Abstract

The literature on China’s social media foreign propaganda mostly focuses on text-format contents in English, which may miss the real target and the tool for analysis. In this article, we traced 1256 Twitter accounts echoing China government’s #USAVirus propaganda before and after Twitter removed state-linked operations on June 12, 2020. The 3567 tweets with #USAVirus we collected, albeit many written in English, 74% of them attached with a lengthy simplified Chinese text-image. Distribution of the post-creation time fits the working-hour in China. Overall, 475 (37.8%) accounts we traced were later suspended after Twitter’s disclosure. Our dataset enables us to analyze why and why not Twitter suspends certain accounts. We apply the decision tree, random forest, and logit regression to explain the suspensions. All models suggest that the inclusion of a text-image is the most important predictor. The importance outweighs the number of followers, engagement, and the text content of the tweet. The prevalence of simplified Chinese text-images in the #USAVirus trend and their impact on Twitter account suspensions both evidence the importance of text-image in the study of state-led propaganda. Our result suggests the necessity of extracting and analyzing the content in the attached text-image.

Keywords: COVID-19, Usavirus, China politics, US–China relationship, Propaganda

Introduction

On February 22, 2020, Chinese official media Global Times publicly suggested that the COVID-19 virus might originate in the USA. On March 12, 2020, this conspiracy theory was endorsed and tweeted by Zhao Lijian, the spokesman and deputy director-general of the Information Department of China’s Foreign Ministry [8]. Meanwhile, a recent study finds evidence linking tweet bots to a Beijing-based market company, which has contracted with the Chinese government to “deliver to the world the correct voice of China” amid the pandemic [14].

One month after Zhao’s tweet, a sudden wave of #USAVirus started to spread on Twitter. This hashtag drew our special attention for three reasons. First, the hashtag directly echoes Zhao’s conspiracy theory, alluding the possibility of coordination. Second, #USAVirus is literally a direct accusation to a clear target—United State. Compared with other forms of propaganda, who would gain or loss by this hashtag is relatively clear. Third, many #USAVirus tweets were listed in Twitter's removal archive on June 12, which included Chinese-related information operations.

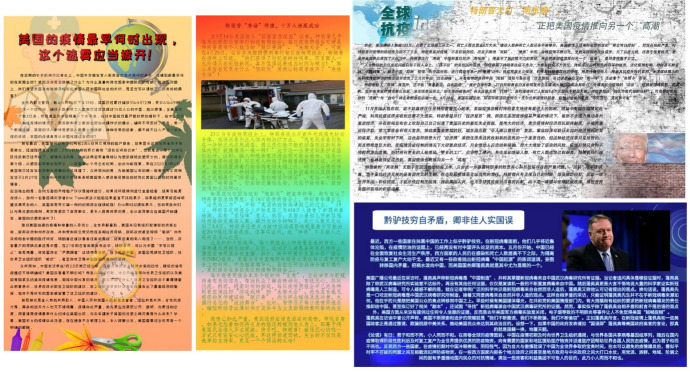

Upon further investigation, we noticed that these #USAVirus tweets shared similar features and used the same information tactic: in addition to the hashtag and English tweet text, many of these tweets came along with a text-image that was composed of a lengthy essay in simplified Chinese and a few images (see Fig. 1). The messages of English tweets were sometimes discordant with the messages in the text-images. We also noticed that these accounts have identical behavior patterns: few followers and followings, low engagement, and a suspicious profile (usually a teen’s headshot or a manga character). Take Fig. 1 for example, created in March 2020, this account had zero followers and followed nine others until May 13. It used an African girl’s photograph as its profile, commented in English, but the image was written in Chinese only. Given the few followers, it was unusual that this text-image has been shared 33 times with 34 likes. Twitter later suspended this account on June 12. Other examples of Chinese text-images are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

An example of a simplified Chinese text-image attached in a #USAVrius tweet and posted by a non-Chinese account

Source: https://twitter.com/AliceCo07986953/status/1258235131115921408. (Accessed 13 May 2020)

Fig. 2.

Examples of simplified Chinese text-images attached in #USAVirus tweets. (Accessed 13 May 2020)

In the public archive released by Twitter,1 state-linked accounts started to tweet with #USAVirus from April 10. The propaganda continued till April 17, the last day of record in this released archive. We kept monitoring this trend and found that 1256 accounts made 3567 tweets with #USAVirus from April 29 to May 9. After another month, on June 12, 2020, Twitter announced to remove coordinated operations linking to China, Russia, and Turkey.2 Among them, 23,750 core accounts and 150,000 amplifier accounts were identified to be linked to the Chinese government and were suspended. Their activities recorded in the archive took place between January 11, 2018, and April 17, 2020. 3 Among the 1256 accounts we traced, 475 (37.8%) were suspended amid the mass suspensions.

This unique opportunity and issue setting enable us to investigate two questions. First, who were the target of this #USAVirus propaganda? Second, among all #USAVirus accounts, why were some suspended by Twitter but not the others? In this study, we compare our dataset with Twitter’s removal archive and look into the accounts, tweets, and other related metadata such as posting time in order to map this coordinated information operation and understand the intention behind this attack.

In this article, we reveal that text-image is the key to help answer both questions. Text-image is a unique digital media type composed of text and images. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate examples of simplified Chinese text-images used in USAVirus tweets. This type of text-image allows Twitter users to disseminate more information that cannot be provided in the limited space of a tweet while also helps them circumvent Twitter’s automatic content moderation Although these tweets did not become trendy before many of them were taken down by Twitter as “state-linked information operations” on June 12, 2020, they did display an emerging propaganda tactic. We argue that the operation of #USAVirus was an experiment on text-images as a new propaganda tool initiated by Chinese-related cyber armies. The prevalence of simplified Chinese text-images also suggested that the goal of #USAVirus tweets was primarily to influence overseas Chinese and the circumventors of the Chinese Great Firewall instead of US public opinion.

As the COVID-19 virus is sweeping the world, another destructive pandemic is also going viral. The World Health Organization warned in February 2020 that the COVID-19 outbreak “has been accompanied by a massive ‘infodemic.’” Infodemic is a term used to “outline the perils of misinformation phenomena during the management of virus outbreaks” Cinelli et al. [7. Scholars (e.g., [3, 4, 11]) have warned that infodemic can be as dangerous as the virus since the over-abundance of misleading information has posed great challenges to the global fight against the COVID-19 disease. In addition to pseudoscience and unverified folk remedies, network propaganda initiated by vicious manipulators that targeted at specific populations is also rampant. Benkler et al. [2] define “network propaganda” as “the ways in which the architecture of a media ecosystem makes it more or less susceptible to disseminating these kinds of manipulations and lies.” In a time of pandemic, not only the media ecosystem provides the soil for network propaganda, the quarantine isolation and stress also precipitate the spread of misinformation (false information that is spread regardless of intention) and disinformation (false information that is spread intentionally to confuse or mislead). It is during this infodemic that new propaganda tactics find opportunity to test and to grow. Our research adds onto the study of disinformation and network propaganda. By highlighting the emerging tactic of text-images, we hope to contribute to the understanding of the rapidly developing tactics of network propaganda on social platforms.

Research question

First, (H1) we hypothesize that Chinese users, mainly overseas Chinese and China’s Great Firewall climbers, were the targets of this #USAVirus propaganda.

Recent investigative reportings and researches [7, 14, 17] have suggested that the Chinese government attempted to influence international narratives on the COVID-19 pandemic. In the context of the US–China information war [5], some believe that the information operations by the Chinese government targeted at US citizens to “shift the public opinion.” If it was the case, we should observe that the conspiracy theory was written in English so that an ordinary US citizen can quickly consume and help spread the propaganda. For example, the spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s tweet questioning the origin of COVID19 on March 12 was written in English, which has been retweeted 3500 times. Meanwhile, in the same tweet, the video Zhao shared 4 was subtitled with simplified Chinese only. If China hoped to shift the public opinion in the US or the international society on the narrative of the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese-subtitled video was not the most efficient strategy—unless it was not the main goal.

The other possible target was Chinese users on Twitter, mainly overseas Chinese and the Great Firewall climbers. In the history of contemporary China since the nineteenth century, overseas Chinese always posed huge threats to the ruling authority. Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China, could not push forward his revolutionary attempts without tremendous donations from overseas Chinese in Japan, Europe, and the US. In today’s Communist China, domestic discontent is controlled by censorship and selective repression [19]. Nevertheless, as the number of overseas Chinese grows rapidly, network propaganda becomes an important strategy by the Chinese government to influence its overseas population.

We argue that Twitter can serve as a platform for network propaganda especially for those who do not use WeChat, the main social media platform used in China. Overseas Chinese dissents usually use Twitter to empower democratic movements and seek international connections. Domestic Chinese people also tend to use Twitter for banned information. When Instagram was blocked on September 29, 2014, the number of new Twitter accounts created in China jumped 600% on the same day. These new accounts are more likely to talk about censored news and keywords in China [12]. As the number of overseas Chinese grows rapidly, network propaganda becomes an important tactic by the Chinese government to influence its overseas population. We argued that #USAVirus tweets served to safeguard the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) ruling by influencing online narratives and pacifying dissenting voices beyond its power of censorship amid COVID-19 turmoil.

The frequency of simplified Chinese text-images in #USAVirus tweets can serve to distinguish who were the main target of this attack. If the majority of #USAVirus tweets included such a simplified Chinese text-image, it was much more likely that the propaganda targeted Chinese users than English users, that is, overseas Chinese and the Great Firewall climbers. Instead, if the majority of posts and text-images were written in English, they were more likely to target US citizens.

Second, (H2) we hypothesize that text-image is an emerging coordinated propaganda tactic of Chinese-led operations on social media platforms.

Twitter’s decision of state-led account suspensions provided us an opportunity to investigate this hypothesis. In Twitter’s official announcement, it mentioned that the suspended accounts usually have a low number of followers and a low level of engagement. Meanwhile, they were “spreading geopolitical narratives favorable to the Communist Party of China.” Twitter’s official announcement did not specify in what way Chinese favorable narratives were spread. We want to examine if text-image was one of the key elements in coordinated operations identified by Twitter.

Image is easier to catch users’ attention on social media, and it provides a free and less-regulated space for state-led accounts to spread favorable narratives on social platforms. A recent study of WhatsApp in India also shows that image is an important medium to spread misinformation [9]. As shown in Fig. 1, a text-image can convey a stronger and richer message in a single post than a limited post comment on Twitter. We hence believe that image is an important arena of information operations.

Among the #USAVirus accounts we traced, only one-third of them were suspended by Twitter on June 12. This suggests that Twitter did not rely merely on hashtags to determine state-linked accounts. For Twitter, using keywords and hashtags to identify coordinated operations is far from sufficiency. Even though a coordinated operation may use certain hashtags and keywords to make them “trending,” others can appropriate the same hashtags for different purposes, thus weakening the influence power of the hashtags. So what are the other determinants that Twitter has considered when it suspended certain accounts than others? Did text-image play a role in the suspensions? By comparing our dataset with Twitter’s removal archive, we will show that text-image is one of the key features of Chinese-led coordinated operations identified by Twitter.

Data and method

We used the online service TAGS,5 which is designed specifically to crawl all tweets with a given hashtag. The main drawback of this service is that it can only crawl tweets in the most recent seven days. Hence, we completed the crawling from May 5 to 7 and collected all 3567 #USAVirus tweets posted between April 29 and May 7. Our dataset generated by TAGS includes the account id, content of the tweet, time of creation (in the Coordinated Universal Time, UTC), the number of followers and followings of the account, and the URL of each tweet.

Simplified Chinese text-images

As is shown in Fig. 1, the main content in the attached text-image can be very different from tweet comments. They use different languages and often convey distinct messages. Compared with the 140-word limit of each tweet, a text-image has no word limit and has more space to deliver messages. We manually revisited all tweets on May 9 and coded whether each tweet included an image, video, or external link. Overall, 3383 (94.8%) tweets included more than text comments. We used the narrowest standard to code whether the text-image or the subtitle of the video was written in simplified Chinese or not. Figure 3 shows four other examples of #USAVirus tweets in our dataset. The upper left picture is the only one of the four examples which is coded by us as a simplified Chinese text-image. Even though the tweet is mostly written in English, the content in the attached text-image is written in simplified Chinese. This picture also exemplifies how the Chinese text-image can tell a different story from the English tweet. On the one hand, the English tweet is about the US inadequate preparation of the COVID-19 pandemic. The simplified Chinese text-image, on the other hand, accuses that the USA lied about when the COVID-19 broke out in the US, implying the virus might originate in the US instead of China. In this case, it is the message of the text-image that echoes #USAVirus, not the English tweet.

Fig. 3.

Four #USAVirus examples in the dataset. Only the upper left is coded as Chinese text-image

The other three examples in Fig. 3 are not coded as a simplified Chinese text-image. The upper right is a Lego video made by Chinese to mock America’s slow response to the COVID-19.6 Even though the header “Xinhua News Agency” indicates that it might be made by a Chinese news outlet, it does not have a Chinese subtitle, so it is coded non-Chinese content. Both the lower left picture and lower right picture do not include any Chinese character, so they are coded as non-Chinese content (even though the tweet text of the lower left picture is written in Chinese).

To investigate H1, we manually coded all 3567 #USAVirus tweets and examined how many of them were attached with a simplified Chinese text-image. If the majority of them did, then we will have a higher level of confidence that the #USAVirus tweets targeted at Chinese users than English users.

Account suspensions after June 12, 2020

On June 24, we revisited all 1256 accounts with the #USAVirus posts after Twitter announced its mass suspensions on accounts related to state-link information operations. A total of 475 (37.8%) accounts in our dataset were suspended. We compared and analyzed the suspended accounts with others in our dataset. An account is the unit of analysis. The dependent variable is whether the account was suspended or not (binary coded). We include six independent variables and the basic descriptive analyses in Table 1.7

Table 1.

Variables used in explaining account suspensions (n = 1256)

| Variable name | Definition | Descriptives |

|---|---|---|

| chinese_textimage | The % of tweets that the account posted include a Chinese text-image. It calculates from the number of tweets including the Chinese text-image divided by the number of all tweets from individual account |

Min: 0 Max: 1 Mean: 0.515 Median: 1 |

| chinese_text | The % of tweets that the account posted include a Chinese character in the text |

Min: 0 Max: 1 Mean: 0.448 Median: 0 |

| N_friend | The number of accounts that the account follows |

Min: 0 Max: 51,734 Mean: 839 Median: 89 |

| N_follower | The number of followers that the account has |

Min: 0 Max: 278,296 Mean: 1192.7 Median: 21 |

| N_RT | The % of tweets that the account posted are from the retweet of others’ posts |

Min: 0 Max: 1 Mean: 0.68 Median: 1 |

| N_post | The number of #USAVirus posts that the account made |

Min: 1 Max: 43 Mean: 2.84 Median: 1 |

To estimate the impact of simplified Chinese text-images on account suspensions and falsify H2, we apply decision tree, random forest, and logit regression model to approach to the process of account suspensions. If simplified Chinese text-images significantly help explain the suspensions across the three models, we will have a higher level of confidence that these text-images play a key role both in China's network propaganda and Twitter's account suspensions.

Result

Prevalence of simplified Chinese text-images—73.7%

In all 3567 #USAVirus tweets we recorded from April 29 to May 7, 2629 (73.7%) include a simplified Chinese text-image, and 2414 (67.7%) also contain Chinese hashtags in the tweet comment, such as #共抗肺炎(fighting Covid-19 together), #新冠肺炎 (Covid-19), #美国疫情 (Covid-19 in the USA). Only 605 of them (16.9%) do not use any Chinese character in the comment or the image.

These Chinese text-images are all composed of a huge title, a lengthy essay, and a few images. In these lengthy, dense texts, several themes appear repeatedly: (1) the Chinese government shows great leadership in guiding its people to defeat the virus. (2) The Trump administration irresponsibly attributes the pandemic to China for his reelection. (3) The Trump administration conceals when the pandemic really broke out in the US. (4) The great powers should cooperate in fighting against COVID-19. (5) Patients in China received full and free treatments and recovered soon. These narratives delivered two messages: China successfully defeated the virus, while the US government failed to protect its people. These messages corresponded with Chinese officials’ public speech during the pandemic.

We also noticed that an essay is often reworked with different pictures and backgrounds to produce new text-images. In some of them, the text was superimposed on a photo of Donald Trump or Mike Pompeo. In some others, Chinese characters were distorted like a wave. These designs increased the complexity of automatic content moderation as they required advanced visual text recognition in order to distract the text. Even if Twitter tries to take them down, these texts can be quickly reproduced with new pictures and backgrounds.

The prevalence of Chinese text-images and hashtags suggests that these tweets target at Chinese users—oversea Chinese and the Great Firewall climbers—instead of average US citizens. The English hashtag #USAVirus might be simply a hook to lure those Chinese who are curious about how people discuss the origin of the virus on Twitter. Through disseminating these text-images along with #USAVirus, this information operation helps spread Chinese-favorable narratives beyond the Great Firewall.

Posting time showed a coordinated operation

One may question the external validity of these 3567 #USAVirus tweets. It is possible that these tweets and text-images were made by random users who can read simplified Chinese and have nothing to do with Chinese coordinated propaganda. To verify #USAVirus as a coordinated operation, we look into its posting time to offer evidence that strengthens the validity of our #USAVirus dataset.

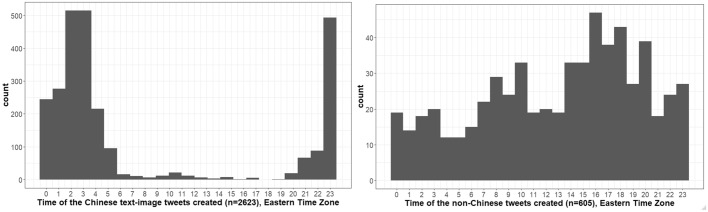

Among 2629 #USAVirus tweets with a Chinese text-image, 86% of them were tweeted between 11 pm and 4 am at Eastern Time Zone (UTC-05:00, equivalent to 11 am–4 pm at Chinese Standard Time, UTC + 08:00) as is shown in the left column of Fig. 4.8 The time that non-Chinese #USAVirus tweets created is shown on the right, with most posts between 2 and 8 pm at Eastern Time Zone (equivalent to 2 am to 8 am at Chinese Standard Time). According to Mao et al. [16]’s analysis of 700 million posts on Sina Weibo (a Chinese version of Twitter), daily posts on Weibo distributed evenly from 8 am to 11 pm in China, with the peak at around 10 pm. The distribution of #USAVirus posting time differs greatly from Mao’s study and it cannot be explained by the behavior pattern of ordinary Chinese or US users.

Fig. 4.

Time of tweets with Chinese text-images and non-Chinese tweets created, Eastern Time Zone (UTC-05:00)

In Mao et al.’s work, they also categorize three types of Weibo users. The first two groups tend to use Weibo after 5 pm—off-hours—but the third cluster tends to post at 11 am and then from 2 to 4 pm. This 12–2 pm lunchtime gap suggests that “they use the Weibo during work.” A similar time distribution is also revealed in Palmer’s [18] analysis of Chinese bots’ activities on Twitter. King et al. [15]’s research on the 50c party (online commentators hired by the Chinese government) also found that most of the Internet commentators are existing government employees who rarely work after 5 pm local time.

We further noticed that the post creation time of these simplified Chinese text-images displays a similar distribution to the public archive released by Twitter. Figure 5 compares the post creation time of #USAVirus tweets with simplified Chinese text-images and Twitter’s removal achieve on Chinese Standard Time. It clearly shows a similar 8 am–5 pm posting pattern with a 2-hour lunch break. Based on above analysis, we infer that these #USAVirus accounts are not random users. They are mostly likely to be paid cyber armies or even government employees who tweeted #USAVirus with Chinese text-images for work.

Fig. 5.

Time of simplified Chinese text-images in #USAVirus tweets (n = 2632) and all identified coordinated propaganda in Twitter’s public archive (n = 348,608), Chinese Standard Time (UTC + 08:00)

Low lever of engagement of the #USAVirus accounts

Another evidence related to the external validity of our dataset is the level of engagement of the #USAVirus accounts. The median number of followers of all 3567 #USAVirus posts is 21, which means that 50% of these posts have 21 or fewer followers.

Owing to the data limitation, we failed to record whether they followed each other or not, so we only used retweets as the indicator. We noticed that the majority of these #USAVirus promoting accounts rarely interact with other users on Twitter. There were only 52 retweets between the two accounts we traced. Other accounts did not interact with each other at all. Most of these accounts were not core leaders. They tended to retweet the posts of @realDonaldTrump, @CNN, @CNNPolitics, @VOAChinese, @washingtonpost, and @latimes, and left a comment with #USAVirus. This suggests that their only task for logging into Twitter was to spread state propaganda.9

To sum up, these #USAVirus tweets with a simplified Chinese text-image in our dataset were posted in a similar pattern with both Twitter’s official archive and the working-hour activities in Weibo. Moreover, the #USAVirus hashtags were also found in Twitter’s archive. Therefore, we have a higher level of confidence that our #USAVirus dataset at least captured some coordinated state-led propaganda as in the Twitter’s archive, and the prevalence of simplified Chinese text-images can be seen as a tool applied in this state-led propaganda. Since the text-images appeared in almost all the tweets and were written in simplified Chinese, the state-led propaganda was more likely to target overseas Chinese than US citizens.

Text-Image explains account suspension

On June 12, 2020, Twitter announced a suspension of 23,750 accounts linked to Chinese state-led information operations. According to Twitter’s official announcement, these accounts “typically holding low follower accounts and low engagement.” In our dataset, however, only 475 among the 1256 accounts we traced were suspended. All of our traced accounts posted #USAVirus echoing CCP’s propaganda during the same time frame before, but Twitter suspended only one-third (37.8%). Why?

Indeed, not all #USAVirus posts are linked to state-led propaganda. In our datasets, some #USAVirus posts were made by Cubans complaining about how the pandemic in the USA influenced Cuba. Our earlier analysis showed the simplified Chinese text-image was a key tool used in the coordinated propaganda of #USAVirus. We thus wonder if Twitter also relies on text-image as one key factor in account suspensions. We applied decision tree mode, random forest model, and logit regression to examine the importance of text-image in account suspensions.

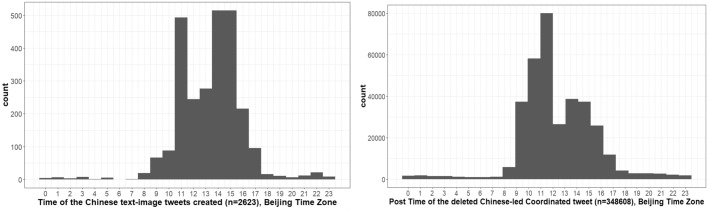

First, the decision tree model suggests that the inclusion of a simplified Chinese text-image is the most important variable to explain the decision of suspension. The result of the decision tree model is shown in Fig. 6. This simple model in Fig. 6 successfully explains 84.7% of cases. Besides, the average correction rate of the tenfold cross-validation reaches the maximum 84.6% when the number of splits is the same as in Fig. 6. The complexity analysis also suggests 3 as the optimal split to minimize cross-validation error. In this optimized tree, whether the accounts posted simplified Chinese text-images (% of chinese_textimage post > 0.029) plays the most important role in explaining the suspensions. Without a Chinese text-image, an account that tweets #USAVirus has only 5% of chance to be suspended. Among the accounts who tweet with Chinese text-images and follow fewer than 66 (N_friend < 66), the account has 78% chance to be suspended.

Fig. 6.

Decision tree model explaining suspensions among #USAVirus accounts (n = 1256)

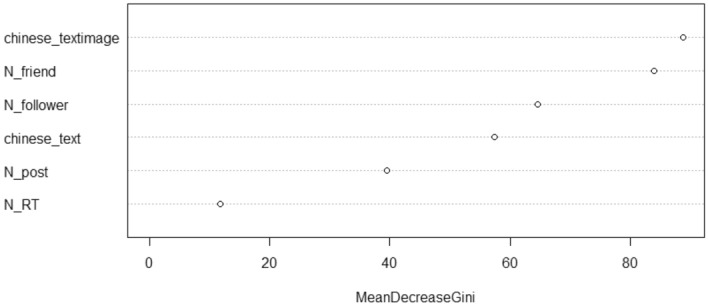

Second, we applied the random forest model to explain the decision of suspension. We randomly assigned the datasets into the training set (942 accounts, 75%) and testing set (315 accounts, 25%). The random forest model is then trained by the training set with 500 trees and 2 variables at each split. The overall out-of-bag error rate is 15.29%. We then use the testing set to the trained random forest model and compare the predictions with the real value. The random forest model successfully predicts the non-suspension (171, 54.2% in the testing set) as well as the suspensions (96, 30.5%). Overall, the correction rate of the random forest model on the testing set is 85%.

The out-of-bag correction rate is 84.7% in the training set and 85.0% in the testing set, suggesting the strong robustness of this model. Most importantly, Fig. 7 shows the relative importance of all independent variables included in the random forest model. We calculated the mean decrease Gini to evaluate the global importance of all variables by using the varImpPlot function in R. Once again, the result suggests that the inclusion of the text-image plays the most important role on Twitter’s suspensions. Notably, the importance outweighs the text in the tweets and retweet behaviors. The global importance of text-images outweighs other factors such as the number of friends, number of followers, and even whether the post was written in simplified Chinese.

Fig. 7.

Random forest model explaining suspensions (n = 942 in the training set)

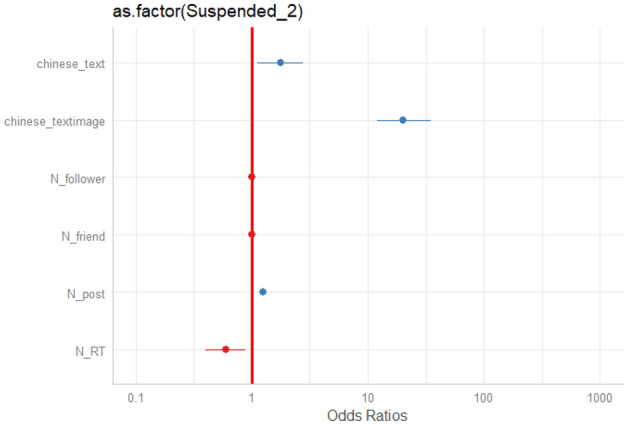

In the end, logit regression also evidences the importance of the text-image. The result of the logit model is shown in Table 2 and Fig. 8. In this model, the highest VIF is 1.88, indicating a low level of multicollinearity. The model also correctly predicts 81.1% of cases, albeit lower than the decision tree and random forest model. As is predicted by the model in Table 2, the inclusion of the text-image positively (p < 10–16) increases the chance of suspension from 8 to 65%, holding other variables at their means.

Table 2.

Logit regression explaining suspension

| DV: Suspended = 1 (as.factor(Suspended_2)) | |

|---|---|

| Text-image = 1 (chinese_textimage) | 3.00 (0.27)*** |

| Chinese text = 1 (chinese_text) | 0.56 (0.23)* |

| % of retweet (N_RT) | − 0.52 (0.26)* |

| N of post (N_post) | 0.22 (0.04)*** |

| N of friend (N_friend) | − 0.00 (0.00) |

| N of follower (N_follower) | − 0.00 (0.00) |

| Constant | − 2.93 (0.22)*** |

| N | 1256 |

| AIC | 1027.6 |

| % correct predict | 81.1% |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Fig. 8.

Logit regression model explaining suspensions (n = 1256)

Discussion

In this article, we reveal that simplified Chinese text-images played a key role in the USAVirus propaganda. Around three-fourth of the #USAVirus tweets came along with a simplified Chinese text-image that spread CCP-favorable narratives. These text-images shared a similar artistic style that was consisted of a title, a lengthy essay, and a few pictures. The temporal pattern of these tweets—between 8 am and 5 pm at Chinese Standard Time with a 2-h our lunch break—suggests that they were paid cyber armies or government employees located in China. The low level of engagement between these accounts further implies that they logged in Twitter only for spreading the propaganda. Analyzing Twitter’s removal archive further supports our argument. Similar posting time and engagement pattern showed up in Twitter’s archive as well. Most importantly, our analysis demostrates that Chinese text-images are a key determinant in Twitter’s June-12 mass suspension. Table 3 renders the cross-table of account suspension and whether the account posted a Chinese text-image before. The distribution in Table 3 reinforces our main findings in this article.

Table 3.

Cross-table between account suspension and Chinese text-image

| Account suspended by Twitter | Account not suspended | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Posted Chinese text-image | 445 | 215 | 660 (52.5%) |

| Never posted Chinese text-image | 30 | 566 | 596 (47.5%) |

| 475 (37.8%) | 781 (62.2%) | 1256 (100%) | |

Given the importance of these text-images, we can infer that the #USAVirus propaganda was more likely targeting Chinese users—overseas Chinese and China’s Great Firewall climbers—than US citizens. Twitter is banned in China but is an important platform for overseas Chinese and the Great Firewall climbers. The reason for disseminating #USAVirus might not be to influence the public opinion in the USA but to prevent overseas Chinese and the Great Firewall climbers from destabilizing the ruling of the Chinese Communist Party. In other words, not all attacks serve as an attack. Disinformation operations in a foreign land can be a means of internal control.

This article highlights the importance to analyze text-images in order to understand rapidly developing tactics of network propaganda on social media platforms. These text-images can be used to deliver messages that are different from their tweet text. Images can better catch users’ attention. They can also tell more complicated stories than 140-word tweets. Moreover, although text-images are readable by human eyes, using the machine to decode them needs extra efforts. It can also be a challenge for automatic content moderation if the text in these images are intentionally distorted or superimposed with pictures. As is shown in the examples in Fig. 2, several texts and sentences were blurred with the background, and some of which were even covered by pictures (such as the upper right example in Fig. 2). All these reasons made text-images a perfect medium for spreading disinformation and propaganda. In fact, these are exactly the reasons why we had difficulty to extract the complete text content from the text-images for analysis.

Although being a novice of Twitter, the Chinese government has been evolving on its deployment of propaganda tactics through coordinated disinformation and bot accounts [7, 14, 20]. Whereas Russia’s operations attempt at sowing discord and widening political division in the western countries [1, 2, 10], China’s foreign propaganda (daweixuan) tend to focus on creating “polyphonic Twitter content” that projects the “Chinese dream” [13] to the world as well as to its diaspora. The #USAVirus tweets echo such a practice. Through the lengthy simplified Chinese text-images that tell stories about the US failure on coronavirus and China’s victory, these tweets build a strong, moral image of China rising on the international stage. This hashtag emerged along with other disinformation campaigns—for example, the US military brought the COVID-19 virus into China—to shape a new narrative that strengthens nationalism among overseas Chinese and the Great Firewall climbers so as to defend the Chinese government from the discontent over the outbreak and spread of COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thanks HarpreKe for the help on data visualization.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the study: AH-EW, PS. Acquisition of data: AH-EW, M-HW. Analysis and/or interpretation of data: AH-EW, M-cL, M-HW. Drafting the manuscript: AH-EW, M-cL, PS. Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: M-HW.

Availability of data and material

Wang, Austin, 2020, "Replication Data for: #USAVirus analysis", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/O1TEYO, Harvard Dataverse, V1.

Code availability

R 3.1.3. Code is available in the link above.

Footnotes

https://transparency.twitter.com/en/information-operations.html Accessed 25 June 2020.

https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2020/information-operations-june-2020.html. Accessed 25 June 2020.

https://transparency.twitter.com/en/information-operations.html Accessed 25 June 2020.

https://tags.hawksey.info/get-tags/. Accesses 9 May 2020.

https://qz.com/1850097/chinese-propaganda-video-mocks-us-response-to-coronavirus-crisis/. Accessed 9 July 2020.

It is worth noticing that the distributions of the variables are skewed given the gap between the means and medians. The visualization of the distributions is upon request.

We decided to set the time zone of Fig. 4 as UTC-05:00 to illustrate the abnormal distribution of the Chinese-based #USA Virus tweet. We also use different time zone in Figs. 3 and 4 to show the preliminary evidence that the distribution of Chinese #USA Virus posts is closer to the Twitter’s public archive.

Given the low engagements among the accounts in our archive, the network visualization among these accounts does not provide additional contribution to the current analysis. The visualization of network is upon request.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Austin Horng-En Wang, Email: austin.wang@unlv.edu.

Mei-chun Lee, Email: lmclee@ucdavis.edu.

Min-Hsuan Wu, Email: ttcat@doublethinklab.org.

References

- 1.Bail CA, Guay B, Maloney E, Combs A, Hillygus DS, Merhout F, Volfovsky A. Assessing the Russian Internet Research Agency’s impact on the political attitudes and behaviors of American Twitter users in late 2017. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117(1):243–250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906420116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benkler Y, Faris R, Roberts H. Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridgman A, Merkley E, Loewen PJ, Owen T, Ruths D, Teichmann L, Zhilin O. The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: Understanding the role of news and social media. The Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. 2020 doi: 10.37016/mr-2020-028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caulfield, T. 2020. Pseudoscience and COVID-19—We’ve had enough already. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01266-z. Accessed 12 May 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Chernaskey, R. 2020 “Chinese State Media: A Shift in COVID-19 Coverage.” Foreign Policy Research Institute. https://www.fpri.org/fie/chinese-state-media-shift-covid-19/. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- 6.Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., Scala, A. 2020. The Covid-19 Social Media Infodemic. arXiv:2003.05004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Cook, S. (2020). “Beijing's Global Megaphone” Freedom House 2020 Special Report. https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/beijings-global-megaphone. Accessed 13 May 2020 .

- 8.Diresta, R. 2020. “For China, the ‘USA Virus’ Is a Geopolitical Ploy” The Atlantic Apr 11. 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/chinas-covid-19-conspiracy-theories/609772/. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- 9.Garimella, K., & Eckles, D. 2020. Images and Misinformation in Political Groups: Evidence from WhatsApp in India. HKS Misinformation Review, Jul 7, 2020. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/images-and-misinformation-in-political-groups-evidence-from-whatsapp-in-india/. Accessed 8 Jul 2020.

- 10.Guess A, Nyhan B, Reifler J. Selective exposure to misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. European Research Council. 2018;9:1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hameleers M, van der Meer TGLA, Brosius A. Feeling “Disinformed” lowers compliance with COVID-19 guidelines: Evidence from the US, UK, Netherlands and Germany. The Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. 2020 doi: 10.37016/mr-2020-023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hobbs WR, Roberts ME. How sudden censorship can increase access to information. American Political Science Review. 2018;112(3):621–636. doi: 10.1017/S0003055418000084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang ZA, Wang R. Building a network to “Tell China Stories Well”: Chinese diplomatic communication strategies on twitter. International Journal of Communication. 2019;13:24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kao, J., & Li, M. S. 2020. How China built a twitter propaganda machine then let it loose on coronavirus. Propublica Mar 26. 2020. https://www.propublica.org/article/how-china-built-a-twitter-propaganda-machine-then-let-it-loose-on-coronavirus. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- 15.King G, Pan J, Roberts ME. How the Chinese government fabricates social media posts for strategic distraction, not engaged argument. American Political Science Review. 2017;111(3):484–501. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao, J., Liu, Y., Chang, M., Ma, S. 2014. Analysis of the social impact of Weibo users based on Online Behavior. Chinese Journal of Computers. URL: https://www.thuir.org/group/~YQLiu/publications/cjoc.pdf.

- 17.Molter, V., & Diresta, R. 2020. Pandemics & propaganda: how Chinese state media creates and propagates CCP coronavirus narratives. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review Jun 8, 2020. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/pandemics-propaganda-how-chinese-state-media-creates-and-propagates-ccp-coronavirus-narratives.

- 18.Palmer, J. 2019. Decoding China’s 280-character web of disinformation. Foreign Policy Aug 21 2019. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/21/decoding-chinas-280-character-web-of-disinformation-twitter-facebook-fake-account-ban-hong-kong-protests-falun-gong-epoch-times-trump-carrie-lam-simon-cheng-cathay-pacific/.

- 19.Pei M, et al. Is CCP rule fragile or resilient? In: Diamond DW, et al., editors. Democracy in East Asia. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uren, T., Thomas, E., & Wallis, J. 2019. Tweeting through the Great Firewall. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/tweeting-through-great-firewall. Accessed 15 May 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Wang, Austin, 2020, "Replication Data for: #USAVirus analysis", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/O1TEYO, Harvard Dataverse, V1.

R 3.1.3. Code is available in the link above.