Highlights

Mandate letters for the current federal government cabinet ministers identify opportunities for intersectoral action on social determinants of health and health equity.

Key areas for intersectoral action identified in 2019 mandate letters include adopting measures of wellbeing in the federal budget, redistributive tax policies, and initiatives in employment, housing, education and other sectors.

Continued monitoring and reporting on health inequalities in Canada is important in assessing progress and identifying areas where intersectoral collaboration can be strengthened.

Introduction

Reducing health inequalities is a globally recognized challenge that requires intersectoral action on determinants of health.1 In Canada, cabinet ministers receive policy objectives from the prime minister in “mandate letters” that outline expectations for their role and identify key priorities for their department. Ministerial mandate letters can be considered a tool for identifying opportunities for such action, as a starting point in the policymaking process. Since most determinants of health lie outside of the health sector,2,3 mandate letters to non–health sector ministers reveal openings where the health sector can support policies that contribute to improving health equity. The following review of 33 mandate letters identifies key commitments outside of the health sector that address the conditions in which people are born, live, grow, work and age— known as the social determinants of health.4 For the majority of commitments highlighted in this review, non-health sectors do not link their directives explicitly to health or its social determinants. This illustrates a well-documented and ongoing challenge to intersectoral action for health: the pursuit of health equity may be considered a lower priority than, or even incompatible with, the policy priorities of other sectors.5 It is anticipated that this review will be of interest to public health and other professionals working across sectors to improve health equity.

Health equity and social determinants of health: windows of opportunity

As part of a commitment to open and transparent government, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s office publicly released ministerial mandate letters for the 29th Canadian Ministry on 13 December, 2019.6 In some cases, mandate letters lay the foundation for intersectoral action on determinants of health by articulating which ministers should work together, on which issues and to what end. A notable example is the upstream directive to the Associate Minister of Finance to incorporate quality of life measurements into federal decision-making and budgeting by working with colleagues from the social development and science sectors.7

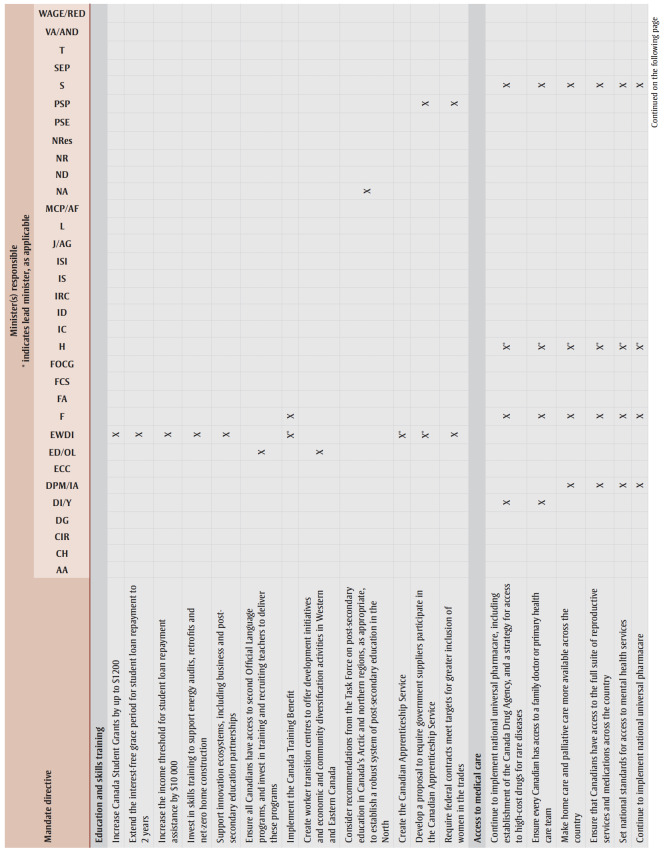

Thematic areas were not determined a priori in this review; letters were reviewed to consider known factors that could shape health and health equity (e.g. the distribution of money, power and resources),8 and grouped according to key determinants, using the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) framework for social determinants of health as a guide.4 Other relevant frameworks (e.g. ecological, commercial and Indigenous determinants of health) were beyond the scope of this review. Comprehensive findings on mandate commitments for the key determinant areas are provided in Table 1. More specifically, Table 1 maps mandate letter commitments to the lead ministers as well as those who are explicitly named in the commitment.

Table 1. Mandate letter directives related to social determinants of health.

The results that follow are intended to show the scope and breadth of commitments related to the social determinants of health in non-health sectors, not to evaluate the positive or negative impacts that such actions may have on health and health inequalities. This report is an analysis of 33 of the 37 letters published; excluded from this review were letters to the Leader and Deputy House Leader of the House of Commons, President of the Privy Council and President of the Treasury Board. Analysis was completed in December 2019 to January 2020, meaning that some policies or programs may have been implemented or redirected since the time of writing (i.e. in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic). As both aspirational policy tools and primary source material, the mandate letters capture a moment in history and the analysis herein illustrates plans for intersectoral action during that time.

Income and employment

Redistributive tax policies and additional supports (e.g. employment security and benefits, enhanced social safety net) can improve determinants of health where they improve access to the resources needed to maintain health, including other determinants—such as employment or income—that are linked with health and well-being.9 In the financial sector, Canada proposed to introduce a new wealth tax on luxury vehicles and will review tax breaks to ensure the wealthy do not benefit unfairly. Middle-class Canadians should receive tax cuts and an increase to the basic personal amount, and the federal minimum wage should be raised to at least $15 per hour. For seniors, enhancements should be made to the Old Age Security pension (an increase of 10% at age 75), and both the Canada Pension Plan and the Quebec Pension Plan (survivor benefits increased by 25%). For new parents, the Canada Child Benefit should be increased for children under one year of age, and the Child Disability Benefit should be doubled. Canada will also seek to better connect eligible seniors and lowincome Canadians to benefits and programs. Addressing income inequality, the recently passed Pay Equity Act10 will require employers to correct gender-based discrimination in compensation, so that employees receive equal compensation for work of equal value in predominantly male and female job classes.

In the area of employment, new benefits should be introduced for seasonal workers and employees who have lost their job due to an employer ceasing operations, and employment services will be offered to military and policing families. The Employment Insurance program should extend sickness benefits, support lost income due to disasters and develop special benefits for new parents.

Racism

Racism influences health at multiple levels through reducing access to positive determinants of health, increasing exposure to risk factors and resulting in adverse physical or mental health outcomes. 11 In the criminal justice sector, all judges in Canada will be required to undergo unconscious bias training and law enforcement will receive access to unconscious bias and cultural competency training. Investments will be made to celebrate and build capacity in Black Canadian communities and support the United Nations (UN) International Decade for People of African Descent. More broadly, the Minister of Diversity, Inclusion and Youth is directed to develop policies that tackle systemic discrimination and anti-Black racism. Across government, departments will work to support self-determination, improve service delivery and advance reconciliation among Indigenous peoples, supported in part through legislation implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Sex and gender

Sex and gender (and related concepts) shape individual and population health by influencing the distribution of health risks, protective factors, access to health services and other determinants.12 In addition to horizontal initiatives, such as gender- based plus and diversity analyses, several other initiatives propose improvements for people who have been disadvantaged because of their sex, gender or sexual orientation. For instance, steps will be taken to ban conversion therapy through amending the Criminal Code and enhance the reach and capacity of LGBTQ2 organizations. Concerning gender-based violence, a response to the Calls for Justice of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls will be developed; free legal advice will be provided to survivors of sexual assault and trauma, with training on these topics delivered to all Canadian judges.

Housing

Housing is a determinant essential to disease prevention on its own and for its influence on other determinants, such as social stability or environment.13 Initiatives to improve the affordability of housing in Canada will include the Canada Housing Benefit, and housing for veterans, as well as the recently implemented First-Time Home Buyer Incentive. The National Housing Strategy will create over 40 000 new units, repair over 200 000 and continue to improve availability through construction and renovation. Steps will also be taken to ensure the needs of seniors, women and girls are reflected in the Strategy, and a new plan will be developed for urban Indigenous housing. Innovative solutions will be explored through implementation of a new competition, the Housing Supply Challenge, which will offer $300 million in prizes.14 Support will also be provided to help Canadians make their homes more energy efficient and climate resistant.

Early childhood

Between the ages of 0 and 6 years, children experience a critical period of physical, cognitive, emotional and social development that impacts well-being in childhood and later in life.15 Steps to improve early childhood will include implementation of a new parental leave for adoptive parents and guaranteed paid leave during a child’s first year of life. New parents will also be able to pause student loan repayments until their youngest child turns 5. Up to 250 000 new spaces for before- and after-school care will be created for children under 10, and the groundwork will be laid for a pan- Canadian childcare services system. For Indigenous communities, new child welfare legislation will come into effect that allows communities to develop policies and laws for child and family services, based on their distinct histories, cultures and circumstances.

Education and skills training

Education and its related determinants (e.g. skills) can shape determinants of health by influencing employment opportunities, decision-making, social position and other pathways.16 To improve the affordability of post-secondary education, Canada Student Grants amounts will be increased, along with the income threshold for student loan repayment assistance. Efforts will be made to ensure First Nations, Inuit and Métis students have support to access and succeed in postsecondary education, as well as students in northern and arctic regions. A new refundable tax credit will be introduced for working Canadians pursuing training, with worker transition centres established to support development in Western and Eastern Canada. Finally, the Canadian Apprenticeship Service will be created to ensure Red Seal apprentices have sufficient opportunities to gain necessary work experience. Youth work experience will be supported through enhancements to both the Youth Employment and Skills Strategy and Canada Summer Jobs program. Job creation underlies many initiatives across government (e.g. infrastructure projects, shipbuilding, new technologies).

International commitments on determinants of health and health equity

Since health inequities are created through the unequal distribution of money, power and resources within and between nations,8 it is important to consider how Canada’s international policy investments address determinants of health. International activities and assistance will maintain a gender equality focus and will champion women’s empowerment, for instance by creating opportunities for poverty reduction among women in developing countries, reducing inequalities in pay among care workers and implementing Canada’s Women, Peace and Security agenda. Implementation of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will continue. This Agenda includes many targets related to determinants of health, including ending poverty and hunger and reducing inequalities.17 Programming will be developed to support sustainable and equitable international development that addresses the intersection of women’s rights with climate adaptation.

New directions for health research

In light of the above review, it is also worth considering opportunities for new research that will support health equity and determinants of health. In health research, a National Institute for Women’s Health Research will be created to tackle gaps in research and care, and will adopt an intersectional approach. Both the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council will implement new grants for studies of race, diversity and gender. Outside of the health sector, the Minister of Diversity and Inclusion and Youth will make research investments for visible minority newcomer women, and finally, the National Research Council of Canada will drive research on challenges such as climate change, clean growth and a healthy society—all factors that shape conditions for health.

This review focussed on federal mandate letters, which can be considered as both a governance structure and governance action for health equity, from the perspective of “health in all policies.”18 As a structure, the letters facilitate collaboration by bringing together intersectoral actors (i.e. ministers) on specific initiatives that may impact health or health equity. As an action, the letters contribute to policy development by setting ministerial agendas and outlining the objectives they are expected to achieve while in office. However, mandate letter objectives are not binding, and while the federal government does track mandate commitments to concrete policy outcomes,19 additional exploration is needed to determine the role of mandate letters in achieving these actions throughout the policy process. This exploration may include assessing how commitments outside of the health sector link to short- and long-term population health improvements, or determining which sectors show leadership and effectiveness in implementing intersectoral initiatives. It may also involve analyzing how commitments evolve from inception to implementation and the factors that lead to sustainable implementation amid changing priorities, mandates, governments and other contextual factors.

Conclusion

This review highlighted a broad range of areas where federal departments will be taking action toward the common goals of social, health and economic well-being in ways that address key social determinants of health, based on the PHAC framework.4 Intersectoral partnerships and collaboration to address determinants such as income, employment, racism and others are paramount to improving health equity, and working together to achieve progress is a key overarching message across mandate letters. PHAC undertakes such work through its partnerships with government and other stakeholders, through its investments in populations that experience health inequalities (e.g. Black Canadians, Indigenous peoples) and through its ongoing efforts to measure and report on health inequalities in Canada.20 Yet, as identified from this review, additional opportunities exist where initiatives outside the health sector can be further explored and leveraged in ways that improve health equity. Lessons learned from promising approaches underway in other jurisdictions (e.g. “health in all policies,” impact assessment) will continue to be monitored with great interest to inform efforts to achieve health equity through intersectoral action.

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the work of those committed to health equity in Canada and abroad, including Nancy Gehlen, Grace Wan Te, and colleagues from the Intersectoral Partnerships and Initiatives team within the Public Health Agency of Canada, who provided thoughtful feedback and editing support on early drafts of this commentary.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authors’ contributions and statement

KL was responsible for the design, conceptualization, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Health equity through intersectoral action: an analysis of 18 country case studies. Available from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/health_equity_isa_2008_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Geneva(CH): Intersectoral action [Internet] Available from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/countrywork/within/isa/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Senate of Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2009. A healthy, productive Canada: a determinant of health approach. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Social determinants of health and health inequalities [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Weinstock D, et al. Reducing health inequities through intersectoral action: balancing equity in health with equity for other social goods. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8((1)):1–3. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Mandate letters [Internet] Available from: https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2019. Minister of Middle Class Prosperity and Associate Minister of Finance Mandate Letter [Internet] Available from: https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2019/12/13/minister-middle-class-prosperity-and-associate-minister-finance-mandate. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva(CH): 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43943/9789241563703_eng.pdf;jsessionid=BB7BA20F9BB0993A92883FB729299C6E?sequence=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael D, nd ed, et al. Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc. Toronto(ON): 2009. Social determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

- 2018, c. C. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/P-4.2/page-1.html. [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One [Internet] :e0138511–3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4580597/#__ffn_sectitle. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa(ON): The Chief Public Health Officer’s report on the state of public health in Canada 2012: influencing health—the importance of sex and gender; pp. influencing health—the importance of sex and gender–3. [Google Scholar]

- St. Francis Xavier University. Antigonish(NS): Housing as a focus for public health action on equity: a curated list [Internet] Available from: http://nccdh.ca/resources/entry/housing-as-a-focus-for-public-health-action-on-equity-a-curated-list. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Housing supply challenge [Internet] Available from: https://impact.canada.ca/en/challenges/housing-supply-challenge. [Google Scholar]

- CCSDH. Ottawa(ON): Implementing multi-sectoral healthy child development initiatives: lessons learned from community-based interventions [Internet] Available from: http://ccsdh.ca/images/uploads/Implementing_Multi-Sectoral_HCD_Initiatives.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Low B, Low D, et al. Education and education policy as social determinants of health. Virtual Mentor. 2006;8((11)):756–61. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.11.pfor1-0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Sustainable Development Agenda [Internet]; New York (NY): United Nations; 2015 [cited 2020 Jan 7] United Nations. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ [Google Scholar]

- McQueen D, Wismar M, Lin V, Jones C, Davies M, et al. Intersectoral governance for health in all policies: structures, actions, and experiences [Internet] WHO on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2012 Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/171707/Intersectoral-governance-for-health-in-all-policies.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Mandate letter tracker: delivering results for Canadians [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/campaigns/mandate-tracker-results-canadians.html. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Key health inequalities in Canada: a national portrait [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/science-research-data/key-health-inequalities-canada-national-portrait-executive-summary.html. [Google Scholar]