Abstract

Source-separated urine is an attractive fertilizer due to its high nutrient content, but the rapidly hydrolysis of urea leads to ammonia volatilization and other environmental problems. Urine stabilization, which meanly means preventing enzymatic urea hydrolysis, receives increasing attention. Accordingly, this study developed a technique to stabilize fresh urine by heat-activated peroxydisulfate (PDS). The effect of three crucial parameters, including temperature (55, 62.5, and 70 °C), heat-activated time (1, 2, and 3 h), and PDS concentration (10, 30, and 50 mM) that affect the activation of PDS in urine stabilization were investigated. Nitrogen in fresh urine treated with 50 mM PDS at 62.5 °C for 3 h existed mainly in the form of urea for more than 22 days at 25 °C. Moreover, the stabilized urine could remain stable and resist second contamination by continuous and slow pH decrease due to PDS decomposition during storage. Less than 8% of nitrogen loss in stabilized urine was detected during the experiment. The investigation of nitrogen transformation pathway demonstrated that urea was decomposed into NH4+ by heat-activated PDS and further oxidized to NO2− and NO3−. The nitrogen loss during treatment occurred via heat-driven ammonia volatilization and N2 emission produced by synproportionation of NO2− and NH4+ under acid and thermal conditions. Overall, this study investigated an efficient approach of urine stabilization to improve urine utilization in terms of nutrient recovery.

Keywords: Urine stabilization, Heat-activated peroxydisulfate, Nitrogen loss, Nitrogen transformation pathway

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Heat-activated peroxodisulfate stabilizes source-separated urine for more than 22 days without urea hydrolysis.

-

•

Activated temperature and peroxydisulfate concentration are vital for urine stabilization.

-

•

Less than 8% nitrogen loss in stabilized urine within 22 days of storage

-

•

Nitrogen transformation pathway in heat-activated peroxydisulfate treatment was investigated.

1. Introduction

The human urine, with low hazardous chemical compounds and heavy metals (Li et al., 2019), contains nutrients needed by plant life and is considered a potential fertilizer (Heinonen-Tanski and van Wijk-Sijbesma, 2005). Approximately 90% of nitrogen, 60%–65% of phosphorus, and 50%–80% of potassium in the human excreta are present in urine (Simha and Ganesapillai, 2017), but less than 15% of nitrogen from human excreta is recycled (Trimmer et al., 2019). In fresh urine, nearly 85% of nitrogen is fixed as urea (Udert et al., 2006), which is regarded as attractive plant fertilizer. However, urea can be hydrolyzed rapidly 1014 times faster than noncatalyzed condition (Qin and Cabral, 2009) in the presence of urease, which causes ammonia volatilization, odor emission, and scaling of pipe or devices in urine collection and nutrient recovery system. Therefore, urine stabilization by preventing enzymatic urease hydrolysis is an efficient way to alleviate the above problems and improve nutrients recovery by keeping nitrogen in stable forms (Randall et al., 2016).

Various methods, such as acidification or alkalization (Hellström et al., 1999; Senecal and Vinneras, 2017; Simha et al., 2020), electrochemically induced precipitation (De Paepe et al., 2020), nitrification (Udert and Wachter, 2012), Ca(OH)2 addition (Randall et al., 2016), hydrogen peroxide-induced inactivation of urease (Krajewska, 2011), thermal treatment (Zhou et al., 2017), and urease inhibitor addition (Kafarski and Talma, 2018), have been investigated to stabilize urine. Nevertheless, most urease inhibitors show low efficiency in real urine because of complex composition of urine. For instance, once ionic metal precipitates in inhibitors are formed, and phosphate/chloride becomes present in urine, ionic metals cannot destroy the active sites of urease, indicating that urease cannot be inhibited effectively (Ray et al., 2018). Excessive pH modification results in an extremely high (>12.0, (Randall et al., 2016)) or extremely low pH (<4.0, (Andreev et al., 2017)) of the product, which requires large dosage of acid and base. Hydrogen peroxide works effectively on urease inhibition, but it cannot prevent second contamination of urease or urease-producing microorganisms (Krajewska, 2011).

Sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have attracted attention in urine treatment because of the high redox potential and long lifetime of sulfate radicals. Peroxydisulfate (PDS) activated by ultraviolet light (UV) was applied to degrade pharmaceuticals (Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016b) and sulfonamide antibiotics (Zhang et al., 2016a) in synthetic source-separated urine. Zhang et al. (2020) indicated that biochar-activated PDS effectively removes pharmaceuticals and metabolites in urine. Sulfate radical-based AOPs are also effective for the inactivation of microorganisms in wastewater (Popova et al., 2019). However, thus far, sulfate radical-based AOPs have only been used for pharmaceutical and antibiotic elimination in urine but not for urine stabilization. Hydroxyl radicals and H2O2 can destroy the thiol groups of cysteinyl residues in the active site of urease, thereby inactivating urease (Krajewska, 2011). Therefore, sulfate radicals produced by sulfate radical-based AOPs may be an alternative and potential way to inactivate urease.

PDS can produce sulfate radicals by O—O bond cleavage, and its bond energy is 140 kJ/mol (Flanagan et al., 1984). Heating, UV light, alkali, and metal catalysis are effective ways that provide energy for bond cleavage (Moreno-Andres et al., 2019). Particularly, activation by heating and UV yield two moles of sulfate radicals (SO4∙−) for each mole of PDS, which is twice as much as that from metal catalysis (Eqs. (1), (2)) (Ike et al., 2018; Wang and Wang, 2018).

| (1) |

| (2) |

Given the limited penetration of UV light in urine and undesired excess alkali in application (Matzek and Carter, 2016), the application of heat-activated PDS for urease inactivation may have the following advantages: a) The color and complex solution of urine have less effect on heat-activated process. b) The process requires no addition of new substances. The PDS activation products are SO42−, Na+, and H+, which are already present in urine. c) The hydrogen ions generated from the decomposition of PDS can decrease urine pH properly, may contribute to inhibit urease and prevent the second contamination. d) The transportation, storage, and use of reagent are safer than those of acids and bases. e) Sulfate radicals have a longer lifetime and higher redox potential (E°[SO4∙−/SO42−] = 2.5–3.1 V, (Zhang et al., 2015)) than hydroxyl radicals (E°[•OH/H2O] = 1.9–2.7 V, (Zhang et al., 2016b) and have stronger oxidizability to urease.

The energy input by high temperature causes O—O bond cleavage (Wang and Wang, 2018). Normally, at a modest temperature of 40 °C, PDS can be activated for pollutant degradation (Ike et al., 2018). Given the urine is a complex solution, the activated temperature was set at 55–70 °C to improve efficiency. The pollutant removal rates increases as the initial concentration of PDS increases, because it increases the concentration of SO4∙− (Luo et al., 2020). Therefore, this study mainly aimed to investigate the urine stabilization by heat-activated PDS at different temperatures (55, 62.5, and 70 °C), PDS concentrations (10, 30, and 50 mM), and heat-activated times (1, 2, and 3 h); evaluate its efficiency and stability; and identify the nitrogen transformation pathway in the process.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Fresh urine samples

The fresh urine used in this paper was collected using the plastic tank from the urinal on the 12th floor of Tumu Teaching and Office Building, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing. The main parameters of fresh urine samples were analyzed within 1 h after collection (Table 1). To ensure that the urine samples had strong hydrolysis, we split each fresh urine sample into two portions for the experiments and for urea hydrolysis measurement. The latter were stored at 25 °C for 1 day. More than 70% urea was hydrolyzed in 1 day, indicating that the urine samples had strong hydrolysis capacity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition of fresh urine samples and the urine samples stored at 25 °C for 1 day.

| Fresh urine |

One-day stored urine |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | U2 | U3 | U4 | U5 | U1 | U2 | U3 | U4 | U5 | |

| TN (mg-N/L) | 4900 ± 430 | 3000 ± 400 | 6000 ± 450 | 3400 ± 430 | 4700 ± 290 | 4900 ± 430 | 3000 ± 400 | 6000 ± 450 | 3400 ± 430 | 4700 ± 290 |

| TAN (mg-N/L) | 800 ± 190 | 250 ± 62 | 650 ± 150 | 910 ± 250 | 490 ± 140 | 3900 ± 290 | 2800 ± 270 | 5900 ± 360 | 3200 ± 220 | 3900 ± 230 |

| TAN/TN | 16.30 ± 2.47% | 8.33 ± 0.98% | 10.83 ± 1.70% | 26.76 ± 4.04% | 10.40 ± 2.35% | 79.59 ± 1.08% | 93.33 ± 3.52% | 98.33 ± 1.38% | 94.10 ± 5.54% | 82.98 ± 0.23% |

| pH | 7.29 ± 0.23 | 7.25 ± 0.11 | 7.30 ± 0.12 | 7.87 ± 0.21 | 7.51 ± 0.15 | 9.21 ± 0.10 | 9.25 ± 0.17 | 9.32 ± 0.25 | 9.13 ± 0.18 | 9.26 ± 0.05 |

2.2. Experimental set up

2.2.1. Urine stabilization with heat-activated PDS

The effect of different concentrations (10, 30, and 50 mM) of PDS (Na2S2O8, 98%; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China), temperatures (55 °C, 62.5 °C, and 70 °C), and heat-activated times (1, 2, and 3 h) on urine stabilization were separately evaluated (Fig. 1a). Fresh urine (250 mL each) was added to glass bottles that were sterilized at 105 °C for 30 min in advance by using an autoclave. Then, the PDS was added to the sterilized bottles, and all the samples were quickly moved to a water bath to start the treatment. Heating and magnetic stirring (150 r/min) of urine were carried out in the water bath (Jintan Ronghua Instrument Manufacture Co., Ltd., China.). All the glass bottles were sealed to reduce ammonia vaporization and leakage because of heating. Each bottle was transferred to the ice bath immediately after treatment to stop the activation.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the experiments. (a) urine treatment by heat-activated PDS, (b) urine treatment by heating, and (c) urea treatment by heat-activated PDS.

To estimate the stabilization duration, we kept the treated urine in sealed bottles in an incubator at 25 °C. The pH and total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) of treated urine were monitored daily until the end of experiments. The concentrations of the residual PDS in the treated urine were tested on the 1st, 10th, and 20th day to assess the influence of residual PDS during storage. The storage temperature of 25 °C was selected because of the following reasons: a) in general, the normal ambient temperature is 25 °C, b) PDS has a long half-life at 25 °C, and its self-decomposition occurs slowly (Zrinyi and Pham, 2017); and c) the activity of microorganisms and urease are unaffected at 25 °C.

2.2.2. Urine stabilization by heating

Given that urease can be inactivated at high temperature (Illeova, 2003), the urine stabilization at 55–70 °C needs to be evaluated. Fresh urine samples (U3, U4, and U5 in Table 1) in sealed glass bottles (150 mL each) were heated in the water bath for 1–3 h at 55–70 °C (Fig. 1b). After treatment, all the samples were cooled to room temperature instantly with ice water to stop the treatment. To monitor the residual hydrolysis capacity of treated urine, we kept the urine samples in an incubator at 25 °C, and TAN was measured during storage. Untreated fresh urine was stored in the same condition as a control.

2.2.3. Non-enzymatic decomposition of urea by heat-activated PDS

Urea decomposition by heat-activated PDS was studied to clarify the nitrogen transformation pathway. Urea solution (1000 mg-N/L), as the sole substrate of heat-activated PDS, was reacted with 50 mM PDS between 55 and 70 °C for 3 h (Fig. 1c). All the samples were heated in water bath with magnetic stirring (150 r/min). The concentrations of urea, nitrate and nitrite, and ammonium were monitored every 30 min. Considering that the urea concentration cannot be tested directly, and urea is the only organic nitrogen source in the solution, the urea concentration can be regarded as the difference between total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN) and ammonium.

2.3. Sampling and analytic methods

Urine samples were filtered through 0.45 μm syringe filters before analysis. All the samples were analyzed immediately or stored at 4 °C in the refrigerator if the analysis cannot be completed in time. All the experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure accuracy. TAN and TKN were measured using the Distillation Unit K-350 (BÜCHI Company, Switzerland). The pH was tested using the pH detector (HACH Company, America). The total nitrogen was analyzed using HACH test tubes (DR, N10071, HACH Company, America). PDS concentration test was carried out using the modified iodometric titration method by Liang et al. (2008).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Fresh urine stabilization with heat-activated PDS

In this experiment, the urea hydrolysis of all urine samples without intervention was monitored. Nearly 90% of urea in fresh urine was hydrolyzed within 1 day during storage at 25 °C (Table 1). Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 show the effects of PDS concentration, heat-activated time, and temperature on urine stabilization respectively. The findings demonstrate that the heat-activated PDS can effectively inhibit urea hydrolysis and stabilize real fresh urine for 22 days under proper conditions.

Fig. 2.

Total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) (a) and pH (b) of fresh urine treated with different PDS concentrations during treatment and storage (25 °C). All the urine samples were treated at 62.5 °C for 3 h. The −1 and 0 on the abscissa represent fresh urine before and after PDS treatment, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) (a) and pH (b) of fresh urine treated with different heat-activated times during treatment and storage (25 °C). All the urine samples were treated at 62.5 °C with 50 mM of PDS. The −1 and 0 on the abscissa represent fresh urine before and after PDS treatment, respectively.

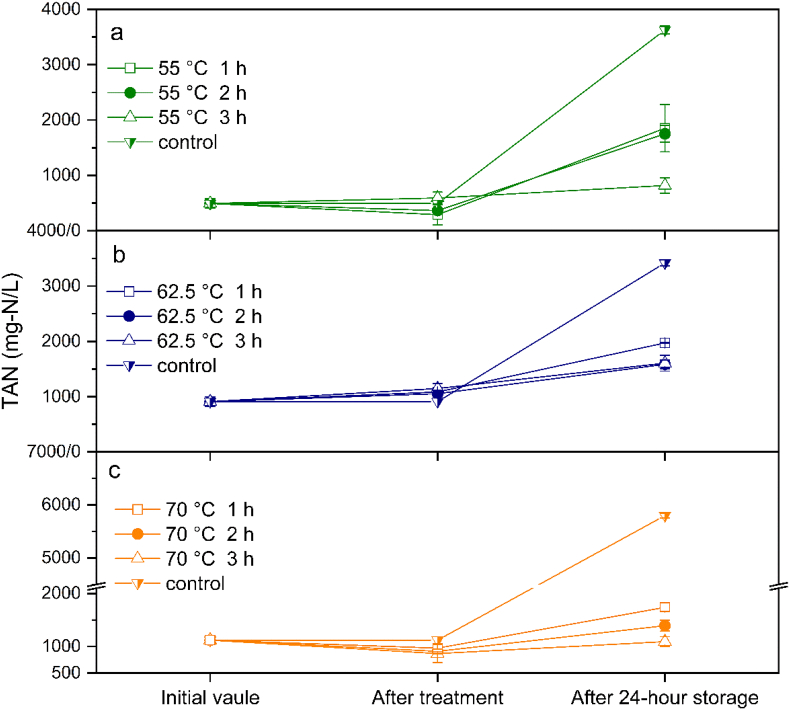

Fig. 4.

Total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) (a) and pH (b) of fresh urine treated with different activation temperatures during treatment and storage (25 °C). All the urine samples were treated with 50 mM of PDS for 3 h. The −1 and 0 on the abscissa axis represent fresh urine before treatment and the urine after PDS treatment, respectively.

3.1.1. Effect of PDS concentration

Fig. 2 presents the pH and TAN of treated urine during storage under different PDS concentrations. The concentration of PDS strongly affected urine stabilization. The fresh urine treated with 50 mM PDS prevented urea hydrolysis for 22 days, whereas those with 30 and 10 mM PDS prevented urea hydrolysis for 7 and 3 days, respectively. The hydrolysis rate during storage decreased with the increase in dosage of PDS. The increase in TAN from 750 mg-N/L to 2500 mg-N/L was achieved within 1 day for urine with 10 mM PDS and 4 days for urine treated with 30 mM PDS. High PDS concentration provided more reactants to generate SO4∙−, which is responsible for reducing hydrolysis.

The variation in pH was dependent on the urea hydrolysis and PDS decomposition; the former promoted the increase in pH (Eq. (3)), whereas the latter led to the decrease in pH (Eqs. (1), (4)) (Matzek and Carter, 2016). In Fig. 2b, the pH of urine samples substantially decreased with PDS treatment, except for that treated with 10 mM PDS, and this process was largely dependent on the PDS concentration. The significant drop in pH after PDS treatment confirmed the activation of PDS. However, the slight pH increase in urine treated with 10 mM PDS indicates that the OH− produced by urea decomposition exceeded the H+ produced by PDS decomposition. In this system, urea decomposition was possibly caused by enzymatic decomposition by urease and non-enzymatic decomposition by SO4∙−. This topic is further discussed in Section 3.3.

| (3) |

| (4) |

During storage, the pH of the stabilized urine (urine with 50 mM PDS) decreased slowly, whereas that of the unstabilized urine increased rapidly. The increase in pH indicates that the urine hydrolysis still occurred in the unstabilized urine. Similarly, urine hydrolysis was completely inhibited in the stabilized urine, and the pH stopped increasing. The slow decline of pH suggests that PDS was decomposed slowly during storage, and this finding is discussed in Section 3.2.

3.1.2. Effect of heat-activated time

The heat-activated time had a significant effect on urine stabilization. As shown in Fig. 3a, after 3 h of stabilization at 65 °C, fresh urine was completely stabilized, and urea hydrolysis can be neglected during storage. Meanwhile, the TAN of urine samples treated for 1 and 2 h consistently increased during storage and were hydrolyzed completely after 8 and 14 days, respectively. The long reaction time contributed to the sustainability of urine stabilization, because long heat-activated time promoted the activation of PDS and generated substantial free radicals, as indicated by the pH change in Fig. 3b. The long heat-activated time (3 h) induced a steep drop in pH, and the pH decreased from 7.25 to 4.74, indicating that a large amount of PDS was activated with long heat-activated time (Eq. (1)).

For the urine samples stored at 25 °C, the increase in pH coincided with ammonium generation, but it reached a peak earlier than TAN. Notably, the pH of urine treated for 2 h stopped increasing on day 5, whereas its TAN stopped increasing on day 14. The relationship between hydrolyzed fraction and pH of fresh urine has been studied, and it demonstrates that pH is proportional to the ratio of TAN until 50% hydrolysis is reached; further hydrolysis causes no increase in pH (Hellström et al., 1999). In the present study, the fraction exceeded 50%. For example, the pH and TAN of urine (treated with 10 and 30 mM PDS) stopped increasing almost simultaneously (Fig. 2b). This phenomenon occurred, because the H+ produced by PDS decomposition reduced the alkalinity, thus allowing the pH to reach the peak later.

3.1.3. Effect of temperature

Fig. 4 shows the TAN and pH variation of urine samples, which were treated with 50 mM PDS for 3 h at 55–70 °C, during treatment and storage. The urine samples treated at 70 °C and 62.5 °C remained stable for at least 22 days. The nitrogen loss of stabilized urine was less than 8% after 22 days of storage (Table S1). Hydrolysis rate was reduced significantly compared with the control one in Table 1, and the complete hydrolysis of urea in urine treated at 55 °C required 19 days of storage. High temperature could improve urine stabilization effectively. The fission of O—O bond, which is the critical structure of PDS, is essential for PDS activation to produce sulfate radicals. High temperature provided energy for the thermal hemolytic cleavage of the O—O bond, thereby generating sulfate radicals, which promoted urease inhibition effectively (Ike et al., 2018). The rate constant of PDS activation at pH = 1.3 ranges from 6.12 × 10−6 min−1 at 25 °C to 3.4 × 10−3 min−1 at 70 °C (House, 1962). In addition, heating can inactivate enzyme directly, because the native structure of urease can be damaged at high temperature. The residual activity of urease in raw soybean could be reduced to 0.55% at 100 °C during dry extrusion (Žilić et al., 2012). Illeova (2003) found that jack bean urease required 41 h to lose all activity at 62.5 °C and 8 h at 70 °C. Zhou et al. (2017) indicated that fresh urine required at least 3 days of heating at 70 °C to be stabilized. Therefore, the effect of heating on urine stabilization in this study should be evaluated.

Fig. 5 shows the stabilization of fresh urine at different temperatures and exposure times. TAN was monitored in an exposure process to record the urease activity during heating. The ammonia volatilization at high temperature caused the TAN to decrease slightly after treating at 55 °C and 70 °C. The urine pH increased to 7.9–8.9 after heating (Fig. S1), and this condition could enhance ammonia volatilization. However, unlike the urine treated at 55 °C and 70 °C, the TAN of urine slightly increased after treatment at 62.5 °C, indicating that urea hydrolysis remained even at high temperature, especially at 62.5 °C. Previous kinetic studies on jack bean urease indicated that the optimum temperature of free jack bean urease is 45–65 °C (Arica, 2000; Krajewska et al., 1990; Qin and Cabral, 1994). After 24 h of storage, the TAN of urine treated at 62.5 °C for 1 h increased to 1971.3 mg-N/L, whereas the TAN of urine treated for 3 h increased to 1607.6 mg-N/L, indicating that the long exposure time at high temperature could reduce urease activity. Although 45–65 °C is the optimal temperature for urea hydrolysis, the half-life of urease decreases at high temperature. Krajewska et al. (1990) explained that the half-life of jack bean urease was 120 min and 110 h at 70 °C and 25 °C, respectively. Arica (2000) found that the residual activity of jack bean urease decreased to less than 20% after 120 min or 60 min of exposure at 55 °C and 62.5 °C, respectively. In other words, the native structure of urease is unstable at high temperature even though it is the optimum temperature for urease (Geinzer, 2017).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) of fresh urine treated at 55–70 °C at different exposure times. The treated urine stored at 25 °C for 24 h.

With 3 h of thermal treatment at 70 °C, the TAN of urine increased from 867.6 mg-N/L to 1094.1 mg-N/L (Fig. 5), and urine pH increased to 8.76 (Fig. S1) after 24 h of storage, indicating that it was insufficient for the complete urease inactivation. Urease could only be inactivated reversibly at a temperature < 80 °C (Geinzer, 2017). Illeova (2003) concluded that the reversible denaturation of native form and the irreversible association of the denatured and native forms are the key steps in urease thermal inactivation. In the present study, enzyme denaturation at high temperature and SO4∙− caused urease inactivation, and SO4∙− was the main reason for irreversible inactivation of urease.

3.2. PDS decomposition of stabilized urine during storage

During treatment, PDS decomposition was dependent on activation conditions which provided energy for O—O bond cleavage in heat-activated PDS (Fig. 6). More than 58.00% of PDS was activated at 70 °C, whereas only 26.64% of PDS was activated at 55 °C. The high activated temperature improved the velocity constant (k0) of PDS decomposition significantly. The k0 is 4.13 × 10−4 min−1 to 5.2 × 10−4 min−1 at 60 °C, and increased to 1.6 × 10−3 min−1 to 2.01 × 10−3 min−1 and 5.4 × 10−3 min−1 at 70 °C and 80 °C, respectively (House, 1962). The heat activated time showed a slight promotion on PDS activation. However, the residual PDS in urine treated at 3 h was slightly higher than that at 2 h after treatment. Because the pH of urine treated at 2 h (pH = 7.58–6.59) was always higher than that at 3 h (pH = 7.25–4.74) from the beginning to the end of treatment (Fig. 3b). The high concentration of hydroxide in urine could promote the activation of PDS. At the same activation temperature and time, more PDS was activated in samples with high concentrations of PDS. For example, 5.21, 10.32, and 13.39 mM of PDS were activated in samples with PDS concentration of 10, 30, and 50 mM, respectively. Although the use efficiency of PDS in samples with high PDS concentration decreased, the amount of PDS involved in the activation increased. A large amount of sulfate radicals was generated with high PDS decomposition, thereby enhancing urine stabilization. This finding confirmed that the oxidation of SO4∙− produced by PDS mainly caused urine stabilization.

Fig. 6.

Residual PDS concentration during treatment and storage. All the samples were stored at 25 °C after treatment.

The pH of stabilized urine dropped slowly during storage (Figs. 2b–4b), thereby indicating the occurrence of acid-producing reaction. In addition to being decomposed during heating, PDS was decomposed slowly at room temperature (Huang et al., 2005). PDS had a slow decomposition during storage at 25 °C, thereby lowering the pH of urine. The PDS decomposition rate during storage strongly depended on the pH of urine. In Fig. 6a, during the 20 days of storage, the consumption of PDS in urine treated at 55 °C (15.61 mM) was 7.50 times higher than that in urine treated at 70 °C (2.08 mM). Because urine treated at 55 °C had higher pH (> 8.5) in storage than that at 70 °C (pH < 5). Analogously, during the 20 days of storage, the PDS consumption in urine treated for 1 h was 6.07 times higher than that treated for 3 h, because the former had higher pH (> 7) in storage than the latter (pH < 5) (Fig. 6b). The PDS molecule could be catalyzed by OH− and formed the hydroperoxide (HO2−) intermediate, which generated SO4∙− by reacting with another PDS molecule (Eqs. (5), (6)) (Ike et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2017; Matzek and Carter, 2016).

| (5) |

| (6) |

During storage, H+ had two reactions, namely, the production of H+ by PDS decomposition (Eq. (4)) and consumption of H+ by urea hydrolysis (Eq. (3)). Although the decrease in pH caused by the decomposition of PDS did not neutralize the increased pH caused by the hydrolysis of urea in unstabilized urine, a low pH should be maintained in stabilized urine, because enzyme process normally relies on temperature, as well as on pH. The optimal pH of hydrolysis for jack bean urease ranges from 5.5 to 7.2 (Eremeev et al., 1999; Qin and Cabral, 1994). Analogously, urease purified from Arthrobacter oxydans had the highest enzymatic activity at pH 7.6 (Schneider and Kaltwasser, 1984). Binuclear nickel center, which was an important structure regarded as the active site of all bacterial urease (Ray et al., 2018), could be damaged at pH < 5 because of the irreversible removal of nickel (Schneider and Kaltwasser, 1984). The decrease in pH (<5) via PDS decomposition at room temperature could destroy the structure of the urease produced during storage, thereby maintaining urine stabilization. This condition also provides urine with resistance against second contamination, indicating that urine would not be contaminated and hydrolyzed during transportation or moved to the next treatment process. However, if the urine was not completely stabilized by heat-activated PDS or the urine pH was higher than 5.0 after treatment, the urea could not remain stable in urine. The reason was that PDS decomposed slowly at room temperature, and it could not provide enough SO4∙− and H+ to inactivate residual urease and prevent second contamination.

3.3. Nitrogen transformation pathway

3.3.1. Urea non-enzymatic decomposition by heat-activated PDS

Non-enzymatic urea decomposition occurred during treatment and was positively correlated with temperature (Fig. 7). Nearly 23.76% of urea was decomposed by PDS at 70 °C, and this proportion was 4.6 times than that at 62.5 °C. At 55 °C, heat-activated PDS had slight promotion on urea non-enzymatic decomposition. Randall et al. (2016) reported that the non-enzymatic decomposition of urea was strongly dependent on temperature. The half-life of urea ranged from 59 days to 14 days at 50 °C and 66 °C and several hours at 100 °C. Considering that the temperature involved in this study had weak contribution on urea rapid hydrolysis, the free radicals mainly caused the non-enzymatic decomposition of urea instead of high temperature.

Fig. 7.

Non-enzymatic decomposition of urea with 50 mM PDS at 55–70 °C.

The variations of urea and ammonium could be matched roughly, and the ammonium concentration showed an inverse proportion with urea. It could be speculated that ammonium was the main product of non-enzymatic urea decomposition. However, Choi et al. reported that urea could also be oxidized into NO3− via one step by PDS with UV irradiation (Choi and Chung, 2019). Schranck and Doudrick (2020) indicated that NO3− formed in urea solution at boron-doped diamond anode. The main reason for the discrepancy is that aside from to free radicals, electrical and ultraviolet stimulation were also crucial requirements in previous studies, and these conditions promoted the one-step oxidation of urea to NO3−.

Nitrate first increased and then decreased slowly, indicating that nitrate was generated and transformed subsequently (Fig. 7). Although the one-step oxidation of urea to NO3− was not determined in this study, NO3− could be obtained by the oxidation of ammonia through the following steps. Hydroxyl radicals (•OH) could oxidize NH3 to •NH2, which could then be oxidized to •NHOH rapidly (Eqs. (7), (8), (9)). •NHOH could be oxidized further to unstabilized NH2O2− and split to NO2− (Huang et al., 2008). NO2− would be oxidized to NO3− under oxidizing condition.

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Considerable amounts of H+ were generated by PDS activation, thereby causing the pH to decrease below 3.0. The nitrite in aqueous acid could react with NH4+ to form N2 (Eq. (10)). The hydrogen ion and high temperature promoted this process significantly, thereby reducing nitrate after 0.5 h (Nguyen et al., 2003). However, the pH remained above 5.0 in real urine because of buffer counterion (e.g., HCO3−), which reduced the production of N2.

3.3.2. Nitrogen loss

In addition to N2 generation, ammonia loss was found in the real urine stabilization with PDS, especially in urine treated at 70 °C (Fig. 4a). Total ammonia was observed in the aqueous solution in two forms, namely, un-ionized ammonia (NH3) and ammonium ion (NH4+) (Korner et al., 2001). The relative concentrations of the two forms are strongly dependent on pH and temperature. High temperature increases the fraction of un-ionized ammonia in aqueous solution significantly (Fig. S2). The un-ionized ammonia is in equilibrium with ammonia gas. According to Henry's Law (Eq. S5), the increase in un-ionized ammonia in aqueous solution promotes ammonia gas volatilization. Therefore, in addition to N2, ammonia volatilization driven by high temperature was another reason for nitrogen loss during heat-activated PDS treatment.

During storage at 25 °C, ammonia volatilization driven by high temperature was reduced. The pH of unstabilized urine increased to 8.0–9.0 and that of stabilized urine remained at 4.0–5.0. The fraction of un-ionized ammonia in aqueous solution increases with pH (Fig. S2). Considering the high pH, ammonia was more volatile in unstabilized urine than in stabilized urine. Therefore, ammonia volatilization driven by high pH was the main reason for nitrogen loss in unstabilized urine. As for stabilized urine, ammonia volatilization was reduced because of the low urine pH.

Fig. 8 shows the main nitrogen loss of urine during PDS treatment and storage. Temperature was the crucial factor of nitrogen loss during treatment, thereby affecting the transformation path of nitrogen. During heat-activated PDS treatment, urea could be decomposed by PDS and produce NH4+ and NO3− further. Meanwhile, N2 was generated by the synproportionation of NO2− and NH4+, which lead to nitrogen loss during treatment. Another source of nitrogen loss during treatment was ammonia volatilization driven by high temperature. As for stored urine, ammonia volatilization driven by high pH was the major source of nitrogen loss in unstabilized urine (pH > 8.0). However, the pH of stabilized urine remained below 5.0, thereby reducing nitrogen loss significantly.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of nitrogen path in urine.

4. Conclusion

This paper evaluated heat-activated PDS as a novel and efficient approach for urine stabilization experimentally in the laboratory scale. Fresh human urine could be stabilized for more than 22 days with free radicals produced by PDS, and it was more efficient than urine stabilization only by heating. The activation conditions, such as high temperature, high PDS concentration and long heat-activated time, provided high energy for the O—O bond cleavage of PDS, which could accelerate the free radical production and urease inactivation further. After 22 days of storage, less than 8% of nitrogen was lost in stabilized urine with heat-activated PDS treatment. During heat-activated treatment, the nitrogen loss has two forms, namely, ammonia volatilization driven by high temperature and N2 production by the synproportionation of NO2− and NH4+. Ammonia volatilization driven by high pH was the main cause of nitrogen loss in unstabilized urine during storage. As for stabilized urine, the pH remained below 5.0, which could reduce the ammonia volatilization significantly during storage. Furthermore, the low pH (< 5.0) of stabilized urine could resist second contamination. This method is suggested as a pre-treatment step for urea recovery from fresh urine for the following reasons: a) high efficiency and short heating time, b) low nitrogen loss, and c) persistent stability and potential resistance of second contamination. Future study needs to focus on the mechanism of urease inactivation with heat-activated PDS.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yaping Lv: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Zifu Li: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing. Xiaoqin Zhou: Data curation, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Shikun Cheng: Visualization, Writing - review & editing. Lei Zheng: Visualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the project support of the National Key Research and Development Program (2017YFC0403401 and 2019YFC0408700), Natural Science Foundation of China (51808036), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (FRF-DF-19-005), as well as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Research Development and technical assistance to RTTC-China Project (OPP1161151) & Reinvent the Toilet China Project: Innovative Toilet Solutions and Commercial Activities (OPP1157726)).

This study was also supported by the Beijing Key Laboratory of Resource-oriented Treatment of Industrial Pollutants, International Science and Technology Cooperation Base for Environmental and Energy Technology of MOST.

Editor: Huu Hao Ngo

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142213.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Andreev N., Ronteltap M., Boincean B. Lactic acid fermentation of human urine to improve its fertilizing value and reduce odour emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2017;198(Pt 1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arica M.Y. Epoxy-derived pHEMA membrane for use bioactive macromolecules immobilization: covalently bound urease in a continuous model system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000;77(9):2000–2008. doi: 10.1002/1097-4628(20000829)77:9<2000::AID-APP16>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J., Chung J. Evaluation of urea removal by persulfate with UV irradiation in an ultrapure water production system. Water Res. 2019;158:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe J., De Pryck L., Verliefde A.R.D. Electrochemically induced precipitation enables fresh urine stabilization and facilitates source separation. Environmental Science & Technology. 2020;54(6):3618–3627. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b06804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremeev N.L., Kukhtin A.V., Belyaeva E.A. Effect of thermosensitive matrix-phase transition on urease-catalyzed urea hydrolysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1999;76(1):45–55. doi: 10.1385/ABAB:76:1:45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan J., Griffith W.P., Skapski A.C. The active principle of Caro’s acid, HSO5–: X-ray crystal structure of KHSO5·H2O. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1984;(23):1574–1575. doi: 10.1039/C39840001574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geinzer M. Inactivation of the urease enzyme by heat and alkaline pH treatment retaining urea-nitrogen in urine for fertilizer use. 2017. https://stud.epsilon.slu.se/11230/ (Master's thesi). Retrieved from.

- Heinonen-Tanski H., Van Wijk-Sijbesma C. Human excreta for plant production. Bioresour. Technol. 2005;96(4):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2003.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström D., Johansson E., Grennberg K. Storage of human urine: acidification as a method to inhibit decomposition of urea. Ecol. Eng. 1999;12(3–4):253–269. doi: 10.1016/S0925-8574(98)00074-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- House D.A. Kinetics and mechanism of oxidations by peroxydisulfate. Chem. Rev. 1962;62(3):185–203. doi: 10.1021/cr60217a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K.C., Zhao Z., Hoag G.E. Degradation of volatile organic compounds with thermally activated persulfate oxidation. Chemosphere. 2005;61(4):551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Li L., Dong W. Removal of ammonia by OH radical in aqueous phase. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008;42(21):8070–8075. doi: 10.1021/es8008216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ike I.A., Linden K.G., Orbell J.D. Critical review of the science and sustainability of persulphate advanced oxidation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;338:651–669. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.01.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Illeova V. Experimental modelling of thermal inactivation of urease. J. Biotechnol. 2003;105(3):235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafarski P., Talma M. Recent advances in design of new urease inhibitors: a review. J. Adv. Res. 2018;13:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner S., Das S.K., Veenstra S. The effect of pH variation at the ammonium/ammonia equilibrium in wastewater and its toxicity to Lemna gibba. Aquat. Bot. 2001;71(1):0–78. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3770(01)00158-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krajewska B. Hydrogen peroxide-induced inactivation of urease: mechanism, kinetics and inhibitory potency. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2011;68(3–4):262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krajewska B., Leszko M., Zaborska W. Urease immobilized on chitosan membrane: preparation and properties. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1990;48(3):337–350. doi: 10.1002/jctb.280480309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Boiarkina I., Yu W. Phosphorous recovery through struvite crystallization: challenges for future design. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;648:1244–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Huang C.F., Mohanty N. A rapid spectrophotometric determination of persulfate anion in ISCO. Chemosphere. 2008;73(9):1540–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C., Wu D., Gan L. Oxidation of Congo red by thermally activated persulfate process: kinetics and transformation pathway. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020;244 doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2020.116839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Li H., Chi L. Changes in activation energy and kinetics of heat-activated persulfate oxidation of phenol in response to changes in pH and temperature. Chemosphere. 2017;189:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzek L.W., Carter K.E. Activated persulfate for organic chemical degradation: a review. Chemosphere. 2016;151:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Andres J., Rios Quintero R., Acevedo-Merino A. Disinfection performance using a UV/persulfate system: effects derived from different aqueous matrices. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 2019;18(4):878–883. doi: 10.1039/c8pp00304a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D.A., Iwaniw M.A., Fogler H.S. Kinetics and mechanism of the reaction between ammonium and nitrite ions: experimental and theoretical studies. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2003;58(19):4351–4362. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2509(03)00317-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Popova S., Matafonova G., Batoev V. Simultaneous atrazine degradation and E. coli inactivation by UV/S2O8(2-)/Fe(2+) process under KrCl excilamp (222nm) irradiation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019;169:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Cabral J.M.S. Kinetic studies of the urease-catalyzed hydrolysis of urea in a buffer-free system. Applied Biochemistry & Biotechnology. 1994;49(3):217–240. doi: 10.1007/BF02783059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Cabral J.M.S. Review properties and applications of urease. Biocatalysis and Biotransformation. 2009;20(1):1–14. doi: 10.1080/10242420210154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randall D.G., Krahenbuhl M., Kopping I. A novel approach for stabilizing fresh urine by calcium hydroxide addition. Water Res. 2016;95:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray H., Saetta D., Boyer T.H. Characterization of urea hydrolysis in fresh human urine and inhibition by chemical addition. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology. 2018;4(1):87–98. doi: 10.1039/c7ew00271h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J., Kaltwasser H. Urease from Arthrobacter oxydans, a nickel-containing enzyme. Arch. Microbiol. 1984;139(4):355–360. doi: 10.1007/bf00408379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schranck A., Doudrick K. Effect of reactor configuration on the kinetics and nitrogen byproduct selectivity of urea electrolysis using a boron doped diamond electrode. Water Res. 2020;168 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senecal J., Vinneras B. Urea stabilisation and concentration for urine-diverting dry toilets: urine dehydration in ash. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;586:650–657. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simha P., Ganesapillai M. Ecological sanitation and nutrient recovery from human urine: how far have we come? A review. Sustainable Environment Research. 2017;27(3):107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.serj.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simha P., Lalander C., Nordin A. Alkaline dehydration of source-separated fresh human urine: preliminary insights into using different dehydration temperature and media. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;733 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimmer J.T., Margenot A.J., Cusick R.D. Aligning product chemistry and soil context for agronomic reuse of human-derived resources. Environmental Science & Technology. 2019 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b00504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udert K.M., Larsen T.A., Gujer W. Fate of major compounds in source-separated urine. Water Sci. Technol. 2006;54(11-12):413–420. doi: 10.2166/wst.2006.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udert K.M., Wachter M. Complete nutrient recovery from source-separated urine by nitrification and distillation. Water Res. 2012;46(2):453–464. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wang S. Activation of persulfate (PS) and peroxymonosulfate (PMS) and application for the degradation of emerging contaminants. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;334:1502–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.11.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Sun P., Boyer T.H. Degradation of pharmaceuticals and metabolite in synthetic human urine by UV, UV/H2O2, and UV/PDS. Environmental Science & Technology. 2015;49(5):3056–3066. doi: 10.1021/es504799n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Yang Y., Huang C.H. Kinetics and modeling of sulfonamide antibiotic degradation in wastewater and human urine by UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS. Water Res. 2016;103:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Yang Y., Huang C.H. UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS treatment of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole in synthetic human urine: transformation products and toxicity. Environmental Science & Technology. 2016;50(5):2573–2583. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b05604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Li Y., Wang Z. Biochar-activated peroxydisulfate as an effective process to eliminate pharmaceutical and metabolite in hydrolyzed urine. Water Res. 2020;177 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.Q., Li Y.J., Li Z.F. Investigation on microbial inactivation and urea decomposition in human urine during thermal storage. Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development. 2017;7(3):378–386. doi: 10.2166/washdev.2017.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Žilić S., Bozović I., Hadži-Tašković Šukalović V. Thermal inactivation of soybean bioactive proteins. Int. J. Food Eng. 2012;8(4) doi: 10.1515/1556-3758.2521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zrinyi N., Pham A.L. Oxidation of benzoic acid by heat-activated persulfate: effect of temperature on transformation pathway and product distribution. Water Res. 2017;120:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material