Abstract

Background

In the current COVID-19 pandemic, aggressive Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) measures have been adopted to prevent health care-associated transmission of COVID-19. We evaluated the impact of a multimodal IPC strategy originally designed for the containment of COVID-19 on the rates of other hospital-acquired-infections (HAIs).

Methodology

From February-August 2020, a multimodal IPC strategy was implemented across a large health care campus in Singapore, comprising improved segregation of patients with respiratory symptoms, universal masking and heightened adherence to Standard Precautions. The following rates of HAI were compared pre- and postpandemic: health care-associated respiratory-viral-infection (HA-RVI), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and CP-CRE acquisition rates, health care-facility-associated C difficile infections and device-associated HAIs.

Results

Enhanced IPC measures introduced to contain COVID-19 had the unintended positive consequence of containing HA-RVI. The cumulative incidence of HA-RVI decreased from 9.69 cases per 10,000 patient-days to 0.83 cases per 10,000 patient-days (incidence-rate-ratio = 0.08; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.05-0.13, P< .05). Hospital-wide MRSA acquisition rates declined significantly during the pandemic (incidence-rate-ratio = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.46-0.64, P< .05), together with central-line-associated-bloodstream infection rates (incidence-rate-ratio = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.07-0.57, P< .05); likely due to increased compliance with Standard Precautions. Despite the disruption caused by the pandemic, there was no increase in CP-CRE acquisition, and rates of other HAIs remained stable.

Conclusions

Multimodal IPC strategies can be implemented at scale to successfully mitigate health care-associated transmission of RVIs. Good adherence to personal-protective-equipment and hand hygiene kept other HAI rates stable even during an ongoing pandemic where respiratory infections were prioritized for interventions.

Key Words: SARS-CoV-2, Healthcare associated infections, Surveillance, infection control, MRSA

INTRODUCTION

In the current COVID-19 pandemic, aggressive Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) measures have been adopted to prevent health care-associated transmission of COVID-19.1 The unprecedented threat of a novel pathogen provided the impetus for hospital-wide deployment of various IPC strategies, such as universal masking, visitor restrictions, and deployment of droplet and contact precautions for patients with respiratory symptoms.2, 3, 4 Prior to the pandemic, such strategies were only deployed in high-risk units, given concerns with cost-effectiveness and sustainability.5 , 6 The current pandemic thus provides an opportunity to assess the effect of multimodal IPC bundles when deployed at scale. However, the prioritization of COVID-19 may have also forced compromises in other areas, potentially raising rates of other hospital-acquired infections (HAIs).7 , 8 Increases in other HAIs, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) acquisition rates, were reported during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003.9 Similar circumstances during the COVID-19 pandemic are anticipated to result in higher rates of central-line-associated blood-stream infections (CLABSI) and other device-associated infections.7 The challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic may also limit the ability of overstretched health care systems to sustain surveillance for HAIs.

In Singapore, a Southeast Asian city-state with close travel links to mainland China, by end-February 2020, the majority of COVID-19 cases were attributed to local transmission.10 Previous experiences with containing SARS in 2003 meant that local hospitals implemented multimodal IPC bundles for COVID-19 early on; including universal masking policies, improved segregation of patients with respiratory symptoms, visitor screening, and adequate personal-protective-equipment (PPE).11, 12, 13 To-date, despite significant community transmission, rates of health care-associated transmission of COVID-19 are extremely low.11, 12, 13 Hospitals were not overwhelmed by the surge in cases and adequate PPE was made available for both frontline and ancillary health care workers (HCWs).14 On the largest health care campus in Singapore, surveillance and containment efforts for other HAIs were sustained continuously throughout the pandemic. As such, it was feasible to evaluate the impact of a multimodal IPC strategy originally designed for the containment of COVID-19 on the rates of other HAIs throughout the pandemic period.

METHODOLOGY

Institutional setting and study period

The Outram campus of the Singapore Health Services group hosts the Singapore General Hospital (SGH), the largest hospital in Singapore with 1,785 beds, and other specialist centers. SGH has 81,495 inpatient admissions per-year. Other specialist centers on the Outram campus include the National Heart Center, Singapore (NHCS), National Cancer Center, Singapore (NCC), Singapore National Eye Center (SNEC), and the National Neuroscience Institute (NNI). The NHCS, NNI, NCC, and SNEC are the largest specialized centers in Singapore. We compared rates of HAI over a 7-month period during the COVID-19 pandemic (February 1, 2020-August 31, 2020), after the introduction of enhanced IPC measures, with rates of HAI over the preceding 2 years (January 2018-January 2020). Over the corresponding period, our institution cared for ≥1,600 cases of COVID-19, with no evidence of patient-HCW transmission.12, 13, 14 There was only one potential cluster (N = 2) of COVID-19 cases in an RSW, though health care-associated transmission could not be conclusively proven.14

Infection-prevention practices prior to COVID-19 pandemic

Prior to the pandemic, the majority of inpatients were housed in multibedded cohorted open wards. This posed challenges for IPC, given the increased number of patients and shared facilities in open-plan general wards,15 and known difficulties with maintaining adequate ventilation and indoor air quality in hot and humid tropical environments.16 While patients with respiratory symptoms and PCR-proven respiratory-viral-infection were isolated in single rooms where possible, this was not practiced consistently, given the limited number of single rooms campus-wide. A universal masking policy was practiced only in high-risk units, such as the intensive-care-units (ICUs) and wards for hematology patients. At our institution, various bundles for HAI prevention, including hand hygiene, decontamination of the environment/equipment, active surveillance cultures, contact precautions for infected and colonized patients, and device bundles (central line and ventilator bundles), have been in place since 2008.17 Active surveillance was performed for common multidrug-resistant-organisms (MDROs) by our Department of Infection Prevention and Epidemiology (IPE). Patients colonized with MDROs, such as MRSA, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CP-CRE), as well as Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) were managed in cohorted areas where Contact Precautions (disposable gowns and gloves) were utilized for patient care.

Campus-wide multimodal IPC bundle for COVID-19

The first case of COVID-19 in Singapore was diagnosed at our institution on the January 23, 2020 (epidemiological-week, E-week 4).12 From E-week 5 onward, hospital-wide measures were progressively introduced to mitigate the risk of health care-associated transmission of COVID-19. Improved segregation was introduced for patients with respiratory symptoms.18 Patients with respiratory symptoms but no epidemiological risk factors for COVID-19 were segregated in designated clinical areas (termed as respiratory surveillance wards [RSWs]). In these RSWs, distance between beds was increased to at least 1.5 m to encourage safe distancing and usage of surgical masks amongst hospitalized inpatients was made mandatory.12 , 13 From E-week 10-12, PPE used by staff in the RSWs was progressively upgraded to N95 respirators, faceshields, gowns and gloves; staff used surgical masks initially. Confirmed COVID-19 cases were housed in dedicated airborne-infection-isolation-rooms (AIIRs), either in the SGH's purpose-built 51-bedded isolation ward (IW) or in a 50-bedded IW extension containing AIIRs modified from containers that was constructed during the COVID-19 pandemic.19 In the IW and RSW, cleaning was done using 1:1000 hypochlorite-based disinfectant 3 times a day; UV-C disinfection was also utilized postdischarge in areas housing COVID-19 cases. Cleaners in these areas were required to wear PPE (N95 respirators, eye protection, and disposable gown and gloves). Beds set aside for the management of COVID-19 suspects/cases constituted almost 20% of our institution's capacity during the pandemic.12

Simultaneously, enhanced campus-wide IPC measures were introduced in the general ward setting, to mitigate the potential risk of an unsuspected case presenting outside of areas designated for COVID-19 management. From E-week 5, a universal masking policy for all HCWs in clinical areas was introduced, with usage of a surgical mask the mandatory minimum. Regular hand hygiene with alcohol handrub was also re-emphasized. For environmental cleaning, prepandemic all patient areas were cleaned with 1:1000 hypochlorite-based disinfectant, at a frequency of at least 3 times a day; during the pandemic, cleaning practices were reinforced and regular environmental cleaning audit using fluorescent markers (Glogerm) was maintained. UV-C disinfection was also utilized at our institution since 2017; during the COVID-19 pandemic, usage of UV-C disinfection for postdischarge cleaning was continued for general ward and ICU rooms with MDRO cases, in transplant rooms, and in the operating theatres after-hours, despite increased demand for UV-C disinfection in the areas designated for COVID-19 management. Throughout the pandemic, cohorting was maintained in the general ward setting for patients with MDROs. While the COVID-19 pandemic placed pressure on isolation beds, additional isolation capacity was provided through the container IW extension.19 Finally, as part of visitor management, campus-wide temperature screening for all visitors and visitor restrictions (1 visitor per patient) were introduced from E-week 8, with entry denied to visitors with a documented fever at the point of entry. Visitors were required to wear a face mask at all times. From E-week 15 to E-week 22, a no-visitor policy was enforced throughout hospital; this was in tandem with the community-wide imposition of an elevated set of safe-distancing measures to preempt the trend of increasing local transmission of COVID-19, by closing schools and all physical workplace premises.20. The no-visitor policy was lifted from June 2 onward (E-week 23); the remaining IPC measures were continued through the end of the study period.

Surveillance for other HAIs during COVID-19 pandemic

During the pandemic, routine surveillance cultures for MDROs were maintained. We compared the following rates of HAI pre-and during-COVID-19: health care-associated RVIs (HA-RVI), MRSA acquisition, CP-CRE acquisition, multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extremely drug-resistant (XDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PsA) infection, health care-facility-associated C difficile infection (HCFA-CDI), and device-associated HAI.

HA-RVI

Over the study period, all inpatients campus-wide with respiratory symptoms were tested for both COVID-19 as well as a panel of 16 common RVI via multiplex PCR. Respiratory specimens were tested for influenza A and B, human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) 1/2/3/4, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) subtypes A and B, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), human coronavirus (HCoV) (229E/NL63/OC43), rhinovirus A/B/C, enterovirus, adenovirus and human bocavirus (HboV) 1/2/3/4. PCR-positive cases of RVI were categorized as health care-associated if the respiratory virus was identified beyond the maximum incubation period from the time of admission.4 We further stratified HA-RVI into enveloped and nonenveloped HA-RVI; enveloped RVI included RSV, influenza, parainfluenza, metapneumovirus and other coronaviruses, whereas nonenveloped RVI included rhinovirus, adenovirus, enterovirus, and bocavirus.

MRSA acquisition

As part of active surveillance, all patients had nasal and axillary swabs taken for MRSA testing to determine MRSA carriage status on admission; active surveillance samples were repeated at D14 and then fortnightly for long stayers. A case of MRSA carriage was defined as an instance in which MRSA was recovered from a patient regardless of the site and type of specimen (ie, a screening or clinical diagnostic specimen). MRSA-acquisition was defined as detection of MRSA carriage in a patient whose admission swabs for MRSA were initially negative. Health care-associated MRSA bacteremia was defined as onset of MRSA bacteremia ≥72 hours after hospital admission. Rates of MRSA-acquisition and rates of health care-associated MRSA bacteremia were calculated as the total number of cases divided by the total number of patient-days over the study period.

CP-CRE acquisition

As part of active surveillance, patients with identified risk factors (history of hospitalization in the past 1 year; transfer cases from other institutions), all admissions to Haematology, Oncology, and Renal wards and all ICU admissions had rectal swabs taken for CP-CRE testing to determine carriage status at the point of admission; active surveillance samples were repeated at D14. A case of CP-CRE carriage was defined as an instance in which CP-CRE was recovered from a patient regardless of the site and type of specimen (ie, a screening or clinical diagnostic specimen). CP-CRE-acquisition was defined as detection of CP-CRE carriage in a patient whose admission swabs for CP-CRE were initially negative. Rates of CP-CRE-acquisition were calculated as the total number of cases divided by the total number of patient-days over the study period.

MDR and XDR PsA infections

At our institution, MDR/XDR PsA constituted one of the most common causes of MDR-gram-negative infections, apart from CP-CRE. All clinical isolates with MDR/XDR PsA were identified; MDR PsA was defined as isolates that were not sensitive to at least one antibiotic from 3 or more different classes, while XDR PsA was defined as a subset of MDR PsA isolates that were not sensitive to at least one antibiotic from 5 different classes. At our institution, the 5 antibiotic classes included in routine testing were aminoglycosides (gentamicin and amikacin), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin), antipseudomonal cephalosporins (ceftazidime and cefepime), antipseudomonal penicillins (piperacillin/tazobactam), and carbapenems (meropenem). Rates of MDR/XDR PsA infections were calculated as the total number of cases divided by the total number of patient-days over the study period.

HCFA-CDI

Cases of HCFA-CDI were identified using the standard epidemiological classification of CDI.21 Only hospital-onset health care facility-associated (HO-HCFA) and community-onset healthcare facility-associated infections were considered as nosocomial. The algorithm employed for the microbiological diagnosis of CDI at our institution remained the same throughout (sequential qualitative detection of glutamate dehydrogenase and A and B toxins from C difficile). Discrepancies were resolved through RT-PCR testing for the C difficile toxin gene. Rates of HCFA-CDI were calculated as the total number of cases divided by the total number of patient-days over the study period.

Device-associated health care-associated infections

Data on hospital-wide CLABSIs, hospital-wide catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) occurring in patients hospitalized in ICUs were prospectively collected. Definitions of CLABSI, CAUTI, and VAP were based on CDC criteria,21 and rates were calculated for CLABSI, CAUTI, and VAP based on central-line days, catheter-days, and ventilator-days, respectively. Compliance with CLABSI, CAUTI, and VAP bundles were monitored and audited regularly by IPE staff throughout the pandemic. The components of the various bundles are described in Supplementary Figure 1.

Monitoring of compliance with enhanced campus-wide IPC measures

Rates of compliance to the World Health Organization (WHO) “Your 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene” were continuously monitored throughout the pandemic, and hand hygiene audit results were stratified by staff and hand hygiene moment. Regular environmental cleaning audit using fluorescent markers (Glogerm) was maintained in inpatient areas, procedural areas (eg, operating theaters), and in the emergency department even during the pandemic period. The average number of UV-C disinfections carried out during the pandemic was also tracked, as well as consumption of alcohol handrub and other PPE (surgical masks, N95 respirators, and disposable gloves and gowns). Hand hygiene compliance, environmental cleaning audit results and PPE consumption over a seven-month period during the COVID-19 pandemic (February 1, 2020-August 31, 2020) was compared to results over the preceding year, in the prepandemic period (January 2019-January 2020).

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of HAI rates were made using the incidence-rate-ratio (IRR) method. When comparing rates per patient-days, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around proportions were estimated. A P-value (2-tailed) of ≤.05 was considered significant.

Ethics approval

Waiver of informed consent was approved by our hospital's Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref 2020/2436).

RESULTS

Pre-pandemic, the campus-wide cumulative incidence of HA-RVI was 9.69 cases per 10,000 patient-days (989 cases; 1,020,463 patient-days) (Fig 1 a). After introduction of enhanced IPC measures, the incidence of PCR-proven HA-RVI was 0.83 cases per 10,000 patient-days (22 cases; 264,904 patient-days). The IRR of PCR-proven HA-RVI per 10,000 patient-days between the 2 periods (pre- and postpandemic) was 0.08 (95% CI = 0.05-0.13, P < .05). This decrease was seen across both enveloped HA-RVI and nonenveloped-HA-RVI, and was sustained even after the lifting of community-based measures (“lockdown”). During the pandemic, admissions for community-acquired RVIs at our institution remained stable.22 For enveloped HA-RVI, the rates fell from 6.05 cases per 10,000 patient-days (618 cases) to 0.45 cases per 10,000 patient-days (12 cases) after the introduction of enhanced IPC measures (IRR = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.04-0.13, P < .05), while for nonenveloped HA-RVI, the rates fell from 3.63 cases per 10,000 patient-days to 0.38 cases per 10,000 patient-days (IRR = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.05-0.19, P < .05) (Fig 1a).

Fig 1.

Rates of health care-associated infections prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore. (a) Number of health care-associated respiratory viral infections (HA-RVI). (b) MRSA acquisition rate (per 10,000 patient-days). (c) CP-CRE acquisition rate (per 1,000 patient days). (d) Number of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) P aeruginosa (PsA) infections.

Prepandemic, the rate of MRSA acquisition was 11.7 cases per-10,000 patient-days (1,194 cases, 1,020,463 patient-days) (Fig 1b). During the pandemic, the rate of MRSA acquisition decreased to 6.4 cases per-10,000 patient-days (169 cases, 264,904 patient-days); the difference was statistically significant (IRR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.46-0.64, P < .05). The rate of health care-associated MRSA bacteremia also decreased during the pandemic (pre-pandemic: 0.36 cases per 10,000 patient-days, 37 cases, 1,020,463 patient-days; pandemic period: 0.11 cases per 10,000 patient-days, 3 cases, 264,904 patient days; IRR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.06-0.97, P = .04). There was no significant increase in CP-CRE acquisition or MDR/XDR PsA infection during the pandemic (Fig 1c, d). During the pandemic, the rate of CP-CRE acquisition was 10.2 cases per-1000 patient-days (353 cases, 34,569 patient-days); the difference was not statistically significant compared to the prepandemic period (11.2 cases per-1,000 patient-days; 1900 cases, 169,573 patient-days; IRR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.81-1.02, P = .11). The rate of MDR PsA infection prepandemic was 4 cases per 10,000 patient-days (408 cases, 1,020,463 patient-days). During the pandemic, the rate of MDR-PsA infection was 4.34 cases per 10,000 patient-days (115 cases, 264,904 patient-days); this difference was not statistically significant (IRR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.88-1.34, P = .44). Similarly, the rate of XDR-PsA infection prepandemic was 0.26 cases per 10,000 patient-days (27 cases, 1,020,463 patient-days). During the pandemic, the rate of XDR-PsA infection was 0.30 cases per 10,000 patient-days (8 cases, 264,904 patient-days); this difference was not statistically significant (IRR = 1.14, 95% CI = 0.45-2.58, P = .74). There was no significant increase in HCFA-CDI during the pandemic (Fig 1e). During the pandemic, the rate of HCFA-CDI was 3.47 cases per 10,000 patient-days (92 cases, 264,904 patient-days); the difference was not statistically significant compared to the prepandemic period (3.65 cases per 10,000 patient-days; 373 cases, 1,020,463 patient-days; IRR = 0.95, CI = 0.75-1.20, P = .66).

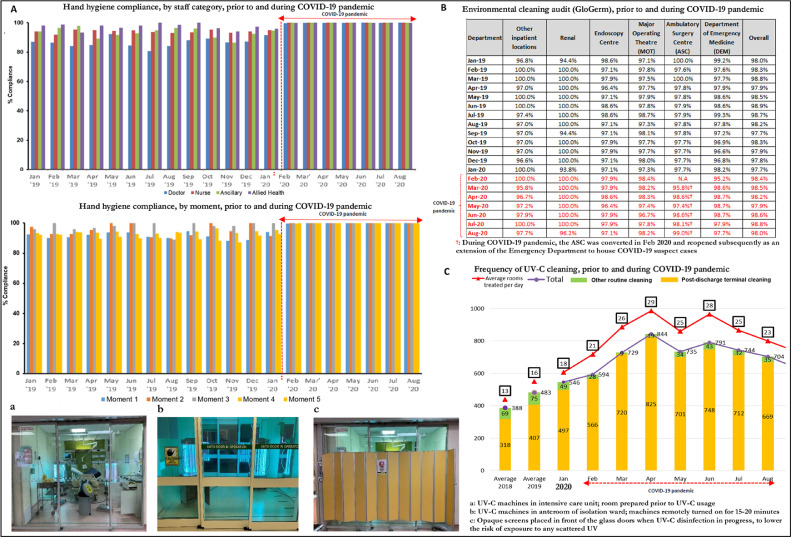

The reduction in HA-RVI, and stable rates of other HAIs, were likely attributed to increased compliance with segregation of symptomatic patients, and hospital-wide increases in adherence to Standard Precautions. Hand hygiene audit compliance with the WHO “Your 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene” prior to COVID-19 was 85%, compared with 100% during the COVID-19 pandemic, across all categories of HCWs and all hand hygiene moments surveyed (Fig 2 a). Standards of environmental cleaning prepandemic on regular audit using fluorescent markers (Glogerm) were high, and these standards were maintained throughout the pandemic, both in general ward areas and areas designated for the management of COVID-19 suspects (Fig 2b). UV-C disinfection was employed more frequently, rising from an average of 16 rooms treated per day prepandemic to 25 rooms treated per-day during the pandemic (Fig 2c). Similarly, the rate of handrub consumption rose from 57.5 L/day, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (2,2697 L consumed over 395 days), to 78.7 L/day during the COVID-19 pandemic (1,6691 L over 212 days) (Fig 2d). Consumption of PPE, including N95 respirators, surgical masks, and disposable gowns rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic; in particular, consumption of surgical masks tripled and consumption of N95 respirators increased by almost fivefold. (Fig 2d)

Fig 2.

Hand hygiene compliance, environmental cleaning audit and personal-protective-equipment consumption, prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore. (a) Hand hygiene compliance, prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore. (b) Environment cleaning audit, prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore. (c) Frequency of UV-C cleaning, prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore. (d) Consumption of alcohol handrub and personal protective equipment, prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore.

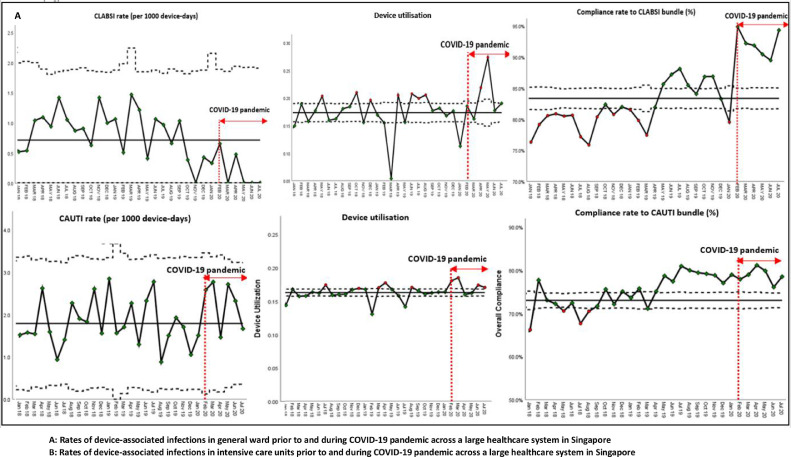

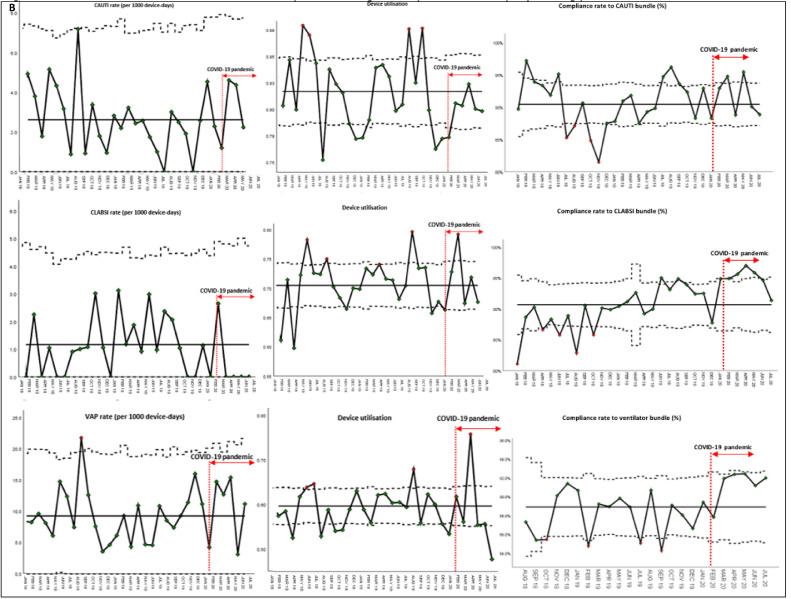

With regards to device-associated infections, despite the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital-wide CLABSI rates decreased substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic, likely because of increased adherence to the CLABSI bundle (Fig 3 a). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of CLABSI was 0.83 incidents per-1,000 device-days (95 incidents, 113,466 device-days). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the CLABSI rate decreased to 0.20 incidents per-1,000 device-days (5 incidents, 25154 device-days); the difference was statistically significant (IRR = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.07-0.57, P < .05). Hospital-wide CAUTI rates remained stable at 1.8 incidents per-1,000 device-days; increased compliance to the CAUTI bundle was also noted during the pandemic period (Fig 3a). Increased compliance to CLABSI and CAUTI bundles was likely due to increased hand hygiene compliance during the pandemic. Across ICUs, rates of CLABSI, CAUTI, and VAP remained stable during the pandemic period (Fig 3b). While there was an ICU-wide trend toward decreased CLABSI rates (0.42 incidents per-1,000 device-days during the COVID-19 pandemic, versus 1.1 incidents per-1,000 device-days prepandemic), this was not statistically significant (IRR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.04-1.54, P = .18).

Fig 3.

Rates of device-associated infections in general wards and intensive care units, prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore. (a) Rates of device-associated infections in general ward prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore. (b) Rates of device-associated infections in intensive care units prior to and during COVID-19 pandemic across a large health care system in Singapore.

DISCUSSION

The key finding of this study was that enhanced IPC measures during the COVID-19 pandemic had the unintended but positive consequences of reducing HA-RVI without compromising other HAIs. At our center during COVID-19, MRSA acquisition rates actually decreased; contrasted against the experience at other centers during the SARS outbreak in 2003, when significant and substantial rises in MRSA acquisition were noted in conjunction with IPC measures introduced for SARS.9 While the concomitant rise in MRSA acquisition during the SARS outbreak was attributed to the potential for Staphylococcal superinfection in patients with viral pneumonia, as well as inappropriate reuse of PPE,9 emerging evidence suggests that MRSA is not commonly identified as a copathogen in COVID-19 pneumonia.23 However, the usage of contact as well as droplet-based precautions for high-risk COVID-19 suspects has been associated with clusters of CLABSI, likely due to sessional usage of full-sleeved gowns which hindered hand hygiene compliance.8 At our institution, given adequate supplies of PPE, sessional use of PPE was discouraged and gowns/gloves were changed in-between patients, to avoid the health care-associated transmission of organisms other than SARS-CoV-2. Adherence to PPE was also high during the pandemic at our institution; around 90% of HCWs were adherent with Droplet Precautions, and 70% adherent with Contact Precautions, during significant contact episodes with high-risk COVID-19 suspects.24 This likely explains the absence of a corresponding rise in HAIs, even amidst the disruption of a pandemic caused by a novel respiratory pathogen, and the potential for antibiotic misuse during an ongoing pandemic. Indeed, during the pandemic, utilization of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as fourth generation cephalosporins, carbapenems and vancomycin rose by almost 25% at our institution, potentially increasing the selection pressure for MDROs.25 Increased focus on hand hygiene, given the possibility of contact transmission of SARS-CoV-2, as well as decreased bed density brought about by improved patient segregation, could potentially decrease the spread of MDROs via contact transmission from infected and colonized patients. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated increased rates of nosocomial MRSA with increased patient density and enclosed bed spaces.26 However, the hospital environment can also serve as a reservoir of MDROs, with elements of the near-patient environment (eg, curtains, bedside equipment) serving as a reservoir of MRSA and hospital sinks and drains acting as reservoirs of CP-CRE and MDR-PsA.26 , 27 While emphasis on cleaning of the near-patient environment was prioritized during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the presence of viral contamination on high-touch areas in the immediate vicinity of the patient;13 the relative inaccessibility of sinks and drains may have resulted in the persistence of other MDROs and hence resulted in the differing results for MRSA and CP-CRE acquisition during the COVID-19 pandemic. While other studies have reported declines in HCFA-CDI during the COVID-19 pandemic from enhanced IPC measures,28 , 29 rates of HCFA-CDI at our institution remained static. Hand hygiene and environmental cleaning standards at our institution were already at high levels prepandemic; the marginal additional increases observed during the pandemic may not have translated into a significant impact on HCFA-CDI. Furthermore, while the rate of consumption of alcohol handrub rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, alcohol-based hand sanitizer is ineffective against C difficile spores. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, almost 1 in 10 inpatients in Singaporean hospitals had some form of HAI.30 Surveillance and prevention efforts for HAI should not be compromised during IPC efforts for COVID-19.7 , 8

Implementation of a bundle of IPC measures designed to reduce health care-associated transmission of COVID-19 also resulted in a significant decrease in HA-RVI. Common respiratory viruses remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality amongst hospitalized inpatients with respiratory diagnoses31; accounting for almost one-quarter of admissions for pneumonia.32 , 33 HA-RVI remain an underappreciated cause of morbidity and mortality in hospitalized adult inpatients, and a significant cause of severe hospital-acquired pneumonia requiring intensive care.33 The current COVID-19 pandemic highlights the importance of strengthening IPC measures against common respiratory viruses. Across our health care system, the introduction of visitor screening, improved segregation of patients with respiratory symptoms, and mandatory sick leave for symptomatic staff resulted in an unprecedented decrease in HA-RVI. While reductions in HA-RVI have been reported in other centers during the COVID-19 pandemic,34 and a significant decrease in community-acquired RVI was noted in Singapore, attributed to the introduction of community-based COVID-19 control measures,20 admissions for community-acquired RVI at our institution remained static during the initial phase of the pandemic.22 The reductions seen in HA-RVI were already attained prior to the imposition of community-wide “lockdown” measures and sustained even after reversal of “lockdown”; substantial decreases in HA-RVI were thus likely attributable primarily to the hospital-based measures introduced for COVID-19 control.

Our study has the following limitations. This study was conducted in a single health care system; hence the findings may not be fully generalizable to other settings. Additionally, implementing enhanced IPC measures at our institution required substantial investment to support increased PPE consumption and redesign patient spaces to improve distancing.18 , 19 Redesign and addition of institutional capacity is thus necessary if these IPC gains are to be sustained in the postpandemic era.

Conclusions

In conclusion, while preventing health care-associated spread of COVID-19 is a priority for IPC, the impetus provided by the ongoing pandemic provides a window of opportunity to demonstrate the potential benefit of heightened IPC strategies in controlling the major health problem of HAIs and MDROs. Enhanced IPC strategies should be continued in some form even after the pandemic is over.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This study was not grant-funded.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.019.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Rhee C, Baker MA, Klompas M. The COVID-19 infection control arms race. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Ferro EG, Zhou G, Hashimoto D, Bhatt DL. Association between universal masking in a health care system and SARS-CoV-2 positivity among health care workers. JAMA. 2020;324:703–704. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu YA, Hsu YC, Lin MH, et al. Hospital visiting policies in the time of coronavirus disease 2019: a nationwide website survey in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83:566–570. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wee LE, Conceicao EP, Sim XYJ, Ko KKK, Ling ML, Venkatachalam I. Reduction in healthcare-associated respiratory viral infections during a COVID-19 outbreak. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1579–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mermel LA, Jefferson JA, Smit MA, Auld DB. Prevention of hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections: assessment of a multimodal intervention program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40:362–364. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linam WM, Marrero EM, Honeycutt MD, Wisdom CM, Gaspar A, Vijayan V. Focusing on families and visitors reduces healthcare associated respiratory viral infections in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2019;4:e242. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMullen KM, Smith BA, Rebmann T. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on hospital acquired infection rates in the United States: predictions and early results. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:1409–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meda M, Gentry V, Reidy P, Garner D. Unintended consequences of long sleeved gowns in critical care setting during COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106:605–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yap FH, Gomersall CD, Fung KS, et al. Increase in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus acquisition rate and change in pathogen pattern associated with an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:511–516. doi: 10.1086/422641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong JEL, Leo YS, Tan CC. COVID-19 in Singapore-current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. 2020;323:1243-1244 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wee LE, Sim XYJ, Conceicao EP, et al. Containment of COVID-19 cases among healthcare workers: the role of surveillance, early detection, and outbreak management. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41:765–771. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wee LE, Hsieh JYC, Phua GC, et al. Respiratory surveillance wards as a strategy to reduce nosocomial transmission of COVID-19 through early detection: the experience of a tertiary-care hospital in Singapore. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41:820–825. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wee LE, Sim XYJ, Conceicao EP, et al. Containing COVID-19 outside the isolation ward: the impact of an infection control bundle on environmental contamination and transmission in a cohorted general ward. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:1056–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wee LE, Sim JXY, Conceicao EP, Aung MK, Tan JY, Venkatachalam I. Containment of COVID-19 amongst ancillary healthcare workers: an integral component of infection control. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106:392–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong SCY, Kwong RT, Wu TC, et al. Risk of nosocomial transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: an experience in a general ward setting in Hong Kong. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yau YH, Chandrasegaran D, Badarudin A. The ventilation of multiple-bed hospital wards in the tropics: a review. Build Environ. 2011;46:1125–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ling ML, How KB. Impact of a hospital-wide hand hygiene promotion strategy on healthcare-associated infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;1:13. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wee LE, Sim JXY, Conceicao EP, et al. Minimising intra-hospital transmission of COVID-19: the role of social distancing. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:113–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wee LE, Fan EMP, Heng R, et al. Construction of a container isolation ward: a rapidly scalable modular approach to expand isolation capacity during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soo RJJ, Chiew CJ, Ma S, Pung R, Lee V. Decreased influenza incidence under COVID-19 control measures, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1933–1935. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care–associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wee LE, Ko KKK, Ho WQ, Kwek GTC, Tan TT, Wijaya L. Community-acquired viral respiratory infections amongst hospitalised inpatients during a COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore: coinfection and clinical outcomes. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104436. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punjabi CD, Madaline T, Gendlina I, Chen V, Nori P, Pirofski LA. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in respiratory cultures and diagnostic performance of the MRSA nasal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wee LE, Sim JXY, Conceicao EP, Aung MK, Ng IM, Ling ML. Re: 'Personal protective equipment protecting healthcare workers in the Chinese epicenter of COVID-19' by Zhao et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1719–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liew Y, Lee WHL, Tan L, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programme: a vital resource for hospitals during the global outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffiths R, Fernandez R, Halcomb E. Reservoirs of MRSA in the acute hospital setting: a systematic review. Contemp Nurs. 2002;13:38–49. doi: 10.5172/conu.13.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aranega-Bou P, George RP, Verlander NQ, Paton S, Bennett A, Moore G. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae dispersal from sinks is linked to drain position and drainage rates in a laboratory model system. J Hosp Infect. 2019;102:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bentivegna E, Alessio G, Spuntarelli V, et al. Impact of COVID-19 prevention measures on risk of health care-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Infect Control. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ponce-Alonso M, Sáez de la Fuente J, Rincón-Carlavilla A, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on nosocomial clostridioides difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;8:1–5. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cai Y, Venkatachalam I, Tee NW, et al. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use among adult inpatients in Singapore acute-care hospitals: results from the first national point prevalence survey. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_2):S61–S67. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chow EJ, Mermel LA. Hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections: incidence, morbidity, and mortality in pediatric and adult patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx006. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toh TH, Hii KC, Fieldhouse JK, et al. High prevalence of viral infections among hospitalized pneumonia patients in equatorial Sarawak, Malaysia. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:ofz074. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong HL, Hong SB, Ko GB, et al. Viral infection is not uncommon in adult patients with severe hospital-acquired pneumonia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong SC, Lam GK, Au Yeung CH, et al. Absence of nosocomial influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infection in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) era: implication of universal masking in hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.