Abstract

Background and objective

Despite advances in surgical techniques and pharmacology, postoperative pain remains a common problem after appendectomy, and its management continues to be suboptimal. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of evening primrose oil on the reduction of postoperative pain after appendectomy.

Materials and methods

In a double-blind, randomized, clinical trial, a total of 80 adults patients with acute appendicitis who were undergoing appendectomy at the Shahid Beheshti Emdad Hospital in Sabzevar, were included. Patients were randomly allocated into two equally sized groups (n = 40). In postoperative period and after recovering from the anesthesia, each of the intervention and control groups received one evening primrose (1000 mg) or placebo capsules every 30 min for 3 times, respectively. All patients in both groups were asked to rate the intensity of their pain on a 0–10 point Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and also McGill pain questionnaire, before and 1 h after the last administration of the drug, postoperatively.

Results

In patients who received evening primrose, both VAS and McGill pain intensity scores significantly decreased after intervention, when compared prior to initiation of the intervention (p < 0.0001). While in the control group, changes of pain intensity scores were not significantly different before and after the intervention (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

It seems that oral evening primrose can be used as a simple and safe potential adjunctive treatment for postoperative pain control after appendectomy.

Keywords: appendectomy, evening primrose, Oenothera biennis, pain, postoperative

1. Introduction

Postoperative pain is one of the most frequent complaints after surgery. Most people experience pain in postoperative periods, for various reasons. It has been shown that despite advances in surgical techniques and pharmacology, up to 75% of patients in surgical wards experience moderate to severe postoperative pain [1–4]. Inappropriate postoperative pain control is associated with patients' dissatisfaction, increased hospital stay and costs, increased morbidity and risk of developing chronic pain [5–11]. Todays, opioids such as meperidine hydrochloride, morphine sulfate and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are among most commonly used medication for postoperative pain management [12–16]. Using these medication is potentially associated with various side effects such as nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, hypotension, sedation and gastrointestinal bleeding, which can consequently lead to insufficient postoperative pain treatment [1,14–16]. Inflammation has been proposed as one of the possible mechanisms of postoperative pain. Therefore, using pharmacologic and medicinal plants with anti-inflammatory activities are reasonable for managing postoperative pain [1,17,18].

Medicinal plants have been commonplace since ancient times, and today they are commonly used in various forms, including herbal plants or their extracts throughout the world [19–21]. Evening primrose is proven to anti-inflammatory effects; increased omega-6 fatty acids; improved vasodilator synthesis; correction of nerve blood flow and nerve conduction velocity defects in diabetic patients. Gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) is one of the essential fatty acids that the body cannot produce and like vitamins, should reach the body through food and supplements. This fatty acid, which is present in evening primrose, increases the production of prostaglandin E1, which has anti-inflammatory effects [22–24]. Since 1970, 1000 tons of this oil has been used daily in different countries, so far no complaints have been reported about its side effects. Also, many clinical trials have shown the beneficial effects of EPO as a source of GLA in cases such as diabetic neuropathy, hypertension, breast pain, premenstrual syndrome, osteoporosis, dementia and hysteroscopy [19,22,25,26].

To the best of our knowledge, despite the promising anti-inflammatory and analgesic effect of evening primrose oil and potential benefit of using evening primrose oil as an adjuvant for postoperative pain management, no published study evaluated its efficacy on postoperative pain.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of evening primrose on postoperative pain after appendectomy.

2. Methods

In a double-blind randomized, clinical trial, a total of 80 patients who were undergoing appendectomy and hospitalized in Emdad Shahid Beheshti Hospital in Sabzevar, Iran, were evaluated from November 2016 to May 2017. After obtaining approval from the institutional ethics committee and written informed consent from the patients, those who meet the inclusion criteria were randomly allocated into two intervention and control groups (n = 40). Inclusion criteria were Class I or II of American Society of Anesthesiologists, aged 25–75 years and weight between 40 and 120 kg. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or lactation, previous history of surgery in the last three years; known systemic or mental psychiatric disorders such as epilepsy or schizophrenia; drugs abuser and receiving more than 2 μg/kg of fentanyl during anesthesia Also, patients treated with steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were excluded from the study.

After surgery, in the presence of consciousness and gag reflex (mean time of 20 min), patients in intervention group received an evening primrose capsule (Natural Life™, Australia) every 30 min for three times, and the control group received a placebo capsule every 30 min for three times as well. One hour after last administration of the drug, patients' pain intensity were evaluated using the visual analog scale (VAS) and McGill Pain Questionnaire. All patients in both groups received Midazolam (0.02 mg/kg) for premedication, fentanyl (2 μg/kg), sodium thiopental (55 μg/kg) and 1.5 μg/kg Aesculin and 0.5 μg/kg Atracurium for induction of anesthesia. In order to maintain anesthesia, 50% Nitrous oxide, 50% oxygen and isoflurane at 1.2 MAC concentrations were given to each patient. In recovery, 1 μg/kg Fentanyl was used to relieve pain. Therefore, all patients in both groups were the same for the drugs received during and after surgery. The patients and the researcher did not know the contents of the capsules (double-blind). The evening primrose capsule contained 1000 mg and placebo capsules contained 1000 mg wheat flour. Before administration of the drugs, an anesthesia nurse who was not aware of the patients' group, evaluated patients' pain intensity and then prescribed capsules as A and B (every 30 min for 3 times) to each group. One hour after the last administration of the drug, the nurse completed the questionnaire and a checklist again. All patients in intervention group were followed for any potential adverse effects of evening primrose oil such as headache, bloating, diarrhea or abdominal pain.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 20 software and Student T-test and Chi-square software.

This study was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials Database (IRCT2017092533202N3).

3. Results

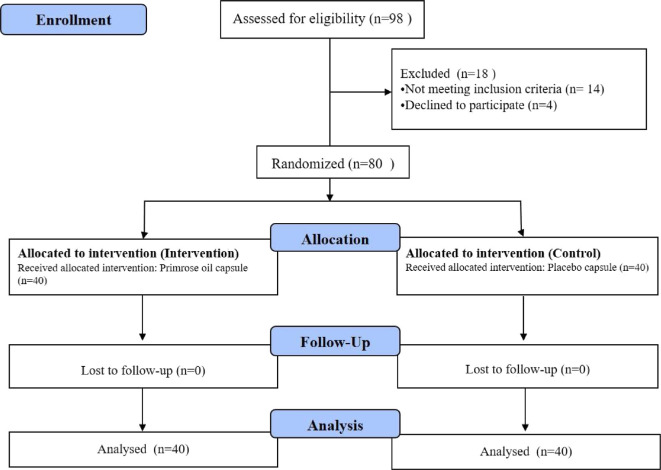

A total of 98 patients were screened during the study period. Of these, 14 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria and 4 patients declined to participate in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study.

The two groups were similar and no significant difference was observed in terms of demographic characteristics and average age. In this study, the mean age of patients was 34 ± 2 years (minimum 21 and maximum 45 years). In terms of gender, 82.5% of the subjects were male and 17.5% were female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients in two groups.

| Variables | Intervention group | Control group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Male; n (%) | 31 (77.5) | 35 (87.5) | 0.34 |

| Female; n (%) | 9 (22.5) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 33.72 ± 2.89 | 35.65 ± 2.32 | 0.19 |

| BMI | 21.8 ± 1.7 | 22.31 ± 1.2 | 0.27 |

BMI= Body Mass Index.

The results of the study showed that the two groups were not statistically significantly different in terms of pain intensity prior to initiation of the intervention. In the postoperative period, the pain intensity (using both VAS and McGill questionnaires) significantly decreased in patients who received evening primrose oil when compared prior to initiation of the intervention; while in the control group the changes of pain intensity after surgery was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of pain in the two groups before and after the intervention.

| Variables | Intervention Group (Evening primrose oil) | Control Group (Placebo) | P- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity before the intervention | VAS | 7/78 ± 0/7 | 8/13 ± 1/2 | 0.63 |

| McGill | 75/60 ± 5/90 | 71/55 ± 3/00 | 0.72 | |

| Pain intensity after the intervention | VAS | 3/88 ± 0/8 | 7/00 ± 8/7 | <0.0001 |

| McGill | 30/13 ± 4/45 | 68/03 ± 5/67 | <0.0001 |

No evening primrose oil-related adverse effects were observed in the study.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effects of evening primrose oil in managing acute postoperative pain. The results of this study showed that using evening primrose oil significantly reduces postoperative pain in patients undergoing appendectomy. It has been previously confirmed that evening primrose can be used to treat many diseases with chronic inflammation [22]. For many years, using evening primrose, as a supplement, has been recommended for treatment of mastalgia [25,27,28]. In a study by Jaafarnejad et al. has been shown that daily using 2000 mg of evening primrose can reduce the duration of breast pain [29]. Additionally, it has been indicated that 6- month usage of 3000 mg of evening primrose oil significantly decreases the intensity of premenstrual cyclical breast discomfort [30]. Another study in women showed that evening primrose oil therapy can significantly decrease and improve premenstrual syndrome symptom severity [31]. Also, Jäntti et al. indicated that twice daily administration of 10 ml evening primrose oil for 12 weeks significantly increases plasma prostaglandins concentration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, however no significant clinical improvement has been reported [32]. Another study by Brzeski et al. showed that using evening primrose oil 6 g/day leads to a mild improvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [33]. A review study by Cameron et al. [34] showed that oils containing GLA (Primrose, borage, or Black Grape Seed Oil) can relieve the symptoms of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Saki, in a study that investigated the effect of evening primrose oil on depression, stated that although the mean score of depression and the patients' performance had been significantly reduced at the beginning of the study, weeks 4, 8, and 12 in both groups (evening primrose oil or nortriptyline therapy), in patients who received evening primrose oil, the decrease was more significant [35]. In a study, which has been conducted on patients with multiple sclerosis, it has been shown that using 1 g of evening primrose oil every 12 h for 3 months can significantly decrease pain and fatigue and also increase their life satisfaction, cognitive function and vitality [36]. SafaaHussain et al. evaluated the effect of evening primrose oil in type 2 diabetic patients. The result of this study showed that administration of three-month evening primrose oil, in combination with conventional treatment, can significantly decrease the level of blood inflammatory markers, improve therapeutic benefits and decrease diabetes related complications [37]. Our patients received 3000 mg of oral evening primrose oil totally during the study period. Some sources consider right daily intake of evening primrose oil about 8 g for adults and 4 g for children [22,23,25,38,39]. In terms of side effects and safety of evening primrose in humans, although it is usually well tolerated and no significant side effects have been documented in the medical literature, it has been recommended that using evening primrose oil during pregnancy should be avoided [14,40].

5. Conclusion

According to the results of this study, it seems that oral evening primrose oil can be used as a simple and safe potential adjunctive treatment for postoperative pain control after appendectomy. However, further well designed study with larger sample size are warranted to evaluate and determine the efficacy and optimal dose of evening primrose oil for managing acute postoperative pain.

References

- 1.Hasanzadeh Kiabi F, Soleimani A, Habibi MR, Emami Zeydi A. Can vitamin C be used as an adjuvant for managing postoperative pain? A short literature review. Kor J Pain. 2013;26(2):209–10. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawal N. Current issues in postoperative pain management. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33(3):160–71. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan TJ. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2287–98. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S144066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuusniemi K, Pöyhiä R. Present-day challenges and future solutions in postoperative pain management: results from PainForum. 2014. J Pain Res. 2016;9:25–36. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S92502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gholipour Baradari A, Firouzian A, Hasanzadeh Kiabi F, Emami Zeydi A, Khademloo M, Nazari Z, et al. Bolus administration of intravenous lidocaine reduces pain after an elective caesarean section: findings from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37(5):566–70. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2016.1264071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinatra R. Causes and consequences of inadequate management of acute pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(12):1859–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan M, Law LS, Gan TJ. Optimizing pain management to facilitate Enhanced Recovery after Surgery pathways. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62(2):203–18. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Samaraee A, Rhind G, Saleh U, Bhattacharya V. Factors contributing to poor post- operative abdominal pain management in adult patients: a review. Surgeon. 2010;8(3):151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Firouzian A, Gholipour Baradari A, Alipour A, Emami Zeydi A, Zamani Kiasari A, Emadi SA, et al. Ultra-low-dose naloxone as an adjuvant to patient controlled analgesia (PCA) with morphine for postoperative pain relief following lumber discectomy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2018;30(1):26–31. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, Rosenberg JM, Bickler S, Brennan T, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American pain society, the American society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine, and the American society of Anesthesiologists' committee on regional anesthesia, executive committee, and administrative council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garimella V, Cellini C. Postoperative pain control. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2013;26(3):191–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harsoor S. Emerging concepts in post-operative pain management. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55(2):101–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonnet F, Marret E. Postoperative pain management and outcome after surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007;21(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo J, Min S. Postoperative pain management in the post-anesthesia care unit: an update. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2687–98. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S142889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyllested M, Jones S, Pedersen JL, Kehlet H. Comparative effect of paracetamol, NSAIDs or their combination in postoperative pain management: a qualitative review. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88(2):199–214. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta A, Bah M. NSAIDs in the treatment of postoperative pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(11):62. doi: 10.1007/s11916-016-0591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Q, Yaksh TL. A brief comparison of the pathophysiology of inflammatory versus neuropathic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24(4):400–7. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834871df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Segelcke D, Schug SA. Postoperative pain-from mechanisms to treatment. Pain Rep. 2017;2(2):e588. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrovska BB. Historical review of medicinal plants' usage. Pharmacogn Rev. 2012;6(11):1–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.95849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forouzanfar F, Hosseinzadeh H. Medicinal herbs in the treatment of neuropathic pain: a review. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2018;21(4):347–58. doi: 10.22038/IJBMS.2018.24026.6021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4:177. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayles B, Usatine R. Evening primrose oil. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(12):1405–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timoszuk M, Bielawska K, Skrzydlewska E. Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) biological activity dependent on chemical composition. Antioxidants (Basel) 2018;7(8):E108. doi: 10.3390/antiox7080108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghasemian M, Owlia S, Owlia MB. Review of anti-inflammatory herbal medicines. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2016;2016:9130979. doi: 10.1155/2016/9130979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stonemetz D. A review of the clinical efficacy of evening primrose. Holist Nurs Pract. 2008;22(3):171–4. doi: 10.1097/01.HNP.0000318026.45527.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vahdat M, Tahermanesh K, Mehdizadeh Kashi A, Ashouri M, Solaymani Dodaran M, Kashanian M, et al. Evening primrose oil effect on the ease of cervical ripening and dilatation before operative hysteroscopy. Thrita. 2015;4(3):e29876. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blommers J, de Lange-De Klerk ES, Kuik DJ, Bezemer PD, Meijer S. Evening primrose oil and fish oil for severe chronic mastalgia: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1389–94. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127377a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma N, Gupta A, Jha PK, Rajput P. Mastalgia cured! Randomized trial comparing centchroman to evening primrose oil. Breast J. 2012;18(5):509–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2012.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaafarnejad F, Adibmoghaddam E, Emami SA, Saki A. Compare the effect of flaxseed, evening primrose oil and Vitamin E on duration of periodic breast pain. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6:85. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_83_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruthi S, Wahner-Roedler DL, Torkelson CJ, Cha SS, Thicke LS, Hazelton JH, Bauer BA. Vitamin E and evening primrose oil for management of cyclical mastalgia: a randomized pilot study. Alternative Med Rev. 2010;15(1):59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tak Fallah L, Najafi A, Fathizadeh N, Khaledian Z. The effect of evening primrose oil on premenstrual syndrome. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2008;16(1):35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jäntti J, Seppälä E, Vapaatalo H, Isomäki H. Evening primrose oil and olive oil in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 1989;8(2):238–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02030080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brzeski M, Madhok R, Capell HA. Evening primrose oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and side-effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30(5):370–2. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/30.5.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cameron M, Gagnier JJ, Chrubasik S. Herbal therapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD002948. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002948.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saki M, Saki K. Effects of evening primrose oil on depression disorders onpatients at psycho-neurological clinic of Khoramabad. J Ilam Univ Med Sci. 2009;16(4):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Majdinasab N, Namjoyan F, Taghizadeh M, Saki H. The effect of evening primrose oil on fatigue and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychiatric Dis Treat. 2018;14:1505–12. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S149403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SafaaHussain M, Abdulridha MK, Khudhair MS. Anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and vasodilating effect of evening primrose oil in type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Pharmaceut Sci Rev Res. 2016;39(2):173–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chung BY, Kim JH, Cho SI, Ahn IS, Kim HO, Park CW, et al. Dose-dependent effects of evening primrose oil in children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25(3):285–91. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bordoni A, Biagi PL, Masi M, Ricci G, Fanelli C, Patrizi A, et al. Evening primrose oil (Efamol) in the treatment of children with atopic eczema. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1988;14(4):291–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jahdi F, Tolouei R, Neisani Samani L, Hashemian M, Haghani H, Mojab F, et al. Effect of evening primrose oil and vitamin b6 on pain control of cyclic mastalgia associated with fibrocystic breast changes: a triple-blind randomized controlled trial. Shiraz E Med J. 2019;20(5):e81243. [Google Scholar]