Abstract

Aims/Introduction

Recent clinical trials on sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors showed improved outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes at a high risk of cardiovascular events. However, the underlying effects on endothelial function remain unclear.

Materials and Methods

The effect of empagliflozin on endothelial function in cardiovascular high risk diabetes mellitus: Multi‐center placebo‐controlled double‐blind randomized (EMBLEM) trial in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease showed empagliflozin treatment for 24 weeks had no effect on peripheral endothelial function measured by reactive hyperemia peripheral arterial tonometry. This post‐hoc analysis of the EMBLEM trial included a detailed evaluation of the effects of empagliflozin on peripheral endothelial function in order to elucidate the clinical characteristics of responders or non‐responders to treatment.

Results

Of the 47 patients randomized into the empagliflozin group, 21 (44.7%) showed an increase in the reactive hyperemia index (RHI) after 24 weeks of intervention, with no apparent difference in the clinical characteristics between patients whose RHI either increased (at least >0) or did not increase. There was also no obvious difference between the treatment groups in the proportion of patients who had a clinically meaningful change (≥15%) in log‐transformed RHI. No correlation was found between changes in RHI and clinical variables, such as vital signs and laboratory parameters.

Conclusions

Treatment with empagliflozin for 24 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease did not affect peripheral endothelial function, and was not related to changes in clinical variables, including glycemic parameters. These findings suggest that the actions of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors other than direct improvement in peripheral endothelial function were responsible, at least in the early phase, for the clinical benefits found in recent cardiovascular outcome trials.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Empagliflozin, Endothelial function

This secondary analysis of the effect of empagliflozin on endothelial function in cardiovascular high risk diabetes mellitus: Multi‐center placebo‐controlled double‐blind randomized trial included a detailed evaluation of the effect of empagliflozin treatment on endothelial function, its association with clinical variables and the clinical characteristics of responders or non‐responders to treatment. There was no significant difference between the treatment groups in the proportion of patients who had a clinically meaningful change (≥15%) in log‐transformed reactive hyperemia index. No correlation was also observed between changes in reactive hyperemia index and clinical variables, such as vital signs and laboratory parameters.

Introduction

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are expected to have favorable effects on multifaceted cardiovascular pathways through hemodynamic and metabolic modulations beyond the known glucose‐lowering action of these agents 1 , 2 , 3 . For example, in the Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients–Removing Excess Glucose (EMPA‐REG OUTCOME), empagliflozin markedly reduced the risk of composite cardiovascular outcomes, heart failure hospitalization and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes at a high risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) 4 . Subsequent cardiovascular outcome trials also showed that SGLT2 inhibitors consistently improved cardiovascular outcomes, especially heart failure‐ and kidney‐related outcomes 5 , 6 , 7 . These results suggested that the hemodynamic actions of SGLT2 inhibitors are the predominant factor reducing the risk of these two outcomes, compared with the metabolic and anti‐atherogenic actions of the agent. However, the precise and definitive mechanisms by which SGLT2 inhibitors improved those outcomes, and their clinical effects on vascular function have yet to be fully elucidated.

The recent effect of empagliflozin on endothelial function in cardiovascular high risk diabetes mellitus: Multi‐center placebo‐controlled double‐blind randomized (EMBLEM) trial investigated whether empagliflozin added to standard therapy improved peripheral endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes and established CVDs, and showed that 24 weeks of treatment did not affect endothelial function compared with placebo 8 . However, the study did not include a detailed evaluation of responders and non‐responders to empagliflozin therapy. To better understand the profound effects of empagliflozin on endothelial function, we carried out a secondary and exploratory analysis using data obtained from the EMBLEM trial. The present also reports the effects of empagliflozin on other clinical parameters and safety information obtained from the EMBLEM trial.

Methods

Trial design and patients

The EMBLEM trial (UMIN000024502) was an investigator‐initiated, prospective, multicenter, placebo‐controlled, double‐blinded, randomized trial undertaken in 16 centers in Japan. The current secondary study was an exploratory post‐hoc analysis of data obtained from that trial 8 . The original rationale and protocol of the trial have been reported previously 9 , and the full list of inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria is described in Data S1. In brief, eligible participants included those with type 2 diabetes, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) between 6.0 and 10.0%, taking stable glucose‐lowering medications for at least 1 month before providing consent, and a history of established CVD, including heart failure with the exception of New York Heart Association functional classification IV, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease or the presence of coronary artery stenosis (≥50%), as detected by imaging modalities.

The trial was approved by the institutional review boards of the individual sites, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the current legal regulations in Japan. The participants received an adequate explanation of the trial before they provided written informed consent.

Randomization and masking

All participants who met the criteria for enrollment were assigned randomly (1:1) in a double‐blind manner to treatment with either empagliflozin or placebo, using the Web‐based minimization dynamic allocation method stratified according to HbA1c (<7.0 or ≥7.0%), age (<65 years or ≥65 years), systolic blood pressure (<140 mmHg or ≥140 mmHg) and current smoking habit (smoker or non‐smoker) at the time of screening 10 . After randomization, all researchers involved with various aspects of the trial remained masked to the group assignments until after database lock.

Outcome measures

The original primary outcome in the EMBLEM trial was the change from baseline to 24 weeks in the reactive hyperemia index (RHI), measured by reactive hyperemia‐peripheral arterial tonometry (RH‐PAT) 8 . The secondary efficacy end‐points were changes from baseline to 24 weeks in the following parameters: augmentation index, standard deviation of the normal‐to‐normal intervals, ratio of low to high frequency evaluated simultaneously and automatically by RH‐PAT, and standard laboratory data including glycemic, lipid and renal parameters. In the present post‐hoc analyses, we compared the baseline clinical characteristics of patients whose RHI increased (>0) or did not increase (≤0) during the 24 weeks of treatment. In addition, post‐hoc responder analyses were carried out to investigate the proportion of patients who had a clinically meaningful change in log‐transformed RHI (≥15%) from baseline to 24 weeks 11 , 12 . To assess the change in plasma volume associated with empagliflozin treatment, estimated plasma volume (ePV) was calculated by the Strauss formula 13 . No other clinical parameters were added to the secondary analyses.

RH‐PAT analyses

Peripheral endothelial function was measured by RH‐PAT using the Endo‐PAT2000 device (Itamar Medical, Caesarea, Israel). The detailed principles and measurement procedures of RH‐PAT have been described previously 9 , 14 , 15 . In brief, the RH‐PAT measurements were carried out in the morning at baseline and at 24 weeks, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The measurements were carried out while the participant was in a fasted state and before them taking their medications for the test day. After at least 15 min of rest on a bed in the supine position, the baseline pulse amplitude was recorded from each fingertip for 6 min. The cuff was then inflated to 60 mmHg above systolic blood pressure or 200 mmHg for 5 min. After cuff deflation, the pulse amplitude was recorded for 5 min.

Safety

Throughout the trial, safety information was collected for the intention‐to‐treat population by recording serious adverse events (AEs) regardless of the causal relationship to the trial drugs and protocol. Predefined AEs of special interest, such as hepatic injury, decreased kidney function, metabolic acidosis, ketoacidosis, diabetic ketoacidosis and events involving lower limb amputation, were also collected (Data S2) 9 .

Statistical analysis

The planned statistical analyses have been described previously 9 . All the analyses were carried out on the full analysis set, which included all participants who had received at least one dose of treatment after randomization and who did not have any serious violation of the protocol (e.g., not providing informed consent). In the original primary analysis, the means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by analysis of covariance adjusted for the allocation factors at randomization. The summary statistics were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables, or number (%) for categorical variables. Intergroup differences were compared using t‐tests for continuous variables, or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The proportion of patients who had clinically meaningful changes was compared between the treatment groups using the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test. The correlation between the changes in RHI and each measurement was evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. All P‐values were two‐tailed, with values <0.05 considered to be statistically significant. No adjustment for multiplicity was carried out for the efficacy end‐points. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

A total of 119 patients were screened, of whom 117 were randomized (Figure 1). Six patients in the empagliflozin group and four patients in the placebo group dropped out before receiving the study drug, whereas two patients in the placebo group were excluded due to a serious protocol violation. Finally, 105 patients were included in the full analysis set (52 in the empagliflozin group and 53 in the placebo group).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study.

The baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were comparable between the two treatment groups (Table 1). The mean age of the participants was 64.9 ± 10.4 years, and the mean type 2 diabetes duration was 13.2 ± 10.9 years. The mean body mass index (BMI) at baseline was 26.4 ± 5.3 kg/m2, whereas the blood pressure of the patients was relatively well controlled (systolic 133.2 ± 15.0 mmHg, diastolic 75.7 ± 10.5 mmHg). The mean HbA1c at baseline was 7.2% (55 mmol/mol), with a large proportion of the patients having taken a dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor and metformin. All patients had at least one established cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, and almost all had been receiving medications for hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Variables | Empagliflozin (n = 52) | Placebo (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.4 ± 11.1 | 64.1 ± 9.9 |

| Women | 16 (30.8) | 17 (32.1) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 132.8 ± 15.2 | 133.0 ± 14.5 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76.4 ± 11.5 | 74.9 ± 9.5 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 73.8 ± 13.3 | 71.9 ± 9.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.2 ± 5.1 | 26.9 ± 5.5 |

| HbA1c, % (mmol/mol) | 7.2 ± 0.8 (55 ± 9) | 7.2 ± 0.9 (55 ± 10) |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 13.6 ± 13.2 | 13.0 ± 8.3 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 67.0 ± 12.5 | 69.2 ± 13.9 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 15 (28.8) | 14 (26.4) |

| Current smoking | 9 (17.3) | 13 (24.5) |

| History | ||

| Hypertension | 41 (78.8) | 36 (67.9) |

| Dyslipidemia | 39 (75.0) | 38 (71.7) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 (11.5) | 15 (28.3) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 50 (96.2) | 44 (83.0) |

| Heart failure | 23 (44.2) | 19 (35.8) |

| Myocardial infarction | 12 (23.1) | 13 (24.5) |

| Angina | 21 (40.4) | 11 (20.8) |

| Arteriosclerosis obliterans | 6 (11.5) | 1 (1.9) |

| Treatment | ||

| Non‐diabetic | ||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 31 (59.6) | 38 (71.7) |

| Beta‐blocker | 19 (36.5) | 19 (35.8) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 26 (50.0) | 25 (47.2) |

| MRA | 9 (17.3) | 5 (9.4) |

| Diuretic | 8 (15.4) | 10 (18.9) |

| Statin | 43 (82.7) | 36 (67.9) |

| Antiplatelet or anticoagulant | 30 (57.7) | 34 (64.2) |

| Diabetes | ||

| Insulin | 5 (9.6) | 5 (9.4) |

| Metformin | 25 (48.1) | 28 (52.8) |

| Sulfonylurea | 8 (15.4) | 12 (22.6) |

| Alpha‐glucosidase inhibitor | 8 (15.4) | 8 (15.1) |

| Thiazolidinedione | 12 (23.1) | 13 (24.5) |

| DPP‐4 inhibitor | 37 (71.2) | 36 (67.9) |

| GLP‐1RA | 3 (5.8) | 2 (3.8) |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP‐1RA, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

Detailed effect of empagliflozin on endothelial function

As reported previously 8 , the absolute change in RHI from baseline to 24 weeks was −0.006 ± 0.478 (empagliflozin) and −0.025 ± 0.454 (placebo), with no significant intergroup difference observed (−0.020, 95% CI −0.199 to 0.158, P = 0.821). Endothelial function assessed by dividing the patients into subgroups according to their baseline RHI values (1.67 or 2.10) to discriminate normal or abnormal endothelial function 16 showed no significant difference in changes in RHI caused by treatment in the two subgroups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of the primary endpoint, grouped according to baseline reactive hyperemia peripheral arterial tonometry index categories

| Subgroup stratified by baseline RHI values | Empagliflozin | Placebo | Group difference | 95% CI | P‐value | P‐value for interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean change in RHI | 95% CI | n | Mean change in RHI | 95% CI | |||||

| <1.67 | 19 | 0.117 | −0.057 to 0.292 | 19 | 0.075 | −0.064 to 0.214 | 0.042 | −0.173 to 0.258 | 0.694 | 0.916 |

| ≥1.67, <2.10 | 15 | 0.109 | −0.070 to 0.287 | 20 | 0.111 | −0.121 to 0.342 | −0.002 | −0.300 to 0.297 | 0.990 | |

| ≥2.10 | 13 | −0.319 | −0.706 to 0.068 | 12 | −0.411 | −0.668 to − 0.154 | 0.092 | −0.356 to 0.539 | 0.676 | |

RHI, reactive hyperemia peripheral arterial tonometry index.

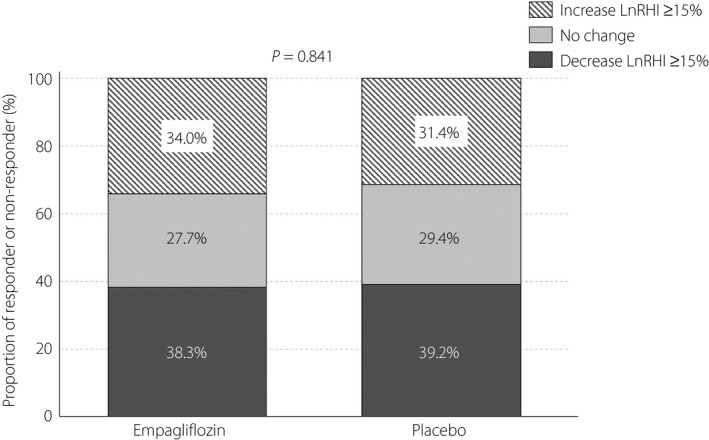

In patients with RHI data at both baseline and 24 weeks (empagliflozin‐arm n = 47, placebo‐arm n = 51), 21 patients (44.7%) receiving empagliflozin and 24 patients (47.1%) receiving placebo showed increases in RHI after 24 weeks of intervention, whereas the RHI in the remaining patients either remained unchanged or decreased. When the participants were divided into subgroups based on an increase (>0) in RHI or not (≤0) after 24 weeks of intervention, no significant difference in baseline clinical manifestations was observed between the two subgroups for either treatment (Table 3). Furthermore, a ≥15% increase in log‐transformed RHI was seen in 16 patients (34.0%) in the empagliflozin group and 16 patients (31.4%) in the placebo group, with no obvious difference in the proportion of responders or non‐responders between the two treatment groups (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of the patients, stratified according to the change in reactive hyperemia peripheral arterial tonometry index from baseline to 24 weeks

| Variables | Empagliflozin | Placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHI increase (n = 21) | No increase (n = 26) | P‐value | RHI increase (n = 24) | No increase (n = 27) | P‐value | |

| Age (years) | 65.4 ± 11.3 | 65.3 ± 11.3 | 0.992 | 62.7 ± 7.4 | 65.0 ± 11.9 | 0.413 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 4 (19.0) | 11 (42.3) | 0.121 | 8 (33.3) | 8 (29.6) | 1.000 |

| Male | 17 (81.0) | 15 (57.7) | 16 (66.7) | 19 (70.4) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135.0 ± 14.8 | 131.8 ± 16.1 | 0.498 | 133.9 ± 12.8 | 130.3 ± 14.4 | 0.350 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77.8 ± 10.1 | 76.3 ± 12.1 | 0.670 | 78.8 ± 6.6 | 71.3 ± 10.7 | 0.005 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 75.6 ± 12.7 | 72.5 ± 14.3 | 0.433 | 71.6 ± 11.3 | 71.6 ± 8.8 | 0.999 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.6 ± 3.7 | 26.2 ± 6.2 | 0.770 | 28.3 ± 6.6 | 25.9 ± 4.2 | 0.128 |

| HbA1c, % (mmol/mol) | 6.9 ± 0.8 (52 ± 9) | 7.3 ± 0.7 (56 ± 8) | 0.088 | 7.4 ± 1.1 (57 ± 12) | 7.1 ± 0.7 (54 ± 8) | 0.212 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 12.5 ± 11.3 | 14.9 ± 15.3 | 0.579 | 11.7 ± 7.7 | 14.6 ± 9.0 | 0.280 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 67.3 ± 11.1 | 65.7 ± 13.7 | 0.669 | 70.1 ± 9.6 | 68.2 ± 17.3 | 0.629 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | ||||||

| Yes | 5 (23.8) | 9 (34.6) | 0.535 | 4 (16.7) | 10 (37.0) | 0.127 |

| No | 15 (71.4) | 17 (65.4) | 20 (83.3) | 17 (63.0) | ||

| Current smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (14.3) | 4 (15.4) | 1.000 | 5 (20.8) | 8 (29.6) | 0.534 |

| No | 18 (85.7) | 22 (84.6) | 19 (79.2) | 19 (70.4) | ||

| History | ||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 18 (85.7) | 20 (76.9) | 0.711 | 19 (79.2) | 15 (55.6) | 0.136 |

| No | 3 (14.3) | 6 (23.1) | 5 (20.8) | 12 (44.4) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | ||||||

| Yes | 17 (81.0) | 17 (65.4) | 0.330 | 18 (75.0) | 18 (66.7) | 0.554 |

| No | 4 (19.0) | 9 (34.6) | 6 (25.0) | 9 (33.3) | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (9.5) | 3 (11.5) | 1.000 | 8 (33.3) | 6 (22.2) | 0.531 |

| No | 19 (90.5) | 23 (88.5) | 16 (66.7) | 21 (77.8) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Yes | 20 (95.2) | 25 (96.2) | 1.000 | 7 (29.2) | 2 (7.4) | 0.066 |

| No | 1 (4.8) | 1 (3.8) | 17 (70.8) | 25 (92.6) | ||

| Heart failure | ||||||

| Yes | 7 (33.3) | 14 (53.8) | 0.239 | 14 (58.3) | 18 (66.7) | 0.575 |

| No | 14 (66.7) | 12 (46.2) | 10 (41.7) | 9 (33.3) | ||

| Myocardial infarction | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (14.3) | 7 (26.9) | 0.475 | 4 (16.7) | 8 (29.6) | 0.335 |

| No | 18 (85.7) | 19 (73.1) | 20 (83.3) | 19 (70.4) | ||

| Angina | ||||||

| Yes | 9 (42.9) | 9 (34.6) | 0.763 | 5 (20.8) | 4 (14.8) | 0.718 |

| No | 12 (57.1) | 17 (65.4) | 19 (79.2) | 23 (85.2) | ||

| Arteriosclerosis obliterans | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (9.5) | 2 (7.7) | 1.000 | 24 (100.0) | 26 (96.3) | 1.000 |

| No | 19 (90.5) | 24 (92.3) | 0 | 1 (3.7) | ||

| Treatment | ||||||

| Non‐diabetic | ||||||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (66.7) | 14 (53.8) | 0.551 | 16 (66.7) | 20 (74.1) | 0.759 |

| No | 7 (33.3) | 12 (46.2) | 8 (33.3) | 7 (25.9) | ||

| Beta‐blocker | ||||||

| Yes | 8 (38.1) | 8 (30.8) | 0.758 | 10 (41.7) | 8 (29.6) | 0.396 |

| No | 13 (61.9) | 18 (69.2) | 14 (58.3) | 19 (70.4) | ||

| Calcium channel blocker | ||||||

| Yes | 11 (52.4) | 15 (57.7) | 0.774 | 11 (45.8) | 17 (63.0) | 0.267 |

| No | 10 (47.6) | 11 (42.3) | 13 (54.2) | 10 (37.0) | ||

| MRA | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (9.5) | 6 (23.1) | 0.269 | 22 (91.7) | 24 (88.9) | 1.000 |

| No | 19 (90.5) | 20 (76.9) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (11.1) | ||

| Diuretic | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (14.3) | 4 (15.4) | 1.000 | 20 (83.3) | 21 (77.8) | 0.731 |

| No | 18 (85.7) | 22 (84.6) | 4 (16.7) | 6 (22.2) | ||

| Statin | ||||||

| Yes | 18 (85.7) | 21 (80.8) | 0.715 | 17 (70.8) | 17 (63.0) | 0.767 |

| No | 3 (14.3) | 5 (19.2) | 7 (29.2) | 10 (37.0) | ||

| Antiplatelet or anticoagulant | ||||||

| Yes | 12 (57.1) | 14 (53.8) | 1.000 | 14 (58.3) | 18 (66.7) | 0.575 |

| No | 9 (42.9) | 12 (46.2) | 10 (41.7) | 9 (33.3) | ||

| Diabetic | ||||||

| Insulin | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (9.5) | 2 (7.7) | 1.000 | 3 (12.5) | 2 (7.4) | 0.656 |

| No | 19 (90.5) | 24 (92.3) | 21 (87.5) | 25 (92.6) | ||

| Metformin | ||||||

| Yes | 10 (47.6) | 14 (53.8) | 0.772 | 13 (54.2) | 14 (51.9) | 1.000 |

| No | 11 (52.4) | 12 (46.2) | 11 (45.8) | 13 (48.1) | ||

| Sulfonylurea | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (19.0) | 3 (11.5) | 0.684 | 6 (25.0) | 6 (22.2) | 1.000 |

| No | 17 (81.0) | 23 (88.5) | 18 (75.0) | 21 (77.8) | ||

| Alpha‐glucosidase inhibitor | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (9.5) | 6 (23.1) | 0.269 | 4 (16.7) | 4 (14.8) | 1.000 |

| No | 19 (90.5) | 20 (76.9) | 20 (83.3) | 23 (85.2) | ||

| Thiazolidinedione | ||||||

| Yes | 6 (28.6) | 5 (19.2) | 0.505 | 6 (25.0) | 6 (22.2) | 1.000 |

| No | 15 (71.4) | 21 (80.8) | 18 (75.0) | 21 (77.8) | ||

| DPP‐4 inhibitor | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (66.7) | 19 (73.1) | 0.752 | 15 (62.5) | 19 (70.4) | 0.569 |

| No | 7 (33.3) | 7 (26.9) | 9 (37.5) | 8 (29.6) | ||

| GLP‐1RA | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (9.5) | 1 (3.8) | 0.579 | 2 (8.3) | 0 | 0.216 |

| No | 19 (90.5) | 25 (96.2) | 22 (91.7) | 27 (100.0) | ||

Data are mean ± standard deviation or n (%). ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP‐1RA, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; RHI, reactive hyperemia peripheral arterial tonometry index.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients who had a deterioration (decrease ≥15%), remained unchanged or an improvement (increase ≥15%) in log‐transformed RHI (LnRHI). The numbers on the bars indicate the proportion (%) of patients in each category.

Effects on other parameters

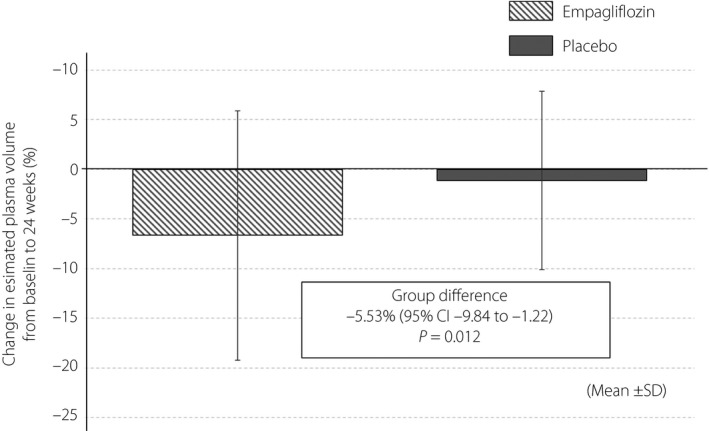

The detailed changes in the clinical and laboratory parameters from baseline to 24 weeks and intergroup comparisons are shown in Table 4. The 24 weeks of empagliflozin treatment reduced both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, with a borderline difference between the treatment groups. However, we observed no significant difference in heart rate or double product between the two groups. Reductions in BMI, fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c and glycoalbumin in the empagliflozin group were significantly greater than those in the placebo group. Empagliflozin also increased serum total ketone bodies, hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, and decreased the serum levels of triglyceride and uric acid. In addition, 24 weeks of empagliflozin treatment significantly reduced ePV to a greater extent than that observed with placebo (Figure 3). No apparent differences in renal biomarkers were observed between the two treatment groups. Empagliflozin treatment also did not impact augmentation index, standard deviation of the normal‐to‐normal intervals or ratio of low to high frequency measured concurrently by RH‐PAT (Table S1). Finally, we found no significant correlation between changes in RHI and the clinical and laboratory parameters measured over a period of 24 weeks (Table S2).

Table 4.

Changes in glycemic and non‐glycemic data from baseline to 24 weeks

| Variables | Empagliflozin | Placebo | Group difference (95% CI) | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | mean ± SD | n | mean ± SD | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||

| Baseline | 52 | 132.81 ± 15.20 | 53 | 133.02 ± 14.52 | −0.21 (−5.97 to 5.54) | 0.942 |

| 24 weeks | 50 | 124.92 ± 14.39 | 52 | 130.60 ± 13.52 | −5.68 (−11.16 to − 0.19) | 0.043 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 50 | −7.56 ± 16.53 | 52 | −2.13 ± 12.11 | −5.43 (−11.14 to 0.29) | 0.063 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||

| Baseline | 52 | 76.38 ± 11.52 | 53 | 74.94 ± 9.53 | 1.44 (−2.66 to 5.54) | 0.487 |

| 24 weeks | 50 | 72.64 ± 9.16 | 52 | 74.71 ± 11.26 | −2.07 (−6.10 to 1.95) | 0.310 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 50 | −3.70 ± 8.66 | 52 | −0.17 ± 9.92 | −3.53 (−7.18 to 0.13) | 0.058 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | ||||||

| Baseline | 52 | 73.85 ± 13.30 | 53 | 71.90 ± 9.84 | 1.94 (−2.59 to 6.47) | 0.397 |

| 24 weeks | 50 | 74.18 ± 16.12 | 51 | 70.92 ± 10.20 | 3.26 (−2.05 to 8.57) | 0.227 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 50 | 0.52 ± 15.40 | 51 | −0.65 ± 8.38 | 1.17 (−3.72 to 6.06) | 0.637 |

| Double product (systolic blood pressure × heart rate) | ||||||

| Baseline | 52 | 9,820 ± 2,117 | 53 | 9,601 ± 1,854 | 219 (−552 to 990) | 0.574 |

| 24 weeks | 50 | 9,221 ± 1,975 | 51 | 9,286 ± 1,778 | −64 (−807 to 678) | 0.864 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 50 | −549 ± 2,331 | 51 | −245 ± 1,223 | −304 (−1,044 to 437) | 0.416 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Baseline | 51 | 26.17 ± 5.10 | 52 | 26.94 ± 5.47 | −0.76 (−2.83 to 1.30) | 0.465 |

| 24 weeks | 50 | 25.68 ± 4.94 | 52 | 26.71 ± 5.45 | −1.03 (−3.07 to 1.01) | 0.320 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 49 | −0.75 ± 0.97 | 51 | −0.17 ± 0.80 | −0.58 (−0.93 to − 0.23) | 0.002 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 50 | 141.44 ± 24.95 | 52 | 146.44 ± 34.79 | −5.00 (−16.87 to 6.87) | 0.405 |

| 24 weeks | 47 | 127.79 ± 25.26 | 51 | 145.53 ± 42.66 | −17.74 (−31.70 to − 3.78) | 0.013 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 46 | −17.93 ± 21.96 | 51 | −0.80 ± 37.63 | −17.13 (−29.43 to − 4.83) | 0.007 |

| HbA1c, % (mmol/mol) | ||||||

| Baseline | 52 | 7.2 ± 0.8 (55 ± 9) | 52 | 7.2 ± 0.9 (55 ± 10) | −0.04 (−0.37 to 0.29) | 0.819 |

| 24 weeks | 48 | 6.9 ± 0.6 (52 ± 7) | 52 | 7.3 ± 0.9 (56 ± 10) | −0.35 (−0.65 to − 0.05) | 0.023 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 48 | −0.25 ± 0.49 | 52 | 0.07 ± 0.71 | −0.32 (−0.56 to − 0.07) | 0.011 |

| Glycoalbumin (%) | ||||||

| Baseline | 51 | 18.14 ± 3.07 | 50 | 18.48 ± 3.35 | −0.34 (−1.61 to 0.92) | 0.591 |

| 24 weeks | 48 | 16.79 ± 2.84 | 51 | 18.38 ± 3.41 | −1.59 (−2.84 to − 0.35) | 0.013 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 47 | −1.37 ± 1.78 | 49 | 0.14 ± 2.14 | −1.51 (−2.31 to − 0.72) | <0.001 |

| Total ketone bodies (μmoL/L) | ||||||

| Baseline | 46 | 65.36 ± 58.26 | 51 | 86.16 ± 119.27 | −20.80 (−58.22 to 16.63) | 0.272 |

| 24 weeks | 45 | 99.60 ± 99.83 | 50 | 83.10 ± 119.67 | 16.50 (−28.26 to 61.25) | 0.466 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 43 | 33.93 ± 85.48 | 50 | −4.40 ± 68.43 | 38.34 (6.03 to 70.65) | 0.021 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 51 | 13.96 ± 1.59 | 53 | 13.73 ± 1.46 | 0.23 (−0.36 to 0.82) | 0.443 |

| 24 weeks | 49 | 14.54 ± 1.60 | 52 | 13.83 ± 1.34 | 0.71 (0.12 to 1.29) | 0.018 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 48 | 0.58 ± 0.98 | 52 | 0.12 ± 0.71 | 0.46 (0.12 to 0.80) | 0.009 |

| Hematocrit (%) | ||||||

| Baseline | 51 | 41.58 ± 4.56 | 53 | 41.33 ± 4.15 | 0.25 (−1.45 to 1.95) | 0.774 |

| 24 weeks | 49 | 43.58 ± 4.80 | 52 | 41.72 ± 3.75 | 1.86 (0.15 to 3.57) | 0.033 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 48 | 2.05 ± 3.59 | 52 | 0.38 ± 2.45 | 1.68 (0.44 to 2.91) | 0.008 |

| Non‐high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 113.79 ± 32.99 | 52 | 111.40 ± 24.49 | 2.39 (−9.23 to 14.01) | 0.684 |

| 24 weeks | 47 | 114.55 ± 29.42 | 52 | 114.91 ± 30.30 | −0.36 (−12.28 to 11.56) | 0.953 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 45 | −3.20 ± 19.99 | 52 | 3.51 ± 18.28 | −6.71 (−14.48 to 1.06) | 0.090 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 51 | 141.00 ± 107.49 | 52 | 107.62 ± 56.38 | 33.38 (−0.40 to 67.17) | 0.053 |

| 24 weeks | 48 | 116.65 ± 65.98 | 52 | 111.62 ± 48.81 | 5.03 (−18.20 to 28.26) | 0.668 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 47 | −27.57 ± 93.14 | 52 | 4.00 ± 39.54 | −31.57 (−60.87 to − 2.28) | 0.035 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 50 | 5.72 ± 1.36 | 52 | 5.32 ± 1.08 | 0.40 (−0.09 to 0.89) | 0.105 |

| 24 weeks | 48 | 5.03 ± 1.31 | 52 | 5.48 ± 1.40 | −0.46 (−0.99 to 0.08) | 0.096 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 46 | −0.61 ± 0.84 | 52 | 0.16 ± 1.09 | −0.77 (−1.16 to − 0.39) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||||

| Baseline | 51 | 67.02 ± 12.50 | 53 | 69.23 ± 13.94 | −2.22 (−7.36 to 2.93) | 0.395 |

| 24 weeks | 49 | 65.34 ± 14.00 | 52 | 68.71 ± 15.26 | −3.37 (−9.15 to 2.41) | 0.250 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 48 | −1.75 ± 6.72 | 52 | −0.31 ± 6.92 | −1.45 (−4.15 to 1.26) | 0.292 |

| Urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio (mg/g Cre) | ||||||

| Baseline | 47 | 65.16 ± 116.67 | 48 | 46.70 ± 79.97 | 18.46 (−22.45 to 59.37) | 0.372 |

| 24 weeks | 44 | 79.22 ± 234.97 | 48 | 31.57 ± 37.37 | 47.65 (−24.51 to 119.82) | 0.190 |

| Change from baseline to 24 weeks | 41 | −24.63 ± 88.52 | 46 | −16.61 ± 59.80 | −8.02 (−40.73 to 24.69) | 0.626 |

| Urinary L‐FABP (μg/g Cre) | ||||||

| Baseline | 41 | 9.20 ± 18.68 | 43 | 7.24 ± 20.98 | 1.96 (−6.66 to 10.57) | 0.653 |

| 24 weeks | 40 | 6.07 ± 6.55 | 43 | 4.37 ± 4.86 | 1.70 (−0.84 to 4.24) | 0.186 |

| Baseline | 38 | −3.29 ± 14.92 | 41 | −3.23 ± 19.12 | −0.06 (−7.72 to 7.60) | 0.988 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration ratio; L‐FABP, liver‐type fatty acid‐binding protein.

Figure 3.

Changes in estimated plasma volume. Percentage changes in estimated plasma volume between baseline and 24 weeks, calculated by the Strauss formula. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Safety

The AEs documented during the trial period are summarized in Table S3. Empagliflozin was well tolerated, and no predefined AEs of special interest (lower limb amputation, decreased kidney function, hepatic injury or metabolic acidosis) were documented in the empagliflozin group. There were seven serious AEs in three patients in the empagliflozin group, and a serious AE in one patient in the placebo group. In the empagliflozin group, one patient permanently discontinued the study drug as a result of the development of hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia and ventricular tachycardia, whereas another patient temporarily discontinued treatment due to neurally mediated syncope and a urinary tract infection. In the placebo group, one patient permanently discontinued treatment as a result of predefined AEs of special interest (hepatic injury). Although development of a non‐fatal stroke was reported in one patient in the empagliflozin group, it proved to be asymptomatic and an old‐type infarction accidentally shown by imaging modality 110 days after initiation of the study drug.

Discussion

The current detailed secondary analyses used data from the EMBLEM trial in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes and established CVD, and showed no obvious effects of empagliflozin on endothelial function and no apparent differences in the clinical characteristics between participants with or without an improvement in peripheral endothelial function. These results support the findings of recent cardiovascular outcome trials that the reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events observed with SGLT2 inhibitors might, in the short‐term at least, be mediated to a lesser extent by amelioration of endothelial function.

Endothelial function maintains vascular homeostasis and is degraded by metabolic disturbances, such as diabetes, as a result of increased oxidative stress and inflammatory responses 17 , 18 . Impaired endothelial function (i.e., endothelial dysfunction) is involved in the pathophysiology of diabetes‐related cardiovascular complications, including heart failure 19 . There is evidence that endothelial dysfunction is the primary step in the development of vascular atherosclerosis, and that it also plays a major role in the progression of vascular injuries 20 , 21 . In addition, endothelial dysfunction is closely related to cardiovascular events and poor prognosis 22 , 23 , 24 , with persistent dysfunction known to be associated with an increased risk of mortality 25 . Therefore, when considering the possible modes of action of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiovascular systems and the mechanisms underlying their clinical benefits, it is necessary to evaluate the effects on endothelial function as a surrogate marker.

SGLT2 inhibitors have proven multidisciplinary benefits on systemic metabolism, and cardiovascular and renal systems over and above their glucose‐lowering action 1 , 2 . Before the initiation of our trial, it was reasonable to assume that SGLT2 inhibitors possessed these multifaceted effects that could improve endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes, even those at high risk of CVD. However, in our trial, empagliflozin did not affect endothelial function 8 and other physiological parameters, including heart rate variability (HRV). To date, just a few studies have investigated the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on HRV. In 2014, Cherney et al. 26 reported that 8 weeks of empagliflozin treatment did not affect HRV in patients with type 1 diabetes, being consistent with the present finding. To better understand that effect, a placebo‐controlled double‐blind trial (the EMBODY trial) that will evaluate the effect of empagliflozin on HRV, including time and frequency domain analyses, in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute myocardial infarction is now ongoing 27 . In addition, in the current study, we found no clear difference in clinical parameters between patients whose endothelial functional index increased and in those in whom the index did not, with no correlation between changes in the index and clinical parameters. Furthermore, the present study observed no association between changes in peripheral endothelial function and other laboratory parameters that could potentially be beneficially affected by empagliflozin treatment, such as a decrease in bodyweight and blood pressure, and an increase in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. These findings suggest that empagliflozin treatment for 24 weeks had fewer direct effects on vascular function, at least in patients with type 2 diabetes and established CVD.

Impaired endothelial function and increased arterial stiffness are central physiological drivers of vascular failure 16 , 28 , and studies of these vascular parameters as surrogate markers can be used to evaluate the vascular effects of new therapies. Although various interventions, including medications, have been assessed to determine whether or not they improve vascular function 29 , this possibility with SGLT2 inhibitors is poorly understood. To date, some clinical trials have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors improve vascular function in patients with diabetes. Shigiyama et al. 30 reported that 16 weeks of treatment with the SGLT2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin, in patients with a short‐duration of type 2 diabetes and no history of atherosclerotic CVD improved endothelial function measured by flow‐mediated vasodilation compared with that associated with an increased dose of metformin. This effect was only seen in a subgroup with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes, despite no apparent difference between the treatment groups. Solini et al. 31 also reported that 2 days of treatment with dapagliflozin acutely improved endothelial function and reduced aortic stiffness in type 2 diabetes patients at low risk of cardiovascular events. Importantly, the settings and design of that study differed from our trial, and therefore might have contributed to the interstudy differences in the results observed.

Several clinical studies have also shown that empagliflozin treatment has beneficial impacts on some markers of vascular function in patients with type 2 diabetes at a relatively low cardiovascular risk and also younger patients with type 1 diabetes 26 , 32 , 33 , 34 . Those studies suggested that improved vascular function was likely to be associated with empagliflozin‐mediated glycemic and non‐glycemic actions, such as weight loss and volume contraction. This empagliflozin‐induced reduction in ePV was comparable to that reported by previous studies of SGLT2 inhibitors 13 , 35 . However, a direct effect of the agent on vascular function remains to be fully elucidated. Our trial of 24‐week treatment with empagliflozin showed that endothelial function was not affected during this time period, despite the presence of several glycemic and non‐glycemic benefits. Given the differences in design between the present study and other studies, it is likely that population bias might have, in part, influenced the findings of the present study. In addition, the intervention period in the present study might have been too short to cause favorable effects on endothelial function in the study population who possibly had advanced vascular injuries due partly to a long duration of type 2 diabetes and the presence of established CVD.

In the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial, empagliflozin markedly reduced the risk of hospitalization for HF, although it did not affect the occurrence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events 4 . In particular, we noted that the risk reduction in hospitalization for HF was observed within 6 months of starting empagliflozin therapy. Given such a rapid effect of HF prevention, we consider that hemodynamic actions and subsequent reduction in cardiac pre‐ and after‐load derived from the natriuretic effect of SGLT2 inhibitors are more dominant during the early phase of treatment compared with the effect on vascular function and atherosclerosis 1 , 3 , 36 . In addition, unfortunately we did not investigate the effect of empagliflozin on mechanistic factors, such as oxidative stress and inflammation, major factors that are known to contribute to the development of endothelial dysfunction and subsequent atherosclerosis 37 . Because our trial showed no obvious effect of empagliflozin on peripheral endothelial function assessed by RH‐PAT, it is likely that empagliflozin also had no direct effect on those mechanistic factors, at least in the present study. Meanwhile, empagliflozin appeared to affect several hemodynamic parameters, such as BMI, ePV and hemoconcentration, compared with that observed with placebo. These findings might explain our finding that 24 weeks of treatment with empagliflozin failed to improve endothelial function. Nevertheless, a recent meta‐analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials with SGLT2 inhibitors clearly showed that these agents significantly reduced the risk of major cardiac events, including cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure 7 . Therefore, the use of SGLT2 inhibitors is now recommended in several relevant guidelines to reduce cardiovascular risk 38 , 39 , 40 . In this regard, whether a longer period of SGLT2 inhibitor treatment has clinically apparent benefits on vascular function and atherosclerosis needs to be examined in greater detail.

The present study had several limitations in addition to those reported for the EMBLEM trial 8 . First, this secondary analysis might have been influenced by the post‐randomization nature of the post‐hoc analyses and the smaller number of participants. Second, although we sought to test our hypothesis in type 2 diabetes patients at high risk of cardiovascular events, similar to the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME trial, the demographic and clinical characteristics of our study group differed in several aspects from that trial. In comparison, our population had lower levels of BMI and HbA1c at baseline, and a lower prevalence of background atherosclerotic CVDs. Importantly, we only enrolled Japanese patients, and therefore, the findings of the present study might only be applicable to this population. Third, because the RH‐PAT test was measured only after 24 weeks of treatment, the shorter‐term effect that reflects SGLT2 inhibitor‐specific early hemodynamic consequences remains unclear. In addition, the long‐term effect of empagliflozin on peripheral endothelial function was not investigated. Finally, although the RH‐PAT test was non‐invasive and has no operator‐dependent influences, the measurements can be partly affected by individual conditions, intravascular volume and surroundings of the test room. Although we used a standardized operation manual for RH‐PAT to minimize these influences and standardize testing accuracy at each local site 9 , further improvement in the control of accuracy might be required to carry out multicenter clinical trials using this procedure.

In conclusion, the detailed evaluations carried out in the present study confirmed that 24 weeks of empagliflozin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and established CVD did not affect peripheral endothelial function. The present results might, therefore, confirm and emphasize the main result of the EMBLEM trial 8 .

Disclosure

AT received modest honoraria from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Fukuda Denshi, Kowa, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Novo Nordisk, Taisho Toyama, Takeda and Teijin; and a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline. MS received honorarium and an endowed chair from Boehringer Ingelheim. HT received lecture fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Kowa, Takeda, Mitsubishi Tanabe and Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho. YO received lecture fees from Astellas, AstraZeneca, MSD, Ono, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Kissei, Novartis, Kowa and Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho; and research funds from Kowa and Mitsubishi Tanabe. TT received honoraria from MSD, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk and Taisho Toyama; research funding from Kowa; and scholarships from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Astellas and Novo Nordisk. MY‐T received honoraria from Bayer, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Itamar, MSD, Nippon Shinyaku, Boehringer Ingelheim and Daiichi Sankyo. SU received research grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Kowa; non‐purpose research grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, MSD, Pfizer and Takeda; and lecture fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and MSD. YH received consulting fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe related to this study, as well as honoraria and grants from Teijin, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Takeda, Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Mochida, Nihon Kohden, Shionogi, Nippon Sigmax, Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho, Unex and Kao; and honoraria from Radiometer, Omron, Sumitomo Dainippon, Otsuka, Torii, Kowa, Fujiyakuhin, Amgen, Nippon Shinyaku, Itamar, Bayer, Eli Lilly and Ono. KN received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Astellas, Ono, Takeda, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Mitsubishi Tanabe, AstraZeneca; research grants from Amgen, Teijin, Terumo, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Asahi Kasei, Astellas, Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer; and scholarships from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Teijin, Astellas, Takeda and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1 | Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study.

Data S2 | Adverse events of special interest (AESI).

Table S1 | Changes in other parameters co‐measured by reactive hyperemia‐peripheral arterial tonometry (RH‐PAT).

Table S2 | Correlation between changes from baseline to 24 weeks in reactive hyperemia index (RHI) and the other parameters measured.

Table S3 | Adverse events.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the investigators, board members, coordinators and patients who participated in the trial. This study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly and Company. This work was also partly supported by the Uehara Memorial Foundation.

J Diabetes Investig. 2020

Clinical Trial Registry

University Hospital Medical Information Network

UMIN000024502

References

- 1. Heerspink HJ, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH, et al Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: cardiovascular and kidney effects, potential mechanisms, and clinical applications. Circulation 2016; 134: 752–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inzucchi SE, Zinman B, Wanner C, et al SGLT‐2 inhibitors and cardiovascular risk: proposed pathways and review of ongoing outcome trials. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2015; 12: 90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tanaka A, Node K. Emerging roles of sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in cardiology. J Cardiol 2017; 69: 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 644–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet 2019; 393: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tanaka A, Shimabukuro M, Machii N, et al Effect of empagliflozin on endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: results from the multicenter, randomized, placebo‐controlled, Double‐Blind EMBLEM Trial. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: e159–e161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanaka A, Shimabukuro M, Okada Y, et al Rationale and design of a multicenter placebo‐controlled double‐blind randomized trial to evaluate the effect of empagliflozin on endothelial function: the EMBLEM trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2017; 16: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics 1975; 31: 103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCrea CE, Skulas‐Ray AC, Chow M, et al Test‐retest reliability of pulse amplitude tonometry measures of vascular endothelial function: implications for clinical trial design. Vasc Med 2012; 17: 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sugiyama S, Jinnouchi H, Kurinami N, et al The SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin significantly improves the peripheral microvascular endothelial function in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus. Intern Med 2018; 57: 2147–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dekkers CCJ, Sjostrom CD, Greasley PJ, et al Effects of the sodium‐glucose co‐transporter‐2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on estimated plasma volume in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2019; 21: 2667–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuvin JT, Patel AR, Sliney KA, et al Assessment of peripheral vascular endothelial function with finger arterial pulse wave amplitude. Am Heart J 2003; 146: 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonetti PO, Pumper GM, Higano ST, et al Noninvasive identification of patients with early coronary atherosclerosis by assessment of digital reactive hyperemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44: 2137–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tanaka A, Tomiyama H, Maruhashi T, et al Physiological diagnostic criteria for vascular failure. Hypertension 2018; 72: 1060–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paneni F, Beckman JA, Creager MA, et al Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: part I. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 2436–2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu J, Zou MH. Molecular insights and therapeutic targets for diabetic endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2009; 120: 1266–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Joshi M, Kotha SR, Malireddy S, et al Conundrum of pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy: role of vascular endothelial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species, and mitochondria. Mol Cell Biochem 2014; 386: 233–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, et al A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation 1995; 92: 1355–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gutierrez E, Flammer AJ, Lerman LO, et al Endothelial dysfunction over the course of coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 3175–3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schachinger V, Britten MB, Zeiher AM. Prognostic impact of coronary vasodilator dysfunction on adverse long‐term outcome of coronary heart disease. Circulation 2000; 101: 1899–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, et al Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 845–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meigs JB, Hu FB, Rifai N, et al Biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2004; 291: 1978–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kitta Y, Obata JE, Nakamura T, et al Persistent impairment of endothelial vasomotor function has a negative impact on outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53: 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cherney DZ, Perkins BA, Soleymanlou N, et al The effect of empagliflozin on arterial stiffness and heart rate variability in subjects with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2014; 13: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kubota Y, Yamamoto T, Tara S, et al Effect of empagliflozin versus placebo on cardiac sympathetic activity in acute myocardial infarction patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: rationale. Diabetes Ther 2018; 9: 2107–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Inoue T, Node K. Vascular failure: a new clinical entity for vascular disease. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 2121–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Widlansky ME, Gokce N, Keaney JF Jr, et al The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42: 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shigiyama F, Kumashiro N, Miyagi M, et al Effectiveness of dapagliflozin on vascular endothelial function and glycemic control in patients with early‐stage type 2 diabetes mellitus: DEFENCE study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2017; 16: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Solini A, Giannini L, Seghieri M, et al Dapagliflozin acutely improves endothelial dysfunction, reduces aortic stiffness and renal resistive index in type 2 diabetic patients: a pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2017; 16: 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chilton R, Tikkanen I, Cannon CP, et al Effects of empagliflozin on blood pressure and markers of arterial stiffness and vascular resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17: 1180–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lunder M, Janic M, Japelj M, et al Empagliflozin on top of metformin treatment improves arterial function in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018; 17: 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Striepe K, Jumar A, Ott C, et al Effects of the selective sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin on vascular function and central hemodynamics in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2017; 136: 1167–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanaka A, Hisauchi I, Taguchi I, et al Effects of canagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic heart failure: a randomized trial (CANDLE). ESC Heart Fail 2020. 10.1002/ehf2.12707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heise T, Jordan J, Wanner C, et al Pharmacodynamic effects of single and multiple doses of empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther 2016; 38: 2265–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al 2019 Update to: management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018; 2020: 487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, et al 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre‐diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 255–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Deerochanawong C, Chan SP, Matawaran BJ, et al Use of sodium‐glucose co‐transporter‐2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and multiple cardiovascular risk factors: An Asian perspective and expert recommendations. Diabetes Obes Metab 2019; 21: 2354–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 | Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study.

Data S2 | Adverse events of special interest (AESI).

Table S1 | Changes in other parameters co‐measured by reactive hyperemia‐peripheral arterial tonometry (RH‐PAT).

Table S2 | Correlation between changes from baseline to 24 weeks in reactive hyperemia index (RHI) and the other parameters measured.

Table S3 | Adverse events.