Abstract

BACKGROUND

Distinguishing adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma subtypes of non-small cell lung cancers is critical to patient care. Preoperative minimally-invasive biopsy techniques, such as fine needle aspiration (FNA), are increasingly used for lung cancer diagnosis and subtyping. Yet, histologic distinction of lung cancer subtypes in FNA material can be challenging. Here, we evaluated the usefulness of desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging (DESI-MSI) to diagnose and differentiate lung cancer subtypes in tissues and FNA samples.

METHODS

DESI-MSI was used to analyze 22 normal, 26 adenocarcinoma, and 25 squamous cell carcinoma lung tissues. Mass spectra obtained from the tissue sections were used to generate and validate statistical classifiers for lung cancer diagnosis and subtyping. Classifiers were then tested on DESI-MSI data collected from 16 clinical FNA samples prospectively collected from 8 patients undergoing interventional radiology guided FNA.

RESULTS

Various metabolites and lipid species were detected in the mass spectra obtained from lung tissues. The classifiers generated from tissue sections yielded 100% accuracy, 100% sensitivity, and 100% specificity for lung cancer diagnosis, and 73.5% accuracy for lung cancer subtyping for the training set of tissues, per-patient. On the validation set of tissues, 100% accuracy for lung cancer diagnosis and 94.1% accuracy for lung cancer subtyping were achieved. When tested on the FNA samples, 100% diagnostic accuracy and 87.5% accuracy on subtyping were achieved per-slide.

Conclusions

DESI-MSI can be useful as an ancillary technique to conventional cytopathology for diagnosis and subtyping of non-small cell lung cancers.

Keywords: lung, subtypes, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, desorption electrospray ionization, imaging, mass spectrometry

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer with over 100 000 cases diagnosed each year (1). Within its various types, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of all lung cancers affecting both nonsmokers and smokers (2). Despite improvements in early cancer detection (3), the majority of patients with lung cancer are diagnosed at advanced stages of the disease when surgical resection is no longer curative (4, 5). Thus, management of patients with lung cancer is often focused on increasing life expectancy while maintaining quality of life, most commonly through targeted therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy treatment regimens. For NSCLC, targeted therapy that counteract altered biochemical pathways unique to each subtype, such as adenocarcinoma (ADC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), have been increasingly explored as more efficient treatment options for patients with advanced lung cancer. Concomitantly, targeted drug treatments have made lung cancer subtyping even more crucial to properly select the drug and thus improve efficacy and patient safety (4–6). In routine clinical practice, lung cancer diagnosis and subtyping are commonly performed by image guided biopsy procedures including core needle biopsy and/or fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy. FNA is minimally invasive and is used to investigate lung lesions that are suspected to be malignant, based on imaging findings. The aspirated material is smeared on glass slides and stained for conventional cytopathological examination, or used for ancillary immunohistochemical testing. Yet, FNA diagnosis can be inconclusive in up to 30% of lung FNA biopsies due to insufficient material and/or overlap between cytological features of lung cancer subtypes, which complicates diagnosis (4, 7–9). Furthermore, the results from biopsy histologic staining and immunohistochemistry can be subjective, and take several days to a week to yield a final diagnosis.

New molecular techniques capable of providing rapid and accurate diagnosis and subtyping of lung cancer from biopsy material could potentially improve management of patients with lung cancer. In the past decade, substantial strides have been made to optimize the use of lung FNAs for molecular testing using various technologies, including next generation sequencing (10), mutational analysis (11), fluorescence in situ hybridization (12), and Raman spectroscopy (13–15). For example, lung FNA smears can be triaged for tumor cell macro- or microdissection, nucleic acid isolation, and subsequent molecular testing [e.g., epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Kirsten rat sarcoma mutation analysis] in order to diagnose lung cancer subtype and prescribe appropriate treatment. Mass spectrometry (MS) imaging techniques have been increasingly explored for cancer diagnosis because they enable direct and untargeted analysis of tissues with high chemical specificity and analytical sensitivity (16, 17). Several research groups have explored the use of MS imaging for lung cancer tissue diagnosis (18–23). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)-MS imaging has been used to analyze the protein profiles of human lung ADC and SCC tissue sections (n = 162), enabling discrimination between subtypes using statistical analysis with an area under the curve value of 0.885 in a validation set (19). More recently, MALDI imaging was used to analyze mock FNA samples and 5 clinical FNA samples (23). Air flow-assisted desorption electrospray ionization-MS imaging has been used to distinguish normal and lung cancerous tissue, ADC and SCC subtypes, as well as EGFR-positive and wild-type ADC tissues (21, 22). Data acquired from a total of 55 human cancer and adjacent normal tissue sections enabled identification of ADC and SCC subtypes with 85.2% and 82.1% accuracies, respectively, using cross validation in a training set (22). While these results are promising, there has been limited effort evaluating the performance of MS imaging methods in clinical FNA samples. Several groups have explored the use of desorption electrospray ionization (DESI)-MS and MALDI-MS for cancer diagnosis from tissue sections and FNA smears (23, 24–32). Here, we explored the usefulness of DESI-MS imaging (DESI-MSI) and statistical classification to diagnose and subtype (ADC and SCC) lung cancer tissue sections (n = 73) and FNA biopsies (n = 16).

Materials and Methods

Tissue Samples

Banked frozen human tissue samples, including 51 normal human lung, 40 ADC, and 40 SCC, were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network and MD Anderson Cancer Center under approved Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol. Normal lung specimens consist exclusively of healthy lung tissues; other benign lung tissues such as tissues diagnosed with pneumonia or other noncancerous diseases were not included in our study. Patient demographics are presented in online Supplemental Table 1. Samples were stored in a -80 °C freezer. Tissue samples were sectioned at 16 µm using a CryoStar NX50 cryostat (Thermo Scientific) and thaw mounted onto semi-frost glass slides. After sectioning, the glass slides were stored in a -80 °C freezer. Prior to MS imaging, the glass slides were thawed for about 10 min. Tissue sections were stained according to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) procedure described in the online Supplemental Information. A total of 73 tissue samples (22 normal lung, 25 ADC, and 26 SCC) were used in the training and validation sets.

DESI-MS Imaging

A 2 D Omni Spray stage (Prosolia Inc.) with a laboratory-built sprayer was used for tissue imaging with a spatial resolution of 200 µm. DESI-MSI was performed in the negative ion mode from m/z 100-1500 with 60,000 resolving power using a LTQ-Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The histologically compatible solvent system dimethylformamide: acetonitrile (1:1) was used at 1.2 µL/min. Analysis speed was ∼1 sec/pixel or mass spectra, ∼ 20–50 min per tissue section, and ∼2 - 5 h per FNA smear. The data obtained are available on Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/37BAUU). Identification of the ions was performed as described in the online Supplemental Methods. Tandem mass spectra of selected glycerophospholipid species detected are provided in online Supplemental Fig. 1.

Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy Collection and Preparation

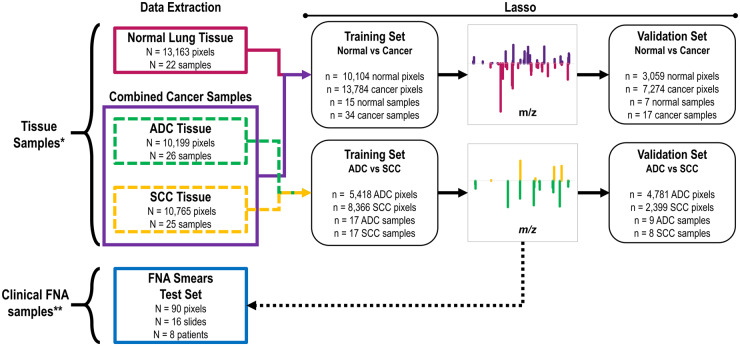

Clinical FNA biopsies were obtained from 19 patients at MD Anderson Cancer Center under an approved IRB protocol. The FNA smears were stored at -80 °C and thawed for 5 min in ambient temperature prior to MS analysis. A total of 16 FNA slides were used in the test set. Detailed information on the FNA samples and patients is provided in Fig. 1, the online Supplemental Information, and Supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of data extraction and lasso classifier workflow. *131 tissue banked samples were obtained for our study, but 58 were excluded for low tissue quality of normal, ADC, and SCC as determined by pathological evaluation. Samples with benign diagnoses, such as pneumonia, were also considered low tissue quality and excluded from the data set. 73 were used for method development as shown here. **70 FNAs were collected, yet 54 were excluded as explained in the main text, and 16 were used to test the method developed as shown here.

Statistical Analysis

Detailed information about raw data preprocessing and statistical classifiers is provided in Fig. 1 and the online Supplemental Information. Sample list of training and validation sets are provided in online Supplemental Tables 4 and 5. Classifier performance was evaluated per-pixel (diagnosis for each mass spectrum/pixel), per-patient (overall diagnosis based on majority rule, more than 50% of the pixels in the sample), and per-slide (classification of the majority of pixels in a slide as the overall classification for the slide) in comparison to final pathological diagnosis.

Results

DESI-MS Imaging of Lung Tissues in the Negative Ion Mode

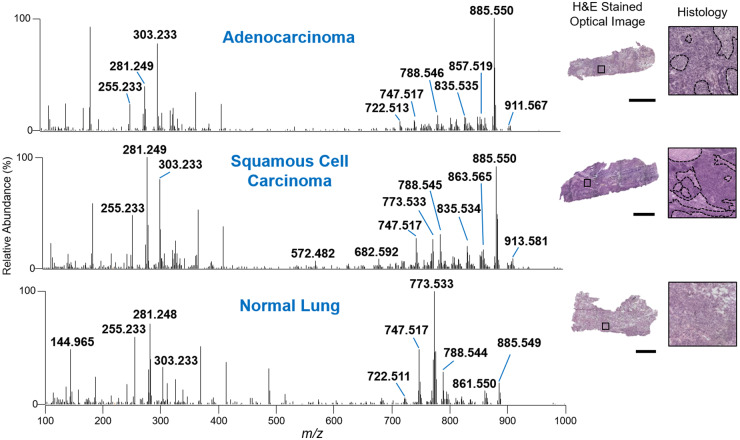

We first performed DESI-MSI imaging on 131 lung tissue sections to acquire mass spectra of each tissue type. After pathological evaluation of tissue quality, a total of 73 lung samples, including 22 normal lung, 26 ADC, and 25 SCC samples were used to build the training and validation set, yielding a total of 34,127 mass spectra (Fig. 1). The mass spectra obtained in negative ion mode presented high relative abundances of glycerophospholipid species, such asglycerophosphoglycerols (PG), glycerophosphoinositols (PI), glycerophosphoserines (PS), glycerophosphoethanolamines (PE), and fatty acids (FA), which is typical from DESI-MSI experiments. Figure 2 shows averaged DESI mass spectra (n = 3 pixels) obtained from samples of each tissue type. Normal lung tissue mass spectra presented a molecular profile with high relative abundance of m/z 773.533, m/z 747.560, and m/z 303.233, identified as PG (36:2), PG (34:1), and FA (20:4), respectively. On the other hand, molecules such as PI (38:4) at m/z 885.550, PI (34:1) at m/z 835.534, and PS (36:1) at m/z 788.544 were detected at higher relative abundances in lung cancer tissue mass spectra when compared to normal lung tissue. While differences in the mass spectral profiles of normal and cancerous tissues could be qualitatively observed by visual inspection (Fig. 2), differences in ADC and SCC mass spectra were less prominent, requiring statistical analysis for discrimination.

Fig. 2.

Negative ion mode DESI mass spectra of ADC, SCC, and normal lung tissue. Each mass spectrum is an average of 3 scans. Optical images of corresponding ADC, SCC, and normal lung tissue sections that were H&E stained after DESI-MS imaging. Black dashed lines delineate regions of necrosis or normal stroma in isolated histology areas. Surrounding dark purple stained areas delineate regions of concentrated ADC or SCC, respectively. Scale bars = 2 mm.

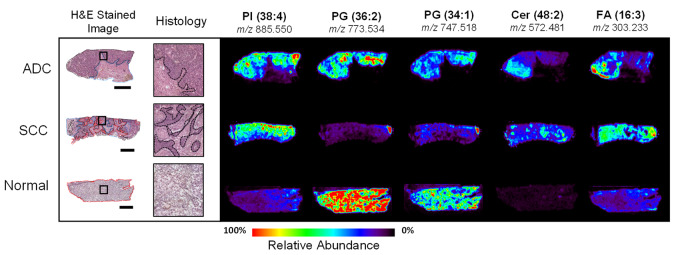

Figure 3 shows ion images and spatial distribution of the selected ions throughout each tissue section presented, as well as an optical image of the H&E stained tissue section. Histopathologic evaluation of the stained tissue sections after DESI-MSI revealed that heterogeneity in ion distributions corresponded to tissue regions with different histologic composition, which are delineated in the optical images presented in Fig. 3. A description of histological features found in tissue sections is provided in the online Supplemental Information. The images obtained of several ions such as m/z 747.518 and m/z 885.550 allowed visualization of the histologic heterogeneity within normal and cancerous tissue sections. In normal lung tissue, ions at m/z 773.534 and m/z 747.518 were observed at a high relative abundance throughout the entire tissue sample, while lower relative abundance of these ions were seen in cancer and necrotic tissue regions. For example, visualization of a small region of normal lung in the right top corner of the SCC lung tissue shown in Fig. 3 can be visualized in the ion image of m/z 773.534 and m/z 747.518. On the other hand, m/z 885.550 was observed in high relative abundance in cancerous tissue regions, in both ADC and SCC tissue sections. Other examples of ions observed at high relative intensities within regions of ADC and SCC tissues regions include m/z 835.534 identified as PI (34:1), m/z 863.565 identified as PI (36:1), and m/z 303.233 identified as FA (20:4). The mass spectra acquired from necrotic tissues presented overall low abundance of molecular species, except for Cer species such as m/z 572.480 identified as Cer (d34:1), and m/z 682.590 identified as Cer (d42:2), which can be seen in the ion images presented in Fig. 3. Relevant normal, ADC, and SCC tissue regions demarcated by pathology were used to isolate mass spectra from surrounding stroma and necrosis and extract data for statistical analysis.

Fig. 3.

Optical microscopy images of three H&E stained lung tissue sections with corresponding DESI-MS ion images. Black dotted lines delineate regions of ADC or SCC. Red dotted lines delineate regions of normal lung cells and/or normal stroma. Blue dotted lines delineate regions of necrosis. Solid black squares indicate regions selected to show enlarged histology. (x: y) indicate the number of carbon atoms: double bonds in each lipid. Scale bar = 4 mm.

Statistical Classification

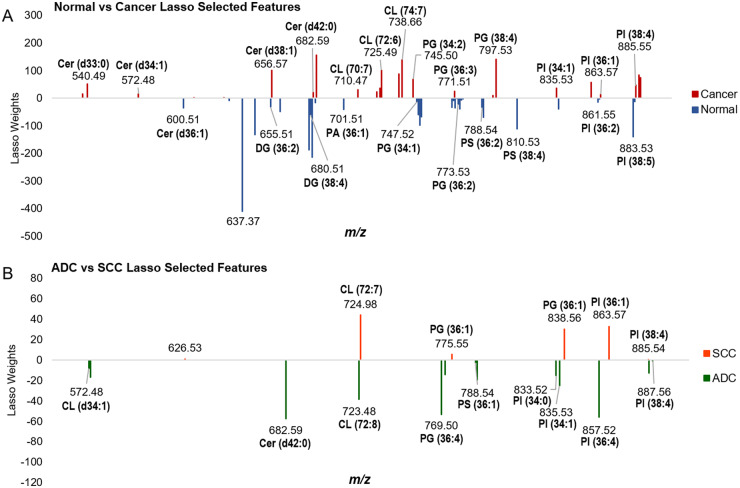

Two statistical models were generated in our study using Lasso logistic regression algorithm: a first model built to differentiate between normal and cancer tissues, and a second model built to subtype tissue classified as cancer as ADC versus SCC, represented in Fig. 1(33). The Lasso selects a sparse subset of m/z values with assigned mathematical weight as a model that is predictive of tissue type using the training set of data (34). Figure 4 shows plots of the m/z features selected by the Lasso for each model and their corresponding weights, as well as tentative identifications for a subset of the features. The normal versus lung cancer statistical model was based on 59 features, while 19 features were selected in the ADC versus SCC model. A summary of these features can be found in Supplemental Tables 6 and 7. A description of the significance of Lasso weights and a discussion regarding biological significance of the species selected are provided in the Supplemental Information. Note that while distinguishing normal from cancerous lung cells was routinely accomplished using histopathology, including this initial diagnosis step in our analysis was important for method development and necessary to identify relevant cancerous pixels for consecutive subtype differentiation.

Fig. 4.

Features selected by the Lasso models built from DESI-MS imaging data to differentiate (A) normal lung from cancerous lung tissue and (B) ADC from SCC lung cancer subtypes, respectively. Larger weights indicate significance of each feature for respective tissue types.

To evaluate performance of the classifiers, predictive accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value were calculated for the training and validation sets of samples, both per-pixel and per-patient (Table 1). On a per-patient basis, the normal versus cancer statistical classifier yielded 100% accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for both the training and validation sets. For the ADC versus SCC statistical classifier, 73.5% of patients were correctly classified, within which 76.5% of patients with ADC were correctly classified with 72.2% ADC recall, and 70.6% of patients with SCC were correctly classified with 75.0% SCC recall in the training set. On the validation set, high performance was achieved per-patient, with an overall accuracy of 94.1%, ADC recall of 88.9%, and 100% SCC recall. Collectively for the subtype classifier, 9 samples were misclassified in the training set, while 1 sample was misclassified in the test set.

Table 1.

Sequential classifiers performance metrics on tissue sections of normal, adenocarcinoma (ACC), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) tissues and accuracy values for validation set of fine needle aspirate biopsies per-pixel, per-slide, and per-patient.

| Tissue samples |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal vs cancer |

Normal vs cancer |

||||||

| Per-pixel | Per-patient | ||||||

|

Training set (n = 10 104 normal, 13 784 cancer) |

Test set (n = 3059 normal, 7274 cancer |

Training set (n = 15 normal, 34 cancer) |

Test set (n = 7 normal, 17 cancer) |

||||

| Sensitivity (%) | 98.2 | 98.7 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Specificity (%) | 99.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Accuracy (%) | 98.6 | 99.1 | 100 | 100 | |||

| ADC vs SCC | ADC vs SCC | ||||||

| Per-Pixel | Per-Patient | ||||||

|

Training Set (n = 5418 ADC, 8366 SCC) |

Test Set (n = 4781 ADC, 2399 SCC) |

Training Set (n = 17 ADC, 17 SCC) |

Test Set (n = 9 ADC, 8 SCC) |

||||

| ADC accuracy (%) | 72.6 | 68.6 | 76.5 | 88.9 | |||

| SCC accuracy (%) | 72.5 | 81.3 | 70.6 | 100 | |||

| Overall accuracy (%) | 72.5 | 72.8 | 73.5 | 94.1 | |||

| Fine Needle Aspirate Test Set | |||||||

|

Per-Pixel (n = 76 ADC, 14 SCC) |

Per-Slide (n = 14 ADC, 2 SCC) |

Per-Patient (n = 7 ADC, 1 SCC) |

|||||

| ADC accuracy (%) | 78.9 | 85.7 | 85.7 | ||||

| SCC accuracy (%) | 71.4 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Overall accuracy (%) | 77.8 | 87.5 | 87.5 | ||||

Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy Classification

We next tested the performance of the statistical classifiers built using tissues on 16 FNA slides collected from 8 lung cancer patients as an independent test set of samples. Among the 16 slides, 14 slides contained ADC cells and 2 slides contained SCC cells, per pathologic evaluation. Figure 5 shows averaged mass spectra (n = 3 pixels) extracted from regions containing ADC and SCC lung cells within FNA biopsies with optical images of H&E stained slide, corresponding ion images, and zoom in region to visualize detailed histology. Generally, the mass spectra profile of FNA material were qualitatively similar to that of tissue sections in terms of the relative abundances of fatty acids and lipid species. Specifically, m/z 885.549, m/z 861.549, and m/z 788.545 were observed in high relative abundances in the mass spectra obtained from cancerous cells of FNA samples, as observed in the lung cancer tissue section mass spectra (Fig. 2). An overall decrease in the relative abundance of complex lipids within m/z 500–900 when compared to FA within m/z 100 and 400 was observed in the mass spectra from FNA samples when compared to tissue sections. Further, lower total ion abundance per mass spectra was also observed in the FNA data, which can be attributed to the low cellularity of FNA samples when compared to tissues.

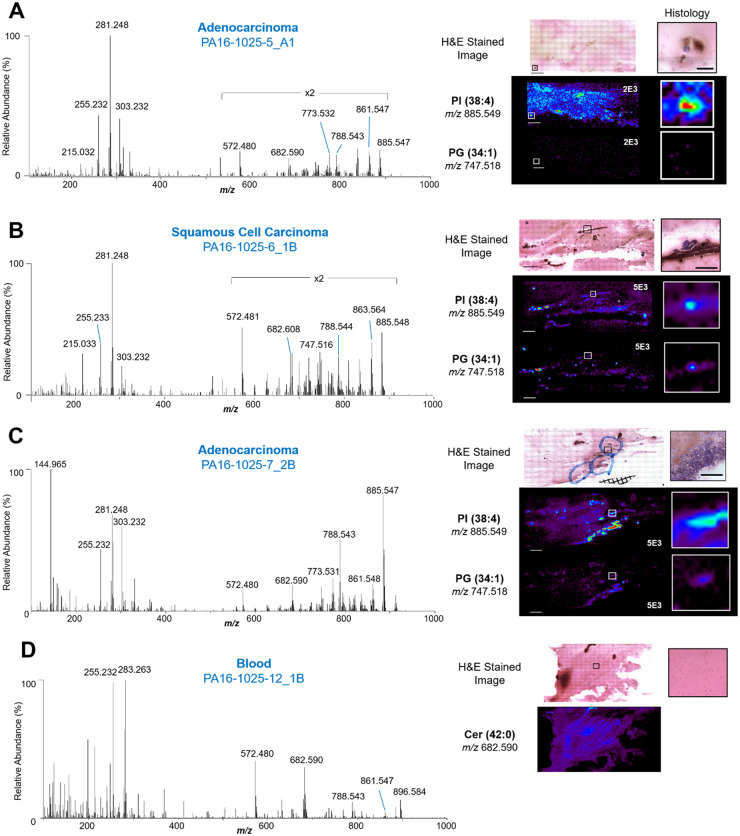

Fig. 5.

Mass spectra, ion images, and optical images of H&E stained clinical FNA samples. (A) Selected negative ion mode mass spectrum of ADC cells from an FNA sample with its corresponding optical microcopy image, enlarged histology, and ion images. Each mass spectrum was averaged across 3 scans. (B) Selected negative ion mode mass spectrum of SCC cells from an FNA sample with its corresponding optical microcopy image, enlarged histology, and ion images. (C) Selected negative ion mode mass spectrum of ADC cells from an FNA sample of high cell density, with its corresponding optical microcopy image, enlarged histology, and ion images. (D) Selected negative ion mode mass spectrum of interfering blood within an FNA sample, with its corresponding optical microscopy image, enlarged histology, and ion image of a ceramide lipid. Solid black lines within the H&E stained image indicate regions from which the enlarged histology images were selected. Solid white lines correlate to enlarged ion image of indicated ions. Mass spectrum is an average of 3 scans. White numbers on ion images represent normalized relative abundance scale for each image. Scale bar in H&E image = 4 mm. Scale bar in histology = 500 µm.

After pathological evaluation, data extraction was performed yielding a total of 90 pixels or mass spectra from regions with cellular content. A varying number of cells were observed within each pixel, ranging between ∼20 cells to hundreds cells/pixel. For example, 6 pixels were extracted from FNA sample 6_1B from a patient diagnosed with SCC, and each pixel had ∼50 cancer cells (Fig. 5B). The remaining areas of the slide was mostly comprised of blood (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, FNA sample 7_2B had 11 pixels with high cellular density (>30 cells/pixel) (Fig. 5C). Within the 90 pixels obtained from all samples, 76 were extracted from cells diagnosed by pathology as ADC, and 14 were extracted from cells diagnosed as SCC. For information on the specific number of pixels extracted per each FNA sample and their pathologic diagnosis, please see Supplemental Table 3.

We then applied the Lasso models on the extracted FNA data, and the results are reported per-pixel, per-slide, and per-patient in Table 1. First, the cancer versus normal classifier was applied, yielding 96.7% accuracy per-pixel and 100% accuracy per-sample, meaning that all slides were correctly classified as lung cancer. Considering 100% accuracy in diagnosis, we next applied the lung cancer subtyping classifier to all FNA data, yielding 84.6% overall accuracy, 81.8% ADC accuracy, 100% SCC accuracy, 100% ADC recall, and 66.7% SCC recall per-slide. On a per-patient basis, the performance metrics are similar to the per-slide metrics with 87.5% overall accuracy, 85.6% ADC accuracy with 100% ADC recall, and 100% SCC accuracy with 50% SCC recall.

Discussion

Performance of Statistical Classifiers on Tissue Sections

The normal versus cancer classifier yielded high accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity compared to pathological evaluation of tissue sections, both per-pixel and per-sample. While the critical clinical challenge is differentiating ADC and SCC in FNA biopsies, generation of a normal versus cancer classifier was necessary to first differentiate mass spectra from normal bronchial epithelial cells, alveolar cells, and alveolar macrophages that may present in FNA biopsies, prior to lung cancer subtyping. The lung cancer subtyping classifier performed well when differentiating ADC and SCC mass spectra from tissue sections, with overall accuracy of 94.1%, ADC accuracy of 88.9%, and SCC accuracy of 100% per-sample in the validation set (n = 17). Note that the performance achieved is similar to those reported for tissues in other MS studies (18, 19). Marien et al., for example, reported area under the curve of 0.885 for ADC versus SCC discrimination using protein information acquired with MALDI-FTICR MS imaging, with a larger test set of 178 samples (19). Lee et al. reported training set accuracy of 85.7% and validation set accuracy of 80.4% when discriminating ADC versus SCC in a validation set of 51 cancer tissues (18). In the study by Zhang et al., data acquired by AFA-DESI MS imaging enabled differentiation between ADC and SCC with 82.7% overall accuracy, 85.2% ADC accuracy, and 82.1% SCC accuracy in a training set of 55 cancer tissues (22). In our study, the performance could potentially be improved by increasing sample size, and including patients with varying cancer grade, stage, and invasion status. Further, inclusion of benign lung tissues presenting common nonmalignant conditions such as pneumonia will be pursued to incorporate a wider range of clinical samples into the normal versus cancer statistical classifier.

Performance on Clinical FNA Biopsies

To evaluate the potential clinical usefulness of DES-MSI in lung cancer FNA diagnosis and subtyping, we analyzed FNA samples smeared across an entire glass slide, resulting in varying number and distribution of cell clusters. Some FNA biopsies contained thousands of lung cancer cells, while some contained none. As expected, blood and other “interfering” cell types such as inflammatory cells and alveolar macrophages were also observed in the clinical FNA samples. The mass spectra from blood presented low lipid signals and did not interfere with the mass spectra collected from the lung cancer cell clusters (Fig. 5C). An advantage of our proposed approach is that DESI-MSI provides spatially accurate molecular information, allowing selection of mass spectral data from lung cancer cell clusters and exclusion of mass spectra obtained from pixels containing interfering background. In addition, the histologically compatible nature of the DESI-MSI workflow employed here allowed H&E staining of the FNA after MS analysis (35), and thus unambigious correlation and matching between molecular and histologic information.

Overall, 100% accuracy in the diagnosis of lung cancer and 87.5% accuracy on lung cancer subtyping was achieved per-slide on the independent set of 16 clinical FNA samples, with 2 of the 16 FNA slides incorrectly subtyped by our classifier compared to pathological diagnosis (further discussed in the Supplemental Information). Note that within the FNA samples correctly subtyped by our classifier, sample 13 was from a patient with an inconclusive FNA diagnosis by cytopathology. Final diagnosis as adenocarcinoma was obtained through a core needle biopsy. Notably, the FNA from this patient was correctly diagnosed as cancer and correctly subtyped as adenocarcinoma by our method, enabling diagnosis from an otherwise suboptimal FNA sample. This case showcases the value of our approach in potentially precluding more invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the preliminary results obtained here show that the ADC versus SCC statistical classifier performed similarly on the training, validation, and independent FNA test set, providing evidence that the classifier is robust and is not overfit to the training dataset. When compared to histopathology performance on FNA lung cancer subtyping, which has been reported to be inconclusive in ∼30% of FNA biopsies, (4, 7–9) the performance of DESI-MSI is promising, with 87.5% overall accuracy in distinguishing between ADC and SCC lung cancer subtypes in FNA slides. Other technologies that have been implemented in the clinic for lung cancer subtyping include EGFR point mutations, which are present in 58% of FNA smears, and next-generation sequencing, which has been shown to provide 100% accordance with point mutational analyses, as well as detect mutations in an additional 61% of FNA smears (10, 11). Based on our results, DESI-MSI could be used a complementary technique to current clinical technologies to aid in diagnosis and subtyping of FNA smears. Nevertheless, larger cohorts of FNA samples are needed to properly validate the performance of DESI-MSI and statistical classifiers in comparison to current clinical methods. To increase performance on FNA biopsies, there is a need to expand the statistical classifiers and continue clinical validation. Future studies should also include small cell lung cancer and neuroendocrine tumors of the lung to expand the repertoire of primary lung carcinomas. Additionally, common metastatic carcinomas to the lung, such as breast cancer and melanoma, and other lung pathologies such as pneumonia should be included in our classifier to enhance the robustness and clinical utility.

In conclusion, we developed a method based on metabolic information acquired using DESI-MS imaging and statistical classifiers to diagnose and subtype lung cancer and tested its performance on clinical FNA biopsies. DESI combines the advantages of MS imaging and ambient ionization MS that could be valuable in the clinical setting for direct FNA analysis, with a throughput of 1 sec/pixel and ∼2-5 h/FNA, depending on sample size. To expedite FNA analysis time, methods to reduce the FNA smearing area, as well as cytospin preparation protocols are appropriate for future studies. Importantly, the chemical sensitivity achieved in the imaging mode make this platform a powerful tool to analyze FNA biopsy material with dispersed cellular components. Combining advanced machine learning techniques with multidimensional images generated with DESI-MSI, specific regions of the heterogeneous FNA samples with relevant cellular components can be classified for diagnosis and subtyping. Further, the minimal sample preparation requirements and the nondestructive nature of DESI-MSI analysis can facilitate clinical integration as an alternative technology for FNA assessment. Collectively, the technical features of DESI-MSI combined with robustness of statistical analysis may be appealing for clinical use, especially in cases of indeterminate and/or ambiguous pathological diagnoses (33).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material is available at Clinical Chemistry online.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Alena V Bensussan, Department of Chemistry, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

John Lin, Department of Chemistry, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Chunxiao Guo, Department of Interventional Radiology, Division of Diagnostic Imaging, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Ruth Katz, Department of Pathology, Division of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Savitri Krishnamurthy, Department of Pathology, Division of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Erik Cressman, Department of Interventional Radiology, Division of Diagnostic Imaging, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Livia S Eberlin, Email: liviase@utexas.edu, Department of Chemistry, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Author Contributions: All authors confirmed they have contributed to the intellectual content of this paper and have met the following 4 requirements: (a) significant contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (b) drafting or revising the article for intellectual content; (c) final approval of the published article; and (d) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the article thus ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the article are appropriately investigated and resolved.

J.Q. Lin, statistical analysis; R. Katz, provision of study material or patients; E. Cressman, provision of study material or patients; L.S. Eberlin, financial support, statistical analysis, administrative support, provision of study material or patients. A.V.Bensussan, data collection and analysis; S. Krishnamurthy, provision of study material or patients.

Authors’ Disclosures or Potential Conflicts of Interest: Upon manuscript submission, all authors completed the author disclosure form. Disclosures and/or potential conflicts of interest:

Employment or Leadership: L.S. Eberlin, MS Pen Technologies, Inc.

Consultant or Advisory Role: None declared.

Stock Ownership: L.S. Eberlin, MS Pen Technologies, Inc.

Honoraria: None declared.

Research Funding: The Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), grant number RP160776. The MD Anderson Tissue Bank and the Cooperative Human Tissue Network, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute, provided tissue samples. A.V. Bensussan, Provost’s Excellence Graduate Fellowship from the University of Texas at Austin.

Expert Testimony: None declared.

Patents: A.V. Bensussan, J. Lin., C. Guo., S. Krishnamurthy., E. Cressman. and L.S. Eberlin. are inventors on a provisional patent application 63/071,773 owned by the Board of Regents of the University of Texas System that relates to methods of fine needle aspiration analysis via mass spectrometry, such as described in this study.

Role of Sponsor: The funding organizations did not play any direct role in the design of the study, review and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript, or final approval of manuscript. The funding organizations played no role in the choice of enrolled patients.

Acknowledgments: This work is dedicated to the memory of Gloria Proctor and Michael Lestik.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.What is lung cancer?: Types of lung cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/what-is.html (Accessed October 2019).

- 3. Shen J, Todd NW, Zhang H, Yu L, Lingxiao X, Mei YP, et al. Plasma microRNAs as potential biomarkers for non-small-cell lung cancer. Lab Invest 2011;91:579–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Travis WD, Rekhtman N, Riley GJ, Geisinger KR, Asamura H, Brambilla E, et al. Pathologic diagnosis of advanced lung cancer based on small biopsies and cytology: a paradigm shift. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:411–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rolfo C, Passiglia F, Ostrowski M, Farracho L, Ondoichova T, Dolcan A, et al. Improvement in lung cancer outcomes with targeted therapies: an update for family physicians. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:124–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Travis WD. Classification of lung cancer. Semin Roentgenol 2011;46:178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thunnissen E, Kerr KM, Herth FJ, Lantuejoul S, Papotti M, Rintoul RC, et al. The challenge of NSCLC diagnosis and predictive analysis on small samples. Practical approach of a working group. Lung Cancer 2012;76:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger K, Yatabe Y, et al. Diagnosis of lung cancer in small biopsies and cytology implications of the 2011 International Association for the study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Classification. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013;137:668–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biancosino C, Kruger M, Vollmer E, Welker L.. Intraoperative fine needle aspirations - diagnosis and typing of lung cancer in small biopsies: challenges and limitations. Diagn Pathol 2016;11:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kanagal-Shamanna R, Portier BP, Singh RR, Routbort MJ, Aldape KD, Handal BA, et al. Next-generation sequencing-based multi-gene mutation profiling of solid tumors using fine needle aspiration samples: promises and challenges for routine clinical diagnostics. Mod Pathol 2014;27:314–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smouse JH, Cibas ES, Janne PA, Joshi VA, Zou KH, Lindeman NI.. EGFR mutations are detected comparably in cytologic and surgical pathology specimens of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer 2009;117:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Savic S, Bubendorf L.. Role of fluorescence in situ hybridization in lung cancer cytology. Acta Cytol 2012;56:611–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bird B, Miljkovic MS, Remiszewski S, Akalin A, Kon M, Diem M.. Infrared spectral histopathology (SHP): a novel diagnostic tool for the accurate classification of lung cancer. Lab Invest 2012;92:1358–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang Z, McWilliams A, Lui H, McLean DI, Lam S, Zeng H.. Near-infrared Raman spectroscopy for optical diagnosis of lung cancer. Int J Cancer 2003;107:1047–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park J, Hwang M, Choi B, Jeong H, Jung JH, Kim HK, et al. Exosome classification by pattern analysis of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy data for lung cancer diagnosis. Anal Chem 2017;89:6695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Hove ERA, Smith DF, Heeren RMA.. A concise review of mass spectrometry imaging. J Chromatogr A 2010;1217:3946–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feider CL, Krieger A, DeHoog RJ, Eberlin LS.. Ambient ionization mass spectrometry: recent developments and applications. Anal Chem 2019;91:4266–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee GK, Lee HS, Park YS, Lee JH, Lee SC, Lee JH, et al. Lipid MALDI profile classifies non-small cell lung cancers according to the histologic type. Lung Cancer 2012;76:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marien E, Meister M, Muley T, Fieuws S, Bordel S, Derua R, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer is characterized by dramatic changes in phospholipid profiles. Int J Cancer 2015;137:1539–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kriegsmann M, Casadonte R, Kriegsmann J, Dienemann H, Schirmacher P, Kobarg JH, et al. Reliable entity subtyping in non-small cell lung cancer by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization imaging mass spectrometry on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. Mol Cell Proteomics 2016;15:3081–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li TG, He JM, Mao XX, Bi Y, Luo ZG, Guo CG, et al. In situ biomarker discovery and label-free molecular histopathological diagnosis of lung cancer by ambient mass spectrometry imaging. Sci Rep 2015;5:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang M, He JM, Li TG, Hu HX, Li XF, Xing H, et al. Accurate classification of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) pathology and mapping of EGFR mutation spatial distribution by ambient mass spectrometry imaging. Front Oncol 2019;9:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amann JM, Chaurand P, Gonzalez A, Mobley JA, Massion PP, Carbone DP, Caprioli RM.. Selective profiling of proteins in lung cancer cells from fine-needle aspirates by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:5142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takats Z, Wiseman JM, Gologan B, Cooks RG.. Mass spectrometry sampling under ambient conditions with desorption electrospray ionization. Science 2004;306:471–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ifa DR, Eberlin LS.. Ambient ionization mass spectrometry for cancer diagnosis and surgical margin evaluation. Clin Chem 2016;62:111–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DeHoog RJ, Zhang JL, Alore E, Lin JQ, Yu WD, Woody S, et al. Preoperative metabolic classification of thyroid nodules using mass spectrometry imaging of fine-needle aspiration biopsies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019;116:21401–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Woolman M, Tata A, Bluemke E, Dara D, Ginsberg HJ, Zarrine-Afsar A.. An assessment of the utility of tissue smears in rapid cancer profiling with desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (DESI-MS). J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2017;28:145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Basu SS, Regan MS, Randall EC, Abdelmoula WM, Clark AR, Gimenez-Cassina Lopez B, et al. Rapid MALDI mass spectrometry imaging for surgical pathology. Npj Precis Oncol 2019;3: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pirro V, Alfaro CM, Jarmusch AK, Hattab EM, Cohen-Gadol AA, Cooks RG.. Intraoperative assessment of tumor margins during glioma resection by desorption electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017;114:6700–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Porcari AM, Zhang JL, Garza KY, Rodrigues-Peres RM, Lin JQ, Young JH, et al. Multicenter study using desorption-electrospray-ionization-mass-spectrometry imaging for breast-cancer diagnosis. Anal Chem 2018;90:11324–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Doria ML, McKenzie JS, Mroz A, Phelps DL, Speller A, Rosini F, et al. Epithelial ovarian carcinoma diagnosis by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Sci Rep 2016;6:39219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Calligaris D, Caragacianu D, Liu X, Norton I, Thompson CJ, Richardson AL, et al. Application of desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging in breast cancer margin analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:15184–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Adamson AS, Welch HG.. Machine learning and the cancer-diagnosis problem - no gold standard. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2285–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc Ser BMethodol 1996;58:267–88. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eberlin LS, Ferreira CR, Dill AL, Ifa DR, Cheng L, Cooks RG.. Nondestructive, histologically compatible tissue imaging by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Chembiochem 2011;12:2129–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.