Abstract

Background

Chronic urticaria (CU) is characterized by itchy recurrent wheals, angioedema, or both for 6 weeks or longer. CU can greatly impact patients' physical and emotional quality of life. Patients with chronic conditions are increasingly seeking information from information and communications technologies (ICTs) to manage their health. The objective of this study was to assess the frequency of usage and preference of ICTs from the perspective of patients with CU.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 1800 patients were recruited from primary healthcare centers, university hospitals or specialized clinics that form part of the UCARE (Urticaria Centers of Reference and Excellence) network throughout 16 countries. Patients were >12 years old and had physician-diagnosed chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) or chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU). Patients completed a 23-item questionnaire containing questions about ICT usage, including the type, frequency, preference, and quality, answers to which were recorded in a standardized database at each center. For analysis, ICTs were categorized into 3 groups as follows: one-to-one: SMS, WhatsApp, Skype, and email; one-to-many: YouTube, web browsers, and blogs or forums; many-to-many: Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

Results

Overall, 99.6% of CU patients had access to ICT platforms and 96.7% had internet access. Daily, 85.4% patients used one-to-one ICT platforms most often, followed by one-to-many ICTs (75.5%) and many-to-many ICTs (59.2%). The daily ICT usage was highest for web browsers (72.7%) and WhatsApp (70.0%). The general usage of ICT platforms increased in patients with higher levels of education. One-to-many was the preferred ICT category for obtaining general health information (78.3%) and for CU-related information (75.4%). A web browser (77.6%) was by far the most commonly used ICT to obtain general health information, followed by YouTube (25.8%) and Facebook (16.3%). Similarly, for CU-specific information, 3 out of 4 patients (74.6%) used a web browser, 20.9% used YouTube, and 13.6% used Facebook. One in 5 (21.6%) patients did not use any form of ICT for obtaining information on CU. The quality of the information obtained from one-to-many ICTs was rated much more often as very interesting and of good quality for general health information (53.5%) and CU-related information (51.5%) as compared to the other categories.

Conclusions

Usage of ICTs for health and CU-specific information is extremely high in all countries analyzed, with web browsers being the preferred ICT platform.

Keywords: (3–5) ICT, Information and communications technology, Urticaria, Self-management

Abbreviations: Apps, applications; CIndU, chronic inducible urticaria; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; CU, chronic urticaria; HCP, healthcare provider; ICT, information and communications technologies; SEM, self-management education; SMS, short messaging service; UAE, United Arab Emirates; UCARE, Urticaria Centers of Reference and Excellence

Introduction

Chronic urticaria (CU) is characterized by the recurrence of itchy wheals, angioedema, or both for more than 6 weeks and is divided into 2 types: chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), which has no distinct or definite external trigger,1 and chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU), of which there are several subtypes and distinct and definite external triggers, such as sunlight in solar urticaria.2 It has been estimated that at any given time, CSU affects 1% of the global population, which accounts for approximately two-thirds of all CU cases.3,4

The intensity of pruritus, recurrence of wheals and swellings, and unpredictable nature of CU can all greatly impact patients' quality of life, affecting both physical and emotional health.5, 6, 7, 8 The current first- and second-line therapies for CU, second-generation H1-antihistamines at licensed doses and up dosed (up to 4x) second-generation H1-antihistamines,2 are insufficient to control the disease in around half of CSU patients.4 This is one of the reasons why adherence to medical treatments is low in patients with CU, with one study reporting non-compliance with recommended treatment regimens in the majority (72%) of patients.9

Patients living with chronic conditions are increasingly turning to self-management education (SME) as a means of taking control of their health. Indeed, SME is recommended because it can help improve treatment outcomes and quality of life, and it may reduce depression and anxiety associated with long-term conditions.10 With an increasing array of information and communications technologies (ICTs) available to facilitate SME, many patients use the internet to obtain information about their disease.11 ICTs in healthcare can be defined as digital technologies that support the exchange, knowledge transfer, and electronic storage and processing of information to promote health, manage chronic illness, and treat disease.12,13 They include web browsers, emails, forums or blogs, and social media platforms, as well as various mobile applications (apps).

ICTs are being explored for medical purposes to improve clinical outcomes and enhance communications between healthcare providers (HCPs) and patients. During the past 25 years, especially the past 5 years,14 ICTs have become powerful informational tools to provide health-related knowledge to HCPs and patients alike.14

A previous study found e-mail and SMS (short messaging service) to be the most popular forms of electronic communication for receiving and seeking information among patients with asthma. WhatsApp was preferred among patients in the age category 12–40 years.15

Patients with CU have a high need for knowledge about their disease, to discover more about its causes, course, possible trigger factors, available treatment options, and prognosis. This high need is mirrored by the fact that CU patient-physician consultations are particularly long and frequent.16 It is thought that in addition to consultations, ICTs are becoming increasingly important to patients with CU, who use ICTs to interact with each other about their condition, to share coping experiences, to offer social support, and to support communication with their physician. The current study aims to investigate this further.

As of yet, it is not known which general or specific ICTs patients use to obtain information on health-related topics and specifically on CU, or how patients perceive the currently available information via ICTs. Gaining knowledge on this is important to better inform CU patients about their disease, to match the right informational content to the right ICTs, and to provide CU-specific ICT platforms if seen as necessary by patients. To this end, an international study was set up in the UCARE (Urticaria Centers of Reference and Excellence) network17 to assess the frequency and preference of ICTs used by CU patients for general health-related and CU-related information, and to assess the quality of information available via ICTs from the patients' perspective.

Methods

Study design and setting

In this anonymous, cross-sectional study, 1800 patients were recruited from primary healthcare centers, university hospitals or specialized clinics (public or private), that are part of the UCARE network. The following countries were involved: Germany, Greece, Spain, Poland, Turkey, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Denmark, India, Russia, Brazil, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Peru, Iran, Argentina, and China.

Patient population

Patients were included on a first-come basis, if they were over 12 years old and had physician-diagnosed CSU or CIndU. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of any other dermatological disorder (eg, contact dermatitis), had an intellectual disability, or refused to participate in the study.

Data collection and measurements

During or after a medical consultation, or during their stay at a health center, each patient completed the study-related questionnaire (see Supplement 1) in the presence of trained medical staff, who answered any queries if they arose.

For this purpose, a 23-item questionnaire was developed and reviewed by an expert panel of physicians who evaluated potential items to be included. The final survey contained a range of questions about the use of ICTs; reported herein are results on the type, frequency, preference, and patient-rated quality of ICTs, for obtaining information on health topics in general, and for getting information specifically about CU.

The questionnaire assessed whether patients owned a cell phone, a smartphone, and had internet access. It evaluated the usage rate (daily, at least once a week, at least once a month, less than once a month, and never) of several ICTs, online communication tools, and social media platforms (WhatsApp, email, SMS, Skype, web browser, YouTube, blog or forum, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn). Additionally, the questionnaire quantified patients’ use of ICTs, and rated the quality of general health-related and CU-related information patients obtained through various ICT platforms using the following scale: not interesting, a little interesting, moderately interesting, very interesting, and extremely interesting.

Furthermore, the questionnaire evaluated patient demographics, including the type of CU, age, sex, duration of CU, area of residence, education level, and employment status.

Standardization of data

To help standardize the results, researchers trained interviewers and data collectors on the content of the survey and on how to answer patients' questions before completion. Surveys collected at each center were recorded in a standardized database, which were then transferred to the leading center and consolidated in a single central database for processing and statistical analysis. Data security and protection was preserved at all points during this process.

Ethical considerations

Before participating in the survey, patients were informed in detail about the purpose of the study and all provided verbal informed consent.

This study was approved by the ethics committee Comité de ética e Investigación en Seres Humanos (HCK-CEISH-19-0059), Guayaquil, Ecuador, and by the ethics committees of the participating UCAREs, as required. With the information recollected in the survey, personal identification was not possible; as such anonymity and personal data protection were preserved.

Statistical analysis

A chi-squared test was employed to assess the association between patient demographics and characteristics (independent variables) and internet access or owning a cell phone or smartphone, and the frequency of use of each ICT type.

For data analysis, we categorized the ICTs post-hoc into one of the following three categories:

-

•

One-to-one (dialogic): SMS, WhatsApp, Skype, and email

-

•

One-to-many (informative): YouTube, web browsers, and blogs or forums

-

•

Many-to-many (social): Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant for all tests. In case of missing data, these data were not included in the calculation of proportions but the number of missing datasets is provided.

Results

Population characteristics

Table 1 shows the overall population characteristics and demographics for this study. Patients covered a wide range of age groups and included those with CSU (1134/1,800, 63.0%), CIndU (328/1,800, 18.2%), and CSU + CIndU (334/1,800, 18.6%). For questionnaire contributions by country, see Supplement 2. Most patients were educated to secondary/high school (583/1,800, 32.4%) or undergraduate/college level (622/1,800, 34.6%), and half (901/1,900, 50.1%) were in employment.

Table 1.

Population characteristics and demographics.

| N of patients (total n = 1800) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of chronic urticaria (%) | ||

|

63.0 | 1134 |

|

18.2 | 328 |

|

18.6 | 334 |

|

0.2 | 4 |

| Mean age±SD (median) in years | 40.7 ± 14.9 (38) | 1796 |

| Sex distribution (female:male) (%) | 69.8:30.2 | 1256:544 |

| Mean duration of urticaria±SD (median) in years | 5.5 ± 6.9 (3) | 1799 |

| Area of residence (%) | ||

|

25.7 | 462 |

|

74.3 | 1338 |

| Education level (%) | ||

|

0.7 | 12 |

|

8.5 | 153 |

|

32.4 | 583 |

|

34.6 | 622 |

|

23.7 | 427 |

|

0.2 | 3 |

| Employment status (%) | ||

|

50.1 | 901 |

|

10.4 | 187 |

|

4.7 | 85 |

|

9.8 | 177 |

|

12.1 | 218 |

|

11.4 | 206 |

|

1.4 | 26 |

CIndU, chronic inducible urticaria; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; ICT, information and communications technology; n, number of patients; SD, standard deviation.

Almost all CU patients have access to ICTs and use them regularly

ICT platforms were broadly used by all CU patients: 99.6% of 1800 patients (yes n = 1791; no n = 8; missing n = 1) had access to ICTs (as either a cell phone [of any type and functionality], smartphone, or internet access (via any means), 94.9% (yes n = 1709; no n = 91) had a smartphone, and 96.8% (yes n = 1741; no n = 58; missing n = 1) had internet access.

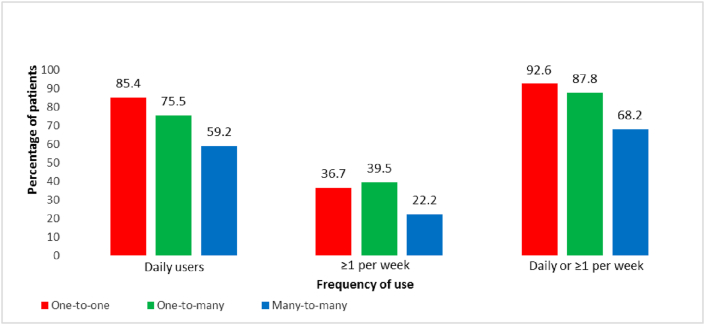

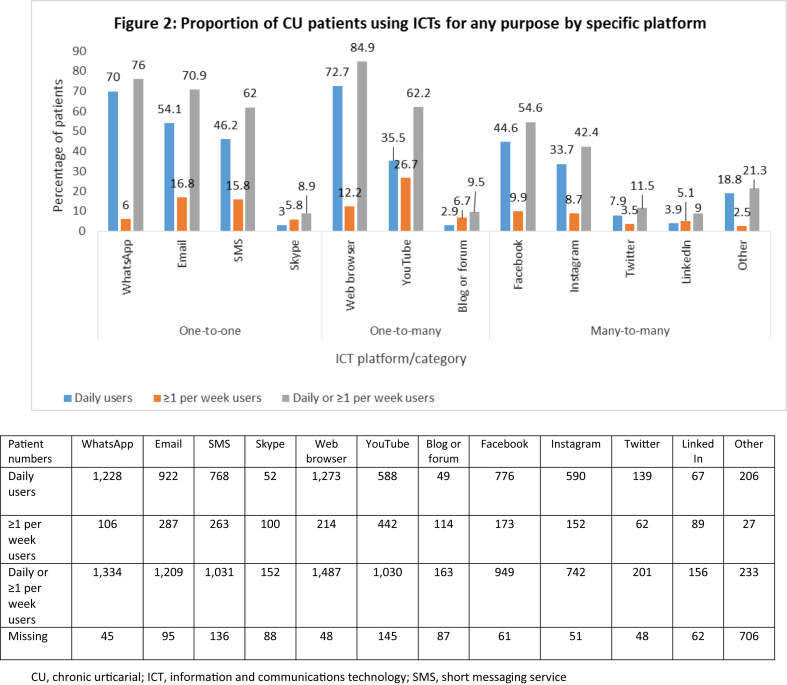

Daily, 85.4% of patients (yes n = 1286; no n = 220; missing n = 294) used one-to-one ICT platforms most often, followed by one-to-many ICTs (75.5%; yes n = 1172; no n = 381; missing n = 247), and many-to-many ICTs (59.2%; yes n = 967; no n = 667; missing n = 166; Fig. 1). The daily ICT usage was highest for web browsers (72.7%) and WhatsApp (70.0%), followed by emails (54.1%), SMS (46.2%), Facebook (44.6%), YouTube (35.5%), and Instagram (33.7%; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Patients were asked how often they used each ICT for any purpose (SMS, WhatsApp, Skype, email [one-to-one]; YouTube, web browsers, blogs or forums [one-to-many]; Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn [many-to-many]) by ticking one of the following boxes: never, less than once a month, at least once a month, at least once a week, and every day. The results were grouped by ICT category for the purposes of analysis. Missing information is not included in the computation of proportions.

Fig. 2.

Patients were asked how often they used each ICT for any purpose (SMS, WhatsApp, Skype, email, YouTube, web browsers, blogs or forums, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn) by ticking one of the following boxes: never, less than once a month, at least once a month, at least once a week, every day. The graph shows the percentage of patients and the table shows the number of patients who ticked each box. Missing information is not included in the computation of proportions.

ICT usage differs depending on country, level of education and age

There were no major differences concerning sex; one-to-one ICTs were used by 92.3% (yes n = 431; no n = 36; missing n = 77) of males and 92.8% (yes n = 964; no n = 75; missing n = 217) of females every day or at least weekly. Similarly, we saw no differences with the residential area; one-to-one ICTs were used by 95.3% (yes n = 381; no n = 19; missing n = 62) of patients living in rural areas and 91.7% (yes n = 1014; no n = 92; missing n = 232) of patients living in urban areas every day or at least weekly. The use of ICTs did not appear to change with the duration of disease, but patients who had experienced CU for 1–2 years used ICTs slightly more often to obtain general health and CU-related information than those patients with a longer disease duration.

Considerable differences exist between countries; general ICT usage was weak in Iran, China, and Greece, and comparably strong in India, Turkey, the UAE, Peru, and the Netherlands. ICTs in the many-to-many category were used particularly infrequently in Iran and often used in India, Denmark, Turkey, the UAE, and Peru.

The general usage of ICT platforms increased in patients with higher levels of education, which was true across all three ICT categories; one-to-one ICT platforms were used every day or at least once a week in patients with no schooling (63.6%; yes n = 7; no n = 4; missing n = 1), middle/primary school (74.0%; yes n = 94; no n = 33; missing n = 26), secondary/high school (92.6%; yes n = 438; no n = 35; missing n = 110), undergraduate/college (96.6%; yes n = 511; no n = 18; missing n = 93), and postgraduate studies (94.2%; yes n = 342; no n = 21; missing n = 64). One-to-one ICTs were used by large proportions of all age groups, while one-to-many ICTs and, particularly many-to-many ICTs, were less often used by patients 40 years and older, with further decreasing frequency in older age groups.

One-to-many ICTs are most commonly used by CU patients to obtain general health and CU-related information

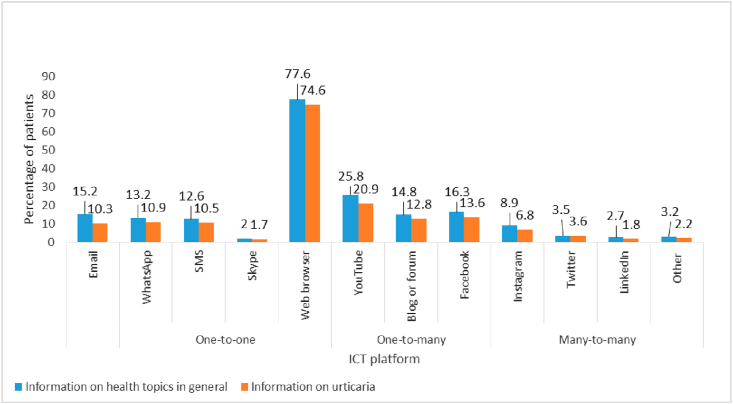

One-to-many was the preferred ICT category for obtaining general health information, used by 78.9% of patients (yes n = 1410; no n = 377; missing n = 13) and for obtaining CU-related information (used by 75.9% of patients; yes n = 1357; no n = 431; missing n = 12). Web browsers (77.6%; yes n = 1391; no n = 401; missing n = 8) were by far the most commonly used ICTs to obtain general health information, followed by YouTube (25.8%; yes n = 461; no n = 1329; missing n = 10) and Facebook (16.3%; yes n = 292; no n = 1499; missing n = 9; Fig. 3); 18.6% of patients (no n = 331; missing n = 17) did not use an ICT platform for this purpose. Similarly, when obtaining information specifically on CU, 3 out of 4 patients (74.6%; yes n = 1336; no n = 456; missing n = 8) used a web browser, 20.9% (yes n = 374; no n = 1417; missing n = 9) used YouTube and 13.6% (yes n = 244; no n = 1547; missing n = 9) used Facebook. One in 5 (21.6%; no n = 385; missing n = 14) patients did not use any form of ICT for obtaining information on CU.

Fig. 3.

Patients were asked if they had used any of the following types of media to obtain information on their health and medical problems, or specifically to obtain information about urticaria; they could mark options for general health information and CU-specific information: SMS, WhatsApp, Skype, email, YouTube, web browsers, blogs or forums, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. Analyses of all patients, proportions are provided. Missing information is not included in the computation of proportions.

There were no major sex differences concerning the use of ICT platforms to obtain general health or CU-related information. Patients with a higher level of education used ICTs more often to obtain information on general health or CU, thus mirroring the use of ICTs for any purpose.

Usage of ICTs for general health information was similar for various age ranges of adult patients, but ICTs were used less frequently by retired patients >60 years and younger patients <20 years (Table 2). One-to-many ICTs and, particularly many-to-many ICTs, were less often used by patients 40 years or older.

Table 2.

ICT usage by category for general health information and chronic urticaria-related information.

| General health information |

Chronic urticaria-related information |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-to -one |

One-to -many |

Many-to-many | One-to -one |

One-to-many | Many-to-many | |

| Sex: %, yes n/total patient n, (no n, missing n) | ||||||

| Male | 32.8% 178/542 (364, 2) |

76.4% 414/542 (128, 2) |

17.3% 94/543 (449, 1) |

23.6% 128/542 (414, 2) | 74.6% 405/543 (138, 1) |

12.7% 69/543 (474, 1) |

| Female | 25.6% 319/1246 (927, 10) |

80.0% 996/1245 (249, 11) |

21.7% 271/1247 (976, 9) |

21.0% 262/1247 (985, 9) |

76.5% 952/1245 (293, 11) |

18.8% 235/1247 (1,012, 9) |

| Age group: %, yes n/total patient n, (no n, missing n) | ||||||

| <20 years | 22.3% 21/94 (73, 2) |

72.3% 68/94 (26, 2) |

21.3% 20/94 (74, 2) |

18.1% 17/94 (77, 2) |

67.0% 63/94 (31, 2) |

18.1% 17/94 (77, 2) |

| 20–29 years | 33.1% 113/341 (228, 3) |

87.4% 298/341 (43, 3) |

23.7% 81/342 (261, 2) |

22.8% 78/342 (264, 2) |

84.2% 288/342 (54, 2) |

17.3% 59/342 (283, 2) |

| 30–39 years | 32.5% 166/510 (344, 4) |

89.0% 453/509 (56, 5) |

24.7% 126/510 (384, 4) |

24.4% 124/509 (385, 5) |

86.8% 441/508 (67, 6) |

20.2% 103/510 (407, 4) |

| 40–49 years | 29.6% 103/348 (245, 0) |

83.0% 288/347 (59, 1) |

21.6% 75/348 (273, 0) |

25.9% 90/348 (258, 0) |

81.6% 284/348 (64, 0) |

22.1% 77/348 (271, 0) |

| 50–59 years | 24.1% 64/266 (202, 0) |

70.7% 188/266 (78, 0) |

16.2% 43/266 (223, 0) |

19.2% 51/266 (215, 0) |

64.3% 171/266 (95, 0) |

12.8% 34/266 (232, 0) |

| >60 years | 12.9% 29/225 (196, 3) |

50.0% 113/226 (113, 2) |

8.4% 19/226 (207, 2) |

12.4% 28/226 (198, 2) |

47.8% 108/226 (118, 2) |

5.8% 13/226 (213, 2) |

| Disease duration: %, yes n/total patient n, (no n, missing n) | ||||||

| ≤1 year | 30.0% 118/393 (275, 1) |

79.0% 309/391 (82, 3) |

21.9% 86/393 (307, 1) |

21.9% 86/393 (307, 1) |

76.3% 299/392 (93, 2) |

15.8% 62/393 (331, 1) |

| >1-≤2 years | 33.8% 110/325 (215, 3) |

86.5% 283/327 (44, 1) |

25.4% 83/327 (244, 1) |

26.0% 85/327 (242, 1) |

85.3% 279/327 (48, 1) |

23.2% 76/327 (251, 1) |

| >2-≤5 years | 28.1% 151/537 (386,3) |

79.9% 429/537 (108, 3) |

17.7% 95/536 (441, 4) |

23.2% 124/535 (411, 5) |

75.7% 406/536 (130, 4) |

14.4% 77/536 (459, 4) |

| >5 years | 22.2% 118/532 (414, 5) |

73.3% 389/531 (142, 6) |

18.9% 101/533 (432, 4) |

17.8% 95/533 (438, 4) |

70.1% 373/532 (159, 5) |

16.7% 89/533 (444, 4) |

| Living area: %, yes n/total patient n, (no n, missing n) | ||||||

| Rural | 28.4% 130/457 (327, 5) |

82.3% 376/457 (81, 5) |

27.9% 128/458 (330, 4) |

24.9% 114/458 (344, 4) |

78.8% 361/458 (97, 4) |

26.2% 120/458 (338, 4) |

| Urban | 27.6% 367/1331 (964, 7) |

77.7% 1034/1330 (296, 8) |

17.8% 237/1332 (1,095, 6) |

20.7% 276/1331 (1,055, 7) |

74.9% 996/1330 (334, 8) |

13.8% 184/1332 (1,148, 6) |

Missing information is not included in the computation of proportions. ICT, information and communications technology; n, number of patients.

Patients living in rural areas tended to use ICT platforms slightly more often than those living in urban areas. This was particularly so for the many-to-many ICTs, to obtain general health information (27.9% vs. 17.8%), and especially for information on CU (26.2% vs. 13.8%; Table 2).

Patients rate one-to-many ICTs as the most interesting for obtaining health information

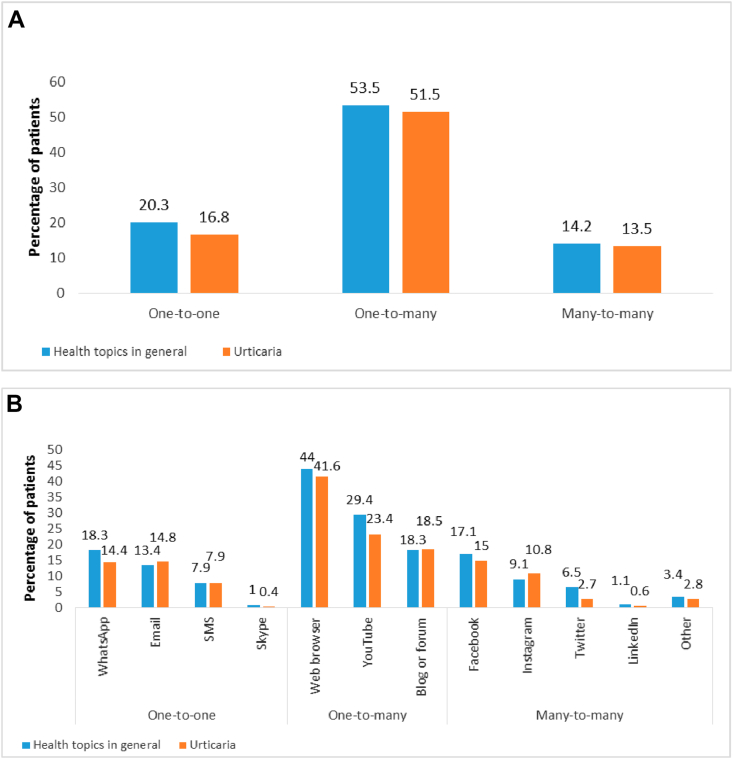

The quality of the information obtained from one-to-many ICTs was rated much more often as very interesting/of good quality to extremely interesting/of very good quality for general health information (53.5%; yes n = 268; no n = 233; missing n = 1299) and CU-related information (51.5%; yes n = 257; no n = 242; missing n = 1301) as compared to the one-to-one and many-to-many categories (Fig. 4A). Fig. 4B shows the patient-rated quality of information by specific ICT platform, which indicates that web browsers were rated most often as very or extremely interesting, or of good or very good quality. However, full information on the quality of information was available for only around 500 patients.

Fig. 4.

If patients had answered yes for using any type of media to obtain information about their health and medical problems or urticaria, the were asked how they rated the quality of information they obtained using one of the following categories: 1) not interesting, not helpful, very low quality; 2) slightly interesting, somewhat helpful, low quality; 3) moderately interesting and helpful, medium quality; 4) very interesting and helpful, good quality; 5) extremely interesting and helpful, very good quality. Data shown are for platforms that patients rated as very or extremely interesting/of good or very good quality A. by ICT category and B. by ICT platform. All patients were analyzed. Missing information is not included in the computation of proportions.

Discussion

Top-line results

This study is the first to demonstrate the ICT usage habits of patients with CU; results indicate that almost all (99.6%) patients had access to ICT platforms. To obtain general health and CU-related information, the one-to-many category was preferred, with web browsers being the overwhelming favorite, used by three out of four patients. The next most commonly used, YouTube, was used only by around one in four patients.

The population of this study

In total, 63.0% of patients included in this study had CSU, reiterating current estimates that CSU accounts for around two-thirds of all CU cases.4 We predicted that certain independent variables such as age and employment status had the potential to influence the use of ICTs; thus, to try to account for this we recruited a heterogeneous patient population that covered a range of ages, and we stratified results by patient characteristics.

Almost all CU patients have access to ICTs

Interestingly, only 0.4% of patients in this study did not have access to ICTs via cell phone, smartphone, or internet access. This is surprising because we included a wide cross-section of countries; the results indicate that the inclusion of lower-income countries did not appear to affect the accessibility to the internet. A previous report of ICT use in cancer patients in Ecuador found that only 43% of participants surveyed had internet access,18 less than half of what we report here. However, another report in patients with hypertension, also in Ecuador, showed internet access to be around 80%,19 indicating inconsistency across various medical conditions.

Patients use ICTs regularly for any purpose

Daily, patients used one-to-one (SMS, WhatsApp, Skype, and email) ICTs most often, followed by one-to-many (YouTube, web browsers, and blogs or forums), and many-to-many (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn) ICT platforms. The highest usage for specific ICT platforms were web browsers (72.7%) and WhatsApp (70.0%); this indicates that in addition to the one-to-many ICT web browsers, patients also display a high demand to communicate and acquire information through personalized one-to-one means. It should be noted, however, that some patients may have answered yes for the use of web browsers, YouTube, and blogs/forums ICTs, as YouTube and blogs/forums require a web browser for access.

ICT usage differs depending on country, age and level of education

We observed considerable differences in ICT usage between countries; general ICT usage was weak in Iran, China, and Greece, and comparably strong in India, Turkey, the UAE, Peru, and the Netherlands. ICTs in the many-to-many category were used particularly infrequently in Iran and often used in India, Denmark, Turkey, the UAE, and Peru. Low use in Iran and China may be explained by the fact that many-to-many ICTs are highly regulated or difficult to access in these countries, especially social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. However, we saw an unexpectedly high use of ICTs in the UAE, which also has high levels of censoring. The reasons behind this would be worth exploring in more detail to assess how this could affect optimal use; lower ICT usage in censored countries may have implications on development strategies for any new ICT.

Data have suggested that the use of ICTs correlates with an individual's level of education; higher levels of education are associated with increased ICT use or increased interest in using ICTs for health purposes.20 As expected, we found that more educated patients used ICTs frequently to acquire information on general health or CU. Nevertheless, ICTs were used by over 63% of patients with no schooling, indicating widespread use regardless of the level of education.

One-to-many ICTs are most commonly used by CU patients to obtain general health and CU-related information

One-to-many was the preferred ICT category for obtaining general health and CU-related information. This usage differs slightly from the ICT usage for any purpose, in that the frequency of WhatsApp use was substantially lower for health purposes. Patients used all the one-to-many platforms included in this study, plus Facebook, most often for acquiring health information, with relatively low usage of the other ICTs; this indicates that the one-to-many category is a clear favorite for CU patients, with a broad range of individuals being reached through these means.

Mirroring the general ICT usage, web browsers were without doubt the most commonly used ICTs for health and CU information, used by more than 3 out of 4 patients. The high use of web browsers also aligns with findings from other medical conditions, such as cancer.18 These results point to a potential question around patients’ perceptions of credibility; patients are more likely to trust a named, accredited medical organization, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence when seeking knowledge about their condition. They would likely have less confidence in reports, advertisements, and sponsored content on Instagram or Twitter because misinformation can quickly disseminate between individuals sharing posts, and the true source is often unidentified. It would be interesting to investigate further which websites patients use most often to seek CU information as the current information offers little insight into the most highly used websites.

Our results indicate that YouTube was the next most commonly used platform; however, usage dropped significantly to only 1 out of every 4 patients. YouTube could represent a feasible means for educating patients on CU. However, many videos are misleading, poor-quality, and uploaded by individuals with unknown credentials, with some even promoting unproven alternative treatments.21 Concerningly, one study investigating ICTs use in patients with hypertension found that the quality of YouTube videos was a poor predictor of viewer engagement. Individuals watched videos containing misleading or false information significantly more often compared to videos containing accurate information on hypertension.21 If HCPs advocate the use of a particular ICT to patients, they must have a responsibility to ensure high-quality and accurate information.22

Notably, the use of ICTs for obtaining health information was significantly reduced in older, retired patients. This low usage could be due to many factors concerning older generations, including age-related cognitive decline, negative attitudes towards technologies, perceived lack of usefulness,23 or simply no inclination to learn about new technologies; many older patients prefer to speak to their doctor or friends face-to-face.

The higher use of ICTs by patients living in rural areas vs. urban areas indicates that access to specialists is more limited in rural areas. It indicates that approaches to improving patient care through the use of ICTs may be especially helpful in countries or regions with a high rate of people and patients living in rural areas. Moreover, patients who live in rural areas may have different needs and expectations when it comes to ICTs. This should be explored further and specific strategies need to be developed to improve care in this patient population, based on the results of future studies.

Patients rate one-to-many ICTs as the most interesting for obtaining health information

More than half of patients questioned about the quality of information obtained from ICTs rated the one-to-many category as very to extremely interesting/of good or very good quality for health and CU-related information as compared to the other categories. Again, this reflects the higher use of platforms in the one-to-many category, and it follows that patients use the platforms in which they have the most interest. It does not necessarily point to the quality of information, but rather, what patients find most compelling to read. As indicated with YouTube, individuals’ viewings are higher for counterfeit channels rather than legitimate videos reporting reliable information.21

The use of ICTs has several potential advantages, including educating patients and HCPs, improving quality of care and exchange of information, and promoting patient-centered healthcare.13,24 Here, for the first time, we show that almost all CU patients have access to ICTs and most use them regularly for health and CU-related information, unlocking new opportunities for bidirectional patient-physician communications.

Study limitations

This study is limited by the risk of selection bias in the recruitment process, with the most serious patients who regularly visit their HCP participating. Patients included knew the purpose of this study, which may have influenced their answers. Also, the accessibility of ICTs differs between countries, which would have directly affected the results. Another limitation is that the sample sizes in some countries were small. Finally, a proportion of the survey data was missing because not all patients completed the questionnaires, leading to potential differences between responders and non-responders, for which we may have not fully accounted.

Conclusions

The results of this study show conclusively that CU patients use ICTs to acquire information about their condition and that their preferred platform is a web browser. These results may help support the development of a CU-specific ICT, which could provide patients with optimized, tailored disease management, and ultimately improve patient outcomes. Based on our results, we recommend that future efforts on improving patient education and information on CU should prioritize the one-to-many category, with particular focus on websites and YouTube videos from accredited urticaria experts and centers such as those in the UCARE network.

Ethics statement

The authors declare that this manuscript complies with the ethics in publishing guidelines.

Author contributions

The authors declare that they have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, of drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors have provided approval of the final version submitted.

Funding statement

This study was performed with intramural funding and financial support from the WAO.

Availability of data and materials

All study materials and data were available to all study centers and physicians.

Declaration of competing interest

M Maurer is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from: Allakos, Alnylam, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Biocryst, Blueprint, CSL Behring, FAES, Genentech, Kalvista Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Menarini, Moxie, MSD, Novartis, Pharming, Pharvaris, Roche, Sanofi, Shire/Takeda, UCB, and Uriach. K Weller is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from: Biocryst, CSL Behring, Dr. Pfleger, FAES, Moxie, Novartis, Shire/Takeda, and Uriach. M Magerl is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from Biocryst, CSL Behring, Kalvista Pharmaceuticals, Moxie, Novartis, Pharming, and Shire/Takeda. RR Maurer has no conflicts of interest. E Vanegas has no conflicts of interest. M Felix has no conflicts of interest. A Cherrez has no conflicts of interest. VL Mata has no conflicts of interest. A Kasperska-Zajac has no conflicts of interest. A Sikora has no conflicts of interest. D Fomina is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from: AstraZeneca, CSL Behring, Glaxo SmithKline, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi, and Shire/Takeda. E Kovalkova has no conflicts of interest. K Godse has no conflicts of interest. N Dheeraj Rao has no conflicts of interest. M Khoshkhui has no conflicts of interest. S Rastgoo has no conflicts of interest. RFJ Criado has no conflicts of interest. M Abuzakouk has no conflicts of interest. D Grandon has no conflicts of interest. M van Doorn is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from Abbvie, BMS, Celgene, Janssen Cilag, LEO Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Genzyme. S Valle has no conflicts of interest. E Magalhães de Souza Lima has no conflicts of interest. SF Thomsen is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from: Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB. GD Ramón has no conflicts of interest. EE Matos Benavides has no conflicts of interest. A Bauer has no conflicts of interest. Ana M Giménez-Arnau has held roles as a Medical Advisor for Sanofi and Uriach, and has research grants supported by Instituto Carlos III- FEDER, Novartis, and Uriach; she also participates in educational activities for Almirall, Genentech, Glaxo SmithKline, LEO Pharma, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi, and Uriach. E Kocatürk is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for Bayer, Novartis, and Sanofi. C Guillet has no conflicts of interest. JI Larco is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for: FAES, Novartis, and Sanofi. Z-T Zhao has no conflicts of interest. M Makris is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Glaxo SmithKline, Novartis, and Sanofi. C Ritchie has no conflicts of interest. P Xepapadak reports personal fees from Galenica Greece, Glaxo SmithKline, Nestle, Novartis, Nutricia, and Uriach, outside the submitted work. LF Ensina is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from Novartis, Sanofi, and Takeda. S Cherrez has no conflicts of interest. I Cherrez-Ojeda has no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Gillian Brodie of Orbit Medical Communications Ltd. for editorial assistance, and the Universidad Espiritu Santo. This project benefitted from the support of the GA2LEN network of urticaria centers of reference and excellence (UCARE, www.ga2len-ucare.com) and the World Allergy Organization (WAO).

Footnotes

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100475.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Maurer M., Rosen K., Hsieh H.J. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):924–935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuberbier T., Aberer W., Asero R. The EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2018;73(7):1393–1414. doi: 10.1111/all.13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fricke J., Avila G., Keller T. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy. 2020;75(2):423–432. doi: 10.1111/all.14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurer M., Weller K., Bindslev-Jensen C. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA(2)LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66(3):317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurer M., Staubach P., Raap U., Richter-Huhn G., Baier-Ebert M., Chapman-Rothe N. ATTENTUS, a German online survey of patients with chronic urticaria highlighting the burden of disease, unmet needs and real-life clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(4):892–894. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurer M., Abuzakouk M., Berard F. The burden of chronic spontaneous urticaria is substantial: real-world evidence from ASSURE-CSU. Allergy. 2017;72(12):2005–2016. doi: 10.1111/all.13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weldon D. Quality of life in patients with urticaria and angioedema: assessing burden of disease. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35(1):4–9. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vietri J., Turner S.J., Tian H., Isherwood G., Balp M.M., Gabriel S. Effect of chronic urticaria on US patients: analysis of the National health and wellness survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heng J.K., Koh L.J., Toh M.P., Aw D.C. A study of treatment adherence and quality of life among adults with chronic urticaria in Singapore. Asia Pac Allergy. 2015;5(4):197–202. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2015.5.4.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang A., Fouche A., Craig T.J. Patients perception of self-administrated medication in the treatment of hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(2):120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welch Cline R.J., Penner L.A., Harper F.W., Foster T.S., Ruckdeschel J.C., Albrecht T.L. The roles of patients' internet use for cancer information and socioeconomic status in oncologist-patient communication. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3(3):167–171. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0737001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagnon M.P., Desmartis M., Labrecque M. Systematic review of factors influencing the adoption of information and communication technologies by healthcare professionals. J Med Syst. 2012;36(1):241–277. doi: 10.1007/s10916-010-9473-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bashshur R.L., Shannon G.W., Krupinski E.A. National telemedicine initiatives: essential to healthcare reform. Telemed J e Health. 2009;15(6):600–610. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.9960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capurro D., Cole K., Echavarria M.I., Joe J., Neogi T., Turner A.M. The use of social networking sites for public health practice and research: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e79. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calderon J., Cherrez A., Ramon G.D. Information and communication technology use in asthmatic patients: a cross-sectional study in Latin America. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3(3) doi: 10.1183/23120541.00005-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weller K., Viehmann K., Brautigam M. Cost-intensive, time-consuming, problematical? How physicians in private practice experience the care of urticaria patients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10(5):341–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurer M., Metz M., Bindslev-Jensen C. Definition, aims, and implementation of GA(2) LEN urticaria centers of reference and excellence. Allergy. 2016;71(8):1210–1218. doi: 10.1111/all.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherrez Ojeda I., Vanegas E., Torres M. Ecuadorian cancer patients' preference for information and communication technologies: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(2):e50. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherrez-Ojeda I., Vanegas E., Felix M., Mata V.L., Gavilanes A.W., Chedraui P. Use and preferences of information and communication technologies in patients with hypertension: a cross-sectional study in Ecuador. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:583–590. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S208861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherrez-Ojeda I., Vanegas E., Calero E. What kind of information and communication technologies do patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus prefer? An Ecuadorian cross-sectional study. Int J Telemed Appl. 2018;2018:3427389. doi: 10.1155/2018/3427389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar N., Pandey A., Venkatraman A., Garg N. Are video sharing web sites a useful source of information on hypertension? J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8(7):481–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel R., Chang T., Greysen S.R., Chopra V. Social media use in chronic disease: a systematic review and Novel taxonomy. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1335–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y.H., Damnee S., Kerherve H., Ware C., Rigaud A.S. Bridging the digital divide in older adults: a study from an initiative to inform older adults about new technologies. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:193–200. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S72399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eysenbach G. What is e-health? J Med Internet Res. 2001;3(2):E20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3.2.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study materials and data were available to all study centers and physicians.