Abstract

Smart food policy models for improving dietary intake recommend tailoring interventions to people’s food preferences. Yet, despite people citing tastiness as their leading concern when making food choices, healthy food labels overwhelmingly emphasize health attributes (e.g., low caloric content, reductions in fat or sugar) rather than tastiness. Here we compared the effects of this traditional health-focused labeling approach to a taste-focused labeling approach on adults’ selection and enjoyment of healthy foods. Four field studies (total N = 4,273) across several dining settings in northern California in 2016–2017 tested whether changing healthy food labels to emphasize taste and satisfaction rather than nutritional properties would encourage more people to choose them (Studies 1–2), sustain healthy purchases over the long-term (Study 3), and improve both the perceived taste of and mindsets about healthy foods (Study 4). Compared to health-focused labeling, taste-focused labeling increased choice of vegetables (OR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.32, 2.26), salads (OR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.06, 4.06), and vegetable wraps (OR = 3.09, 95% CI: 1.73, 5.65) in Studies 1–2. In Study 3, taste-focused labeling sustained vegetarian entrée purchases over a two-month period, while health-focused labeling led to a 45.1% decrease. In Study 4, taste-focused labeling significantly enhanced post-consumption ratings of vegetable deliciousness and improved mindsets about the deliciousness of healthy foods compared to health-focused labeling. These studies demonstrate that taste-focused labeling is a low-cost strategy that increased healthy food selection by 38% and outperforms health-focused labeling on multiple smart food policy mechanisms.

Keywords: obesity, healthy food, taste, food policy, mindset, food labeling, nutrition, health promotion

INTRODUCTION

Poor dietary intake is a leading risk factor for disease burden worldwide (Lim et al., 2013). While many approaches for improving dietary intake have been tested, including those targeting individuals (e.g., dieting, goal-setting) and the environment (e.g., choice architecture, taxes and subsidies), few reliably shift food choice (Gortmaker et al., 2011; Hawkes et al., 2015; Roberto et al., 2015). Perhaps the most widely researched and implemented intervention over the last decade has been nutritional labeling. Nutritional labeling includes calorie counts, symbols (e.g., checkmark), colors (green, red), and verbal descriptions (e.g., heart-healthy, lighter choice) that emphasize health qualities or nutritional benefits. In a clear victory for public health, nutritional labeling has incentivized restaurants to offer lower-calorie options (Bleich et al., 2017b; Block and Roberto, 2014; Hawkes et al., 2015). However, though a few studies show that labeling calories or nutrients encourages some people to order healthier some of the time (Bleich et al., 2017a; Roberto et al., 2010), multiple meta-analyses show that emphasizing caloric content does not improve people’s food choices (Bleich et al., 2017a; Fernandes et al., 2016; Kiszko et al., 2014; Long et al., 2015). Despite a lack of evidence that health-focused labeling improves ordering behavior, calorie labeling is now mandatory in many locations. A majority of top-selling American restaurants even feature their lowest calorie items in a “healthy” menu and describe these items with health-focused descriptions (e.g., lighter fare, under 600 calories) that emphasize nutritional qualities and health benefits (Turnwald et al., 2017c). It may seem intuitively beneficial to emphasize health attributes so that people can identify healthy choices, but is health-focused labeling of healthy foods capitalizing on the principles of smart food policy?

In their recent synthesis of evidence from behavioral economics, public health, nutrition, and psychology, Hawkes and colleagues (2015) concluded that no efforts to date fully meet the recommendations for “smart food policies,” evidence-based actions that improve dietary intake. Smart food policies should target the interaction between people’s food preferences (whether people like a food and in what quantities they eat it) and the environments in which those preferences are learned, acted upon, and reassessed (Hawkes et al., 2015). To do so, food policies should, first and foremost, be tailored to people’s food preferences. Smart food policies should also work through the following mechanisms: (1) provide an enabling environment for learning healthy food preferences, (2) encourage reassessment of existing unhealthy preferences at the point-of-purchase, (3) overcome barriers (e.g., income, availability) to expression of healthy preferences, and (4) stimulate a food systems response that improves health qualities of foods (Hawkes et al., 2015).

Contrary to smart food policy recommendations, health-focused labeling is not tailored to people’s preferences in the moment of food choice. For decades, taste has been the primary driver of food decisions, prioritized far above healthiness (Aggarwal et al., 2016; Glanz et al., 1998; Lennernäs et al., 1997; Verbeke, 2006). Making matters worse, health-focused labeling works in direct opposition to taste preferences. Many people hold the mindset (conscious or subconscious cognitive association leading to a particular set of expectations)(Crum and Zuckerman, 2017; Crum et al., 2017) that the healthier a food is, the worse it tastes (Raghunathan et al., 2006) and less filling it is (Suher et al., 2016); indeed, lab studies show that people experience foods with health-focused labels as less tasty (Fenko et al., 2016; Lähteenmäki et al., 2010; Raghunathan et al., 2006), less filling (Finkelstein and Fishbach, 2010; Suher et al., 2016), and less appealing (Fenko et al., 2016; Lähteenmäki et al., 2010). Emphasizing health characteristics of food is even associated with decreased physiological satiety (Crum et al., 2011) and less rewarding neural responses (Grabenhorst et al., 2013; Veldhuizen et al., 2013). These negative experiences and negative mindsets suggest that emphasizing only nutritional qualities makes people less likely to learn preferences for healthy foods and reassess unhealthy preferences at the point-of-purchase, not more. By failing to associate healthy foods with proximal rewards of taste and satisfaction, health-focused labeling also relies on people to exert restriction and self-control to make healthy choices (Giuliani et al., 2013; Metcalfe and Mischel, 1999), a challenging and often unsuccessful strategy in the moment of food choice (Hofmann et al., 2010; Mann et al., 2015; Mann et al., 2007), particularly for individuals trying to control their weight (Hofmann et al., 2010; Mann et al., 2015; Mann et al., 2007). How then should healthy foods be labeled to encourage people to choose them? The present studies examine a novel labeling strategy for healthy foods: taste-focused labeling.

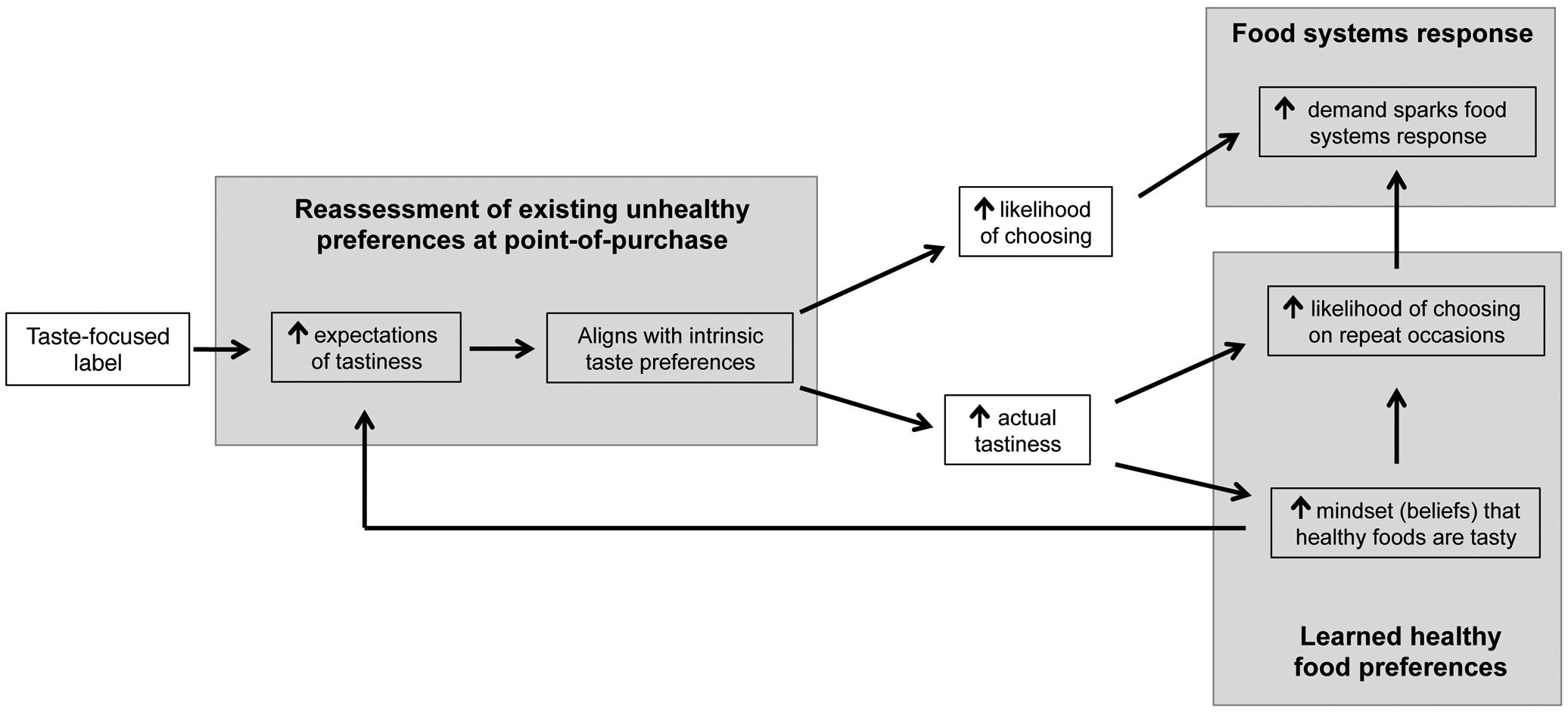

Taste-focused labeling associates healthy foods with tastiness, people’s primary preference when choosing what to eat (Aggarwal et al., 2016; Glanz et al., 1998; Lennernäs et al., 1997). Figure 1 outlines a testable model for taste-focused labeling in the context of smart food policy. By promoting healthy foods on proximal rewards of taste, satisfaction, and pleasure, taste-focused labeling has the potential to enhance the expected taste (Liem et al., 2012) and the actual experienced taste (Raghunathan et al., 2006) of healthy foods, making consumption on repeated occasions more likely. By enhancing the perceived tastiness of foods, taste-focused labeling of healthy foods could encourage reassessment of existing unhealthy preferences and stimulate an environment for learning healthy food preferences, two of the major mechanisms through which smart food policies should function (Hawkes et al., 2015). Taste-focused labeling does not trick people into thinking that healthy foods are unhealthy; rather it shifts attention to the tasty, indulgent, and rewarding properties of healthy foods. In so doing, taste-focused labeling challenges the typical construal of healthy foods as bland and unsatisfying, and has the potential to replace it with a mindset that healthy foods can be delicious. This mindset shift has the potential to transfer across environments by changing the way an individual construes healthy foods in general (Crum and Zuckerman, 2017; Crum et al., 2011), a benefit over choice architecture approaches that capitalize on mindless decisions and defaults (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008; Walton and Wilson, 2018).

Fig 1. Proposed mechanism for taste-focused labeling as a smart food policy.

Gray boxes represent three of the major mechanistic pathways (bolded text) through which smart food policies affect dietary intake.

Here we argue that the beneficial effects of taste-focused labeling should be harnessed for healthy foods. While most work to date consists of lab studies that investigated the effects of taste-focused and health-focused labels on snack, ambiguous, or unhealthy foods (e.g., cookies, crackers, milkshakes, soups, popcorn), one large field study reported increased intake of vegetables when labeled as taste-focused instead of as health-focused. This provides preliminary evidence that taste-focused labeling may be a promising approach for promoting healthy foods in real-world settings (Turnwald et al., 2017a). In this article we describe four studies (total N = 4,273) that compare the efficacy of taste-focused labeling to health-focused labeling, using smart food policy guidelines to examine why taste-focused labeling increases healthy food choices in field settings.

Studies 1 and 2 tested whether labeling healthy foods as tasty (versus healthy) led more people to choose them in isolation and in competition with other desirable foods. To test the long-term effects of taste-focused labeling, Study 3 tested the cumulative impact of repeated exposure to taste-focused versus health-focused labeling on purchasing of vegetarian entrées over a two-month period. Finally, Study 4 tested whether taste-focused labels enhance the experienced tastiness of healthy foods and improve the mindset that healthy foods can be tasty. All taste-focused descriptions were constructed from a large database of appealing words, collated from previous work (Turnwald et al., 2017c) that categorized thousands of restaurant menu descriptions of enticing foods. All studies were approved by the Stanford University IRB.

STUDY 1

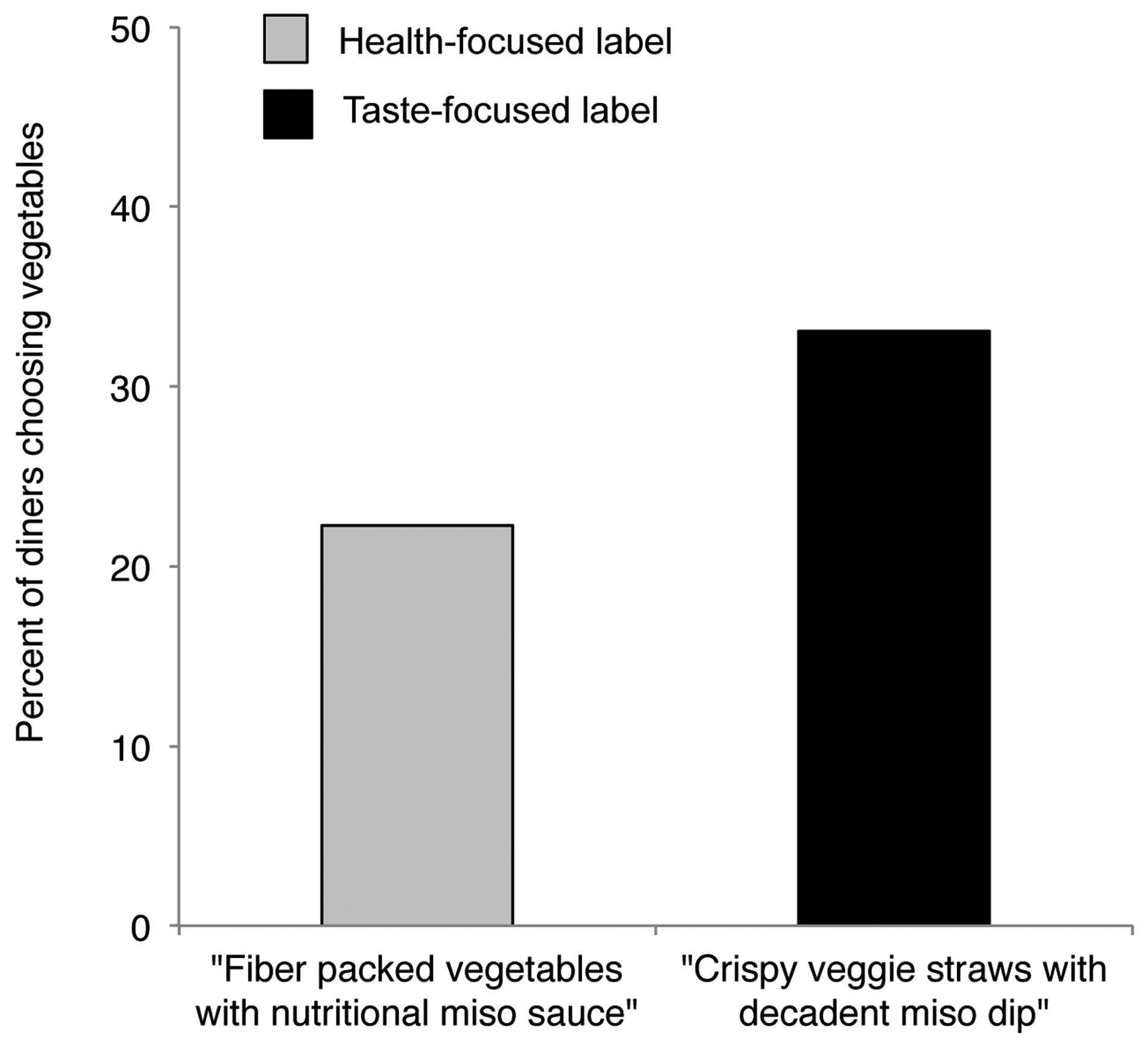

Study 1 was run at a tasting table in a university cafeteria, serving 52.5% undergraduate students, 32.5% graduate students, and 15.1% staff/other. Sex demographics from all studies are displayed in Table S1. On each of two test days, two cafeteria staff members prompted each diner (total N = 1,116) upon entry to try a serving of mixed vegetables (carrots, jicama, and green beans) with miso dipping sauce. One day the vegetables were labeled with a health-focused description (“Fiber-packed vegetables with nutritious miso sauce”) and verbally described as “healthy,” “nutritious,” and “good for you” by staff members. On the other day the same dish was labeled as tasty (“Crispy veggie straws with decadent miso dip”), and described as “delicious” and “tasty.” Results of a logistic regression revealed that significantly more people selected the vegetables when they were labeled as tasty (33.11%) than as healthy (22.27%) (odds ratio (OR) = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.32, 2.26; Figure 2, Table S2). This represents a 48.7% increase in the amount of people choosing vegetables with taste-focused labels compared to health-focused labels. To check the robustness of these findings, Studies 2–4 tested whether taste-focused labeling enticed more people to choose healthy foods than health-focused labeling, in the absence of social interaction or additional prompting besides the label alone.

Fig 2. Food choice by label condition in Study 1.

Bars represent the percentage of diners (total N = 1,116) selecting the vegetables with health-focused and taste-focused labels in Study 1, conducted in northern California in 2016.

STUDY 2

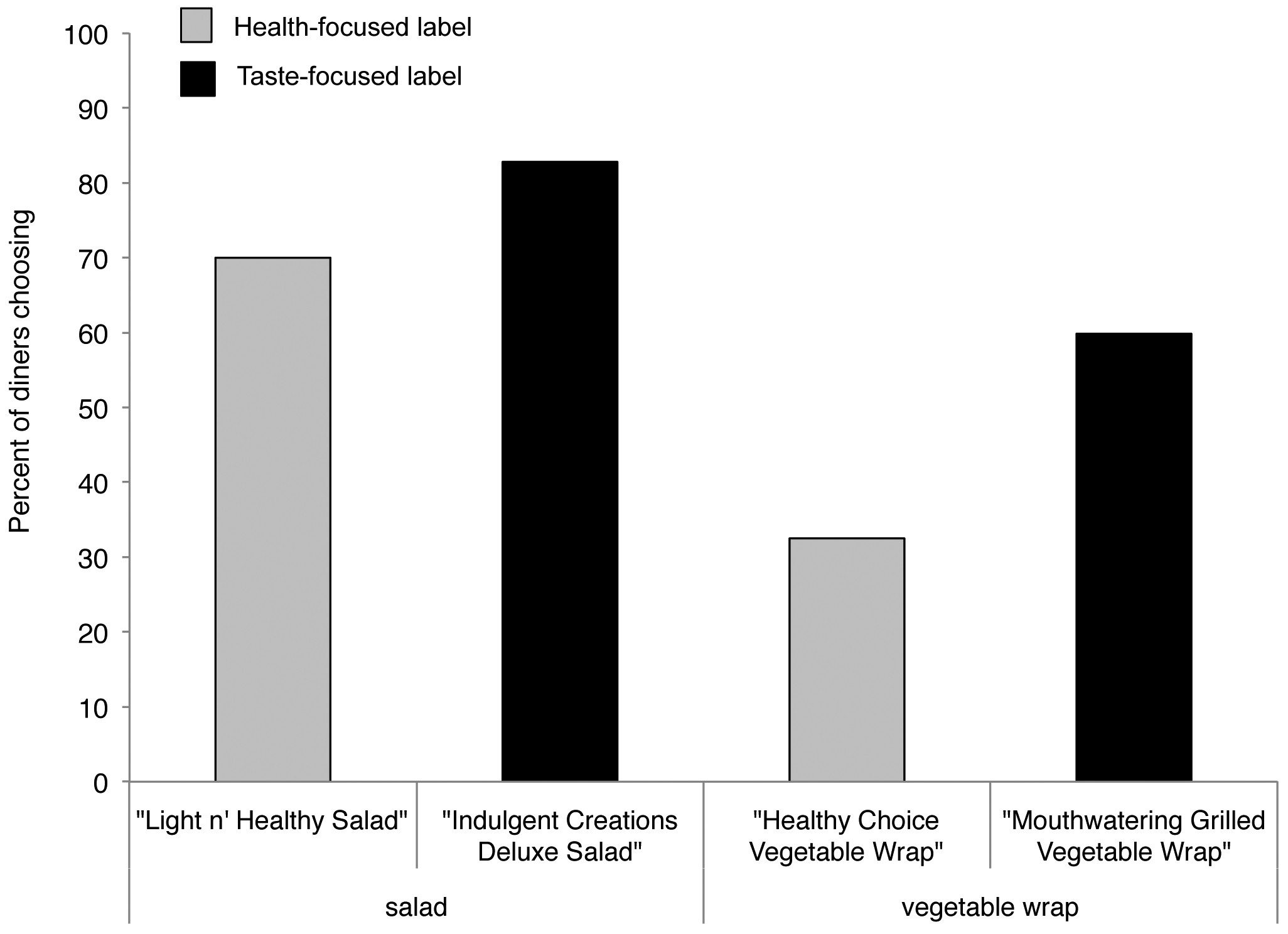

Study 2 was run at a conference lunch buffet. Diners had their choice of salad, quinoa, vegetable wrap, turkey or steak sandwich, and dessert. Two buffet lines serving N = 202 people were discretely observed by research assistants. On one buffet line, the salad and vegetable wrap were given health-focused labels (“Light n’ Healthy Salad” and “Healthy Choice Vegetable Wrap”), and on the other line they were given taste-focused labels (“Indulgent Creations Deluxe Salad” and “Mouthwatering Grilled Vegetable Wrap”). Other items were given the same, non-descriptive labels on both lines, and labels were not visible to diners before selecting a buffet line. Results of a logistic regression revealed that significantly more diners chose salad (82.79% vs. 70.00%; OR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.06, 4.06) and vegetable wraps (59.84% vs. 32.50%; OR = 3.09, 95% CI: 1.73, 5.65) labeled as tasty than as healthy (Figure 3, Table S3). This represented an 18.3% increase and an 84.1% increase, respectively, in the amount of people choosing salads and vegetable wraps when labeled as tasty versus healthy.

Fig 3. Food choice by label condition in Study 2.

Bars represent the percentage of diners (total N = 202) selecting salads and vegetable wraps with health-focused and taste-focused labels in Study 2, conducted in northern California in 2017.

Together, Studies 1 and 2 demonstrate that taste-focused labeling enhances adults’ selection of a variety of healthy foods. However, without long-term observations, we do not know whether taste-focused labeling provides a better environment for learning healthy food preferences over time. Additionally, we do not know whether consuming healthy foods when labeled as tasty alters the experienced taste of or mindsets about healthy foods. Studies 3 and 4 addressed these questions.

STUDY 3

Study 3 examined the long-term effects of taste-focused versus health-focused labeling on sustained consumption of vegetarian entrees in competition with meat entrees. Though not all vegetarian foods are healthy (e.g., processed snacks), vegetarian entrees were considered to be a healthier choice than meat entrees in this study because they were wholesome entrees that substituted vegetables, tofu, or gardein (see Table S4 for all entrees). Epidemiological studies show that vegetarian diets are healthier than diets high in meat: increased meat consumption is associated with increased rates of cardiovascular disease (Singh et al., 2003), cancer (Singh et al., 2003), and mortality (Larsson and Orsini, 2013; Singh et al., 2003), while vegetarian diets are associated with decreased rates of cardiovascular disease (Le and Sabaté, 2014), cancer (Huang et al., 2012; Le and Sabaté, 2014), and mortality (Huang et al., 2012; Le and Sabaté, 2014).

The study was conducted at a pay-by-weight café, serving N = 72.4 (SD = 17.9) diners per hour at lunch during each weekday over a two-month period. Days were randomly assigned to a health-focused or taste-focused labeling condition. Each day, diners served themselves from a food bar consisting of a meat entrée, vegetarian entrée, and starch or other side, and research assistants discretely recorded diners’ food choices. It was not possible to track individual diners’ food choices over the study period, but dining hall staff and our own observations indicated that most diners frequented the café several times per week throughout the study period.

This study took a labeling approach that pitted meat entrées and vegetarian entrées against one another to highlight the contrast that typically exists between the tasty descriptions of meat and the health-focused descriptions of vegetarian options. In the health-focused labeling condition, vegetarian entrées were described as healthy and meat entrées as tasty, representing traditional labeling approaches. In contrast, in the taste-focused labeling condition, vegetarian entrées were described as tasty and meat entrées as healthy (all labels in Table S4). The primary outcome was whether the percentage of people choosing vegetarian entrées changed over the two-month period by labeling condition (total diner observations: N = 2,752). In this between-participant design, a mixed effects linear regression model (Table S5) tested whether the proportion of people selecting vegetarian entrées varied as a function of the interaction of labeling condition and time (day of study) as fixed effects, with the actual food served as a random effect. Data were missing from two days due to holiday closure and menu substitution.

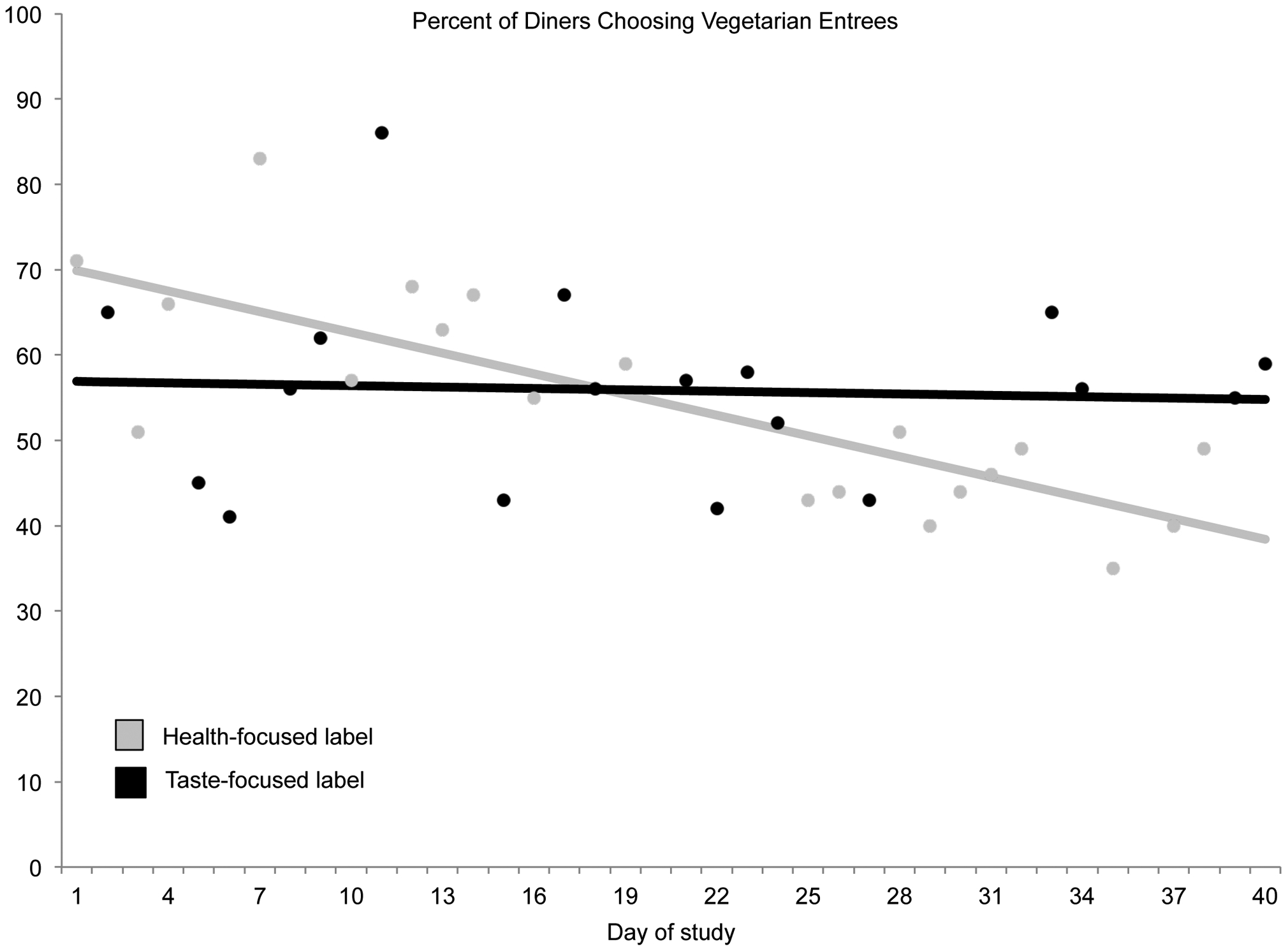

As hypothesized, we observed a significant effect of labeling condition over time on the proportion of people selecting vegetarian entrées (time ×label condition interaction: b = 0.75% per day, 95% CI: 0.27, 1.30; Figure 4). In the health-focused condition, selection of vegetarian entrées significantly decreased (b = −0.81, 95% CI: −1.17, −0.48) by 0.81% per day on average, a 45.1% decrease in the proportion of people choosing vegetarian entrees over the course of two months. However, the taste-focused labeling condition (portraying vegetarian entrées as tasty and indulgent), held selection of vegetarian entrées constant (b = −0.06, 95% CI: −0.41, 0.34), with a nonsignificant 3.7% decrease over the course of the study.

Fig 4. Food choice by label condition in Study 3.

Percent of diners (total N = 2,752) choosing vegetarian entrées by labeling condition over a two-month period in Study 3, conducted in northern California in 2017. Health-focused labeling (gray lines) described vegetarian entrées as health-focused, and taste-focused labeling (black lines) described vegetarian entrées as tasty and indulgent. Lines represent model estimates from a mixed effects linear regression model with fixed effects of label, time, and their interaction, and a random effect of food type (Table S5). Dots represent raw values observed on each study day for health-focused labeling and taste-focused labeling. The descriptive labels used for each day are presented in Table S4. No data was collected on days 20 or 36 due to holiday closure and menu substitution.

At the end of two months, significantly more people were choosing vegetarian entrées when labeled as tasty compared to as healthy (model predicted estimates: 54.8% (95% CI: 45.8, 64.0) vs. 38.4% (95% CI: 30.2, 46.5), Table S5). Because the average mass of food purchased per person per day did not change over time by condition (b = 0.01, 95% CI: −0.03, 0.05) we can infer that taste-focused labeling of vegetarian entrées displaced some proportion of meat consumption over time compared to health-focused labeling. Indeed, health-focused labeling of vegetarian entrées led to a significantly increased proportion of diners selecting only meat entrées over time (time ×label condition interaction: b = −0.71, 95% CI: −1.21, −0.21; simple effect of health-focused condition: b = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.45, 1.13).

These results replicate the beneficial impact of taste-focused labeling observed in Studies 1 and 2 in a different food environment where habitual customers paid by food weight, making consumption very likely, and using vegetarian entrees in direct competition with meat entrees, a difficult and increasingly important preference to target for health and sustainability (Ranganathan et al., 2016). Moreover, these results suggest that rather than being a short-lived effect, the benefit of taste-focused labeling led to sustained levels of vegetarian dish purchases over a two-month period within this café setting, which amounted to increasingly larger benefits over time compared to health-focused labeling. Surprisingly, health-focused labeling outperformed taste-focused labeling initially, which is counter to what Studies 1 and 2 would suggest. Prior research suggests that health-focused labeling may have led to decreased experienced tastiness and satisfaction (Raghunathan et al., 2006; Suher et al., 2016), possibly resulting in fewer diners choosing healthily labeled foods on repeat occasions. In contrast, taste-focused labeling may have led to positive taste experiences and encouraged selection of tastily labeled foods on subsequent occasions. However, because we were unable to survey customers throughout the study without impacting future choices, we do not know the mechanism by which taste-focused labels had increasingly beneficial effects over the long-term compared to health-focused labeling. Study 4 explicitly tested whether taste-focused labeling made people more likely to choose healthy foods because it enhanced the taste experience, improved mindsets about the tastiness of healthy foods, or both.

STUDY 4

Study 4 tested whether taste-focused labeling of healthy foods enhanced the experienced taste of healthy food as well as improved mindsets about healthy foods (i.e., the degree to which people associate healthy foods with tastiness). Green beans were served in a large university cafeteria, labeled on one day as healthy (“Light n’ Low Carb Green Beans and Shallots”) and on another as tasty (“Sweet Sizzlin’ Green Beans and Crispy Shallots”). On both days, diners who consumed green beans (total N = 203) were administered a survey during their meal that asked them to rate the green beans on healthiness, tastiness, and indulgence (1 = not at all, 5 = very). Diners’ mindsets about the tastiness of healthy foods were measured by indicating the extent to which they thought that healthy foods, in general, taste delicious (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Results of a two-tailed t-test demonstrated that diners who consumed green beans with a taste-focused label rated them as significantly more delicious (Mdifference = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.88) and indulgent (Mdifference = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.88), but as no less healthy (Mdifference = −0.10, 95% CI: −0.37, 0.16) compared to diners who ate green beans with a health-focused label (Figure 5). Furthermore, diners who consumed green beans with taste-focused labels were more likely to endorse the mindset that healthy foods taste delicious compared to diners who consumed green beans labeled as healthy (Mdifference = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.90). These results suggest that labeling healthy foods as tasty, compared to as healthy, not only leads more diners to choose healthy foods, but also enhances the taste experience when consuming healthy foods and helps establish the mindset that healthy foods can be delicious.

Fig 5. Post-consumption ratings by label condition in Study 4.

Bars represent means (95% CI) of N = 203 diners’ ratings of green bean deliciousness, indulgence, and healthiness on a five-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much) immediately post-consumption when labeled as healthy (gray bars) and as tasty (black bars) in Study 4, conducted in northern California in 2016.

DISCUSSION

In an attempt to improve dietary intake, governmental policy and commercial industry increasingly emphasize health qualities and nutritional benefits of healthy foods. However, our results suggest that taste-focused labeling may be more effective. Compared to health-focused labeling, taste-focused labeling increased selection of healthy foods by an average of 38% across Studies 1–3 (calculated as the mean percent increase across Studies 1 (48.7%), 2 (18.3% and 84.1%), and 3 (main effect when time was mean-centered = 2.4%)). Taste-focused labeling also sustained purchases of vegetarian entrees over a two-month period while health-focused labeling resulted in plummeting sales by 45.1%. Finally, taste-focused labeling enhanced the taste experience and mindsets about the tastiness of healthy foods compared to when people consumed the same foods with health-focused labels.

These changes were consistent with three target mechanisms by which smart food policy should improve dietary intake (Hawkes et al., 2015). First, the behavioral evidence suggests that taste-focused labeling encouraged people to reassess existing food preferences at the point-of-purchase, with more people ultimately reassessing healthy foods with taste-focused labels as more consistent with preferences than the same foods with health-focused labels. Second, taste-focused labeling provided an enabling environment for learning healthy food preferences. Not only did more individuals choose healthy foods with a taste-focused label, they experienced these foods as more delicious and indulgent. Moreover, taste-focused labeling improved mindsets about the deliciousness of healthy foods, helping to combat the pervasive, negative association between healthiness and tastiness that most individuals hold (Raghunathan et al., 2006). In the present work, mindset was measured as the explicit (conscious) belief that healthy foods taste good, but mindsets can also operate at the implicit (subconscious) level (Crum and Zuckerman, 2017; Crum et al., 2013; Dweck, 2008). Indeed, other research suggests that cognitive changes regarding the filling and tasty nature of foods also occur implicitly (unconsciously) (Raghunathan et al., 2006; Suher et al., 2016). These observed changes in cognition and behavior represent processes that compliment and mutually reinforce one another: consuming healthy foods with taste-focused labels enhances the taste experience, the positive taste experience improves mindsets about healthy foods, and improved mindsets increase the likelihood of selecting healthy foods again in the future. Third, though empirically testing a food systems response is outside the scope of most study designs, Hawkes and colleagues (2015) considered interventions that increased demand for and purchasing of healthy foods, as observed in the present studies, as stimulating a food systems response.

Addressing the fourth mechanism of smart food policy, it is important that healthy foods are accessible for groups of low socioeconomic status, across demographic groups, and across geographic regions. Though we did not directly examine this mechanism, existing evidence suggests that groups of low socioeconomic status and racial-ethnic minorities may view health-focused labeling as incongruent with their group identity (Oyserman et al., 2007). Future research is needed to test whether taste-focused labeling is perceived as more identity-congruent for these groups and encourages healthier food choices. In the present research, participants were primarily students and staff who dined at various settings on a college campus, perhaps limiting the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, Study 3 used a between-subjects design rather than a within-subjects design to measure the overall labeling effects on group-level behavior at the cafe, which limited the ability to quantify changes at the level of the individual.

Future studies should also explore how to communicate necessary nutritional information without using health-focused labeling for individuals with dietary restrictions. For the minority of individuals that prioritize healthiness more than tastiness, we expect that taste-focused labeling would be less effective because these individuals may seek health-focused language to affirm their desires to choose something that is, above all else, healthy (Campos et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Hawkes et al., 2015). An interesting question not tested in the present work is whether combining taste-focused and health-focused language would be effective. Perhaps leading with taste-focused labeling while including subtle nutrition-related symbols would be effective, as one study suggests that subtler health symbols are more effective than explicit health-focused language (Wagner et al., 2015). The present results do not mean that health messages, namely health warnings, should not be used on unhealthy foods such as those especially high in sugar or sodium (Donnelly et al., 2018; Roberto et al., 2016). Improving dietary health requires both enhancing the appeal of healthy foods as well as reducing the availability and lure of unhealthy foods. Efforts to prepare healthy foods deliciously are also important (Turnwald et al., 2017b). The effects of taste-focused labeling may not hold for foods of exceptionally poor quality. Finally, more research is needed to understand the long-term effects of taste-focused labeling on individuals’ mindsets about healthy foods, as only short-term effects on mindset were measured in the present work. Widespread efforts to enhance the way that healthy foods are portrayed could improve societal perceptions of healthy foods, perhaps helping to challenge the mindset that healthy foods are not tasty.

CONCLUSIONS

Labeling healthy foods with an emphasis on nutritional qualities and health benefits is becoming increasingly common. However, taste-focused labeling more effectively harnesses the recommendations for smart food policy design. Across four studies in a variety of real-world dining settings and a variety of healthy foods, taste-focused labeling increased selection of healthy foods by 38% compared to traditional health-focused labeling. By making the healthy choice and the delicious choice one and the same, taste-focused labeling represents a low-cost, scalable strategy that holds potential for increasing consumption of healthy foods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We wish to acknowledge Danielle Boles and Margaret Perry for assisting with data collection, and the Stanford University Residential & Dining Enterprises team for assisting with study implementation, particularly Jackie Bertoldo, Erica Holland-Toll, Eric Montell, Michael Gratz, and Shirley J. Everett. This material is based upon work supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (grant No. DGE-114747). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; and decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- Aggarwal A, Rehm CD, Monsivais P, Drewnowski A, 2016. Importance of taste, nutrition, cost and convenience in relation to diet quality: Evidence of nutrition resilience among US adults using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2010. Prev. Med 90, 184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich SN, Economos CD, Spiker ML, et al. , 2017a. A systematic review of calorie labeling and modified calorie labeling interventions: impact on consumer and restaurant behavior. Obesity, 25 (12), 2018–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich SN, Wolfson JA, Jarlenski MP, 2017b. Calorie changes in large chain restaurants from 2008 to 2015. Prev. Med 100, 112–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JP, Roberto CA, 2014. Potential benefits of calorie labeling in restaurants. JAMA 312, 887–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos S, Doxey J, Hammond D, 2011. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 14 (8), 1496–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Jahns L, Gittelsohn J, Wang Y, 2012. Who is missing the message? Targeting strategies to increase food label use among US adults. Public Health Nutr. 15 (5), 760–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum A, Zuckerman B, 2017. Changing Mindsets to Enhance Treatment Effectiveness. JAMA 317 (20), 2063–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum AJ, Corbin WR, Brownell KD, Salovey P, 2011. Mind over milkshakes: mindsets, not just nutrients, determine ghrelin response. Health Psychol. 30 (4), 424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum AJ, Leibowitz KA, Verghese A, 2017. Making mindset matter. BMJ 356, j674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum AJ, Salovey P, Achor S, 2013. Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 104 (4), 716–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly GE, Zatz LY, Svirsky D, John LK, 2018. The Effect of Graphic Warnings on Sugary-Drink Purchasing. Psychol. Sci 29 (8), 1321–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS, 2008. Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci 17 (6), 391–394. [Google Scholar]

- Fenko A, Kersten L, Bialkova S, 2016. Overcoming consumer scepticism toward food labels: The role of multisensory experience. Food Qual. Pref 48, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes AC, Oliveira RC, Proença RP, Curioni CC, Rodrigues VM, Fiates GM, 2016. Influence of menu labeling on food choices in real-life settings: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev 74 (8), 534–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein SR, Fishbach A, 2010. When healthy food makes you hungry. J. Consumer Res 37 (3), 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani NR, Calcott RD, Berkman ET, 2013. Piece of cake. Cognitive reappraisal of food craving. Appetite 64, 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Basil M, Maibach E, Goldberg J, Snyder D, 1998. Why Americans eat what they do: taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. J. Am. Diet. Assoc 98 (10), 1118–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, Levy D, et al. , 2011. Changing the future of obesity: science, policy, and action. Lancet 378 (9793), 838–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabenhorst F, Schulte FP, Maderwald S, Brand M, 2013. Food labels promote healthy choices by a decision bias in the amygdala. Neuroimage 74, 152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C, Smith TG, Jewell J, et al. , 2015. Smart food policies for obesity prevention. Lancet 385 (9985), 2410–2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, van Koningsbruggen GM, Stroebe W, Ramanathan S, Aarts H, 2010. As pleasure unfolds: Hedonic responses to tempting food. Psychol. Sci 21 (12), 1863–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Yang B, Zheng J, Li G, Wahlqvist ML, Li D, 2012. Cardiovascular disease mortality and cancer incidence in vegetarians: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann. Nutr. Metab 60 (4), 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiszko KM, Martinez OD, Abrams C, Elbel B, 2014. The influence of calorie labeling on food orders and consumption: a review of the literature. J. Community Health 39 (6), 1248–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lähteenmäki L, Lampila P, Grunert K, Boztug Y, Ueland Ø, Åström A, Martinsdóttir E, 2010. Impact of health-related claims on the perception of other product attributes. Food Policy 35 (3), 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson SC, Orsini N, 2013. Red meat and processed meat consumption and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol 179 (3), 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le LT, Sabaté J, 2014. Beyond meatless, the health effects of vegan diets: findings from the Adventist cohorts. Nutrients 6 (6), 2131–2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennernäs M, Fjellström C, Becker W, Giachetti I, Schmitt A, De Winter A, Kearney M, 1997. Influences on food choice perceived to be important by nationally-representative samples of adults in the European Union. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr 51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem D, Aydin NT, Zandstra E, 2012. Effects of health labels on expected and actual taste perception of soup. Food Qual. Pref 25 (2), 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. , 2013. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380 (9859), 2224–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long MW, Tobias DK, Cradock AL, Batchelder H, Gortmaker SL, 2015. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of restaurant menu calorie labeling. Am. J. Public Health, 105 (5), e11–e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Ward A, 2015. Promoting Public Health in the Context of the “Obesity Epidemic” False Starts and Promising New Directions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci 10 (6), 706–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew A-M, Samuels B, Chatman J, 2007. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am. Psychol 62 (3), 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J, Mischel W, 1999. A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: dynamics of willpower. Psychol. Rev 106 (1), 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Fryberg SA, Yoder N, 2007. Identity-based motivation and health. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 93 (6), 1011–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan R, Naylor RW, Hoyer WD, 2006. The unhealthy= tasty intuition and its effects on taste inferences, enjoyment, and choice of food products. J. Mark 70 (4), 170–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan J, Vennard D, Waite R, Dumas P, Lipinski B, Searchinger T, 2016. Shifting diets for a sustainable food future. World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto CA, Larsen PD, Agnew H, Baik J, Brownell KD, 2010. Evaluating the impact of menu labeling on food choices and intake. Am. J. Public Health 100 (2), 312–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto CA, Swinburn B, Hawkes, et al. , 2015. Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet 385 (9985), 2400–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto CA, Wong D, Musicus A, Hammond D, 2016. The influence of sugar-sweetened beverage health warning labels on parents’ choices. Pediatrics 137 (2), e20153185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PN, Sabaté J, Fraser GE, 2003. Does low meat consumption increase life expectancy in humans? Am. J. Clin. Nutr 78 (3), 526S–532S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suher J, Raghunathan R, Hoyer WD, 2016. Eating healthy or feeling empty? How the “healthy= less filling” intuition influences satiety. J. Assoc. Consumer Res 1 (1), 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler Richard H, Sunstein Cass R, 2008. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turnwald BP, Boles DZ, Crum AJ, 2017a. Association between indulgent descriptions and vegetable consumption: twisted carrots and dynamite beets. JAMA Intern. Med 177 (8), 1216–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnwald BP, Boles DZ, Crum AJ, 2017b. Selection Does Not Equate Consumption—reply. JAMA Intern. Med 177 (12), 1875–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnwald BP, Jurafsky D, Conner A, Crum AJ, 2017c. Reading between the menu lines: are restaurants’ descriptions of “healthy” foods unappealing? Health Psychol. 36 (11), 1034–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuizen MG, Nachtigal DJ, Flammer LJ, de Araujo IE, Small DM, 2013. Verbal descriptors influence hypothalamic response to low-calorie drinks. Molec. Metab 2 (3), 270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke W, 2006. Functional foods: Consumer willingness to compromise on taste for health? Food Qual. Pref 17 (1–2), 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner HS, Howland M, Mann T, 2015. Effects of subtle and explicit health messages on food choice. Health Psychol. 34 (1), 79–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, Wilson TD, 2018. Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychol. Rev 125 (5), 617–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.