Abstract

Background

The association between the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF) and objective measures of physical activity has never been evaluated in participants with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder (BD). Our aim was to compare IPAQ-SF to objective measures in participants with newly diagnosed BD, their unaffected first-degree relatives (UR), and healthy control individuals (HC) in groups combined and stratified by group.

Materials and methods

Physical activity measurements was collected on 20 participants with newly diagnosed BD, 20 of their UR, and 20 HC using individually calibrated combined acceleration and heart rate sensing (Actiheart) for seven days. IPAQ-SF was self-completed at baseline. Correlation between measurements from the two methods was examined with Spearman rank correlation coefficient and agreement levels examined with modified Bland-Altman plots.

Results

Physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE) from IPAQ-SF was weakly but significantly positively correlated with physical activity estimates measured using acceleration and heart rate in groups combined (Actiheart PAEE) (ρ= 0.301, p= 0.02). Correlations for each group were positive, but only in UR were it statistically significant (BD: p = 0.18, UR: p = 0.007, HC: p = 0.84). Self-reported PAEE and moderate-intensity were markedly underestimated (PAEE in all participants combined: 62.7 (Actiheart) vs. 24.3 kJ/day/kg (IPAQ-SF), p< 0.001), while vigorous-intensity was overestimated. Bland-Altman plots indicated proportional bias.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the use of the IPAQ-SF to monitor levels of physical activity in participants with newly diagnosed BD, in a psychiatric clinical setting, should be used with caution and consideration.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, physical activity, IPAQ, physical activity energy expenditure, unaffected relatives

1. Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by alterations in mood and activity with recurrent episodes of depression, (hypo)mania and remission (1). BD is associated with an increased prevalence of obesity (2), and persons with BD are known to have approximately 10 years reduced life-expectancy (3,4), mainly due to cardiovascular diseases (5,6). Reduced psychomotor activity has long been known to present in BD during euthymia and depressive states, while increased psychomotor activity is seen during manic states (1,7–13). About half of the persons diagnosed with BD has been shown to also suffer from anxiety or agitation symptoms (14), and physical activity has shown to decrease anxiety and depressive symptoms in persons with BD (15). Monitoring physical activity is therefore important in evaluating the course of illness as well as the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions aimed to improve physical activity and overall prognosis for persons with BD (16).

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ, (17)) is a questionnaire where participants self-report their amount of physical activity in four intensities (vigorous-intensity, moderate-intensity, walking, and sitting) during the past seven days. The questionnaire is a general surveillance tool but has also been used to assess physical activity in mental health care settings (18). IPAQ has two versions: a short 9-items form (IPAQ-SF) and a long 31-items form. A self-reported questionnaire is easier, cheaper, and quicker than objective measures to monitor physical activity (19), making it more attractive to use in a clinical setting. However, it is important that convenience does not come at the cost of accuracy and so, our purpose for this study was to explore whether the self-reported questionnaire is relevant to use in larger samples of the three groups by evaluating the association between the questionnaire and objective measures. A systematic review investigated the validity of IPAQ-SF in different populations compared with an objective measure of activity behavior (accelerometer or pedometer), concluding that self-reported levels of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity tends to be overestimated by 36-173 % (20). The validity of the Danish translation of IPAQ has only been investigated in an internet-based long version showing modest validity (21). Further, newer studies have found the IPAQ-SF to not be a valid method in different populations such as pregnant women, young people with cerebral palsy, and 15 year old South Africans (22–25), as well as the questionnaire being user-unfriendly and difficult for participants to accurately understand the division in levels of physical activity (i.e. vigorous and moderate) (26). However, the test-retest reliability of IPAQ-SF has consistently been shown to be high (17,20). Only one previous study compared IPAQ with an objective measure in participants with BD, finding a statistically significant correlation in physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE) between IPAQ and Sensewear (a combined acceleration, temperature and galvanic skin response sensor) (18). Combined acceleration and heart rate monitoring (Actiheart) used as the objective measure of physical activity, has previously been used to measure the level of physical activity in participants with BD and unipolar disorder by our group (27,28). The combined acceleration and heart rate monitor has been chosen for this study, as it also has the ability to measure heart rate variability, which could help identify the severity of disease burden in participants with BD (29), making the sensor all the more relevant to use in the clinical setting.

The objective of this paper was to evaluate the association between self-reported physical activity measured using IPAQ-SF and objective measures of physical activity measured with a combined accelerometer and heart rate sensor in participants with newly diagnosed BD, their unaffected first-degree relatives (UR), and healthy control individuals (HC). This is a sub-study, which is part of the larger Bipolar Illness Onset Study (BIO) cohort study (30), and the protocol and statistical analyses were decided prior to commencement. The three groups were included to evaluate whether the participants with newly diagnosed BD evaluate their own levels of physical activity differently than the healthy control individuals, and likewise if the unaffected relatives, who have a genetic predisposition to the illness, would respond as an intermediary group. Therefore, the analyses were conducted both with all groups combined and stratified by group to investigate whether associations would be different between groups.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and setting

The present cross-sectional study included participants already recruited in The Bipolar Illness Onset study (BIO, for further description see (30)). The recruitment for the present study was done from February 2019 until June 2019 at the Copenhagen Affective Disorder research Centre (CADIC), Psychiatric Centre Copenhagen, Denmark.

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Participants with newly diagnosed BD

The participants were referred from the Copenhagen Affective Disorder Clinic. The clinic covers the entire Capital Region of Denmark with a catchment area of 1.6 million people and all psychiatric centers in the region (30). Inclusion criteria for the present sub-study were being newly diagnosed with BD according to ICD-10 (31) and age between 18-55 years. The term newly diagnosed refers to newly diagnosed/first-episode participants with bipolar disorder, that is, onset of first manic or hypomanic episode or when the diagnosis of BD is made for the first time (30). Exclusion criterion was having an organic BD diagnosis secondary to brain injury. Participants were asked not change medication during the seven days study period.

2.2.2. Unaffected first-degree relatives

Unaffected first-degree relative (UR) were asked to participate in the BIO-study after gaining consent from the participant with newly diagnosed BD. Inclusion criteria were being a sibling or child of a participant with newly diagnosed BD already included in the BIO-study and age between 15-40 years. Exclusion criteria were having any ICD-10 diagnosis below F34. UR participants were matched on gender and age to the participants with newly diagnosed BD.

2.2.3. Healthy control individuals

The healthy control individuals (HC) were recruited from voluntary blood donors at the Blood Bank at Rigshospitalet, Denmark and matched on gender and age to the participants with newly diagnosed BD. Exclusion criteria were personally or a first-degree relative having a history of psychiatric illness which required medical treatment.

2.3. Clinical assessments

Before being referred to the BIO-study, the participants with newly diagnosed BD were diagnosed with a BD diagnosis by a specialist in psychiatry at the Copenhagen Affective Disorder Clinic according to the ICD-10 (31). As part of the clinics initial diagnostic assessment, they were further categorized into BD type I or type II according to DSM-5 (32). Before signing the informed consent form for the BIO study, the diagnoses of the participants with newly diagnosed BD were validated by medical or psychology Ph.D. students using the Scale for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry interview (SCAN) (33).

At baseline, background characteristics were collected. This included, but was not limited to, years of education, current occupation, current medication and medical history. The severity of depressive and manic symptoms for each participant was rated using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 17-item (HDRS-17 (34)) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS (35)). A clinical diagnosis on current affective state was given according to ICD-10. Information on weight (kg), height (m), pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory frequency was collected for each participant.

2.4. Self-reported physical activity assessment (IPAQ-SF)

The participants’ level of physical activity was self-reported using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form at baseline (IPAQ-SF (17)). This questionnaire was chosen as it has become the most widely used questionnaire for physical activity (36) both in clinical settings and research after the reliability and validity of the IPAQ was conducted across 12 countries by The International Consensus Group on Physical Activity Measurement in 2003 (17).

Values from the 9-item questionnaire were summarized into three intensity levels of activity (vigorous-intensity, moderate-intensity and walking) during the last seven days. As suggested by the IPAQ data processing guide, time spent in each intensity category exceeding 180 minutes where truncated to 180 minutes for the given intensity (37). From these, a weighted estimate of PAEE per week (MET·min·wk-1) was calculated from all reported intensities by multiplying the MET-value for each intensity (walking: 3.3 METs, moderate: 4 METs, and vigorous: 8 METs) subtracted by one MET to account for resting metabolic rate (RMR) (17). The PAEE was converted using the conversion factor 1 MET = 71 J·min·kg1 and thereafter converted to the unit kJ·day-1·kg-1. Time spent in each intensity (i.e. vigorous, moderate, and walking) was calculated in h·day-1. Participants with missing data were included in the analyses as follows. If data were missing on both frequency (days) and duration (minutes) for a given intensity category, the sum was set at zero. If data were missing solely on frequency or duration, the missing value was assigned the mean value of the group (BD, UR, HC) for the given item.

2.5. Objectively measured physical activity assessment

A wearable device for measuring acceleration and heart rate was used as an objective measure of physical activity (Actiheart, Cambridge Neurotechnology Ltd, Papworth, UK), technical validation and reliability of which have been reported elsewhere (38). The monitor was placed on the participants’ thorax below the apex of the sternum with the wire in a horizontal line to the left. It was connected to the skin using Skintakt T-60 electrodes with micropores for long-term monitoring. The skin was prepared by using disinfecting wipes made for skin with 82 % ethanol, 2 % glycerol, and 0.5 % chlorhexidine.

An eight-minute step test followed by a two-minute rest period was conducted. This was used for individual calibration of heart rate to energy expenditure (39). The method of estimating PAEE from the combination of heart rate and movement data collected by the device has been validated against indirect calorimetry and stable isotopes (40–42). Heart rate and acceleration data was collected in 30 seconds epoch resolution. Participants were asked to remove the monitor when showering or swimming, and to change electrodes daily. Data was collected for seven days, but records were included if containing a minimum of three days of valid data. When participants returned the monitor, the data quality was assessed. If data was not sufficient, due to too low quantity or quality, participants were asked to repeat the long-term monitoring for another seven days. Time spent at different intensities were summarized into time spent in light-intensity (1.5-3 METs), moderate-intensity (3-6 METs), and vigorous-intensity (> 6 METs).

2.6. Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were defined á priori. Descriptive statistics were calculated using mean (standard deviation (SD)). Differences in categorical data were analyzed with chi-square test, while differences in continuous data were analyzed with t-test and one-way analysis of variance.

The correlation between the self-reported and objectively measured estimates of physical activity was examined by the nonparametric Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ). The level of agreement was then examined with modified Bland-Altman plots, where the difference between the objectively measured estimates and the self-reported were plotted against objective estimates. The horizontal lines on the graphs indicate the mean difference and the limits of agreement (i.e. 1.96 +/-SD). Background data was collected in Excel sheets, and SPSS version 25 was used for all analyses. P-values (two-sided) below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.7. Ethical considerations

The BIO-study was approved by the Committee on Health Research Ethics of the Capital region of Denmark (protocol No. H-7-2014-007) and the Danish Data Protection Agency, Capital Region of Copenhagen (RHP-2015-023). The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki principles (Seoul, October 2008). All participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

3. Results

3.1. Background characteristics

A total of 28 participants with newly diagnosed BD, 27 UR, and 26 HC already included in the BIO-study, were invited to participate in the present study. Of these, seven participants with newly diagnosed BD, seven UR, and four HC declined the invitation. Of the consenting participants, one participant with newly diagnosed BD and two HC were excluded, as they met exclusion criteria or had an allergic reaction to the electrodes during the seven days long-term measurements before our minimum requirements were met. Thus, a total of 20 participants with newly diagnosed BD, 20 UR, and 20 HC were included in the present study and provided data on physical activity. Of the included participants, two participants with newly diagnosed BD had one of their own UR included, and two UR had another UR in their family included in the study. Five participants with newly diagnosed BD had a diagnosis of BD type I, while the remaining 15 had a diagnosis of BD type II. Of the participants with newly diagnosed BD, the mean (SD) illness duration of a diagnosis of BD was 1.5 (1.4) years and their current affective states were distributed between 15 participants in euthymic state, 1 participant in hypomanic state, two participants in mild to moderate depressive state, and two participants in mixed state. Background characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean (SD) age of the three groups were BD: 29.9 (7.8), UR 27.5 (6.3) and HC: 31.8 (8.6). Except for the HDRS-17 (p < 0.05), the YMRS (p < 0.05), and years of education (p < 0.05), there were no statistically significant differences in background information between the three groups.

Table 1.

Background characteristics for all participants combined, participants with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder (BD), their unaffected first-degree relatives (UR), and healthy control individuals (HC).

| Combined (n=60)a | BD (n= 20)a | UR (n= 20)a | HC (n= 20)a | p-valuesb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.7 (7.7) | 29.9 (7.8) | 27.5 (6.3) | 31.8 (8.6) | 0.2 |

| Sex (% female) | 33 (55) | 10 (50) | 12 (60) | 11 (55) | 0.8 |

| Years of educationc | 6.1 (2.3) | 4.8 (2.8) | 5.9 (1.7) | 7.6 (1.3) | <0.05 |

| HDRS-17d | 3.9 (4.6) | 8.4 (5.2) | 1.9 (2.5) | 1.5 (1.6) | <0.05 |

| YMRSe | 2.1 (3.8) | 5.3 (5.0) | 0.75 (1.0) | 0.1 (0.3) | <0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 (4.8) | 26.2 (5.8) | 24.3 (3.5) | 25.8 (4.9) | 0.5 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.1 (15.6) | 78.6 (16.8) | 71.9 (11.7) | 80.9 (16.9) | 0.2 |

| Height (cm) | 174.0 (8.6) | 173.4 (9.4) | 171.8 (9.3) | 176.9 (6.5) | 0.2 |

Data are mean (SD) or proportions n (%) unless otherwise stated

p-values represent difference in mean or proportion between the three groups

Total years of finished education after primary school

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score 17-items

Young Mania Rating Scale score

3.2. Raw and unadjusted physical activity estimates

As presented in the top of Table 2, the mean raw estimates of objectively measured PAEE for all groups combined was 62.7 kJ/day/kg (SD 24.2), while the mean self-reported IPAQ-SF PAEE (sum of PAEE for walking, moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity, but excluding light-intensity activity) for all groups was 24.3 kJ/day/kg (SD 19.0), which was statistically significantly different (p < 0.001). Thus, self-reported PAEE scores were under half (39 %) of the objectively measured PAEE. Further details concerning raw physical activity estimates from IPAQ-SF and objective measures for all study participants pooled and divided in the three groups are presented in Table 2. As can be seen, self-reported and objectively measured time spent in vigorous-intensity activity (> 6 METs) were neither statistically significantly different in all three groups, nor when all participants were combined (combined: p= 0.07). Self-reported and objectively measured time spent in moderate-intensity activity (3-6 METs) were statistically significantly different in all groups combined and in participants with newly diagnosed BD, UR, and HC, with self-reported moderate-intensity activity being estimated markedly lower than the objectively measured moderate-intensity activity (Combined: 2.24 (SD 1.01) h·day-1 (Acc + HR) vs. 0.57 (SD 0.39) h·day- 1 (IPAQ-SF), p< 0.001). Light-intensity activity (1.5-3 METs) accounted for 67 % of total time spent in the three intensities light, moderate and vigorous (Mean: 5.16 (SD 1.53) h·day-1).

Table 2.

Comparison of raw and unadjusted physical activity estimates obtained by acceleration and heart rate sensor (Acc + HR) and IPAQ-SF for all participants combined, participants with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder (BD), their unaffected first-degree relatives (UR), and healthy control individuals (HC)

| Total Physical Activity Energy Expenditure | Vigorous physical activity (> 6 METs) | Moderate physical activity (3-6 METs) | Light physical activity (1.5-3 METs) | Walking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kJ · day-1 · kg-1 | p-valuec | h · day-1 | p-valuec | h · day-1 | p-valuec | h · day-1 | h · day-1 | |

| Combined BD, UR, HC (n = 60) | ||||||||

| Acc + HR (mean (SD))a | 62.7 (24.2) | < 0.001 | 0.28 (0.24) | 0.07 | 2.24 (1.01) | < 0.001 | 5.16 (1.53) | - |

| IPAQ-SF (mean (SD))b | 24.3 (19.0) | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.57 (0.39) | - | 0.65 (0.65) | |||

| BD (n = 20) | ||||||||

| Acc + HR (mean (SD))a | 59.8 (33.0) | 0.001 | 0.26 (0.30) | 0.14 | 2.13 (1.30) | < 0.001 | 4.70 (1.18) | - |

| IPAQ-SF (mean (SD))b | 27.0 (22.4) | 0.47 (0.57) | 0.48 (0.45) | - | 0.59 (0.56) | |||

| UR (n = 20) | ||||||||

| Acc + HR (mean (SD))a | 66.1 (20.0) | < 0.001 | 0.24 (0.17) | 0.11 | 2.30 (1.03) | < 0.001 | 5.61 (1.80) | - |

| IPAQ-SF (mean (SD))b | 26.3 (18.9) | 0.43 (0.52) | 0.60 (0.38) | - | 0.81 (0.68) | |||

| HC (n = 20) | ||||||||

| Acc + HR (mean (SD))a | 62.1 (17.4) | < 0.001 | 0.34 (0.21) | 0.74 | 2.31 (0.68) | < 0.001 | 5.17 (1.50) | - |

| IPAQ-SF (mean (SD))b | 19.8 (15.1) | 0.31 (0.37) | 0.63 (0.33) | - | 0.56 (0.71) | |||

Combined acceleration and heart rate sensor

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form

p-values representing differences in mean (SD) estimates between the two methods for measuring physical activity

3.3. Correlations and levels of agreement between self-reported physical activity and objectively measured physical activity

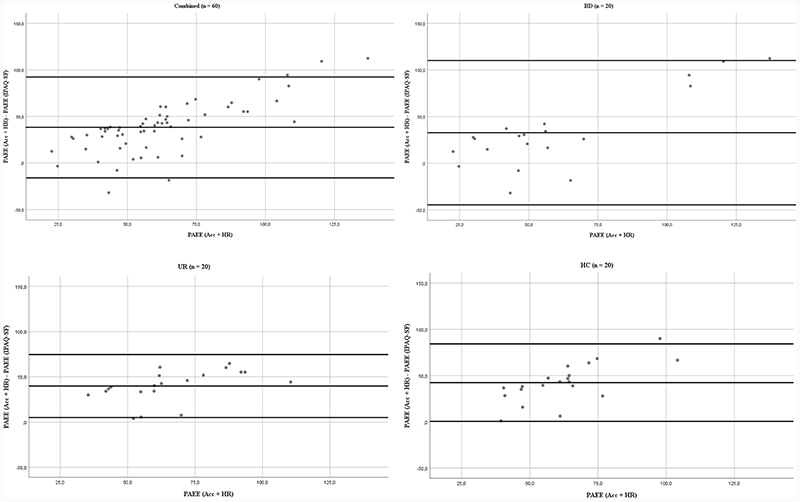

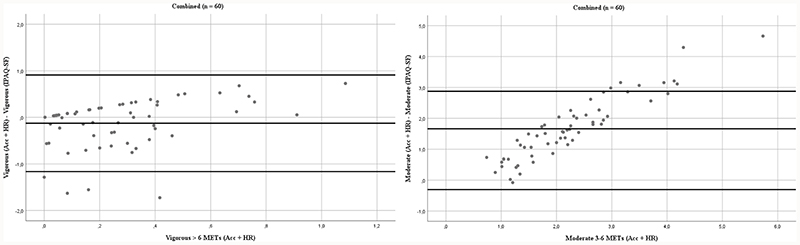

PAEE from IPAQ-SF were statistically significantly correlated with the objectively measured PAEE when all participants were combined (ρ = 0.301, p = 0.02). All Spearman rank correlation coefficients between IPAQ-SF estimates and the objectively measured estimates are displayed in Table 3. Correlation of PAEE in UR was likewise statistically significant (ρ = 0.585, p = 0.007). Modified Bland-Altman plots displaying the difference between the objectively measured PAEE and IPAQ-SF PAEE plotted against the objectively measured PAEE are shown in Figure 1 for groups combined and individually. The plots indicate heteroscedasticity as the difference increases when objective measure increases. In Figure 2 corresponding plots are portraited with time spent in moderate-intensity activity (3-6 METs) and vigorous-intensity activity (> 6 METs) for all participants combined (n = 60), similarly indicating proportional bias in both.

Table 3.

Spearmann correlation coefficients (ρ) between self-reported physical activity estimates using the IPAQ-SF and objective measurements (acceleration and heart rate sensor) for all participants combined, participants with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder (BD), their unaffected first-degree relatives (UR) and healthy control individuals (HC).

| Total PAEEa | Vigorous (> 6 METs) | Moderate (3-6 METs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | p-values | ρ | p-values | ρ | p-values | |

| Combined (n = 60) | 0.301 | 0.02 | 0.197 | 0.13 | 0.147 | 0.26 |

| BD (n = 20) | 0.314 | 0.18 | 0.203 | 0.39 | -0.051 | 0.83 |

| UR (n = 20) | 0.585 | 0.007 | 0.319 | 0.17 | 0.376 | 0.10 |

| HC (n = 20) | 0.048 | 0.84 | 0.096 | 0.69 | 0.050 | 0.84 |

Physical activity energy expenditure.

Figure 1.

Modified Bland-Altman plots of difference in objectively measured PAEE (acceleration and heart rate, kJ day-1 kg-1) and self-reported PAEE estimates using IPAQ-SF (kJ day-1 kg-1) plotted against the objectively measured PAEE in all participants combined (n = 60), participants with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder (BD, n = 20), their unaffected first-degree relatives (UR, n = 20) and healthy control individuals (HC, n = 20). Lines represent mean in difference and the limits of agreement i.e. +/- 1,96 SD.

Figure 2.

Modified Bland-Altman plots of difference in objectively measured (acceleration and heart rate, h day-1) moderate-intensity activity (3-6 METs) or vigorous-intensity activity (> 6 METs) and self-reported moderate-intensity activity (3-6 METs) or vigorous-intensity activity (> 6 METs) estimates from IPAQ-SF (h day-1) plotted against the objectively measurements in all participants combined (n = 60). Lines represent mean in difference and the limits of agreement i.e. +/- 1,96 SD.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the association between self-reported physical activity measured using the IPAQ-SF and objective measures of physical activity measured using an accelerometer and heart rate monitoring device with individual calibration. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the association between the IPAQ-SF and objective measures of physical activity in participants with newly diagnosed BD, their unaffected relatives, and healthy control individuals. Total PAEE was statistically significantly correlated between methods of measurement with all participants pooled, though the objectively measured value of PAEE was more than twice as high as the estimate from the IPAQ-SF. Moderate-intensity activity (3-6 METs) were markedly underestimated in the IPAQ-SF compared to the objective measured for all groups, while vigorous-intensity activity (> 6 METs) was overestimated by all groups but HC. Correlations for both measures were statistically non-significant for all groups combined and individually. It has been suggested that the correlation between objectively assessed energy expenditure and total self-reported estimates must be ρ ≧ 0.5 to be acceptable for self-reported questionnaires (36). Only the PAEE for UR met this requirement. Bland-Altman plots indicated heteroskedasticity i.e. proportional bias in PAEE for all participants, which suggest that the IPAQ-SF might not be sufficiently accurate in the individual assessment of physical activity.

The underestimations found in total PAEE and moderate-intensity activity are likely influenced by different factors. The IPAQ-SF collects estimates of walking, moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activity, which leaves out light-intensity activities. In contrast, all intensities are assessed by the accelerometer and heart rate sensor. This explains much of the difference in total PAEE between the two measuring methods, since light-intensity activity contribute over half of the total PAEE in a western population (43). Our findings in this study support this with light-intensity activity accounting for 67 % of total time spent in the three intensities light, moderate and vigorous when all groups are combined. Secondly, the IPAQ-SF includes a possible answer when quantifying the different levels of physical activity as “Don’t know/not sure” and choosing this option will summarize as zero activity for the category in question. Participants may be compelled to use this option, thereby creating missing data and underestimated values (13 participants with newly diagnosed BD, 6 UR and 9 HC answered “Don’t know/not sure” in at least one category). Thirdly, the IPAQ-SF instructs participants to only include activities performed in ten minute bouts or longer, which could leave out burst of activity collected by the sensor increasing the difference in total PAEE (44). While PAEE and moderate-intensity activity were underestimated in IPAQ-SF, vigorous-intensity activity was overestimated by 80 % in BD and UR, respectively, while HC merely underestimated this with 9 %. It has previously been suggested that the participants with newly diagnosed BD’s decreased physical fitness and lower amount of physical activity might be a reason for their overestimations, making them evaluate physical activity as more demanding than it is, thereby evaluating moderate-intensity activity as vigorous-intensity (18). However, the participants with newly diagnosed BD in this study did not have a significantly lower level of total PAEE compared to HC (p = 0.79).

Our findings are in contrast to results from a systematic review investigating the validity of the IPAQ-SF (20), concluding that in the majority of the included studies, IPAQ-SF scores were 36-173 % overestimated compared to objective measures. However, the authors also found that correlations between self-reported levels of physical activity and objective measures were lower than the acceptable standard (as described in Terwee et al.’s guideline (45)). Most of the included studies investigated the validity of the questionnaire in the general population, while some investigated in specific populations such as participants with fibromyalgia (46) or schizophrenia (47). None, however, investigated the validity of IPAQ-SF in participants with BD.

One previous study compared IPAQ with objective measures (combined acceleration, temperature and galvanic skin response sensor) in participants with BD finding a statistically significant correlation (however under the suggested minimal acceptance level (36)) in PAEE obtained with IPAQ and the objective measure (18). There are differences between this study and ours. While we investigated the IPAQ-SF, Vancampfort et al. investigated the long 31-items version of IPAQ. Further, we instigated the correlation solely in the subgroup of participants with BD who were newly diagnosed, and more so in their unaffected relatives and healthy control individuals. This was done as this sub-study is part of a larger cohort study (the BIO study (30)). By comparing measurements from the participants with newly diagnosed BD with those from healthy control individuals and their genetically predisposed unaffected relatives, possible over- or underestimations of physical activity could be directly compared between the participants with newly diagnosed BD and the control groups, making it easier to possible adapt the protocol for IPAQ-SF in the future for a psychiatric clinical setting for more precise estimates. Despite the differences between Vancampfort et al.’s study and ours, our findings when regarding participants with BD do coincide.

These results imply that self-reported physical activity using the IPAQ-SF should be used carefully in a clinical setting. However, the original aim of the questionnaire was to collect self-reported measures of physical activity suitable for assessing population levels of physical activity across multiple countries (17), and therefore not to be used as a clinical tool. Satisfactory self-reported physical activity will always be hard to obtain as physical activity is complex behavior and self-reporting is influenced by recall bias. As accelerometer and heart rate monitors become increasingly easier and cheaper to use, this might be a better method for collecting reliable information on participants’ physical activity and developments thereof in the clinical setting as well as in larger studies.

4.1. Limitations

Firstly, the present study included a relatively small sample size (60 participants combined, 20 in each group), and due to the small number of participants, the results should be interpreted with caution. It is possible that a larger sample could have resulted in other findings as the power of the study would increase. A larger sample with repeated measurements might possibly have resulted in other findings. Therefore, this subject must be investigated further in complementary studies. Secondly, the data on self-reported physical activity were collected retrospectively regarding the past seven days at baseline. Objective data were then collected prospectively for the following seven days. Therefore, the data is not collected within the same timeframe. We do however consider the data to be comparable for the purpose of the present study as both instruments are used to estimate latent habitual levels of activity. Further, had the IPAQ-SF been self-reported after wearing the acceleration and heart rate sensor for a week, the participants awareness of their level of physical activity might have been affected, likewise creating a limitation to the study. Thirdly, we investigated participants with newly diagnosed BD, as the study is a part of the larger BIO-study (30). At this point in time, there is a lack of evidence regarding the representativeness of this sample to people with BD as a whole. It is therefore a possibility, that the sample is not representative of this population but merely people with newly diagnosed BD. Fourthly, the HC included in this study were recruited from volunteer blood donors, which may result in a super healthy control group. Indeed, the activity level of this group did appear to be higher than observed for other healthy controls of similar age sampled from the general population (43), though it was not statistically significantly different from the participants with newly diagnosed BD. However, this volunteering group was matched on age and sex, and it was recruited from the same catchment area as the participants with newly diagnosed BD which makes it a control group, when considering the common challenges of identifying an appropriate control group (48).

5. Conclusion

In the present study, self-reported total PAEE using the IPAQ-SF was statistically significantly correlated with objectively measured PAEE using an acceleration and heart rate monitor with all participants included. However, the correlation was weak and not significant in all subgroups, including the participants with newly diagnosed BD. Bland-Altman plots indicated large proportional bias and wide limits of agreement, suggesting that the questionnaire has low accuracy for individual assessment. These results suggest that the use of the IPAQ-SF as a tool to monitor levels of physical activity in participants with newly diagnosed BD in a psychiatric clinical setting should be used with caution. However, due to the small number of participants included in the study, interpretations of the findings should be done with caution.

Acknowledgments

We are so very thankful to all the participants for volunteering their time to our project. We would additionally like to thank the Mental Health Services, Capital Region of Denmark, The Danish Council for Independent Research, Medical Sciences (DFF-4183-00570), Weimans Fund, Markedsmodningsfonden (the Market Development Fund 2015-310), Gangstedfonden (A29594), Helsefonden (16-B-0063), Innovation Fund Denmark (the Innovation Fund, Denmark, 5164-00001B), Copenhagen Center for Health Technology (CACHET), EU H2020 ITN (EU project 722561), Augustinusfonden (16-0083), Lundbeck Foundation (R215- 2015-4121) for their grants to the BIO-study. The work of SB was supported by the Medical Research Council (grant number MC_UU_12015/3 and the National Institute of Health Research Cambridge (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (grant number IS-BRC-1215-20014).

Role of funding source

The BIO-study, of which this is a sub-study, is funded by grants from the Mental Health Services, Capital Region of Denmark, The Danish Council for Independent Research, Medical Sciences (DFF-4183-00570), Weimans Fund, Markedsmodningsfonden (the Market Development Fund 2015-310), Gangstedfonden (A29594), Helsefonden (16-B-0063), Innovation Fund Denmark (the Innovation Fund, Denmark, 5164-00001B), Copenhagen Center for Health Technology (CACHET), EU H2020 ITN (EU project 722561), Augustinusfonden (16-0083), Lundbeck Foundation (R215-2015-4121).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interests

JF, SB and MFJ declare no conflicts of interest. LVK has within recent three years been a consultant for Lundbeck.

Author Statement

All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript being submitted. This manuscript presents original material, has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Contributors

MFJ and LVK have designed the study. MFJ has drafted the study protocol and supervised the project. JF has collected the data, conducted the statistical analyses and written the original draft of the manuscript. SB, LVK and MFJ have reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Goodwin F, Jamison K. Manic-Depressive illnes. New Oxford Univ Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein B, Liu SM, Zivkovic N, Schaffer A, Chien LC, Blanco C. The burden of obesity among adults with bipolar disorder in the United States. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:387–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessing LV, Vradi E, Andersen PK. Life expectancy in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(5):543–8. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessing LV, Vradi E, McIntyre RS, Andersen PK. Causes of decreased life expectancy over the life span in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015 Jul 15;180:142–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):101–4. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.008. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bent-Ennakhil N, Cécile Périer M, Sobocki P, Gothefors D, Johansson G, Milea D, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular diseases and type-2-diabetes mellitus in patients with psychiatric disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):455–61. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2018.1463392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beigel A, Murphy DL. Unipolar and bipolar affective illness. Differences in clinical characteristics accompanying depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;24(3):215. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1971.01750090021003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupfer D, Weiss B, Foster FG, Detre T, McPartland R, Delgado J. Psychomotor activity in affective states. J Psychiatr Res. 1974;30:765–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760120029005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhs H, Reschke D. Psychomotor activity in unipolar and bipolar depressive patients. Psychopathology. 1992;25:109–16. doi: 10.1159/000284760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobin C, Sackeim H. Psychomotor symptoms of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:4–17. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg J, Perlis R, Bowden C, Thase M, Miklowitz D, Marangell L, et al. Manic symptoms during depressive episodes in 1,380 patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:173–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell P, Frankland A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Roberts G, Corry J, Wright A, et al. Comparison of depressive episodes in bipolar disorder and in major depressive disorder within bipolar disorder pedigrees. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:303–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.088823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judd L, Schettler P, Akiskal H, Coryell W, Fawcett J, Fiedorowicz J, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of subdromal manic symptoms, including irritability and psychomotor agitation, during bipolar major depressive episodes. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:440–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serafini G, Geoffroy PA, Aguglia A, Adavastro G, Canepa G, Pompili M, et al. Irritable temperament and lifetime psychotic symptoms as predictors of anxiety symptoms in bipolar disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(1):63–71. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2017.1385851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashdown-Franks G, Sabiston CM, Stubbs B. The evidence for physical activity in the management of major mental illnesses: A concise overview to inform busy clinicians’ practice and guide policy. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(5):375–80. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soundy A, Taylor A, Faulkner G, Rowlands A. Psychometric Properties of the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall Questionnaire in Individuals with Severe Mental Illness. 2007;21(6):309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig CL, Bauman AE, Marshall AL, Sjo M, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire : 12-Country Reliability and Validity. 2003:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vancampfort D, Wyckaert S, Sienaert P, Herdt A De, Hert M De, Rosenbaum S, et al. Concurrent validity of the international physical activity questionnaire in outpatients with bipolar disorder: Comparison with the Sensewear Armband. Psychiatry Res. 2016;237:122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.064. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Ward PB, Teasdale S, Rosenbaum S. Integrating physical activity as medicine in the care of people with severe mental illness. 2015;49(8) doi: 10.1177/0004867415590831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. 2011:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen AW, Flensborg-Madsen T, Helge JW, Brage S, Grønbæk M, Dahl-Petersen I. Validation of an Internet-Based Long Version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in Danish Adults Using Combined Accelerometry and Heart Rate Monitoring. J Phys Act Heal. 2016;11(3):654–64. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rääsk T, Maёstu J, Lätt E, Jürimäe J, Jürimäe T, Vainik U, et al. Comparison of IPAQ-SF and two other physical activity questionnaires with accelerometer in adolescent boys. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanda B, Vistad I, Haakstad LAH, Berntsen S, Sagedal LR, Lohne-Seiler H, et al. Reliability and concurrent validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form among pregnant women. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2017;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13102-017-0070-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavelle G, Noorkoiv M, Theis N, Korff T, Kilbride C, Baltzopoulos V, et al. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF) as a measure of physical activity (PA) in young people with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional study. Physiother (United Kingdom) 2020;107:209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monyeki M, Moss S, Kemper H, Twisk J. Self-Reported Physical Activity is Not a Valid Method for Measuring Physical Activity in 15-Year-Old South African Boys and Girls. Children. 2018;5(6):71. doi: 10.3390/children5060071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finger JD, Gisle L, Mimilidis H, Santos-Hoevener C, Kruusmaa EK, Matsi A, et al. How well do physical activity questions perform? A European cognitive testing study. Arch Public Heal. 2015;73(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faurholt-Jepsen M, Brage S, Vinberg M, Jensen HM, Christensen EM, Knorr U, et al. Electronic monitoring of psychomotor activity as a supplementary objective measure of depression severity. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(2):118–25. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.936501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faurholt-Jepsen M, Brage S, Vinberg M, Christensen EM, Knorr U, Jensen HM, et al. Differences in psychomotor activity in patients suffering from unipolar and bipolar affective disorder in the remitted or mild/moderate depressive state. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2-3):457–63. doi: 10.1016/jjad.2012.02.020. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freyberg J, Brage S, Kessing LV, Faurholt-Jepsen M. Differences in psychomotor activity and heart rate variability in patients with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder, unaffected relatives, and healthy individuals. J Affect Disord. 2020;266(January):30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessing LV, Mayora O, Knudsen GM, Pedersen BK, Phillips M, Faurholt-Jepsen M, et al. The Bipolar Illness Onset study: research protocol for the BIO cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015462. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maier W, Philipp M, Zaudig M. Comparison ofthe ICD-10-Classification with the ICD-9 and the DSM-III-Classification of Mental Disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1990;23:183–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arlington V. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Am Psychiatr Assoc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha J, Cooper JE, Giel R. SCAN. Schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990 doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180089012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967 doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young BRC. A Rating Scale for Mania : Reliability, Validity and Sensitivity. Brit J Psychiat. 1978;133:429–64. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poppel MNM Van, Chinapaw MJM, Mokkink LB, Mechelen W Van, Terwee CB. Physical Activity Questionnaires for Adults A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. 2010;40(7):565–600. doi: 10.2165/11531930-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ipaq. Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire ( IPAQ ) - Short and Long Forms. Ipaq; 2005. Nov, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brage S, Brage N, Franks PW, Ekelund U, Wareham NJ. Reliability and validity of the combined heart rate and movement sensor actiheart. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(4):561–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brage S, Ekelund U, Brage N, Hennings MA, Froberg K, Franks PW, et al. Hierarchy of individual calibration levels for heart rate and accelerometry to measure physical activity. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103(2):682–92. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00092.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crouter SE, Churilla JR, Bassett DR. Accuracy of the Actiheart for the assessment of energy expenditure in adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(6):704–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson D, Batterham AM, Bock S, Robson C, Stokes K. Assessment of low-to-moderate intensity physical activity thermogenesis in young adults using synchronized heart rate and accelerometry with branched-equation modeling. J Nutr. 2006;136(4):1037–42. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.4.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brage S, Westgate K, Franks PW, Stegle O, Wright A, Ekelund U, et al. Estimation of Free-Living Energy Expenditure by Heart Rate and Movement Sensing: A Doubly-Labelled Water Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindsay T, Westgate K, Wijndaele K, Hollidge S, Kerrison N, Griffin S, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of physical activity energy expenditure in UK adults. The Fenland Study. 2019:1–35. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0882-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahl-Petersen IK, Hansen AW, Bjerregaard P, Jkrgensen ME, Brage S. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire in the arctic. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(4):728–36. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827a6b40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, van Poppel MNM, Chinapaw MJM, van Mechelen W, de Vet HCW. Qualitative attributes and measurement properties of physical activity questionnaires: a checklist. Sports medicine [Sl]: Adis International. 2010;40:525–37. doi: 10.2165/11531370-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaleth AS, Ang DC, Chakr R, Tong Y. Validity and reliability of community health activities model program for seniors and short-form international physical activity questionnaire as physical activity assessment tools in patients with fibromyalgia. Disabil Rehabil. 2010 Jan 1;32(5):353–9. doi: 10.3109/09638280903166352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G. Validation of a physical activity assessment tool for individuals with schizophrenia. 2006;82:225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grimes D a, Schulz KF. Epidemiology 5: Case-control studies: research in reverse. Lancet (London, England) 2002;359(9304):431–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]