Abstract

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unknown origin. Rarely, BD occurs together with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Interestingly, it is speculated that these are not simple coexistence but that the etiology of intestinal BD is at least partly derived from MDS itself. Furthermore, there is a relationship between MDS in patients with intestinal BD and trisomy 8. Immunosuppressive agents alone are insufficient to control MDS-associated BD, and many of these patients die of infection or hemorrhage. Surgery is considered for intestinal BD patients who are unresponsive to medical treatment or those with bowel complications such as perforation or persistent bleeding. We report a case of intestinal BD associated with MDS and trisomy 8. The patient was unresponsive to oral steroids and immunosuppressive treatment; the patient improved by surgical repair of a bowel perforation. Five years after the surgery, the patient is free of recurrence and not on medication. Our experience suggests that surgery may provide an effective therapeutic option for the treatment of MDS-related BD.

Keywords: Behcet syndrome, Myelodysplastic syndrome, Trisomy 8

INTRODUCTION

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterized by recurrent oral ulcers, skin lesions, uveitis, and genital ulcers. Many other systems can be involved, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, central nervous system, cardiovascular system, musculoskeletal system, and arthritic joints [1]. Intestinal BD occurs in 3%–60% of patients with BD [1], with clinical manifestations ranging widely from mild abdominal pain to bowel perforation or massive hemorrhage with a poor prognosis. Although Immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antibody (infliximab, adalimumab), and corticosteroid are used to treat intestinal BD, a standard treatment for intractable BD has not been established. Surgery is considered for intestinal BD patients who are unresponsive to medical treatment or those with bowel complications such as perforation or persistent bleeding.

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell diseases characterized by cytopenia, dysplastic changes in two or more myeloid cell lines, and ineffective hematopoiesis [2]. Several autoimmune diseases are associated with MDS [3]. Trisomy 8 is one of the most common abnormalities accompanying MDS, occurring with a frequency of 8.9%–20% [4].

Although BD and MDS are different disease entities, several studies have identified a relationship between them, especially among patients with trisomy 8 [4,5]. Several studies indicate that immunosuppressive agents alone are insufficient to control BD associated with MDS and many patients die of infection or hemorrhage [6]. While the incidence of BD itself is endemically high in East Asia and Mediterranean countries, few reports describe the occurrence of intestinal BD with MDS. Among these few reports, the cases of perforation with a favorable outcome are rare.

Here we report a case of intestinal BD associated with MDS and trisomy 8.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that surgery provides a 5-year favorable outcome for MDS-associated BD. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Yamanashi Hospital (IRB No. 1326) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for the publication of clinical details and images was obtained from the patient.

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old man presented to our hospital with stomatitis and fever. He was diagnosed with MDS-refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia in 2011; however, he had refused bone marrow transplantation and decided instead to monitor his condition. Ileocolonoscopy revealed multiple ulcers in the ileocecal region (Fig. 1). Histopathological examination suggested no malignant findings or nonspecific inflammation (Fig. 2). On the basis of these findings, he was diagnosed with intestinal BD in 2012. On physical examination, the patient was febrile and had no ocular symptoms, skin lesions, or genital ulcers. A blood test showed anemia with a red blood cell count of 2,350 × 103/μL, hemoglobin of 8.0 g/dL, hematocrit of 25.0%, hypoalbuminemia (2.5 g/dL), liver damage (aspartate aminotransferase, 46 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, IU/L), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP; 9.03 mg/dL), and positivity for histocompatibility antigen B51 (Table 1). Bone marrow aspiration revealed MDS with trisomy 8. Based on these findings, he was diagnosed with intestinal BD associated MDS with trisomy 8. His pathergy test was negative.

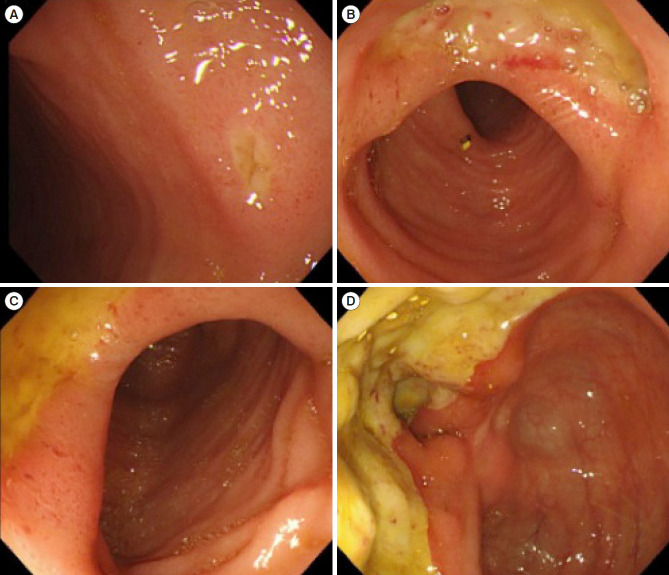

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic images. (A-D) Photographs of multiple punched-out ulcers in the ileocecum.

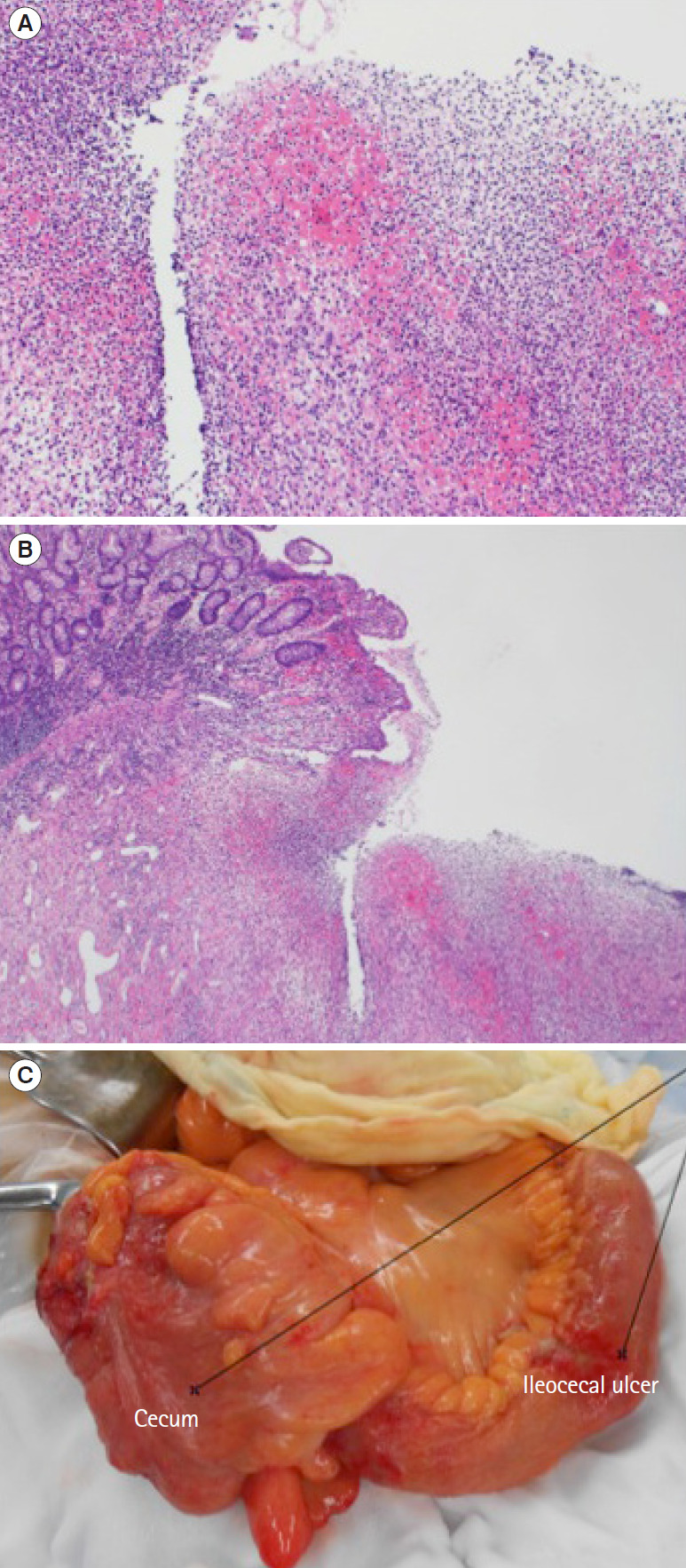

Fig. 2.

Pathological findings. Histological image of biopsy specimens from the margin of the ileocecal ulcer show no malignant findings or nonspecific inflammatory changes at ×10 magnification of the objective lens (A) and ×4 magnification (B); the magnification of the objective lens is not identified because camera systems have become an integral part of the microscope (H&E). (C) Ileocecal resection with ileostomy reveals penetration of the ileum, as well as ileal ulcers.

Table 1.

Patient Laboratory Data upon Admission

| Test name | Value |

|---|---|

| Biochemistry | |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.1 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.5 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.8 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 16.5 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.48 |

| AST (IU/L) | 46 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 146 |

| LDH (IU/L) | 172 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 1,265 |

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (mg/dL) | 528 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 9.03 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 25 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 132 |

| K (mEq/L) | 3.8 |

| Cl (mEq/L) | 97 |

| Hematology | |

| White blood cell (× 103/μL) | 5.68 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.0 |

| Red blood cell (× 103/μL) | 2,350 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 25.0 |

| Platelet (× 103/μL) | 109 |

| Coagulation test | |

| PT-INR | 1.12 |

| aPTT (sec) | 30.2 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 502 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; CRP, C-reactive protein; PT-INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time.

Intensive treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid, colchicine, oral prednisolone (PSL), and mercaptopurine was ineffective (Fig. 3). Next, adalimumab was administered for intestinal BD, but this treatment was discontinued due to thrombocytopenia. Subsequently, we prescribed oral PSL, resulting in symptom improvement. Despite tapering the medication slowly over several weeks, his abdominal pain and fever steadily worsened. Abdominal computed tomography revealed wall thickening of the ileocecum, disproportionation fat stranding, and perforation of the ileum (Fig. 4). Therefore, ileocecal resection with ileostomy was performed. During the surgery, we observed penetration of the ileum, as well as ileal ulcers (Fig. 2). We continued intravenous administration of high dose of PSL pre- and postoperatively due to steroid cover, and treatment of oral PSL was started five postoperatively. The patient progressed favorably after the surgery and the PSL dose was successfully tapered. Five months postoperatively, we finished PSL therapy. Nine months after the bowel perforation event, we closed the colostomy. No residual lesions of intestinal BD were found after the surgery (Fig. 5). He remains in drug-free remission of intestinal BD 5 years after the bowel resection.

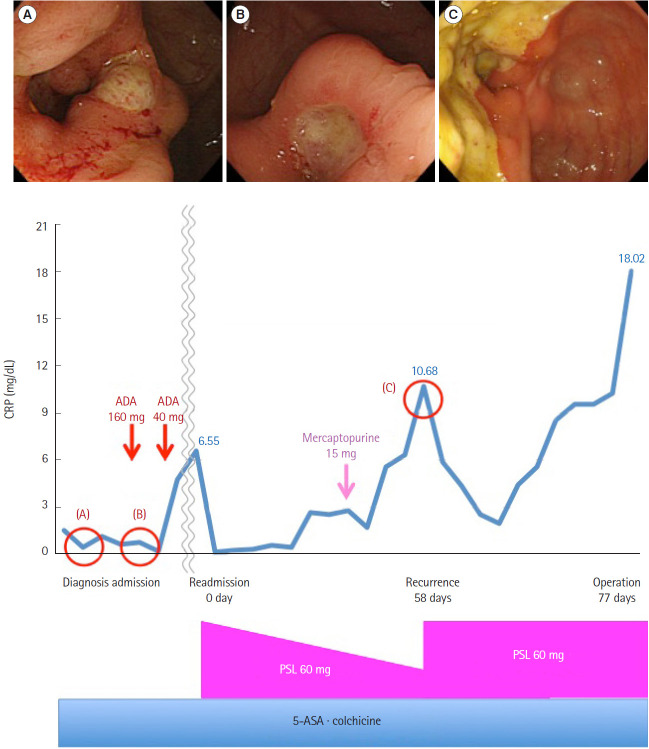

Fig. 3.

Therapy flowchart. First, intensive treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), colchicine was ineffective, so we decided to administer prednisolone (PSL) on readmission. Next, mercaptopurine was administered for intestinal Behçet’s disease, but this treatment was discontinued due to liver damage. PSL was effective and tapered slowly over several weeks, but his abdominal pain and fever steadily worsened and computed tomography revealed perforation of the ileum. Therefore, ileocecal resection with ileostomy was performed. The 0 day refers to the day of readmission, 1 day refers to the day of PSL administration. The 58 days refers to the day of recurrence, 77 days refers to the day of operation. (A) At diagnosis (1.5 years ago), (B) on admission (1 year ago), and (C) at recurrence (58 days). ADA, adalimumab; CRP, C-reactive protein.

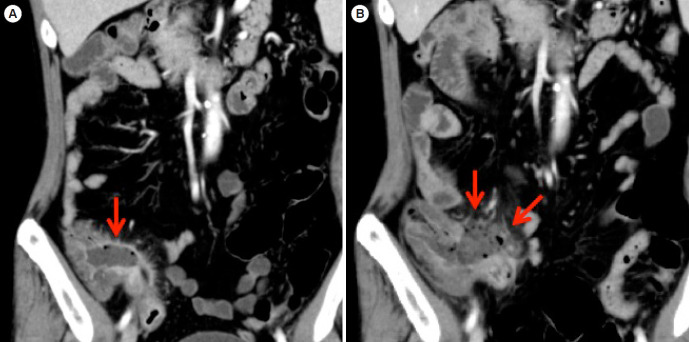

Fig. 4.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) found wall thickening of the ileocecum, disproportionation fat stranding, and ileal perforation. (A) CT on admission, (B) CT at the recrudescent time. The arrows indicate ileal perforation.

Fig. 5.

The endoscopic image of about 5 years after the anastomosis.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies report the occurrence of intestinal ulcers in 3%–16% of BD patients [1], with few reported cases of favorable outcomes for those with intestinal perforation. Here, we report a case of intestinal BD with perforation complicated by MDS and trisomy 8, in which the patient experienced a positive 5-year outcome after surgical repair.

Several mechanisms have been suggested to explain the association between BD and MDS. The presence of trisomy 8 facilitates the production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, interferon (IL)-6, and IL-1β, which increase neutrophil function and are known risk factors for intestinal ulcers. Therefore, trisomy 8 may lead to the development of intestinal ulcers in patients with MDS [5].

Interestingly, the frequency of intestinal BD is significantly higher in BD patients with BD with than without bone marrow failure (61.5% vs. 13.6%) [7]. Handa et al. [8] reported the data of 64 patients with BD and MDS, and they observed high frequencies of intestinal lesions (66%) and trisomy 8 (80%) but a low frequency of ocular lesions (13%). In particular, the data demonstrated that intestinal lesions were characteristic findings in BD associated with trisomy 8 and bone marrow failure, especially in MDS.

Although treatment for BD typically includes immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, antiTNF-α antibody (infliximab, adalimumab), and corticosteroids, standard treatment for intractable BD has not been established. According to some studies, the administration of immunosuppressive agents alone is insufficient to control MDS-associated intestinal BD, and many patients die of hemorrhage, infection, or recurrent ulcers before MDS treatment [6]. Controlling MDS-related BD is difficult because the underlying immune abnormalities arise from MDS itself [4].

Mortality is low in BD; however, intestinal perforation is a common cause of death among fatal cases. Surgical intervention is often necessary for intestinal BD patients who are unresponsive to medical treatment or have bowel complications such as perforation or persistent bleeding [9]. Because no standard surgical treatment has been established, the choice of surgical treatment is empirical and symptom-based. Kurata et al. [10] report that surgery should be strongly considered if the steroid dose exceeds 40 mg/day. Jung et al. [11] suggest that patients with intestinal BD have better outcomes with early rather than late surgery. Thus, early surgery may be a valid approach to the initial management of a subset of BD patients with acute symptoms.

Patients treated surgically for intestinal BD have frequent postoperative complications and a high risk of recurrence. Even after successful surgery, refractoriness to medical measures and complications such as poor healing of the anastomosis site and postoperative ulcer recurrence are so common that repeated surgeries are often required. Unfortunately, the most effective way to reduce and treat postoperative complications and recurrence is unclear. Byeon et al. [12] report that infliximab may be an effective novel therapy for the management of early postoperative complications and recurrence in intestinal BD. Factors associated with a poor prognosis after surgical treatment for intestinal BD include volcano-shaped ulcers, higher CRP levels, a history of postoperative steroid therapy, and the presence of intestinal perforations [13]. An increasing number of intestinal BD cases associated with MDS and trisomy 8 have been recently reported. In such cases, lower GI studies must be planned as early as possible, since the ulcer lesions in the ileocecal region are at risk of perforation. Iida et al. [14] report that intraoperative endoscopy may be useful for preventing postoperative recurrence and that periodic follow-up examination with radiography and endoscopy should be performed, even after surgery.

In conclusion, we report the first case in which surgery provided a favorable 5-year outcome in a patient with MDS-associated BD. As shown in Table 2 [9,10,15-20], there is no case that surgery provides a long-term outcome like our case. The diagnosis and treatment of such patients may be complicated, but we believe that an improved understanding of this complex disease and collaborative therapy can lead to improved care and reduce adverse outcomes.

Table 2.

Case Reports of Surgically Treated Patients

| Author (year) | Country | Age (yr) | Sex | Perforation | Operation | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawano et al. (2015) [15] | Japan | 45 | Male | - | + | 9 Months (death) |

| Wada et al. (2015) [16] | Japan | 35 | Female | + | + | 1 Year (alive) |

| Umehara et al. (2010) [17] | Japan | 73 | Female | + | + | 22 Days (death) |

| Nishimura et al. (2004) [18] | Japan | 52 | Male | - | + | 8 Months (death) |

| Higa et al. (2003) [19] | Japan | 26 | Female | + | + | 6 Months (alive) |

| Hulscher et al. (2003) [9] | Netherlands | 52 | Male | + | + | 1 Year (alive) |

| Kurata et al. (2006) [10] | Japan | 8 Consecutive | Japanese patients | + | + | 2 Years (3 recurrence and 5 stable) |

| Arhan et al. (2005) [20] | Turkey | 37 | Male | + | + | 12 Months (alive) |

Acknowledgments

We would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisors, and the patient.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Mori Y, Iwamoto F. Data collection: all authors. Writing-original draft: Mori Y, Iwamoto F. Writing - review and editing: Mori Y, Iwamoto F, Ishida Y, Kuno T, Kobayashi S, Yoshida T, Yamaguchi T, Sato T, Enomoto N. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284–1291. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunning RD, Germing U, Le Beau MM, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes/neoplasms, overview. In: Swerd Low SH, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, et al., editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro M, Conn DL, Su WP, Garton JP. Rheumatic manifestations in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:721–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohno E, Ohtsuka E, Watanabe K, et al. Behçet’s disease associated with myelodysplastic syndromes: a case report and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1997;79:262–268. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970115)79:2<262::aid-cncr9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tada Y, Koarada S, Haruta Y, Mitamura M, Ohta A, Nagasawa K. The association of Behçet’s disease with myelodysplastic syndrome in Japan: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(5 Suppl 42):S115–S119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa T, Arai Y, Mitani K. Myelodysplastic syndrome associated with intestinal tract-type Behçet disease characterized by an esophageal ulcer. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2004;45:1135–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn JK, Cha HS, Koh EM, et al. Behcet’s disease associated with bone marrow failure in Korean patients: clinical characteristics and the association of intestinal ulceration and trisomy 8. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1228–1230. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Handa T, Nakatsue T, Baba M, Takada T, Nakata K, Ishii H. Clinical features of three cases with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis secondary to myelodysplastic syndrome developed during the course of Behçet’s disease. Respir Investig. 2014;52:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hulscher JB, van den Berg HP, Siegert CE, Steller EP. A Turkish man with Behçet disease and recurrent acute abdomen. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2003;147:1969–1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurata M, Nozue M, Seino K, Murata H, Sumita T, Katashi F. Indications for surgery in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:60–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung YS, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Early versus late surgery in patients with intestinal Behçet disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:65–71. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318238b57e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byeon JS, Choi EK, Heo NY, et al. Antitumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy for early postoperative recurrence of gastrointestinal Behçet’s disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:672–676. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0813-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung YS, Yoon JY, Lee JH, et al. Prognostic factors and long-term clinical outcomes for surgical patients with intestinal Behcet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1594–1602. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iida M, Kobayashi H, Matsumoto T, et al. Postoperative recurrence in patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:16–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02047208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawano S, Hiraoka S, Okada H, Akita M, Iwamuro M, Yamamoto K. Clinical features of intestinal Behçet’s disease associated with myelodysplastic syndrome and trisomy 8. Acta Med Okayama. 2015;69:365–369. doi: 10.18926/AMO/53912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wada Y, Nakatsue T, Kuroda T, et al. A case of intestinal Behcet’s disease complicated with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) refractory to anti-TNF drug treatment after bone marrow transplantation. J Chubu Rheumatism Association. 2015;45:45–46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umehara Y, Kudo M, Kawasaki M. Endoscopic findings of intestinal Behçet’s disease complicated with toxic megacolon. Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E173–E174. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimura K, Fujiki R, Hirotsu J, et al. A case of hilar bile duct cancer with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Kurume Med J. 2004;51:169–173. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.51.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higa A, Uezu Y, Shiohira Y. A case of intestinal Behcet’s disease with perforation early onset. Kyushu J Rheumatology. 2003;22:110–114. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arhan M, Ibiş M, Koklu S, Ozin Y, Oymaci E. Behcet’s disease complicated with descending colon perforation. Dig Surg. 2005;22:381. doi: 10.1159/000091000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]