Summary

The Canadian Network for International Surgery (CNIS) hosted a workshop in May of 2020 with a goal of critically evaluating Trauma Team Training courses. The workshop was held virtually because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Twenty-three participants attended from 8 countries: Canada, Guyana, Kenya, Nigeria, Switzerland, Tanzania, Uganda and the United States. More participants were able to attend the virtual meeting than the traditional in-person meetings. Web-based videoconference software was used, participants presented prerecorded PowerPoint videos, and questions were raised using a written chat. The review proved successful, with discussions and recommendations for improvements surrounding course quality, lecture content, skills sessions, curriculum variations and clinical practical scenarios. The CNIS’s successful experience conducting an online curriculum review involving international participants may prove useful to others proceeding with collaborative projects during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has swiftly led to tremendous changes in health care delivery and continuing medical education (CME). Pandemic physical distancing requirements have resulted in changes to the methods of CME delivery around the world.

Accredited course curricula require frequent review by experts in the subject to update and improve course materials to maintain the quality and relevance of the course. Curriculum reviews are integral to maintaining the quality of CME courses as the relevant literature advances. This is the case for the Canadian Network for International Surgery’s (CNIS) Trauma Team Training (TTT) courses. Evaluating and improving an internationally developed course such as CNIS TTT, which is taught in remote, underserviced and resource-limited jurisdictions, in the setting of pandemic travel restrictions and physical distancing requirements poses a unique set of challenges. Access to international experts and regional leaders and officials are vital to maintaining CME offerings, particularly for courses like TTT, which depend on collaboration with local and international experts to improve and administer the course. The main challenge is how to evaluate, update and offer a CME-accredited course during a pandemic.

The CNIS is a registered not-for-profit charity focused on improving the quality and availability of medical services offered in low- to middle-income countries, particularly within Africa and South America. The CNIS offers training courses in the fields of surgery, obstetrics and injury prevention targeting health professionals ranging from community health practitioners to surgical specialists. The TTT courses, which have been taught since 1997, use principles of trauma epidemiology and were implemented in response to the lack of trauma training in low- and middle-income countries. The instructional unit emphasized in the TTT courses is the team, not the individual. Three TTT courses are offered: the TTT Participants course provides adaptable, team-based skills for trauma management in low resource settings; the Update course functions as a refresher for individuals who have taken the Participants course; and the Instructors course focuses on training instructors to conduct the Participants course. The TTT curriculum is reviewed on a biannual basis. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the CNIS TTT curriculum review, originally intended to occur at the Bethune Round Table conference, which was cancelled, was conducted by international video conference.

The use of online video conferencing platforms has grown exponentially during pandemic-imposed physical distancing, restricted travel and at-home work. These web-based tools allow ongoing collaboration while following local public health physical distancing guidelines. Academic conferences have been previously conducted online,1 and usually feature their own set of proposed rules.2 To our knowledge, the use of online video conference software in CME curriculum maintenance and delivery has not previously been described. Use of the Zoom online meeting platform was proposed as an alternative to the face-to-face meeting planned for the TTT curriculum review. We hypothesized that not only would it accommodate current public health mandates, but it would also encourage greater participation than if it were offered in person,3 as international attendees could attend without substantial travel cost or visa requirements. The TTT curriculum review meeting was therefore conducted online on May 31, 2020, using Zoom.

The TTT curriculum review requested that participants register before the meeting but allowed participation without registration. A follow-up survey was conducted to confirm attendance. Topic experts created prerecorded PowerPoint presentations using a provided template.4 Meeting etiquette and guidelines were provided and agreed upon and included the following: remaining muted unless called upon, using the chat function to ask and respond to questions, and a maximum PowerPoint presentation length of 7 minutes. The review focused on 4 key objectives for improving the TTT courses: lecture quality and content, skills sessions updates, international curriculum implementation variations and practice scenarios. Pediatric content and participant certification were also discussed, as these topics had previously been identified at the 2019 CNIS TTT Instructor courses in Edmonton, Canada, and Georgetown, Guyana.

A total of 23 participants were present for the TTT curriculum review meeting, including 2 staff members from the CNIS. Participants attended from 8 countries spread over 10 time zones: Canada, Guyana, Kenya, Nigeria, Switzerland, Tanzania, Uganda and the United States, with the majority of participants from outside of North America. The TTT courses are designed for low- to middle-income settings, thus the international participants’ expertise proved immensely valuable. Members from the CNIS,4 as well as partners from Guyana,5 Tanzania,6 and Kenya7 were invited to share an overview of the TTT course offerings in their respective countries, as well as any needs or concerns relating to the TTT courses. Each presentation was followed by a critical discussion among representatives of the CNIS, the presenter and other meeting participants to determine how the TTT courses can be adapted to meet the presenter’s objectives.

A short breakout session was also conducted that randomly assigned the participants to smaller chat rooms with 3–4 others to facilitate small group discussion and networking. The next segment of the curriculum review meeting involved local and international participants presenting on topics pertaining to improvements for course lectures,5 skills sessions4 and team exercises.5 Interestingly, owing to the uncertainty about the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, adaptations to the team exercise component of the TTT course were proposed to allow for physical distancing measures. This involved a maximum number of people per room depending on physical space and distancing requirements. This was followed by 2 presentations on cross-cutting themes: pediatric trauma4 and TTT course evaluations.8

The final portion of the TTT curriculum review meeting involved general logistical updates on the 3 TTT courses from select representatives,4 followed by a presentation from the United Nations Institute for Training and Research.9 The meeting concluded with an open plenary for participants to chat further. More than 90% of participants stayed for the entire meeting.

Challenges encountered during the session included variable video file formats, facilitating interaction without interrupting proceedings, maintaining meeting flow and meeting set objectives. Owing to different standards in PowerPoint video recordings and file formats within and among countries, technical difficulties were encountered. Fortunately, the Zoom platform supports screen sharing, which allowed prerecorded presentations to be played by each presenter. Going forward, setting clear deadlines for prerecorded materials and testing them on the meeting host’s computer would prove beneficial. Using the embedded text chat function allowed participant interaction and comment without interrupting proceedings and increased the meeting efficiency. The breakout session provided a means for participants from different countries to exchange ideas pertaining to low-resource setting trauma care. The meeting was conducted around 2 hosts: 1 was responsible for the technical aspects of the meeting, including playing PowerPoint videos and administering breakout rooms, while the other facilitated participant questions and comments and kept the meeting focused on the agenda.

Further, the meeting was set to begin at a time convenient for the majority of participants based on their country of residence. For most attendees, the meeting began in the afternoon; however, some started earlier in the morning, and some later in the evening.

An online survey was distributed the following day to assess the TTT courses and their experience with the web-based delivery of our curriculum review. Twelve responses were recorded from the survey for a response rate of 57% from non-CNIS participants. Questions addressed the meeting overall, PowerPoint video quality, the chat function, and enjoyment of breakout rooms. Participants were also asked a series of questions to ensure they were eligible to obtain CME credits. These questions addressed whether the meeting was relevant to their practice, potential sources of bias, whether they wanted to receive feedback and competency scores, and which CanMEDS competencies10 they believed were strengthened.

Participants’ ratings of the meeting and features used were overwhelmingly positive.

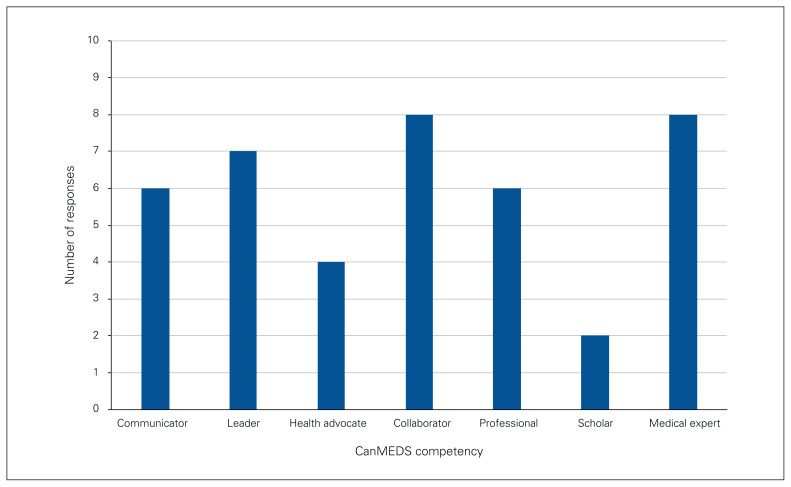

Many participants volunteered to accept specific assignments to improve the curriculum and agreed to meet again in the following months to finalize the curriculum. Interestingly, participants indicated as a whole that all CanMEDS competencies were achieved in this meeting, with the medical expert and collaborator roles being the most commonly indicated (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Participants’ self-rating of strengthened CanMEDS competencies from participating in the TTT curriculum review meeting. Note that participants were encouraged to select more than one option.

If the COVID-19 pandemic prevents the organization of large academic conferences, our hope is that the successes from the TTT curriculum review meeting can be adapted to fit other types of academic activities, allowing for virtual academic conferences where smaller groups can congregate to chat, earn CME credits, and participate in other conference-related activities. Additionally, the methods explored could support the virtual teaching of CME offerings, especially those that involve the expertise of international sponsors. For example, the CNIS is piloting a fully virtual TTT course in the African region using an online video platform, social distancing measures and local leaders to organize the course.

We encourage further exploration of web-based delivery of CME courses and exploration of novel CME programs during the COVID-19 pandemic. The current body of literature would benefit from studies looking at optimizing such features in the context of medical education as well as international collaboration. Altogether, the CNIS hopes that its experience with maintaining an international CME-accredited course proves useful to other organizations.

Conclusion

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will be felt on a global scale for months, and possibly years to come. As information is rapidly changing, so has the delivery of CME. Organizations must continue to update the curricula of CME offerings to meet the ever-changing global realities during this pandemic. The CNIS has successfully piloted a fully virtual curriculum review of an internationally offered CME-accredited course. International participation was not impeded by travel costs, visa refusal, or jet lag. By sharing their findings through the literature, the CNIS hopes to encourage regular virtual reviews of CME courses during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, the CNIS expects to conduct the Bethune Round Table with support from Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, Canada. The next challenge will be to have international participation in the TTT Providers course itself and to test alternative live-steaming tools to facilitate delivery of trauma skills training courses.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: All authors contributed substantially to the conception, writing and revision of this article and approved the final version for publication.

References

- 1.Sá MJ, Ferreira CM, Serpa S. Virtual and face-to-face academic conferences: comparison and potentials. Journal of Educational and Social Research. 2019;9:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gichora NN, Fatumo SA, Ngara MV, et al. Ten simple rules for organizing a virtual conference–anywhere. PLOS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr T. Designing online conferences to promote professional development in Africa. Int J Educ Dev Using Inf Commun Technol. 2016;12:80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Canadian Network for International Surgery. TTT Canada; 2020. [accessed 2020 July 20]. Available: https://bit.ly/tttcanada/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.TTT Guyana. The Canadian Network for International Surgery. 2020. [accessed 2020 July 20]. Available: https://bit.ly/tttguyana/

- 6.The Canadian Network for International Surgery. TTT Tanzania; 2020. [accessed 2020 July 20]. Available: https://bit.ly/ttttanzania/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Canadian Network for International Surgery. TTT Kenya; 2020. [accessed 2020 July 20]. Available: https://bit.ly/tttkenya/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Canadian Network for International Surgery. TTT United States; 2020. [accessed 2020 July 20]. Available: https://bit.ly/tttunitedstates/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Canadian Network for International Surgery. TTT Switzerland; 2020. [accessed 2020 July 20]. Available: https://bit.ly/tttswitzerland/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank J, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS 2015 Physician competency Framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]