Abstract

Objective

To estimate the use of hospitals for four essential primary care services offered in health centres in low- and middle-income countries and to explore differences in quality between hospitals and health centres.

Methods

We extracted data from all demographic and health surveys conducted since 2010 on the type of facilities used for obtaining contraceptives, routine antenatal care and care for minor childhood diarrhoea and cough or fever. Using mixed-effects logistic regression models we assessed associations between hospital use and individual and country-level covariates. We assessed competence of care based on the receipt of essential clinical actions during visits. We also analysed three indicators of user experience from countries with available service provision assessment survey data.

Findings

On average across 56 countries, public hospitals were used as the sole source of care by 16.9% of 126 012 women who obtained contraceptives, 23.1% of 418 236 women who received routine antenatal care, 19.9% of 47 677 children with diarrhoea and 18.5% of 82 082 children with fever or cough. Hospital use was more common in richer countries with higher expenditures on health per capita and among urban residents and wealthier, better-educated women. Antenatal care quality was higher in hospitals in 44 countries. In a subset of eight countries, people using hospitals tended to spend more, report more problems and be somewhat less satisfied with the care received.

Conclusion

As countries work towards achieving ambitious health goals, they will need to assess care quality and user preferences to deliver effective primary care services that people want to use.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer l'utilisation des hôpitaux pour quatre services de soins de santé primaires essentiels dans plusieurs centres de santé communautaires situés dans des pays à faible et moyen revenu, et examiner les différences de qualité entre hôpitaux et centres de santé communautaires.

Méthodes

Nous avons prélevé des données provenant de toutes les enquêtes démographiques et sanitaires menées depuis 2010 sur le type d'établissement fréquenté pour obtenir des moyens contraceptifs, des soins prénatals de routine ainsi qu'une prise en charge de la diarrhée d'importance mineure, la toux ou la fièvre chez l'enfant. Nous avons employé des modèles de régression logistique à effets mixtes pour examiner les associations entre le recours aux hôpitaux d'une part, et les covariables individuelles et nationales d'autre part. Nous avons mesuré le niveau de compétence des soins en nous fondant sur la réalisation d'actes cliniques essentiels lors des visites. Nous avons également analysé trois indicateurs d'expérience en tant que patient dans les pays où nous avons pu accéder aux résultats d'enquêtes d'évaluation des prestations de service.

Résultats

Selon la moyenne établie sur 56 pays, les hôpitaux publics constituaient l'unique source de soins pour 16,9% des 126 012 femmes qui se sont procuré des contraceptifs, 23,1% des 418 236 femmes qui ont reçu des soins prénatals de routine, 19,9% des 47 677 enfants atteints de diarrhée et 18,5% des 82 082 enfants souffrant de fièvre ou de toux. Le recours aux hôpitaux était plus fréquent dans les pays plus riches où les dépenses en soins de santé par habitant étaient plus élevées, mais aussi parmi les citadines et les femmes plus aisées et mieux instruites. La qualité des soins prénatals était meilleure dans les hôpitaux de 44 pays. Dans un sous-groupe de huit pays, les gens qui se rendaient dans les hôpitaux avaient tendance à dépenser davantage, à signaler plus de problèmes et à se montrer moins satisfaits vis-à-vis des soins prodigués.

Conclusion

À mesure que les pays s'efforceront d'atteindre des objectifs sanitaires ambitieux, ils devront évaluer la qualité des soins et les préférences des patients afin de proposer des services de soins de santé primaires efficaces auxquels les gens voudront faire appel.

Resumen

Objetivo

Estimar el uso de los hospitales para cuatro servicios esenciales de atención primaria que se ofrecen en los centros de salud de los países de ingresos bajos y medios, así como estudiar las diferencias de calidad entre los hospitales y los centros de salud.

Métodos

Se obtuvieron los datos de todas las encuestas demográficas y de salud realizadas desde 2010 sobre el tipo de instalaciones que se usan para obtener anticonceptivos, atención prenatal de rutina y atención de la diarrea infantil leve y la tos o la fiebre. Se evaluaron las asociaciones entre el uso de los hospitales y las covariables a nivel individual y nacional mediante la aplicación de modelos de regresión logística de efectos mixtos. También se evaluó la competencia de la atención basada en la recepción de medidas clínicas esenciales durante las consultas. Asimismo, se analizaron tres indicadores de la experiencia de los usuarios de los países que disponían de datos de encuestas de evaluación de la prestación de servicios.

Resultados

En un promedio de 56 países, los hospitales públicos fueron usados como la única fuente de atención por el 16,9 % de 126 012 mujeres que adquirieron anticonceptivos, el 23,1 % de 418 236 mujeres que recibieron atención prenatal de rutina, el 19,9 % de 47 677 niños con diarrea y el 18,5 % de 82 082 niños con fiebre o tos. El uso de los hospitales fue más común en los países más ricos con mayores gastos en salud per cápita y entre los residentes de las zonas urbanas y las mujeres más acaudaladas y mejor educadas. La calidad de la atención prenatal fue superior en los hospitales de 44 países. En un subconjunto de ocho países, las personas que acudieron a los hospitales tendían a gastar más, a reportar más quejas y a estar algo menos satisfechas con la atención recibida.

Conclusión

A medida que los países se esfuerzan por alcanzar objetivos sanitarios ambiciosos, tendrán que evaluar la calidad de la atención y las preferencias de los usuarios para prestar los servicios de atención primaria efectivos que las personas pretenden usar.

ملخص

الغرض تقدير الاعتماد على المستشفيات في خدمات الرعاية الأولية الأساسية التي تقدمها المراكز الصحية البلدان ذات الدخل المنخفض والمتوسط، واستكشاف الفروق في الجودة بين المستشفيات والمراكز الصحية.

الطريقة استخرجنا البيانات من جميع المسوح السكانية والصحية التي أجريت منذ عام 2010 حول نوع المرافق المستخدمة للحصول على وسائل منع الحمل، والرعاية الروتينية السابقة للولادة، ورعاية حالات الإسهال والسعال أو الحمى الطفيفة لدى الأطفال. وباستخدام نماذج التحوف اللوجيستي ذات التأثيرات المختلطة، قمنا بتقييم الارتباطات بين الاعتماد على المستشفى، والمتغيرات المشتركة على المستوى الفردي ومستوى البلد. قمنا بتقييم كفاءة الرعاية بناءً على فرص الحصول على الإجراءات السريرية الأساسية أثناء الزيارات. قمنا أيضًا بتحليل ثلاثة مؤشرات لتجربة المستخدم من البلدان التي يتوفر فيها بيانات مسح تقييم تقديم الخدمة.

النتائج في المتوسط عبر 56 بلدًا، تم الاعتماد على المستشفيات العامة كمصدر وحيد للرعاية بواسطة 16.9% من 126012 امرأة حصلن على وسائل منع الحمل، و23.1% من 418236 امرأة حصلن على الرعاية الروتينية السابقة للولادة، و19.9% من 47677 طفلاً يعانون من الإسهال، و18.5% من 82082 طفلاً يعانون من الحمى أو السعال. كان الاعتماد على المستشفى أكثر شيوعًا في البلدان الأغنى مع ارتفاع نفقات الصحة للفرد، وبين سكان الحضر، والنساء الأكثر ثراءً والأفضل تعليمًا. كانت جودة الرعاية السابقة للولادة أعلى في المستشفيات في 44 بلدًا. في مجموعة فرعية من ثمانية بلدان، كان الأشخاص الذين يعتمدون على المستشفيات يميلون إلى إنفاق أكثر، والإبلاغ عن المزيد من المشكلات، ويكونون أقل رضا إلى حد ما عن الرعاية التي حصلوا عليها.

الاستنتاج بينما تعمل البلدان تجاه تحقيق أهداف صحية طموحة، فإنها سوف تحتاج إلى تقييم جودة الرعاية وتفضيلات المستخدم لتقديم خدمات رعاية أولية فعالة، يرغب الناس في الاعتماد عليها.

摘要

目标

评估在中低收入国家使用医院来获取卫生中心提供的四类基本的初级护理服务的情况,并探讨医院和卫生中心之间的质量差异。

方法

我们从 2020 年以来开展的所有人口统计和健康调查中提取出相关数据,这些调查涉及用于避孕、常规产前护理以及儿童轻微腹泻咳嗽或发烧护理的设施类型。利用混合效应逻辑回归模型,我们评估了医院使用与个人和国家层面协变量之间的相关性。我们根据就诊期间基本临床行动的接收情况来评估其护理能力。我们还分析了拥有现成的服务提供评估调查数据的国家的三个用户体验指标。

结果

56 个国家平均而言,126012 名获取过避孕药具的女性中,仅选择公立医院的女性占 16.9%;418236 名接受常规产前护理的女性中,占比达 23.1%;47677 名腹泻儿童中,占比达 19.9%;82082 名发烧或咳嗽儿童中,占比达 18.5%。在人均卫生支出较高的富裕国家、城市居民以及较富裕受过良好教育的女性中,选择医院更为普遍。44 个国家的医院产前护理质量较高。其中八个国家,选择医院的人士往往花费更多,报告的问题更多,对所得到的护理也不太满意。

结论

随着多国努力实现宏伟的卫生目标,它们将需要评估护理质量和用户偏好,以提供人们希望使用的有效的初级护理服务。

Резюме

Цель

Оценка использования больниц для оказания четырех основных услуг первичной медико-санитарной помощи, предлагаемых в медицинских центрах в странах с низким и средним уровнем доходов, а также изучение различий в качестве услуг между больницами и медицинскими центрами.

Методы

Авторы извлекли данные из всех демографических и медицинских опросов, проведенных с 2010 года, о типах учреждений, используемых для получения противозачаточных средств, плановой дородовой помощи и лечения незначительных случаев детской диареи, кашля или лихорадки. Используя модели логистической регрессии со смешанными эффектами, авторы оценили связи между использованием больниц и ковариатами на индивидуальном и национальном уровнях. Авторы оценили компетентность оказания помощи на основе получения необходимых клинических действий во время обращений. Были также проанализированы три показателя опыта пользователей из стран, по которым имеются данные опроса по оценке оказания услуг.

Результаты

В среднем в 56 странах государственные больницы использовались в качестве единственного источника медицинской помощи: 16,9% из 126 012 женщин, получавших противозачаточные средства, 23,1% из 418 236 женщин, получавших плановую дородовую помощь, 19,9% из 47 677 детей с диареей и 18,5% из 82 082 детей с лихорадкой или кашлем. Использование больниц было более распространенным явлением в более богатых странах с более высоким уровнем медицинских расходов на душу населения, а также среди городских жителей и более богатых, более образованных женщин. Качество дородовой помощи было выше в больницах в 44 странах. В подгруппе из восьми стран люди, обращающиеся в больницы, как правило, тратили больше, сообщали о большем количестве проблем и были несколько менее удовлетворены полученной помощью.

Вывод

По мере работы стран над достижением амбициозных целей в области здравоохранения им необходимо будет оценивать качество медицинской помощи и предпочтения пользователей, чтобы предоставлять эффективные услуги первичной медико-санитарной помощи, которыми люди хотят пользоваться.

Introduction

Achieving universal health coverage (UHC) will require affordable, high-quality primary care that is accessible to all people, at every age.1 Primary care is recognized as an essential platform for addressing the growing burden of chronic diseases and for detecting and managing infectious disease outbreaks in places that are most vulnerable to them.2–5 The 2008 World Health Report on primary health care emphasized that provision of high-quality primary care requires relocating the entry point to the health system from hospital outpatient departments to primary care centres.6 The more recent World Health Organization (WHO) global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services also calls for rebalancing health services towards primary care, and reducing the emphasis on the hospital sector.7 Primary care requires a relationship of trust between people and their providers.6 Settings such as busy hospital outpatient departments are not organized to build such relationships and produce people-centred care.6 In contrast, government health centres have usually been designed to work in close relationship with the community they serve, and can create the conditions for more comprehensive, person-centred continuing care.

Nonetheless, reports of people opting to use hospitals instead of health centres are common in low- and middle-income countries.8–10 Several factors may lead people to choose hospitals: negative perceptions about health centres (perceived poor quality or lack of trust), the convenience of hospitals, and the health policies in place.11–13 However, seeking care in hospitals may lead to excessive health-care spending and reduced equity and patient-centeredness and be a missed opportunity to promote relationships with primary care providers over time.8

Monitoring the proportion of people who use hospitals for essential health services and understanding the factors driving hospital use is important for strengthening primary care systems. In this analysis, we estimated the proportion of people who visited hospitals for four essential health services offered at health centres in low- and middle-income countries and explored the factors associated with hospital use. We also described differences in the quality of these services between hospitals and health centres.

Methods

Data sources

We used data from all demographic and health surveys conducted in low- and middle-income countries since 2010 and included the most recent survey available in each country (as of 20 January 2020). The demographic and health surveys are nationally representative household surveys that collect data on population health indicators with a strong focus on maternal and child health. Sampling strategies and methods have been described previously.14 We obtained data on country characteristics and purchasing power exchange rates from the World Bank’s world development indicators database15 and worldwide governance indicators project.16

We also included data from service provision assessment surveys. These surveys use nationally representative samples or censuses or near censuses of the country’s health facilities to provide a comprehensive overview of health service delivery in a country.17 We included the most recent surveys conducted in the same timeframe as the corresponding demographic and health survey (2010–2018) that included exit interviews with people attending family planning, antenatal care and sick-child care services.

Essential health services

We described the type of health facility used for four non-urgent health services typically provided in primary care settings: (i) contraceptives, (ii) routine antenatal care, (iii) care for children younger than 5 years with non-severe diarrhoea; and (iv) care for children younger than 5 years with fever or a cough. These essential health services should be addressed in primary care settings and are four of the 16 tracer indicators selected to monitor progress towards UHC.18 In the demographic and health survey, women were asked to report the type of facility visited for each of the services. Those who used the public sector reported the level of the facility: whether it was a hospital or a lower-level facility dedicated to primary care such as a health centre or a clinic. For those who used the private sector, the demographic and health survey did not differentiate between hospitals and lower-level facilities. We therefore created three categories of facilities visited: (i) public hospitals (including district, regional, national and military hospitals); (ii) public health centres (including all non-hospital facilities); and (iii) any private health-care facilities. We excluded care received from homes, pharmacies, shops, drug sellers, traditional practitioners or a friend or relative.

To identify the usual or sole source of care and to exclude those people who may have been referred from a primary care facility to the hospital, we excluded anyone who reported using multiple types of facility for the same service. To restrict the sample to those with non-urgent and less severe conditions, we excluded women who were pregnant with twins or had previously had a perinatal death, as these women may be at greater risk of complicated pregnancies and may require more advanced antenatal care.19 For childhood diarrhoea, we excluded children who had blood in their stools. Among children with a fever or cough, we excluded those with suspected pneumonia as defined by the survey (a cough accompanied by short rapid breaths and difficulty breathing that is related to a problem in the chest). For contraceptives, we excluded women who used intrauterine devices, sterilization or implants as these more advanced methods may only be provided in hospitals.

To explore why people might visit public hospitals for services that are offered in primary care settings, we included a series of individual-level covariates available from the survey. These included urban residence, age group (15–19, 20–30, 31–40 or 41–65 years), secondary education, wealth quintiles and exposure to the media. We also explored associations with a series of country-level factors hypothesized to influence hospital use. These included year of the demographic and health survey (pre- or post-2015), the world region, country’s surface area, country’s total expenditure on health per capita, share of total health expenditure paid by patients out-of-pocket and an indicator of government effectiveness.15,16 We used country covariates for the year before the demographic and health survey. In cases where that year’s estimate was unavailable, we used the estimate for the closest year.

Quality of care

To evaluate quality of care, we explored differences in provision of competent care and the user experience12 between public hospitals and health centres for the services included in this study.

We assessed competence of care in the demographic and health survey based on the receipt of essential clinical actions during visits. For antenatal care, we measured receipt of three items during consultations: blood pressure monitoring and urine and blood testing. For child diarrhoea, we assessed whether oral rehydration solutions were provided. For contraceptives, we measured whether women reported being counselled about potential side-effects when first prescribed the method, and being told about alternative contraception methods by the health provider. We were unable to identify any quality of care indicator for childhood fever or cough in the survey. These indicators offer only a limited view of the quality of these services. However, they are recommended as essential components of care according to WHO guidance20–22 and have been used by others to describe quality.12,23

We also analysed three indicators of user experience from a subset of eight countries with available data from service provision assessment surveys: cost of visit, number of problems experienced, and satisfaction. These indicators were measured during client exit interviews among those who sought family planning, antenatal care and sick child care services in public hospitals and in health centres.

Statistical analysis

First, we summarized the proportion of women seeking each of the four services in public hospitals, public health centres and in private facilities by country using individual-level sampling weights. We pooled the estimates across countries by weighting each country equally.

Second, to explore associations between individual and country-level factors and public hospital use for these services we used generalized linear mixed-effects models based on a logit-link function with a random intercept for the country. We repeated the models for each of the four health services. Because private sector users may differ from those seeking care in the public sector, the regression analyses were limited to those people who used public facilities.

Finally, we compared quality of care in public hospitals and health centres using data from the demographic and health surveys and the service provision assessment surveys by estimating means for each indicator using individual-level (or client-level) sampling weights and weighting countries equally.

We performed descriptive analyses using Stata version 16 (Stata Corp., College Station, United States of America) and fitted the mixed-effects models using R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 58 countries conducted a demographic and health survey since 2010. However, Colombia and Turkey did not include data on care-seeking for sick children and were excluded. We, therefore, included 56 countries with surveys conducted from 2010 to 2018, the majority (31, 55.4%) conducted from 2015 to 2018.

Essential health services

Data were available for 126 012 women who obtained contraceptives, 418 236 women who received antenatal care, 47 677 children younger than 5 years with diarrhoea and 82 082 children younger than 5 years with fever or cough. On average across the 56 countries, the proportions of women who sought care in public hospitals were 16.9% for contraceptives, 23.1% for antenatal care, 19.9% for childhood diarrhoea and 18.5% for childhood fever or cough (pooled averages weigh countries equally; country-specific averages use individual-level sampling weights; Table 1; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/98/11/19-245563). Public health centres were used for these services by 64.7%, 58.9%, 56.4% and 55.3% of women, respectively. The remaining women relied on the private sector.

Table 1. Type of facility used for services offered in primary care settings in 56 low- and middle-income countries.

| Country (year of survey) | Income groupa | No. (%) of respondents using service |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contraceptives |

Antenatal care |

Childhood diarrhoea |

Childhood fever or cough |

|||||||||||||||||

| Total | Public hospitals | Public health centres | Private sector | Total | Public hospitals | Public health centres | Private sector | Total | Public hospitals | Public health centres | Private sector | Total | Public hospitals | Public health centres | Private sector | |||||

| Afghanistan (2015) | Low | 2 451 | 28.5 | 47.8 | 23.7 | 9 619 | 37.6 | 30.4 | 32.1 | 3 516 | 29.1 | 38.1 | 32.7 | 2 599 | 28.7 | 38.0 | 33.3 | |||

| Albania (2017–2018) | Upper middle | 40 | 13.6 | 80.0 | 6.4 | 1 704 | 58.6 | 24.3 | 17.1 | 94 | 39.3 | 52.7 | 7.9 | 122 | 30.6 | 66.2 | 3.2 | |||

| Angola (2015) | Upper middle | 746 | 35.2 | 57.4 | 7.4 | 6 576 | 31.4 | 60.6 | 8.1 | 863 | 31.3 | 56.8 | 11.9 | 872 | 30.9 | 59.8 | 9.4 | |||

| Armenia (2016) | Lower middle | 29 | 26.3 | 50.2 | 23.5 | 1 292 | 27.5 | 65.3 | 7.2 | 26 | 33.6 | 61.8 | 4.7 | 92 | 18.1 | 79.1 | 2.8 | |||

| Bangladesh (2014) | Low | 7 622 | 1.5 | 42.6 | 56.0 | 2 780 | 10.4 | 26.9 | 62.8 | 105 | 7.3 | 26.9 | 65.8 | 854 | 9.3 | 22.3 | 68.4 | |||

| Benin (2017–2018) | Low | 420 | 16.4 | 64.7 | 18.9 | 7 536 | 19.9 | 79.1 | 0.9 | 307 | 10.1 | 73.5 | 16.3 | 1 027 | 8.0 | 41.4 | 50.6 | |||

| Burkina Faso (2010) | Low | 1 326 | 14.3 | 81.5 | 4.2 | 9 406 | 6.4 | 92.3 | 1.4 | 838 | 17.4 | 79.6 | 3.1 | 1 609 | 16.7 | 79.6 | 3.6 | |||

| Burundi (2017) | Low | 1 494 | 9.1 | 85.9 | 5.0 | 7 929 | 8.5 | 77.1 | 14.4 | 1 504 | 5.4 | 81.8 | 12.8 | 2 903 | 4.8 | 81.3 | 13.9 | |||

| Cambodia (2014) | Low | 2 348 | 1.0 | 62.8 | 36.2 | 5 032 | 7.8 | 86.7 | 5.5 | 401 | 3.5 | 31.4 | 65.1 | 1 017 | 6.9 | 27.7 | 65.4 | |||

| Cameroon (2011) | Lower middle | 530 | 43.0 | 31.8 | 25.2 | 6 000 | 27.4 | 42.6 | 30.0 | 387 | 25.8 | 50.3 | 23.9 | 955 | 24.7 | 44.9 | 30.4 | |||

| Chad (2014–2015) | Low | 362 | 33.2 | 48.2 | 18.6 | 6 334 | 20.0 | 77.1 | 2.9 | 743 | 13.0 | 55.4 | 31.6 | 726 | 13.3 | 54.2 | 32.4 | |||

| Comoros (2012) | Low | 362 | 22.5 | 75.1 | 2.5 | 1 632 | 29.9 | 61.5 | 8.6 | 158 | 21.5 | 72.9 | 5.7 | 322 | 27.9 | 62.3 | 9.8 | |||

| Congo (2012) | Lower middle | 502 | 55.0 | 27.5 | 17.5 | 5 139 | 46.5 | 41.2 | 12.4 | 436 | 59.0 | 23.6 | 17.4 | 890 | 49.4 | 37.0 | 13.7 | |||

| Côte d’Ivoire (2011–2012) | Lower middle | 365 | 29.6 | 59.6 | 10.8 | 4 369 | 29.4 | 63.2 | 7.3 | 249 | 27.4 | 60.8 | 11.8 | 536 | 25.1 | 60.9 | 14.0 | |||

| Democratic Republic of the Congo (2014) | Low | 1 051 | 11.6 | 13.1 | 75.4 | 9 219 | 17.6 | 64.9 | 17.5 | 836 | 8.3 | 65.7 | 26.0 | 1 988 | 6.1 | 63.5 | 30.4 | |||

| Dominican Republic (2013) | Upper middle | 834 | 48.2 | 34.5 | 17.3 | 659 | 89.2 | 1.4 | 9.5 | 143 | 69.2 | 22.7 | 8.2 | 187 | 79.8 | 16.0 | 4.2 | |||

| Egypt (2014) | Lower middle | 2 690 | 7.3 | 88.7 | 4.0 | 12 701 | 2.1 | 9.8 | 88.2 | 1 090 | 9.5 | 14.3 | 76.2 | 1 940 | 8.9 | 13.4 | 77.7 | |||

| Ethiopia (2016) | Low | 2 583 | 2.3 | 81.1 | 16.5 | 4 326 | 6.1 | 88.2 | 5.8 | 534 | 4.8 | 71.3 | 23.9 | 371 | 5.2 | 63.9 | 30.9 | |||

| Gabon (2012) | Upper middle | 318 | 50.7 | 31.3 | 18.0 | 3 214 | 41.8 | 35.5 | 22.7 | 263 | 54.8 | 34.1 | 11.2 | 726 | 48.4 | 37.8 | 13.8 | |||

| Gambia (2013) | Low | 394 | 12.8 | 65.3 | 21.9 | 4 906 | 16.9 | 75.0 | 8.0 | 780 | 16.5 | 76.9 | 6.6 | 541 | 14.4 | 75.7 | 9.9 | |||

| Ghana (2014) | Lower middle | 628 | 29.7 | 61.4 | 8.9 | 3 675 | 48.4 | 40.5 | 11.1 | 233 | 29.3 | 54.8 | 15.9 | 466 | 32.7 | 50.0 | 17.4 | |||

| Guatemala (2014–2015) | Lower middle | 2 570 | 4.4 | 82.1 | 13.6 | 7 363 | 8.3 | 64.9 | 26.8 | 960 | 6.6 | 49.9 | 43.5 | 1 461 | 6.0 | 55.7 | 38.3 | |||

| Guinea (2018) | Low | 364 | 12.7 | 74.6 | 12.7 | 4 259 | 11.6 | 82.6 | 5.9 | 417 | 6.8 | 79.8 | 13.3 | 553 | 11.7 | 77.7 | 10.7 | |||

| Haiti (2017) | Low | 2 032 | 20.7 | 45.7 | 33.6 | 4 002 | 36.9 | 57.6 | 5.6 | 408 | 20.1 | 56.8 | 23.1 | 793 | 16.1 | 61.4 | 22.5 | |||

| Honduras (2012) | Lower middle | 3 001 | 4.4 | 79.0 | 16.6 | 7 399 | 14.3 | 68.8 | 17.0 | 824 | 16.5 | 63.2 | 20.2 | 1 523 | 12.5 | 64.4 | 23.1 | |||

| India (2016) | Lower middle | 19 799 | 13.5 | 24.7 | 61.8 | 108 798 | 33.2 | 27.8 | 39.0 | 12 908 | 14.4 | 8.3 | 77.4 | 23 211 | 16.1 | 9.1 | 74.8 | |||

| Indonesia (2017) | Lower middle | 11 926 | 0.2 | 34.1 | 65.7 | 10 525 | 2.6 | 33.1 | 64.3 | 1 238 | 2.4 | 42.2 | 55.4 | 3 128 | 1.7 | 38.1 | 60.2 | |||

| Jordan (2017–2018) | Lower middle | 1 129 | 4.7 | 73.5 | 21.9 | 5 937 | 19.0 | 12.3 | 68.7 | 404 | 21.3 | 29.5 | 49.2 | 468 | 13.8 | 39.3 | 46.9 | |||

| Kenya (2014) | Low | 6 652 | 18.1 | 50.3 | 31.6 | 6 206 | 31.8 | 52.0 | 16.3 | 1 362 | 17.7 | 63.4 | 18.9 | 3 355 | 17.7 | 60.3 | 22.1 | |||

| Kyrgyzstan (2012) | Low | 139 | 8.4 | 73.7 | 17.9 | 2 581 | 13.5 | 84.6 | 1.9 | 98 | 24.2 | 72.5 | 3.3 | 107 | 26.3 | 70.8 | 3.0 | |||

| Lesotho (2014) | Lower middle | 2 233 | 16.8 | 57.5 | 25.7 | 2 211 | 19.1 | 56.0 | 24.9 | 144 | 17.9 | 55.4 | 26.7 | 383 | 16.0 | 50.5 | 33.5 | |||

| Liberia (2013) | Low | 1 354 | 33.7 | 41.7 | 24.6 | 4 139 | 38.6 | 42.5 | 18.8 | 469 | 18.1 | 54.9 | 27.0 | 977 | 19.5 | 51.5 | 29.0 | |||

| Malawi (2016) | Low | 6 348 | 12.6 | 73.6 | 13.9 | 12 506 | 19.2 | 67.5 | 13.3 | 2 137 | 13.3 | 76.1 | 10.7 | 2 666 | 12.1 | 74.5 | 13.4 | |||

| Maldives (2016–2017) | Upper middle | 215 | 29.0 | 56.8 | 14.1 | 1 693 | 58.4 | 7.0 | 34.6 | 95 | 39.8 | 44.9 | 15.4 | 522 | 24.9 | 44.7 | 30.4 | |||

| Mali (2018) | Low | 592 | 2.0 | 78.0 | 20.0 | 4 863 | 2.3 | 91.5 | 6.2 | 407 | 1.8 | 80.8 | 17.4 | 427 | 0.7 | 81.5 | 17.8 | |||

| Mozambique (2011) | Low | 1 121 | 17.4 | 79.2 | 3.4 | 6 564 | 20.0 | 79.2 | 0.8 | 596 | 93.4 | 0.7 | 5.8 | 987 | 93.4 | 1.0 | 5.6 | |||

| Myanmar (2015–2016) | Lower middle | 2 204 | 10.7 | 68.3 | 21.1 | 2 304 | 28.3 | 59.0 | 12.7 | 207 | 24.4 | 47.1 | 28.5 | 437 | 18.8 | 47.9 | 33.4 | |||

| Namibia (2013) | Upper middle | 3 429 | 23.2 | 67.9 | 8.9 | 3 431 | 33.1 | 58.4 | 8.5 | 410 | 27.5 | 66.7 | 5.8 | 682 | 24.3 | 62.1 | 13.6 | |||

| Nepal (2016) | Low | 1 364 | 6.0 | 72.4 | 21.6 | 2 775 | 28.6 | 51.7 | 19.7 | 131 | 11.2 | 32.6 | 56.2 | 477 | 12.4 | 26.2 | 61.4 | |||

| Nigeria (2018) | Lower middle | 1 112 | 30.6 | 55.9 | 13.6 | 14 824 | 31.5 | 50.0 | 18.5 | 1 050 | 23.5 | 66.3 | 10.2 | 2 135 | 22.2 | 65.4 | 12.4 | |||

| Pakistan (2017–2018) | Lower middle | 580 | 19.0 | 61.3 | 19.7 | 5 160 | 23.8 | 2.6 | 73.7 | 1 143 | 14.0 | 2.9 | 83.1 | 1 870 | 12.8 | 3.6 | 83.6 | |||

| Papua New Guinea (2016–2018) | Lower middle | 1 228 | 19.5 | 74.6 | 6.0 | 4 902 | 24.9 | 70.2 | 4.9 | 476 | 18.8 | 75.0 | 6.2 | 695 | 16.2 | 78.8 | 5.0 | |||

| Peru (2012) | Upper middle | 3 665 | 12.2 | 85.2 | 2.7 | 5 924 | 20.3 | 71.0 | 8.8 | 299 | 20.9 | 62.7 | 16.4 | 1 392 | 16.7 | 58.8 | 24.5 | |||

| Philippines (2017) | Lower middle | 1 957 | 1.4 | 94.7 | 4.0 | 6 685 | 10.5 | 64.5 | 25.0 | 254 | 11.7 | 52.8 | 35.5 | 733 | 10.9 | 55.2 | 33.9 | |||

| Rwanda (2014–2015) | Low | 2 668 | 0.6 | 96.6 | 2.8 | 5 732 | 2.7 | 96.1 | 1.2 | 318 | 1.4 | 93.4 | 5.2 | 829 | 1.8 | 89.6 | 8.6 | |||

| Senegal (2017) | Low | 1 614 | 3.8 | 89.6 | 6.6 | 7 194 | 5.4 | 86.7 | 7.9 | 719 | 2.6 | 92.0 | 5.4 | 807 | 4.3 | 88.0 | 7.7 | |||

| Sierra Leone (2013) | Low | 2 058 | 15.0 | 69.7 | 15.2 | 7 365 | 17.4 | 79.6 | 2.9 | 564 | 16.4 | 77.9 | 5.7 | 1 615 | 12.9 | 82.9 | 4.2 | |||

| South Africa (2016) | Upper middle | 2 847 | 8.4 | 86.6 | 5.0 | 2 696 | 11.2 | 78.6 | 10.2 | 188 | 8.5 | 75.2 | 16.3 | 312 | 4.3 | 73.6 | 22.0 | |||

| Tajikistan (2017) | Lower middle | 337 | 9.9 | 90.1 | 0.1 | 3 761 | 6.6 | 92.7 | 0.7 | 404 | 16.3 | 80.3 | 3.5 | 245 | 17.3 | 76.6 | 6.1 | |||

| Timor-Leste (2016) | Lower middle | 1 084 | 11.5 | 83.7 | 4.8 | 3 990 | 15.2 | 82.2 | 2.6 | 474 | 13.1 | 79.1 | 7.9 | 481 | 15.1 | 77.7 | 7.2 | |||

| Togo (2014) | Low | 563 | 18.1 | 66.2 | 15.7 | 4 228 | 20.5 | 67.0 | 12.5 | 219 | 17.0 | 66.9 | 16.1 | 601 | 17.5 | 60.0 | 22.5 | |||

| Uganda (2016) | Low | 3 060 | 8.6 | 47.4 | 43.9 | 9 152 | 19.8 | 68.6 | 11.5 | 1 637 | 5.5 | 42.3 | 52.3 | 2 860 | 5.1 | 45.1 | 49.8 | |||

| United Republic of Tanzania (2016) | Low | 1 450 | 8.8 | 74.9 | 16.3 | 6 429 | 9.8 | 77.0 | 13.3 | 474 | 8.9 | 69.0 | 22.1 | 716 | 7.7 | 64.7 | 27.6 | |||

| Yemen (2013) | Lower middle | 1 765 | 28.5 | 52.4 | 19.2 | 5 638 | 31.9 | 19.3 | 48.9 | 1 246 | 25.4 | 30.7 | 43.9 | 1 161 | 24.6 | 29.8 | 45.6 | |||

| Zambia (2013–2014) | Lower middle | 3 481 | 7.0 | 88.1 | 4.9 | 8 667 | 10.9 | 84.5 | 4.7 | 1 087 | 8.7 | 86.2 | 5.1 | 2 317 | 7.6 | 86.8 | 5.6 | |||

| Zimbabwe (2015) | Low | 2 980 | 11.9 | 79.8 | 8.3 | 4 283 | 26.3 | 66.4 | 7.3 | 404 | 9.1 | 76.6 | 14.4 | 418 | 7.5 | 69.6 | 22.9 | |||

| All countries | NA | 126 012 | 16.9 | 64.7 | 18.5 | 418 236 | 23.1 | 58.9 | 18.1 | 47 677 | 19.9 | 56.4 | 23.7 | 82 082 | 18.5 | 55.3 | 26.1 | |||

NA: not applicable.

a World Bank classification.15

Notes: Data shown include individual-level sampling weights. Public clinics include any non-hospital public facility type such as: primary or community health centres, welfare centres, health posts, public clinics, mobile clinics, government dispensaries, family welfare centres or public family doctor’s office.

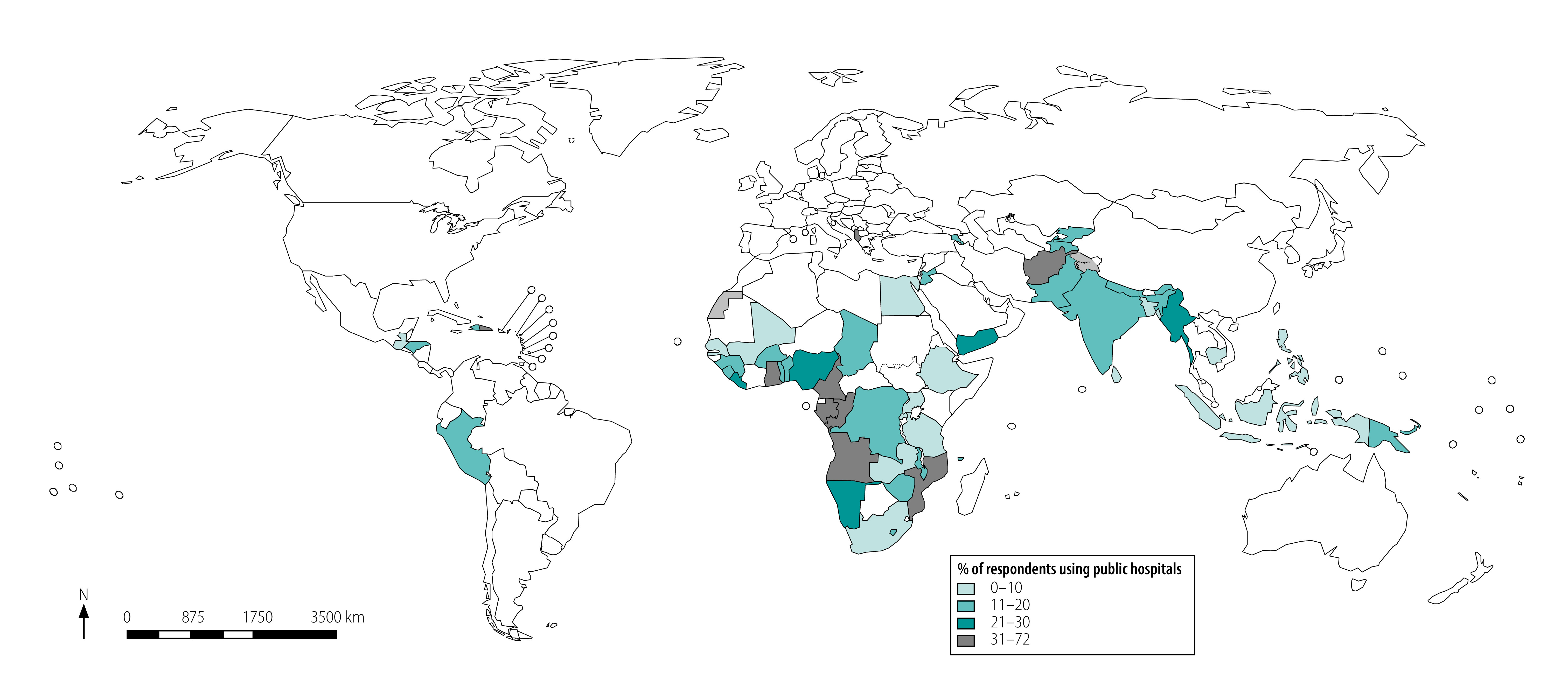

Women in Cambodia, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Mali, Rwanda and Senegal had the lowest hospital use (less than 5% of women on average across the four services) while Albania, Congo, Dominican Republic, Gabon, Maldives and Mozambique had the highest use (more than 35% of women on average across the four services (Fig. 1 and data repository).24

Fig. 1.

Use of public hospitals for four essential primary care services in 56 low- and middle-income countries

Notes: Average across four health services: contraceptives, antenatal care and care for child diarrhoea and child fever or cough.

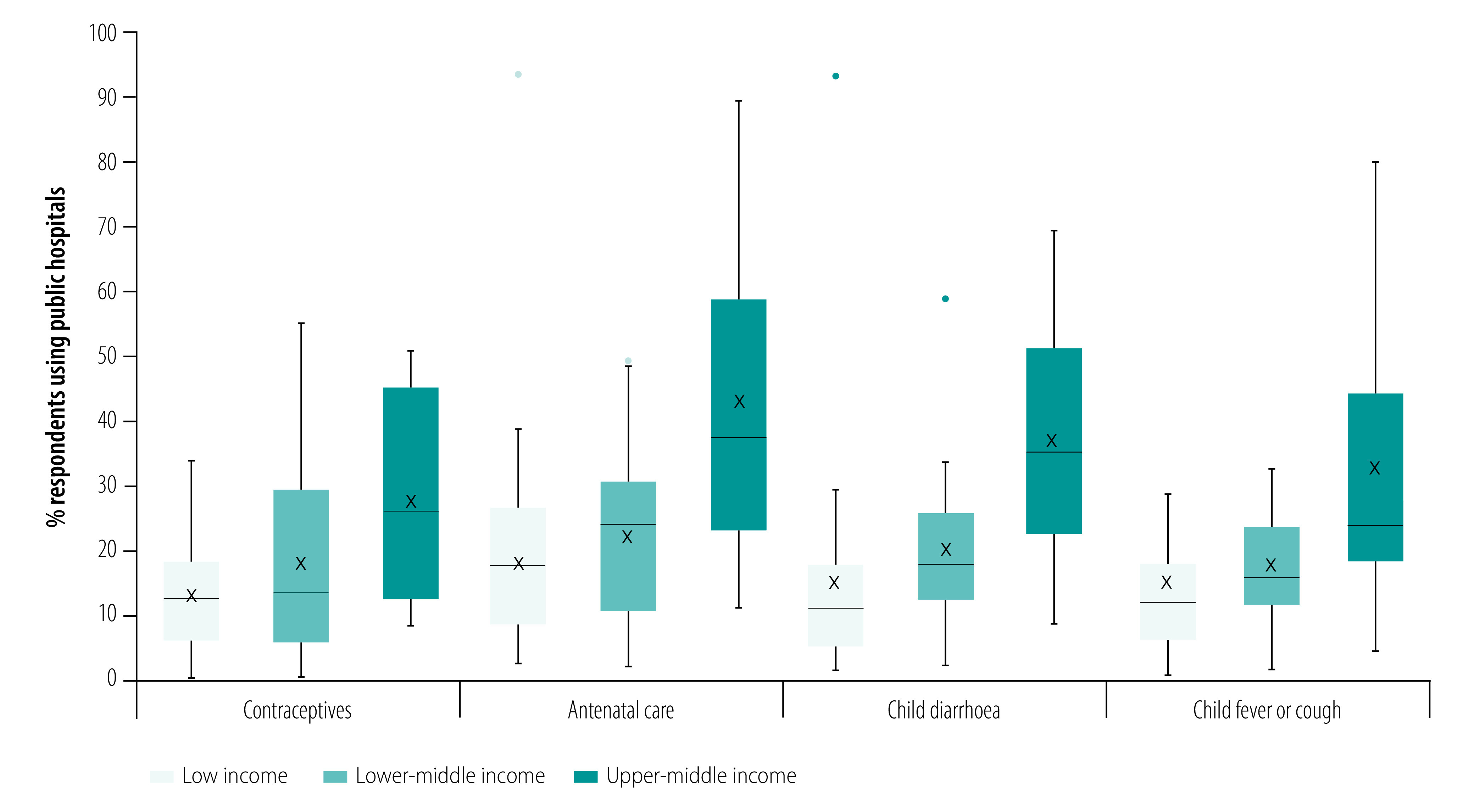

We found that the proportions of women using public hospitals for these four services tended to increase by country income group (Fig. 2). For example, an average of 43.0% of pregnant women used hospitals for routine antenatal care in upper-middle-income countries compared with 18.0% on average in low-income countries.

Fig. 2.

Use of public hospitals for four essential primary care services by country income group in 56 low- and middle-income countries

Notes: Boxes represent 25th percentile, median and 75th percentile. Mean is identified by x markers. Lines show upper and lower adjacent values, while dots are maximum outside values, as defined by Tukey et al., 1977.25

In all four regression models, we found that those visiting hospitals had a higher likelihood of living in urban areas, of being wealthier and of having a secondary education (Table 2). For example, mothers seeking medical advice or treatment for childhood diarrhoea in a hospital were twice as likely to belong to the wealthiest quintile than the poorest quintile (odds ratio, OR: 2.01; 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.77 to 2.29). We also found that women receiving antenatal care in hospitals were more likely to belong to an older age group and be regularly exposed to the media.

Table 2. Results of mixed-effects regression models for the associations between individual and country-level factors and public hospital use for four primary care services in 56 low- and middle-income countries.

| Variable | Contraceptives |

Antenatal care |

Care for childhood diarrhoea |

Care for childhood fever or cough |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of respondents | No. (%) using hospitals | OR (95% CI) | No. of respondents | No. (%) using hospitals | OR (95% CI) | No. of respondents | No. (%) using hospitals | OR (95% CI) | No. of respondents | No. (%) using hospitals | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Individual characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| Urban | 31 106 | 8 857 (28.5) | 2.45 (2.34 to 2.56) | 100 715 | 44 319 (44.0) | 1.96 (1.92 to 2.00) | 8 549 | 3 938 (46.1) | 3.15 (2.91 to 3.40) | 14 750 | 6 574 (44.6) | 3.04 (2.87 to 3.23) | |||

| Rural | 59 174 | 7 207 (12.2) | Ref. | 226 892 | 60 146 (26.5) | Ref. | 21 364 | 4 902 (23.0) | Ref. | 35 791 | 7 923 (22.1) | Ref. | |||

| Wealth quintiles | |||||||||||||||

| Q1 poorest | 19 218 | 1 876 (9.8) | Ref. | 78 375 | 17 656 (22.5) | Ref. | 7 846 | 1 647 (21.0) | Ref. | 12 817 | 2 521 (19.7) | Ref. | |||

| Q2 | 19 937 | 2 462 (12.4) | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.19) | 75 056 | 20 984 (28.0) | 1.28 (1.25 to 1.32) | 6 998 | 1 754 (25.1) | 1.14 (1.04 to 1.25) | 12 018 | 2 925 (24.3) | 1.16 (1.08 to 1.24) | |||

| Q3 | 19 221 | 3 191 (16.6) | 1.34 (1.25 to 1.43) | 68 657 | 22 249 (32.4) | 1.52 (1.48 to 1.56) | 6 265 | 1 872 (29.9) | 1.34 (1.22 to 1.48) | 10 595 | 3 045 (28.7) | 1.29 (1.19 to 1.39) | |||

| Q4 | 17 631 | 4 045 (22.9) | 1.59 (1.48 to 1.71) | 60 216 | 22 876 (38.0) | 1.84 (1.79 to 1.90) | 5 284 | 1 894 (35.8) | 1.53 (1.38 to 1.70) | 8 999 | 3 243 (36.0) | 1.52 (1.40 to 1.65) | |||

| Q5 richest | 14 273 | 4 490 (31.5) | 1.84 (1.70 to 1.99) | 45 303 | 20 700 (45.7) | 2.45 (2.36 to 2.54) | 3 520 | 1 673 (47.5) | 2.01 (1.77 to 2.29) | 6 112 | 2 763 (45.2) | 1.97 (1.78 to 2.17) | |||

| Woman's age, years | |||||||||||||||

| 15–19 | 5 453 | 1 001 (18.4) | Ref. | 20 833 | 5 621 (27.0) | Ref. | 2 115 | 563 (26.6) | Ref. | 3 251 | 871 (26.8) | Ref. | |||

| 20–30 | 42 139 | 7 724 (18.3) | 0.95 (0.87 to 1.03) | 195 174 | 65 995 (33.8) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.06) | 18 805 | 5 924 (31.5) | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.20) | 30 233 | 9 297 (30.8) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | |||

| 31–40 | 31 698 | 5 483 (17.3) | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.04) | 93 228 | 28 195 (30.2) | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.10) | 7 670 | 2 031 (26.5) | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.15) | 14 487 | 3 776 (26.1) | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.12) | |||

| 41–65 | 10 990 | 1 856 (16.9) | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.16) | 18 372 | 4 654 (25.3) | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.16) | 1 323 | 322 (24.3) | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.22) | 2 570 | 553 (21.5) | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | |||

| Any secondary education | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 39 963 | 8 482 (21.2) | 1.13 (1.08 to 1.18) | 130 398 | 54 824 (42.0) | 1.25 (1.22 to 1.27) | 9 541 | 3 688 (38.7) | 1.16 (1.07 to 1.25) | 18 512 | 7 010 (37.9) | 1.20 (1.14 to 1.27) | |||

| No | 50 317 | 7 582 (15.1) | Ref. | 197 209 | 49 641 (25.2) | Ref. | 20 372 | 5 152 (25.3) | Ref. | 32 029 | 7 487 (23.4) | Ref. | |||

| Media exposurea | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 60 070 | 11 562 (19.2) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) | 190 526 | 70 264 (36.9) | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.13) | 16 904 | 5 728 (33.9) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.09) | 29 854 | 9 797 (32.8) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) | |||

| No | 30 210 | 4 502 (14.9) | Ref. | 137 081 | 34 201 (24.9) | Ref. | 13 009 | 3 112 (23.9) | Ref. | 20 687 | 4 700 (22.7) | Ref. | |||

| Country characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Surveyed post-2015 | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 51 548 | 8 664 (16.8) | 0.65 (0.38 to 1.09) | 219 075 | 75 892 (34.6) | 0.67 (0.35 to 1.27) | 19 198 | 5 725 (29.8) | 0.40 (0.20 to 0.79) | 28 940 | 8 578 (29.6) | 0.34 (0.17 to 0.66) | |||

| No | 38 732 | 7 400 (19.1) | Ref. | 108 532 | 28 573 (26.3) | Ref. | 10 715 | 3 115 (29.1) | Ref. | 21 601 | 5 919 (27.4) | Ref. | |||

| Land area, millions km2 | 90 280 | NA | 1.03 (0.66 to 1.59) | 327 607 | NA | 0.74 (0.43 to 1.28) | 29 913 | NA | 1.14 (0.64 to 2.03) | 50 541 | NA | 1.05 (0.59 to 1.86) | |||

| Government effectiveness indexb | 90 280 | NA | 0.36 (0.18 to 0.70) | 327 607 | NA | 0.71 (0.30 to 1.67) | 29 913 | NA | 0.82 (0.34 to 2.02) | 50 541 | NA | 0.83 (0.33 to 2.05) | |||

| Total health expenditure per capita, hundreds int. $c | 90 280 | NA | 1.17 (1.02 to 1.34) | 327 607 | NA | 1.31 (1.11 to 1.55) | 29 913 | NA | 1.10 (0.92 to 1.32) | 50 541 | NA | 1.06 (0.89 to 1.26) | |||

| Share of out-of-pocket expenditure on health, % | 90 280 | NA | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.11) | 327 607 | NA | 1.05 (0.86 to 1.27) | 29 913 | NA | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.19) | 50 541 | NA | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.21) | |||

| Regiond | |||||||||||||||

| East African | 26 020 | 4 218 (16.2) | Ref. | 65 321 | 13 287 (20.3) | Ref. | 8 340 | 1 708 (20.5) | Ref. | 14 251 | 2 924 (20.5) | Ref. | |||

| Eastern Mediterranean | 7 338 | 1 751 (23.9) | 1.64 (0.55 to 4.89) | 14 658 | 8 537 (58.2) | 3.48 (0.90 to 13.55) | 3 566 | 1 750 (49.1) | 4.51 (1.09 to 18.69) | 3 112 | 1 508 (48.5) | 3.59 (0.87 to 14.84) | |||

| European | 529 | 59 (11.2) | 1.06 (0.28 to 3.93) | 8 899 | 2 246 (25.2) | 0.41 (0.08 to 2.05) | 587 | 144 (24.5) | 1.44 (0.27 to 7.83) | 534 | 139 (26.0) | 1.05 (0.20 to 5.64) | |||

| Middle African | 1 988 | 1 098 (55.2) | 4.63 (1.69 to 12.69) | 31 789 | 11 549 (36.3) | 2.10 (0.60 to 7.42) | 2 826 | 1 025 (36.3) | 1.45 (0.39 to 5.45) | 5 048 | 1 744 (34.6) | 1.18 (0.32 to 4.38) | |||

| Americas | 11 596 | 1 642 (14.2) | 0.82 (0.29 to 2.34) | 22 349 | 4 832 (21.6) | 1.15 (0.30 to 4.39) | 2 041 | 394 (19.3) | 0.99 (0.24 to 4.03) | 4 298 | 736 (17.1) | 0.89 (0.22 to 3.59) | |||

| Southern African | 7 845 | 1 498 (19.1) | 0.98 (0.23 to 4.21) | 7 430 | 1 742 (23.5) | 0.25 (0.04 to 1.43) | 655 | 151 (23.0) | 0.42 (0.07 to 2.63) | 1 089 | 242 (22.2) | 0.35 (0.06 to 2.11) | |||

| South East Asia | 20 520 | 3 508 (17.1) | 0.80 (0.30 to 2.12) | 91 325 | 45 083 (49.4) | 1.45 (0.43 to 4.88) | 5 005 | 2 476 (49.5) | 1.50 (0.42 to 5.44) | 10 290 | 4 959 (48.2) | 1.49 (0.41 to 5.39) | |||

| Western African | 9 423 | 1 900 (20.2) | 1.27 (0.57 to 2.84) | 70 854 | 14 739 (20.8) | 0.67 (0.25 to 1.81) | 6 014 | 964 (16.0) | 0.56 (0.20 to 1.60) | 10 254 | 1 891 (18.4) | 0.53 (0.19 to 1.49) | |||

| Western Pacific | 5 021 | 390 (7.8) | 0.56 (0.18 to 1.77) | 14 982 | 2 450 (16.4) | 0.53 (0.12 to 2.34) | 879 | 228 (25.9) | 1.03 (0.22 to 4.90) | 1 665 | 354 (21.3) | 1.06 (0.23 to 4.96) | |||

| Analysis | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | NA | NA | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.10) | NA | NA | 0.07 (0.02 to 0.23) | NA | NA | 0.16 (0.05 to 0.51) | NA | NA | 0.19 (0.06 to 0.64) | |||

| Variance estimate, null model | NA | NA | 1.53 (−0.90 to 3.95) | NA | NA | 1.81 (−0.83 to 4.45) | NA | NA | 1.71 (−0.85 to 4.28) | NA | NA | 1.64 (−0.87 to 4.14) | |||

| Variance estimate, full model | NA | NA | 0.80 (−0.95 to 2.55) | NA | NA | 1.27 (−0.94 to 3.47) | NA | NA | 1.38 (−0.92 to 3.68) | NA | NA | 1.35 (−0.93 to 3.62) | |||

CI: confidence interval; Int. $: international dollar; NA: not applicable; OR: odds ratio; Ref.: reference category.

a Women were categorized as being exposed to the media if they reported doing at least one of the following every week: reading newspapers or magazines, listening to the radio or watching television.

b Government effectiveness index is estimated by the World Bank’s worldwide governance indicators project16 and is expressed in units of a standard normal distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one with higher values corresponding to better effectiveness.

c Total health expenditures per capita were obtained from the World Bank’s world development indicators database15 and are expressed in hundreds of international $.

d World regions were based on World Health Organization classifications and the African Region was divided into four sub-regions based on the United Nations Statistics Division classification.26

Notes: For each health service, we first calculated a null model with no covariates and only a country-specific random effect to model between-country variation in public hospital use.

Among country characteristics, we found that women visiting hospitals to obtain contraceptives and receive antenatal care had a higher likelihood of living in countries with higher health expenditures per capita (OR: 1.17; 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.34 and OR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.11 to 1.55, respectively). Women visiting hospitals to obtain contraceptives were much less likely to live in countries with effective governments (OR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.18 to 0.70). Women choosing hospitals for treatment of child diarrhoea and fever or cough were less likely to live in countries surveyed post-2015, indicating a potential reduction in hospital use over time.

Quality of care

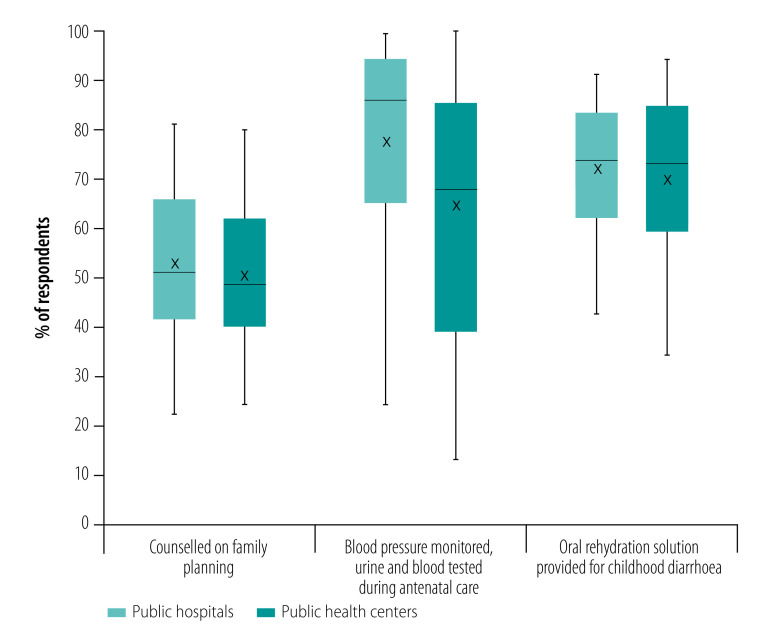

We found that, on average, women who received antenatal care in hospitals were much more likely to report having their blood pressure monitored and urine and blood samples taken compared with women who received antenatal care in health centres (Fig. 3). The differences were statistically significant in 44 of the 56 countries (P < 0.05; data repository).24 Only two countries (Albania and Tajikistan) had higher antenatal care quality in health centres. There were small differences in quality for the other two services, whereby women using hospitals were slightly more likely to report appropriate counselling when obtaining contraceptives or being provided with oral rehydration solutions for their child’s diarrhoea (statistically significant differences in 11 countries each; data repository).24

Fig. 3.

Differences in quality of family planning, antenatal care and sick child care between public hospitals and health centres in 56 low- and middle-income countries

Notes: Boxes represent 25th percentile, median and 75th percentile. Mean is identified by x markers. Lines show upper and lower adjacent values, while dots are maximum outside values as defined by Tukey et al., 1977.25

Data were available from service provision assessment surveys in eight low-income countries (Table 3). We found that those receiving care in hospitals spent more than those who visited health centres – an average of international dollars 1.09 more per visit. Costs were significantly higher in hospitals in seven of the eight countries (data repository).24 Although the number of problems reported was low overall, people using hospitals tended to report more problems on average than users of health centres. Differences were statistically significant in five countries. For example, hospital users were more likely to report experiencing problems with the amount of explanation received from their provider and with their ability to discuss concerns. In addition, in health centres, 81.3% of people reported being very satisfied with the services received, compared with 74.7% in hospitals. Differences in satisfaction were statistically significant in six countries (data repository).24

Table 3. Costs and experiences of care between users of public hospitals and health centres in eight low-income countries.

| Facility used | No. of respondents | Mean (SD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total paid for services, int. $a | Average no. of problems reportedb | Very satisfied with services, %c | |||

| Public hospitals | 11 224 | 2.24 (1.98) | 1.5 (0.5) | 74.7 (17.7) | |

| Public health centres | 21 564 | 1.15 (1.16) | 1.2 (0.4) | 81.3 (16.2) | |

Int. $: international dollar; SD: standard deviation.

a The total paid for services are in international dollars converted using the purchasing power parity conversion rate for the year of the survey.

b Average number of problems reported among the following 11 common problems: wait time, ability to discuss concerns with health worker, amount of explanation provided, visual privacy, auditory privacy, medication availability, hours services are provided, days services are provided, cleanliness of facility, staff treatment and cost of services. We calculated averages using individual sampling weights and countries were weighted equally.

c Satisfaction was measured by the proportion of people who reported being “very satisfied with the services received” as opposed to “more or less satisfied” or “not satisfied.”

Notes: We extracted data from service provision assessment surveys conducted in Democratic Republic of the Congo 2018, Ethiopia 2014, Haiti 2017, Kenya 2010, Malawi 2013, Nepal 2015, Senegal 2017 and United Republic of Tanzania 2015 (see also the data repository).24

Discussion

Using nationally representative surveys from 56 countries, we found that using hospitals for essential primary care services is relatively common in low- and middle-income countries. Around one in five people seeking contraceptives, routine antenatal care or care for minor childhood illnesses went to a public hospital instead of a health centre.

Using hospitals for these services was more common among the wealthiest, urban residents and the most educated women, reflecting that hospital use is highly inequitable. This finding may also reflect a lack of trust and a perception that the quality of care is poor in public health centres.27 An increasing number of studies are showing that people are willing to travel further distances or pay more out-of-pocket to seek what they consider better quality care.28–31 Rising expectations among wealthier populations may lead people aspiring to higher standards of care to bypass health centres, believing that quality is better at hospitals.10 In low- and middle-income countries, hospitals tend to be substantially better equipped, have better diagnostic and laboratory capacity and employ a greater number of physicians and qualified health providers than health centres.32 Hospitals may therefore be seen as a more effective solution to primary care needs. These aspects may especially attract those who can afford to visit hospitals.

In adjusted models, we found that a country’s insurance model (proportion of total health spending that was out-of-pocket) did not influence the source of care. However, the positive association of hospital use with a country’s total health expenditure per capita may reflect that governments are disproportionately directing health resources to hospitals, by building more, investing in quality, or both. The negative association between government effectiveness and people’s use of hospitals for essential health services may capture countries’ ability to successfully manage a larger set of public health facilities, with resulting better services in health centres. Use of hospitals for children with minor illnesses was less likely in countries surveyed post-2015. Inferences related to changes in hospital use over time must be interpreted with caution as these data are cross-sectional and we only included one survey per country.

Our sub-analysis on quality of care showed that in many countries women who attend antenatal care in hospitals are more likely than those in health centres to have their blood pressure monitored and urine and blood tested. This finding may be linked to a lack of diagnostic capacity for urine and blood testing in health centres or poorer competence levels of providers. In some countries, those who sought care in hospitals for childhood diarrhoea were more likely to receive oral rehydration solutions. This result is surprising given that oral rehydration is a simple low-cost intervention with important health benefits that should be easily provided in health centres.33 Our sub-analysis in eight countries showed that hospital users spent nearly twice as much for the same services. This finding reflects greater spending on some combination of provider or booking charges, diagnostic services and prescriptions. The cost differential is likely an underestimate, because travel costs, which are likely to be higher for hospital visits, were not included.34,35

Our findings are consistent with other studies in low- and middle-income settings. In Ethiopia, the national health accounts survey estimated that around 17% of all outpatient care was provided in government hospitals and that urban residents were three times more likely to use hospitals for outpatient services than were rural residents.36 In contrast, rural residents were more likely to attend health centres. In six middle-income Latin American and Caribbean countries, half of respondents had used hospital emergency departments for a condition they considered treatable in primary care in the past 2 years.37 In high-income countries, studies showed that use of hospitals for non-urgent care was generally more common among low-income individuals and those without health insurance.38,39 Use of hospital emergency departments as a usual source of care has been often studied in high-income countries, and is widely recognized as problematic given the higher cost and lack of continuity of care.40,41 Availability of a source of care that performs primary care functions well is associated with more effective, equitable and efficient health services and better overall health for individuals.41,42

Our study covered a large set of lower-income countries using a standardized measurement approach and can therefore provide input for future planning of health systems in low- and middle-income countries. Nonetheless, our study has limitations. First, because the demographic and health surveys do not include specific hospital and clinic categories for the private sector, we were unable to include private hospitals, which likely account for a considerable share of care-seeking in many countries. Second, our analysis was limited to reproductive, maternal and child health services. Even larger proportions of people may be using hospitals for routine care for diabetes, hypertension or human immunodeficiency virus infection, as these services have more recently been added to essential packages in low- and middle-income countries.43 In addition, because of data limitations, our analysis only included women (aged 15–49 years) and children younger than 5 years, and did not include data on primary care services for teenagers or adult men. The true proportion of hospital use for the full range of services offered in health centres is likely considerably higher if other health services and private sector hospitals were included. Facility types and disease severity were also self-reported by women interviewed in demographic and health surveys and may be misclassified. Our regression analyses excluded other factors potentially affecting the magnitude of hospital use, including the type of insurance cover as well as the relative share of private sector facilities. Future research should analyse care-seeking patterns in the light of these potentially confounding factors. Finally, coefficients from multilevel logistic regressions have a conditional, within-cluster interpretation and the magnitude of the association between outcomes and country covariates must be done with caution.44

Our findings have important implications for the design of health systems in low- and middle-income countries and for improving health outcomes. WHO guidance recommends community health centres for provision of people-centred primary care.6,45 Despite this recommendation, we found that many users select hospitals for four services that should be routinely provided with good quality at lower-level facilities. The comprehensive, coordinated, continuous, person-centred care and accessible services that are the hallmark of high-quality primary care may be difficult to provide in hospitals that are geared to more episodic care.46 The services will also almost certainly be more expensive.

Based on these findings, we identify three policy implications. First, the roles of the different levels of care in low- and middle-income country health systems need to be clearly defined. The Lancet Global Health Commission on high-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era recommended redesigning health systems to ensure that the right health services are provided by the right provider, working in the right place in the health system.12 Health system structures and facility roles are often poorly defined in low- and middle-income countries. Many types of public health facilities, from health posts to regional hospitals, are expected to provide the full range of essential primary care services, including family planning, antenatal care, child vaccination and routine chronic disease management. Many hospitals in low- and middle-income countries have outpatient departments dedicated to these services. Meanwhile, some hospitals struggle to provide high-quality emergency and surgical care and to save the lives of those with complex injuries, obstetric complications or illnesses.47–49 In some countries, higher-level hospitals have become overcrowded, while primary care facilities remain underutilized.50 Reorganizing health-service delivery could improve health outcomes and patient confidence by allowing facilities and providers to focus on the services that they are geared towards providing. The role of the private sector should also be considered in planning service delivery.

Second, if people are to be redirected to use health centres for primary care services, there need to be improvements in the competence, comprehensiveness and convenience of care in health centres, including access to diagnostic services and appropriate opening hours. Governments must ensure that patients in health centres receive the core diagnostic services, treatments and counselling they need to maintain and improve their health. These reforms are needed to improve people’s trust in health centres so that they are willing to use them.

Third, if hospitals are to continue providing a substantial proportion of these primary care services, they need to make improvements to the user experience, people-centredness and continuity and integration of care, while costs must be reduced to ensure equitable access.

To stop the drift towards use of hospitals, structural health system investments such as a strong primary care workforce, excellent management and well-equipped health centres that operate in accordance with people’s lives and needs will be essential. High-quality health systems should maximize people’s health, confidence and economic welfare and do so efficiently and equitably. Investing in high quality primary care that people want to use is a critical first step.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hannah Leslie, Anna Gage, Gabriel Loewinger and Kojo Twum Nimako. TTD is also affiliated with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, United States of America.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.The Lancet. The Astana Declaration: the future of primary health care? Lancet. 2018. October 20;392(10156):1369. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32478-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kruk ME, Ling EJ, Bitton A, Cammett M, Cavanaugh K, Chopra M, et al. Building resilient health systems: a proposal for a resilience index. BMJ. 2017. May 23;357:j2323. 10.1136/bmj.j2323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, Dahn BT. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet. 2015. May 9;385(9980):1910–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starfield B. Primary care: concept, evaluation, and policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kruk ME, Porignon D, Rockers PC, Van Lerberghe W. The contribution of primary care to health and health systems in low- and middle-income countries: a critical review of major primary care initiatives. Soc Sci Med. 2010. March;70(6):904–11. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The World Health Report 2008: primary health care (now more than ever). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: https://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/ [cited 2020 May 1].

- 7.WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services. Interim report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/global-strategy/en/ [cited 2020 May 1].

- 8.Uscher-Pines L, Pines J, Kellermann A, Gillen E, Mehrotra A. Emergency department visits for nonurgent conditions: systematic literature review. Am J Manag Care. 2013. January;19(1):47–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kujawski SA, Leslie HH, Prabhakaran D, Singh K, Kruk ME. Reasons for low utilisation of public facilities among households with hypertension: analysis of a population-based survey in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2018. December 20;3(6):e001002. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang J, Wood D, Xiaofeng J, Gifford B. Emerging trends in Chinese healthcare: the impact of a rising middle class. World Hosp Health Serv. 2008;44(4):11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Lu J, Hu S, Cheng KK, De Maeseneer J, Meng Q, et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet. 2017. December 9;390(10112):2584–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018. November;6(11):e1196–252. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao KD, Sheffel A. Quality of clinical care and bypassing of primary health centers in India. Soc Sci Med. 2018. June;207:80–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian SV. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol. 2012. December;41(6):1602–13. 10.1093/ije/dys184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World development indicators [internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2020. Available from: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators [cited 2020 May 1].

- 16.Worldwide governance indicators [internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2020. Available from: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/ [cited 2020 May 1].

- 17.Service Provision Assessment overview. The Demographic and Health Survey program [internet]. Rockville: ICF International; 2007–2016. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/SPA.cfm [cited 2020 Jul 4].

- 18.Tracking UHC. First global monitoring report. Joint WHO/World Bank Group report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/report/2015/ [cited 2020 May 1]. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapoor M, Kim R, Sahoo T, Roy A, Ravi S, Kumar AKS, et al. Association of maternal history of neonatal death with subsequent neonatal death in India. JAMA Netw Open. 2020. April 1;3(4):e202887. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/SPR-3/en/ [cited 2020 May 1]. [PubMed]

- 21.WHO Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/anc-positive-pregnancy-experience/en/ [cited 2020 May 1]. [PubMed]

- 22.Integrated management of childhood illness: chart booklet. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/IMCI_chartbooklet/en/ [cited 2020 May 1].

- 23.Hodgins S, D’Agostino A. The quality-coverage gap in antenatal care: toward better measurement of effective coverage. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014. April 8;2(2):173–81. 10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arsenault C, Kim MK, Aryal A, Faye A, Joseph JP, Kassa M, et al. Supplementary webappendix: Supplementary. materials. Use of hospitals for primary care 2020. [data repository]. San Francisco: Github; 2020. 10.5281/zenodo.3931951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tukey JW. Exploratory data analysis. Reading: Addison–Wesley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Standard country or area codes for statistical use (M49) [internet]. New York: United Nations Statistics Division; 2020. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/#geo-regions2020 [cited 2020 May 1].

- 27.Liu Y, Zhong L, Yuan S, van de Klundert J. Why patients prefer high-level healthcare facilities: a qualitative study using focus groups in rural and urban China. BMJ Glob Health. 2018. September 19;3(5):e000854. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elewonibi B, Sato R, Manongi R, Msuya S, Shah I, Canning D. The distance-quality trade-off in women’s choice of family planning provider in north eastern Tanzania. BMJ Glob Health. 2020. February 13;5(2):e002149. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kruk ME, Hermosilla S, Larson E, Mbaruku GM. Bypassing primary care clinics for childbirth: a cross-sectional study in the Pwani region, United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2014. April 1;92(4):246–53. 10.2471/BLT.13.126417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard KL. Active patients in rural African health care: implications for research and policy. Health Policy Plan. 2014. January;29(1):85–95. 10.1093/heapol/czs137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahabuka C, Kvåle G, Moland KM, Hinderaker SG. Why caretakers bypass Primary Health Care facilities for child care – a case from rural Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011. November 17;11(1):315. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leslie HH, Spiegelman D, Zhou X, Kruk ME. Service readiness of health facilities in Bangladesh, Haiti, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Nepal, Rwanda, Senegal, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2017. November 1;95(11):738–48. 10.2471/BLT.17.191916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fontaine O, Garner P, Bhan MK. Oral rehydration therapy: the simple solution for saving lives. BMJ. 2007. January 6;334 Suppl 1:s14. 10.1136/bmj.39044.725949.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varela C, Young S, Mkandawire N, Groen RS, Banza L, Viste A. Transportation barriers to access health care for surgical conditions in Malawi: a cross sectional nationwide household survey. BMC Public Health. 2019. March 5;19(1):264. 10.1186/s12889-019-6577-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arsenault C, Fournier P, Philibert A, Sissoko K, Coulibaly A, Tourigny C, et al. Emergency obstetric care in Mali: catastrophic spending and its impoverishing effects on households. Bull World Health Organ. 2013. March 1;91(3):207–16. 10.2471/BLT.12.108969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ethiopian health accounts. Household health service utilization and expenditure survey 2015/16. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macinko J, Guanais FC, Mullachery P, Jimenez G. Gaps in primary care and health system performance in six Latin American and Caribbean countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016. August 1;35(8):1513–21. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benahmed N, Laokri S, Zhang WH, Verhaeghe N, Trybou J, Cohen L, et al. Determinants of nonurgent use of the emergency department for pediatric patients in 12 hospitals in Belgium. Eur J Pediatr. 2012. December;171(12):1829–37. 10.1007/s00431-012-1853-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowling TE, Harris M, Watt H, Soljak M, Richards E, Gunning E, et al. Access to primary care and the route of emergency admission to hospital: retrospective analysis of national hospital administrative data. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016. June;25(6):432–40. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poku BA, Hemingway P. Reducing repeat paediatric emergency department attendance for non-urgent care: a systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. Emerg Med J. 2019. July;36(7):435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Wallace LS, Angier H, Carlson MJ, Gold R. Parent and child usual source of care and children’s receipt of health care services. Ann Fam Med. 2011. Nov-Dec;9(6):504–13. 10.1370/afm.1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witter S, Zou G, Diaconu K, Senesi RGB, Idriss A, Walley J, et al. Opportunities and challenges for delivering non-communicable disease management and services in fragile and post-conflict settings: perceptions of policy-makers and health providers in Sierra Leone. Confl Health. 2020. January 6;14(1):3. 10.1186/s13031-019-0248-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Austin PC, Merlo J. Intermediate and advanced topics in multilevel logistic regression analysis. Stat Med. 2017. September 10;36(20):3257–77. 10.1002/sim.7336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/global-strategy/en/ [cited 2020 May 1].

- 46.Bitton A, Veillard JH, Basu L, Ratcliffe HL, Schwarz D, Hirschhorn LR. The 5S-5M-5C schematic: transforming primary care inputs to outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2018. October 2;3 Suppl 3:e001020. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ng-Kamstra JS, Arya S, Greenberg SLM, Kotagal M, Arsenault C, Ljungman D, et al. Perioperative mortality rates in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2018. June 22;3(3):e000810. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Obermeyer Z, Abujaber S, Makar M, Stoll S, Kayden SR, Wallis LA, et al. ; Acute Care Development Consortium. Emergency care in 59 low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2015. August 1;93(8):577–586G. 10.2471/BLT.14.148338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM, Vogel J, Carroli G, Lumbiganon P, Qureshi Z, et al. Moving beyond essential interventions for reduction of maternal mortality (the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health): a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2013. May 18;381(9879):1747–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60686-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu D, Lam TP. Underuse of primary care in China: the scale, causes, and solutions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016. Mar-Apr;29(2):240–7. 10.3122/jabfm.2016.02.150159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]