Abstract

Cervical insufficiency is an important cause of preterm birth, which leads to severe newborn complications. Standard treatment for cervical insufficiency is cerclage, which has variable success rates, resulting in a clinical need for alternative treatments. Our objective was to develop an ex vivo model of softened cervical tissue to study an injectable silk-based hydrogel as a novel alternative treatment for cervical insufficiency. Cervical tissue from non-pregnant women was enzymatically treated and characterized to determine tissue hydration, collagen organization, and mechanical properties via unconfined compression. Enzymatic treatment led to an 86 ± 7.9% decrease in modulus which correlated to a decrease in collagen organization as observed by differences in collagen birefringence. The softened tissue was injected with a crosslinked silk-hyaluronic acid composite hydrogel. After injection, the mechanical properties and volume increase of the hydrogel-treated tissue were measured resulting in a 54 ± 16% volume increase with minimal effect on tissue mechanical properties. In addition, cervical fibroblasts on silk-hyaluronic acid hydrogels remained viable and exhibited increased proliferation and metabolic activity over 5 days. Overall, this study developed an ex vivo pregnant-like human tissue model to assess cervical augmentation and showed the potential of silk-based hydrogels as an alternative treatment for cervical insufficiency.

Keywords: cervix, cervical insufficiency, preterm birth, hydrogel, silk

1. INTRODUCTION

Preterm birth, delivery at less than 37 weeks’ gestational age, is the leading cause of neonatal mortality and a major contributor to developmental issues and physiological morbidities.1-3 Cervical insufficiency (CI), which is often preceded by cervical shortening, is a significant cause of preterm birth and untreated CI can lead to a previable or a periviable birth.4,5 Standard treatment options for CI and cervical shortening include cerclage, which is a stitch placed either vaginally or abdominally to support the cervix, and progesterone supplementation, which maintains myometrial quiescence.6-8 However, cerclage can be associated with surgical risks including cervical tissue injury.9 Also, despite appropriate treatment, many women with CI and cervical shortening will experience a preterm birth, providing a strong clinical need for alternative treatment options.

The use of injectable silk-based hydrogels to augment cervical tissue is a novel and promising alternative treatment for cervical dysfunction.10-12 Silk-based biomaterials are biocompatible, biodegradable, and have tunable mechanical properties.13 We recently reported on a silk hydrogel, formulated by crosslinking tyrosine residues via horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and hydrogen peroxide, for cervical augmentation.10,14 These enzymatically crosslinked hydrogels are easily injectable, have similar mechanical properties to cervical tissue, and can form a solid gel without the use of exogenous chemicals.10 In addition, the enzymatic reaction allows for a simple process to formulate composite hydrogels that have further versatility. In a recent report, silk and tyramine-substituted hyaluronic acid (HA) were combined to form composite hydrogels that exhibit reduced stiffening and tunable degradation.15 Composite silk-HA hydrogels could be relevant for cervical treatment. HA is a known constituent of cervical tissue;16 HA regulates cervical tissue composition;17 and HA is an important component of cervical ripening,18 which is the phase during pregnancy that occurs weeks leading up to childbirth, in which cervical tissue continues to soften prior to dilation. Thus, composite silk-HA hydrogels may have improved properties for cervical augmentation compared with hydrogels composed of silk alone.

A cervical tissue model for augmentation with silk-based hydrogels is not readily available. Ideally, cervical tissue from pregnant individuals would be used. However tissue from pregnancy is difficult to obtain. Our previous studies used tissue from non-pregnant women.10,12 But pregnancy causes extensive remodeling of the cervical extracellular matrix (ECM) resulting in tissue softening.19 The ECM of cervical tissue is primarily composed of water, collagen, proteoglycans, hyaluronic acid, and elastin with the collagen network providing the majority of the tissue’s mechanical strength.20 Cervical remodeling increases tissue hydration and disrupts the collagen network causing a decrease in stiffness.19-22 Thus, it is necessary to study injectable silk-based hydrogels in tissue that mimics the mechanical and structural properties of cervical tissue from pregnancy.

The goal of this study was to develop an ex vivo pregnant-like tissue model from non-pregnant cervical tissue specimens and test the model for cervical augmentation with silk-HA hydrogels. An ideal tissue model would mimic pregnant tissue mechanical properties thus facilitating in vitro assessment of cervical augmentation with an injectable hydrogel. Cervical specimens from non-pregnant individuals were enzymatically treated and assessed for hydration, collagen content and organization, and mechanical properties. We hypothesized that the enzyme treatment would degrade collagen and disrupt collagen organization causing a decrease in stiffness. The pregnant-like tissue model was used to assess cervical augmentation with silk-HA composite hydrogels and determine the effect on overall tissue mechanics. Cytotoxicity of cervical fibroblasts on silk-HA hydrogels was also assessed. Overall, we were able to produce a more mechanically relevant pregnant-like tissue model and show the promise of silk-HA hydrogels for cervical augmentation.

2. METHODS

2.1. Cervical Tissue Preparation and Treatment

Cervical tissue specimens were collected from non-pregnant patients after hysterectomy for benign indications (IRB#8315, approved 07/17/2007). Specimens were stored at −80°C until analysis and thawed overnight in 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C. Specimens were sectioned utilizing a modified customized sectioning device19 and a 10 mm biopsy punch resulting in cylindrical samples with a height of 8 mm. Samples were equilibrated at 37°C in 1x PBS for 2 hours prior to testing.

Cervical tissue samples were incubated in a 2 mg/mL (0.4 U/mL) solution of collagenase B (from Clostridium histolyticum, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C for 2 hours. Initially and after 1 hour, 60 μL of the solution was injected into the samples with a 29G, ½” needle. After 2 hours of incubation, samples were washed with 10 mM sodium EDTA for 15 minutes to halt collagenase activity. Samples were either utilized for ex vivo augmentation, fixed in 10% phosphate buffered formalin to determine collagen organization, or flash frozen and stored at −80°C to determine tissue hydration and collagen content.

2.2. Tissue Hydration and Collagen Characterization

Frozen samples (~20 mg) were homogenized using a Bessman tissue pulverizer and weighed (wet weight). The pulverized tissue was then lyophilized and re-weighed (dry weight). Percent water was calculated by normalizing the difference between the wet and dry weights by the wet weight.

Collagen concentration was determined by analyzing the hydroxyproline content as previously described19 and calculated with a mass ratio of 7.46:1 (collagen:hydroxyproline). Percent collagen was determined by normalizing collagen concentration to dry weight.

To characterize the collagen organization, native and enzyme-treated samples were fixed in 10% phosphate buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Samples were then sectioned and stained with Picrosirius red at the Tufts Animal Histology Core for polarized microscopy. The birefringence of Picrosirius red stained samples were visualized with a Nikon Eclipse E600 Polarizing Optical Microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) and captured using Spot 5.2 Advanced Image Analysis Software. For each sample, 3 sections were imaged under polarized light (A ⊥ P) using a 10x objective in 2 random locations for a total of 6 images per sample. Collagen fiber thickness and organization were assessed by quantifying the hue frequency of the polarized images using ImageJ software,23 where longer wavelengths (i.e. red and orange) signifies thicker fibers that are more tightly packed and better aligned.24 For each image, the hue, saturation, and brightness components were separated and a histogram of the hue component was obtained. The histogram consisted of 0-255 colors defined as red (1-8 and 229-255), orange (9-37), yellow (38-50), and green (51-127).25 Results are shown as the sum of the number of pixels within each hue range normalized by the total number of pixels.

2.3. Preparation of Silk-HA Hydrogels and Tissue Injection

Silk fibroin protein was extracted as previously described.13 In brief, Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons were placed in a boiling sodium carbonate solution for 60 minutes. After a series of washing, the resulting fibers were dissolved in lithium bromide and dialyzed against water for 3 days. Hydrogels were prepared by combining silk and 5.5% tyramine-substituted HA as previously described15 with final concentrations specified in Table 1. Crosslinking was initiated by combining the polymer solution with 10 U/mL of horseradish peroxidase (HRP), type VI (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 1.63 mM of hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogels were allowed to set at 37°C for 2-3 hours. For cytotoxicity studies, materials were filter sterilized prior to gelation.

Table 1.

Silk hydrogel formulations.

| Sample name | Silk concentration [mg/mL] |

HAa) concentration [mg/mL] |

|---|---|---|

| Silk | 50 | 0 |

| Silk Low-HA | 50 | 1 |

| Silk Med-HA | 50 | 1.75 |

| Silk High-HA | 50 | 2.5 |

HA, hyaluronic acid

For cervical tissue augmentation, Silk Med-HA hydrogels (Table 1) were allowed to gel for 2-3 hours at 37°C in 1 mL syringes fitted with a 21G, thin-wall, 1” needle. After enzymatic treatment of the cervical tissue, 300 μL of the hydrogel were injected. Volumetric bulking was calculated using diameter and height measurements of the cervical specimens.10 Samples were fixed in formalin, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and visualized with a BZ-X700 Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence Corp., Itasca, IL) to evaluate the location of the hydrogel within the cervical tissue.

2.4. Mechanical analysis

Mechanical properties were determined with unconfined compression utilizing a RSA3 dynamic mechanical analyzer (TA instruments, New Castle, DE) fitted with an immersion chamber filled with 1x PBS for native, enzyme-treated, and hydrogel-treated cervical tissue. Tissue specimens were loaded between stainless steel parallel plates, placed under a pre-load force of 2 g, and subjected to 2 load-unload cycles at 1 mm/min to 20% strain. A final load cycle at the same rate to 10% strain was performed and modulus was calculated between 1-5% strain.

2.5. Cytotoxicity

Hydrogel cytotoxicity was determined in vitro by evaluating the viability, proliferation, and metabolic activity of cervical fibroblasts up to 5 days in culture. Primary cervical fibroblasts were isolated as previously described26 (IRB#8315) and cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. At passages 4-5, 10,000 cells/cm2 were plated on top of a thin layer of sterile silk-HA hydrogel or tissue culture plastic (TCP) as a control. Viability was determined via LIVE/DEAD® Cell Imaging Kit (R37601, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and imaged with a BZ-X700 Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence Corp., Itasca, IL). Metabolic activity was determined by measuring the fluorescence (560/590 nm, excitation/emission) of a 1x AlamarBlue (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) solution after incubating with samples for 4 hours at 37°C. After analysis, samples were cultured with standard cell media for continued analysis, after washing samples 3x with 1x PBS for 5 minutes. Proliferation was determined using a Quant-iT™ PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) after thawing samples that were flash frozen in 1x TE buffer. Metabolic activity and proliferation were measured as per manufacturers’ instructions using a SpectraMax M2 multi-mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as averages ± standard deviations, unless otherwise noted. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Significance for cervical tissue hydration (N=3, p≤0.01), collagen content (N=3, p≤0.01), and volumetric bulking (N=5, p≤0.01) were determined by unpaired t-tests. Significance of the hue frequency of cervical tissue under polarized light (N=3, p≤0.01) was determined utilizing two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison tests. For mechanical analysis (N=4, p≤0.05) and cytotoxicity (N=6, p≤0.05), two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison tests were used to determine statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characterization of Native and Enzyme-treated Cervical Tissue

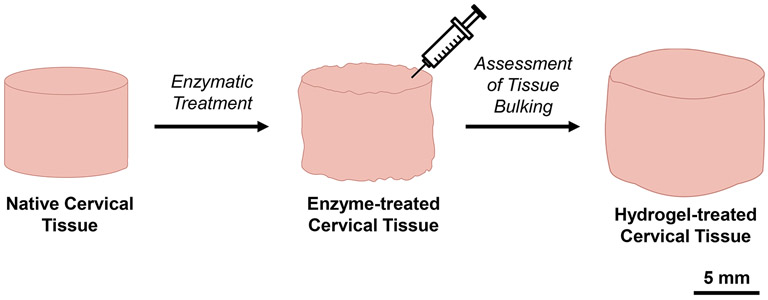

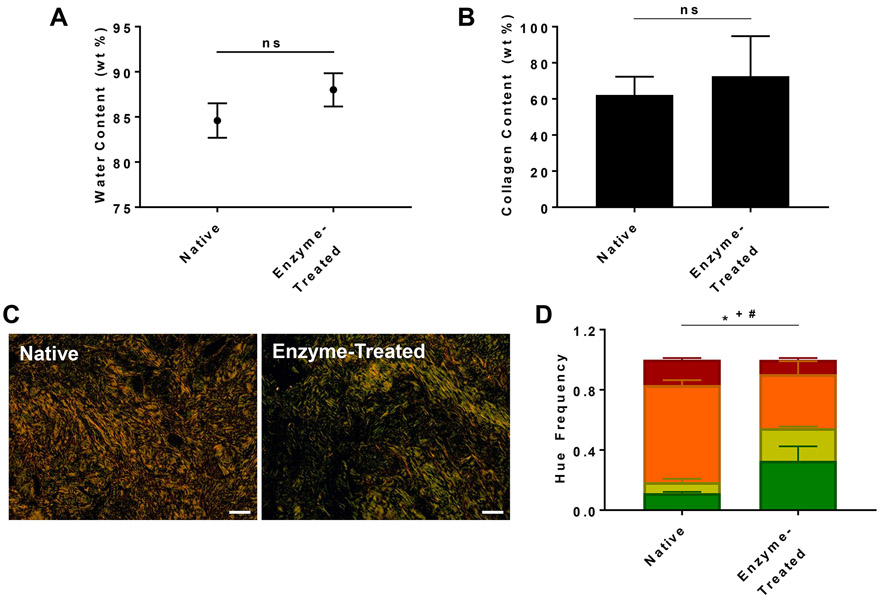

The process of developing a pregnant-like tissue model is shown in Figure 1. Cervical specimens from non-pregnant individuals were treated with collagenase. Hydration, collagen content, and birefringence were analyzed for cervical tissue samples before and after collagenase treatment (Figure 2). There was no significant difference between native and enzyme-treated samples for both hydration (Figure 2A) and collagen content (Figure 2B). To further investigate the effect of enzymatic treatment, collagen organization was analyzed through polarized microscopy. Under polarized light, Picrosirius red stained collagen fibers in cervical tissue are birefringent and have distinct coloration depending on their fiber size and organization. In general, tightly packed, aligned, thick fibers have longer wavelengths resulting in more red and orange hues. A decrease in wavelength towards yellow and green signifies collagen fibers that are less organized and thinner.24,25 The enzyme-treated tissue had a significantly higher frequency of green and yellow hues and decreased frequency of orange hues compared to native tissue (Figure 2C and 2D), demonstrating that collagenase treatment effects collagen fiber size and organization without causing differences in hydration and collagen content.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview. The process of developing a pregnant-like tissue model via enzymatically treating native cervical tissue and assessing the efficacy of an injectable hydrogel to augment softened tissue. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Figure 2.

Characterization of native and enzyme-treated cervical tissue. A) tissue water content; B) percent collagen of tissue; C) polarized microscopy image of tissue; D) hue frequency analysis of polarized images. Scale bar = 100 μm; ns = not significant; * = p≤0.01 for orange hue; + = p≤0.01 for yellow hue; # = p≤0.01 for green hue.

3.2. Mechanical Analysis of Cervical Tissue

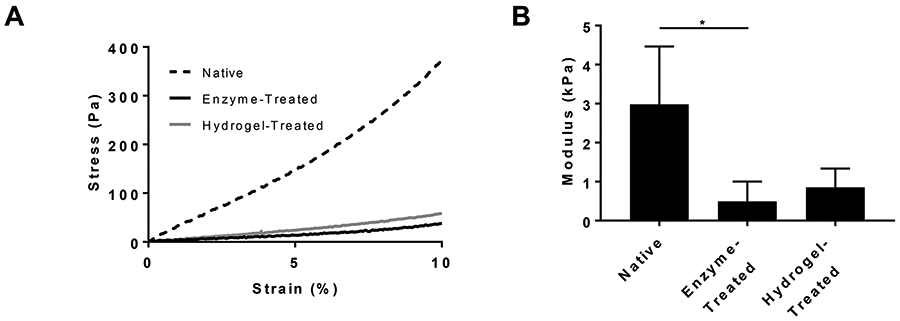

The mechanical properties of native, enzyme-treated, and hydrogel-treated cervical tissue were determined through unconfined compression (Figure 3). Native and enzyme-treated tissue had moduli of 3.0 ± 1.5 kPa and 0.49 ± 0.51 kPa, respectively. The modulus of the enzyme-treated tissue decreased significantly by 86 ± 7.9%. Upon injecting 300 μL of the Silk Med-HA hydrogel, the modulus of the hydrogel-treated cervical tissue was 0.85 ± 0.48 kPa, which is slightly, but not significantly higher than that of the enzyme-treated tissue.

Figure 3.

Mechanical characterization of native, enzyme-treated, and hydrogel-treated cervical tissue. A) representative stress-strain profiles; B) modulus. *=p≤0.05

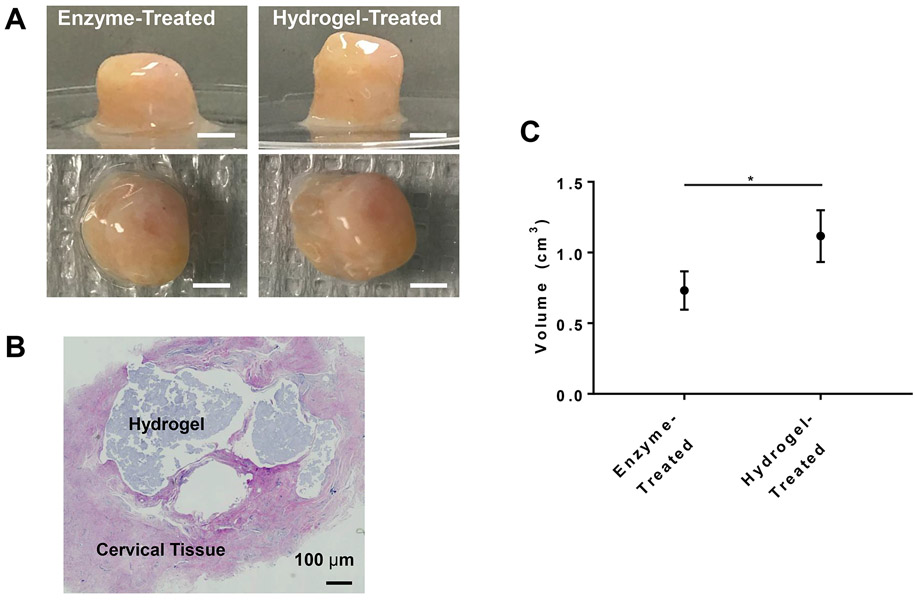

3.3. Ex Vivo Cervical Tissue Augmentation

Tissue augmentation after hydrogel injection was analyzed through volumetric measurements and histology (Figure 4). After injecting 300 μL of Silk Med-HA hydrogels into enzyme-treated cervical tissue, there was significant increase in volume from 0.73 ± 0.14 cm3 to 1.1 ± 0.18 cm3, resulting in a 54 ± 16% volumetric increase (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

In vitro analysis of cervical tissue augmentation. A) Cervical tissue images before and after hydrogel injection. Scale bar = 5 mm; B) H&E staining of injected tissue confirming incorporation and localization; C) volumetric measurements. * = p≤0.01

3.4. Cytotoxicity

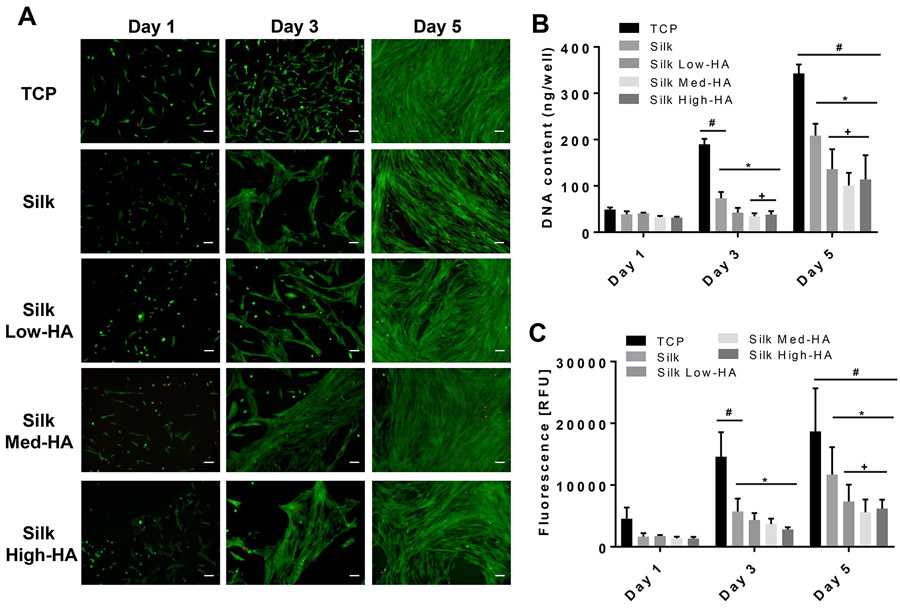

Viability, proliferation, and metabolic activity of primary cervical fibroblasts seeded on hydrogels were determined to assess hydrogel cytotoxicity (Figure 5). Cervical fibroblasts remained viable with limited cell death over 5 days of culture (Figure 5A). All hydrogels supported fibroblast growth, as exhibited through increased DNA content and metabolic activity on day 5 as compared to day 1 (Figure 5B and 5C). However, fibroblasts on the hydrogels had significantly less DNA content and metabolic activity compared to that of TCP controls. In addition, the inclusion of HA to the hydrogels further reduced proliferation and metabolic activity on day 5 when compared to silk only hydrogels.

Figure 5.

In vitro 2D cervical fibroblast response. A) Images of LIVE/DEAD stain of cervical cells on hydrogels; B) DNA quantification; C) metabolic activity measurements. Scale bar = 100 μm. * = p≤0.05 compared to TCP; + = p≤0.05 compared to silk; # = p≤0.05 compared to day 1. RFU, relative fluorescence units; TCP, tissue culture plastic; HA, hyaluronic acid.

4. DISCUSSION

An ex vivo pregnant-like tissue model was developed to investigate the potential of an injectable hydrogel as an alternative treatment for preterm birth due to cervical insufficiency. Injection of a composite silk-HA hydrogel into softened cervical tissue resulted in significant volume increase without excessive stiffening. Also, the composite silk-HA surface was not cytotoxic for cervical fibroblasts. Together, these results show that the composite silk-HA hydrogel is a promising prototype for cervical augmentation during pregnancy.

To test an injectable hydrogel in a relevant tissue model, it was necessary to soften the collagenous ECM of cervical tissue. The mechanical properties of cervical tissue primarily arise from its collagen content and organization.20 Collagen makes up 54-77% of the cervical tissue’s dry weight20 and is arranged in tightly packed bundles of fibers that are preferentially-aligned.22,27,28 Pregnancy is associated with increased collagen extractability22,29 and increased collagen disorganization where collagen bundles appear more dispersed compared to non-pregnant tissue.22,30,31 We hypothesized that pregnant-like tissue could be obtained from non-pregnant tissue by disrupting the collagen network using collagenase treatment.32 Overall, the enzymatic treatment altered collagen organization without decreasing collagen content. The decrease in collagen organization was qualitatively observed through a color shift in the birefringence of Picrosirius red stained samples. The differences between the collagen organization of pregnant and non-pregnant cervical tissue using Picrosirius red have been previously reported, with the total amount of birefringence being less in pregnant tissue than that of non-pregnant tissue.22,30 In our tissue model, there were limited differences in the overall birefringence. There were, however, significant shifts in color, which signifies a decrease in collagen organization.24,25 Further work is needed quantify the differences in tissue microstructure between the cervix in pregnancy and our cervical-like tissue model.

Enzymatic treatment correlated with significant softening of the tissue (e.g. 86% decrease in modulus and an 84% decrease in stress at 10% strain). Tissue softening from enzymatic treatment was similar to softening seen during pregnancy – pregnancy is associated with 62-77% decrease in stress at 10% strain compared to non-pregnant human cervical tissue.19 Therefore, enzymatic treatment created a relevant model with physiological and mechanical properties similar to pregnant cervical tissue and appropriate for testing hydrogels ex vivo.

The present study differed from our prior study10 in that hyaluronic acid was added to the silk hydrogel. The addition of HA into the hydrogel system not only allows for further control of biodegradation but also retards temporal stiffening seen with silk only hydrogels.15 In addition, HA is one of the major constituents of cervical tissue,20 thus providing a more natural and biologically relevant hydrogel. Upon injecting 300 μL of the silk-HA hydrogel, the enzyme-treated tissue specimens exhibited an approximately 54% volumetric increase demonstrating the hydrogels ability to significantly augment cervical tissue. In addition, the injection of the hydrogel did not cause excessive stiffening - the modulus increased slightly but not significantly compared with enzyme-treated tissue. This shows the hydrogel’s potential as an effective material for augmentation without risking mechanical mismatch between biomaterial and surrounding native tissue. Mechanical mismatch can lead to tissue inflammation and damage33 and excessive stiffening can increase the safety concerns associated with a stiffer cervix during labor.

The study was limited by several factors. Although enzymatic treatment caused significant tissue softening, the mechanism of softening may not be similar to the mechanism of softening during pregnancy. Animal models of cervical remodeling have shown that these mechanisms are complex and preterm cervical remodeling can differ from term remodeling.34 Also, the present study does not provide information regarding the immune response to the hydrogel in vivo. In further studies, the injectable hydrogel will be evaluated in animal models to ensure biocompatibility and assess the efficacy of cervical augmentation. Additional studies will also focus on optimizing the in vivo degradability of the hydrogel as well as utilizing the hydrogel as a vehicle for drug delivery purposes.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we developed an ex vivo pregnant-like tissue model from non-pregnant human cervical tissue, providing a more physiologically relevant system to study the effect of cervical augmentation using injectable hydrogels. Using this model, we determined that a silk-HA hydrogel provides significant bulking without excessive stiffening. This project furthers our long-term goal of developing an alternative treatment for the prevention of preterm birth related to cervical insufficiency and cervical shortening.

6. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH (R01 EB021264; P41 EB002520). The authors would like to acknowledge the Tufts Animal Histology Core and Tufts Medical Center pathology lab for their histology services. The authors would also like to thank Bouchra Koullali for assistance during cervical tissue preparation and characterization; Professor Peggy Cebe for the use of the polarized microscope; and both Professor Cebe and Sarah Bradner for assistance in collecting birefringent data.

7. References

- 1.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, Oestergaard M, Say L, Moller AB, Kinney M, Lawn J. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health 2013;10 Suppl 1:S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, Adler A, Vera Garcia C, Rohde S, Say L and others. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379(9832):2162–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 2008;371(9608):261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Practice Bulletin No.142: Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(2 Pt 1):372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215(3):B2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berghella V, Ciardulli A, Rust OA, To M, Otsuki K, Althuisius S, Nicolaides KH, Roman A, Saccone G. Cerclage for sonographic short cervix in singleton gestations without prior spontaneous preterm birth: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using individual patient-level data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;50(5):569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N Engl J Med 2007;357(5):462–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, Fusey S, Baxter JK, Khandelwal M, Vijayaraghavan J, Trivedi Y, Soma-Pillay P, Sambarey P and others. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;38(1):18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landy HJ, Laughon SK, Bailit JL, Kominiarek MA, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Ramirez M, Haberman S, Hibbard J, Wilkins I, Branch DW and others. Characteristics associated with severe perineal and cervical lacerations during vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117(3):627–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JE, Partlow BP, Berman AM, House MD, Kaplan DL. Injectable silk-based biomaterials for cervical tissue augmentation: an in vitro study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214(1):118.e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Critchfield AS, McCabe R, Klebanov N, Richey L, Socrate S, Norwitz ER, Kaplan DL, House M. Biocompatibility of a sonicated silk gel for cervical injection during pregnancy: in vivo and in vitro study. Reprod Sci 2014;21(10):1266–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heard AJ, Socrate S, Burke KA, Norwitz ER, Kaplan DL, House MD. Silk-based injectable biomaterial as an alternative to cervical cerclage: an in vitro study. Reprod Sci 2013;20(8):929–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockwood DN, Preda RC, Yucel T, Wang X, Lovett ML, Kaplan DL. Materials fabrication from Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Nat Protoc 2011;6(10):1612–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partlow BP, Hanna CW, Rnjak-Kovacina J, Moreau JE, Applegate MB, Burke KA, Marelli B, Mitropoulos AN, Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Highly tunable elastomeric silk biomaterials. Adv Funct Mater 2014;24(29):4615–4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raia NR, Partlow BP, McGill M, Kimmerling EP, Ghezzi CE, Kaplan DL. Enzymatically crosslinked silk-hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Biomaterials 2017;131:58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osmers R, Rath W, Pflanz MA, Kuhn W, Stuhlsatz HW, Szeverenyi M. Glycosaminoglycans in cervical connective tissue during pregnancy and parturition. Obstet Gynecol 1993;81(1):88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akgul Y, Holt R, Mummert M, Word A, Mahendroo M. Dynamic changes in cervical glycosaminoglycan composition during normal pregnancy and preterm birth. Endocrinology 2012;153(7):3493–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straach KJ, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Hascall VC, Mahendroo MS. Regulation of hyaluronan expression during cervical ripening. Glycobiology 2005;15(1):55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers KM, Paskaleva AP, House M, Socrate S. Mechanical and biochemical properties of human cervical tissue. Acta Biomater 2008;4(1):104–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.House M, Kaplan DL, Socrate S. Relationships between mechanical properties and extracellular matrix constituents of the cervical stroma during pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2009;33(5):300–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rechberger T, Uldbjerg N, Oxlund H. Connective tissue changes in the cervix during normal pregnancy and pregnancy complicated by cervical incompetence. Obstet Gynecol 1988;71(4):563–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers K, Socrate S, Tzeranis D, House M. Changes in the biochemical constituents and morphologic appearance of the human cervical stroma during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;144 Suppl 1:S82–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012;9(7):671–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arun Gopinathan P, Kokila G, Jyothi M, Ananjan C, Pradeep L, Humaira Nazir S. Study of Collagen Birefringence in Different Grades of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Using Picrosirius Red and Polarized Light Microscopy. Scientifica (Cairo) 2015;2015:802980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rich L, Whittaker P. COLLAGEN AND PICROSIRIUS RED STAINING: A POLARIZED LIGHT ASSESSMENT OF FIBRILLAR HUE AND SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION. Braz. J. morphol. Sci 2005;22(2):97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 26.House M, Sanchez CC, Rice WL, Socrate S, Kaplan DL. Cervical tissue engineering using silk scaffolds and human cervical cells. Tissue Eng Part A 2010;16(6):2101–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aspden RM. Collagen organisation in the cervix and its relation to mechanical function. Coll Relat Res 1988;8(2):103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gan Y, Yao W, Myers KM, Hendon CP. An automated 3D registration method for optical coherence tomography volumes. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2014;2014:3873–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maillot KV, Zimmermann BK. The solubility of collagen of the uterine cervix during pregnancy and labour. Arch Gynakol 1976;220(4):275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd JW, Lechuga TJ, Ebner CA, Kirby MA, Yellon SM. Cervix remodeling and parturition in the rat: lack of a role for hypogastric innervation. Reproduction 2009;137(4):739–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao W, Gan Y, Myers KM, Vink JY, Wapner RJ, Hendon CP. Collagen Fiber Orientation and Dispersion in the Upper Cervix of Non-Pregnant and Pregnant Women. PLoS One 2016;11(11):e0166709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayes FL, Liu B, Moutos FT, Kuchibhatla M, Guilak F, Leppert PC. Loss of stiffness in collagen-rich uterine fibroids after digestion with purified collagenase Clostridium histolyticum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215(5):596.e1–596.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalaba S, Gerhard E, Winder JS, Pauli EM, Haluck RS, Yang J. Design Strategies and Applications of Biomaterials and Devices for Hernia Repair. Bioact Mater 2016;1(1):2–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahendroo M Cervical remodeling in term and preterm birth: insights from an animal model. Reproduction 2012;143(4):429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]