Abstract

Background

Tests for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are pivotal to detecting current coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and duration of detectable virus indicating potential for infectivity.

Methods

We conducted an individual participant data (IPD) systematic review of longitudinal studies of RT-PCR test results in symptomatic SARS-CoV-2. We searched PubMed, LitCOVID, medRxiv, and COVID-19 Living Evidence databases. We assessed risk of bias using a QUADAS-2 adaptation. Outcomes were the percentage of positive test results by time and the duration of detectable virus, by anatomical sampling sites.

Results

Of 5078 studies screened, we included 32 studies with 1023 SARS-CoV-2 infected participants and 1619 test results, from − 6 to 66 days post-symptom onset and hospitalisation. The highest percentage virus detection was from nasopharyngeal sampling between 0 and 4 days post-symptom onset at 89% (95% confidence interval (CI) 83 to 93) dropping to 54% (95% CI 47 to 61) after 10 to 14 days. On average, duration of detectable virus was longer with lower respiratory tract (LRT) sampling than upper respiratory tract (URT). Duration of faecal and respiratory tract virus detection varied greatly within individual participants. In some participants, virus was still detectable at 46 days post-symptom onset.

Conclusions

RT-PCR misses detection of people with SARS-CoV-2 infection; early sampling minimises false negative diagnoses. Beyond 10 days post-symptom onset, lower RT or faecal testing may be preferred sampling sites. The included studies are open to substantial risk of bias, so the positivity rates are probably overestimated.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, RT-PCR, COVID-19, QUADAS-2, Diagnostic test, Anatomical sampling, IPD, Duration virus detection, Systematic review

Background

Accurate testing is pivotal to controlling severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), otherwise known as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Considerable political and medical emphasis has been placed on rapid access to testing both to identify infected individuals so as to direct appropriate therapy, appropriate return to work, and to implement containment measures to limit the spread of disease. However, success depends heavily on test accuracy. Understanding when in the disease course the virus is detectable is important for two purposes, firstly to understand when and how to detect SARS-CoV-2, and secondly to understand how long individuals are likely to remain infective posing a risk to others.

The success of COVID-19 testing depends heavily on the use of accurate tests at the appropriate time. Testing for active virus infection relies predominantly on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which detects viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) that is shed in varying amounts from different anatomical sites and at different times during the disease course. It is increasingly understood that differences in virus load impact directly on diagnostic accuracy, notably giving rise to negative tests in disease-positive individuals [1, 2].

Positivity is contingent upon sufficient virus being present to trigger a positive test which may depend on test site, sampling methods, and timing [3]. For example, it is believed that positive nasopharyngeal RT-PCR declines within a week of symptoms so that a positive test later in the disease course is more likely from sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or stool [4]. Nomenclature for anatomical site is also unclear, with a wide variety of overlapping terms used such as “oral”, “throat”, “nasal”, “pharyngeal”, and “nasopharyngeal”.

Because testing is pivotal to management and containment of COVID-19, we performed an individual participant data (IPD) systematic review of emerging evidence about test accuracy by anatomical sampling site to inform optimal sampling strategies for SARS-CoV-2. We aimed to examine at what time points during SARS-CoV-2 infection it is detectable at different anatomical sites using RT-PCR-based tests.

Methods

This IPD systematic review followed the recommendations of the PRISMA-IPD checklist [5].

Eligibility

Eligible articles were any case series or longitudinal studies reporting participants with confirmed COVID-19 tested at multiple times during their infection and provided IPD for RT-PCR test results at these times. We stipulated that test timings were linked to index dates of time since symptom onset or time since hospital admission as well as COVID-19 diagnosis by positive RT-PCR and/or suggestive clinical criteria, for example World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines [6].

Search strategy and article selection

Search strings were designed and conducted subsequently in PubMed, LitCOVID, and medRxiv by an experienced information specialist (NR). The search end date was 24 April 2020. We additionally included references identified by COVID-19: National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) living map of living evidence (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/COVID19_MAP/covid_map_v4.html), COVID-19 Living Evidence (https://ispmbern.github.io/covid-19/living-review/) with a volunteer citizen science team, “The Virus Bashers” (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Data extraction

Data were extracted into pre-specified forms. We did not contact authors for additional information. Study, participant characteristics, and ROB were extracted in Microsoft Excel (KG, JS, SG, JA, AW, SM). Data included country, setting, date, number of participants and IPD participants, inclusion criteria, IPD selection, participant age, sample types, RT-PCR test type and equipment, and primers. RT-PCR test results were extracted using Microsoft Access (SM, BS, JP, ZZ, CH).

Risk of bias

We could not identify an ideal risk of bias (ROB) tool for longitudinal studies of diagnostic tests, so we adapted the risk of bias tool for diagnostic accuracy studies QUADAS-2 [7] to include additional signalling questions to cover anticipated issues. ROB signalling questions, evaluation criteria, and domain assessment of potential bias are reported (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Sampling method and grouping

Details of sampling sites and methods, including location of the sampling site(s) and any sample grouping (for example, if combined throat and nasal swabs), were extracted from full texts by a clinician (NS) with queries referred to a second clinician (ST). If stated, details of sampling methodology were recorded, including who collected samples, information regarding anatomical location (e.g. how the nasopharynx was identified), and sample storage (Additional file 1: Table S3).

RT-PCR test result conversion to binary results

IPD RT-PCR results were extracted from each article and converted to binary results (“positive” or “negative”). Data from Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were extracted using Web digitizer [8] (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Data analysis

Days since symptom onset and days since hospital admission were calculated from reported IPD. Data were presented collated across 5-day time intervals for each sample method, with longer times grouped within the longest time interval, and 95% CI was calculated for proportions. For comparison of duration of positive RT-PCR from respiratory tract (RT) and faecal samples, analysis and graphical presentation were restricted to participants sampled by both methods. Data analysis used STATA (14.2 StataCorp LP, Texas, USA) (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Results

Included studies

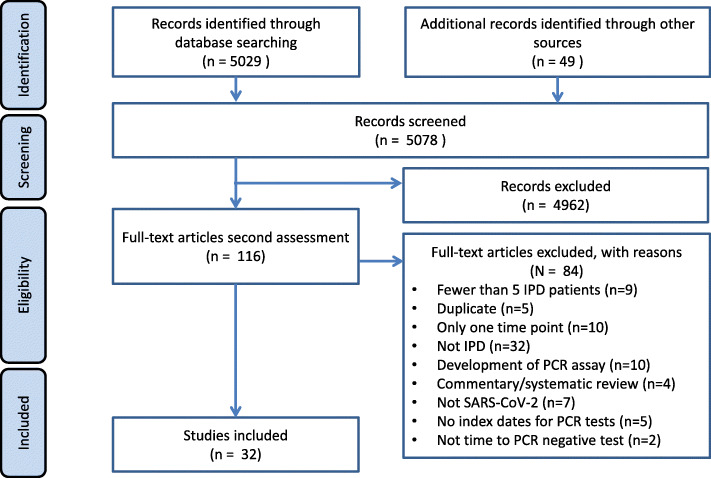

A total of 5078 articles were identified, 116 full text articles were screened, and 32 articles were included [9–40] (Fig. 1). Most articles were from China, in hospitalised adult participants (Table 1). Articles reported on a total of 1023 participants and 1619 test results.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Table 1.

Study characteristics of study design

| Ref | Author year | Country | Location | Setting | Date recruited | No. of participants in study | No. of IPD participants | Study design | Inclusion criteria: reference test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | Cai 2020a | China | Wenzhou | Community | 18 December 2019–12 February 2020 | 35 | 34 | Contact tracing, all patients visited a shopping mall (confirmed COVID-19 cases that had contact with each other) | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [16] | Chang 2020 | China | PLA General Hospital, Beijing | Hospital | 28 January 2020 to 9 February 2020 | 16 | 16 | Confirmed COVID-19 patients released from the Treatment Center of PLA General Hospital | Positive RT-PCR test from throat swabs |

| [10] | Chen 2020a | China | Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University | Hospital | 20 January to 27 February | 133 | 22 | Retrospectively identified a convenience sample of patients admitted to hospital | At least 2 positive RT-PCR test pharyngeal swabs |

| [12] | Chen 2020b | China | Shanghai, Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center. | Public Health Clinical Center | 20 January 2020 to 6 February 2020 | 249 | 248 | Retrospective cohort of laboratory confirmed cases | Positive RT-PCR test according to WHO interim guidelines |

| [29] | He 2020 | China | Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital, Guangzhou, China | Hospital | 21 January 2020 to 14 February 2020 | 94 | 19 | All admitted COVID confirmed cases admitted to hospital | At least one positive RT-PCR test throat sample |

| [24] | Hu 2020a | China | Qingdao, Shandong | Hospital | 29 January 2020 to 12 March 2020 | 59 | 59 | Retrospective cohort of confirmed hospital cases | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [30] | Hu 2020b | China | Second Hospital of Nanjing, China | Hospital | 28 January 2020 to 9 February 2020 | 24 | 23 | Initial asymptomatic patients | Positive RT-PCR test and/or positive CT |

| [28] | Cai 2020b | China | Shanghai, China | Hospital | 19 January 2020 to 3 February 2020 | 10 | 10 | 10 children admitted to hospital | Positive RT-PCR test nasopharyngeal or throat swab |

| [31] | Kujawski 2020 | USA | Multiple sites, USA | Community | 20 January 2020 to 5 February 2020 | 12 | 12 | First 12 patients confirmed SARS-CoV-2 positive in the USA | Positive RT-PCR test in ≥ 1 specimen from a patient. Confirmed by CDC |

| [39] | Lavezzo 2020 | Italy | Padua, Veneto region, Italy | Community | 21 February 2020 to 7 March 2020 | 2812 | 80 | Epidemiological study of entire population of Vo’, Italy, during complete closure of population movement | Positive RT-PCR test on nasopharyngeal swab |

| [27] | Lescure 2020 | France | Paris, Bordeaux | Hospital | 24 January 2020 to 29 January 2020 | 5 | 5 | First 5 patients in France, exposed to COVID-19 in Hubei Province, China, prior to travel to France | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [34] | Li 2020 | China | Xuzhou | Community | 13 January 2020 to 17 February 2020 | 7 | 7 | Asymptomatic contact tracing | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [14] | Liu 2020a | China | Hospital of Nanchang University | Hospital | 21 January 2020 to 4 February 2020 | 76 | 25 | Patients admitted to the hospital | Positive RT-PCR test from nasal swabs |

| [32] | Liu 2020b | China | Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou | Hospital | 22 January 2020 to 11 February 2020 | 10 | 10 | Hospital admission | Two consecutive positive RT-PCR tests |

| [18] | Lo 2020 | China | Centro Hospitalar Conde de Sao Januario, Macau SAR, China | Hospital | 21 January 2020 to 16 February 2020 | 10 | 10 | Retrospective study of first 10 COVID-confirmed patients in Macau | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [20] | Lu 2020 | China | Nantong, Nantong Third Hospital | Hospital | 23 January 2020 to 6 March 2020 | 36 | 35 | Retrospective analysis of clinical patients with fever, coughing, or lung inflammation | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [19] | Song 2020 | China | Wuhan No. 1 Hospital, Nanjing Medical University | Hospital | 31 January to 14 March 2020 | 13 | 13 | Confirmed by CT images | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [13] | To 2020 | China (Hong Kong) | Public Health Lab services branch in Hong Kong | Public Health Lab | Not reported | 12 | 12 | 12 patients who presented with fever and acute respiratory distress, or pneumonia, and travel to Wuhan 14 days before onset of symptoms | Positive RT-PCR test from nasopharyngeal or sputum sample |

| [17] | Wolfel 2020 | Germany | Munich, Germany | Hospital | Not reported | 9 | 9 | Patients that acquired infections upon known close contact to an index case (part of a larger cluster of epidemiologically linked cases that occurred after 23 January 2020 in Munich, Germany) | Positive RT-PCR test from oro- or nasopharyngeal swab |

| [37] | Wu 2020 | China | Zhuhai, Guangdong | Hospital | 16 January 2020 to 15 March 2020 | 74 | 41 | Retrospective study of hospitalised patients | Positive RT-PCR test in two sequential respiratory tract samples |

| [40] | Wyllie 2020 | USA | New Haven, CT | Community (healthcare workers) | Not reported to 5 April 2020 | 98 (44 inpatients) | 19 | Study of inpatients (44) and healthcare workers (98) | Positive RT-PCR test by nasopharyngeal swab or saliva |

| [21] | Xia 2020 | China | Zhejiang | Hospital | 26 January 2020 to 9 February 2020 | 30 | 30 | A prospective interventional case series study of confirmed novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP) patients at hospital | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [23] | Xiao 2020 | China | Tongji Hospital, Huazhong, Wuhan | Hospital | 21 January 2020 to 12 February 2020 | 56 | 56 | 30 confirmed novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP) patients were selected | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [33] | Xu 2020a | China | Changzhou | Hospital | 23 January 2020 to 27 February 2020 | 51 | 48 | Hospital admission including 12 family clusters | Confirmed COVID-19 by Chinese diagnosis and treatment guideline |

| [36] | Xu 2020b | China | Guangzhou, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center | Hospital but from community surveillance | 22 January 2020 to 20 February 2020 | 10 | 10 | “Highly suspected” children with contact with confirmed COVID-19 person, or member of infected family group who was placed in quarantine | Positive RT-PCR test from nasopharyngeal or rectal swabs |

| [11] | Yang 2020 | China | Shenzhen Third People’s | Hospital | 11 January and 3 February 2020 | 213 | 13 | COVID-19 positive hospitalised patients | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [26] | Young 2020 | Singapore | 4 hospitals in Singapore | Hospital | 23 January 2020 to 3 February 2020 | 18 | 18 | Contact tracing. First hospitalised patients in Singapore | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [22] | Yuan 2020 | China | Fifth Affiliated Hospital, Zhuhai, Guangdong Province, China | Hospital | Late January | 6 | 6 | Case series | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [25] | Zhang 2020a | China | Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital, CAS Key Laboratory of Special Pathogens | Hospital | Not reported | Unclear | 16 | Prospective cohort patients | Positive RT-PCR test from oral swab |

| [35] | Zhang 2020b | China | Guangdong | Hospital | 30 January 2020 to 5 February 2020 | 7 | 7 | Prior hospitalisation for COVID-19, discharged under quarantine and subsequently positive by RT-PCR again | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [38] | Zheng 2020 | China | Zheijang, China | Hospital | 19 January 2020 to 15 February 2020 | 96 | 96 | Retrospective cohort of 96 consecutively confirmed hospital cases | Positive RT-PCR test |

| [15] | Zou 2020 | China | Zhuhai, Guangdong | Community and hospital | 7 January to 26 January 2020 | 18 | 17 | 2 family clusters of patients infected by SARS-CoV | Positive RT-PCR test. Assay from Chinese CDC |

Twenty-six (81%) articles reported data on test results since the start of symptoms, and 23 (72%) since hospital admission. Sixteen studies including 22% (229/1023) of the participants reported both these time points: The median time between symptom onset and hospitalisation was 5 days (interquartile range (IQR) 2 to 7 days). The median number of participants per study was 22 (IQR 9 to 56, range 5 to 232), and the median number of RT-PCR test results per participant was 4 (IQR 2 to 9) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study characteristics of IPD participant, sample site, and test type

| Ref | Author year | How were IPD participants selected? | Percentage of male | Age median (years) | Age mean (years) | Age range (years) | Sample site | PCR test type; name of equipment if reported | Genomic targets; primers reported/referenced/ included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | Cai 2020 | IPD of almost all patients in study | NR | NR | NR | NR | Not reported | qRT-PCR; not reported | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported |

| [16] | Chang 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 69 | 36 | Not reported | IQR 24–43 | Throat | qRT-PCR; not reported | Not reported; not reported |

| [10] | Chen 2020a | Initial or follow-up positive sputum or faecal samples paired with a follow-up negative pharyngeal sample | 64 | 37 | 37 | IQR 30–49 | Faeces, sputum, URT (pharyngeal) | qRT-PCR; not reported | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported |

| [12] | Chen 2020b | IPD of all patients in study | 51 | 51 | IQR 36–64 | URT | qRT-PCR; not reported | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported | |

| [29] | He 2020 | IPD for all 94 patients presented, but could only extract 19 IPD from overlapping graphs | 50 | 47 | Throat | qRT-PCR; not reported | N-gene; not reported | ||

| [24] | Hu 2020a | IPD of all patients in study | 48 | 46 | NR | NR | Nasopharyngeal | qRT-PCR; not reported | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported |

| [30] | Hu 2020b | IPD of almost all patients in study | 33 | 33 | 38 | 5–95 | Throat | qRT-PCR; BGI Genomics | ORF1ab; primers included |

| [28] | Jiehao 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 40 | 7 | 6 | 3 months–11 years | URT | qRT-PCR; not reported | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported |

| [31] | Kujawski 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 67 | 53 | 21–68 | Throat, nasopharyngeal, sputum, urine, faeces | qRT-PCR; not reported | N-gene; not reported | |

| [39] | Lavezzo 2020 | All residents identified with infection | 50 | NR | NR | NR | Nasopharyngeal | qRT-PCR; One Step Real Time kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) | E-gene, RdRp; primers referenced |

| [27] | Lescure 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 60 | 46 | 47 | 30–80 | Nasopharyngeal, faeces, conjunctiva, urine, blood, LRT (pleural) | qRT-PCR; not reported | E-gene, RdRp; primers included |

| [34] | Li 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 57 | 42 | 43 | 21–62 | Throat | qRT-PCR; not reported | Not reported; not reported |

| [14] | Liu 2020a | 25 participants with serial samples tested for PCR | NR | NA | NA | NA | Nasopharyngeal | qRT-PCR; not reported | Not reported; not reported |

| [32] | Liu 2020b | IPD of all patients in study | 40 | 42 | 34–50 | Mixed URT (nasal, throat) | qRT-PCR; not reported | E-gene, RdRp, N-gene; not reported | |

| [18] | Lo 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 30 | 54 | NR | NR | Faeces, nasopharyngeal, urine | qRT-PCR; BioGerm | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported |

| [20] | Lu 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | NR | NR | NR | NR | Sputum, URT (pharyngeal), faeces, blood | qRT-PCR; not reported | ORF1ab, N-gene; primers included |

| [19] | Song 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 100 | NR | NR | 22–67 | URT (pharyngeal) | qRT-PCR; Huirui biotechnology | Not reported; not reported |

| [13] | To 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 58 | 63 | 37 to 75 | Saliva | qRT-PCR; QuantiNova SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) | S-gene; not reported | |

| [17] | Wolfel 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | NR | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Sputum, faeces, URT (pharyngeal) | qRT-PCR; Tib-Molbiol, Germany | E-gene, RdRp; not reported |

| [37] | Wu 2020 | Retrospective 41 patients with positive faecal samples only | 53 | NR | NR | NR | Throat, faeces | qRT-PCR; 2019-nCOV Real Time RT-PCR kit (LifeRiver Ltd) | E-gene, RdRp, N-gene |

| [40] | Wyllie 2020 | Patients with multiple nasopharyngeal swabs or multiple saliva swabs | Inpatients (52), healthcare workers (16) | NR | 61 | 23–92 | Nasopharyngeal, saliva | qRT-PCR; US CDC RT-PCR primer/probe sets | N-gene; primers referenced |

| [21] | Xia 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 70 | 51 | 55 | 13–83 | Sputum, conjunctiva | qRT-PCR; BioGerm | Not reported; not reported |

| [23] | Xiao 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 61 | 55 | 55 | 25–83 | URT (pharyngeal) | qRT-PCR; Shanghai Huirui Biotechnology Co. | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported |

| [33] | Xu 2020a | IPD of almost all patients in study | 49 | 3 groups: imported 35 [29–51], secondary 37 [24–47.5], tertiary 53 [35–65] | 24–65 | Throat | qRT-PCR; BioGerm | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported | |

| [36] | Xu 2020b | IPD of all patients in study | 60 | 7 | 8 | 2 months–16 years | Nasopharyngeal, faeces | qRT-PCR; BioGerm | ORF1ab, N-gene; primers included |

| [11] | Yang 2020 | Not reported how 13 patients for serial sampling IPD data chosen | 51 | 52 | 2–86 | Mixed URT (nasal swabs, throat swabs) and mixed LRT (sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)) | qRT-PCR; GeneoDX Co. | Not reported; not reported | |

| [26] | Young 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 50 | 47 | 31–73 | Nasopharyngeal, faeces, urine, blood | qRT-PCR; not reported | ORF1ab, N-gene, S-gene; primers included | |

| [22] | Yuan 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 33 | 64 | 59 | 36–71 | Nasopharyngeal, faeces | qRT-PCR; not reported | E-gene, RdRp, N-gene; not reported |

| [25] | Zhang 2020a | Not reported | NR | NR | NR | NR | URT (oral), faeces | qRT-PCR; HiScript®II One Step qRT-PCR SYBR®Green Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co.) | S-gene; primer included |

| [35] | Zhang 2020b | IPD of all patients in study | 86 | 26 | 22 | 10 months–35 years | Throat, faeces, blood | qRT-PCR; not reported | Not reported; not reported |

| [38] | Zheng 2020 | IPD of all patients in study | 60 | 55 | NR | NR | Sputum, faeces, blood | qRT-PCR; SARS-CoV-2 detection kit (BoJie Shanghai) | ORF1ab; not reported |

| [15] | Zou 2020 | IPD of almost all patients in study | 50 | 59 | 26–76 | Throat, URT (nasal) | qRT-PCR; not reported | ORF1ab, N-gene; not reported |

Sampling site reporting

Articles variably specified sampling sites according to anatomical location, or grouped more than one site for analysis, for example as upper RT (Additional file 1: Table S4). The most frequent sample sites were faeces (n = 13), nasopharyngeal (n = 10), and throat (n = 9), although there was a range of other sites including blood, urine, semen, and conjunctival swabs (Table 2). Details of sampling method were generally absent. Two studies specified the person taking the samples. One study described how the nasopharynx was identified and the swab technique (length of contact time with the nasopharynx and twisting). Five studies specified sample storage and transport details.

Sampling site positivity over time

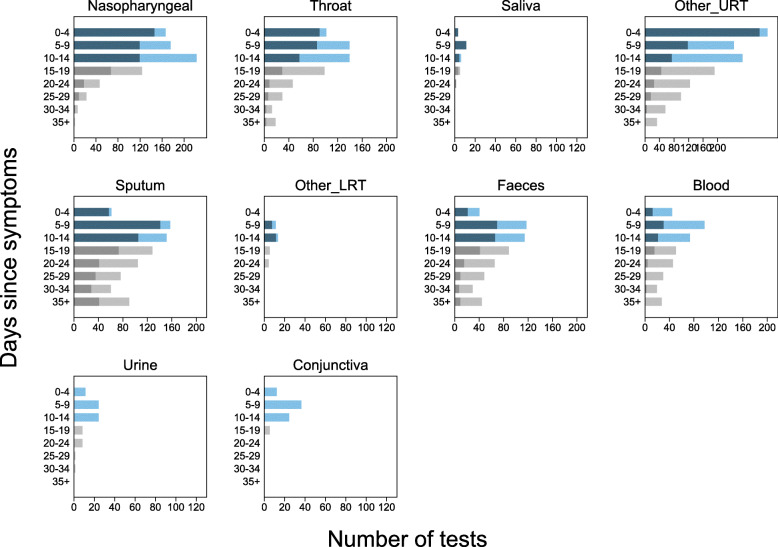

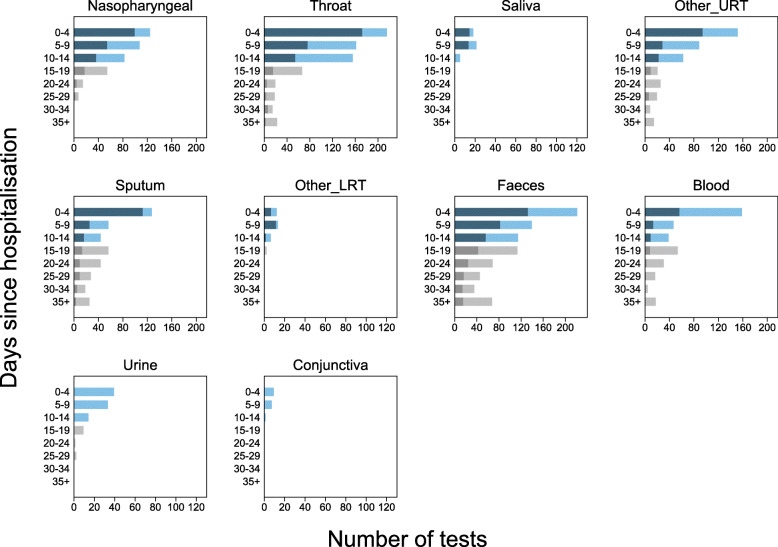

We present RT-PCR test results for 11 different sampling sites at different times during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Figures 2 and 3 show the number of positive and negative RT-PCR results for 5-day time intervals since symptom onset and time from hospital admission, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Number of positive and negative RT-PCR test results since symptom onset. Each panel shows a separate site used in participant sampling. Nasopharyngeal, saliva, and sputum were used where clearly reported. Throat included throat and oropharyngeal. Other URT includes samples reported in articles as nasal, mixed nasal and throat, oral, pharyngeal, or upper respiratory tract. For pharyngeal sampling, it was not clear if this was nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal. Other LRT includes sampling reported as lower respiratory tract or one article including pleural fluid sampling. Blood included serum, plasma, or blood. Faeces included stool or anal swab. Each panel shows 5-day time periods since the onset of symptoms: 0–4 days, 5–9 days, 10–14 days, 15–19 days, 20–25 days, 26–30 days, 31–34 days, and 35 to max days. The numbers of positive RT-PCR tests are shown as dark blue bars and dark grey bars from 0 to 14 days and 15 to 40 days, respectively, and the number of negative RT-PCR results is shown similarly as light blue bars and light grey bars. Different colours are used before and after 15 days to indicate caution, as after 15 days testing is enriched in more severely ill participants. The total number of tests within a particular time period can be read from the x-axis

Fig. 3.

Number of positive and negative RT-PCR test results since hospital admission. Each panel shows a separate site used in participant sampling. Nasopharyngeal, saliva, and sputum were used where clearly reported. Throat included throat and oropharyngeal. Other URT includes samples reported in articles as nasal, mixed nasal and throat, oral, pharyngeal, or upper respiratory tract. For pharyngeal sampling, it was not clear if this was nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal. Other LRT includes sampling reported as lower respiratory tract or one article including pleural fluid sampling. Blood included serum, plasma, or blood. Faeces included stool or anal swab. Each panel shows 5-day time periods since the hospital admission: 0–4 days, 5–9 days, 10–14 days, 15–19 days, 20–25 days, 26–30 days, 31–34 days, and 35 to max days. The numbers of positive RT-PCR tests are shown as dark blue bars and dark grey bars from 0 to 14 days and 15 to 40 days, respectively, and the number of negative RT-PCR results is shown similarly as light blue bars and light grey bars. Different colours are used before and after 15 days to indicate caution, as after 15 days testing is enriched in more severely ill participants. The total number of tests within a particular time period can be read from the x-axis

The sampling sites yielding the greatest proportion of positive tests were nasopharyngeal, throat, sputum, or faeces. Insufficient data were available to evaluate saliva and semen. Only 33% of participants who were tested with blood samples had detectable virus (44/133; 6 articles [20, 26, 27, 31, 35, 38]), and almost no samples tested from urine or conjunctival sampling detected virus presence.

Using nasopharyngeal sampling, 89% (147/166, 95% CI 83 to 93) RT-PCR test results were positive from 0 to 4 days post-symptom onset and 81% (100/124, 95% CI 73 to 87) 0 to 4 days post-hospital admission (Figs. 2 and 3). At 10 to 14 days, the percentage of test results positive reduced to 54% (120/222, 95% CI 47 to 61) post-symptoms and 45% (37/82, 95% CI 34 to 57) post-admission (Additional file 1: Figures S6 and S7).

Using throat sampling at 0 to 4 days post-symptoms, 90% (91/101, 95% CI 83 to 95) of test results from participants with SARS-CoV-2 were detected by RT-PCR sampling, falling to 42% (58/139, 95% CI 33 to 50) at 10 to 14 days post-symptom onset (Fig. 2, Additional File 1: Figures S6 and S7). Similar results were observed for time since hospital admission, where at 0 to 4 days 80% (173/215, 95% CI 75 to 86) of result were positive, falling to 35% (55/155, 95% CI 28 to 44) between 10 and 14 days (Fig. 3, Additional file 1: Figures S6 and S7). Using faecal sampling, 55% test results are positive (22/40, 95% CI 38 to 71) at 0 to 4 days post-symptom onset.

Upper and lower respiratory tract sampling

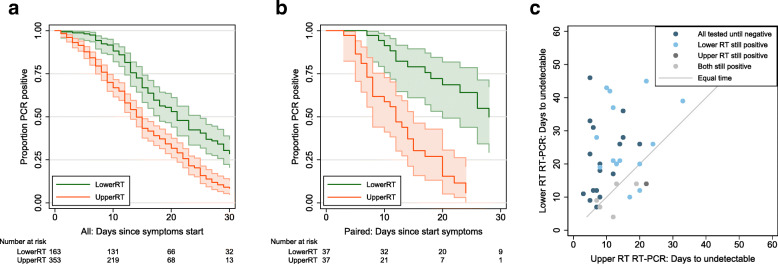

We further grouped sites into upper (URT) and lower (LRT) respiratory tract. The rate of sample positivity reduced faster from URT sites compared to LRT sites (Fig. 4a). Given that analysis across all participants is likely to be influenced by preferential URT sampling of participants with less severe disease, we also analysed participants who underwent both URT and LRT sampling. Again, URT sites on average cleared faster (median 12 days, 95% CI 8 to 15 days) than LRT sites (median 28 days, 95% CI 20 to not estimable; Fig. 4b); the majority of participants clear virus from URT site before LRT (Fig. 4c). Data based on time since hospital admission are consistent with data for time since symptom onset.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of duration of detectable virus from upper and lower respiratory tract sampling. a Time to undetectable virus in upper and lower respiratory tract samples. Kaplan-Meier with 95% confidence intervals and number at risk. All samples in review. b Time to undetectable virus in upper and lower respiratory tract samples in participants who were tested with both upper and lower respiratory tract sampling. Kaplan-Meier with 95% confidence intervals and number at risk. Restricted to participants with both sampling methods. c Time to undetectable virus in upper and lower respiratory tract samples in participants who were tested with both upper and lower respiratory tract sampling. Scatterplot where each dot represents a single participant, with the time to undetectable virus with both upper and lower respiratory tract sampling shown for each participant

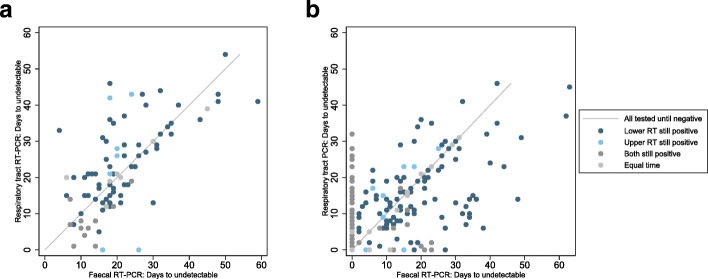

Faecal vs. respiratory tract sampling

Across participants sampled by both RT and faecal sampling since hospital admission, 29% of participants were detected using RT sampling but not by faecal sampling (52/177 participants, 95% CI 23 to 37%, 10 studies). The time to RT-PCR tests becoming undetectable varied greatly by participant, although time to undetectable virus was similar for both sampling sites (Fig. 5), in participants with RT-PCR test results from both RT and faecal samples. Thirty-nine out of 89 participants (44%, 95% CI 33 to 55%) had a shorter duration of detection in faecal samples than in RT samples.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of days to undetectable virus from respiratory tract and faecal sampling. Time to undetectable virus in faecal compared to any respiratory tract sample in participants who were tested with both sampling. Scatterplot where each dot represents a single participant, with the time to undetectable virus with both faecal and respiratory tract sampling shown for each participant. Thirty percent of participants tested at both sampling sites do not have detectable virus in faecal samples

Median time to clearance from RT was shorter in participants based on time since hospitalisation (125 participants, p = 0.014), whilst similar in participants since onset of symptoms (87 participants, p = 0.15) (Additional file 1: Figures S8).

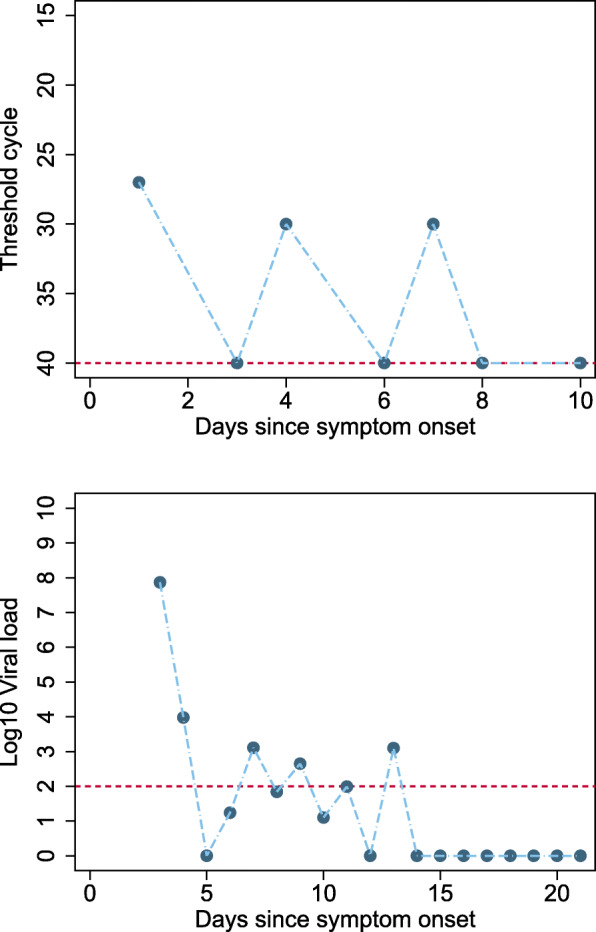

Intermittent false negative results

Many articles reported intermittent false negative RT-PCR test results for participants within the monitoring time span. Where participant viral loads were reported, several different profiles were distinguished; two examples are shown in Fig. 6 [14, 15]. Intermittent false negative results were reported either where the level of virus is close to the limit of detection, or in participants with high viral load but for unclear reasons.

Fig. 6.

Example participants with intermittent false negative results. a An example of a participant with high viral load, but where alternate RT-PCR test results report high viral load or undetectable virus. b A participant where virus levels have reduced over time to a level around the limit of viral detection, and at these low levels of virus, intermittent negative results will occur due to differences in the location or amount of sample

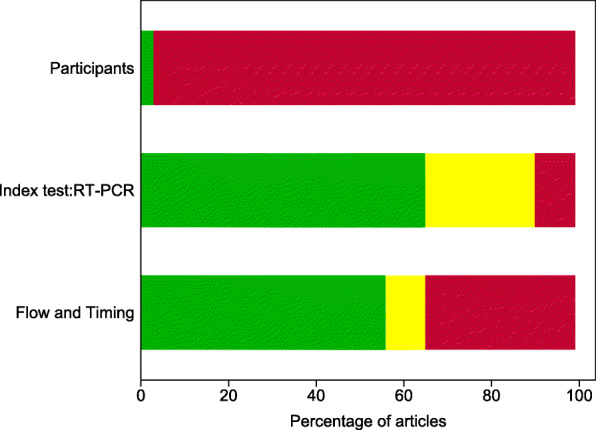

Risk of bias

The proportion of studies with high, low, or unclear ROB for each domain is shown in Fig. 7, and ROB for individual studies is shown in Additional file 1: Table S5. All studies were judged at high ROB. All but one were judged at high ROB for the participant selection domain [17], mainly as they only included participants with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection based on at least one positive PCR test. Studies also frequently selected a subset of the participant cohort for longitudinal RT-PCR testing, and only results for these participants were included in the study. Ten studies were judged at unclear ROB for the index test domain as the schedule of testing was based on clinician choice rather than being pre-specified by the study or clinical guidelines, or because the samples used for PCR testing were not pre-specified. Eleven studies were judged at high ROB for the flow and timing domain mainly because continued testing was influenced by easy access to participants, such as by continued hospitalisation.

Fig. 7.

Risk of bias by adapted QUADAS-2 domain. An adapted version of QUADAS-2 for longitudinal studies was used (Additional file 1: Table S2). For each domain, the percentage of studies by concern for potential risk of bias is shown: low (green), unclear (yellow), and high (red)

Discussion

Key findings

Negative RT-PCR test results were common in people with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirming that RT-PCR testing misses identification of people with disease. Our IPD systematic review has established that sampling site and time of testing are key determinants of whether SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals are identified by RT-PCR.

We found that nasopharyngeal sampling was positive in approximately 89% (95% CI 83 to 93) of tests within 4 days of either symptom onset. Sampling 10 days after symptom onset greatly reduced the chance of a positive test result.

There were limited data on new methods of sample collection like saliva in these longitudinal studies. Sputum samples have similar or higher levels of detection to nasopharyngeal sampling, although this may be influenced by preferential sputum sampling in severely ill participants. Although based on few participants tested at both sampling sites, URT sites have faster viral clearance than LRT in most of these participants; 50% of participants were undetectable at URT sites 12 days after symptom onset compared to 28 days for LRT.

We found that faecal sampling is not suitable for initial detection of disease, as up to 30% of participants detected using respiratory sampling are not detected using faecal sampling. Viral detection in faecal samples may be useful to establish virus clearance, although as noted, whether RT or faecal samples have longer duration of viral detection varies between participants.

All included studies were judged at high ROB, so results of this review should be interpreted with caution. Table 3 provides an overview of the major methodological limitations and their potential impact on study results. A major source of bias is that all but one study [19] restricted inclusion to participants with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection based on at least one positive RT-PCR test, meaning that the percentage of positive RT-PCR testing is likely to be overestimated.

Table 3.

Biases and issues in interpretation

| Domain | Details of bias and applicability issues | Impact on interpretation of study data |

|---|---|---|

| Participants (source of bias) |

In these studies, the reference test usually incorporates RT-PCR (index test). • RT-PCR testing is usually a key component of identifying people with SARS-CoV-2 infection. • Participants will not be detected or included in these studies when SARS-CoV-2 is not present at easily sampled sites and at the time that participants were available for testing. |

Unclear how many and what severity of participants with SARS-CoV-2 are not included in studies. People who do not have a positive RT-PCR test at some point are excluded. This could lead to overestimation of positivity. |

| Rates of positivity will be inflated as only people with virus accessible for sampling for RT-PCR tests will be included in studies. | ||

| Participants (source of bias) | Most participants are identified or present based on respiratory tract symptoms such as cough or respiratory distress. | Unclear how many and what severity of participants with SARS-CoV-2 are not included in studies. |

| • Participants will not be detected or included in these studies when less common symptoms or asymptomatic. | ||

| • Participants included will be biased to over-represent people with detectable virus in respiratory tract sampling sites and at times frequently used for testing (post symptom onset or at admission to hospital). |

Studies will inflate positivity for sampling sites that overlap with sampling sites used in RT-PCR reference testing. • For example, we identified 30% of participants with RT positivity but with negative results from faecal sampling. However, if participants had only faecal virus, would they have been included in the studies? |

|

| Index test: RT-PCR (applicability) | • Studies included are likely to use more invasive sampling methods than acceptable in widespread population testing. For example, nasopharyngeal testing is likely in many current studies to be based on long swabs and self test kits. | Percentage of people with detectable virus may be overestimated when testing is applied in real-world clinical use and in population testing. |

| • Studies will use experienced staff to obtain samples, handle, process, and conduct tests. | ||

| • Studies are mostly sampling participants in hospital settings or in specialised research community testing research where sample handling, transport, and storage have been standardised. | ||

| • Variation in RT-PCR kits is minimised as studies are based in few hospitals or limited to a research setting | ||

| Index test: RT-PCR (applicability) |

Sample RNA extraction methods are designed predominantly for respiratory samples. • RT-PCR sample preparation kits used are mostly designed for extraction of virus from respiratory samples, not from faecal samples. It is unclear how efficiently these kits extract virus RNA from stool samples. |

Percentage of people with virus present in faecal samples and duration of shedding in faecal samples may be underestimated. |

| Index test: RT-PCR (applicability) | RT-PCR tests detect both infectious and inactive (inactive due to immune system or dead) virus. | Percentage of people with clinically important detectable virus may be overestimated. |

| • Few studies link RT-PCR testing to cell assays to test for infectious virus. | ||

| Index test: RT-PCR (applicability) |

Rate of virus aggregation or clearance by immune system may affect the sampling efficiency at some sampling sites. • Both the innate and adaptive immune system will aggregate and clear virus particles from bodily fluids. It is not clear what the time scale of clearance or how this influences detection of virus at different sites and at which time points. |

Percentage of people with detectable virus may be underestimated. |

| Index test: RT-PCR (applicability) |

Reporting of sampling sites and methods is poor. • Poor reporting may have led to less ideal grouping of sampling in analysis. • Some studies are likely to use a variety of nasopharyngeal sampling methods depending on the individual participants, but the type of sampling is typically reported at a study level for a particular sampling site. |

Percentage of people with detectable virus may be over- or underestimated. |

| Flow and timing | Uncertainty and inconsistencies in time of sampling | Percentage of people with detectable virus may be over- or underestimated at particular times. |

|

• Time of symptom onset can be subjective unless based on fever, but some participants do not have fever. • Time of symptom onset may be different if asked of participants in ICU setting. • Time of hospitalisation and discharge may be affected by function hospitalisation serves in containment of disease spread. In some studies, the hospitals were also quarantine centres, so participants were hospitalised immediately at onset of mild symptoms rather than restricted to patients needing oxygen. |

||

| Flow and timing | Clinical cohort within studies changes across time points. | Percentage of people with detectable virus may be overestimated at particular later time points as these correspond to participants who were severely ill. |

|

• Participants who have recovered from COVID-19 in most studies are typically not tested after 2 negative tests 24 h apart. • Many studies only test inpatients at the hospital, so the participants sampled between 0 and 14 days typically have less severe disease than those tested longer |

||

| Flow and timing (selective outcome reporting) | Some studies only publish IPD data for a selection of people. | Available IPD data may not represent a typical spectrum of participants in the different settings (community setting, hospital, ICU, nursing home, prison). |

| Publication bias | Published data is likely to be biased towards publication of research active groups which may not represent typical real world. | Percentage of people with detectable virus may be overestimated. |

BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, ICU intensive care unit, IPD individual participant data, RNA ribonucleic acid, RT-PCR reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, SARS-CoV-2 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Lack of technical details, for example of how samples are taken and RT-PCR tests performed, limits the applicability of findings to current testing. Compared to real life, studies were likely to use more invasive sampling methods, use experienced staff to obtain samples, and sample participants in hospital settings where sample handling could be standardised. Consequently, estimates of test performance are likely to be overestimated compared to real-world clinical use and in community population testing including self-test kits.

These limitations have important implications for how testing strategies should be implemented and in particular how a negative RT-PCR test result should be interpreted.

Putting the findings into context of literature

The accuracy of RT-PCR testing is limited by sampling sites used, methods, and the need to test as soon as possible from symptom onset in order to detect the virus. Previous studies have established that in COVID-19 infection, viral loads typically peak just before symptoms and at symptom onset [4] and estimated false negative test results over time since exposure from upper respiratory tract samples [2]. To our knowledge, there has been no prior systematic review of RT-PCR using IPD to quantify the percentage of persons tested who are positive and how this varies by time and sampling site.

Understanding the distribution of anatomical sites with detectable virus is clinically relevant, especially given independent viral replication sites in nose and throat using distinct and separate genetic colonies [17]. Understanding of different patterns of detection and duration of virus detection at different body sites is essential when designing strategies of testing to contain virus spread. Notably, it is unclear if detection of virus in faeces is important in disease transmission, although faecal infection was shown in SARS and MERS [41].

Strengths of study

This review uses robust systematic review methods to synthesise published literature and identifies overall patterns not possible from individual articles. Using IPD, we examined data across studies and avoided study-level ecological biases present when using overall study estimates. IPD regarding sample site at different time points during infection is vital because it provides an overview of test performance impossible from individual studies alone. Synthesised IPD can also substantiate or reject patterns appearing within individual studies. Within-participant paired comparisons of sampling sites also become possible with sufficient data.

Limitations of study

The main limitation is the risk of bias in the included studies. Although constraints were understandable given the circumstances in which the studies were done, the consequences for validity need to be highlighted. The percentage of positive RT-PCR testing is likely to be overestimated, because inclusion was restricted to participants with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection based on at least one positive RT-PCR test in all but one study [19]. This means that people who had a COVID-19 infection but never tested positive on at least one RT-PCR test would not have been included. This could arise if SARS-CoV-2 is not present at easily sampled sites or at the time participants were tested. This makes it impossible to determine the true false negative rate of the test—the proportion of people who actually have SARS-CoV-2 but would receive a negative RT-PCR test result. It is possible that only half of persons infected by SARS-CoV-2 may test positive, as a community surveillance study in Italy found only 53% (80/152) persons tested RT-PCR positive in households quarantined for 18 days with persons who tested PCR positive [39]. The same study also identified households where no one tested RT-PCR positive, but where there were clusters of persons with symptoms typical of COVID.

Poor reporting of sampling methods and sites impaired our ability to distinguish between and report on variability between them. For some sampling methods such as saliva and throat swabs, more studies are needed. There were also sparse data on sampling methods that are becoming more widespread, such as participant self-sampling [42] and short nasal swab sampling (anterior nares/mid turbinate) [43]. Our index times may be subject to bias as symptom onset is somewhat subjective and hospital admission practices vary by country, pandemic stage, and hospital role (i.e. healthcare vs. isolation). The results presented do not correspond to following the same participants across time, but the testing at clinically relevant time snapshots reported from individual studies, so that participants tested at later time points are likely to have more severe disease; this does not limit the interpretation of results in understanding testing of participants in most clinical contexts. Comparisons of sampling sites should be restricted to participants tested at the relevant sites.

We have used analysis methods that do not include clustering within studies, to keep analyses simple to understand and present, and to avoid complications of fitting models where the number of participants in each cluster varies. Ultimately, many potentially eligible studies did not report IPD which led to their exclusion, or only reported IPD for a subset of participants in the study. We would welcome contact and data sharing with clinicians and authors to rectify this.

Implications for policy/practice/future research

To avoid the consequences of missed infection, samples for RT-PCR testing need to be taken as soon as symptoms start for detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in preventing ongoing transmission.

Even within 4 days of symptom onset, some participants infected with SARS-CoV-2 will receive negative test results. Testing at later times will result in a higher percentage of false negative tests in people with SARS-CoV-2, particularly at upper RT sampling sites. After 10 days post-symptoms, it may be important to use lower RT or faecal sampling. Valid estimates are essential for clinicians interpreting RT-PCR results. However, ROB considerations suggest that the positive percentage rates we have estimated may be optimistic, possibly considerably so.

Participants can have detectable virus in different body compartments, so virus may not be detected if samples are only taken from a single site. Some hospitals in the UK now routinely take RT-PCR samples from multiple sites, such as the nose and throat. More studies are urgently needed on evolving sampling strategies such as self-collected samples which include saliva and short nasal swabs. Future studies should avoid the risks of bias we have identified by precisely reporting the anatomical sampling sites with a detailed methodology on sample collection. Table 4 details example studies helpful for future study design.

Table 4.

Examples from included studies

| Study characteristic | Detail | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Study design: representative recruitment |

Representative participants • Community infection • Contact tracing including asymptomatic • Hospitalised patients |

Population surveillance of Italian town, with PCR testing across [39] Retrospective cohort of 96 hospitalised patients [38] |

| Study design: planned testing and follow-up |

Informative sampling • Multiple sampling sites per participant • Planned schedule of sampling • Sampling continues after negative test results • Sampling continues after hospital discharge |

Three samples per patient, multiple testing including prolonged testing even after multiple negative results [10] Population surveillance of Italian town over 18 days [39] Long follow-up post-hospital [16, 35, 36] Planned schedule of testing ([30], asymptomatic contact tracing follow-up [36–38]) |

| Study design: sampling | Reporting of sampling methods (sample site, staff conducting test, sample volumes, and methods) |

Most studies had very sparse reporting of sample collection methods. Example of fuller reporting [40] |

| Individual participant data reporting for sharing | Examples of plots and tables that facilitated sharing of individual participant data |

Retrospective cohort of 96 patients all tested with sputum, faeces, and blood. Plot shows time span of positive test results, hospitalisation timing, and disease severity for individual patients [38] Data showing time course of illness with PCR test results [9, 31] Data showing RT-PCR test results by patient and time point [10] Viral load over time [15] |

Further sharing of IPD will be important, and we would welcome contact from groups with IPD data we can include in ongoing research.

Conclusions

RT-PCR misses detection of people with SARS-CoV-2 infection; early sampling minimises false negative diagnoses. Beyond 10 days post-symptom onset, lower RT or faecal testing may be preferred sampling sites. The included studies are open to substantial risk of bias, so the positivity rates are probably overestimated.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Including additional tables and figures: search details, QUADAS-2 adaption, anatomical sample size details, risk of bias by article, percentage positive and negative RT-PCR results by sample for days since symptom onset and days since hospitalisation, time to undetectable virus in faecal and respiratory tract.

Acknowledgements

“Virus Bashers” team

Steve Harris, Christine Bennett, Tim Carne, Chris Challis, Christian Dixon, Jan Dixon, Sue Hamer-Moss, Brenda Johnston, Lionel Murphy, Lois Norton, Jonathan Sanvoisin, Glen Titmus, Claire Hicks, John Golightly, Stuart Wilson, and Friends

Abbreviations

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- BALF

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CI

Confidence interval

- Ct

Cycle threshold

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IPD

Individual participant data

- KM

Kaplan-Meier

- LRT

Lower respiratory tract

- MERS

Middle East respiratory syndrome

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- NIHR

National Institute for Health Research

- QUADAS-2

A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- ROB

Risk of bias

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- RT

Respiratory tract

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- TOC

Table of characteristics

- UK

United Kingdom

- URT

Upper respiratory tract

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

SM conceived the study and design. JA, SG, BS, PT, CH, ST, NS, PW, and RW contributed to the study design. NR, SM, BS, ZZ, CH, JP, Virus Bashers team, SG, and LFdR selected the articles. SM, BS, ZZ, CH, JP, KG, JS, JA, SG, and AW extracted the data. SM analysed the data. SM, SH, ST, NS, CH, PW, and RW wrote the first and second drafts of the manuscript. SM, SH, ST, NS, CH, PW, RW, JA, SG, KG, JS, BS, ZZ, JP, PT, NR, LFdR, GB, BN, and AW interpreted the data and contributed to the writing of the final version of the manuscript. All authors agreed with the results and conclusions of this article.

Funding

No specific funding has been received for this research.

SM, SAT, and SH receive funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

SAT is an NIHR senior investigator.

SM, SAT, NS, and SH receive funding from the UCL/UCLH Biomedical Research Centre.

AJA, SG, KG, JS, and AW are funded by the NIHR Newcastle In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative.

BS is part-funded by NIHR Leeds In Vitro Diagnostic Co-operative.

PJT receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Community Healthcare MedTech and In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

BDN is an NIHR Academic Clinical Lecturer.

Funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

SM, SH, AJA, SG, KG, SAT, BS, JP, PT, PW, JS, LFR, NR, NS, JS, AW, JA, GB, KG, and BN declare no conflicts of interest for the submitted work.

CH has advised Attomarker, a spin-out company of the University of Exeter about the conduct of evaluations of its tests for COVID antibodies, but received no payment for this advice and provided it as part of academic duties at the University of Exeter.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12916-020-01810-8.

References

- 1.Wikramaratna P, Paton RS, Ghafari M, Lourenco J. Estimating false-negative detection rate of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.04.05.20053355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J. Variation in false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction-based SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):262–267. doi: 10.7326/M20-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, Yang S, Wang L, Tang Y, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1657–1665. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Clinical management of COVID-19. WHO Interim guidance. 2020;WHO/2019-nCoV/clinical/2020.5 (accessed 16 June2020).

- 7.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohatgi A. WebPlotDigitizer https://apps.automeris.io/wpd/ (Accessed 16 June 2020). 2010.

- 9.Cai J, Wenjie S, Jianping H, Michelle G, Jing W, Guiqing H. Indirect virus transmission in cluster of COVID-19 cases, Wenzhou, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6):1343. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C, Gao G, Xu Y, Pu L, Wang Q, Wang L, et al. SARS-CoV-2–positive sputum and feces after conversion of pharyngeal samples in patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Yang Y, Yang M, Shen C, Wang F, Yuan J, Li J, et al. Evaluating the accuracy of different respiratory specimens in the laboratory diagnosis and monitoring the viral shedding of 2019-nCoV infections. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.02.11.20021493.

- 12.Chen J, Qi T, Liu L, Ling Y, Qian Z, Li T, et al. Clinical progression of patients with COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. J Infect. 2020;80(5):e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.To KK, Tsang OT, Yip CC, Chan KH, Wu TC, Chan JM, et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):841–3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Yan L-M, Wan L, Xiang T-X, Le A, Liu J-M, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):656–657. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang D, Mo G, Yuan X, Tao Y, Peng X, Wang F-S, et al. Time kinetics of viral clearance and resolution of symptoms in novel coronavirus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):1150–1152. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0524LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Müller MA, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo IL, Lio CF, Cheong HH, Lei CI, Cheong TH, Zhong X, et al. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding in clinical specimens and clinical characteristics of 10 patients with COVID-19 in Macau. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1698–1707. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song C, Wang Y, Li W, Hu B, Chen G, Xia P, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in semen and testicular biopsy specimen of COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.03.31.20042333.

- 20.Lu R, Wang J, Li M, Wang Y, Dong J, Cai W. SARS-CoV-2 detection using digital PCR for COVID-19 diagnosis, treatment monitoring and criteria for discharge. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.03.24.20042689.

- 21.Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):589–594. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan Y, Wang N, Ou X. Caution should be exercised for the detection of SARS-CoV-2, especially in the elderly. J Med Virol. 2020; n/a(n/a). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Xiao AT, Tong YX, Zhang S. Profile of RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary study from 56 COVID-19 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Xu K, Chen Y, Yuan J, Yi P, Ding C, Wu W, et al. Factors associated with prolonged viral RNA shedding in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Zhang W, Du R-H, Li B, Zheng X-S, Yang X-L, Hu B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):386–389. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young BE, Ong SWX, Kalimuddin S, Low JG, Tan SY, Loh J, et al. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1488–1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lescure F-X, Bouadma L, Nguyen D, Parisey M, Wicky P-H, Behillil S, et al. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):697–706. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiehao C, Xu J, Lin D, Yang Z, Xu L, Qu Z, et al. A case series of children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection: clinical and epidemiological features. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(6):1547–51. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.03.15.20036707.

- 30.Hu Z, Song C, Xu C, Jin G, Chen Y, Xu X, et al. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(5):706–711. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kujawski SA, Wong KK, Collins JP, Epstein L, Killerby ME, Midgley CM, et al. First 12 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.03.09.20032896. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Liu F, Xu A, Zhang Y, Xuan W, Yan T, Pan K, et al. Patients of COVID-19 may benefit from sustained lopinavir-combined regimen and the increase of eosinophil may predict the outcome of COVID-19 progression. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu T, Chen C, Zhu Z, Cui M, Chen C, Dai H, et al. Clinical features and dynamics of viral load in imported and non-imported patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C, Ji F, Wang L, Wang L, Hao J, Dai M, et al. Asymptomatic and human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a 2-family cluster, Xuzhou. China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1626–8. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang B, Liu S, Dong Y, Zhang L, Zhong Q, Zou Y, et al. Positive rectal swabs in young patients recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J Infect. 2020;81(2):e49–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y, Li X, Zhu B, Liang H, Fang C, Gong Y, et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y, Guo C, Tang L, Hong Z, Zhou J, Dong X, et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng S, Fan J, Yu F, Feng B, Lou B, Zou Q, et al. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January-March 2020: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavezzo E, Franchin E, Ciavarella C, Cuomo-Dannenburg G, Barzon L, Del Vecchio C, et al. Suppression of COVID-19 outbreak in the municipality of Vo, Italy. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.04.17.20053157.

- 40.Wyllie AL, Fournier J, Casanovas-Massana A, Campbell M, Tokuyama M, Vijayakumar P, et al. Saliva is more sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 detection in COVID-19 patients than nasopharyngeal swabs. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.04.16.20067835.

- 41.Amirian ES. Potential fecal transmission of SARS-CoV-2: current evidence and implications for public health. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kojima N, Turner F, Slepnev V, Bacelar A, Deming L, Kodeboyina S, et al. Self-collected oral fluid and nasal swabs demonstrate comparable sensitivity to clinician collected nasopharyngeal swabs for covid-19 detection. medRxiv. 2020; 2020.04.11.20062372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Gates B. 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xe8fIjxicoo. Accessed 16 June 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Including additional tables and figures: search details, QUADAS-2 adaption, anatomical sample size details, risk of bias by article, percentage positive and negative RT-PCR results by sample for days since symptom onset and days since hospitalisation, time to undetectable virus in faecal and respiratory tract.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.