Abstract

Mono-axial functionalised octahedral diazido Pt(iv) complexes trans, trans, trans-[Pt(py)2(N3)2(OR1)(OR2)] (OR1 = OH and OR2 = anticancer agent coumarin-3 carboxylate (cou, 2a), pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) inhibitors 4-phenylbutyrate (PhB, 2b) or dichloroacetate (DCA, 2c)), and their di-axial functionalised analogues with OR1 = DCA and OR2 = cou (3a), PhB (3b), or DCA (3c) have been synthesised and characterised, including the X-ray crystal structures of complexes 2a, 3a, 3b and 3c. These complexes exhibit dark stability and have the potential to generate cytotoxic Pt(ii) species and free radicals selectively in cancer cells when irradiated. Mono-functionalised complexes 2a–2c showed higher aqueous solubility and more negative reduction potentials. Mono- and di-functionalised complexes displayed higher photocytotoxicity with blue light (1 h, 465 nm, 4.8 mW cm–2) than the parent dihydroxido complex 1 (OR1 = OR2 = OH) in A2780 human ovarian (IC50 0.9–2.9 μM for 2a–2c; 0.11–0.39 μM for 3a–3c) and A549 human lung cancer cells (5.4–7.8 μM for 2a–2c; 1.2–2.6 μM for 3a–3c) with satisfactory dark stability. Notably, no apparent dark cytotoxicity was observed in healthy lung MRC-5 fibroblasts for all complexes (IC50 > 20 μM). Significantly higher platinum cellular accumulation and photo-generated ROS levels were observed for the di-functionalised complexes compared with their mono-functionalised analogues when cancer cells were treated under the same concentrations.

Introduction

Octahedral Pt(iv) complexes with low-spin 5d6 configurations are generally very stable, but can often be activated by bio-reductants in vivo (e.g. GSH, ascorbic acid, and cysteine residues) to give the corresponding more reactive Pt(ii) drugs.1–3 The Pt(iv) drugs iproplatin,4,5 ormaplatin,6 satraplatin7 and LA-128 have entered clinical trials, but none has yet received clinical approval.9 A problem for Pt(iv) drugs, which are activated by chemical reduction in the body, is that the extent and cell selectivity of activation are difficult to control since they rely on natural processes.2,3 The use of localised light to control the activation of Pt(iv) prodrugs might overcome this problem.10–12

In contrast to Pt(iv) complexes which exert their cytotoxicity via chemical reduction, photoactive Pt(iv) complexes require higher dark stability and resistance to bio-reductants to guarantee that these prodrugs reach cancer cells and can be selectively photoactivated there.2,10–14 Trans, trans, trans-[Pt(py)2(N3)2(OH)2] (1) is a promising photoactive diazido Pt(iv) complexes that exhibits high dark stability and photoactivation upon visible light irradiation.15 The axial ligands of Pt(iv) complexes can be released during reduction, and greatly affect the reduction potential of Pt(iv).16,17 in general, Pt(iv) complexes with axial hydroxide ligands exhibit higher dark stability than those with other axial ligands.18,19 However, Pt(iv) prodrugs with bioactive axial ligands can selectively target cancer cells and attack several cellular components at the same time, providing a multi-targeted mechanism of action, which can result in enhanced anticancer potency and circumvention of cisplatin resistance.3,20,21 Here, conjugates of 1 with various anticancer drugs and cancer-targeting vectors as axial substituents have been investigated. Related reported complexes mostly have only one axial position derivatised and retain one hydroxide ligand to stabilise the Pt(iv) and increase aqueous solubility.10 Only one di-functionalised photoactive trans-diazido Pt(iv) complex with different functional ligands appears to have been reported so far.22

The formation of esters via reactions of carboxylic acids and an axial hydroxide ligand in Pt(iv) complexes is a promising strategy for the development of multifunctional drugs.3,10 in this work, anticancer agent coumarin-3 carboxylate (cou), pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) inhibitor 4-phenylbutyrate (PhB) and dichloroacetate (DCA) were conjugated to diazido Pt(iv) complex 1 to generate mono-functionalised complexes 2a–2c, which were further modified with a DCA ligand to give di-functionalised complexes 3a–3c (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic routes for photoactive diazido Pt(iv) complexes 2a–2c and 3a–3c. (i) cou/PhB acid, TBTU, DIPEA, DMF, N2, RT, overnight; (ii) DCA anhydride, DMF, N2, RT, overnight.

Coumarin and derivatives containing a benzopyrone target a number of pathways in cancer cells (e.g. kinase inhibition, cell cycle arrest, and angiogenesis inhibition) and have been widely used as anticancer agents.23–27 Coumarin derivatives can act as an antenna for light-harvesting when conjugated to metal complexes, and therefore enhance the fluorescence quantum yield and lengthen their emission lifetimes.28 PDK inhibitor PhB can suppress aerobic glycolysis, reverse the Warburg effect, and eventually kill cancer cells.29 In addition, PhB also acts as a weak extracellular histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor.29,30 DCA is frequently tagged on to anticancer metal complexes for its mitochondrial targeting and PDK-inhibiting properties.29,31 The di-DCA Pt(iv) complex mitaplatin is activated by chemical reduction and then (i) liberates Pt(ii) species that can attack nuclear DNA and (ii) DCA that can attack mitochondria, giving rise to notable selectivity towards cancer cells.31 The combination of DCA and other functional substituents in a Pt(iv) complex can result in significantly improved cytotoxicity. 3,22,29,31,32

Photoactive complexes 2a–2c and 3a–3c with the general formula trans, trans, trans-[Pt(py)2(N3)2(OR1)(OR2)] have been synthesised and characterised, and the X-ray crystal structures of 2a, 3a, 3b and 3c were determined. The reduction potentials, dark stability and photodecomposition, photoreactions with 5′-GMP, photocytotoxicity and cellular accumulation are compared between mono-functionalised 2a–2c, di-functionalised 3a–3c, and unfunctionalised parent complex 1.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterisation

The synthetic routes for photoactive Pt(iv) complexes 2a–2c and 3a–3c are summarised in Scheme 1. Mono-functionalised complexes 2a and 2b were obtained by combining parent complex 1 with the corresponding acid using TBTU as a coupling agent. The bi-functionalised complexes 3a and 3b were synthesised by stirring 2a and 2b with dichloroacetic anhydride, respectively, while 2c and 3c were made by reacting 1 directly with dichloroacetic anhydride. Complexes 2a–2c and 3a–3c are air-stable at 298 K in the solid state in the dark. Dark stability was observed for 2a–2c in RPMI-1640 cell culture medium by UV-vis spectroscopy (Fig. S1, ESI†). Complexes 3a–3c showed poor aqueous solubility, but were stable in DMSO (Fig. S1, ESI†). The dark stability of complexes 2a and 3a in the presence of 2 mM GSH was confirmed by UV-vis spectroscopy (Fig. S2, ESI†). All complexes were characterised by ESI-HR-MS, NMR and UV-vis spectroscopy and their purity was determined by HPLC as >95% (Fig. S3–S16, ESI†).

All observed m/z values and the isotopic mass distribution patterns for Pt and Cl match well with calculated HR-MS spectra (Fig. S4, ESI†). All 1H and 13C NMR spectra are in agreement with the proposed structures for the complexes (Fig. S5–16, ESI†). The Pt-coordinated pyridine can be identified by 1H NMR doublets with 195Pt satellites at ca. 9.0 ppm, and the triplets at ca. 8.1 and 7.7 ppm and by 13C NMR resonances at ca. 150, 142 and 126 ppm assignable to the α, γ and β C–H groups, respectively, of pyridine. The electronic absorption spectra of complexes 2a–2c and 3a–3c are similar to that of parent complex 1 with a maximum absorption band at ca. 300 nm (ε ca. 17 000 M–1 cm–1) assignable to LMCT (N3 → Pt) transitions. The extinction coefficients of 2a and 3a at ca. 300 nm (ε ca. 31 000 M–1 cm–1) are much higher due to the presence of the coumarin moiety.

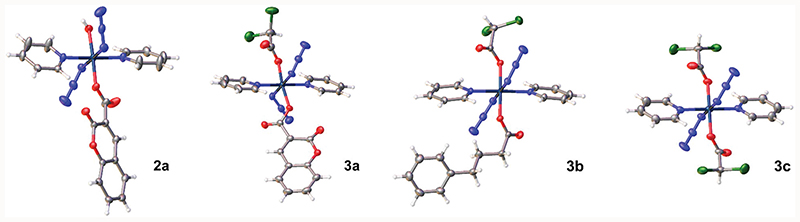

X-ray crystallography

Crystals of complexes 2a, 3a, 3b and 3c suitable for X-ray diffraction studies were obtained through evaporation, or diffusion of diethyl ether into DCM/MeOH solutions. The perspective drawings of complexes 2a and 3a–3c are shown in Fig. 1. The crystallographic data are summarised in Table S1 (ESI†) and selected bond distances and angles are listed in Tables 1 and S2 (ESI†). Complexes 2a, 3b and 3c crystallised in the triclinic space group, while complex 3a crystallised in the trigonal space group. These complexes show similarities in the equatorial plane defined by four nitrogen atoms, two from the trans pyridine molecules and two from the trans azide anions, and resemble typical equatorial planes in their analogues.15 With azide-Pt bond angles of ca. 116°, the plane contains only the bound nitrogens of the azide ligands with the remainder of the azide ligands projected out on opposite faces of the plane. The difference lies in the axial ligands. Complex 2a is mono-functionalised with an O-bound coumarin-3 carboxylate and a trans hydroxide ligand (O–Pt–O bond angle of 175.13 (6)°), which forms a moderately strong hydrogen bond with OH in an adjacent molecule (O3–H3B⋯O3, Table S3, ESI†). For complex 3c with two dichloroacetate ligands, the Pt sits on a crystallographic inversion centre, while complexes 3a and 3b exhibit distortions from ideal octahedral geometry, with trans O–Pt–O bond angles smaller than 180° (171.97(12)° for 3a, and 178.76(10)° for 3b). The Pt–O bond distance is 2.005(3) Å for the coumarin-3 carboxylic acetate in complex 3a and 1.992(3) Å for 4-phenylbutyrate in 3b. These distances are slightly shorter than the Pt–O bond lengths for their respective dichloroacetate ligands (2.020(3) and 2.016(3) Å).

Fig. 1. X-ray crystal structures of mono-functionalised 2a and di-functionalised 3a, 3b, and 3c, with thermal ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability level.

Table 1. Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°) for 2a and 3a .

| Complex 2a | Complex 3a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1–O3 | 1.9753(17) | Pt1–O19 | 2.020(3) |

| Pt1–N25 | 2.049(2) | Pt1–N13 | 2.045(4) |

| Pt1–N28 | 2.044(2) | Pt1–N16 | 2.058(4) |

| Pt1–O1 | 2.0289(16) | Pt1–O24 | 2.005(3) |

| Pt1–N13 | 2.033(2) | Pt1–N1 | 2.040(3) |

| Pt1–N19 | 2.025(2) | Pt1–N7 | 2.028(3) |

| N25–N26 | 1.212(3) | N13–N14 | 1.211(5) |

| N26–N27 | 1.139(3) | N14–N15 | 1.147(5) |

| N28–N29 | 1.209(3) | N16–N17 | 1.222(5) |

| N29–N30 | 1.147(3) | N17–N18 | 1.148(6) |

| O1–Pt1–O3 | 175.13(6) | O19–Pt1–O24 | 171.97(12) |

| N13–Pt1–N19 | 178.33(8) | N1–Pt1–N7 | 179.26(15) |

| N25–Pt1–N28 | 179.07(8) | N13–Pt1–N16 | 178.49(14) |

| N26–N25–Pt1 | 116.89(17) | N14–N13–Pt1 | 116.0(3) |

| N25–N26–N27 | 174.3(3) | N13–N14–N15 | 175.2(5) |

| N29–N28–Pt1 | 117.37(18) | N17–N16–Pt1 | 114.9(3) |

| N28–N29–N30 | 174.6(3) | N16–N17–N18 | 175.2(4) |

| CI23–C21–CI22 | 112.1(3) | ||

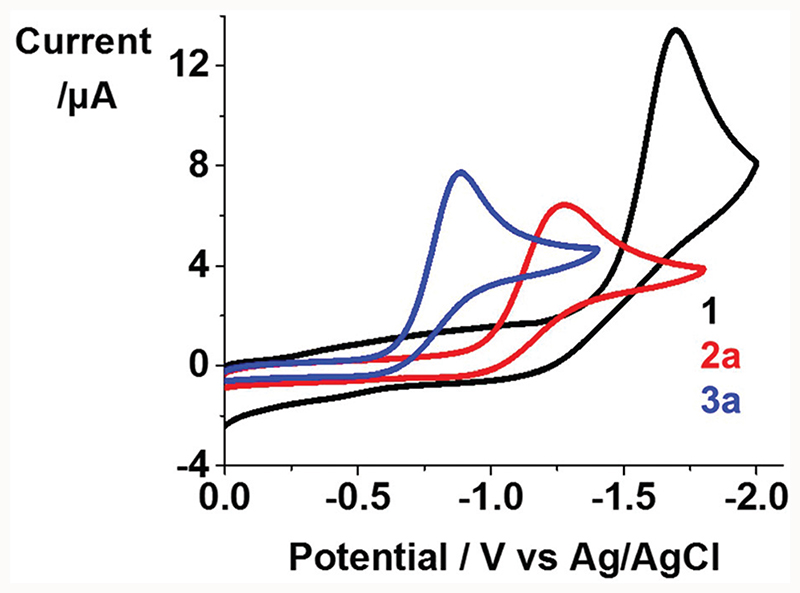

Cyclic voltammetry

Cyclic voltammograms for 1, 2a and 3a were acquired in the potential range –1.8–0.0 V in DMF at 298 K, using 0.1 M NBu4PF6 as supporting electrolyte (Fig. 2). An irreversible reduction wave assigned to PtIV/PtII was observed with E pc of –1.699, –1.285 and –0.886 V for 1, 2a and 3a, respectively. it is notable that Pt(iv) complexes with the more unmodified hydroxide axial ligands (OH) exhibit more negative reduction potentials, consistent with the ability of axial hydroxide to stabilise these Pt(iv) complexes.18,19 The irreversible reduction waves suggest that these complexes release ligands during reduction, as observed upon irradiation where cytotoxic species are released as a result of photoreduction.

Fig. 2. Cyclic voltammograms for complexes 1, 2a and 3a (1 mM) in 0.1 M NBu4PF6-DMF (deaerated under N2).

Photoactivation and radical formation

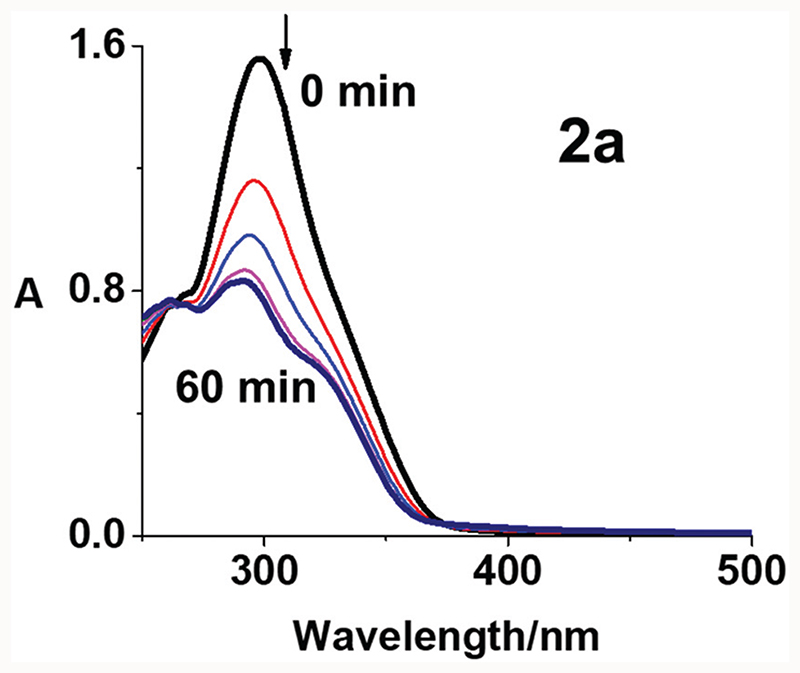

The photodecomposition of complexes 2a–2c in RPMI-1640 ceII culture medium with 5% DMSO (used for solubilisation during cytotoxicity screening) and 3a–3c in DMSO was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy at different time intervals after irradiation with blue light (420 nm) at 298 K (Fig. 3, S17 and S18, ESI†). Fig. 3 shows the decrease in absorbance maximum of complex 2a at 298 nm, assigned as a LMCT band (N3 → Pt). The decrease was rapid over the first 15 min and showed no significant further change after 30 min, suggesting release of the azide ligands. Similar results were obtained using mono-functionalised 2b and 2c (Fig. S17, ESI†), consistent with previously published data for complex 1.15 Notably, the photodecomposition of di-functionalised 3a–3c in DMSO was complete in 10 min with blue light irradiation (Fig. S18, ESI†). The incorporation of the coumarin-3 carboxylate provides the possibility of using complex 2a in fluorescence emission spectroscopic studies. Even though coumarin-3 carboxylic acid exhibited no apparent fluorescence in aqueous solution with excitation at 405 nm, it can exhibit switched-on blue fluorescence (ca. 450 nm) in the presence of OH∂, owing to the generation of fluorescent 7-hydroxycoumarin-3 carboxylic acid (pK a = 1.98).33 While no apparent fluorescence was observed before irradiation, 2a exhibited emission centred at ca. 440 nm after irradiation with blue light (420 nm, 20 min) at 298 K (Fig. S19, ESI†). This emission can be attributed to the formation of 7-hydroxycoumarin-3 carboxylate from coumarin-3 carboxylate and OH• radicals as photoproducts of 2a which contains coumarin-3 carboxylate and hydroxide ligands. In contrast, no emission was detected for 3a (which has no hydroxide ligands) under the same irradiation conditions. However, 7-hydroxycoumarin-3 carboxylate was not detected by LC-MS (Table S4, ESI†).

Fig. 3.

Photochemical decomposition of mono-functionalised Pt(iv) complex 2a (50 μM) in phenol red-free RPMI-1640 cell culture medium with 5% DMSO (v/v) upon irradiation with blue light (420 nm, 1 h) at 298 K.

The photoproducts from complex 2a irradiated in aqueous solution were investigated by LC-MS. Only a HPLC peak assigned to 2a was observed before irradiation, indicating the high purity of the complex (>99%). This peak disappeared within 20 min of irradiation with blue light (420 nm, Fig. S20, ESI†). The peak assigned to {PtIV(py)2(N3)(OH)(cou)}+ (601.18 m/z, peak f in Fig. S20 and Table S4, ESI†) increased in intensity up to 5 min, and thereafter decreased in 5–30 min with a concomitant increase in intensity of peaks for the photoproducts [2{PtII(py)(OH)2(HCOO)} + 3Na]+ (774.99 m/z, a), {PtII(py)(cou)(CH3CN)2}+ (545.10 m/z, b), {PtIII(py)2(HCOO) (N3)}+ (440.07 m/z, c), {PtII(py)2(N3)(CH3CN)}+ (436.08 m/z, d), [{PtII(py)2(N3)2} + Na]+ (460.08 m/z, g), [{PtII(py)(cou)(HCOO) (N3)} + 2H]+ (552.05 m/z, h), and coumarin-3 carboxylic acid (191.29 m/z, e Fig. S20 and Table S4, ESI†). The formic acid and acetonitrile ligands arise from the mobile phase in LC-MS. The photodecomposition of 2a is complicated. In general, one azide ligand appears to be released from Pt(iv) complexes first to form {PtIV(py)2(N3)(OH)(cou)}+ (601.18 m/z, f), which can then liberate the other azide or the axial ligand (OH or cou) to form Pt(ii) species. When the irradiation time increased, some Pt(ii) species underwent further release of both axial ligands.

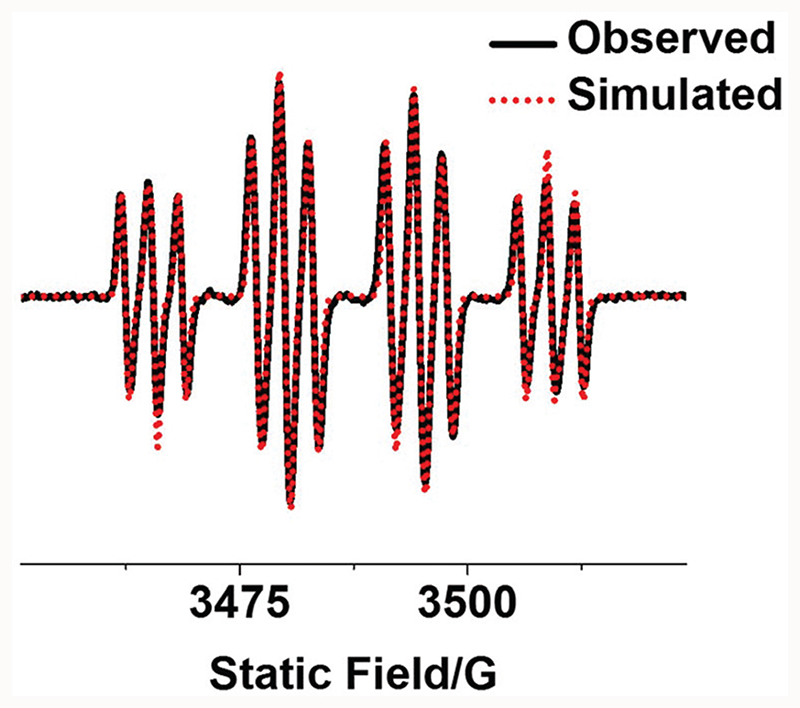

Reactive radicals released by photo-irradiated complex 2a in aqueous solution were detected by EPR using the spin-trap 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO, Fig. 4). The EPR spectra for 2a showed no signal in the absence of irradiation, while a 1: 2 : 2 : 1 quartet of triplet peaks assigned as DMPO-N3 • and a quartet signal as DMPO-OH• were detected after irradiation (463 nm). Hence the EPR results suggest the formation of OH• and N3 • radicals after irradiation (50 min).

Fig. 4.

Observed (black) and simulated (red) EPR spectra of mono-functionalised complex 2a (2.5 mM) with an axial coumarin in aqueous solution with 5% DMSO showing the formation of DMPO-N3 • and DMPO-OH• adducts after irradiation (463 nm). The experimental trace is the accumulation of 300 scans with continuous irradiation (465 nm, 50 min). Parameters for simulation: DMPO-N3 • (g = 2.00595, , and ); DMPO-OH• (g = 2.00592, , and .34

Photoreaction with 5′-GMP (guanosine 5′-monophosphate)

The photoreaction was carried out by irradiating an aqueous solution of complex 2a (30 μM) in the presence of 2 mol equiv. of 5’-GMP with blue light (420 nm) at 310 K without prior incubation, and was monitored by LC-MS at different time intervals (Fig. S21, ESI†). The major photoproduct of the reaction was assigned as {PtII(CH3CN)(py)2(GMP-H)}+ (756.16 m/z, G1), which increased in concentration with the irradiation time. Pt-GMP adducts {PtII(HCOO)(py)2(GMP)}+ (762.10 m/z, G2) and {PtII(N3)(py)2(GMP)}+ (758.16 m/z, G3) were also detected (formic acid and acetonitrile arise from the HPLC mobile phase). Notably, the major Pt-GMP adducts generated by 2a are the same as those for 1 and its derivatives, indicating that the axial substituents do not affect the interaction between guanine and the platinum centre upon irradiation.15,34

Photocytotoxicity and cellular accumulation studies

The photocytotoxicity of complexes 2a–2c and 3a–3c was determined in A2780 ovarian and A549 lung cancer cells, after 1 h drug incubation, 1 h irradiation (465 nm, 4.8 mW cm–2) and 24 h recovery (Table 2). Their dark cytotoxicity was also determined after 2 h incubation and 24 h recovery in A2780 and A549 cancer cells, as well as MRC-5 normal lung fibroblasts for comparison. Due to the poor aqueous solubility of these compounds, DMSO was used to facilitate their dissolution. Even though DMSO is a strong ligand for Pt(ii), no Pt-DMSO adduct was detected during irradiation (Table S4, ESI†). Also, due to the low DMSO concentration (<0.5%) and short incubation time (1 h in the dark and 1 h irradiation), DMSO did not exhibit significant effects on the cytotoxicity of these complexes.

Table 2.

IC50 values and photocytotoxicity indices (PI) for mono-functionalised complexes 2a–2c and di-functionalised 3a–3c for A2780 ovarian and A549 lung cancer cells, and MRC-5 normal lung fibroblasts (1 h incubation, 1 h irradiation (465 nm), followed by 24 h recovery). Data for unfunctionalised complex 1 are listed for comparison34

| Complex | IC50 a (μM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2780 | A549 | MRC5 | ||

| 2a | Darkb | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| Irrad | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.1 | ||

| PI | >34 | >12 | ||

| 2b | Dark | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| Irrad | 0.92 ± 0.07 | 5.44 ± 0.05 | ||

| PI | >108 | >18 | ||

| 2c | Dark | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| Irrad | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 1.1 | ||

| PI | >83 | >15 | ||

| 3a | Dark | 1.9 ± 0.1 | >50 | >50 |

| Irrad | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | ||

| PI | 17.3 | >19 | ||

| 3b | Dark | 1.3 ± 0.2 | >20 | >20 |

| Irrad | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | ||

| PI | 8.7 | >16 | ||

| 3c | Dark | 1.9 ± 0.3 | >20 | >20 |

| Irrad | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | ||

| PI | 4.9 | >10 | ||

| 1 | Dark | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| Irrad | 7.1 ± 0.4 | 51.9 ± 2.5 | ||

| PI | >14 | >1.9 | ||

Each value is the mean of two independent experiments ± standard deviation.

Dark cytotoxicity was determined after 2 h incubation and 24 h recovery.

The IC50 values determined by the sulforhodamine B (SRB) colorimetric assay are summarised in Table 2. Mono-functionalised Pt(iv) complexes 2a–2c were non-toxic in the dark with IC50 values >100 μM, while di-functionalised Pt(iv) complexes 3a–3c were cytotoxic to A2780 ovarian cancer in the dark (IC50 values of 1.3–1.9 μM), but relatively non-toxic to A549 lung cancer and normal MRC-5 lung cells (IC50 values >20 μM). The selective toxicity towards ovarian cancer cells might be an advantage for use of these complexes as phototherapeutic prodrugs for topical application, especially considering their low cytotoxicity towards normal MRC-5 cells.

The photocytotoxicity of mono-functionalised complexes 2a–2c in A2780 ovarian cancer cells (IC50 values of 0.9–2.9 μM) was >2.4× higher than that of unfunctionalised 1 (7.1 μM), and in A549 lung cancer cells (IC50 values of 5.4–7.8 μM) was >6.6× higher than that of 1 (51.9 μM). Moreover, di-functionalised Pt(iv) complexes 3a–3c (IC50 values of 0.11–0.39 μM for A2780; 1.2–2.6 μM for A549) showed >3× enhanced photocytotoxicity compared with their mono-functionalised analogues 2a–2c in both of the cancer cell lines tested. Notably, similar photocytotoxicity indices (PI) were found for mono-functionalised 2a–2c and di-functionalised 3a–3c in lung A549 cancer cells (Table 2), while >2–17× higher PI values were determined for 2a–2c compared to their corresponding di-functionalised analogues in ovarian A2780 cancer cells, although 3a–3c showed significantly higher photocytotoxicity in A2780 cells.

The cellular accumulation of complexes 2a–2c and 3a–3c was determined in A2780 ovarian cancer cells, and that of 2a and 3a also for A549 lung cancer cells at the same concentration (2 μM, Table 3). Mono-functionalised complexes exhibited >19× higher accumulation than unfunctionalised 1, and significantly higher cellular accumulation was observed for di-functionalised complexes compared to the corresponding mono-functionalised analogues (ca. 3–18×, Table 3). The lipophilicity (based on the reversed-phase HPLC retention time) has a major influence on cellular Pt accumulation, following the trend: di-functionalised 3a–3c > mono-functionalised 2a–2c > unfunctionalised 1 (Table 3). This trend matches that for photocytotoxicity well: di-functionalised 3a–3c > mono-functionalised 2a–2c > unfunctionalised 1. These results suggest that the extent of cellular accumulation of these Pt(Iv) prodrugs plays an important role in their antiproliferative potency.

Table 3.

Cellular accumulation of Pt in A2780 cells and A549 cells after exposure to unfunctionalised 1, mono- and di-functionalised complexes 2a–2c and 3a–3c, respectively (2 μM, 1 h, in the dark)

| Cell | Complex | Pta (ng per 106 cells) |

|---|---|---|

| A549 | 1 | 0.51 ± 0.03*** |

| 2a | 9.8 ± 2.1* | |

| 3a | 36.1 ± 1.5*** | |

| A2780 | 1 | 0.16 ± 0.02* |

| 2a | 6.2 ± 0.5** | |

| 2b | 3.5 ± 0.4*** | |

| 2c | 10.8 ± 0.3*** | |

| 3a | 90.9 ± 12.0*** | |

| 3b | 61.4 ± 5.0*** | |

| 3c | 53.8 ± 1.9*** |

All data were determined from triplicate samples and their statistical significance compared to untreated cells evaluated by a two-tail t-test with unequal variances. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

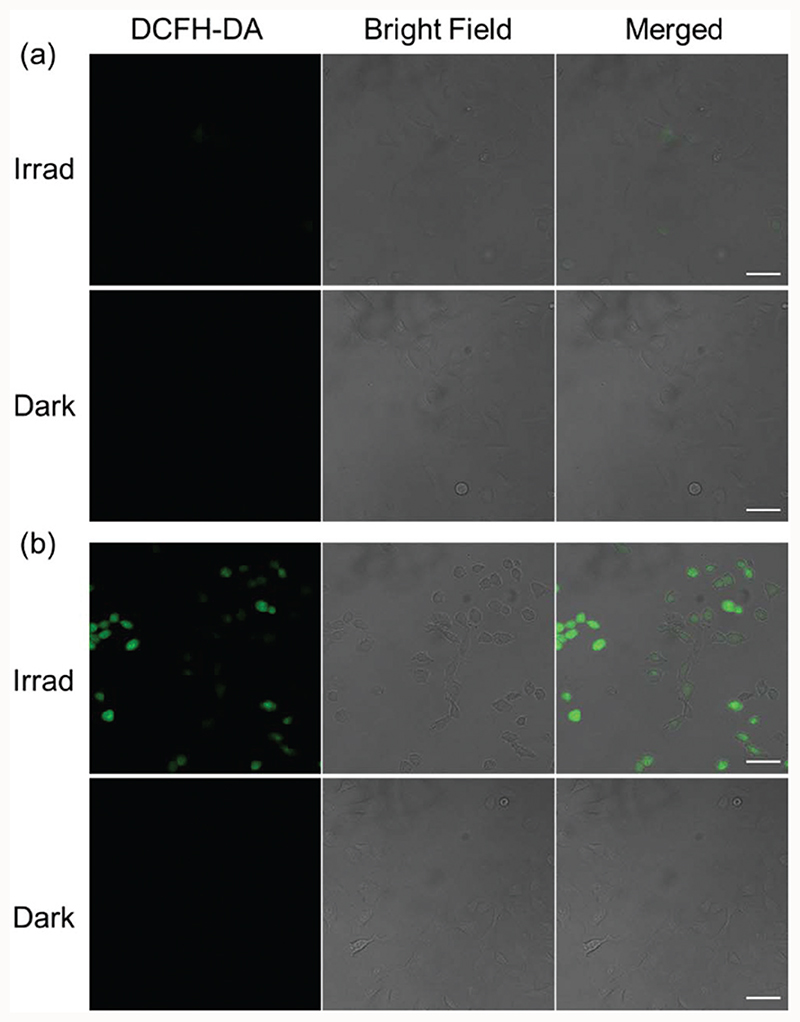

Cellular ROS generation

Since mitochondrial-targeting DCA can suppress aerobic glycolysis and increase mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and ROS production,35 the cellular ROS levels in A549 cells treated with mono-DCA complex 2c or di-DCA complex 3c were determined by the DCFH-DA assay (Fig. 5). DCFH-DA is a cell-permeable non-fluorescent probe that is converted to the highly fluorescent dye DCF upon oxidation by ROS in cells.36 As expected, A549 lung cancer cells treated with 3c (2 μM) exhibited intense green fluorescence after 1 h irradiation (465 nm) indicative of ROS generation, while no fluorescence was observed in the dark. In contrast, cells treated with 2c (2 μM) displayed much less intense fluorescence after irradiation and again no fluorescence in the dark. These results indicate that a lower level of ROS was induced by mono-functionalised 2c compared to its di-functionalised analogue 3c, which correlates with its lower photocytotoxicity and cellular accumulation.

Fig. 5.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of ROS generation in A549 cells treated with (a) 2c and (b) 3c (2 μM, 1 h in dark and 1 h irradiation, 465 nm) then probed by DCFH-DA (20 μM, λex = 488 nm). A549 cells treated in the dark were studied for comparison. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Conclusions

Here we have synthesised and characterised six novel photoactive trans-diazido Pt(iv) dipyridine complexes, which differ in the presence of either one axial hydroxide ligand (mono-functionalised complexes 2a–2c, with cou, PhB or DCA as an axial ligand, respectively), or no axial hydroxide ligands (di-functionalised complexes 3a–3c with DCA as the second axial ligand). The X-ray crystal structures of complexes 2a and 3a–3c show a typical octahedral structure slightly distorted by the asymmetric axial ligands. These complexes are photoactive, generate Pt(ii) species which bind to 5′-GMP as monitored by LC-MS, and release azidyl and hydroxyl radicals as detected by EPR. Both axial ligands can be released from these complexes upon irradiation. However, mono-functionalised and di-functionalised complexes displayed significant differences in their photochemical and photobiological properties as summarised in Table 4.

Table 4. Comparison between mono- and di-functionalised complexes studied in this work, with dihydroxido complex 1 as a reference.

| Property | Mono-functionalised 2a–2c | Di-functionalised 3a–3c |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueous solubility | Good | Poor |

| Reduction potential | More negative | Less negative |

| Dark cytotoxicity | Similar to 1 (low) | Higher |

| Photo-cytotoxicity | Higher than 1 | Higher than 2a–2c |

| Cellular accumulation | Higher than 1 | Much higher than 2a–2c |

| ROS generation | Low | High |

Notably, mono-functionalised complexes 2a–2c with one hydroxide ligand show higher aqueous solubility, and more negative reduction potentials. In contrast, due to the replacement of hydroxide with a lipophilic dichloroacetate ligand, di-functionalised complexes 3a–3c exhibited much reduced aqueous solubility. Significantly higher cellular Pt accumulation (ca. 3–18×) and photo-induced cellular ROS levels were observed for di-functionalised complexes compared with their mono-functionalised analogues when cells were treated with complexes at the same concentration. As a result, higher photocytotoxicity (>3×) of di-functionalised complexes 3a–3c compared with 2a–2c and 1 in cancer cells was found. Mono-functionalised complexes 2a–2c also showed improved photocytotoxicity (>2.4× in A2780; >6.6× in A549) compared to unfunctionalised 1 and were non-toxic in the dark (IC50 values >100 μM). Notably, all of these complexes showed a higher photocytotoxicity and cellular accumulation in A2780 ovarian cancer cells compared to A549 lung cancer cells, and low cytotoxicity towards normal MRC-5 cells. Mono-functionalised complexes exhibited higher photoselectivity towards A2780 cells due to their low dark cytotoxicity, but di-functionalised complexes exhibited a selectivity towards A2780 cells both in the dark and upon irradiation with extremely high cellular accumulation and high potency (Iow-dose required). Thus, these di-functionalised complexes are promising candidates as clinical prodrugs to treat ovarian cancer locally by phototherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the EPSRC (EP/ G006792, EP/F034210/1 for PJS), University of Warwick (Chancellor’s International PhD Scholarship for HS), Anglo-American Platinum (HS) and Wellcome Trust (grant no 209173/Z/17/Z, Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship for CI). We thank Dr Ben Breeze for EPR experiments, Dr Lijiang Song for HR-MS data collection and Ian J. Hands-Portman for confocal microscopy training.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESi) available: Experimental section, NMR, Uv-vis, and LC-MS spectra. CCDC 2003123-2003126. For ESi and crystallo-graphic data in CiF or other electronic format see DOi: 10.1039/d0qi00685h

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Giandomenico CM, Abrams MJ, Murrer BA, Vollano JF, Rheinheimer MI, Wyer SB, Bossard GE, Higgins JD. Carboxylation of kinetically inert platinum(IV) hydroxy complexes. An entr.acte.ee into orally active platinum(IV) antitumor agents. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:1015–1021. doi: 10.1021/ic00109a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnstone TC, Suntharalingam K, Lippard SJ. The next generation of platinum drugs: targeted Pt(II) agents, nanoparticle delivery, and Pt(IV) prodrugs. Chem Rev. 2016;116:3436–3486. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson D. Multi-action Pt(IV) anticancer agents; do we understand how they work? J Inorg Biochem. 2019;191:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mi Q, Shu SS, Yang CX, Gao C, Zhang X, Luo X, Bao CH, Zhang X, Niu J. Current status for oral platinum(IV) anticancer drug development. Clin Eng Radiat Oncol. 2018;7:231–247. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bramwell VH, Crowther D, O’Malley S, Swindell R, Johnson R, Cooper EH, Thatcher N, Howell A. Activity of JM9 in advanced ovarian cancer: a Phase I-II trial. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69:409–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Rourke TJ, Weiss GR, New P, Burris HA, III, Rodriguez G, Eckhardt J, Hardy J, Kuhn JG, Fields S, Clark GM, von Hoff DD. Phase I clinical trial of ormaplatin (tetraplatin, NSC 363812) Anti-Cancer Drugs. 1994;5:520–526. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKeage MJ, Raynaud F, Ward J, Berry C, O’Dell D, Kelland LR, Murrer B, Santabárabara P, Harrap KR, Judson IR. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of an oral platinum complex given daily for 5 days in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2691–2700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchal P, Jarkovsky J, Hrazdilova K, Dvorakova M, Struharova I, Hernychova L, Damborsky J, Sova P, Vojtesek B. The new platinum-based anticancer agent LA-12 induces retinol binding protein 4 in vivo. Proteome Sci. 2011;9:68. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-9-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wheate NJ, Walker S, Craig GE, Oun R. The status of platinum anticancer drugs in the clinic and in clinical trials. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:8113–8127. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00292e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi H, Imberti C, Sadler PJ. Diazido platinum(IV) complexes for photoactivated anticancer chemotherapy. Inorg Chem Front. 2019;6:1623–1638. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurruchaga-Pereda J, Martinez Á, Terenzi A, Salassa L. Anticancer platinum agents and light. Inorg Chim Acta. 2019;495 118981. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imran M, Ayub W, Butler IS, Rehman Z. Photoactivated platinum-based anticancer drugs. Coord Chem Rev. 2018;376:405–429. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bednarski PJ, Korpis K, Westendorf AF, Perfahl S, Grünert R. Effects of light-activated diazido-PtIV complexes on cancer cells in vitro . Philos Trans R Soc, A. 2013;371 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2012.0118. 20120118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitra K. Platinum complexes as light promoted anticancer agents: a redefined strategy for controlled activation. Dalton Trans. 2016;45:19157–19171. doi: 10.1039/c6dt03665a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrer NJ, Woods JA, Salassa L, Zhao Y, Robinson KS, Clarkson G, Mackay FS, Sadler PJ. A potent trans-diimine platinum anticancer complex photoactivated by visible light. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:8905–8908. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kratochwil NA, Bednarski PJ. Relationships between reduction properties and cancer cell growth inhibitory activities of cis-dichloro- and cis-diiodo-Pt(IV)-ethylenediamines. Arch Pharm Pharm Med Chem. 1999;332:279–285. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-4184(19998)332:8<279::aid-ardp279>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis LT, Meng Er H, Hambley TW. The influence of the axial ligands of a series of platinum(IV) anti-cancer complexes on their reduction to platinum(II) and reaction withDNA. Aust J Chem. 1995;48:793–806. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall MD, Hambley TW. Platinum(IV) antitumour compounds: their bioinorganic chemistry. Coord Chem Rev. 2002;232:49–267. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi S, Filotto C, Bisanzo M, Delaney S, Lagasee D, Whitworth JL, Jusko A, Li C, Wood NA, Willingham J, Schwenker A, Spaulding K. Reduction and anticancer activity of platinum(IV) complexes. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:2500–2504. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Deng Z, Zhu G. Emerging platinum(IV) prodrugs to combat cisplatin resistance: from isolated cancer cells to tumor microenvironment. Dalton Trans. 2019;48:2536–2544. doi: 10.1039/c8dt03923b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Liu Y, Tian H. Current developments in Pt(IV) prodrugs conjugated with bioactive ligands. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/8276139. 8276139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi H, Imberti C, Huang H, Hands-Portman I, Sadler PJ. Biotinylated photoactive Pt(IV) anticancer complexes. Chem Commun. 2020;56:2320–2323. doi: 10.1039/c9cc07845b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thakur A, Singla R, Jaitak V. Coumarins as anticancer agents: a review on synthetic strategies, mechanism of action and SAR studies. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;101:476–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaur M, Kohli S, Sandhu S, Bansal Y, Bansal G. Coumarin: a promising scaffold for anticancer agents. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2015;15:1032–1048. doi: 10.2174/1871520615666150101125503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hafez OM, Nassar MI, El-Kousy SM, Abdel-Razik AF, Sherien MM, El-Ghonemy MM. Synthesis of some new carbonitriles and pyrazole coumarin derivatives with potent antitumor and antimicrobial activities. Acta Pol Pharm. 2014;71:594–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lina MH, Cheng CH, Chen KC, Lee WT, Wang YF, Xiao CQ, Lin CW. Induction of ROS-independent JNK-activation-mediated apoptosis by a novel coumarin-derivative, DMAC, in human colon cancer cells. Chem -Biol Interact. 2014;218:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maiti S, Park N, Han JH, Jeon HM, Lee JH, Bhuniya S, Kang C, Kim JS. Gemcitabine-coumarinbiotin conjugates: a target specific theranostic anticancer prodrug. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4567–4572. doi: 10.1021/ja401350x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyson DS, Castellano FN. Light-harvesting arrays with coumarin donors and MLCT acceptors. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:4382–4383. doi: 10.1021/ic9905300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petruzzella E, Braude JP, AIdrich-Wright JR, Gandin V, Gibson D. A quadruple-action platinum(IV) prodrug with anticancer activity against KRAS mutated cancer cell lines. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:11539–11544. doi: 10.1002/anie.201706739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaiser GS, Germann SM, Westergaard T, Lisby M. Phenylbutyrate inhibits homologous recombination induced by camptothecin and methyl methanesulfonate. Mutat Res. 2011;713:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhar S, Lippard SJ. Mitaplatin, a potent fusion of cisplatin and the orphan drug dichloroacetate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22199–22204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912276106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raveendran R, Braude JP, Wexselblatt E, Novohradsky V, Stuchlikova O, Brabec V, Gandin V, Gibson D. Pt(IV) derivatives of cisplatin and oxaliplatin with phenylbutyrate axial ligands are potent cytotoxic agents that act by several mechanisms of action. Chem Sci. 2016;7:2381–2391. doi: 10.1039/c5sc04205d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manevich Y, Held KD, Biaglow JE. Coumarin-3-car-boxylic acid as a detector for hydroxyl radicals generated chemically and by gamma radiation. Radiat Res. 1997;148:580–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi H, Romero-Canelón I, Hreusova M, Novakova O, Venkatesh V, Habtemariam A, CIarkson GJ, Song J, Brabec V, Sadler PJ. Photoactivatable cell-selective dinuclear trans-diazidoplatinum(IV) anticancer prodrugs. Inorg Chem. 2018;57:14409–14420. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou L, Liu L, Chai W, Zhao T, Jin X, Guo X, Han L, Yuan C. Dichloroacetic acid upregulates apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells by regulating mitochondrial function. OncoTargets Ther. 2019;12:1729–1739. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S194329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Ames BN. Detection of picomole levels of hydroperoxides using a fluorescent dichloro-fluorescein assay. Anal Biochem. 1983;134:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.