients were not to be charged for LARC removal, and request patients be refunded, if appropriate. Subsequent patient complaints about the same physician warranted further communication from the CDC Foundation, followed by a warning letter sent by certified mail to document the complaint and recommended action. If a resolution could not be reached, the CDC Foundation worked with the patient to find another Z-CAN physician or referred the patient to a Z-CAN safety net physician for a LARC removal at no cost to the patient. The CDC Foundation established formal partnerships with three Z-CAN physician champions, strategically located across Puerto Rico, to serve as safety net physicians. Although the Z-CAN program has ended, these physicians continue to provide clinical and technical assistance services for complicated LARC removals and, if necessary, provide routine LARC removals. All patient complaints remained open until an acceptable resolution was reached (i.e., patient received no-cost LARC removal, received reimbursement from physician for LARC removal charge). The Z-CAN program was approved as non-research public health practice.

Fig. 2.

Zika Contraception Access Network (Z-CAN) Complaint Management Process. *Long acting reversible contraception (LARC) includes intrauterine devices (IUD) and implants.

Furthermore, Z-CAN staff conducted secret shopper calls (n = 49) to every clinic that received a complaint about LARC removal charges. If the clinic mentioned a charge for removal, they received a call back from CDC Foundation to discuss that Z-CAN patients should not be charged for routine LARC removals, per the MOA.

Approximately 30-months after the Z-CAN program ended, we reviewed complaints filed related to requests for LARC removal among the 20,381 women who had LARC placed through the Z-CAN program. Complaints were categorized in an effort to understand program challenges in ensuring prompt no-cost LARC removal when desired.

3. Results

Between September 2017 and February 2020, the CDC Foundation received a total of 72 patient reported complaints by email (97.2%) or telephone hotline (2.8%). Of these, 6 patients did not respond to follow-up to enable an investigation and three patients relocated outside of Puerto Rico, allowing further evaluation of 63 complaints. Of the 153 Z-CAN physicians, 49 (32.0%) had at least one complaint, 10 (6.5%) had 2 complaints, and 2 (1.3%) had 3 complaints filed against them; only 8% of physicians had more than one complaint. Among complaints included in our analysis (n = 63), the majority (98%) involved a provider from a private practice/other clinic. Complaints were largely (87%) due to LARC removal charges (Table 1) while 13% involved Z-CAN physicians not being available for LARC removal.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of patient reported complaints for LARC* removal from the Zika Contraception Access Network (Z-CAN) post-program, September 2017–February 2020.

| Complaint characteristic | Total N = 63 n (%) | Implant N = 44 n (%) | IUD N = 19 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic type | |||

| Private practice/other± | 62/63 (98.4) | 44/44 (100.0) | 18/19 (94.7) |

| Community Health Center | 1/63 (1.6) | 0/44 (0.0) | 1/19 (5.3) |

| Patient complaint reported | |||

| Potential LARC removal charge§ | 48/63 (76.2) | 36/44 (81.8) | 12/19 (63.2) |

| LARC removal charge§ | 7/63 (11.1) | 5/44 (11.4) | 2/19 (10.5) |

| Z-CAN physician not available for LARC removal | 8/63 (12.7) | 3/44 (6.8) | 5/19 (26.3) |

| Determination after patient complaint investigation | |||

| Appropriate charge for other services | 5/63 (7.9) | 4/44 (9.1) | 1/19 (5.2) |

| Inappropriate charge for LARC removal | 45/63 (71.4) | 33/44 (75.0) | 12/19 (63.2) |

| Z-CAN physician relocated, closed clinic/practice, changed scope of practice | 11/63 (17.5) | 7/44 (15.9) | 4/19 (21.1) |

| Z-CAN physician not available for timely LARC removal | 2/63 (3.2) | 0/44 (0.0) | 2/19 (10.5) |

| Recommended actions by Z-CAN program# | |||

| Follow-up call with physician to review Z-CAN protocol and Memorandum of Agreement | 52/63 (82.5) | 39/44 (88.6) | 13/19 (68.4) |

| Refund patient for inappropriate charge | 6/63 (9.5) | 4/44 (9.1) | 2/19 (10.5) |

| Refer patient to another Z-CAN physician for LARC removal | 7/63 (11.1) | 6/44 (13.6) | 1/19 (5.3) |

| Refer patient to Z-CAN safety net physician for LARC removal | 20/63 (31.7) | 11/44 (25.0) | 9/19 (47.4) |

| Resolution | |||

| Patient not charged for LARC removal | 29/63 (46.0) | 23/44 (52.3) | 6/19 (31.6) |

| Patient reimbursed for LARC removal from Z-CAN physician | 6/63 (9.5) | 3/44 (6.8) | 3/19 (15.7) |

| Patient received LARC removal from another Z-CAN physician | 6/63 (9.5) | 5/44 (11.4) | 1/19 (5.3) |

| Patient received LARC removal from Z-CAN safety net physician | 22/63 (34.9) | 13/44 (29.5) | 9/19 (47.4) |

Long acting reversible contraception includes intrauterine devices (IUD) and implants.

A potential LARC removal charge was when clinic staff informed the patient that there would be a cost for LARC removal.

A LARC removal charge was when the patient was charged and paid for LARC removal.

Proportions do not add to 100% since more than 1 recommended action may have been appropriate for some patient complaints.

Other clinic type includes academic and public health clinics.

In most cases (83%) a follow-up call was made to the Z-CAN physician to review MOA and Z-CAN protocol; some (9.5%) prompted reimbursement of patients for inappropriate charge or referral to another Z-CAN physician (11.1%) or safety net provider (31.7%) for LARC removal (Table 1). On average, patient complaints were resolved within 28 days (range 1 105 days).

4. Discussion

The Z-CAN program s efforts to ensure prompt LARC removal when desired appear to have been largely successful. This highlights the importance of client-centered counseling at the time of placement of a LARC that includes information on how to access removal services. When physicians were no longer able to serve their Z-CAN patients, it was important to have the option of other Z-CAN physicians. The MOA specified that Z-CAN physicians could remove any Z-CAN patient s LARC devices but could not charge for the removal. Other programs using prospective bundled reimbursement models (i.e., single, predetermined bundled payment for a specific episode of care) [15] have reported improved patient outcomes [16], but have also reported challenges with management of financial risk between payers and providers; mechanisms to collect, allocate, and manage funds; and issues with care transition between a patient and different provider [16]. Building capacity of physicians to manage funds received from a bundled reimbursement for future LARC removal expenses and clear communication about care coordination of Z-CAN LARC removal services outside of their practice could have been strengthened prior to the bundled payment implementation and can be incorporated into program development.

This analysis is limited by relying on individual patient experiences that may not be generalizable and likely underestimate the true level of complaints from women seeking LARC removal. In addition, physicians who were contacted as part of complaint investigations may have provided socially acceptable answers to reach resolution. However, less than 10% of physicians received more than 1 complaint. Given that LARC methods are FDA-approved for 3 10 years, ongoing vigilance will be needed to assess the effectiveness of the LARC removal safety net through 2027. In the meantime, safeguards used by Z-CAN to prevent reproductive coercion and promote reproductive autonomy can inform other contraception access programs beyond the threat of Zika and are critical to continue meeting the reproductive needs of women.

Acknowledgments

The Zika Contraception Access Network (Z-CAN) program was supported by the National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Inc. (CDC Foundation). This support was made possible through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, The Pfizer Foundation, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The CDC Foundation also secured large-scale donations, offers of contraceptive products, support tools, and services from Bayer, Allergan, Medicines360, Americares and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Mylan, The Pfizer Foundation, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Church & Dwight Co., Inc., RB, Power to Decide (formerly The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy), Upstream USA, and Market Vision, Culture Inspired Marketing.

The Z-CAN program would like to acknowledge the collaborative contributions of (in alphabetical order) the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Beyond the Pill Program at the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health (University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine), Health Resources and Services Administration Office of Regional Operations, Power to Decide (formerly The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy), the Puerto Rico Department of Health, Puerto Rico Obstetrics and Gynecology, the Puerto Rico Primary Care Association, and Upstream USA. The funders and collaborators had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding source: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In addition, the views and conclusions in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the CDC Foundation.

Conflict of interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Romero L, Koonin LM, Zapata LB, Hurst S, Mendoza Z, Lathrop E, et al. Contraception as a medical countermeasure to reduce adverse outcomes associated with Zika virus infection in Puerto Rico: The Zika Contraception Access Network Program. Am J Public Health 2018:S227–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lathrop E, Romero L, Hurst S, Bracero N, Zapata LB, Frey MT, et al. The Zika Contraception Access Network: a feasibility programme to increase access to contraception in Puerto Rico during the 2016 17 Zika virus outbreak. Lancet Public Health 2018;3(2):e91–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Olson SM, Delaney A, Jones AM, Carr CP, Liberman RF, Forestieri NE, et al. Updated baseline prevalence of birth defects potentially related to Zika virus infection. Birth Defects Res 2019;111(13):938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tepper NK, Goldberg HI, Vargas Bernal MI, Rivera B, Frey MT, Malave C, et al. Estimating contraceptive needs and increasing access to contraception in response to the Zika virus disease outbreak Puerto Rico. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;2016(65). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Briggs L. Contraceptive programs: The risk of coercion. Womens Health J 1994:52–3. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2014;46(3):171–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Warren CW, Westoff CF, Herold JM, Rochat RW, Smith JC. Contraceptive sterilization in Puerto Rico. Demography 1986;23(3):351–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boring CC, Rochat RW, Becerra J. Sterilization regret among Puerto Rican women. Fertil Steril 1988;49(6):973–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ordover N. Puerto Rico 2014. [Available from: http://eugenicsarchive.ca/discover/connections/530ba18176f0db569b00001b.

- [10].PBS. People & Events: The Puerto Rico Pill Trials 2001. [Available from: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh//amex/pill/peopleevents/e_puertorico.html.

- [11].Gubrium AC, Mann ES, Borrero S, Dehlendorf C, Fields J, Geronimus AT, et al. Realizing reproductive health equity needs more than long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). Am J Public Health 2016;106(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Higgins JA, Kramer RD, Ryder KM. Provider bias in long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) promotion and removal: perceptions of young adult women. Am J Public Health 2016;106(11):1932–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Strasser J, Borkowski L, Couillard M, Allina A, Wood SF. Access to removal of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods is an essential component of high-quality contraceptive care. Womens Health Issues 2017;27(3):253–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lathrop E, Hurst S, Mendoza Z, Zapata L, Cordero P, Powell R, et al. The Zika Contraception Access Network: final program data and factors associated with LARC removal. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135(5):1095–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. Bundled payments for care improvement initiative fact sheet: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [Available from: http://www.innovations.cms.gov/Files/fact-sheet/Bundled-Payment-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

- [16].Delisle DR. Big things come in bundled packages: implications of bundled payment systems in health care reimbursement reform. Am J Med Qual 2013;28(4):339–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]