Abstract

There is a shortage of research models that adequately represent the unique mucosal environment of human ectocervix, limiting development of new therapies for treating infertility, infection, or cancer. We developed three microphysiologic human ectocervix models to study hormone action during homeostasis. First, we reconstructed ectocervix using decellularized extracellular matrix scaffolds, which supported cell integration and could be clinically useful. Secondly, we generated organotypic systems consisting of ectocervical explants co-cultured with murine ovaries or cycling exogenous hormones, which mimicked human menstrual cycles. Finally, we engineered ectocervix tissue consisting of tissue-specific stromal-equivalents and fully-differentiated epithelium that mimicked in vivo physiology, including squamous maturation, hormone response, and mucin production, and remained viable for 28 days in vitro. The localization of differentiation-dependent mucins in native and engineered tissue was identified for the first time, which will allow increased efficiency in mucin targeting for drug delivery. In summary, we developed and characterized three microphysiologic human ectocervical tissue models that will be useful for a variety of research applications, including preventative and therapeutic treatments, drug and toxicology studies, and fundamental research on hormone action in a historically understudied tissue that is critical for women’s health.

Introduction

There is growing interest in the development of a three-dimensional (3D) human ectocervical tissue model that accurately recapitulates in vivo human physiology for studies of infection, disease, infertility, and cancer. To date, several 3D models have been developed from neonatal foreskin to study viral infection and oncogenic transformation [1–4]. These keratinocyte models provide an effective way to study many of the pathogens that can infect reproductive tissues, but they more closely resemble cutaneous skin than the mucosal epithelium present in the ectocervix, which is anatomically and physiologically distinct. Since infection and HPV-induced cancers are exponentially higher in mucosal tissues than epidermis, a model that accurately reflects the distinct physiology of cervical tissue is necessary to improve treatments for women. Recently, Zuk et al. generated normal and cancerous cervical tissue models by seeding normal or cancerous immortalized cervical cells onto dermis obtained from neonatal foreskin [5]. Histological analysis showed many layers of epithelial cells grew on the dermis in each case, but the normal cervix model did not recapitulate the distinct histology of mature differentiated cervical epithelium, and instead resembled a more neoplastic phenotype. A model developed by DeGregorio et al. used primary cervical stromal cells to generate Extracellular matrix, which was then seeded with primary epithelial cells [6]. This model more closely mimics non-neoplastic tissue, though the epithelium still appeared much thinner than normal pre-menopausal cervical tissue, and IHC analysis showed low expression of Cadherin 1 (CADH1) and basement membrane (BM) component laminin (LAM), indicating cells may not be well adhered to each other, and perhaps not well-attached to the regenerated stroma due to decreased BM integrity. Although each of these models improved upon previous research, they were still unable to fully replicate the distinct histology of differentiated, non-neoplastic epithelium.

Hormone responsiveness of reproductive tissues is well-documented in the literature; however, many in vitro ectocervical studies did not include physiologic concentrations of hormones. Several included static concentrations of estradiol (E2) or progesterone (P4), while others included supraphysiologic concentrations or no hormone supplementation. Additionally, the role of stromal cells in epithelial differentiation and endocrine signaling in reproductive tissues has been well-documented in mice [7–9]. Indeed, tissue-specific stromal cells express hormone receptors and hormone-induced paracrine signaling between the stroma and epithelium is vital for maintaining homeostasis. We hypothesized that engineering the microphysiologic environment of ectocervical tissue, including endocrine and paracrine signaling, would support epithelial growth, differentiation and long-term culture of human ectocervical tissue, potentially enabling studies of infection, barrier defense mechanisms, and hormone response in a critically understudied tissue.

We sought to evaluate three methods of microphysiologic modeling that have been successfully utilized to model other stratified tissues, such as epidermis, cornea, and esophagus [4, 10, 11], with the addition of physiologic concentrations of ovarian hormones and tissue-specific stroma. Here we present methodology, validation, and characterization of recellularized ectocervical tissue, organotypic cervical tissue, and engineered cervical tissue (ECT) with physiologic endocrine support.

Materials and methods

Study participants and tissue acquisition

Subjects evaluated in this study were recruited between January 2015 and July 2017. Ectocervical tissue samples were collected with written consent from women undergoing hysterectomies at Northwestern University Prentice Women’s Hospital (Chicago, IL), according to an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol. Participants included women aged 32–49 undergoing hysterectomies for benign conditions (Supplementary Table S1). To increase replicability and eliminate extraneous variables, stringent guidelines were developed to identify a comparable set of samples for analysis. Inclusion criteria were: women who had not been on reproductive hormone treatments or contraceptives the 6 months before surgery, and whose date of reported last menstrual period was consistent with uterine cycle staging as determined by pathologist. Women who reported abnormal cycles or women in which significant cervical pathology was indicated (such as koilocytosis, neoplasia, infection, or cervicitis) were excluded from this study. After surgical removal, hysterectomy tissue was held in saline until pathological examination, and remaining ectocervical tissue was placed in Hank buffered saline solution at 4 °C until processing. Samples for ribonucleic acid (RNA) analysis of patient tissue (PT) were received the day of surgery and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80 °C. Patient samples used for ECT and histological analysis of native PT were received within 24 h of surgery and processed depending on downstream application.

Murine tissue collection

All mice were provided food and water, housed in polypropylene cages and exposed to 12-hour light/dark cycles at 23 ± 1 °C with 30–50% relative humidity. Animals were fed Teklad Global irradiated 2919 or 2916 chow (Teklad Global), which has minimal phytoestrogens. All methods were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments, procedures, and methods were carried out in accordance with the IRB-approved guidelines and regulations. Ovaries were isolated from 12-day-old CD-1 female mice as previously described [12]. For organotypic co-culture, ovaries were cut into four even pieces and two quarters of ovarian pieces were placed on a 0.4-μm cell culture insert (EMD Millipore Co), with 700 μl growth media (Supplementary Table S2).

Ectocervical cell isolation, expansion, and culture

Epithelial cells were isolated using techniques previously established for human keratinocyte cultures [4]. Briefly, tissue was trimmed of excess stroma, cut into 4-6 mm pieces, and placed in dispase (1 U/mL) in Dulbecco modified eagle medium/nutrient Ham mixture F-12 (Stemcell Technologies) overnight. Epithelial cells were removed from stroma with forceps after 24 h. Cells were dissociated using 0.25% trypsin and spun down at 1000G for 5 min. Epithelial cells were plated on 25% confluent feeder layers of J2-3T3 cells treated with mitomycin C (Calbiochem) for 2–2.5 h to induce cell cycle arrest. Feeder cells were cultured in Fibroblast Media (FM) until co-culture. Epithelial co-cultures with feeder cells were cultured in Ectocervical Media (EM) with additional 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF). Feeder cells were changed every 2–3 days by incubating at room temperautre in 0.48 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, which selectively detaches fibroblasts, leaving epithelial cells behind as described previously [4].

Stromal fibroblasts were isolated through explant outgrowth, as described previously [4]. Briefly, after removing epithelium, remaining tissue was placed in 0.25% trypsin for 2–3 h at 37 °C. Tissue was rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and explants cultured at 37 °C in FM. Media was changed every 2–3 days. Once fibroblasts migrated out, tissue was removed, and fibroblasts continued to proliferate and expand. All primary cells were passage 3 or earlier and never cryopreserved (see Supplementary Table S2 for culture media formulations).

Decellularization and recellularization of ectocervical tissue

Human ectocervical tissue was trimmed of excess stroma until approximately 1 mm thick, which contained the most apical stromal compartment and epithelium. Tissue was incubated with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 48 h, as was previously demonstrated in ovarian and endometrial tissues [13, 14] to remove all cellular material. The ECM left behind was rinsed in PBS and cut into 3 mm by 3 mm pieces to generate decellularized ectocervical scaffolds (DCES).

After decellularization, a dissecting microscope was used to determine tissue orientation. The stromal side had a rough, fibrous texture, and the epithelial-BM side appeared smooth and glassy. Similar to methods used by Ridky et al. to produce differentiated epithelium on devitalized dermis [1], the scaffolds were placed BM-side down on a 12-mm cell culture insert and seeded with 106 primary fibroblasts in a small amount of FM (approximately 100 μl) to encourage attachment to the scaffold rather than the insert. After 8–24 h, 700 μl of FM was added to submerge tissue. After 2–3 days of culture, scaffolds were placed BM-side up and cultured for 2 weeks to allow stromal cell integration. At this time, 106 epithelial cells were seeded in a small amount of EM on the apical side of scaffolds. The recellularized cervical tissue (RCT) was cultured for 2 weeks at the air–liquid interface in EM supplemented with 0.1 nM E2 to promote differentiation.

Preparation of explant tissue models for culture

Ectocervical tissue was washed twice with PBS containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and processed for culture within 24 h of surgery. Tissue was trimmed of excess stroma until pieces were approximately 1 mm thick and contained both stromal and epithelial compartments. Three-millimeter biopsy punches of trimmed tissue were then transferred to cell culture inserts for culture at an air–liquid interface (Figure 2A). Tissue explants were cultured without hormones for 2–5 days before exogenous hormone treatments or co-culture with murine ovarian tissue.

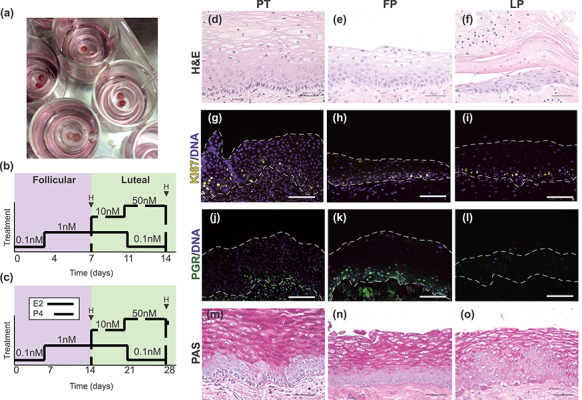

Figure 2.

Development and characterization of an organotypic ectocervical tissue model. Small biopsy punches from patient tissue that contained both stromal and epithelial regions were cultured at the air–liquid interface (A). Endocrine support was provided with murine ovarian tissue stimulated to secrete human menstrual cycle-like hormones or with step-wise exogenous hormone treatments that mimic normal concentrations of hormones throughout the menstrual cycle, and tissue analyzed mid-cycle after follicular phase (FP) hormones (D14) or at the end of the cycle (D28) after luteal phase (LP) hormones (B and C). H&E analysis of explant tissue revealed epithelial cells in different states of differentiation after follicular and luteal phase (FP and LP) hormones (E and F), similar to what is seen in native patient tissue (PT) (D). Immunofluorescence analysis of KI67 expression revealed that similar to PT (G), cells in the basal and parabasal layers of explant tissue remained proliferative throughout the 28-day culture (H and I). To assess hormone responsiveness, PGR expression was analyzed and revealed that FP explants expressed PGR abundantly in basal and parabasal cells (K), while LP explants showed little to no PGR expression (L). The presence of glycogenation/mucins was confirmed by PAS stain after FP and LP hormones, and similar to PT (M), intense staining in intermediate and superficial cells was observed with highest intensity in the FP samples (N and O). Scale bars = 50 μm.

Generation of engineered ectocervical tissue

To generate a cervical stromal equivalent, methods used to generate engineered dermis from neonatal foreskin were adapted with changes [4]. We seeded 3 × 105 primary fibroblasts and 3 × 105 J2-3T3 feeder cells in a collagen hydrogel consisting of: 4 mg/ml rat tail collagen, 10% reconstitution buffer, 10% 10x Dulbecco modified eagle medium (Sigma), 15 μl/ml 0.5 N NaOH, and ddH2O to final volume of 2 mL collagen/well. Hydrogels were formed on 30-mm cell culture inserts (EMD Millipore Co) in deep-well plates at 37 °C for 30 min, and then submerged in FM. After 24 h, 106 epithelial cells were seeded on each hydrogel and submerged with EM + 5% EGF above (2 mL) and below the cell-culture insert (14 mL). Once a monolayer of epithelial cells developed (5–7 days), ECT was cultured at an air–liquid interface with 9 mL EM for 5–7 days before beginning hormone treatments.

Ovarian hormone cycle and exogenous hormone treatments

To recapitulate human menstrual cycle hormone secretion, murine ovaries were cultured over 28 days, with the inclusion of both follicular phase (FP) and luteal phase (LP) pituitary hormones. During FP (days 0–14), tissues were co-cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 14 days with growth media containing 10 mIU/ml recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). On day 14, cultured ovarian tissue was stimulated with Maturation Media (Supplementary Table S2), containing human chorionic gonadotropin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 to trigger ovulation. During the LP (day 14–day 28), culture media did not contain FSH. For exogenous hormone treatments, E2 and P4 solutions were made in 100% EtOH and stored at −20 °C between uses. Four combinations of E2 and P4 were cycled through media over 14–28 days, to model ovarian hormone signaling during FP and LP, as we have previously shown [15]. Engineered and explant tissues were exposed to increasing levels of E2 (0.1–1.0 nM) for FP treatments (days 0–7 or 0–14), and rising levels of P4 (10–50nM) combined with decreasing E2 (1–0.01 nM) in the LP treatments (days 8–14 or 14–28), or with no hormones for the same time periods, with media replenished every 24–48 h.

Histological, immunofluorescence, and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) analysis

Ovarian and reconstructed or native ectocervical tissue were fixed in 10% formalin overnight. Tissues were dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol (50–100%) before being embedded in paraffin using an automated tissue processor. Tissue was sectioned for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), immunofluorescence (IF), and PAS staining. For IF, antigen retrieval was performed using sodium citrate buffer (pH 6) in a pressure cooker for 35 min. Sections were blocked with 10% goat serum for 1 h, before incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C (Supplementary Table S3). Sections were then stained with fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 h and imaged using NikonE600 fluorescent microscope. ImageJ software was used to measure epithelium in H&E-stained sections, from BM to apical surface of epithelium every 100 μm along entire length of the ECT, as has been shown previously [16]. Measurements were made by two researchers per sample and averaged to determine thickness (μm). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed, paired, student t-test in GraphPad Prism 7.

Total RNA isolation

Flash-frozen patient tissue weighing up to 100 mg was pulverized using a Biopulverizer (Biospec) and placed in 700 μl of Qiazol (Qiagen). Tissue solution was needle-sheared and then further broken down in Qiashredder columns (Qiagen). Engineered tissue was washed with PBS (Ca++, Mg+) before removing tissue from insert with a razor blade. Epithelium was separated from collagen hydrogel with forceps and placed in 700 μl of Qiazol, and needle-sheared. A RNEasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) was used for total RNA isolation, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations of RNA were determined using a nano-drop spectrophotometer, and RNA was stored in ribonuclease (RNAse)-free water at −80 °C until analysis.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

One microgram of isolated RNA per sample was combined with 4 μl of SuperScript VILO Mastermix (Invitrogen) and RNAse-free ddH2O to equal 20 μl reactions for complementary DNA synthesis. Samples were incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, 42 °C for 60 min, before terminating reactions at 85 °C for 10 min, per VILO instructions. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reactions (qRT-PCR) were performed in triplicate using a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher) and IDT gene expression assays (Integrated DNA Technologies, IL) to determine relative expression of each gene. All reactions were run 40 cycles (95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min) after initial 3 min incubation at 95 °C. Cycle thresholds (Ct) were calculated and normalized with ribosomal 18S (18 s ribosomal RNA) gene expression as a control. Ct was placed at approximate level where increases in amplification were parallel between samples. Gene expression in PT was calculated using the −log2 (ΔCt) method and displayed as fold change between sample groups. Gene expression in ECT was calculated using the –log2 (ΔΔCt) method, relative to patient-specific control for each treatment, and represented as FC over the corresponding control. Two-tailed, paired, student t-test was used to determine significance in engineered tissue and two-tailed Mann–Whitney test was used to determine significance in PT.

Results

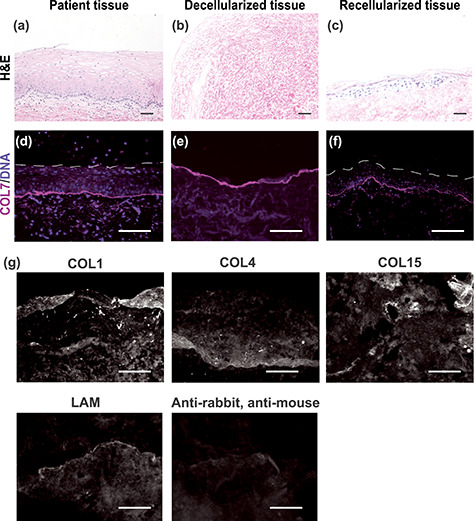

Development of recellularized ectocervical tissue model

We developed a 3D model of human ectocervical tissue using primary ectocervical epithelial and stromal cells seeded on decellularized ectocervical scaffolds (DCES). Decellularization efficiency was confirmed by evaluating H&E and DAPI staining in histological sections, which revealed that contrary to PT, the decellularized scaffold showed no nuclear staining (Figure 1A, B, D, and E). This indicates cellular material was effectively removed from the ECM. To ensure BM integrity, which is necessary for epithelial cell adhesion, we performed IF analysis of BM component collagen 7 (COL7) and observed similar localization and staining intensity in PT and DCES. This indicated the BM remained intact through the decellularization process (Figure 1D and E). Additional ECM-components COL1, COL4, COL15, and LAM were also confirmed in DCES (Figure 1G).

Figure 1.

Development of human recellularized ectocervical tissue. Recellularized ectocervical tissue was developed from human ectocervical tissue. Although patient tissue showed abundant nuclei in H&E- and DAPI-stained sections (A and D), decellularized tissue lacked nuclear staining (B and E), demonstrating cellular material was effectively removed from the ECM. Basement membrane integrity was examined by collagen 7 (COL7) immunofluorescence, which revealed intact basement membrane in decellularized tissue (E), closely resembling patient tissue (D). Decellularized ectocervical tissue was used as a scaffold for culture of primary ectocervical cells, with stromal cells seeded in the stromal compartment of the ECM, and epithelial cells seeded on the basement membrane. H&E and IF analysis of recellularized tissue revealed several layers of epithelial cells on top of intact basement membrane, and stromal cells throughout the ECM (C and F). Additional ECM-components COL1, 4, 15, and Laminin (LAM) were also confirmed in DCES (G). Scale bars = 50 μm.

To evaluate cell localization and tissue architecture, we performed H&E and IF staining, and observed cells throughout the stromal region of the RCT, and layers of epithelial cells on top of the DCES (Figure 1C and F). Epithelial cells underwent partial differentiation but never reached the full squamous maturation characteristic of native PT. In summary, decellularized ectocervical scaffolds maintain BM integrity and can support long-term culture of primary ectocervical stromal and epithelial cells; however, epithelial cell differentiation was impaired under the conditions tested in our studies.

Development and characterization of organotypic explant ectocervical tissue models

We aimed to develop a static culture system that would support physiologic responses in ectocervical tissue. To achieve this, we took 3-mm biopsy punches of patient cervical tissue that had been trimmed of extra tissue from the stromal side until tissue was approximately 1-mm thick and contained both stromal and epithelial regions (Figure 2A). Explants were cultured at the air–liquid interface on cell culture inserts for 14–28 days and provided endocrine support through the addition of varying concentrations of exogenous hormones E2 and P4 to mimic hormone signaling during the FP and LP of the human menstrual cycle (Figure 2B and C), or through co-culture with murine ovarian tissue that was stimulated to secrete human levels of hormones, as we have previously described [12]. Exogenous hormone treatments cycled through four different hormone concentrations to recapitulate the human menstrual cycle over a 28-day cycle, which included FP hormones during days 0–14 and LP hormones during days 15–28, or a reduced 14-day cycle, which included FP hormones during days 0–7 and LP hormones during days 8–14. These were compared with tissue cultured without hormones for the same time periods.

Interestingly, in the first 2 weeks of culture, the entire epithelium appeared to detach from the underlying stroma; however, H&E analysis of remaining stromal tissue showed that a basal layer of epithelial cells remained, and these cells then regenerated the differentiated epithelium (Supplementary Figure S1). After initial shedding and regrowth, H&E-stained sections from tissue harvested after FP (n = 12) or LP (n = 12) hormones showed that although overall epithelial thickness was decreased, the tissue architecture and epithelial differentiation of explant tissue closely resembled that of PT (n = 7) (Figure 2D–F). To assess long-term viability of explants, we analyzed KI67 expression in histological sections from samples harvested after FP (D7 or D14) and LP (D14 or D28) hormones, and found that similar to PT, KI67 was expressed in basal and parabasal cells of explant tissue after both FP and LP hormones, indicating the tissue remained proliferative for at least 28 days ex vivo (Figure 2G–I).

Increased expression of progesterone receptor (PGR) is a well-documented physiological response to E2 in human reproductive tissues [8, 17, 18]. To determine if static culture explants were responsive to E2, we analyzed PGR expression in histological sections from samples harvested after FP and LP hormones and found abundant PGR expression in basal and parabasal cells after FP hormones (high E2), similar to PT, and little to no expression of PGR in explants after LP hormones (low E2, high P4) (Figure 2J–L). This suggests that E2 induced expression of PGR in ectocervical explants, mimicking in vivo physiology. To evaluate glycogenation and mucin production, which are important components of barrier defense, PAS staining was performed. As in PT, we observed abundant glycogenation in intermediate and superficial layers of cells of explants after FP and LP hormones, with increased intensity after FP hormones (Figure 2M–O), further validating this physiologic model system. In summary, we found that cycling steroid hormones E2 and P4, from either endogenous or exogenous sources, were sufficient to induce physiologic responses to hormones in explants for at least 28 days in vitro.

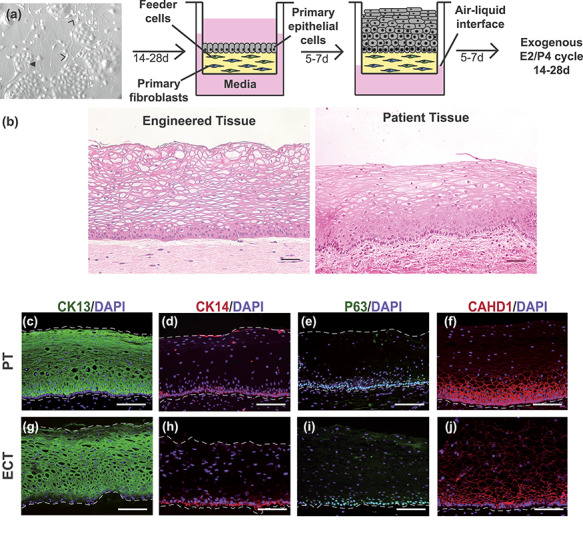

Development of engineered ectocervical tissue model

To mimic in vivo cervical physiology, we adapted tissue engineering methods commonly used to generate skin and added physiologic hormones and tissue-specific stroma. Primary ectocervical cells were isolated from benign patient hysterectomy tissue to engineer ectocervical tissue models consisting of well-differentiated epithelia on collagen hydrogel stromal-equivalents containing primary ectocervical fibroblasts and J2-3T3 feeder cells (Figure 3A). Feeder cells secrete growth factors that support epithelial differentiation in many 2D and 3D cultures [4, 19], while paracrine signaling from tissue-specific fibroblasts, which also express hormone receptors, are necessary to model the complex endocrine-signaling that occurs in this tissue. To account for this, equal amounts of feeder cells and primary fibroblasts were used. Engineered tissue remained viable 28 days at an Air-liquid interface and normal tissue architecture was observed. Similar to organotypic culture, endocrine support was provided by step-wise exogenous E2 and P4 over 14–28 days to represent physiologic concentrations during the FP and LP (Figure 2B and C). After 7–28 days, H&E staining of histological sections revealed fully stratified epithelium with correct basal-apical polarization, and cells in different states of differentiation (n = 6), mimicking key features of patient morphology (n = 7) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Development and characterization of engineered ectocervical tissue model. Primary ectocervical epithelial cells (closed arrowhead) were isolated and expanded on J2-3T3 feeder cells (open arrowheads) for 14–28 days. To generate a 3D stromal equivalent, fibroblasts and J2-3T3 cells were embedded in a collagen hydrogel on a cell culture insert. Epithelial cells were then seeded on the hydrogel and submerged in media for 5–7 days. Once a confluent monolayer formed, media was removed from above the cell insert and cultured engineered ectocervical tissue at the air–liquid interface for 5–7 days to enable squamous differentiation. Engineered cervical tissue was cultured at an air–liquid interface with ovarian hormone treatments. H&E staining of histological sections revealed engineered tissue matched the distinct morphology of native patient tissue with cells in multiple states of differentiation (A and B). Immunofluorescence analysis showed suprabasal cells expressed differentiation marker CK13 in both patient tissue PT and ECT, while basal cells expressed basal-marker CK14 (C, D, G, and H). P63, a driver of stratification, revealed expression in the nuclei of basal and parabasal cells of ECT and PT (E and I), while analysis of adherens junction protein CADH1 showed intense staining in basal and parabasal cell membranes with decreasing intensity in staining as cells become more differentiated in intermediate and superficial cells of ECT, mimicking expression patterns seen in PT (F and J). Scale bars = 50 μm.

Differentiation in engineered cervical tissue

To further investigate differentiation in ECT, we performed IF analysis of differentiation-associated proteins CK13, CK14, P63, and CADH1 in histological sections of engineered and PT, and found that CK13, a marker of suprabasal cells in non-keratinized stratified squamous tissue, was expressed abundantly in suprabasal cells of ECT and PT, while basal cell-marker CK14 was expressed in only basal layers (Figure 3C, D, G, and H), indicating basal and suprabasal differentiation. Additionally, we analyzed IF expression of stratification-driver P63, which is expressed in basal and parabasal cells of normal PT but can be expressed throughout the epithelium in neoplastic conditions [20, 21]. We observed P63 expression in basal and parabasal cells of engineered tissue indicating epithelial cells maintained the normal differentiation phenotype of benign PT (Figure 3E and )]. To determine if epithelial cells properly adhered to each other, we evaluated expression of adherens junction protein CADH1 and observed strong expression in basal and parabasal cells of ECT, with decreasing intensity in intermediate and superficial layers. This is consistent with expression patterns observed in PT (Figure 3F and J) and a previous report by Blakewicz et al. characterizing junctional protein localization in ectocervical biopsy tissue [22]. However, H&E stained-sections showed that engineered tissue cultured without ovarian hormones resulted in a thinner, pseudo-stratified epithelium that appeared to lack intermediate, differentiated cells (Figure 4A and B). Immunofluorescence analysis of CK13 expression revealed patchy expression in engineered tissue cultured without hormone treatments, with only the most apical cells matching the staining intensity seen in suprabasal layers after FP hormones (Figure 4C and D). This suggested many cells maintained a more basal-like phenotype when cultured without E2 and P4, highlighting the role of endocrine signaling during differentiation. Indeed, ECT cultured at the A/L interface with both paracrine and endocrine support can establish normal cell–cell adhesion and reach terminal differentiation, closely mimicking normal, non-neoplastic ectocervical tissue.

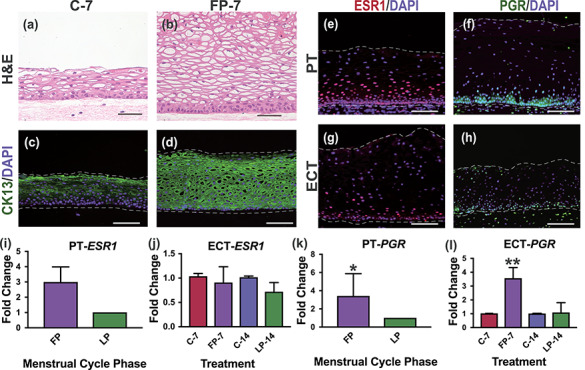

Figure 4.

Hormone response and receptor expression in ectocervical tissue. Engineered cervical tissue (ECT) cultured without ovarian hormones for 7 days (C-7) showed impaired differentiation compared with ECT cultured with follicular phase hormone treatments (FP-7), as demonstrated by tissue architecture, decreased thickness and lack of CK13-expressing intermediate cells (A–D). Immunofluorescence analysis of ESR1 and PGR revealed abundant expression throughout the stroma and in basal and parabasal cells of both patient tissue (PT) and engineered cervical tissue (ECT) (E–H). Analysis of gene expression revealed upregulated PGR in response to FP hormones in engineered ectocervix similar to expression in FP compared to LP patient tissue, while ESR1 expression was not significantly different (I–L). Scale bar = 50 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Hormone responsiveness in engineered cervical tissue

To investigate hormone responsiveness of ECT, we characterized hormone receptor expression and localization through IF and qRT-PCR analysis of ECT during a 14-day exogenous hormone cycle or no hormone treatments. We harvested tissue for analysis after FP (n = 3) or LP (n = 3) hormone treatments and compared with ECT cultured 7 (n = 3) or 14 (n = 3) days without hormones and with PT obtained from women in late FP (n = 4), when E2 levels are highest, and late luteal phase (n = 3), when E2 is low and P4 is high.

Immunofluorescence analysis revealed the localization of hormone receptors ESR1 and PGR in engineered tissue mimicked PT with expression observed throughout the stroma and in the basal and parabasal cells of the epithelium (Figure 4E–H). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis revealed ESR1 expression was not significantly different between FP and LP samples (Figure 4I and J). In contrast, engineered ectocervix harvested after FP hormone treatments showed significantly higher expression of PGR than in engineered tissue harvested after LP hormone treatments (P = 0.0097), which is consistent with the pattern seen in PT in which FP expression of PGR was significantly higher than in LP PT (P = 0.0286) (Figure 4K and L). This indicates that ECT cultured in vitro with physiologic concentrations of cycling exogenous hormones mimics the physiological response to E2 signaling that occurs across the menstrual cycle in vivo.

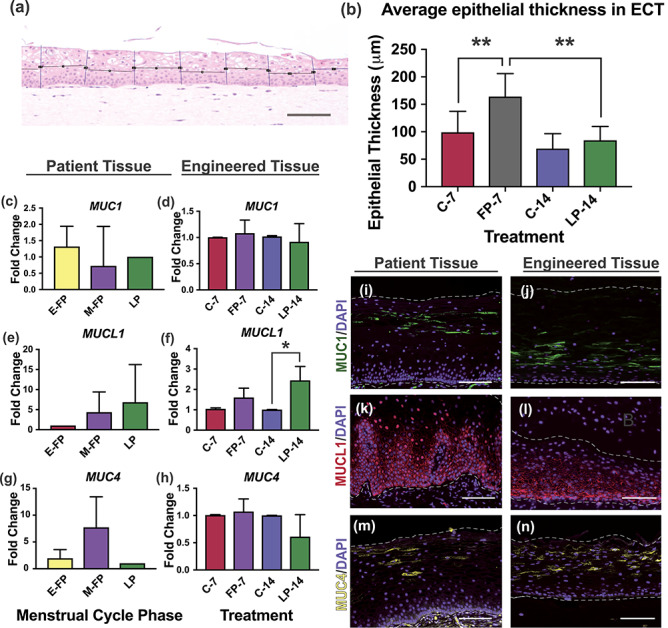

Much less is known about P4 signaling in ectocervical tissue during the menstrual cycle. However, studies in non-human primate cervical tissue and human vaginal tissue have shown a decrease in epithelial thickness during the LP [23, 24]. To determine if ECT recapitulated this phenotype, we averaged measurements of epithelial thickness in H&E-stained sections along the entire length of ECT harvested after FP and LP hormone treatments or after 7–14 days without hormone treatments. We observed a significant increase in thickness in FP ECT from day 7 (FP-7) compared with control ECT from day 7 (C-7) (P = 0.0039), with FP-7 ECT having an average thickness of 164.7 μm, and C-7 samples having an average thickness of 99.64 μm. Although there was little difference between control ECT from day 7 or 14 (C-7, C-14) and LP ECT from day 14 (LP-14), average epithelial thickness of LP-14 ECT was significantly thinner than FP-7 at 85.09 μm (P = 0.0039) (Figure 5A and B). It remains unclear if the thinner epithelium in the LP ECT is a direct effect of P4 signaling, or an indirect effect due to low E2 in the LP. This serves as proof of concept that ECT is hormone-responsive and mimics menstrual cycle phase-specific phenotypes when cultured with physiological levels of ovarian hormones.

Figure 5.

Epithelial thickness and mucin expression in engineered tissue. Epithelial thickness of engineered cervical tissue (ECT) from follicular and luteal phase treatments (FP-7, LP-14) or from control ECT (C-7, C-14) was measured and a significant increase in thickness was observed after FP treatments compared with C-7 or LP-14 (A and B). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that localization of ectocervical mucins MUC1, MUC4, and MUCL1 in engineered cervical tissue (ECT) mimicked patterns seen in patient tissue (PT), and expression was dependent on state of differentiation (I–N). Gene expression analysis of ECT revealed that although MUC1 was expressed constitutively across the menstrual cycle, MUCL1 was highly responsive to LP hormones, while MUC4 was not significantly different. Similar expression patterns were seen in PT from different phases of menstrual cycle, indicating ECT produces mucins in in vivo-like patterns during the menstrual cycle (C–H). Scale bars = 100 μm (A) and 50 μm (I–N), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Mucin expression in engineered cervical tissue

We sought to characterize localization and hormone responsiveness of ectocervical mucins in order to guide future investigations of drug delivery targeting mucins based on cellular location and potential application. We investigated IF expression of MUC1, MUC4, and MUCL1 in histological sections from C-7 (n = 3), FP-7 (n = 3), C-14 (n = 3), and LP-14 (n = 3) ECT and compared to PT from women in early FP (E-FP) (n = 3), mid-cycle FP (M-FP) (n = 4), and LP (n = 3). We found that transmembrane MUC1 was abundantly expressed in intermediate cells in both PT and ECT and absent in other layers, while MUCL1 was abundantly expressed in the membranes of basal and parabasal cells in PT and ECT and absent in intermediate and superficial layers (Figure 5I–L).

In contrast, MUC4 was observed primarily in superficial and intermediate cell membranes (Figure 5M and N), but was also observed in parabasal cells of some patients. Interestingly, the proportion of cells staining positive for MUC4 was highly variable between patients in both PT and ECT, and this was not correlated to menstrual cycle phase. To quantify mucin gene expression, we performed qPCR analysis of MUC1, MUC4, and MUCL1 on RNA from C-7 (n = 3), FP-7 (n = 3), C-14 (n = 3) and LP-14 (n = 3) engineered ectocervix and compared to PT from women in E-FP (n = 3), M-FP (M-FP) (n = 4), and LP (n = 3). Expression of MUC1 was not dependent on hormones in patient or engineered tissue (Figure 5C and D). MUC4 expression decreased between FP and LP in both patient and engineered ectocervix; however, this did not reach statistical significance in either case (Figure 5E and F). MUCL1 in vaginal organotypic models was previously reported to be E2-responsive by microarray [25]. Our data support this, as we saw an increase in the high-E2 FP of both PT and ECT compared with low E2 in E-FP or no E2 in C-7 ECT. However, we saw a more significant increase in the LP of both PT and ECT, with approximately a 1.6-fold and 6.8-fold increase in LP compared with early or mid-cycle, respectively (Figure 5G). We observed a 2.4-fold increase in MUCL1 expression in LP-14 compared with C-14 engineered tissue (P = 0.02) and a 1.5-fold increase between FP and LP engineered ectocervix (P = 0.02) (Figure 5H). Collectively, we have determined the differentiation-dependent localization of mucins 1, 4, and L1 in human ectocervical tissue for the first time and demonstrated that engineered ectocervix produces mucins in patterns that mimic PT, suggesting engineered ectocervical tissue could be a valuable tool to further our understanding of the ectocervical mucosal barrier, with implications for infection and disease, drug development, and toxicology studies.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to develop microphysiologic models of human ectocervical tissue for use in a wide range of experimental conditions (Supplementary Figure S2) and biological studies, such as homeostasis, pathogenic infection, cervical cancer, fertility and infertility, and cervical ripening and remodeling during and after pregnancy. We hypothesized that recapitulating the natural microenvironment of ectocervical tissue, with the endocrine and paracrine signaling that naturally take place in vivo, would enable squamous maturation, hormone response, and long-term culture. To test this, we developed three distinct microphysiologic models. First, we considered the use of native cervical ECM as a scaffold for tissue growth. DeGregorio et al. previously demonstrated that primary ectocervical epithelial cells could grow and differentiate on cell-specific regenerated ECM secreted by primary fibroblasts [6]. However, the morphology and cell–cell adhesion differed from what is seen in native tissue. Building on the idea of using cell-specific stroma, we investigated if the native architecture of ECM from tissue that had been decellularized could guide epithelial differentiation in order to reach full maturation. Although the cells were able to infiltrate and grow on the DCES, similar to DeGregorio model, epithelial thickness was decreased compared with PT, and we were not able to recapitulate mature differentiation under the conditions studied. However, it is worth noting that of the three models discussed here, the RCT has the highest potential for clinical use. For example, it would be possible to remove diseased cells from a patient’s excised tissue, leaving behind the ECM, and then recellularize the ECM with the same patient’s healthy cells, for transplantation or grafting. Although additional research is necessary before this can become a reality, it is not beyond the realm of possibilities, as a similar method has been used for years to generate skin grafts for patient use [26–28]. In recent murine studies, decellularized ECM has been used to restore ovarian function [14], generate vessels [29], or support islet transplantation in mice [30]. In all of these cases, when the scaffold was reintroduced to the niche environment in vivo, normal cell growth and function was resumed. In the case of cervical cancer and pre-cancer, in which the only treatment is to surgically remove affected tissue, the option to replace that tissue with the patient’s own regenerated healthy tissue may help improve the negative consequences to fertility associated with these treatments.

Next, a microphysiologic organotypic model system of ectocervical tissue with endocrine support provided by co-culture with murine ovarian tissue or through a step-wise exogenous hormone cycle was developed. Organotypic culture models have been developed for many human tissues and are a valuable research tool for studying physiology at the tissue level. Previously, we developed an ex vivo female reproductive tract that consisted of organotypic or reconstructed models of murine ovary, and human fallopian tube, uterus, cervix, and liver in a microfluidic culture system, which supported communication between tissues [12]. Murine ovarian tissue was engineered to secrete hormones in a pattern that mimics the human hormone cycle by supplementing culture medium with pituitary hormones FSH and luteinizing hormone. Cycling steroid hormones E2 and P4, along with other secreted factors, were circulated between each of the tissues, providing endocrine support over 28 days. Although this system is useful for studying tissue–tissue interactions among multiple tissues, a less complex method is needed to accelerate studies of ectocervical tissue at the cellular and molecular level.

We found that similar to our previous ex vivo model of the female reproductive tract (FRT) in microfluidic culture, this static culture method supported tissue viability for at least 28 days, and that while ovarian hormones were necessary, whether these came from ovarian tissue secretions or exogenous sources did not affect the results. The tissue responded to E2 by inducing PGR expression and maintained physiologic properties, such as glycogenation, throughout the culture. Some potential uses for this model include infection and toxicology studies, vaccine and drug development, or for basic research of tissue regeneration and differentiation. A benefit is that explant tissue can be used in experiments on the same day it is received, without the waiting period involved in isolating and expanding cells for tissue reconstruction and is particularly suited for hormonal response studies. However, the differences in epithelial shedding between patients made it difficult to study changes in proliferation and differentiation that occur over time. In order to study differentiation, consistency in the timing of epithelial regeneration is necessary. As such, we developed a more engineering-based approach, in which we are able to precisely control the timing of epithelial differentiation.

Advances in tissue engineering such as hydrogel-encapsulation, 3D-printing, and differential cell layering allow reconstruction of complex tissues with compartmentalized cells, including stratified squamous and mucosal tissues, such as skin, cornea and esophagus [4, 10, 11]. These methods rely on isolation/expansion of primary cells, increasing experimental scalability from a single donor. To engineer cervical tissue, we adapted tissue reconstruction methods that have been successful in other stratified culture models, with the additions of tissue-specific stroma for paracrine support, and physiological levels of cycling ovarian hormones for endocrine support. A cervical stromal-equivalent was generated by embedding primary fibroblasts and growth-factor secreting feeder cells in a collagen hydrogel. This stromal equivalent was able to support epithelial proliferation and differentiation and remained viable for at least 28 days. We found that estradiol was necessary for differentiation, and without it epithelium was thinner and absent of intermediate layers of cells. However, in the presence of hormones, engineered ectocervix reached full maturation, as demonstrated by the in vivo-like morphology and proper localization of differentiation proteins CK13, CK14, and P63. Additionally, engineered ectocervical tissue expressed hormone receptors in basal and parabasal layers and responded to hormones in ways that mimic in vivo hormone action, such as E2-induced PGR expression, mucin expression regulation, and LP epithelial thinning. The isolation and expansion of cells allowed us to compare different treatments on the same patient, rather than comparing between patients as in our explant system. This allowed us to identify significant results from a smaller sample size than would be necessary when comparing between samples from different patients. The ability to normalize experimental gene expression with control gene expression from the same patient decreased the standard deviation between experiments, and increased the significance as demonstrated by lower P values than what was observed when comparing PT, despite the higher number of samples.

We also investigated ectocervical mucin expression in these models. Mucins are heavily glycosylated transmembrane or secreted proteins that provide lubrication and hydration and contribute to the chemical and physical barrier properties of mucosal tissues. Previously, Gipson et al. and Ayehunie et al. reported gene expression of mucins 1, 4, and L1 (MUC1, MUC4, MUCL1) in human ectocervical and vaginal tissue; however, protein expression and localization were not investigated [15, 25, 31]. We confirmed the presence of ectocervical mucins MUC1, MUC4, and MUCL1 in ECT, and identified the differentiation-dependent localization of these mucins in patient cervical tissue for the first time, which is recapitulated in ECT. Mucins are a vital part of preventing infection and can inhibit the ability of microorganisms to breach the epithelial barrier. Mucins can also bind antibodies, acting as a reservoir of anti-microbial factors [32–34]. In many cases, such as in some cancers [35–37], abundant mucin production has inhibited drug delivery to its target. However, increasingly, researchers are harnessing this natural defense mechanism for targeted immunotherapy and drug delivery to mucosal tissues, or to increase vaccine efficiency [38–41]. The identification of differentiation-dependent mucin localization in the ectocervix will help us develop more efficient drug delivery based on the application. For example, MUC1 appears to be expressed constitutively across the menstrual cycle in the intermediate layers of cells, and so targeting this mucin may increase efficiency of preventative treatments, as these cells come into contact with microorganisms in the vaginal vault. However, for treatment of HPV, it would be more logical to target MUCL1, which is located in basal and parabasal layers, as HPV establishes infection in basal cells.

Although ECT has many advantages over other types of culture for studying differentiation, hormone response, and barrier defense, there are also several limitations to this model system. The length of time from acquisition of tissue to completion of an experiment can take up to 2 months. Additionally, we were unable to recapitulate mature differentiation in cells that had been cryopreserved, which limited the timing of our experiments and number of experiments possible. Previously, our group has developed protocols for standardized vitrification and warming and recovery of ovarian tissue for clinical research [42]. Currently, we are focused on adapting these methods to develop cryopreservation techniques for human ectocervix at both the tissue and cellular level that will enable regeneration of epithelium upon warming and recovery, which would exponentially increase the utility of this model. In conclusion, we have developed and validated three microphysiologic models of human ectocervical tissue, which include the endocrine and paracrine signaling that would be present in vivo, and outlined the benefits, limitations, and potential uses for each. This serves as a useful resource for a number of disciplines, such as virology, toxicology, and oncology, and represents a significant achievement for the inclusion of women in biological research of infections or diseases that present different challenges in women than men, such as HPV-induced cancer. Indeed, this paves the way for a more personalized approach to gynecological research and will propel much needed research on a critical tissue for women’s health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank patients who donated tissue through Gynecological Tissue Library at NU, S. Malpani and M. Connelly for obtaining consent and coordinating tissue-acquisition, L. Laimins for donation of J2-3T3 cells, S. Xiao for murine ovarian tissue, P. Hoover, S. Pazhampally and A. Kobieski at NU-Skin Disease Research Center for technical expertise and processing/sectioning tissue, C. Murray, K. Barreto, and N. Madjer for histological processing/sectioning, and K. Maniar, J.J. Kim, and J. Burdette for subject-matter expertise.

Contributor Information

Kelly E McKinnon, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Rhitwika Sensharma, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Chloe Williams, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Jovanka Ravix, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Spiro Getsios, Department of Dermatology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago IL, USA.

Teresa K Woodruff, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

- 1. Ridky TW, Chow JM, Wong DJ, Khavari PA. Invasive three-dimensional organotypic neoplasia from multiple normal human epithelia. Nat Med 2010; 16:1450–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang W, Hong S, Maniar KP, Cheng S, Jie C, Rademaker AW, Krensky AM, Clayberger C. KLF13 regulates the differentiation-dependent human papillomavirus life cycle in keratinocytes through STAT5 and IL-8. Oncogene 2016; 35:5565–5575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heuser S, Hufbauer M, Marx B, Tok A, Majewski S, Pfister H, Akgul B. The levels of epithelial anchor proteins beta-catenin and zona occludens-1 are altered by E7 of human papillomaviruses 5 and 8. J Gen Virol 2016; 97:463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simpson CL, Kojima S.I, Getsios S. RNA interference in keratinocytes and an organotypic model of human epidermis. In: Turksen K. (ed.) Epidermal Cells: Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2010: 127–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karolina Zuk A, Wen X, Dilworth S, Li D, Ghali L. Modeling and validating three dimensional human normal cervix and cervical cancer tissues in vitro. J Biomed Res 2017; 31:240–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Gregorio V, Imparato G, Urciuolo F et al. An engineered cell-instructive stroma for the fabrication of a novel full thickness human cervix equivalent in vitro. Adv Healthc Mater 2017; 6(11). doi: 10.1002/adhm.201601199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cunha GR, Cooke PS, Kurita T. Role of stromal-epithelial interactions in hormonal responses. Arch Histol Cytol 2004; 67:417–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurita T, Lee KJ, Cooke PS, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB, Cunha GR. Paracrine regulation of epithelial progesterone receptor by estradiol in the mouse female reproductive tract. Biol Reprod 2000; 62:821–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buchanan DL, Kurita T, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB, Cunha GR, Cooke PS. Role of stromal and epithelial estrogen receptors in vaginal epithelial proliferation, stratification, and cornification. Endocrinology 1998; 139:4345–4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang S, Ghezzi CE, Gomes R, Pollard RE, Funderburgh JL, Kaplan DL. In vitro 3D corneal tissue model with epithelium, stroma, and innervation. Biomaterials 2017; 112:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Green NH, Corfe BM, Bury JP, Mac Neil S. Production, characterization and potential uses of a 3D tissue-engineered human esophageal mucosal model. J Vis Exp 2015; (97), e52693 10.3791/52693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xiao S, Coppeta JR, Rogers HB, Isenberg BC, Zhu J, Olalekan SA, McKinnon KE, Dokic D, Rashedi AS, Haisenleder DJ, Malpani SS, Arnold-Murray CA et al. A microfluidic culture model of the human reproductive tract and 28-day menstrual cycle. Nat Commun 2017; 8:14584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olalekan SA, Burdette JE, Getsios S, Woodruff TK, Kim JJ. Development of a novel human recellularized endometrium that responds to a 28 day hormone treatment. Biol Reprod 2017; 29:971–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laronda MM, Jakus AE, Whelan KA, Wertheim JA, Shah RN, Woodruff TK. Initiation of puberty in mice following decellularized ovary transplant. Biomaterials 2015; 50:20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gipson IK, Spurr-Michaud S, Tisdale A, Menon BB. Comparison of the transmembrane mucins MUC1 and MUC16 in epithelial barrier function. PLoS One 2014; 9:e100393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laronda MM, Rutz AL, Xiao S, Whelan KA, Duncan FE, Roth EW, Woodruff TK, Shah RN. A bioprosthetic ovary created using 3D printed microporous scaffolds restores ovarian function in sterilized mice. Nat Commun 2017; 8:15261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vazquez-Martinez ER, Camacho-Arroyo I, Zarain-Herzberg A, Rodriguez MC, Mendoza-Garces L, Ostrosky-Wegman P, Cerbon M. Estradiol differentially induces progesterone receptor isoforms expression through alternative promoter regulation in a mouse embryonic hypothalamic cell line. Endocrine 2016; 52:618–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurita T, Young P, Brody JR, Lydon JP, O'Malley BW, Cunha GR. Stromal progesterone receptors mediate the inhibitory effects of progesterone on estrogen-induced uterine epithelial cell deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis. Endocrinology 1998; 139:4708–4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barreca A, Luca M, Monte PD, Bondanza S, Damonte G, Cariola G, Marco E, Giordano G, Cancedda R, Minuto F. In vitro paracrine regulation of human keratinocyte growth by fibroblast-derived insulin-like growth factors. J Cell Physiol 1992; 151:262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kurita T, Cunha GR, Robboy SJ, Mills AA, Medina RT. Differential expression of p 63 isoforms in female reproductive organs. Mech Dev 2005; 122:1043–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Romano RA, Smalley K, Magraw C, Serna VA, Kurita T, Raghavan S, Sinha S. Delta Np63 knockout mice reveal its indispensable role as a master regulator of epithelial development and differentiation. Development 2012; 139:772–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blaskewicz CD, Pudney J, Anderson DJ. Structure and function of intercellular junctions in human cervical and vaginal mucosal epithelia. Biol Reprod 2011; 85:97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patton DL, Thwin SS, Meier A, Hooton TM, Stapleton AE, Eschenbach DA. Epithelial cell layer thickness and immune cell populations in the normal human vagina at different stages of the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 183:967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hafez ESE, Jaszczak S. Comparative anatomy and histology of the cervix uteri in non-human primates. Primates 1972; 13:297–314. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ayehunie S, Islam A, Cannon C, Landry T, Pudney J, Klausner M, Anderson DJ. Characterization of a hormone-responsive organotypic human vaginal tissue model: morphologic and immunologic effects. Reprod Sci 2015; 22:980–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Terino EO. Alloderm acellular dermal graft: applications in aesthetic soft-tissue augmentation. Clin Plast Surg 2001; 28:83–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Achauer BM, Vander Kam VM, Celikoz B, Jacobson DG. Augmentation of facial soft-tissue defects with Alloderm dermal graft. Ann Plast Surg 1998; 41:503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wainwright DJ. Use of an acellular allograft dermal matrix (AlloDerm) in the management of full-thickness burns. Burns 1995; 21:243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wong MM, Hong X, Karamariti E, Hu Y, Xu Q. Generation and grafting of tissue-engineered vessels in a mouse model. J Vis Exp: JoVE 2015; (97), 52565. 10.3791/52565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang K, Wang X, Han CS, Chen LY, Luo Y. Scaffold-supported transplantation of islets in the epididymal fat pad of diabetic mice. J Vis Exp: JoVE 2017; (125), 54995. 10.3791/54995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gipson IK, Ho SB, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Tisdale AS, Zhan Q, Torlakovic E, Pudney J, Anderson DJ, Toribara NW, Hill JA 3rd. Mucin genes expressed by human female reproductive tract epithelia. Biol Reprod 1997; 56:999–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gunn B, Schneider J, Shansab M, Bastian AR, Fahrbach K, Smith A, Mahan A, Karim M, Licht A, Zvonar I, Tedesco J, Anderson M et al. Enhanced binding of antibodies generated during chronic HIV infection to mucus component MUC16. Mucosal Immunol 2016; 9:1549–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen A, McKinley Scott A, Wang S, Shi F, Mucha Peter J, Forest MG, Lai SK. Transient antibody-mucin interactions produce a dynamic molecular shield against viral invasion. Biophys J 2014; 106:2028–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fahrbach KM, Malykhina O, Stieh DJ, Hope TJ. Differential binding of IgG and IgA to mucus of the female reproductive tract. PLoS One 2013; 8:e76176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rao CV, Janakiram NB, Madka V, Kumar G, Scott EJ, Pathuri G, Bryant T, Kutche H, Zhang Y, Biddick L, Gali H, Zhao YD et al. Small-molecule inhibition of GCNT3 disrupts mucin biosynthesis and malignant cellular behaviors in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 2016; 76:1965–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu ZZ, Xie XD, Qu SX, Zheng ZD, Wang YK. Small breast epithelial mucin (SBEM) has the potential to be a marker for predicting hematogenous micrometastasis and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis 2010; 27:251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Munro EG, Jain M, Oliva E, Kamal N, Lele SM, Lynch MP, Guo L, Fu K, Sharma P, Remmenga S, Growdon WB, Davis JS et al. Upregulation of MUC4 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma: pathologic significance. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2009; 28:127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rao CV, Janakiram NB, Mohammed A. Molecular pathways: mucins and drug delivery in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23:1373–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Amini A, Masoumi-Moghaddam S, Morris DL. Mucins and tumor biology In: Amini A, Masoumi-Moghaddam S, Morris DL (eds.), Utility of Bromelain and N-Acetylcysteine in Treatment of Peritoneal Dissemination of Gastrointestinal Mucin-Producing Malignancies. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016: 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang H, Liu C, Zhang F, Geng F, Xia Q, Lu Z, Xu P, Xie Y, Wu H, Yu B, Wu J, Yu X et al. MUC1 and survivin combination tumor gene vaccine generates specific immune responses and anti-tumor effects in a murine melanoma model. Vaccine 2016; 34:2648–2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alkholief M, Campbell RB. Investigating the role of mucin in the delivery of nanoparticles to cellular models of human cancer disease: an in vitro study. Nanomedicine 2016; 12:1291–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Laronda MM, McKinnon KE, Ting AY, Le Fever AV, Zelinski MB, Woodruff TK. Good manufacturing practice requirements for the production of tissue vitrification and warming and recovery kits for clinical research. J Assist Reprod Genet 2017; 34:291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.