Introduction

These Guidelines define the general principles to be observed when transporting rodents, rabbits, ferrets, dogs, cats, nonhuman primates, minipigs and amphibians including Xenopus for use as laboratory animals. This is an international document and the Group is aware that legislation regulating animal transport varies between countries. For instance, transport within the USA will be covered by the Animal Welfare Act, within Europe by Convention ETS 193 (see below) or globally by international agreements such as the IATA Live Animals Regulations, which are updated annually. While it is essential to ensure that legislative requirements and other guidelines relating to health and animal welfare are met, it is also very important to think beyond legal baseline standards and strive to minimize distress and improve welfare.

This resource will help to achieve the objective of moving animals in a manner that does not jeopardize their well-being and ensures their safe arrival at their destination in good health, with minimal distress. This is important to ensure both good animal welfare and the validity of future scientific procedures.

How to use these Guidelines

This document is laid out in two parts:

Part I sets out general considerations relating to transport that apply to all species referred to in these Guidelines. It begins by focusing on the elements of an effective route plan and then provides guidance on ensuring that animals are fit for transport, that vehicle specifications are appropriate and that drivers are competent and properly trained to monitor and care for the animals in their charge. The end of Part I addresses general requirements for container design, materials, provisions and stocking density for all species.

Part II gives detailed requirements of container design for individual species and other groups, guides for feeding and watering in transit, care and loading and any other relevant information that will help to reduce transport stress and improve welfare.

The Group recommends that Part I is read in its entirety before any of the sections in Part II are consulted, in order to set the context for the specific recommendations and ensure that the maximum benefit is obtained from this document. Note that this report is intended to supplement but not replace careful reading of the relevant legislation. Where appropriate, relevant articles from Convention ETS 193 are listed in boxes within the text for ease of reference (for supplementary information on the UK legislation see www.lasa.co.uk).

Part I General considerations

Many aspects of the animal transport process have a direct impact on welfare. These include route or journey planning2, container design, vehicle design, the competence and attitude of drivers and others involved in the transportation, travel duration and the nature of food and water supplies. Critical appraisal and refinement of all these organizational aspects of transport is essential if animal welfare is to be safeguarded during journeys.

These Guidelines refer to the following commonly transported laboratory animals: rats, mice, hamsters, gerbils and guineapigs, dogs, cats, rabbits, ferrets, minipigs, nonhuman primates and Xenopus laevis.

1. The impact of transport on animal welfare

Studies of animal transport have focused primarily on farm rather than laboratory animals (see Grandin 1997, SCAHAW 2002, 2004 for reviews). However, it is clear that transport is a significant stressor3 that may have an impact on both animal welfare and on the scientific validity of any future studies involving the animals or their offspring (Claassen 1994, Reilly 1998). This includes all journeys and all species, from mice moving within a building to primates undergoing lengthy journeys by air (Wallace 1976, Malaga 1991, Tuli et al. 1995).

The physiological and behavioural response to stress affects a number of biological functions and systems. If stress is extreme or prolonged, substantial effort is required to maintain a state of equilibrium and the animal may become aware of this effort and suffer as a result (Reilly 1998). This effort can be compounded by the effects of fear, nausea, hunger, thirst or pain, depending on the species and circumstances under which they are transported (SCAHAW 2002, 2004).

Stress during a journey may also increase the risk of disease for transported animals, yet the potential to monitor animal well-being, and to act if it is compromised, is often significantly curtailed during transport. The primary goal for all those involved in animal transport is therefore to reduce any potential for stress or fear to an absolute minimum, considering all potentially distressing events that an animal may experience throughout the journey (Table 1).

Table 1. Potential sources of stress for animals undergoing transport.

| Handling |

| Separation from familiar conspecifics, possibly individual housing |

| Confinement in an unfamiliar transport container |

| Loading and unloading |

| Movement and vibrations during the journey, including acceleration and deceleration |

| Physical stress due to maintaining balance (especially larger animals) |

| Unfamiliar sights, sounds and smells |

| Fluctuations in temperature and humidity |

| Withholding of food, or voluntary abstention from eating or drinking |

| Disruption of light:dark regime |

| New housing and care protocols at the end user establishment, including unfamiliar humans and possibly new social groups or hierarchies |

A number of parameters have been used to evaluate stress in animals, such as levels of circulating cortisol, corticosterone and glucose, adrenal gland mass, behaviour, food and water consumption and weight loss (see Moberg & Mench 2000). These measures are generally used in conjunction with one another to provide a basis for assessing stress, since (for example) elevated plasma cortisol can be one of many indicators of stress used to assess the adverse effects of transport in many circumstances but can also occur in response to more positive events (Moberg 2000).

Many studies have found that transport causes significant changes in the parameters used to assess stress and that varying periods of time are required for values to return to baseline levels. For example, mice have been reported to acclimatize 24 to 48 h postarrival on the basis of immune function and plasma corticosterone levels (Landi 1982, Aguila et al. 1988, Drozdowicz et al. 1990). However, a study that monitored behavioural indicators of stress as well as corticosterone found that mice had not fully acclimatized 4 days after transport from one room to another (Tuli et al. 1995).

Studies in rats and rabbits have recommended adaptation periods of 3 days and 48 h, respectively, yet periods of 3 to 5 days have been recommended for rats used in toxicology testing (Damon et al. 1986, Toth & January 1990, van Ruiven et al. 1998). It has also been suggested that the behaviour of non-transported rats is affected if they can detect the odour of rats that have undergone transport and are therefore stressed (de Laat et al. 1989). It is apparent from this that transport may have profound effects on rodents and rabbits in ways that may not be immediately obvious, and that they (in common with all other species) require careful monitoring and an adequate adaptation period following arrival.

Transportation is also stressful for larger animals such as laboratory beagles, pigs and primates (Kuhn et al. 1991, Dalin et al. 1993, Wolfensohn 1997, Bergeron et al. 2002). Heart rate attains the highest levels during loading and unloading in the beagle, which has also been reported in farm animals such as sheep (Knowles et al. 1995, Bergeron et al. 2002). It is perhaps to be expected that the loading and unloading processes would be especially stressful, but other incidents may appear to be of little consequence to humans yet highly significant for animals. For example, greyhounds show a greater (hormonal) stress response when transported in the belly hold of aircrafts as opposed to the main cargo hold (Leadon & Mullins 1991). Species with greater cognitive abilities, such as non-human primates, may be more aware of their change in circumstances and fearful of the outcome, to the extent that behavioural changes reflecting stress can persist in primates for over a month after arrival (Wolfensohn 1997, Honess et al. 2004).

To summarize, there are two key messages from the literature on animal stress in general and transport in particular. Change is stressful to animals, and transport is an especially powerful stressor that should be regarded as a major life event and not undertaken unless absolutely necessary. Even where every possible effort has been made to minimize transport stress, plan journeys with care and ensure that all staff are properly trained and empathetic, animals undergoing transport will still experience at least some of the stressors set out in Table 1.

The first step towards minimizing the impact on animals undergoing transport is careful consideration of their nature and behaviour. This includes practical factors such as their normal travelling posture and whether they will (or should) eat or drink while travelling. Other issues, such as the animals’ likely perception and interpretation of their environment, are critically important when predicting which events are likely to cause the most stress and will require special attention when planning journeys. These factors should all be given due priority when making decisions on:

the health and welfare of the animals, including their fitness to travel;

the design and materials of the containers, including provision for loading and removing animals with the minimum discomfort, and inspection in transit;

the number of animals in each container and the space given to each animal;

the environmental conditions within the animal container;

the quality and quantity of substrate, nesting material, food and water (or alternative supply of liquid);

the duration of the journey;

the number of stops or changes between vehicles, especially if unloading and reloading is required;

the type of vehicle(s) involved;

the experience, attitude and training of personnel handling and transporting the animals;

how animals will be helped to adapt and how their recovery from the journey will be monitored when they reach their destination.

This resource aims to facilitate best practice in all of these areas so that those involved in animal transport can minimize the suffering and improve the welfare of the animals in their care.

2. Legislation

Import or export of animals must always ulfil the requirements of transport regulations in every country that the animals will pass through. All concerned should be aware of relevant legislation and avoid delays by ensuring that all the required documentation is correct.

Specific procedures should be designed to ensure full and effective enforcement of all legislation and guidelines, in particular by ensuring traceability of all transport operations. It is the responsibility of the consignor to ensure that all legal requirements are thoroughly researched and comprehensively met.

For details of ETS 193, the European Convention on the Protection of Animals during International Transport (Revised, 6/11/2003), see http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/193.htm.

3. Route plans

There are few specific national regulatory requirements relating to laboratory animal transport. However, journeys involving laboratory animals should still be planned as carefully as those undertaken in other areas of animal use where transport legislation does apply. A professional shipper intending to send any species on a journey that is of significant duration or complexity, i.e. more than 50 km or involving changes in mode of transport, should prepare a route plan that can address most eventualities and problems that may arise4.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 7: journey planning

3.1. Basic principles

The principles set out below should be considered in depth and comprehensively covered within each route plan when preparing for the shipment of animals under conditions that will ensure their welfare at all stages of the journey. The nature of each route plan will vary with the species, distance, and type of vehicle(s) and whether the journey crosses international borders. However, all route plans should include contact details of people who can act in an emergency, or otherwise assist at the various stages of the journey.

3.2. Choosing a route

Those planning journeys should discuss their choice of preferred routes and shipping agents with the sponsor and should also share their experiences of previous journey protocols (successful or problematic) with others. It is advisable, where possible, to identify more than one route, as this enables alternative arrangements to be made immediately if the chosen route becomes no longer available or otherwise unsuitable. Invariably it is preferable to select direct flights, unbroken routes and preferably just one carrier where possible.

Long-distance journeys are likely to have more detrimental effects on the welfare of the animals than short ones. Although transport time and distance should be kept to a minimum, from the animals’ perspective the quality of journey is extremely important. An uninterrupted journey is preferable to one broken by stops or rest periods, especially if unloading and re-loading are involved. Loading, the initial stages of the journey and unloading procedures are the most stressful because they can involve any or all of handling by humans, mixing with or perceiving unfamiliar animals and strange surroundings.

It is also important to consider the climate, season and time of day when animals will be travelling. For example, during excessively warm weather it may be advisable to travel overnight to avoid high ambient temperatures during the day. See also advice produced by the UK DEFRA on the transport of animals in hot weather: http://www.defra.gov.uk/animalh/welfare/farmed/transport/hot-letter.pdf.

3.3. Documents

Varying combinations of the following documents will be needed according to journey type, species, microbiological status and route. They will need to be collated into a usable form, such as a book or pamphlet, which should be attached to container number one of the consignment.

General details

AWB number/IATA Shipper’s Certificate for Air (this should be on each container)

Import licences issued by the State Veterinary Service

Crate labels, e.g. ‘THIS WAY UP’ (orientation arrows), feeding guide, full consignee address and 24 h contact telephone number

CITES permits, where necessary

Definitive invoices for Customs purposes

Fitness to travel documents

Individual or group animal records

Health certificate

Health screen

Journey log, if separate

List of contacts with telephone numbers

Packing list

Quarantine labels

Route plan or Animal Transport Certificate

Transfer authorizations from specific bodies that regulate laboratory animals use, e.g. the UK Home Office, US Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Vehicle registration details and insurance

Animal details

Species, strain, scientific name, number, sex, age, weight, identification numbers, any special requirements resulting from phenotype.

Personnel details

The name, address, phone, mobile and fax numbers for the following contacts are essential:

Sender

Intermediaries

Consignee

Shipper/Carrier

Person with ultimate responsibility

Veterinarian

Crates

Date and times the animals were packed, loaded, and departed with clear ‘LIVE ANIMALS’ and orientation arrows

24 h contact telephone number

Expected events

Proposed and actual rest periods

Pre-journey review of plan by consignor

Post-journey review of plan by new owner

Other documents

It is also good policy for certain company procedures to be available to drivers in the format of standard operating procedures. Such records might comprise:

The company’s own code of practice for animal transportation

Species specific space, substrate, nesting material, food and water requirements

Essential notifications and communication

A log of journey progress

Time plan of activity

Training requirements

Vehicle operation requirement—cleaning, maintenance

Emergency procedures and contacts

If imported, records of collection/delivery

In the UK, under WATO97, an Animal Transport Certificate must accompany all vertebrate animals travelling for more than 50 km, or documents containing similar information referred to here as a route plan5. It should record essential details of the shipment and journey events at various stages of the journey and include instructions for contingencies in the event of delay or other mishap. A specimen Animal Transport Certificate and route plan is given in Appendices 1 and 2.

It is advisable to check whether the necessary documents have been aligned with the United Nations (UN) Layout Key for Trade Documents. These are internationally agreed standards that are easily translated because common information appears in standard positions on all forms. Many countries have trade facilitation organizations that can advise on UN aligned documents, for example SITPRO in the UK (see www.sitpro.org.uk).

The TRACES system will be available to provide formats for documents for both imports and exports of live animals and animal products. It is expected to become mandatory from 1 January 2005 to use this system for notification of the appropriate authorities of impending animal transport movements. For guidance see http://sanco.cec.eu.int/traces.

All the required documentation must be prepared accurately and in good time before each journey. International transport should be planned well in advance as it can take several weeks to make all the necessary arrangements and to obtain permits. Documents may be required not only to permit animal transport but also to provide necessary information on health status; this may include historical records required by the client. All original documents should be included with the shipment and original copies forwarded to other parties as necessary.

Spare copies should be made of all documents and a copy of each sent in advance to the recipient. Where journeys involve crossing international borders, it is good practice to pack multiple copies of all licences, allowing for the loss of one at every border inspection point en route. If licences are not available, the animals may not be released.

3.4. Courier details

It is the importer’s responsibility to make sure that a person with good working knowledge of the species and strain to be shipped has checked and confirmed that proper arrangements are in place to assure good welfare. Road transport using dedicated vehicles and staff allows for the best supervision from starting-point to destination. Drivers should receive instruction in the care of animals under their charge. They should be responsible, experienced, empathetic and competent (see Section 6). In addition, where animals can be accessed directly or are travelling loose, an animal technician or other competent person who can attend to their welfare needs should accompany them. This is essential for consignments of large species, which should not be under the care and control of a driver alone.

Records should be maintained in a specified format as standard operating procedures for organizations that ship, import or export animals. As a minimum, records should contain:

the organization’s own code of practice for animal transportation;

practices for boxing and containment;

husbandry requirements including substrate, food and water, stocking densities;

environmental conditions;

the process for essential notifications and communication;

time-plan of activity;

all necessary documentation (including licences and labels);

guidance on relevant local transport legislation

training requirements;

vehicle cleaning;

vehicle maintenance and checking;

emergency procedures and contacts;

journey returns according to government requirement.

3.5. Responsibilities, roles and communication

Journeys can involve several stages and many people in various roles, including the supplier, consignee, drivers, shippers, handlers in transit and other subcontractors, customs officers and eventual recipient. Each should know and understand their role and which actions to take in case of emergencies or unforeseen circumstances. They should also know the relevant contacts and handover procedures at the next stage of the journey. However, it is unwise to assume that they all do without making enquiries and checking this before the journey begins.

Ensuring that roles are properly defined and understood can be especially difficult for complex international journeys, so instructions should be available in all relevant languages as animals will pass through different countries. Those involved at each stage should know the contacts and handover procedures for the next stage. It is also good practice to ensure that a handling and feeding guide and 24 h contact telephone numbers for people who can act or assist at the various stages are securely attached to the crate.

Good communication concerning the progress of the journey is essential between the supplier, shipper and recipient so that appropriate contingency plans and schedule alterations can be implemented to ensure the animals’ health and welfare at all times. Each individual involved with every stage of the journey should have access to the entire route plan, know whom to contact for information and have a clear understanding of their responsibilities. For any journey involving transfers or more than one mode of transport and all international journeys, the supplier should notify the recipient that the animals have been dispatched as soon as critical stages of the journey has commenced. Vehicles should always be fitted with mobile phones and/or drivers should carry them.

When planning transport by air, it is essential to liaise with the animal holding facility at each airport en route, to ensure that animal husbandry and veterinary support are adequate. There must be appropriate cover outside normal working hours and security staff, or whoever is on call, should know how to direct calls and take appropriate action.

It is important that those transporting animals are clear who has responsibility for animals, and what those responsibilities are, at each stage of the journey. If a journey involves more than one carrier or agent the consignor is generally responsible for arranging:

documentation for the whole journey;

adequate transport, rest, feed and water throughout the journey;

sufficient empathetic, competent attendants to accompany the animals, where necessary.

During a road journey where the animals are not unloaded from the vehicle, the driver or attendant is responsible for the animals. However, note that under certain circumstances a contravention in the regulations may also be the responsibility of the employer or consignor, particularly where the journey planning may have been at fault.

Animals imported into the EU must travel through a border inspection post (BIP), which requires 5 h warning in advance of arrival of by air and 24 h warning for other modes of transport. European Community Regulation number 136/2004 sets out procedures for veterinary checks at BIPs and includes the UN aligned Certificate of Veterinary Entry Document (CVED) with accompanying guidance notes; see http://europa.eu.int/eur-lex/pri/en/oj/dat/2004/l_021/l_02120040128en00110023.pdf.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 4: general principles for transport

ETS 193 Article 8: animal attendants

ETS 193 Article 29: road vehicles or rail wagons on roll-on/roll-off vessels

ETS 193 Article 30: transport by air

3.6. Ensuring consistent standards

It is particularly important to consider the experience, attitude, competence and performance of each carrier. Standards may vary, particularly between different countries, and this should be duly considered before committing animals to the care of subcontractors. The type of vehicle being used to transport animals at all stages of the journey is critically important. Reasonable enquiries should be made to ensure that the vehicle complies with all requirements of this guidance, especially in its ability to cool incoming air and/or maintain a suitable environment for the animals.

3.7. Containers and provisions

Transport containers should be prepared well in advance of departure. Animals must be provided with adequate bedding and sufficient food and water (or suitable alternative sources of fluid and nutrients) for at least twice the expected duration of the journey (see Section 7 and specific recommendations in Part II). For some species such as nonhuman primates and dogs it may be necessary to plan for acclimatizing animals to the shipping containers prior to loading.

Arrangements should be made for animals to be transported using systems that avoid overheating and maintain welfare during reasonable unforeseen circumstances. The use of containers with non-occluded apertures that maximize ventilation and visibility should be considered for rodents if strict bio-security is not required. Journeys may need to be delayed or postponed during periods of extremely hot or cold weather; this can create health and welfare problems when transporting rodents in filtered shipping crates unless the whole of the journey is made using dedicated airconditioned vehicles.

It is also important to ensure that any mandatory veterinary checks (e.g. at EU border inspection posts) include comprehensive inspection of animal welfare and the conditions in which animals are transported.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 6: container design and construction

ETS 193 Article 16: floors and bedding

ETS 193 Article 23: containers

3.8. Labelling

Each container must be clearly marked with:

‘LIVE ANIMALS’

‘THIS WAY UP’, including ‘orientation arrows’

Instructions for handling the crate

The type and number of animals in the container

The consignor’s name, address and a 24 h contact telephone number

The consignee’s name and address and 24 h contact telephone number

Feeding and watering instructions, even if these read ‘DO NOT FEED’

3.9. Final checks

Before any animals are transported, appropriate checks should be made to ensure that the recipient expects the shipment and will be ready to receive the animals. The recipient should be informed of an estimated time of arrival wherever possible and updated with a new expected time of arrival should there be a delay or if a journey takes less time than expected. When journeys commence (or animals arrive) outside normal working hours, it may be necessary to ensure that security staff know about the shipment and know whom to contact for receipt of animals. Final checks should assure that the animals are fit for the intended journey.

3.10. Contingencies

The following should always be considered so that adequate contingency plans can be put in place.

Delays to shipments. Appropriate arrangements must be made to care for the animals if an unavoidable setback occurs, and the transport container may need to be equipped with facilities to feed and water the animals. Some species may have to be unloaded and rested if there is a significant hold-up; e.g. dogs may need exercise, non-human primates may require an alternative facility for emergency use. This may be in a country other than the ultimate destination if the journey cannot be completed in a satisfactory time. Animals that are transported in secure containers should be provided with sufficient food, substrate and water to be able to travel for at least 48 h without the need to intervene or otherwise remove them from their container.

Abandoning the chosen route. Alternative routes should be considered in advance and a pre-prepared contingency plan that can swiftly be implemented should be in place.

Vehicle breakdown. If the vehicle breaks down, animals should not be left alone. The driver should have a form of external communication such as a car phone or mobile phone. The driver should remain with the vehicle where possible and a back-up system for replacement vehicles and drivers should be available. A contact telephone number should be made available by the consignor 24 h a day to give assistance as required to the transporter.

Paying any tax or duty required on arrival. Even if it is not due, officials at border posts may demand it on the spot. It is best to ‘pay now, argue later!’.

Death in transit including emergency euthanasia. Any mortality during a journey should be reported to the consignee and the cause of death properly investigated, particularly if a significant number of individuals have died. Appropriate postmortem examinations should be carried out, including an evaluation of the environment within the transport container(s) wherever possible. The approximate time of death can be estimated using the onset or wearing-off of rigor mortis, or indications of early or advanced autolysis. This can then indicate the stage of the journey when the animal died. Unless a carcass is showing gross signs of decomposition, experience has shown that a combination of good observation and careful necropsy technique will often provide sufficient information to infer the likely cause of death, which in turn can be used to help prevent future mortality.

3.11. Arrival

Both consignor and recipient should agree on the conditions of transport and departure and arrival times, so that the recipient can ensure that appropriate accommodation is prepared and that animals will be provided with fresh food, drinking water and bedding. It is important to unload the animals from their containers without delay and have them inspected by a suitably trained and competent person before they are placed in their home cage. Should any welfare issues be found, the consignor and others involved in the journey should be notified as soon as possible.

On arrival, the animals should be placed in previously prepared cages, fed, watered and rested. With each consignment there should be an Animal Transport Certificate (see Section 3.3) as well as a manifest giving details of each shipment and indicating animals requiring particular care.

The recipient should understand that they have a duty of care to the animals and a responsibility to assure their safe and secure arrival. This includes the responsibility to make contingency plans so that animals can be accepted if delays occur and shipments arrive outside normal working hours. Alternatively, arrangements may have to be made for animals to be diverted and accommodated elsewhere if they cannot enter the facility for immediate unloading. Whoever receives the animals on arrival should sign the delivery note and inspect the animals as soon as possible, ideally before the carrying agent leaves.

Following any journey, an acclimatization period is essential before laboratory animals are used in procedures. Each establishment should determine appropriate periods of acclimatization for different species, strains, etc. However, as a general guide, at least 7 days’ acclimatization is necessary following transport between sites and at least 3 days between buildings on the same site (Section 8).

4. Habituation and fitness to travel

Animals for dispatch should be in good health. This is important for welfare reasons and also because stress during transport may cause latent infection to become clinically apparent. Prior to packing, animals should be inspected by a suitably competent, trained and responsible person. Animals should normally be rejected from the shipment if any deviation from normal behaviour or good health is observed.

Confinement in a container, variation in environmental conditions and movement affect different species in various ways. Animals require a period of adjustment before removal from the facility to which they are accustomed. This applies particularly to non-human primates and dogs, where acclimatization may be required to conditions during transit. For example, exposing them to the transport containers a few days before loading will reduce anxiety levels. Larger animals, e.g. rabbits and heavier animals, should be supervised until the time when they are shipped.

Sufficient food and moisture should be provided for at least twice the expected journey time.

Careful consideration may need to be given to the time of travel to avoid loading animals during extreme climatic conditions unless suitable protective precautions are taken.

Knowledge of actual conditions en route is essential, as opposed to assessing the most direct route on paper. It may be necessary to consult others with direct experience of the journey.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 9: fitness for transport

ETS 193 Article 10: inspection and certification before loading

ETS 193 Article 11: rest, water, feed and habituation prior to loading

4.1. Special considerations

These guidelines apply to routine journeys involving healthy animals. However, the health of laboratory animals may sometimes be compromised for experimental purposes. Whatever the circumstances, animals should always be fit for the intended journey and, where their health is compromised, appropriate precautions must be taken to ensure their welfare. These will necessarily vary on a case-by-case basis, but some common examples are set out below.

Individuals that carry harmful genetic mutations or that may be otherwise genetically modified (GM) may have special requirements and due regard should be paid to the effects of the modification. Unforeseen welfare problems can be avoided by transporting GM animals as fresh or cryopreserved embryos, or cryopreserved gametes, wherever possible (Robinson et al. 2003). Wide consultation between consignor, carrier and user is necessary when planning journeys for GM animals, including those in embryonic form. All GM animals should be accompanied by comprehensive information including the nature of the phenotype and any specialist management needs with respect to husbandry and veterinary care (Robinson et al. 2003).

Age, size, surgical alterations and health status can also affect the ability to cope with transport stress and it is important to research ways of reducing the potential impact of transport on animals with special needs. Stocking density should be decreased and/or additional ventilation and cooling provided for animals subject to heat stress (such as obese mutants) and diabetic animals should be provided with adequate and appropriate sources of fluids. Small mice, hairless mice and those travelling with few others are also prone to cold, so should be provided with additional nesting material; immunocompromised animals should be transported in filtered shipping crates to minimize exposure to potential pathogens.

Sick or injured animals should not normally be transported unless the journey is necessary for the purposes of treatment, diagnosis, or humane killing. They may also be transported for experimental or other scientific purposes approved by the relevant competent authority, if the illness or injury is part of a licensed research programme. No additional suffering should be imposed by the transport of such animals, and particular attention should be paid to any additional care that may be required. A competent person should confirm that such animals are fit for the intended journey or that they are subject to scientific procedures as defined by legislation regulating animal use. Pre-shipment screening, which should be planned well in advance, may be necessary for specific infections. In all cases where normal health and/or welfare may be compromised, route plans should cater for animals’ special needs and should include clear guidance on actions in case of delays, morbidity or mortality. Animals requiring any kind of special care during transport should never be transported in inaccessible holds.

Sedation of laboratory animals prior to transport should only rarely be necessary and is more likely to compromise their welfare by affecting their ability to thermoregulate. If there is an exceptional case for sedation on welfare or veterinary grounds, drugs should only be administered under the direction of a veterinarian who is fully apprised of the journey plan. It is also essential that all those concerned with transporting and caring for the animals en route know that they have been sedated and are aware of any special care procedures and contingency plans if the consignment is delayed and the sedation begins to wear off.

4.2. Shipping and pregnancy

Article 9 of ETS 193 states that pregnant female mammals shall not be transported either during the last tenth of the gestation period or for at least one week after they have given birth. However, the Transport Working Group recommends that pregnant laboratory animals should not normally be transported during the last fifth of gestation (see Table 2). This is to ensure that they are not put at risk of abortion or that parturition does not commence during transport. Some species, for example rabbits, are more likely to abort under the stress of transport and should not be moved during the last third of gestation. It is also preferable to move larger species, such as dogs and nonhuman primates before the last trimester of pregnancy. However, they can be transported nearer the time of parturition provided that the journey is direct, of relatively short duration, and can be undertaken under appropriate veterinary direction and supervision.

Table 2. Typical gestation periods of common laboratory species and recommended permissible shipping times.

| Species | Duration (days) | Can be shipped up to (days) |

|---|---|---|

| Rat | 21 | 17 |

| Mouse | 21 | 17 |

| Guineapig | 56–75 | 45 |

| Pig | 114 | 91 |

| Rabbit | 30–32 | 22 |

| Dog | 61–65 | 40 |

| Cat | 64–67 | 42 |

| Common marmoset | 144 | 96 |

| Long-tailed macaque | 153–167 | 102 |

Low stocking densities must be considered for pregnant animals of any species because their ability to dissipate body heat can be limited.

If nursing animals with young are to be transported following an appropriate period after parturition (a minimum of 7 days, as above), they will normally require additional care including adequate additional bedding and nesting material. Neonates should not be transported until their navels have healed.

5. Vehicle design

Vehicles carrying laboratory animals should be suitable for the purpose. They should be insulated and fitted with controllable heating, cooling and ventilation. The ventilation system should be capable of working independently of the vehicle’s main engine. Alarms should be fitted to warn the driver when certain variables, e.g. temperature, humidity or fan operation, go outside pre-set limits. The interior of the cargo area must be designed so as to allow thorough cleaning and disinfection. Lights should be fitted in the cargo area for loading and intermittent inspection. Ventilation louvers or apertures for the cargo area should be sited to allow an even distribution of air to prevent stagnation, draughts and ‘cold spots’. Containers should also be protected from adverse weather conditions such as extremes of temperature, sunlight, noise and draughts. Lashing points should be available on the floor and walls to secure containers during transport and prevent them from toppling. Alternatively, rubber mats on vehicle floors will prevent well-packed containers from significant movement liable to disturb the animals.

All vehicles used to transport live animals should have the following:

Climate control, with back-up that is independent of the main engine

A system to record cargo temperatures

Mobile phone or car phone

Instruction for contingencies

Back-up in the event of a breakdown

Instructions for handover procedures

Proper loading, packing and stacking in a safe and secure manner

Floor attachment points for transport boxes

Internal lighting

Trip recording equipment for environmental parameters in the cargo area

Secure, mesh internal doors

The ability to view the load from the driver’s seat

Safety grilles and a lockable 2-door system, for the transport of non-human primates and animals subject to rabies quarantine regulations

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 22: lighting

ETS 193 Article 27: transport by road

ETS 193 Article 29: road vehicles or rail wagons on roll-on/roll-off vessels

6. Driver and attendant training and competence

Ensuring that staff are trained, empathetic and competent to handle and care for the animals is central to safeguarding their welfare during each journey. Ideally, an attendant who is in charge of the welfare of the animals should accompany animal consignments. This person may be the driver in certain circumstances. Attendants and/or drivers should receive appropriate training or have the equivalent practical experience qualifying them to handle, transport and take care of animals, including in case of emergency. However, such attendant or driver requirements may not be required when animals are transported in containers which are securely fastened, adequately ventilated and containing sufficient water and food for a journey of twice the anticipated time.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 8: attendants

It is important to ensure that any member of staff handling livestock during transport has completed a training course recognized by the competent authorities of all countries that the animals will travel through.

There are currently no formal training requirements for those involved in the transport of laboratory species. However, schemes are being developed for those involved in the transport of racehorses and livestock that will include a certificate of competence. Similar courses are likely to be established for laboratory animal transport that will have the authority to judge and assure competency. Such courses should include:

The basic biology and husbandry of relevant species

Animal handling and restraint

Recognition of well-being, discomfort, pain, distress and suffering; appropriate measures to alleviate adverse effects; recognition of when veterinary attention is necessary

Emergency euthanasia techniques

Legislation relating to animal transport and to health and safety, including quarantine regulations

Certificates of competence should be carried in the vehicle and made available for inspection as required (note that the AATA Manual lists recommended competencies for consignors, consignees, carriers and drivers). Drivers should also carry an emergency procedure reference book that covers items such as mechanical breakdown and procedures following an accident or extensive delays.

Both drivers and handlers will need to be aware of health and safety requirements that may be relevant to handling laboratory animals, particularly if they are known to suffer from allergies to animals. Drivers should consult with the relevant Health and Safety Authority to determine whether prophylactic vaccinations are necessary.

6.1. Key driver and attendant competencies

Poor welfare is often due to a lack of education on the part of those responsible for animal care. Training in the competencies listed below should be a prerequisite for any person handling animals during transport and should be provided only by organizations approved by the competent authorities.

Knowledge of which people are responsible at various stages of the journey

Knowledge of which organization to contact for advice on transport conditions or documentation

Knowledge of enforcement authorities to inspect animals before, during and after a journey

Basic knowledge of their authorization requirements

Know how to plan a journey; an ability to anticipate changing conditions and make contingencies for unforeseen circumstances

Knowledge of vehicle use, construction requirements and how driving affects welfare during transport

Ability to load and control a roadworthy vehicle to ensure the welfare of the animals

Knowledge of appropriate methods of handling animals during loading and unloading

Knowledge of statutory feed, water and rest requirements for the species

Knowledge of stocking densities, taking into account journey duration and ambient conditions

Understanding the importance of temperature and humidity on animal welfare and adjustment of heating and ventilation accordingly

Knowledge of the causes of stress, ability to recognize signs of ill health and poor welfare for the species; when to seek veterinary advice

Ability to care for animals that become unfit or injured during transport

Knowledge of catching and handling the species carried in case of emergencies

The day-to-day conduct of the transporters is critical for the welfare of the animals concerned. Checks by competent authorities may be hindered as transporters can operate freely in different countries. In particular, they should always be able to provide proof of their authorization, should report routinely any difficulties, and keep precise records of their actions and the results of those actions.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 8: attendants and their training requirements

ETS 193 Article 14: animal handling

6.2. Handling crates

It is vital that anyone responsible for handling crates containing live animals does so competently and with respect and understands why this is necessary. Containers holding animals should be moved carefully without rough handling, excessive noise or vibration and maintained as level as possible. Unauthorized persons and staff should be prohibited from approaching or disturbing animals or from feeding them without appropriate instruction. If it is necessary to open the container during transit, it should be done by authorized persons in an enclosed area so that the animals cannot escape.

When animals are to be carried in quantity, care should be taken to maintain proper separation of containers in the cargo area so that there is adequate air circulation throughout the stacks. Drivers should also be aware of the need to check containers regularly to ensure that they are adequately protected from any significant exposure to precipitation, prolonged exposure to direct sunlight or high winds. Any of these will affect the temperature within the container.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 23: containers

ETS 193 Article 12: loading and unloading

ETS 193 Article 12: equipment and procedures

ETS 193 Article 19: ventilation and temperature

7. The container and its environment

Containers used to transport animals must be appropriate for the journey and species transported. An ideal container should:

confine the animals in comfort and with minimum stress for the duration of the journey;

contain sufficient food and water (or moisture in a suitable form);

contain sufficient bedding so that the animals remain comfortable and in conditions within their thermo-neutral zone;

maintain an environment in which most factors known to cause stress are reduced to a minimum;

allow adequate ventilation;

be escape-proof, leak-proof and capable of being handled without the animals posing a risk to handlers;

be of such a design and finish that an animal will not damage itself during loading, transport or removal from the container;

be designed to prevent or limit the entry of microorganisms when holding virus-free or microbiologically-defined animals;

be designed so it can be thoroughly disinfected between shipments if intended to be reusable;

be designed so that the animals and their provisions can be inspected without opening the container.

Below are some general principles to help fulfil the above requirements6, while Part II of these Guidelines provide some illustrative dimensions for container sizes. Note that these may need to be scaled to the actual size of the animal(s) for which the container is constructed. IATA sets out Live Animals Regulations relating to the transport of animals by air. These include advice on general care and loading, the design and construction of containers, appropriate packing details or stocking densities and arrangements for feeding and watering. Most airlines are signatories to the Live Animals Regulations, which are revised and published annually, and will only accept animals packed and transported accordingly.

7.1. Design and materials

The usual design for a container to transport small laboratory animals is a rectangular box, with the shape and dimensions dictated by the species and strain for which it is intended. Where rectangular boxes are used, then they are usually designed with a feature to ensure adequate ventilation between the boxes when stacked together. This can be achieved by incorporating sloping sides into the box design or spacer devices on the top and base of the box. Handholds or other lifting devices must be provided to enable the containers to be lifted without undue tilting or bringing the handlers into close contact with the animals; these can also act as spacers to ensure good ventilation (see below). Any container or stack of containers weighing more than 25 kg will need to be moved using a forklift, so should have properly designed entries for the load forks to engage safely and securely.

Adequate ventilation is essential. Air vents should be sited on at least two opposite sides of the container. Both container and vents should be designed so that occlusion of the vents cannot occur. The combined area of the ventilation apertures and vents should be determined according to the species, dimensions of the container, intended stocking density, filter material used and likely ambient conditions prevailing during transport. Vents should be covered with wire or plastic mesh of such a gauge that no part of the animal can protrude. Sharp edges should be avoided for both the welfare of the animals and to avoid injury to those involved in carrying the container.

Microbiologically secure containers for animal transport usually have ventilation apertures covered with some form of filter material. The pore size depends on the degree of filtration required and the filter’s ability to reliably remove all airborne microorganisms, particularly viruses. It is vital to remember that filter material decreases the ventilation within the container by up to 70%, particularly if it becomes damp. Other factors such as stocking density, container design and overall ventilation rate should be adjusted to compensate for this. Filtered containers should also have a port or viewing panel so that animals can be monitored in transit. When carrying animals of special categories, e.g. specific pathogen free (SPF) animals, the shipper must comply with the specific container requirements detailed in this document.

A variety of materials are available for container construction. Plastic, corrugated cardboard or twin-walled polypropylene (Correx) are commonly used. Other materials that are less frequently used include wood, MDF, metal and fibreglass. Plastic and fibreglass are rigid, strong and durable and often used for reusable transport containers. Correx and corrugated cardboard are relatively cheap and easy to dispose of and therefore tend to be made into containers that are not reusable or do not need to be especially robust. Corrugated cardboard containers are used for transporting laboratory rodents for journeys of relatively short duration. The inside surface of cardboard containers can be coated with plastic or wax to give some protection against urine damage and seepage. Such containers cannot be reused because they are destroyed by heat sterilization within an autoclave.

The materials suggested above are those known to be in general use. Containers can be custom built in other materials, but it is important to check that the chosen materials will not adversely affect animal health or welfare. Examples of materials to be avoided include certain types of soldered tin, which can be toxic when used to make drinking vessels due to the lead content, or wood that has been treated with toxic preservatives. If containers are to be used on more than one journey, it must be possible to adequately clean and sterilize them.

Wooden containers should be constructed so that the animal cannot bore, claw or bite them open at the seams or joints. All containers should be adequately secured to prevent accidental opening. Nails, bolts, sharp edges or other protrusions on which the animals could injure themselves should be avoided. All slats and uprights should have rounded edges and must be installed so that the animals cannot trap their extremities.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 6: container design and construction

7.2. Substrate, food and water

Substrate or litter should always be provided. It absorbs moisture, provides comfort and security and helps to protect against jolts, vibration and unavoidable temperature changes. It should be clean and of a microbiological standard appropriate to the animals. Commonly used materials include coarse sawdust, wood shavings or shredded paper. The litter must be sufficient to absorb urine and prevent the base of the container from becoming excessively damp. Bedding or nesting material should also be supplied for all species that will benefit from it, especially rodents. Suitable materials are paper strips, straw, paper tissues or any commercially available nesting material that is known to be appropriate for the species, strain and age of animal.

Food and water should only be provided in accordance with the consignor’s instructions. In general, animals should have access to food and water up to the time of packing for dispatch, with the exception of dogs and cats, which should not be fed within 4 h of the start of the journey to permit the stomach to empty of food and therefore reduce nausea and vomiting due to motion sickness. Rabbits and rodents should ideally have food available throughout the journey. Feeding of adult dogs, cats, ferrets and non-human primates can normally be restricted to once per day during transit; however, juveniles and lactating animals may require more frequent feeding and watering. The food should be of the type and microbiological status to which the animals are accustomed.

The law requires that food and water be provided for at least twice the expected journey time. Species requiring water should be provided with water either in leak-proof containers, as a gel, as a wet mash of food, or in the form of fruit or vegetables. If the duration of the journey is greater than 24 h then special feeding, watering and inspection arrangements may be required whilst the animals are in transit.

All water containers must have rounded edges or be adequately covered so that animals do not injure themselves. Unless there are contrary instructions from the shipper, a source of moisture shall be provided, except where not needed by the specific container requirement, at least once every 24 h. Young and lactating animals, minipigs and nonhuman primates may require more frequent watering.

Special recommendations for individual species are given in Part II and they should be considered when planning a journey.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 11: rest, water and feed prior to loading

ETS 193 Article 16: floors and bedding

ETS 193 Article 29: road vehicles or rail wagons on roll-on/roll-off vessels

ETS 193 Article 30: transport by air

7.3. Grouping and stocking density

It is preferable to transport compatible animals in socially harmonious pairs or larger groups. All animals in a container should be from the same established colony, and wherever possible be of similar age and the same sex. Breeding pairs, trios and any offspring should travel in the same container where feasible. However, note that dogs, cats and minipigs should normally travel singly unless they are in compatible same-sex groups, but same sex, compatible nonhuman primates should travel as pairs. Species should never be mixed within the same transport container, especially if they include predators and prey (e.g. rats and mice).

The number of animals within any one container must be such that animals travel in comfort with due regard to the conditions likely to prevail throughout the journey. Guidelines for stocking densities have been prepared for mice and rats, hamsters, guineapigs, rabbits and ferrets (see Part II). Optimum stocking densities for rodents and rabbits are suggested for both non-filtered and filtered crates transported and maintained with full temperature control throughout the journey. Lower stocking densities are also suggested and these are more appropriate for use when all or part of the journey occurs without full temperature control of the shipping crate’s environment.

Relevant legislation:

ETS 193 Article 17: space allowances (floor area and height)

8. Good practice for animal transport on site

This section addresses the movement of animals from one building to another or to new accommodation within a building, e.g. on a different floor. On-site transport may be of short duration, but it can still cause stress (see Section 1) and should be carefully planned with all due consideration for the animals’ experience of the journey. Animals should not be moved within a site unless absolutely necessary and transit times should be as short as possible, avoiding unnecessary delays by good coordination of staff and resources. It is important that high standards of animal care and welfare are maintained at all times, which may include periods of quarantine when moving between buildings with different barrier status.

Arranging the transport should be the responsibility of senior animal care staff and only trained persons should assist in the transfer procedure. Animals in transit should not be left unattended and remain the responsibility of the consignor until they are handed over. It is essential to liaise effectively and in good time with the recipient, to ensure that suitable housing and adequate staff will be ready for the animals on arrival.

All species (apart from dogs in certain circumstances; see below) should be moved within containers secured with appropriate, tamper-proof door catches and locks. Cats, primates and minipigs should be relocated in purpose-made transport containers with secure fastenings, whereas rabbits and rodents can generally be moved whilst still in their home cages, carried on a trolley or other suitable vehicle. Dogs can be moved by a wider range of methods including lead walking or carrying, provided that they are appropriately trained (see Prescott et al. 2004).

For larger animals such as dogs, cats, primates and minipigs, transfer by trolley or cart is an option for relatively short on-site journeys. Noise and vibration can be stressful, so all wheels and hinges should be regularly oiled and wheels should be made of rubber to reduce vibration. The weightbearing surface of the trolley should be non-slip and the trolley should have a lid to prevent animals jumping out. Each trolley or cart should be moved and checked before every journey to ensure that it has been properly maintained. Care should be taken to ensure a slow, gentle journey, taking care not to bump or jolt the trolley.

Longer journeys, or those between buildings, may require the use of specifically designed transport boxes. These are purpose-built containers that are usually moved in a ventilated vehicle. Certain animals may need to be habituated to the container to experience confinement and motion before the journey wherever possible.

However animals have been transported, they should be removed promptly from their transport containers on arrival, checked for good health and placed in the pre-prepared accommodation. Appropriate records, such as individual animal histories and clinical records, should always accompany each animal during the journey to ensure that they stay with the right animals and are not mislaid.

9. Sources of additional advice

The International Air Transport Association Live Animals Regulations and the Animal Air Transportation Association Manual for the Transportation of Live Animals provide advice on requirements for animal shipments and are highly recommended reading for all who transport animals. These publications can be obtained from www.iata.org/ and www.aata-animaltransport.org/ respectively.

Part II Specific requirements for species and other groups

1. Rodents

This document covers laboratory bred and reared rats, mice, hamsters, gerbils and guineapigs. Laboratory rodents should always be transported under SPF conditions, regardless of their microbiological status, to protect them from pathogens carried by any companion animals which may be transported on the same vehicle. Specialist advice should be sought for other, less commonly used rodent species or for wild-caught rodents.

1.1. Design and construction of containers

Materials

The body of the container may be made of cardboard with moisture-resistant coating; moulded plastic (including, but not limited to, polyethylene, polycarbonate or polystyrene); corrugated plastic composite board; laminated plastic composites; fibreglass; or aluminium. Interior surfaces should have a smooth, moisture-resistant, durable surface. Suitable materials for viewing windows are metal wire or transparent sheet plastic (e.g. Mylar). Spun-bonded polyester is recommended for use as filtration medium.

Construction

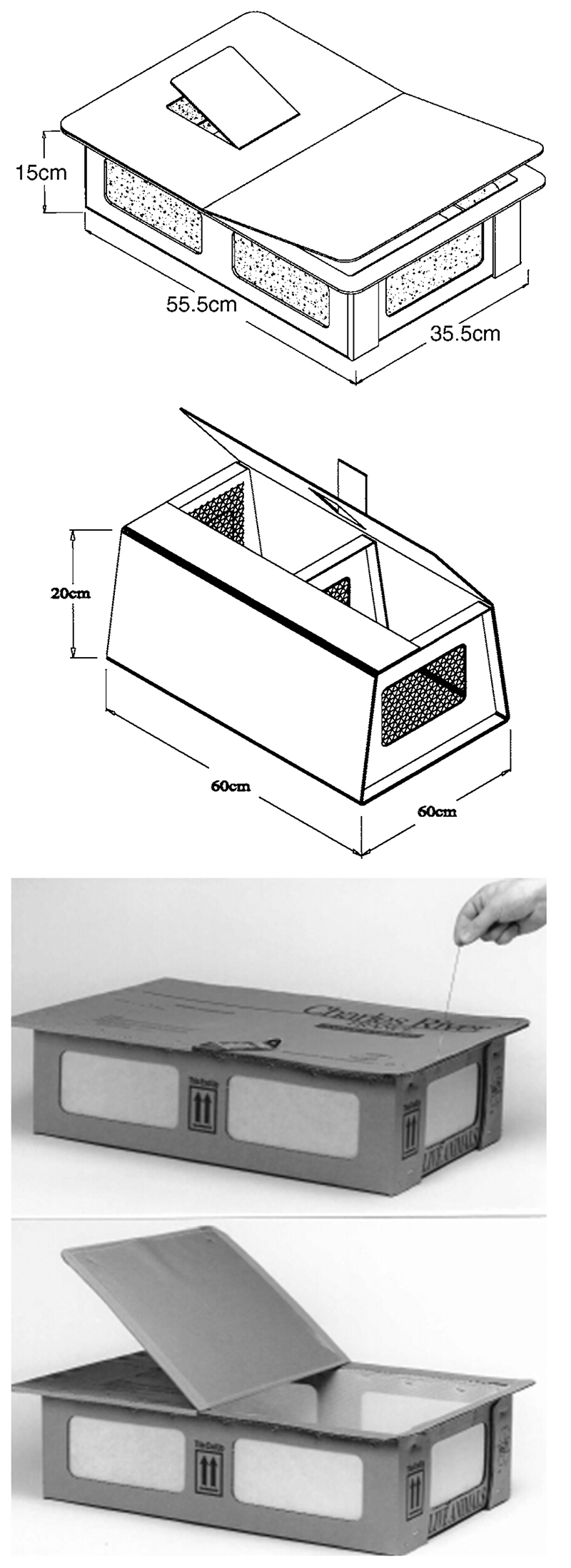

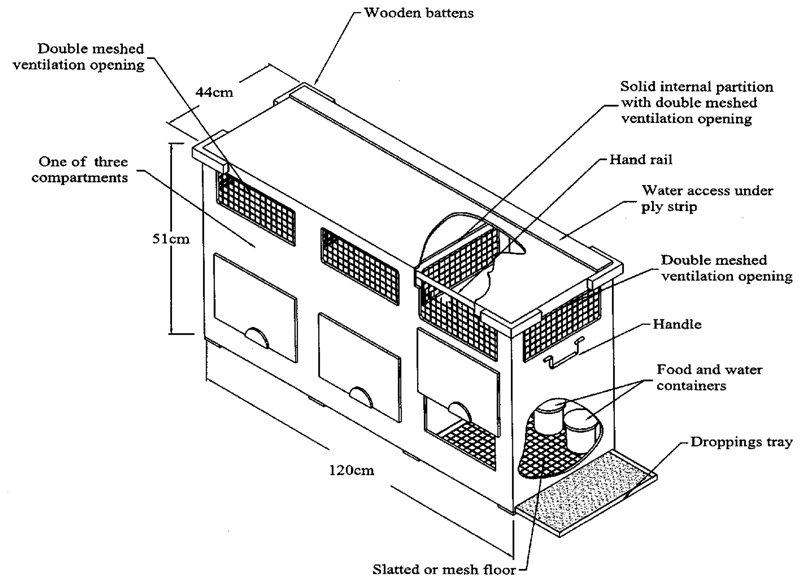

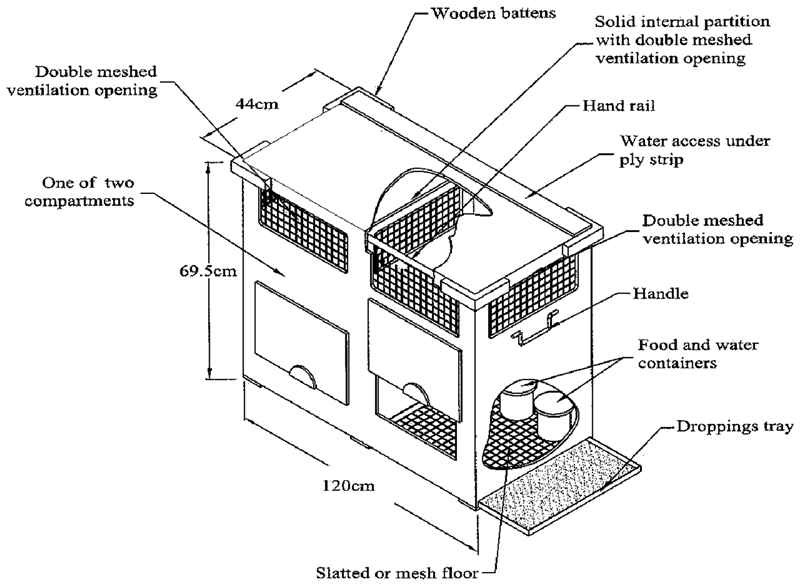

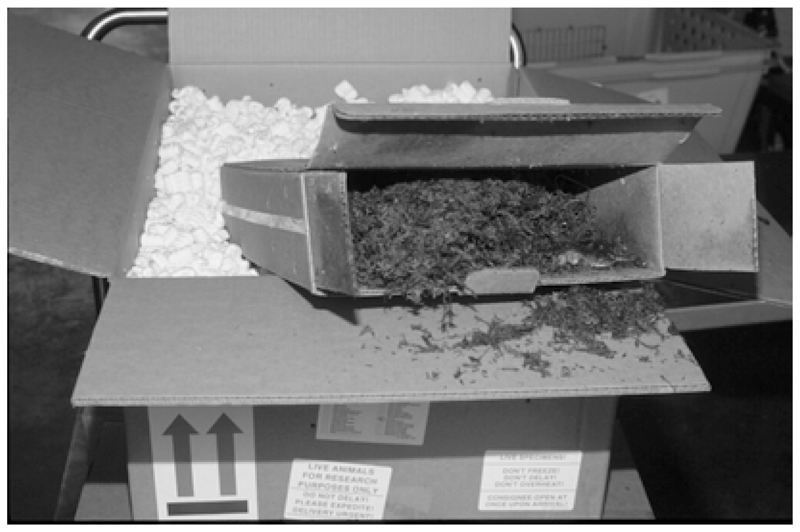

Containers can be constructed for single use or for repeated use, following defined reconditioning practices. SPF containers should be constructed to allow at least eight similarly constructed, fully-loaded containers to be stacked on top of one other without causing damage or crushing the bottom container. Care must be taken to ensure that larger containers have been designed with sufficient structural support. This is especially important in the case of international shipments (see Fig 1). Some SPF shipping containers may consist of one or more primary or inner enclosure(s) and a secondary covering or ‘over shipper’. See Fig 2.

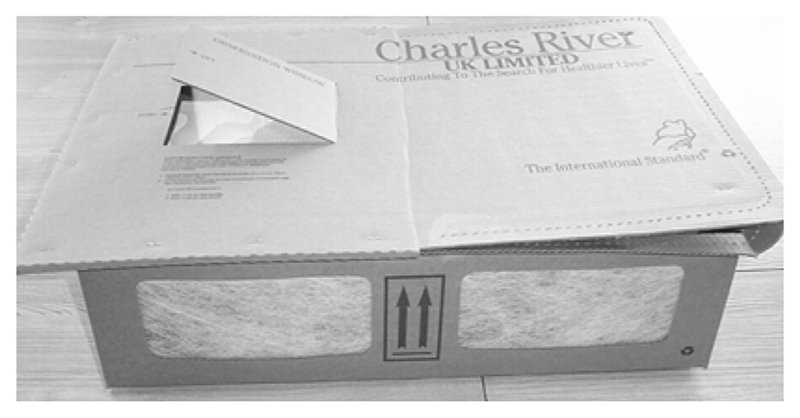

Fig 1. Example of a container for use in international shipments.

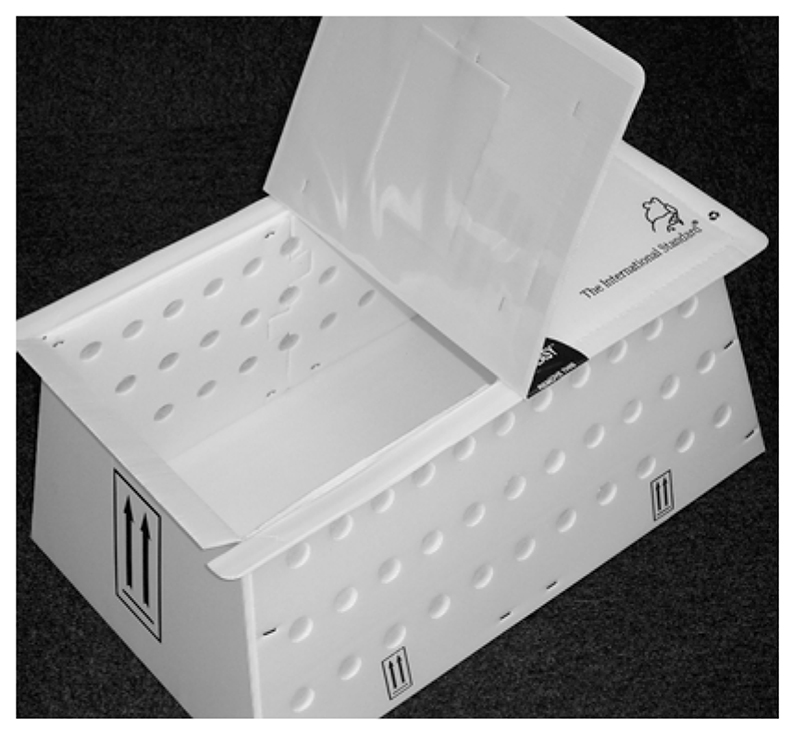

Fig 2. Example of a container for rodents with additional bio-security.

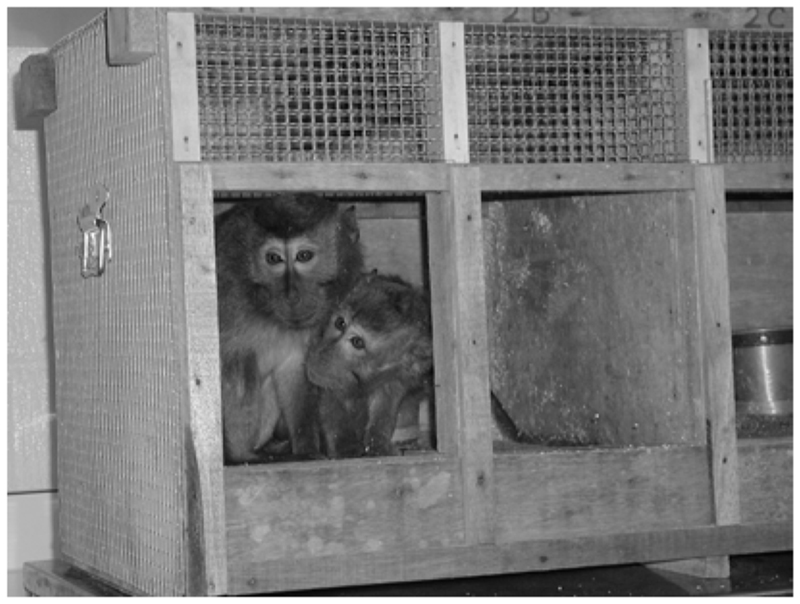

Mice of different strains can be transported within the same container, provided that it is divided into sections to separate them. The physical and environmental conditions and stocking densities within each compartment should conform to the guidelines elsewhere in this report. See Fig 3.

Fig 3. Example of a multi-sectioned container for shipping mice of different strains.

Surfaces should be designed and materials selected so that animals cannot gnaw through the container. For example, this can be achieved by lining the container with fine-meshed screen wire or plastic film, or by using solid, smooth plastic. In the case of hamsters, the entire interior of the container should be lined with at least one (preferably two) layers of screen wire to ensure that they cannot gnaw through the container. Hamsters will readily gnaw free edges of screen wire, unfastened seams, elevated seams or wrinkles in the screen wire, so containers should be checked carefully to make sure that they are sound. The piece of screen wire covering the opening must also be fastened so that the animals do not have access to any free edges.

Wire mesh linings should be covered by an absorbent nesting material or substrate to make the animals more comfortable. Any nesting or substrate material should be nontoxic, generally non-consumable and capable of being disinfected. The amount of material should be sufficient to absorb urine or faeces voided by the animals during the anticipated length of shipment and any spillage from liquid sources placed in the container. As a more comfortable alternative to screen-wire lined cardboard containers, containers appropriately constructed from Correx have proved to be escape-proof.

The container design must allow the contents of the container to be viewed without opening it. One or more viewing windows can be placed in the lid, usually covered with a protective flap made of materials the same as or similar to the rest of the container. See Fig 4. The design must also incorporate spacer bars or other offsets so that when the containers are placed in a stack, ventilation is not compromised by preventing heated air moving vertically upwards and thereby retaining a cooling effect. See Fig 5.

Fig 4. Example of an inspection window for rodent containers.

Fig 5. Examples of containers for rodents.

Ventilation and filters

The placement and type of ventilation openings can vary considerably between shipping containers, but there should always be ventilation apertures on at least three of the walls of the container for effective cross ventilation. The total ventilation area should represent at least 14% of the total combined surface area of the sidewalls.

All filters in the container should be protected from direct animal access by wire mesh or other coverings. Filters should be constructed of water-resistant and tearresistant materials (e.g. spun-bond polyester) to minimize the risk of damage during shipment. Excessive moisture reduces air transfer across filter surfaces, so filters should be sited so that they cannot get wet if it rains, or otherwise protected from rainfall.

Dimensions

The animal(s) must be able to assume all normal postures and to move about freely within the container. There must be adequate space between the highest part of the body and the lid of the container, both to allow adequate air mixing and to prevent contact injuries. Filtered containers restrict ventilation to some degree, which slows down heat dissipation by passive or convective ventilation. This has to be compensated for at elevated ambient temperatures by reducing the number of animals, hence the heat generation, within each container (see Table 3).

Table 3. Minimum stocking density guidelines (cm2 floor area per animal) for rodents.

| Species & weight in g | Floor area cm2 per animal (When no active temperature control is provided throughout the journey) | Floor area cm2 per animal (When active temperature control is provided throughout the journey) |

|---|---|---|

| Filtered crates | ||

| Rats | Min. height 15 cm | Min. height 15 cm |

| < 50 | 120 | 96 |

| 51–75 | 160 | 128 |

| 76–100 | 200 | 160 |

| 101–125 | 240 | 192 |

| 126–150 | 280 | 224 |

| 151–175 | 360 | 288 |

| 176–200 | 360 | 288 |

| 201–225 | 420 | 336 |

| 226–250 | 500 | 400 |

| > 251 | 600 | 480 |

| Mice | Min. height 10cm | Min. height 10cm |

| 10–20 | 120 | 96 |

| 21–25 | 150 | 120 |

| 26–30 | 150 | 120 |

| > 31 | 180 | 144 |

| Hamsters | Min. height 15 cm | Min. height 15 cm |

| 30–60 | 120 | 96 |

| 61–90 | 160 | 128 |

| 91–120 | 200 | 160 |

| > 121 | 240 | 192 |

| Guineapigs | Min. height 15 cm | Min. height 15 cm |

| 100–150 | 330 | 264 |

| 151–250 | 400 | 320 |

| 251–350 | 440 | 352 |

| 351–450 | 480 | 384 |

| 451–550 | 520 | 416 |

| > 551 | 560 | 448 |

| Unfiltered crates | ||

| Rats | Min. height 15 cm | Min. height 15 cm |

| < 50 | 60 | 48 |

| 51–75 | 80 | 64 |

| 76–100 | 100 | 80 |

| 101–125 | 120 | 96 |

| 126–150 | 140 | 112 |

| 151–175 | 180 | 144 |

| 176–200 | 180 | 144 |

| 201–225 | 220 | 176 |

| 226–250 | 253 | 203 |

| > 251 | 300 | 240 |

| Mice | Min. height 10cm | Min. height 10cm |

| 10–20 | 60 | 48 |

| 21–25 | 75 | 60 |

| 26–30 | 75 | 60 |

| > 31 | 90 | 72 |

| Hamsters | Min. height 15 cm | Min. height 15 cm |

| 30–60 | 60 | 48 |

| 61–90 | 80 | 64 |

| 91–120 | 100 | 80 |

| > 121 | 120 | 96 |

| Guineapigs | Min. height 15 cm | Min. height 15 cm |

| 100–150 | 165 | 132 |

| 151–250 | 200 | 160 |

| 251–350 | 220 | 176 |

| 351–450 | 240 | 192 |

| 451–550 | 260 | 208 |

| > 551 | 280 | 224 |

These stocking densities are based on those in guidelines set out by LABA/LASA (1993). They have been re-evaluated using surveys conducted by LABA and input from the Corporation of London Animal Reception Centre at Heathrow Airport. The existing guidelines were found to work well from both animal welfare and practical aspects, and therefore they are largely unchanged.

1.2. Preparations before dispatch

Laboratory rodents should be provided with clean, appropriately disinfected and dry substrate and/or nesting material in the shipping containers. The most commonly used materials are shaved, shredded or chipped wood products, mulched corncobs, or specially prepared chipped or shredded paper products. The primary purpose of this material is to absorb moisture produced by the animals or by any food or water sources in the shipping container. In the case of small rodents, additional nesting material should be used to aid thermoregulation by making nests or burrows. As many rodents huddle in groups to facilitate thermoregulation, animals travelling individually or in small groups should be provided with additional nesting material. Sufficient substrate and nesting material should be provided to keep the interior of the shipping container dry throughout the entire shipping period, but without interfering with ventilation apertures.

1.3. Feeding and watering guide

There are various options for providing food and water to animals being shipped under SPF conditions. Rodents fed on pelleted, dry maintenance diets can be given the same food during transport. The pellets can be soaked in water to form a mash providing both water and nutrients.

Water can be provided in liquid form through water kits (i.e. flexible containers with water accessed via a nipple drinker), but these are prone to flooding when air transport is used due to pressure changes within the cargo compartment. In the case of bio-secure shipping containers, there is usually no means to refill water containers during transit and still maintain the microbiological integrity of the container. Sufficient moisture and food sources must therefore be provided inside the container when the animals are packed. Other moisture sources such as agar or colloid, stabilized water (‘gelled water’) are often used as an alternative. Gelled water products may contain additional nutrients, including energy sources such as simple or complex carbohydrates and stabilizing agents that inhibit spoilage, but they are not nutritionally complete diets.

Emergency feeding and watering during transit

Bio-secure laboratory rodent containers should not be opened under conditions in which microbiological control cannot be assured. Sufficient food and water must be packed with the animals to allow for the double anticipated transit time, so there should be no need to open the container unless a delay exceeds this period. The shipper should be contacted if there is reason to believe that delays will exceed this margin so that alternative arrangements can be made to care for the animals under appropriately controlled conditions. In the event of a delay in departure, the carrier should advise both the consignor and consignee.

Opening containers containing laboratory rodents will invariably compromise the animals’ health or ‘disease free’ status and therefore their use as laboratory animals. In some circumstances it may be necessary to open the containers to prevent or stop animals suffering, even though it would make them unsuitable for research and would mean that they had to be euthanized or rehomed.

1.4. Care and loading

Some SPF shipping containers can accommodate heating or cooling packs or other temperature-altering devices, but these can be unreliable and can also contain chemicals that can be classified as dangerous goods.

1.5. Effect of phenotype and health status

The phenotypic effects of inbreeding, genetic mutation or modification, age and health status can all have an impact on a rodent’s ability to withstand transport stress. Inbred animals, or those with a harmful genetic mutation, are less able to withstand the rigours of transport. It is vitally important for animals such as these to make sure that there are effective contingency plans to cope with likely delays.

Genetically-modified animals can have special requirements and wide consultation may be required when planning their journey (see Section 4.1, Robinson et al. 2003). Low stocking densities may be necessary for obese and pregnant animals because their ability to dissipate body heat can be limited. Pregnant rodents should not be transported during the last 20% of gestation (see Table 1).

2. Rabbits and ferrets

2.1. Design and construction of containers

Materials

The following materials are suitable for containers for transporting rabbits or ferrets: sheet metal; fibreglass; fibreboard; rigid plastic; strong, welded wire mesh; or wood lined with wire mesh. See Fig 6.

Fig 6. Example of a container for specific pathogen free (SPF) rabbits.

Principles of design

Rabbits are usually transported singly or in divided boxes. Stocking density guidelines are given in Table 4.

Table 4. Minimum stocking density guidelines (cm2 floor area per animal) for rabbits and ferrets.

| Rabbits & ferrets | Min height 20 cm | Min height 20 cm |

|---|---|---|

| Filtered crates | ||

| 600–1000 | 1000 | 800 |

| > 1001 | 2000 | 1600 |

| Unfiltered crates | ||

| 600–1000 | 500 | 400 |

| 1001–2500 | 762 | 610 |

| > 2501 | 1000 | 800 |

In addition to the general container requirements (see Section 7), there are other important principles of design that need to be met.

Container height should be restricted for rabbits to prevent back injury caused by kicking out.

For long journeys, it may be necessary to incorporate a grid floor or area for rabbits to separate excreta from the lying area.

Containers constructed without a wire mesh liner must provide wire-screening cover on all air vents.

The current IATA Live Animals Regulations include details of appropriate container design and construction for rabbits and ferrets. Dog and cat pet carriers can be used where filtered ventilation is not required.

2.2. Feeding and watering guide

Rabbits or ferrets should not require feeding for 24 h following packing, but provisions for feeding and watering must be supplied for journeys exceeding 24 h. Rabbits rarely eat or drink during a journey, but food and water should still be provided in case of long journeys, delays or unexpected stop-over (rest) periods. If feeding is necessary due to an unforeseen delay, rabbits should be given carrots, fruit, hay or grain and ferrets should be given tinned cat or dog food.

3. Dogs and cats

3.1. Design and construction of containers for dogs

Materials

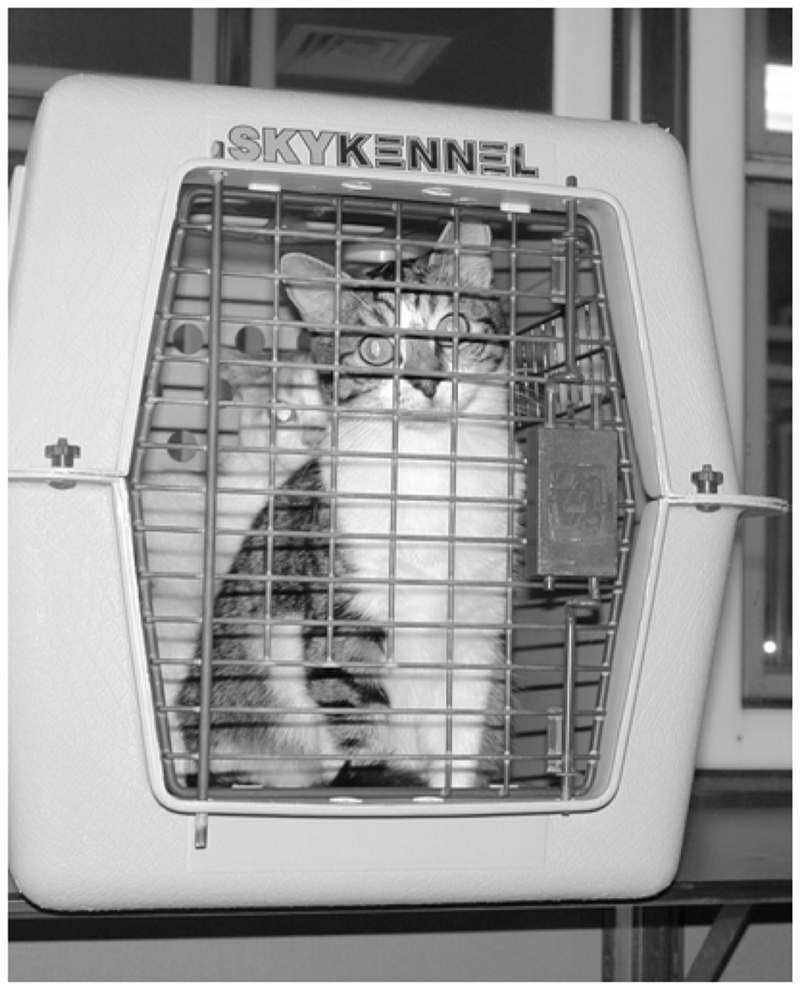

The use of fibreglass or plastic containers, designed to comply with IATA recommendations, is recommended. These are in common use for transporting companion animals and are readily available. See Figs 7 and 8. Modern, impermeable materials such as fibreglass have largely superseded wood for dog container construction; in any case, wooden containers are not suitable for large dogs because they are less robust and heavier than fibreglass or plastic containers of similar size. Also note that some airlines may not accept wooden containers.

Fig 7. Example of a typical Sky kennel used for dogs and cats.

Fig 8. Example of a container for dogs.

Construction

Containers should be constructed with a strong framework, with joints and corners designed so that the animals cannot claw or bite through them. Access to the container should be by a sliding or hinged door that is securely attached and can be adequately secured, e.g. with twisted wire or plastic ties, to prevent accidental opening or escape. It is common practice to construct the door using bars, welded mesh, or smooth expanded metal to enable adequate inspection of the dogs during transport and to provide good ventilation.

Ventilation

Ventilation holes 2.5 cm wide must also be provided over the whole surface of the opposite end to the door, with a distance of 10 cm between the centres of adjacent holes. Similar holes must be provided on the upper third of the remaining two sides. The total ventilated area must provide a minimum of 16% of the total surface area of all four sides. These are minimum requirements and it is permitted to have additional ventilation holes on the top or sides or larger ventilation openings covered with wire mesh if necessary. It should be impossible for the animal to protrude its nose, paws or tail outside the container through any opening, including ventilation holes.

Loose housing

Dogs are generally transported in individual, purpose-designed containers, particularly for longer journeys. However, transporting dogs in established, compatible groups can reduce transport stress and improve welfare. Dogs may travel loose in small, single-sexed, compatible groups by road, in the cargo area of a suitably equipped vehicle with an inner door system constructed of wire mesh and wood or metal framing. Absorbent substrate must be provided and the supply of food and water should be incorporated into the design. There should be sufficient space to allow the dogs to stand, turn, lie down and stretch.

3.2. Design and construction of containers for cats

Materials

Suitable materials are rigid plastic or fibreglass.

Principles of design