Significance Statement

Among patients with CKD, vascular calcification is common and is an independent contributor to increased vascular stiffness and vascular risk. The authors investigated whether supplementation with vitamin K, a cofactor for proteins that inhibit vascular calcification, could improve arterial stiffness in patients with CKD, in a parallel-group, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving patients aged 18 or older with CKD stage 3b or 4. Vitamin K2 supplementation for 12 months did not improve vascular stiffness, as measured by pulse wave velocity. An updated meta-analysis including these new results confirmed a lack of efficacy of vitamin K supplementation on these end points. Longer treatment periods or therapies other than vitamin K may be required to improve vascular calcification and reduce arterial stiffness and cardiovascular risk in patients with CKD.

Keywords: vitamin K, chronic kidney disease, vascular calcification, arterial stiffness

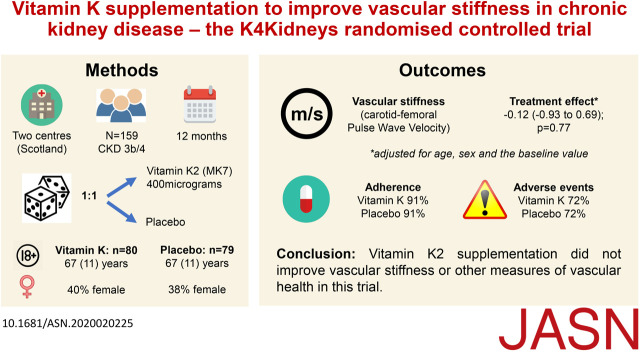

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Vascular calcification, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, is common among patients with CKD and is an independent contributor to increased vascular stiffness and vascular risk in this patient group. Vitamin K is a cofactor for proteins involved in prevention of vascular calcification. Whether or not vitamin K supplementation could improve arterial stiffness in patients with CKD is unknown.

Methods

To determine if vitamin K supplementation might improve arterial stiffness in patients in CKD, we conducted a parallel-group, double-blind, randomized trial in participants aged 18 or older with CKD stage 3b or 4 (eGFR 15–45 ml/min per 1.73 m2). We randomly assigned participants to receive 400 μg oral vitamin K2 or matching placebo once daily for a year. The primary outcome was the adjusted between-group difference in carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included augmentation index, abdominal aortic calcification, BP, physical function, and blood markers of mineral metabolism and vascular health. We also updated a recently published meta-analysis of trials to include the findings of this study.

Results

We included 159 randomized participants in the modified intention-to-treat analysis, with 80 allocated to receive vitamin K and 79 to receive placebo. Mean age was 66 years, 62 (39%) were female, and 87 (55%) had CKD stage 4. We found no differences in pulse wave velocity at 12 months, augmentation index at 12 months, BP, B-type natriuretic peptide, or physical function. The updated meta-analysis showed no effect of vitamin K supplementation on vascular stiffness or vascular calcification measures.

Conclusions

Vitamin K2 supplementation did not improve vascular stiffness or other measures of vascular health in this trial involving individuals with CKD.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number

Vitamin K therapy to improve vascular health in patients with chronic kidney disease, ISRCTN21444964 (www.isrctn.com)

Cardiovascular disease is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with CKD.1 Cardiovascular risk increases with worsening renal function, but risk is substantially increased even in those with moderate CKD; patients with stage 3b CKD have over twice the mortality rate of those without CKD.2 This risk persists despite efforts to control conventional cardiovascular risk factors including BP and lipids.3

Vascular calcification is common in patients with CKD, and the degree of calcification correlates with the severity of renal impairment.4 Calcification of elastic arteries is associated with increased vascular stiffness,5 an important risk factor for cardiovascular events,6 driven by a series of adverse consequences including increased BP, decreased coronary artery perfusion, and the development of left ventricular hypertrophy. The potential importance of vascular calcification is reinforced by analyses showing that it is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events; abdominal aortic calcification is associated with an odds ratio of 1.6 for vascular events after adjustment for conventional risk factors.7

It is now clear that vascular calcification is not a passive process, but is an active, regulated process akin to ectopic new bone formation.8 Vitamin K–dependent proteins are integral to the regulation of this phenomenon. Two important proteins that regulate and prevent vascular calcification, matrix Gla protein (MGP) and Gla-rich protein, require vitamin K as a cofactor for γ-carboxylation—an essential step in their activation.9,10 Other proteins requiring vitamin K for activation, such as osteocalcin and Gas6,11,12 are also involved in bone and mineral metabolism. Vitamin K intake is low for a large proportion of people13 and, for patients with CKD, impaired vitamin K recycling potentially compounds this relative deficiency of vitamin K.14

A recent meta-analysis of observational studies confirmed that higher levels of inactive vitamin K–dependent proteins are associated with higher rates of cardiovascular events and death.15 Few trials of vitamin K have examined the effect of treatment on vascular calcification or stiffness to date, however, meta-analyses of those that have suggest a potential significant benefit on vascular calcification and a nonsignificant reduction in vascular stiffness.15 Only one trial to date has examined whether vitamin K supplementation can improve vascular calcification in patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD.16 This trial did not find a significant difference in coronary artery calcification between the vitamin K and placebo groups, but the trial was small (n=42) and the dose of vitamin K2 was low (90 μg per day); vascular stiffness was not tested as an outcome. The aims of this trial were therefore to provide a robust test of whether 1 year of vitamin K2 supplementation (400 μg per day) improved pulse wave velocity and other markers of cardiometabolic health and mineral metabolism compared with placebo in patients with CKD stages 3b and 4.

Methods

Trial Design

We conducted a parallel-group, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Ethics approval was obtained from the East of Scotland National Health Service (NHS) Research Ethics Committee (approval number 13/ES/0085). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at the screening visit, and the trial was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial sponsors were the University of Dundee and NHS Tayside. Tayside Clinical Trials Unit provided trial management, and the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics (Glasgow, United Kingdom) provided data management and statistical analyses.

Trial Population and Recruitment

Participants were eligible if aged 18 years or over, with CKD stage 3b or 4 (defined as an eGFR of >15 ml/min and <45 ml/min by the CKD–Epidemiology Collaboration [CKD-EPI] equation17). Potential participants were excluded if they were unable to give written informed consent, taking warfarin or had atrial fibrillation, taking vitamin K or had a known contraindication to vitamin K therapy, pregnant, intolerant to soya products, currently enrolled in another trial, or were within 30 days of completing another trial. Participants were recruited via the electronic renal patient records at two large nephrology centers in Scotland and additionally using the NHS Research Scotland SHARE registry (www.registerforshare.org).

Intervention and Comparator

Matching tablets containing either 400 μg of vitamin K2 (MK7 subtype), or placebo, were manufactured and bottled by Legosan AB (Kumla, Sweden), and distributed to sites by Tayside Pharmaceuticals (Dundee, Scotland). The trial product was provided in identical bottles with a unique trial identifier on each bottle to ensure masking to participants, clinicians, and researchers. Participants were asked to take one tablet each day for the 12 months of the trial. No clear evidence exists to favor vitamin K1 or K2, or to favor a particular subtype of vitamin K2.15 However, we used the MK7 subtype of vitamin K2 in a previous trial that suggested possible benefit on vascular stiffness18 and so this subtype was selected for use in this trial, but at a higher dose than was used previously. The dose was selected based on previous work suggesting that vitamin K2 supplementation has dose-dependent effects on undercarboxylation of MGP in patients with CKD at least up to a level of 360 μg per day.19 Adherence was checked by counting returned tablets at each visit, with percentage adherence calculated as follows: (number of tablets actually ingested/number of tablets expected to be ingested)×100.

Randomization and Allocation Concealment

Randomization was performed in a 1:1 ratio by a web-based randomization system, run by the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow, to ensure allocation concealment. A minimization algorithm with a small random element was used to ensure balance across key baseline measures. Minimization factors were study center (Tayside or Glasgow), age (>70 years or ≤70 years), sex, CKD stage (3b or 4), and baseline pulse wave velocity (>9.5 m/s or ≤9.5 m/s). During the course of the trial, a problem with the medication supply for one individual arose which called into question whether the contents of bottles allocated to other participants were correct. All participants who were taking study medication at the time had samples of their medication tested to confirm that the medication they were allocated matched the bottle content list held by the manufacturer. All tested participants except for the index individual were taking study tablets with the correct content. The index individual was removed from the trial and from analysis. For a further 28 individuals who had completed their first 6 month supply of medication, testing could not be carried out because no tablets remained to test; these individuals were removed from the trial and from analysis because it was not possible to know what treatment they had taken. All medication testing and comparison with manufacturing lists was conducted by teams separate from the investigators, research nurses, statisticians, and clinical teams to preserve masking of participants, clinicians, and the study team.

The primary outcome was the between-group difference in pulse wave velocity at 12 months, adjusted for baseline values. We measured pulse wave velocity using the SphygmoCor system (AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia) using measurements of the pulse wave at the carotid and femoral sites.20 We chose to measure pulse wave velocity rather than directly measuring calcification for several reasons. Any significant change in calcification would be expected to cause a change in arterial stiffness,5 but pulse wave velocity, as a marker of arterial stiffness, provides not just structural but also functional information on large arteries. It is an independent risk factor for future cardiovascular events6,21 and requires fewer participants to demonstrate clinically important treatment effects than measures of vascular calcification.22

Secondary Outcomes

We measured a series of other markers of vascular health. Augmentation index was derived from applanation tonometry at the radial artery using the SphygmoCor system (AtCor Medical). We calculated augmentation index expressed as ratio of pressure increase to pulse pressure normalized for a heart rate of 75 beats per minute using the internal SphygmoCor algorithm. Office BP was measured three times in the recumbent position using an OMRON HEM-705 oscillometric device and was recorded as the average of the second and third readings. BP (24 hour) was recorded using the SpaceLabs system (SpaceLabs Healthcare, Snoqualmie, WA), taking half-hourly readings during daytime and hourly readings at nighttime. Mean values derived from the whole 24-hour record are reported.

Renal function was assessed using serum creatinine concentration measured as part of routine NHS clinical care, with eGFR derived using the CKD-EPI equation.18 Urinary protein-creatinine ratio was measured from a spot urine sample at baseline and 12 months. Osteocalcin, Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b, parathyroid hormone, fetuin, fibroblast growth factor-23, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D were measured as markers of bone and mineral metabolism, and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide was measured as a marker of vascular risk. Insulin and glucose were measured and used to calculate insulin resistance using the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance.23 Desphospho-uncarboxylated MGP (dp-ucMGP) was measured as a biologic marker of vitamin K repletion; this marker has previously been shown to correlate with vascular events and is related to the degree of vascular calcification.15 Details of assay manufacturers and coefficients of variation for each blood and urine assay are given in Supplemental Table 1.

We performed lateral abdominal radiography to assess aortic calcification. The degree of calcification was assessed by two independent blinded observers, scoring the degree of calcification on a scale from zero to three for the segments of the abdominal aorta adjacent to each of lumbar vertebrae L1 to L4; this method has previously been shown to correlate with risk factors for uremic calcification.24 Anterior and posterior walls were summed separately, giving a total score from zero to 24 points. Vitamin K–dependent proteins have also been implicated in maintenance of neuromuscular function and bone health, and a previous trial suggested a modest improvement in postural sway with vitamin K supplementation.18 CKD is associated with worse physical performance and with high falls and fracture rates25,26; we therefore assessed markers of muscle function as part of the trial. The Short Physical Performance Battery (a test of lower limb balance, strength, and function that is a powerful predictor of future disability, falls, need for care, and death) was performed,27 along with maximal handgrip strength measured using a Jamar dynamometer.28 Monthly self-completed falls diaries were issued to participants to prospectively record falls.29 All new symptoms or unscheduled healthcare contacts for new problems were recorded as adverse events and coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 16.1. All measurements were conducted by trained research nurses masked to treatment allocation. All outcomes were measured at baseline and at 6 and 12 months with the exception of vascular calcification, which was measured at baseline and 12 months.

Sample Size Calculation

We based our sample size calculation on detecting a 1.0 m/s improvement in pulse wave velocity in the intervention group relative to placebo at 12 months. This degree of improvement corresponds to a reduction in cardiovascular risk of between 6% and 12%.6,21 Our previous data indicated a SD of 2.1 m/s for pulse wave velocity,18 which is consistent with previously published values for pulse wave velocity in patients with CKD.30–32 To achieve a power of 80% with α=0.05 given the above parameters requires 70 patients per group (140 in total). We assumed a dropout of 15% per 12 months, thus the initial target for recruitment was to randomize 166 participants. The sample size was recalculated during the trial to account for individuals withdrawn from the trial as a result of the medication issue discussed above. To ensure adequate power despite these withdrawals, a revised target of 190 randomized participants was set in January 2017.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted according to a prespecified statistical analysis plan. Analyses were conducted using the statistical package SAS (version 9.3). A two-sided P value of <0.05 was taken as significant for all analyses in line with the sample size calculation above. Descriptive statistics were generated for baseline characteristics and for the adverse event data. For the primary outcome, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine the between-group difference at 12 months. Adjustments were made for sex (male/female), continuous age at baseline, study center (Glasgow/Tayside), baseline continuous eGFR, and the baseline primary outcome continuous value. This analysis was repeated for the 6-month data to determine the between-group difference at 6 months, making the same adjustments as for 12 months. To determine the average effect of the treatment over the duration of the study, repeated measures analyses were carried out adjusting for sex, age at baseline, site, and baseline eGFR. For all analyses, the treatment effect estimates along with the 95% confidence intervals were provided. For dp-ucMGP results, values below the threshold of reliable linear assay performance (900 pmol/L) were assigned a value of 900 pmol/L before log transformation and analysis.

For each of the secondary outcomes, the ANCOVA analyses conducted for the primary outcome were repeated to determine the between-group difference in each of the outcomes at 12 and 6 months. Repeated measures analyses for the outcomes were also carried out to determine the average treatment effect over the duration of the study, adjusting for sex, age, study center, baseline eGFR, and the baseline value of the outcome being tested. Because a number of the secondary outcomes were biomarkers, the residual distribution of each outcome was assessed and the outcome data were transformed where necessary before carrying out the analyses. The falls diary data were assessed by comparing the incidence rate of falls between the study arms using a Poisson regression model. A sensitivity analysis using a negative binomial regression model was also performed. The time to first fall was then examined using a Cox proportional hazards model, adjusting for age, sex, study center, and baseline eGFR. Multiple imputation was conducted as a sensitivity analysis to determine the effect of missing data on the primary and secondary outcome analysis results. Ten imputed data sets were created, using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method assuming multivariate normality, based on baseline pulse wave velocity, baseline eGFR, sex, and age at baseline. Thereafter the ten data sets were analyzed separately using ANCOVA to determine the between-group differences at 12 months and the results were combined using SAS PROC MIANALYZE.

Updated Meta-analyses

To assimilate our trial findings with other published trials examining the effect of vitamin K supplementation on vascular stiffness and calcification, we updated our recently published meta-analysis.15 In line with this previous analysis, the percentage change in vascular stiffness score and vascular calcification score for each group was used and combined with scores from other trials using random-effects models in R statistical software (R Studio version 1.0.136), with a sensitivity analysis performed using a fixed-effects model. Revised searches were run until the end of December 2019, using the same search strategy as in our previously published analysis.

Results

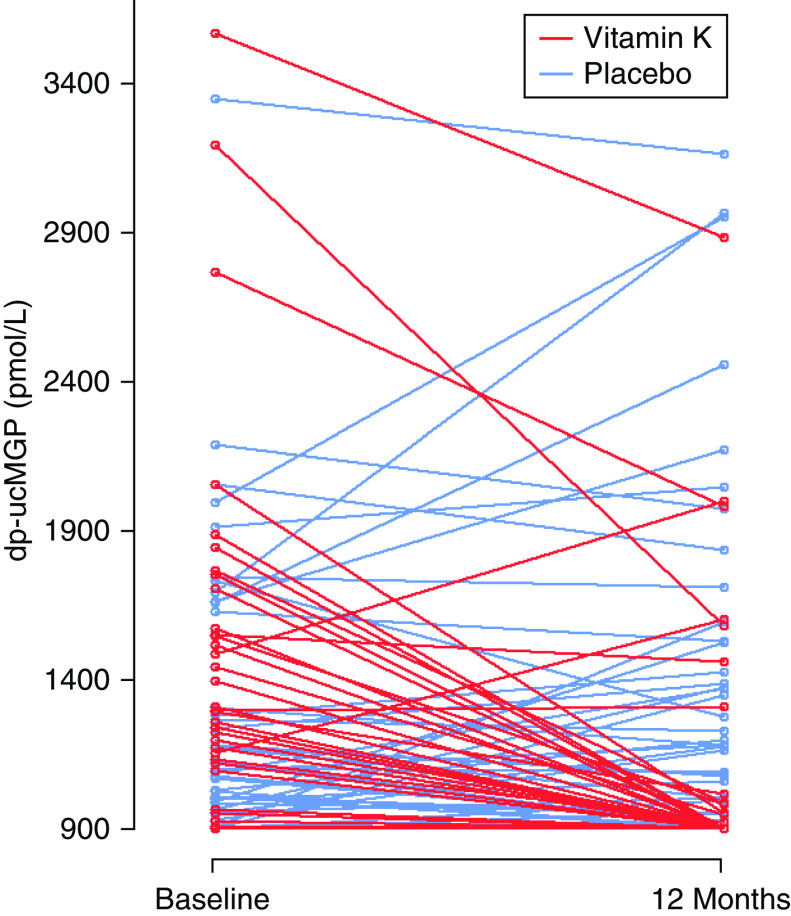

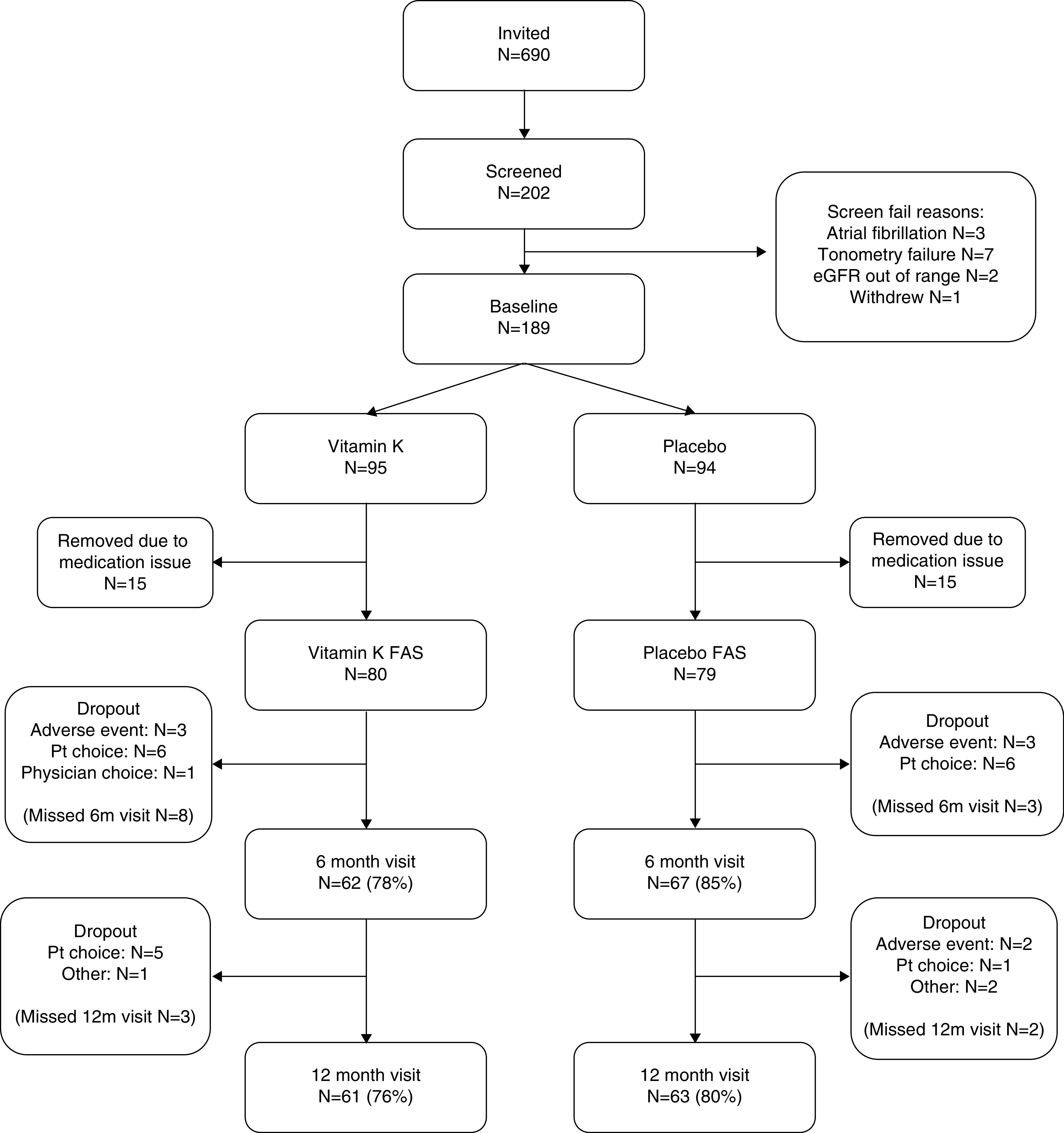

A total of 189 participants were randomized between January 19, 2016 and September 20, 2017. Of these, 30 participants were withdrawn from further participation and from the analysis due to the medication issue described above. The analysis population therefore comprised 159 participants: 80 who received vitamin K and 79 who received placebo. Baseline details are given in Table 1 and participant flow through the trial is shown in Figure 1. The mean adherence to therapy was 91.3% (SD, 11.5) in the vitamin K arm and 90.7% (SD, 14.7) in the placebo arm. Mean log-transformed dp-ucMGP results fell between baseline and 12 months with vitamin K treatment (7.08 versus 6.89) but not in the placebo group (7.01 versus 7.06; treatment effect, −0.20; 95% CI, −0.28 to −0.13; P<0.001). Individual changes in dp-ucMGP are shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of full analysis data set

| Characteristics | Vitamin K (n=80) | Placebo (n=79) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 67.3 (11.0) | 65.7 (13.5) |

| Age >70 yr, n (%) | 35 (44) | 37 (47) |

| Age ≤70 yr, n (%) | 45 (56) | 42 (53) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 32 (40) | 30 (38) |

| White ethnicity, n (%) | 76 (95) | 77 (98) |

| Cause of renal dysfunction, n (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 18 (23) | 13 (17) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (23) | 16 (20) |

| GN | 10 (13) | 8 (10) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 7 (9) | 5 (6) |

| Vascular disease | 5 (6) | 7 (9) |

| Other | 29 (36) | 32 (41) |

| Not known | 5 (6) | 5 (6) |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity, n (%) | ||

| Ischemic heart diseasea | 10 (13) | 15 (19) |

| Stroke | 7 (9) | 7 (9) |

| Heart failure | 1 (1) | 4 (5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 6 (8) | 4 (5) |

| Hypertension | 69 (86) | 63 (80) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (33) | 27 (34) |

| Previous fragility fracture, n (%) | 5 (6) | 3 (4) |

| Walking aids, n (%) | 19 (24) | 12 (15) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 6 (8) | 12 (15) |

| Median number of medications, n (IQR) | 7 (4, 10) | 7 (4, 10) |

| Medication use, n (%) | ||

| ACEi/ARB | 49 (61) | 50 (63) |

| Phosphate binder | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Erythropoietin | 4 (5) | 5 (6) |

| Iron | 12 (15) | 7 (9) |

| Mean eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 (SD) | 29 (8) | 30 (8) |

| CKD stage 3b versus 4, n (%) | 37 versus 43 (46 versus 54) | 35 versus 44 (44 versus 56) |

| Mean pulse wave velocity, m/s (SD) | 11.9 (3.5) | 11.4 (3.2) |

| Mean augmentation index, % (SD) | 26 (11) | 25 (10) |

| Mean office BP, mm Hg (SD) | 147/78 (27/12) | 137/74 (19/10) |

| Mean postural BP drop, mm Hg (SD) | 15/4 (18/8) | 9/3 (18/9) |

| Mean 24-h BP, mm Hg (SD) | 128/69 (16/11) | 130/70 (17/10) |

| Mean Short Physical Performance Battery score (SD) | 9.1 (2.6) | 9.4 (2.6) |

| Mean handgrip strength, kg (SD) | ||

| Males | 31.7 (12.1) | 30.2 (9.8) |

| Females | 14.5 (6.1) | 16.6 (6.1) |

| Median NT-pro-BNP, pg/ml (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 1494 (415, 4133) | 2274 (585, 5801) |

| Median fetuin, ng/ml (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 1237 (1005, 1535) | 1359 (1090, 1847) |

| Median FGF-23, RU/ml (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 170 (126, 255) | 156 (113, 218) |

| Median parathyroid hormone, pmol/L (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 14 (8, 22) | 13 (8,19) |

| Median TRACP-5b, mIU/ml (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 0.41 (0.28, 0.88) | 0.55 (0.30, 1.27) |

| Median osteocalcin, ng/ml (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 37 (24, 62) | 36 (24, 52) |

| Mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D, nmol/L (SD) | 48 (29) | 44 (23) |

| Mean 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D, pmol/L (SD) | 74 (33) | 69 (29) |

| Mean adjusted calcium, mmol/L (SD) | 2.33 (0.11) | 2.33 (0.14) |

| Mean phosphate, mmol/L (SD) | 1.17 (0.19) | 1.18 (0.20) |

| Median HOMA-IR (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 2.36 (1.46, 3.66) | 2.02 (1.44, 3.78) |

| Median urinary protein-creatinine ratio, mg/mmol (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 36 (5141) | 40 (5104) |

| Median aortic calcification score (IQR: Q1, Q3) | 3.5 (0, 9) | 2 (0, 6.5) |

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; IQR, interquartile range; Q1/3, quartile 1/3; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor 23; TRACP-5b, Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance.

Previous myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass grafting, or diagnosis of angina.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. FAS, full analysis set; Pt, participant.

Figure 2.

Individual change in dp-ucMGP levels between baseline and 12 month follow-up.

Table 2 shows the results of the primary outcome analyses. No significant treatment effect was evident at 12 months (the prespecified primary outcome time point), at 6 months, or by repeated measures. Multiple imputation of missing data at 12 months showed no significant treatment effect and therefore did not change the results of the analysis. There was no significant association between change in log-transformed dp-ucMGP between baseline and 12 months and change in pulse wave velocity between baseline and 12 months (Spearman ρ=0.08; 95% CI, −0.11 to 0.26; P=0.42).

Table 2.

Primary outcome: carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (m/s)

| Outcome | n | Vitamin K Mean (SD) | n | Placebo Mean (SD) | Unadjusted Treatment effect (95% CI) | P | Adjusted Treatment effecta (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mo | 57 | 11.7 (3.2) | 63 | 11.1 (3.1) | 0.56 (−0.58 to 1.70) | 0.33 | 0.12 (−0.66 to 0.90) | 0.76 |

| 12 mo | 55 | 11.7 (3.2) | 59 | 11.7 (3.6) | −0.03 (−1.31 to 1.25) | 0.96 | −0.12 (−0.93 to 0.69) | 0.77 |

| Repeated measures | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.01 (−0.66 to 0.68) | 0.98 |

| Multiple imputation (12 mo) | — | — | — | — | — | — | −0.11 (−0.89 to 0.68) | 0.79 |

| Sensitivity analysisb (6 mo) | 70 | 11.6 (3.3) | 78 | 11.1 (3.1) | 0.52 (−0.53 to 1.57) | 0.33 | 0.20 (−0.51 to 0.90) | 0.59 |

Adjusted for age, sex, eGFR, site, and baseline values.

Includes participants removed from main analysis due to uncertainty about medication content.

Secondary vascular and physical performance outcomes are shown in Table 3 and Supplemental Table 2. No effect of treatment was seen on office BP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide, or augmentation index. No significant treatment effect was seen for the Short Physical Performance Battery or for grip strength. The number of participants with at least one fall in each treatment arm was similar; the rate of falls per unit time (the falls rate) was higher in the placebo group, but this was driven by two individuals with very frequent falls. The time to first fall was similar between the two groups: hazard ratio, 0.79 (95% CI, 0.37 to 1.69; P=0.54) as shown in Supplemental Figure 1. A sensitivity analysis removing the two individuals with very high falls rates (74 and 30 falls in 12 months) showed an incident rate ratio for falls of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.41 to 1.40; P=0.38); a further sensitivity analysis using a negative binomial regression model yielded an incident rate ratio of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.34 to 1.87; P=0.60).

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes: vascular and physical function

| Outcome | Vitamin K Mean (SD) | Placebo Mean (SD) | Treatment Effecta (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office systolic BP (mm Hg) | ||||

| 6 mo | 139 (22) | 134 (18) | 0 (−5 to 5) | 0.96 |

| 12 mo | 139 (23) | 137 (21) | −2 (−8 to 4) | 0.58 |

| Repeated measures | 0 (−5 to 4) | 0.86 | ||

| Office diastolic BP (mm Hg) | ||||

| 6 mo | 76 (11) | 74 (10) | 1 (−2 to 3) | 0.65 |

| 12 mo | 75 (10) | 74 (10) | −1 (−4 to 1) | 0.32 |

| Repeated measures | 0 (−3 to 2) | 0.70 | ||

| Augmentation index (%) | ||||

| 6 mo | 24 (10) | 23 (11) | 0 (−2 to 2) | 0.72 |

| 12 mo | 25 (10) | 25 (9) | 0 (−2 to 2) | 0.97 |

| Repeated measures | 0 (−2 to 2) | 0.94 | ||

| Log (NT-pro-BNP [pg/ml]), 12 mo | 7.46 (1.29) | 7.47 (1.53) | 0.10 (−0.20 to 0.39) | 0.51 |

| SPPB | ||||

| 6 mo | 9.3 (2.8) | 9.6 (2.2) | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.7) | 0.71 |

| 12 mo | 9.1 (3.0) | 9.8 (2.2) | −0.4 (−1.0 to 0.3) | 0.29 |

| Repeated measures | −0.1 (−0.6 to 0.4) | 0.74 | ||

| Grip strength (kg) | ||||

| 6 mo | 24.0 (11.6) | 25.5 (10.7) | −0.2 (−1.7 to 1.2) | 0.75 |

| 12 mo | 24.1 (11.9) | 23.8 (10.6) | −0.2 (−2.1 to 1.8) | 0.88 |

| Repeated measures | −0.4 (−1.9 to 1.1) | 0.59 | ||

| Number with at least one fall | 13 | 15 | ||

| Falls per month of fall diary data (falls rate per mo) | 18/759 (0.024) | 128/795 (0.161) | 0.147b (0.090–0.241) | <0.001 |

NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Adjusted for age, sex, eGFR, site, and baseline values.

Incident rate ratio.

Table 4 shows the results of the other secondary outcomes. Osteocalcin levels were significantly lower in the vitamin K group at 12 months compared with placebo, as was insulin resistance. No other significant treatment effects for markers of renal function or bone and mineral metabolism were observed. Table 5 shows adverse events in each group. No difference was seen between vitamin K and placebo in overall numbers of adverse events. Only small numbers of participants died or commenced RRT.

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes: blood and urine measures at 12 mo

| Outcome | Vitamin K Mean (SD) | Placebo Mean (SD) | Treatment Effecta (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 29 (9) | 29 (10) | 0 (−2 to 2) | 0.96 |

| Log (HOMA-IR) | 0.68 (0.79) | 0.90 (1.01) | −0.32 (−0.57 to −0.08) | 0.01 |

| Log (osteocalcin [ng/ml]) | 2.70 (0.77) | 3.62 (0.69) | −0.93 (−1.14 to −0.73) | <0.001 |

| Log (TRACP-5b [mIU/ml]) | −0.88 (1.10) | −0.76 (1.38) | −0.18 (−0.53 to 0.18) | 0.32 |

| Log (PTH [pmol/L]) | 2.46 (0.76) | 2.48 (0.69) | −0.05 (−0.20 to 0.10) | 0.50 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.19 (0.19) | 1.19 (0.21) | 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.07) | 0.83 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.33 (0.11) | 2.32 (0.12) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | 0.61 |

| Log (fetuin [ng/ml]) | 7.14 (0.33) | 7.22 (0.31) | 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.09) | 0.81 |

| Log (FGF-23 [RU/ml]) | 5.33 (0.71) | 5.34 (0.83) | −0.10 (−0.28 to 0.07) | 0.23 |

| Log (25OHD [nmol/L]) | 3.84 (0.63) | 3.75 (0.54) | 0.04 (−0.09 to 0.17) | 0.57 |

| Log (1,25OHD [pmol/L]) | 4.18 (0.51) | 4.14 (0.38) | 0.06 (−0.08 to 0.19) | 0.39 |

| Log (urine P-Cr ratio [mg/mmol]) | 3.85 (1.12) | 3.76 (1.54) | −0.02 (−0.49 to 0.46) | 0.95 |

HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance; TRACP, Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; PTH, parathyroid hormone; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor 23; 25OHD, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25OHD, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; P-Cr, protein-creatinine.

Adjusted for age, sex, eGFR, site, and baseline values.

Table 5.

Number of participants with adverse events by the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities System Order Class, number of deaths, and participants who commenced RRT

| Event | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K (n=95)a | Placebo (n=94) | |

| Any event | 69 (72) | 68 (72) |

| Blood and lymphatic | 3 (3) | 4 (4) |

| Cardiac | 5 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Congenital and genetic | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Ear and labyrinth | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Endocrine | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Eye | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 13 (14) | 12 (13) |

| General | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Hepatobiliary | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Immune system | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Infections and infestations | 29 (31) | 30 (32) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 19 (20) | 14 (15) |

| Investigations | 3 (3) | 9 (10) |

| Metabolism and nutrition | 9 (9) | 4 (4) |

| Musculoskeletal | 8 (8) | 13 (14) |

| Neoplasms | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Nervous system | 5 (5) | 10 (11) |

| Psychiatric | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Renal and urinary | 9 (9) | 6 (6) |

| Reproductive and breast | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory | 4 (4) | 6 (6) |

| Skin | 11 (12) | 4 (4) |

| Surgical/medical procedures | 11 (12) | 9 (10) |

| Vascular | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Deaths | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Commenced RRTb | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

All 189 randomized individuals included in adverse event analysis.

Haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or renal transplant.

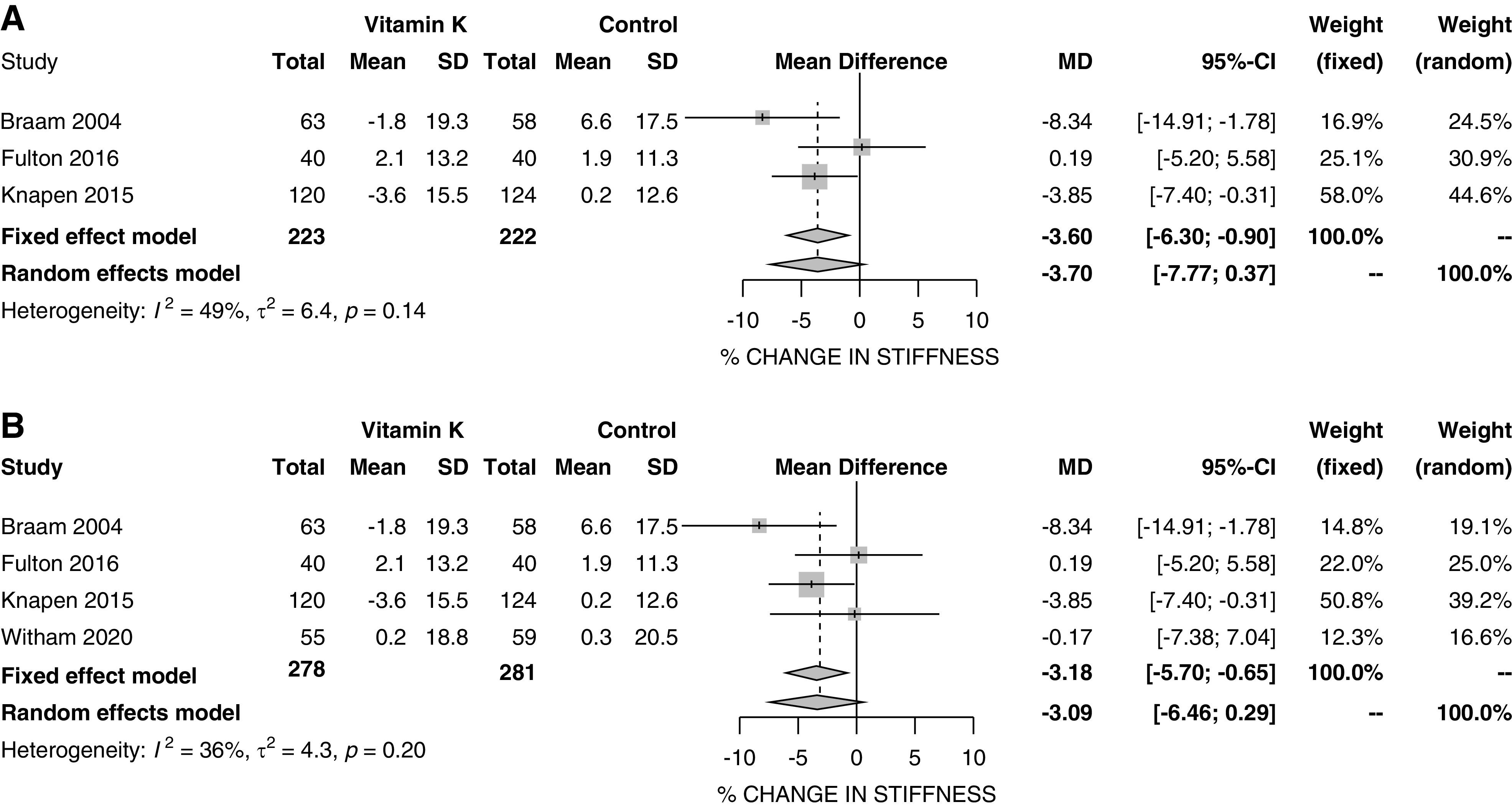

Finally, we combined the results from this study with results for vascular stiffness and for vascular calcification in an update to our recent meta-analysis. Details of the ten (nine plus this trial) included studies16,18,33–39 are given in Supplemental Table 3, and the results are shown in Figure 3 (vascular stiffness) and Supplemental Figure 2 (vascular calcification). Overall, vitamin K produced no significant reduction in vascular stiffness compared with placebo using a random-effects model (−3.1%; 95% CI, −6.5 to 0.3; P=0.07), although a fixed-effects sensitivity analysis showed a marginally significant result (−3.2%; 95% CI, −5.7 to −0.7; P=0.01). Meta-analysis of vascular calcification results (Supplemental Figure 2) showed no reduction in vascular calcification score compared with placebo (−3.3%; 95% CI, −10.4 to 3.7; P=0.37).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of vascular stiffness. (A) Results without current trial; (B) results with current trial.

Discussion

There are extensive preclinical data suggesting that vitamin K–dependent proteins regulate vascular calcification and biologic plausibility that vitamin K supplementation may prevent vascular calcification in patients with advanced CKD. Because vascular calcification is integrally associated with arteriosclerosis characterized by increased pulse wave velocity, we assessed whether vitamin K supplementation reduced or attenuated pulse wave velocity over the course of 12 months in patients with stage 3b or 4 CKD. In summary, in this double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized controlled trial, vitamin K2 had no effect on reducing pulse wave velocity compared with placebo. Furthermore, vitamin K2 therapy did not lead to any improvement in progression of vascular calcification as measured by aortic calcification on lateral abdominal x-ray (AXR) compared with placebo. This is despite good adherence to therapy and evidence of lowering of dp-ucMGP levels—a key marker of vitamin K insufficiency that is associated with vascular calcification—in the vitamin K treatment group. An updated meta-analysis confirmed no significant improvement in either vascular stiffness or vascular calcification with vitamin K supplementation when results from this trial were combined with previous trial results.

There are a number of possible reasons why vitamin K2 supplementation did not improve pulse wave velocity in this trial. It is possible that because arteriosclerosis is challenging to reverse, pulse wave velocity may not be easily amenable to intervention in advanced CKD. This is possible, but other trials have demonstrated that this surrogate parameter is amenable to modification in similar populations, for instance with vitamin D supplementation.40,41 Pulse wave velocity is generally considered a reliable surrogate marker for arteriosclerosis. However, it is not a direct measure of vascular calcification. Although calcification on AXR is less widely used as a marker of vascular calcification than coronary calcification, AXR calcification has been clearly associated with future cardiovascular events in the Framingham studies.42 It is possible that treatment for longer than 12 months is necessary to produce a detectable effect on vascular calcification or on vascular stiffness, phenomena that often progress slowly over many years. A previous trial examining the effect of vitamin K supplementation in postmenopausal women found no effect on vascular stiffness until the third year of treatment.35 However, in this study, vitamin K2 was not associated with improvement in other circulating markers of mineral metabolism such as fetuin-A concentrations, a biomarker implicated in the prevention of vascular calcification.43 The exception was a change in osteocalcin levels in the vitamin K treatment group, but because osteocalcin is itself a vitamin K–dependent protein, the significance of this change in terms of future vascular calcification risk is difficult to interpret. The change in osteocalcin does, however, give additional evidence that vitamin K supplementation was producing actions in vivo consistent with the known biologic roles of vitamin K.

A second possibility is that participants in our trial were vitamin K replete. Although the circulating dp-ucMGP levels in our trial population were lower than those seen in some other populations (e.g., those on hemodialysis38), the fact that dp-ucMGP levels fell further in the vitamin K supplementation group suggests that this group of patients were not replete in vitamin K, although they may still have had levels of active MGP sufficient to inhibit vascular calcification to some extent. We did not attempt to select trial participants on the basis of their vitamin K repletion status; to do so would have required screening participants using the dp-ucMGP assay which is not widely available as a clinical test. It is possible that any treatment effect could have been diluted by recruiting a mixed population of participants who were replete and nonreplete. Future studies could measure dietary vitamin K intake to select participants with particularly low vitamin K intakes. A third possibility is that the dose of vitamin K2 used in our trial was not sufficient to alter vascular calcification or vascular stiffness. We cannot discount this possibility, but we note that higher doses of vitamin K2 (equivalent to 860 μg per day) used in the recent multicentre VALKYRIE trial38 also failed to improve measures of vascular calcification.

Other trials have tested vitamin K2 supplementation in patients with CKD, although the focus for most other trials has been patients undergoing hemodialysis. Recent open-label clinical trials for patients undergoing hemodialysis have also not shown any benefit of vitamin K2 supplementation on aortic calcification in patients on hemodialysis37 and no benefit on coronary calcification in combination with rivaroxaban in patients on hemodialysis previously treated with vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants.38 One short (8 weeks) single-arm, nonrandomized clinical study of vitamin K2 supplementation demonstrated improvement in pulse wave velocity in renal transplant recipients.44 Therefore, our results in advanced nondialysis-dependent CKD are in keeping with other similar trials in patients undergoing dialysis.

Few studies have examined the effect of vitamin K supplementation on measures of physical performance in any population. One small trial suggested a possible benefit on postural sway in older people with vascular disease,18 but a more recent trial, testing a similar dose of vitamin K2 to that used in this trial over 1 year in older people with a history of falls, found no effect on postural sway, falls, or measures of physical performance.45 Our findings are therefore in keeping with this more recent trial. Controversy continues as to whether vitamin K supplementation has a significant effect on bone mineral density or fracture in people with osteoporosis; previous reviews have been clouded by the inclusion of fraudulent trial results. The most recent meta-analysis suggests no significant effect on bone mineral density from vitamin K supplementation but is unable to confirm or exclude a clinically important effect on fracture risk.46

Strengths of our trial include adequate power to detect a relatively small change in pulse wave velocity, the use of more than one center to recruit participants, and the use of a placebo control to ensure masking of outcomes assessments and analyses. However, there are a number of limitations. Despite our trial population having a mean age of 66 years, this is still younger than most patients with CKD stages 3b and 4 seen in clinical practice. Similarly, more men than women took part in the trial, and the trial population was overwhelmingly white. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to older populations, centers with a nonwhite ethnic population, or patients with CKD stage 5. The duration of intervention was limited to 1 year, and it is possible that a longer intervention period would have produced a greater treatment effect; similarly, a higher dose of vitamin K or targeting of those most deficient in vitamin K might have delivered greater improvements. Our method of measuring vascular calcification was relatively crude, and the length of our study is unlikely to have been long enough to demonstrate prevention of progression of calcification; our ability to detect reductions in calcification is limited by the fact that some participants did not have detectable calcification on plain abdominal radiographs. A range of different populations, interventions, and methods of outcome measurement are included in the meta-analysis. This variation is likely to introduce substantial heterogeneity, and these results should be interpreted with caution. We chose to present results using a random-effects analysis for the main estimate, in part because of this expected heterogeneity, and because such analyses tend to the conservative in deriving broader confidence intervals than seen with fixed-effect analyses.

Based on data from our trial and other recent studies, it does not seem likely that vitamin K supplementation is an effective therapy to prevent or reverse vascular calcification. Alternative strategies to address vascular calcification have recently emerged, including a recent clinical trial suggesting that SNF472 (intravenous myo-inositol hexaphosphate), which inhibits formation and growth of hydroxyapatite, attenuates progression of coronary artery calcification in patients on hemodialysis.47 Sodium thiosulfate is often advocated as a treatment for calciphylaxis because it is proposed to mobilize calcium from deposits and forms soluble calcium thiosulfate complexes.48 It has been shown to have some benefits on vascular calcification in patients on dialysis in some studies.49 Other strategies are likely to emerge (for instance manipulating fetuin-A activity) as our understanding of the biology of vascular calcification continues to advance.43

In conclusion, based on our prior assumption that pulse wave velocity is a meaningful surrogate for further cardiovascular events in patients with CKD, our results do not support the hypothesis that administration of vitamin K2 will reduce cardiovascular events in this population. Combining our results with other recent trials does not currently support the conduct of a large cardiovascular outcome trial using vitamin K2 therapy; instead, alternative methods to improve vascular stiffness in patients with CKD should be explored.

Disclosures

J.S. Lees reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. P.B. Mark reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Napp, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Pharmacosmos, and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Vifor, outside the submitted work. E. Rutherford reports grants from Chief Scientist Office, outside the submitted work. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was funded by British Heart Foundation grant PG/14/75/31083 (to P. Mark, A. Struthers, I. Ford, and M. Witham). J. Lees was supported by Kidney Research UK training fellowship TF_013_20161125. E. Rutherford and J. Lees are supported by Chief Scientist Office Scotland Clinical Lectureships. M. Witham acknowledges support from the National Institute for Health Research Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Margaret Band, Dr. Ian Ford, Dr. Roberta L. Fulton, Dr. Roberta C. Littleford, Dr. Patrick B. Mark, Dr. Allan D. Struthers, Dr. Myra White, and Prof. Miles Witham conceived and designed the trial; Dr. Samira Bell, Dr. Roberta L. Fulton, Dr. Patrick B. Mark, Dr. Deborah McGlynn, Dr. Alison Severn, Dr. Nicola Thomson, Dr. Jamie P. Traynor, and Dr. Myra White enrolled participants, collected data, and interpreted clinical data; Dr. Donna J. Chantler, Dr. Gwen Kennedy, and Dr. Maurizio Panarelli analyzed and interpreted laboratory analyses; Dr. Ian Ford and Dr. Kirsty Wetherall led analysis of the trial data; Dr. Jennifer S. Lees led the meta-analysis; Dr. Jennifer S. Lees, Dr. Ian V. McCrea, Dr. Maximilian R. Ralston, and Dr. Elaine Rutherford analyzed and interpreted radiologic images; Dr. Patrick B. Mark and Prof. Miles Witham cowrote the initial report draft; all authors contributed to interpretation of the results, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final submitted version.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2020020225/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Details of assays used in the K4Kidneys trial.

Supplemental Table 2. Vascular calcification results.

Supplemental Table 3. Details of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Supplemental Figure 1. Time to first fall.

Supplemental Figure 2. Forest plots for vascular calcification.

References

- 1.Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, Jafar TH, Heerspink HJ, Mann JF, et al. : Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 382: 339–352, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallan SI, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Mahmoodi BK, Black C, Ishani A, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Age and association of kidney measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease. JAMA 308: 2349–2360, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375: 2073–2081, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temmar M, Liabeuf S, Renard C, Czernichow S, Esper NE, Shahapuni I, et al. : Pulse wave velocity and vascular calcification at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J Hypertens 28: 163–169, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEniery CM, McDonnell BJ, So A, Aitken S, Bolton CE, Munnery M, et al. ; Anglo-Cardiff Collaboration Trial Investigators : Aortic calcification is associated with aortic stiffness and isolated systolic hypertension in healthy individuals. Hypertension 53: 524–531, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Shlomo Y, Spears M, Boustred C, May M, Anderson SG, Benjamin EJ, et al. : Aortic pulse wave velocity improves cardiovascular event prediction: An individual participant meta-analysis of prospective observational data from 17,635 subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol 63: 636–646, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastos Gonçalves F, Voûte MT, Hoeks SE, Chonchol MB, Boersma EE, Stolker RJ, et al. : Calcification of the abdominal aorta as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Heart 98: 988–994, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hruska KA, Mathew S, Saab G: Bone morphogenetic proteins in vascular calcification. Circ Res 97: 105–114, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viegas CS, Rafael MS, Enriquez JL, Teixeira A, Vitorino R, Luís IM, et al. : Gla-rich protein acts as a calcification inhibitor in the human cardiovascular system. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 399–408, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viegas CSB, Santos L, Macedo AL, Matos AA, Silva AP, Neves PL, et al. : Chronic kidney disease circulating calciprotein particles and extracellular vesicles promote vascular calcification: A role for GRP (Gla-Rich Protein). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 38: 575–587, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaesler N, Immendorf S, Ouyang C, Herfs M, Drummen N, Carmeliet P, et al. : Gas6 protein: Its role in cardiovascular calcification. BMC Nephrol 17: 52, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silaghi CN, Ilyés T, Filip VP, Farcaş M, van Ballegooijen AJ, Crăciun AM: Vitamin K dependent proteins in kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci 20: E1571, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thane CW, Bolton-Smith C, Coward WA: Comparative dietary intake and sources of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) among British adults in 1986-7 and 2000-1. Br J Nutr 96: 1105–1115, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaesler N, Magdeleyns E, Herfs M, Schettgen T, Brandenburg V, Fliser D, et al. : Impaired vitamin K recycling in uremia is rescued by vitamin K supplementation. Kidney Int 86: 286–293, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lees JS, Chapman FA, Witham MD, Jardine AG, Mark PB: Vitamin K status, supplementation and vascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 105: 938–945, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurnatowska I, Grzelak P, Masajtis-Zagajewska A, Kaczmarska M, Stefańczyk L, Vermeer C, et al. : Effect of vitamin K2 on progression of atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in nondialyzed patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3-5. Pol Arch Med Wewn 125: 631–640, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. ; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fulton RL, McMurdo ME, Hill A, Abboud RJ, Arnold GP, Struthers AD, et al. : Effect of vitamin K on vascular health and physical function in older people with vascular disease–a randomised controlled trial. J Nutr Health Aging 20: 325–333, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westenfeld R, Krueger T, Schlieper G, Cranenburg EC, Magdeleyns EJ, Heidenreich S, et al. : Effect of vitamin K2 supplementation on functional vitamin K deficiency in hemodialysis patients: A randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 186–195, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, et al. ; European Network for Non-invasive Investigation of Large Arteries : Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: Methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J 27: 2588–2605, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C: Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 1318–1327, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raggi P, Chertow GM, Torres PU, Csiky B, Naso A, Nossuli K, et al. ; ADVANCE Study Group : The ADVANCE study: A randomized study to evaluate the effects of cinacalcet plus low-dose vitamin D on vascular calcification in patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1327–1339, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC: Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28: 412–419, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honkanen E, Kauppila L, Wikström B, Rensma PL, Krzesinski JM, Aasarod K, et al. ; CORD study group : Abdominal aortic calcification in dialysis patients: Results of the CORD study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 4009–4015, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goto NA, Weststrate ACG, Oosterlaan FM, Verhaar MC, Willems HC, Emmelot-Vonk MH, et al. : The association between chronic kidney disease, falls, and fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 31: 13–29, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker SR, Gill K, Macdonald K, Komenda P, Rigatto C, Sood MM, et al. : Association of frailty and physical function in patients with non-dialysis CKD: A systematic review. BMC Nephrol 14: 228, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. : A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 49: M85–M94, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts HC, Denison HJ, Martin HJ, Patel HP, Syddall H, Cooper C, et al. : A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: Towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing 40: 423–429, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamb SE, Jørstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C; Prevention of Falls Network Europe and Outcomes Consensus Group : Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: The prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 1618–1622, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kao MP, Ang DS, Gandy SJ, Nadir MA, Houston JG, Lang CC, et al. : Allopurinol benefits left ventricular mass and endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1382–1389, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Covic A, Haydar AA, Bhamra-Ariza P, Gusbeth-Tatomir P, Goldsmith DJ: Aortic pulse wave velocity and arterial wave reflections predict the extent and severity of coronary artery disease in chronic kidney disease patients. J Nephrol 18: 388–396, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frimodt-Møller M, Kamper AL, Strandgaard S, Kreiner S, Nielsen AH: Beneficial effects on arterial stiffness and pulse-wave reflection of combined enalapril and candesartan in chronic kidney disease--a randomized trial. PLoS One 7: e41757, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braam LA, Hoeks AP, Brouns F, Hamulyák K, Gerichhausen MJ, Vermeer C: Beneficial effects of vitamins D and K on the elastic properties of the vessel wall in postmenopausal women: A follow-up study. Thromb Haemost 91: 373–380, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shea MK, O’Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U, Dallal GE, Dawson-Hughes B, Ordovas JM, et al. : Vitamin K supplementation and progression of coronary artery calcium in older men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 89: 1799–1807, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knapen MH, Braam LA, Drummen NE, Bekers O, Hoeks AP, Vermeer C: Menaquinone-7 supplementation improves arterial stiffness in healthy postmenopausal women. A double-blind randomised clinical trial. Thromb Haemost 113: 1135–1144, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandenburg VM, Reinartz S, Kaesler N, Krüger T, Dirrichs T, Kramann R, et al. : Slower progress of aortic valve calcification with Vitamin K supplementation: Results from a prospective interventional proof-of-concept study. Circulation 135: 2081–2083, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oikonomaki T, Papasotiriou M, Ntrinias T, Kalogeropoulou C, Zabakis P, Kalavrizioti D, et al. : The effect of vitamin K2 supplementation on vascular calcification in haemodialysis patients: A 1-year follow-up randomized trial. Int Urol Nephrol 51: 2037–2044, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Vriese AS, Caluwé R, Pyfferoen L, De Bacquer D, De Boeck K, Delanote J, et al. : Multicenter randomized controlled trial of vitamin K antagonist replacement by rivaroxaban with or without vitamin K2 in hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation: The valkyrie study. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 186–196, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zwakenberg SR, de Jong PA, Bartstra JW, van Asperen R, Westerink J, de Valk H, et al. : The effect of menaquinone-7 supplementation on vascular calcification in patients with diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 110: 883–890, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar V, Yadav AK, Lal A, Kumar V, Singhal M, Billot L, et al. : A randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation on vascular function in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 3100–3108, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levin A, Tang M, Perry T, Zalunardo N, Beaulieu M, Dubland JA, et al. : Randomized controlled trial for the effect of vitamin D supplementation on vascular stiffness in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1447–1460, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witteman JC, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Grobbee DE, Hofman A, D’Agostino RB, et al. : Aortic calcified plaques and cardiovascular disease (the Framingham Study). Am J Cardiol 66: 1060–1064, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bäck M, Aranyi T, Cancela ML, Carracedo M, Conceição N, Leftheriotis G, et al. : Endogenous calcification inhibitors in the prevention of vascular calcification: A consensus statement from the COST action EuroSoftCalcNet. Front Cardiovasc Med 5: 196, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mansour AG, Hariri E, Daaboul Y, Korjian S, El Alam A, Protogerou AD, et al. : Vitamin K2 supplementation and arterial stiffness among renal transplant recipients-a single-arm, single-center clinical trial. J Am Soc Hypertens 11: 589–597, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witham MD, Price RJG, Band MM, Hannah MS, Fulton RL, Clarke CL, et al. : Effect of vitamin K2 on postural sway in older people who fall: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 67: 2102–2107, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mott A, Bradley T, Wright K, Cockayne ES, Shearer MJ, Adamson J, et al. : Effect of vitamin K on bone mineral density and fractures in adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Osteoporos Int 30: 1543–1559, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raggi P, Bellasi A, Bushinsky D, Bover J, Rodriguez M, Ketteler M, et al. : Slowing progression of cardiovascular calcification with SNF472 in patients on hemodialysis: Results of a randomized phase 2b study. Circulation 141: 728–739, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schlieper G, Brandenburg V, Ketteler M, Floege J: Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Nat Rev Nephrol 5: 539–543, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Djuric P, Dimkovic N, Schlieper G, Djuric Z, Pantelic M, Mitrovic M, et al. : Sodium thiosulphate and progression of vascular calcification in end-stage renal disease patients: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 35: 162–169, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.