Highlights

-

•

Hyperinflammation in COVID-19 activates blood coagulation increasing thrombotic risk.

-

•

Tocilizumab blocks IL-6 receptor and may improve inflammatory-induced hypercoagulability.

-

•

Tocilizumab was associated with rapid and sustained coagulation improvement.

-

•

These benefits were consistent independently of thromboprophylaxis dose.

Keywords: Tocilizumab, COVID-19, Blood coagulation, Thrombosis, Prophylaxis

Abstract

Background

Many COVID-19 patients develop a hyperinflammatory response which activates blood coagulation and may contribute to the occurrence of thromboembolic complications. Blockade of interleukin-6, a key cytokine in COVID-19 pathogenesis, may improve the hypercoagulable state induced by inflammation. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of subcutaneous tocilizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor on coagulation parameters.

Methods

Hospitalized adult patients with laboratory-confirmed moderate to critical COVID-19 pneumonia and hyperinflammation, who received a single 324 mg subcutaneous dose of tocilizumab on top of standard of care were enrolled in this analysis. Coagulation parameters were measured before tocilizumab and at day 1, 3, and 7 after treatment. All patients were followed-up for 35 days after admission or until death.

Results

70 patients (mean age 60 years, interquartile range 52-75) were included. Treatment with tocilizumab was associated with a reduction in D-dimer levels (-56%; 95% confidence interval [CI], -68% to -44%), fibrinogen (-48%; 95%CI, -60% to -35%), C-reactive protein (-93%; 95%CI, -99% to -87%), prothrombin time (-4%; 95%CI,-9% to 0.8%), and activated thromboplastin time (-4%; 95%CI,-8.7% to 0.8%), and an increase in platelet count (34%; 95%CI, 23% to 45%). These changes occurred already one day after treatment with sustained reductions throughout day 7. The improvement in coagulation was consistently observed in patients receiving prophylactic or therapeutic dose anticoagulants, and was paralleled by a rapid improvement in respiratory function.

Conclusions

Subcutaneous tocilizumab was associated with significant improvement of blood coagulation parameters independently of thromboprophylaxis dose.

1. Introduction

A considerable proportion of patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) presents with a hypercoagulable state which may increase the risk of thromboembolic complications [1]. The most typical coagulation abnormalities reported in patients with COVID-19 are markedly elevated D-dimer levels, modest reductions in platelet count, and a small prolongation of the prothrombin time [1]. In severe cases, these coagulation changes may progress to disseminated intravascular coagulation, which is associated with a high mortality [2]. The average incidence of venous thromboembolic events (VTE) in COVID-19 is about 16%, and up to 35% of patients admitted to intensive care units are diagnosed with pulmonary embolism (PE) [3,4]. In addition to the systemic activation of blood coagulation, patients with COVID-19 develop inflammatory-related abnormalities of the lung microvasculature, which include widespread thrombosis with microangiopathy, intra-alveolar fibrin deposits, and alveolar capillary microthrombi [5]. Reports from autopsy studies suggested that the development of pulmonary thrombosis may contribute to the rapid respiratory deterioration and death in COVID-19 patients [5].

The excessive activation of blood coagulation may be triggered by the hyperinflammatory response and increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines which have been observed in patients with severe COVID-19 [1,6]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is one of the key mediators involved in the cytokine storm that complicates COVID-19, and IL-6 blood levels have been correlated to the severity of lung injury and mortality in these patients [7,8]. IL-6 upregulates tissue factor expression on mononuclear cells and induces thrombin generation and, therefore, it may contribute to the hypercoagulable state observed in COVID-19 patients [9]. Blockade of IL-6 activity in COVID-19 could potentially modulate the exuberant hyperinflammatory response and reduce the activation of coagulation.

Tocilizumab is a recombinant humanized anti-human IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, cytokine release syndrome, idiopathic multicentric Castleman's disease, and giant cell arteritis. Recent studies have suggested that high-hose intravenous tocilizumab may rapidly reduce fever and inflammatory markers, and improve oxygenation in severe to critical COVID-19 [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. However, data on the effects of subcutaneous tocilizumab on blood coagulation are lacking.

The aims of this study were to evaluate the effects of subcutaneous tocilizumab on blood coagulation parameters in patients hospitalized for COVID-19.

2. Materials and methods

Consecutive hospitalized adult patients with moderate to critical COVID-19 who were treated with subcutaneous tocilizumab at the Infectious Diseases Unit, Pescara General Hospital, Italy, between March 28 and April 21, 2020 were eligible. In all patients, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed by real-time reverse-transcriptase-polymerase-chain-reaction on nasopharyngeal swabs. COVID-19 disease severity was assessed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria: moderate disease was defined as clinical signs of pneumonia, but no signs of severe pneumonia, including oxygen saturation ≥ 90% on room air; severe pneumonia was defined as clinical signs of pneumonia plus one of the following: respiratory rate >30 breaths/min, severe respiratory distress, or oxygen saturation < 90% on room air; critical disease was defined as pneumonia with at least one of the following: a) acute respiratory distress syndrome; b) sepsis; or (c) septic shock [17].

Tocilizumab was administered as a single subcutaneous injection of 324 mg on top of standard of care. Patients were eligible for subcutaneous tocilizumab in case of interstitial pneumonia involving at least 20% of the lung parenchyma on chest computed tomography and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels ≥ 20 mg/dL. Both these features were associated with higher risk of disease progression in previous observational studies [18,19].

Patients were not eligible for tocilizumab treatment in case of suspected or confirmed concomitant bacterial or fungal systemic infection, active diverticulitis or gastrointestinal tract perforation, neutrophil count <0.5 × 109 cells/L, platelets count < 50 × 109/L, creatinine clearance < 30 ml/min, serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) > 5 times the upper limit of the normal range, or pregnancy.

The study was approved by the local institutional review board, and all patients provided written informed consent for the off-label use of tocilizumab.

2.1. Data collection

The following data were collected: patient characteristics (e.g. age, sex), signs and symptoms on hospital admission, past medical history, risk factors for thrombosis (e.g. cancer, prior venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular disease), routine laboratory parameters, and concomitant treatment received during hospitalization including pharmacological thromboprophylaxis (type, dose, and duration). In addition, routine clotting assays (prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time), platelet count and plasma levels of D-dimer, fibrinogen, antithrombin, and CRP, and respiratory parameters (e.g. FiO2, peripheral oxygen saturation, and the PaO2/ FiO2 ratio) were collected before tocilizumab administration and at day 1, 3, and 7 after treatment.

The primary endpoint was the change in the levels of coagulation and inflammatory parameters before tocilizumab to day 7 after treatment. Secondary endpoints included the improvement of coagulation parameters in patient subgroups defined according to the dose of thromboprophylaxis (prophylactic, intermediate, or therapeutic anticoagulation) and COVID-19 severity (moderate, severe, critical).

All patients were followed until discharge or death. All survivors who were discharged prior to day 35 after admission, were contacted at 35 days to verify patient status and development of symptomatic VTE (i.e. PE and deep vein thrombosis [DVT]). The occurrence of tocilizumab-related serious adverse events, including injection-site reactions, ALT elevation > 5 times the upper limit of the normal range, neutropenia (defined as a neutrophil count < 0.5 × 109 cells/L), and development of bacterial sepsis were recorded.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables as counts (percentage). Differences between groups were evaluated with the use of one-way analysis of variance, Wilcoxon test, Mann-Whitney U test, and the chi-squared test, as appropriate. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to verify normality and variables without normal distribution were square root transformed before the analysis. Linear mixed effects regression models were used to assess the variations in coagulation and inflammatory parameters in the repeated measures from pre-tocilizumab to day 7 after treatment. Post-hoc analysis for significance was performed through ANOVA for each model.

The variation in coagulation and inflammatory parameters was evaluated in the overall study population and in subgroups of patients defined by dose of thromboprophylaxis and disease severity. No sample-size calculation was performed. The analysis population included all patients who received tocilizumab during the study period and for whom coagulation and inflammatory data for at least 2 subsequent timepoints were available. Differences with p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using RStudio, Version 1.1.423 – © 2009-2018 RStudio, Inc.

3. Results

A total of 70 patients who received subcutaneous tocilizumab were included. Median age was 60 years (IQR 52, 75), and 29 (41%) were females. Disease severity was moderate in 11 (15.7%) patients, severe in 40 (57.1%), and critical in 19 (27.1%). Six (8.6%) patients had prior cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, 2 (2.9%) had a history of previous VTE, and 3 (4.3%) had active cancer. Fifty-nine (82.9%) patients received supplemental oxygen by nasal cannulas or mask, 28 (40%) required non-invasive mechanical ventilation, and 2 (2.9%) invasive mechanical ventilation.

Subcutaneous tocilizumab was administered after a median of 2 days (IQR 1, 5) since hospitalization and 8 days (IQR 6, 11) after symptom onset. Before admission, 4 (5.7%) patients were on anticoagulant prophylaxis with direct oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation, and 5 (7.1%) were receiving low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for VTE prevention. During hospitalization, 63 (90%) patients received thromboprophylaxis with LMWH or fondaparinux (n=61) or direct oral anticoagulants (n=2), whereas 7 (10%) patients received no thromboprophylaxis. The anticoagulant dose was prophylactic in 48 (68.6%) and therapeutic in 15 (21.4%) patients.

The main patient characteristics upon admission and concomitant treatment received during hospitalization are shown in Tables 1 and 2 .

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| N=70 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 60 (52, 75) | |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 29 (41.4) | |

| Smoker, n (%) | 9 (12.9) | |

| Any comorbidity, n (%) | 57 (81.4) | |

| Obesity, n (%) | 7 (10.0) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 38 (54.3) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 17 (24.3) | |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 6 (8.6) | |

| Respiratory disease, n (%) | 13 (18.6) | |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 3 (4.3) | |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 4 (5.7) | |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 6 (8.6) | |

| Prior venous thromboembolism, n (%) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Coagulation and inflammatory parameters, median [IQR] | Normal values | |

| Platelet count, x109/L | 219 (170, 257) | 130-400 |

| White blood cells, x109/L | 6.2 (4.8, 8.5) | 4.8-10.8 |

| PT, seconds | 12.55 (12.15, 13.67) | 9-12 |

| aPTT, seconds | 30.9 (28.80, 32.70) | 0-38 |

| D-dimer, mg/dL | 1.09 (0.63, 2.33) | 0.00-0.50 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 5.54 (4.72, 6.98) | 180-400 |

| Antithrombin III, % | 99.00 (82.00, 106.50) | 75-125 |

| C reactive protein, mg/dL | 76.3 (52.3, 138.2) | 0.0-5.0 |

| Interleukin-6, pg/mL | 43.23 (26.30, 62.32) | 5.3-7.5 |

| Pro-calcitonin, ng/mL | 0.12 (0.06, 0.19) | <0.5 |

aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; PT: Prothrombin time.

Table 2.

Treatment during hospitalization.

| N=70 | |

|---|---|

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 67 (95.7) |

| Antiviral therapy, n (%) | 22 (31.4) |

| Darunavir/Cobicistat | 20 (28.6) |

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir | 2 (2.9) |

| Systemic corticosteroids, n (%) | 47 (67.1) |

| Antibiotic therapy, n (%) | 68 (97.1) |

| Oxygen via cannulas/mask, n (%) | 59 (84.3) |

| Noninvasive ventilation, n (%) | 28 (40.0) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 2 (2.9) |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy, n (%) | 2 (2.9) |

| Anticoagulant treatment, n (%) | |

| Enoxaparin | 37 (52.9) |

| Nadroparin | 11 (15.7) |

| Fondaparinux | 13 (18.6) |

| Direct oral anticoagulant | 2 (2.9) |

| Dose anticoagulant, n (%) | |

| Prophylactic | 48 (68.6) |

| Therapeutic | 15 (21.4) |

| Antiplatelet therapy, n (%) | 5 (7.1) |

3.1. Coagulation and inflammatory parameters

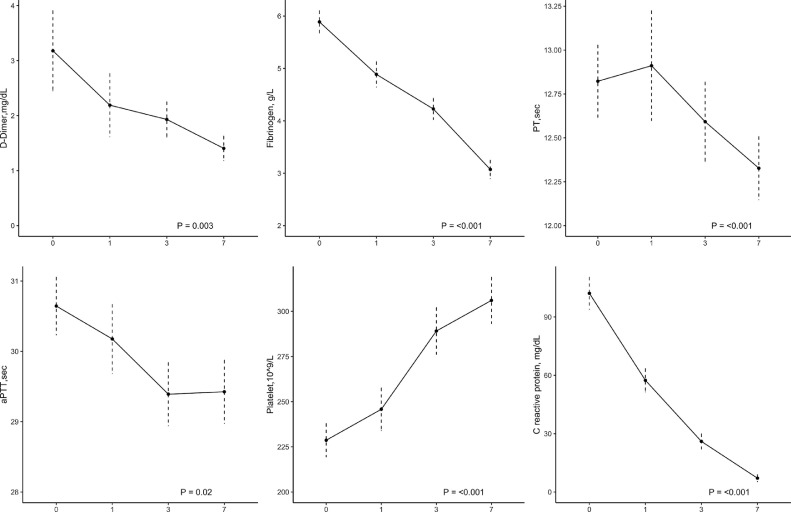

Table 1 shows the median levels of coagulation and inflammatory parameters before subcutaneous tocilizumab and the normal range for the assays. The median level of D-dimer was 1.09 mg/dL (IQR 0.63, 2.33) and of fibrinogen was 5.54 g/L (IQR 4.72, 6.98). Prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time were only mildly prolonged (12.55 seconds [IQR 12.10, 13.67] and 30.90 seconds [IQR 28.80, 32.70], respectively). After tocilizumab administration, levels of D-dimer and fibrinogen significantly decreased by -56% (95% CI, -68% to -44%) and -48% (95% CI, -60% to -35%), respectively, with sustained reductions from day 1 throughout day 7 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Following tocilizumab treatment, mean values of prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time decreased both by 4% from day 1 throughout day 7 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Median platelet count increased from 219 × 109/L (IQR 170, 257) before tocilizumab to 294 × 109/L (IQR 232, 371) at day 7 after treatment. There was no significant change in antithrombin concentrations before (99.00; IQR 82.00, 106.50) and after (93.00; IQR 82.25, 105.75) tocilizumab. The levels of CRP decreased rapidly after tocilizumab by -93% (95% CI, -99% to -87%).

Fig. 1.

Changes in coagulation and inflammatory parameters after tocilizumab treatment.

The change in D-dimer and fibrinogen levels was paralleled by an improvement in oxygenation as reflected by the rapid and progressive increase in PaO2/FiO2 ratio from 201.00 (IQR 120.25, 287.75) before tocilizumab to 289.00 (243.00, 365.00) at day 7 after treatment (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Tocilizumab improved coagulation parameters independently of thromboprophylaxis dose. Supplementary Table 2 shows the variation in coagulation parameters, CRP, and PaO2/FiO2 ratio according to the use and dose of thromboprophylaxis. In patients who received prophylactic dose anticoagulation, median D-dimer and fibrinogen were respectively 1.14 mg/dL [IQR 0.66, 3.02] and 5.52g/L [IQR 4.80, 6.63] before tocilizumab, and were reduced by -57% (95% CI, -71% to -43%) and -51% (95% CI, -66% to -36%) after treatment, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). The corresponding levels in patients on therapeutic dose anticoagulation were 1.08 mg/dL [IQR 0.54, 1.47] and 6.10 g/L [IQR 4.39, 7.96] with significant reductions at day 7 after tocilizumab (D-dimer -52% [95% CI, -78% to -26%] and fibrinogen -38% [95% CI, -65% to -12%]), respectively. Similar changes of coagulation parameters were observed in moderate, severe, and critical COVID-19 (data not shown).

3.2. Clinical outcomes

Twelve (17.1%) patients met the ISTH criteria for disseminated intravascular coagulation, which resolved 12 days after tocilizumab treatment in all but one case. No supportive or specific treatment for disseminated intravascular coagulation was provided in these cases and the dose of anticoagulation was similar to that received by patients without the coagulopathy. None of the patients developed symptomatic VTE during the study period. Nine (12.9%) patients died in hospital and 61 (87.1%) were discharged after a mean hospitalization of 16.5 days (IQR 10, 25) and none reported acute complications or bacterial infections at the 35-day phone contact visit. Tocilizumab was well-tolerated, with no related serious adverse events. Two (3.6%) patients had transient ALT elevation > 5 times the upper limit of the normal range, which decreased by day 7 after treatment. After tocilizumab, absolute neutrophil count was mildly decreased although none of the patients developed severe neutropenia. Two (2.8%) patients developed bacterial sepsis while on invasive mechanical ventilation.

4. Discussion

In this study subcutaneous tocilizumab administration was associated with a rapid and sustained improvement of coagulation and inflammation parameters in adult patients hospitalized for moderate to critical COVID-19. These changes were accompanied by an improvement in respiratory function and were consistently observed in patients receiving prophylactic or therapeutic dose anticoagulation.

In agreement with previous observations, we found that COVID-19 patients had high D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, mild thrombocytopenia, and slight prolongation of prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time at hospital admission [1,2]. Treatment with subcutaneous tocilizumab improved all these coagulation parameters typical of COVID-19 with effects that were maintained at day 7. In addition, improved coagulation activity with resolution of the coagulopathy was observed within 12 days from tocilizumab in 11 of 12 patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation. We included eleven patients with moderate COVID-19 who were at risk of disease progression based on extensive lung involvement and high CRP levels [18,19]. These patients had similar coagulation abnormalities as severe COVID-19 patients and experienced similar improvement of the coagulation activity following tocilizumab, which suggests that rapid inflammatory control could be valuable to prevent disease progression. Due to the lack of a control group, we cannot exclude that the improvement of coagulation parameters followed the natural course of these milder forms of the disease. Previous studies reported substantial clinical improvement in patients with severe COVID-19 receiving high-dose intravenous tocilizumab, however, results remain conflicting with some reports showing no significant change [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16],[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]]. Consistently with our findings, two of these studies found a significant reduction in D-dimer levels [12,13]. In contrast, a cohort of critical COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, showed no significant effects on D-Dimer levels despite the substantial improvement in inflammatory activity [10]. Taken together, these data seem to suggest that the effects of tocilizumab on coagulation may be attenuated in advanced stages of the disease.

In line with previous reports, subcutaneous tocilizumab was associated with a rapid and marked reduction in CRP levels [10,12,13]. IL-6 may play a dominant role in the systemic hyperinflammatory response secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and contribute to the hypercoagulable state observed in COVID-19 patients [8]. Therefore, blockade of IL-6 activity in COVID-19 might have beneficial effects on both coagulation and inflammatory activity [1]. The combination of systemic hyperinflammatory response, excessive activation of the coagulation system, and pulmonary thrombo-inflammation with local vascular damage caused by COVID-19 may increase the risk of VTE and pulmonary artery thrombosis. In the current study, there were no cases of symptomatic VTE and it may be speculated that subcutaneous tocilizumab attenuated the inflammatory and coagulation activity both systemically and at the level of the lung microvasculature, reducing the risk of thrombosis.

Previous studies evaluating intravenous tocilizumab lacked information about concomitant anticoagulant therapy, which may have confounded the association with the coagulation changes [10,12,13]. In the present study, the effects of subcutaneous tocilizumab on coagulation parameters were observed independently of thromboprophylaxis dose. D-dimer and fibrinogen levels were more than halved both in patients on prophylactic and therapeutic dose anticoagulation. The clinical relevance of these findings requires further evaluation. Several studies showed that VTE develops in COVID-19 patients despite higher than prophylactic doses of anticoagulant, suggesting overwhelming inflammatory and blood coagulation activity. The efficacy and safety of higher-dose thromboprophylaxis is currently being investigated in several randomized trials (NCT04366960, NCT04372589, NCT04345848, NCT04367831). IL-6 receptor blockade with tocilizumab in addition to thromboprophylaxis may provide an alternative option to control coagulation activation.

The current study has some limitations. We included a relatively small number of patients in whom subcutaneous tocilizumab appeared well-tolerated with no serious or clinically relevant adverse events. While these data seem reassuring, larger studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy profile of tocilizumab. Previous and current findings suggest that critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation may have a higher risk of serious infections with tocilizumab which warrants further investigation [20,21]. Patients were admitted to general wards and the proportion of those with critical disease was relatively small, therefore conclusions may not apply to patients admitted to intensive care units receiving intravenous tocilizumab. The lack of a randomized control group may have confounded the effects observed. However, the close temporal association between tocilizumab administration and change of coagulation parameters both in the overall study population and in the subgroups of patients receiving prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation seems to support our findings. The identification of the best patient candidate and timing for tocilizumab administration require further evaluation.

In conclusion, treatment with subcutaneous tocilizumab was associated with a rapid and persistent improvement of coagulation activity in hospitalized adult patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and hyperinflammation. If confirmed in other large studies, our findings may further support IL-6 receptor blockade with subcutaneous tocilizumab as promising therapeutic strategy to quench the hyperinflammatory response secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection and modulate the hypercoagulative state observed in COVID-19 patients.

Authors' contribution

Study conception and design: Di Nisio M, Potere N, Porreca E. Data acquisition: Potere N, Spacone A, Pieramati L, Ferrandu G, Rizzo G, La Vella M, Di Carlo S, Cibelli D. Statistical analysis: M. Candeloro. Interpretation of the data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: All authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Final approval of the manuscript: All authors.

Funding

There was no funding source for this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

M. Di Nisio reports personal fees from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Pfizer, Leo Pharma, and Aspen outside the submitted work. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply in debt with all our colleagues, both Physicians and Nurses, who accepted to contribute to a single functional Unit of Treatment for COVID 19 patients throughout the Pescara General Hospital, thus allowing homogeneous implementation of Tocilizumab prescription whenever needed in accordance with inclusion and exclusion criteria. In particular, we are in debt with Drs A. Pieri, R. Scurti, F. Di Stefano, F. Di Masi, F. Colameco, S. Di Carlo, G. Di Battista, and A. Trovato.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2020.10.020.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Levi M., Thachil J., Iba T., Levy J.H. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e438–e440. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potere N., Valeriani E., Candeloro M., Tana M., Porreca E., Abbate A. Acute complications and mortality in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24:389. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03022-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klok F.A., Kruip M., van der Meer N.J.M., Arbous M.S., Gommers D., Kant K.M. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M., Haverich A., Welte T., Laenger F. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aziz M., Fatima R., Assaly R. Elevated interleukin‐6 and severe COVID‐19: a meta‐analysis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25948. jmv.25948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levi M., van der Poll T., Büller H.R. Bidirectional relation between inflammation and coagulation. Circulation. 2004;109:2698–2704. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131660.51520.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toniati P., Piva S., Cattalini M., Garrafa E., Regola F., Castelli F. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: a single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klopfenstein T., Zayet S., Lohse A., Balblanc J.-C., Badie J., Royer P.-Y. Tocilizumab therapy reduced intensive care unit admissions and/or mortality in COVID-19 patients. Méd Mal Infect. 2020;50:397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sciascia, S., Aprà, F., Baffa, A., Baldovino, S., Boaro, D., Boero, R., et al. Pilot prospective open, single-arm multicentre study on off-label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19. Clin Exp Rheumatol n.d.;38:529–32. [PubMed]

- 13.Xu X., Han M., Li T., Sun W., Wang D., Fu B. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:10970–10975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo P., Liu Y., Qiu L., Liu X., Liu D., Li J. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID‐19: a single center experience. J Med Virol. 2020;92:814–818. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capra R., de Rossi N., Mattioli F., Romanelli G., Scarpazza C., Sormani M.P. Impact of low dose tocilizumab on mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 related pneumonia. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campochiaro C., Della-Torre E., Cavalli G., de Luca G., Ripa M., Boffini N. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in severe COVID-19 patients: a single-centre retrospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization 2020. Clinical management of COVID-19 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19. [PubMed]

- 18.Yang Y., Shen C., Li J., Yuan J., Wei J., Huang F. Plasma IP-10 and MCP-3 levels are highly associated with disease severity and predict the progression of COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:119–127.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J., Qi T., Liu L., Ling Y., Qian Z., Li T. Clinical progression of patients with COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. J Infect. 2020;80:e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morena V., Milazzo L., Oreni L., Bestetti G., Fossali T., Bassoli C. Off-label use of tocilizumab for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Milan, Italy. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Somers E.C., Eschenauer G.A., Troost J.P., Golob J.L., Gandhi T.N., Wang L. Tocilizumab for treatment of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quartuccio L., Sonaglia A., McGonagle D., Fabris M., Peghin M., Pecori D. Profiling COVID-19 pneumonia progressing into the cytokine storm syndrome: results from a single Italian Centre study on tocilizumab versus standard of care. J Clin Virol. 2020;129 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colaneri M., Bogliolo L., Valsecchi P., Sacchi P., Zuccaro V., Brandolino F. Tocilizumab for treatment of severe COVID-19 patients: preliminary results from SMAtteo COvid19 REgistry (SMACORE) Microorganisms. 2020;8:695. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8050695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guaraldi G., Meschiari M., Cozzi-Lepri A., Milic J., Tonelli R., Menozzi M. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e474–e484. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biran N., Ip A., Ahn J., Go R.C., Wang S., Mathura S. Tocilizumab among patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao J., Cui W., Tian B. Efficacy of tocilizumab treatment in severely ill COVID-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020;24:524. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03224-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.