Abstract

Understanding how and why rates of character evolution vary across the Tree of Life is central to many evolutionary questions; for example, does the trophic apparatus (a set of continuous characters) evolve at a higher rate in fish lineages that dwell in reef versus nonreef habitats (a discrete character)? Existing approaches for inferring the relationship between a discrete character and rates of continuous-character evolution rely on comparing a null model (in which rates of continuous-character evolution are constant across lineages) to an alternative model (in which rates of continuous-character evolution depend on the state of the discrete character under consideration). However, these approaches are susceptible to a “straw-man” effect: the influence of the discrete character is inflated because the null model is extremely unrealistic. Here, we describe MuSSCRat, a Bayesian approach for inferring the impact of a discrete trait on rates of continuous-character evolution in the presence of alternative sources of rate variation (“background-rate variation”). We demonstrate by simulation that our method is able to reliably infer the degree of state-dependent rate variation, and show that ignoring background-rate variation leads to biased inferences regarding the degree of state-dependent rate variation in grunts (the fish group Haemulidae). [Bayesian phylogenetic comparative methods; continuous-character evolution; data augmentation; discrete-character evolution.]

Variable rates of continuous-character evolution are central to many evolutionary questions. These questions may involve changes in the rate of character evolution over time (time-dependent scenarios) or among lineages (lineage-specific scenarios). Such questions may be pursued by means of agnostic surveys to detect rate variation (data-exploration approaches; Harmon et al. 2010; Eastman et al. 2011; Venditti et al. 2011) or by testing predictions regarding factors hypothesized to influence rates of character evolution (hypothesis-testing approaches; O’Meara et al. 2006; Collar et al. 2009). A particular type of hypothesis posits that the rate of continuous-character evolution depends on the state of a discrete trait, for example, the evolutionary rate of the feeding apparatus (a set of continuous traits) in a lineage depends on the habitat type (the discrete trait) of its members.

Testing hypotheses regarding state-dependent rates of continuous-character evolution is currently pursued using a computational procedure (e.g., Collar et al. 2009, 2010; Price et al. 2011, 2013) comprised of four steps: 1) fit a Brownian motion model to the observations (the tree and continuous-trait values at its tips), where the rate of continuous-character evolution is assumed to be constant across all branches of the tree (the “null” or constant-rate model); 2) generate a sample of discrete-character histories (“stochastic maps”, Nielsen 2002; Huelsenbeck et al. 2003); 3) for each stochastic map, fit a Brownian motion model to the observations, where the instantaneous rate of continuous-character evolution at a given point on a given branch depends on the corresponding state of the discrete-character mapping (the “state-dependent model” O’Meara et al. 2006), and; 4) compare the fit of the state-dependent model (averaged over the sample of stochastic maps) to the constant-rate model using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). If the state-dependent model is preferred, we infer that rates of continuous-character evolution are correlated with the state of the discrete character.

The current approach has two potential problems. First, stochastic maps of the discrete character are generated without reference to the continuous characters. By construction, however, the state-dependent model specifies that the discrete and continuous characters are evolving jointly. The continuous characters therefore possess information about the history of the discrete character; disregarding this mutual information will lead to biased parameter estimates Revell 2012). Second, the null model—where the continuous characters are assumed to evolve at a constant rate across lineages—is extremely unrealistic. Any variation in the rate of continuous-character evolution—whether or not it is associated with the discrete character under consideration—is apt to be interpreted as evidence against the overly simplistic null model. This “straw-man effect” has the potential to mislead our inferences regarding the factors that impact rates of continuous-character evolution.

We describe a Bayesian approach for inferring the impact of a discrete trait on rates of continuous-character evolution that addresses the problems described above. We begin by developing a stochastic process that explicitly models the joint evolution of the discrete and continuous characters; this stochastic process can accommodate one or more continuous characters evolving under a state-dependent multivariate Brownian motion process. We refer to this new model as MuSSCRat (for Multiple State-Specific Rates of continuous-character evolution). We then develop an inference model that accommodates variation in the background rate of continuous-character evolution (i.e., rate variation across lineages that is independent of the discrete character under consideration). We implement this model in a Bayesian framework, which accommodates uncertainty in the phylogeny, discrete-character history, and parameters of the state-dependent model. We show by simulation that the method is able to reliably infer the state-dependent rates of continuous-character evolution, and that ignoring background-rate variation leads to an inflated false-positive rate. Finally, we demonstrate the new method with an empirical analysis of grunts (a group of haemulid fish) to illustrate the impacts of background-rate variation and prior specification on inferences about state-dependent rate variation.

Methods

Our goal is to develop a state-dependent multivariate Brownian motion model, MuSSCRat, in a Bayesian statistical framework. We begin with a simple simulation to describe the parameters and basic properties of the MuSSCRat model. We then show how to calculate the probability of observing the discrete and continuous characters across the tips of a phylogeny under the model (i.e., how to compute the likelihood). Finally, we describe the relevant details—the priors and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) machinery—required to perform Bayesian inference under the MuSSCRat model.

The State-Dependent Multivariate Brownian Motion Process

A simulation example

We introduce the salient properties of the MuSSCRat model by

describing a simple simulation with a binary discrete character,

, and a single continuous character,

, and a single continuous character,

, over a single branch. The discrete

character has two states, 0 and 1; the continuous character can be any real number. The

state of the simulation at time

, over a single branch. The discrete

character has two states, 0 and 1; the continuous character can be any real number. The

state of the simulation at time  is the pair of

discrete- and continuous-character values,

is the pair of

discrete- and continuous-character values,  . (We use

capital letters—

. (We use

capital letters— and

and  —to

represent random variables, and lowercase letters—

—to

represent random variables, and lowercase letters— and

and

—to represent specific values of those

random variables.)

—to represent specific values of those

random variables.)

The discrete trait evolves under a continuous-time Markov process, changing from state

0 to state 1 with rate  , and from state 1 to state 0 with

rate

, and from state 1 to state 0 with

rate  . The continuous character evolves

under a state-dependent Brownian motion process, where the diffusion rate,

. The continuous character evolves

under a state-dependent Brownian motion process, where the diffusion rate,

, measures the rate of

continuous-character evolution when the discrete character is in state

, measures the rate of

continuous-character evolution when the discrete character is in state

(i.e.,

(i.e.,  indicates that the continuous

character evolves faster in discrete state 1 than in discrete state 0). In a small time

interval of duration

indicates that the continuous

character evolves faster in discrete state 1 than in discrete state 0). In a small time

interval of duration  , where the discrete character

begins in state

, where the discrete character

begins in state  , the continuous character changes by a

normally distributed random variable with mean 0 and variance

, the continuous character changes by a

normally distributed random variable with mean 0 and variance  , and the discrete character

changes state with probability

, and the discrete character

changes state with probability  .

.

We begin the simulation at time  , with the

discrete character in state

, with the

discrete character in state  and the continuous character with

value

and the continuous character with

value  . We then increment the simulation

forward in time by a small time interval,

. We then increment the simulation

forward in time by a small time interval,  , applying the

above rules describing how the state of the process changes during each time interval.

We continue to increment the simulation forward in time until we reach the end of the

branch (at time

, applying the

above rules describing how the state of the process changes during each time interval.

We continue to increment the simulation forward in time until we reach the end of the

branch (at time  ). The outcome of the simulation is a

sample path that records the state of the process from the beginning

to the end of the branch (Fig. 1a).

). The outcome of the simulation is a

sample path that records the state of the process from the beginning

to the end of the branch (Fig. 1a).

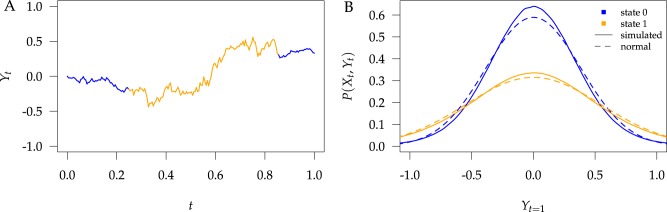

Figure 1.

Simulations under the state-dependent multivariate Brownian motion process. The

process is either in discrete state 0 (blue) or discrete state 1 (orange), where the

rate of change between discrete states is equal ( ), and the rate of

continuous-character evolution is higher when the process is in the orange state

(

), and the rate of

continuous-character evolution is higher when the process is in the orange state

( ,

,

). A) A single sample path

from

). A) A single sample path

from  to

to  . The process begins and ends in the

blue state, but spends some time in the orange state. Note that there is more

evolution in the orange state than in the blue state. B) The distribution of end

states for 10 million simulated realizations. Solid lines represent the simulated

joint probability densities of the discrete and continuous states. Dashed lines

represent the normal densities with parameters estimated from the simulated end

states. Note that the simulated densities depart from the normal densities (both

Kolmogorov–Smirnov

. The process begins and ends in the

blue state, but spends some time in the orange state. Note that there is more

evolution in the orange state than in the blue state. B) The distribution of end

states for 10 million simulated realizations. Solid lines represent the simulated

joint probability densities of the discrete and continuous states. Dashed lines

represent the normal densities with parameters estimated from the simulated end

states. Note that the simulated densities depart from the normal densities (both

Kolmogorov–Smirnov

The transition-probability density specifies the probability that the

process ends in some state,  , given an initial state

, given an initial state

, after a certain amount of

time,

, after a certain amount of

time,  , has elapsed. The resulting frequency

histogram of end states provides a Monte Carlo approximation of the

transition-probability density for a branch of duration

, has elapsed. The resulting frequency

histogram of end states provides a Monte Carlo approximation of the

transition-probability density for a branch of duration

. Note that the transition-probability

densities of standard (i.e., state-independent) Brownian motion processes are normal

densities. By contrast, it is clear from our simulations that the transition-probability

densities under the state-dependent process are not normal densities (Fig. 1b).

. Note that the transition-probability

densities of standard (i.e., state-independent) Brownian motion processes are normal

densities. By contrast, it is clear from our simulations that the transition-probability

densities under the state-dependent process are not normal densities (Fig. 1b).

Parameters of the MuSSCRat model

We model the joint evolution of a discrete binary character,  , and

a set of

, and

a set of  continuous characters,

continuous characters,

, as a stochastic process.

The discrete trait has two possible values, which we arbitrarily label

, as a stochastic process.

The discrete trait has two possible values, which we arbitrarily label

and

and  ;

;

. The continuous characters

are a vector of real-valued random variables, where

. The continuous characters

are a vector of real-valued random variables, where  is

the value of the

is

the value of the  continuous character

(

continuous character

( ).

Variables of the MuSSCRat model are summarized in Table 1.

).

Variables of the MuSSCRat model are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The variables of the MuSSCRat model and their interpretation.

| Variable | Interpretation |

|---|---|

|

The continuous characters for one lineage |

|

The state of the continuous characters at time

|

|

The number of continuous characters |

|

An  matrix containing the matrix containing the

continuous characters for the continuous characters for the

species in the tree species in the tree |

|

The discrete character for one lineage |

|

The state of the discrete character at time

|

|

An  matrix containing the

discrete character for the matrix containing the

discrete character for the  species in the

tree species in the

tree |

|

The complete history of the discrete character (the state at the beginning and end of the process, |

and all of the changes in between) along the lineage

|

|

|

The instantaneous-rate matrix of the discrete-character CTMC model |

|

The instantaneous rate of change from state

to state to state

|

|

The background rate of continuous-character evolution among all lineages |

|

The background rate of continuous-character evolution for lineage

|

|

The relative rates of continuous-character evolution for each continuous character |

|

The relative rates of continuous-character evolution for each discrete state |

|

The evolutionary correlation matrix |

|

The evolutionary correlation between continuous characters

and and

|

|

The discrete-state-independent evolutionary variance–covariance matrix |

We assume that the discrete character evolves under a continuous-time Markov process,

and that the continuous characters evolve under a multivariate Brownian motion process

with rates that depend on the state of the binary character. These model components

collectively describe how the set of characters,  , evolve together over a

single branch; we detail the evolutionary dynamics of this process over an entire tree

when we describe the likelihood function.

, evolve together over a

single branch; we detail the evolutionary dynamics of this process over an entire tree

when we describe the likelihood function.

The instantaneous-rate matrix,  , describes the rates

at which the binary character evolves:

, describes the rates

at which the binary character evolves:  describes the

instantaneous rate of change from state

describes the

instantaneous rate of change from state  to state

to state

:

:

|

The complete history of the discrete trait on branch  —which

we represent as

—which

we represent as  —specifies the state of the

character at the beginning and end of the branch, and also the times of any state

changes along the branch.

—specifies the state of the

character at the beginning and end of the branch, and also the times of any state

changes along the branch.

While the process is in a particular discrete state, we assume the continuous

characters evolve under a multivariate Brownian motion model. We allow the background

rate of evolution to vary among lineages in the phylogeny by letting each branch have

its own rate parameter,  (we call this “background-rate

variation”). While in discrete state

(we call this “background-rate

variation”). While in discrete state  , the background rate

is multiplied by the state-specific relative rate,

, the background rate

is multiplied by the state-specific relative rate,  . We also allow the relative rate

of evolution to vary among the continuous characters. The vector

. We also allow the relative rate

of evolution to vary among the continuous characters. The vector

contains these

relative rates;

contains these

relative rates;  is the relative rate at which

continuous character

is the relative rate at which

continuous character  evolves. The evolutionary correlations

between characters are contained in the

evolves. The evolutionary correlations

between characters are contained in the  symmetric

correlation matrix,

symmetric

correlation matrix,  , where

, where  specifies the

correlation between characters

specifies the

correlation between characters  and

and

.

.

We assume that the relative rates of change between characters,

, and the

evolutionary correlations between characters,

, and the

evolutionary correlations between characters,  , are independent of

the discrete state; in other words, we assume that the state of the discrete trait

affects only the overall rate of continuous-character evolution, but

not the nature of the evolutionary process (as represented by

, are independent of

the discrete state; in other words, we assume that the state of the discrete trait

affects only the overall rate of continuous-character evolution, but

not the nature of the evolutionary process (as represented by

and

and

). We combine the relative rates among

characters and the correlation matrix to form the overall evolutionary

variance-covariance matrix,

). We combine the relative rates among

characters and the correlation matrix to form the overall evolutionary

variance-covariance matrix,  :

:

|

Bayesian Inference

We implement the MuSSCRat model with background-rate variation as a Bayesian model to infer the joint posterior density of the parameters given the observed data. We must specify both the likelihood function and also the joint prior density to compute the joint posterior distribution. We describe each of these components below.

Data

We imagine that we have sampled one discrete character and  continuous characters for each of

continuous characters for each of  species; relationships

among these species are defined by the phylogeny,

species; relationships

among these species are defined by the phylogeny,  .

We store the discrete characters in an

.

We store the discrete characters in an  column

vector,

column

vector,  , and the continuous

characters in an

, and the continuous

characters in an  matrix,

matrix,

. We assume that the discrete

and continuous characters evolve independently along each of the

. We assume that the discrete

and continuous characters evolve independently along each of the

branches of the tree. We index the

internal nodes according to their sequence in a post-order traversal of the tree,

starting from the root (which has index

branches of the tree. We index the

internal nodes according to their sequence in a post-order traversal of the tree,

starting from the root (which has index  ).

).

Likelihood function

We simplify likelihood calculations by including the vector of character histories,

, where

, where

is the discrete-character

history along branch

is the discrete-character

history along branch  (including the state at the beginning

and end of the branch), as variables in the model. In effect, we are “augmenting” the

discrete-character data observed at the tips of the tree with unobserved

discrete-character histories over the entire tree; this technique is referred to as

data augmentation (Tanner and Wong

1987; Robinson et al. 2003; Mateiu and Rannala 2006; Lartillot 2006; Landis et al.

2013).

(including the state at the beginning

and end of the branch), as variables in the model. In effect, we are “augmenting” the

discrete-character data observed at the tips of the tree with unobserved

discrete-character histories over the entire tree; this technique is referred to as

data augmentation (Tanner and Wong

1987; Robinson et al. 2003; Mateiu and Rannala 2006; Lartillot 2006; Landis et al.

2013).

The augmented likelihood is a product of the joint probability of

and

the conditional probability density of

and

the conditional probability density of  given

given

:

:

|

where  are the parameters of the

MuSSCRat model. We compute the joint probability of

are the parameters of the

MuSSCRat model. We compute the joint probability of

as a

product of independent probabilities across each of the

as a

product of independent probabilities across each of the  branches:

branches:

|

where  is

an indicator function that ensures that character histories are consistent across

ancestor-descendant branches (i.e., that the state at the end of one branch matches the

state at the beginning of its descendant branches), and ensures that character histories

for terminal branches end in the observed state. We compute

is

an indicator function that ensures that character histories are consistent across

ancestor-descendant branches (i.e., that the state at the end of one branch matches the

state at the beginning of its descendant branches), and ensures that character histories

for terminal branches end in the observed state. We compute  as

illustrated in Figure 2. By convention, we use the

stationary distribution of the Markov chain defined by

as

illustrated in Figure 2. By convention, we use the

stationary distribution of the Markov chain defined by  as

the probability of the root state,

as

the probability of the root state,  .

.

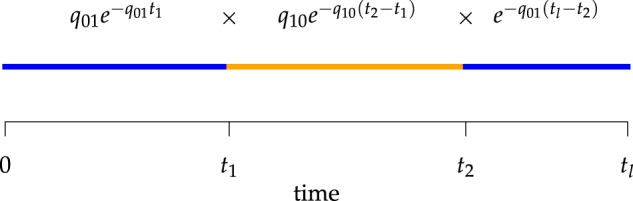

Figure 2.

Computing the probability of a character history,  . Blue and orange segments

correspond to discrete states 0 and 1, respectively. The probability of the history

is the product of the probabilities of waiting times between events (or the

probability of no event in the final segment) given the current rate of change.

. Blue and orange segments

correspond to discrete states 0 and 1, respectively. The probability of the history

is the product of the probabilities of waiting times between events (or the

probability of no event in the final segment) given the current rate of change.

To calculate the conditional probability density of the continuous characters, we first

consider how the continuous characters,  , evolve

along a single branch of length

, evolve

along a single branch of length  when the history of

the discrete character along that branch is known. Given that the discrete character is

in state

when the history of

the discrete character along that branch is known. Given that the discrete character is

in state  for duration

for duration  ,

changes in the continuous character follow a multivariate normal distribution with mean

,

changes in the continuous character follow a multivariate normal distribution with mean

and variance-covariance

matrix

and variance-covariance

matrix  .

This implies that the changes in

.

This implies that the changes in  while in

discrete state

while in

discrete state  ,

,  , are

multivariate-normally distributed:

, are

multivariate-normally distributed:

|

where  is the amount of time

the history spends in discrete state

is the amount of time

the history spends in discrete state  and

and

is a

is a

vector of zeros (indicating

that the expected amount of change for each continuous character is 0). Because it is

the sum of multivariate-normally distributed random variables,

vector of zeros (indicating

that the expected amount of change for each continuous character is 0). Because it is

the sum of multivariate-normally distributed random variables,  is also multivariate-normally distributed:

is also multivariate-normally distributed:

|

where  is the branch-specific variance-covariance matrix given the discrete-character history

and the background rate of evolution for the branch,

is the branch-specific variance-covariance matrix given the discrete-character history

and the background rate of evolution for the branch,  .

.

Because changes to the continuous characters follow a multivariate normal distribution,

we can compute the conditional probability density of the continuous characters,

,

using standard algorithms to integrate over the distributions of the states at internal

nodes. Specifically, we use Felsenstein’s REML algorithm (Felsenstein 1973, 2004), extended to

multivariate Brownian motion (Huelsenbeck and Rannala

2003; Freckleton 2012), to compute the

conditional probability density of

,

using standard algorithms to integrate over the distributions of the states at internal

nodes. Specifically, we use Felsenstein’s REML algorithm (Felsenstein 1973, 2004), extended to

multivariate Brownian motion (Huelsenbeck and Rannala

2003; Freckleton 2012), to compute the

conditional probability density of  . This

algorithm assumes a uniform prior over all possible continuous states at the root.

. This

algorithm assumes a uniform prior over all possible continuous states at the root.

Incorporating background-rate variation in the MuSSCRat model does not complicate the computation of the augmented likelihood, since it simply “rescales” the variance-covariance matrices on each branch. However, including background-rate variation does complicate inference; specifically, it causes the MuSSCRat model to become nonidentifiable (see Supplementary Material available on Dryad at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.499c4j2). A model is nonidentifiable when multiple combinations of parameters have identical likelihoods (Rannala 2002). Consequently, parameters of a nonidentifiable model cannot be estimated by standard maximum-likelihood methods because there may be no unique “maximum” likelihood. In this case, it is necessary to apply constraints on nonidentifiable parameters that “penalize” different combinations of parameters that have identical likelihoods. Bayesian models provide a natural solution to nonidentifiability, as the prior distributions on the parameters naturally penalize combinations of parameters that might have identical likelihoods (i.e., the joint posterior probability of parameter combinations with identical likelihoods will differ if their joint prior probabilities are different). We describe our assumed prior distribution on background rates in the next section.

Priors

We assume that the background-rate parameters,  , are drawn from a

hierarchical model with parameters

, are drawn from a

hierarchical model with parameters  and

and

, and the remainder of the parameters

are drawn from independent prior distributions, so that the joint prior density becomes:

, and the remainder of the parameters

are drawn from independent prior distributions, so that the joint prior density becomes:

|

We describe our prior distributions in the following paragraphs; these parameterizations reflect our “baseline” model, but we explore alternative priors and prior sensitivity in our empirical analyses.

We draw the lineage-specific background rates of continuous-character evolution,

, iid from a shared

lognormal distribution with mean

, iid from a shared

lognormal distribution with mean  and standard

deviation

and standard

deviation  . We use a uniform prior on

. We use a uniform prior on

, such that

, such that

is drawn from a

log

is drawn from a

log -uniform distribution between

-uniform distribution between

and

and  . We

draw the standard deviation,

. We

draw the standard deviation,  , from an

exponential distribution with mean

, from an

exponential distribution with mean  . The constant

. The constant

is the standard deviation for a

lognormal distribution that indicates that our

is the standard deviation for a

lognormal distribution that indicates that our  prior belief ranges over one order of magnitude (see Supplementary Material available on

Dryad). This model is the continuous-character analog of the uncorrelated lognormal

(UCLN) relaxed-clock model used to describe variation in rates of molecular evolution

across lineages (e.g., Drummond et al. 2006; Lemey et al. 2010). Accordingly, we refer to this

extension of the MuSSCRat model with background-rate variation as

the MuSSCRat + UCLN model. A convenient property of the UCLN

model is that—as

prior belief ranges over one order of magnitude (see Supplementary Material available on

Dryad). This model is the continuous-character analog of the uncorrelated lognormal

(UCLN) relaxed-clock model used to describe variation in rates of molecular evolution

across lineages (e.g., Drummond et al. 2006; Lemey et al. 2010). Accordingly, we refer to this

extension of the MuSSCRat model with background-rate variation as

the MuSSCRat + UCLN model. A convenient property of the UCLN

model is that—as  shrinks to 0—it collapses to a

“strict” morphological-clock model, where

shrinks to 0—it collapses to a

“strict” morphological-clock model, where  for all

lineages. Our prior on

for all

lineages. Our prior on  specifies that we expect the values

of

specifies that we expect the values

of  to range over about

one order of magnitude, but the exponential prior allows the standard deviation to

shrink to 0 if the data prefer a strict morphological clock. In summary, we specify the

background-rate-variation component of the prior model as:

to range over about

one order of magnitude, but the exponential prior allows the standard deviation to

shrink to 0 if the data prefer a strict morphological clock. In summary, we specify the

background-rate-variation component of the prior model as:

|

The parameter vector  describes the

relative rate of continuous-character evolution for each of the discrete states. We

specify a Dirichlet distribution on half the values of

describes the

relative rate of continuous-character evolution for each of the discrete states. We

specify a Dirichlet distribution on half the values of

. Specifying the

prior on half the values of

. Specifying the

prior on half the values of  ensures that the mean value of

ensures that the mean value of  is

1, which allows us to interpret these parameters as the relative rate

of continuous-character evolution in the alternative discrete states. We assume the

concentration parameters of the Dirichlet distribution are the same, so this is a

symmetric Dirichlet distribution with parameter

is

1, which allows us to interpret these parameters as the relative rate

of continuous-character evolution in the alternative discrete states. We assume the

concentration parameters of the Dirichlet distribution are the same, so this is a

symmetric Dirichlet distribution with parameter  :

:

|

The average rate of change for each of the  continuous characters

may vary; we allow the relative rate of continuous characters to vary by including a

parameter vector,

continuous characters

may vary; we allow the relative rate of continuous characters to vary by including a

parameter vector,  , where

, where

is the rate of evolution of

the

is the rate of evolution of

the  continuous character. We

specify a Dirichlet distribution on

continuous character. We

specify a Dirichlet distribution on  of the

values of

of the

values of  . We adopt the same

logic as above for the prior on

. We adopt the same

logic as above for the prior on  ,

specifying a symmetric Dirichlet distribution with parameter

,

specifying a symmetric Dirichlet distribution with parameter  such that the mean value of

such that the mean value of

is 1:

is 1:

|

The symmetric matrix  determines the evolutionary correlation

between each pair of continuous characters;

determines the evolutionary correlation

between each pair of continuous characters;  is the correlation between characters

is the correlation between characters  and

and

. The matrix

. The matrix  has

a special constraint (it must be positive semidefinite) that makes it difficult to

specify, for example, iid priors on each matrix element,

has

a special constraint (it must be positive semidefinite) that makes it difficult to

specify, for example, iid priors on each matrix element,  . We use the LKJ distribution as a

prior on

. We use the LKJ distribution as a

prior on  , which defines a prior over

positive-semidefinite correlation matrices (Lewandowski

et al. 2009). Correlation matrices drawn from this distribution have prior

density:

, which defines a prior over

positive-semidefinite correlation matrices (Lewandowski

et al. 2009). Correlation matrices drawn from this distribution have prior

density:

|

where  is inversely related to the

variance of the correlation parameters: larger values of

is inversely related to the

variance of the correlation parameters: larger values of  result in marginal distributions on

result in marginal distributions on  that are

concentrated closer to 0, while smaller values of

that are

concentrated closer to 0, while smaller values of  result in distributions that are more diffuse. We choose

result in distributions that are more diffuse. We choose  , which indicates a uniform

distribution over all possible positive-semidefinite correlation matrices:

, which indicates a uniform

distribution over all possible positive-semidefinite correlation matrices:

|

Finally, the matrix  describes the rates of change between

the discrete-character states. We parameterize the stationary frequencies,

describes the rates of change between

the discrete-character states. We parameterize the stationary frequencies,

, and the average rate of

change,

, and the average rate of

change,  . We build

. We build

from these parameters as follows:

from these parameters as follows:

|

where the diagonal elements are specified so that the sum of each row is 0, and the

scalar  is an arbitrary value that guarantees

that the expected number of transitions over a tree of length

is an arbitrary value that guarantees

that the expected number of transitions over a tree of length  is

is

.

.

Assuming that the rates of change are symmetric ( ) or asymmetric

(

) or asymmetric

( ) may have some impact

on our analysis through the distribution on

) may have some impact

on our analysis through the distribution on  .

Moreover, inferring whether rates of change are (a)symmetric is often of direct interest

to researchers studying discrete-character evolution. We therefore specify a mixture

distribution on

.

Moreover, inferring whether rates of change are (a)symmetric is often of direct interest

to researchers studying discrete-character evolution. We therefore specify a mixture

distribution on  , so that

, so that

may be symmetric or

asymmetric. Specifically, we draw

may be symmetric or

asymmetric. Specifically, we draw  , from

a degenerate distribution concentrated on equal rates,

, from

a degenerate distribution concentrated on equal rates,  , with

probability

, with

probability  , and from a Dirichlet

distribution with parameter

, and from a Dirichlet

distribution with parameter  with

probability

with

probability  . We draw

. We draw

from a lognormal prior

distribution with standard deviation

from a lognormal prior

distribution with standard deviation  , and specify the mean

such that the expected number of transitions over the entire phylogeny is

, and specify the mean

such that the expected number of transitions over the entire phylogeny is

. The prior expected number of

transitions reflects an empirical prior, and should be specified differently for

different data sets; for the simulations and analyses we describe later, we use

. The prior expected number of

transitions reflects an empirical prior, and should be specified differently for

different data sets; for the simulations and analyses we describe later, we use

. Our overall prior on

. Our overall prior on

is:

is:

|

Posterior

Having specified the augmented likelihood function and the joint prior density, we can write down the joint posterior density of the model parameters and the discrete-character histories:

|

(1) |

where the first two terms on the right-hand side are the augmented likelihood, and the third term is the joint prior density on the model parameters.

The above Bayesian model conditions on a known tree,  .

It is straightforward to relax the assumption of a fixed tree by including it as a

parameter in the model. In this case, we may include a sequence alignment and specify a

subsitution model, and jointly infer the phylogeny and the parameters of the

MuSSCRat and substitution models.

.

It is straightforward to relax the assumption of a fixed tree by including it as a

parameter in the model. In this case, we may include a sequence alignment and specify a

subsitution model, and jointly infer the phylogeny and the parameters of the

MuSSCRat and substitution models.

Constant background rates

The MuSSCRat model with constant-background rates is nested

within the model with background-rate variation described above: as

, the lognormal prior on

, the lognormal prior on

collapses to a point

centered on

collapses to a point

centered on  (so that all values of

(so that all values of

for all branches

become increasingly similar).

for all branches

become increasingly similar).

To specify the constant-background-rate model explicitly, we draw a single value for

from a

log

from a

log -uniform distribution between

-uniform distribution between

and

and  .

Otherwise, we use the same prior distributions for the constant-background-rate model as

we described for the variable-background-rate model, above.

.

Otherwise, we use the same prior distributions for the constant-background-rate model as

we described for the variable-background-rate model, above.

Markov chain Monte Carlo

The joint posterior probability density cannot be calculated analytically because we

cannot evaluate the normalizing constant of equation 1 (the marginal likelihood). We therefore approximate the joint

posterior probability density numerically using MCMC; specifically, we draw samples from

the joint posterior distribution using the Metropolis–Hastings and Green algorithm

(Metropolis et al. 1953; Hastings 1970; Green 1995). We

use standard proposal distributions for the majority of the model parameters; for

brevity, we only provide details for two of our more uncommon proposal distributions—for

moves between symmetric and asymmetric  matrices, and for the

discrete-character histories—in the Supplementary Material available on Dryad.

matrices, and for the

discrete-character histories—in the Supplementary Material available on Dryad.

Our data-augmentation strategy involves including the complete history of the discrete

character,  , as a variable in the

Markov chain. As such, the MCMC procedure includes proposals that change the

discrete-character history. When a new character history,

, as a variable in the

Markov chain. As such, the MCMC procedure includes proposals that change the

discrete-character history. When a new character history,  , is proposed, it is

accepted with probability

, is proposed, it is

accepted with probability  , computed as:

, computed as:

|

where  is the

distribution from which the new character history is drawn. Note that the probabilities

of the discrete characters,

is the

distribution from which the new character history is drawn. Note that the probabilities

of the discrete characters,  ,

and continuous characters,

,

and continuous characters,  ,

both contribute to the probability that the proposed discrete-character history is

accepted. Importantly, this means that the continuous characters are able to correctly

influence the discrete-character histories; that is, we are correctly modeling the joint

distribution of the discrete and continuous characters.

,

both contribute to the probability that the proposed discrete-character history is

accepted. Importantly, this means that the continuous characters are able to correctly

influence the discrete-character histories; that is, we are correctly modeling the joint

distribution of the discrete and continuous characters.

Implementation

We implemented our MuSSCRat model in the open-source Bayesian phylogenetic software, RevBayes (Höhna et al. 2016). Our implementation relies upon the data-augmentation functionality developed in RevBayes by Michael J. Landis and Sebastian Höhna for discrete characters (unpublished), extended to accommodate phylogenetic uncertainty. Owing to the flexibility of RevBayes, our implementation allows users to explore the impact of binary or multistate discrete traits on rates of continuous-character evolution, provides tremendous flexibility for specifying priors, enables simultaneous inference of ancestral states for both discrete and continuous characters, and allows joint inference of the phylogeny, divergence times, and parameters of the MuSSCRat model. We provide Rev scripts for performing analyses under the MuSSCRat model in RevBayes (see Data Dryad repository http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.499c4j2 and GitHub repository https://github.com/mikeryanmay/musscrat_supp_archive/releases/tag/1.1.

Statistical behavior

The MuSSCRat model has many parameters relative to the number of

observations,  and

and  . It is therefore unclear how well

this complex model can detect rate variation, or distinguish between state-dependent and

background sources of rate variation. Accordingly, we performed a simulation study to

characterize the statistical behavior of the state-dependent model. Specifically, we

performed experiments to understand: 1) its ability to detect state-dependent rate variation

in the absence of background-rate variation; 2) its ability to detect state-dependent rate

variation in the presence of background-rate variation; 3) the cost of including

background-rate variation in the model when background rates are actually constant, and; 4)

the consequences of assuming background rates are constant when they are actually

variable.

. It is therefore unclear how well

this complex model can detect rate variation, or distinguish between state-dependent and

background sources of rate variation. Accordingly, we performed a simulation study to

characterize the statistical behavior of the state-dependent model. Specifically, we

performed experiments to understand: 1) its ability to detect state-dependent rate variation

in the absence of background-rate variation; 2) its ability to detect state-dependent rate

variation in the presence of background-rate variation; 3) the cost of including

background-rate variation in the model when background rates are actually constant, and; 4)

the consequences of assuming background rates are constant when they are actually

variable.

For the following analyses, we approximated the joint posterior probability density by running two replicate MCMC simulations for each simulated data set. We performed MCMC diagnosis to ensure that the joint posterior density was adequately approximated. We provide details of the MCMC simulations and MCMC diagnoses in the Supplementary Material available on Dryad.

Measures of Performance

Frequentist properties

The frequentist interpretation of a Bayesian credible interval (CI) is that the true

value of a parameter has a  chance of being

within the

chance of being

within the  CI of its

corresponding marginal posterior distribution (assuming the model is true, see Huelsenbeck and Rannala 2004). With this

interpretation in mind, we assessed the frequentist properties of the

CI of its

corresponding marginal posterior distribution (assuming the model is true, see Huelsenbeck and Rannala 2004). With this

interpretation in mind, we assessed the frequentist properties of the

CI inferred for our simulated data

sets (assuming the conventional significance level,

CI inferred for our simulated data

sets (assuming the conventional significance level,  ). We define the

coverage probability as the frequency with which the true value of a

parameter is contained in the

). We define the

coverage probability as the frequency with which the true value of a

parameter is contained in the  CI, the

false-positive rate as the frequency with which the true value is

excluded from the

CI, the

false-positive rate as the frequency with which the true value is

excluded from the  CI (one minus the coverage

probability), and the power as the frequency with which a

state-independent model is excluded from the

CI (one minus the coverage

probability), and the power as the frequency with which a

state-independent model is excluded from the  CI when the

state-dependent model is true.

CI when the

state-dependent model is true.

Accuracy and bias

We assess the accuracy and bias of the posterior-mean estimate of

using the percent-error

statistic, defined as:

using the percent-error

statistic, defined as:

|

where  is the true value of

state-dependent rate for discrete state 1, and

is the true value of

state-dependent rate for discrete state 1, and  is estimated value of

the state-dependent rate for discrete state 1 (we use the mean of the corresponding

marginal posterior distribution). Values of

is estimated value of

the state-dependent rate for discrete state 1 (we use the mean of the corresponding

marginal posterior distribution). Values of  indicate an underestimate; conversely, values of

indicate an underestimate; conversely, values of  indicate an

overestimate.

indicate an

overestimate.

Simulation Experiments

Experiment 1: Constant background rates

We simulated data sets of different sizes (with  continuous

characters), over a variety of tree sizes (with

continuous

characters), over a variety of tree sizes (with  species), and

state-dependent rate-ratios,

species), and

state-dependent rate-ratios,  (where

(where  corresponds

to the case when rates do not depend on the state of the discrete trait). For each

combination of

corresponds

to the case when rates do not depend on the state of the discrete trait). For each

combination of  ,

,  , and

, and

, we simulated 100

trees under a constant-rate birth–death process with a speciation rate of 1 and an

extinction rate of 0.5 using the R (R Core Team 2017) package TESS (Höhna et al. 2015); we then rescaled each tree to

have a root height of 1. We simulated discrete-character histories under a symmetric

continuous-time Markov chain with a rate specified such that the expected number of

transitions was 5. We then drew correlation matrices from an LKJ distribution with

, we simulated 100

trees under a constant-rate birth–death process with a speciation rate of 1 and an

extinction rate of 0.5 using the R (R Core Team 2017) package TESS (Höhna et al. 2015); we then rescaled each tree to

have a root height of 1. We simulated discrete-character histories under a symmetric

continuous-time Markov chain with a rate specified such that the expected number of

transitions was 5. We then drew correlation matrices from an LKJ distribution with

, and relative rates for each

continuous character from a symmetric Dirichlet distribution with

, and relative rates for each

continuous character from a symmetric Dirichlet distribution with

. Finally, we simulated

. Finally, we simulated

continuous characters under a

multivariate Brownian motion model assuming a background rate of 1. We provide more

details for the simulation procedure in the Supplementary Material available on

Dryad.

continuous characters under a

multivariate Brownian motion model assuming a background rate of 1. We provide more

details for the simulation procedure in the Supplementary Material available on

Dryad.

We analyzed each simulated data set in RevBayes under the

MuSSCRat model, assuming the true phylogeny was known. We

constrained the model so that the background rate was equal for each lineage (i.e., the

constant-rate model), and excluded the standard deviation parameter,

, from the model. We estimated the

remaining model parameters from the simulated data using the priors described in the

Bayesian inference section, above. Since the generating model and the inference model

both exclude background-rate variation, this simulation scenario reflects the

performance of the method when the model is correctly specified.

, from the model. We estimated the

remaining model parameters from the simulated data using the priors described in the

Bayesian inference section, above. Since the generating model and the inference model

both exclude background-rate variation, this simulation scenario reflects the

performance of the method when the model is correctly specified.

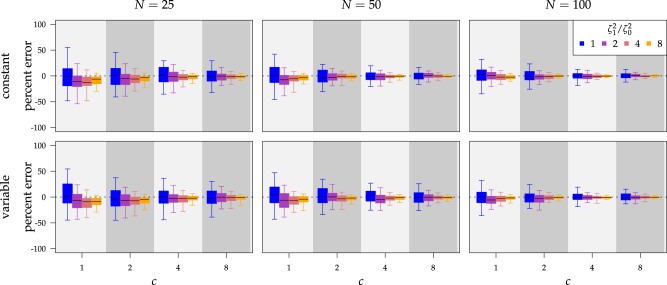

The false-positive rate for this simulation experiment was  (i.e., when

(i.e., when  ; Fig. 3, the top row of the top three panels), which is

indistinguishable from the expected

; Fig. 3, the top row of the top three panels), which is

indistinguishable from the expected  (two-tailed

binomial test

(two-tailed

binomial test  ,

,

). Next, we

computed the power when rates of continuous-character evolution varied among discrete

states (

). Next, we

computed the power when rates of continuous-character evolution varied among discrete

states ( ). The power

ranged from

). The power

ranged from  to

to

from the worst-case to the

best-case scenarios. Predictably, power improved as the number of continuous characters

and species increased; overall, the average power was

from the worst-case to the

best-case scenarios. Predictably, power improved as the number of continuous characters

and species increased; overall, the average power was  (Fig. 3, top three panels, excluding the top

row). The posterior-mean estimate of

(Fig. 3, top three panels, excluding the top

row). The posterior-mean estimate of  was slightly

biased for small numbers of continuous characters (

was slightly

biased for small numbers of continuous characters ( ) but quickly converged to the

true value as the number of characters and species increased (Fig. 4, top row of panels).

) but quickly converged to the

true value as the number of characters and species increased (Fig. 4, top row of panels).

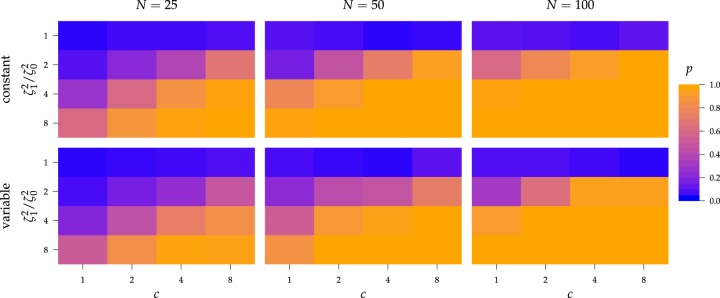

Figure 3.

The frequency with which  was

excluded from the

was

excluded from the  CI when background rates were

constant (top row of panels) or variable (bottom row of panels). Each panel

corresponds to simulations for a given number of species,

CI when background rates were

constant (top row of panels) or variable (bottom row of panels). Each panel

corresponds to simulations for a given number of species,  . Within each panel, rows correspond

to different degrees of state-dependent rate variation,

. Within each panel, rows correspond

to different degrees of state-dependent rate variation,  , and columns

correspond to different numbers of continuous characters,

, and columns

correspond to different numbers of continuous characters,  . Each cell represents the fraction

of the

. Each cell represents the fraction

of the  CI that exclude

CI that exclude

, colored

according to the scale (at right).

, colored

according to the scale (at right).

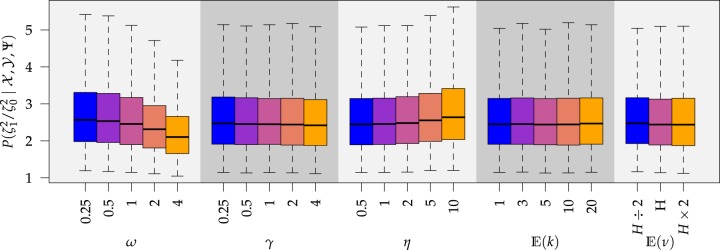

Figure 4.

The percent error of the posterior-mean estimates of  when background rates were

constant (top row of panels) or variable (bottom row of panels). Each column of

panels corresponds to simulations for a given number of species,

when background rates were

constant (top row of panels) or variable (bottom row of panels). Each column of

panels corresponds to simulations for a given number of species,

. Within each panel, boxplots

depict the distribution of percent error across 100 simulated data sets for each of

the

. Within each panel, boxplots

depict the distribution of percent error across 100 simulated data sets for each of

the  continuous characters (along the

x-axis), colored by the true state-dependent rates,

continuous characters (along the

x-axis), colored by the true state-dependent rates,  (see inset

legend). Boxplots represent the middle

(see inset

legend). Boxplots represent the middle  (boxes) and

the middle

(boxes) and

the middle  (whiskers) of simulations.

(whiskers) of simulations.

Experiment 2: Variable background rates

In this simulation scenario, we reused all of the simulated trees, discrete-character

histories, correlation matrices, and relative-rate parameters describing the degree of

variation among continuous characters from the first simulation experiment (with

constant background rates). In this simulation, however, we simulated lineage-specific

rates of continuous-character evolution by drawing the background rate for each lineage,

, from a lognormal distribution

with mean

, from a lognormal distribution

with mean  and standard deviation

and standard deviation

.

.

For this scenario, we analyzed each simulated data set using the

MuSSCRat model with background-rate variation, by allowing

to vary among branches, as

described in the Bayesian inference section (MuSSCRat + UCLN).

Again, this simulation scenario reflects the performance of the method when the model is

correctly specified, since the data-generating model and the inference model both allow

background rates to vary among lineages.

to vary among branches, as

described in the Bayesian inference section (MuSSCRat + UCLN).

Again, this simulation scenario reflects the performance of the method when the model is

correctly specified, since the data-generating model and the inference model both allow

background rates to vary among lineages.

The false-positive rate for this experiment was  (Fig. 3, top row of bottom three panels), again

indistinguishable from the expected

(Fig. 3, top row of bottom three panels), again

indistinguishable from the expected  (two-tailed

binomial test

(two-tailed

binomial test  ,

,  ). The power

was only slightly lower than that of experiment 1: the power was

). The power

was only slightly lower than that of experiment 1: the power was

in the worst case, and

in the worst case, and

in the best case. On average, the

power was

in the best case. On average, the

power was  (Fig. 3, bottom three panels, excluding top row). Again, the posterior-mean

estimate of

(Fig. 3, bottom three panels, excluding top row). Again, the posterior-mean

estimate of  was only modestly biased for

analyses based on a small number of continuous characters (Fig. 4, bottom row of panels).

was only modestly biased for

analyses based on a small number of continuous characters (Fig. 4, bottom row of panels).

Experiment 3: Cost of background-rate variation

When background rates of continuous-character evolution are constant, we expect that

including unnecessary parameters (i.e., to accommodate background-rate variation) in the

inference model should decrease our ability to detect state-dependent rate variation.

The goal of this simulation experiment is to understand the cost of accommodating

background-rate variation when it is absent. To achieve this, we reused the data sets

from Experiment 1 (simulated under constant background rates) with

,

,  , and

, and  ,

but analyzed these data sets under the MuSSCRat + UCLN model.

,

but analyzed these data sets under the MuSSCRat + UCLN model.

For Experiment 1—where we correctly assumed that background rates were constant—the

coverage probability was  (two-tailed binomial test

(two-tailed binomial test

,

,

). By

contrast, in this experiment—when we incorrectly assumed that background rates are

variable—the coverage probability was

). By

contrast, in this experiment—when we incorrectly assumed that background rates are

variable—the coverage probability was  (two-tailed

binomial test

(two-tailed

binomial test  ,

,

). Overall, the

cost of accommodating background-rate variation when absent was therefore quite modest

(

). Overall, the

cost of accommodating background-rate variation when absent was therefore quite modest

( ). Additionally,

the posterior distributions of the background-rate-variation parameter,

). Additionally,

the posterior distributions of the background-rate-variation parameter,

, shrunk strongly toward the true

value,

, shrunk strongly toward the true

value,  (the constant-background-rate

model): the average posterior-mean estimate of

(the constant-background-rate

model): the average posterior-mean estimate of  across these simulations was

across these simulations was  (compared to a prior mean of

(compared to a prior mean of  ; see

Supplementary Material available on Dryad).

; see

Supplementary Material available on Dryad).

Experiment 4: Consequences of ignoring background-rate variation

When background rates of continuous-character evolution vary among lineages, we expect

that excluding background-rate variation from the inference model may

be positively misleading. The goal of this simulation experiment is to understand the

consequences of failing to accommodate background-rate variation on inferences about

state-dependent rates of continuous-character evolution. To achieve this, we reused the

data sets from Experiment 2 (simulated under variable background rates), with

,

,  , and

, and  ,

but analyzed these data sets using the “constrained” MuSSCRat

model (i.e., that assumes a constant background rate of evolution by forcing

,

but analyzed these data sets using the “constrained” MuSSCRat

model (i.e., that assumes a constant background rate of evolution by forcing

to be the same for all

lineages).

to be the same for all

lineages).

For Experiment 2—where we correctly assumed that background rates are variable—the

coverage probability was  (two-tailed binomial test

(two-tailed binomial test

,

,

). By

contrast, in this experiment—when we incorrectly assumed that background rates are

constant—the coverage probability decreased to

). By

contrast, in this experiment—when we incorrectly assumed that background rates are

constant—the coverage probability decreased to  (two-tailed binomial test

(two-tailed binomial test  ,

,

). This

decreased coverage probability implies that we are very confident in the wrong answer

about

). This

decreased coverage probability implies that we are very confident in the wrong answer

about  more often than we should be. For

example, when state-dependent rates are truly equal (

more often than we should be. For

example, when state-dependent rates are truly equal ( ), we will

incorrectly—but confidently—infer that state-dependent rates differ

), we will

incorrectly—but confidently—infer that state-dependent rates differ

of the time.

of the time.

Empirical analyses

Haemulids (grunts) are a group of percomorph fishes that have previously been used to explore state-dependent rates of continuous-character evolution (Price et al. 2013). Specifically, the hypothesis posits that—owing to the increased habitat complexity of reefs—the feeding apparatus (comprising several continuous traits) of reef-dwelling grunt species should evolve at a higher rate than that of their non-reef-dwelling relatives. We revisit this hypothesis by analyzing the haemulid data from Price et al. (2013) under the MuSSCRat model, using a phylogeny estimated from the more extensive molecular data set from Tavera et al. (2018).

Phylogenetic Analyses

We assembled a molecular data set by subsampling the alignments from Tavera et al. (2018) to include only the 49 species represented in our morphological data set. We estimated a chronogram under a partitioned substitution model assuming an uncorrelated lognormal branch-rate prior model and a sampled birth–death node-age prior model. We performed posterior-predictive tests to ensure that the substitution model provided an adequate description of the substitution process. We computed the maximum a posteriori (MAP) chronogram from the posterior distribution of sampled trees and conditioned on this tree in our comparative analyses. We provide details of these analyses in the Supplementary Material available on Dryad.

Comparative Analyses

We analyzed the continuous morphological data under the MuSSCRat model, with habitat type (reef/non-reef) as the discrete character. In these analyses, we conditioned on the MAP chronogram estimated above. We performed a series of analyses to understand: 1) the impact of including or excluding background-rate variation, and; 2) the sensitivity of posterior estimates to the specified priors. For the following analyses, we approximated the joint posterior density by running four replicate MCMC simulations for each analysis using RevBayes. Again, we provide details of the MCMC simulations and MCMC diagnoses in the Supplementary Material available on Dryad.

Character data

We used eight continuous morphological characters related to the feeding apparatus from Price et al. (2013); we included species that also had molecular sequence data from Tavera et al. (2018), resulting in a total of 49 species. The continuous characters include: 1) the mass of the adductor mandibulae muscle; 2) the length of the ascending process of the premaxilla; 3) the length of the longest gill raker; 4) the diameter of the eye; 5) the length of the buccal cavity; 6) the width of the buccal cavity; 7) the height of the head, and; 8) the length of the head. Rather than size correcting these characters, we included body size as an additional character (for a total of nine continuous characters). Following Price et al. (2013), we log-transformed each character before the analyses (and cube-rooted the adductor mass prior to log transformation). We used the habitat data from Price et al. (2013) to score each species for the binary discrete character; we coded non-reef-dwelling species and reef-dwelling species as states 0 and 1, respectively.

Inferring state-dependent rates

To understand the impact of background-rate variation, we estimated the posterior distribution of the MuSSCRat model parameters with and without background-rate variation using the prior settings described in the Bayesian inference section.

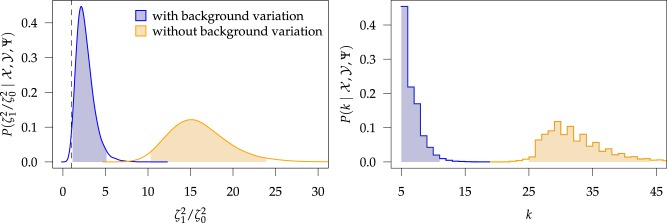

The treatment of background-rate variation had a profound impact on both the

habitat-specific rate of continuous-character evolution, and also on the inferred

history of habitat evolution (Fig. 5). Under the

MuSSCRat model without background-rate variation, we inferred

that the feeding apparatus of reef-dwelling haemulids evolved  times faster than that of

their non-reef-dwelling relatives; under the MuSSCRat + UCLN

model, we inferred a

times faster than that of

their non-reef-dwelling relatives; under the MuSSCRat + UCLN

model, we inferred a  -fold increase in the

evolutionary rate of reef-dwelling species (

-fold increase in the

evolutionary rate of reef-dwelling species ( CIs

CIs

and

and

, respectively).

, respectively).

Figure 5.

At left, the posterior densities (curves) and the  CI (shaded regions) for the

state-dependent rate-ratio,

CI (shaded regions) for the

state-dependent rate-ratio,  , when the

background-rates are constant (orange), or when they vary among lineages (blue),

inferred for the haemulid data set. The dashed vertical line corresponds to

, when the

background-rates are constant (orange), or when they vary among lineages (blue),

inferred for the haemulid data set. The dashed vertical line corresponds to

. At

right, the posterior distribution (lines) and the

. At

right, the posterior distribution (lines) and the  CI (shaded regions) for the number

of habitat transitions,

CI (shaded regions) for the number

of habitat transitions,  , assuming the

background-rates are constant (orange), or vary among lineages (blue).

, assuming the

background-rates are constant (orange), or vary among lineages (blue).

Examining the posterior distribution of habitat transitions reveals that excluding

background-rate variation implies biologically implausible scenarios of habitat

evolution. When we disallowed background-rate variation, we inferred

transitions between reef-

and non-reef habitats across the phylogeny; when we allowed background rates to vary, we

inferred a more reasonable

transitions between reef-

and non-reef habitats across the phylogeny; when we allowed background rates to vary, we

inferred a more reasonable  transitions

(

transitions

( CIs

CIs  and

and  , respectively). The inferred

history of the habitat across the branches of the phylogeny was similarly distorted when

we assumed that background rates did not vary (see Supplementary Material available on

Dryad).

, respectively). The inferred

history of the habitat across the branches of the phylogeny was similarly distorted when

we assumed that background rates did not vary (see Supplementary Material available on

Dryad).

Prior sensitivity

We assessed the prior sensitivity of inferences by performing a series of analyses using different prior values for various parameters of the model. Specifically, we explored the following prior values:

|

where  is the prior expected

standard deviation of the background-rate variation model. We varied a single prior

setting at a time, rather than testing all possible combinations of these priors; we

left the remaining priors as described in the Bayesian inference section, for a total of

23 prior combinations.

is the prior expected

standard deviation of the background-rate variation model. We varied a single prior

setting at a time, rather than testing all possible combinations of these priors; we

left the remaining priors as described in the Bayesian inference section, for a total of

23 prior combinations.

Most prior settings appear to have little impact on the posterior distribution of the

focal parameter,  (Fig. 6). Unsurprisingly, the prior on the focal

parameter,

(Fig. 6). Unsurprisingly, the prior on the focal

parameter,  , had the greatest influence on the

state-dependent rate estimates: the posterior-mean estimate ranged from

, had the greatest influence on the

state-dependent rate estimates: the posterior-mean estimate ranged from

to

to  over the priors that we tested (Fig. 6, left band);

in all cases

over the priors that we tested (Fig. 6, left band);

in all cases  was excluded

from the

was excluded

from the  CI. We discuss the (negligible)

prior sensitivity of the remaining model parameters in the Supplementary Material

available on Dryad.

CI. We discuss the (negligible)

prior sensitivity of the remaining model parameters in the Supplementary Material

available on Dryad.

Figure 6.

The posterior densities of the state-dependent rate-ratio,

, for the

haemulid data set under various priors. Each band of boxplots corresponds to a

different prior-sensitivity experiment. Within each band, boxplots represent the

, for the

haemulid data set under various priors. Each band of boxplots corresponds to a

different prior-sensitivity experiment. Within each band, boxplots represent the

CI (box) and

CI (box) and

CI (whiskers) for the posterior

density under a particular value of that prior.

CI (whiskers) for the posterior

density under a particular value of that prior.

Discussion

Understanding the factors that drive variation in rates of character evolution is a fundamental goal for evolutionary comparative biologists. Current approaches for assessing the influence of a discrete character on rates of continuous-character evolution suffer from two problems: 1) they do not correctly characterize the mutually informative relationship between the discrete and continuous characters, and; 2) they compare against a simple—and likely unrealistic—null model, potentially misleading inferences about state-dependent rates due to rate variation that is unrelated to the discrete character of interest, which we term “background-rate variation”. This second problem is especially concerning, given that rates of evolution are likely to vary greatly across the Tree of Life, and for many reasons not related to the discrete character a particular researcher is investigating.

We present a Bayesian method that deals with both of these issues using a model (MuSSCRat) that correctly integrates over discrete-character histories with extensions that accommodate background-rate variation. This method involves estimating a large number of parameters, especially compared to the size of typical morphological data sets. This raises serious questions about the reliability of inferences made using the method—especially because the background-rate variation model may wash out any signal of state-dependent rate variation—and also about the sensitivity of inferences to the choice of priors. In the following sections, we describe simulation and empirical results that shed light on the statistical behavior of the method.

Statistical behavior under simulation

We explored the ability of the MuSSCRat model to infer state-dependent rates of continuous-character evolution using simulated data. We varied these simulations over the number of species, the number of continuous characters, and the degree of state-dependent rate variation. We repeated our simulations under different background-rate models: “background-constant” simulations, where background rates were the same across lineages, and “background-variable” simulations, where background rates were allowed to vary among lineages.

When the model was correctly specified (i.e., when we inferred parameters under the

true background-rate model), the method had appropriate frequentist behavior: the

false-positive rate was approximately  , and the power

increased with the number of taxa, the number of continuous characters, and the degree

of state-dependent rate variation. The power was modestly reduced for

background-variable simulations (

, and the power

increased with the number of taxa, the number of continuous characters, and the degree

of state-dependent rate variation. The power was modestly reduced for

background-variable simulations ( 74%) compared

to the background-constant simulations (

74%) compared

to the background-constant simulations ( 80%).

Posterior-mean estimates of the state-dependent rate parameters were biased only for

small trees (

80%).

Posterior-mean estimates of the state-dependent rate parameters were biased only for

small trees ( ) or data sets with only one or two

continuous characters. These results suggest that researchers should be able to reliably

infer the state-dependent rate parameters for data sets with a reasonable number of

species and continuous characters.

) or data sets with only one or two

continuous characters. These results suggest that researchers should be able to reliably

infer the state-dependent rate parameters for data sets with a reasonable number of

species and continuous characters.

We also used our simulated data sets to assess the costs of including background-rate

variation, as well as the consequences of ignoring it. Including unnecessary parameters

in the model (overspecification) should lead to increased uncertainty and a concomitant

decrease in power; that is, for background-constant data, allowing for background-rate

variation in the inference model should dampen the signal of state dependence.

Conversely, excluding parameters from the model (underspecification) should lead to

artifactually increased confidence and a higher false-positive rate; that is, for

background-variable data, an inference model that assumes that background rates are

constant may spuriously interpret the unmodeled rate variation as additional evidence

for state dependence. In our simulations, the cost of model overspecification (an

2% decrease in power) was minor

compared to the consequences of model underspecification (an

2% decrease in power) was minor

compared to the consequences of model underspecification (an  10% increase in the false-positive

rate).

10% increase in the false-positive

rate).

Empirical impact of background-rate variation

We reanalyzed the trophic-character data for the haemulids (grunts) from Price et al. (2013) with constant and variable

background rates. The inclusion (or exclusion) of background-rate variation in the