Abstract

Variations in the Forkhead Box G1 (FOXG1) gene cause FOXG1 syndrome spectrum, including the congenital variant of Rett syndrome, characterized by early onset of regression, Rett-like and jerky movements, and cortical visual impairment. Due to the largely unknown pathophysiological mechanisms downstream the impairment of this transcriptional regulator, a specific treatment is not yet available. Since both haploinsufficiency and hyper-expression of FOXG1 cause diseases in humans, we reasoned that adding a gene under nonnative regulatory sequences would be a risky strategy as opposed to a genome editing approach where the mutated gene is reversed into wild-type. Here, we demonstrate that an adeno-associated viruses (AAVs)-coupled CRISPR/Cas9 system is able to target and correct FOXG1 variants in patient-derived fibroblasts, induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) and iPSC-derived neurons. Variant-specific single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) and donor DNAs have been selected and cloned together with a mCherry/EGFP reporter system. Specific sgRNA recognition sequences were inserted upstream and downstream Cas9 CDS to allow self-cleavage and inactivation. We demonstrated that AAV serotypes vary in transduction efficiency depending on the target cell type, the best being AAV9 in fibroblasts and iPSC-derived neurons, and AAV2 in iPSCs. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of mCherry+/EGFP+ transfected cells demonstrated that the mutated alleles were repaired with high efficiency (20–35% reversion) and precision both in terms of allelic discrimination and off-target activity. The genome editing strategy tested in this study has proven to precisely repair FOXG1 and delivery through an AAV9-based system represents a step forward toward the development of a therapy for Rett syndrome.

Subject terms: Targeted gene repair, Neurodevelopmental disorders

Introduction

Ten years ago, we identified the Forkhead box G1 (FOXG1) gene as responsible for congenital Rett syndrome (RTT) [1, 2], first described by Rolando in 1985 [3] (OMIM #613454). In subsequent years, a wide range of pathogenic alterations involving FOXG1 gene have been identified, from point variations to partial or complete gene deletions and duplications, and the phenotypic spectrum has been extended [4–6]. Presently, autosomal dominant disorders associated to FOXG1 alterations are grouped under the definition of FOXG1 syndrome, with congenital RTT representing one of the conditions grouped within this spectrum [7]. The syndrome is characterized by early onset of regression, Rett-like and jerky movements, and cortical visual impairments, and it is distinguished by earlier symptoms onset within the first months of life [8]. FOXG1 is an autosomal gene located at 14q12 and encodes a brain-specific transcriptional repressor whose expression is restricted to fetal and adult brain and testis [1, 9]. FOXG1 is fundamental for early development of the telencephalon, which is affected by both FOXG1 overexpression and underexpression [10, 11]. It likely exerts relevant functions also in differentiating and mature neurons in the postnatal brain. Indeed, FOXG1 haploinsufficiency results in impaired neurogenesis in the postnatal hippocampus [12]. We found that it is expressed not only in the proliferating neuroepithelium but also in the differentiating cortical compartment in postnatal stages [1]. Since FOXG1 impairments have been reported as haploinsufficient genetic defects in RTT or overexpression in autism, we reasoned that conventional gene therapy approaches based on gene expression complementation would not represent a valid solution. The recently developed gene editing technology based on clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated endonuclease Cas9 enables modification of endogenous genes in a variety of cell types and it might provide a much more appropriate and effective strategy.

Once recruited by a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to a specific genomic target sequence, Cas9 induces double-strand breaks that can be repaired by either nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) pathways [13]. While NHEJ may produce undesired indels, HDR-based gene editing can restore the gene sequence using an exogenous donor DNA as template [14]. Therefore, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing would preserve the endogenous regulation, thus avoiding issues associated to classic gene replacement therapy, such as gene upregulation, downregulation, and cytotoxicity due to gene overexpression [15–17].

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing has been proven efficient to inactivate or correct endogenous genes in human cells both in vitro and in vivo [14, 18]. There is evidence that the CRISPR/Cas9 system is efficient in restoring normal Fragile X Mental Retardation 1 gene expression in Fragile X syndrome induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [19] and in correcting dystrophin reading frame in Duchenne muscular dystrophy iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and muscle cells [20, 21].

Several attempts have been made over the years to discover the ideal carrier for gene therapy. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have been used in a wide variety of tissues, including the brain [13], and are currently considered the preferred vehicle for gene therapy in the central nervous system, based on their neuronal tropism and stable transgene expression in postmitotic cells [22]. In the present study, we show an innovative CRISPR/Cas9 toolkit for FOXG1 gene editing in patient-derived cells.

Materials and methods

Patients selection

Patients fulfilling clinical and molecular criteria for the congenital variant of Rett syndrome were recruited at the Medical Genetics Unit of the University Hospital of Siena. Molecular diagnosis was accomplished after informed consent by performing sequencing analysis of the FOXG1 gene. Two patients affected by the congenital variant of Rett syndrome, carrying two distinct causative variants in FOXG1 gene, were selected for the study. Case 1 (#2237/17) harbors a missense variant (NM_005249.4: c.688C>T; p.(Arg230Cys)) expected to determine the disruption of the forkhead domain and consequently impair DNA binding. Case 2 (#156) harbors a nonsense variant (NM_005249.4: c.765G>A; p.(Trp255*)) [2]. The variants were submitted to the LOVD database (http://www.LOVD.nl/FOXG1) with individual IDs: #00288326 (#2237/17), #00288333 (#156).

Case 1 (#2237/17), a 4-year-old male, was diagnosed with congenital variant of RTT according to the current criteria [23]. Pregnancy, delivery, and auxological parameters at birth were normal. Head control was achieved at 3 weeks of age. At 3 months old, the patient presented microcephaly and reduced brain size and simplified convolutions were detected by MRI scan. At 15 months, inconsolable crying crisis started and lack of response to verbal prompts was evident. He presented tongue thrusting during feeding, right eye with intermittent tendency to squint, sialorrhea, gastroesophageal reflux, constipation, disturbed sleep-wake rhythm, snoring. The ability to grab small objects was acquired at about 24 months. He was able to laugh or scream spontaneously, but he could not sit or stand independently. At 22 months of age, head circumference was 44 cm (<3rd percentile), weight and length were 11 kg (25–50th) and 85 cm (50th), respectively. Prominent metopic suture and apparent hypotonia were also detected.

Case 2 (#156), a 33-year-old female, fulfilled clinical criteria for congenital variant of RTT. Abnormalities in head growth were observed at 3 months of age. The patient displayed inconsolable crying, lack of response to verbal prompts and poor head control. She has never been able to maintain a sitting position. At about 3 years, she acquired the ability to maintain a standing position, but then she lost it. Verbal language was limited to lallation and manual apraxia was evident. An MRI scan performed at about 10 years of age showed underdevelopment of cerebral hemispheres and corpus callosum thinning. At the age of 14 years she developed seizures, characterized by a fixed gaze and limb-shakes. The EEG showed occipital and right central-temporal basic rhythm slowing, occipital diffuse voltage reduction, central regions paroxysmal activity. Alterations of the sleep-waking rhythm, dystonic arm movements and constipation but no gastroesophageal reflux and respiratory rhythm alteration were reported. The physical examination carried out at the age of 22 revealed a weight of 38 kg (<5th percentile), head circumference of 49 cm (<3rd percentile), sunken eyes, high nasal bridge, full lips, large mouth, small hands with wide interphalangeal joints, severe scoliosis, joint stiffness, hypotrophic left leg, bilateral flat foot. Motor stereotypes of the hands on the midline, tongue thrusting and trunk swing, bruxism, sialorrhea, sporadic episodes of hyperventilation and cold hands and feet were evident.

Cell line establishment and maintenance

Primary human fibroblasts were obtained, following informed consent signature, from skin punch biopsy (size 3–4 mm3). Fibroblasts isolated from biopsies were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Biochrom GmbH, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Carlo Erba), 2% l-glutamine (Carlo Erba), and 1% antibiotics (Penicillin/Streptomycin) (Carlo Erba), according to standard protocols, and routinely passed 1:2 with Trypsin/EDTA (0.05%) solution (Irvine Scientific Santa Ana, CA, USA) [24].

Patient 1 iPSCs were generated and characterized from the Cell Technology Facility (CIBIO—University of Trento; https://www.cibio.unitn.it/467/cell-technology) using Sendai virus-encoded Yamanaka reprogramming factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC [25] (Fig. S1). Cells were maintained in feeders-free culture conditions in plates coated with Geltrex matrix diluted 1:100 in DPBS with Ca2+/Mg2+ (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Paisley, UK). Cells were cultured with mTeSR1 medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Grenoble, France) and routinely passed using EDTA 0.5 mM diluted in DPBS without Ca2+/Mg2+. iPSCs were differentiated into neuronal progenitors cells (NPCs) and neurons according to a previously published protocol [10, 26].

HEK293 cells were cultured in Advanced DMEM (Life Technologies TM, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM GlutaMax (Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were splitted routinely when 70–80% confluent.

Plasmids

We designed a system based on two plasmids to be used in combination: one plasmid carrying the Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) coding sequence (CDS), and the other one containing the sgRNA, under the control of U6 promoter, the donor DNA to be used for HDR and a reporter system to detect Cas9 activity in the cells (targeting plasmid). The pAAV2.1_CMV_EGFP3 was used as backbone [27] for the targeting construct and the genetic loads were inserted between the two inverted terminal repeats (ITR): the sgRNA and donor DNA were cloned into AflII/SacII sites, and the mCherry/EGFP reporter system [28] into NheI and SpeI sites. Variant-specific and wild-type (WT) sgRNA targets + PAM sequences (Table S1), necessary for the functioning of the fluorescent reporter system, were cloned between mCherry and EGFP sequences at the BsmBI restriction site. For Cas9, the PX551 plasmid encoding SpCas9 under the control of the MECP2 promoter was used [29]. An additional target sequence (sgRNA + PAM) was inserted between the Cas9 CDS and its promoter, using an AgeI restriction site, allowing Cas9 self-cleavage, thus avoiding long-term expression (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. Plasmid strategy and design.

a System functioning. Cells are infected with correction AAVs and constructs are expressed inside the cells. The targeting plasmid encodes three elements: the mutation-specific sgRNA leading Cas9 toward the target mutated site; the donor DNA used as template for homology-directed repair to restore the wild-type sequence; the reporter system composed by mCherry and EGFP fluorescent proteins allowing for confirmation of plasmids expression inside the cell. Since mCherry is constitutively expressed, cells transfected with the targeting plasmid will be mCherry+, irrespective of Cas9 expression. When cells are exposed to both targeting and Cas9 plasmids, Cas9 is expressed and it cleaves the target sequence between mCherry and EGFP; this allows EGFP expression, resulting in mCherry+/EGFP+ cells. One self-cleaving site allows for regulation of Cas9 expression. b sgRNA and donor DNA design. The diagram shows for each variant the selected sgRNA and donor DNA aligned to the mutated FOXG1 sequence. The mutated nucleotide is outlined in red and the PAM sequence in blue. The silent nucleotide substitution inserted to abolish the PAM is reported in bold in the donor sequence. c Overview of plasmids structure. The general structure of the targeting plasmid (left), for the delivery of the sgRNA and HDR donor template, and the Cas9 plasmid (right) are illustrated. AMPr ampicillin resistance gene, pBR322ori bacterial replication origin, ITR inverted terminal repeats.

Dual AAV system for plasmid delivery

The two components of the system, one encoding for self-inactivating SpCas9 and the other containing the sgRNA expression cassette and the donor DNA, were packaged into AAV2 and AAV9, known to transduce well cells in vitro and neurons in vivo, respectively. AAV vectors were produced by the TIGEM AAV Vector Core (http://www.tigem.it/core-facilities/vector-core) by triple transfection of HEK293 cells as already described [30].

Cell transfection

HEK293 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well the day prior to transfection, in order to obtain cells at 70–90% confluency on the day of transfection. Transfections were performed using polyethylenimine transfection reagent 1 μg/μL (Polysciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were transfected with 100 ng of targeting plasmid and 400 ng of Cas9 encoding plasmid. Fibroblasts were transfected using the Neon Transfection System with Tip100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were seeded 1 day before transfection and electroporated when 70–80% confluency was reached. A total of 1 × 106 cells were transfected with 5 μg of targeting plasmid and 5 μg of Cas9 plasmid using the following parameters: 1 pulse at 1700 V and 20 ms pulse width. After transfection, HEK293 and fibroblasts were seeded into 60 mm plates. Cells were left to grow in standard antibiotic-free culture medium for 24–48 h before performing further analysis. Transfection of iPSC-derived neurons was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation, Life Technologies) in accordance with manufacturer’s protocol. Transfection efficiency was assessed by fluorescence microscopy and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) 6 days following transfection.

For each experiment, untransfected cells and cells transfected with an EGFP-encoding plasmid were used as negative and positive controls to monitor transfection efficiency, respectively.

Infection with AAVs

Fibroblasts, iPSCs and iPSC-derived neurons were infected with AAV serotypes 2 and 9 to test their ability to transduce target cells. Fibroblasts and iPSCs were transduced with AAV9-EGFP and AAV2-EGFP control viruses, respectively, with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 × 105. Neurons were infected with EGFP-encoding control viruses with a MOI of 4 × 104, based on the existing literature. AAV9 infection was preceded by Neuraminidase treatment in order to expose the N-linked-galactose that acts as AAV9 receptor. To this aim, cells were treated with 50 mU of Endo-α-Sialidase (Neuraminidase, Millipore-Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) for 2 h at 37 °C. The medium containing Neuraminidase was then removed and fresh medium containing AAV9 without FBS and antibiotics was added. The plate was centrifuged for 2 min at 1100 rpm and then incubated for 1 h and 30 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, fresh medium with FBS was added and the plate was incubated overnight at 37 °C. After 24 h the medium containing the viral particles was removed and replaced with fresh medium. No pretreatment was required for AAV2 transduction because its membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan receptor is naturally expressed unmasked on cell surface. BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) was used to quantify the percentage of EGFP+ cells 48 h after transduction.

Subsequently, iPSCs and iPSC-derived neurons were transduced with AAV2 and AAV9 correction vectors, respectively. In both experiments 2 × 105 cells/well were seeded in 12-well plates. In the current state, cells were contextually transduced with AAV-targeting and AAV-Cas9 vectors. Co-transduced iPSCs were examined by fluorescence microscopy and the percentage of mCherry/EGFP positive cells was evaluated by FACS analysis 48 h after transduction. Treated iPSC-derived neurons were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy 6 days post infection.

Cell selection, genomic DNA isolation, and NGS genotyping

The transfection efficiency of fibroblasts was measured starting from 24 h after treatment by fluorescence microscopy. Forty-eight hours after treatment, cells were dissociated into single cell suspensions in PBS/EDTA 3 mM/Trypsin 2.5% for cell sorting. iPSC-derived neurons were analyzed 5 days after transfection by fluorescence microscopy. Cells were resuspended in PBS/EDTA 3 mM/Trypsin 2% before sorting. The BD FACSAria II (BD Biosciences, USA) cell sorter was used to isolate mCherry+/EGFP+ cells from transfected samples. Flow cytometric data were analyzed using FlowJo v7.5 (BD Biosciences, USA). Sorted fibroblasts were used for DNA isolation and genotyping.

DNA was isolated from sorted cells and untransfected control cells using QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to manufacturer’s instructions. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing efficiency was assessed by targeted deep sequencing using the Ion Torrent S5 apparatus on DNA isolated from duplicate experiments. Ion AmpliSeq 2.0TM Library Kit (Life Technologies) was used for library preparation. Libraries were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP system and quantified using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Life Technologies), pooled at an equimolar ratio, annealed to carrier spheres (Ion SphereTM Particles, Life Technologies), and clonally amplified by emulsion PCR using the Ion Chef system (Life Technologies). Ion 510TM, 520TM, or 530TM chips were loaded with the spheres carrying single stranded DNA templates and sequenced on the Ion Torrent S5 using the Ion S5TM Sequencing kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

FASTQ files were generated by the sequencing platform (S5 Torrent Server VM) and uploaded to Cas-analyzer [31, 32] along with the sgRNA sequence, the donor DNA sequence, and the mutant sequence. The percentage of HDR was thus calculated, considering a suitable comparison range of nucleotides around the cut site. Cas-analyzer output is the percentage of HDR that means the percentage of total reads that harbor the WT nucleotide. Considering that patient cells are heterozygous for FOXG1 variants, and thus ~50% of reads is expected to harbor the WT sequence, the percentage of mutated alleles reverted to the WT sequence is calculated as follows: HDR frequency reported by Cas-analyzer minus 50% WT alleles in untreated heterozygous patient cells to obtain the percentage of corrected alleles out of total alleles. To define the percentage of mutated alleles reverted to WT, this value is multiplied for 2. The .bam and .bai files were uploaded to IGV Visualization Software (Broad Institute, Cambridge, USA) to visualize the percentage of editing for any mutated nucleotide.

Off-target analysis

In order to investigate the genome-wide profile of off-target cleavages introduced by SpCas9 we performed GUIDE-seq analysis [33] in HEK293 cells engineered to harbor c.688C>T and c.765G>A variants.

In total, 2 × 105 HEK293 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) with 250 ng of sgRNA encoding plasmid, 500 ng of SpCas9 plasmid, 10 pmol of dsODNs, and 50 ng of a pEGFP-IRES-Puro plasmid, expressing EGFP, and the puromycin-resistance genes. The day after transfection cells were detached and selected with 1 μg/ml puromycin to eliminate untransfected cells. Cells were collected after 48 h and genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA was sheared to an average length of 500 bp using the Bioruptor Pico sonicator device (Diagenode). Library preparation, sequencing, and analysis were performed according to previous works [34].

Real-time qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Two micrograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed with the QuantiTect Reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was carried out in single-plex reactions in a 96-well optical plate with FastStart SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) on an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Experiments were performed in triplicate in a final volume of 20 μL with 25–100 ng of cDNA and 150 nM of each primer, following the SYBR Green protocol. Standard thermal cycling conditions were employed (Applied Biosystems): 2 min at 50 °C and 10 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The GAPDH or GUSB genes were used as reference. The results were analyzed using the comparative Ct method. GraphPad software was employed for statistical analysis. Unpaired Student’s t test with a significance level of 95% was used for the identification of statistically significant differences in expression levels.

Immunoblotting

Proteins from patient-derived fibroblasts and neuronal progenitors cells were extracted with tenfold excess of RIPA buffer (Tris-HCl 50 mM, NP-40 1%, Na-Deoxycholate 0.5%, SDS 0.1%, NaCl 150 mM, EDTA 2 mM, pH 7.4). Protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, Milano, Italy) was added to all lysates. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (20.000 g for 30 min at 4 °C) before western blot analysis. Protein concentration was measured with a Bradford Assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). A total of 15 μg and 30 μg of protein from cultured fibroblasts and neuronal progenitors cells, respectively, were used in each lane for immunoblotting. Immunosignals were detected by autoradiography using multiple exposures to ensure that signals were in the linear range. Signals were quantified through densitometry using ImageJ. The following antibodies were employed for analysis: anti-SpCas9 (Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, Inc. #7A9-3A3), anti-PAX6 (Millipore, Inc. #MAB5552), and anti-β-Actin (Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, Inc. #sc-47778).

Results

Strategy for gene correction and plasmid design

In order to deliver SpCas9 together with its sgRNA and a donor DNA to mutated cells exploiting AAV vectors, we designed a dual plasmid correction system to overcome the size limits of the AAV genome [35, 36]. The system is thus based on an SpCas9 expressing vector to be delivered in combination with a targeting vector (Fig. 1a).

The targeting plasmid contains a cassette expressing a variant-specific sgRNA to direct Cas9 selectively to the mutated allele and a 100 bp donor DNA centered on the variant that should act as template for HDR to restore the WT sequence (Table S1). In order to avoid the targeting of the donor sequence by SpCas9, we have disrupted the Palindromic Adjacent Motif (PAM) in the donor with a silent nucleotide substitution (TGG to TAG). We tested the system for the following two FOXG1 variants: c.688C>T and c.765G>A (Fig. 1b). The targeting plasmid also includes a fluorescent reporter system to monitor both transduction/transfection efficiency and SpCas9 activity (Fig. 1a). The reporter is based on an mCherry/EGFP cassette were mCherry is constitutively expressed, while EGFP expression is disrupted by the insertion of a sequence which keeps EGFP out of frame and which contains a variant-specific target sequence for Cas9 (sgRNA + PAM) (Table S1). Indels generated by SpCas9 cleavage on this site can lead to frameshifts that restore EGFP expression (Fig. 1a, c).

To limit the temporal window of SpCas9 expression, a target sequence represented by the variant-specific sgRNA plus a PAM sequence was inserted between the promoter and the CDS of the nuclease (Fig. 1c). Western blot analysis on whole protein extracts isolated from fibroblasts co-transfected with the targeting plasmid and a plasmid encoding either the self-cleaving Cas9 or a Cas9 in which the self-cleaving site has not been included, indicate that the presence of the self-cleaving site indeed limits SpCas9 expression (Fig. S2).

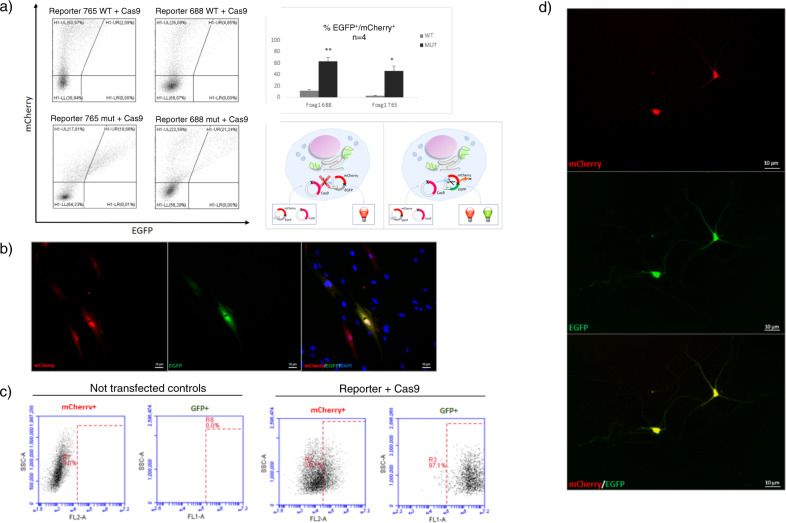

Fibroblasts and iPSC-derived neurons transfection efficiency

The specificity of the sgRNAs was tested by transient transfection of HEK293 cells (Fig. 2a). To this aim, we designed modified targeting plasmids in which the target sequence between mCherry and EGFP contained the WT nucleotide instead than the c.765G>A or the c.688C>T variants (Table S1). As expected, cells transfected with the targeting plasmids harboring the WT sequences inside the reporter system remained EGFP negative since the variant-specific sgRNA does not allow this sequence to be cut by Cas9. Cells transfected with the targeting plasmids containing the mutant sequence between mCherry and EGFP showed a marked increase in EGFP fluorescence, indicating the activation of Cas9 (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Transfection experiments.

a Plasmids functionality demonstration and sgRNA specificity. Representative results of FACS analysis on HEK293 cells 48 h after transfection with Cas9 plasmid and mCherry/EGFP targeting plasmid in which the target sequence between mCherry and EGFP harbors either the variant-specific (lower panel) or the wild-type sequence (upper panel), for c.765G>A and c.688C>T pathogenic variants, respectively, are shown. The population of mCherry+/EGFP+ cells is gated in the UR quadrant. Significant double mCherry/EGFP fluorescence is present only in the cells co-transfected with the variant-specific targeting plasmid and the Cas9 plasmid (18.66 and 21.24% for c.765G>A and c.688C>T, respectively for the presented experiment) demonstrating the specificity of the sgRNA. The presence of an mCherry+/EGFP+ population on the plots of cells transfected with the targeting plasmid harboring the wild-type target sequence between mCherry and EGFP is due to a residual aspecific activity of Cas9. The percentage of double positive population showed on histogram, confirms the sgRNA specificity for the variant-specific sequence. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired student’s t test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005). A cartoon illustrating the approach is presented on the right. b–c Plasmids activation in fibroblasts. Fibroblasts harboring the c.688C>T variant analyzed by in vivo fluorescence microscopy 48 h after co-transfection show the presence of double mCherry+/EGFP+ cells (b), also confirmed by FACS quantitation (c). A percentage of 50.7% of cells transfected with targeting and Cas9 plasmids in combination is mCherry+; 97.1% of mCherry+ cells are also EGFP+. Globally, 48.75% of cells are double mCherry+/EGFP+. Untransfected fibroblasts, used as negative control, are shown on the left. The y axis shows SSC (side scatter), and the x axis shows fluorescence intensity (FL2-A = mCherry; FL1-A = GFP). The dashed rectangle represents the gating for positive cells. The percentage of positive cells is indicated inside the graphs. d In vivo fluorescence imaging of iPSC-derived neurons. In vivo fluorescence microscopy images of iPSC-derived neurons harboring the c.688C>T variant 6 days after transfection showing double mCherry (upper panel) and EGFP (lower panel) expression. Images are ×20 (b) and ×40 (d) magnification.

The presence of an mCherry+/EGFP+ population around 50% after co-transfection in fibroblasts proves that our strategy can be successfully applied to patient-derived primary cells (Fig. 2b, c). In addition, we achieved 3.7 + 1.9% EGFP positivity after co-transfection of iPSC-derived neurons (n = 3), supporting the feasibility of transfection in a disease-relevant neural cellular model (Fig. 2d).

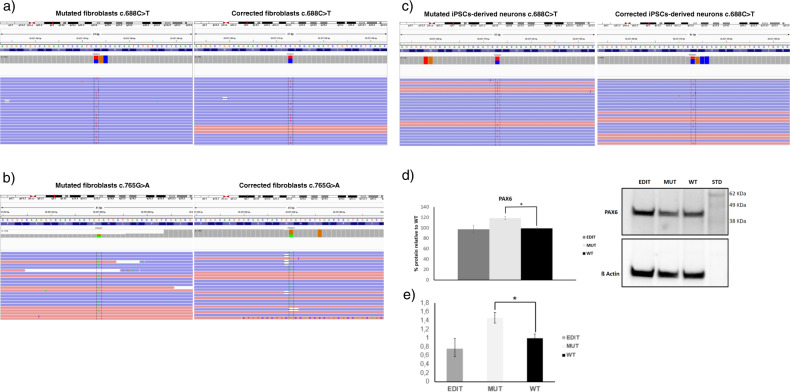

Gene editing efficiency

In order to demonstrate that the CRISPR/Cas9 system is able to effectively correct FOXG1 variants in patient-derived cells, co-transfected mCherry+/EGFP+ fibroblasts from both patients were isolated and analyzed by deep sequencing (n = 2 for each patient). Next-generation sequencing (NGS) results in native cells showed that the reads harboring the WT allele and those harboring the mutant allele were approximately the same, as expected in heterozygous samples. In transfected cells the percentage of reads harboring the WT allele increased, indicating that correction occurred (Fig. 3a, b). HDR efficiency was assessed by Cas-analyzer [37] using NGS data, taking into account a region of 100 nucleotides around the cut site. Correct editing count by Cas-analyzer assessed HDR efficiency over 20% for both patients (21 + 1.8% and 23.6 + 2.4% in case 1 and case 2, respectively) with 50% indels for case 1 and 20% for case 2. In order to test correction efficiency in a disease-relevant cellular model, we co-transfected iPSC-derived neurons harboring the c.688C>T variant. NGS/Cas-analyzer analysis of mCherry+/EGFP+ neurons demonstrated a high efficiency of editing, with ~34% mutated alleles reverted to the WT sequence and 38% indels (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. Sequencing analysis in edited patient-derived cells and PAX6 analysis.

a–c IGV visualization of NGS results in edited patient fibroblasts. Next-generation sequencing results for fibroblasts harboring c.688C>T and c.765G>A variants visualized with IGV tool are shown. The reference sequence is represented by colored letters, with the standard color code: adenine in green, cytosine in blue, guanine in yellow, and thymine in red. Right below, the coverage track displays reads depth for each nucleotide as a gray bar chart. Where a nucleotide differs from the reference sequence, the bar is colored accordingly, in proportion to the read count for each base. Each horizontal row (or track) represents one read, red for positive rightward (5′–3′) DNA strand, blue for negative leftward (reverse-complement) DNA strand. The regions encompassing the c.688C>T and c.765G>A variants are shown for native (left panel) and edited cells (right panel). The mutated nucleotide is reported between dashed lanes. The percentage of reads harboring the wild-type allele, measured as the percentage ratio between the read count of base C and the total number of reads, increases from 54 to 82% for the c.688C>T variant and from 51 to 65% for the c.765G>A variant. c IGV visualization show efficient editing in iPSC-derived neurons harboring the c.688C>T variant with 34% mutated alleles reverted to WT sequence and 38% indels. d PAX6 protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting on extracts obtained from wild-type, mutated, and edited neuronal progenitors cells and quantified with ImageJ. PAX6 levels significantly increase in mutated samples compared with WT and edited cells. Values on the y axis are the averages of percentage of proteins relative to WT normalized to b-Actin expression. n = 3. e PAX6 mRNA levels were evaluated by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD. The analysis confirmed PAX6 increase in mutated cells and normalization of its expression in edited ones also at mRNA level. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired student’s t test (*p < 0.05).

Off-target analysis

To evaluate the specificity of the correction plasmids, off-target analysis was performed by Guide-seq in HEK293 cells harboring the variants. This analysis pointed out 13 off-target sites for the c.688C>T variant and 6 off-target sites for the c.765G>A variant, all located in intronic or intergenic regions (Supplementary Tables 2, 3). To exclude an effect on gene expression, mRNA levels of genes interested by intronic off-targets were measured. Gene expression in mutant HEK293 cells transfected with the correction plasmids was analyzed and compared to gene expression in untreated cells using qRT-PCR. No statistically significant difference was observed (Fig. S3).

PAX6 expression analysis

It has been demonstrated that PAX6 protein levels are increased in patient-derived neuronal progenitors cells harboring FOXG1 mutations [10]. We thus tested if a similar alteration was also observed in cells harboring the c.688C>T (p.(Arg230Cys)) variant and if it was possible to restore the normal protein levels with gene editing by using our correction plasmids. Western blot and qRT-PCR analyses were performed on whole protein extracts and total RNA, respectively, isolated from WT, mutated, and transfected mCherry+/EGFP+ edited neuronal progenitors cells. In the mutated cells we observed an increase of PAX6 mRNA and protein levels compared with WT cells (Figs. 3d, e and S4). Following editing, a statistically significant decrease in the expression of PAX6 was observed with normalization to WT levels (Figs. 3d, e and S4).

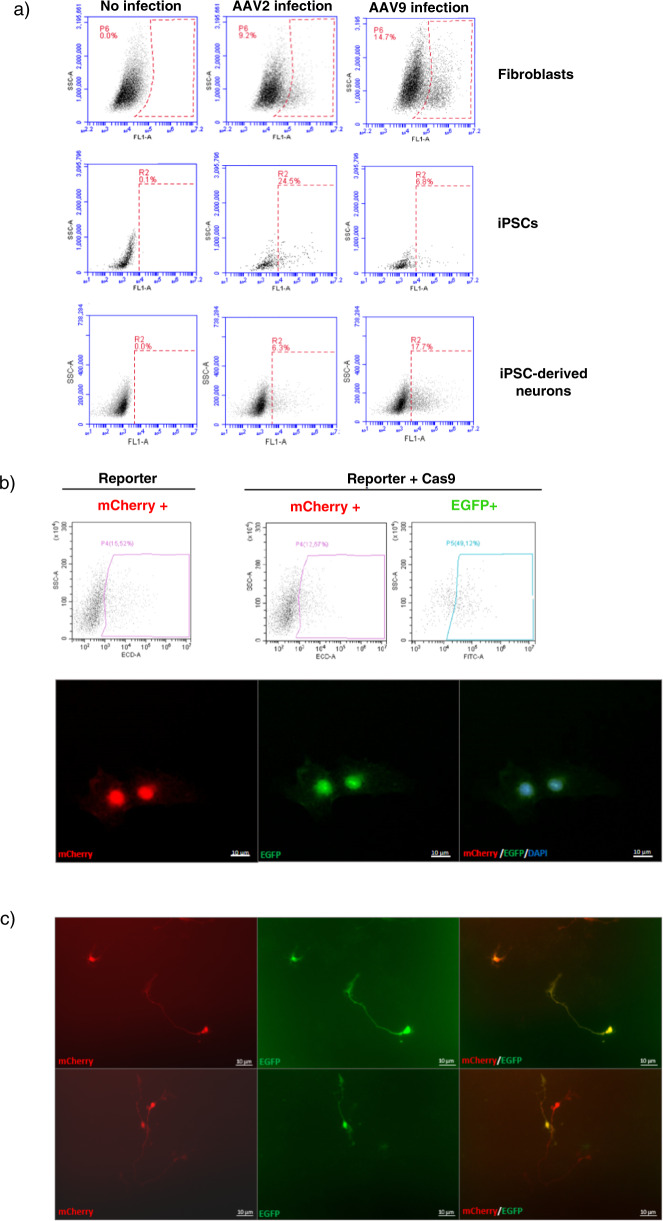

AAV2 vs AAV9: serotype-cell type correlation

We evaluated the most effective serotype for each cell type by testing AAV2 and AAV9 control viruses encoding EGFP, in fibroblasts, iPSCs, and iPSC-derived neurons (Fig. 4a). Serotypes 2 and 9 were selected since they have been proven efficient in both mitotic and postmitotic cells [13, 22].

Fig. 4. Infection in patient-derived cells.

a Serotype selection. FACS analysis of fibroblasts, iPSCs, and iPSC-derived neurons harboring the c.688C>T variant after infection with EGFP-AAV2 or EGFP-AAV9 control viruses. The y axis shows SSC (side scatter), and the x axis shows fluorescence intensity. The dashed rectangle represents the gating for positive cells. The percentage of positive cells is indicated in the figure. AAV2 is more efficient in iPSCs, with 24.5% EGFP+ cells compared with 6.8% when using AAV9. In total, 14.7% fibroblasts and 17.7% neurons were EGFP+ following AAV9 infection while AAV2 yielded only 9.2% and 6.3% EGFP+ cells, respectively. Untreated controls are shown on the left. b iPSCs infection. FACS quantitation (upper panel) and in vivo fluorescence imaging (lower panel) of infected iPSCs harboring the c.688C>T variant 48 h post infection are presented. The percentage of red and green fluorescent cells determined by FACS is indicated inside the graphs. A percentage of 12.67% cells infected with targeting and Cas9 AAVs in combination is mCherry+; 49.12% of mCherry+ cells are also EGFP+. Globally, 6.22% of cells are mCherry+/EGFP+. c Infection of iPSC-derived neurons. In vivo fluorescence imaging of infected iPSC-derived neurons harboring the c.688C>T variant 5–6 days post infection showing co-expression of mCherry and EGFP. Images are ×20 magnification.

FACS analysis 48 h after infection demonstrated that AAV2 is more efficient for iPSCs, with ~25% of EGFP+ cells compared with 7% with AAV9. On the contrary, about 15% fibroblasts and neurons were EGFP+ following AAV9 infection while AAV2 yielded less than 10% EGFP+ cells.

iPSCs and iPSC-derived neurons infection efficiency

We succeeded in proving the significant potential of AAV co-infection as delivery strategy for CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing constructs. Specifically, mutant iPSCs were infected with AAV2 correction vectors and examined by fluorescence microscopy and FACS sorting. Double mCherry+/EGFP+ cells were observed starting from 24 h post infection. Quantitation by FACS at 48 h showed 12.57% mCherry positive cells, 49.12% of which was also EGFP positive (Fig. 4b). iPSC-derived neurons harboring the variant were infected with AAV9 correction vectors and analyzed by in vivo fluorescence microscopy. The results showed that cells which express mCherry are also positive for EGFP, corroborating that these cells can be effectively co-infected (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that a specific innovative toolkit assembled using AVV-CRISPR/Cas9 technology with autoinactivation is able to target and correct FOXG1 variants in patient-derived cells, including iPSC-derived neurons.

FOXG1 gene expression needs to be tightly controlled, since it acts as a transcriptional repressor and even small deviations in FOXG1 levels or expression timing can disrupt brain function. Indeed, both heterozygous FOXG1 duplications and deletions are associated with FOXG1 syndrome, including congenital RTT, and increased FOXG1 expression is positively correlated with autism [11, 38]. Similarly, detrimental side effects resulting from aberrant peripheral transgene expression and liver toxicity have been previously reported as a relevant issue in MECP2 gene replacement therapy, which is another transcriptional regulator associated to Rett spectrum disorders [15–17]. For these reasons gene replacement, consisting in exogenous FOXG1 delivery, may not represent the therapeutic approach of choice in FOXG1-related disease. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing has been chosen over gene replacement since it has the unique advantage of preserving native regulation. Although our variant-specific gene editing system clearly requires to be shaped whenever a new variant is dealt with, since a specific sgRNA needs to be designed, it offers the major benefit of correcting the endogenous mutated allele of FOXG1 gene, thus maintaining its native regulation. If on one hand this approach implies a minor increase in complexity of the design of translational studies, on the other hand it ensures the preservation of spatio-temporal gene expression patterns and normal protein levels and it minimizes the risk of cell toxicity. Especially, since the overexpression of FOXG1 has been shown to be responsible for the overproduction of GABAergic neurons in patients with idiopathic autism, suggesting that a shift toward GABAergic neuron fate caused by FOXG1 is a developmental precursor of ASD [15], classic gene replacement therapy currently appears risky, unless the native FOXG1 promoter can be included in the therapeutic construct. Moreover, even if we wanted to increase the chances of a safe gene replacement approach by including the native FOXG1 promoter in the therapeutic construct, the recent identification of alternative transcription start sites and associated promoters for human FOXG1 gene [39] would complicate the generation of constructs for conventional gene therapy.

So far, only few studies have applied CRISPR/Cas9 to human primary cells isolated from patient tissues, mostly because of their limited lifespan. As opposed to immortalized cells, genome editing in primary cells presents numerous technical challenges [40, 41]. However, we considered it important to test our gene editing strategy in human primary cells. This ambition brought us to achieve successful gene editing in patient-derived fibroblasts. Our results obtained on cells from two patients harboring different variants in FOXG1 gene show that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing via HDR is over 20% effective in precisely restoring the native sequence when transfecting patient-derived fibroblasts. In 2014, Li et al. had previously reported 1.3% Cas9 RNP-mediated HDR in human primary neonatal fibroblasts [42]. Although the delivery system employed here is different, our results establish a clear increment in HDR-mediated editing efficiency in primary fibroblasts. Consistent with our findings, Schumann et al. generated knock-in genome modifications in primary human CD4+T cells using Cas9 RNPs with up to 20% efficiency [43].

In addition to primary fibroblasts, we demonstrated that the CRISPR/Cas9 system can be applied to the most relevant cells in FOXG1 syndrome pathogenesis, namely iPSC-derived neurons. In these cells the rate of HDR and NHEJ were around 35% and 38%, respectively. These results suggest that correction of pathogenic variants in patient cells is feasible also in postmitotic cells. Previous data indicate PAX6 overexpression in neuronal progenitors cells derived from patient iPSCs harboring FOXG1 variants [10]. To assess the functional outcome of gene correction with our toolkit we thus analyzed PAX6 expression in mutated and edited NPCs and we confirmed the increase in PAX6 expression in mutated cells and the normalization of protein levels in edited ones. FOXG1 plays an important role in progenitor proliferation in the telencephalon through cell autonomous mechanisms including the regulation of PAX6 expression. Pax6 downregulation in Foxg1−/− dorsal telencephalic cells in mice has been previously reported but this difference is likely due to the complex Pax6 regulation in the developing central nervous system [44].

In order to attain gene correction in patients, it will be essential to have a correction toolkit capable of efficiently reaching the brain. For this reason, we decided to set up a correction tool suitable for delivery via infection with AAVs, in view of future central nervous system-focused clinical studies for therapeutic applications. Among other viral vectors, AAVs have been reported to date to be more specific for genome editing with no observed adverse events. AAVs qualify as a very promising delivery vehicle for the central nervous system, because they can infect both dividing and nondividing cells with low immunogenicity and toxicity [13]. Our results demonstrate that infection via AAV2 is efficient in delivering CRISPR/Cas9 components to patient-derived iPSCs; conversely, infection via AAV9 is more efficient in delivering gene editing components to fibroblasts and iPSC-derived neurons, consistent with AAV9 reported preference for differentiated primary cells [45]. Indeed, we achieved 3–6% co-infection in patient-derived iPSCs and derived neurons following delivery of sgRNA and Cas9 complexes by AAV2 and AAV9 viruses, respectively. AAV9 functionality for neuronal delivery appears particularly promising due to its unique ability to cross the blood–brain barrier [46] and its recent successful employment for a phase 1 trial in spinal muscular atrophy [47]. It will be thus important to perform correction experiments in mouse models harboring the specific variants identified in patients, to confirm that efficient correction can be obtained also in vivo. Further functional experiments in both cellular and animal models will be necessary to confirm that the obtained correction efficiency is sufficient to revert disease-relevant phenotypes even after disease onset, as suggested from studies of MECP2 reactivation in symptomatic Mecp2-null KO mice [48].

Different administration routes will need to be investigated, including intravenous, intrathecal, and intracerebroventricular, to establish the most efficient delivery route for obtaining therapeutic correction. Finally, although our data suggest that co-infection can be obtained, the necessity to employ two viral particles reduces the effectivity of our toolkit. One potential approach to overcome this issue could be represented by the employment of modified AAV particles with increased infectivity for brain cells. The increasing employment of AAVs for gene therapy approaches is indeed fostering studies aimed at developing modified next-generation AAV vectors [49]. Consequently, as CRISPR/Cas9-based therapeutic approaches gain momentum, it is likely that new AAV vectors with increased infectivity and tissue-specific tropism will be developed in the next years. Alternatively, a shorter Cas9 version, SaCas9, derived from Staphylococcus aureus, could be employed to allow packaging all the toolkit components in a single AAV particle, provided a specific PAM for this nuclease is available close to the variants. This approach has been recently tested in Leber congenital amaurosis, in both cellular and animal models and a Phase I/II trial is currently being performed [50] (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03872479).

The importance of on-target selectivity is crucial when using gene editing approach, especially for therapeutic and clinical applications [51]. We have endeavored to reduce cellular toxicity and ensure specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 system by cloning a self-cleaving Cas9 with an sgRNA recognition sequence. Thanks to the resulting ability of Cas9 to inactivate itself, we obtain a reduced Cas9 expression and avoid persistence of Cas9 potentially leading to off-target effects. We assessed Cas9 off-target activity in the two investigated variants and reported a limited number of off-target sites that were exclusively placed in either intergenic or intronic regions and do not appear to impact on known regulatory elements; these results are supported by the specificity of the designed sgRNAs. Although this phenomenon could be of biological relevance, pinpointing that the toolkit could be potentially improved, we consider it unlikely to be of clinical significance. In many cases off-targets may not be relevant, since the majority of the genome is not expressed [40].

Overall, our findings provide further evidence that HDR-mediated gene editing using CRISPR/Cas9 represents a promising therapeutic tool for targeting pathological variants in patients with Rett spectrum disorders for whom no effective therapeutic alternatives are available, paving the way for further testing in RTT animal models.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank FOXG1 patients and their families. The “Cell lines and DNA bank of Rett Syndrome, X-linked mental retardation, and other genetic diseases,” member of the Telethon Network of Genetic Biobanks (project nos. GTB12001 and GFB18001), funded by Telethon Italy, and of the EuroBioBank network provided us with specimens. We thank Anna Cereseto, Antonio Casini, and Giulia Maule (Laboratory of Molecular Virology Department of Cellular, Computational, and Integrative Biology—CIBIO-Trento) for performing GUIDE-seq analysis and for critically revising the paper. This work was supported by a grant from FOXG1 Research Foundation. This work is generated within the ERN ITHACA (European Reference Network for Intellectual Disability Telehealth and Congenital Anomalies). We thank SienaGenTest srl, a Spin-off of the University of Siena (www.sienagentest.dbm.unisi.it) for gene editing efficiency analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from FOXG1 Research Foundation for the project “A glimpse of hope for FOXG1.”

Author contributions

SC, MLC, KC, AR, CS, and IM have made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and have been involved in drafting the paper. SD, FD, FTP, EF, FN, RT, AG, SF, and EB have made substantial contributions to acquisition and analysis of the data. DL, VL, and CL have made substantial contributions to interpretation of data and clinical evaluation. All authors have been involved in drafting the paper; they have given final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese Ethics Committee, Prot Name CRI, Prot n 12362_2018.

Informed consent

Informed consent was provided to the patients before blood drowning and skin biopsies.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Croci Susanna, Carriero Miriam Lucia

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41431-020-0652-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Ariani F, Hayek G, Rondinella D, Artuso R, Mencarelli MA, Spanhol-Rosseto A, et al. FOXG1 is responsible for the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papa FT, Mencarelli MA, Caselli R, Katzaki E, Sampieri K, Meloni I, et al. A 3 Mb deletion in 14q12 causes severe mental retardation, mild facial dysmorphisms and Rett-like features. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1994–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolando S. Rett syndrome: report of eight cases. Brain Dev. 1985;7:290–6. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(85)80030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeung A, Bruno D, Scheffer IE, Carranza D, Burgess T, Slater HR, et al. 4.45 Mb microduplication in chromosome band 14q12 including FOXG1 in a girl with refractory epilepsy and intellectual impairment. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52:440–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunetti-Pierri N, Paciorkowski AR, Ciccone R, Della Mina E, Bonaglia MC, Borgatti R, et al. Duplications of FOXG1 in 14q12 are associated with developmental epilepsy, mental retardation, and severe speech impairment. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:102–7. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kortüm F, Das S, Flindt M, Morris-Rosendahl DJ, Stefanova I, Goldstein A, et al. The core FOXG1 syndrome phenotype consists of postnatal microcephaly, severe mental retardation, absent language, dyskinesia, and corpus callosum hypogenesis. J Med Genet. 2011;48:396–406. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.087528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Filippis RD, Pancrazi L, Bjørgo K, Rosseto A, Kleefstra T, Grillo E, et al. Expanding the phenotype associated with FOXG1 mutations and in vivo FoxG1 chromatin-binding dynamics. Clin Genet. 2012;82:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boggio EM, Pancrazi L, Lo Rizzo C, Mari F, Meloni I, Ariani F, et al. Visual impairment in FOXG1-mutated individuals and mice. Neuroscience. 2016;324:496–508. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martynoga B, Morrison H, Price DJ, Mason JO. Foxg1 is required for specification of ventral telencephalon and region-specific regulation of dorsal telencephalic precursor proliferation and apoptosis. Dev Biol. 2005;283:113–27.. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patriarchi T, Amabile S, Frullanti E, Landucci E, Lo Rizzo C, Ariani F, et al. Imbalance of excitatory/inhibitory synaptic protein expression in iPSC-derived neurons from FOXG1(+/−) patients and in foxg1(+/−) mice. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:871–80. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariani J, Coppola G, Zhang P, Abyzov A, Provini L, Tomasini L, et al. FOXG1-dependent dysregulation of GABA/glutamate neuron differentiation in autism spectrum disorders. Cell. 2015;162:375–90.. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen Q, Wang Y, Dimos JT, Fasano CA, Phoenix TN, Lemischka IR, et al. The timing of cortical neurogenesis is encoded within lineages of individual progenitor cells. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:743–51. doi: 10.1038/nn1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishiyama J, Mikuni T, Yasuda R. Virus-mediated genome editing via homology-directed repair in mitotic and postmitotic cells in mammalian brain. Neuron. 2017;96:755–68.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinnett SE, Hector RD, Gadalla KKE, Heindel C, Chen D, Zaric V, et al. Improved MECP2 gene therapy extends the survival of MeCP2-null mice without apparent toxicity after intracisternal delivery. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2017;5:106–15.. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gadalla KKE, Vudhironarit T, Hector RD, Sinnett S, Bahey NG, Bailey MES, et al. Development of a novel AAV gene therapy cassette with improved safety features and efficacy in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2017;5:180–90.. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gadalla KKE, Bailey MES, Spike RC, Ross PD, Woodard KT, Kalburgi SN, et al. Improved survival and reduced phenotypic severity following AAV9/MECP2 gene transfer to neonatal and juvenile male Mecp2 knockout mice. Mol Ther. 2013;21:18–30. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C, Guan X, Du T, Jin W, Wu B, Liu Y, et al. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection of primary CD4+ T-cells by gene editing of CCR5 using adenovirus-delivered CRISPR/Cas9. J Gen Virol. 2015;96:2381–93.. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie N, Gong H, Suhl JA, Chopra P, Wang T, Warren ST. Reactivation of FMR1 by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of the expanded CGG-repeat of the fragile X chromosome. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0165499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Long C, Li H, McAnally JR, Baskin KK, Shelton JM, et al. CRISPR-Cpf1 correction of muscular dystrophy mutations in human cardiomyocytes and mice. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1602814. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young CS, Hicks MR, Ermolova NV, Nakano H, Jan M, Younesi S, et al. A single CRISPR-Cas9 deletion strategy that targets the majority of DMD patients restores dystrophin function in hiPSC-derived muscle cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:533–40. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saraiva J, Nobre RJ, Pereira de Almeida L. Gene therapy for the CNS using AAVs: the impact of systemic delivery by AAV9. J Control Release. 2016;241:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagberg B. Clinical manifestations and stages of Rett syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:61–5. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vangipuram M, Ting D, Kim S, Diaz R, Schüle B. Skin punch biopsy explant culture for derivation of primary human fibroblasts. J Vis Exp. 2013;77:e3779. doi: 10.3791/3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landucci E, Brindisi M, Bianciardi L, Catania LM, Daga S, Croci S, et al. iPSC-derived neurons profiling reveals GABAergic circuit disruption and acetylated α-tubulin defect which improves after iHDAC6 treatment in Rett syndrome. Exp Cell Res. 2018;368:225–35.. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auricchio A, O’Connor E, Hildinger M, Wilson JM. A single-step affinity column for purification of serotype-5 based adeno-associated viral vectors. Mol Ther. 2001;4:372–4. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niccheri F, Pecori R, Conticello S. An efficient method to enrich for knock-out and knock-in cellular clones using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:3413–23. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2524-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swiech L, Heidenreich M, Banerjee A, Habib N, Li Y, Trombetta J, et al. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:102–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X-L, Li G-H, Fu J, Fu Y-W, Zhang L, Chen W, et al. Highly efficient genome editing via CRISPR-Cas9 in human pluripotent stem cells is achieved by transient BCL-XL overexpression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:10195–215.. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tornabene P, Tiberi P, Minopoli R, Manfredi A, Mutarelli M, et al. Triple vectors expand AAV transfer capacity in the retina. Mol Ther. 2018;26:524–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doria M, Ferrara A, Auricchio A. AAV2/8 vectors purified from culture medium with a simple and rapid protocol transduce murine liver, muscle, and retina efficiently. Hum Gene Ther Methods. 2013;24:392–98. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2013.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai SQ, Zheng Z, Nguyen NT, Liebers M, Topkar VV, Thapar V, et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:187–97.. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casini A, Olivieri M, Petris G, Montagna C, Reginato G, Maule G, et al. A highly specific SpCas9 variant is identified by in vivo screening in yeast. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:265–71.. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naso MF, Tomkowicz B, Perry WL, Strohl WR. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for gene therapy. BioDrugs. 2017;31:317–34.. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinberg MS, Samulski RJ, McCown TJ. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy for neurological disease. Neuropharmacology. 2013;69:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park J, Lim K, Kim SJ, et al. Cas-analyzer: an online tool for assessing genome editing results using NGS data. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:286–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Florian C, Bahi-Buisson N, Bienvenu T. FOXG1-related disorders: from clinical description to molecular genetics. Mol Syndromol. 2012;2:153–63. doi: 10.1159/000327329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vitezic M, Bertin N, Andersson R, Lipovich L, Kawaji H, Lassmann T, et al. CAGE-defined promoter regions of the genes implicated in Rett syndrome. BMC Genom. 2014;15:1177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voets O, Tielen F, Elstak E, Benschop J, Grimbergen M, Stallen J, et al. Highly efficient gene inactivation by adenoviral CRISPR/Cas9 in human primary cells. Lewin AS, curatore. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0182974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martufi M, Good RB, Rapiteanu R, Schmidt T, Patili E, Tvermosegaard K, et al. Single-step, high-efficiency CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in primary human disease-derived fibroblasts. CRISPR J. 2019;2:31–40. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2018.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin S, Staahl BT, Alla RK, Doudna JA. Enhanced homology-directed human genome engineering by controlled timing of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. eLife. 2014;3:e04766. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schumann K, Lin S, Boyer E, Simeonov DR, Subramaniam M, Gate RE, et al. Generation of knock-in primary human T cells using Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512503112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manuel MN, Martynoga B, Molinek MD, Quinn JC, Kroemmer C, Mason JO, et al. The transcription factor Foxg1 regulates telencephalic progenitor proliferation cell autonomously, in part by controlling Pax6 expression levels. Neural Dev. 2011;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bell CL, Gurda BL, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. Identification of the galactose binding domain of the adeno-associated virus serotype 9 capsid. J Virol. 2012;86:7326–33. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00448-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Yang B, Mu X, Ahmed SS, Su Q, He R, et al. Several rAAV vectors efficiently cross the blood-brain barrier and transduce neurons and astrocytes in the neonatal mouse central nervous system. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1440–8. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy S, Shell R, Arnold WD, Rodino-Klapac LR, Prior TW, et al. Single-dose gene-replacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1713–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson L, Guy J, McKay L, Brockett E, Spike RC, Selfridge J, et al. Morphological and functional reversal of phenotypes in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Brain. 2012;135:2699–710. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buning H, Srivastava A. Capsid modifications for targeting and improving the efficacy of AAV vectors. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019;12:248–65. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruan GX, Barry E, Yu D, Lukason M, Cheng SH, Scaria A. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing as a therapeutic approach for leber congenital amaurosis 10. Mol Ther. 2017;25:331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X-H, Tee LY, Wang X-G, Huang Q-S, Yang S-H. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e264. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.