Abstract

Objective: Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurological disease that could aggressively affect patients’ quality of life in most instances. This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of an existential-spiritual psychotherapy with a cognitive-behavioral therapy on quality of life and meaning in life in women with multiple sclerosis.

Method : A convenience sample of 43 women with multiple sclerosis participated in this quasi-experimental study. They were randomly assigned into 3 groups: an existential-spiritual intervention, a cognitive-behavioral intervention, and the control group. Participants were assessed for outcome measures (quality of life and meaning in life) at 3 points in time: pretest, posttest, and 5-months follow-up. The Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQOL-54) and the Meaning in Life Questionnaires (MLQ) were used as outcome measures. To compare outcomes among the study groups, repeated measures analysis of variance was performed.

Results: The results showed that while no difference was observed for the control group, scores for meaning in life improved significantly for existential-spiritual intervention and cognitive-behavioral therapy (p = 0.027, p = 0.039). Also, both mental (p < 0.001, p = 0.014) and physical (p = 0.001, p = 0.013) health dimensions of quality of life increased significantly in the 2 intervention groups. However, the results indicated that women in the existential-spiritual intervention group showed greater improvement in some aspects of meaning in life (search for meaning) and quality of life (role physical and role emotional, pain and energy) compared to women in the cognitive-behavioral intervention group. However, the latter group showed better improvements on 2 subscales (physical function and health distress).

Conclusion: Both existential-spiritual and cognitive-behavioral interventions can improve quality of life and meaning in life among women with multiple sclerosis. However, the findings suggest that although both interventions were effective, the existential-spiritual intervention resulted in more positive improvements in some aspects of meaning in life and quality of life.

Key Words: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, Existential-Spiritual Intervention, Meaning in Life, Multiple Sclerosis, Quality of Life

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most inflammatory-demyelinating disabling disease of the central nervous system (CNS) (1-2) that generally occurs at age between 20 and 50 years (3).

Over 2 million people have multiple sclerosis worldwide (4).

In Iran, the prevalence of MS has been estimated 100 in 100 000, which is considered to be one of the high-risk countries in Middle East (5). The ratio of women with MS is more than 3 times that of men (6).

Although MS has scarcely affected life expectancy, it can have several physical, psychological, and socioeconomic effects on individuals and societies (7-11). Also, MS has a destructive effect on patients’ quality of life (12).

While there is no definite treatment for MS, the existing therapeutic strategies are aimed at reducing the risk of relapses and possibly severe disability (13). However, a number of nontherapeutic strategies aim to improve quality of life. One such strategy is the use of logotherapy that roots from existential philosophical concepts (14) and was introduced by Frankl (1984). According to Frankl, every person has a unique task waiting to be fulfilled in life and it is that person's responsibility to actualize its meaning. Frankl also believes that one can transcend suffering if one has a reason to live. For Frankl (1984), ‘he who has a why to live for, can bear anyhow’ (p. 97) (15-16). Such evidence suggests that logotherapy can improve the meaning of life and may be effective in relieving the death anxiety caused by recurrent cancer (17). Also, it has been reported that logotherapy can reduce depression and demoralization in patients with breast and gynecological cancers (18).

Moreover, a number of investigators suggest that spiritual well-being is associated with a better mental health (19), overall health (20), and quality of life (21). In contrast, lack of spiritual well-being may result in depression, stress, anxiety, and lack of meaning and purpose in life (22). Spiritual well-being is defined as the benefits of the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, self, others, nature, and to the significant or sacred (23).

There is evidence that spiritual well-being exerts a substantial influence on psychosocial adaptation to MS (24). Thus, we assumed that augmenting existential–phenomenological psychology with spiritual themes may provide therapists a holistic and comprehensive approach.

Cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) is a structured and combined psychological intervention that is used to identify the effect of patients’ experiences based on their belief system. CBT helps to reconstruct thoughts and change responses through new skills and behaviors. It has been increasingly used among patients with chronic diseases, including those with MS, to manage symptoms (25, 26) or improve psychosocial outcomes (27). CBT is specially applied to address MS-related complications; eg, major depressive disorder, or high levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms (28). Also, studies have shown that CBT may improve psychosocial adjustment (29) and quality of life (30).

Therefore, this study aimed to assess and compare the effect of existential-spiritual psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral interventions on quality of life and meaning in life among women with MS. The selection of MS patients for this study was due to the fact that MS generally is an unexpected and sometimes debilitating disease; therefore, patients may be challenged by their thoughts on meaning in life and some essential beliefs and existential anxieties (31).

Materials and Methods

Design

This quasi-experimental study, with 1 control and 2 intervention groups, was conducted on a sample of women with MS in Tehran, Iran. Patients in interventions groups received 8 weekly sessions, while the control group received none. All participants were assessed at 3 points in time (pretest, posttest immediately after completion of intervention, and at 5 months follow-up).

Participants

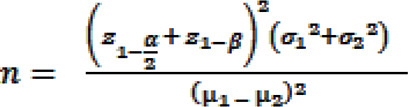

A convenient sample of patients with multiple sclerosis who were members of Iranian MS Society or those who referred to an MS center of a teaching hospital was approached and randomly assigned into the study groups. According to results of a previous study, (32) we used the following formula to estimate the sample size:

|

α = 0.05, β = 0.2, µ1 = 55.7 (mean score for quality of life, immediately after intervention), σ1 = 15.3, µ2 = 39.8 (mean score for quality of life, control group), σ2 = 17.4.

Inclusion criteria were as follow: definitive MS diagnosis by neurologist; lack of major physical or mental comorbidity; literacy; age 18 years and older; physical ability for participating in sessions; at least 6 months from diagnosis of MS; and no simultaneous psychological interventions. Exclusion criteria were as follow: acute attack; 3 times absent or more; and unwillingness to continue participation. We used random assignment for dividing patients into 3 groups: existential-spiritual intervention (n =16) (group1), cognitive-behavioral intervention (n = 16) (group 2), and control (n =16) (group 3).

Intervention

1. The existential-spiritual intervention was a comprehensive psychotherapy based on the Holy Quran, spiritual themes, and Frankele’s logotherapy (Table 1) (33). The intervention included 8 sessions on life skills improvement, coping self-awareness, meaningfulness, freedom, believing in God's blessing, eternal being, and faithfulness to moral values.

Table1.

The Content of the Existential-Spiritual Intervention and the Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Protocol*

| Session | Title | Objectives | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Existential-Spiritual Intervention |

|||

| 1 | Motivation for changing and life skills training |

Gain the trust of the group, familiarity with existential- spiritual psychotherapy life skills improvement (1st part) |

Pretest, introducing the course, and a brief discussion on barriers to change, Identification of characteristics, abilities, and goals, description of importance of life skills such as self-awareness, discussion about causes and side effects of MS providing homework |

| 2 | Being purposeful and Coping strategies |

Goal setting, identify cognitive distortions, life skills augmentation (part 2) |

Misconceptions about MS, prioritizing the goals, discussion about active coping strategies, stress management, anger control and problem solving, providing homework |

| 3 | Responsibility in life and freedom challenge, fear of death |

Death awareness, decreasing the death anxiety |

Discussion about relationships' problems, spiritual- religious coping, believe in God's blessing, believe eternal being providing homework |

| 4 | Search for meaning | Self-transcendence, self- detachment, planning for goals |

Short-term, intermediate, and long-term goals, acquiring moral values, providing homework |

| 5 | Values in cultural perspective | Explanation of creative values, empirical values and attitude values |

Setting new goals regarding to the values, for example, working, love and art, pain and suffering, providing homework |

| 6 | Authentic life style and relationships |

Improvement the communications alignment with goals |

Exploration of four relationships: being with me, god, others, and nature, providing homework |

| 7 | Revise the define of suffering | New perspective to problems | Review the sufferings and discussing any losses and gains, providing homework |

| 8 | Review | Maintenance of acquired skills | Discussion about any changes that participants see in themselves as a result of sessions. posttest |

| Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy | |||

| 1 | Cognitive and behavior | Presenting the essentials of cognitive-behavioral model |

pre-test, introducing the members of the group and, the patients' expectations from treatment, identifying current problems, receiving feedback, Discussion about causes and side effects of MS and providing homework |

| 2 | Updating and reviewing the mood |

Preparing a periodic summary | Forming a relationship with the past session, homework review, discussion of items on the agenda, getting feedback, and providing related tasks |

| 3 | Automatic thoughts | To identify automatic thoughts, | explaining the patients about the automatic thoughts and evaluating the automatic thoughts during the session relative to the MS illness, teaching the relaxation, and providing a homework |

| 4 | Identifying the emotions | Differentiating between automatic thoughts and excitement |

Discussion about primary emotions, time management and revising activities by using the activity table |

| 5 | Cognitive errors | Identifying the common cognitive errors about MS |

Assessment of automatic thoughts and training the answers to automatic thoughts and providing assignments |

| 6 | Intermediate beliefs | Identification and correction of intermediate beliefs |

Using the Socratic questioning technique, assessing the gains and difficulties of a belief and the behavioral test, cognitive conceptualization and proving the assignment |

| 7 | Fundamental beliefs | Identifying fundamental beliefs and reviewing their functions |

correcting fundamental beliefs using the fundamental belief worksheet and the technique of reviewing the supportive and contrasting evidence, providing the assignment |

| 8 | An overview of sessions | Complete the treatment, and relapse prevention |

Problem-solving training, conclusion of treatment, post-test |

Adapted from (34)

2. The cognitive-behavioral group therapy was based on the White therapeutic guideline for 8 weekly sessions (Table 1) (25). The sessions consisted of reviewing current problems, setting the goals, debating about common cognitive distortions, relationship between thoughts, emotions and behaviors, problem-solving, supportive and opposite evidences and relaxation techniques (34).

Measures

The following questionnaires were used for data collection:

Demographic and clinical information: A self-designed questionnaire was used to collect demographic characteristics (age, marital status, education, and occupation) and clinical information (duration of MS and hospitalization).

Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life (MSQOL-54): The MSQOL-54 was used to measure quality of life. It has two main components: mental health and physical health components. The MSQOL-54 was developed by Vickery et al in 1995. The scores on each component or subscale can range from 0 to 100, where the higher scores indicate better conditions (35). The psychometric properties of the Persian version of MSQOL-54 are well documented (36).

Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ): This 10-item self-report scale measures two dimensions: presence of meaning and search for meaning. The MLQ was developed by Steger et al in 2006. Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from absolutely true to absolutely untrue (37, 38). The Persian version of MLQ proved to be valid (38).

Analysis

In this study, analysis of variances and chi-square were used to compare the baseline differences among the 3 groups (two interventions and one control groups). Also, one-way analysis of variance was used to contrast between dependent variables between the 2 intervention groups at posttest and follow-up assessments. Changes from baseline to posttest and follow-up were analyzed through repeated measures among the 3 groups.

Results

Patients’ Characteristics

A total of 43 patients were entered into the study. There were no significant differences among groups with regards to demographic characteristics (age, education, occupation, and marital status), and clinical status (duration of MS and hospitalization) at baseline. Also, no differences were seen between quality of life and meaning in life scores among the 3 groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Baseline (Pretest) Quality of Life (MSQOL-54) and Meaning in Life (MLQ) Scores among the Study Groups

| Group1 | Group2 | Group3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P | |

| MSQOL-54 | ||||

| Physical function | 73.43 (22.4) | 59.61 (17.6) | 64.64 (23.9) | 0.230 |

| Role physical | 50.00 (40.8) | 34.61 (33.1) | 51.78 (42.1) | 0.462 |

| Role emotional | 47.91(43.8) | 46.15 (42.0) | 52.38 (46.6) | 0.930 |

| Pain | 68.64 (22.7) | 58.33 (22.9) | 64.64 (19.7) | 0.456 |

| Emotional well-being | 56.00 (21.3) | 61.00 (18.6) | 51.42 (17.2) | 0.459 |

| Energy | 47.00 (19.6) | 49.53 (16.7) | 45.14 (11.1) | 0.785 |

| Health perception | 66.87 (16.2) | 57.30 (20.3) | 55.35 (18.3) | 0.190 |

| Social functioning | 40.62 (17.7) | 32.69 (18.1) | 35.11 (17.0) | 0.464 |

| Cognitive functioning | 65.62 (26.5) | 56.15 (27.3) | 60.00 (29.0) | 0.651 |

| Health distress | 80.62 (20.0) | 68.07 (23.5) | 66.78 (22.1) | 0.171 |

| Sexual functioning | 68.75 (23.8) | 63.88 (32.2) | 73.15 (26.9) | 0.776 |

| Overall QoL | 69.47 (17.1) | 64.22 (21.6) | 58.19 (23.1) | 0.363 |

| Mental health composite | 59.64 (21.6) | 56.38 (18.6) | 55.15 (17.6) | 0.833 |

| Physical health composite | 60.91 (14.1) | 51.34 (12.4) | 54.46 (13.7) | 0.159 |

| MLQ | ||||

| Presence of meaning | 27.06 )7.1) | 24.00 (7.0) | 25.07 (7.4) | 0.513 |

| Search for meaning | 30.00 (4.5) | 26.30 (6.8) | 28.28 (6.2) | 0.253 |

| Total meaning in life score | 57.06 (11.2) | 50.30 (9.5) | 53.35 (12.6) | 0.281 |

Derived from one-way analysis of variance

Group 1: existential-spiritual intervention

Group 2: cognitive-behavioral therapy

Group 3: control

Quality of life

Role physical (p = 0.006), role emotional (p = 0.036), pain (p < 0.001), emotional well-being (p = 0.007), energy (p = 0.006), health perception (p = 0.006), overall quality of life (p = 0.003), mental health component (p < 0.001) and physical health component (p = 0.001) improved significantly after existential-spiritual intervention.

Physical functioning (p = 0.007), emotional well-being (p = 0.023), health perception (p = 0.011), health distress (p = 0.036), overall quality of life (p = 0.01), mental health component (p = 0.014) and physical health component (p = 0.013) improved significantly after CBT (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Results Obtained from Repeated Measures Analysis for MSQOL-54 Scores for the Study Groups

| Pretest | Posttest | Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | |

| Group1 (n=16) | ||||

| Physical functioning | 73.43 (22.4) | 72.81 (23.1) | 73.12 (23.2) | 0.876 |

| Role physical | 50.00 (40.8) | 62.50 (35.3) | 68.75 (35.9) | 0.006 |

| Role emotional | 47.91 (43.8) | 66.66 (40.3) | 68.75 (41.2) | 0.036 |

| Pain | 68.64 (22.7) | 81.77 (16.8) | 82.81 (16.4) | <0.001 |

| Emotional well-being | 56.00 (21.3) | 71.75 (11.5) | 70.75 (13.2) | 0.007 |

| Energy | 47.00 (19.6) | 63.25 (13.5) | 61.25 (14.5) | 0.006 |

| Health Perception | 66.87 (16.2) | 76.56 (15.8) | 76.87 (14.9) | 0.006 |

| Social functioning | 40.62 (17.7) | 34.37 (13.5) | 35.93 (12.8) | 0.236 |

| Cognitive functioning | 65.62 (26.5) | 70.93 (18.8) | 72.18 (19.0) | 0.186 |

| Health distress | 80.62 (20.0) | 88.43 (12.6) | 89.06 (12.9) | 0.062 |

| Sexual functioning | 68.75 (23.8) | 78.48 (20.2) | 79.55 (16.3) | 0.54 |

| Overall quality of life | 69.47 (17.1) | 80.67 (14.7) | 81.87 (14.7) | 0.003 |

| Physical health composite | 60.91 (14.1) | 68.04 (11.3) | 68.69 (10.6) | 0.001 |

| Mental health composite | 59.64 (21.6) | 72.25 (16.0) | 83.18 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Group2 (n=12) | ||||

| Physical functioning | 59.61 (17.6) | 74.23 (15.9) | 73.75 (16.5) | 0.007 |

| Role physical | 34.61 (33.1) | 53.84 (41.8) | 52.08 (43.2) | 0.193 |

| Role emotional | 46.15 (42.0) | 64.10 (39.5) | 61.11 (39.7) | 0.189 |

| Pain | 58.33 (22.9) | 68.07 (21.9) | 68.47 (22.8) | 0.191 |

| Emotional well-being | 61.00 (18.6) | 70.46 (17.7) | 70.33 (18.5) | 0.023 |

| Energy | 49.53 (16.7) | 58.76 (19.3) | 58.33 (20.1) | 0.150 |

| Health perception | 57.30 (20.3) | 72.69 (16.4) | 71.66 (16.5) | 0.011 |

| Social functioning | 32.69 (18.1) | 29.48 (15.4) | 31.25 (14.7) | 0.470 |

| Cognitive functioning | 56.15 (27.3) | 70.76 (26.5) | 69.16 (27.0) | 0.079 |

| Health distress | 68.07 (23.5) | 82.30 (15.4) | 81.25 (15.6) | 0.036 |

| Sexual functioning | 63.88 (32.2) | 84.16 (19.8) | 75.92 (33.7) | 0.240 |

| Overall quality of life | 64.22 (21.6) | 76.78 (13.6) | 77.90 (12.3) | 0.010 |

| Physical health composite | 51.34 (12.4) | 63.75 (13.7) | 62.74 (14.0) | 0.013 |

| Mental health composite | 56.38 (18.6) | 71.77 (17.6) | 77.85 (20.4) | 0.014 |

| Group3 (n=12) | ||||

| Physical functioning | 64.64 (23.9) | 65.00 (24.9) | 66.25 (18.2) | 0.998 |

| Role physical | 51.78 (42.1) | 55.76 (41.0) | 56.25 (24.1) | 0.754 |

| Role emotional | 52.38 (46.6) | 53.84 (48.1) | 55.55 (49.9) | 0.674 |

| Pain | 64.64 (19.7) | 65.25 (20.3) | 66.80 (20.4) | 0.339 |

| Emotional well-being | 51.42 (17.2) | 52.61 (17.3) | 52.66 (15.8) | 0.842 |

| Energy | 45.14 (11.1) | 46.46 (10.3) | 47.00 (8.3) | 0.870 |

| Health Perception | 55.35 (18.3) | 57.69 (16.7) | 58.33 (16.6) | 1.000 |

| Social functioning | 35.11 (17.0) | 35.89 (15.3) | 38.88 (11.4) | 0.339 |

| Cognitive functioning | 60.00 (29.0) | 59.61 (30.1) | 66.66 (25.4) | 0.140 |

| Health distress | 66.78 (22.1) | 69.23 (21.0) | 71.25 (14.3) | 0.709 |

| Sexual functioning | 73.15 (26.9) | 69.79 (21.3) | 75.00 (24.0) | 0.356 |

| Overall quality of life | 58.19 (23.1) | 60.15 (24.2) | 66.24 (26.5) | 0.223 |

| Physical health composite | 57.24 (12.5) | 56.69 (12.7) | 56.92 (8.4) | 0.841 |

| Mental health composite | 55.15 (17.6) | 53.48 (20.1) | 59.83 (17.1) | 0.490 |

Group 1: Existential-spiritual intervention

Group 2: Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Group 3: Control

No significant impact of existential-spiritual intervention was found in physical function, cognitive function, social and sexual function, and health distress. Also, cognitive-behavioral therapy did not have a significant impact on role physical and role emotional, cognition, social and sexual function, energy, and pain.

Meaning in Life

After existential-spiritual intervention, scores of meaning in life (p = 0.027), presence of meaning (p = 0.030), and search for meaning (p = 0.045) increased significantly. Among CBT group therapy, meaning in life (p = 0.039) and presence of meaning (p = 0.025) improved significantly. No significant changes were observed in the control group at 3 assessments (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Results Obtained from Repeated Measures Analysis for Meaning in Life Scores for the Study

| Pretest | Posttest | Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P | |

| Group 1 (n=16) | ||||

| Presence of meaning | 27.06 (7.12) | 29.93 (4.55) | 31.12 (2.98) | 0.030 |

| Search for meaning | 30.00 (4.51) | 31.25 (4.18) | 32.31 (2.15) | 0.045 |

| Meaning in life | 57.06 (11.23) | 60.75 (7.18) | 63.43 (4.51) | 0.027 |

| Group2 (n=12) | ||||

| Presence of meaning | 24.00 (7.05) | 26.53 (7.04) | 28.41 (6.70) | 0.025 |

| Search for meaning | 26.30 (6.82) | 27.15 (7.17) | 29.16 (5.57) | 0.299 |

| Meaning in life | 50.30 (9.56) | 53.84 (12.00) | 57.58 (12.06) | 0.039 |

| Group3 (n=12) | ||||

| Presence of meaning | 25.07 (7.48) | 26.76 (7.072) | 26.83 (6.32) | 0.297 |

| Search for meaning | 28.28 (6.26) | 29.23 (4.83) | 28.25 (5.81) | 0.365 |

| Meaning in life | 53.35 (12.60) | 56.00 (11.04) | 55.08 (11.34) | 0.705 |

Group 1: Existential-spiritual intervention

Group 2: Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Group 3: Control

Discussion

The study results indicated that an existential-spiritual intervention could improve some aspects of mental and physical health in women with MS.

Similar observations have been reported in prior studies that examined the logotherapy effect on quality of life among patients with MS (39, 40). Moreover, a number of studies showed similar results for other diseases. For instance, among community-dwelling adults with cardiovascular diseases who took part in a 1-month individualized spirituality-based intervention and demonstrated a relatively fair increase in overall quality of life (41). Similarly, logotherapy was effective in improvement of quality of life of adolescents with terminal cancer (14).

In this study, the findings showed that cognitive-behavioral therapy could improve some aspects of quality of life in this population. Likewise, in parallel with this study, some investigators proved that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) improves mental health and quality of life in MS patients (26, 42 and 43). The effectiveness of CBT could be related to its several properties, including modification of thoughts and identification of emotions and cognition errors, which result decreasing stress and improving mental health. However, these results require further evaluation considering that other factors could also affect quality of life in patients with MS.

Moreover, we observed that existential-spiritual therapy could improve life’s meaning and its components. This result was expected because the main goal of this intervention was motivating patients to search for the meaning of life according to their values. Also, ‘meaning’ is an element of spirituality that appears to be a more common concept that can exist in religious or nonreligious individuals (44); thus, improvement of meaning, will result in better spirituality. Similarly, spiritual well-being is related to less perceived illness and psychological distress (24), as well as better coping and psychosocial adjustment (20, 24). Also, Nsamenang emphases a multidimensional attitude, including promotion of spiritual well-being for addressing physical or psychological status of MS patients (45).

Puchalski and Romer (2000) defined spirituality as “a concept that allows a person to experience transcendent meaning in life.” (46). Our finding is consistent with those of prior researches. Kang et al showed that logotherapy could decrease suffering and increase the meaning in life among adolescents with lethal cancer (47) and can be applied for adolescents to prevent existential pain (14). Also, according to Breitbart, a comprehensive intervention that includes spiritual features to existential distress, demoralization, and loss of meaning should be developed and implemented for patients with advanced cancer (44).

The study results showed that CBT can improve meaning in life, which is consist with a study showed that cognitive behavioral therapy increases spiritual well-being significantly among the elderly mourners (48). This could result from the CBT effects on reconstructing the thoughts, changing behavior, and new objectives for life. The findings indicated that some aspects of quality of life, such as physical functioning social functioning, and sexual function, did not change among women in the 2 intervention groups; this may have several reasons: it can be due to small sample size and the fact that people with different cultural backgrounds may respond differently to issues such as social functioning or sexual functioning.

Limitation

This study has some strengths and limitations. To some extent, the quasi-experimental design of the study with a comparison group and the use of well-known standard measures to assess the quality of life and meaning in life could be regarded as strengths. However, the study had 2 main limitations. First, participants were recruited through convenience sampling from patients who were members of Iranian MS Society or those who referred to an MS Center of a teaching hospital. Therefore, our findings may not be generalized to all women with MS. Secondly, we did not measure other psychological variables that may mediate associations with quality of life and meaning in life. Thus, further studies are needed to explore factors that affect quality of life among women with MS.

Conclusion

Both existential-spiritual and cognitive-behavioral interventions can improve quality of life and meaning in life among women with multiple sclerosis. However, the findings suggested that although both interventions were effective, the existential-spiritual intervention resulted in more positive improvements in some aspects of meaning in life and quality of life. In general, it seems that both existential-spiritual intervention and cognitive-behavioral therapy can be helpful to improve quality of life and meaning in life among women with MS. The interventions also can help women to overcome their problems and adjust themselves to the disease and its consequences.

Acknowledgment

Our deep appreciations go to participants of this study and the Iranian MS Society.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Young L, Healey K, Charlton M, Schmid K, Zabad R, Wester R. A home-based comprehensive care model in patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A study pre-protocol. F1000Res. 2015;4:872. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7040.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leray E, Moreau T, Fromont A, Edan G. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis. Rev Neurol. 2016;172(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milo R, Kahana E. Multiple sclerosis: geoepidemiology, genetics and the environment. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9(5):A387–A94. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Nichols E, Bhutta ZA, Gebrehiwot TT, Hay SI, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):269–85. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30443-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eskandarieh S, Heydarpour P, Elhami SR, & Sahraian MA. Prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(5):699–704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eskandarieh S, Allahabadi NS, Sadeghi M, Sahraian MA. Increasing prevalence of familial recurrence of multiple sclerosis in Iran: a population based study of Tehran registry 1999-2015. BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12883-018-1019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adelman G, Rane SG, Villa KF. The cost burden of multiple sclerosis in the United States: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Econ. 2013;16(5):639–47. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.778268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(13):938–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalah MA, Ayache SS. Psychiatric event in multiple sclerosis: could it be the tip of the iceberg? Braz J Psychiatry. 2017;39(4):365–8. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2016-2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKeown LP, Porter-Armstrong AP, Baxter GD. Caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis: experiences of support. Mult Scler. 2004;10(2):219–30. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1008oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solari A. Role of health-related quality of life measures in the routine care of people with multiple sclerosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford HL, Gerry E, Johnson MH, Tennant A. Health status and quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(12):516–21. doi: 10.1080/09638280010022090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, Otero-Romero S, Amato MP, Chandraratna D, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96–120. doi: 10.1177/1352458517751049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang KA, Shim JS, Jeon DG, Koh MS. [The effects of logotherapy on meaning in life and quality of life of late adolescents with terminal cancer] J Korean Acad Nurs. 2009;39(6):759–68. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2009.39.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frankl VE. Man's Search for Meaning. New York: Touchstone. Simon & Schuster; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeMay K, Wilson KG. Treatment of existential distress in life threatening illness: a review of manualized interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(3):472–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang PL, Chen WL, Cheng SF. [Using logotherapy to relieve death anxiety in a patient with recurrent cancer: a nursing experience]. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2013;60(4):105–10. doi: 10.6224/JN.60.3.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun FK, Hung CM, Yao Y, Fu CF, Tsai PJ, Chiang CY. The Effects of Logotherapy on Distress, Depression, and Demoralization in Breast Cancer and Gynecological Cancer Patients: A Preliminary Study. Cancer Nurs. 2019 doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahnama P, Javidan AN, Saberi H, Montazeri A, Tavakkoli S, Pakpour AH, et al. Does religious coping and spirituality have a moderating role on depression and anxiety in patients with spinal cord injury? A study from Iran. Spinal Cord. 2015;53(12):870–4. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irvine H, Davidson C, Hoy K, Lowe-Strong A. Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis: exploration of identity redefinition. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(8):599–606. doi: 10.1080/09638280802243286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajiaghababaei M, Saberi H, Rahnama P, Montazeri A. Spiritual well-being and quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury: A study from Iran. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41(6):653–8. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2018.1466479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mauk KL, Schmidt NA. Spiritual care in nursing practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, Otis-Green S, Baird P, Bull J, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNulty K, Livneh H, Wilson LM. Perceived uncertainty, spiritual well-being, and psychosocial adaptation in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2004;49(2):91–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.White CA. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic medical problems: A guide to assessment and treatment in practice. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dennison L, Moss-Morris R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy: what benefits can it offer people with multiple sclerosis? Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(9):1383–90. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moorey S, Cort E, Kapari M, Monroe B, Hansford P, Mannix K, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy for common mental disorders in patients with advanced cancer. Psychol Med. 2009;39(5):713–23. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. A review of psychological correlates of adjustment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(2):141–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, Galvin K, Baker R. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004431.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malcomson KS, Dunwoody L, Lowe-Strong AS. Psychosocial interventions in people with multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol. 2007;254(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0349-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pakniya N, Bahmani B, Dadkhah A, Azimian M, Naghiyaee M, MASUDI SR. Effectiveness of cognitive existential approach on decreasing demoralization in women with multiple sclerosis. IRANIAN REHABILITATION JOURNAL. 2015;13(4):28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghazavi Z, Rahimi E, Yazdani M, Afshar H. Effect of cognitive behavioral stress management program on psychosomatic patients' quality of life. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2016;21(5):510–5. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.193415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frankl VE. The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy. Vintage. 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alavi MS, Jabal Ameli S. The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Emotional Control of MS Patients in the City of Isfahan. Jorjani Biomed J. 2018;6(1):44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Harooni R, Myers LW, Ellison GW. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):187–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02260859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghaem H, Borhani Haghighi A, Jafari P, Nikseresht AR. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the multiple sclerosis quality of life questionnaire. Neurol India. 2007;55(4):369–75. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.33316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53(1):80–93. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mesrabadi J, Jafariyan S, Ostovar N. Discriminative and construct validity of meaning in life questionnaire for Iranian students. J Behavi Scie. 2013;7(1):83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haresabadi M, Karimi Monaghi H, Froghipor M, Mazlom S. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis referring to Ghaem hospital, Mashhad in 2009. JNKUMS. 2011;2(4):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mardanivalendani M, Ghafari Z. THE EFFECTIVENESS OF LOGOTHERAPY ON QUALITY OF LIFE AMONG MS PATIENTS IN SHAHREKORD. JOURNAL OF ILAM UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES. 2015;23(5):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delaney C, Barrere C, Helming M. The influence of a spirituality-based intervention on quality of life, depression, and anxiety in community-dwelling adults with cardiovascular disease: a pilot study. J Holist Nurs. 2011;29(1):21–32. doi: 10.1177/0898010110378356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moss-Morris R, Dennison L, Landau S, Yardley L, Silber E, Chalder T. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for adjusting to multiple sclerosis (the saMS trial): does CBT work and for whom does it work? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(2):251–62. doi: 10.1037/a0029132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Kessel K, Moss-Morris R, Willoughby E, Chalder T, Johnson MH, Robinson E. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy for multiple sclerosis fatigue. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(2):205–13. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181643065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breitbart W. Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality- and meaning-centered group psychotherapy interventions in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10(4):272–80. doi: 10.1007/s005200100289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nsamenang SA, Hirsch JK, Topciu R, Goodman AD, Duberstein PR. Erratum to: The interrelations between spiritual well-being, pain interference and depressive symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Behav Med. 2016;39(2):364. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9724-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puchalski C, Romer AL. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(1):129–37. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang K, Im J, Kim H, Kim S, Song M, Sim S. The effect of logotherapy on the suffering, finding meaning, and spiritual well-being of adolescents with terminal cancer. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;15(2):136–44. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solaimani Khashab A, Ghamari Kivi H, Fathi D. Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Spiritual Well-Being and Emotional Intelligence of the Elderly Mourners. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12(2):93–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]