Abstract

1,2-Bis-boronic esters are versatile intermediates that enable the rapid elaboration of simple alkene precursors. Previous reports on their selective mono-functionalization have targeted the most accessible position, retaining the more hindered secondary boronic ester. In contrast, we have found that photoredox-catalyzed mono-deboronation generates primary β-boryl radicals that undergo rapid 1,2-boron shift to form thermodynamically favored secondary radicals, allowing for selective transformation of the more hindered boronic ester. The pivotal 1,2-boron shift, which has been demonstrated to be stereoretentive, enables access to a wide range of functionalized boronic esters and has been applied to highly diastereoselective fragmentation and transannular cyclization reactions. Furthermore, its generality has been shown in a radical cascade reaction with an allylboronic ester.

Photoredox chemistry enables radical species to be generated from a broad range of functional groups under exceptionally mild conditions.1 We and others have shown that readily available alkylboron reagents, including boronic esters2 and trifluoroborate salts,3 undergo deboronative single-electron oxidation to give alkyl radical intermediates that engage in Giese-type additions,2a-c,3a-d hydrogen atom transfer,2f nickel-catalyzed cross couplings,2e,3e-h and radical-polar cross-over reactions (Scheme 1A).2d,31 Despite these diverse photoredox-catalyzed transformations of alkylborons, related reactions that use 1,2-bis-boron species as radical precursors have yet to be explored. However, such processes would be highly valuable since (i) 1,2-bis-boronic esters are easily prepared from alkenes, often with high enantioselectivity;4 and (ii) following the deboronative radical reaction, a boronic ester is retained for use in further transformations.5

Scheme 1. Alkylborons as radical precursors and functionalizations of 1,2-bis-boronic esters.

Previous reports of mono-functionalizations of 1,2-bis-boronic esters (1) have involved selective reaction at the primary boronic ester, which is due to favorable activation (boronate complex formation) of the sterically less hindered boron atom (Scheme 1B).6 Based on this precedent, selective formation of boronate complex 2 followed by photoredox-catalyzed single-electron oxidation and reaction of the resulting primary radical would give a product bearing a secondary boronic ester (Scheme 1C, path A). However, given the instability of primary alkyl radicals, we considered the possibility of a radical 1,2-boron shift to provide the thermodynamically more stable secondary radical (Scheme 1C, path B). Thermodynamically driven 1,2-group transfers of alkyl radicals are mainly limited to migrations of π-systems, such as the well-established neophyl and Dowd-Beckwith rearrangements.7 Related heteroatom-transfers are rare but have been proposed for halogen8 and silicon groups.9 There have been isolated reports of 1,2-boron migrations, including via cationic10 or anionic intermediates,11 and a single report by Batey in 1999 which showed that β-boryl radicals are capable of undergoing intramolecular homolytic substitution.12 In our proposed strategy, a radical migration of the boronic ester group would enable a cascade sequence of 1,2-shift and subsequent reaction of the resulting thermodynamically favored secondary alkyl radical (Scheme 1C, path B). This would lead to a product in which it appeared as if the more hindered secondary boronic ester had been activated, providing the opposite selectivity to that typically observed for functionalizations of 1,2-bis-boronic esters.6,13 We now report that, in photoredox-catalyzed deboronative Giese reactions of 1,2-bis-boronic esters, following activation of the less hindered primary boronic ester, the exclusive product obtained is that derived from substitution of the secondary boronic ester.

Our initial investigations of the reaction of 1,2-bis-boronic ester 1a were based on our recent report of a deboronative cyclobutane synthesis, where phenyllithium was successfully employed to form a highly reducing boronate complex (Table 1).2d Thus, a boronate complex was formed by reaction of 1a with phenyllithium (A) in THF, and a solution of photoredox catalyst (4CzIPN), tert-butyl acrylate, and tert-butanol in DMF was added. The subsequent reaction under blue light irradiation afforded the product of functionalization at the secondary position (3a) in a promising 48% yield (entry 1). Two characteristics of this initial reaction are noteworthy: (i) no trace of regioisomeric product 4 was detected in the crude reaction mixture, confirming that a 1,2-boron shift occurred to form the more stable secondary radical; and (ii) we observed 12% of doubly functionalized product 5 and recovered 27% of 1a. This suggested low selectivity between single and double addition of A to 1a. Hoping to increase the selectivity, we turned to more sterically hindered aryllithium reagents (B-G, entries 2–7). Pleasingly, this approach proved successful, with ortho-substituted aryllithiums suppressing the formation of 5. From this series of reactions, B emerged as the ideal reagent in terms of yield (68%), cost and reproducibility. A subsequent screen of solvents identified acetonitrile as optimal (entry 8).14 Finally, a slight increase in concentration (compare entries 8–10) gave 3a in 90% isolated yield, while the absence of tBuOH (required for protonation of the enolate intermediate; entry 11), light (entry 12) or photocatalyst (entry 13) led to dramatically diminished yields.

Table 1. Optimization Studies.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry a | ArLi | Solvent | c (M) | 3a (%) b | 1a (%) b |

| 1 | A | DMF | 0.05 | 48 | 27 |

| 2 | B | DMF | 0.05 | 68 | 12 |

| 3 | C | DMF | 0.05 | 38 | 27 |

| 4 | D | DMF | 0.05 | 75 | 15 |

| 5 | E | DMF | 0.05 | 70 | 9 |

| 6 | F | DMF | 0.05 | 70 | 2 |

| 7 | G | DMF | 0.05 | 29 | 11 |

| 8 | B | MeCN | 0.05 | 88 | 2 |

| 9 | B | MeCN | 0.1 | 100(90) | 0 |

| 10 | B | MeCN | 0.2 | 89 | 5 |

| 11 c | B | MeCN | 0.1 | 11 | 37 |

| 12 d | B | MeCN | 0.1 | 0 | 17 |

| 13 e | B | MeCN | 0.1 | <1 | 33 |

| |||||

Reactions were run on 0.2 mmol scale.

Determined by GC/MS analysis; values in parentheses correspond to isolated yields.

Without tBuOH.

In the dark.

Without 4CzIPN.

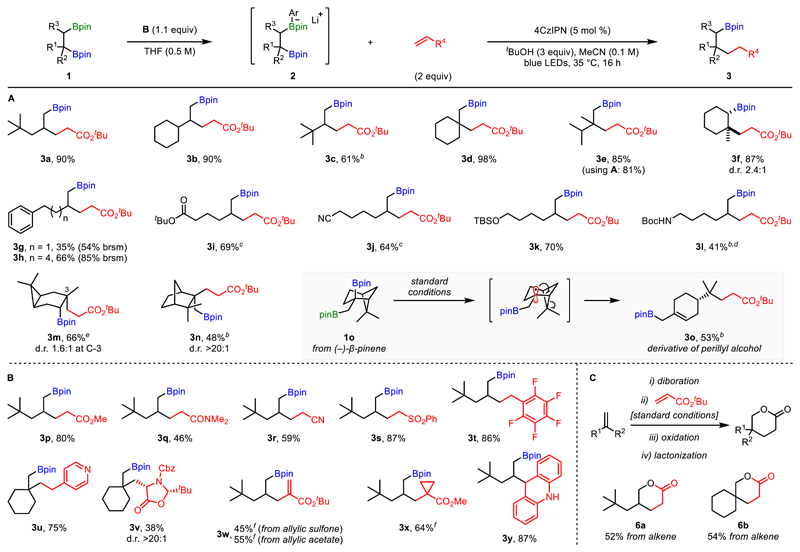

With the optimized conditions in hand, we investigated the scope of bis-boronic esters (Scheme 2A). Initially, we probed the effects of steric hindrance on the reaction efficiency and were pleased to see that products with α-secondary (3b) and α-tertiary centres (3c) were formed readily. Moreover, substrates containing a tertiary boronic ester (3d–3f) provided excellent yields of the products of tertiary functionalization. It should be noted that for substrates showing considerable steric bias between the two boronic ester groups (e.g., 3e), using phenyllithium instead of B provided almost identical results (81% compared to 85% for B). Surprisingly, phenyl-containing 3g was only isolated in moderate yield (35%) and an equimolar amount of starting material was recovered. We speculated that competitive addition of the transient radical intermediate to the aryl ring could (i) lead to unspecific degradation, as indicated by the low mass balance; and (ii) slow down turnover of the photocatalyst, thereby allowing the boronate complex intermediate to decompose over time.14 When a homologated substrate was used, product 3h was afforded in considerably increased yield (66%), suggesting the vicinity of the phenyl moiety was in fact inhibiting formation of 3g. Unfortunately, styrene-derived bis-boronic esters failed to give the desired products.14 In addition to substrates of varying steric demand, various functional groups were also tolerated, including esters (3i), nitriles (3j) and silyl ethers (3k)—the former two requiring the use of less hindered aryllithium D in order to suppress competing α-deprotonation. Additionally, using two equivalents of aryllithium allowed isolation of secondary carbamate 3l in moderate yield. Bis-boronic esters derived from 3-carene and camphene were also competent substrates, affording the corresponding products 3m and 3n in good yields, with excellent diastereoselectivity observed for the latter product. The 1,2-bis-boronic ester derivative of β-pinene (1o) provided monocyclic product 3o in 53% yield. This compound is the product of ring-opening of the strained cyclobutane moiety after 1,2-boron shift, highlighting the radical nature of this transformation.

Scheme 2. Reaction Scope.a .

a Reactions were run on 0.2 mmol scale, unless otherwise noted. Yields are of isolated products. b Isolated as the corresponding alcohols after oxidation. c Using aryllithium D. d Using 2.0 equiv B. e Run on 0.15 mmol scale. f Without tBuOH.

Our interest subsequently shifted to investigation of the radical acceptor (Scheme 2B). Radical conjugate addition to a range of electron-deficient alkenes afforded the desired products (3p–3s) in good to excellent yields. Styrene derivatives were also found to be competent radical acceptors, with pentafluorostyrene efficiently affording 3t. On the other hand, 4-vinylpyridine, a comparatively weaker acceptor, only reacted with more nucleophilic tertiary radicals, forming 3u in 75% yield. Employing an enantiopure dehydroalanine derivative provided product 3v in only moderate yield, but with complete diastereocontrol. While the aforementioned reactions all require protonation to form the corresponding products, we were interested in exploring alternative modes of termination. In this sense, enoate 3w was synthesized via two mechanistically distinct addition-elimination sequences from either the allylic sulfone (radical elimination, 45%) or the allylic acetate (polar elimination, 55%). Following our recent report on radical addition-polar cyclization cascades,2d formation of cyclopropane 3x was also shown to be a viable pathway for this transformation. Additionally, acridine reacted readily with the secondary radical generated from 1a, providing 3y in excellent yield.

As a demonstration of the synthetic utility of this methodology, we sought to highlight its application in the synthesis of valuable structures (Scheme 2C). By using a diboration/photoredox-catalyzed deboronative Giese reaction/oxidation/lactonization sequence, we were able to transform unfunctionalized alkenes into lactones 6a and 6b in good yields over four steps.

Based on previous reports on the oxidation of boronate complexes,2,3 and the observed regioselectivity of our reaction, we propose the mechanism depicted in Scheme 3. Initial oxidation of primary boronate complex 2 by the excited state photoredox catalyst generates a primary radical with concomitant loss of an equivalent of arylboronic ester 7.15 Subsequent equilibration of the radical species through 1,2-boron shift of 8 affords thermodynamically favored secondary radical 9. Addition of 9 to the radical acceptor forms electron deficient radical 10, which accepts an electron from the reduced form of the photoredox catalyst. Finally, anion 11 is protonated to afford product 3.

Scheme 3. Mechanistic Proposal.

At this point, we were intrigued as to whether our approach could be extended to the selective functionalization of 1,2,3-tris-boronic esters (Scheme 4A). We therefore subjected 12 to our reaction conditions and were pleased to isolate 13, the product of sequential double 1,2-shift of two boronic esters in 79% yield. Notably, this product is formed with impeccable selectivity, highlighting the thermodynamic control that favors the most stabilized radical center as the site of reaction.

Scheme 4. Additional Studies.

a Isolated as the corresponding alcohols after oxidation.

Given the ease in which 1,2-bis-boronic esters can be prepared from readily available alkenes, we were keen to explore substrates derived from dienes, which could potentially undergo radical cascade reactions. We were attracted by cyclooctadiene derivatives, which could undergo transannular radical reactions (Scheme 4B). Pleasingly, under the standard conditions, diborated cyclooctadiene (14) reacted to give bicyclic product 15 in 51% yield and with excellent diastereoselectivity, alongside uncyclized product 16 (33%). This unusual radical cyclization can be viewed as both a 5-exo- and 5-endo-trig cyclization, accounting for its relatively low rate of ring closure (k = 3.3 × 104 s−1),16 and consequently significant formation of the direct trapping product 16.17

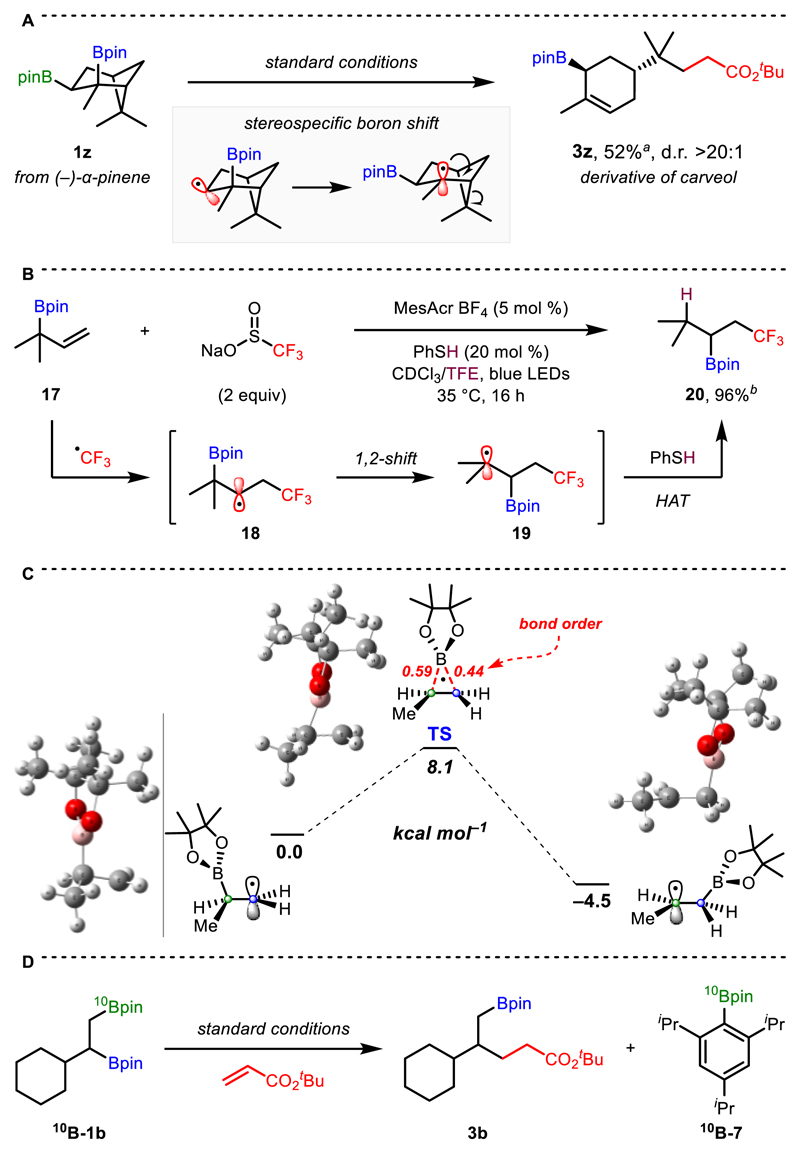

We subsequently turned our attention to the 1,2-boron shift. If this occurs via an intramolecular homolytic substitution, we reasoned that it could proceed with high stereospecificity. Thus, we investigated the stereochemical outcome of the reaction using diastereomerically pure 1z, derived from α-pinene (Scheme 5A). The expected product of 1,2-shift and subsequent ring opening (3z) was obtained in 52% yield and with >20:1 d.r., in which the boronic ester migrated with high stereochemical fidelity. Further support for this was provided by the formation of 3m from diborated 3-carene (Scheme 2A), in which boron migration occurred with complete stereospecificity but subsequent reaction of the resulting tertiary radical proceeded with poor diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 5. Investigations into the 1,2-Boron Shift.

a Isolated as the corresponding alcohols after oxidation. b Determined by 1H NMR analysis.

Unequivocal proof for the 1,2-boron shift was obtained by treatment of allylboronic ester 17 with Langlois’ reagent under Nicewicz’s hydrotrifluoromethylation conditions, which gave 20 in 96% yield (Scheme 5B).18. This reaction proceeds via addition of a trifluoromethyl radical to 17 to provide secondary β-boryl radical 18. 1,2-Transposition of the boronic ester affords the thermodynamically favored tertiary radical 19, which undergoes hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) with thiophenol to form 20. The high regioselectivity observed implies that 1,2-boron shift from a tertiary (18) to a secondary position (19) is much more rapid than HAT with thiophenol, which has a rate of k = 1 × 108 M−1 s−1 for secondary alkyl radicals.19 Further insight into the facile nature of the 1,2-shift was provided by modelling the process using DFT, which revealed a barrier of only 8.1 kcal mol−1 for migration of a secondary boronic ester to a primary radical (Scheme 5C). Finally, boron-isotope labelling studies using mono-labelled 1,2-bis-boronic ester 10 B-1b yielded unlabelled product 3b and labelled arylboronic ester 10 B-7, confirming that boronate complex formation with aryllithium B occurs exclusively at the primary boronic ester (Scheme 5D).

In conclusion, we have described the use of boronate complexes derived from 1,2-bis-boronic esters in photoredox-catalyzed radical transformations. This reaction demonstrates, for the first time, a radical 1,2-boron shift under thermodynamic control, allowing for counter-intuitive selective functionalization of the more hindered position of 1,2-bis-boronic esters. We have demonstrated a broad substrate scope and highlighted the diversity of the method in ring fragmentation and transannular reactions. Furthermore, the stereoretentive nature of the 1,2-boron shift was shown and we have showcased the application of this approach in different settings by extending it to radical cascades with allylboronic esters.

Acknowledgment

We thank H2020 ERC (670668) for financial support. D.K. thanks the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) for an Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship (J 4202-N28). V.F. thanks the EPSRC for a Doctoral Prize Fellowship. We thank Dr. Amadeu Bonet for useful discussions.

Footnotes

Associated Content

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental procedures and characterization data for new compounds (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- (1).(a) Shaw MH, Twilton J, MacMillan DWC. Photoredox Catalysis in Organic Chemistry. J Org Chem. 2016;81:6898. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Narayanama JMR, Stephenson CRJ. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:102. doi: 10.1039/b913880n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Prier CK, Rankic DA, MacMillan DWC. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem Rev. 2013;113:5322. doi: 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Goddard J-P, Ollivier C, Fensterbank L. Photoredox Catalysis for the Generation of Carbon Centered Radicals. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:1924. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Staveness D, Bosque I, Stephenson CRJ. Free Radical Chemistry Enabled by Visible Light-Induced Electron Transfer. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:2295. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Marzo L, Pagire SK, Reiser O, König B. Visible-Light Photocatalysis: Does It Make a Difference in Organic Synthesis? Angew Chem Int Ed. 2018;57:10034. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Yasu Y, Koike T, Akita M. Visible Light-Induced Selective Generation of Radicals from Organoborates by Photoredox Catalysis. Adv Synth Catal. 2012;354:3414. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lima F, Sharma UK, Grunenberg L, Saha D, Johannsen S, Sedelmeier J, Van der Eycken EV, Ley SV. A Lewis Base Catalysis Approach for the Photoredox Activation of Boronic Acids and Esters. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:15136. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lima F, Grunenberg L, Rahman HBA, Labes R, Sedelmeier J, Ley SV. Organic Photocatalysis for the Radical Couplings of Boronic Acid Derivatives in Batch and Flow. Chem Commun. 2018;54:5606. doi: 10.1039/c8cc02169d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shu C, Noble A, Aggarwal VK. Photoredox-Catalyzed Cyclobutane Synthesis by a Deboronative Radical Addition-Polar Cyclization Cascade. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:3870. doi: 10.1002/anie.201813917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lima F, Kabeshov MA, Tran DN, Battilocchio C, Sedelmeier J, Sedelmeier G, Schenkel B, Ley SV. Visible Light Activation of Boronic Esters Enables Efficient Photoredox C(sp2)-C(sp3) Cross-Couplings in Flow. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:14085. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Clausen F, Kischkewitz M, Bergander K, Studer A. Catalytic Protodeboronation of Pinacol Boronic Esters: Formal Anti-Markovnikov Hydromethylation of Alkenes. Chem Sci. 2019;10:6210. doi: 10.1039/c9sc02067e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Duret G, Quinlan R, Bisseret P, Blanchard N. Boron Chemistry in a New Light. Chem Sci. 2015;6:5366. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02207j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Miyazawa K, Yasu Y, Koike T, Akita M. Visible-Light-Induced Hydroalkoxymethylation of Electron-Deficient Alkenes by Photoredox Catalysis. Chem Commun. 2013;49:7249. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42695e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miyazawa K, Koike T, Akita M. Hydroaminomethylation of Olefins with Aminomethyltrifluoroborate by Photoredox Catalysis. Adv Synth Catal. 2014;356:2749. [Google Scholar]; (c) Chinzei T, Miyazawa K, Yasu Y, Koike T, Akita M. Redox-Economical Radical Generation from Organoborates and Carboxylic Acids by Organic Photoredox Catalysis. RSC Adv. 2015;5:21297. [Google Scholar]; (d) Huo H, Harms K, Meggers E. Catalytic, Enantioselective Addition of Alkyl Radicals to Alkenes via Visible-Light-Activated Photoredox Catalysis with a Chiral Rhodium Complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:6936. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tellis JC, Primer DN, Molander GA. Single-Electron Transmetalation in Or-ganoboron Cross-Coupling by Photoredox/Nickel Dual Catalysis. Science. 2014;345:433. doi: 10.1126/science.1253647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Primer DN, Karakaya I, Tellis JC, Molander GA. Single-Electron Transmetalation: An Enabling Technology for Secondary Alkylboron Cross-Coupling. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2195. doi: 10.1021/ja512946e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Primer DN, Molander GA. Enabling the Cross-Coupling of Tertiary Organoboron Nucleophiles through Radical-Mediated Alkyl Transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:9847. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b06288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Amani J, Molander GA. Synergistic Photoredox/Nickel Coupling of Acyl Chlorides with Secondary Alkyltrifluoroborates: Dialkyl Ketone Synthesis. J Org Chem. 2017;82:1856. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Huang H, Zhang G, Gong L, Zhang S, Chen Y. Visible-Light-Induced Chemoselective Deboronative Alkynylation under Biomolecule-Compatible Conditions. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2280. doi: 10.1021/ja413208y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Huang H, Jia K, Chen Y. Hypervalent Iodine Reagents Enable Chemoselective Deboronative/Decarboxylative Alkenylation by Photoredox Catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:1881. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Heitz DR, Rizwan K, Molander GA. Visible-Light-Mediated Alkenylation, Allylation, and Cyanation of Potassium Alkyltrifluoroborates with Organic Photoredox Catalysts. J Org Chem. 2016;81:7308. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Lang SB, Wiles RJ, Kelly CB, Molander GA. Photoredox Generation of Carbon-Centered Radicals Enables the Construction of 1,1-Difluoroalkene Carbonyl Mimics. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:15073. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Bonet A, Pubill-Ulldemolins C, Bo C, Gulyás H, Fernández E. Transition-Metal-Free Diboration Reaction by Activation of Diboron Compounds with Simple Lewis Bases. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:7158. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miralles N, Cid J, Cuenca AB, Carbó JJ, Fernández E. Mixed Diboration of Alkenes in a Metal-Free Context. Chem Commun. 2015;51:1693. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08743g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Farre A, Soares K, Briggs RA, Balanta A, Benoit DM, Bonet A. Amine Catalysis for the Organocatalytic Diboration of Challenging Alkenes. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:17552. doi: 10.1002/chem.201603979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Farre A, Briggs R, Pubill-Ulldemolins C, Bonet A. Developing a Bench-Scale Green Diboration Reaction toward Industrial Application. Synthesis. 2017;49:4775. [Google Scholar]; (e) Bonet A, Sole C, Gulyás H, Fernández E. Asymmetric Organocatalytic Diboration of Alkenes. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:6621. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26079d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Blaisdell TP, Caya TC, Zhang L, Sanz-Marco A, Morken JP. Hydroxyl-Directed Stereoselective Diboration of Alkenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9264. doi: 10.1021/ja504228p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Fang L, Yan L, Haeffner F, Morken JP. Carbohydrate-Catalyzed Enantioselective Alkene Diboration: Enhanced Reactivity of 1,2-Bonded Diboron Complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:2508. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yan L, Meng Y, Haeffner F, Leon RM, Crockett MP, Morken JP. Carbohydrate/DBU Cocatalyzed Alkene Diboration: Mechanistic Insight Provides Enhanced Catalytic Efficiency and Substrate Scope. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:3663. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Morgan JB, Miller SP, Morken JP. Rhodium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Diboration of Simple Alkenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8702. doi: 10.1021/ja035851w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Trudeau S, Morgan JB, Shrestha M, Morken JP. Rh-Catalyzed Enantioselective Diboration of Simple Alkenes: Reaction Development and Substrate Scope. J Org Chem. 2005;70:9538. doi: 10.1021/jo051651m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Kliman LT, Mlynarski SN, Morken JP. Pt-Catalyzed Enantioselective Diboration of Terminal Alkenes with B2(pin)2. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13210. doi: 10.1021/ja9047762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Coombs JR, Haeffner F, Kliman LT, Morken JP. Scope and Mechanism of the Pt-Catalyzed Enantioselective Diboration of Monosubstituted Alkenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:11222. doi: 10.1021/ja4041016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Toribatake K, Nishiyama H. Asymmetric Diboration of Terminal Alkenes with a Rhodium Catalyst and Subsequent Oxidation: Enantioselective Synthesis of Optically Active 1,2-Diols. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:11011. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Toribatake K, Nishiyama H, Miyata S, Naganawa Y, Nishiyama H. Asymmetric Synthesis of Optically Active 3-Amino-1,2-Diols from N-Acyl-Protected Allylamines via Catalytic Diboration with Rh[bis(oxazolinyl)phenyl] Catalysts. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:3203. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Sandford C, Aggarwal VK. Stereospecific Functionalizations and Transformations of Secondary and Tertiary Boronic Esters. Chem Commun. 2017;53:5481. doi: 10.1039/c7cc01254c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Miller SP, Morgan JB, Nepveux FJV, Morken JP. Cat-alytic Asymmetric Carbohydroxylation of Alkenes by a Tandem Diboration/Suzuki Cross-Coupling/Oxidation Reaction. Org Lett. 2004;6:131. doi: 10.1021/ol036219a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee Y, Jang H, Hoveyda AH. Vicinal Diboronates in High Enantiomeric Purity through Tandem Site-Selective NHC-Cu-Catalyzed Boron-Copper Additions to Terminal Alkynes. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18234. doi: 10.1021/ja9089928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mlynarski SN, Schuster CH, Morken JP. Asymmetric Synthesis from Terminal Alkenes by Cascades of Diboration and CrossCoupling. Nature. 2014;505:386. doi: 10.1038/nature12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fawcett A, Nitsch D, Ali M, Bateman JM, Myers EL, Aggarwal VK. Regio- and Stereoselective Homologation of 1,2-Bis(Boronic Esters): Stereocontrolled Synthesis of 1,3-Diols and Sch 725674. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:14663. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu X, Sun C, Mlynarski S, Morken JP. Synthesis and Stereochemical Assignment of Arenolide. Org Lett. 2018;20:1898. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Urry WH, Kharasch MS. Factors Influencing the Course and Mechanism of Grignard Reactions. XV. The Reaction of β,β-Dimethylphenethyl Chloride with Phenylmagnesium Bromide in the Presence of Cobaltous Chloride. J Am Chem Soc. 1944;66:1438. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dowd P, Choi SC. A New Tri-n-butyltin Hydride Based Rearrangement of Bromomethyl β-Keto Esters. A Synthetically Useful Ring Expansion to γ-Keto Esters. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:3493. [Google Scholar]; (c) Athelstan LJ, Beckwith ALJ, O’Shea DM, Gerba S, Westwood SW. Cyano or Acyl Group Migration by Consecutive Homolytic Addition and β-Fission. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1987:666. For reviews, see: [Google Scholar]; (d) Dowd P, Zhang W. Free Radical Mediated Ring Expansion and Related Annulations. Chem Rev. 1993;93:2091. [Google Scholar]; (e) Chen Z-M, Zhang X-M, Tu Y-Q. Radical Aryl Migration Reactions and Synthetic Applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:5220. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00467a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Weng W-Z, Zhang B. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of β-Functionalized Ketones by Radical-Mediated 1,2-Rearrangement of Allylic Alcohols. Chem Eur J. 2018;24:10934. doi: 10.1002/chem.201800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Skell PS, Allen RG, Gilmour ND. Radical Rearrangements in Bromoalkyl Radicals. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;81:504. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen KS, Elson IH, Kochi JK. Bridging in β-Chloroalkyl Radicals by Electron Spin Resonance. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:5341. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tan EW, Chan B, Blackman AG. A Polar Effects Controlled Enantioselective 1,2-Chlorine Atom Migration via a Chlorine-Bridged Radical Intermediate. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2078. doi: 10.1021/ja011129r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Neumann B, Zipse H. 1,2-Chlorine Atom Migration in 3-Chloro-2-butyl Radicals: A Computational Study. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:168. doi: 10.1039/b209981k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chen H-L, Wei D, Zhang J-W, Li C-L, Yu W, Han B. Synthesis of Halomethyl Isoxazoles/Cyclic Nitrones via Cascade Sequence: 1,2-Halogen Radical Shift as a Key Link. Org Lett. 2018;20:2906. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Schiesser CH, Styles ML. On the Radical Brook and Related Reactions: An Ab Initio Study of some (1,2)-Silyl, Germyl and Stannyl Translocations. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2. 1997:2335. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shuto S, Kanazaki M, Ichikawa S, Minakawa N, Matsuda A. Stereo- and Regioselective Introduction of 1- or 2-Hydroxyethyl Group via Intramolecular Radical Cyclization Reaction with a Novel Silicon-Containing Tether. An Efficient Synthesis of 4’α-Branched 2’-Deoxyadenosines. J Org Chem. 1998;63:746. doi: 10.1021/jo971703a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sugimoto I, Shuto S, Matsuda A. Kinetics of a Novel 1,2-Rearrangement Reaction of β-Silyl Radicals. The Ring-expansion of (3-Oxa-2-silacyclopentyl)methyl Radical into 4-Oxa-3-silacyclohexyl Radical Is Irreversible. Synlett. 1999;10:1766. [Google Scholar]; (d) Walton JC, Kanada R, Takeaki I, Shuto S, Abe H. Tethered 1,2-Si-Group Migrations in Radical-Mediated Ring Enlargements of Cyclic Alkoxysilanes: An EPR Spectroscopic and Computational Investigation. J Org Chem. 2017;82:6886. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lee CF, Diaz DB, Holownia A, Kaldas SJ, Liew SK, Garrett GE, Dudding T, Yudin AK. Amine Hemilability Enables Boron to Mechanistically Resemble either Hydride or Proton. Nat Chem. 2018;10:1062. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Tao Z, Robb KA, Panger JL, Denmark SE. Enantioselective, Lewis Base-Catalyzed Carbosulfenylation of Alkenylboronates by 1,2-Boronate Migration. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:15621. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10288. Although an anionic pathway for boryl migration was proposed, it is possible that the reaction occurs through a radical process similar to that described in this paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Batey RA, Smil DV. The First Boron-Tethered Radical Cyclizations and Intramolecular Homolytic Substitutions at Boron. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1999;38:1798. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990614)38:12<1798::AID-ANIE1798>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Blaisdell TP, Morken JP. Hydroxyl-Directed Cross-Coupling: A Scalable Synthesis of Debromohamigeran E and Other Targets of Interest. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8712. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05477. For the only examples of selective fonctionalization of the secondary position of 1,2-bis-boronic esters, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yan L, Morken JP. Site-Selective Mono-Oxidation of 1,2-Bis(boronates) Org Lett. 2019;21:3760. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01204. For an example of selective deboronative functionalisation of internal position of a 1,2,3-triboronic ester, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Davenport E, Fernandez E. Transition-Metal-Free Synthesis of Vicinal Triborated Compounds and Selective Functionalisation of the Internal C-B Bond. Chem Commun. 2018;54:10104. doi: 10.1039/c8cc06153j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).See Supporting Information for details

- (15).Aryl boronic ester 7 (Ar = 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl) was isolated in 82% yield from the reaction of 1d with tert-butyl acrylate

- (16).Villa G, Povie G, Renaud P. Radical Chain Reduction of Alkyl-boron Compounds with Catechols. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5913. doi: 10.1021/ja110224d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Performing the reaction under more dilute conditions (0.02 M) led to an enhanced ratio (15:16 = 4.1:1). However, the overall efficiency suffered and 15 was isolated in a similar yield of 53%

- (18).Wilger DJ, Gesmundo NJ, Nicewicz DA. Catalytic Hydrotri-fluoromethylation of Styrenes and Unactivated Aliphatic Alkenes via an Organic Photoredox System. Chem Sci. 2013;4:3160. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Dénès F, Pichowicz M, Povie G, Renaud P. Thiyl Radicals in Organic Synthesis. Chem Rev. 2014;114:2587. doi: 10.1021/cr400441m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]