Abstract

Channelopathies are a diverse group of human disorders that are caused by mutations in genes coding for ion channels or channel-regulating proteins. Several dozen channelopathies have been identified that involve both non-excitable cells as well as electrically active tissues like brain, skeletal and smooth muscle or the heart. In this review, we start out from the general question which ion channel genes are expressed tissue-selectively. We mined the human gene expression database Human Protein Atlas (HPA) for tissue-enriched ion channel genes and found 85 genes belonging to the ion channel families. Most of these genes were enriched in brain, testis and muscle and a complete list of the enriched ion channel genes is provided. We further focused on the tissue distribution of voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC) genes including different brain areas and the retina based on the human gene expression from the FANTOM5 dataset. The expression data is complemented by an overview of the tissue-dependent aspects of L-type calcium channel (LTCC) function, dysfunction and pharmacology, as well as of their splice variants. Finally, we focus on the pathology of tissue-restricted LTCC channelopathies and their treatment options.

This article is part of the Special Issue entitled ‘Channelopathies.’

Keywords: Tissue expression, Calcium channel, Channelopathy, Retina, Congenitals stationary night blindness

1. Introduction

The physiology and functionality of cell types and tissues is based on the underlying gene expression diversity within the different body parts of a living being. The question arises which of these genes are ubiquitously expressed and which genes and combinations endow organs with their unique tissue identity. In channelopathies, i.e. human pathologies caused by dysfunction of ion channels, the tissue-dependence can profoundly affect disease manifestation and treatment options.

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) are interesting case examples of ion channels that have very selective or very widespread tissue distribution. VGCCs generate Ca2+ signals for many important physiological functions such as neurotransmission, muscle contraction, hormone secretion as well as regulation of gene expression (Catterall, 2011). Like other ion channels they form part of signaling complexes together with molecules, such as receptors, kinases, phosphatases and calmodulin (Catterall, 2011). Most VGCCs exist in a hetero-oligomeric complex of several subunits with the α1-subunit forming the Ca2+-selective channel pore. Their biophysical and pharmacological properties are determined by their α1-subunit. Based on structural and pharmacological similarities of their α1-subunits, VGCCs can be grouped into two major families: LTCCs (Cav1 family; Cav1.1-Cav1.4) and non-LTCCs (Cav2, Cav2.1-Cav2.3; Cav3 families, Cav3.1-Cav3.3). The ten different α1-subunit isoforms associate with different β-subunits (β1-4) and α2δ subunits (α2δ1-4) and in some cases alsoγ-subunits. For a detailed overview we refer to a recent review by Zamponi and colleagues (Zamponi et al., 2015).

LTCC channelopathies are particularly interesting because some show obvious signs of tissue-selective phenotypes, whereas others are caused by less focally expressed channel genes that nevertheless primarily affect certain tissues. As for example skeletal muscle diseases like malignant hyperthermia or hypokalemic periodic paralysis (Jurkat-Rott et al., 2002) are caused by mutations in the very tissue-selectively expressed CACNA1S gene that encodes for Cav1.1 LTCCs. Also the CACNA1F gene that translates into Cav1.4 LTCCs exhibits very selective expression in the retina and therefore shows a tissue-specific disease manifestation (Zeitz et al., 2015). In contrast the two other LTCC members, Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 do not show a similar restriction of expression localization. Of note, some of their associated channelopathies (e.g. Timothy syndrome in Cav1.2) also highlight aspects of splice variant expression differences and the importance of the cellular environment for a phenotypic exhibition.

As ‘channel diggers’ we would highly benefit from a better overview of the tissue-selectivity of gene expression and/or even cell specific expression to unearth their functional mysteries.

2. Tissue specificity in voltage-gated ion channel genes according to large-scale screenings

Details on ion channel expression in single cell types are slowly accumulating. However it is also worthwhile to look at the overall ion channel repertoires on the tissue level from human transcriptome and proteome screenings. Recently large-scale screenings of human gene expression in tissues have been undertaken by several consortiums that allow for a broader view on gene expression localization in the human body (for an overview (Uhlen et al., 2016)). Here we made use of two datasets, the Human Protein Atlas (www.proteinatlas.org; (Uhlen et al., 2015)) and FANTOM5 (fantom.gsc.riken.jp/5/; (Lizio et al., 2015)). Within the framework of the Human Protein Atlas (HPA), Illumina-sequencing of RNA (RNA-seq) was performed on 32 human tissues, capturing the mRNA levels of transcripts within each tissue. Although mRNA level to protein level ratios can vary between different gene products depending on e.g. translation rates and protein half-life (Eden et al., 2011), overall the data from RNA-seq is in good agreement with corresponding protein amounts (Wilhelm et al., 2014). The genes contained in the HPA are categorized according to their tissue-selective expression. Of the putative 19628 protein coding genes, 7367 genes were classified as expressed in all tissues, while 7835 genes showed elevated expression in subsets of tissues (3328 were mixed, 1098 not detected). The most selectively expressed subclass among the elevated genes are so-called tissue-enriched genes (defined by an expression value in the highest-expressing tissue that is at least five-fold of the second highest expression value; tissue specificity score TS ≥ 5).

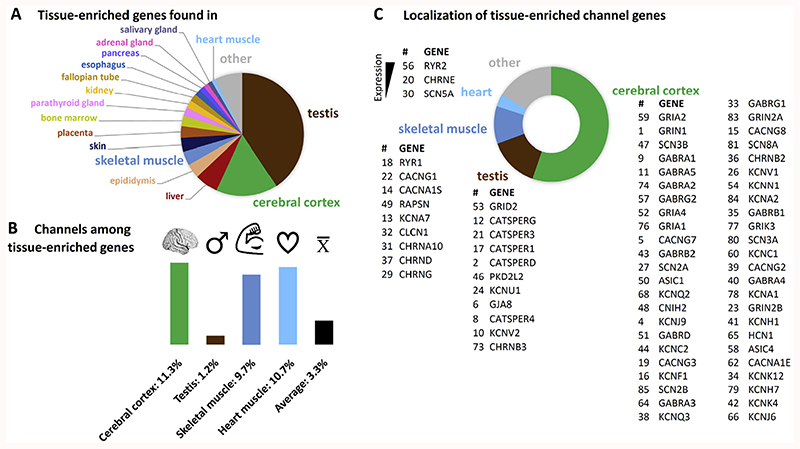

From the HPA list of 2547 tissue-enriched genes we pulled out the 85 genes that belong to the ion channel families (according to the IUPHAR ion channel list, (Southan et al., 2016)) to obtain an overview of which ion channels are expressed most selectively (Table 1) and could thus give rise to a tissue-specific ion channel function in health and disease. The majority of tissue-enriched ion channel genes were found in a low number of tissues. As expected, the four tissues with the most ion channel genes comprised electrically active tissues like cerebral cortex, skeletal muscle and heart, but also testis contained a number of selectively expressed ion channel genes (Fig. 1). Yet, the fraction of channel genes was different for these tissues. While testis contained the largest number of tissue-enriched genes (Fig. 1A), only few of those genes code for ion channels (Fig. 1B). Cerebral cortex, skeletal muscle and heart included a much higher fraction of ion channels that was comparable within these three tissues. Cerebral cortex displayed the second highest number of tissue-enriched genes, therefore most of the ion channels were indeed found there. In Fig. 1C the ion channel genes selectively expressed in cerebral cortex, testis, skeletal muscle and heart are summarized and sorted according to their expression strengths within the given tissue. The numbers refer to Table 1 to facilitate retrieval of additional information.

Table 1. List of tissue-enriched channel genes in human tissues.

We pulled out all ion channel genes (according to IUPHAR list of ion channel family members) from the dataset of tissue-enriched genes found in the Human Protein Atlas (HPA). Genes in the HPA tissue-enriched gene list have the highest selectivity of expression (expression in one tissue at least five-fold higher than all other tissues). In total, we found 85 channel genes, numbered from highest tissue specificity to lowest. Black squares indicate the tissue in which the gene is enriched. Abbreviations: a.k.a., also known as; TS, tissue specificity score; TPM, transcripts per million (expression strength in the indicated tissue). Note: TPM ≥1 is considered as “expressed”. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel subunits and directly associated channels are in bold, auxiliary/modulatory/regulatory subunits in italics. Human Protein Atlas version 16, Release date: 04.12.2016; Data retrieved on 10.01.2017.

| a.k.a | adrenal gland | cerebral cortex | epididymis | esophagus | fallopian tube | heart muscle | kidney | lung | pancreas | parathyroid gland | prostate | skeletal muscle | skin | stomach | testis | TS | TPM | Gene description | Ensembl(ENSG00000...) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMDAR1 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 1 | 176884 | |||||||||||||||||

| TMEMI46 | catsper channel auxiliary subunit delta | 174897 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kir1.1 | Potassium channel, inwardly rectifying subfamily J, member 1 | 151704 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kir3.3 | Potassium channel, inwardly rectifying subfamily J, member 9 | 162728 | |||||||||||||||||

| calcium channel, voltrge-dependent, grmmr subunit 7 | 105625 | ||||||||||||||||||

| CX50 | Gap junction protein, alpha 8, 50kDa | 121634 | |||||||||||||||||

| AQP12 | Aquaporin 12A | 184945 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cation channel, sperm associated 4 | 188782 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, alpha 1 | 022355 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kv8.2 | Potassium channel, voltage gated modifier subfamily V, member 2 | 168263 | |||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, alpha 5 | 186297 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ārtsper channel auxiliary subunit gamma | 099332 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kv1.7 | Potassium channel, voltage gated shaker related subfamily A, member 7 | 104848 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cav1.1 | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, alpha 1S subunit | 081248 | |||||||||||||||||

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, gamma subunit 8 | 142408 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kv5.1 | Potassium channel, voltage gated modifier subfamily F, member 1 | 162975 | |||||||||||||||||

| CATSPER | Cation channel, sperm associated 1 | 175294 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ryanodine receptor 1 (skeletal) | 196218 | ||||||||||||||||||

| channel, voltage-dependent, gamma subunit 3 | 006116 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ACHRE | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, epsilon (muscle) | 108556 | |||||||||||||||||

| CACRC | Cation channel, sperm associated 3 | 152705 | |||||||||||||||||

| CACNLG | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, gamma subunit 1 | !08877 | |||||||||||||||||

| NMDAR2B | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 2B | 273079 | |||||||||||||||||

| KCa5.1 | Potassium channel, subfamily U, member 1 | 215262 | |||||||||||||||||

| Potassium channel, voltage gated subfamily E regulatory beta subunit 2 | 159197 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kv8.1 | Potassium channel, voltage gated modifier subfamily V, member 1 | 164794 | |||||||||||||||||

| Nav1.2 | Sodium channel, voltage gated, type II alpha subunit | 136531 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 2 (neuronal) | 120903 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ACHRG | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, gamma (muscle) | 196811 | |||||||||||||||||

| Nav1.5 | Sodium channel, voltage gated, type V alpha subunit | 183873 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 10 (neuronal) | 129749 | ||||||||||||||||||

| CLC1 | Chloride channel, voltage-sensitive | 188037 | |||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, gamma 1 | 163285 | ||||||||||||||||||

| K2p12.1 | Potassium channel, two pore domain subfamily K, member 12 | 184261 | |||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, beta 1 | 163288 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, beta 2 (neuronal) | 160716 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ACHRD | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, delta (muscle) | 135902 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kv7.3 | Potassium channel, voltage gated KQT-like subfamily Q, member 3 | 184156 | |||||||||||||||||

| stargazi | Āalcium channel, voltage-dependent, gamma subunit 2 | 166867 | |||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, alpha 4 | 109158 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kv10.1 | Potassium channel, voltage gated eag related subfamily H, member 1 | 143473 | |||||||||||||||||

| K2p4.1 | Potassium channel, two pore domain subfamily K, member 4 | 182450 | |||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, beta 2 | 145864 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kv3.2 | Potassium channel, voltage gated Shaw related subfamily C, member 2 | 166006 | |||||||||||||||||

| Potassium channel regulator | 198553 | ||||||||||||||||||

| TRPP5 | Polycystic kidney disease 2-like 2 | 078795 | |||||||||||||||||

| Sodium channel, voltage gated, type III beta subunit | 166257 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Āornichon family CEEC receptor auxiliary protein 2 | 174877 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Deceptor-rssocirted protein of the synapse | 165917 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Acid sensing (proton gated) ion channel 1 | 110881 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, delta | 187730 | ||||||||||||||||||

| GluA4 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 4 | 152578 | |||||||||||||||||

| GluD2 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, delta 2 | 152208 | |||||||||||||||||

| KCa2.1 | Potassium channel, calcium activated subfamily N alpha, member 1 | 105642 | |||||||||||||||||

| CX26 | Gap junction protein, beta 2, 26kDa | 165474 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ryanodine receptor 2 (cardiac) | 198626 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, gamma 2 | 113327 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Acid sensing (proton gated) ion channel family member 4 | 072182 | ||||||||||||||||||

| GluA2 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 2 | 120251 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kv3.1 | Potassium channel, voltage gated Shaw related subfamily C, member 1 | 129159 | |||||||||||||||||

| Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 8 | 144481 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cav2.3 | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, R type, alpha 1E subunit | 198216 | |||||||||||||||||

| 48,2 | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 3 (neuronal) | 080644 | |||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, alpha 3 | 011677 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hyperpolarization activated cyclic nucleotide gated potassium channel 1 | 164588 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kir3.2 | Potassium channel, inwardly rectifying subfamily J, member 6 | 157542 | |||||||||||||||||

| K2p7.1 | Potassium channel, two pore domain subfamily K, member 7 | 173338 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kv7.2 | Potassium channel, voltage gated KQT-like subfamily Q, member 2 | 075043 | |||||||||||||||||

| Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 7 | 092439 | ||||||||||||||||||

| TMEM16C | Anoctamin 3 | 134343 | |||||||||||||||||

| Barttin CLCNK-type chloride channel accessory beta subunit | 162391 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, alpha 2/delta subunit 2 | ŨŨ74Ũ0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, beta 3 (neuronal) | 147432 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, alpha 2 | 151834 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, rho 1 | 146276 | ||||||||||||||||||

| GluA1 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 1 | 155511 | |||||||||||||||||

| GluK3 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, kainate 3 | 163873 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kv1.1 | Potassium channel, voltage gated shaker related subfamily A, member 1 | 111262 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kv11.3 | Potassium channel, voltage gated eag related subfamily H, member 7 | 184611 | |||||||||||||||||

| Nav1.3 | Sodium channel, voltage gated, type III alpha subunit | 153253 | |||||||||||||||||

| Nav1.6 | Sodium channel, voltage gated, type VIII alpha subunit | 196876 | |||||||||||||||||

| CX30.3 | Gap junction protein, beta 4, 30.3kDa | 189433 | |||||||||||||||||

| NMDAR2A | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 2A | 183454 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kv1.2 | Potassium channel, voltage gated shaker related subfamily A, member 2 | 177301 | |||||||||||||||||

| Sodium channel, voltage gated, type II beta subunit | 149575 |

Fig. 1. Localization of all tissue-enriched genes and of the tissue-enriched channel genes.

(A) The largest number of tissue-enriched genes were found in testis (brown) and cerebral cortex (green) samples (tissue-enriched genes are defined by at least five-fold higher expression in one tissue compared to the tissue with the second highest expression. Only tissues with ≥1% of the total number of tissue-enriched genes are labelled. (B) Within each tissue, a different fraction of tissue-enriched genes belong to the ion channel families. While the electrically active tissues (cerebral cortex, skeletal (dark blue) and heart muscle (light blue)) have a higher-than-average percentage of channel genes, in testis only a low fraction of the tissue-enriched genes are channels. (C) Most tissue-enriched channels are found in cerebral cortex (green), testis (brown) and skeletal muscle (dark blue). Genes are listed in order of their expression strength (highest expression (TPM) on top). The numbering refers to Table 1. All data was taken from the Human Protein Atlas (retrieved from www.proteinatlas.org on 11.01.2017).

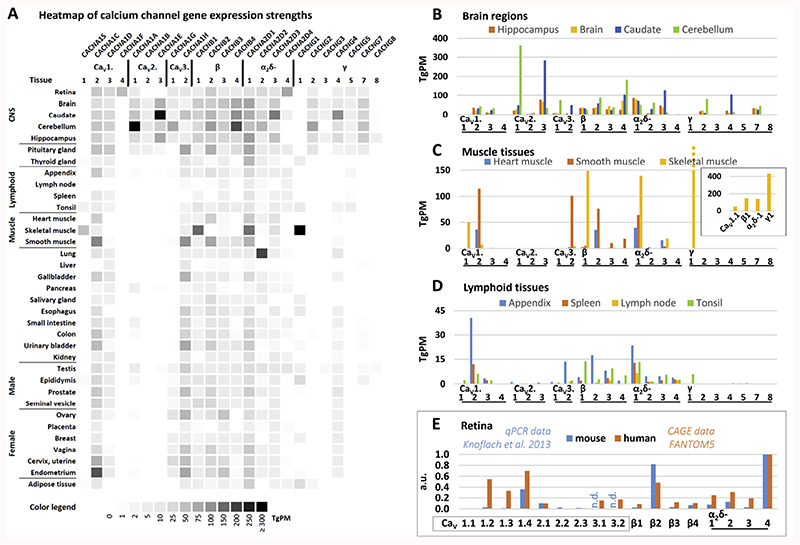

The dataset can be looked at in detail from different angles: which genes are found in a given tissue or which tissues express a certain gene? For the former we concentrated on VGCC expression in three different tissue subsets: brain regions, muscle tissues and lymphoid tissues (Fig. 2). It is evident that there is only partial selectivity of expression of individual VGCC subunits, e.g. CaV1.1 and CaV1.4 LTCCs which show a very restricted expression in skeletal muscle and retinal tissue, respectively (Fig. 2A). CaV2 channels and γ subunits showed an overall CNS-focused expression pattern. The most striking differences in the FANTOM5 brain samples were seen with respect to CaV2.1 which was highly expressed in the cerebellum and CaV2.3 that was most prominent in caudate (Fig. 2B). In general, the human data compared well with the data from mouse brain samples; e. g. evidence from quantitative RT-PCR analyses in hippocampal and cerebellar tissue found similar relationships in CaV2.1, CaV2.3, β4, α2δ-1 and α2δ-2 as in the FANTOM5 data, albeit e.g. CaV1.3 and β2 showed a different ratio (Schlick et al., 2010).

Fig. 2. VGCC gene expression in different human tissues and mouse retina.

(A) Heatmap of VGCC gene expression strengths across tissues. Darker hues indicate higher expression (TgPM = tags per million). Because the HPA dataset contained only a part of the brain (cerebral cortex) and no retinal samples, we chose FANTOM5 data for this comparison which were shown to highly correlate with the HPA (Yu et al., 2015b). Note that CaV3.3 and γ6 data was not available from FANTOM5 and using another database for the comparison of absolute values was not possible. (B) Expression of VGCCs in different brain regions. Note that “Brain” is a whole-brain sample. (C) Expression of VGCCs in muscle tissue. The inset shows the skeletal muscle calcium channel subunit encoding genes. Note the high abundance of γ1. (D) Expression of VGCCs in lymphoid tissues (E) Comparison of expression of VGCC in mouse and human retina. Data were normalized to α2δ-4. FANTOM5 data was retrieved through Human Protein Atlas website www.proteinatlas.org on 11.01.2017. VGCC nomenclature according to Catterall et al. (2005).

In the muscle tissues a clear-cut segregation in the use of LTCCs and β-subunits was apparent. In skeletal muscle: CaV1.1 and β1; in heart and smooth muscle: CaV1.2 and β2 while all muscle tissues are alike in their expression of α2δ-1 as the main α2δ subunit (Fig. 2C). Smooth muscle showed additionally high expression levels of CaV3.2 as has previously been demonstrated ((Harraz et al., 2015a; Harraz et al., 2015b), for review (Kuo et al., 2014). Other findings suggest that smooth muscle cells of the CNS vasculature also express Cav3.1 ((Fernandez et al., 2015), rat retina arterioles) and Cav3.3 (Harraz et al., 2015b), human cerebral arteries). The γ1 subunit was only found in skeletal muscle but with a striking abundance (see inset in Fig. 2C for comparison of skeletal muscle VGCC subunit expression strengths). Overall this expression map recapitulated well what is known about muscle tissue Ca2+ channel repertoires (Catterall et al., 2005).

LTCCs have been reported repeatedly also in cells of the lymphoid lineage, mainly in different types of T-cells (for an overview, see (Davenport et al., 2015; Badou et al., 2013)). In the FANTOM5 lymphoid tissues the only LTCCs with prominent expression were CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 (Fig. 2D). Both have been described previously (Cabral et al., 2010; Robert et al., 2014). CaV1.1 (Matza et al., 2016) and CaV1.4 (Robert et al., 2014) (Omilusik et al., 2011; McRory et al., 2004) have also been reported in immune cells/ tissues but were not detected in the FANTOM5 lymphoid tissues (with exception of a low amount of CaV1.1 in the tonsil tissue). It is unclear if this could be attributed to the activation state of the immune cells because CaV1.4 expression was reported in naive T-cells as well as upon activation (Omilusik et al., 2011), while a novel variant of CaV1.1 (lacking exon 29 like in embryonic skeletal muscle but with alternative N-terminal exons; Table 2 and see also below) was found in T-cells after T-cell receptor stimulation (Matza et al., 2016). Among auxiliary subunits, all β subunits as well as α2δ-2 have been described in immune cells (Robert et al., 2014; Jha et al., 2015; Cabral et al., 2010), which conforms to FANTOM5 lymphoid tissue data.

Table 2. Expression of VGCC α1 subunit splice variants.

Both tissue source and species are indicated. Existing channelopathies or specific interactions with drugs are indicated in bold (disease) or italic (pharmacology). Abbreviation: n.i., not indicated.

| α1 subunit | Splice variant | Tissue expression | Species | Disease pharmacology | Reference PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cav1.1 | Δ exon 29 | spleen (CD4 T cells) | mouse | 26815481 | |

| Δ exon 29 | muscle biopsy | human | Myotonic dystrophy type 1 and type 2 | 23888875 | |

| Δ exon 29 | muscle biopsy | human | Myotonic dystrophy type 1 and type 2 | 22140091 | |

| Δ exon 29 | muscle, primary myotubes, C2C12 line | Human mouse | 19134469 | ||

| Cav1.2 | Cavl.2e21+22 | heart | mouse | Cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure | 27731386 |

| Cav1.233L | heart (neonatal, adult) | mouse | 25694430 | ||

| 1896G>A | n.i. | human | Brugada syndrome | 24321233 | |

| Cavh2Δ73 | cardiovascular tissue | human | 23926129 | ||

| brain, A7r5 cells | rat | ||||

| Cav1.2Δ9* | aorta cDNA library | human | 21998324 | ||

| exons 8, 8a | cortex | mouse | Timothy Syndrome | 21282112 | |

| exons 8/8a, 9, 33 | cardiac and smooth muscle | n.i. | Diltiazem sensitivity | 20649567 | |

| exon 9* | cerebral artery myocytes | rabbit | 19717733 | ||

| exons 9*, 33 | embryonic cortex | mouse | 19564422 | ||

| exons 9*, 33 | heart | rat | Myocardial infarction rat model | 19263075 | |

| exons 1a, 1, 8a, 8, 9*, 21, 22,31,32, 32-6nt, 33 |

heart | rat | Hypertensive rat model | 18070605 | |

| exons 8/8a, 9, 33 | cardiac and smooth muscle | Nifedipine sensitivity | 17916557 | ||

| exon 9* | cartilage, bone, fat, liver, kidney, aorta, bladder, heart tissues, CNS | human | 15916803 | ||

| exon 9* | smooth muscle | rat | 15381693 | ||

| exons 21, 22 | brain | rat | Isradipine sensitivity | 7737988 | |

| a1C-a | heart | rat | Nisoldipine sensitivity | 9314833 | |

| a1C-b | aorta | ||||

| exons 8, 8a, 31, 32, 40–43 | n.i. | human | Isradipine sensitivity | 9607315 | |

| Cav1.3 | exons 42S, 42L, 43S, 43L | whole-brain, brain regions, inner ear, | human | 26379493 | |

| sinoatrial node | mouse | 21998310 | |||

| C-terminus | testis, heart, pancreas, kidney, lung | hamster | 21093409 | ||

| exon 43S | whole-brain, brain regions, heart, eye | human | 21998310 | ||

| mouse | |||||

| exons 42, 42S 43S, Δ41, Δ44, 48S | whole-brain, brain regions, spinal cord | mouse | 21998309 | ||

| exons 42, 42A | whole brain, brain regions | human | 18482979 | ||

| Cav1.3b | cortical neuron culture | rat | 17287512 | ||

| Cav1.3ΔIQ | cochlea inner hair cell | rat | 17050708 | ||

| Cav1.3a | striatal medium spiny neurons | mouse | 15689540 | ||

| Cav1.3b | |||||

| Cav1.31a | |||||

| Cav1.31b | |||||

| Cav1.2_/” cardiomyocyte | mouse | 12900400 | |||

| Cav1.3short | neuroendocrine cells, whole-brain, pituitary GH3 cells | rat | 11514547 | ||

| exons 31, 32 | ventricular myocytes | human | Heart failure | 10888251 | |

| IIIS2 | cochlea | chicken | 9405709 | ||

| 26 ins I –II | |||||

| 10 ins IVS2-S3 | |||||

| IVS3-IVS4 | whole-brain, heart, lung, aorta | rat | 9405178 | ||

| rCACN4A, 4B, C-terminus, I-II loop, IVS3-S4 | RINm5F cell line | rat | 7760845 | ||

| Cav1.4 | Δ exon 45, | retina | human | 27226626 | |

| Δ exon 47, | monkey | ||||

| Δ exon p45,47 | mouse | ||||

| transcript scanning | retina Marathon®-Ready cDNA | human | 22069316 | ||

| CaV1.4a, b | Jurkat T cells, peripheral blood T | human | 15899519 | ||

| exons 31 –34, 37 | lymphocytes, activated T cells | ||||

| Cav2.1 | C-terminus | neurosecretory cells | 24344901 | ||

| exons 46, 47 | n.i. | Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 | 21550405 | ||

| splicing mutations | blood samples | human | Episodic ataxia type 2 | 20129625 | |

| Δ exon 47 | n.i. | n.i. | Familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 | 19242091 | |

| Δ synprint | neuroendocrine cells | rat | 18390553 | ||

| Δ exon1 | whole-brain, cultured cells | ||||

| Δ exon 2 exon 47 ins | Purkinje and granule cells | human patient | Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 | 18835329 | |

| exons 37a, 37b | whole-brain, cerebellum | mouse | 17291689 | ||

| rat | |||||

| exons 28, 34, 47 | cerebellum, Purkinje neurons | rat | 16278278 | ||

| α1A-a, α1A-b | brain regions | rat | 10321243 | ||

| Cav2.2 | exons 18a, 24a, 31a, 37a, 37b | whole-brain, cerebellum dorsal root ganglion | mouse | 21150296 | |

| exons 37a, 37b | n.i. | mouse | Analgesic treatment | 24369063 | |

| exon 37a | dorsal root ganglia | mouse | 22836269 | ||

| exon 18a ins | hippocampus, | rat | Chronic inflammatory pain | 19125229 | |

| Δ exon 1 | spinal cord | ||||

| exons 18a, 24a, 31a, 37a, 37b | dorsal root ganglia | rat | 14715140 | ||

| Δ exon 1 | fetal and adult brain | human | 11756491 | ||

| Δ exon 2 | |||||

| II–III loop | superior cervical and dorsal root ganglia, spinal cord, brain regions | rat | 10864934 | ||

| synprint II-III loop | ventral mesencephalon | rat | 10501220 | ||

| IIIS3-S4 IVS3-S4 |

whole-brain, superior cervical ganglia | rat | 9010213 | ||

| α1E–L | retina, brain regions | rat | 9582423 | ||

| Cav3.1 | transcript scanning | whole-brain, thalamus, cortex, | mouse | Absence epilepsy | 19480703 |

| Δ exon 14 Δ exon26 |

cerebellum, hippocampus | (lethargic, tottering) | |||

| exons 25, 26 | dorsal thalamus | rat | 17707654 | ||

| exons 14, 25, 26, 34, 35, 38B | infant brain | human | 10548410 | ||

| Cav3.2 | ± exon 25 | heart tissues | Hypertension- associated cardiac hypertrophy | 20699644 | |

| Cav3.3 | exons 33, 34 | brain regions, pineal gland | rat | 12297319 |

Moreover we compared expression data of the human retina with mouse retina quantitative RT-PCR data from Knoflach et al. (2013) (Fig. 2E). To this end we normalized all expression values to the highest expressed gene, α2δ-4. While the quantitative expression values differed, the qualitative relationships between different VGCC subunits within each species were conserved. In both mouse and human retinas CaV1.4 was the most abundantly expressed pore-forming α1 subunit, CaV2.1 the most abundant CaV2 member and β2 was the main β subunit. The outcome for Cav1.4 and β2 is compelling confirming the suitability of mouse models for investigations in human Cav1.4 related channelopathies (see also below; (Zeitz et al., 2015)). The major difference between the two datasets lies in the high expression values for CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 in the human retina data. Most likely this can be explained by abundant RNA from retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in the samples used for FANTOM5, which is evident in the high expression values of RPE-specific genes (e.g. PMEL, RGR, RPE65) in the retina data set (not shown). In fact, both CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 have been found prominently in RPE (Wimmers et al., 2008; Muller et al., 2014).

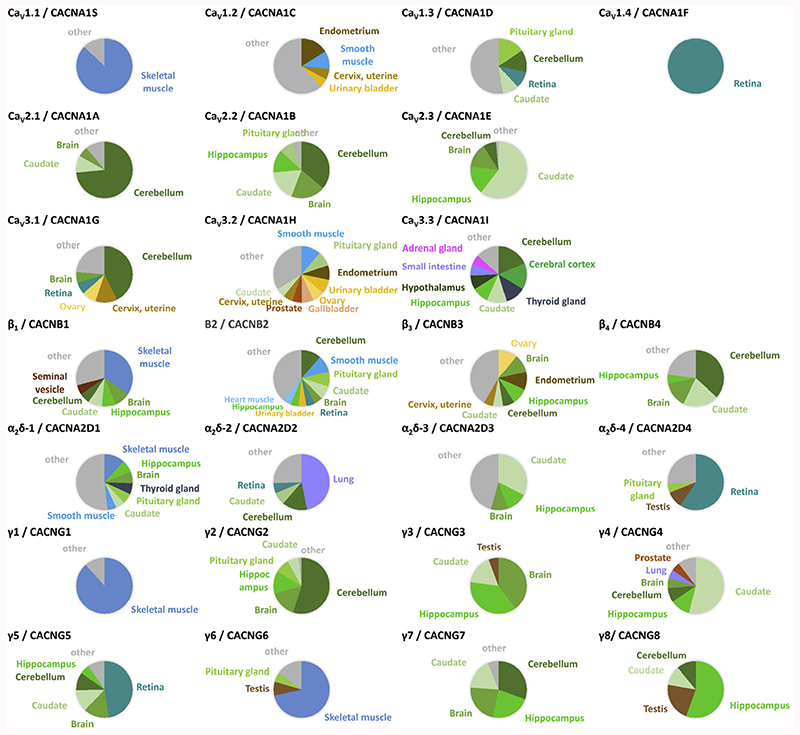

Fig. 3 takes a look at the FANTOM5 expression data from the other angle: Which tissues express a given VGCC gene. It is immediately obvious that CaV1.1 and CaV1.4 have very restricted expression mostly in a single tissue, while CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 were found in a large number of different tissues. All three CaV2 channel isoforms were detected almost exclusively in different parts of the brain, where also β4, α2δ-3 and CaV3.3, to a smaller degree, CaV3.1 were more prominently found. Most of the γ subunits were also mainly localized in the CNS. Other tissue-elevated expression profiles included β1, γ1, γ6 (skeletal muscle), α2δ-2 (lung) and α2δ-4 (retina).

Fig. 3. Distribution of VGCC gene expression in human tissues.

Tissues names are given where the expression exceeds 5% of the total expression in all tissues (except for β2: retina: 4.9%, heart 4.6%). The colour code is the same throughout: brain tissues (green hues), muscle tissues (blue hues), other tissues are indicated by different colours. Less expressed tissues are combined as ‘others’ (grey). Some of the VGCC genes show highly abundant expression (>50% of total): CaV1.1, CaV1.4, CaV2.1, CaV2.3, α2δ-4, γ1, γ2, γ4, γ6, γ8. Others are particularly expressed in several brain areas (together >50% of total): CaV2.2, CaV3.1, ß4, α2δ-3, γ3, γ7. Some are expressed preferentially (>33% of total): ßl· α2δ-2, γ5. The remaining genes showed widespread expression: CaV1.2, CaV1.3, CaV3.2, ß2, ß3, α2δ-1. According to the tissue specificity score (TS) calculation of the Human Protein Atlas (highest expression/2nd highest expression), the tissue-enriched VGCC are (TS score): CaV1.4 (∞), CaV1.1 (22.8), γ1 (21.0), γ6 (9.0), CaV2.1 (7.6) and α2δ-4 (6.2). Note that CaV3.3 and γ6 expression data stems from the GTEx dataset (no FANTOM5 data available on HPA website). FANTOM5 data was retrieved through www.proteinatlas.org on 11.01.2017, GTEx on 12.06.2017).

While FANTOM5 data is largely ignorant of alternative splicing (except 5’ transcription start sites), the HPA data set can also be used to check for the expression of (Ensembl-annotated) splice variants. As an example the two Cav1.1 splice variants, one ‘full-length’ and Cav1.1Δ29 (Ensembl identifiers ENST00000362061, ENST00000367338; see also chapter 4) have a slightly different expression distribution. While in skeletal muscle samples the ‘full-length’ Cav1.1 is ~5-fold more abundant than Cav1.1Δ29, it seems to dominate in esophagus.

Some caveats of these databases have to be kept in mind: on one hand only tissues that have been sampled can be compared, on the other hand tissues can be heterogeneous and therefore have a very different channel set in different parts of the organ. This was obvious from the Cav1.4 expression in the HPA data where it is deemed non-specific because there is no retina sample included. Moreover contributions from retina and retinal pigment epithelium could not be distinguished in the FANTOM 5 dataset because presumably these two tissues were not separated during the sample preparation. In general, both the subunit composition of multimeric channels as well as other interactions can affect the severity of channel dysfunctions. Co-expression in a tissue or even a celltype does not yet prove a functional interaction, but these catalogues can help to identify common candidates for protein interaction networks or even new players, including also non-channel proteins.

3. Tissue specific expression of L-type Ca2+channels

We found a great heterogeneity in the tissue expression of LTCC isoforms. This diversity is expected to impact also on different functional roles of LTCCs in the different tissues. Indeed their physiological importance reaches from excitation-contraction coupling in muscle, to stimulus secretion coupling in sensory and endocrine cells, cardiac pace-making, as well as neuronal firing to learning and memory (Catterall et al., 2005). Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels are both expressed in heart, brain, endocrine cells, and auditory and vestibular receptor cells (for review see (Zamponi et al., 2015)). In some neurons, adrenal chromaffin cells, sinoatrial node and atrial cardiomyocytes those isoforms are often even expressed in the same cell type (Olson et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2007; Dragicevic et al., 2014; Marcantoni et al.; Mangoni et al., 2003). Their differential contribution to cellular processes and their physiological functions can therefore only be distinguished in Cav1.2- and Cav1.3-deficient animals (for reviews on animal models see (Striessnig and Koschak, 2008; Hofmann et al., 2014). Cav1.1 and Cav1.4 α1 transcripts were not found at significant levels in the brain (Figs. 2B and 3; Sinnegger-Brauns et al., 2009). Expression in a limited subset of (brain) neurons or - with respect to Cav1.4 mRNA expression - contamination with pineal gland tissue where Cav1.4 has been reported to be expressed (McRory et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2015a) can’t however be entirely excluded. Of note, immunohistochemical analyses that previously reported expression of Cav1.1 in retinal tissue (Specht et al., 2009; Michalakis et al., 2014; Tummala et al., 2014) were carried out with a Cav1.1-directed antibody that was recently discovered to cross-react with GPR179 (Hasan et al., 2016). Additional western blot and mass spectro-metric analyses of Cav1.1 immunoprecipitated proteins also failed to detect any matching Cav1.1 peptides, however a novel splice variant with exons 1–16 skipped and two novel exons termed 16a and 16b has been found by RNAseq (Hasan et al., 2016).

Being described as an atypical prototypical VGCC Cav1.1 is expressed solely in skeletal muscle where it serves as voltage sensor for excitation-contraction coupling and contributes excitation-coupled Ca2+ entry (for review see (Bannister and Beam, 2013)). In skeletal muscle Cav1.1 is located within the junctional membranes of the t-tubule system where it physically interacts with ryanodine-sensitive release channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum in order to trigger rapid Ca2+ release and mediated muscle contraction. Cav1.4 expression however is primarily restricted to the retina. Cav1.4 immunoreactivity has been first described in the outer and inner plexiform layers of chicken retina (Firth et al., 2001). Its expression at photoreceptor release sites located in close vicinity to the typical horseshoe-shaped ribbon synapses has been confirmed in many studies on rodent and zebrafish retina (Mansergh et al., 2005; Specht et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2013; Knoflach et al., 2013; Michalakis et al., 2014; Regus-Leidig et al., 2014; Jia et al., 2014; An et al., 2015; Grabner et al., 2015). Cav1.4 expression in retinal bipolar cells has also been suggested (Berntson et al., 2003; Busquet et al., 2010; Morgans et al., 2005) but functional assessment of the channel subunit composition is lacking. The LTCC identity of these neurons is therefore still ambiguous. As already mentioned above, Cav1.4 was further detected outside the retina in mouse, including tissue of the immune system and the pineal gland (McRory et al., 2004; Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005; Yu et al., 2015a).

4. L-type Ca2+ channel diversity by alternative splicing and its consequences

As the reader can take from Table 2, literature about the post-transcriptional mechanism of alternative splicing in VGCCs is rapidly emerging as is the information about the functional heterogeneity encoded by those alternatively spliced gene products. Alternative splicing is important in all four α1 isoforms of LTCC. For example one Cav1.1 variant that differs in the length of the IVS3-S4 linker due to skipping of exon 29 (Cav1.1Δ29, see also Table 2) was abundantly expressed in mouse and human myotubes (Tuluc et al., 2009) and has also been reported in mouse spleen (Matza et al., 2016). Of note, muscle weakness in the pathogenesis of human myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) and type 2 (DM2) has been related to the aberrant Cav1.1 splicing and altered gating properties in the resulting Cav1.1Δ29 channels (Tang et al., 2012; Santoro et al.,2014).

A rodent splice variant of Cav1.2 that contained the mutually exclusive exons 21 and 22 (Cav1.2e21+22) resulted in nonconducting Cav1.2 channels. In heterologously transfected HEK-293 cells Cav1.2e21+22 in turn reduced the number of cell surface expressed wild type Cav1.2 channels by enhanced ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation, that consequently also decreased Cav1.2 mediated Ca2+ influx (Hu et al., 2016). This variant was highly expressed in the neonatal heart but no expression in brain was reported. Under stressful conditions also adult mouse and human hearts showed increased abundance indicating that this splice variant may even contribute to heart failure (Hu et al., 2016). Another study showed that in a rat myocardial infarction model the expression of a number of alternatively spliced exons were changed. Upon ligation of a descending artery a novel Cav1.2 9*/delta33 channel (inclusion of exon 9* and deletion of exon 33) was generated in the scar region that exhibited hyperpolarized shifts of the voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation in the heterologous expression system (Liao et al., 2009). Intriguingly, in Cav1.2 the binding site for DHPs - which specifically block LTCCs – is encoded by the exclusive exons 8 and 8a (see also Table 2). Cav1.2 channels containing exon 8 are expressed in smooth muscle and display a 10-fold greater affinity for DHP blockers than exon 8a containing channels which comprise the cardiac form (Welling et al., 1997). However, in human heart tissue samples - taken from heart transplant recipients - a subset of tissues expressed predominantly the exon 8 containing smooth muscle isoform, rather than the cardiac isoform (Welling et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2006). This finding suggested that in affected individuals therapeutic DHP treatment could cause strong unwanted effects in the heart. This is a clear example highlighting that interindividual variability in alternative splicing can severely modulate pharmacological effects through distinct tissue expression and therefore cause harm to patients.

Furthermore, also drug action on Cav1.3 channels depends on the effects of alternative splicing. An intramolecular interaction between a distal and a proximal regulatory domain – forming an intrinsic C-terminal modulatory mechanism, short CTM - within the Cav1.3 C-terminus is a major determinant of their voltage- and Ca2+-dependent gating kinetics (Striessnig, 2007). Splicing in the C-terminus of Cav1.3 α1 subunits gives rise to fundamentally different channels with either ‘long’ or ‘short’ C-termini. Thereby removal of the CTM domains by alternative splicing generates the ‘short’ Cav1.3 (Cav1.342A, Cav1.343S) channels. These splice isoforms activated at a more negative voltage range and exhibited different voltage- and Ca2+-dependent inactivation properties of these channels (Bock et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2012). At this point it is important to know that the action of DHPs depends on the inactivated channel state (Bean et al., 1986; Hamilton et al., 1987; Koschak et al., 2001; Berjukow and Hering, 2001) such that DHPs possess a higher affinity for the inactivated channel conformation. The amount of channel block is therefore expected to change with the availability of inactivated channel states. Of note, the expression of both short and long variants showed a certain tissue specificity. The long variant seemed to predominate in the heart whereas expression of both variants were about equally abundant in the brain (Bock et al., 2011). Together, this suggests that DHP drugs might act differently on Cav1.3 channel variants expressed in different tissues to fine-tune channel function (Huang et al., 2014; Ortner et al., 2017). Also in Cav1.4, the most abundantly expressed LTCC in the retina, alternative splicing occurs. In a transcript scanning approach of human retina samples, 19 Cav1.4 splice variants were identified (Tan et al., 2012). One of those also resulted in a truncation of the channels’ C-terminus (CaV1.4 ex43*). Similar to Cav1.3 channels, such structural change is also expected to severely affect the voltage- and Ca2+-dependent gating properties of Cav1.4 channels (Singh et al., 2006; Wahl-Schott et al., 2006). Indeed, the loss of CTM in the splice variant CaV1.4 ex43* resulted in robust Ca2+-dependent inactivation and a hyperpolarized activation range (Haeseleer et al., 2016). Such gating changes might be even pathological for visual signaling (Singh et al., 2006; Wahl- Schott et al., 2006). Though a recent heterologous expression study provided evidence that coexpression of CaBP4 - a member of a family of Ca2+-binding proteins (CaBPs) related to CaM and expressed in retinal photoreceptors (Haeseleer et al., 2004) – could at least in part compensate for the expected Cav1.4 gating changes by binding to the remaining C-terminal domain of the CaV1.4 C-terminus (Haeseleer et al., 2016). To which extent these naturally occurring alternative splice variants indeed add to the properties of native Cav1.4 currents (von Gersdorff and Matthews, 1996; Rabl and Thoreson, 2002) or whether the abundance of particular splice variants is changed under pathophysiological conditions - as seen for all other LTCCs (Table 2) - is not yet resolved. Details on these functionally different Cav1.4 splice variants in other tissues (lymphocytes or pineal gland) are yet to be elucidated.

5. Manifestation of Cav1.4-related channelopathies and treatment challenges

Tissue expression of a certain protein often correlates with histological and functional features seen in animal models and humans as well as the clinical features in case of a dysfunctional protein. Among the LTCC family Cav1.4 is one of the finest examples.

The role of Cav1.4 is well supported by the fact that mutations in the CACNA1F gene can cause several forms of human retinal diseases (OMIM #300071, #300476, #300600, for review see (Zeitz et al., 2015)). The majority of Cav1.4 mutations were identified in congenital stationary night blindness type 2 (CSNB2) patients who are presenting with typical symptoms like low visual acuity, myopia, nystagmus, strabismus, photophobia and variable levels of night blindness (Bech-Hansen et al., 1998a,b). CSNB2 mainly involves males due to the X-linked nature of the disease but recent reports substantiated that heterozygote females can also be affected (Hope et al., 2005; Michalakis et al., 2014). Both loss of channel function and increased channel activity can lead to alterations in photoreceptor synapse formation. This has been demonstrated in Cav1.4 deficient mice (Cav1.4–/–(Morgans et al., 2001; Mansergh et al., 2005; Raven et al., 2008; Zabouri and Haverkamp, 2013; Specht et al., 2009)) and also in Cav1.4 mutant mice. The latter contain a point mutation at position Ile756Thr (corresponding to Ile745Thr in the patients) that induced enhanced channel activity obvious from a strong hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage-dependence of activation and slowing of the inactivation properties (Cav1.4-IT; (Hemara-Wahanui et al., 2005)). A large body of work done by many labs highlighted that Cav1.4 channels are central for the proper formation and maturation of photoreceptor synapses (Morgans et al., 2001; Mansergh et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006; Bayley and Morgans, 2007; Raven et al., 2008; Zabouri and Haverkamp, 2013; Specht et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2013; Regus- Leidig et al., 2014; Michalakis et al., 2014).

Functional data from CSNB2 patients still implied an incomplete defect of the ON and OFF bipolar cells or their synapses in the rod and cone visual pathways (Miyake et al., 1986; Miyake, 2002). Indeed signal transmission was not completely blocked but some reduced activity remained in Cav1.4 mutant retinas (Chang et al., 2006; Knoflach et al., 2015). In the Cav1.4-IT mouse model the left shift in the voltage-dependence of channel activation was hypothesized to reduce the dynamic range of photoreceptor activity. In line with this hypothesis only a fraction of Cav1.4-IT ganglion cells responded to light stimulation in multielectrode array recordings from whole-mounted retinas, and spatial responses as well as changes in their contrast sensitivity profile were decreased in these mutants (Knoflach et al., 2015). Of note, strongly reduced visual acuity in fact turned out to be a major complaint in CSNB2 patients (Bijveld et al., 2013) and patients carrying the respective Cav1.4 mutation also showed pronounced vision loss (up to 80% (Hope et al., 2005)).

When we consider treatment of retinal Cav1.4-related channe-lopathies we face several challenges. The very restricted expression of Cav1.4 channels in retinal tissue should be a clear advantage for Cav1.4 targeted therapy. But still, in systemic pharmacotherapy due to the expression of Cav1.4 in immune cells or pineal gland tissue (see above) the potential effects on the immune system or the sleep/wake cycle would have to be controlled for, even though no obvious deficits in circadian rhythm or immune system have been documented so far in CSNB2 patients. The main problem however lies in the specificity of available drugs. Currently all LTCC blockers that are in clinical use, as for example the DHP nifedipine or other DHPs (Striessnig et al., 2015), are considered non-selective because Cav1.2, Cav1.3 and Cav1.4 channels only slightly differ in their DHP sensitivity (Koschak et al., 2001; Xu and Lipscombe, 2001; Koschak et al., 2003). Due to their high binding affinity to Cav1.2 channels DHPs mainly have cardiovascular effects (Cav1.2 expression in cardiovascular tissue, see Figs. 2C and 3; (Moosmang et al., 2003;Zhang et al., 2006)). For this reason, DHPs are not applicable in CSNB2 patients – and also for treatment of other CNS disorders – considering the severe side effects of the necessary therapeutic doses (for review see (Zamponi et al., 2015)). When considering restoration of channel function either by pharmacological chaperoning in the retina (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01233609) or gene-based retinal therapies.

(Sengillo et al., 2017), treatments likely would have to start early during retinal development because of the crucial role of Cav1.4 for proper synapse formation already mentioned above.

6. Gene therapy of Cav1.4 channelopathies

Treatment e.g. of skeletal muscle by gene therapy is considered in humans (for review (Saada et al., 2016; Sommese et al., 2017)) and has been demonstrated in animal models (Gruntman et al., 2013; Qiao et al., 2011) (Wang et al., 2014) even without the use of viral vectors (Lu et al., 2003), though the necessary systemic approach to treat all muscles in the body bears certain risks given by the widespread distribution of muscle tissues. The focal expression of Cav1.4 in the eye on the other hand provides a number of advantages which are briefly outlined in the following.

The eye is not only easily accessible but it is also a small sized and confined organ. Thus, low amounts of viral vectors are sufficient and there is little risk of a systemic spread of the vector. For this reason and for reasons explained below, the eye has been targeted in gene therapy (Sengillo et al., 2017; Scholl et al., 2016). In particular, intravitreal injections of vectors are easy to perform and constitute a routine procedure in eye hospitals without the need for inpatient admission. Intravitreal injections can reach large areas of the retina (Da Costa et al., 2016), a clear advantage over subretinal delivery, where a needle has to penetrate the retina to inject vectors between retina and choroid. Of note, adeno-associated viruses (AAV) that effectively target photoreceptors even from intravitreal injections (e.g. AAV.7m8) have been developed and applied successfully in gene therapy in mice (Dalkara et al., 2013). Alternatively, the functionality of selective promotors for expression in rods (Koch et al., 2012) or (S-)cones (Michalakis et al., 2010) without cell-type specific tropism has been demonstrated. Targeting other cell types is also feasible due to the comparatively well-known cell types in the retina and the knowledge about cell-type specific genes (Siegert et al., 2012) and promoters (Ivanova et al., 2010). In the case of Cav1.4 it might be necessary to treat not only photoreceptors but also bipolar cells that express Cav1.4 (Berntson et al., 2003), so a mixed approach of different vectors/tropisms or promotors could be required. Targeting Cav1.4 might still be challenging due to the size of the CACNA1F gene (OMIM 300100) and the limited packaging capacity of AAVs. However, split-intein-mediated protein transsplicing methods have already been used successfully to manipulate other LTCCs (Subramanyam et al., 2013).

Viral vector-based gene therapy benefits from the immune-privileged status and the specific location of the retina in the eye. The blood-retina barrier provides an advantage in the protection of treated cells from the patients’ immune responses by limiting potential inflammatory reactions (Bennett, 2003). It has however been observed that intravitreal injections can trigger an immune response not observed by subretinal injections (Li et al., 2008). Still, the enclosed structure of the eye in conjunction with the blood-retina barrier provides a spatial restriction of gene therapeutic treatments almost unrivalled by other organs. These features are relevant for all genetic interventions, in particular in CRISPR/Cas9 applications (Hung et al., 2016; Latella et al., 2016; Bakondi et al., 2016; Yanik et al., 2017; Ruan et al., 2017) where off-target effects might not be fully excluded (Fu et al., 2014). Together, the eye/retina provides a high level of containment with limited immune response, making applications comparatively safe. Indeed several clinical trials of gene therapy for eye diseases in patients have been undertaken in recent years (Bainbridge et al., 2008; Maguire et al., 2008; Cideciyan et al., 2008). Cav1.4 mutations would therefore be amenable for gene therapeutic treatments in the foreseeable future.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 674901 to AK, and was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF P-26881-B23, P-29359 to AK), the Center of Molecular Biosciences Innsbruck and the University of Innsbruck.

References

- An J, Zhang L, Jiao B, Lu F, Xia F, Yu Z, Zhang Z. Cacna1f gene decreased contractility of skeletal muscle in rat model with congenital stationary night blindness. Gene. 2015;562:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badou A, Jha MK, Matza D, Flavell RA. Emerging roles of L-type voltagegated and other calcium channels in T lymphocytes. Front Immunol. 2013;4:243. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, Robbie S, Henderson R, Balaggan K, Viswanathan A, Holder GE, Stockman A, Tyler N, Petersen-Jones S, et al. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2231–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakondi B, Lv W, Lu B, Jones MK, Tsai Y, Kim KJ, Levy R, Akhtar AA, Breunig JJ, Svendsen CN, Wang S. In Vivo CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing Corrects retinal dystrophy in the S334ter-3 rat model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther. 2016;24:556–563. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister RA, Beam KG. Ca(V)1.1: the atypical prototypical voltage-gated Ca(2)(÷) channel. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:1587–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley PR, Morgans CW. Rod bipolar cells and horizontal cells form displaced synaptic contacts with rods in the outer nuclear layer of the nob2 retina. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:286–298. doi: 10.1002/cne.21188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP, Sturek M, Puga A, Hermsmeyer K. Calcium channels in muscle cells isolated from rat mesenteric arteries: modulation by dihydropyridine drugs. Circ Res. 1986;59:229–235. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech-Hansen NT, Boycott KM, Gratton KJ, Ross DA, Field LL, Pearce WG. Localization of a gene for incomplete X-linked congenital stationary night blindness to the interval between DXS6849 and DXS8023 in Xp11.23. Hum Genet. 1998a;103:124–130. doi: 10.1007/s004390050794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech-Hansen NT, Naylor MJ, Maybaum TA, Pearce WG, Koop B, Fishman GA, Mets M, Musarella MA, Boycott KM. Loss-of-function mutations in a calcium-channel alpha1-subunit gene in Xp11.23 cause incomplete X-linked congenital stationary night blindness. Nat Genet. 1998b;19:264–26. doi: 10.1038/947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J. Immune response following intraocular delivery of recombinant viral vectors. Gene Ther. 2003;10:977–982. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berjukow S, Hering S. Voltage-dependent acceleration of Ca(v)1.2 channel current decay by (+)- and (-)-isradipine. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:959–966. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson A, Taylor WR, Morgans CW. Molecular identity, synaptic localization, and physiology of calcium channels in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:146–151. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijveld MM, Florijn RJ, Bergen AA, van den Born LI, Kamermans M, Prick L, Riemslag FC, van Schooneveld MJ, Kappers AM, van Genderen MM. Genotype and phenotype of 101 Dutch patients with congenital stationary night blindness. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2072–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock G, Gebhart M, Scharinger A, Jangsangthong W, Busquet P, Poggiani C, Sartori S, Mangoni ME, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Herzig S, Striessnig J, et al. Functional properties of a newly identified C-terminal splice variant of Cav1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42736–42748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busquet P, Nguyen NK, Schmid E, Tanimoto N, Seeliger MW, Ben-Yosef T, Mizuno F, Akopian A, Striessnig J, Singewald N. CaV1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels modulate depression-like behaviour in mice independent of deaf phenotype. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:499–513. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral MD, Paulet PE, Robert V, Gomes B, Renoud ML, Savignac M, Leclerc C, Moreau M, Lair D, Langelot M, Magnan A, et al. Knocking down Cav1 calcium channels implicated in Th2 cell activation prevents experimental asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1310–1317. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1166OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a003947. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Perez-Reyes E, Snutch TP, Striessnig J. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:411–425. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Guzman JN, Ilijic E, Mercer JN, Rick C, Tkatch T, Meredith GE, Surmeier DJ. ‘Rejuvenation’ protects neurons in mouse models ofParkinson’s disease. Nature. 2007;447:1081–1086. doi: 10.1038/nature05865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Heckenlively JR, Bayley PR, Brecha NC, Davisson MT, Hawes NL, Hirano AA, Hurd RE, Ikeda A, Johnson BA, McCall MA, et al. The nob2 mouse, a null mutation in Cacna1f: anatomical and functional abnormalities in the outer retina and their consequences on ganglion cell visual responses. Vis Neurosci. 2006;23:11–24. doi: 10.1017/S095252380623102X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Aleman TS, Boye SL, Schwartz SB, Kaushal S, Roman AJ, Pang JJ, Sumaroka A, Windsor EA, Wilson JM, Flotte TR, et al. Human gene therapy for RPE65 isomerase deficiency activates the retinoid cycle of vision but with slow rod kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15112–15117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa R, Roger C, Segelken J, Barben M, Grimm C, Neidhardt J. A novel method combining vitreous aspiration and intravitreal AAV2/8 injection results in retina-wide transduction in adult mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:5326–5334. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkara D, Byrne LC, Klimczak RR, Visel M, Yin L, Merigan WH, Flannery JG, Schaffer DV. In vivo-directed evolution of a new adeno-associated virus for therapeutic outer retinal gene delivery from the vitreous. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:189ra176. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport B, Li Y, Heizer JW, Schmitz C, Perraud AL. Signature channels of excitability no more: L-type channels in immune cells. Front Immunol. 2015;6:375. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragicevic E, Poetschke C, Duda J, Schlaudraff F, Lammel S, Schiemann J, Fauler M, Hetzel A, Watanabe M, Lujan R, Malenka RC, et al. Cav1.3 channels control D2-autoreceptor responses via NCS-1 in substantia nigra dopamine neurons. Brain. 2014;137:2287–2302. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden E, Geva-Zatorsky N, Issaeva I, Cohen A, Dekel E, Danon T, Cohen L, Mayo A, Alon U. Proteome half-life dynamics in living human cells. Science. 2011;331:764–768. doi: 10.1126/science.1199784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez JA, McGahon MK, McGeown JG, Curtis TM. CaV3.1 T-Type Ca2+ channels contribute to myogenic signaling in rat retinal arterioles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:5125–5132. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth SI, Morgan IG, Boelen MK, Morgans CW. Localization of voltagesensitive L-type calcium channels in the chicken retina. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;29:183–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2001.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Sander JD, Reyon D, Cascio VM, Joung JK. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:279–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner CP, Gandini MA, Rehak R, Le Y, Zamponi GW, Schmitz F. RIM1/ 2-Mediated facilitation of Cav1.4 channel opening is required for Ca2+-Stimulated release in mouse rod photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13133–13147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0658-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruntman AM, Bish LT, Mueller C, Sweeney HL, Flotte TR, Gao G. Gene transfer in skeletal and cardiac muscle using recombinant adeno-associated virus. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc14d03s28. Chapter 14, Unit 14D.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Imanishi Y, Maeda T, Possin DE, Maeda A, Lee A, Rieke F, Palczewski K. Essential role of Ca2+-binding protein 4, a Cav1.4 channel regulator, in photoreceptor synaptic function. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1079–1087. doi: 10.1038/nn1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Williams B, Lee A. Characterization of C-terminal splice variants of Cav1.4 Ca2+ channels in human retina. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:15663–15673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.731737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SL, Yatani A, Brush K, Schwartz A, Brown AM. A comparison between the binding and electrophysiological effects of dihydropyridines on cardiac membranes. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;31:221–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz OF, Brett SE, Zechariah A, Romero M, Puglisi JL, Wilson SM, Welsh DG. Genetic ablation of CaV3.2 channels enhances the arterial myogenic response by modulating the RyR-BKCa axis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015a;35:1843–1851. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz OF, Visser F, Brett SE, Goldman D, Zechariah A, Hashad AM, Menon BK, Watson T, Starreveld Y, Welsh DG. CaV1.2/CaV3.x channels mediate divergent vasomotor responses in human cerebral arteries. J Gen Physiol. 2015b;145:405–418. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201511361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan N, Ray TA, Gregg RG. CACNA1S expression in mouse retina: novel isoforms and antibody cross-reactivity with GPR179. Vis Neurosci. 2016;33:E009. doi: 10.1017/S0952523816000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemara-Wahanui A, Berjukow S, Hope CI, Dearden PK, Wu SB, Wilson-Wheeler J, Sharp DM, Lundon-Treweek P, Clover GM, Hoda JC, Striessnig J, et al. A CAC-NA1F mutation identified in an X-linked retinal disorder shifts the voltage dependence of Cav1.4 channel activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7553–7558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501907102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Kahl S, Wegener JW. L-type CaV1.2 calcium channels: from in vitro findings to in vivo function. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:303–326. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope CI, Sharp DM, Hemara-Wahanui A, Sissingh JI, Lundon P, Mitchell EA, Maw MA, Clover GM. Clinical manifestations of a unique X-linked retinal disorder in a large New Zealand family with a novel mutation in CAC-NA1F, the gene responsible for CSNB2. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33:129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Wang JW, Yu D, Soon JL, de Kleijn DP, Foo R, Liao P, Colecraft HM, Soong TW. Aberrant splicing promotes proteasomal degradation of L-type CaV1.2 calcium channels by Competitive binding for CaVbeta subunits in cardiac hypertrophy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35247. doi: 10.1038/srep35247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Ng CY, Yu D, Zhai J, Lam Y, Soong TW. Modest CaV1.342-selective inhibition by compound 8 is beta-subunit dependent. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4481. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung SS, Chrysostomou V, Li F, Lim JK, Wang JH, Powell JE, Tu L, Daniszewski M, Lo C, Wong RC, Crowston JG, et al. AAV-mediated CRISPR/Cas gene editing of retinal cells in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:3470–3476. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova E, Hwang GS, Pan ZH. Characterization of transgenic mouse lines expressing Cre recombinase in the retina. Neuroscience. 2010;165:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha A, Singh AK, Weissgerber P, Freichel M, Flockerzi V, Flavell RA, Jha MK. Essential roles for Cavbeta2 and Cav1 channels in thymocyte development and T cell homeostasis. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra103. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aac7538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S, Muto A, Orisme W, Henson HE, Parupalli C, Ju B, Baier H, Taylor MR. Zebrafish Cacna1fa is required for cone photoreceptor function and synaptic ribbon formation. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:2981–2994. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkat-Rott K, Lerche H, Lehmann-Horn F. Skeletal muscle channelo-pathies. J Neurol. 2002;249:1493–1502. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoflach D, Kerov V, Sartori SB, Obermair GJ, Schmuckermair C, Liu X, Sothilingam V, Garrido MG, Baker SA, Glosmann M, Schicker K, et al. Cav1.4 IT mouse as model for vision impairment in human congenital stationary night blindness type 2. Channels (Austin) 2013;7:503–513. doi: 10.4161/chan.26368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoflach D, Schicker K, Glosmann M, Koschak A. Gain-of-function nature of Cav1.4 L-type calcium channels alters firing properties of mouse retinal ganglion cells. Channels (Austin) 2015;9:298–306. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2015.1078040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch S, Sothilingam V, Garcia Garrido M, Tanimoto N, Becirovic E, Koch F, Seide C, Beck SC, Seeliger MW, Biel M, Muhlfriedel R, et al. Gene therapy restores vision and delays degeneration in the CNGB1(-/-) mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4486–4496. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschak A, Reimer D, Huber I, Grabner M, Glossmann H, Engel J, Striessnig J. α1D(Cav1.3)subunits can form L-type Ca2+channels activating at negative voltages. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22100–22106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschak A, Reimer D, Walter D, Hoda JC, Heinzle T, Grabner M, Striessnig J. Cav1.4α1 subunits can form slowly inactivating dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type Ca2+channels lacking Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6041–6049. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-06041.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotturi MF, Jefferies WA. Molecular characterization of L-type calcium channel splice variants expressed in human T lymphocytes. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:1461–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo IY, Howitt L, Sandow SL, McFarlane A, Hansen PB, Hill CE. Role of T-type channels in vasomotor function: team player or chameleon? Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:767–779. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latella MC, Di Salvo MT, Cocchiarella F, Benati D, Grisendi G, Comitato A, Marigo V, Recchia A. In vivo editing of the human mutant rhodopsin gene by electroporation of plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 in the mouse retina. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e389. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Miller R, Han PY, Pang J, Dinculescu A, Chiodo V, Hauswirth WW. Intraocular route of AAV2 vector administration defines humoral immune response and therapeutic potential. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1760–1769. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao P, Li G, Yu de J, Yong TF, Wang JJ, Wang J, Soong TW. Molecular alteration of Ca(v)1.2 calcium channel in chronic myocardial infarction. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:701–711. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kerov V, Haeseleer F, Majumder A, Artemyev N, Baker SA, Lee A. Dysregulation of Ca(v)1.4 channels disrupts the maturation of photoreceptor synaptic ribbons in congenital stationary night blindness type 2. Channels (Austin) 2013;7:514–523. doi: 10.4161/chan.26376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizio M, Harshbarger J, Shimoji H, Severin J, Kasukawa T, Sahin S, Abugessaisa I, Fukuda S, Hori F, Ishikawa-Kato S, Mungall CJ, et al. Gateways to the FANTOM5 promoter level mammalian expression atlas. Genome Biol. 2015;16:22. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QL, Bou-Gharios G, Partridge TA. Non-viral gene delivery in skeletal muscle: a protein factory. Gene Ther. 2003;10:131–142. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, Pugh EN, Jr, Mingozzi F, Bennicelli J, Banfi S, Marshall KA, Testa F, Surace EM, et al. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2240–2248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni ME, Couette B, Bourinet E, Platzer J, Reimer D, Striessnig J, Nargeot J. Functional role of L-type Cav1.3 Ca2+channels in cardiac pacemaker activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5543–5548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0935295100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh F, Orton NC, Vessey JP, Lalonde MR, Stell WK, Tremblay F, Barnes S, Rancourt DE, Bech-Hansen NT. Mutation of the calcium channel gene Cacna1f disrupts calcium signaling, synaptic transmission and cellular organization in mouse retina. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3035–3046. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcantoni A, Vandael DH, Mahapatra S, Carabelli V, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Striessnig J, Carbone E. Loss of Cav1.3 channels reveals the critical role of L-type and BK channel coupling in pacemaking mouse adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 30:491–504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4961-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matza D, Badou A, Klemic KG, Stein J, Govindarajulu U, Nadler MJ, Kinet JP, Peled A, Shapira OM, Kaczmarek LK, Flavell RA. T cell receptor mediated calcium entry requires alternatively spliced Cav1.1 channels. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRory JE, Hamid J, Doering CJ, Garcia E, Parker R, Hamming K, Chen L, Hildebrand M, Beedle AM, Feldcamp L, Zamponi GW, et al. The CACNA1F gene encodes an L-type calcium channel with unique biophysical properties and tissue distribution. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1707–1718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4846-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalakis S, Muhlfriedel R, Tanimoto N, Krishnamoorthy V, Koch S, Fischer MD, Becirovic E, Bai L, Huber G, Beck SC, Fahl E, et al. Restoration of cone vision in the CNGA3-/-mouse model of congenital complete lack of cone photoreceptor function. Mol Ther. 2010;18:2057–2063. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalakis S, Shaltiel L, Sothilingam V, Koch S, Schludi V, Krause S, Zeitz C, Audo I, Lancelot ME, Hamel C, Meunier I, et al. Mosaic synaptopathy and functional defects in Cav1.4 heterozygous mice and human carriers of CSNB2. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1538–1550. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y. Establishment of the concept of new clinical entities-complete and incomplete form of congenital stationary night blindness. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2002;106:737–755. discussion 756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y, Yagasaki K, Horiguchi M, Kawase Y, Kanda T. Congenital stationary night blindness with negative electroretinogram. A new classification. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1013–1020. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050190071042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Schulla V, Welling A, Feil R, Feil S, Wegener JW, Hofmann F, Klugbauer N. Dominant role of smooth muscle L-type calcium channel Cav1.2 for blood pressure regulation. EMBO J. 2003;22:6027–6034. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgans CW, Bayley PR, Oesch NW, Ren G, Akileswaran L, Taylor WR. Photoreceptor calcium channels: insight from night blindness. Vis Neurosci. 2005;22:561–568. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805225038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgans CW, Gaughwin P, Maleszka R. Expression of the alpha1F calcium channel subunit by photoreceptors in the rat retina. Mol Vis. 2001;7:202–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C, Mas Gomez N, Ruth P, Strauss O. CaV1.3 L-type channels, maxiK Ca(2+)-dependent K(+) channels and bestrophin-1 regulate rhythmic photoreceptor outer segment phagocytosis by retinal pigment epithelial cells. Cell Signal. 2014;26:968–978. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson PA, Tkatch T, Hernandez-Lopez S, Ulrich S, Ilijic E, Mugnaini E, Zhang H, Bezprozvanny I, Surmeier DJ. G-protein-coupled receptor modulation of striatal Cav1.3 L-type Ca2+channels is dependent on a Shankbinding domain. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1050–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3327-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omilusik K, Priatel JJ, Chen X, Wang YT, Xu H, Choi KB, Gopaul R, McIntyre-Smith A, Teh HS, Tan R, Bech-Hansen NT, et al. The Ca(v)1.4 calcium channel is a critical regulator of T cell receptor signaling and naive T cell homeostasis. Immunity. 2011;35:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortner NJ, Bock G, Dougalis A, Kharitonova M, Duda J, Hess S, Tuluc P, Pomberger T, Stefanova N, Pitterl F, Ciossek T, et al. Lower affinity of isradipine for L-type Ca2+ channels during substantia nigra dopamine neuron-like activity: implications for neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2017 Jun 7; doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2946-16.2017. pii: 2946-16.[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao C, Koo T, Li J, Xiao X, Dickson JG. Gene therapy in skeletal muscle mediated by adeno-associated virus vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;807:119–140. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-370-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabl K, Thoreson WB. Calcium-dependent inactivation and depletion of synaptic cleft calcium ions combine to regulate rod calcium currents under physiological conditions. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:2070–2077. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven MA, Orton NC, Nassar H, Williams GA, Stell WK, Jacobs GH, Bech-Hansen NT, Reese BE. Early afferent signaling in the outer plexiform layer regulates development of horizontal cell morphology. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:745–758. doi: 10.1002/cne.21526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regus-Leidig H, Atorf J, Feigenspan A, Kremers J, Maw MA, Brandstatter JH. Photoreceptor degeneration in two mouse models for congenital stationary night blindness type 2. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert V, Triffaux E, Paulet PE, Guery JC, Pelletier L, Savignac M. Protein kinase C-dependent activation of CaV1.2 channels selectively controls human TH2-lymphocyte functions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan GX, Barry E, Yu D, Lukason M, Cheng SH, Scaria A. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated genome editing as a therapeutic approach for Leber congenital amaurosis 10. Mol Ther. 2017;25:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saada YB, Dib C, Lipinski M, Vassetzky YS. Genome- and cell-based strategies in therapy of muscular dystrophies. Biochem (Mosc) 2016;81:678–690. doi: 10.1134/S000629791607004X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro M, Piacentini R, Masciullo M, Bianchi ML, Modoni A, Podda MV, Ricci E, Silvestri G, Grassi C. Alternative splicing alterations of Ca2+ handling genes are associated with Ca2+ signal dysregulation in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) and type 2 (DM2) myotubes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2014;40:464–476. doi: 10.1111/nan.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlick B, Flucher BE, Obermair GJ. Voltage-activated calcium channel expression profiles in mouse brain and cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2010;167:786–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl HP, Strauss RW, Singh MS, Dalkara D, Roska B, Picaud S, Sahel JA. Emerging therapies for inherited retinal degeneration. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:368rv366. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengillo JD, Justus S, Cabral T, Tsang SH. Correction of monogenic and common retinal disorders with gene therapy. Genes (Basel) 2017;8 doi: 10.3390/genes8020053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert S, Cabuy E, Scherf BG, Kohler H, Panda S, Le YZ, Fehling HJ, Gaidatzis D, Stadler MB, Roska B. Transcriptional code and disease map for adult retinal cell types. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(487-495):S481–S482. doi: 10.1038/nn.3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Gebhart M, Fritsch R, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Poggiani C, Hoda JC, Engel J, Romanin C, Striessnig J, Koschak A. Modulation of voltage- and Ca2+-dependent gating of CaV1.3 L-type calcium channels by alternative splicing of a C-terminal regulatory domain. J Biol Chem. 2008 Jul 25;283(30):20733–20744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802254200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Hamedinger D, Hoda JC, Gebhart M, Koschak A, Romanin C, Striessnig J. C-terminal modulator controls Ca2+-dependent gating of Cav1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1108–1116. doi: 10.1038/nn1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Huber IG, Koschak A, Wild C, Obermair GJ, Einzinger U, Hoda JC, Sartori SB, Striessnig J. Expression and 1,4-dihydropyridine-binding properties of brain L-type calcium channel isoforms. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:407–414. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommese L, Zullo A, Schiano C, Mancini FP, Napoli C. Possible muscle repair in the human cardiovascular system. Stem Cell Rev. 2017 Apr;13(2):170–191. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9711-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, Davenport AP, McGrath JC, Peters JA, Spedding M, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1054–D1068. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]