Abstract

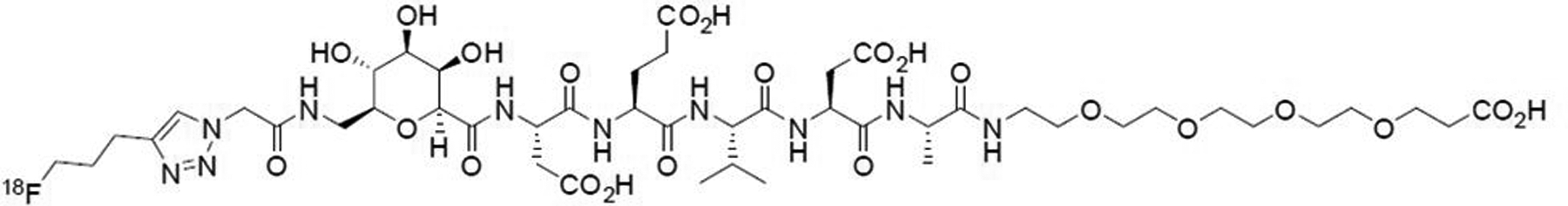

18F-CP-18 or (18S,21S,24S,27S,30S)-27-(2-carboxyethyl)-21-(carboxymethyl)-30-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6S)-6-((2-(4-(3-[F18]fluoropropyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)acetamido)methyl)-3,4,5-trihydroxytetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-carboxamido)-24-isopropyl-18-methyl-17,20,23,26,29-pentaoxo-4,7,10,13-tetraoxa-16,19,22,25,28-pentaazadotriacontane-1,32-dioic acid is being evaluated as a tissue apoptosis marker for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. The purpose of this study was to determine the biodistribution and estimate the normal-organ radiation absorbed doses and effective dose from 18F-CP-18.

Methods:

Successive whole-body PET/CT scans were performed at approximately 7, 45, 90, 130, and 170 minutes after intravenous injection of 18F-CP-18 in seven healthy human volunteers. Blood samples and urine were collected between the PET/CT scans, and the biostability of 18F-CP-18 was assessed using high-performance liquid chromatography. The PET scans were analyzed to determine the radiotracer uptake in different organs. OLINDA/EXM software was used to calculate human radiation doses based on the biodistribution of the tracer.

Results:

18F-CP-18 was 54% intact in human blood at 135 minutes after injection. The tracer cleared rapidly from the blood pool with a half-life of ~30 minutes. Relatively high 18F-CP-18 uptake was observed in the kidneys and bladder, with diffuse uptake in the liver and heart. The mean standardized uptake values (SUVs) in the bladder, kidneys, heart and liver at ~50 minutes after injection were approximately 65, 6, 1.5, and 1.5, respectively. The calculated effective dose was 38±4 μSv/MBq with the urinary bladder wall having the highest absorbed dose at 536±61 μGy/MBq using a 4.8-hr bladder voiding interval for the male phantom. For a 1-hr voiding interval, these doses were reduced to 15±2 μSv/MBq and 142±15 μGy/MBq, respectively. For a typical injected activity of 555 MBq, the effective dose would be 21.1±2.2 mSv for the 4.8-hr interval, reduced to 8.3±1.1 mSv for the 1-hr interval.

Conclusion:

18F-CP-18 cleared rapidly through the renal system. The urinary bladder wall received the highest radiation dose and was deemed the critical organ. Both the effective dose and the bladder dose can be reduced by frequent voiding. From the radiation dosimetry perspective, the apoptosis imaging agent 18F-CP-18 is suitable for human use.

Keywords: 18F-CP-18, Biodistribution, Internal Dosimetry, Apoptosis Marker, PET

Programmed cell death, known as apoptosis, is a regulated cellular mechanism that maintains cell population homeostasis and prevents the proliferation of unwanted or damaged cells (1). When apoptosis becomes unregulated, biological dysfunction ensues and is a contributing factor in the onset of autoimmune diseases, ischemic heart failure and even transplant rejection. A cell’s apoptotic potential can also be reduced or even halted, a common trait of cancer cells as they progress into malignant phenotypes (2, 3).

The apoptotic process invokes distinct biochemical alterations triggered by either extrinsic signaling via the death receptor or through intrinsic pathways via mitochondrial signaling. Regardless of how apoptosis is initiated, the signaling pathways ultimately converge at the execution phase which commits the cell to undergo apoptosis and eventually die. Interestingly, apoptosis directed via the mitochondria initiates the release of pro-apoptotic proteins which activates a family of cysteinyl aspartate proteases (caspases) as critical mediators of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. While caspase proteins are involved in the initiation of apoptosis (caspase −2, −8, −9, −10), the executioners (caspase-3, −6, −7) cleave multiple intracellular substrates to provoke the apoptotic cascade. Caspase-3, as a downstream apoptosis effector, cleaves key proteins involved in DNA repair (PARP), signaling proteins (Akt, Ras) and cell cycle regulators (p27Kip1). The detection of activated caspase-3 could therefore be a valuable and specific tool for identifying apoptotic cells prior to the morphological tissue changes.

Several 18F-labeled positron emission tomography (PET) imaging agents have been developed for the in vivo detection of apoptosis. The PET-labeled agents 18F-ML10 (4–6), 18F-C2A (7), 18F-annexin-V(8–10) and 18F-FBnTP (11, 12) detect key apoptotic pathways involved in membrane imprints (13), membrane blebbing or mitochondrial membrane potential but do not specifically target members of the caspase family. A separate class of PET imaging agents based on the small-molecule isatin scaffold has been developed including 18F-AF-110(14), 18F-ICMT-11 (15, 16), 11C-WC-98, 18F-WC-II-89 and 18F-WC-IV-3 (14, 17–19). The utility of these 18F-radiolabeled isatins as PET apoptosis imaging agents has been described previously (15, 16, 19–21). Several isatin-based radiotracers are reported to undergo hepatic-based metabolism and gut clearance, which may limit abdominal imaging applications (15, 16). In addition, radiolabeled isatins can potentially bind other cysteine proteases (e.g. cathepsins) which may lower the specificity of these tracers in imaging apoptosis (22).

18F-CP-18 was designed as a caspase-3 peptide substrate, similar in principle to fluorescent reporters that are used in caspase-3 activity assays. 18F-CP-18 bears the tetra-peptidic caspase-3 recognition sequence (“D-E-V-D”), which has high specificity for caspase 3 (23), and a polyethylene glycol (PEG) chain to facilitate membrane transport into cells, which is necessary as the high polar DEVD peptide sequence itself poorly diffuses across cell membranes. Even though 18F-CP-18 contains multiple peptide functional groups, the tracer is readily radiolabeled with 18F using click-chemistry, a technique that employs primary azides and terminal alkynes in the presence of Cu(I) to selectively form 1,2,3-triazoles (24–26). From a mechanistic standpoint, the cell permeating PEG moiety facilitates the internalization of 18F-CP-18 into cells undergoing cleavage in the presence of active intracellular caspase-3. This cleavage step effectively traps the polar radiolabeled fragment within the cell as a function of caspase-3 activity. As more 18F-CP-18 is cleaved inside the dying cell, more labeled fragments are accumulated resulting in signal enhancement. The localization of 18F-CP-18 in apoptotic tissues has been previously evaluated in preclinical models (27). Further exploration of its use as an apoptosis marker in patients is warranted.

The main goal of this study was to determine the biodistribution and dosimetry of 18F-CP-18 in humans using PET.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Radiopharmaceutical Preparation

The name of the investigational product being studied in this protocol is 18F-CP-18, or (18S,21S,24S,27S,30S)-27-(2-carboxyethyl)-21-(carboxymethyl)-30-((2S,3R,4R,5R,6S)-6-((2-(4-(3-[F18]fluoropropyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)acetamido)methyl)-3,4,5-trihydroxytetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-carboxamido)-24-isopropyl-18-methyl-17,20,23,26,29-pentaoxo-4,7,10,13-tetraoxa-16,19,22,25,28-pentaazadotriacontane-1,32-dioic acid. The chemical structure of 18F-CP-18 is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structure of 18F-CP-18

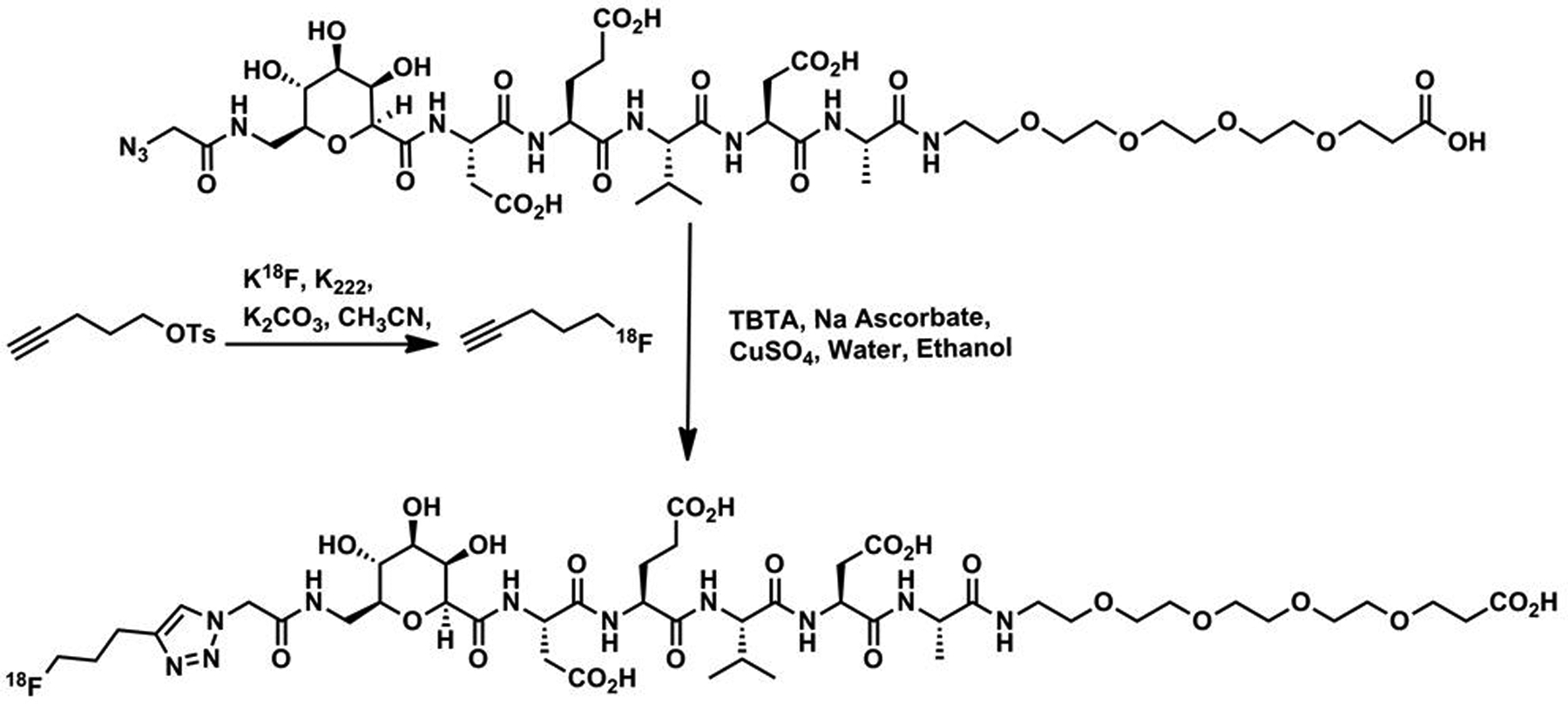

18F-labeling was performed in an automated synthesis module having minor hardware reconfigurations. A solution of anhydrous 18F-fluoride complexed with Kryptofix® 222 and potassium carbonate in acetonitrile was reacted with pent-4-yn-1-yl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate to generate 18F-fluoropentyne. This 18F-labeled intermediate was then reacted with the CP-18 azide precursor, sodium ascorbate, CuSO4 and TBTA dissolved in a solution of ethanol:water:acetonitrile (See Figure 2). The crude reaction mixture was purified via semi-preparative HPLC and reformulated using a C18 SepPak cartridge to achieve a final formulation of 18F-CP-18 in a maximum of 10% ethanol:water (v/v). The solution was then processed through a 0.22 μm sterile filter into a sterile vial. The average decay-corrected radiochemical yield of 18F-CP-18 was 18.7%, and the average specific activity was 171,093 MBq/μmol (n=7).

FIGURE 2.

Synthesis of 18F-CP-18 from Precursor

Subjects

The study was approved by the Research Review Committee, Institutional Review Board and Radiation Safety Committee of Fox Chase Cancer Center. Seven healthy volunteers (5 female, 2 male) with ages 50±9 years (mean± SD, age range 31–55 years) were included in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. The subjects’ weights were 71±8 kg (range 59–82 kg). All subjects were healthy based on medical history, physical examination, EKG, urinalysis, and standard blood tests.

PET/CT Acquisition and Image Analysis

Following the intravenous injection of 604±74 MBq (range 537–699 MBq) of 18F-CP-18 to the volunteers, five successive whole-body PET/CT scans were performed on a Siemens Biograph Truepoint 16 PET/CT Scanner (Siemens Healthcare). A very low mA setting on the scanner was used to perform the CT scans for attenuation correction and organ localization. The helical CT scan acquisition parameters were: 130 kVp, 20 mA, 0.6 sec rotation, pitch =1.

The whole-body PET scans were acquired in 3-D mode and ranged from the top of the head down to mid-thigh. The five whole-body scans were conducted at approximately 7, 45, 90, 130, and 170 minutes after injection. The scan time was 1.5 minutes per bed position and each scan covered 8 or 9 bed positions. In addition, after the first whole-body scan, a PET/CT scan of mid-thigh to toes was performed. Blood pressure, body temperature, respiratory rate, pulse and EKG were monitored before the administration of 18F-CP-18 and following the first, second, and last PET/CT scans, and then at 24 hrs post-dose.

Blood and urine were collected before the radiotracer injection and in the breaks between the PET scans. Urine was also collected at the end of the last PET scan. Samples of urine were assayed in a well counter to estimate the excreted activity in urine. High-performance liquid chromatography was performed to determine the amounts of intact 18F-CP-18 and its radioactive metabolites in the plasma. Briefly, the activity of the whole blood samples was measured in a well counter as counts per minute. Of the seven blood samples submitted for analysis, one sample was not analyzed due to technical difficulties with the HPLC instrumentation. For the remaining six blood samples, the whole blood was centrifuged at 3,500 RPM for 5 minutes to separate plasma from whole cells. The plasma fraction was removed and placed in a separate, empty, pre-weighed tube to record the weight of plasma. An aliquot of plasma (400 μL) was removed followed by spiking the aliquot with non-radioactive CP-18 standard (16 μl of a 1 mg/mL aq. stock solution) and acetonitrile (100 μL). After vortexing the sample for 30 seconds and centrifuging at 13,000 RPM for 8 minutes to separate proteins from plasma, the plasma supernatant was removed, weighed and the counts per minute of pellet and extract were measured. An aliquot (50–100 μl) of the processed plasma sample was injected into the HPLC loop (Agilent 1100 HPLC system equipped with a Luna C18 analytical column (10 μm, 250× 4.5 mm), mobile phases A: Water w/ 0.05% TFA, B : Acetonitrile w/ 0.05% TFA , gradient 95% A to 50% A in 15 min, UV 200 or 206 nm, Flow rate : 1 mL/min). The radioHPLC eluent was collected in one minute fractions and individually counted and the percent of plasma-borne activity in the form of parent compound (i.e.18F-CP-18) and in the form of metabolites was extracted from the radioHPLC traces.

The PET scans were reconstructed to 62 cm display field of view using the Siemens TrueX reconstruction algorithm with 21 subsets and 2 iterations and a 4 mm FWHM Gaussian post-processing filter. The reconstruction included corrections for random coincidences and scatter. Attenuation correction was applied based on the low-dose CT. The accuracy of the activity in the PET images was verified by summing the activity in the first whole-body PET scan and the PET scan from mid-thigh to toes, and comparing the total-body activity thus calculated to the decayed injected activity.

The PET images for the middle time point for each patient were displayed on an imaging workstation. For each of the following organs including brain, liver, heart, spleen, kidneys, bladder, breasts (for females), and testes (for males), volume regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn. The PET images for other time points were displayed and registered with this PET scan to transfer the respective volume ROIs and determine the total activity in each organ. Adjustments to the individual ROIs were made to ensure the inclusion of the respective organs. The percent of the injected activity in each organ was determined at each imaging time point.

Normalized Number of Disintegrations

The percent administered activity for each organ for each time point was fitted to an exponential or sum of exponentials function in OLINDA/EXM (Organ Level Internal Dose Assessment) software (28) to determine the total number of disintegrations per unit administered activity, hereafter referred to as ‘normalized number of disintegrations’. Activity in the ‘remainder of body’ was calculated for each time point as the injected activity minus the activity in all the source organs and in collected urine. The half-times for biological excretion were computed by exponential fitting of injected activity minus accumulated urine activity as a function of time. The 1.0-hr and 4.8-hr bladder voiding intervals in OLINDA/EXM were used to determine the normalized number of disintegrations in bladder. Absorbed doses to the various organs were calculated by entering the normalized number of disintegrations of all source organs for each subject into OLINDA/EXM, using the standard adult male and female models.

RESULTS

The injection of 18F-CP-18 (604±74 MBq) in the seven subjects produced no clinically significant effects on either the vital signs (blood pressure, temperature, respiratory rate, pulse, and EKG) or blood tests during the 3 hr observation period following administration and in the follow-up visit at 24 hours.

The analysis of plasma samples of 6 healthy human subjects showed that the 18F-CP-18 metabolized slowly with the percentage of plasma-borne activity in the form of 18F-CP-18 decreasing from 99% to 52% from 5 to 135 min post-injection. Based on these plasma activity measurements, 18F-CP-18-derived activity exhibited a clearance half-time of ~30 minutes. The radioHPLC trace indicated that one metabolite was present in plasma along with the parent compound. (see Supplemental Figure 1). Based on the relative retention time of the metabolite peak, the plasma metabolite is tentatively assigned as the fragment cleaved between “DE” and “VD”. This pattern of cleavage is consistent with metabolites observed in mice for which those metabolites were identified by mass spectroscopy (data not shown). Urine analysis revealed the presence of the parent tracer ranging from 37% at 35 minutes to 21% at 135 minutes (see Supplemental Figure 1). The urine samples contained predominantly two major metabolites in combined percentages of 63% and 79% after 35 and 135 minutes, respectively. The enrichment of metabolites in the urine relative to the parent compound suggests a faster clearance rate for the metabolites relative to the intact tracer. Again, based on relative retention time analysis of the metabolite signals, these fragments are tentatively assigned as the “DE” fragment and the parent tracer minus the PEG group, respectively.

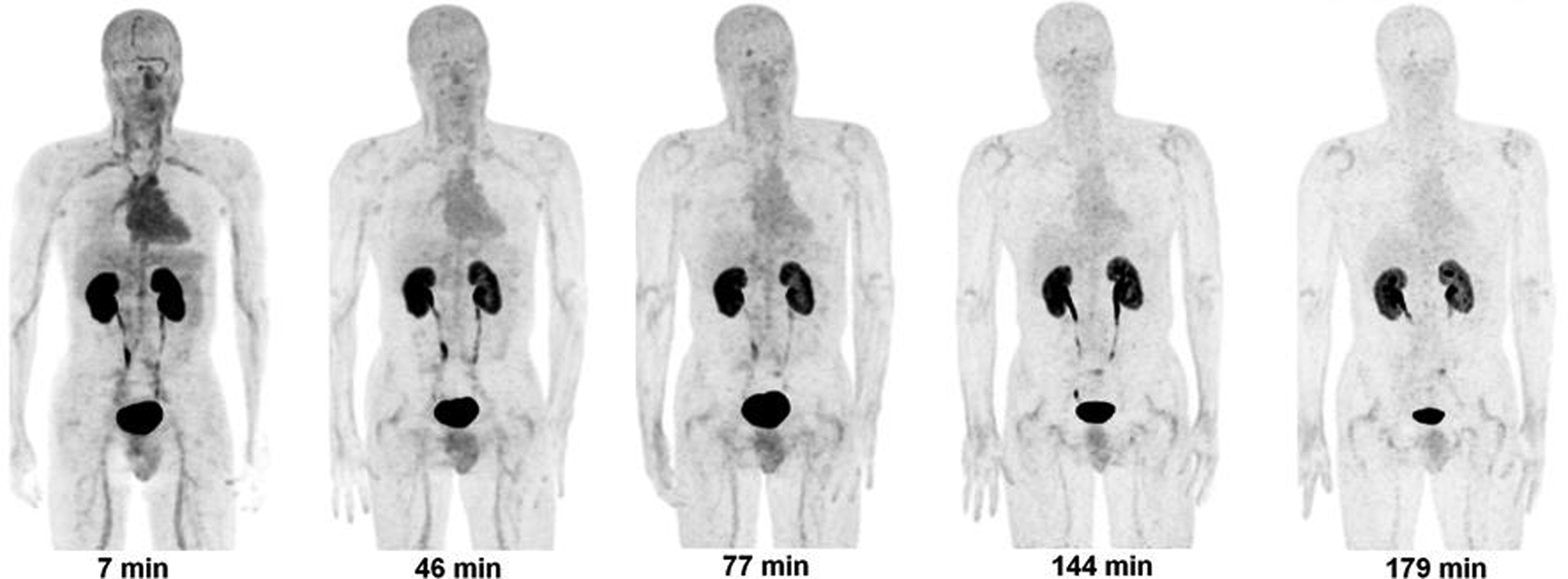

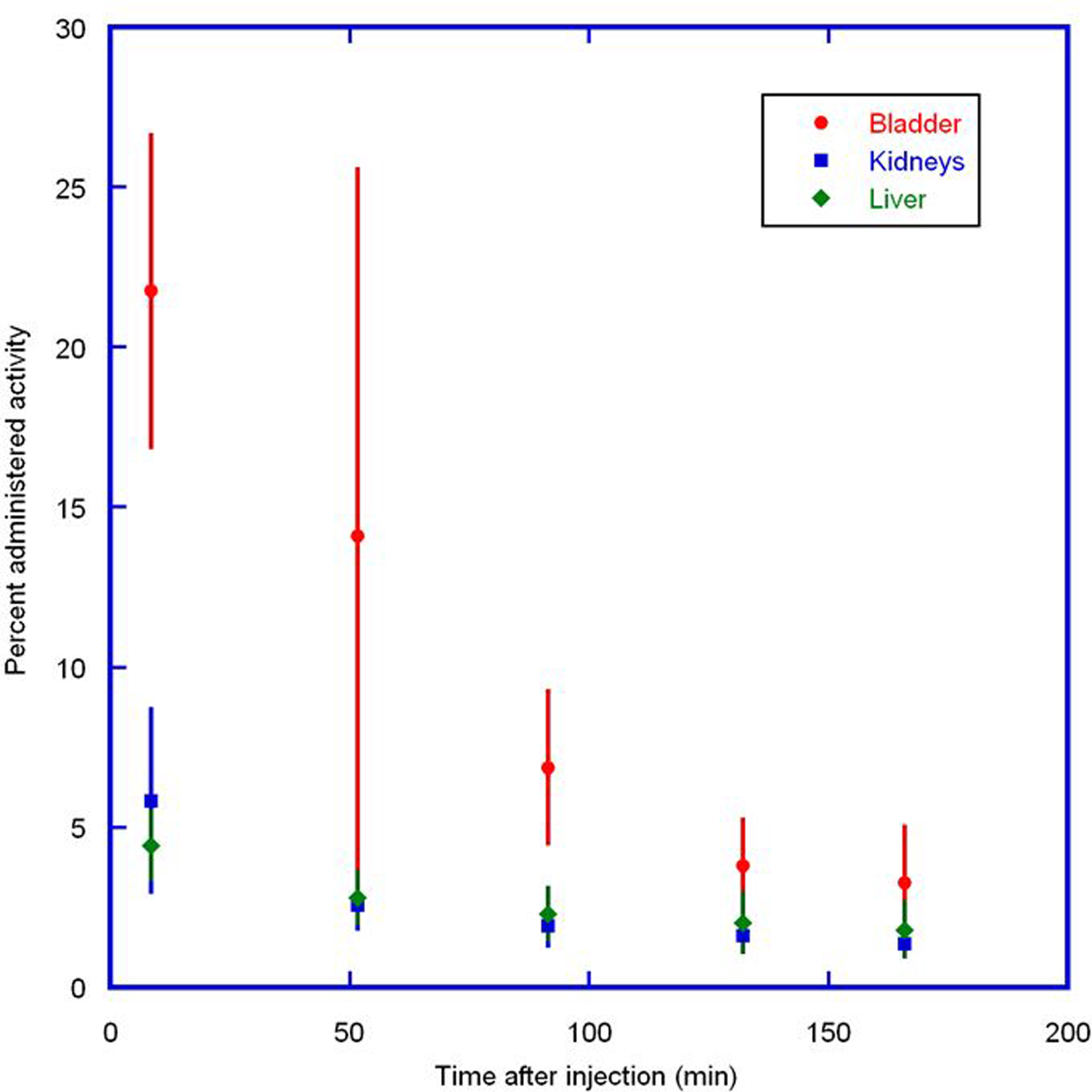

Figure 3 displays PET maximum intensity projection (MIP) images for one of the subjects from the PET scans. In the first scan, the predominant uptake was seen in both the kidneys and urinary bladder with moderate uptake observed in the liver, heart, and testes. All other organs had near background levels of activity. The mean SUVs at ~50 minutes after injection were approximately 65 in the bladder, 6 in the kidneys, and 1.5 in both the heart and liver. The rest of the body had much lower SUVs. The time-activity data for the urinary bladder, liver, and kidneys are shown in Figure 4. There was large inter-subject variation in both the bladder uptake (16% to 27%) and kidney uptake (3.5% to 11%), as indicated by the large error bars. The renal system (kidneys and bladder together) had more consistent uptake, ranging from 22% to 31%. The liver had the next highest uptake, ranging from 3.2% to 5.7%. The study radiotracer was excreted primarily via the renal system. By the end of the study (~2.8 hrs) ~77% of the injected activity of 18F-CP-18 had been excreted in the urine, as determined by assaying the urine samples in a well counter.

FIGURE 3.

Decay-corrected anterior maximum-intensity projections of PET at 7, 46, 77, 144, 179 minutes (from left to right) after injection of 18F- CP-18 in a male volunteer. There was rapid clearance of activity in all the organs.

FIGURE 4.

Mean percent administered activity and SD for bladder, kidneys, and liver determined on the basis of seven 18F-CP-18 PET emission scans in human volunteers, as a function of time after injection. Rapid clearance of activity was observed in the organs.

The normalized number of disintegrations for the organs is listed in Table 1. The mean organ doses are given in Table 2. The mean (± SD) effective dose of 18F-CP-18 for the human adult male phantom was 15±2 μSv/MBq and 38±4 μSv/MBq for the 1-hr and 4.8-hr bladder voiding interval, respectively. For a typical injected dose of 18F-CP-18 (555 MBq), the effective dose for the two intervals were 8.3±1.1 mSv and 21.1±2.2 mSv, respectively. The adult female phantom doses were 20–34% higher. The two organs with the highest radiation absorbed doses were urinary bladder wall and kidneys. For the 4.8-hr bladder voiding interval, the dose to uterus was similar to the dose to the kidneys.

TABLE 1.

Normalized number of disintegrations of source organs for volunteers injected with 18F-CP-18.

| Organ | Normalized number of disintegrations (MBq-h/MBq administered) |

|---|---|

| Breasts | 0.015±0.0047 |

| Brain | 0.0089±0.0038 |

| Heart Contents | 0.026±0.0036 |

| Kidneys | 0.059±0.017 |

| Liver | 0.064±0.024 |

| Spleen | 0.0090±0.0024 |

| Testes* | 0.0057±0.0017 |

| Urinary Bladder Wall (1.0-hr) | 0.29±0.033 |

| Urinary Bladder Wall (4.8-hr) | 1.1±0.13 |

| Remainder | 0.82±0.14 |

data from the 2 male subjects only.

Data are mean±SD; n = 7.

TABLE 2.

Estimated organ doses per unit administered activity for 18F-CP-18 for the human adult male phantom.

| Organ | 4.8-h void interval (μGy/MBq) |

1-h void interval (μGy/MBq) |

|---|---|---|

| Adrenals | 6.8±0.8 | 6.4±0.8 |

| Brain | 2.4±0.6 | 2.4±0.6 |

| Breasts | 7.7±3.6 | 7.7±3.6 |

| Gallbladder Wall | 7.6±0.8 | 6.7±0.9 |

| Heart Wall | 10±0.8 | 10±0.8 |

| Kidneys | 39±10 | 39±10 |

| Liver | 11±3.0 | 10±3.0 |

| Lower Large Intestine Wall | 20±1.3 | 8.8±0.5 |

| Lungs | 4.7±0.7 | 4.6±0.7 |

| Muscle | 8.1±0.4 | 5.3±0.6 |

| Osteogenic Cells | 7.9±0.9 | 6.8±1.0 |

| Ovaries | 19±1.1 | 8.7±0.6 |

| Pancreas | 6.9±0.8 | 6.5±0.8 |

| Red Marrow | 6.8±0.4 | 4.9±0.6 |

| Skin | 4.7±0.4 | 3.7±0.5 |

| Small Intestine | 11±0.5 | 6.8±.7 |

| Spleen | 13±2.5 | 13±2.6 |

| Stomach Wall | 6.1±0.7 | 5.5±0.8 |

| Testes* | 25±14 | 29±6.7 |

| Thymus | 4.8±0.7 | 4.8±0.7 |

| Thyroid | 4.2±0.7 | 4.2±0.7 |

| Upper Large Intestine Wall | 9.7±0.5 | 6.4±0.7 |

| Urinary Bladder Wall | 536±61 | 142±15 |

| Uterus | 38±3.2 | 14±0.6 |

| Total Body | 8.2±0.4 | 5.6±0.6 |

| Effective Dose (μSv/MBq) | 38±3.9 | 15±1.9 |

Data are mean±SD; n = 7.

data from the 2 male subjects only.

DISCUSSION

18F-CP-18, which is currently under evaluation for detecting tumor apoptosis (27), was investigated in this dosimetry study in healthy volunteers. In this investigation 18F-CP-18 was shown to have a reasonable biodistribution and dosimetry profiles in human subjects and suggests this agent may have promise in PET imaging. This study provides information on the background uptake levels in normal organs. The data also addresses the potential radiation exposure in humans through whole-body PET imaging.

18F-CP-18 displayed a biodistribution profile dominated by activity uptake in both the bladder and kidneys indicative of a rapid renal clearance. Accordingly, 77% of injected activity was excreted within 2.8 hour after injection of the tracer. The liver and heart showed diffuse uptake and there was no evidence of the tracer above background levels in the large intestines during the 2.8 hour imaging period, consistent with the notion that the tracer is cleared predominantly via the renal system. The rapid clearance and relatively low non-specific uptake of the tracer as compared to other 18F-labeled apoptosis imaging agents suggests that a large imaging window is possible for detecting increased caspase-3 expression in tumors throughout the torso, including the lungs, breast and the head and neck regions.

Among all the organs observed, the urinary bladder wall received the highest dose with the 4.8-hr bladder voiding interval as a result of the tracer’s clearance profile. The mean urinary bladder wall doses were 142±15 and 536±61 μGy/MBq for the 1-hr and 4.8-hr bladder voiding intervals, respectively. Kidneys had the next highest dose, 39±10 μGy/MBq, followed by the uterus at 38±3 μGy/MBq for the 4.8-hr bladder voiding interval. The testes had doses of 29 and 25 μGy/MBq for the two intervals, respectively. The remaining organs had lower doses, in the range of 2 to 20 μGy/MBq. The average values of effective dose for 18F-CP-18 were 15±2 μSv/MBq and 38±4 μSv/MBq, respectively, for the two intervals. For a typical 555 MBq injected dose of 18F-CP-18, the effective dose for the 4.8-hr interval is 21.1±2.2 mSv. The effective dose is lower than the 30 mSv dose limit specified by the FDA for research subjects (29). By more frequent bladder voiding the doses can be reduced. For the 1-hr bladder voiding interval, the effective dose was reduced to 8.3±1.1 mSv.

18F-CP-18 was found to be initially stable in human plasma and about 54% intact at 135 minutes post injection. The urine analysis suggests that the metabolites and parent tracer are predominantly excreted via the urine. The metabolites formed are tentatively assigned as the expected cleavage products of the parent “D-E-V-D” sequence, which were previously observed during the preclinical evaluation of the tracer in rodents (27) (data not shown). The majority of metabolite activity cleared quickly through urine via the kidneys though a small amount was detectable in plasma. The combination of the clearance and biostability profile suggests that this tracer is suitable for imaging tissue apoptosis in humans.

Table 3 compares the doses to individual organs for 18F-CP-18 with 18F-FDG for the bladder voiding interval of 4.8 h (30). The absorbed doses in the brain, heart, pancreas, lungs, spleen, thymus, thyroid, stomach wall were much lower for 18F-CP-18 than those for 18F-FDG. 18F-CP-18 did not appreciably cross the blood-brain barrier in our imaging studies. The absorbed doses in urinary bladder, kidneys, testes, and uterus were higher for 18F-CP-18 than for 18F-FDG. A large fraction of 18F-CP-18 (~77% in 2.8 hrs) was excreted through the urinary system. The urinary bladder wall dose for 18F-CP-18 (540 μGy/MBq) was much higher than that for 18F-FDG (190 μGy/MBq) (with 4-hr bladder voiding interval). However, if patients void frequently, the bladder dose is reduced to ~142 μGy/MBq using a 1-hr bladder voiding interval.

Table 3.

Organ doses for 18F-CP-18 and 18F-FDG for 4.8-h bladder voiding interval

|

18F-CP-18 (μGy/MBq) |

18F-FDG (μGy/MBq) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Adrenals | 6.8 | 13 |

| Brain | 2.4 | 19 |

| Breasts | 7.7 | 9.2 |

| Gallbladder Wall | 7.6 | 14 |

| Lower Large Intestine Wall | 20 | 17 |

| Small Intestine | 11 | 14 |

| Stomach Wall | 6.1 | 13 |

| Upper Large Intestine Wall | 10 | 13 |

| Heart Wall | 10 | 60 |

| Kidneys | 39 | 20 |

| Liver | 11 | 16 |

| Lungs | 4.7 | 17 |

| Muscle | 8.1 | 11 |

| Ovaries | 19 | 17 |

| Pancreas | 6.9 | 26 |

| Red Marrow | 6.8 | 13 |

| Osteogenic Cells | 7.9 | 12 |

| Skin | 4.7 | 8.4 |

| Spleen | 13 | 37 |

| Testes | 25 | 13 |

| Thymus | 4.8 | 12 |

| Thyroid | 4.2 | 10 |

| Urinary Bladder Wall | 540 | 190 |

| Uterus | 38 | 23 |

A successful apoptosis imaging agent will localize within apoptotic tissue with sufficient contrast between apoptotic and non-apoptotic tissues. Within normal tissues, elevated levels of caspase-3 exist for tissue maintenance, especially within cartilage and in mammary glands (31). Using these tissues as internal controls, the PET images in several subjects reveal elevated uptake of 18F-CP-18 in both shoulder cartilage and mammary glands relative to non-caspase expressing tissue (e.g. muscle), consistent with differences in caspase-3 expression levels observed across such tissues (31). As a second confirmation that 18F-CP-18 is targeting tissue apoptosis, the SPECT apoptosis imaging agent 99mTc EC Annexin V also appeared to exhibit uptake in shoulder cartilage similar to 18F-CP18, suggesting that both tracers target an overlapping pathology (32). The biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of 18F-CP-18 are likely compatible with its use as a PET apoptosis imaging agent. While the current imaging doses and scan times allowed for visualization of these caspase-expressing tissues, further imaging optimization studies will be required to determine the optimal scan time and dose levels for imaging apoptosis, or apoptotic fractions thereof, especially within tumors. From the data obtained in this study, PET imaging at 30 minutes after injection appears to be optimal, in comparison to the 60 minute delay that is typically used for other 18F-based imaging compounds such as 18F-FDG.

As a potential therapy target, apoptosis presents a unique opportunity for enabling a personalized medicine approach. For example, apoptosis imaging has the potential to identify treatment resistant tumors in need of alternate therapies by monitoring changes in 18F-CP18 uptake during the course of therapy, especially in instances where metabolic 18F-FDG PET imaging data is confounded by tissue inflammation. Given that all tumors undergo apoptosis to varying degrees, a change in apoptosis post-treatment is likely to be more meaningful than a single baseline apoptosis scan. Serial tumor uptake measurements are relatively easily performed using non-invasive PET imaging as a semi-quantitative tool which is a distinct advantage over the use of multiple biopsies.

PET apoptosis imaging may also enable the development of novel apoptosis-inducing therapies. Conventional chemotherapeutics are known to induce apoptosis, but do so non-specifically by targeting multiple cellular processes which can lead to both therapy resistance and a narrowing of the therapeutic window. Promoting apoptosis as a strategy for cancer drug discovery enables therapeutic agents to selectively induce apoptosis in cancer cells while improving therapeutic outcomes (33–36). In such a scenario, PET apoptosis imaging can be used to monitor the effect of apoptosis inducing/promoting drug treatments with the aim of predicting responders to such therapies perhaps earlier than metabolic 18F-FDG PET imaging. For such a strategy to be successful, the PET imaging data must be correlated with clinical, surgical, pathological, and patient outcomes. PET imaging of caspase-3 could therefore be established as a pharmacodynamic biomarker to measure the increase in apoptotic fraction after treatment, allowing clinicians to tailor patient treatments or optimize dosing regimens. Further studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of this promising PET imaging agent.

The injection of 18F-CP-18 did not cause clinically significant changes in vital signs or blood tests suggesting that the administration of 18F-CP-18 is both safe from a dosimetry perspective and compatible with PET imaging in humans.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Donna Mosley and Nucleae Medicine staff for their help with patient data acquisition. We thank Mary Benetz and the staff from Protocol Management Office, Clinical Research Unit and Protocol Support Laboratory for their help with the research protocol. The study was supported by Siemens Molecular Imaging Inc. The study was conducted at Fox Chase Cancer Center under the Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT01362712.

References:

- 1.Elmore S Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graeber TG, Osmanian C, Jacks T, et al. Hypoxia-mediated selection of cells with diminished apoptotic potential in solid tumours. Nature. 1996;379:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunz M, Ibrahim SM. Molecular responses to hypoxia in tumor cells. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reshef A, Shirvan A, Waterhouse RN, et al. Molecular imaging of neurovascular cell death in experimental cerebral stroke by PET. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1520–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen A, Shirvan A, Levin G, Grimberg H, Reshef A, Ziv I. From the Gla domain to a novel small-molecule detector of apoptosis. Cell Res. 2009;19:625–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoglund J, Shirvan A, Antoni G, et al. 18F-ML-10, a PET tracer for apoptosis: first human study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:720–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang F, Fang W, Zhang MR, et al. Evaluation of chemotherapy response in VX2 rabbit lung cancer with 18F-labeled C2A domain of synaptotagmin I. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grierson JR, Yagle KJ, Eary JF, et al. Production of [F-18]fluoroannexin for imaging apoptosis with PET. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toretsky J, Levenson A, Weinberg IN, Tait JF, Uren A, Mease RC. Preparation of F-18 labeled annexin V: a potential PET radiopharmaceutical for imaging cell death. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yagle KJ, Eary JF, Tait JF, et al. Evaluation of 18F-annexin V as a PET imaging agent in an animal model of apoptosis. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:658–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madar I, Ravert H, Nelkin B, et al. Characterization of membrane potential-dependent uptake of the novel PET tracer 18F-fluorobenzyl triphenylphosphonium cation. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:2057–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madar I, Huang Y, Ravert H, et al. Detection and quantification of the evolution dynamics of apoptosis using the PET voltage sensor 18F-fluorobenzyl triphenyl phosphonium. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:774–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reshef A, Shirvan A, Akselrod-Ballin A, Wall A, Ziv I. Small-molecule biomarkers for clinical PET imaging of apoptosis. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:837–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faust A, Wagner S, Law MP, et al. The nonpeptidyl caspase binding radioligand (S)-1-(4-(2-[18F]Fluoroethoxy)-benzyl)-5-[1-(2-methoxymethylpyrrolidinyl)sulfonyl ]isatin ([18F]CbR) as potential positron emission tomography-compatible apoptosis imaging agent. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;51:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith G, Glaser M, Perumal M, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological characterization of a caspase 3/7 selective isatin labeled with 2-[18F]fluoroethylazide. J Med Chem. 2008;51:8057–8067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen QD, Smith G, Glaser M, Perumal M, Arstad E, Aboagye EO. Positron emission tomography imaging of drug-induced tumor apoptosis with a caspase-3/7 specific [18F]-labeled isatin sulfonamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16375–16380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Podichetty AK, Faust A, Kopka K, et al. Fluorinated isatin derivatives. Part 1: synthesis of new N-substituted (S)-5-[1-(2-methoxymethylpyrrolidinyl)sulfonyl]isatins as potent caspase-3 and −7 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:2680–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podichetty AK, Wagner S, Schroer S, et al. Fluorinated isatin derivatives. Part 2. New N-substituted 5-pyrrolidinylsulfonyl isatins as potential tools for molecular imaging of caspases in apoptosis. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3484–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou D, Chu W, Chen D, et al. [18F]- and [11C]-labelled N-benzyl-isatin sulfonamide analogues as PET tracers for apoptosis: synthesis, radiolabeling mechanism, and in vivo imaging of apoptosis in Fas-treated mice. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:1337–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen QD, Challapalli A, Smith G, Fortt R, Aboagye EO. Imaging apoptosis with positron emission tomography: ‘bench to bedside’ development of the caspase-3/7 specific radiotracer [(18)F]ICMT-11. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou D, Chu W, Rothfuss J, et al. Synthesis, radiolabeling, and in vivo evaluation of an 18F-labeled isatin analog for imaging caspase-3 activation in apoptosis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:5041–5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niu G, Chen X. Apoptosis imaging: beyond annexin V. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1659–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talanian RV, Quinlan C, Trautz S, et al. Substrate specificities of caspase family proteases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9677–9682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh JC, Kolb HC. Applications of click chemistry in radiopharmaceutical development. Chimia. 2010;64:29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marik J, Sutcliffe JL. Click for PET: rapid preparation of [18F]fluoropeptides using CuI catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Tetrahedron Letters. 2006;47:6681–6684. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mamat C, Ramenda T, Wuest FR. Recent Applications of Click Chemistry for the Synthesis of Radiotracers for Molecular Imaging. Mini-Rev Org Chem. 2009;6:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su H, Chen G, Gangadharmath U, et al. Evaluation of [18F]-CP18 as a PET Imaging Tracer for Apoptosis. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2013:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stabin MG, Sparks RB, Crowe E. OLINDA/EXM: the second-generation personal computer software for internal dose assessment in nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1023–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA. Guidance for Industry and Researchers, The Radioactive Drug Research Committee: Human Research Without An Investigational New Drug Application. August 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM163892.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2011.

- 30.Stabin M, Stubbs J, Toohey R. Radiation dose estimates for radiopharmaceuticals, NUREG/CR-6345. April 1996. Available at: http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/nuregs/contract/cr6345/cr6345.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2011.

- 31.Krajewska M, Wang HG, Krajewski S, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of in vivo patterns of expression of CPP32 (Caspase-3), a cell death protease. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1605–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurihara H, Yang DJ, Cristofanilli M, et al. Imaging and dosimetry of 99mTc EC annexin V: preliminary clinical study targeting apoptosis in breast tumors. Appl Radiat Isot. 2008;66:1175–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer U, Schulze-Osthoff K. Apoptosis-based therapies and drug targets. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12 Suppl 1:942–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillies RJ, Verduzco D, Gatenby RA. Evolutionary dynamics of carcinogenesis and why targeted therapy does not work. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jendrossek V The intrinsic apoptosis pathways as a target in anticancer therapy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:1426–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sayers TJ. Targeting the extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathway for cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1173–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.