Abstract

Metabolic programming controls immune cell lineages and functions, but little is known about γδ T cell metabolism. Here, we found that γδ T cell subsets making either interferon-γ (IFN-γ) or interleukin-17 (IL-17) have intrinsically distinct metabolic requirements. Whereas IFN-γ+ γδ T cells were almost exclusively dependent on glycolysis, IL-17+ γδ T cells strongly engaged oxidative metabolism, with increased mitochondrial mass and activity. These distinct metabolic signatures were surprisingly imprinted early during thymic development, and were stably maintained in the periphery and within tumors. Moreover, pro-tumoral IL-17+ γδ T cells selectively showed high lipid uptake and intracellular lipid storage, and were expanded in obesity, and in tumors of obese mice. Conversely, glucose supplementation enhanced the anti-tumor functions of IFN-γ+ γδ T cells and reduced tumor growth upon adoptive transfer. These findings have important implications for the differentiation of effector γδ T cells and their manipulation in cancer immunotherapy.

Introduction

T cells engage specific metabolic pathways to support their differentiation, proliferation and function1,2. Whereas naive αβ T cells oxidize glucose-derived pyruvate via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) or fatty acid oxidation (FAO) to generate ATP, most effector αβ T cells engage in aerobic glycolysis (“Warburg effect”), i.e. the conversion of glucose to lactate, to strengthen cell growth and proliferation3. On the other hand, while aerobic glycolysis is required for optimal αβ T cell effector function4,5, tumor cells heavily consume glucose in the tumor microenvironment (TME), which has a dramatic impact on cytokine production by T cells and hampers tumor immunity5,6. There is therefore great interest in understanding how metabolism-based interventions could inhibit tumor metabolism while promoting effective anti-tumor immunity for improved immunotherapeutic outcomes7.

γδ T cells represent a promising immune population for next-generation cancer immunotherapies8,9. Since they are not MHC-restricted nor dependent on neoantigen recognition, γδ T cells constitute a complementary layer of anti-tumor immunity to their αβ T cell counterparts10. In fact, many properties of γδ T cells, including sensing of “stress-inducible” changes and very rapid effector responses, align best with innate immunity, or “lymphoid stress-surveillance”11, although in some instances they display adaptive-like behaviour and profound shaping of their T cell receptor (TCR) repertoires12,13.

The effector functions of murine γδ T cells are dominated by the production of two key cytokines, interleukin 17A (IL-17) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). Beyond contributions to immune responses against pathogens, the provision of these two cytokines by γδ T cells is important in many (patho)physiological contexts, such as maintenance of tissue homeostasis14,15, autoimmunity16 and cancer8. IL-17 and IFN-γ are mostly produced by distinct γδ T cell subsets that, unlike their CD4+ T cell counterparts, typically acquire their effector functions during thymic development17,18. Thymic γδ T cell progenitors, driven by signals including those stemming from the T cell receptor (TCR), split into a CD27+ (and CD45RB+) branch that makes IFN-γ but not IL-17; and a CD27– (and CD44hi) pathway that selectively expresses IL-1717–21.

The IFN-γ/IL-17 dichotomy between effector γδ T cell subsets is particularly relevant in cancer, since IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells (γδIFN) are associated with tumor surveillance and regression, whereas IL-17-secreting γδ T cells (γδ17) promote primary tumor growth and metastasis, both in mice and in humans8,22. However, the molecular cues that regulate the balance between such antagonistic γδ T cell subsets in the TME remain poorly characterized. Given the strong impact of metabolic resources on anti-tumor αβ T cell responses, here we have investigated the metabolic profiles of γδ T cell subsets and how they might impact on their activities in the TME. We find here that γδIFN T cells are almost exclusively glycolytic, whereas γδ17 T cells are strongly dependent on mitochondrial and lipid oxidative metabolism. This metabolic dichotomy is established in the thymus during γδ T cell development, and maintained in peripheral lymphoid organs and within tumors in various experimental models of cancer. We further show that the provision of glucose or lipids has major impact on the relative expansion and function of the two γδ T cell subsets, and this can be used to enhance anti-tumor γδ T cell responses.

Results

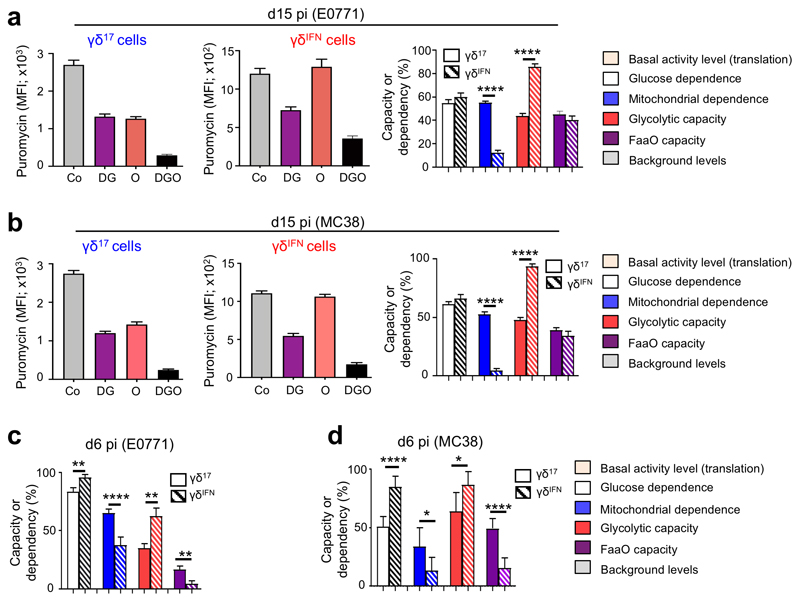

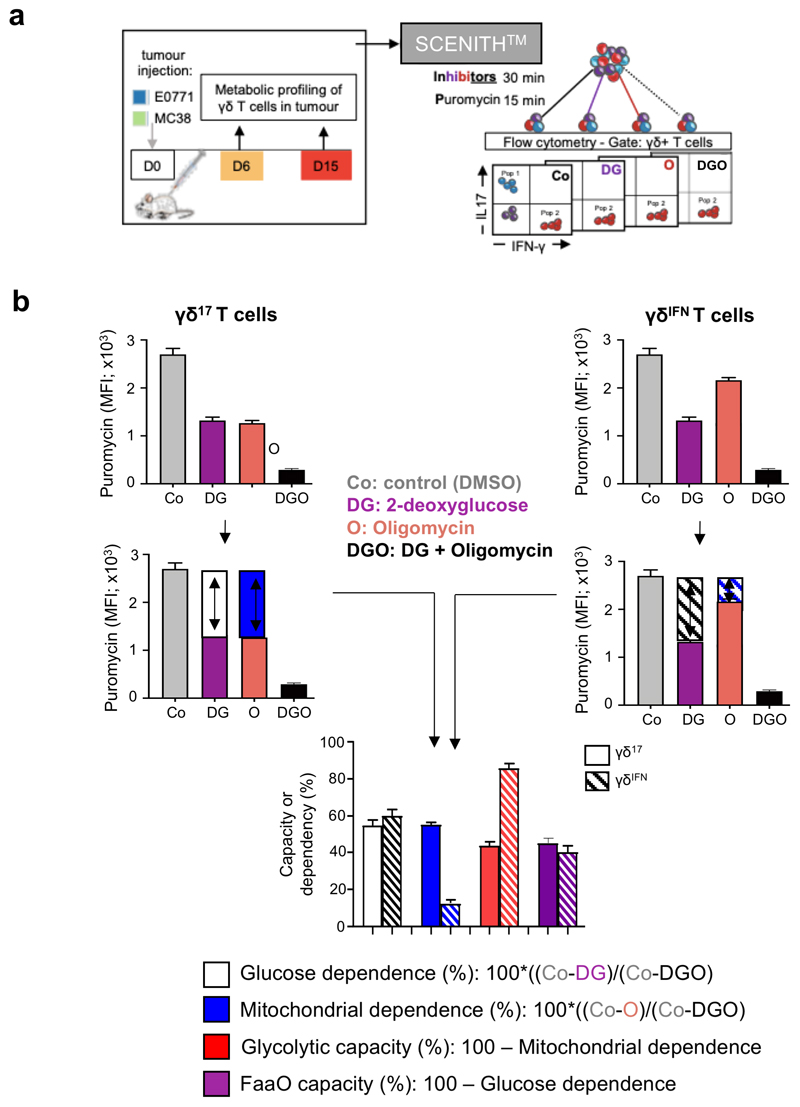

Intra-tumoral γδ T cell subsets display distinct metabolic profiles

The analysis of metabolic profiles of tumor-infiltrating γδ lymphocytes (γδ TILs) presented a major challenge: the low numbers that can be retrieved from tumor lesions in mice are largely incompatible with techniques such as Seahorse metabolic flux analysis. To overcome this difficulty, we used a newly developed protocol, SCENITH™ (Single Cell mEtabolism by profiling Translation inHibition), which is a flow cytometry-based method for profiling energy metabolism with single cell resolution23. This method is based on metabolism-dependent translation rates and puromycin’s incorporation into nascent proteins (Extended Data Fig. 1). The use of specific inhibitors allows the estimation of glucose dependence, mitochondrial dependence, glycolytic capacity and fatty acid and amino acid oxidation (FaaO) capacity. We employed SCENITH™ to analyze the metabolic profiles of γδ TILs isolated from tumor lesions in well-established mouse models of breast (E0771) and colon (MC38) cancer. In both cancer models, and at both later (Fig. 1a,b) and earlier time points (Fig. 1c,d), we observed that γδIFN cells had substantially higher glycolytic capacity, whereas γδ17 cells were strongly dependent on mitochondrial activity (Fig. 1). These data, obtained in cancer models, prompted us to investigate the metabolic phenotypes of γδ T cell subsets in multiple tissues at steady state.

Figure 1. Intra-tumoral γδ T cell subsets display distinct metabolic profiles.

(a-d) Puromycin MFI of tumour-infiltrating γδ17 and γδIFN T cells extracted from E0771 breast (a,c) and MC38 colon (b,d) tumor-bearing mice analysed using SCENITH™ in; control conditions (Co), or after the addition of 2-deoxy-D-glucose (DG), oligomycin (O) or both inhibitors (DGO). Graphs show the percentage of glucose dependence, mitochondrial dependence, glycolytic capacity and fatty acid and amino acid oxidation (FaaO) capacity of tumor-infiltrating γδ17 and γδIFN cells isolated either 6-days (c: glucose dependence (p=0.0041), mitochondrial dependence (p<0.0001), glycolytic capacity (p=0.0014) and FaaO (p=0.0041); d: glucose dependence (p<0.0001), mitochondrial dependence (p=0.0345), glycolytic capacity (p=0.0189) and FaaO (p<0.0001)) or 15-days (a,b: mitochondrial dependence (p<0.0001), glycolytic capacity (p<0.0001)), after cancer cell line injection. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n=3 mice per group in triplicates in each experiment). pi: post-injection. γδ17 and γδIFN T cells represents IL-17 and IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells, respectively. Error bars show mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****<0.0001 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

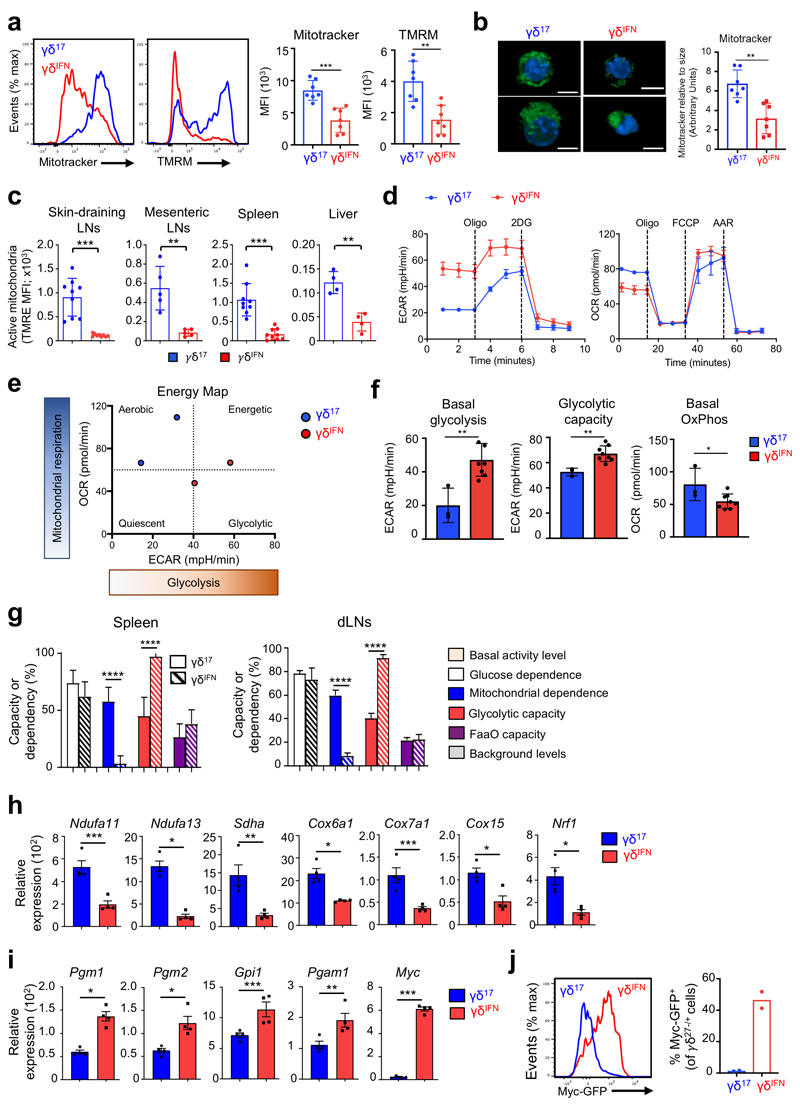

Peripheral γδ T cell subsets show different mitochondrial and metabolic phenotypes

To explore the metabolic differences between γδ T cell subsets in peripheral tissues, we analysed mitochondria, given their central role in cellular metabolism. To distinguish between γδIFN and γδ17 cells we used CD27 expression18–21. CD27– γδ (γδ17) cells displayed increased mitotracker and tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) staining in peripheral lymph nodes (LNs) compared to CD27+ γδ (γδIFN) cells, indicating higher mitochondrial mass (normalized to cell size) and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), respectively (Fig. 2a,b). These differences were retained upon activation and expansion in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 2). Importantly, the distinct mitochondrial phenotypes were also validated with another mitochondrial membrane potential dye, tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE), and were features of γδ17 and γδIFN cells ex vivo from multiple locations (Fig. 2c). In agreement with mitochondrial enrichment in γδ17 cells, seahorse metabolic flux analysis of peripheral γδ T cells showed higher levels of basal OXPHOS in γδ17 cells, and conversely, increased basal levels of glycolysis in γδIFN cells (Fig. 2d-f). These data were validated in independent experiments using SCENITH™ on splenic and LN γδ T cell subsets (Fig. 2g).

Figure 2. Peripheral γδ T cell subsets show different mitochondrial and metabolic phenotypes.

(a) Representative plots (left) and summary graphs (right) of the MFI of mitotracker and tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) in γδ27– (γδ17) and γδ27+ (γδIFN) T cells ex vivo from LNs of C57BL/6 mice (n=7; data pooled from 2 experiments; Mitotracker p=0.0003; TMRM p=0.0015). (b) Representative confocal images (left) of γδ17 and γδIFN T cells stained with mitotracker (green) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bar represents 5μM. Analysis of mitotracker staining relative to cell size (right) in γδ17 and γδIFN cells ex vivo. Relative mitotracker was calculated by dividing the MFI of mitotracker by the MFI of FSC-A and multiplying by 100 (n=7, data pooled from 2 independent experiments; p=0.0012). (c) Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) MFI of γδ17 and γδIFN T cells from skin draining LNs, mesenteric LNs, spleen and liver of WT mice. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (n=3 mice per group and experiment; sdLN p=0.0003; mLN p=0.0095; spleen p=0.0001; liver p=0.0016). (d) Seahorse extracellular flux analysis of extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of γδ17 and γδIFN T cells (expanded in vitro) from LNs (γδ17 n=2, γδIFN n=5, data representative of 3 independent experiments). (e) Energy map showing ECAR vs OCR of γδ17 and γδIFN T cells. Each symbol represents average basal metabolism. (f) Basal glycolytic rate, glycolytic capacity and basal OxPhos of γδ17 (n=3) and γδIFN (n=8) cell subsets (data pooled from 2 independent experiments; basal glycolysis p=0.0029; glycolytic capacity p=0.0042; basal OxPhos p=0.0339). (g) Percentage of glucose dependence, mitochondrial dependence, glycolytic capacity and fatty acid and amino acid oxidation (FaaO) capacity of γδ17 and γδIFN cells from spleen and draining lymph nodes (dLNs). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (n=3 mice in triplicates per group and per experiment). (h,i) OxPhos-related genes (Ndufa11, p=0.0009; Ndufa13, p=0.0214; Sdha, p=0.0027; Cox6a1, p=0.0235; Cox7a1, p=0.0002; Cox15, p=0.0204; Nrf1, p=0.0248) and glycolysis-related genes (Pgm1, p=0.0226; Pgm2, p=0.0514; Gpi1, p=0.0003; Pgam1, p=0.0018; Myc, p=0.0002) were measured by qPCR in purified γδ17 (n=4) and γδIFN (n=4) cells from spleen and dLN from WT mice. (j) Representative plot (left) and percentages (right) of Myc-GFP+ γδ17 and γδIFN cells from LNs of Myc-GFP reporter mice (n=2). Error bars show mean ± SEM or SD, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****<0.0001 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To assess if this metabolic dichotomy had an underlying transcriptional basis, we measured the mRNA levels of key mitochondrial and glycolysis-associated genes in purified peripheral γδ17 and γδIFN cells. We found systematic biases in gene expression that matched the differential metabolic programs (Fig. 2h,i). Of particular note is the clear-cut segregation of two master transcriptional regulators: Nrf1, which orchestrates mitochondrial DNA transcription24,25, found to be enriched in γδ17 cells (Fig. 2h); and Myc, which controls glycolysis26,27, that was highly overexpressed in γδIFN cells (Fig. 2i). Myc expression was further validated using a Myc-GFP reporter mouse (Fig. 2j). These data collectively demonstrated that γδ T cell subsets possess distinct mitochondrial and metabolic features in peripheral organs at steady state.

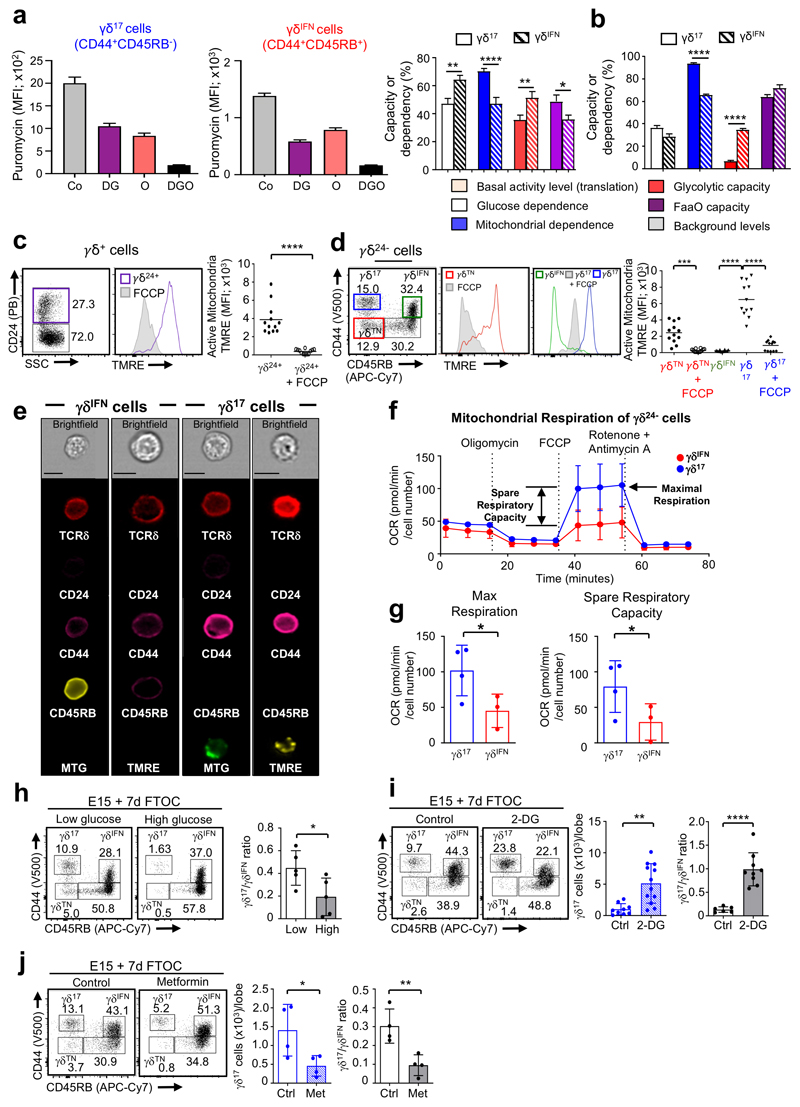

γδ T cell subsets are metabolically programmed in the thymus

We next aimed to understand when, during their differentiation, the metabolic differences between the two effector γδ T cell subsets were established. Since most γδ T cells are functionally pre-programmed in the thymus, we examined γδ thymocyte sub-populations. Studies have identified sequential stages of thymic γδ T cell progenitor development marked by CD24, CD44 and CD45RB19. Early CD24+ (γδ24+) precursors downregulate CD24 to become a CD24–CD44–CD45RB– (γδTN) population that generates cells committed to either IL-17 or IFN-γ expression, which display respectively CD44hiCD45RB– (γδ17) and CD44+CD45RB+ (γδIFN) phenotypes (Extended Data Fig 3). By using SCENITH™, we found that, in both the adult (Fig. 3a) and newborn (Fig. 3b) thymus, these subsets showed the same metabolic dichotomy as in the periphery (Fig. 2g), although this was less distinct in γδ thymocytes, likely due to the dynamic subset segregation process19.

Figure 3. γδ T cell subsets are metabolically programmed in the thymus.

(a) Puromycin MFI of γδ17 (CD44hiCD45RB–) and γδIFN (CD44+CD45RB+) T cells from WT adult thymus in resting conditions (Co) and after the addition of 2-deoxy-D-glucose (DG), oligomycin (O) or both (DGO). Histogram (right) shows the percentage of glucose dependency (white; p=0.0029), mitochondrial dependency (blue; p<0.0001), glycolytic capacity (red, p=0.0018) and fatty acid and amino acid oxidation (FaaO) capacity (purple, p=0.0304) of thymic γδ17 and γδIFN cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n=5 mice in triplicates per group and per experiment). (b) Histograms shows the percentage of glucose dependency (white), mitochondrial dependency (blue; p<0.0001), glycolytic capacity (red; p<0.0001) and fatty acid and amino acid oxidation (FaaO) capacity (purple) of γδ17 and γδIFN T cells from WT newborn thymus (d3). Data are representative of three independent experiments (n=6 mice in triplicates per group and per experiment). (c) Flow cytometry profile and Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) MFI of thymic γδ24+ precursors treated or not with FCCP (p<0.0001). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (data points represent at least 4 lobes pooled per group and per experiment). (d) Flow cytometry profiles and TMRE MFI of thymic γδTN (CD44–CD45RB–), γδ17 (CD44hiCD45RB–) and γδIFN (CD44+CD45RB+) cells treated or not with FCCP. γδTN vs γδTN+FCCP (p=0.0002), γδIFN vs γδ17 (p<0.0001), and γδ17 vs γδ17+FCCP (p<0.0001). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (data points represent at least 4 lobes pooled per group and per experiment). (e) Imagestream analysis of γδ17 and γδIFN cells stained with either mitotracker green or TMRE. Scale bar represents 7μm. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (f) O2 consumption rates (OCR) of γδ17 and γδIFN cells from thymuses of 5-day old B6 pups were measured by Seahorse extracellular flux analysis in real-time under basal conditions and in response to indicated mitochondrial inhibitors. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (pooled thymic lobes from n>10 mice per group per experiment). (g) Histograms show maximal respiration potential (p=0.0278) and spare respiratory capacity (p=0.0332) by measuring oxygen consumption rates (OCR) of γδ17 and γδIFN cells from thymuses of 5-day old B6 pups. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (pooled thymic lobes from n>10 mice per group per experiment). (h-j) Flow cytometry profiles of thymic γδTN, γδ17 and γδIFN cells from 7-day FTOC of E15 thymic lobes either with media containing low (5mM) or high (25mM) glucose (h), or with or without 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) (i) or metformin (j). Histograms show the number of γδ17 cells (2-DG p=0.0013; metformin p=0.0426) and γδ17/γδIFN cell ratio (glucose p=0.0354; 2-DG p<0.0001; metformin p=0.0079). Data are representative of 2 (h) or 3 (i-j) independent experiments (at least 4 lobes pooled per group per experiment). Error bars show mean ± SEM or SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 using unpaired or paired two-tailed Student’s t-test or One-way ANOVA test with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

To investigate any potential switching of metabolic programming during γδ thymocyte development, we first compared early thymic γδ progenitors with more mature subpopulations already committed to IL-17 or IFN-γ production. We found that γδ24+ and γδTN progenitors stained highly for TMRE, that was lost when ΔΨm was dissipated by the ionophore carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (Fig. 3c,d). Although γδ17 cells retained a high level of TMRE staining, γδIFN cells showed a marked reduction in ΔΨm suggesting a metabolic switch away from OxPhos (Fig. 3d). Moreover, imagestream analysis of γδ17 cells stained with either mitotracker or TMRE revealed large and active mitochondria, in contrast with γδIFN cells that displayed negligible staining for either dye (Fig. 3e), in line with our previous observations in peripheral subsets (Fig. 2a-c). Furthermore, Seahorse extracellular flux analysis showed that γδ17 thymocytes have both higher maximal respiration potential and spare respiratory capacity than their γδIFN counterparts (Fig. 3f,g). Thus, γδ T cell subsets acquire distinct mitochondrial features during their acquisition of effector function in the thymus.

The adoption of divergent metabolic programs by thymic γδ T cell subsets suggested they could thrive under distinct metabolic environments. To begin to address this, we placed WT E15 thymic lobes in 7-day fetal thymic organ cultures (E15 + 7d FTOC) with media containing either low or high amounts of glucose (Fig. 3h). γδ17 cells were readily detected in lower glucose conditions but failed to develop to normal numbers when glucose concentrations were raised. By contrast, γδIFN cells were relatively enriched in high glucose conditions as demonstrated by a significant decrease in the γδ17/γδIFN cell ratio (Fig. 3h). We next established E15 + 7d FTOC in the presence of the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), and found increased numbers of γδ17 cells and increased γδ17/γδIFN cell ratios (Fig. 3i). A similar result was observed in E15 + 7d FTOC when cultured with Fasentin that blocks glucose uptake (Extended Data Fig. 4). By contrast, running E15 + 7d FTOC in the presence of metformin, which reduces the efficiency of OxPhos by inhibiting complex I of the electron transport chain, impaired γδ17 cell generation and decreased the γδ17/γδIFN cell ratio (Fig. 3j). Collectively, these results suggest that the mitochondrial characteristics adopted by γδ17 and γδIFN cells during thymic development directly impact their ability to thrive in distinct metabolic environments.

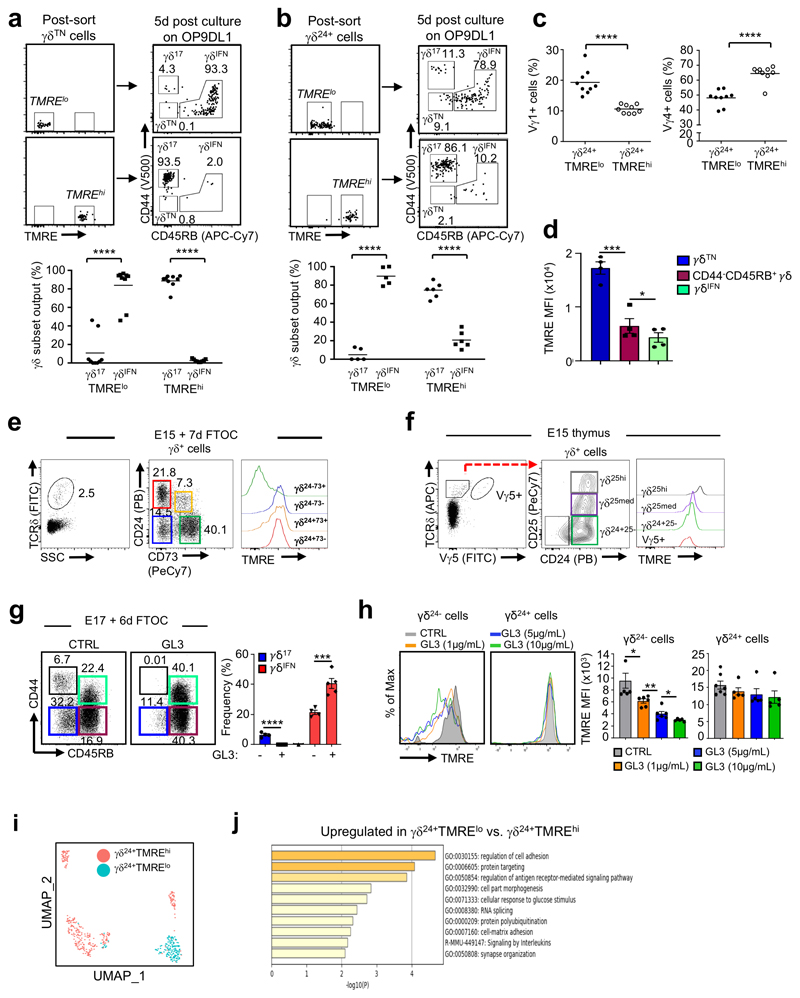

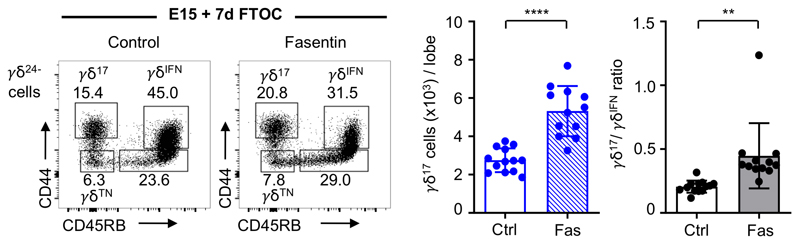

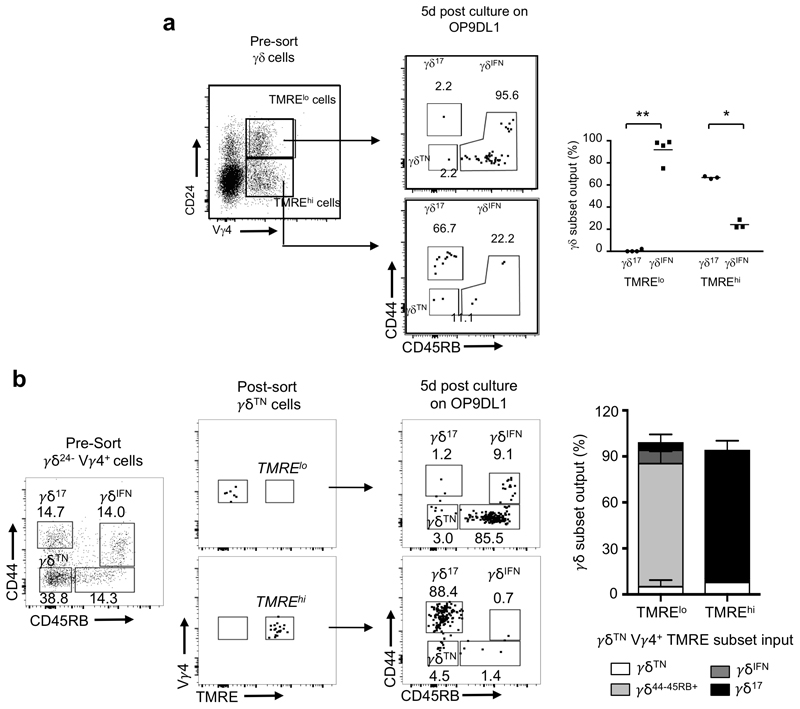

Distinct mitochondrial activities underlie effector fate of thymic γδ T cell precursors

We next aimed to investigate the association of distinct metabolic programs with the developmental divergence of γδ17 and γδIFN cells in the thymus. Although the γδTN population, i.e. the progenitor γδ cell subset that immediately precedes the surface upregulation of either CD44 or CD45RB (marking commitment to the IL-17 or IFN-γ pathways, respectively19) was predominantly TMREhi, we observed a fraction of cells with reduced TMRE staining that we reasoned might be transitioning to the TMRElo state shown by γδIFN cells (Fig. 3c). We further hypothesized that the metabolic status of γδTN progenitors may predict their developmental fate. To test this, we sorted TMREhi and TMRElo cells from the γδTN subset obtained from E15 + 7d FTOC, and cultured them for 5-days on OP9-DL1 cells that are known to support appropriate development of thymocytes28. As predicted, virtually all cells from the TMRElo cultures upregulated CD45RB and entered the IFNγ-pathway (Fig. 4a); however, we were surprised that almost all cells from the TMREhi cultures entered the CD44hi IL-17-pathway (Fig. 4a). This strongly suggests that γδTN cells have already committed to an effector fate, and that this commitment associates with distinct mitochondrial activities.

Figure 4. Distinct mitochondrial activities underlie effector fate of thymic γδ T cell progenitors.

(a,b) Flow cytometry profiles and percentage of thymic γδ17 and γδIFN cell output from sorted TMRElo and TMREhi γδTN cells (a) or γδ24+ cells (b) after 5-day culture on OP9DL1 cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (n = 4 mice pooled per group per experiment). (c) Percentage of Vγ1+ and Vγ4+ cells in TMRElo and TMREhi γδ24+ progenitors. Vγ1+ TMRElo vs TMREhi p<0.0001 and Vγ4+ TMRElo vs TMREhi p<0.0001. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (cells sorted from n=4 mice pooled per group per experiment). (d) TMRE MFI of thymic γδTN (CD44–CD45RB–), CD24–CD44–CD45RB+ γδ T cells and γδIFN cells (CD44+CD45RB+) from 6-day FTOC of E17 B6 thymic lobes; γδTN vs CD44–CD45RB+ γδ T cells (p=0.002); and CD44–CD45RB+ γδ T cells vs γδIFN cells (p=0.0301). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n=4 thymi pooled per point per group and per experiment). (e) TMRE staining in CD24–CD73+, CD24–CD73–, CD24+CD73+ and CD24+CD73– γδ T cells from 7-day FTOC of E15 B6 thymic lobes. (f) TMRE staining in CD25–CD24+ (γδ24+ cells), CD25med, CD25hi and Vγ5+ γδ progenitors from E15 thymus. (g) Flow cytometry profiles of thymic γδTN, γδ17 and γδIFN cells from 6-day FTOC of E17 B6 thymic lobes stimulated or not with anti-TCRδ mAb (GL3; 1μg/ml). Graph shows percentage of γδ17 (-GL3 vs +GL3; p<0.0001) and γδIFN (-GL3 vs +GL3; p=0.0002) cells in each condition. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n=4 thymi pooled per point per group and per experiment). (h) FACS-sorted γδ24+TMREhi cells from E17 thymi were cultured (or not) for 5h with different concentrations (as indicated) of anti-TCRδ mAb (GL3). TMRE levels were analysed by flow cytometry in γδ24– and γδ24+ cells. CTRL vs GL3 (1 μg/mL), p=0.0271; GL3 (1 μg/mL) vs GL3 (5 μg/mL), p=0.0021 and GL3 (5 μg/mL) vs GL3 (10 μg/mL), p=0.0475). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n=3 mice pooled per group per experiment). (i) Single-cell RNAseq clustering of TMRElo and TMREhi γδ24+ cells from E15 + 2d FTOC using UMAP. (j) GO term analysis of genes upregulated in TMRElo versus TMREhi γδ24+ cells shown in (i). Error bars show mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To pursue this hypothesis further, we tested γδ24+ progenitors that immediately precede the γδTN subset; again, we observed a segregation of effector fate, with the majority of TMRElo γδ24+ cells entering the IFNγ-pathway, and the majority of TMREhi γδ24+ cells entering the IL-17-pathway (Fig. 4b). The observation that so few TMREhi γδ24+ cells adopt an IFNγ-secreting fate again suggests that most γδ24+ progenitors have already committed to subsequent effector function. Moreover, we found that differences in TMRE levels correlated with the known18,20,21 effector biases of Vγ1+ (γδIFN-biased) and Vγ4+ (γδ17-biased) progenitors (Fig. 4c); and allowed TMRE-based segregation of effector fates using only Vγ4+ progenitors (Extended Data Fig. 5). Furthermore, among γδ24– thymocytes along the γδIFN pathway, we observed a progressive downregulation of TMRE levels from γδTN to CD44–CD45RB+ cells and finally γδIFN cells (Fig. 4d).

Given that we and others20,21 have previously shown a key role for TCR signalling in γδIFN thymocyte differentiation, we next asked if downregulation of TMRE levels associated with hallmarks of TCR signalling. Indeed, we found that low TMRE associated with high expression of CD73 (Fig. 4e), one of the best established markers of TCR signalling in γδ T cell development20,28,29. Moreover, in E15 thymic lobes, TMRE staining was reduced along with CD25 downregulation, which is another hallmark of (developmentally early) TCRγδ signalling18,20,21 (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, at this E15 stage, the cells with the lowest TMRE staining were Vγ5+ progenitors (Fig. 4f) that are known to engage a Skint1-associated TCR-ligand in the thymus and to uniformly commit to the IFNγ-pathway30.

These lines of evidence suggested that γδ progenitors receiving agonist TCRγδ signals shift away from OxPhos as indicated by their reduced ΔΨm. To strengthen this point, we manipulated TCR signals using agonist GL3 mAb, which, as expected18,19, promoted γδIFN cell development while inhibiting the γδ17 pathway in E17 + 6d FTOC (Fig. 4g). Upon specifically sorting TMREhi γδ24+ cells from E17 thymi and stimulating them with GL3 for 5h, we found a subpopulation that downregulated CD24 together with TMRE levels, in a mAb dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4h). These results strongly suggest that TCR signalling leads to ΔΨm downregulation as γδ thymocytes differentiate into IFN-γ producers.

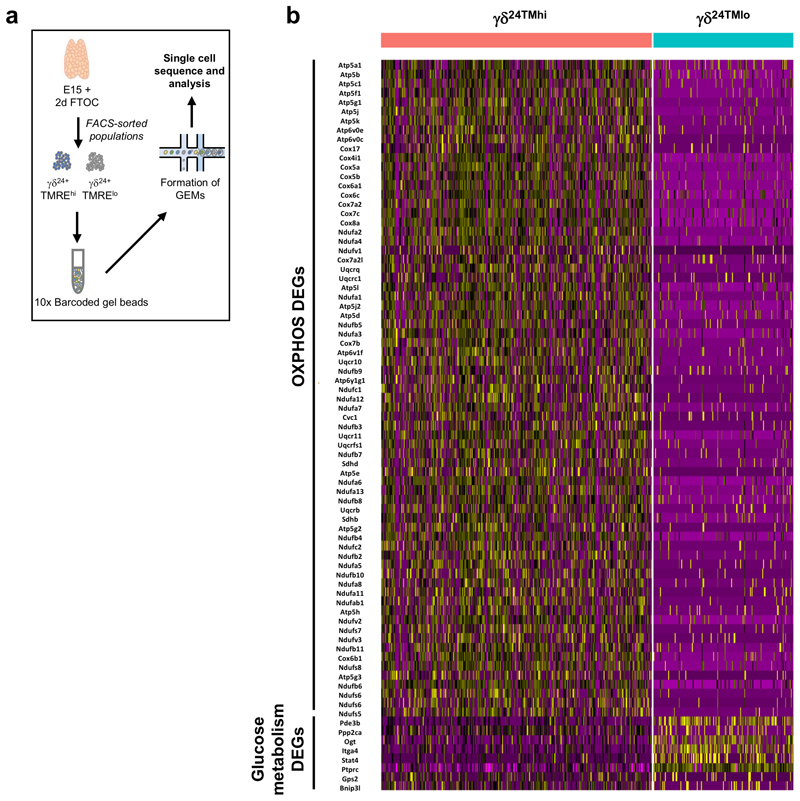

To gain further molecular resolution, we performed single-cell RNAsequencing on TMRElo and TMREhi γδ24+ cells from E15 + 2d FTOC (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Dimensionality reduction using UMAP showed that TMRElo cells clustered clearly away from TMREhi γδ24+ cells (Fig. 4i), and the former were enriched in genes involved in the regulation of antigen receptor signalling (Fig. 4j). In support of the metabolic phenotypes observed ex vivo, genes associated with OxPhos were enriched specifically in TMREhi γδ24+ cells while genes involved in glucose metabolism were unregulated in TMRElo γδ24+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 6b).

These data collectively demonstrate that metabolic status of thymic γδ progenitors marks their developmental fate from a very early stage. Progenitors entering the IL-17 pathway display sustained high mitochondrial activity, whereas those in the IFN-γ pathway undergo a TCR-induced metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis. We next questioned how these intrinsic metabolic differences impacted the physiology of effector γδ T cell subsets.

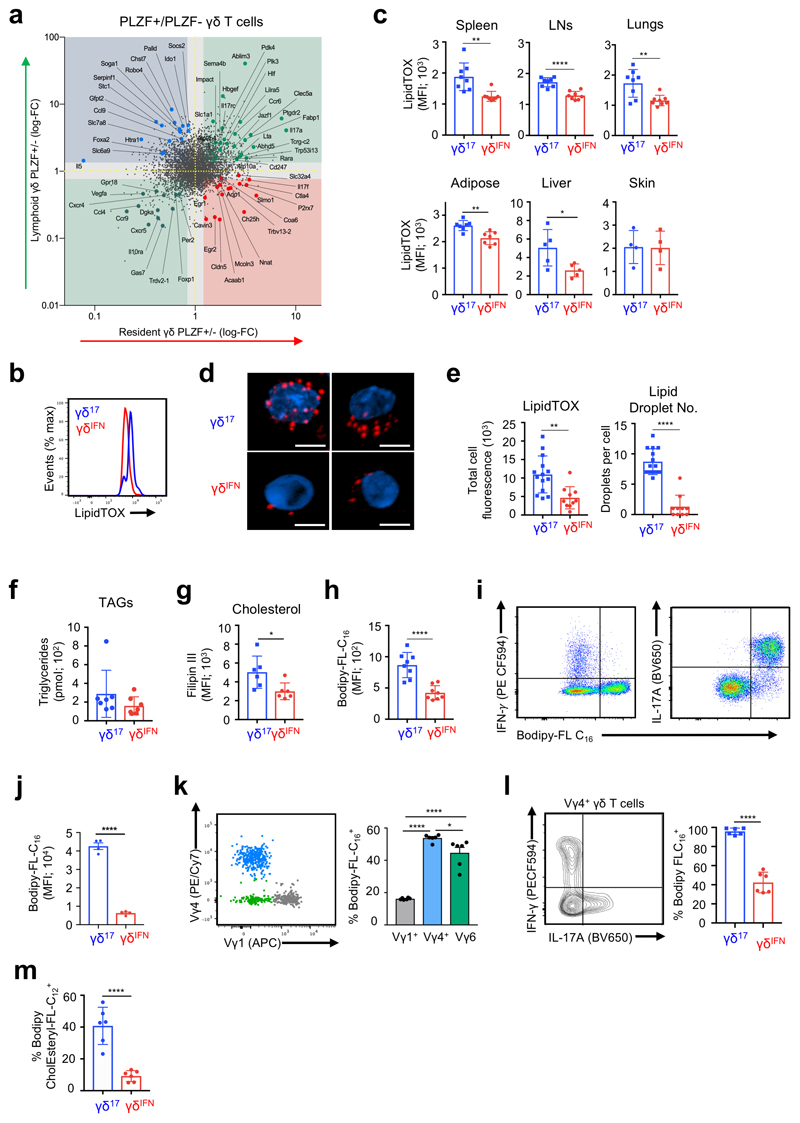

Enrichment of lipid storage and lipid metabolism in γδ17 cells

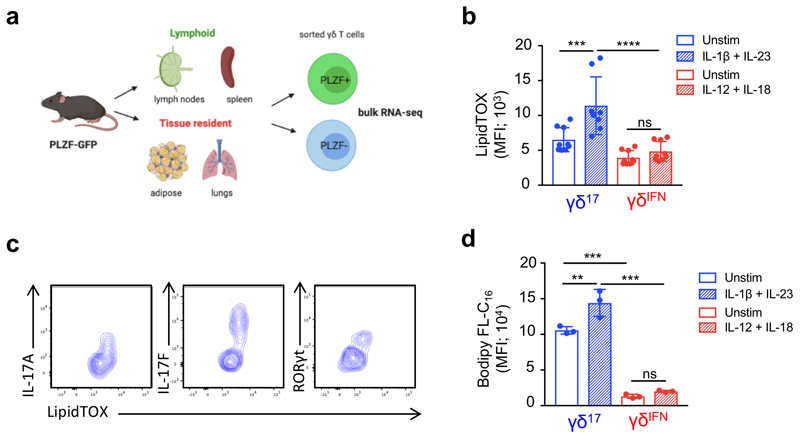

Having shown that, in stark contrast to γδIFN cells, γδ17 cell generation was reduced under high glucose concentrations (Fig. 3h), and enhanced upon inhibition of glycolysis (Fig. 3i) or glucose uptake (Extended Data Fig. 4), we questioned whether other metabolic resources may be important for γδ17 cell physiology. To address this question we took advantage of Zbtb16 GFP reporter mice to segregate γδ17 and γδIFN cells (Zbtb16 encodes the transcription factor PLZF21,14,31). We performed RNA-sequencing of lymphoid and tissue-resident γδ T cells sorted into PLZF+ (γδ17) and PLZF– (γδIFN) cells (Extended Data Fig. 7a). As expected, γδ17 cells across tissues expressed Il17a, whereas Il17f was also expressed in tissue-resident γδ17 cells (Fig. 5a). Different metabolic pathways were associated with lymphoid versus tissue resident γδ T cells. However, the genes common to γδ17 cells across all tissues were related to lipid and mitochondrial metabolism, including glutamate transporter (Slc1a1), glucose/fatty acid metabolism (Pdk4), mitochondrial protein transport (Ablim3) and lipid metabolism (Fabp1, Abdh5, Atp10a). These data highlight genes associated with lipid metabolism as a common feature of γδ17 T cells across tissues. Consistent with this, LN γδ17 cells had a higher neutral lipid content (assessed by LipidTOX staining) than γδIFN cells (Fig. 5b). This differential lipid content was further increased upon activation with IL-1β+IL-23 (Extended Data Fig. 7b), was associated with expression of IL-17A, IL-17F and RORγt (Extended Data Fig. 7c), and was observed across γδ T cells from multiple tissues, with the notable exception of the skin (Fig. 5c), where γδ T cells have been shown to display specific mechanisms of tissue adaptation32. In particular, Vγ6+ γδ T cells in the dermis are transcriptionally distinct from those in pLNs and display a highly activated but less proliferative phenotype. This tissue adaptation may alter the metabolic requirements of skin-resident γδ T cells and γδ T cells may adapt to utilize specific metabolites present within the skin33.

Figure 5. γδ17 cells show higher lipid uptake and lipid droplet content than γδIFN cells.

(a) Quadrant plot of genes upregulated in bulk RNA-sequencing of tissue resident PLZF+ γδ T cells (lower right), lymphoid PLZF+ γδ T cells (upper left), PLZF+ γδ T cells from all tissues (upper right) or PLZF– γδ T cells from all tissues (lower left). Cells were isolated from PLZF-GFP (Zbtb16 GFP) mice. (b) Representative histogram of neutral lipid staining (LipidTOX) in γδ17 (CD27–) and γδIFN (CD27+) cells from LNs ex vivo. (c) LipidTOX MFI in γδ17 and γδIFN cells from spleen (p=0.0021), LNs (p<0.0001), lungs (p=0.0043), adipose (p=0.0018), liver (p=0.031) and skin (p=0.9442) (n=5-8, data pooled from 2 independent experiments). (d) Confocal imaging of γδ17 and γδIFN cells expanded in vitro and stained with LipidTOX (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bar represents 5μM (data representative of a minimum 10 images from 2 independent experiments). (e) Quantification of confocal imaging as shown in (d) (each data point represents the average per cell per image; LipidTOX p=0.0018; lipid droplet no. p<0.0001). (f) Quantification of triglyceride (TAG) levels from γδ17 and γδIFN cells expanded in vitro (n=7, each symbol represents one biological replicate). (g) Filipin III staining of γδ17 and γδIFN cells ex vivo from LNs. Representative histogram (left) and MFI (right) (n=6, data pooled from 2 independent experiments; p=0.0276). (h) Representative histogram of Bodipy-FL-C16 uptake in γδ17 and γδIFN cells from LNs ex vivo (n=8, data pooled from 2 independent experiment). (i) Representative plots of Bodipy-FL-C16 uptake and IL-17 or IFN-γ production by γδ17 and γδIFN cells from LNs stimulated with PMA/ionomycin. (j) Bodipy-FL-C16 MFI in IFN-γ+ and IL-17+ γδ T cells (n=4, data representative of 3 independent experiments). (k) Representative plot of Vγ1 and Vγ4 expression in total γδ T cells and percentage Bodipy-FL-C16 uptake by LN γδ T cell subsets (Vγ1+, Vγ4+, Vγ1–4–) (n=6, data pooled from 2 independent experiments; Vγ1 vs Vγ4/Vγ6 p<0.0001; Vγ4 vs Vγ6 p=0.0143). (l) Representative IFN-γ and IL-17 production by Vγ4+ γδ T cells from LNs and percentage Bodipy-FL-C16 uptake by Vγ4+IFN-γ+ and Vγ4+IL-17+ γδ cells (n=6, data pooled from 2 independent experiments). (m) Percentage Bodipy CholEsteryl FL-C12 uptake by γδ17 (CD27–) and γδIFN (CD27+) cells from LNs ex vivo (n=6, data pooled from 2 independent experiments). Error bars show mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Imaging analysis revealed that the increased LipidTOX staining was due to the accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets in γδ17 cells (Fig. 5d,e). Lipid droplets store neutral lipids including triglycerides (TAGs) and cholesterol esters34. The two γδ T cell subsets had equivalent TAG content (Fig. 5f) but free cholesterol, as determined by Filipin III staining, was higher in γδ17 cells (Fig. 5g). We next questioned if γδ17 cells engaged in lipid uptake which could account for lipid storage. Using labelled palmitate (Bodipy-FL-C16), we found that γδ17 cells selectively took up lipids (Fig. 5h), which was further enhanced following activation (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Analysis of γδ T cell cytokine production confirmed that the ability to take up palmitate was specific to IL-17 producers (Fig. 5i,j). Of note, Vγ4+ and Vγ6+ (Vγ1–Vγ4–) γδ T cells showed a higher palmitate uptake than Vγ1+ cells (Fig. 5k). While Vγ6+ γδ T cells primarily produce IL-17, Vγ4+, can produce either IFN-γ or IL-1718,19. However, palmitate uptake was specific to Vγ4+ cells that produced IL-17 (Fig. 5l). Furthermore, γδ17 cells also displayed higher uptake of fluorescently labelled cholesterol ester (Bodipy CholEsteryl FL-C12) (Fig. 5m), emphasizing their ability to take up multiple types of lipids including fatty acids and cholesterol.

These data demonstrate that γδ17 cells have an exquisite capacity to take up and accumulate intracellular lipids, and display transcriptional signatures of enhanced lipid metabolism compared to γδIFN cells.

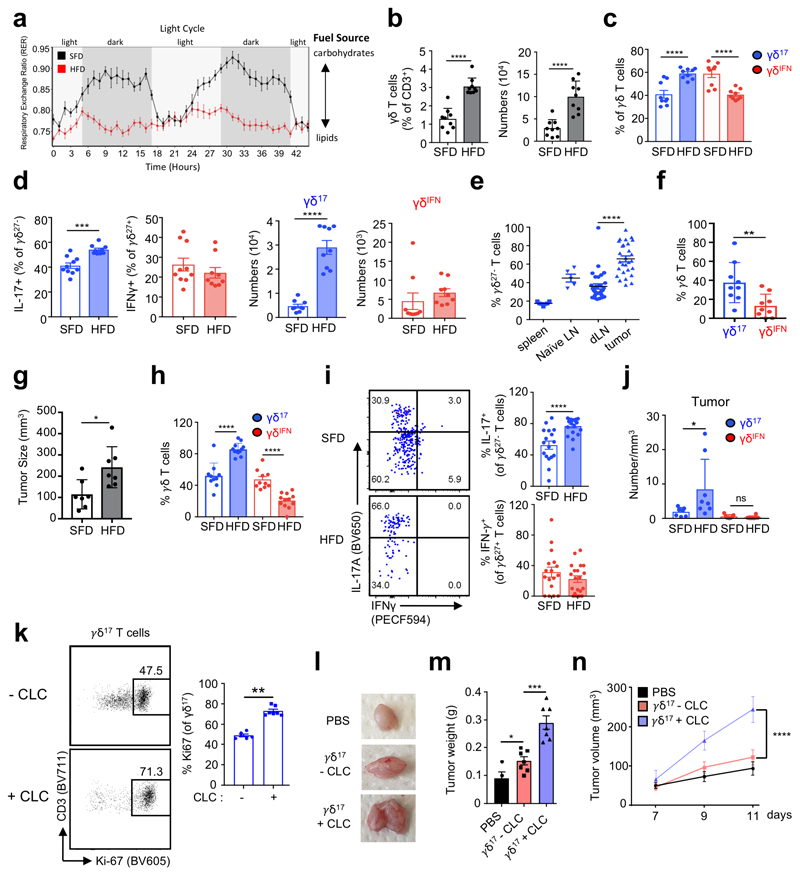

High fat diet promotes γδ17 cell expansion and their accumulation in tumors

We next tested the effect of a lipid-rich, high fat diet (HFD), on γδ T cell subsets in vivo. Unlike standard fat diet (SFD) fed mice, which alternate between using lipids or carbohydrates for fuel during light/dark cycles respectively, feeding mice a HFD reduced their respiratory exchange ratio (RER), illustrating a systemic metabolic switch to constantly burning lipids as the main fuel source. (Fig. 6a). We found that both the percentage and absolute number of LN γδ T cells were increased during HFD (Fig. 6b), which was due to a specific increase in γδ17 (but not γδIFN) cells (Fig. 6c,d).

Figure 6. High fat diet promotes the expansion of pro-tumoral γδ17 cells in lymph nodes and within tumors.

(a) Respiratory exchange ratio (RER) of mice fed SFD or HFD for 8 weeks (n=3, data from 1 experiment). (b) Bar graphs showing the percentage and absolute numbers of CD3+ γδ T cells from LNs of standard fat diet (SFD) and high fat diet (HFD) mice (n=9, data pooled from 3 independent experiments). (c) Proportion of γδ17 (CD27–) and γδIFN (CD27+) T cells in LNs of SFD and HFD fed mice (n=9, data pooled from 3 independent experiments). (d) Percentage and absolute numbers of CD27+ IFN-γ+ and CD27– IL-17+ γδ T cells from LNs of SFD and HFD mice (n=9, data pooled from 3 independent experiments). (e) Proportion of infiltrating γδ17 cells in spleen, draining LN and tumor in the B16 tumor model (dLN and tumor n=30, data pooled from 4 independent experiments, spleen n=7, naïve LN n=5). (f) Bar graph showing the percentage of γδ17 and γδIFN cells infiltrating tumors (n=9, data pooled from 2 experiments). (g) Bar graph represents the size of s (mm3) in SFD and HFD fed mice. (n=7, representative of 3 independent experiments). (h) Bar graph showing proportion of infiltrating γδ17 (CD27–) and γδIFN (CD27+) cells in tumors of SFD and HFD fed mice (SFD n=10, HFD n=12, data pooled from 2 independent experiments). (i) Representative plots of IL-17 and IFN-γ expression in γδ T cells infiltrating tumors of SFD and HFD fed mice. Bar graphs represent the percentage of γδ17 and γδIFN cells infiltrating tumors (SFD n=17, HFD n=20, data pooled from 3 independent experiments). (j) Bar graph showing the number/mm3 of γδ17 and γδIFN cells in tumors of mice on SFD or HFD (SFD n=7, HFD n=8, data pooled from 2 independent experiments). (k) Plots of proliferating Ki67+ γδ17 cells cultured for 5h with or without cholesterol-loaded cyclodextrin (CLC). Graph represents the percentage of Ki67+ γδ17 cells (data are representative of two independent experiments; pool of 3-5 mice per experiment). (l) γδ17 cells cultured (or not) with cholesterol-loaded cyclodextrin (CLC) for 5h were injected s.c. into E0771 tumors at d7 and d9 after tumor cell injection. Representative picture of tumors observed at day 11 post-E0771 cell inoculation. (m) Graph showing tumor weight at day 11 post-E0771 inoculation. CTRL vs γδ17-CLC (p=0.0361); γδ17-CLC vs γδ17+CLC (p=0.0003). (n) E0771 tumor growth was monitored every two days after inoculation. (l-n) data are representative of three independent experiments (n=3 mice per experiment); p<0.0001. Error bars show mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA test with Sidak post-hoc analysis.

Tumors are another site reported to be lipid-rich. To explore the effect of the lipid-rich tumor environment on γδ17 cells, we employed the B16F10 melanoma model. In SFD mice, we found an enrichment of γδ17 cells within the tumor compared to draining LN (dLN) or spleen (Fig. 6e). These γδ17 cells were also enriched compared to γδIFN cells (Fig. 6f). Given γδ17 were enriched in obese mice and in the tumor, we next asked if obesity combined with the tumor model would further increase γδ17 cells. Mice fed HFD exhibited enhanced tumor growth (Fig. 6g), and further increased percentages and numbers of tumor-infiltrating γδ17 cells compared to the SFD group (Fig. 6 h-j). These data demonstrate that a lipid-rich environment selectively accumulates γδ17 cells but not γδIFN cells in the tumor.

Given the preferential uptake of cholesterol by γδ17 cells (Fig. 5i), we next investigated its effect on γδ17 cell proliferation and function. We incubated purified γδ27– (γδ17) cells with cholesterol-loaded cyclodextrin (CLC), which we found to promote γδ27– cell proliferation when compared to control culture conditions (Fig. 6k). To determine its impact on tumor growth in vivo, we injected CLC pre-treated (or control) γδ17 cells twice (within two days) into s.c. E0771 tumors (as established in Fig. 1b), which allow local T cell delivery. Strikingly, γδ17 cells pre-treated with CLC substantially enhanced tumor growth (Fig. 6l-n).

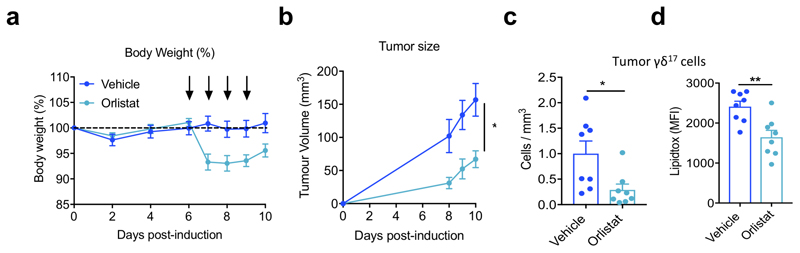

Conversely, we also tested the effect of reducing lipids in vivo, by injected orlistat, which inhibits lipases and thus prevents uptake of dietary fat, into B16F10 tumor-bearing mice. Mice injected with orlistat exhibited reduced body weight and tumor growth compared to vehicle-treated mice (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). Importantly, these mice showed decreased numbers of tumor-infiltrating γδ17 cells, which had lower neutral lipid content (Extended Data Fig. 7c,d). Together, these data show that lipid-rich environments promote the selective expansion of γδ17 cells that support tumor growth.

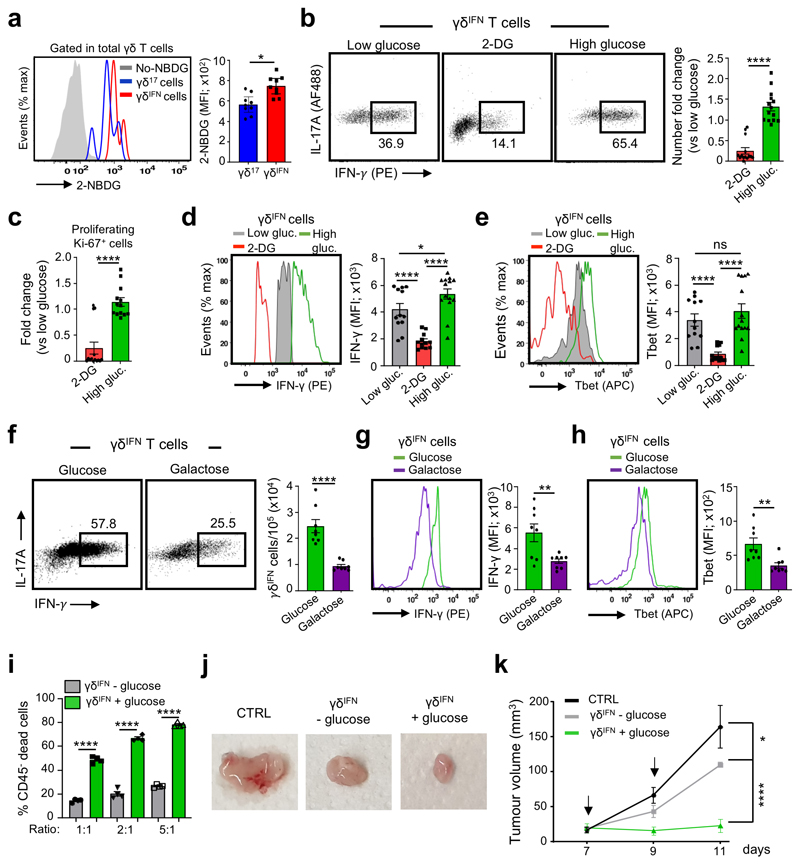

Glucose supplementation enhances anti-tumor functions of γδIFN cells

We next aimed to use the knowledge gathered in this study to boost anti-tumor γδ T cell responses, which are known to rely on γδIFN cells8,22. Given our data showing that glucose promotes the development of γδIFN over γδ17 cells in the thymus (Fig. 3h,i), and the higher glycolytic capacity of γδIFN cells in peripheral organs (Fig. 2g) and also within tumors (Fig. 1b-e), we hypothesized that glucose supplementation would enhance γδIFN cell functions. Further supporting this hypothesis, we found that intra-tumoral γδIFN cells preferentially took up fluorescently labeled glucose (2-NDBG) when compared to γδ17 TILs (Fig. 7a).

Figure 7. Glucose supplementation enhances the anti-tumor effector functions of γδIFN cells.

(a) Glucose uptake assessed upon i.v. injection of fluorescent 2-NBDG in tumor-bearing mice. Tumors were harvested 15 min later for analysis. Histogram represents 2-NBDG uptake in γδ17 and γδIFN cells (p=0.047). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group and per experiment). (b-i) Purified splenic and peripheral lymph nodes γδIFN T cells (CD3+TCRγδ+CD27+) were cultured in the presence of IL-7 with media containing low glucose (5mM), 2-deoxyglycose (2-DG), high glucose (50mM) or galactose (20mM) for 78h. (b) Plots of peripheral γδIFN T cells cultured with IL-7 and media containing low glucose, 2-DG or high glucose. Histogram represents the fold change in number of γδIFN T cells cultured with 2-DG or high glucose versus low glucose (p<0.0001). (c) Fold change in number of proliferating Ki-67+ γδIFN cells cultured with 2-DG or high glucose versus low glucose (p<0.0001). (d) IFN-γ expression was analysed by flow cytometry in γδIFN cells incubated with media containing low glucose, 2-DG or high glucose. Histograms show the MFI of IFN-γ. Low glucose vs 2-DG (p<0.0001); 2-DG vs High glucose (p<0.0001); Low glucose vs high glucose (p=0.0115). (e) Tbet expression was analysed by flow cytometry in γδIFN cells incubated with media containing low glucose, 2-DG or high glucose. Histograms show the MFI of Tbet. Low glucose vs 2-DG (p<0.0001); 2-DG vs High glucose (p<0.0001). (f) Flow cytometry profiles of peripheral γδIFN T cells cultured with IL-7 and media containing glucose (50mM) or galactose (20mM). Histogram represents the numbers of γδIFN T cells (p<0.0001). (g,h) IFN-γ (g) and T-bet (h) expression was analysed by flow cytometry in γδIFN cells incubated with media containing glucose or galactose (p=0.0085 for IFN-γ expression and p=0.0034 for Tbet expression). Histograms show the MFI of IFN-γ and T-bet. (i) Summary of killing assay in vitro of E0771 tumor cells by γδIFN T cells previously supplemented (or not) with glucose (5h pre-incubation); p<0.0001. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group and per experiment). (j) Representative picture of tumors observed at day 11 post-E0771 inoculation. γδIFN cells supplemented (or not) with glucose for 5h were injected into the tumor at d7 and d9 after tumor cell injection. (k) The E0771 tumor growth was monitored every two days during 11 days after E0771 inoculation. CTRL vs γδIFN - glucose (p=0.0148); γδIFN-glucose vs γδIFN+ glucose (p<0.0001). (b-e) Data are representative of 4 independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group and per experiment); (f-h) Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group and per experiment), (j,k) Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n = 5 mice per group and per experiment). Error bars show mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test or ANOVA test.

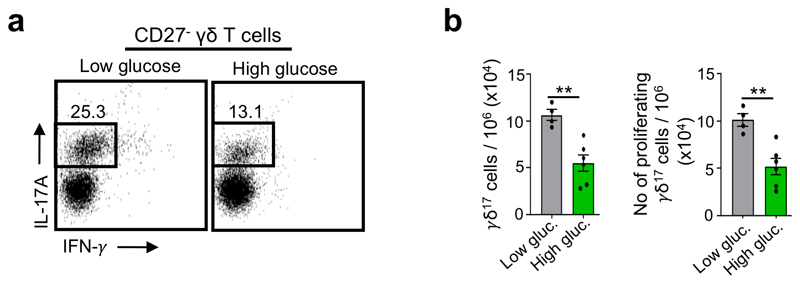

We first tested the impact of glucose on γδ17 and γδIFN cell functions in vitro. We cultured purified γδ27– (γδ17) or γδ27+ (γδIFN) cells in standard culture conditions containing low dose glucose (5mM) or in high glucose (50mM). We found high glucose to be detrimental to γδ17 cells (Extended Data Fig. 8), in stark contrast to γδIFN cells. Indeed, supplementation with high glucose augmented (whereas provision of 2-DG reduced) the percentage and numbers of γδIFN cells (Fig. 7b), with parallel effects on their proliferation (Fig. 7c) and on the levels of expression of both IFN-γ (Fig. 7d) and its master transcriptional regulator21, T-bet (Fig. 7e).

To specifically address the importance of aerobic glycolysis for γδIFN cells, we cultured γδIFN cells with galactose (compared to glucose), since cells grown in galactose enter the pentose phosphate pathway instead of using aerobic glycolysis35,36. We observed a reduction in the percentage and absolute numbers of γδIFN cells (Fig. 7f), as well as in their IFN-γ (Fig. 7g) and T-bet (Fig. 7h) expression levels, thus establishing that aerobic glycolysis is required for optimal IFN-γ production by γδIFN cells.

Next we asked if the cytotoxic function of γδIFN cells was also enhanced by glucose supplementation. For this, we co-cultured γδIFN cells that were previously supplemented (or not) with high dose of glucose with E0771 breast cancer cells at different effector:target (E:T) ratios. “Glucose-enhanced” γδIFN cells displayed substantially higher cytotoxic potency against the cancer cells, compared to the respective controls at each E:T ratio (Fig. 7i).

As γδ T cells are actively being pursued in the clinic as an adoptive cell therapy for cancer8, we tested whether we could use glucose supplementation to enhance the anti-tumor functions of γδIFN cells in vivo, in an adoptive cell transfer setting. Purified γδIFN cells were cultured in the presence or absence of high dose glucose for 5h, washed, and injected twice (within two days) into the tumor site. While control γδIFN cells produced a small yet significant reduction in tumor size, glucose substantially augmented the anti-tumor effects of γδIFN cells, essentially inhibiting tumor growth (from the time of injection) within the time window analysed (Fig. 7j,k). These data reveal a new, metabolism-based, means to enhance the anti-tumor functions of γδ T cells that could be explored for adoptive cell immunotherapy of cancer.

Discussion

Metabolism dysregulation is viewed as an immune evasion strategy in cancer. To overcome it, and thus enable anti-tumor immune responses, it is critical to understand immune cell metabolism and its interplay with tumor cells in the TME. Although our knowledge on αβ T cell metabolism has increased significantly1,3,37, little is known about γδ T cells. Here, we identified a metabolic dichotomy between the main effector γδ T cell subsets that play opposing roles in cancer immunity8,22. Whereas anti-tumoral γδIFN cells are almost exclusively glycolytic, pro-tumoral γδ17 cells require mitochondrial metabolism; and their activities within tumors can be promoted by glucose or lipid metabolism, respectively.

Unexpectedly, the metabolic dichotomy of γδ T cell subsets is established early during thymic development, which contrasts with the peripheral metabolic (re)programming of effector αβ T cells. Naïve αβ T cells require activation to undergo rewiring of cellular metabolism, namely transition from OxPhos to aerobic glycolysis, through which glucose is fermented into lactate rather than oxidized in mitochondria3. Furthermore, depending on metabolic cues in the tissue or during immune challenge, naïve T cells are pushed toward Th1, Th2, Th17 or Treg fates, dependent on intrinsic metabolic pathways engaged outside the thymus. By contrast, we show that an equivalent metabolic shift occurs in early thymic γδ progenitors as they commit to the IFN-γ pathway, seemingly as a result of strong TCRγδ signalling. Indeed, analysis of various hallmarks of TCR signalling suggest that γδ progenitors receiving agonist TCRγδ signals shifted away from OxPhos as indicated by their reduced ΔΨm. Moreover, upon TCR (GL3 mAb) stimulation, a small population of γδ progenitors downregulated CD24 together with ΔΨm (TMRE), thus associating strong TCRγδ signalling in the γδIFN developmental pathway with metabolic reprogramming. This draws a parallel with αβ T cell activation, during which early TCR signalling is required for induction of aerobic glycolysis38. This acts as a switch for Myc mRNA (and protein) expression, such that strength of TCR stimulus determines the frequency of T cells that transcribe Myc mRNA36. The common denominator of the metabolic switches in effector γδ and αβ T cells may thus be upregulation of Myc, which is required for transcription of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes26,27. Indeed, our data show a striking enrichment of Myc (mRNA and protein) in γδIFN cells compared to γδ17 cells. On the other hand, the sustained dependence of γδ17 cells on mitochondrial OxPhos is in line with that recently reported for their functional αβ T cell equivalents, Th17 cells39. Of note, IL-17-producing type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) were recently shown to require both glycolysis and mitochondrial-derived ROS for activation40, but a direct comparison with type 1 ILCs is still missing.

The concept of TCR signalling playing a key role in the metabolic programming of γδ T cell subsets builds upon, but provides a novel perspective to, previous models of their thymic development. Thus, the unequivocal dependence on strong TCR signals for γδIFN cell differentiation20,30 may be linked to a required metabolic shift to aerobic glycolysis. Moreover, the detrimental impact of agonist TCR signals on γδ17 cell development may be due to metabolic conflict with their OxPhos requirements, documented by our FTOC experiments using specific inhibitors. Importantly, these distinct metabolic phenotypes are maintained in peripheral γδ T cell subsets, which is consistent with and expands our previous epigenetic and transcriptional analyses41,42.

We were particularly interested to investigate the metabolic properties of peripheral γδ T cell subsets once they infiltrated tumor lesions, for which we employed three experimental models of cancer (melanoma, breast and colon). Critically, we found that the dichotomy between γδ17 and γδIFN subsets was preserved in the TME, which enabled metabolic interventions that may have therapeutic potential. In fact, while γδ T cell infiltration is largely perceived to associate with favourable prognosis in cancer patients43, recent clinical data have suggested that, in agreement with mouse experimental systems22, human γδ17 versus γδIFN cell subsets have antagonistic prognostic values8. Thus, improvement in the therapeutic performance of γδ T cells in the clinic44 is likely to require a better understanding of the factors that control the balance between γδ17 and γδIFN cell subsets in the TME.

Here, we also identified lipids as key γδ17-promoting factors, which is particularly relevant because tumors are known to be lipid-rich microenvironments4,5. Palmitate and cholesterol ester uptake were higher in γδ17 than γδIFN cells. Thus, we propose that the increase in intracellular lipids is due to enhanced uptake, although endogenous lipid synthesis cannot be ruled out. Our findings that γδ17 cell proliferation is boosted by cholesterol treatment, and that these cells expand substantially in obese mice, provide additional evidence that HFD causes a systemic increase in the γδ17 subset, consistent with previous findings in the skin45 and lungs46, and may provide a mechanistic understanding for this expansion. Obesity is a known risk factor for cancer and we previously demonstrated the link between obesity and suppression of NK cell anti-tumor function47. Given that γδ17 cells have strong pro-tumoral effects and we find this population to be expanded in tumors of obese mice, this may represent an additional mechanism linking cancer and obesity, whereby abundant lipids favor γδ17 over γδIFN cells to support tumor growth.

Conversely, we found γδIFN cells, from their thymic development to intra-tumoral functions, to be boosted by glucose metabolism. Naturally, the large consumption of glucose by tumor cells7 creates a major metabolic constraint on γδIFN TILs. Glucose restriction can impair T cell cytokine production5,6, while production of lactate by tumor cells performing aerobic glycolysis can inhibit T cell proliferation and cytotoxic functions48. Therefore, we do not conceive glucose supplementation as an appropriate strategy to enhance endogenous T cell (including γδIFN) responses in vivo. Instead, we suggest that it should be considered in protocols used to expand/differentiate γδ T cells ex vivo for adoptive cell therapy. Such an “in vitro glucose boost” may enable stronger anti-tumor activities (namely, IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity) upon T-cell transfer, as suggested by our data using CD27+ γδIFN cells in the breast cancer model, although evaluation of the duration and long-term impact of this “boost” requires further investigation in slower-growing tumor models.

While we did not dissect the mechanistic link between aerobic glycolysis and IFN-γ production by CD27+ γδIFN cells, previous studies on αβ T cells have shown that glycolysis controls (via the enzyme GAPDH) the translation of IFN-γ mRNA5. Moreover, glycolysis was shown to be essential for the cytotoxic activity of NK cells, namely their degranulation and Fas ligand expression, upon engagement of NK cell receptors (NKRs)49. This is particularly interesting when considering the potential of a human γδ T cell product that we developed for adoptive cell therapy of cancer, Delta One T (DOT) cells. These Vδ1+ T cells are induced in vitro to express high levels of NKRs that enhance their cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production9,50. We therefore propose high dose glucose to be added to the DOT protocol as to further increase their anti-tumor potential.

In sum, this study demonstrates that thymic differentiation of effector γδ T cell subsets, besides well-established epigenetic and transcriptional regulation, includes divergent metabolic programming that is sustained in the periphery and, in particular, in the TME. It further identifies distinct metabolic resources that control the intra-tumoral activities of γδ T cell subsets, with lipids favoring γδ17 cells and glucose boosting γδIFN cells, which provides a new metabolism-based angle for therapeutic intervention in cancer and possibly other diseases.

Methods

Ethics statement

All mouse experiments performed in this study were evaluated and approved by the institutional ethical committee (Instituto de Medicina Molecular Orbea), the national competent authority (DGAV) under the license number 019069, UK Home Office regulations and institutional guidelines under license number 70/8758 and by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, the Trinity College Dublin ethics committee. Euthanasia was performed by CO2 inhalation. Anesthesia was performed by isoflurane inhalation.

Mice and tumor cell lines

C57Bl/6J (B6) WT mice and Myc-GFP mice (B6;129-Myctm1Slek/J) were purchased from Charles River and Jackson Laboratories. PLZF-GFP (Zbtb16 GFP) mice were generated in the laboratory of D. Sant’Angelo as described previously51. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. Standard food and water were given ad libitum. Where indicated, mice were fed high fat diet (HFD) (Research Diets; D12492) for 8 weeks. Mice were used at the foetal (embryonic day 14-18), neonatal (1-5 days old) or adult (6-12 weeks old) stages.

The E0771 murine breast adenocarcinoma cells, MC38 murine colon adenocarcinoma cells and B16.F10 melanoma cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% (vol/vol) FCS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% (vol/vol) penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Tumor transplantation in vivo

Mice were injected with 1 x 106 E0771 tumor cells in fat pads, 1 x 106 MC38 tumor cells or 2 x 105 cells B16 tumor cells subcutaneously into the right shaved flank. Tumor growth was measured every 2-3 days using calipers and animals were sacrificed when tumors reached a diameter (D) of 15mm, became ulcerous, or 1 or 2 weeks after tumor injection. Tumor size was calculated using the following formula: (D1)2 × (D2/2), D1 being the smaller value of the tumor diameter. In some experiments, mice were fed with a HFD (60% calories from lard) for 10 weeks prior to tumor injection and the HFD was continued throughout the experiment.

Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System

Indirect calorimetry data were recorded using a Promethion Metabolic Cage System (Sable Systems) essentially as described previously52. Mice were housed individually in metabolic chambers under a 12h light/dark cycle at room temperature (22°C) with free access to food and water. Mice were acclimated for 24h in metabolic cages before recording calorimetric variables. Mice were fed either a standard chow diet or a high fat (60%) diet ad libitum for 8 weeks prior to being placed in metabolic cages and were maintained on either diet throughout the recording.

Tissue processing and cell isolation

Tumors were collected and digested with 1mg/mL collagenase Type I, 0.4 mg/mL collagenase Type IV (Worthington) and 10μg/mL DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cell suspensions were then filtered through a 100μm nylon cell strainer (Falcon/Corning). γδ T cells were isolated by scratching thymus, spleen and lymph node on a 70μm mesh. Lungs were minced then homogenized in RPMI 1640 using a TissueLyser (Qiagen) and filtered through 70μm mesh. Adipose tissue was processed as described previously53. Red blood cells were lysed using RBC Lysis Buffer (Biolegend) or ammonium chloride lysis buffer (made in-house). Single-cell suspensions of fetal and neonatal thymocytes were obtained by gently homogenizing thymic lobes followed by straining through 40μm strainers (BD).

For cell-sorting, γδ T cells were pre-enriched by depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, dendritic cells and B cells using biotinylated anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-CD11c (N14) and anti-CD19 (6D5) antibodies with anti-biotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech) by QuadroMACS or γδ T cells were purified using TCRγ/δ T Cell Isolation Kit, mouse (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were sorted on a FACS Aria III (BD Biosciences).

Cell Culture

CD27– γδ T cells were expanded in vitro as previously described54. This protocol was adapted to expand CD27+ γδ T cells by using 10ng/ml IL-2, 10ng/ml IL-15 and 20ng/ml IL-7. For downstream assays, γδ T cells were purified using TCRγ/δ T Cell Isolation Kit, mouse (Miltenyi Biotec). Ex vivo cultures were performed using RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine. For cytokine stimulation, cells were cultured with 10ng/ml IL-1β and IL-23 (Miltenyi Biotec) and/or IL-12 and IL-18 (BioLegend).

For short-term skin-draining-lymphocyte cultures, single-cell suspensions of lymphocytes were isolated from skin-draining lymph nodes from adult B6 mice. Cells were resuspended in complete RPMI medium (RPMI-1640 with 10% FCS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine). 1 x 106 lymphocytes in 500μl of complete medium were incubated for 48h in 48-well plates either under control conditions or with the addition of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (AICAR; 1.6mM; Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry.

Fetal Thymic Organ Cultures (FTOC)

E15-E17 thymic lobes from B6 mice were cultured on nucleopore membrane filter discs (Whatman) in FTOC medium (RPMI-1640 with 10% FCS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, 50μM β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), and 2mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich)) for 6-12 days (unless otherwise indicated). In some experiments 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; 0.6 mM), fasentin (0.6 mM), metformin (2mM) or oligomycin (1nM) were added to the cultures. All thymic organ cultures were subsequently analysed by flow cytometry. In some cultures, where concentration of glucose was manipulated, “basic” FTOC medium (RPMI-1640 [-] glucose with 10% FCS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich)) was used, and glucose was added at 5mM for “low-glucose” conditions or 25mM for “high-glucose” conditions.

In some experiments, anti-TCRδ antibody (GL3; 1μg/ml unless otherwise indicated) was added to the cultures. Cultures containing antibody were rested overnight in fresh FTOC medium before analysis. All thymic organ cultures were subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry.

Manipulation of γδ metabolic pathways in vitro and in vivo

Spleen and lymph nodes were harvested from C57Bl/6J mice. Cell suspensions were stained with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR (Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-CD3ε (145-2C11), anti-TCRδ (GL3), and anti-CD27 (LG.7F9) for 15 minutes at 4°C. CD27+ and CD27– γδ T cells were FACS-sorted. CD27+ and CD27– γδ T cells were incubated on plate-bound anti-CD3ε (145.2C11) (10μg/mL) in the presence of IL-7 (50μg/mL) or IL-7 (50μg/mL), IL-1β (10μg/mL) and IL-23 (10μg/mL), respectively. All cytokines were purchased from Peprotech. Then, cells were cultured with 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG; 2mM; Sigma-Aldrich), high D-glucose (50mM; Sigma-Aldrich), galactose (20mM; Sigma-Aldrich), Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP; 1μM; Sigma-Aldrich) and cholesterol-loaded cyclodextrin (CLC; 5 μg/mL) for 5h at 37°C for in vitro experiments.

For experiments in vivo, purified CD27– and CD27+ γδ T cells were incubated (or not) for 5h with cholesterol-loaded cyclodextrin (5μg/mL) or with high D-glucose (50mM; Sigma-Aldrich), respectively. 5 x 105 CD27– or 1 x 106 CD27+ γδ T cells were injected twice directly at the tumor site (1st injection 7 days after tumor inoculation and 2nd injection 2 days later). Mice were analyzed 11-days after tumor cell injection.

For lipid depletion in vivo, mice were injected daily with 50mg/kg Orlistat i.p. on days 6-9 after tumor injection, then tumor cell infiltrate was analyzed on day-10.

In vitro killing assays

Purified CD27+ γδ T cells were supplemented (or not) with high levels of glucose (50mM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 5h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Then, variable numbers of CD27+ γδ T cells were co-cultured with 5 x 105 E0771 breast cancer cells in complete RPMI Medium (minus D-Glucose). The killing capacities of CD27+ γδ T cells based on death of E0771 cells (Annexin V staining) was assessed by flow cytometry after 24h.

Flow cytometry

γδ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using standard procedures. For surface staining, cells were Fc-blocked with anti-CD16/32 (clone 93; eBioscience) and incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C with antibodies and LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or viability dye Zombie NIR stain (BioLegend) in FACs buffer (PBS 1X, 2% FCS, 1mM EDTA). Anti-CD3ε (145-2C11; 1:400), anti-CD27 (LG.7F9; 1:200), anti-CD25 (PC61; 1:400), anti-CD73 (TY/11.8; 1:200) and anti-Vγ2 (UC3-10A6; 1:200) were purchased from eBioscience. Anti-CD45 (30-F11; 1:400), anti-TCRδ (GL3; 1:200), anti-CD24 (M1/69; 1:400), anti-Vγ1 (2.11; 1:100), anti-Vγ4 (UC3-10A6; 1:200), anti-Vγ5 (536; 1:200) and anti-CD45RB (C363-16A; 1:400) were purchased from BioLegend and anti-CD44 (IM7; 1:400) from BD Pharmingen. Cells were washed with FACS buffer. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with 50μg/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich) and 1μg/mL ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3-4 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2 in the presence of 10μg/mL brefeldin-A (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2μM monensin (eBioscience). Cells were fixed and permeabilized with Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience/Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated for 30min at 4°C, with the following antibodies from eBioscience: anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2; 1:100), Ki67 (SolA15; 1:800), T-bet (4B10; 1:150) and RORγt (B2D; 1:100). Anti- IL-17F (9D3.1C8; 1:100 and IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1; 1:100) were purchased from Biolegend. For Annexin V staining, the Annexin V Kit (eBioscience) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The following dyes were purchased from Invitrogen and stained according to manufacturer’s instructions: Mitotracker™ Green FM, Tetramethylrhodamine Methyl Ester Perchlorate (TMRM), HCS LipidTOX™ Red Neutral Lipid Stain. Palmitate uptake was measured using 1μM Bodipy FL-C16 (Invitrogen) incubated for 10min at 37°C. Cholesterol ester uptake was measured using 2μM Bodipy CholEsteryl FL-C12 incubated for 1h at 37°C. Cholesterol content was measured using 50μg/ml Filipin III (Sigma-Aldrich) incubated for 1h at room temperature.

Flow cytometry analysis was performed with a FACS Fortessa, LSRII or Canto II using FACS Diva Software (BD Biosciences) and data analyzed using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

Seahorse Metabolic Flux Analysis

Real-time analysis of oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and extracellular-acidification rates (ECAR) of IFN-γ- and IL-17-committed γδ T cells sorted from 5-day-old B6 pups and CD27+/– γδ T cells from spleen/lymph nodes expanded in vitro were assessed using the XFp Extracellular Flux or Seahorse XFe-96 analyzers, respectively (Seahorse Bioscience). Cells were added to a Seahorse XF96 Cell Culture Microplate (Agilent), coated with Cell-Tak (Corning) to ensure adherence, and sequential measurements of ECAR and OCR were performed in XF RPMI Seahorse medium supplemented with glucose (10mM), glutamine (2mM), and sodium pyruvate (1mM) following the addition of Oligomycin A (2μM), FCCP (2μM), rotenone (1μM) plus antimycin A (1-4μM). Basal glycolysis, glycolytic capacity, basal mitochondrial respiration and maximal mitochondrial respiration were calculated. OCR and ECAR values were normalized to cell number.

SCENITH™

Cells were plated at 20 × 106 cells/ml in 96-well plates. After activation of γδ T cells, cells were treated for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2 with Control (Co), 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (DG; 100mM; Sigma-Aldrich), Oligomycin (O; 1μM; Sigma-Aldrich) or a combination of both drugs (DGO). Puromycin (Puro, 10μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) is added for 15min at 37°C. SCENITH™ kit (http://www.scenith.com) containing all reagents and protocols were developed by Dr. Rafael Argüello, (CIML). Cells were washed in cold PBS and stained with primary conjugated antibodies against different surface markers (as described above) for 15min at 4°C in FACS buffer (PBS 1X 5% FCS, 2mM EDTA). After washing with FACS buffer, cells were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm™ (BD) following manufacturer’s instructions. Intracellular staining of puromycin using the anti-Puro monoclonal antibody (1:600, Clone R4743L-E8) was performed by incubating cells during 30min at 4°C diluted in Permwash. Experimental duplicates were performed in all conditions.

In vivo glucose uptake

2-NBDG (300μg diluted in PBS 1X; Cayman chemical) was injected i.v. in C57Bl/6J mice; 15min later, cells from tumors were harvested.

Assessment of mitochondrial morphology

Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE; 100nM; Abcam) according to manufacturer protocols. Following TMRE staining, carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP; 25μM; Abcam) was used as a positive control for mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Total mitochondrial mass was assessed using MitoTracker Green (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All cells were subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry.

Triglyceride Quantification

Triglycerides (TAGs) were quantified from expanded γδ T cells in vitro using Picoprobe Triglyceride Quantification Assay Kit, Fluorometric (Abcam) and absorbance measured using FLUOstar OPTIMA (BMG Labtech).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

mRNA was prepared from FACS-sorted CD27+ and CD27– γδ T cells from WT spleen and draining lymph nodes using High Pure RNA Isolation kit (Roche). Reverse transcription was performed with random oligonucleotides (Invitrogen). Results were normalized to actin mRNA. qPCR was performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq master mix (Takara) on an ABI ViiA7 cycler (Applied Biosystems). The CT for the target gene was subtracted from the CT for the endogenous reference, and the relative amount was calculated as 2−ΔCT.

Imaging

Thymocytes from B6 E15 thymic lobes cultured for 12 days were isolated and stained for surface markers and then Mitotracker Green or TMRE (as described above). All cells were subsequently analyzed on an ImageStream™ Mark II imaging flow cytometer using INSPIRE acquisition software (Amnis); 30k events were saved from samples and 1k positive events from compensation single color controls. Analysis was performed using IDEAS® version 6.2.

For lipid droplet quantification, γδ T cells expanded in vitro were stained with LipidTOX red neutral lipid stain (Invitrogen) and Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich). Mitotracker Green FM (Invitrogen) was used to identify mitochondria. Cells were mounted onto poly-L-lysine coated slides. Images were obtained with a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope using Zen 2.3 software (Zeiss) and analyzed using ImageJ.

RNA-sequencing and data processing

Single-cell sequencing libraries were generated using the Chromium™ Single Cell 5’ Library and Gel Bead Kit (10X Genomics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data was analyzed using the R package Seurat v2.355,56.

UMI counts were normalized using regularized negative binomial regression with the sctransform package57. For downstream analysis of normalized data principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using n=50 dimensions and PCA variability was determined using an Elbow plot. Differential gene expression analysis and GSEA was performed using the MAST and fgsea packages56,57. Pathways and gene lists for gene set enrichment analysis were obtained using the misgdbr package from Molecular Signatures database (MSigDB)58,59. Adaptively-thresholded Low Rank Approximation (ALRA) from the Seurat wrappers package was performed to correct for drop-out values for visualization of leading-edge and differentially expressed genes identified by MAST60.

All downstream analysis was performed using R v.3.6.3 and RStudio Desktop 1.2.5001 on an Ubuntu 19.10 linux (64 bit) system using the following R packages and libraries: dplyr v.0.8.5, fgsea v.1.12.0, ggplot2 v.3.3.0, MAST v.1.12.0, sctransform v.0.2.1, Seurat v.3.1.4, SeuratWrappers v.0.1.0, uwot v.0.1.8 and viridis v.0.5.1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software using non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney test or, if both groups followed a normal distribution (tested by D’Agostino and Pearson normality test), using two-tailed unpaired Student t test or one-way analysis of variance. All data are presented as means ± standard error of mean (SEM) or standard deviation (SD). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****<0.0001. Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. SCENITH™ methodology for analysis of cell metabolism.

(a) Experimental design: E0771 breast or MC38 colon cancer cell lines were injected in WT mice; 6 and 15 days later, tumors were extracted for metabolic analysis of gd T cells using SCENITH™. (b) SCENITH™ assesses the impact of metabolic inhibitors on protein synthesis. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of puromycin is analysed in each condition (Co: control-no inhibition; DG: 2-deoxyglucose inhibiting glycolysis; O: oligomycin inhibiting OXPHOS; and DGO: DG+O inhibitors). Glucose dependence, fatty acid and amino acid oxidation capacity, mitochondrial dependence and glycolytic capacity are calculated as detailed in the Methods and reference #23. Error bars show mean + SEM. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (n=3 mice in triplicates per group and per experiment).

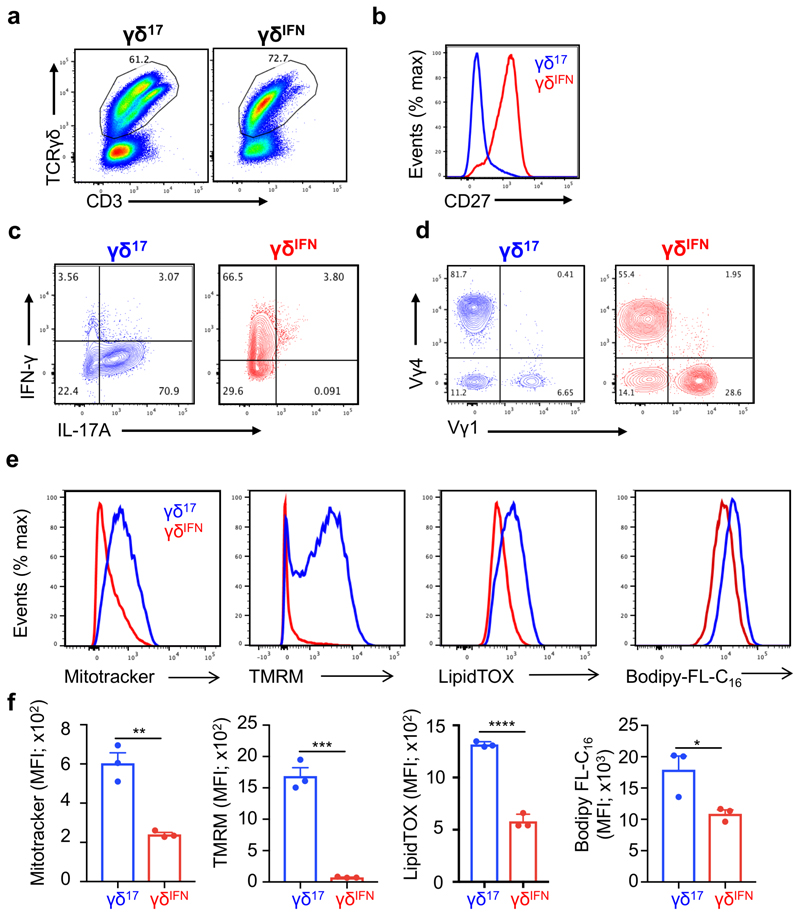

Extended Data Fig. 2. In vitro expanded γδ17 and γδIFN γδ T cells retain their mitochondrial and lipid phenotypes.

(a) Representative flow plots of CD3 and TCRγδ expression on γδ17 and γδIFN T cells expanded in vitro from total spleen/LN cells. (b) CD27 expression on in vitro expanded γδ17 and γδIFN γδ T cells. (c) IL-17 and IFNγ production by in vitro expanded γδ17 and γδIFN T cells respectively, following activation with PMA/ionomycin. (d) Vγ1 and Vγ4 expression on in vitro expanded γδ17 and γδIFN T cells. (e) Representative staining of in vitro expanded γδ17 and γδIFN T cells for mitotracker, TMRM, lipidTOX and Bodipy-FL-C16. (f) MFI of mitotracker, TMRM, lipidTOX and Bodipy-FL-C16 staining in vitro expanded γδ17 and γδIFN T cells. n=3, data representative of 3 independent experiments. Mitotracker p=0.0026; TMRM p=0.0003; LipidTOX p<0.0001; Bodipy FL-C16 p=0.036. Error bars show mean + SD, **p < 0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p < 0.0001, using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

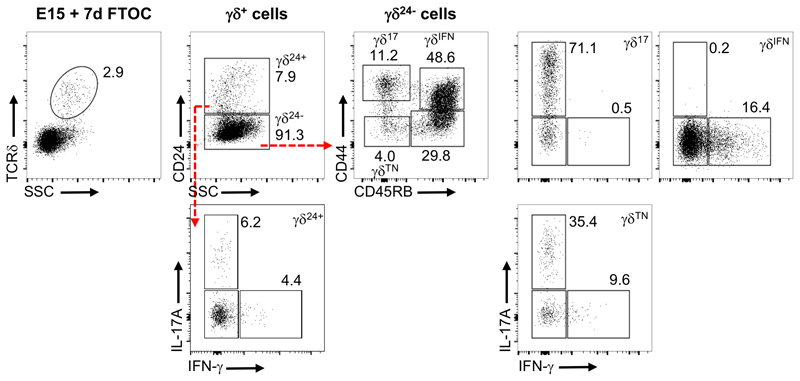

Extended Data Fig. 3. γδTN cells can generate γδ17 and γδIFN T cells.

Flow cytometry profiles of thymic γδ T cells from E15 thymic lobes that had been cultured for 7-days in fetal thymic organ culture (E15 + 7dFTOC). CD24+ (γδ24+) precursors downregulate CD24 to become a CD24-CD44-CD45RB- (γδTN) population. γδTN cells are able to become either IL-17-secreting CD44+CD45RB- γδ17 cells, or IFN-γ-producing CD44+CD45RB+ γδIFN cells.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Thymic γδ17 cells are increased upon inhibition of glucose uptake.

Flow cytometry profiles of thymic γδTN (CD44-CD45RB-), γδ17 (CD44+CD45RB-) and γδIFN (CD44+CD45RB+) cells in γδ24- cells from E15 thymic lobes in 7-day FTOC with media containing or not Fasentin. Histograms show the number of γδ17 T cells (p<0.0001) and γδ17/γδIFN ratio (p=0.0028). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (at least 4 lobes pooled per group per experiment). Error bars show mean ± SEM, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Mitochondrial activity identifies Vγ4+ progenitors with distinct effector fates at very early stages.

(a) Flow cytometry plots pre-sort, and after sorted TMRElo and TMREhi Vγ4+γδ24+ cells were cultured for 5-days on OP9DL1 cells. Percentage of thymic γδ17 and γδIFN cells generated are displayed in the graph on right. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (cells sorted from n = 4 independent mice pooled per group per experiment). (b) Flow cytometry plots for pre- and post-sort TMREhi and TMRElo Vγ4+γδTN cells that were cultured on OP9-DL1 cells for a further 5-days (plots on right). Histogram shows the percentage of each γδ T cell subset generated from cultured TMRElo and TMREhi Vγ4+γδTN cells. Error bars show mean + SD. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (at least 4 lobes pooled per group per experiment). Error bars show mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Distinct mitochondrial activities underlie effector fate of thymic γδ T cell progenitors.

(a) Experimental design for single-cell RNAseq (10x Genomics) on TMRElo and TMREhi gd24+ cells from E15 + 2d FTOC. (b) Heatmap of differentially upregulated genes from comparison of TMRElo and TMREhi gd24+ cells. Genes are grouped in relation to their function in either OxPhos or glucose metabolism.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Enriched lipid metabolism and higher lipid uptake in γδ17 cells.

(a) Experimental set up for bulk RNA-sequencing of PLZF+ (gd17) and PLZF– (gdIFN) cells isolated from PLZF-GFP (Zbtb16 GFP) mice. (b) LipidTOX MFI in γδ17 (CD27-) and γδIFN (CD27+) T cells from LN cells activated in vitro with IL-1β+IL-23 and IL-12+IL-18 respectively. n=9, data pooled from 3 independent experiments. (c) Representative plots of LipidTOX staining and IL-17A, IL-17F or RORγt expression in γδ27- T cells from LNs activated in vitro with IL-1β+IL-23 for 6h. Data representative of 3 independent experiments. (d) Bodipy-FL-C16 MFI in γδ17 (CD27-) and γδIFN (CD27+) T cells T cells unstimulated or stimulated in vitro with IL-12+IL-18 or IL-1β+IL-23.(n=3, data from 1 experiment; γδ17 p= 0.0044; γδIFN p=0.8035). Error bars show mean + SD, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 using one-way ANOVA.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Inhibition of dietary fat uptake reduces tumour growth and γδ17 cells in the tumour.

B16F10-tumour bearing mice were given daily injections of either vehicle or orlistat on days 6-9, and tumours were analysed on day 10. (a) Percentage body weight following tumor cell injection; arrows indicate when orlistat or vehicle were administered. (b) Tumor volume on days 8-10 following B16F10 inoculation. Absolute numbers (c) and LipidTOX staining (d) of tumor-infiltrating γδ17 cells on day 10. n=8 biologically independent animals, data from 1 independent experiment. Data represents mean + SD, *p<0.06, **p < 0.01 using unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Glucose supplementation diminishes γδ17 cell numbers and proliferation.

(a) Flow cytometry profiles of peripheral γδ17 T cells cultured with media containing low (5mM) or high (50mM) doses of glucose. Graph depicts total numbers of γδ17 T cells (p=0.0028). (b) Number of proliferating Ki-67+ γδ17 T cells cultured with low or high glucose (p=0.0034). n=6 biologically independent animals, data from 2 independent experiments. Error bars show mean ± SEM, **p < 0.01, using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the valuable assistance of the staff of the flow cytometry, bioimaging and animal facilities at our Institutions. We thank J.-W. Taanman, A. Magalhães, J. Ribot, K. Serre, and N. Sousa for technical suggestions and administrative help. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (092973/Z/10/Z to D.J.P.), Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) UK (BB/R017808/1 to D.J.P.), European Research Council (CoG_646701 to B.S.-S.; StG_679173 to L.L.), Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) (16/FRL/3865 to L.L), NIH (NS115064, HG008155, AG062377 to M.K), R01 AI134861, Astrazeneca (Prémio FAZ Ciência 2019 to B.S.-S. and N.L.) and PAC-PRECISE LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-016394, co-funded by FEDER (POR Lisboa 2020) and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portugal). N.L is supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from EMBO (ALTF 752-2018); S.M. was supported by a studentship from the Medical Research Council (MRC) UK; G.F. is supported by a European Commission Marie Sklodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (ref. 752932); and A.D, S.C. L.D and H.P are supported by Irish Research Council fellowships.

Footnotes

Author contributions

N.L, C.M, S.M and M.R performed most of the experiments and analyzed the data. G.J.F. designed and performed some experiments. N.S., A.C.K., L.D., H.K., A.D., S.C., H.P. R.L. and C.C. provided technical assistance in some experiments. M.K. and L.A performed bioinformatic analysis and M.B provided reagents, materials and support. P.P. and R.J.A. provided key assistance with the SCENITH™ methodology. B.S.-S., D.J.P and L.L conceived and supervised the study. N.L, C.M., B.S.-S., D.J.P. and L.L. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

B.S.-S. is an inventor of the patented “Delta One T cell” technology, which has been acquired by GammaDelta Therapeutics (London, UK).

Data Availability

The GEO public repository accession codes are; GSE150585 for single-cell RNA sequencing; and GSE156782 for bulk RNA sequencing. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1.Buck MD, Sowell RT, Kaech SM, Pearce EL. Metabolic Instruction of Immunity. Cell. 2017;169:570–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida L, Lochner M, Berod L, Sparwasser T. Metabolic pathways in T cell activation and lineage differentiation. Semin Immunol. 2016;28:514–524. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geltink RIK, Kyle RL, Pearce EL. Unraveling the Complex Interplay Between T Cell Metabolism and Function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36:488–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cham CM, Driessens G, O’Keefe JP, Gajewski TF. Glucose deprivation inhibits multiple key gene expression events and effector functions in CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2450–2450. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang CH, et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153:1251–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CH, et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell. 2015;162:1241–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Sullivan D, Sanin DE, Pearce EJ, Pearce EL. Metabolic interventions in the immune response to cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:335–335. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva-Santos B, Mensurado S, Coffelt SB. gammadelta T cells: pleiotropic immune effectors with therapeutic potential in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:404–404. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]