Abstract

Background

The impact of heart failure (HF) duration on outcomes and treatment effect is largely unknown. We aim to compare baseline patient characteristics, outcomes and the efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin, in relation to time from diagnosis of HF in DAPA-HF.

Methods

HF duration was categorized as ≥2 to ≤12 months, >1-2 years, >2-5 years and >5 years. Outcomes were adjusted for prognostic variables and analyzed using Cox regression. The primary endpoint was the composite of worsening HF or cardiovascular death. Treatment effect was examined within each duration category and by duration threshold.

Results

The number of patients in each category was: 1098 (≥2 to ≤12 months), 686 (>1-2 years), 1105 (>2-5 years) and 1855 (>5 years). Longer-duration HF patients were older and more comorbid with worse symptoms. The rate of the primary outcome (per 100 person-years) increased with HF duration: 10.2 (95% CI 8.7-12.0) for ≥2 to ≤12 months, 10.6 (8.7-12.9) >1-2 years, 15.5 (13.6-17.7) >2-5 years and 15.9 (14.5-17.6) for >5 years. Similar trends were seen for all other outcomes. The benefit of dapagliflozin was consistent across HF duration and on threshold analysis. The hazard ratio for the primary outcome ≥2 to ≤12 months was 0.86 (0.63-1.18), >1-2 years 0.95 (0.64-1.42), >2-5 years 0.74 (0.57-0.96) and >5 years 0.64 (0.53-0.78), P-interaction=0.26. The absolute benefit was greatest in longest duration HF, with a number needed-to-treat of 18 for HF >5 years, compared with 28 for ≥2 to ≤12 months.

Conclusions

Longer-duration HF patients were older, had more comorbidity and symptoms, and higher rates of worsening HF and death. The benefits of dapagliflozin were consistent across HF duration.

Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03036124

Keywords: heart failure, dapagliflozin, duration

The Dapagliflozin And Prevention of Adverse-outcomes in Heart Failure trial (DAPA-HF) demonstrated clinical benefits of the sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) dapagliflozin, when added to standard therapy, in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), independently of diabetes status.1 Further subgroup analyses demonstrated consistent benefit, irrespective of age, ejection fraction and background heart failure therapy, among others. However, whether the benefit of dapagliflozin varies by duration of heart failure is unknown. In fact, few studies have reported any data on the relationship between duration of heart failure and patient characteristics, or whether duration of heart failure modifies the efficacy and safety of therapy.2,3 Complex and potentially competing factors are at play in relation to duration of heart failure. On the one hand, longer duration might be expected to be associated with more advanced disease, as heart failure is a progressive condition. On the other hand, by definition, patients with longer-standing heart failure are a survivor cohort. Longer-duration also means more opportunity to optimise pharmacological and device therapy, although disease progression might also lead to the development of intolerance of certain pharmacological agents because of problems such as hypotension and kidney dysfunction. Ultimately, the physician may be left with the question whether is still worthwhile starting a new treatment in a patient who has already survived for an extended time? Therefore, we have investigated these questions further in this post hoc analysis of DAPA-HF. Specifically, our aims were to compare patient demographics, comorbidities, heart failure characteristics and background therapy according to duration of heart failure, as well as outcomes in relation to time from diagnosis of heart failure. We also analysed the effects of dapagliflozin, compared to placebo, according to duration of heart failure.

Methods

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy (https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure).

DAPA-HF (NCT03036124) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, event-driven, trial in patients with HFrEF who were enrolled between February 2017 and August 2018. The efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily, added to standard care, was compared with matching placebo. The design, baseline characteristics, and primary results are published.1,4,5 The Ethics Committee of the 410 participating institutions (in 20 countries) approved the protocol, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Study Patients

Patients aged ≥18 years with HF were eligible if they were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II-IV for ≥2 months and had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40%, an elevated natriuretic peptide level and were receiving optimal HFrEF pharmacological and device therapy, according to local guidelines.

Key exclusion criteria included symptomatic hypotension or systolic blood pressure (SBP) <95mmHg, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30ml/min/1.73m2 or rapid decline in renal function and Type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Trial Outcomes

The primary trial outcome was the composite of worsening heart failure (HF hospitalization or urgent visit attributed to HF requiring intravenous therapy) or cardiovascular (CV) death, whichever occurred first. Prespecified secondary endpoints included HF hospitalization or CV death; HF hospitalizations (first and recurrent) and cardiovascular deaths; change from baseline to 8 months in the total symptom score of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-TSS); the incidence of a composite worsening renal function outcome and all-cause death. Because of the small number of renal events overall, this endpoint was not examined in the present analysis of subgroups. Prespecified safety analyses included any serious adverse event, adverse events leading to discontinuation of trial treatment, adverse events of interest (i.e., volume depletion, renal events, major hypoglycaemic events, bone fractures, diabetic ketoacidosis, amputation) and any diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene, as well as laboratory findings of note.

Duration of heart failure

Time from diagnosis of HF was collected in the following categories: ≤3 months, >3-6 months, >6-12 months, >1-2 years, >2-5 years and >5 years. Due to inclusion criteria of the DAPA-HF trial, the ≤3 months category only includes patients with HF duration of 2-3 months. In this analysis, we combined the first three categories to form the HF duration ≤1-year group (i.e. patients with HF duration of ≥2 months-1 year), to ensure adequate numbers for analysis in each category. However, all pre-defined categories were used in the threshold analysis (see below).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are summarized as frequencies with percentages for categorical variables and means ± standard deviations (SD) for all continuous variables, except NT-proBNP which is reported as medians and interquartile ranges. A Wilcoxon‐type test for trend was used to compare baseline characteristics between groups.6

Time-to-event hospitalization/death endpoints were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier estimates and Cox proportional-hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and treatment effect. Along with crude HRs, which had history of prior HF hospitalization and assigned treatment group as fixed-effect factors and stratified by diabetes status, we report adjusted HRs from models including the aforementioned factors along with age, region, gender, race, heart rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), body mass index (BMI), NYHA class, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), eGFR, history of myocardial infarction (MI), history of atrial fibrillation (AF), NT-proBNP and baseline KCCQ-CSS. These variables are known predictors of risk in patients with HF.7,8

Total (including recurrent) hospitalizations for HF were analysed using the Lin, Wei, Yang and Ying (LWYY) model, including treatment effect, and reported as crude and adjusted rate-ratios (RRs).9 The LWYY model is a generalisation of the Cox proportional-hazards model which considers each repeat event as a separate term. It is based on a gap-time approach considering the time since a previous event to account for the dependency of within-subject events. The model employs a robust standard error to account for the interdependency of events within an individual. The change in KCCQ-TSS from baseline to 8 months was analyzed using a repeated measures mixed model adjusted for baseline values, visit, randomized treatment, and interaction of treatment and visit with a random intercept and slope per patient with an unstructured covariance structure. When analyzing changes by HF duration, this term and its interaction with time were entered into the model. For adjusted models, we adjusted for the same variables as noted above for the Cox models. The effect of dapagliflozin compared to placebo on the proportion of patients with clinically significant (≥5 point) improvement or deterioration in KCCQ-TSS at 8 months from baseline (“responder analysis”), was analysed using previously described methods and reported as odds ratios (ORs).10 For treatment effect, the primary variable of interest was the interaction P-value for randomized treatment group and HF duration. For the analysis of adverse events and study drug discontinuation, we used logistic regression and the likelihood ratio test to report interaction between randomized treatment and HF duration. We also performed a threshold analysis where the treatment effect of dapagliflozin, compared to placebo, on the primary composite outcome was calculated for each threshold value for the minimum HF duration (>0, >0.25, >0.5, >1, >2 and >5years), using a Cox model adjusted for prognostic variables mentioned above. For each threshold value, the model was applied to data for patients with HF duration of at least the threshold value.

A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 16.0 (Stata Corp. College Station, Texas, USA) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Among the 4744 patients in DAPA-HF, the number in each HF duration category analysed was: ≥2 to ≤12 months 1098 (23.1%), >1-2 years 686 (14.5%), >2-5 years 1105 (23.3%), and >5 years 1855 (39.1%).

Baseline characteristics

Most baseline characteristics including demographics, comorbidities, symptoms and functional status differed in relation to time since diagnosis of HF (Table 1). Patients with longer-duration HF were older (mean 68.1 years in the HF >5 years group versus 64.4 years in the ≥2 to ≤12 months r group) and more comorbid; a greater proportion had a history of hypertension (76.5% vs 70.4%), myocardial infarction (48.4% vs. 36.7%), stroke (11.6% vs 7.8%), obesity (36.1% vs 32.8%), atrial fibrillation (43.9% vs 31.2%) and chronic kidney disease (45.8% vs 32.1%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics according to duration of heart failure.

| Characteristic | HF ≥2 months-1 year (N=1098) |

HF >1-2 years (N=686) |

HF >2-5 years (N=1105) |

HF >5 years (N=1855) |

P-value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age – years | 64.4±11.7 | 64.9±11.4 | 66.4±10.5 | 68.1±10.1 | <0.001 |

| Age >75 years – no. (%) | 195 (17.8) | 132 (19.2) | 206 (18.6) | 470 (25.3) | <0.001 |

| Female sex – no. (%) | 251 (22.9) | 156 (22.7) | 260 (23.5) | 442 (23.8) | 0.487 |

| Race or ethnic group – no. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 740 (67.4) | 471 (68.7) | 785 (71.0) | 1337 (72.1) | |

| Black | 30 (2.7) | 28 (4.1) | 64 (5.8) | 104 (5.6) | |

| Asian | 304 (27.7) | 176 (25.7) | 244 (22.1) | 392 (21.1) | |

| Other | 24 (2.2) | 11 (1.6) | 12 (1.1) | 22 (1.2) | |

| Region – no. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| North America | 121 (11.0) | 78 (11.4) | 164 (14.8) | 314 (16.9) | |

| Latin America | 176 (16.0) | 124 (18.1) | 203 (18.4) | 314 (16.9) | |

| Europe | 498 (45.4) | 312 (45.5) | 502 (45.4) | 842 (45.4) | |

| Asia Pacific | 303 (27.6) | 172 (25.1) | 236 (21.4) | 385 (20.8) | |

| Systolic BP- mmHg | 123.6±16.7 | 122.2±16.4 | 121.8±15.9 | 120.6±16.2 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate – bpm | 72.9±11.9 | 71.9±12.4 | 72.1±11.3 | 70.2±11.4 | <0.001 |

| BMI - kg/m2 | 27.7±5.9 | 28.0±5.9 | 28.3±5.9 | 28.4±6.0 | <0.001 |

| BMI classification | 0.003 | ||||

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 360 (32.8) | 244 (35.6) | 399 (36.1) | 669 (36.1) | |

| Overweight (BMI 25-29.9) | 374 (34.1) | 246 (35.9) | 402 (36.4) | 700 (37.8) | |

| Normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9) | 342 (31.1) | 180 (26.2) | 284 (25.7) | 455 (24.6) | |

| Underweight (BMI<18.5) | 22 (2.0) | 16 (2.3) | 20 (1.8) | 29 (1.6) | |

| Hemoglobin – g/L | 136.4±16.6 | 134.9±16.7 | 136.0±15.7 | 134.9±16.0 | 0.040 |

| Serum Creatinine – μmol/L | 98.9±28.7 | 102.4±30.2 | 106.4±30.2 | 107.3±31.1 | <0.001 |

| eGFR - mL/min/1.73m2 | 70.3±20.0 | 68.0±20.3 | 64.5±19.3 | 63.0±18.2 | <0.001 |

| Clinical HF features | |||||

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy – no. (%) | 575 (52.4) | 400 (58.3) | 621 (56.2) | 1078 (58.1) | 0.009 |

| LVEF - % | 31.9±6.7 | 31.2±6.7 | 31.1±6.6 | 30.5±6.9 | <0.001 |

| Median NT-proBNP (IQR) pmol/L | 1374 (807-2536) | 1387 (843-2748) | 1489 (890-2825) | 1477 (879-2597) | 0.056 |

| Median NT-proBNP (IQR) pmol/L if AF history | 1812 (1107-3074) | 1841 (1157-3110) | 1818 (1170-3083) | 1744 (1084-3019) | 0.476 |

| Median NT-proBNP (IQR) pmol/L if no AF history | 1238 (737-2268) | 1217 (724-2412) | 1293 (739-2492) | 1269 (759-2298) | 0.287 |

| NYHA Class – no. (%) | 0.592 | ||||

| II | 761 (69.3) | 442 (64.4) | 756 (68.4) | 1244 (67.1) | |

| III | 323 (29.4) | 233 (34.0) | 343 (31.0) | 599 (32.3) | |

| IV | 14 (1.3) | 11 (1.6) | 6 (0.5) | 12 (0.6) | |

| KCCQ-TSS (baseline). (IQR) | 79.2 (60.4-93.8) | 79.2 (60.4-91.7) | 77.1 (58.3-91.7) | 77.1 (58.3-91.7) | 0.019 |

| KCCQ-CSS (baseline) (IQR) | 76.0 (58.3-89.6) | 75.0 (56.9-87.5) | 74.3 (56.9-88.9) | 73.6 (55.6-87.5) | 0.002 |

| Medical History – no. (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 773 (70.4) | 503 (73.3) | 827 (74.8) | 1419 (76.5) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (history) | 421 (38.3) | 294 (42.9) | 474 (42.9) | 794 (42.8) | 0.031 |

| Diabetes (at randomization) | 467 (42.5) | 311 (45.3) | 510 (46.2) | 851 (45.9) | 0.090 |

| Atrial Fibrillation (History) | 343 (31.2) | 226 (32.9) | 434 (39.3) | 815 (43.9) | <0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation (ECG) | 234 (21.3) | 142 (20.7) | 255 (23.1) | 440 (23.8) | <0.001 |

| Prior HF hospitalization | 569 (51.8) | 324 (47.2) | 503 (45.5) | 855 (46.1) | 0.003 |

| MI | 403 (36.7) | 312 (45.5) | 479 (43.3) | 898 (48.4) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 86 (7.8) | 56 (8.2) | 109 (9.9) | 215 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 125 (11.4) | 92 (13.4) | 138 (12.5) | 230 (12.4) | 0.587 |

| CKD (eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73m2) | 352 (32.1) | 241 (35.1) | 484 (43.8) | 849 (45.8) | <0.001 |

| Anemia* | 295 (27.0) | 199 (29.3) | 281 (25.6) | 527 (28.7) | 0.560 |

| HF treatments – no. (%) | |||||

| ACEi/ARB/ARNI | 1036 (94.4) | 641 (93.4) | 1025 (92.8) | 1740 (93.8) | 0.569 |

| B-blocker | 1042 (94.9) | 660 (96.2) | 1068 (96.7) | 1788 (96.4) | 0.053 |

| Diuretic | 1023 (93.2) | 649 (94.6) | 1043 (94.4) | 1718 (92.6) | 0.393 |

| Digitalis | 164 (14.9) | 124 (18.1) | 221 (20.0) | 378 (20.4) | <0.001 |

| MRA | 799 (72.8) | 506 (73.8) | 797 (72.1) | 1268 (68.4) | 0.004 |

| ICD/CRT-D | 117 (10.7) | 144 (21.0) | 297 (26.9) | 684 (36.9) | <0.001 |

| CRT-P/CRT-D | 24 (2.2) | 32 (4.7) | 93 (8.4) | 205 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes treatments – no. (%)† | |||||

| Biguanides | 238 (56.5) | 158 (53.7) | 243 (51.3) | 377 (47.5) | 0.002 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | 55 (13.1) | 34 (11.6) | 76 (16.0) | 145 (18.3) | 0.004 |

| GLP-1 analogues | 2 (0.5) | 5 (1.7) | 6 (1.3) | 8 (1.0) | 0.623 |

| Sulfonylureas | 104 (24.7) | 67 (22.8) | 91 (19.2) | 176 (22.2) | 0.278 |

| Insulin | 91 (21.6) | 71 (24.2) | 140 (29.5) | 238 (30.0) | 0.001 |

Interquartile range (IQR), blood pressure (BP), body mass index (BMI), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), heart failure (HF), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), NT-proB-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP), atrial fibrillation (AF), electrocardiogram (ECG), New York Heart Association (NYHA), Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire total symptom score and clinical summary score (KCCQ-TSS and -CSS).

Myocardial infarction (MI), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), beta-blocker (B-blocker), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with pacemaker (P) or defibrillator (D).

Anemia: Hemoglobin <130 g/L in males and Hemoglobin <120 g/L in females.

Only in patients with a pre-trial history of diabetes.

Units: millimeters of mercury (mmHg), beats per minute (bpm), kilograms per meter squared (kg/m2), grams per liter (g/L), micromoles per liter (μmol/L), picomoles per liter (pmol/L).

NT-proBNP levels did not differ by duration of HF, even after accounting for differences in frequency of atrial fibrillation and LVEF differed only slightly by HF duration (30.5% vs 31.9%). Severity of symptoms and functional limitation as reported by patients using the KCCQ-TSS and -CSS was greater in patients with longer-standing HF although functional limitation assessed by physicians (NYHA Class) did not differ by duration of HF.

Treatments at baseline

Pharmacological treatment for HF were similar across all durations of HF, except for MRA use which was greatest in those with the most recent diagnosed HF (≥2 to ≤12 months). Conversely, there was a 3 to 5-fold difference in rates of device therapy in relation to duration of HF. Patients with HF >5 years were most likely to have a defibrillating device (36.9% in the HF >5 years group versus 10.7% in the ≥2 to ≤12 months group) and a cardiac resynchronization device (11.1% vs 2.2% respectively).

Patients with diabetes who had longer duration HF were significantly more likely to be treated with insulin therapy.

Primary and secondary outcomes in relation to duration of HF

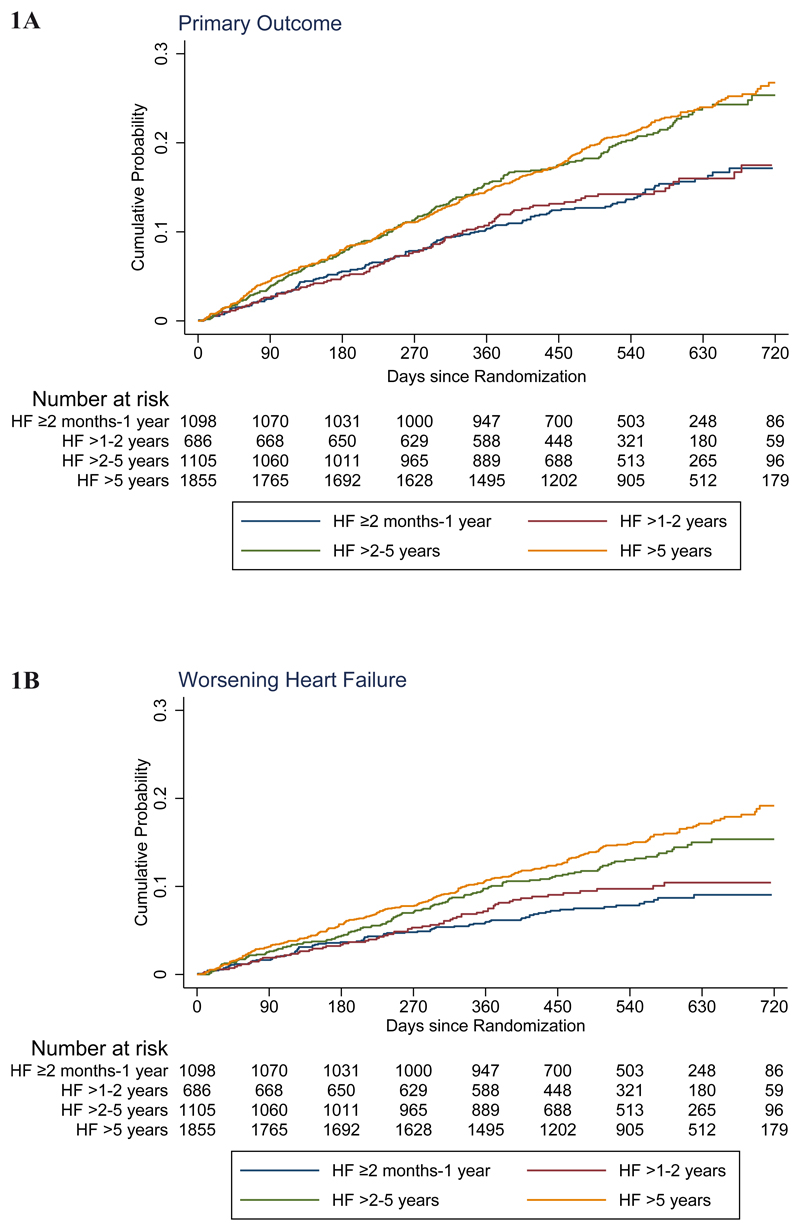

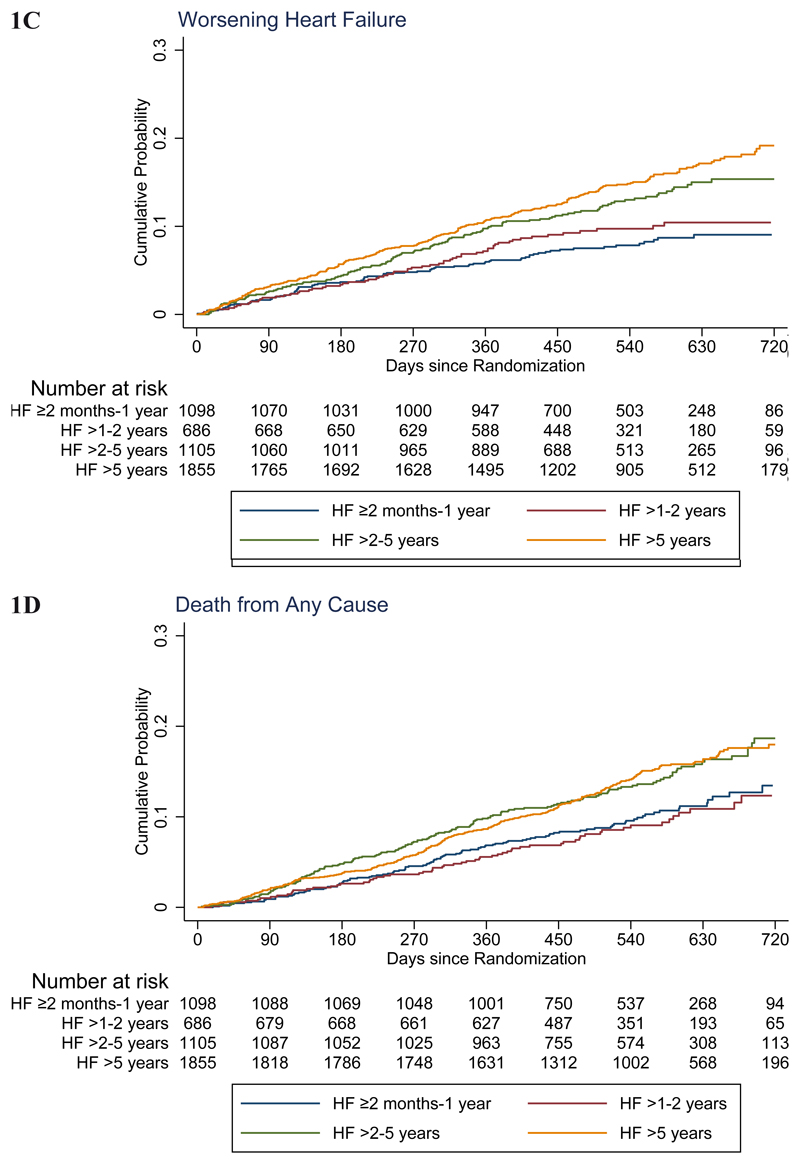

The rate (per 100 patient-years) of the primary composite outcome of worsening HF or cardiovascular death increased with duration of HF: ≥2 to ≤12 months 10.2 (95% CI 8.7-12.0), >1-2 years 10.6 (8.7-12.9), >2-5 years 15.5 (13.6-17.7) and >5 years 15.9 (14.5-17.6). The hazard ratio adjusted for prognostic variables, using the HF ≥2 to ≤12 months group as the reference, was 0.98 (95% CI 0.75-1.27), 1.53 (1.23-1.90) and 1.60 (1.31-1.96) respectively, for HF >1-2, >2-5 and >5 years duration (Table 2 and Figure 1). Similar trends were seen for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, with lower and similar rates in the first two duration categories (≥2 to ≤12 months and >1-2 years) and substantially higher, but again similar, rates in the two longer duration groups (>2-5 and >5 years). Worsening HF (and HF hospitalization by itself) showed a more graded rise in risk with increasing duration of HF, rather than the bimodal distribution of risk for death (and the composites including death) centred around 2 years.

Table 2. Event rate (per 100 patient-years) and risk of study endpoints according to duration of heart failure (HF ≥2 months-1 year as reference).

| HF ≥2 months-1 year | HF >1-2 years | HF >2-5 years | HF >5 years | P-value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1098 | 686 | 1105 | 1855 | |

| Worsening HF or cardiovascular death – no. (%) | 154 (14.0) | 101 (14.7) | 230 (20.8) | 403 (21.7) | <0.001 |

| Event rates per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | 10.2 (8.7-12.0) | 10.6 (8.7-12.9) | 15.5 (13.6-17.7) | 15.9 (14.5-17.6) | |

| Unadjusted* HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.03 (0.80-1.33) | 1.56 (1.27-1.91) | 1.58 (1.32-1.91) | |

| Adjusted† HR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.98 (0.75-1.27) | 1.53 (1.23-1.90) | 1.60 (1.31-1.96) | |

| Hospitalization or urgent visit for HF - no. (%) | 84 (7.7) | 65 (9.5) | 138 (12.5) | 276 (14.9) | <0.001 |

| Event rates per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | 5.6 (4.5-6.9) | 6.8 (5.4-8.7) | 9.3 (7.9-11.0) | 10.9 (9.7-12.3) | |

| Unadjusted* HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.22 (0.88-1.69) | 1.73 (1.32-2.27) | 2.01 (1.58-2.57) | |

| Adjusted† HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.24 (0.88-1.74) | 1.76 (1.31-2.35) | 2.03 (1.55-2.65) | |

| HF hospitalization - no. (%) | 80 (7.3) | 65 (9.5) | 135 (12.2) | 269 (14.5) | <0.001 |

| Event rates per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | 5.3 (4.3-6.6) | 6.8 (5.4-8.7) | 9.1 (7.7-10.8) | 10.6 (9.4-12.0) | |

| Unadjusted* HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.29 (0.93-1.78) | 1.78 (1.35-2.35) | 2.06 (1.60-2.64) | |

| Adjusted† HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.31 (0.93-1.85) | 1.81 (1.35-2.43) | 2.08 (1.58-2.73) | |

| Urgent HF visit - no. (%) | 6 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 9 (0.8) | 16 (0.9) | 0.179 |

| Event rates per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | 0.2 (0.1-0.8) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | |

| Unadjusted* HR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.50 (0.10-2.50) | 1.52 (0.54-4.28) | 1.57 (0.61-4.01) | |

| Adjusted† HR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.56 (0.11-2.91) | 1.58 (0.50-4.97) | 1.77 (0.61-5.14) | |

| Cardiovascular death - no. (%) | 90 (8.2) | 54 (7.9) | 129 (11.7) | 227 (12.2) | <0.001 |

| Event rates per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | 5.7 (4.7-7.0) | 5.4 (4.2-7.1) | 8.2 (6.9-9.7) | 8.4 (7.4-9.6) | |

| Unadjusted* HR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.94 (0.67-1.31) | 1.44 (1.10-1.89) | 1.47 (1.15-1.87) | |

| Adjusted† HR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.85 (0.59-1.21) | 1.36 (1.02-1.81) | 1.46 (1.12-1.90) | |

| Cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization - no. (%) | 151 (13.8) | 101 (14.7) | 229 (20.7) | 396 (21.3) | <0.001 |

| Event rates per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | 10.0 (8.5-11.7) | 10.6 (8.7-12.9) | 15.4 (13.6-17.6) | 15.6 (14.1-17.2) | |

| Unadjusted* HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.05 (0.82-1.36) | 1.58 (1.29-1.94) | 1.58 (1.31-1.91) | |

| Adjusted† HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (0.77-1.31) | 1.55 (1.25-1.94) | 1.60 (1.31-1.97) | |

| Total number of HF hospitalizations and Cardiovascular deaths - total events | 211 | 148 | 325 | 625 | |

| Event rates per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | 13.5 (11.3-16.2) | 14.9 (11.9-18.9) | 20.7 (18.0-23.9) | 23.3 (20.9-26.1) | |

| Unadjusted* HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.10 (0.82-1.47) | 1.58 (1.26-1.98) | 1.75 (1.42-2.16) | |

| Adjusted† HR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.07 (0.78-1.46) | 1.52 (1.19-1.95) | 1.70 (1.35-2.14) | |

| All-cause mortality (no. of events) - no. (%) | 110 (10.0) | 63 (9.2) | 160 (14.5) | 272 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| Event rates per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | 7.0 (5.8-8.4) | 6.3 (4.9-8.1) | 10.1 (8.7-11.8) | 10.1 (9.0-11.4) | |

| Unadjusted* HR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.89 (0.65-1.22) | 1.46 (1.14-1.86) | 1.43 (1.15-1.79) | |

| Adjusted† HR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.81 (0.59-1.12) | 1.36 (1.05-1.76) | 1.40 (1.10-1.78) | |

| Change in KCCQ-TSS at 8 mo§ (±SE) | |||||

| Unadjusted|| | 6.48±0.53 | 5.46±0.67 | 4.70±0.54 | 3.07±0.41 | |

| Adjusted# | 6.17±0.53 | 5.27±0.67 | 4.76±0.54 | 3.35±0.41 | |

| Significant worsening in KCCQ-TSS (≥5) at 8 months§ | |||||

| Unadjusted** OR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.89 (0.77-1.03) | 1.07 (0.94-1.20) | 1.15 (1.05-1.28) | |

| Adjusted*** OR | 1.00 (ref) | 0.89 (0.77-1.03) | 1.06 (0.94-1.20) | 1.14 (1.02-1.27) | |

| Significant improvement in KCCQ-TSS (≥5) at 8 months§ | |||||

| Unadjusted** OR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.04 (0.91-1.18) | 0.99 (0.88-1.10) | 0.85 (0.78-0.94) | |

| Adjusted*** OR | 1.00 (ref) | 1.04 (0.91-1.18) | 0.99 (0.89-1.11) | 0.87 (0.79-0.96) |

Model adjusted for randomized therapy, previous heart failure hospitalization and stratified by diabetes status.

Model adjusted for model * and for age, sex, race, region, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, New York Heart Association classification, left ventricular ejection fraction, baseline KCCQ clinical summary score, estimated glomerular filtration rate, history of myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and log NT-proB-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP).

RR denotes rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) within (), assessed using the LWYY model.

Scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) range from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicating fewer symptoms and physical limitations associated with heart failure).

Model adjusted for baseline KCCQ-TSS score and randomized treatment.

Model adjusted for model || and for age, sex, race, region, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, New York Heart Association classification, left ventricular ejection fraction, baseline KCCQ clinical summary score, estimated glomerular filtration rate, history of myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and log NT-proBNP.

Model adjusted for baseline KCCQ-TSS score rank, diabetes status and randomized treatment.

Model adjusted for model ** and for age, sex, race, region, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, New York Heart Association classification, left ventricular ejection fraction, baseline KCCQ clinical summary score, estimated glomerular filtration rate, history of myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and log NT-proBNP.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves for key study outcomes, according to heart failure duration.

The primary outcome was the composite of time to first worsening heart failure event or death from cardiovascular causes. The panels in this figure show cumulative event curves for: (A) Primary composite outcome (worsening heart failure or death from cardiovascular causes), (B) worsening heart failure, (C) death from cardiovascular causes, and (D) death from any cause.

All duration groups showed an average overall improvement (increase) in KCCQ-TSS between baseline and month 8. The improvement in KCCQ-TSS scores was smaller in patients with longer-standing HF. The mean improvement in KCCQ-TSS from baseline to month 8 was 6.48±0.53 (unadjusted) and 6.17±0.53 (adjusted) in the ≥2 to ≤12 months group, decreasing to 3.07±0.41 (unadjusted) and 3.35±0.41 (adjusted)in the >5 years group.

We repeated these analyses using the more granular HF duration groups of ≥2-6 months and >6 months-12 months, >1-2 years, >2-5 years and >5years, and found the same patterns (Supplemental Table I).

Effects of dapagliflozin according to duration of HF

The benefit of dapagliflozin was consistent across the spectrum of HF duration, for all outcomes examined (Table 3 and Supplemental Table II). The overall hazard ratio for the primary composite outcome was 0.74 (95% CI 0.65-0.85), in the ≥2 to ≤12 months group it was 0.86 (0.63-1.18) and in the >5 years group it was 0.64 (0.53-0.78), interaction p=0.26. Because the absolute risk was highest in patients with the longest-duration HF, the absolute benefit was also greatest in those patients, assuming a constant relative treatment effect-size across HF duration categories. On this basis, for the primary outcome, the number needed to treat (NNT) over the median duration of the trial (18.2 months) was 18 for patients with HF >5 years, compared with an NNT of 28 for patients with HF of ≥2 to ≤12 months duration.

Table 3. Treatment effect according to duration of heart failure (dapagliflozin vs placebo hazard ratio or difference and 95% confidence interval).

| Overall HR (95% CI) or Difference | HF ≥2 months-1 year HR (95% CI) or Difference | HF >1-2 years HR (95% CI) or Difference | HF >2-5 years HR (95% CI) or Difference | HF >5 years HR (95% CI) or Difference | P for interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 4744 | 1098 | 686 | 1105 | 1855 | - |

| Worsening HF or cardiovascular death | 0.74 (0.65-0.85) |

0.86 (0.63-1.18) |

0.95 (0.64-1.42) |

0.74 (0.57-0.96) |

0.64 (0.53-0.78) |

0.26 |

| Hospitalization or urgent visit for HF | 0.70 (0.59-0.83) |

0.76 (0.49-1.17) |

0.92 (0.56-1.50) |

0.64 (0.46-0.90) |

0.64 (0.51-0.82) |

0.52 |

| HF hospitalization | 0.70 (0.59-0.83) |

0.71 (0.45-1.11) |

0.92 (0.56-1.50) |

0.65 (0.46-0.91) |

0.66 (0.52-0.84) |

0.61 |

| Urgent HF visit | 0.43 (0.20-0.90) |

1.04 (0.21-5.16) |

1.16 (0.07-18.75) |

0.25 (0.05-1.23) |

0.31 (0.10-0.97) |

0.49 |

| Cardiovascular death | 0.82 (0.69-0.98) |

0.96 (0.63-1.45) |

0.79 (0.45-1.36) |

0.94 (0.67-1.33) |

0.72 (0.55-0.93) |

0.54 |

| Cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization | 0.75 (0.65-0.85) |

0.84 (0.61-1.16) |

0.96 (0.64-1.42) |

0.75 (0.58-0.97) |

0.65 (0.53-0.80) |

0.33 |

| Total number of HF hospitalizations* and cardiovascular deaths | 0.75 (0.65-0.88) |

0.79 (0.55-1.13) |

0.80 (0.51-1.28) |

0.81 (0.61-1.08) |

0.68 (0.55-0.85) |

0.77 |

| All-cause mortality | 0.83 (0.71-0.97) |

0.97 (0.66-1.40) |

0.80 (0.48-1.33) |

0.92 (0.68-1.26) |

0.72 (0.57-0.92) |

0.52 |

| Significant worsening in KCCQ-TSS† (≥5) at 8 months‡ | 0.96 (0.91-1.01) |

0.91 (0.79-1.04) |

0.85 (0.71-1.02) |

0.82 (0.72-0.95) |

0.79 (0.72-0.88) |

0.11 |

| Significant improvement in KCCQ-TSS† (≥5) at 8 months‡ | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) |

1.16 (1.02-1.31) |

1.17 (1.00-1.38) |

1.09 (0.96-1.25) |

1.19 (1.08-1.31) |

0.79 |

| Change in KCCQ-TSS§ at 8 months | 2.81±0.61 | 3.28±1.27 | 1.01±1.59 | 0.81±1.31 | 4.47±0.95 | 0.08 |

Effect of dapagliflozin on total HF hospitalizations was assessed using the LWYY model and is shown as rate ratios (RRs).

Scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) range from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicating fewer symptoms and physical limitations associated with heart failure).

Effect of dapagliflozin on significant improvement or worsening in KCCQ total symptom score (≥5) at 8 months is shown as odds ratios (ORs).

Treatment difference in mean change in KCCQ scores ± standard error (SE).

Dapagliflozin improved KCCQ-TSS between baseline and month 8, compared to placebo, and there was no statistically significant heterogeneity of effect by duration of HF. The KCCQ-TSS “responder” analysis corroborated these findings.

Threshold analysis

The threshold analysis illustrated the consistent benefit of dapagliflozin, compared with placebo, on the primary endpoint, regardless of the threshold value for HF duration (Figure 2). The adjusted hazard ratio for the primary endpoint was 0.71 (95%CI 0.62-0.82) for patients with HF duration >0.25 years, 0.70 (0.61-0.81) if HF duration >0.5 years, 0.70 (0.61-0.82) if HF duration >1 year, 0.65 (0.55-0.77) if HF duration >2 years and 0.59 (0.48-0.73) if HF duration >5 years.

Figure 2. Treatment effect of dapagliflozin on the primary composite outcome (cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure) according to threshold duration of heart failure.

Treatment effect for the primary composite outcome using a Cox model adjusted for prognostic variables as per Table 2 (†), according to threshold duration of heart failure. Confidence interval (CI).

Tolerability and safety

Adverse events were more common with increasing duration of HF, as was discontinuation of randomized therapy. However, neither adverse events nor discontinuation were more common with dapagliflozin, compared with placebo (Table 4).

Table 4. Prespecified adverse events (AEs) and study drug discontinuation according to duration of heart failure* .

| HF ≥2 months-1 year | HF >1-2 years | HF >2-5 years | HF >5 years | P for interaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=566) | Dapa (n=530) | Placebo (n=366) | Dapa (n=319) | Placebo (n=527) | Dapa (n=577) | Placebo (n=909) | Dapa (n=942) | ||

| Any discontinuation – no. (%) | 57 (10.1) | 47 (8.9) | 43 (11.8) | 32 (10.0) | 53 (10.1) | 59 (10.2) | 105 (11.6) | 111 (11.8) | 0.87 |

| Discontinuation due to AE – no. (%) | 18 (3.2) | 13 (2.5) | 13 (3.6) | 19 (6.0) | 31 (5.9) | 27 (4.7) | 54 (5.9) | 52 (5.5) | 0.36 |

| Adverse events – no. (%) | |||||||||

| Volume depletion | 21 (3.7) | 30 (5.7) | 14 (3.8) | 18 (5.6) | 38 (7.2) | 55 (9.5) | 89 (9.8) | 75 (8.0) | 0.05 |

| Renal | 22 (3.9) | 25 (4.7) | 17 (4.6) | 16 (5.0) | 48 (9.1) | 43 (7.5) | 83 (9.1) | 69 (7.3) | 0.27 |

| Fracture | 10 (1.8) | 9 (1.7) | 6 (1.6) | 4 (1.3) | 12 (2.3) | 11 (1.9) | 22 (2.4) | 25 (2.7) | 0.94 |

| Amputation | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 8 (0.9) | 7 (0.7) | - |

| Major hypoglycaemia | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | - |

Only in the safety set except for discontinuation due to any cause

Discussion

Three main aspects of these findings merit further discussion. Firstly, our description of baseline characteristics provides insight into how patient demographics, comorbidities, symptoms and treatments vary in relation to time from diagnosis in patients with chronic HFrEF, findings surprisingly rarely reported.2,3 Secondly, we describe the relationship between chronicity of HF and clinical outcomes. Thirdly, we report whether the benefits of treatment with dapagliflozin were modified by duration of HF.

Most of the few studies that have described variation of patient characteristics and outcomes in relation to duration of HF have focussed on individuals hospitalised with acute HF.11–15 By contrast, little has been written about heterogeneity related to HF-duration in the chronic setting, with only an original report from the Systolic Heart failure treatment with the If inhibitor ivabradine Trial (SHIFT), in which patients were recruited between 2006 and 2009, and a follow-up report from the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with an ACE-Inhibitor to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM-HF) in which patients were enrolled between 2009 and 2012.2,3 As in SHIFT and PARADIGM-HF, we found that patients with longer duration HF were older, had a greater prevalence of co-morbidities, and were more likely to have an ischaemic aetiology. The latter is, at first sight, counterintuitive, given that prognosis is worse in patients with an ischaemic aetiology. However, recovery of LVEF is less common in patients with an ischaemic aetiology, compared with a non-ischaemic aetiology, and among patients with long-standing HFrEF, proportionately more ischaemic than non-ischaemic patients with a persistently low LVEF might be expected. Nevertheless, some survivor bias is still likely and is supported by the observation of a similar median NT-proBNP level in patients in each of the HF-duration categories, a finding also observed in PARADIGM-HF.3

The older age and greater prevalence of non-cardiovascular and cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with a longer history of HF is also important in that, collectively, these might reduce tolerability of treatment. In turn, this may increase the likelihood of study drug discontinuation and reduce the overall efficacy of randomized therapy. This question was not tested in SHIFT and could not be fully addressed in PARADIGM-HF because of the long run-in period requiring tolerance of the target-dose of both enalapril and sacubitril/valsartan before randomization. In DAPA-HF, adverse events were more common with increasing duration of HF, as was study drug discontinuation, but neither was more common with dapagliflozin, compared with placebo. The same considerations may explain the lower use of non-randomized MRA therapy in patients with the longest-standing heart failure, probably reflecting the worse renal function in these individuals. Conversely, device use was higher in patients with longer-duration heart failure, presumably because devices are indicated only when LVEF remains low and symptoms persist, despite an adequate period of optimised pharmacological therapy.

In terms of clinical outcomes, we demonstrated worse outcomes with longer-duration HF, including in patient-reported symptoms (KCCQ-TSS). Although the rates of all hospitalization and death outcomes examined were higher with longer-duration HF, the extent to which risk was augmented differed between mortality (whether cardiovascular or all-cause) and worsening HF, including HF hospitalization. There was a clear stepwise increment in risk of HF hospitalization between the HF-duration groups as was seen in SHIFT, whereas the risk of death was similarly elevated in patients with HF for >2-5 years and those with HF >5 years which differs from the mortality trends observed in SHIFT. These findings, while interesting, require further validation. Importantly, the incremental risk associated with a longer duration of HF persisted after extensive adjustment for prognostic variables. This suggests that the excess risk related to duration of heart failure is not wholly explained by conventional prognostic variables including age, demographics and comorbidity. This raises the interesting future research question as to what does account for the higher risk associated with longer-standing HF. Our findings, along with those from SHIFT, also differ from those in the Acute Study of Clinical Effectiveness of Nesiritide in in Decompensated Heart Failure trial (ASCEND-HF) where event rates were lower among patients with recently diagnosed HF (0 to 1 month) than in patients with longer-duration HF and event rates were similar among those with HF-durations of >1 to 12 months, >12 months to 60 months, and >60 months. However, these differences are hard to compare because ASCEND-HF enrolled decompensated patients with both HFpEF and HFrEF and only examined short-term outcomes (mainly 30-days but up to 180-days for all-cause mortality). The intermediate duration group also spanned a duration of 1 to 5 years.

Lastly, we showed a consistent benefit of dapagliflozin, compared to placebo, across the whole spectrum of HF-duration for all the outcomes examined, both by categorised HF-duration, as well as using a threshold analysis. This is important, clinically, because it means that it is not too late to start treatment in patients who may have had heart failure for some time and may be considered as “stable” survivors. As is clear from the foregoing discussion, this is far from the case. Indeed, because these patients have a much higher absolute risk of events, they obtain a larger absolute risk reduction than patients with shorter duration HF (NNT 18 for patients with HF >5 years, compared with an NNT of 28 for patients with HF of ≥2 to ≤12 months duration). Not only was the size of this treatment benefit notable, but patients with the longest-duration HF received good pharmacological treatment and, as noted above, had the highest use of device therapy.

Study limitations

As with all studies like this, there are limitations. This analysis was post-hoc. Although we used a large, contemporary, geographically representative clinical trial dataset, patients enrolled in a clinical trial are selected according to specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Clearly, patients with longer-duration heart failure are “survivors” and patients with de novo HF were excluded in DAPA-HF. HF duration was documented categorically in the database, hence could not be assessed as a continuous variable. We did not have independent verification of HF duration as it was reported by the investigators.

Summary and conclusions

In summary, patients with longer-duration HF were older and more comorbid. Despite this, dapagliflozin was as well tolerated as placebo in patients with longer-duration HF. Patients with longer-duration HF had more severe symptoms and higher rates of worsening HF and death. However, the benefits of dapagliflozin were consistent irrespective of HF duration, with greater absolute benefits obtained in patients with longer-duration HF.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Little is known about outcomes in patients with longer-standing compared to shorter-duration heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and whether they obtain the same benefits and tolerate new therapies as well as patients with more recently diagnosed HFrEF.

To examine these questions, we examined outcomes in patients with HFrEF duration categorized as ≥2 to ≤12 months, >1-2 years, >2-5 years and >5 years in the Dapagliflozin And Prevention of Adverse-outcomes in Heart Failure trial (DAPA-HF).

We found that patients with longer-duration HFrEF were older with more comorbidity and had higher event rates. However, these patients obtained a similar relative reduction in risk with dapagliflozin, and a greater absolute risk reduction, compared to patients with more recently diagnosed HFrEF.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Although it might be assumed that patients with long-standing HFrEF are “stable” and might have little to gain from additional therapy, neither of these assumptions are true.

The SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin was well tolerated and effective even in patients with HFrEF of ≥5 years duration, with a number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one individual experiencing the primary endpoint of only 18 over the median duration of the trial (18.2 months).

Sources of Funding

The DAPA-HF trial was funded by AstraZeneca. Prof McMurray is supported by British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence Grant RE/18/6/34217.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Drs. Yeoh and Dewan have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Jhund’s employer (University of Glasgow) is paid by AstraZeneca for involvement in the DAPA-HF trial. He has also received consulting, advisory board, and speaker’s fees from Novartis, advisory board fees from Cytokinetics, and a grant from Boehringer Ingelheim; Dr. Inzucchi, received advisory fees from AstraZeneca and Zafgen, lecture fees, consulting fees, fees for serving as a clinical-trial publications committee member, reimbursement for medical writing, and travel support from Boehringer Ingelheim, fees for serving on a steering committee and travel support from Sanofi–Lexicon, lecture fees, consulting fees, and travel support from Merck, and advisory fees and travel support from vTv Therapeutics and Abbott–Alere; Dr. Køber, received lecture fees from Novartis and Bristol-Myers Squibb; Dr. Kosiborod, received grant support, honoraria, and research support from AstraZeneca, grant support and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, and honoraria from Sanofi, Amgen, Novo Nordisk, Merck (Diabetes), Eisai, Janssen, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Glytec, Intarcia Therapeutics, Novartis, Applied Therapeutics, Amarin, and Eli Lilly; Dr. Martinez has received personal fees from AstraZeneca as honoraria for being an Executive Committee Member for DAPA-HF. Dr. Ponikowski was an investigator in the DAPA-HF trial and received personal fees from AstraZeneca for lectures and consultancy related to the trial. He has also participated in clinical trials and received research grants to his institute and personal fees for speakers bureau and consultancy from Vifor Pharma. He has participated in clinical trials and received personal fees for consultancy and speakers bureaus from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cibiem, Novartis, and RenalGuard, personal fees for speakers bureaus and consultancy from Servier and Respicardia, personal fees for speakers bureaus from Berlin-Chemie, and personal fees for lectures from Pfizer. Dr. Sabatine received grant support (paid to Brigham and Women’s Hospital) and consulting fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Intarcia Therapeutics, Janssen Research and Development, the Medicines Company, MedImmune, Merck, and Novartis, receiving consulting fees from Anthos Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CVS Caremark, DalCor Pharmaceuticals, Dyrnamix, Esperion, IFM Therapeutics, and Ionis Pharmaceuticals, receiving grant support (paid to Brigham and Woman’s Hospital) from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Poxel, Quark Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceutical, and serving as a member of the TIMI Study Group, which receives grant support (paid to Brigham and Women’s Hospital) from Abbott, Aralez Pharmaceuticals, Roche, and Zora Biosciences; Dr Solomon has received a grant to his institution from AstraZeneca for being an Executive Committee Member for DAPA-HF and has received grants to his institute and personal fees for consulting from Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, MyoKardia, Novartis, Theracos, and Bayer, has received grants to his institute from Bellerophon, Celladon, Ionis, Lone Star Heart, Mesoblast, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (National Institutes of Health), and Sanofi Pasteur, and personal fees for consulting from Akros, Corvia, Ironwood, Merck, Roche, Takeda, Quantum Genomics, and AoBiome. Drs. Bengtsson and Sjöstrand are employed by AstraZeneca; and Dr. Langkilde, is employed by and holds shares in AstraZeneca. Prof. McMurray’s employer has been paid by Cardiorentis for his time spent as Steering Committee member and Endpoint Committee Chair and related meetings, and he has received nonfinancial support for travel and accommodation for some related meetings. Prof. McMurray’s employer has been paid by Amgen, Oxford University/Bayer, Abbvie, and Bristol Myers Squibb for his time spent as a Steering Committee member and related meetings, and he has received nonfinancial support for travel and accommodation for some related meetings. Prof. McMurray’s employer has been paid by Kings College Hospital/Kidney Research UK/Vifor-Fresenius for his time spent as a Steering Committee member and for running an Endpoint Adjudication Committee and related meetings, and he has received nonfinancial support for travel and accommodation for some related meetings. Prof. McMurray’s employer has been paid by Theracos for his time spent as Principal Investigator and related meetings, and he has received nonfinancial support for travel and accommodation for some related meetings. Prof. McMurray’s employer has been paid by Pfizer and Merck for his time spent on the Data Safety Monitoring Committee and related meetings. Prof. McMurray’s employer has been paid by Novartis for his time spent as Executive/Steering Committee member, Co-Principal Investigator, and Advisory Board member, and he has received nonfinancial support for travel and accommodation for some related meetings/presentations. Prof. McMurray’s employer has been paid by Bayer for his participation as a Steering Committee member, by DalCor Pharmaceuticals for his participation as a Steering Committee member (and related meetings), and by Bristol Myers Squibb for his participation as a Steering Committee member (and related meetings). Prof. McMurray’s employer has been paid by GlaxoSmithKline for his participation as a Steering Committee member and Co-Principal Investigator, and he has received nonfinancial support for travel and accommodation for some related meetings. All payments for meetings-related travel and accommodation were made through a Consultancy with University of Glasgow, and Prof. McMurray has not received personal payments in relation to any trials/drugs.

References

- 1.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Bělohlávek J, et al. DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böhm M, Komajda M, Borer JS, Ford I, Maack C, Tavazzi L, Moyne A, Swedberg K. SHIFT Investigators. Duration of chronic heart failure affects outcomes with preserved effects of heart rate reduction with ivabradine: findings from SHIFT. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:373–381. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeoh SE, Dewan P, Desai AS, Solomon SD, Rouleau JL, Lefkowitz M, Rizkala A, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Jhund PS, et al. Relationship between duration of heart failure, patient characteristics, outcomes and effect of therapy in PARADIGM-HF. ESC Heart Fail. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12972. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMurray JJV, DeMets DL, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, Martinez FA, Bengtsson O, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, et al. DAPA-HF Committees and Investigators. A trial to evaluate the effect of the sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (DAPA-HF) Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:665–675. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMurray JJV, DeMets DL, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, Martinez FA, Bengtsson O, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, et al. DAPA-HF Committees and Investigators. The Dapagliflozin And Prevention of Adverse-outcomes in Heart Failure (DAPA-HF) trial: baseline characteristics. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1402–1411. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med. 1985;4:87–90. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780040112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahimi K, Bennett D, Conrad N, Williams TM, Basu J, Dwight J, Woodward M, Patel A, McMurray JJ, MacMahon S. Risk prediction in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:440–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristensen SL, Martinez F, Jhund PS, Arango JL, Bělohlávek J, Boytsov S, Cabrera W, Gomez E, Hagège AA, Huang J, et al. Geographic variations in the PARADIGM-HF heart failure trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3167–3174. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Yang I, Ying Z. Semiparametric regression for the mean and rate functions of recurrent events. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 2000;62:711–730. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosiborod MN, Jhund PS, Docherty KF, Diez M, Petrie MC, Verma S, Nicolau JC, Merkely B, Kitakaze M, DeMets DL, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on symptoms, function, and quality of life in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: results from the DAPA-HF trial. Circulation. 2020;141:90–99. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene SJ, Hernandez AF, Dunning A, Ambrosy AP, Armstrong PW, Butler J, Cerbin LP, Coles A, Ezekowitz JA, Metra M, et al. Hospitalization for Recently Diagnosed Versus Worsening Chronic Heart Failure: From the ASCEND-HF Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:3029–3039. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pranata R, Tondas AE, Yonas E, Vania R, Yamin M, Chandra A, Siswanto BB. Differences in clinical characteristics and outcome of de novo heart failure compared to acutely decompensated chronic heart failure - systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Cardiol. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1080/00015385.2020.1747178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Younis A, Mulla W, Goldkorn R, Klempfner R, Peled Y, Arad M, Freimark D, Goldenberg I. Differences in Mortality of New-Onset (De-Novo) Acute Heart Failure Versus Acute Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butt JH, Fosbøl EL, Gerds TA, Andersson C, McMurray JJV, Petrie MC, Gustafsson F, Madelaire C, Kristensen SL, Gislason GH, et al. Readmission and death in patients admitted with new-onset versus worsening of chronic heart failure: insights from a nationwide cohort. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1800. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan MS, Butler J, Greene SJ. The real world of de novo heart failure: the next frontier for heart failure clinical trials? Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1844. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.