Abstract

Background:

Most people with opioid use disorder (OUD) are not treated with FDA-approved medications methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone. Expanding capacity for evidence-based OUD medication in primary care is a national priority. No studies have examined primary care trainee physicians’ attitudes about these medications. This study surveyed a national sample of primary care trainee physicians and compared their views with those of primary care attending physicians (i.e., those who have completed training).

Methods:

Random samples of 1,000 trainee physicians and 1,000 attending physicians specializing in family, internal, or general medicine were selected from the American Medical Association Masterfile. Surveys were mailed February-August 2019. 45% of eligible trainee physicians and 54% of eligible attending physicians responded. Chi-square tests were used to compare responses between the groups.

Results:

Trainee physicians were more likely than attending physicians to agree that treating OUD with medication is more effective than treatment without medication (76% versus 67%, p=0.03). Half of trainee physicians (51%) expressed interest in treating patients with OUD compared to 20% of attending physicians. Trainee physicians expressed greater support than attending physicians for policies that loosen restrictions on prescribing OUD medications.

Conclusions:

Relative to attending physicians, the emerging cohort of primary care physicians may be more receptive to working with patients with OUD and prescribing medication. Enhancing medical training on OUD and its treatment, exposing clinicians to individuals in recovery from OUD, and increasing support for clinicians that provide medication treatment for OUD may strengthen this group’s capacity to respond to the opioid crisis.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, survey research, medical training and education, primary care

1. INTRODUCTION

Most people with opioid use disorder (OUD) do not receive evidence-based treatment with FDA-approved medications methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019). Unlike methadone, which can only be administered in specialty clinics, buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed for OUD in office-based settings by physicians and other clinicians with advanced training, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants. However, less than 10 percent of U.S. physicians have obtained the waiver required by federal law to prescribe buprenorphine to treat OUD (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2020). Expanding OUD medication prescribing in primary care, the backbone of the health system and the setting in which individuals with OUD may be most likely to interact with health professionals, is a national priority (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019). Yet misinformation and stigma toward both individuals with OUD and the medications to treat OUD among health professionals can pose barriers to broadening access to effective treatment (McGinty et al., 2020; Van Boekel et al., 2013). Efforts to incorporate OUD treatment into medical training are growing (Haffajee et al., 2018; Tesema et al., 2018), but no studies have assessed views about OUD medications among trainee physicians. To address this gap, we surveyed a national sample of primary care trainee physicians and compared their views with those of attending primary care physicians (i.e., those who have completed their training) who participated in an identical survey (McGinty et al., 2020).

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Study Sample

We selected random samples of 1,000 trainee physicians specializing in family or internal medicine and 1,000 attending physicians specializing in family, internal, or general medicine from the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile, a database of all U.S. physicians. Selected individuals received a questionnaire, $2 incentive, and stamped return envelope in February 2019; non-responders received up to five follow-up mailings with the same contents through August 2019. Trainee physicians were eligible if they were practicing primary care through a residency placement at the address of record in the AMA Masterfile. Similarly, attending physicians were determined eligible if they were actively practicing primary care at the address of record. We excluded from the analysis 17 trainee physicians and 25 attending physicians with missing responses to greater than half of the survey questions. Trainee physicians responding to the survey were more likely to have a family medicine residency than non-responding trainee physicians; however, the majority in both groups were training in internal medicine residencies (see Appendix). Among the sample of attending physicians, the distribution across specialties was the same among responders and non-responders (McGinty et al., 2020). We used survey weights to adjust estimates for differences between sampled participants who did and did not respond to the survey.

2.2. Measures

Survey domains included perceived effectiveness of methadone, buprenorphine, and injectable extended-release naltrexone as OUD treatments, interest in treating patients with OUD, willingness to live near a medication treatment provider, a dimension of stigma known as “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) (Bernstein and Bennett, 2013; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2016; Tsai et al., 2019), and support for policies to expand access to medications for OUD. Respondents reported the degree to which they endorsed specific statements within each of these domains on 5-point Likert scales. In addition, the survey asked respondents whether they were waivered to prescribe buprenorphine. Respondents could select one of the following mutually exclusive response options: yes, I am waivered and I have prescribed buprenorphine to at least one patient with OUD; yes, I am waivered but I have not prescribed buprenorphine to a patient with OUD; no, I am not waivered but I am interested in becoming waivered to be able to prescribe buprenorphine in the future; and no, I am not waivered and I am not interested in prescribing buprenorphine. All survey questions are displayed in Appendix 1.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

For all items except buprenorphine prescribing practices (which had mutually exclusive response options), we dichotomized 5-point Likert scale responses to calculate the percentage of trainee physicians and attending physicians endorsing each statement. We created these dichotomized variables by recoding the top two values (e.g., strongly agree and somewhat agree) as one and the remaining three Likert scale values as zero. The distribution across all Likert scale response options for the survey questions is provided in the Appendix. Using the dichotomized measures, we conducted chi-square tests of differences in the percentages between trainee and attending physicians. A more detailed analysis of the survey of attending primary care physicians has been reported elsewhere (McGinty et al., 2020). This study was deemed exempt by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

3. RESULTS

Among 512 eligible trainee physicians, 228 responded (45%). Among 668 eligible attending physicians, 361 responded (54%). Trainee physicians were more likely than attending physicians to agree that treating OUD with medication is more effective than treatment without medication (76.3% vs. 67.1%, p=0.03) (Figure 1). A larger percentage of trainee physicians expressed interest in treating patients with OUD relative to attending physicians (50.8% vs. 20.2%, p<0.01). In this sample, 18.2% of trainee physicians and 10.3% of attending physicians reported being waivered to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD, although over half of the trainee physicians who were waivered reported not yet having prescribed buprenorphine for OUD. Among trainee physicians who were not waivered to prescribe buprenorphine, 35.8% expressed interest in becoming waivered compared with 11.8% of attending physicians (p<0.01). Close to half of trainee physicians (46.0%) reported that they were not waivered and were uninterested in prescribing buprenorphine for OUD relative to 80.0% of attending physicians (p<0.01).

Figure 1. Beliefs, Interest, and Self-Reported Behaviors related to Prescribing Medication Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder among Primary Care Residents and Physicians (N=547).

Asterisk(*) indicates significant difference (p-value<0.05) and two asterisks(**) indicate significant difference (p<0.01) in the percentage of residents and physicians endorsing each statement tested using Pearson chi-square test. OUD=opioid use disorder. N=547 (211 residents and 336 physicians) a Percent of respondents who agree with each statement include those who selected “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” from the 5-point Likert scale response options. b Percent of interested respondents include those who selected “very interested” or “somewhat interested” from the 5-point Likert scale response options. c Percent of respondents in each category selected from mutually exclusive response options to a single question about prescribing behavior (see Appendix 1). Totals across categories total 100 percent.

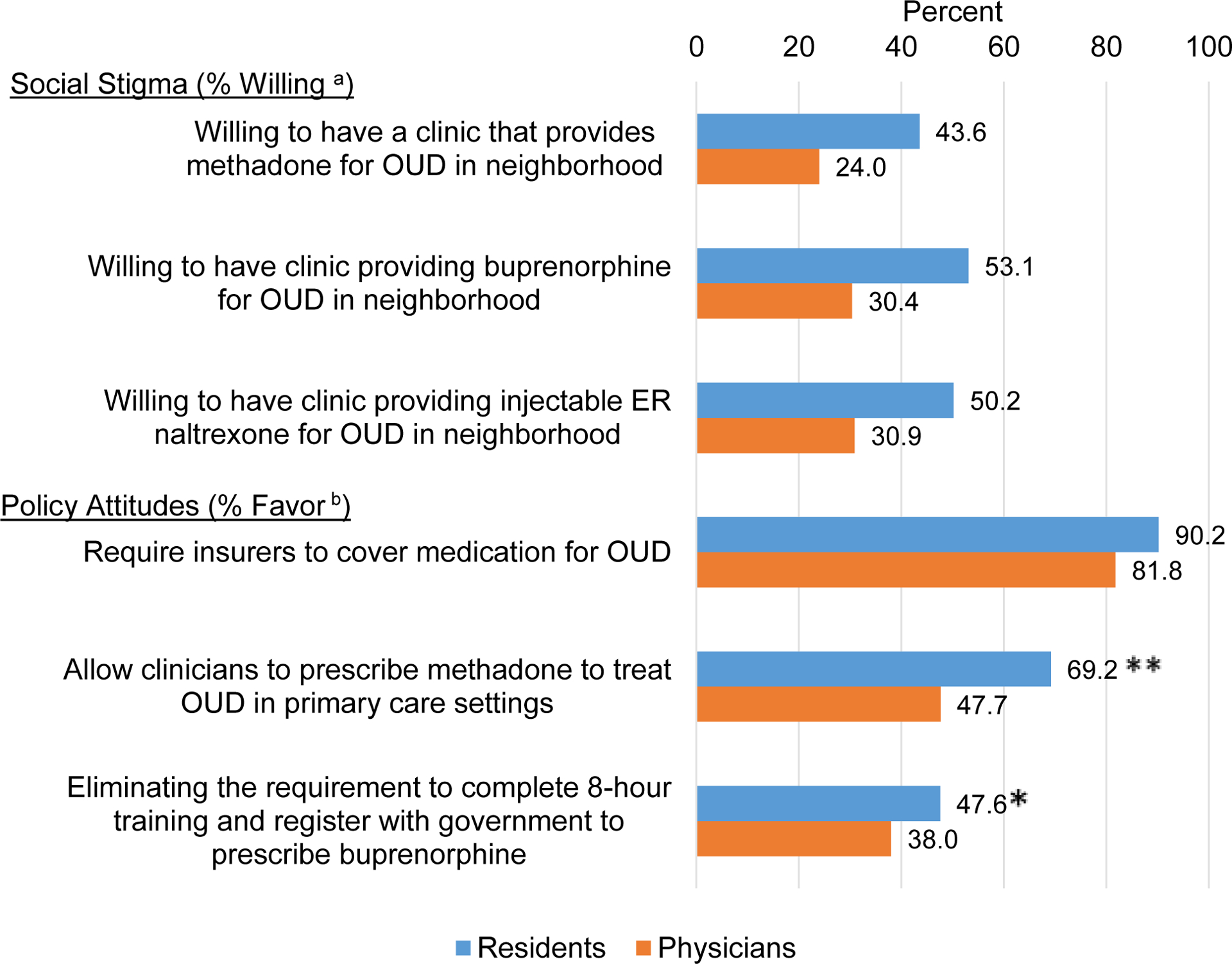

Trainee physicians reported greater willingness than attending physicians to live near providers of all three types of medication Figure 2. Minorities of trainee and attending physicians were willing to have a clinic providing methadone in their neighborhood, with 43.6% of trainee and 24.0% of attending physicians reporting willingness. Both groups expressed slightly greater levels of willingness to have a clinic providing buprenorphine (53.1% of trainee physicians and 30.4% of attending physicians) or naltrexone (50.2% of trainee physicians and 30.9% of attending physicians) located in their neighborhood.

Figure 2. Social Stigma and Policy Support Related to Prescribing Medications for Opioid Use Disorder among Primary Care Residents and Physicians (N=547).

Asterisk(*) indicates significant difference (p-value<0.05) and two asterisks(**) indicate significant difference (p<0.01) in the percentage of residents and physicians endorsing each statement tested using Pearson chi-square test. OUD=opioid use disorder. N=547 (211 residents and 336 physicians) a Percent of willing respondents include those who selected “strongly willing” or “somewhat willing” from the 5-point Likert scale response options. b Percent of respondents in favor of policy include those who selected “strongly favor” or “somewhat favor” from the 5-point Likert scale response options.

Support for policies to broaden access to OUD medications was higher among trainee physicians than among attending physicians. Support in both groups was highest for requiring insurers to provide medication for OUD, with 90.2% of trainee physicians and 81.8% of attending physicians supporting this policy. The largest gap in policy support between trainee and attending physicians was for allowing clinicians to prescribe methadone to treat OUD in primary care settings with 69.2% of trainee physicians and 47.7% of attending physicians favoring this policy. 47.6 percent of trainee physicians and 38.0% of attending physicians favored eliminating the requirement that prescribers undergo additional training and register with the government to prescribe buprenorphine to treat OUD.

4. DISCUSSION

Results from this survey suggest that current primary care trainee physicians, who have trained during this historically devastating overdose crisis, are more inclined than primary care attending physicians to view OUD medications as effective and to express interest in working with this population and prescribing buprenorphine to treat OUD (McGinty et al., 2020). This aligns with data showing that a growing proportion of trainee physicians in family medicine are obtaining buprenorphine waivers (Peterson et al., 2020).

Our findings highlight ongoing areas of concern. Only half of trainee physicians expressed interest in treating patients with OUD and half reported being neither waivered nor interested in becoming waivered to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD. Burdens on clinicians that prescribe medications to treat OUD (e.g., buprenorphine waiver requirements) may pose a barrier to clinician engagement. Yet support for loosening restrictions on prescribing buprenorphine for OUD was mixed despite calls to eliminate the waiver requirements (Fiscella et al., 2019). Notably, support for allowing the prescribing of methadone for OUD treatment in primary care was much higher among both trainee and attending physicians, suggesting potential traction among this group on an issue that has received less attention than reducing barriers to buprenorphine prescribing (Samet et al., 2018).

Although only half of trainee physicians reported willingness to live near various types of OUD medication treatment providers, this percentage was significantly higher than among attending physicians. Limited data exists on NIMBY attitudes. A recent nationally representative survey of the general public measuring levels of support for opening a new OUD medication treatment provider found that support declined from 53 percent to 39 percent – 14 percentage points – when the treatment provider was described as a 5 minute versus 40 minute walk from the respondent’s home (De Benedictis-Kessner and Hankinson, 2019). Ambivalence regarding residence near an OUD medication treatment provider could suggest stigma toward people with OUD, stigma toward the medications, or both. There was little difference within each physician group in level of willingness to live near buprenorphine versus extended-release naltrexone treatment providers, which may be unsurprising given that both medications can be prescribed or administered in non-specialty ambulatory settings. Willingness to live near a methadone treatment provider was moderately lower among both trainee and attending physicians. The opioid treatment programs that provide methadone require daily visits for patients to receive their medication. To the extent survey respondents were aware of this distinction, these moderate differences in levels of willingness could have been related to assumptions about people with OUD aggregating in a defined geographic space in the neighborhood, suggesting stigma toward the people more so than methadone itself. Yet NIMBY attitudes toward methadone treatment providers are long-standing, despite no evidence of negative effects, like heightened crime (Boyd et al., 2012; Furr-Holden et al., 2016).

Results from this study should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, a significant number (n=488) of the 1,000 trainee physicians sampled from the AMA Masterfile were determined ineligible due to incorrect address or specialty. The ineligible percentage among trainee physicians was higher than in the attending physician survey fielded concurrently (McGinty et al., 2020) perhaps due to more frequent change of practice location during their training. Trainee physician respondents were more likely to specialize in family practice than non-responding trainee physicians and relative to the national population of trainee physicians in primary care (49% versus 32%) (see Appendix); we used survey weights to adjust for these differences in specialty between responders and non-responders. Physician trainees in internal medicine often go on to practice in other specialties. It is possible that the trainee physicians specializing in internal medicine who we included in our sampling frame did not perceive themselves as primary care physician trainees and, as a result, were less likely to respond to the survey. We did not collect information on trainee physicians’ intended future practice specialty. These differences in sample composition could have contributed to the differences observed between trainee and attending physicians responding to the survey.

5. CONCLUSION

Primary care trainee physicians are poised to be critical partners in expanding OUD medication treatment capacity and ameliorating the opioid crisis in the U.S. Relative to primary care attending physicians, the emerging cohort of physicians is more receptive to treating patients with OUD. Training on OUD and its treatment, exposure to individuals who have recovered from OUD, and provision of resources and tools to support physicians in treating OUD may help to build skills, heighten enthusiasm for working with patients with OUD, and reduce stigma (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Primary care physicians view opioid use disorder (OUD) medications as effective.

Trainee physicians express greater interest in treating OUD than attendings.

Trainee physicians more receptive to prescribing buprenorphine than attendings.

Primary care physicians unwilling to live near OUD medication treatment providers.

Mixed support for policies to loosen restrictions on OUD medication prescribing.

Role of Funding Source

The study was supported by a Johns Hopkins University Frontier Award (PI: Emma E. McGinty). Elizabeth Stone was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) training grant (T32 MH 109436) while contributing to this study. The study sponsors had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts declared.

REFERENCES

- Bernstein S, Bennett D, 2013. Zoned Out: “NIMBYism”, addiction services and municipal governance in British Columbia. Int J Drug Policy 24, e61–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd SJ, Fang LJ, Medoff DR, Dixon LB, Gorelick DA, 2012. Use of a “microecological technique” to study crime incidents around methadone maintenance treatment centers. Addiction 107, 1632–1638. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03872.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Benedictis-Kessner J, Hankinson M, 2019. Concentrated Burdens: How Self-Interest and Partisanship Shape Opinion on Opioid Treatment Policy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev 113, 1078–1084. 10.1017/S0003055419000443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Wakeman SE, Beletsky L, 2019. Buprenorphine Deregulation and Mainstreaming Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: X the X Waiver. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 229–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden CDM, Milam AJ, Nesoff ED, Johnson RM, Fakunle DO, Jennings JM, Thorpe RJ, 2016. Not in my back yard: A comparative analysis of crime around publicly funded drug treatment centers, liquor stores, convenience stores, and corner stores in one Mid-Atlantic City. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 77, 17–24. 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffajee RL, Bohnert ASB, Lagisetty PA, 2018. Policy Pathways to Address Provider Workforce Barriers to Buprenorphine Treatment. Am. J. Prev. Med 54, S230–S242. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Bachhuber MA, Barry CL, 2020. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder: A National Survey of Primary Care Physicians. Ann Intern Med. Published online 21 April 2020. 10.7326/M19-3975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC: 10.17226/25310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2016. Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: The evidence for stigma change, Ending Discrimination Against People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: The Evidence for Stigma Change. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC: 10.17226/23442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson LE, Morgan ZJ, Eden AR, 2020. Early-Career and Graduating Physicians More Likely to Prescribe Buprenorphine. J. Am. Board Fam. Med 33, 7–8. 10.3122/jabfm.2020.01.190230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Botticelli M, Bharel M, 2018. Methadone in Primary Care — One Small Step for Congress, One Giant Leap for Addiction Treatment. N. Engl. J. Med 379, 7–8. 10.1056/NEJMp1803982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2020. Practitioner and Program Data [WWW Document]. SAMHSA Medicat. Treat website. URL https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/training-materials-resources/practitioner-program-data (accessed 3.13.20). [Google Scholar]

- Tesema L, Marshall J, Hathaway R, Pham C, Clarke C, Bergeron G, Yeh J, Soliman M, McCormick D, 2018. Training in office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine in US residency programs: A national survey of residency program directors. Subst. Abus 39, 434–440. 10.1080/08897077.2018.1449047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, Beletsky L, Keyes KM, McGinty EE, Smith LR, Strathdee SA, Wakeman SE, Venkataramani AS, 2019. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLOS Med 16, e1002969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, Van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL, 2013. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 131, 23–35. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.