Abstract

Introduction

Our hospital found itself at the epicentre of the Irish COVID-19 pandemic. We describe the organisational challenges faced in managing the surge and identified risk factors for mortality and ICU admission among hospitalised SARS-CoV-2-infected patients.

Methods

All hospitalised SARS-CoV-2 patients diagnosed between March 13 and May 1, 2020, were included. Demographic, referral, deprivation, ethnicity and clinical data were recorded. Multivariable regression, including age-adjusted hazard ratios (HR (95% CI), was used to explore risk factors associated with adverse outcomes.

Results

Of 257 inpatients, 174 were discharged (68%) and 39 died (15%) in hospital. Two hundred three (79%) patients presented from the community, 34 (13%) from care homes and 20 (8%) were existing inpatients. Forty-five percent of community patients were of a non-Irish White or Black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) population, including 34 Roma (13%) compared to 3% of care home and 5% of existing inpatients, (p < 0.001). Twenty-two patients were healthcare workers (9%). Of 31 patients (12%) requiring ICU admission, 18 were discharged (58%) and 7 died (23%). Being overweight/obese HR (95% CI) 3.09 (1.32, 7.23), p = 0.009; a care home resident 2.68 (1.24, 5.6), p = 0.012; socioeconomically deprived 1.05 (1.01, 1.09), p = 0.012; and older 1.04 (1.01, 1.06), p = 0.002 were significantly associated with death. Non-Irish White or BAME were not significantly associated with death 1.31 (0.28, 6.22), p = 0.63 but were significantly associated with ICU admission 4.38 (1.38, 14.2), p = 0.014 as was being overweight/obese 2.37 (1.37, 6.83), p = 0.01.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented organisational issues for our hospital resulting in the greatest surge in ICU capacity above baseline of any Irish hospital. Being overweight/obese, a care home resident, socioeconomically deprived and older were significantly associated with death, while ethnicity and being overweight/obese were significantly associated with ICU admission.

Keywords: Clinical care, COVID-19, Ethnicity, Obesity, Outcomes, Socioeconomic deprivation

Introduction

On February 29, 2020, the first case of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in Ireland was reported in a woman who had travelled through Dublin Airport on her way to Northern Ireland from Northern Italy [1]. On March 11, the first death of a patient in Ireland—a woman in the east of the country [2]—was confirmed, the same day the World Health Organisation announced that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was a pandemic. Since then, there has been a rapid increase in cases, with over 20,833 confirmed cases and 2768 hospital admissions including 367 ICU admissions and 1265 deaths as of May 1 in the Republic of Ireland [3]. Dublin has become the epicentre of the Irish outbreak with the highest incidence across the country and half of all confirmed cases. Connolly Hospital Blanchardstown (CHB) is a 400-bed academic tertiary care centre, located in the northwest of Dublin, with high levels of socioeconomic deprivation, care homes and non-Irish White and Black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) populations among its large catchment area, contributing to the fact that Dublin northwest has the highest concentration of COVID-19 in Ireland, with 2183 cases and 115 deaths [4]. While initial reports suggest that ethnic minorities may be experiencing more severe COVID-19 outcomes, to date it remains unclear to what degree this association is driven by socioeconomic deprivation.

The first case of COVID-19 pneumonia was confirmed in our hospital on March 13. Here, we present details of all patients admitted to our hospital over the subsequent 6-week period with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and a definite clinical outcome (death or discharge) as of May 1, 2020. We aim to explore risk factors for death in hospitalised patients and risk of ICU admission, as well as share our early experience in managing the surge of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients that required hospital admission, a significant proportion of whom included care home residents and healthcare workers as well as patients from an ethnically diverse population. We describe the unprecedented organisational issues faced by our hospital which, at its peak in early April, saw 43% of all acute medical beds occupied by patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, 159 staff (12% of our WTE) on COVID-19-related leave while having to increase our critical care capacity by 240% from baseline, the largest such increase in Ireland (https://www.noca.ie/audits/irish-national-icu-audit).

Methods

Following confirmation of the first COVID-19 pneumonia diagnosis at our hospital on March 13, our Microbiology Department generated and maintained a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet database detailing all confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection collected by our hospital’s laboratory. Basic demographic data (age, gender, ethnicity), source of referral (community, care home, existing inpatients) and date nasopharyngeal RT-PCR swabs were collected, and admission date, location, ward transfer (including ICU admittance), discharge date and re-admission if applicable were all recorded. An audit of the Emergency Department’s Symphony electronic information software system was carried out to establish ethnicity, healthcare worker (HCW) status, comorbidities, body mass index (BMI), smoking history and medications used in patients presenting with SARS-CoV-2 infection. HCWs were defined as any staff working in any public or private healthcare facility (includes care assistants, cleaners, caterers, home help). The Charlson Comorbidity Index was used to score the severity and number of comorbidities. With the exception of care home residents, all patients admitted to CHB had their relative affluence and deprivation measured using the 2016 Pobal HP Deprivation Index which was calculated from their Eircode or residential address, as recorded from the hospital’s patient electronic record. The Pobal HP Deprivation Index for Small Areas maps socioeconomic data among all residents in the Republic of Ireland and is more homogeneous in its social composition than previous indices with a uniform population size of just under 100 households [5]. Ethical approval was waived on the basis that this clinical research took place during a pandemic emergency.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive summary of patient characteristics at admittance was produced for all patients and stratified by location prior to admission (i.e. community, care home or existing inpatient). The distribution of continuous variables was assessed for normality using histograms and skewness tests. The variables were found to be normally distributed and therefore were summarised using mean (standard deviation [SD]). Categorical variables were summarised using number (%). Admittance characteristics were compared between locations prior to admission using ANOVA tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. The deprivation index was not estimated for care home patients because this Eircode-based score is unlikely to be a reasonable measure of deprivation score for care home residents.

The primary outcome was death in hospital. For each categorical attendance characteristic, the number (%) of survivors and non-survivors was produced. For each continuous attendance characteristic, the mean (SD) for survivors and non-survivors was estimated. Survival analysis was used to test whether there was a difference in the risk of hospital death based on attendance characteristics using a Cox proportional hazards model. Patients still alive at the end of the observation period (May 1, 2020) were censored. Initial analysis showed that age was a strong confounder of the relationship between attendance characteristics and hospital death; therefore, age-adjusted hazard ratios, 95% confidence intervals and two-sided p values are presented. Similar analysis was performed for the secondary outcome of ICU admittance. As people admitted from care homes or as existing inpatients had characteristics that are not necessarily representative of the general population, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by repeating the main analyses with only patients admitted from a community setting included. All analysis was performed in Stata 16.0.

Organisational measures

In our hospital, preparations for the COVID-19 outbreak began in late January 2020 with the establishment of a multi-disciplinary outbreak management team which included Emergency Medicine and Microbiology. Following confirmation of our first COVID-19 inpatient, our hospital was transformed in order to manage a large influx of COVID-19 patients while, at the same time, ensuring safe urgent care for non-COVID-19 patients. In addition to twice daily ICU huddles, a daily ED huddle, three-weekly consultant huddles executive team meetings took place every Monday to Sunday morning in our auditorium to update the COVID-19 management team on the status of all confirmed and suspected patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Discussions took place with regard to Emergency Department; medical and critical care bed capacity; daily personal protective equipment (PPE) stock and usage updates; microbiology, laboratory and infection prevention and control updates; radiology pathways; pharmacy updates on critical care medications; and updates on the hospital’s oxygen capacity. Intensive training and upskilling of all HCWs were facilitated by daily PPE donning and doffing education sessions while nursing ICU up-skill training was arranged for nurses redeployed from the wards to critical care. Our Occupational Health Department provided daily updates regarding on the number of staff self-isolating. Our Human Resources Department coordinated hospital volunteers including former employees, while twenty RCSI medical students volunteered to be part of our ICU proning teams.

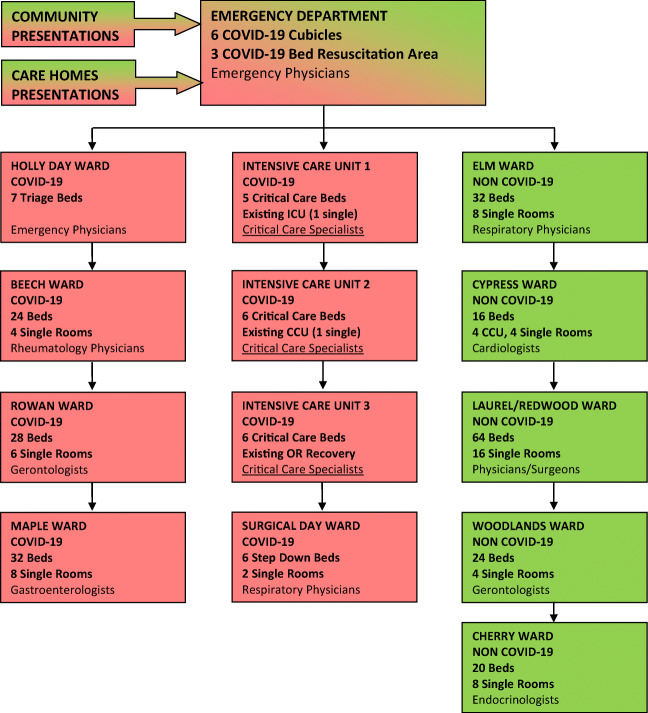

The COVID-19 pandemic forced a major reorganisation of our patient flow (Fig. 1). A 5-cubicle section of ED and the 3-bed ED resuscitation area were cordoned off for all suspected admissions with SARS-CoV-2 infection. On March 20, a 7-bed triage, assessment and isolation area adjacent to the ED for cohorting suspected COVID-19 patients pending results was opened. Suspected COVID-19 patients with an early warning score (EWS) of less than 3 were typically discharged, while those with an EWS greater than 3 were admitted. Our critical care capacity increased by 240%, from 5 to 17 ICU beds making our 6-bed CCU into a 2nd ICU and our Recovery Unit in Theatre into a 3rd ICU making an additional 6 critical care beds available. One operating theatre was kept open for inpatient care or emergency surgery and endoscopy. In tandem with HSE guidelines, our hospital adopted a no visiting policy, and from March 23, all outpatient clinics, ambulatory surgeries, elective admissions and procedures were cancelled and staff leave was cancelled. This enabled our 18 medical consultants and 64 NCHDs to cover a COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 rota. Approximately 40 inpatients who had been identified as delayed discharges prior to the COVID-19 pandemic were moved to care homes in our catchment area, in order to increase medical bed capacity. Eight home wards were re-assigned including three designated COVID-19 wards and five designated non-COVID-19 wards.

Fig. 1.

Reorganisation of Connolly Hospital patient flow

From March 23, all outpatient biologic infusions were moved from the main hospital to a separate infusion facility in our adjacent Ambulatory Paediatric Hospital. On March 25, twice daily in-house SARS-CoV-2 testing was introduced using the Seegene molecular system (Allplex 2019-nCoV assay) for all patients who fit the national testing criteria [6]. This ensured a maximum turnaround time from sampling to test result of 24 h and allowed optimum patient and bed management during the peak of the pandemic. COVID-19 antiviral protocols were established in line with national HSE guidelines, and all clinical pathways were uploaded to the hospital’s X-drive. On March 30, an ED triage tent was installed by the Irish Defence Forces, and the HSE took over the running of all private hospitals to increase inpatient and critical care capacity. Following this, all elective surgery was moved to the Hermitage Medical Clinic, Cappagh Orthopaedic Hospital and the Santry Sports Clinic. On March 31, local guidance was updated to ensure that all HCWs use face masks for all clinical encounters, particularly where social distancing (2 m) could not be maintained.

On April 1, a comfort room was set up for staff by our Social Work Department, peer support sessions were provided in the oratory by the hospital chaplaincy and an isolation unit in City West Hotel was opened for patients discharged from hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection who could not safely self-isolate at home. On April 8, our Surgical Day Ward opened as a High-Dependency Unit to facilitate patients being discharged from ICU. On April 17, hospital policy was amended to test all patients admitted from care homes for SARS-CoV-2 infection, regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms. On April 23, all outpatient endoscopy was transferred to the Bon Secours, and emergency endoscopies were moved to theatre, and on April 29, discharge pathways were established to Cappagh Rehabilitation Unit and the Bon Secours Hospital for ambulatory non-COVID-19 inpatients as well as Clontarf Rehabilitation Unit for less ambulant COVID-19 inpatients.

At its peak on April 6, we had 64 inpatients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection across three designated wards, accounting for 43% of all acute medical beds, while on April 8, 159 staff were registered as being on COVID-19 leave representing 11.9% of our current 1340 whole-time equivalent hospital staff complement. On March 30, 11 ventilated patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were occupying all three ICUs, and the hospital experienced a surge of critically ill patients arriving to its ED department which exceeded our hospital’s critical care capacity requiring the transfer of patients to ICUs in other hospitals identified by the recently established ICU bed information system. This was achieved safely and efficiently by the MICAS service. Figure 2 summarises the total number of COVID inpatients, ventilated ICU COVID patients and a trend line reflecting the number of HCWs on COVID leave between March 11 and May 1, 2020. As of May 1, there were 186 inpatients (53 COVID-19 cases, 116 non-COVID-19 and 17 query COVID-19), 6 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia remained in ICU (4 on ventilators) and a total of 76 staff remained on COVID-19 leave.

Fig. 2.

COVID-19 inpatients, ventilated ICU patients and healthcare workers on COVID-19 leave. Legend Fig. 2. This figure summarises the total number of COVID inpatients (blue bars) peaking on April 6 with 64 COVID inpatients, the number of ventilated COVID ICU patients (orange bars) peaking on March 30 and again on April 15 with 11 ICU patients and the total number of Connolly Hospital healthcare workers on COVID leave (green trend line) peaking on April 8 when 159 members of staff were on COVID leave representing 12% of our hospital staff complement

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Between March 13 and May 1, a total of 382 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases were recorded in the Microbiology database. Two hundred fifty-seven people were admitted with a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection (203 from community, 34 from care homes and 20 existing inpatients). Table 1 shows their descriptive characteristics at admittance. Patients admitted from care homes (mean [SD] = 76.9 years[13.5]) and existing inpatients (mean [SD] = 74.8 years [10.2]) were significantly older than those admitted from the community (mean [SD] = 55.9 years [17.4]; p < 0.001). Existing inpatients (mean [SD] = − 2.1 [8.4]) were also more deprived on average than community patients (mean [SD] = 2.8 [10.2]; p < 0.5) and predominantly male, p = 0.01. Another significant difference at admittance was that 45% of community patients were of a non-Irish White or BAME population compared to 3% of care home and 5% of existing inpatients, (p < 0.001). The ethnicities of the community patients comprised 49 BAME and 42 other White including 33 from the Roma community which included a cluster of infections identified among Roma members of a congregation attending a church service. There were 22 HCWs, all BAME and all admitted from the community. There were 7 healthcare assistants, 6 cleaners, 4 caterers, 3 nurses, 1 doctor and 1 home help. There were no differences in terms of smoking status (p = 0.78) or overweight/obese status (p = 0.87). Comorbidities were present in over three-quarters of our patients with hypertension being the most common comorbidity, followed by type 2 diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease and asthma. Among community patients, 70% had at least one comorbidity, whereas all care home patients and all but one existing inpatient had at least one comorbidity (p < 0.001). Care home patients and existing inpatients also tended to have a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index compared with community patients (p < 0.001). Sustained viral detection in nasopharyngeal samples among some elderly survivors significantly delayed their discharge back to care homes in many cases by several weeks.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics at admittance of 257 COVID-19 patients

| Location prior to admission | All (n = 257) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Community (n = 203) | Care Home (n = 34) | Existing inpatient (n = 20) | p valuea | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age, years | 55.9 (17.4) | 76.9 (13.5) | 74.8 (10.2) | < 0.001 | 60.1 (18.4) |

| Deprivation scoreb | 2.8 (10.2) | – | − 2.1 (8.4) | 0.049 | 2.4 (10.1) |

| N (%c) | N (%c) | N (%c) | N (%c) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 86 (42.4) | 16 (47.1) | 2 (10.0) | 104 (40.5) | |

| Male | 117 (57.6) | 18 (52.9) | 18 (90.0) | 0.013 | 153 (59.5) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White–Irish | 112 (55.2) | 33 (97.1) | 19 (95.0) | 164 (63.8) | |

| White–other | 42 (20.7) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (5.0) | 44 (17.1) | |

| BAME | 49 (24.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 | 49 (24.1) |

| Healthcare worker | |||||

| No | 181 (89.2) | 34 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) | 235 (91.4) | |

| Yes | 22 (10.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.041 | 22 (8.6) |

| Smoker | |||||

| No | 180 (88.7) | 31 (91.2) | 17 (85.0) | 228 (88.7) | |

| Yes | 23 (11.3) | 3 (8.8) | 3 (15.0) | 0.786 | 29 (11.3) |

| Overweight/obese | |||||

| No | 73 (36.0) | 12 (35.3) | 6 (30.0) | 91 (35.4) | |

| Yes | 130 (64.0) | 22 (64.7) | 14 (70.0) | 0.868 | 166 (64.6) |

| At least one comorbidity | |||||

| No | 60 (29.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.0) | 61 (23.7) | |

| Yes | 143 (70.4) | 34 (100.0) | 19 (95.0) | < 0.001 | 196 (76.3) |

| Charlson Index | |||||

| 0 | 62 (30.5) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (5.0) | 64 (24.9) | |

| 1 | 53 (26.1) | 3 (8.8) | 3 (15.0) | 59 (23.0) | |

| 2 | 40 (19.7) | 11 (32.4) | 5 (25.0) | 56 (21.8) | |

| 3 | 25 (12.3) | 8 (23.5) | 3 (15.0) | 36 (14.0) | |

| ≥ 4 | 23 (11.3) | 11 (32.4) | 8 (40.0) | < 0.001 | 42 (16.3) |

Abbreviations: SD standard deviation

There were no missing data for any of the variables, except deprivation score as described below

ap values test for a difference between patients from community, care home and inpatient settings. They are estimated using ANOVA tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables

bDeprivation score was measured using Pobal HP Deprivation Index (PDI), which is an Eircode-based relative measure of deprivation. Deprivation scores are not generated for care home residents

cPercentage out of total number of patients admitted from that location

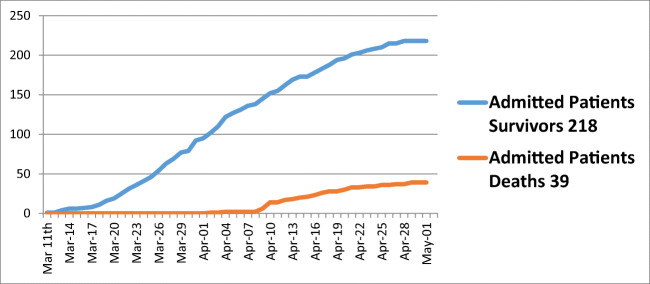

Outcomes during stay

Of the 257 patients admitted with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, there were 218 (84.8%) survivors and 39 non-survivors (15.2%) (Fig. 3). Of the 218 survivors, 174 (79.8%) were discharged and 44 (20.2%) were still in hospital at the end of the May 1 observation period. Mean length of stay did not differ significantly (p = 0.3) between survivors (mean [SD] = 13.5 days [1.3], range = 1 to 121) and non-survivors (mean [SD] = 10.3 [2.0], range = 1 to 65). Of the 31 patients admitted to ICU, 18 (58%) were discharged, 6 (19.3%) were still in ICU as of May 1 and 7 (22.6%) died (Fig. 4). Twenty-five of the 31 patients admitted to ICU required ventilation (80.6%), the majority of whom required frequent proning. The length of stay did not significantly differ (p = 0.3) between patients admitted to ICU (mean [SD] = 16.1 days [1.5]) and those not admitted to ICU (mean [SD] = 12.6 days [1.3]). There was no significant difference in mortality risk between those admitted and not admitted to ICU after adjusting for age (HR [95% CI] = 1.66 [0.69, 4.01], p = 0.26.

Fig. 3.

Total number of Connolly Hospital COVID admissions: survivors and deaths between March 11 and May 1, 2020

Fig. 4.

Total number of Connolly Hospital ICU COVID admissions between March 18 and May 1, 2020

Risk factors for hospital death

Age was a strong predictor of hospital death with a 4% increase in mortality for each year increase in age (HR [95% CI] = 1.04 [1.01, 1.06], p = 0.002; Table 2). Table 2 shows the age-adjusted hazard ratios for risk of hospital death based on other admittance characteristics. Deprivation was a strong predictor of mortality, even after adjustment for age, with a percentage point increase in deprivation associated with a 5% increase in mortality (adjusted HR [95% CI] = 1.05 [1.01, 1.09], p = 0.012). After adjusting for age, having a comorbidity (p = 0.1), gender (p = 0.2) and smoking status (p = 0.24) were not significantly associated with hospital death. There was no significant difference in mortality between community patients and existing inpatients (p = 0.07). However, patients from care homes were more likely (adjusted HR [95% CI] = 2.68 [1.24, 5.60], p = 0.012) to die than community patients after adjusting for age. Some of this excess risk was explained by the additional comorbidity burden among care home residents. After adjusting for Charlson Comorbidity Index and age, care home patients no longer had a significantly increase mortality risk compared with community patients (adjusted HR [95% CI] = 1.96 [0.87, 4.42], p = 0.1.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted risk of death among 257 COVID-19 patients

| Characteristic | Survivors (n = 218) | Non-survivors (n = 39) | Age-adjusted hazard ratioa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, years | 57.7 (17.9) | 73.5 (15.5) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) | 0.002 |

| Deprivation scoreb | 3.3 (9.9) | − 4.3 (9.7) | 1.05 (1.01, 1.09) | 0.012 |

| N (%c) | N (%c) | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| At least one comorbidity | ||||

| No | 60 (98.4) | 1 (1.6) | Baseline | |

| Yes | 158 (80.6) | 38 (19.4) | 5.07 (0.68, 38.00) | 0.114 |

| Charlson Index | ||||

| 0 | 63 (98.4) | 1 (1.6) | Baseline | |

| 1 | 53 (89.8) | 6 (10.2) | 3.61 (0.43, 30.38) | 0.238 |

| 2 | 50 (89.3) | 6 (10.7) | 3.14 (0.37, 26.90) | 0.297 |

| 3 | 25 (69.4) | 11 (30.6) | 7.87 (0.97, 63.95) | 0.054 |

| ≥ 4 | 27 (64.3) | 15 (35.7) | 7.91 (0.99, 63.49) | 0.052 |

| Location prior to admittance | ||||

| Community | 182 (90.0) | 21 (10.3) | Baseline | |

| Care home | 20 (58.8) | 14 (41.2) | 2.68 (1.24, 5.60) | 0.012 |

| Existing inpatient | 16 (80.0) | 4 (20.0) | 0.24 (0.05, 1.11) | 0.067 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 93 (89.4) | 11 (10.6) | Baseline | |

| Male | 125 (81.7) | 28 (18.3) | 1.59 (0.78, 3.27) | 0.203 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White–Irish | 131 (79.9) | 33 (20.1) | Baseline | |

| White–other | 41 (93.2) | 3 (6.8) | 0.91 (0.24, 3.44) | 0.886 |

| BAME | 46 (92.2) | 3 (7.8) | 1.05 (0.19, 6.31) | 0.445 |

| Healthcare worker | ||||

| No | 196 (83.4) | 39 (16.6) | Baseline | |

| Yes | 22 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | – |

| Smoker | ||||

| No | 195 (85.5) | 33 (14.5) | Baseline | |

| Yes | 23 (79.3) | 6 (20.7) | 1.73 (0.70, 4.31) | 0.237 |

| Overweight/obese | ||||

| No | 84 (92.3) | 7 (7.7) | Baseline | |

| Yes | 134 (80.7) | 32 (19.3) | 3.09 (1.32, 7.23) | 0.009 |

Abbreviations: SD standard deviation

There were no missing data for any of the variables, except deprivation score as described below

aAll models adjusted for age, except the model with age as the independent variable of interest which is a univariate model

b221 patients only (missing for all care home patients and 2 existing inpatients). Deprivation score was measured using Pobal HP Deprivation Index (PDI), which is an Eircode-based relative measure of deprivation. Deprivation scores are not generated for care home residents

cPercentage out of total number of patients with that characteristic

Patients who were overweight (BMI 25–30) or obese (BMI > 30) were over 3 times as likely to die in hospital than those with a BMI in the normal range after adjusting for age (adjusted HR [95% CI] = 3.09 [1.32, 7.23], p = 0.009). Further adjusting for their Charlson Comorbidity Index reduced the risk, and it was no longer statistically significant (adjusted HR [95% CI] = 2.20 [0.88, 5.52], p = 0.093; data not in Table). Results were similar in the sensitivity analysis restricted to only those patients admitted from the community. Compared with White Irish people, those of other White (p = 0.886) and BAME (p = 0.405) ethnicities did not have an increased risk of hospital death, after adjusting for age. This was also the case when ethnicity was broken down into further subcategories.

Risk factors for ICU admittance

Table 3 shows risk factors for admittance to ICU. As age increased, the chance of ICU admittance decreased which reflects both increasing comorbidity with age and COVID-19 severity (HR [95% CI] = 0.94 [0.92, 0.97], p < 0.001). After adjusting for age, deprivation (p = 0.196), comorbidity (p = 0.128), gender (p = 0.927) or smoking status (p = 0.527) were not associated with admittance to ICU. Only 1 of the ICU patients was from a non-community setting. Compared with White Irish patients, all other ethnic groups including other White (p = 0.008) and other BAME (p = 0.023) had an approximately fourfold increased risk of ICU admittance after adjusting for age (Table 3). HCWs were also more likely to be admitted to ICU than non-HCWs (age-adjusted HR [95% CI] = 2.71 [1.01, 7.25], p = 0.047); however, of the 5 healthcare workers admitted to ICU, one died. This increased risk of ICU admittance was still present, albeit non-significantly, after adjusting for ethnicity (adjusted HR [95% CI] = 2.87 [0.53, 15.59], p = 0.222; data not in Table). After adjusting for age patients who were overweight or obese were over twice as likely to require admission to ICU (age-adjusted HR (95% CI) = 2.37 (1.37, 6.83), p = 0.01.

Table 3.

Age-adjusted risk of ICU admission in hospital among 257 COVID-19 patients

| ICU admittance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No (n = 226) | Yes (n = 31) | Age-adjusted hazard ratio | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, years | 60.5 (19.1) | 56.7 (11.8) | 0.94 (0.92, 0.97) | < 0.001 |

| Deprivation scoreb | 2.3 (10.5) | 3.2 (7.2) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | 0.196 |

| N (%c) | N (%c) | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| At least one comorbidity | ||||

| No | 59 (96.7) | 2 (3.3) | Baseline | |

| Yes | 167 (85.2) | 29 (14.8) | 3.13 (0.72, 13.57) | 0.128 |

| Charlson Index | ||||

| 0 | 62 (96.9) | 2 (3.1) | Baseline | |

| 1 | 47 (79.7) | 12 (20.3) | 3.72 (0.82, 16.93) | 0.089 |

| 2 | 46 (82.1) | 10 (17.9) | 3.02 (0.64, 14.34) | 0.163 |

| 3 | 30 (83.3) | 6 (16.7) | 2.73 (0.52, 14.18) | 0.233 |

| ≥ 4 | 41 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | 0.44 (0.04, 5.16) | 0.513 |

| Location prior to admittance | ||||

| Community | 173 (85.2) | 30 (14.8) | Baseline | |

| Care home | 33 (97.1) | 1 (2.9) | 0.63 (0.08, 4.96) | 0.661 |

| Existing inpatient | 20 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 95 (42.0) | 9 (29.0) | Baseline | |

| Male | 131 (58.0) | 22 (71.0) | 1.04 (0.47, 2.30) | 0.927 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White–Irish | 153 (93.3) | 11 (6.7) | Baseline | |

| White–other | 34 (77.3) | 10 (22.7) | 4.22 (1.45, 12.31) | 0.008 |

| BAME | 39 (78.4) | 10 (21.6) | 4.58 (1.33, 15.84) | 0.018 |

| Healthcare worker | ||||

| No | 209 (88.9) | 26 (11.1) | Baseline | |

| Yes | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | 2.71 (1.01, 7.25) | 0.047 |

| Smoker | ||||

| No | 206 (90.4) | 22 (9.7) | Baseline | |

| Yes | 20 (69.0) | 9 (31.0) | 1.31 (0.57, 2.99) | 0.527 |

| Overweight/obese | ||||

| No | 85 (37.6) | 4 (12.9) | Baseline | |

| Yes | 141 (62.4) | 27 (87.1) | 2.37 (1.37, 6.83) | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: SD standard deviation

There were no missing data for any of the variables, except deprivation score as described below

ap values test for a difference between patients from community, care home and inpatient settings. They are estimated using ANOVA tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables

b221 patients only (missing for all care home patients and 2 existing inpatients). Deprivation score was measured using Pobal HP Deprivation Index (PDI), which is an Eircode-based relative measure of deprivation. Deprivation scores are not generated for care home residents

cPercentage out of total number of patients with that characteristic

Discussion

The first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic posed many unprecedented challenges in the organisation of an acute Irish hospital, in particular the delivery of acute medical and critical care and the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection among a large caseload of patients from care homes. We maintained adequate stocks of PPE throughout the surge and our reorganisation of critical care facilities allowed all patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who required ICU admission access to mechanical ventilation. We noted a remarkably similar pre-admission disease course in most patients, which reflects the first reports from Wuhan, China [7, 8]. The disease starts with mild respiratory symptoms, fever, and malaise followed by a gradual progressive dyspnoea over the subsequent 5–8 days. Radiological evidence of bilateral infiltrates, elevated levels of C-reactive protein, D-dimer, troponin, ferritin and lactate dehydrogenase and lymphopaenia were more commonly seen in severe illness. During the course of the pandemic, it became clear that elderly patients, including care home and existing inpatients, may present with minimal or atypical symptoms as a result of SARS-CoV-2 infection [7], with a significant proportion of elderly patients presenting with symptoms such as anosmia, ageusia, abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhoea [9, 10]. This was underscored by the development of a large cluster of SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients admitted to our Woodlands ‘nursing home’ ward. This in turn led to the triage criteria in our ED being adjusted accordingly, with introduction of testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection on all ED admission from care homes in mid-April extended to all ED admissions by end of April.

Advanced age has been reported as an independent predictor of mortality in COVID-19 [11], as it was with SARS and MERS [12, 13]. Our initial analysis showed that age was such a strong confounder of the relationship between hospital admission and death that age-adjusted hazard ratios were calculated. Age-dependent defects in T cell and B cell function and the excess production of type 2 cytokines could lead to a deficiency in the hosts’ ability to control viral replication, potentially leading to poor outcome [14]. While our youngest patients requiring hospital admission were aged just 18 years, our survivor group included a 99-year-old man who was successfully discharged home 5 days after ED admission.

Our experience also replicates the established association between obesity and COVID-19 mortality with a threefold increased risk for death and ICU admittance among our hospitalised patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who were either overweight or obese. Similar to other studies, we found a higher prevalence of being overweight or obese among the 31 patients requiring admission to ICU. This contributed to the mechanical problems of having to manage obese patients who require mechanical ventilation and frequent proning [15, 16]. Earlier reports have identified a threefold association between obesity and severe COVID-19 illness, with a dose-effect relationship between increasing BMI and the proportion of patients with severe illness [17]. Zheng and colleagues recently reported that the presence of obesity in patients with fatty liver was associated with a sixfold increased risk of severe COVID-19 illness and this association remained significant even after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia [18]. There is increasing evidence that the IL-6-mediated ‘cytokine storm’ promoted by the activation of CD14+ and CD16+ inflammatory monocytes [8, 19] may play a key role in mediating the systemic inflammatory response syndrome in obese patients with severe COVID-19 illness. In obese patients, increased inflammatory activity in the liver and visceral fat is independently correlated with increased levels of IL-6 [20], which might have an additive/synergistic role in promoting greater severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection. While additional studies are needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms between obesity and poorer outcomes with SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is conceivable that the secretion of hepatokines or the altered secretion of inflammatory lipid mediators in obese patients with metabolic syndrome or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may also contribute to current observations [21].

Our study found that socioeconomic deprivation was a strong predictor of mortality, even after adjustment for age, with a percentage point increase in deprivation associated with a 5% increase in COVID-19 mortality. By contrast, compared with White Irish people, those of other White and BAME ethnicities did not have an increased risk of hospital death. There is growing evidence from both the USA and the UK that the adverse outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic are falling disproportionately on more disadvantaged groups, particularly those from ethnic minorities. In Chicago, around 70% of deaths have involved people of Black origin despite this ethnic group making up only 30% of the population [22]. Estimates suggest that American counties where Black residents are in the majority have a sixfold higher rate of death due to COVID-19 compared to counties with predominantly White residents [23]. In the UK, 19% of deaths occurring in hospital have involved individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds, even though these groups make up only 14% of the population [24]. Forty-five percent of our COVID patients admitted from the community were from non-Irish ethnic groups: BAME (24%), non-Irish White (21%) including Roma (16%) compared to 5%, 10% and 0.1%, respectively, expected for the proportion of BAME, non-Irish White and Roma in the general Irish population [25]. In our study, ethnic minority groups had an approximately fourfold increased risk of ICU admittance reflecting the fact that almost two-thirds of all patients admitted to ICU were non-Irish including 10 patients from the Roma community. Recent UK data reported BAME groups accounted for 35% of all patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in critical care units in England [26]. The extent to which higher COVID-19 mortality in ethnic minority groups is primarily due to socioeconomic deprivation is not fully understood and there has been little or no research investigating whether poverty itself is an independent risk factor for COVID-19-associated mortality. The same risks such as household overcrowding, increased comorbidities including diabetes and obesity, unequal access to healthcare and reliance of public transport are equally associated with living in deprivation as well as ethnicity. Recent analysis by the University of Liverpool’s Department of Public Health and Policy reported significantly higher COVID-19 mortality rates among local authorities with a greater proportion of residents experiencing socioeconomic deprivation and with a greater proportion of residents from ethnic minority backgrounds [27]. Interestingly, they reported that the negative effects of socioeconomic deprivation was twice that of belonging to a BAME group with each percentage point increase in income deprivation associated with a 2% increase in COVID-19 mortality while each percentage point increase in the proportion of the population from BAME backgrounds associated with a 1% increase in COVID-19 mortality. Our findings similarly suggest that socioeconomic deprivation is a more significant factor in determining COVID-19 mortality than belonging to an ethnic group. Indeed sub-analysis of our two largest ethnic subgroups, the socioeconomically deprived Roma cluster of 34 patients (Deprivation Index − 0.21) and the 34 more affluent Asian patients (Deprivation Index + 6.25) including 22 healthcare workers underscores the critical importance of deprivation in determining poor COVID-19 outcomes. While 10 of the Roma cluster required admission to ICU (29.4%) and 3 died (8.8%), only 6 of the Asian subgroup required admission to ICU (17.6%) and 1 died (2.9%), p = 0.03.

Finally, while 13% of our hospital admissions were from care homes, 36% of our deaths were among care home patients reflecting the fact that care home residents were almost 3 times more likely to die than community patients after adjusting for age. Some of this excess risk was explained by the additional comorbidity burden and age profile among care home residents and nationally may relate to a lower staffing ratios coupled with a relative lack of personal protection equipment compared to acute hospitals. Despite blanket visitor restrictions for care homes being introduced more quickly in Ireland than in any other country, clusters of SARS-CoV-2 infection developed in over 230 of the country’s 540 care homes with Ireland having one of the highest rates of reported care home COVID-19 deaths in the world with 62% of COVID-19 deaths in Ireland associated with care homes, a figure surpassed only by Canada, where 82% of deaths occurred in care home settings [28].

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented organisational issues for our hospital which at one stage accounted for admissions occupying 45% of all our acute medical beds, our ICU requiring the greatest increase in capacity of any ICU in Ireland and 12% of our staff requiring COVID-19-related leave. Being overweight/obese, a care home resident, socioeconomically deprived and older were significantly associated with death, while ethnicity and being overweight/obese were significantly associated with ICU admission. Our findings have important implications for healthcare planning for future epidemics and resource allocation as we now move into a continued phase of testing and tracing of SARS-CoV-2 cases. Our experience has demonstrated that our hospital’s critical care and respiratory HDU capacity needs to be rapidly expanded in advance of future surges, with particular attention paid to the large numbers of care home residents and disadvantaged groups in our catchment area with rapid testing of all hospital admissions, existing inpatients and discharges as well as healthcare workers facilitated.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Danielle Bodicoat, PhD, Consultant Statistician as well as our Hospital and Nursing Management Staff; Ms. Barbara Keogh Dunne, Hospital General Manager; Marie Murray, Chief Operating Officer; and Judy McEntee, Director of Nursing.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived on the basis that this clinical research took place during a pandemic emergency.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.HSE Update. First case of COVID-19 diagnosed in east of Ireland. RTE News 29 February 2020

- 2.Cullen P. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/coronavirus-first-death-confirmed-in-ireland-as-who-declares-a-pandemic-1.4199223. Accessed 25 May 2020

- 3.Department of Health Coronavirus Update: 34 more coronavirus deaths in Ireland as 221 new cases announced. RTE News 1st May 2020

- 4.Power J. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/highest-covid-19-incidence-recorded-on-north-side-of-dublin-1.4261097. Accessed 25 May 2020

- 5.Haase T, Pratschke J (2017) The 2016 Pobal HP Deprivation Index for Small Areas (SA) Introduction and Reference Tables

- 6.COVID-19 Risk assessment for use in a hospital setting. http://www.hpsc.ie. Accessed 25 May 2020

- 7.Wu Z, McCoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu K, Chen Y, Lin R, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect. 2020;80(6):E14–E18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin X, Lian J-S, Hu J-H, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut. 2020;69(6):1002–1009. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi KW, Chau TN, Tsang O, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in 267 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:715–723. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong KH, Choi JP, Hong SH, et al. Predictors of mortality in Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Thorax. 2018;73:286–289. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opal SM, Girard TD, Ely EW. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis in elderly patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 7):S504–S512. doi: 10.1086/432007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronoavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity. 2020;28(7):1195–1199. doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palaiodimos L, Kokkinidis DG, Li W, et al. Severe obesity is associated with higher in-hospital mortality in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 in the Bronx, New York. Metabolism. 2020;108:154262. doi: 10.1016/j.metab.2020.154262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao F, Zheng KI, Wang XB, et al. Obesity is a risk factor for greater COVID-19 severity. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):e72–e74. doi: 10.2337/dc20-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng KI, Gao F, Wang XB, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for greater severity of COVID-19 in patients with metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2020;154244:108. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng G, Zheng KI, Yan QQ, et al. COVID-19 and liver dysfunction: current insights and emergent therapeutic strategies. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2020;8(1):18–24. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2020.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Poorten D, Milner KL, Hui J, et al. Visceral fat: a key mediator of steatohepatitis in metabolic liver disease. Hepatology. 2008;48:449–457. doi: 10.1002/hep.22350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen F, Esmaili S, Rogers GB, et al. Lean NAFLD: a distinct entity shaped by differential metabolic adaptation. Hepatology. 2020;71(4):1213–1227. doi: 10.1002/hep.30908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yancy CW (2020) COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 10.1001/jama.2020.6548 published online April 15 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Thebault R, Tran AB, Williams V (2020) The coronavirus is infecting and killing black Americans at an alarmingly high rate. Washington Post. published online April 7. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/07. Accessed 25 May 2020

- 24.NHS England. Statistics: COVID-19 Daily Deaths. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statisticalwork-areas/covid-19-daily-deaths. Accessed 25 May 2020

- 25.Ireland 2016 Census. https://www.cso.ie. Accessed 25 May 2020

- 26.Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre. ICNARC report on COVID-19 in critical care: 17 April 2020. 2020. https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports

- 27.Rose TC, Mason K, Pennington A et al (2020) Inequalities in COVID-19 mortality related to ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation. MedRxIV. 10.1101/2020.04.25.20079491

- 28.Cullen P. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/ireland-has-one-of-the-highest-rates-of-covid-19-deaths-in-care-homes-in-world-1.4260140. Accessed 25 May 2020