Key Points

Question

Is active surveillance a safe and effective option for African American men with low-risk prostate cancer?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort study that included 8726 men with low-risk prostate cancer followed up for a median of 7.6 years, African American men, compared with non-Hispanic White men, had a statistically significant increased 10-year cumulative incidence of disease progression (59.9% vs 48.3%) and definitive treatment (54.8% vs 41.4%), but not metastasis (1.5% vs 1.4%) or prostate cancer–specific mortality (1.1% vs 1.0%).

Meaning

Among African American men with low-risk prostate cancer, active surveillance was associated with increased risk of disease progression and definitive treatment compared with non-Hispanic White men, but not increased mortality; however, longer-term follow-up is needed to better understand mortality risk.

Abstract

Importance

There is concern that African American men with low-risk prostate cancer may harbor more aggressive disease than non-Hispanic White men. Therefore, it is unclear whether active surveillance is a safe option for African American men.

Objective

To compare clinical outcomes of African American and non-Hispanic White men with low-risk prostate cancer managed with active surveillance.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study in the US Veterans Health Administration Health Care System of African American and non-Hispanic White men diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2015, and managed with active surveillance. The date of final follow-up was March 31, 2020.

Exposures

Active surveillance was defined as no definitive treatment within the first year of diagnosis and at least 1 additional surveillance biopsy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Progression to at least intermediate-risk, definitive treatment, metastasis, prostate cancer–specific mortality, and all-cause mortality.

Results

The cohort included 8726 men, including 2280 African American men (26.1%) (median age, 63.2 years) and 6446 non-Hispanic White men (73.9%) (median age, 65.5 years), and the median follow-up was 7.6 years (interquartile range, 5.7-9.9; range, 0.2-19.2). Among African American men and non-Hispanic White men, respectively, the 10-year cumulative incidence of disease progression was 59.9% vs 48.3% (difference, 11.6% [95% CI, 9.2% to 13.9%); P < .001); of receipt of definitive treatment, 54.8% vs 41.4% (difference, 13.4% [95% CI, 11.0% to 15.7%]; P < .001); of metastasis, 1.5% vs 1.4% (difference, 0.1% [95% CI, –0.4% to 0.6%]; P = .49); of prostate cancer–specific mortality, 1.1% vs 1.0% (difference, 0.1% [95% CI, –0.4% to 0.6%]; P = .82); and of all-cause mortality, 22.4% vs 23.5% (difference, 1.1% [95% CI, –0.9% to 3.1%]; P = 0.09).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this retrospective cohort study of men with low-risk prostate cancer followed up for a median of 7.6 years, African American men, compared with non-Hispanic White men, had a statistically significant increased 10-year cumulative incidence of disease progression and definitive treatment, but not metastasis or prostate cancer–specific mortality. Longer-term follow-up is needed to better assess the mortality risk.

This cohort study estimates 10-year risk for disease progression, surgery, metastasis, and cause-specific and all-cause mortality among African American men with low-risk prostate cancer managed with active surveillance.

Introduction

Active surveillance is the preferred treatment option for many men with low-risk prostate cancer to avoid or delay the adverse effects of definitive treatments. However, there is concern that African American men with early-stage cancer may harbor more aggressive disease than non-Hispanic White men and may not be good candidates for active surveillance.1,2,3 Consequently, there has been lower uptake of active surveillance in African American men,4 potentially leading to an increased burden of treatment-related adverse effects, including urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and rectal bleeding.

There have been sparse data on clinical outcomes in African American men treated with active surveillance. Published studies have generally shown that African American individuals have significantly higher rates of pathologic upgrading and treatment progression.5,6,7,8,9 However, these studies have been limited by small sample size, short follow-up, and lack of important clinical outcomes such as metastasis, prostate cancer–specific mortality, and all-cause mortality.

The US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Health Care System is an equal-access medical care system with a high proportion of African American men and an integrated medical record system. This study sought to test the hypothesis that African American men undergoing active surveillance are at a significantly higher risk of disease progression, metastases, and death from prostate cancer compared with non-Hispanic White men.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study of African American and non-Hispanic White men (hereafter, White men) with pathologically confirmed low-risk prostate cancer diagnosed between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2015, who underwent active surveillance in the US VHA. The last follow-up was the date of the event of interest, the last VHA encounter, or March 31, 2020, whichever occurred first. Active surveillance was defined as no definitive treatment within the first year of prostate cancer diagnosis and at least 1 additional biopsy after the first diagnostic biopsy. Low-risk prostate cancer was defined as a Gleason score of 6 or less, clinical tumor stage of 2A or less, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level less than 10 ng/dL.10 Patients with prior pelvic radiation, those with missing covariates (defined below), and men who were neither African American nor White were excluded. Race/ethnicity was self-reported by each veteran and based on fixed categories.

Data

All study data were extracted from the VHA’s Corporate Data Warehouse and accessed through the VHA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure.11 The VHA Corporate Data Warehouse contains electronic health records of more than 9 million veterans from the years 2000 to 2020 who receive care at approximately 1244 health care facilities, including 170 medical centers and 1074 outpatient clinics throughout the US.11 This study was reviewed and approved by the VHA San Diego Health Care System (Institutional Review Board Protocol No. 150169). This approval included a waiver of informed consent.

Outcomes

The end points of interest were disease progression, definitive treatment, metastasis, prostate cancer–specific mortality, nonprostate cancer–specific mortality, and all-cause mortality. Disease progression was defined as an increase of PSA level to 10 ng/dL or greater, a pathologic Gleason score greater than 6 (Gleason Grade Group >1), or the development of metastases. Pathologic Gleason score was identified through natural language processing of all biopsy and prostatectomy reports. A validation analysis of the natural language processing algorithm in 100 randomly selected patients with manual medical record review revealed 95% concordance with no significant difference in accuracy between African American and White men.

Definitive treatment was identified through analysis of diagnosis and procedural codes and augmented by manual medical record review. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes; ICD-9 and ICD-10 procedure codes; and Current Procedural Terminology codes were first searched in the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse to determine receipt of radiotherapy or prostatectomy. To identify care received outside of the VHA, diagnosis and procedure codes were searched in outpatient and inpatient files in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Data and Non-VHA Care Coordination Data linked to the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse. Furthermore, manual medical record review was conducted for patients with a PSA level decline of at least 50% at any time after prostate cancer diagnosis to screen for receipt of definitive treatment not identified with the previously described methods.

Identification of metastatic prostate cancer was identified through targeted medical record review. Manual review of electronic medical records was performed for patients who met any of the following criteria:

ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes for metastasis of the bone (198.5, C79.51, and C79.52) or malignant neoplasm of nonpelvic lymph nodes (196.0, 196.1, 196.2, 196.3, 196.5, 196.8, 196.9, C77.0, C77.1, C77.2, C77.3, C77.4, C77.8, and C77.9);

PSA level greater than 20 ng/dL;

Receipt of androgen deprivation therapy.

Manual review of the medical records of 100 patients who did not fulfill these criteria did not find any cases of missed metastases. Prostate cancer–specific mortality, nonprostate cancer–specific mortality, and all-cause mortality were identified through the National Death Index and manual medical record review. Because National Death Index data extended only through 2015, manual medical record review of patients recorded as deceased after 2015 in the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse was performed to determine cause of death.

Clinical outcomes were modeled as a function of African American race, age, baseline PSA level, clinical tumor stage, Charlson Comorbidity Index score,12 statin use, antiplatelet use, antihypertensive use, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, smoking status, region, zip code–level median household income and education, and year of diagnosis. Median household income and education were assigned to an individual’s zip code based on census variables from the American Community Survey.13 Clinical tumor stage was categorized as 1 and 2; median household income as less than $30 000, $30 000 to less than $60 000, $60 000 to less than $100 000, and $100 000 or more; percentage with a bachelor’s degree as less than 10%, 10% to less than 20%, 20% to less than 30%, and 30% or more; region as West, Midwest, South, and Northeast; and race as African American and White. Age and PSA levels were continuous variables. Alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, and smoking status were ascertained through the following ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes within the year prior to prostate cancer diagnosis: alcohol use disorder: 305.0, 305.00-305.03, F10.10, and F10.11; substance use disorder: 305.2-305.9, 305.20-305.23, 305.30-305.33, 305.40-305.43, 305.50-305.53, 305.60-305.63, 305.70-305.73, 305.80-305.83, 305.90-305.93, F11.10, F11.11, F12.10, F12.11, F13.10, F13.11, F14.10, F14.11, F15.10, F15.11, F16.10, F16.11, F18.10, F18.11, F19.10, F19.11, 304.0-304.9, 304.00-304.03, 304.10-304.13, 304.20-304.23, 304.30-304.33, 304.40-304.43, 304.50-304.53, 304.60-304.63, 304.70-304.73, 304.80-304.83, 304.90-304.93, F11.20, F11.21, F12.20, F12.21, F13.20, F13.21, F14.20, F14.21, F15.20, F15.21, F16.20, F16.21, F19.20, and F19.21; and tobacco use disorder: 305.1 and F17.200.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute), R Studio version 3.5.1 (The R Foundation), and Stata version 13 (StataCorp), assuming a 2-sided α of .05. Because there was no a priori designation of a primary outcome, the study design may predispose to type I error due to multiple comparisons. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis using a post hoc Bonferroni correction was performed for all clinical outcomes. There were 6 outcomes and the corrected significance threshold was 0.008. All conclusions were the same without Bonferroni correction, and the analyses reported in the article are uncorrected. The Gray test was used to evaluate differences in the cumulative incidences of clinical outcomes between African American and White men. Differences in categorical variables were assessed with χ2 tests, and differences in continuous variables were assessed with Wilcoxon tests.

Disease progression, definitive treatment, metastasis, prostate cancer–specific mortality, and nonprostate cancer–specific mortality were assessed using Fine-Gray competing risks regression. For disease progression, definitive treatment, and metastasis, death from any cause was a competing event; for prostate cancer–specific mortality, nonprostate cancer death was a competing event; and for nonprostate cancer–specific mortality, prostate cancer death was a competing event. All-cause mortality was assessed with Cox proportional hazards regression. The assumption of proportional hazards was tested using graphical inspection of Schoenfeld residuals and no violation was seen.

Among those who met inclusion criteria, 37 participants (0.4% of the total cohort) were excluded for missing data on zip code–level income or education. No other patients who met inclusion criteria were excluded for missing data.

Results

Study Population

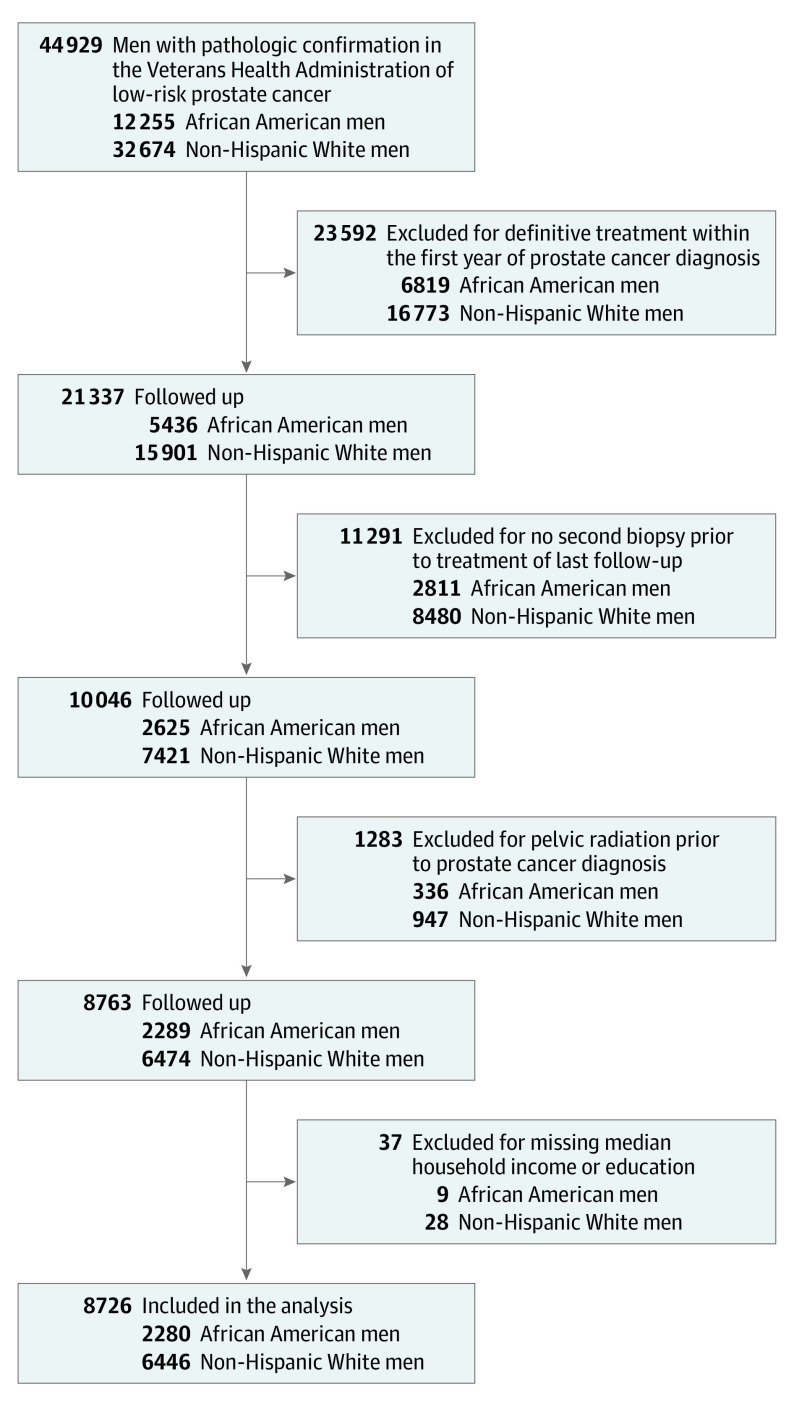

The cohort included 8726 men with low-risk prostate cancer managed with active surveillance, of which 2280 (26.1%) were African American and 6446 (73.9%) were White (Figure 1). Table 1 describes the characteristics of the cohort. African American men had a significantly lower median age at diagnosis compared with White men (63.2 vs 65.5 years) and were significantly more likely to present with a lower clinical tumor stage. Additionally, African American men were significantly more likely to use antihypertensive and antiplatelet medications, and had significantly higher rates of alcohol, substance, and tobacco use disorders. Compared with White men, African American men were significantly more likely to live in the South and in areas with lower zip code–level median household income and education levels.

Figure 1. Active Surveillance Cohort Flow Chart.

Table 1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics of African American and Non-Hispanic White Men Undergoing Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance.

| Variable | No. (%) | Absolute difference, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| African American mena | Non-Hispanic White mena | ||

| Patients, No. | 2280 | 6446 | |

| Time to follow-up, median (IQR), y | 7.4 (5.7 to 9.6) | 7.6 (5.7 to 9.9) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 63.2 (58.3 to 67.1) | 65.5 (62.3 to 69.5) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.7) |

| Prostate-specific antigen level, median (IQR), ng/dLb | 5.2 (4.2 to 6.6) | 5.2 (4.2 to 6.6) | 0 (–0.09 to 0.09) |

| Year of prostate cancer diagnosis | |||

| 2001-2005 | 137 (6.0) | 499 (7.7) | 1.7 (0.5 to 2.8) |

| 2006-2010 | 739 (32.4) | 2301 (35.7) | 3.3 (1.0 to 5.5) |

| 2011-2015 | 1404 (61.5) | 3646 (56.5) | 5.0 (2.6 to 7.3) |

| Clinical tumor stagec | |||

| 1 | 2073 (90.9) | 5471 (84.8) | 6.1 (4.6 to 7.5) |

| 2 | 207 (9.0) | 975 (15.1) | 6.1 (4.6 to 7.5) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index scored | |||

| 0 | 1815 (79.6) | 4968 (77.0) | 2.6 (0.6 to 4.5) |

| 1 | 367 (16.1) | 1242 (19.2) | 3.1 (1.3 to 4.8) |

| ≥2 | 98 (4.3) | 236 (3.6) | 0.7 (–0.2 to 1.6) |

| Regione | |||

| South | 1161 (50.9) | 2136 (33.1) | 17.8 (15.4 to 20.1) |

| Midwest | 379 (16.6) | 1556 (24.1) | 7.5 (5.6 to 9.4) |

| West | 269 (11.8) | 1596 (24.7) | 12.9 (11.2 to 14.5) |

| Northeast | 471 (20.6) | 1158 (17.9) | 2.7 (0.8 to 4.6) |

| Proportion of zip code with at least a bachelor’s degree, %f | |||

| <10 | 677 (29.6) | 1353 (20.9) | 8.7 (6.5 to 10.8) |

| 10 to <20 | 1071 (46.9) | 3177 (49.2) | 2.3 (–0.08 to 4.6) |

| 20 to <30 | 415 (18.2) | 1484 (23.0) | 4.8 (2.9 to 6.6) |

| ≥30 | 117 (5.1) | 432 (6.7) | 1.6 (0.5 to 2.6) |

| Median household income, $g | |||

| <30 000 | 394 (17.2) | 228 (3.5) | 13.7 (12.1 to 15.3) |

| 30 000 to <60 000 | 1436 (62.9) | 4271 (66.2) | 3.3 (1.0 to 5.6) |

| 60 000 to <100 000 | 420 (18.4) | 1757 (27.2) | 8.8 (6.8 to 10.7) |

| ≥100 000 | 30 (1.3) | 190 (2.9) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.2) |

| Statin use within prior year | 1,110 (48.6) | 3315 (51.4) | 2.8 (0.4 to 5.2) |

| Antiplatelet use within prior year | 517 (22.6) | 925 (14.3) | 8.3 (6.4 to 10.2) |

| Antihypertensive use within prior year | 1707 (74.8) | 4091 (63.4) | 11.4 (9.2 to 13.5) |

| Cigarette use within prior yearh | 498 (21.8) | 1157 (17.9) | 3.9 (1.9 to 5.8) |

| Alcohol use disorder within prior yearh | 132 (5.7) | 277 (4.3) | 1.4 (0.3 to 2.5) |

| Substance use disorder within prior yearh | 603 (26.4) | 1225 (19.0) | 7.4 (5.3 to 9.4) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Self-reported race.

Prostate-specific antigen level less than 10 ng/dL is required to be considered low risk.

Clinical tumor stage 1: cancer is nonpalpable and does not extend beyond prostate; and stage 2: cancer is palpable and does not extend beyond prostate.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index measures the burden of comorbid conditions. It is calculated based on diagnoses present in the year prior to prostate cancer diagnosis. Each condition is assigned a score of 1, 2, 3, or 6. A score of 0 indicates that a patient did not have any medical comorbidities in the year prior to prostate cancer diagnosis, 1 indicates 1 mild comorbid condition, and 2 or greater indicates that the patient had at least 1 severe comorbid condition or multiple mild conditions. The range for all patients in the study was 0 to 10 (non-Hispanic White men: 0-7; African American men: 0-10).

Based on US Census Bureau regions.

Percentage of zip code with an educational attainment level of at least a bachelor’s degree.

Median household income of the zip code of residence.

Ascertained through International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes.

The median number of PSA tests was 12 (interquartile range [IQR], 8-17) among African American participants, and 12 (IQR, 8-17) among White participants (P = .34). The median number of biopsies was 2 (IQR, 2-3) among African American participants and 2 (IQR, 2-3) among White participants; this difference was statistically significant (P = .02). The median time to second biopsy was not significantly different between African American and White men (both 3.5 years, P = .87).

The median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 7.6 years (IQR, 5.7-9.9; range, 0.2-19.2), with no significant difference in the length of follow-up between African American men (7.4 years; IQR, 5.7-9.6; range, 0.2-18.2) and White men (7.6 years; IQR, 5.7-9.9; range, 0.2-19.2) (P = .14) (Table 1). A total of 2081 patients were followed up for at least 10 years (499 African American men [21.9%] and 1582 White men [24.5%]).

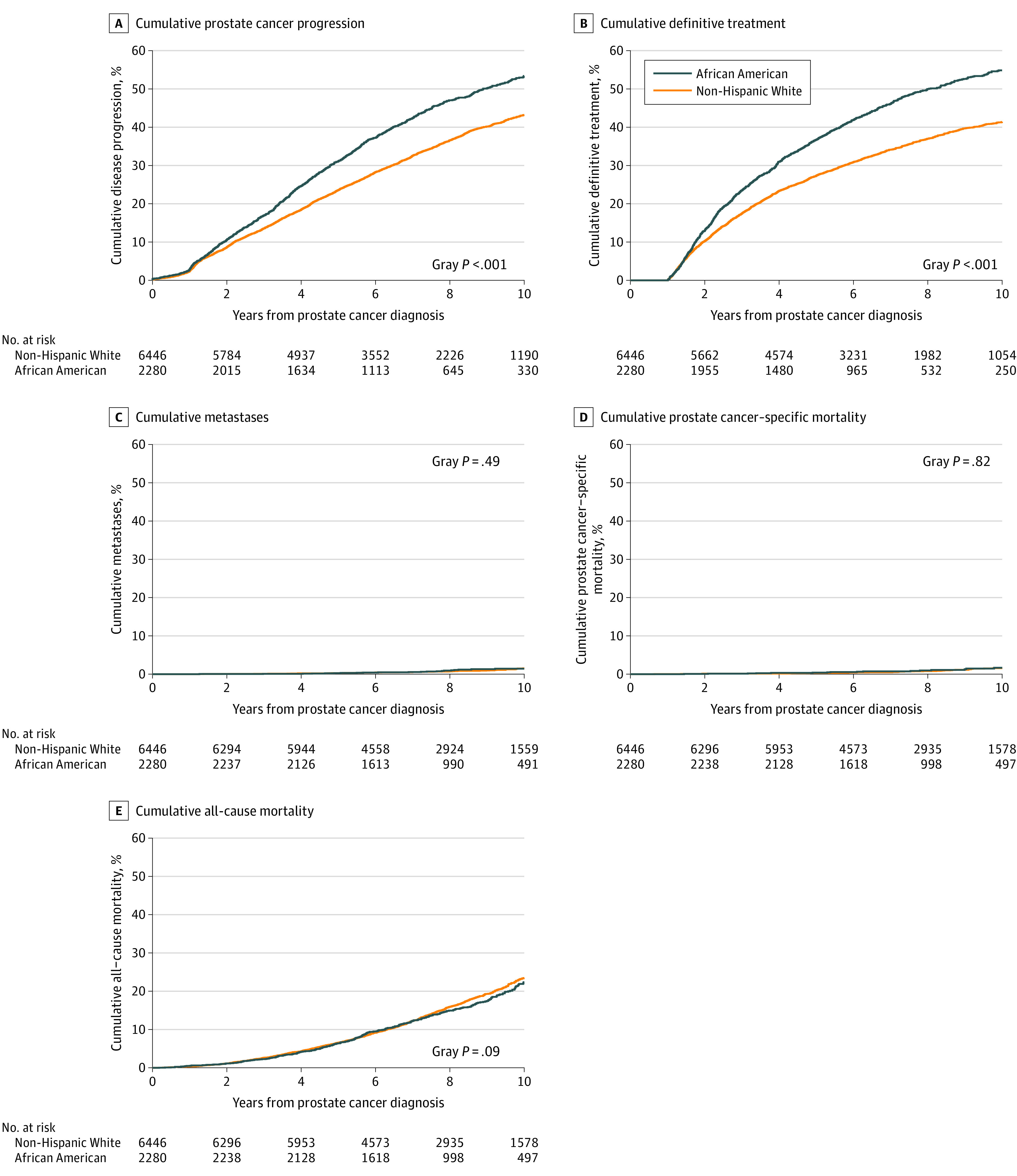

Disease Progression

During the study follow-up, 3766 patients experienced disease progression (1156 African American and 2610 White men). The cumulative incidence of disease progression at 10 years was 59.9% for African American and 48.3% for White men (Table 2 and Figure 2A; difference, 11.6% [95% CI, 9.2%-13.9%); Gray P < .001). In the multivariable competing risks regression, African American men were significantly more likely to experience disease progression (subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR], 1.3 [95% CI, 1.2-1.4]; P < .001). African American men were significantly more likely to experience a PSA level of 10 ng/dL or greater (SHR, 1.3 [95% CI, 1.1-1.5]; P < .001) and significantly more likely to experience a Gleason score greater than 6 (SHR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.2-1.5]; P < .001) after diagnosis.

Table 2. Outcomes for African American and Non-Hispanic White Men Undergoing Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance.

| End point | 10-y Cumulative incidence | Subdistribution hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Absolute difference, % (95% CI) | |||

| African American mena (n = 2280) | Non-Hispanic White mena (n = 6446) | |||

| Disease progressionb | 1156 (59.9) | 2610 (48.3) | 11.6 (9.2 to 13.9) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) |

| Definitive treatmentc | 1137 (54.8) | 2438 (41.4) | 13.4 (11.0 to 15.7) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) |

| Metastasisd | 30 (1.5) | 79 (1.4) | 0.1 (–0.4 to 0.6) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.9) |

| Prostate cancer–specific mortality | 22 (1.1) | 65 (1.0) | 0.1 (–0.4 to 0.6) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.1) |

| Nonprostate cancer–specific mortality | 387 (21.2) | 1265 (22.4) | 1.2 (–0.7 to 3.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

| All-cause mortality | 409 (22.4) | 1330 (23.5) | 1.1 (–0.9 to 3.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1)e |

Self-reported race.

Disease progression was defined as an increase in prostate-specific antigen level greater than 10 ng/dL, pathologic Gleason score greater than 6 (Gleason Grade Group >1), or development of metastases at any point during follow-up.

Receipt of radiation therapy or prostatectomy.

Prostate cancer spread to lymph nodes outside the pelvis or metastases in bones or other organs.

Hazard ratio (95% CI).

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidences of Selected Outcomes.

A, The median years of follow-up were 5.82 (interquartile range [IQR], 3.66-8.47) for African American men and 6.50 (IQR, 4.22-9.08) for non-Hispanic White men (Wilcoxon P < .001). B, The median years of follow-up were 5.37 (IQR, 2.85-7.32) for African American men and 6.02 (IQR, 3.48-8.62) for non-Hispanic White men (Wilcoxon P < .001). C, The median years of follow-up were 7.45 (IQR, 5.66-9.58) for African American men and 7.62 (IQR, 5.67-9.91) for non-Hispanic White men (Wilcoxon P = .11). D, The median years of follow-up were 7.48 (IQR, 5.67-9.62) for African American men and 7.62 (IQR, 5.69-9.95) for non-Hispanic White men (Wilcoxon P = .14). E, The median years of follow-up were 7.48 (IQR, 5.67-9.62) for African American men and 7.62 (IQR, 5.69-9.95) for non-Hispanic White men (Wilcoxon P = .12).

Definitive Treatment

A total of 3575 patients received definitive treatment (1137 African American and 2438 White men). The cumulative incidence of definitive treatment at 10 years was 54.8% for African American men and 41.4% for White men (Table 2 and Figure 2B; difference, 13.4% [95% CI, 11.0%-15.7%]; Gray P < .001). In the multivariable competing risks regression, African American men were significantly more likely to receive definitive treatment (SHR, 1.3 [95% CI, 1.2-1.4]; P < .001).

Metastasis

During the study follow-up, 109 men experienced metastatic prostate cancer, including 30 African American and 79 White men. The cumulative incidence of metastasis at 10 years was 1.5% for African American men and 1.4% for White men (Table 2 and Figure 2C; difference, 0.1% [95% CI, –0.4% to 0.6%]; Gray P = .49). In the multivariable competing risks regression, African American men were not significantly more likely to experience metastasis (SHR, 1.2 [95% CI, 0.8-1.9]; P = .48).

Mortality

A total of 87 patients experienced death from prostate cancer, including 22 African American and 65 White men. The cumulative incidence of prostate cancer–specific mortality at 10 years was 1.1% for African American men and 1.0% for White men (Table 2 and Figure 2D; difference, 0.1% [95% CI, –0.4% to 0.6%]; Gray P = .82). In the multivariable competing risks regression, African American men were not significantly more likely to experience prostate cancer–specific mortality (SHR, 1.2 [95% CI, 0.7-2.1]; P = .82). During the study follow-up, a total of 1652 men experienced nonprostate cancer death, including 387 African American men and 1265 White men. The cumulative incidence of nonprostate cancer death at 10 years was 21.2% for African American men and 22.4% for White men (Table 2; difference, 1.2% [95% CI, –0.7% to 3.2%]; Gray P = .14).

In the multivariable competing risks regression, African American men were not significantly more likely to experience nonprostate cancer mortality (SHR, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.9-1.1]; P = .70). A total of 1739 patients experienced death from any cause, including 409 African American men and 1330 White men. The cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality at 10 years was 22.4% for African American men and 23.5% for White men (Table 2 and Figure 2E; difference, 1.1% [95% CI, –0.9% to 3.1%]; Gray P = .09). In the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression, African American men were not significantly more likely to experience all-cause mortality (SHR, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.9-1.1]; P = .85).

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of 8726 men with low-risk prostate cancer managed with active surveillance and followed up for a median of 7.6 years, African American men, compared with White men, had a statistically significant increased 10-year cumulative incidence of disease progression and definitive treatment, but not metastasis or prostate cancer–specific mortality. Longer-term follow-up is needed to better assess the mortality risk.

Active surveillance is the preferred treatment option for many men with low-risk prostate cancer to avoid or delay the adverse effects of definitive treatments.14 Major surveillance cohort studies have consistently shown favorable mortality outcomes with 10-year cancer-specific survival ranging from 97% to 100%.15,16,17,18,19,20,21 However, these studies included very few African American men. There are several reasons to question the generalizability of previously published studies performed in predominantly White patients to the African American population.22 First, population-based studies indicate that African American men are 2.4 times as likely to die from prostate cancer, compared with White men, due to increased incidence and poorer survival after diagnosis.23,24,25,26 Second, multiple studies of African American men undergoing immediate radical prostatectomy have shown significantly higher rates of upgrading and adverse pathology.1,27,28 Third, most published studies on clinical outcomes in African American men have generally shown significantly increased progression and need for treatment.5,6,7,8,9,29 Consequently, there has been slower uptake of active surveillance in African American men compared with White men.4,30

This study included 2280 African American men from VHA medical centers across the US; to our knowledge, this represents the largest sample of African American participants in an active surveillance study. The results are consistent with most studies that show significantly increased rates of definitive treatment and disease progression in African American men compared with White men. These findings may have important implications. First, several recent studies have suggested equal outcomes for African American and White men when managed in equal-access settings.23,31 While improving access to care is undoubtedly beneficial, the results of this study suggest that only improving access is unlikely to completely ameliorate the disparity in pathologic outcomes. These data, in conjunction with the lower age at diagnosis and higher overall incidence of prostate cancer in African American men, continue to point to some underlying difference in the biology of the disease. Second, because African American men are significantly more likely to experience disease progression, improved patient selection and close follow-up are critical to maintaining favorable outcomes. Whether protocols developed in predominantly White cohorts are appropriate for African American men remain to be evaluated.

In contrast to the pathologic end points, the present study did not find any significantly increased risk of metastases, prostate cancer–specific mortality, or all-cause mortality in African American men. Furthermore, the estimates of metastases and prostate cancer–specific mortality for African American men in this cohort are broadly in line with results from prospective cohort studies composed of predominantly White men,32,33,34 suggesting that African American men should not be excluded from active surveillance protocols.

The discrepancy between pathologic outcomes and longer-term end points merits further consideration. Most progression events were either upgrading to Gleason score 7 disease or to a PSA level greater than 10 ng/dL where metastases are relatively rare and active surveillance could still be considered.11,14 It is possible that when carefully observed and promptly treated, the small increased risk of local disease progression may not substantially affect the risk of metastases. However, a median follow-up of 7.6 years is still a relatively short interval for the development of metastases and death from low-risk prostate cancer. The duration of follow-up may not be sufficient to detect differences in metastases and mortality. Point estimates for metastasis and prostate cancer–specific mortality were in the direction of worse outcomes for African American men. Longer-term follow-up is needed to better assess the metastasis and mortality risk.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as a retrospective cohort study of active surveillance practiced in the VHA community, there was no specific follow-up protocol for active surveillance. To differentiate between active surveillance and watchful waiting, patients were required to have at least 1 repeat biopsy. However, subsequent PSA, biopsy, and treatment decisions were made at the discretion of the treating physicians and their patients. There were no substantial differences in the frequency of PSA or repeat biopsy that would affect results, but differential management by race cannot be ruled out.

Second, there was no prespecified method or timing of clinical ascertainment of metastases.

Third, manual medical record review was used to determine patients who developed metastases. It is possible that some patients with metastases were not identified. However, there was no evidence these errors would have varied by African American status. The similarity in long-term outcomes is also corroborated by prostate cancer–specific mortality, although cause of death ascertainment has limitations as well.35

Fourth, all patients received their care through the VHA, which may limit the generalizability of these findings. This health care setting may reduce barriers to care that still exist for African American men in other health care settings.

Fifth, there were several end points in this study, which raises some concern for type I error due to multiple comparisons. Further research should seek to validate these findings.

Conclusions

In this retrospective cohort study of men with low-risk prostate cancer followed up for a median of 7.6 years, African American men, compared with non-Hispanic White men, had a statistically significant increased 10-year cumulative incidence of disease progression and definitive treatment, but not metastasis or prostate cancer–specific mortality. Longer-term follow-up is needed to better assess the mortality risk.

References

- 1.Sundi D, Ross AE, Humphreys EB, et al. African American men with very low-risk prostate cancer exhibit adverse oncologic outcomes after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(24):2991-2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahal BA, Alshalalfa M, Spratt DE, Davicioni E, Zhao SG, Feng FY, et al. Prostate cancer genomic-risk differences between African American and White men across Gleason Scores. Eur Urol. 2019;75(6):1038-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahal BA, Berman RA, Taplin ME, Huang FW. Prostate cancer-specific mortality across Gleason scores in black vs nonblack men. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2479-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahal BA, Butler S, Franco I, et al. Use of active surveillance or watchful waiting for low-risk prostate cancer and management trends across risk groups in the United States, 2010-2015. JAMA. 2019;321(7):704-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odom BD, Mir MC, Hughes S, et al. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer in African American men. Urology. 2014;83(2):364-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iremashvili V, Soloway MS, Rosenberg DL, Manoharan M. Clinical and demographic characteristics associated with prostate cancer progression in patients on active surveillance. J Urol. 2012;187(5):1594-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abern MR, Bassett MR, Tsivian M, et al. Race is associated with discontinuation of active surveillance of low-risk prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16(1):85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundi D, Faisal FA, Trock BJ, et al. Reclassification rates are higher among African American men than Caucasians on active surveillance. Urology. 2015;85(1):155-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis JW, Ward JF III, Pettaway CA, et al. Disease reclassification risk with stringent criteria and frequent monitoring in men with favourable-risk prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. BJU Int. 2016;118(1):68-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Accessed January 7, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf

- 11.Department of Veterans Affairs About VHA. Accessed January 7, 2020. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- 12.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coogan PF, Castro-Webb N, Yu J, O’Connor GT, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Neighborhood and individual socioeconomic status and asthma incidence in African American women. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(1):113-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN guidelines for patients: prostate cancer. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/prostate/files/assets/common/downloads/files/prostate.pdf

- 15.Carter HB, Kettermann A, Warlick C, et al. Expectant management of prostate cancer with curative intent. J Urol. 2007;178(6):2359-2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tosoian JJ, Trock BJ, Landis P, et al. Active surveillance program for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(16):2185-2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, Nam R, Mamedov A, Loblaw A. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):126-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van As NJ, Norman AR, Thomas K, et al. Predicting the probability of deferred radical treatment for localised prostate cancer managed by active surveillance. Eur Urol. 2008;54(6):1297-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berglund RK, Masterson TA, Vora KC, Eggener SE, Eastham JA, Guillonneau BD. Pathological upgrading and up staging with immediate repeat biopsy in patients eligible for active surveillance. J Urol. 2008;180(5):1964-1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soloway MS, Soloway CT, Williams S, Ayyathurai R, Kava B, Manoharan M. Active surveillance: a reasonable management alternative for patients with prostate cancer: the Miami experience. BJU Int. 2008;101(2):165-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soloway MS, Soloway CT, Eldefrawy A, Acosta K, Kava B, Manoharan M. Careful selection and close monitoring of low-risk prostate cancer patients on active surveillance minimizes the need for treatment. Eur Urol. 2010;58(6):831-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClelland S III, Mitin T. The danger of applying the ProtecT Trial to minority populations. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA, et al. Association of black race with prostate cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):975-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):290-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele CB, Li J, Huang B, Weir HK. Prostate cancer survival in the United States by race and stage (2001-2009). Cancer. 2017;123(suppl 24):5160-5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2015. Accessed January 15, 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2015/

- 27.Katz JE, Chinea FM, Patel VN, et al. Disparities in Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic Black men with low-risk prostate cancer and eligible for active surveillance. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21(4):533-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurice MJ, Sundi D, Schaeffer EM, Abouassaly R. Risk of pathological upgrading and up staging among men with low risk prostate cancer varies by race. J Urol. 2017;197(3, pt 1):627-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gökce MI, Sundi D, Schaeffer E, Pettaway C. Is active surveillance a suitable option for African American men with prostate cancer? a systemic literature review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20(2):127-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler S, Muralidhar V, Chavez J, et al. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer in Black patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):2070-2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Racial equity among African American and non-Hispanic White men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(1):E305. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tosoian JJ, Mamawala M, Epstein JI, et al. Intermediate and longer-term outcomes from a prospective active-surveillance program for favorable-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(30):3379-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klotz L, Vesprini D, Sethukavalan P, et al. Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(3):272-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. ; ProtecT Study Group . 10-Year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moghanaki D, Howard LE, De Hoedt A, et al. Validity of the National Death Index to ascertain the date and cause of death in men having undergone prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019;22(4):633-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]