Abstract

The ongoing pandemic spread of a novel human coronavirus, SARS-COV-2, associated with severe pneumonia disease (COVID-19), has resulted in the generation of tens of thousands of virus genome sequences. The rate of genome generation is unprecedented, yet there is currently no coherent nor accepted scheme for naming the expanding phylogenetic diversity of SARS-CoV-2. We present a rational and dynamic virus nomenclature that uses a phylogenetic framework to identify those lineages that contribute most to active spread. Our system is made tractable by constraining the number and depth of hierarchical lineage labels and by flagging and de-labelling virus lineages that become unobserved and hence are likely inactive. By focusing on active virus lineages and those spreading to new locations this nomenclature will assist in tracking and understanding the patterns and determinants of the global spread of SARS-CoV-2.

There are currently more than 35,000 publicly available complete or near-complete genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 (as of 1st June 2020) and the number continues to grow. This remarkable achievement has been made possible by the rapid genome sequencing and online sharing of SARS-CoV-2 genomes by public health and research teams worldwide. These genomes have the potential to provide invaluable insights into the ongoing evolution and epidemiology of the virus during the pandemic, and will likely play an important role in surveillance and its eventual mitigation and control. Despite such a wealth of data, there is currently no coherent system for naming and discussing the growing number of phylogenetic lineages that comprise the population diversity of this virus, with conflicting ad hoc and informal systems of virus nomenclature in circulation. A nomenclature system for the genetic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 (a clade within the species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related virus, sub-genus Sarbecovirus, genus Betacoronavirus, family Coronaviridae 1) is urgently required before scientific literature and communication become further confused.

There is no universal approach to classifying virus genetic diversity below the level of a virus species2, and this is not covered by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Typically, genetic diversity is categorised into distinct ‘clades’, each of which corresponds to a monophyletic group on a phylogenetic tree. These clades may be referred to by a variety of terms, such as ‘subtypes’, ‘genotypes’, ‘groups’, depending on the taxonomic level under investigation or the established scientific literature for the virus in question. The clades usually reflect an attempt to divide pathogen phylogeny and genetic diversity into a set of groupings that are approximately equally divergent, mutually exclusive and statistically well supported. All genome sequences are therefore allocated to one clade or provisionally labelled as ‘unclassified’. Often multiple hierarchical levels of classification exist for the same pathogens, such as the terms ‘type’, ‘group’ and ‘subtype’ that are used in the field of HIV research.

Such classification systems are useful for discussing epidemiology and transmission when the number of taxonomic labels remains roughly constant through time; this is the case for slowly-evolving pathogens (for example, many bacteria) and for rapidly-evolving viruses with low rates of lineage turnover (for example, HIV3 and HCV4). In contrast, some rapidly-evolving viruses such as influenza A are characterised by high rates of lineage turnover, so that the genetic diversity circulating in any particular year largely emerges out of and replaces the diversity present in the preceding few years. For human seasonal influenza, this behaviour is the result of strong natural selection among competing lineages. In such circumstances a more explicitly phylogenetic classification system is used; for example, avian influenza viruses are classified into ‘subtypes’, ‘clades’ and ‘higher order clades’ according to several quantitative criteria5. Such a system can provide a convenient way to refer to the emergence of new (and potentially antigenically-distinct) variants and is suitable for the process of selecting the component viruses for the regularly-updated influenza vaccine. A similar approach to tracking antigenic diversity may be needed to inform SARS-CoV-2 vaccine design efforts. While useful, we recognise that dynamic nomenclature systems based on genetic distance thresholds have the potential to over-accumulate cumbersome lineage names.

In an ongoing and rapidly changing epidemic, such as SARS-CoV-2, a nomenclature system can facilitate real-time epidemiology by providing commonly-agreed labels to refer to viruses circulating in different parts of the world, thereby revealing the links between outbreaks that share similar virus genomes. Further, a nomenclature system is needed to describe virus lineages that vary in phenotypic or antigenic properties (although it must be stressed that at present there is no conclusive evidence of such variation among currently available SARS-CoV-2 strains).

Principles of a dynamic nomenclature system

There are a number of key challenges in the development of a dynamic and utilitarian nomenclature system for SARS-CoV-2. To be valid and broadly accepted a nomenclature needs to: (i) capture local and global patterns of virus genetic diversity in a timely and coherent manner, (ii) track emerging lineages as they move among countries and between populations within each country, (iii) be sufficiently robust and flexible to accommodate new virus diversity as it is generated, and (iv) be dynamic, such that it is able to incorporate both the birth and death of viral lineages through time.

A special challenge in the case of COVID-19 is that genome sequence data is being generated rapidly and at high volumes, such that by the end of the pandemic we can expect hundreds of thousands of SARS-CoV-2 genomes to have been sequenced. Any lineage naming system must therefore be capable of handling tens to hundreds of thousands of virus genomes sampled longitudinally and densely through time. Further, to be practical, any lineage naming system should have no more than one or two hundred active lineage labels, as any more would obfuscate rather than clarify discussion and will be difficult to conceptualise.

To fulfil these requirements we propose a workable and practical lineage nomenclature for SARS-CoV-2 that arises from a set of fundamental evolutionary and phylogenetic principles. Some of these principles are, necessarily, specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting the new reality of large-scale real-time generation of virus genome sequences. The nomenclature system is not intended to represent every evolutionary change in SARS-CoV-2, as these will number many thousand by the end of the pandemic. Instead, the focus is on genetic changes associated with important epidemiological and biological events. Fortunately, because of the early sampling and genome sequencing of COVID-19 cases in China, especially in Hubei province, it appears that the ‘root sequence’ of SARS-CoV-2 is known. Many of the genomes from the earliest sampled cases are genetically identical and hence also likely identical to the most recent common ancestor of all sampled viruses. This occurrence is different to previous viruses and epidemics and provides some advantages for the development of a rational and scalable classification scheme. Specifically, setting the ‘reference sequence’ to be the ‘root sequence’ forms a natural starting point, as direct comparisons in the number and position of mutations can be made with respect to the root sequence.

During the early phase of the pandemic, it will be possible to unambiguously assign a genome to a lineage through the presence/absence of particular sets of mutations. However, a central component of a useful nomenclature system is that it focuses on those virus lineages that contribute most to global transmission and genetic diversity. Hence, rather than naming every new possible lineage, classification should focus on those that have exhibited onward spread in the population, particularly those that have seeded an epidemic in a new location. For example, the large epidemic in Lombardy, northern Italy, thought to have begun in early February6, has since been disseminated to other locations in northern Europe and elsewhere.

Further, because SARS-CoV-2 genomes are being generated continuously and at a similar pace to changes in virus transmission and epidemic control efforts, we expect to see a continual process of lineage generation and extinction through time. Rather than maintaining a cumulative list of all lineages that have existed since the start of the pandemic, it is more prudent to mark lineages as ‘active’, ‘unobserved’, or ‘inactive’, a designation reflecting our current understanding of whether they are actively transmitting in the population or not. Accordingly, lineages of SARS-CoV-2 documented within the last month are defined here as ‘active’, those last seen >1 month but <3 months ago are classified as ‘unobserved’, and those that have not been seen for >3 months are termed ‘inactive’.

Although this strategy will allow us to track those lineages that are contributing most to the epidemic, and so reduce the number of names in use, it is important to keep open the possibility that new lineages will appear through the generation of virus genomes from unrepresented locations or from cases with travel history from such locations. For example, the epidemic in Iran, designated B.4 in our system, was identified via returning travellers to other countries7. Further, lineages that have not been seen for some time may re-emerge after a period of cryptic transmission in a region. Hence, it is possible for lineages that were previously classified as inactive or unobserved to be later re-labelled as active. We choose the term lineages (rather than ‘clades’, ‘genotypes’ or other designations) for SARS-CoV-2 as it captures the fact that they are dynamic, rather than relying on a static and exclusive hierarchical structure.

Lineage naming rules

We propose that major lineage labels begin with a letter. At the root of the phylogeny of SARS-CoV-2 are two lineages that we simply denote as lineages A and B. The earliest lineage A viruses, such as Wuhan/WH04/2020 (EPI_ISL_406801), sampled on 2020-01-05, share two nucleotides (positions 8782 in ORF1ab and 28144 in ORF8) with the closest known bat viruses (RaTG13 and RmYN02). Different nucleotides are present at those sites in viruses assigned to lineage B, of which Wuhan-Hu-1 (GenBank accession MN908947) sampled on 2019-12-26 is an early representative. Hence, although viruses from lineage B happen to have been sequenced and published first8–10, it is likely (based on current data) that the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of the SARS-CoV-2 phylogeny shares the same genome sequence as the early lineage A sequences (e.g. Wuhan/WH04/2020). Importantly, this does not imply that the MRCA itself has been sampled and sequenced, but rather that no mutations had accrued between the MRCA and the early lineage A genome sequences. At the time of writing, viruses from both lineages A and B are still circulating in many countries around the world, reflecting the exportation of viruses from Hubei to other regions of China and elsewhere before the strict travel restrictions and quarantine measures were imposed there.

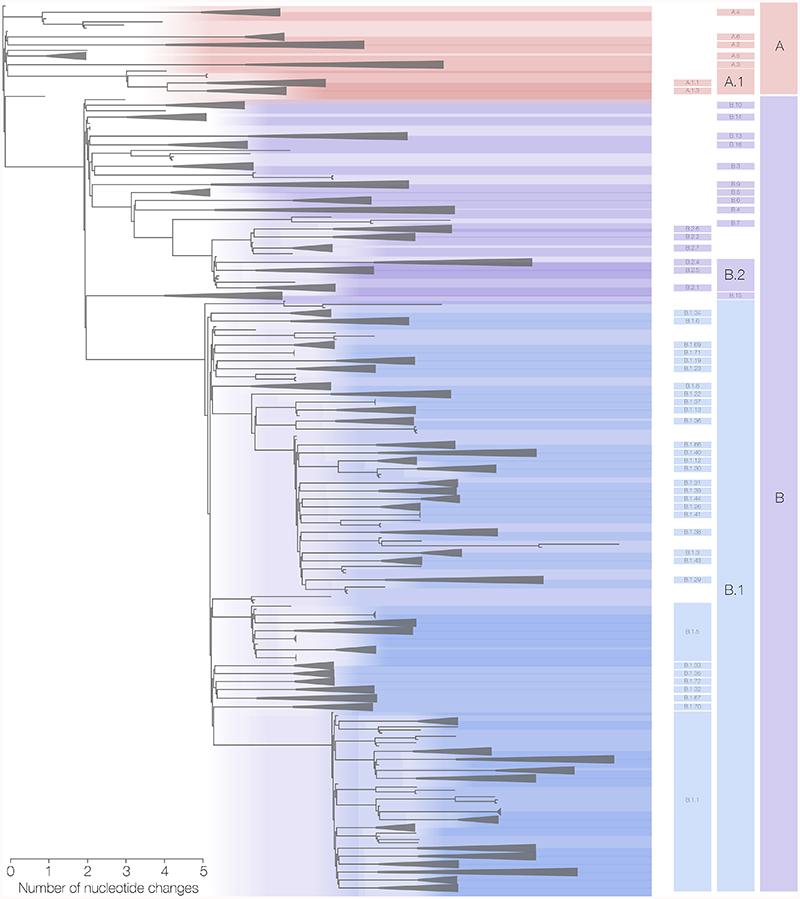

To add further lineage designations we downloaded 27,767 complete SARS-CoV-2 genomes from the GISAID database11 on 18th May, 2020 and estimated a maximum likelihood tree for these data (see Methods) (Fig. 1). We defined further SARS-CoV-2 lineages, each of which descends from either lineage A or B and is assigned a numerical value (e.g. lineage A.1, or lineage B.2). Lineage designations were made using the following set of conditions:

Each descendent lineage should show phylogenetic evidence of emergence from an ancestral lineage into another geographically distinct population, implying substantial onward transmission in that population. In the case of a rapidly expanding global lineage the recipient ‘population’ may comprise multiple countries. In the case of large and populous countries it may represent a new region or province. To show phylogenetic evidence a new lineage must meet all of the following criteria: (a) it exhibits one or more shared nucleotide differences from the ancestral lineage, (b) it comprises at least five genomes with >95% of the genome sequenced, (c) genomes within the lineage exhibit at least one shared nucleotide change among them, and (d) a bootstrap value >70% for the lineage defining node. Importantly, criterion (c) helps to focus attention only on lineages with evidence of on-going transmission.

The lineages identified in step (I) can themselves act as ancestors for virus lineages that then emerge in other geographic areas or at later times, provided they satisfy criteria a-d above. This results in a new lineage designation (e.g. A.1.1).

The iterative procedure in step II can proceed for a maximum of three sublevels (e.g. A.1.1.1) after which new descendent lineages are given a letter (in English alphabetical sequence from C, so A.1.1.1.1 would become C.1 and A.1.1.1.2 would become C.2. The rationale for this is that the system is intended only for tracking currently circulating lineages, such that we do not try to capture the entire history of a lineage in its label (that complete history can be obtained by reference to a phylogeny). At the time of writing no C level lineages have been assigned.

All sequences are assigned to one lineage. For example, if a genome does not meet the criteria for inclusion in a ‘higher level’ lineage (e.g. A.1.2, B.1.3.5) then it is automatically classified into the lowest level for which it does meet the inclusion criteria, which ultimately is ‘A’ or ‘B’.

Fig. 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny of globally sampled sequences of SARS-CoV-2 downloaded from the GISAID database (http://gisaid.org) on May 18th 2020. Five representative genomes are included from each of the defined lineages. The largest lineages that are defined by our proposed nomenclature system are highlighted with coloured areas and labelled on the right. The remaining lineages defined by the nomenclature system are denoted by triangles. The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide changes within the coding region of the genome.

Using this scheme we identified 81 viral lineages. These lineages mostly belong to A, B and B.1. We identified six lineages derived from lineage A (denoted A.1-A.6) and two descendant sub-lineages of A.1 (A.1.1 and A.3). We also describe 16 lineages directly derived from lineage B. To date, lineage B.1 is the predominant known global lineage and has been subdivided into > 70 sub-lineages. Lineage B.2 currently has six descendant sub-lineages. We are not yet able to further subdivide the other lineages even though some contain very large numbers of genomes. This is because many parts of the world experienced numerous imported cases followed by exponential growth in local transmission. We provide descriptions of these initial lineages, including their geographical locations and time span of sampling, in Table 1. We have also tried to be flexible with the criteria where, for example, the bootstrap value is below 70% but there is strong prior evidence that the lineage exists and is epidemiologically important. In particular, the Italian epidemic comprises two large lineages in our scheme – B.1 and B.2 – reflecting genomes from Italy as well as from large numbers of travellers from these regions and that fall into both lineages.

Table 1.

Proposed nomenclature of early major lineages of SARS-CoV-2. See https://cov-lineages.org/ for full details of each lineage.

| Lineage | Genomes | Date range | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 223 | Jan-05, Apr-27 | Root of the pandemic lies in this lineage, many Chinese sequences with global exports |

| A.1 | 1116 | Feb-20, Mar-25 | Primary outbreak in Washington State, USA |

| A.2 | 295 | Feb-26, Apr-27 | European lineage |

| A.3 | 191 | Jan-28, Apr-21 | USA lineage |

| A.5 | 118 | Feb-23, Apr-26 | European lineage |

| B | 1713 | Dec-24, May-03 | Base of this lineage lies in China with a lot of global travel between multiple locations |

| B.1 | 7438 | Jan-24, May-10 | Comprises the large Italian outbreak, now represents many European outbreaks, with travel within Europe and from Europe to the rest of the world |

| B.1.1 | 6286 | Feb-15, May-09 | Major European lineage, exports to the rest of the world from Europe |

| B.2 | 917 | Feb-13, May-04 | With B.1, comprises the large Italian outbreak |

| B.3 | 752 | Feb-23, Apr-23 | UK lineage |

| B.4 | 258 | Jan-18, Apr-14 | Likely the primary Iranian outbreak |

A unique and important aspect of our proposed nomenclature is that the status of the currently circulating lineages be assessed at regular intervals, with decisions made about identifying new lineages and flagging those we believe are likely be ‘unobserved’ or ‘inactive’ because none of their members have been sequenced for a considerable time. The names of unobserved or inactive lineages will not be reassigned. These are provisional timescales and the category thresholds may be altered in the future once the dynamics of lineage generation and extinction are better understood. When visualising the epidemic we suggest that these lineages should be no longer labelled to reduce both the number of names in circulation and visual noise, and to focus on the current epidemiological situation.

Discussion

While we regard this proposed nomenclature as practical and robust, it is important to recognise that phylogenetic inference carries statistical uncertainty and much of the available genome data is noisy, with incomplete genome coverage and errors arising from the amplification and sequencing processes. We have proposed a genome coverage threshold for proposing new lineages (see above), and we further suggest that sequences are not ascribed a lineage designation unless the genome coverage of that sequence exceeds 70% of the coding region. As noted above, when SARS-CoV-2 genetic diversity is low during the early pandemic period, there will be a direct association between lineage assignation and the presence of particular sets of mutations (with respect to the root sequence). This should help with the development of rapid, algorithmic genome labelling tools. This task will become more complex, but still tractable, as SARS-CoV-2 genetic diversity accumulates, increasing the chance of both homoplasies and reverse mutations. Classification algorithms based on lists of ‘lineage-defining’ mutations may be practical if they are frequently cross-checked and validated against phylogenetic estimations, but will not be as powerful as phylogenetic classification methods that make use of complete genome sequence data to identify relationships. We encourage the research community to develop software and online tools that will enable the automated classification of newly-generated genomes (one such implementation is pangolin, https://github.com/hCoV-2019/pangolin).

Coronaviruses also frequently recombine, meaning that a single phylogenetic tree may not always adequately capture the evolutionary history of SARS-CoV-2. Although this can make phylogenetic analysis challenging, recombination is readily accommodated within this system of lineage naming and assignment. A distinct recombination event, if it establishes onward transmission, will create a new viral lineage with a distinct common ancestor. Because this new lineage doesn’t have a single ancestral lineage they will be assigned the next available alphabetical prefix.

While we believe that our proposed lineage nomenclature will greatly assist those working with COVID-19, we do not see it as exclusive to other naming systems, particularly those that are specifically intended to track lineages circulating within individual countries for which a finer scale will be helpful. Indeed, there are likely to be strong sampling biases toward particular countries. Further, we note that future genome sequence generation may require adjustments to the current proposal, and any such changes will be detailed at http://cov-lineages.org/. We envisage, however, that the general approach described here may be readily adopted for these purposes, and also for other viral epidemics where real-time genomic epidemiology is being undertaken. We expect that this dynamic nomenclature will be most useful for the duration of the global pandemic, which may last a few years. After that time, SARS-CoV-2 will be either globally eliminated or, more likely, become an endemic or seasonal infection. The remaining endemic/seasonal lineages, which will by then be genetically distinct, can simply retain in the post-pandemic period their names from the dynamic nomenclature system.

Methods

We downloaded all SARS-CoV-2 genomes (at least 29,000bp in length) from GISAID on May 18th 2020. We trimmed the 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions and retained those genomes with at least 95% coverage of the reference genome (Wuhan-Hu-2019, GenBank accession MN908947). We aligned these sequences using MAFFT’s FFT-NS-2 algorithm and default parameter settings12. We then estimated a maximum likelihood tree using IQ-TREE 213 using the GTR+Γ model of nucleotide substitution14,15, default heuristic search options, and ultrafast bootstrapping with 1000 replicates16.

The maximum likelihood tree and associated sequence metadata were manually curated and the phylogeny was annotated with the lineage designations. This annotated tree, along with a table providing the lineage designation for each genome in the data set, is available for download at http://cov-lineages.org/. We also provide a high-resolution PDF figure of the entire tree labelled with lineages. These will be updated on a regular basis. Representative sequences from each lineage were selected to maximise within-lineage diversity and to minimise N-content and used to construct the maximum likelihood tree shown in Figure 1.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (Collaboration Award 206298/Z/17/Z, ARTIC-Network), the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 725422-ReservoirDOCS) and the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ European Research Council (grant agreement no. 614725-PATHPHYLODYN), the UK COVID-19 Genomics Consortium (CoG-UK), the Oxford Martin School, and the Australian Research Council (FL170100022).

Footnotes

Author Contributions. A.R., E.C.H. and O.G.P. conceived, designed and supervised the study. A.O’T., J.T.M. and A.R. developed phylogenetic methods. A.R., A.O’T., V.H. J.T.M., C.R., L. du P. and O.G.P. analysed and interpreted the virus genomes. A.R., E.C.H., A.O’T., V.H. and O.G.P. wrote the paper, with input from other authors.

Competing interests. The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

No supplementary Information is available for this paper.

Code availability statement

Details of software and source code that implement the nomenclature system reported here are available at http://cov-lineages.org.

Data availability statement

No new data are reported. Virus genome sequences used here are publicly available from http://gisaid.org. A table of acknowledgements for the GISAID genome sequences used to develop this work is available at https://raw.githubusercontent.com/hCoV-2019/lineages/master/gisaid_acknowledgements.tsv

References

- 1.ICTV. Changes to virus taxonomy and the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2019) Arch Virol. 2019;2164:2417–2429. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04306-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ICTV. ICTV Code: The International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature. 2018 https://talk.ictvonline.org/information/w/ictv-information/383/ictv-code/

- 3.Robertson DL, et al. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. Science. 2000;288:55–56. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.55d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DB, et al. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology. 2014;59:318–327. doi: 10.1002/hep.26744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO/OIE/FAO H5N1 Evolution Working Group. Continued evolution of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1): Updated nomenclature. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00298.x. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zehender G, et al. Genomic characterisation and phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in Italy. J MedVirol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25794. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eden J-S, et al. An emergent clade of SARS-CoV-2 linked to returned travellers from Iran. Virus Evol. 2020;6:veaa027. doi: 10.1093/ve/veaa027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu R, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu F, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu N, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New Eng J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shu Y, McCauley J. GISAID: Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data - from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22:30494. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K-I, Miyata T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nuc Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–66. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minh BQ, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tavaré S. Lectures on mathematics in the life sciences. Vol. 17. American Mathematical Society; 1986. Some mathematical questions in biology: DNA sequence analysis; pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Z. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic estimation from DNA sequences with variable rates over sites: approximate methods. J Mol Evol. 1994;39:306–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00160154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minh BQ, Nguyen MAT, von Haeseler A. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1188–1195. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Details of software and source code that implement the nomenclature system reported here are available at http://cov-lineages.org.

No new data are reported. Virus genome sequences used here are publicly available from http://gisaid.org. A table of acknowledgements for the GISAID genome sequences used to develop this work is available at https://raw.githubusercontent.com/hCoV-2019/lineages/master/gisaid_acknowledgements.tsv