Abstract

Mental and substance use disorders are a leading cause of disability worldwide. Despite this, there is a paucity of mental health research in low- and middle-income countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. We carried out a semi-systematic scoping review to determine the extent of mental health research in Botswana. Using a predetermined search strategy, we searched the databases Web of Science, PubMed, and EBSCOhost (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL with Full Text, MEDLINE, MEDLINE with Full Text, MLA International Bibliography, Open Dissertations) for articles written in English from inception to June 2020. We identified 58 studies for inclusion. The most researched subject was mental health aspects of HIV/AIDS, followed by research on neurotic and stress-related disorders. Most studies were cross-sectional and the earliest published study was from 1983. The majority of the studies were carried out by researchers affiliated to the University of Botswana, followed by academic institutions in the USA. There seems to be limited mental health research in Botswana, and there is a need to increase research capacity.

Keywords: Mental illness, Botswana, psychiatric disorder, mental health research, mental health, semi- systematic review, scoping review

Introduction

Although mental health disorders are a leading cause of disability worldwide,1 mental health care is often given low priority, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).2,3 For example, it has been estimated that between 76% and 85% of people with severe mental disorders in LMICs receive no treatment.4 However, minimal resources are allocated to mental health globally, with a global median expenditure on mental health of less than 2% of government health expenditure.5 The figure is even lower in LMICs.6 This neglect of mental health care is compounded by, among other factors, the paucity of mental health research in LMICs. A 2008 World Health Organization mapping project on research capacity in LMICs found that over 50% of the 114 countries surveyed contributed fewer than five articles to the international mental health indexed literature between 1993 and 2003.7 A survey of original research published in six journals from 2002 to 2004 found that only 3.7% of the published articles came from LMICs and emphasized the need to strengthen the research capacity of LMICs.8 The survey also reported a positive association between the proportion of psychiatrists and research output. Similar findings were reported in a review of mental health research in Ghana, where most papers published between 1955 and 2009 were by psychiatrists.9

Mental health research is particularly sparse in Africa7 and is dominated by a few countries such as South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya.10 There is evidence that health research is an essential tool for improving health and health equity in LMICs.11 Although mental health research is important to generate evidence and inform policy, the evidence base in sub-Saharan Africa is limited; there is thus a need to increase research in Africa.12 One starting point is to explore the level of mental health research in Africa to establish what is available and identify research gaps.

Botswana is an upper middle-income country in Africa with a population of slightly over 2.4 million.13 Botswana’s health system is organized hierarchically, with national referral hospitals at the top and health posts at the bottom. The country’s mental health policy was developed in 2003 to provide a framework for the incorporation of the mental health programme into general healthcare services.14 Psychiatric patients are treated at all levels of the health system, but their first contact with mental health services is usually at the primary care level and mostly with psychiatric nurses. There is one national referral psychiatric hospital, Sbrana Psychiatric Hospital, which was officially opened in 2010. Most psychiatrists in Botswana are based at this hospital, which has a bed capacity of 300. At the time of writing, there were 11 psychiatrists in the country, of which five are academics, three are in private practice and the rest are in public service.

One objective of the Botswana national mental health policy is to promote mental health research. In addition, the University of Botswana, where the authors work, started a residency training programme in psychiatry in January 2020. Trainees are required to carry out research relevant to the needs of the country as part of their degree requirements. Botswana has no national mental health research database and to the best of our knowledge, the available literature on mental health research provides inadequate guidance to inform policy and practice. It is thus necessary to determine the extent of mental health research carried out in the country, and to identify priority research areas in mental health. Therefore, our aim was to explore the extent of mental health research in Botswana. We focused on identifying the main areas researched, research findings, the main research gaps and future research needs.

Methods

We conducted a semi-systematic, thematic scoping review. The study was semi-systematic in that we used the robust processes of a systematic review coupled with the rich, inductive, analytic nature of qualitative research to identify emerging themes and narratives.15–17 We adhered as much as possible to the relevant Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure methodological rigour in designing and reporting the study, while also adhering to the principles of qualitative research.16 Consistent with the scoping review method, we examined the literature broadly to determine what is known, gaps in knowledge, and what remains to be considered.16,18

Data searching and mining

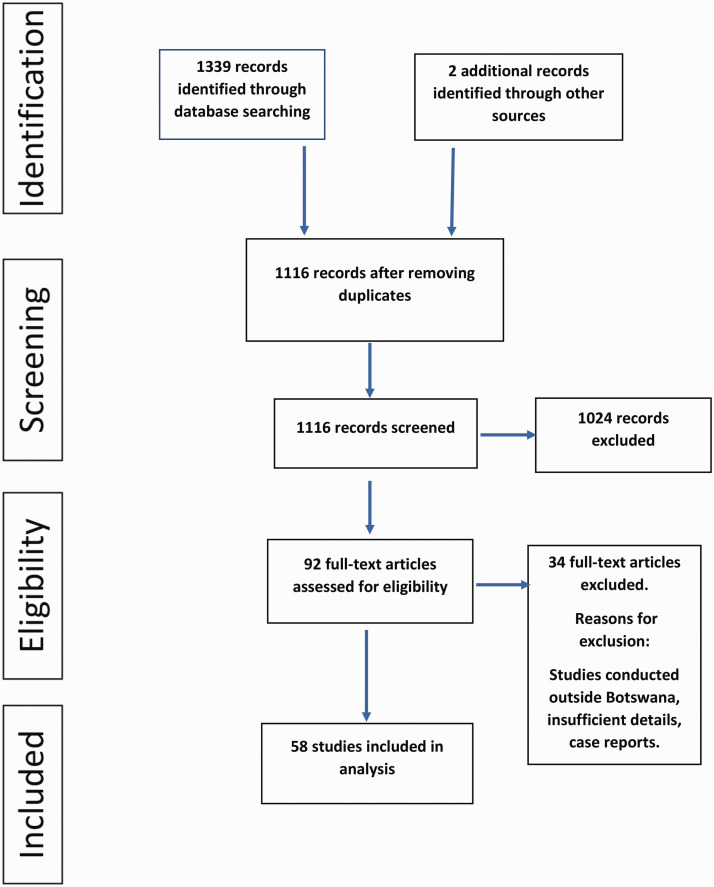

With the assistance of a medical librarian, we developed a search strategy using the key terms psychological phenomena and Botswana with their associated synonyms (Table 1). We used this predetermined search strategy to search Web of Science, PubMed and EBSCOhost (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL with Full Text, MEDLINE, MEDLINE with Full Text, MLA International Bibliography, Open Dissertations) for articles written in English from inception to June 2020. The search yielded 1339 articles (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Keywords | Synonyms |

|---|---|

| Psychological phenomena | psychological phenomena, psychology, psychological well-being, psychological distress, psychiatry, mental health, mental illness*, psychiatric illnesses, psychiatric disease*, social well-being, mental hygiene, emotional adjustment, psychiatric disorder*, mental disorder* |

| Botswana | Republic of Botswana, Bechuanaland, Bechuanaland Protectorate, Batswana, Tswana |

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Once the search was complete, we divided ourselves into three pairs, each of which was assigned a database for screening. Each pair screened titles and then abstracts to select the articles that met the inclusion criteria. We selected peer-reviewed articles published in English and carried out in Botswana from the earliest identified to June 2020. The process was iterative.19 Once each pair had completed screening, the whole team met to seek consensus on the selected articles. Those articles that did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria were excluded. This process yielded 92 full-text articles that were screened further; this yielded 58 studies that were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Data abstraction

To capture important details, we developed a review matrix20 using the following headings: author, date of publication, first author affiliation, location, title, method characteristics and key findings (Supplemental File). We used one article to pilot the matrix and ensure consistency when recording information using the matrix. We distributed full-text articles among the team, and each member read their allotted articles and filled in the matrix. The team met again to review the matrix to ensure consistent abstraction of data, completeness of data and exclusion of additional studies that did not meet the study criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all studies conducted on mental health topics in Botswana from the earliest identified to the end of June 2020. We only included studies published in English. We excluded studies in which no data had been collected, such as case reports, review articles and letters. Owing to limited financial and human resources, we were unable to contact the various potential repositories of grey literature.

Data analysis

We reviewed the matrix several times, sometimes going back to the full text to fully capture the data. We created subtables to sort and group some data elements, such as publication year. We also analysed the matrix using thematic analysis, which involves establishing familiarity with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing and naming themes.

Results

We identified 1339 records through the database search. After removing duplicates and screening for eligibility, 58 published studies were included in the analysis.

Characteristics of included studies

The earliest identified study was conducted in 198321. There were five publications from 1983 to 1987,21–25 followed by a 10-year period from 1989 to 1999 in which there were no studies. The number of studies has progressively increased from 2006, with 50 publications between 2006 and 2020.

Most (29) first authors were affiliated to the University of Botswana, but 20 first authors were affiliated to universities or institutions in the USA. Four first authors were affiliated to the Ministry of Health and Wellness, Botswana, three were from South African institutions, one from the UK and one from Japan.

Population

Most studies were conducted among students, followed by patients from different health institutions. Of the special populations studied, people living with HIV (PLWHIV) were the most frequently studied. Only one study was conducted among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and one among children living with disabilities.

Setting and study design

Studies in hospital settings dominated, followed by studies at the University of Botswana. Thirteen studies were conducted in community settings; only one study was conducted in a school for children with disabilities. Almost all the studies were cross-sectional and quantitative; more details about the included studies are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Areas of mental health addressed in the studies

Table 2 summarizes the main themes and subthemes identified, and the key findings. The most researched theme was HIV and mental health, followed by substance use.

Table 2.

Study themes and key findings.

| Theme | Subtheme | Key findings | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV and mental health | Depression | High prevalence of depression among people living with HIV (PLWHIV)Predictors of depression in PLWHIV are lower education, higher income, lack of control in sexual decision making and living in a rural area | 26–30 |

| Neurocognitive disorders | High prevalence of cognitive disorders | 30,31 | |

| Prevalence | HIV is more prevalent in mentally ill female inpatients | 32 | |

| Sexual behaviour | Batswana men had higher scores on a sexual addiction screening test than American men | 33 | |

| Psychosocial issues/distress | Issues among children include behavioural problems, family issues and HIV medication adherence | 34,35 | |

| Stigma | Mentally ill patients are stereotyped as dangerous and untrustworthy, and discriminated against | 36 | |

| Substance use | Prevalence and predictors | Alcohol is the most used substance in BotswanaAlcohol use is associated with depression and sleep abnormalitiesHaving drinking friends and alcohol availability are associated with drug useReligiosity protects against drug use Alcohol abuse is a risk factor for developing multidrug-resistant tuberculosisCannabis use disorder is associated with academic stress and an allowance of more than 150 USD per month. Religiosity is protectivePredictors of tobacco smoking include positive attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control and intention | 40–42,45,46,73 |

| Interventions | A behavioural activation/problem solving intervention for smoking cessation was found to be feasible and acceptable | 47 | |

| Sexual behaviour | Alcohol use and psychological distress contribute to risky sexual behaviour among adolescents | 33,43 | |

| Gender-based violence | Alcohol abuse increases the risk of gender-based violence | 44 | |

| Stress-related disorders | Trauma | PTSD symptoms were high in spouses of patients recently discharged from intensive care units | 37 |

| Stress | Availability of social relationships is associated with better physical and mental health and independence levelStudents are likely to use problem-solving strategies to cope with stressCortisol provides an adaptive boost to meet daily demands | 38,39,74 | |

| Depression | Depression | Stressful life events predict depression in university studentsA high rate of depression is associated with parental/childhood drug use, physical assault, failed urban migration and psychological aggressionLocus of control is associated with depression | 48–51,53 |

| Childhood trauma | Sexual abuse is the most experienced childhood trauma and predicts depression in adulthood | 52 | |

| Work-related factors | Stress | There is no association between performance appraisal and perceived stressOccupational stress is associated with psychosomatic complaints | 56,57 |

| Trauma | PTSD is high among mental health workersHigh neuroticism and exposure to violence in the past 12 months are associated with PTSD | 58 | |

| Physical violence | There is a high rate of patient violence toward mental health workersNurses experience more physical violence than other mental health staff | 54 | |

| Burnout | A high degree of burnout was found in registrars and this was related to insufficient salary and limited medical resources | 55 | |

| Tools | Validation | The psychometric properties of the GHQ-28 and PHQ-9 were good to excellent among the primary healthcare population in BotswanaThe Setswana version of the PSC had maximal sensitivity and specificity at a cutoff score of 20 | 62–64 |

| Tool development | A computerized brief cognitive screening battery was found to be feasible for use in Botswana | 75 | |

| Child and adolescent mental health | Pharmacological treatment | Psychotropic side effects and comorbidity are associated with polypharmacy | 59,76,77 |

| Abuse | Children with disabilities are exposed to high rates of abuse by their teachers | 60 | |

| Behavioural problems | Aggressive and antisocial behaviours are associated with poor parent–child relationships and low parental supervision | 61 | |

| Cognition | Urban children are more cognitively advanced than children from other environments | 22 | |

| Prevalence | ADHD is the most common disorder among younger children, and depression and psychosis are more common among older children and teenagers | 77 | |

| Gender-based violence | Mental health effects | Anxiety and depression are associated with gender-based violence | 66,78 |

| Sexual abuse | Sexual abuse is associated with a lower sense of belonging to the community, drug use problems and mental distress | 67 | |

| Intervention | Adapted play therapy was found to be useful in managing sexual abuse | 69 | |

| Intimate partner violence | Most intimate partner violence was physical, followed by emotionalSuicidal ideation was high among intimate partner violence victims | 68 | |

| Others | Training | Psychological research is very important in developing training programmes | 70 |

| Service provision | Deficits in service provision in Botswana are shortage of professionals and lack of a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment of disorders | 21,23,25 | |

| Caregiver mental health | Psychosocial effects experienced by grandmothers as primary caregivers include loneliness, financial hardship and depression | 65,71 | |

| Schizophrenia | According to the ICD-9, the prevalence of schizophrenia in Botswana is 4.9 per 1000 persons | 21,24 | |

| Family and mental health | Single parents and multiple family types predict mental health problems in young adults | 72 |

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; GHQ-28, General Health Questionnaire-28; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSC, Pediatric Symptom Checklist; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision.

HIV and mental health

The mental health aspects of HIV studied were depression26–29 neurocognitive disorders,30,31 the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in psychiatric patients,32 sexual behaviour33 and psychosocial issues.34,35

Most studies were conducted in general hospital settings; only one was conducted with psychiatric inpatients and found a high prevalence of HIV among female psychiatric inpatients.32 The prevalence of depression in PLWHIV ranges from 25.3% to 48%,26,27 and men (31.4%) are more affected than women (25.3%).27 Factors associated with depression in women were low energy and limitations in role function,28 lower education, higher income and lack of control in sexual decision making, whereas factors associated with depression in men were being single, living in a rural area and engaging in intergenerational sex.27 Psychosocial issues identified among adolescents with HIV in Botswana include behavioural problems (70%), family issues (58%) and HIV medication adherence (57%).34,35 A study on mental health stigma reported that patients with HIV and mental illness are stereotyped as dangerous and untrustworthy, and are discriminated against.36

Trauma and stress-related disorders

The findings of studies on trauma and stress varied. Dithole et al.37 investigated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among spouses of patients recently discharged from intensive care units and reported that more than half of participants experienced PTSD symptoms. Other studies on this topic showed that social relationships correlate positively with psychosocial wellbeing,38 and that problem-solving strategies are the preferred method of coping among students.39

Substance use

Alcohol is the most frequently used psychoactive substance in Botswana.40–42 Its use is associated with psychological distress,41 depression,40 risky sexual behaviours,43 gender-based violence44 and the development of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.45 Substances such as amphetamine and cannabis were found to be related to low participation in religious activities and difficulties in academic studies,41 and availability and peer pressure were found to predispose to substance use.42 Factors that contribute to tobacco smoking among students include attitudes and subjective norms.46 A study of HIV-infected smokers reported the feasibility of a behavioural intervention for tobacco cessation.47

Depression

Most studies were conducted among university students. Depression was associated with locus of control,48 suicidal ideation and previous suicide attempts.49,50 Childhood drug use and sexual abuse, parental substance use and physical assault, and psychological aggression to parents were found to predict depression in early adulthood.51,52 One study showed that failed urban migration and rural residence were associated with high depressive affect.53

Work-related mental health issues

Work-related mental health issues studied included physical violence by patients,54 burnout among registrars,55 perceived stress and performance appraisal discomfort among managers56 and occupational stress among university secretaries.57

One study reported healthcare workers’ lifetime experience of physical violence from patients, which was associated with greater job dissatisfaction.54 Nurses are more exposed to physical violence than any other type of healthcare provider,54 and just under 20% of staff who had experienced physical violence in the last 12 months met the criteria for PTSD.58 Additionally, those with a high level of neuroticism were about two times more likely to have PTSD than those with low neuroticism.58

Registrars (75%; n = 20) reported burnout in at least one of three domains: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment. The top five areas of frustration reported by registrars were insufficient salary, limited resources, long working hours, overnight calls and insufficient support from ancillary staff.55

Plattner and Mberengwa57 studied occupational stress among University of Botswana secretaries and found that exposure to stressors, such as lack of job clarity, supervising junior colleagues and sharing a computer, was associated with psychosomatic complaints. Gbadamosi and Ross56 explored the relationship between perceived stress and performance in managers and found no association between performance appraisal discomfort and perceived stress; women earned less income and their perceived stress was substantially higher than men’s.

Child and adolescent mental health

In a study of pharmacological treatment in children and adolescents in a mental hospital, Olashore and Rukewe59 found that the prevalence of polypharmacy was 29.2% and that psychiatric comorbidity and psychotropic side effects were strongly associated with polypharmacy. A study by Shumba and Abosi60 identified high rates of sexual, physical and emotional abuse by teachers toward disabled children. Boys rated themselves higher than girls on aggression in another study of secondary school students.61 A study of child cognition showed that urban children completed Piagetian tasks at an earlier age than children from other environments.22

Validation of tools

The Patient Health Questionnaire, the Pediatric Symptom Checklist and the General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) have been found to be reliable and valid for use in Botswana.62–64

Gender-based violence

Sociocultural practices, such as payment of lobola (a bride price), change of name and relocation of a woman to a man’s residence, were found to be major contributors of abuse in Botswana.65 Adverse sexual experiences have mental health consequences such as drug use.66,67 Intimate partner violence was reported to be associated with alcohol abuse and suicide,68 and with depression and anxiety.65 Dunn and Selemogwe69 explored sexual violence interventions using play therapy, and found that the Westernized concept of play therapy, with some adaptation, was relevant in Botswana.

Other topics covered

Other topics covered by the reviewed studies were training,70 service provision,21,23–25 caregiver burden,65,71 schizophrenia24 and effect of family type on mental health.72 Other findings73–78 are reported in Table 2.

Discussion

This study presents an overview of mental health research in Botswana, identifies gaps in research practice and helps provide a baseline for future research. Our search generated nine thematic areas with heterogeneous subthemes. The most widely researched topics were on mental health aspects of people living with HIV/AIDS. Most studies were cross-sectional and were carried out by researchers affiliated to the University of Botswana. The earliest identified study was in 1983 and there has been a subsequent and noticeable rise in the number of studies.

Our findings show a comparatively limited research output on mental health in Botswana; there were only 58 articles over a 27-year period. A systematic review of psychiatric research in South Africa, an upper middle-income country neighbouring Botswana, identified 908 articles over a 31-year period (1966 to 1997).79 Our finding that research in Botswana is limited is consistent with other studies that have identified a paucity of mental health research in LMICs.7,8,80 This limited research output may partly contribute to the neglect of mental health issues in LMICs.2 Patel and Kim8 posited that the proportion of psychiatrists in a country has a moderate influence on that country’s mental health research output. Botswana had very few psychiatrists until recently. There has been a modest increase in psychiatrists in Botswana following the establishment of a medical school in 2009, and this has contributed to a relative increase in mental health research. Of the 21 publications from 2016, almost half (48%)32,36,41,54,58,59,63,73,76,77 were by authors affiliated to the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Botswana. This relatively high output by academic researchers may be because university promotion criteria include research and publications. Thus, the establishment of a medical school whose curriculum includes psychiatry may be one way to improve mental health research output and capacity in LMICs.

Almost all the studies identified were cross-sectional and epidemiological. This relative lack of trial interventions for mental health in LMICs has been previously noted.81 The dominance of epidemiological studies in LMICs is not unique to Botswana,82 and may suggest either limited funding or lack of research capacity to carry out more methodologically complex studies. Furthermore, researchers in developing countries may chose a cross-sectional study design over more methodologically advanced designs because of other barriers, such as ethical and governing system procedures, competing demands, lack of a conducive research environment, and operational barriers.83 Although epidemiological data from cross-sectional studies can be used to inform the development of interventions, there is need for well-designed prospective studies that address a variety of research questions. Suggested solutions include strengthening collaboration and networks, and capacity building.82 There is an encouraging trend in efforts by various consortia to improve research capacity in African countries; for example, the Africa Focus on Intervention Research for Mental health (AFFIRM) project.84 However, one shortcoming of these efforts is that training is limited to academic institutions and that mental health professionals in public service, who constitute most mental healthcare providers, are left out.

Most studies were on mental health aspects of HIV/AIDS.26–34,36 Since 2003, there has been an overall increase in HIV-related mental health research in Africa.85 This research has been driven mostly by an increase in donor-funded programmes.85 Botswana has the third highest HIV prevalence in the world, with a national prevalence rate of 18.5% among the general population.86 Robust government- and donor-funded HIV programmes have been developed to combat HIV. Many of these programmes involve research into various correlates of HIV, and mental health research has benefited from this focus on HIV. One systematic review on HIV and mental health research in sub-Saharan Africa found a high prevalence of mental illness in PLWHIV.85 Therefore, it is not surprising that mental health aspects of HIV are among the most researched mental health topics in Botswana. Depression is the most frequently studied aspect of HIV and has attracted the attention of researchers, as it is the most prevalent mental health disorder in PLWHIV. Additionally, comorbidity of depression and HIV contributes to poor health outcomes such as substance use, poor medication adherence and stigma.87 The prevalence of depression among PLWHIV varied in the studies reviewed here, possibly because they were conducted in different settings and used different tools.

Depression was the subject of many studies, either as a single topic or in relation to other conditions. A survey of mental health research in LMICs by Razzouk et al.82 found that depression and anxiety disorders were among the most studied topics. Depression may be of interest to researchers because of its frequent association with other chronic conditions, and its contribution as a leading cause of disability globally.88 This may also explain why the two locally validated tools both screen for depression.63,64

Substance use was largely studied among university students, possibly because they are a high risk group.89,90 In line with findings of a global status report on drug use, alcohol is the most used substance in Botswana.91 It has been found to contribute to a high HIV infection rate,44 which supports findings by Fisher et al. in a 2007 systematic review of the association between HIV and alcohol use in Africa.92

Our review identifies several gaps in the research literature. Studies other than epidemiological surveys, such as randomized controlled trials, economic analyses and treatment outcome studies, are needed. Even the epidemiological studies have been mostly confined to a few mental health conditions; for example, almost all studies on mood disorder are on depression. There are no studies on bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders like schizophrenia, despite these conditions accounting for most admissions to the country’s only psychiatric hospital.32 Although suicide is among the top 20 leading causes of death in Botswana,6 there were surprisingly no studies on suicide.

Because most of the studies were on circumscribed populations such as hospital patients or students, it is difficult to generalize their findings to the general population. There is a need for more studies with samples representative of the national population.

The heterogeneity of the studies may be because there has been no national research priority-setting for mental health, so individual researchers or funders conduct research based on their own interests and priorities.93 There is thus a need to clearly set out a national mental health research priority agenda.

Study strengths and limitations

This review has several limitations that must be discussed. The search was limited to published research; we did not consider grey literature. Therefore, our findings may not accurately reflect the extent of mental health research in Botswana. We did not consider studies in languages other than English. This may not be a serious limitation, as the official language in higher education in Botswana is English, so it is unlikely that there are published studies in other languages. We also did not consider the methodological quality of included studies, as our aim was to provide an overview of existing research. However, a strength of the study is the use of several databases, which increases the likelihood that we located all the relevant published studies. Working in pairs, we critically assessed each study and synthesized individual study findings in an unbiased way.

Conclusion and recommendations

Our study identified a relative scarcity of mental health-related research in Botswana. The few studies identified were mostly cross-sectional and covered only a few aspects of mental health, such as HIV and mental health, and substance use. The findings suggest a need to strengthen the research capacity of individuals working in the mental health field. There is a need to develop a national database of research on mental health in Botswana and to set out research priorities. This would help to guide the mental health research agenda. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to review the extent of mental health research in Botswana. It thus forms a baseline for further reviews and priority-setting in mental health research in Botswana.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_0300060520966458 for Mental health research in Botswana: a semi-systematic scoping review by Philip R. Opondo, Anthony A. Olashore, Keneilwe Molebatsi, Caleb J. Othieno and James O. Ayugi in Journal of International Medical Research

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Masego Kebaetse, Khutsafalo Kadimo and Keamogetse Kegasitswe for their input and expertise in conducting the review.

Footnotes

Author contributions: PO conceived the idea. PO, KM and AO wrote the proposal and prepared the initial manuscript. JA and CO made intellectual contributions to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD: Anthony A. Olashore https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7608-0671

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, et al. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007; 370: 878–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ormel J, Petukhova M, Chatterji S, et al. Disability and treatment of specific mental and physical disorders across the world. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 192: 368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein D. Psychiatry and mental health research in South Africa: national priorities in a low and middle income context. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 2012; 15: 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Mental health atlas 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. WHO MiNDbank. http://www.who.int/mental_health/mindbank/en. 2018 (2018, accessed 26 September 2019).

- 7.Wei F. Research capacity for mental health in low-and middle-income countries: results of a mapping project. Bull World Health Organ 2008; 86: 908. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Kim YR. Contribution of low-and middle-income countries to research published in leading general psychiatry journals, 2002–2004. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190: 77–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Read UM, Doku V. Mental health research in Ghana: a literature review. Ghana Med J 2012; 46: 29–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uthman OA, Wiysonge CS, Ota MO, et al. Increasing the value of health research in the WHO African Region beyond 2015—reflecting on the past, celebrating the present and building the future: a bibliometric analysis. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e006340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dye C, Reeder JC, Terry RF. Research for universal health coverage. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5: 199ed13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaminer D, Owen M, Schwartz B. Systematic review of the evidence base for treatment of common mental disorders in South Africa. S Afr J Psychol 2018; 48: 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Botswana S. Population census atlas 2011: Botswana. Gaborone: Statistics Botswana, 2014. http://www.statsbots.org.bw/sites/default/files/publications/Census%20ATLAS.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidandi P, Opondo P, Tidimane S. Mental health in Botswana. Int Psychiatry 2011; 8: 66–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009; 26: 91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook DA. Narrowing the focus and broadening horizons: complementary roles for systematic and nonsystematic reviews. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2008; 13: 391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eva KW. On the limits of systematicity. Med Educ 2008; 42: 852–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonnalagadda S, Petitti D. A new iterative method to reduce workload in the systematic review process. Int J Comput Biol Drug Des 2013; 6: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrard J. Health Sciences literature review made easy. The matrix method. 2007. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Barlett Publishers, 2007, p.2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben-Tovim DI. A psychiatric service to the remote areas of Botswana. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 142: 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.John M, Dambe M, Polhemus S, et al. Children's thinking in Botswana: Piaget tasks examined. Int J Psychol 1983; 18: 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben-Tovim DI. DSM-III in Botswana: a field trial in a developing country. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142: 342–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Tovim DI, Cushnie JM. The prevalence of schizophrenia in a remote area of Botswana. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 148: 576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ben‐Tovim D, Boyce G. A comparison between patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals in Botswana and South Australia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 78: 222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis EL, Mosepele M, Seloilwe E, et al. Depression in HIV-positive women in Gaborone, Botswana. Health Care Women Int 2012; 33: 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta R, Dandu M, Packel L, et al. Depression and HIV in Botswana: a population-based study on gender-specific socioeconomic and behavioral correlates. PLoS One 2010; 5: e14252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman CL. Predictors of depression among seropositive Batswana men and women: a descriptive correlational study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2016; 30: 736–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vavani B, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P, et al. Intervention targets for people living with HIV and depressive symptoms in Botswana. Afr J AIDS Res 2020; 19: 80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawler K, Jeremiah K, Mosepele M, et al. Neurobehavioral effects in HIV-positive individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in Gaborone, Botswana. PLoS One 2011; 6: e17233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawler K, Mosepele M, Ratcliffe S, et al. Neurocognitive impairment among HIV-positive individuals in Botswana: a pilot study. J Int AIDS Soc 2010; 13: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Opondo PR, Ho-Foster AR, Ayugi J, et al. HIV prevalence among hospitalized patients at the main psychiatric referral hospital in Botswana. AIDS Behav 2018; 22: 1503–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delmonico MM, David L. Compulsive sexual behavior and HIV in Africa: a first look. Sex Addict Compulsivity 2001; 8: 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullan LE, Mullan PC, Anabwani GM. Psychosocial issues among children and adolescents in an integrated paediatric HIV psychology service in Botswana. J Psychol Afr 2015; 25: 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowenthal E, Lawler K, Harari N, et al. Rapid psychosocial function screening test identified treatment failure in HIV+ African youth. AIDS Care 2012; 24: 722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becker TD, Ho-Foster AR, Poku OB, et al. “It’s when the trees blossom”: explanatory beliefs, stigma, and mental illness in the context of HIV in Botswana. Qual Health Res 2019; 29: 1566–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dithole K, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G, Mgutshini T. Posttraumatic stress disorder among spouses of patients discharged from the intensive care unit after six months. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2013; 34: 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Modie-Moroka T. Stress, social relationships and health outcomes in low-income Francistown, Botswana. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014; 49: 1269–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monteiro NM, Balogun SK, Oratile KN. Managing stress: the influence of gender, age and emotion regulation on coping among university students in Botswana. Int J Adolesc Youth 2014; 19: 153–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balogun O, Koyanagi A, Stickley A, et al. Alcohol consumption and psychological distress in adolescents: a multi-country study. J Adolesc Health 2014; 54: 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olashore AA, Ogunwobi O, Totego E, et al. Psychoactive substance use among first-year students in a Botswana University: pattern and demographic correlates. BMC Psychiatry 2018; 18: 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riva K, Allen-Taylor L, Schupmann WD, et al. Prevalence and predictors of alcohol and drug use among secondary school students in Botswana: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018; 18: 1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Page RM, Hall CP. Psychosocial distress and alcohol use as factors in adolescent sexual behavior among sub‐Saharan African adolescents. J Sch Health 2009; 79: 369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phorano O, Nthomang K, Ntseane D. Alcohol abuse, gender-based violence and HIV/AIDS in Botswana: establishing the link based on empirical evidence. SAHARA J 2005; 2: 188–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zetola N, Modongo C, Kip E, et al. Alcohol use and abuse among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Botswana. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012; 16: 1529–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tapera R, Mbongwe B, Mhaka-Mutepfa M, et al. The theory of planned behavior as a behavior change model for tobacco control strategies among adolescents in Botswana. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0233462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsima BM, Moedi P, Maunge J, et al. Feasibility of implementing a novel behavioural smoking cessation intervention amongst human immunodeficiency virus-infected smokers in a resource-limited setting: a single-arm pilot trial. South Afr J HIV Med 2020; 21: 1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khumalo T, Plattner IE. The relationship between locus of control and depression: a cross-sectional survey with university students in Botswana. S Afr J Psychiatr 2019; 25: 1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hetolang LT, Amone-P’Olak K. The associations between stressful life events and depression among students in a university in Botswana. S Afr J Psychol 2018; 48: 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korb I, Plattner IE. Suicide ideation and depression in university students in Botswana. J Psychol Afr 2014; 24: 420–426. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mongale N, Amone-P’Olak K. Childhood family environment and depression in early adulthood in Botswana. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development 2019; 31: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillip O, Amone-P’Olak K. The influence of self-reported childhood sexual abuse on psychological and behavioural risks in young adults at a university in Botswana. S Afr J Psychol 2019; 49: 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Decker S. Failed urban migration and psychosomatic numbing: cortisol, unfulfilled lifestyle aspirations, and depression in Botswana. In Wood DC (ed) The economics of health and wellness: anthropological perspectives (Research in Economic Anthropology, Vol. 26). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2007, 26, pp.75–102.

- 54.Olashore AA, Akanni OO, Ogundipe RM. Physical violence against health staff by mentally ill patients at a psychiatric hospital in Botswana. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Westmoreland K, Lowenthal E, Finalle R, et al. Registrar wellness in Botswana: measuring burnout and identifying ways to improve wellness. Afr J Health Prof Educ 2017; 9: 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gbadamosi G, Ross C. Perceived stress and performance appraisal discomfort: the moderating effects of core self-evaluations and gender. Public Pers Manage 2012; 41: 637–659. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Plattner IE, Mberengwa DS. ‘We are the forgotten ones’: occupational stress among university secretaries in Botswana. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 2010; 8: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olashore AA, Akanni OO, Molebatsi K, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder among the staff of a mental health hospital: prevalence and risk factors. S Afr J Psychiatr 2018; 24: 1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olashore AA, Rukewe A. Polypharmacy among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders in a mental referral hospital in Botswana. BMC Psychiatry 2017; 17: 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shumba A, Abosi OC. The nature, extent and causes of abuse of children with disabilities in schools in Botswana. Intl J of Disabil Dev Educ 2011; 58: 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malete L. Aggressive and antisocial behaviours among secondary school students in Botswana: the influence of family and school based factors. Sch Psychol Int 2007; 28: 90–109. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lowenthal E, Lawler K, Harari N, et al. Validation of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist in HIV-infected Batswana. J Child Adolesc Ment Health 2011; 23: 17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molebatsi K, Motlhatlhedi K, Wambua GN. The validity and reliability of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for screening depression in primary health care patients in Botswana. BMC Psychiatry 2020; 20: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Segopolo MT, Selemogwe MM, Plattner IE, et al. A screening instrument for psychological distress in Botswana: validation of the Setswana version of the 28-item General Health Questionnaire. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2009; 55: 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thupayagale‐Tshweneagae G. Psychosocial effects experienced by grandmothers as primary caregivers in rural Botswana. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2008; 15: 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seloilwe ES, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G. Sexual abuse and violence among adolescent girls in Botswana: a mental health perspective. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2009; 30: 456–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sandfort T, Frazer MS, Matebeni Z, et al. Histories of forced sex and health outcomes among Southern African lesbian and bisexual women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Health 2015; 15: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barchi F, Winter S, Dougherty D, et al. Intimate partner violence against women in northwestern Botswana: the Maun women’s study. Violence Against Women 2018; 24: 1909–1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dunn M, Selemogwe M. Play therapy as an intervention against sexual violence in Botswana. J Psychol Afr 2009; 19: 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Plattner IE, Moagi-Gulubane S. Students’ views on the value of psychological research: a contribution to indigenising psychology in Botswana. J Psychol Afr 2009; 19: 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Philips PL, Lazenby M. The emotional and spiritual well-being of hospice patients in Botswana and sources of distress for their caregivers. J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 1438–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ramotuana BK, Amone-P’Olak K. Family type predicts mental health problems in young adults: a survey of students at a university in Botswana. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development 2020; 32: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olashore AA, Opondo PR, Ogunjumo JA, et al. Cannabis use disorder among first-year undergraduate students in Gaborone, Botswana. Subst Abuse 2020; 14: 1178221820904136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Decker SA, Aggott Z. Stress as adaptation? A test of the adaptive boost hypothesis among Batswana men. Evol Hum Behav 2013; 34: 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Plattner IE, Mbakile-Mahlanza L, Marobela S, et al. Developing a computerized brief cognitive screening battery for Botswana: A feasibility study. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2019; 34: 682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Olashore A, Ayugi J, Opondo P. Prescribing pattern of psychotropic medications in child psychiatric practice in a mental referral hospital in Botswana. Pan Afr Med J 2017; 26: 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Olashore AA, Frank-Hatitchki B, Ogunwobi O. Diagnostic profiles and predictors of treatment outcome among children and adolescents attending a national psychiatric hospital in Botswana. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2017; 11: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G, Seloilwe ES. Emotional violence among women in intimate relationships in Botswana. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2010; 31: 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fourie J, Flisher A, Emsley R, et al. Psychiatric research in South Africa: a systematic review of Medline publications. Curationis 2001; 24: 9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sankoh O, Sevalie S, Weston M. Mental health in Africa. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6: e954–e955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sheriff RJS, Adams CE, Tharyan P, et al. Randomised trials relevant to mental health conducted in low and middle-income countries: a survey. BMC Psychiatry 2008; 8: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Razzouk D, Sharan P, Gallo C, et al. Scarcity and inequity of mental health research resources in low-and-middle income countries: a global survey. Health Policy 2010; 94: 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alemayehu C, Mitchell G, Nikles J. Barriers for conducting clinical trials in developing countries-a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 2018; 17: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schneider M, Sorsdahl K, Mayston R, et al. Developing mental health research in sub-Saharan Africa: capacity building in the AFFIRM project. Glob Ment Health (Camb) 2016; 3: e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Breuer E, Myer L, Struthers H, et al. HIV/AIDS and mental health research in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Afr J AIDS Res 2011; 10: 101–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Republic of Botswana. Botswana Aids Impact Survey IV (BAIS IV). Statistical report 2013. Gaborone, Botswana: Statistics Botswana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tran BX, Ho R, Ho CS, et al. Depression among patients with HIV/AIDS: research development and effective interventions (GAPRESEARCH). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marcus M, Yasamy MT, Van Ommeren M, et al. Depression: a global public health concern. https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/who_paper_depression_wfmh_2012.pdf (2012, accessed 23 March 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Makanjuola AB, Daramola TO, Obembe AO. Psychoactive substance use among medical students in a Nigerian university. World Psychiatry 2007; 6: 112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Makanjuola A, Abiodun O, Sajo S. Alcohol and psychoactive substance use among medical students of the University of Ilorin, Nigeria. Eur Sci J 2014; 10: 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 91.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fisher JC, Bang H, Kapiga SH. The association between HIV infection and alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis of African studies. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34: 856–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sridhar D. Who sets the global health research agenda? The challenge of multi-bi financing. PLoS Med 2012; 9: e1001312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_0300060520966458 for Mental health research in Botswana: a semi-systematic scoping review by Philip R. Opondo, Anthony A. Olashore, Keneilwe Molebatsi, Caleb J. Othieno and James O. Ayugi in Journal of International Medical Research