Abstract

Background

Oral cancer (OC) is a neoplastic process of the oral cavity that has high mortality and significant effects on patients’ aesthetics. The majority of OC is oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and resection remains the most frequent treatment. Recurrence is the main cause of tumor-related mortality.

Material and methods

A retrospective review of patients’ charts at Hamad Medical Corporation examined 154 adults who were diagnosed as OSCC and referred to the national head and neck cancer multi-disciplinary team meetings between 2012 and 2018. The data extracted was demographic, pathologic and clinical. All patients with oral cavity tumors other than squamous cell carcinoma were excluded.

Results

Males comprised the majority of the sample, mean age was 46.93 years. Tongue was the most common location. The majority of the patients were diagnosed at early stages, and a small subset of patients had histologically-proven local recurrence.

Conclusion

The young male predominance of OSCC patients in Qatar is unprecedented worldwide. Most patients were non-Qataris, mainly from South Asia. Loss of follow-up was a challenge in assessing the long-term outcomes of OSCC. Our findings suggest the need for a more vigilant surveillance approach to oral lesions particularly in male South-Asian patients, as well as improving the follow-up strategies.

Keywords: Oral cancer, Squamous cell carcinoma, Multi-ethnic, Surgical resection margin evaluation, Head and neck cancer

Highlights

-

•

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common type of oral cancer.

-

•

There is no published data about OSCC in Qatar, despite its ethnically diverse population.

-

•

We reviewed the charts of all OSCC adult patients in Qatar between 2012- 2018 and studied multiple parameters.

-

•

Results showed unprecedented young male predominance, mainly South Asian expats. Loss of follow-up was a major limitation.

-

•

Our findings suggest the need for more vigilant surveillance to oral lesions particularly in male South-Asians.

1. Introduction

Oral cancer (OC) is a neoplastic process of the oral cavity (from the lips to the fauceses’ anterior pillars) [1] that affects males more than females [2]. It is a global public health issue as it is the eighth most common cancer (>300,000 cases annually) [3], characterized by its high mortality and multiple effects on aesthetics of patients [1]. The incidence and mortality rates of OC vary globally and are higher in developing nations, particularly India and other South/eastern Asia regions, France, Slovenia, Slovakia and Hungary [2,4,5]. Such incidence and mortality differences between high- and low-income countries, and the increased OC related mortality in societies with low-development and high societal disparities suggest that society-related factors e.g., culture and lifestyle influence its tumorigenesis [2,6]. The southeast Asian population in particular has higher rates of OC due to the cultural habit of consuming raw chewable tobacco, especially betel quid [6].

About 90–95% OC is oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [7], classified into 3 Grades, from well-differentiated (Grade I) to poorly-differentiated (Grade III) [8]. Curative resection and reconstruction remain the most frequent treatment to maintain the form and function of the head and neck area [1]. Despite recent breakthroughs in treatment modalities, OSCC still has poor prognosis, due to local aggressiveness and metastasis, where recurrence arises in ≈30% of cases [9]. Local and regional recurrences are the main cause of OSCC-related mortality, where the 5-year survival drops from 92% in recurrence-free patients to 30% in patients with recurrence [9,10].

The literature reveals several gaps. First, in terms of breadth, some studies assessed the clinical and pathological features of OSCC [6,[11], [12], [13]], others focused only on surgical aspects [e.g., [10, 14, 15]]; with few studies simultaneously considering the clinical, epidemiological, histopathological and surgical parameters in order to gauge prognosis [e.g., 11, 16, 18]. Likewise, there remains debate about histology-based vs clinical-based risk-assessment scoring systems in predicting prognosis [5,8,16,17]. Second, some studies assessed only tongue OSCC [5,18,19], despite that floor of the mouth is a common OSCC site [8,16]. Third, in terms of stage, research focused on early stages of OSCC [e.g., 18,19], despite evidence linking advanced OSCC stages to poorer prognosis [12]. Fourth, with a few exceptions [13,15,20], many studies had modest sample sizes (17–126 patients) [8,10,12,19,[21], [22], [23], [24]]. Fifth, most studies did not have representative samples of the countries they were conducted in, comprising single center studies [8,12,13,15], with rare exceptions of single country multi-center studies [19,20,23]. Sixth, with few exceptions [5,12], most investigations were among ethnically homogenous populations [6,13], despite evidence linking certain racial groups to poorer prognosis [[25], [26], [27]]. Seventh, there is paucity of OSCC literature from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and sub-Saharan Africa. Many MENA countries lack national cancer reporting systems [7], and OSCC management and outcomes data were absent in many sub-Saharan studies [28]. Likewise, few studies assessed the relationship between age and OSCC prognosis, despite the reported inconsistency in the relationship between age and OSCC prognosis [12,16,[29], [30], [31]]. In addition, no literature investigated the association between age and perineural invasion and lymphovascular invasion as independent prognostic factors, despite their importance in prognosis and management [3]. Finally, research assessed the associations between recurrence, and tumor size, stage, and margins [e.g., 12,23], but no literature examined the possible association between local recurrence and age.

There is no published data about OSCC for the State of Qatar, despite its ethnically diverse population [32]. Therefore, this retrospective study at the sole reference center in Qatar reviewed all OSCC cases of all stages (January 2012–December 2018) involving any location of the oral cavity, employing a generous sample size (154 ethnically diverse patients) and examined a wide range of demographic, clinical, epidemiological, histopathological and surgical parameters. The specific objectives were to assess:

-

●

A range of demographic, clinical, epidemiological, histopathological and surgical characteristics of OSCC;

-

●

Associations between local recurrence and tumor site, age group, stage [T-stage] and nodal metastasis (N-stage); and,

-

●

Associations between age group and pathologic stage (T-stage), nodal metastasis (N-stage), histological grade, lymphovascular invasion and perineural invasion.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Ethics, settings and study design

This study was approved by the medical research center/Institutional research board (IRB) at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) (protocol number MRC-01-20-136). This is a retrospective study of patients' charts at Hamad General Hospital, Doha (largest tertiary care center in Qatar) and Rumailah Hospital, Doha (multi-specialty center that includes Qatar's reference ENT, cranial and maxillofacial departments), both part of HMC. We report this study in accordance with the STROCCS criteria [33].

2.2. Study population

All OSCC cases in Qatar are mandated to come through the national head and neck cancer multidisciplinary team (MDT). All cases that were referred to the MDT between 2012 and 2018 with histologically confirmed diagnosis of OSCC were included in the study (154 adults, some of which were diagnosed prior to 2012 but referred to the MDT from 2012 for follow-up).

2.3. Data collection

We reviewed the hospital charts of all OSCC patients who were referred to the MDT (January 2012–December 2018) and extracted the necessary data, mainly from histopathology reports and surgical notes. The data included were demographic (gender, age, nationality), pathologic (tumor anatomical site, histological variant of SCC, grade, depth of invasion, pTNM stage, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, margin status and tumor bed status), as well as clinical (follow-up period and histologically–proven recurrence). The follow-up was calculated starting from the initial surgery untill the patient's last visit to HMC, with any period lasting between 6 months and 1 year counted as 0.5. Local recurrence was defined as histologically-proven re-emergence of the OSCC within 3 years after initial surgery [19]. Any OSCC after more than 3 years was considered a metachronous primary tumor [second primary].

2.4. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients who had histologically-proven squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity that were referred to the Head and Neck cancer “MDT” between January 2012–December 2018 were included in the study. All patients with oral cavity tumors other than squamous cell carcinoma were excluded, as well as patients with squamous cell carcinoma in anatomical sites of the head and neck other than oral cavity.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package SPSS v20 transferred. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentage; continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviation. Chi-square test assessed the relationships between categorical variables (Age group against each of: T-stage, N-stage, grade, lymphovascular and perineural invasion; as well as local recurrence against each of: tumor site, age group, T- and N-stage). Significance level was set at p < 0.05. The distribution of some variables e.g. depth of invasion (DOI) was skewed to the left, so the median is used.

3. Results

Table 1 shows selected demographic characteristic of the sample. Males were a majority, mean age was 46.93 years, with nearly equally-distributed age brackets. South Asian nationalities comprised about two-thirds of the sample. Patients from India comprised more than one third of the sample (39.6%), followed by Pakistanis (9.7%) then Qatari nationals and Bangladeshi (7.8% each) (data not presented).

Table 1.

Selected demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 154).

| Characteristic | Number of cases* | Value = N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (N %) | 154 | |

| Male | 141 (91.6) | |

| Female | 13 (8.6) | |

| Male to female ratio | 10.9:1 | |

| Age group at diagnosis (years) | 154 | |

| < 40 | 48 (31.2) | |

| 41-50 | 54 (35.1) | |

| > 50 | 52 (33.8) | |

| Age at diagnosis (years, Ma ± SDb) | 154 | 46.93 ± 12.304 |

| Nationality group | 154 | |

| Middle East and North Africac | 36 (23.4) | |

| South Asiand | 104 (67.5) | |

| Rest of the worlde | 14 (9.1) |

*Number of cases with data available for analysis.

Mean.

Standard Deviation.

Including Iran.

Including Philippines.

Including Sudan.

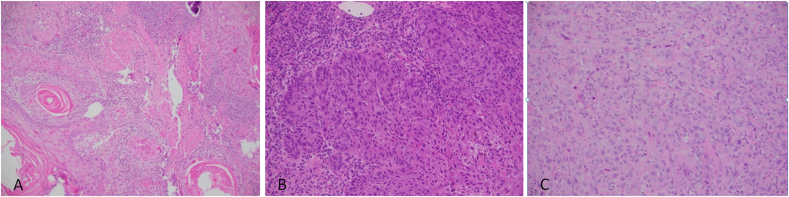

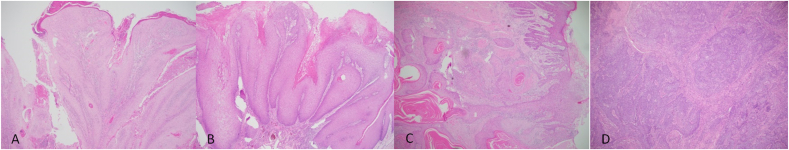

Table 2 depicts selected specimen and tumor characteristics of the sample. The majority of patients had resections, while less had biopsies only. The most common location of primary tumor was the tongue (50% of cases), followed by the buccal mucosa, and mean DOI was 8.8 mm (Median DOI = 7 mm). A majority of the OSCC was of the conventional variant (Fig. 1), and grade 2 was the most common histological grade, comprising about half the cases (Fig. 2). Where data was available, most cases exhibited no lymphovascular invasion, but perineural invasion was found in more than one third of the patients. Most of the sample had surgical negative margins; however, about half the patients had close margins (i.e. negative, but < 5 mm). For all patients where a tumor bed specimen was submitted, only one case had a positive tumor bed margin. Mean follow up period was 2.38 years. Of the patients who underwent surgery, only a minority had histologically-proven recurrence, however 40.7% of patients were lost to follow-up (and therefore their recurrence status unknown).

Table 2.

Selected specimen and tumor characteristics of the sample (N = 154).

| Characteristic | Number of cases* | Value = N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Specimen | ||

| Specimen type | 152 | |

| Biopsy | 52 (34.2) | |

| Resection | 100 (65.8) | |

| Tumor | ||

| Location of primary tumor (detailed) | 154 | |

| Border of tongue | 77 (50) | |

| Floor of mouth/ventral tongue | 7 (4.5) | |

| Buccal mucosa/buccal sulcus | 47 (30.5) | |

| Soft palate/tonsil area | 5 (3.2) | |

| Alveolar mucosa/gingiva/retro molar area | 4 (2.6) | |

| Lower lip | 7 (4.5) | |

| Buccogingival | 3 (1.9) | |

| Maxillary sinus and hard palate | 1 (0.6) | |

| Tongue base, floor of mouth and epiglottis | 3 (1.9) | |

| Location of the primary tumor (groups) | 154 | |

| Buccal mucosa and palate | 59 [38.3) | |

| Tongue | 82 [53.2) | |

| Lip | 7 [4.5) | |

| Floor of mouth and maxilla | 6 [3.9) | |

| Depth of invasion (Ma ± SDb, mm) | 8.799 ± 6.2 | |

| Depth of invasion (MEDc ± SDb, mm) | 7 ± 6.2 | |

| Pathological staging (pTN)d | 102 | |

| Histological grading | 154 | |

| Grade 1 | 45 (29.2) | |

| Grade 2 | 77 (50) | |

| Grade 3 | 32 (20.8) | |

| Lymphovascular invasione | 100 | |

| Yes | 13 (13) | |

| No | 87 (87) | |

| Perineural invasione | 109 | |

| Yes | 42 (38.5) | |

| No | 67 (61.5) | |

| Dysplasia | 153 | |

| Yes | 21 (13.7) | |

| No | 132 (86.3) | |

| Surgical marginsd | 104 | |

| Positive | 11 (10.6) | |

| Negative | 39 (37.5) | |

| Close | 54 (51.9) | |

| Tumor bed margind | 97 | |

| Not submitted | 15 (15.5) | |

| Submitted positive | 1 (1) | |

| Submitted negative | 81 (83.5) | |

| Histological variants of OSCCf | 154 | |

| Conventional | 150 (97.4) | |

| Verrucous | 1 (0.6) | |

| Basaloid | 1 (0.6) | |

| Keratoacanthoma-like variant | 1 (0.6) | |

| Hybrid (verrucous with conventional) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Follow up (Ma ± SDb, years) | 100 | 2.38 ± 1.86 |

| Recurrenced | 103 | |

| Yes | 12 (11.7) | |

| No | 49 (47.6) | |

| Unknowng | 42 (40.8) | |

*Number of cases with data available for analysis.

Mean.

Standard Deviation.

Median.

For resection specimens only.

Only for cases for which data was available.

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

Patients who were followed for < 3 years or died < 3 years after surgery with cause of death unavailable.

Fig. 1.

SCC grades. A: HE stained section × 200 magnification showing grade 1 SCC, B: HE stained section × 200 magnification showing grade 2 SCC and C: HE stained section × 200 magnification showing grade 3 SCC.

Fig. 2.

SCC variants. A: HE stained section × 40 magnification showing keratoacanthoma-like variant, B: HE stained section × 40 magnification showing verrucous variant, C: HE stained section × 40 magnification showing conventional variant and D: HE stained section × 40 magnification showing basaloid variant.

Table 3 shows the pathological staging of the sample. The majority of patients had early stage disease, and about half the sample had no lymph node metastasis. Due to the large number of combined stage values, the pathological staging was further categorized into T-stage (primary tumor) and N-stage (nodal metastasis). Patients with early T-stage disease (T1 and T2) comprised more than half the sample (39.8% and 26.2% respectively). About half of the patients had no nodal metastasis.

Table 3.

Pathological staging (pTN) of the samplea (N = 154).

| Characteristic | Number of cases* | Value = N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| pTN | 102 | |

| T1N0 | 24 (23.5) | |

| T1N1 | 3 (2.9) | |

| T1N2 | 0 (0) | |

| T1N2B | 3 (2.9) | |

| T1NX | 8 (7.8) | |

| T2N0 | 13 (12.7) | |

| T2N1 | 9 (8.8) | |

| T3N0 | 7 (6.9) | |

| T3N1 | 6 (5.9) | |

| T3N2 | 1 (1) | |

| T3N2A | 1 (1) | |

| T3N2B | 1 (1) | |

| T3N3B | 1 (1) | |

| T3NX | 1 (1) | |

| T4N0 | 6 (5.9) | |

| T4N1 | 0 (0) | |

| T4N2 | 0 (0) | |

| T4N2B | 2 (2) | |

| T4N2C | 1 (1) | |

| T4N3B | 2 (2) | |

| T4NX | 0 (0) | |

| TXN0 | 2 (2) | |

| TXNX | 3 (2.9) | |

| T-stage | 103 | |

| T1 | 41 (39.8) | |

| T2 | 27 (26.2) | |

| T3 | 18 (17.5) | |

| T4 | 11 (10.7) | |

| TX | 6 (5.8) | |

| N-stage | 103 | |

| N0 | 52 (50.5) | |

| N1 | 18 (17.5) | |

| N2 | 1 (1) | |

| N2A | 1 (1) | |

| N2B | 12 (11.7) | |

| N2C | 1 (1) | |

| N3 | 0 (0) | |

| N3B | 3 (2.9) | |

| NX | 15 (14.6) |

* Number of cases with data available for analysis.

For resection specimens only.

We explored the relationship between age groups and multiple parameters through chi-square test. No statistically significant association was identified between age groups and T-stage (χ2 = 13.092, df = 8, P = 0.109), N-stage (χ2 = 13.095, df = 14, P = 0.514), grade (χ2 = 5.991, df = 4, P = 2), lymphovascular invasion (χ2 = 1.141, df = 2, P = 0.565) or perineural invasion (χ2 = 13.092, df = 8, P = 0.109).

We also explored the relationship between local recurrence and multiple parameters through chi-square test. No statistically significant association was identified between local recurrence and the following parameters: tumor site (χ2 = 2.001, df = 3, P = 0.572), age group (χ2 = 2.897, df = 2, P = 0.235), T-stage (χ2 = 3.493, df = 4, P = 0.479) and N-stage (χ2 = 1.684, df = 5, P = 0.891).

4. Discussion

This study assessed the epidemiological, demographic, clinical, epidemiological, histopathological and surgical characteristics of OSCC in Qatar. In terms of gender, the majority of our patients were males, with a M:F ratio of ≈10.9:1. Hence our findings support that OSCC has a male predominance globally [13]. The global OSCC M:F ratio is about 5.5:2.5 [34], ranging from 1.2:1 [5] to 3.02:1 [16]. Such range is similar to most Arab nations [7]. Our OSCC M:F ratio was the highest worldwide, probably due to the unique demographics in Qatar. The large numbers of single young male workers and expats working in Qatar have resulted in a country having has the highest M:F ratio worldwide (3.15:1) [32].

As for age, globally, most OSCC patients are >45 years of age at first diagnosis [median 62 years], with only 6% of patients < 45 years [12]. In contrast, about one third of our patients were <41 years, a proportion that is significantly higher than other studies globally [6,9,13] and regionally [20]. Our sample's mean age was 46.9 years (range 18–78), suggesting that OSCC patients in Qatar are slightly younger than their counterparts in the region [7]. Again, this is probably because the majority of the population in Qatar are young and middle-aged individuals [32]. Although data about patients' lifestyle habits that may pose a risk of developing OSCC were not available, we speculate that many of the young patients in our study carried some risk (e.g. tobacco or betel quid chewing) from their original homelands (especially South Asian countries). This speculation is based upon literature studying OC risk factors in South Asian countries [6] and similar expat groups in the region [7]. In terms of nationality, most patients were not Qatari nationals. Indians comprised largest proportion of OSCC our patients (39.6%), reflecting the country's demographics, as Indians are the largest ethnic group of the expat population living in Qatar [35]. Individuals from South Asian countries were also well represented, in agreement with the higher OSCC incidence in South Asia [5].

The most common site of primary tumor in the current study was the tongue (53.2%), in contrast with other studies where buccal mucosa was the most common location, especially in South Asians [e.g., 16]. Nevertheless, our finding is in concordance with most of published literature, where the tongue was the most common [7,12,13,15,36].

The current study observed a mean DOI of 8.8 mm (median 7 mm, range 1.5–25 mm), slightly deeper than the 5.7 mm mean DOI reported in United Kingdom [12] and 6.3 mm in Finland [37], although it was less than the 12.9 mm reported in one international multicenter study [38]. DOI in OSCC is an important variable in predicting nodal metastasis and hence it impacts on the management and prognosis [39].

Pathological staging is a prognostic factor, where the T-stage (primary tumor) is an important factor in selecting the management option and predicting nodal metastasis, recurrence and survival [12]. A majority of our sample (66%) was early stage (T1 and T2), probably attributed to an efficient cancer referral system in Qatar that is vigilant for suspected cancer patients, and hence the early referral and detection. However, the N-stage is also another key prognostic factor, where generally, about half the OSCC patients have nodal metastasis at diagnosis [40]. Across our sample, 50.5% of patients who underwent resection had no nodal metastasis, while 17.5% were N1 stage. A proportion of patients who underwent resection [14.6%] did not undergo neck dissection at surgery, and subsequently were classified as NX. Our practice is in line with others, where the decision to sample cervical lymph nodes is usually based upon the primary tumor [T-stage], with the T1 patients spared from neck dissection if radiologically not suspicious [3]. Therefore, our finding of NX patients is probably due to the early stage nature of the disease among the majority of our sample.

The World Health Organization's classification grades OSCC as well differentiated (Grade 1), moderately differentiated (Grade 2) and poorly differentiated (Grade 3), based upon the pathologist's evaluation of keratinization, pleomorphism, and mitosis [12]. Globally, whilst many OSCC are of low histological grade, grade 2 moderately differentiated tumors form the majority of cases [13,15]. The current study is in agreement, since the majority of patients (50%) were grade 2 followed by grade 1 (29.2%) [Fig. 1]. Some researchers employ grade as a part of the risk-assessment to predict prognosis and survival [17].

In terms of the histological variants of OSCC, some authors have linked particular variants with better prognosis and other variants with less favorable outcomes [41]. Generally, the conventional variant comprises a majority of the cases, with other variants involving up to 15% of cases [42]. We are in support, the conventional variant in the present study comprised a majority (97.4%), with each of the other six variants each having a single case (0.6% each) (Fig. 2).

The margin status in the main resection specimen has special significance since its involvement is a negative prognostic factor, implying increased recurrence and poorer survival [18]. Of the resection cases in the current study, 10.6% had positive margin in the main resection specimen, 37.5% had negative margin (>5 mm clearance), and more than half had close margin [negative but < 5 mm clearance]. Our proportion of cases with close margins was higher than other studies [e.g., 5,12], probably due to the high dependence of surgeons at our institution on the tumor bed margin frozen section [performed in 84.5% of eligible cases] that provides surgeons with high certainty of the completeness of the excision. Such certainty is evidenced by that across our sample, tumor bed was submitted for frozen section in 84.5% of eligible cases, and of those which were submitted, only one case was positive while all remaining cases were negative. Notwithstanding, the importance of intraoperative margin sampling and examination by frozen section (tumor bed margin sampling) to outcomes remains controversial, with some authors suggesting that this practice has no effect on survival and outcome [15].

A body of research defines follow-up for recurrence and survival at 3- and 5-year milestones [e.g., 12] with a minority implementing a 2- and 5-year time points [9]. In our 100 resection cases where follow-up data was available, mean follow-up period was 2.38 years, slightly less than the 3 years criteria, probably attributed to the fact that most of our OSCC patients were not Qataris, with many returning to their home countries after initial treatment in Qatar.

Local recurrence is a key prognostic factor in OSCC patients where some authors reported a median survival drop from 6.4 years in recurrence-free patients to 3.5 years in those with recurrence [9]. Recurrence influences both the 5-year and the disease-free survival in OSCC patients [8]. Of the resection cases in our study, 11.7% had histologically-proven recurrence, 47.6% were recurrence-free after ≥3 years of follow-up, and 40.8% had unknown recurrence (lost follow-up before reaching the 3-year milestone).

Statistical analysis yielded no significant association between local recurrence and each of tumor site, age group, T- and N-stage. This can be attributed to the limited number of cases with local recurrence and the significant portion of patients who were lost to follow-up.

The study has limitations. Better data quality about survival would have been beneficial. Smoking history and recreational habits (e.g., tobacco chewing) were not regularly documented, which would have been useful in investigating possible risk factors. A major challenge was the loss of follow-up, due to the mobile expat nature of the population in Qatar, where many expat patients are lost to follow-up due to relocation. Better data regarding survival and loss of follow would have enabled the examination of mortality, an important parameter in cancer studies. Only one of our patients was recorded as deceased, and we were unable to verify whether the death was OSCC-related. These factors, along with the categorical nature of variables under examination did not enable the generation of Kaplan Meier survival curves. Nevertheless, the study has important strengths. There is no published data about OSCC for the State of Qatar, despite its ethnically diverse population. We employed a generous sample (154 patients) and examined a wide range of demographic, clinical, epidemiological, histopathological and surgical parameters. Our sample is inclusive of all cases in the country as our center is the sole reference center in Qatar that reviews all OSCC cases of all stages involving any location of the oral cavity.

5. Conclusion

The young male predominance of OSCC patients in Qatar is unprecedented worldwide. Most patients were non-Qataris, mainly from South Asia. Although most patients had negative margins upon resection, a majority of these margins were close. A small subset of patients had histologically-proven local recurrence, but loss of follow-up was a challenge in assessing the long-term outcomes of OSCC. No significant association was found between age group and local recurrence against multiple parameters. Our findings suggest the need for a more vigilant surveillance approach to oral lesions particularly in male South-Asian patients, as well as improving the follow-up strategies.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was given by the medical research center/Institutional research board (IRB) at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Doha, Qatar (protocol number MRC-01-20-136).

Consent

Since it is a retrospective study, the consent of the patient was not required for the study.

Registration of research studies

-

1.

Name of the registry: Research Registry

-

2.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: researchregistry6065

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.researchregistry.com/register-now#home/registrationdetails/5f73498aa635f000150d5c5c/

Guarantor

Prof Dr Walid El Ansari.

Author contribution

Study design and conception: AA, OE and MAl-K. Data collection: OE. Data analysis: OE and W El A.Writing the paper: OE and W El A. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.10.029.

Contributor Information

Orwa Elaiwy, Email: OElaiwy@hamad.qa.

Walid El Ansari, Email: welansari9@gmail.com.

Moustafa AlKhalil, Email: Malkhalil@hamad.qa.

Adham Ammar, Email: AAmmar1@hamad.qa.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Omura K. Current status of oral cancer treatment strategies: surgical treatments for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10147-014-0689-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivera C. Essentials of oral cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.192487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Cruz A.K., Vaish R., Dhar H. Oral cancers: current status. Oral Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta N., Gupta R., Acharya A.K., Patthi B., Goud V., Reddy S., Garg A., Singla A. Changing Trends in oral cancer – a global scenario. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2017 doi: 10.3126/nje.v6i4.17255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodrigues P.C., Miguel M.C.C., Bagordakis E., Fonseca F.P., De Aquino S.N., Santos-Silva A.R., Lopes M.A., Graner E., Salo T., Kowalski L.P., Coletta R.D. Clinicopathological prognostic factors of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study of 202 cases. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iamaroon A., Pattanaporn K., Pongsiriwet S., Wanachantararak S., Prapayasatok S., Jittidecharaks S., Chitapanarux I., Lorvidhaya V. Analysis of 587 cases of oral squamous cell carcinoma in northern Thailand with a focus on young people. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004 doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Jaber A., Al-Nasser L., El-Metwally A. Epidemiology of oral cancer in Arab countries. Saudi Med. J. 2016 doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.3.11388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Castro Ribeiro Lindenblatt R., Martinez G.L., Silva L.E., Faria P.S., Camisasca D.R., de Queiroz Chaves Lourenço S. Oral squamous cell carcinoma grading systems - analysis of the best survival predictor. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang B., Zhang S., Yue K., Wang X.D. The recurrence and survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a report of 275 cases. Chin. J. Canc. 2013 doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C.H., Chen H.J., Wang P.C., Sen Chen H., Chang Y.L. Patterns of recurrence and second primary tumors in oral squamous cell carcinoma treated with surgery alone. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arduino P.G., Carrozzo M., Chiecchio A., Broccoletti R., Tirone F., Borra E., Bertolusso G., Gandolfo S. Clinical and histopathologic independent prognostic factors in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study of 334 cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jerjes W., Upile T., Petrie A., Riskalla A., Hamdoon Z., Vourvachis M., Karavidas K., Jay A., Sandison A., Thomas G.J., Kalavrezos N., Hopper C. Clinicopathological Parameters, Recurrence, Locoregional and Distant Metastasis in 115 T1-T2 Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Head Neck Oncol; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pires F.R., Ramos A.B., de Oliveira J.B.C., Tavares A.S., de Luz P.S.R., dos Santos T.C.R.B. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features from 346 cases from a single oral pathology service during an 8-year period. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1590/1679-775720130317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson C.R., Sisson K., Moncrieff M. A meta-analysis of margin size and local recurrence in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchakjian M.R., Tasche K.K., Robinson R.A., Pagedar N.A., Sperry S.M. JAMA Otolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 2016. Association of main specimen and tumor bed margin status with local recurrence and survival in oral cancer surgery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dissanayaka W.L., Pitiyage G., Kumarasiri P.V.R., Liyanage R.L.P.R., Dias K.D., Tilakaratne W.M. Clinical and histopathologic parameters in survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandwein-Gensler M., Teixeira M.S., Lewis C.M., Lee B., Rolnitzky L., Hille J.J., Genden E., Urken M.L., Wang B.Y. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: histologic risk assessment, but not margin status, is strongly predictive of local disease-free and overall survival. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005 doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000149687.90710.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maxwell J.H., Thompson L.D.R., Brandwein-Gensler M.S., Weiss B.G., Canis M., Purgina B., Prabhu A.V., Lai C., Shuai Y., Carroll W.R., Morlandt A., Duvvuri U., Kim S., Johnson J.T., Ferris R.L., Seethala R., Chiosea S.I. JAMA Otolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 2015. Early oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma sampling of margins from tumor bed and worse local control. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang A.M.V., Kim S.W., Duvvuri U., Johnson J.T., Myers E.N., Ferris R.L., Gooding W.E., Seethala R.R., Chiosea S.I. Early squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue: comparing margins obtained from the glossectomy specimen to margins from the tumor bed. Oral Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Rawi N.H., Talabani N.G. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: a case series analysis of clinical presentation and histological grading of 1,425 cases from Iraq. Clin. Oral Invest. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0141-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho M.W., Field E.A., Field J.K., Risk J.M., Rajlawat B.P., Rogers S.N., Steele J.C., Triantafyllou A., Woolgar J.A., Lowe D., Shaw R.J. Outcomes of oral squamous cell carcinoma arising from oral epithelial dysplasia: rationale for monitoring premalignant oral lesions in a multidisciplinary clinic. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varvares M.A., Poti S., Kenyon B., Christopher K., Walker R.J. Surgical margins and primary site resection in achieving local control in oral cancer resections. Laryngoscope. 2015 doi: 10.1002/lary.25397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillon J.K., Brown C.B., McDonald T.M., Ludwig D.C., Clark P.J., Leroux B.G., Futran N.D. How does the close surgical margin impact recurrence and survival when treating oral squamous cell Carcinoma? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jinnouchi S., Kaneko K., Tanaka F., Tanaka K., Takahashi H. Surgical outcomes in cases of postoperative recurrence of primary oral cancer that required reconstruction. Acta Med. Nagasaki. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moles D.R., Fedele S., Speight P.M., Porter S.R. The unclear role of ethnicity in health inequalities: the scenario of oral cancer incidence and survival in the British south Asian population. Oral Oncol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daraei P., Moore C.E. Racial disparity among the head and neck cancer population. J. Canc. Educ. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osazuwa-Peters N., Massa S.T., Christopher K.M., Walker R.J., Varvares M.A. Race and sex disparities in long-term survival of oral and oropharyngeal cancer in the United States. J. Canc. Res. Clin. Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faggons C.E., Mabedi C., Shores C.G., Gopal S. Review: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in sub-saharan Africa. Malawi Med. J. 2015 doi: 10.4314/mmj.v27i3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garavello W., Spreafico R., Gaini R.M. Oral tongue cancer in young patients: a matched analysis. Oral Oncol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montoro JRMC, Ricz HA, de Souza L, Livingstone D, Melo DH, Tiveron RC, Mamede RCM. Prognostic factors in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/s1808-8694(15)30146-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers S.N., Brown J.S., Woolgar J.A., Lowe D., Magennis P., Shaw R.J., Sutton D., Errington D., Vaughan D. Survival following primary surgery for oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alrouh H., Ismail A., Cheema S. Demographic and health indicators in Gulf Cooperation Council nations with an emphasis on Qatar. J. Local Glob. Heal. Perspect. 2013 doi: 10.5339/jlghp.2013.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Vella-Baldacchino M., Thavayogan R., Orgill D.P., Pagano D., Pai P.S., Basu S., McCaul J., Millham F., Vasudevan B., Leles C.R., Rosin R.D., Klappenbach R., Machado-Aranda D.A., Perakath B., Beamish A.J., Thorat M.A., Ather M.H., Farooq N., Laskin D.M., Raveendran K., Albrecht J., Milburn J., Miguel D., Mukherjee I., Valmasoni M., Ngu J., Kirshtein B., Raison N., Boscoe M., Johnston M.J., Hoffman J., Bashashati M., Thoma A., Healy D., Orgill D.P., Giordano S., Muensterer O.J., Kadioglu H., Alsawadi A., Bradley P.J., Nixon I.J., Massarut S., Challacombe B., Noureldin A., Chalkoo M., Afifi R.Y., Agha R.A., Aronson J.K., Pidgeon T.E. The STROCSS statement: strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.08.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adel P.J.S., EINaggar K., Chan John K.C., Grandis Jennifer R., Takata Takashi. 2017. WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Bel-Air F. Demography, Migration, and Labour Market in Qatar. Gulf Labour Mark. Migr.; 2014. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/32431 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maleki D., Ghojazadeh M., Mahmoudi S.S., Mahmoudi S.M., Pournaghi-Azar F., Torab A., Piri R., Azami-Aghdash S., Naghavi-Behzad M. Epidemiology of oral cancer in Iran: a systematic review. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP. 2015 doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.13.5427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almangush A., Leivo I., Siponen M., Sundquist E., Mroueh R., Mäkitie A.A., Soini Y., Haglund C., Nieminen P., Salo T. Evaluation of the budding and depth of invasion (BD) model in oral tongue cancer biopsies. Virchows Arch. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00428-017-2212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebrahimi A., Gil Z., Amit M., Yen T.C., Liao C.T., Chaturvedi P., Agarwal J.P., Kowalski L.P., Kreppel M., Cernea C.R., Brandao J., Bachar G., Bolzoni Villaret A., Fliss D., Fridman E., Robbins K.T., Shah J.P., Patel S.G., Clark J.R. JAMA Otolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 2014. Primary tumor staging for oral cancer and a proposed modification incorporating depth of invasion: an international multicenter retrospective study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brockhoff H.C., Kim R.Y., Braun T.M., Skouteris C., Helman J.I., Ward B.B. Correlating the Depth of Invasion at Specific Anatomic Locations with the Risk for Regional Metastatic Disease to Lymph Nodes in the Neck for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Head Neck; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wreesmann V.B., Katabi N., Palmer F.L., Montero P.H., Migliacci J.C., Gönen M., Carlson D., Ganly I., Shah J.P., Ghossein R., Patel S.G. Influence of Extracapsular Nodal Spread Extent on Prognosis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Head Neck; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Mofty S.K. Histopathologic risk factors in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma variants: an update with special reference to HPV-related carcinomas. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2014 doi: 10.4317/medoral.20184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pathak J., Swain N., Patel S., Poonja L.S. Histopathological variants of oral squamous cell carcinoma-institutional case reports. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2014 doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.131945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.