Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated Neem oil and Hypericum perforatum (Holoil®) for treatment of scleroderma skin ulcers related to calcinosis (SU-calc).

Procedure: We retrospectively analyzed 21 consecutive systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients with a total of 33 SU-calcs treated daily with Holoil® cream compared with a control group of 20 patients with 26 SU-calcs. Holoil® was directly applied to skin lesions, while the control group received only standard medication.

Results

Application of Holoil® either resulted in crushing and complete resolution of calcium deposits or facilitated sharp excision of calcinosis during wound care sessions in 27/33 cases (81.8%). Complete healing of SU-calc occurred in 15/33 (45%) of cases within a time period of 40.1 ± 16.3 (mean ± SD) days, while 18/33 (55%) of lesions improved in terms of size, erythema, fibrin and calcium deposits. Patients reported a reduction of pain (mean numeric rating scale 7.3 ± 1.9 at baseline versus 2.9 ± 1.4 at follow-up) The control group had longer healing times and a higher percentage of infections.

Conclusions

The efficacy of local treatment with neem oil and Hypericum perforatum suggest that Holoil® could be a promising tool in the management of SSc SU-calc.

Keywords: Systemic sclerosis, scleroderma, calcinosis, skin ulcers, neem oil, Hypericum perforatum

Introduction

Skin ulcers are one of the most frequent manifestations of systemic sclerosis (SSc). Skin ulcers frequently cause pain and disability, and may severely affect the quality of life of SSc patients. Standard systemic and local treatments may promote healing of digital ulcers and reduce the incidence of new-onset lesions.1 Skin ulcers associated with SSc encompass all cutaneous ulcerative lesions, while digital ulcers refers to lesions localized to fingertips, toe tips and/or close to the nails. However, a significant percentage of SS-associated skin ulcers are challenging to treat, mainly due to complicating infections or localization of lesions to cutaneous calcinosis (SU-calc).2

Calcinosis consists of deposits of calcium salts in the skin and subcutaneous tissues3,4 and affects up to 25% of SSc patients. Calcinosis generally develops several years following initial SSc diagnosis.5–7 Calcium deposits may have different sizes, shapes and localization; areas subjected to recurrent trauma, such as fingers and extensor articular surfaces are the most frequently involved. The typical symptoms are pain (usually described as stabbing) and functional limitation of involved joints. Calcinosis per se is very difficult to treat and is frequently complicated with skin ulceration, fistulisation and supra-infection,8–9 requiring antibiotic administration and/or surgical removal. Currently, no local or systemic treatments are available for SU-calc.10

Standard local therapies include debridement, disinfection and dressing ulcers with hydrogel or antiseptic dressings. These procedures are performed according to wound bed preparation principles as summarized in the acronym TIME: necrotic Tissue, Infection/inflammation, Moisture balance and Epithelization. Addressing the most important aspects of ulcer evaluation and management helps to accelerate healing of spontaneous ulcers.11

Hypericum perforatum and Azadirachta indica are plants with therapeutic properties. Their extracts have a wide range of medical applications, including the management of skin wounds, eczema, and burns.12–17 The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of Holoil®, a mixture of Neem oil (an extract from the fruits and seeds of Azadirachta indica) and Hypericum perforatum, for treating SU-calc in SSc patients in addition to standard local treatment.

Patients and methods

We consecutively enrolled SSc patients with SU-calc referred to our scleroderma unit over the past year. We evaluated the effects of Holoil® for local treatment of SU-calcs in these patients. Over the same period, a group of SSc patients with comparable SU-calcs was also consecutively evaluated as controls. All patients satisfied the ACR/EULAR 2013 classification criteria.18

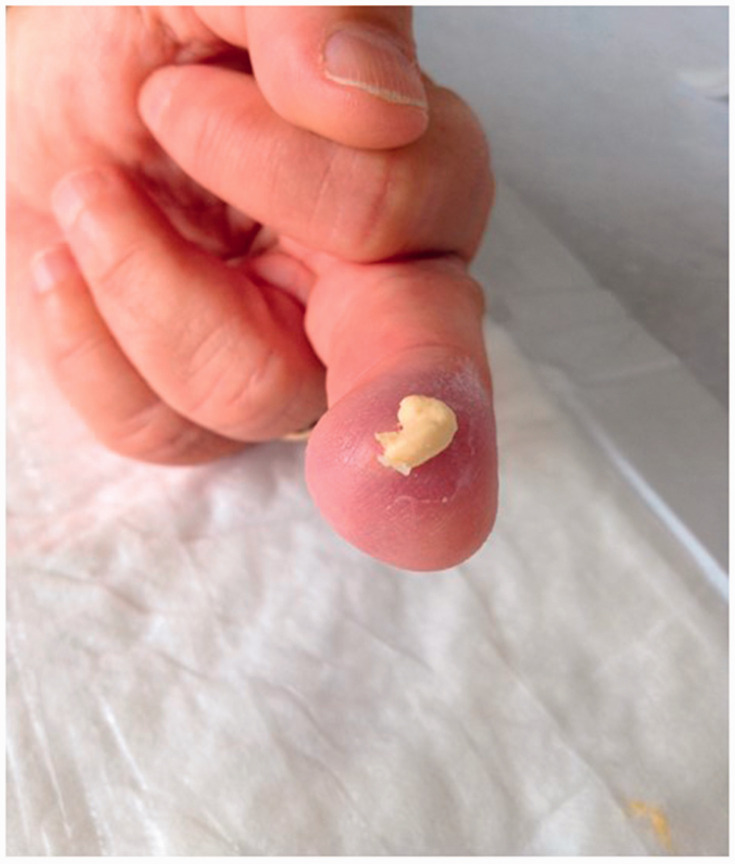

Patient clinical data were carefully evaluated on the basis of individual medical records including demographic and clinico-serological findings, SU-calc features (shape, consistency, localization, presence of exudates, smell and/or other signs of infection), and radiological imaging of the calcinotic area. Calcium deposits were also classified according to their shape and consistency on palpation into mousse (soft, chalky-like liquid underneath the skin) (Figure 1a), plate (palpable as large uniform agglomerate) (Figure 1b) and stone (palpable as a single stone or agglomerates of multiple stones of hard consistency) (Figure 1c). All patients were treated with standard systemic therapy for scleroderma vasculopathy at the time of SU-calc presentation using one or more vasoactive drugs. Local treatment of single SU-calcs was carried out according to the wound bed preparation model, mainly based on the extent and depth of debridement of skin lesions.2,11,19

Figure 1a.

Based on shape and consistency on palpation, calcinosis was classified as mousse (soft, chalky-like liquid underneath the skin).

Figure 1b.

Based on shape and consistency on palpation, calcinosis was classified as plate (palpable as large uniform agglomerate).

Figure 1c.

Based on shape and consistency on palpation, calcinosis was classified as stone (palpable as a single stone or agglomerates of multiple stones of hard consistency).

Debridement sessions were performed in our SSc skin ulcer clinic, and followed a treatment schedule tailored to individual patients on the basis of general clinical condition, severity of each cutaneous lesion, and potential complications such as local infections.9 After adequate preparation of the wound bed, Holoil® cream was applied directly to the lesion and covered with non-adhesive gauze. The first Holoil® administration was performed in our clinic, then patients were instructed to apply the cream daily at home. All patients were systematically re-evaluated and locally treated every 2 weeks by trained rheumatologists. Patients in the control group were also treated using standard systemic and local therapy without Holoil®.

Each patient was also instructed to record the following data daily: pain level on a 0–10 severity scale (NRS: numeric rating scale), use of analgesics, adverse reactions to wound dressing, clinical features of perilesional skin (maceration, excoriation), clinical signs of local infection (erythema, smell, swelling, increasing pain), and compliance in administering local medication (scored as 0: no difficulty, 1–2: mild-moderate difficulty, and 3: incapable of administering medication).

The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee (protocol n. 282/15), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Statistical analysis

Using Fisher’s exact test, we estimated odds ratios (ORs and 95% confidence intervals) to compare the responses of scleroderma SU-calcs in patients treated with Holoil® and control patients. Quantitative variables were reported as of means and standard deviation (SDs). Differences between groups were assessed using unpaired t-tests in GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Results

We consecutively enrolled 21 SSc patients with SU-calc and evaluated the effects of Holoil® for local treatment of 33 SU-calcs in these patients (21 F patients, mean ± SD age 61.1 ± 15.0 years, mean ± SD disease duration 15.2 ± 9.4 years). Over the same period, 20 SSc patients with 26 comparable SU-calcs was also consecutively evaluated as controls (20 F controls, mean ± SD age 57.3 ± 13.2 years, mean ± SD disease duration 14.3 ± 8.6 years). In total, 19/2 patients in the Holoil® group showed limited/diffuse cutaneous SSc, while 17/3 patients in the control group showed limited/diffuse cutaneous SSc (Table 1). Sixteen patients were receiving long-term treatment with calcium-channel-blockers, 21 were receiving intravenous prostanoids, and 12 were receiving anti-endothelin-1 therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of calcinosis-associated SSc skin ulcers and response to Holoil® compared with a control group.

| Holoil® group n (%) | Control group n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 21 | 20 | / |

| Calcinosis SU | 33 | 26 | / |

| Localization | |||

| Fingertips | 26 (78.8) | 19 (73.1) | / |

| Elbows | 3 (9.1) | 2 (7.7) | / |

| Knees | 2 (6.1) | 3 (11.6) | / |

| Forearms | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.8) | / |

| Wrists | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.8) | / |

| Shape and consistency at baseline | |||

| Stone/Plate | 32 (97.0) | 24 (92.3) | / |

| Mousse | 1 (3.0) | 2 (7.7) | / |

| Infections | |||

| S. aureus, S. maltophilia, S. hominis, E. coli | 6 (18.2) | 14 (53.8) | 0.0058* |

| Antibiotic request | 4 (12.1) | 11 (42.3) | 0.0146* |

| Treatment | |||

| Debridement | 33 (100) | 26 (100) | |

| + Holoil® alone | 26 (78.8) | – | <0.0001* |

| + Pressure on SU-cal as mousse | 6 (18.2) | – | 0.0297* |

| + Surgical removal | 1 (3.0) | 6 (23.1) | 0.0367* |

| Skin ulcer change | |||

| Healing | 15 (45.4) | 4 (15.4) | 0.0237* |

| Improvement | 18 (54.6) | 22 (84.6) | ns |

| Time Healing (days) | 40.1 ± 16.3 | 96.3 ± 10.7 | 0.0001* |

| NRS (0–10; mean ± SD) | |||

| Baseline | 7.3 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 2.1 | 0.7506 |

| End of follow-up | 2.9 ± 1.4 | 4.5 ± 2.4 | 0.0124* |

| Holoil® adherence | 33 (100) | – | / |

| Holoil® side effects (persistent erythema) | 1 (3.0) | – | / |

*p value < 0.05.

The characteristics of SU-calcs and their responses to Holoil®, as well as the results observed in the control group, are shown in Table 1. The majority of the SU-calcs were localized to the fingertips (26, 78.8%), elbows (3, 9.1%), knees (2, 6.1%) and more rarely on the wrists and forearms (3%). Calcium deposits were palpable at physical examination as stone/plate in 32/33 (97.0%) or as mousse in 1/33 (3.0%) of all cases confirmed by X-ray examination. Comparable SU-calc clinical features were observed in the control group.

The presence of SU-calc was associated with pronounced signs of local inflammatory reactions such as edema involving the surrounding skin (80%). At baseline 6/33 (18.2%) SU-calc showed clear signs of infection; the bacteria involved were Staphylococcus aureus (3 cases), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (1), Staphylococcus hominis (1), and Escherichia coli (1). Systemic antibiotic therapy was required for 4/6 SU-calcs, whilst Holoil®’s application was able to control infection in 2/6 infected lesions. Additional or relapsing infections were not observed during the follow-up period.

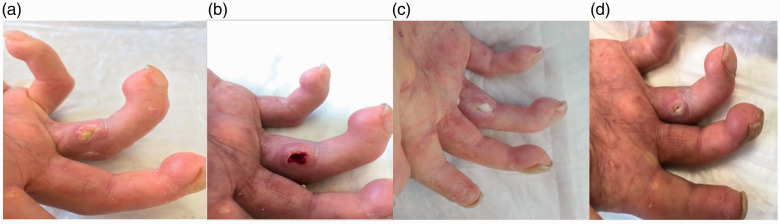

In all patients, application of Holoil® after sharp debridement either caused progressive crushing and resolution of calcium deposits or eased their sharp excision during wound care session (27/33 cases, 81.8%). Apart from the single lesion presenting as mousse calcinosis, stone calcinosis evolved to mousse deposits during Holoil® applications in another five cases, allowing their removal by applying simple pressure on the SU-calc area (total 6/33; 18%) (Figure 1a). Surgical removal was necessary in only 1/33 cases (3.0%). Overall, the diameters of SU-calcs during treatment decreased in 27/33 cases (81.8%) with formation of granulation tissue and regularization of margins, with complete healing recorded in 15/33 cases (45.4%) after a time interval of 40.1 ± 16.3 (mean ± SD) days. A significant improvement (reduction of lesion size, erythema, fibrin and calcium deposits) was observed for the remaining lesions, and no lesions relapsed during the entire follow-up period.

Figure 2 shows the activity of Holoil® on lesions over time. After an initial debridement, application of Holoil allowed the formation of mousse deposits and eased removal of the calcifications.

Figure 2.

Hand calcinosis (SU-calc) evolution following Holoil® use. In the sequence (a–d) the easy removal of calcium deposits can be observed, thanks to liquefaction induced by the medication.

Patients in the control group reported less satisfactory outcomes, with longer healing times (96.3 ± 10.7 days, mean ± SD; p < 0.0001) and frequent infectious complications requiring systemic antibiotic treatment (42.3% vs. 12.1% of treated subjects, p = 0.0146). These results suggested that patients treated with Holoil had a higher degree of protection against infections than control patients (Table 1). Prior to receiving SU-calc medication, local application of EMLA (prilocaine/lidocaine mixture) permitted good patient compliance during the entire session of debridement and dressing.20 Only one patient with particularly severe SU-calc complicated by infection received intravenous morphine to remove calcinosis.

All patients experienced a significant reduction in SU-calc-related pain (change in NRS in treated patients from baseline to the end of follow-up: 7.3 ± 1.9 to 2.9 ± 1.4 vs. control subjects: 7.5 ± 2.1 to 4.5 ± 2.4; p = 0.0124).

The analgesic demand for pain control gradually reduced over time. Opioids were required in all patients at baseline, whilst paracetamol was sufficient for pain control at the end of follow-up only in patients treated with Holoil®.

Complete adherence to treatment with Holoil® was observed for all SSc patients. Moreover, self-medications were also considered “easy to use” (score 0) in all cases.

Treatment with Holoil® was generally well tolerated, with only 2/21 patients reporting a mild burning sensation during the first Holoil® treatment that subsequently disappeared. In only one case, persistent erythema with burning and excoriation of the perilesional skin occurred, requiring Holoil® suspension.

Discussion

Cutaneous calcinosis may severely affect the quality of life of SSc patients because of the frequent complications of non-healing SU-calcs. Although frequently detectable during the course of the disease, very few data are available to inform the correct clinical assessment and management of these specific manifestations.3

Over the last two decades we evaluated the usefulness of numerous systemic and local treatment combinations adapted to different clinico-pathogenetic variants of scleroderma skin ulcers. These are regularly tailored to individual patients. The present study describes our experience with local Holoil® treatment in addition to standard of care for SU-calc. Application of Holoil® after lesion debridement3 resulted in progressive crushing of calcium deposits and allowed sharp excision of calcinosis for the large majority of SU-calcs. Interestingly, in five cases the stone calcinosis evolved to mousse deposits, making their removal easier by applying pressure on the wound area. At the end of follow-up, complete healing of the SU-calc was observed in about half of cases. Moreover, a progressive reduction of pain and analgesic demand, as well as good compliance and tolerance to the combined treatment regimen, were recorded for all patients. Compared with the Holoil® treated group, control patients treated with standard therapies showed less satisfactory outcomes, with significantly longer healing times (p < 0.0001) and a higher percentage of infectious complications.

According to previous clinical observations, SU-calcs are more frequently localized on fingertips, elbows, and/or knees, and are potentially associated with hypoxia and recurrent trauma.2,3 Pharmacological treatment to reduce calcinosis and diminish the risk of harmful SU-calcs is particularly challenging, and no efficacious therapies have been identified to date.22–24 Both mechanical25 and surgical local approaches are generally needed in cases resistant to conventional treatments, and a significant proportion of patients with large, localized, and symptomatic lesions require surgical excision. Saddic et al.26 reported an excellent clinical outcome, including decreased pain and short healing time, in one patient with scleroderma SU-calc who underwent curettage of a calcinosis on the tip of his left middle finger. However, a potential risk of surgical excision is delayed wound healing, which may lead to skin necrosis, infection, and decreased range of joint motion.

Our data confirmed the efficacy of local treatment of SU-calcs in different cutaneous disease settings when combined with Hypericum and Neem oil cream and a wound bed preparation framework.11,19 Hypericum perforatum is a plant typically known for its antidepressant properties12 which can be used in treatment of mild inflammatory dermatological diseases and even to treat skin wounds in association with traditional approaches.27 Hyperforin is the most important active substance promoting wound healing, probably thanks to its action on fibroblasts, keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation. In addition, hyperforin has antimicrobial activity, particularly against Gram-positive bacteria.28,29 Azadirachta indica, commonly known as Neem, has been proposed as a potential treatment for many infectious and metabolic disease.30 Neem oil could have anti-inflammatory properties by modulating macrophage migration and activity31. Thanks to the presence of limonoids, Neem could represent a safe tool for local treatment of acute skin toxicity in patients undergoing radiotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy for head and neck malignancies.32

In addition, Holoil® shows cicatrizing and bacteriostatic effects that contribute to wound repair.12,13

The two active components of Holoil® potentiate one another to achieve infection control, inhibition of inflammation, and induction of epithelization. Only a few reports have focused on the efficacy of Holoil® in wound healing, especially diabetic ulcers and surgical wounds, even those complicated by bone exposition.16,17 To our knowledge, no studies have examined the efficacy of Holoil® in treating SSc-related ulcers.

In our experience, Holoil® cream was particularly useful for treatment of SU-calcs, which are difficult to heal because of constant local inflammation sustained by calcium deposits and frequently complicated by infections. In the control group, Staphylococcus aureus, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Staphylococcus hominis, and Escherichia coli were detected in a significant proportion of lesions requiring antibiotic therapy. Besides their potential role in control of infections,29 Neem and Hypericum mixtures may also contribute to calcium deposit crushing, thus facilitating the removal of stones during curettage. Wound bed conditions, once deprived of the inflammatory stimulus exerted by calcinosis, rapidly improved with growing of granulation tissue, reduced fibrin, and re-epithelization of the edges. Overall, a beneficial effect of Holoil® was invariably observed to some degree in our patients, contrary to the control group. These preliminary positive effects, along with the patients’ good compliance and the low costs of treatment, suggest that Holoil® could represent an additional, promising tool in the management of difficult-to-heal SU-calcs in scleroderma patients.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Kowal-Bielecka O, Landewé R, Avouac Jet al. EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group (EUSTAR). Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuggioli D, Manfredi A, Lumetti Fet al. Scleroderma skin ulcers definition, classification and treatment strategies our experience and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 2018; 17: 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz GS, Sibbald RG, Falanga Vet al. Wound bed preparation: a systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen 2003; 11: S1–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutierrez A, Jr, Wetter DA. Calcinosis cutis in autoimmune connective tissue diseases: calcinosis cutis and connective tissue disease. Dermatol Ther 2012; 25: 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi Fet al. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002; 81: 139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferri C, Sebastiani M, Lo Monaco Aet al. Systemic sclerosis evolution of disease pathomorphosis and survival. Our experience on Italian patients' population and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 2014; 13: 1026–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valenzuela A, Baron M, Herrick ALet al. Calcinosis is associated with digital ulcers and osteoporosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: a Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016; 46: 344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amanzi L, Braschi F, Fiori Get al. Digital ulcers in scleroderma: staging, characteristics and sub-setting through observation of 1614 digital lesions. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 49: 1374–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giuggioli D, Manfredi A, Colaci Met al. Scleroderma digital ulcers complicated by infection with fecal pathogens. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011; 64: 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matucci-Cerinic M, Krieg T, Guillevin Let al. Elucidating the burden of recurrent and chronic digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: long-term results from the DUO Registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 1770–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leaper DJ, Schultz G, Carville Ket al. Extending the TIME concept: what have we learned in the past 10 years? (*). Int Wound J 2012; 9: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greeson JM, Sanford B, Monti DA. St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum): a review of the current pharmacological, toxicological, and clinical literature. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001; 153: 402–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alzohairy MA. Therapeutics role of Azadirachta indica (Neem) and their active constituents in diseases prevention and treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016; 2016: 7382506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koriem KM. Review on pharmacological and toxicological effects of oleum azadirachti oil. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2013; 3: 834–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wölfle U, Seelinger G, Schempp CM. Topical application of St. Johnʼs Wort (Hypericum perforatum). Planta Med 2014; 80: 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Läuchli S, Vannotti S, Hafner Jet al. A plant-derived wound therapeutic for cost-effective treatment of post-surgical scalp wounds with exposed bone. Forsch Komplementmed 2014; 21: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iabichella ML. The use of an extract of Hypericum perforatum and Azadirachta indica in advanced diabetic foot: an unexpected outcome. BMJ Case Rep 2013; 2013: pii: bcr2012007299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen Jet al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65: 2737–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valenzuela A, Chung L. Calcinosis: pathophysiology and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015; 27: 542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giuggioli D, Manfredi A, Vacchi Cet al. Procedural pain management in the treatment of scleroderma digital ulcers. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015; 33: 5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartoli F, Fiori G, Braschi Fet al. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis: subsets, distribution and complications. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016; 55: 1610–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galluccio F, Allanore Y, Czirjak Let al. Points to consider for skin ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017; 56: v67–v71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denton CP, Hughes M, Gak Net al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016; 55: 1906–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujimoto M, Asano Y, Ishii Tet al. The wound/burn guidelines – 4: guidelines for the management of skin ulcers associated with connective tissue disease/vasculitis. J Dermatol 2016; 43: 729–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumhardt S, Frey DP, Toniolo Met al. Safety and efficacy of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in calcinosis cutis associated with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016; 34: 177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saddic N, Miller JJ, Miller OF, 3rdet al. Surgical debridement of painful fingertip calcinosis cutis in CREST syndrome. Arch Dermatol 2009; 145: 212–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frommenwiler DA, Reich E, Sudberg Set al. St. John's wort versus counterfeit St. John's wort: an HPTLC study. J AOAC Int 2016; 99: 1204–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hostanska K, Reichling J, Bommer Set al. Hyperforin a constituent of St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.) extract induces apoptosis by triggering activation of caspases and with hypericin synergistically exerts cytotoxicity towards human malignant cell lines. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2003; 56: 121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saddiqe Z, Naeem I, Maimoona A. A review of the antibacterial activity of Hypericum perforatum L. J Ethnopharmacol 2010; 131: 511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biswas TK, Mukherjee B. Plant medicines of Indian origin for wound healing activity: a review. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2003; 2: 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alam A, Haldar S, Thulasiram HVet al. Novel anti-inflammatory activity of epoxyazadiradione against macrophage migration inhibitory factor: inhibition of tautomerase and proinflammatory activities of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 24844–24861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franco P, Potenza I, Moretto Fet al. Hypericum perforatum and neem oil for the management of acute skin toxicity in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiation or chemo-radiation: a single-arm prospective observational study. Radiat Oncol 2014; 9: 297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]