Abstract

Background

Many European countries introduced (confidential) rebates in the past years. Authorities and manufacturers argue that this strategy allows reduction of spending on high-cost drugs, and quick access of innovative drugs. We evaluated these arguments using Switzerland as an example, one of the last countries with transparent rebates.

Methods

We identified all drugs granted rebates in Switzerland and all new drugs without rebates between January 2012 and October 2020. We assessed the amount of introduced drugs with and without rebates over time, clinical benefit of drugs with rebates, and duration between approval and price determination.

Findings

Our study cohort included 51 drugs with rebates, the majority were cancer drugs (32; 63%). 15/51 (29%) had high clinical benefit, 25/51 (49%) low benefit and for 11/51 (22%) benefit could not be assessed. The number of drugs with rebates increased in recent years. Time duration between approval and price determination was 302 days in median for drugs with and 106 days for drugs without rebates.

Interpretation

Drugs with rebates may hamper access to drugs and lead to overpayment. Improving transparency on actual drug prices and stronger cooperation between countries could help national authorities to make better informed pricing decisions, and improve access of innovative drugs to patients.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Swiss Cancer Research Foundation (Krebsforschung Schweiz) and the Swiss National Foundation (SNF).

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Manufacturers and national authorities argue that (confidential) rebates allow to reduce spending on high-cost drugs and enable quicker access of drugs to patients by allowing more flexibility when negotiating the drug prices with manufacturers. By contrast, the WHO and former studies consider (confidential) rebates as problematic since it could lead to a distortion of drug prices and hamper timely access to drugs.

Added value of this study

In this study, we empirically assessed the arguments of manufacturers and national authorities. Using Switzerland as an example, our empirical study results demonstrated that drugs with granted rebates have increased in the past years with a focus on cancer drugs. Rebates were not limited to high-cost drugs and the amount of granted rebates varied strongly. Furthermore, these drugs often did not have a high clinical value, and price determination (i.e., access to drugs) may be prolonged.

Implications of all the available evidence

The results demonstrate the importance of the WHO's resolution urging for information on actual prices paid by governments. Improving transparency on actual drug prices and stronger cooperation between countries could help to identify drugs that should be made rapidly available across countries, help national authorities to make better informed pricing decisions, and ultimately improve access of innovative drugs to patients.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Health care costs have increased in Europe, with drug costs serving as a contributor to this increase [1, 2]. In proportion to the total health care costs, key European countries, such as Germany, France, England, and Switzerland, spent more on drugs than the US [3]. The European Commission highlighted that health systems and patients have difficulty to cover the costs for drug expenditures, thus, ensuring access to affordable drugs for patients in Europe is highly crucial and at stake [4].

In Europe, drug prices are regulated on a national level [5, 6]. The goal of such pharmaceutical pricing policies and regulations is to ensure affordable access to drugs [6, 7]. A frequently applied pricing policy is, for example, external reference pricing [6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes this policy as a tool to allow a government to compare the price of a drug to one or several other countries to derive a benchmark or reference price for the purpose of setting or negotiating the price of the drug in the own country [8]. It shall ensure that the price paid for a drug in a specific country does not exceed unreasonably the price paid in the comparator countries [8, 9].

Official drug prices, also referred to as “publicly available prices” or “list prices”, should reflect the actual ex-factory drug prices [10, 11]. However, in the past years so-called “rebates” or “discounts” were introduced in many European countries (e.g., Germany, France and England) [12, 13], i.e., the national authority and the manufacturer agree that the actual price for a specific drug differ from and is lower than the official drug price. For simplicity we use “rebates” to refer to these practices.

Manufacturers and national authorities argue that (confidential) rebates allow to reduce spending on high-cost drugs and enable quicker access of drugs to patients by allowing more flexibility when negotiating the drug prices with manufacturers [8]. However, drugs that are granted rebates and the specific rebate amounts are confidential in most European countries [12, 14]. This approach masks actual drug prices and may lead to the obstruction of market transparency as well as distortion and overpayment of drug prices [12, 14, 15]. Manufacturers may also be motivated to keep list prices high to impair the effectiveness of external reference pricing [15]. With regard to external reference pricing, (confidential) rebates may incentivize manufacturers to harmonize official drug prices across comparable countries and to use rebates to charge different prices in different countries, thereby, giving manufacturers more power to negotiate prices [16], [17], [18]. Transparent drug prices are also relevant, for example, for the assessment of value-based drug pricing or the allocation of limited financial resources [7].

One of the last transparent countries with regard to drugs that are granted rebates and the specific rebate amounts is Switzerland. However, also Switzerland introduced confidential rebates and the legislator is currently considering to revise the federal health insurance act in order to officially legitimate and promote confidential rebates [13].

To counter this development, the World Health Assembly adopted in May 2019 a resolution to support more transparency of drug prices [19]. The resolution urges member states to enhance public sharing, among other things, of information on actual prices paid by governments, and determinants of pricing. The goal is to help member states make better informed decisions when negotiating drug prices, and ultimately expand access to drugs for patients [19].

To assist the current discussions, we aimed to assess which drugs were granted rebates, the clinical value of these drugs, and whether such drugs may enable quicker access to patients in comparison to drugs without rebates, as suggested by national authorities and manufacturers. Our analyses are based on Switzerland since it is one of the last European countries with, in general, transparent rebates.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and extraction

We used the public database (“special list”) by the Federal Office for Public Health (FOPH) to identify all drugs that were granted rebates as of 1 October 2020 [20]. We extracted the following information for our study cohort: active ingredient, indication, inclusion date on the special list (i.e., date of price determination and coverage by the social health insurance), price of the drug when included in the special list (list price and, if available, specific rebate amount). In cases where a rebate was granted after inclusion of the drug on the special list, we also extracted the date of the first introduction of the rebate. We used the public database by Swissmedic (Swiss drug approval agency) to extract the approval dates of all included drugs with a rebate [21].

Since Switzerland does not have a publicly established health technology assessment value tool, we assessed the clinical benefit of the cancer drugs in our study cohort based on the publicly available and established therapeutic value ratings of Germany (Federal Joint Committee) [22]. We considered the clinical benefit only for those indications for which a rebate was applied when first introduced on the special list. In cases in which drugs with rebates had more than one indication and different clinical benefit values, we focused on the indication with the highest benefit value. Consistent with a previous study, we defined ratings of moderate or greater benefit as “high benefit” and the rest (that is, low benefit, no benefit, not quantifiable benefit) as “low” [23].

We repeated our analysis in the subgroup of drugs with rebates for tumours using the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1.1 (ESMO-MCBS) [24, 25]. Since the ESMO-MCBS tool cannot be applied to haematological cancers, the evaluation was restricted to drugs for solid tumours. For drugs with multiple pivotal clinical trials and different clinical benefit scores, we focused on the highest clinical benefit score. Our calculations were based on the pivotal trials relevant for approval by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) since Swissmedic did not publish such information. Consistent with the developers of the value framework as well as previous studies, high benefit was defined as a score of A-B (in adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy settings) or 4–5 (in palliative setting) [7, 24, 25]. Low benefit was defined as any other score [7, 24, 25].

We calculated monthly treatment costs for each cancer drug in our study cohort and applied commonly used standard patient values (bodyweight of 70 kg and body surface are of 1.70 m2). The recommended dose for the relevant indication was used for calculation [26]. In cases of different dosages for the same indication, we used the dosage with the lowest associated monthly treatment costs. Rebates were calculated based on monthly treatment dosages. Drug prices are, in general, re-evaluated every three years in Switzerland [27], and it is possible that rebates are not granted when the drug was first introduced on the special list, but rather during the re-examination of drug prices at a later point in time. We extracted the drug price when the rebate was first introduced on the special list. All costs were reported in EUR, applying the exchange rate of that date [28]. If the date corresponded to a weekend or holiday, the exchange rate of the last preceding business day was applied.

Lastly, we included all original drugs without a rebate approved since 2011 (approval year of the first drug with a rebate, which was included on the special list in 2012) and included on the special list as of 1 October 2020 into our comparison group. We assessed the time duration between approval and inclusion on the special list for both, the study cohort and the comparison group.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was performed to assess the amount of introduced drugs on the special list with and without a rebate over time, the amount of (cancer) drugs in the study cohort with high and low benefit, and the duration between approval date and inclusion date on the special list for the study cohort and comparison group. For the latter analysis, we only considered the drugs in our study cohort for which rebates were granted when first included in the special list.

All statistical analyses were done in R (version 3.6.2).

2.3. Role of the funding source

This study was funded by the Swiss Cancer Foundation (Krebsforschung Schweiz) and the Swiss National Foundation (SNF). Both funders did not have any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or writing of the report.

3. Results

Our study cohort included 51 drugs with granted rebates between 1 January 2012 and 1 October 2020. The most drugs with rebates, 63% (32/51), were cancer drugs for solid and hematologic tumours (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of drugs with granted rebates classified by therapeutic class.

| Therapeutic class | Total | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Oncology | 32 | 63 |

| Gastroenterology | 3 | 6 |

| Hematology | 3 | 6 |

| Nephrology | 3 | 6 |

| Neurology | 3 | 6 |

| Endocrinology | 2 | 4 |

| Pneumology | 2 | 4 |

| Infectiology | 1 | 2 |

| Psychiatry | 1 | 2 |

| Rheumatology | 1 | 2 |

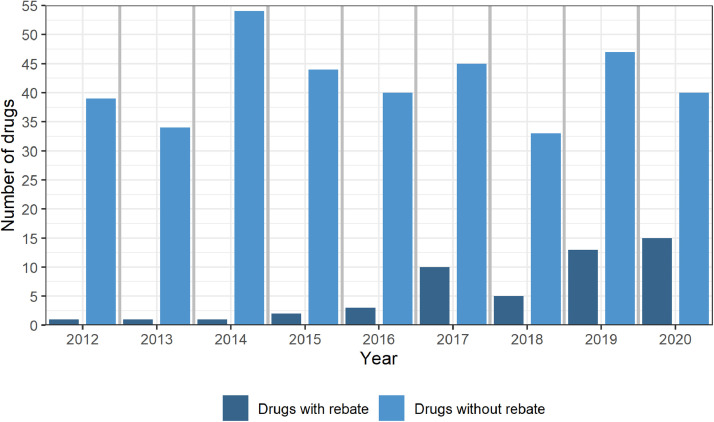

The number of drugs with newly granted rebates increased from 1 in 2012,1 in 2013, 1 in 2014, 2 in 2015, 3 in 2016, 10 in 2017, 5 in 2018, 13 in 2019 to 15 in 2020 (Fig. 1). The number of new drugs included in the special list without rebates (comparison group) in this years were 376 in total, i.e., 39 in 2012, 34 in 2013, 54 in 2014, 44 in 2015, 40 in 2016, 45 in 2017, 33 in 2018, 47 in 2019 and 40 in 2020 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Number of drugs included on the special list (year of price determination) with rebates (left bar) and without rebates (right bar).

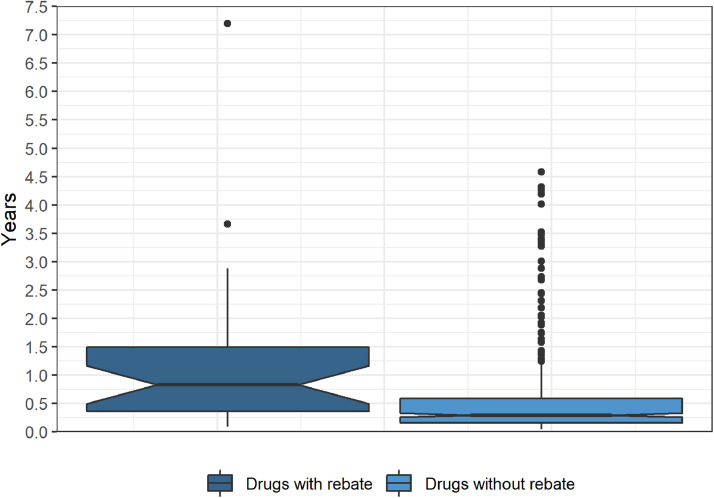

The time duration between drug approval and inclusion on the special list was 302 days in median for drugs with rebates and 106 days for drugs without rebates (Fig. 2). We applied Cox regression to model the duration between approval date and inclusion date. We fitted three different models. A simple model without additional covariates (hazard ratio, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.76), a model with approval year as an additional covariate in the model (hazard ratio, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.74), and a model for right-truncated data (hazard ratio, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.74). In each of the 3 cases, a significant difference between the 2 groups was found.

Fig. 2.

Duration between approval date and inclusion date on the special list (date of price determination). Whiskers are drawn in Tukey style, and dots represent outliers. The notches (+/- 1.58*IQR/sqrt(n)) provide a rough impression about the uncertainty of the median.

Based on the therapeutic value ratings of Germany (Federal Joint Committee), 15 (29%) of the 51 included drugs in our study cohort had a high benefit, 25 (49%) had a low benefit and for 11 (22%) no benefit score was available (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of drugs with granted rebates (approval date, inclusion date on special list [price determination date], active substance, drug name, indication, monthly treatment costs, rebate, clinical benefit). Monthly treatment costs and rebates were calculated for cancer drugs.

| Approval date | Inclusion date | Active substance | Drug name | Indication | Monthly treatment costs (EUR) | Rebate total (EUR) | Rebate percentage (%) | FJC Germany | ESMO-MCBS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05/2020 | 08/2020 | Bevacizumab | Zirabev | Renal cell carcinoma | 3353 | 768 | 23 | – | low |

| 12/2019 | 06/2020 | Talazoparib | Talzenna | Breast cancer | 5437 | confidential | confidential | – | high |

| 12/2019 | 07/2020 | Bevacizumab | MVASI | Renal cell carcinoma | 3400 | 1201 | 35 | – | low |

| 11/2019 | 12/2019 | Binimetinib | Mektovi | Melanoma | 5037 | 1944 | 39 | low | high |

| 06/2019 | 05/2020 | Ceftazidim, Avibactam | Zavicefta | Bacterial infection | – | – | – | – | – |

| 05/2019 | 07/2019* | Abemaciclib | Verzenios | Breast cancer | 3204 | confidential | confidential | low | low |

| 05/2019 | 05/2020 | Ivacaftor, Tezacaftor | Symdeko | Cystic fibrosis | – | confidential | confidential | high | – |

| 03/2019 | 05/2019 | Galcanezumab | Emgality | Chronic migraine / Episodic migraine | – | – | – | low | – |

| 11/2018 | 07/2019* | Emicizumab | hemlibra | haemophilia a | – | confidential | confidential | low | – |

| 10/2018 | 08/2019 | Niraparib | Zejula | Ovarian cancer / Fallopian tube carcinoma / Peritoneal carcinoma | 4962 | – | – | low | low |

| 09/2018 | 09/2019 | Olaparib | Lynparza | Ovarian cancer | 4900 | – | – | low | low |

| 12/2017 | 08/2020 | Patiromer | Veltassa | Hyperpotassemia | – | – | – | low | – |

| 10/2017 | 06/2019 | Ribociclib | Kisqali | Breast cancer | 3160 | confidential | confidential | low | low |

| 09/2017 | 12/2017 | Glecaprevir, Pibrentasvir | Maviret | Chronic hepatitis C | – | – | – | low | – |

| 09/2017 | 03/2018* | Ocrelizumab | Ocrevus | Multiple sclerosis | – | – | 9 | low | – |

| 09/2017 | 07/2020 | Nusinersen | Spinraza | Spinal muscular atrophy | – | confidential | confidential | high | – |

| 09/2017 | 08/2018 | Guanfacin | Intuniv | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | – | – | – | – | – |

| 09/2017 | 12/2017 | Abirateronacetat | Zytiga | Prostate cancer | 3387 | – | – | high | high |

| 08/2017 | 10/2017 | Trifluridin, Tipiracil | Lonsurf | Colorectal carcinoma | 3427 | – | – | low | low |

| 07/2017 | 02/2018 | Inotuzumab ozogamicin | Besponsa | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 28,920 | – | – | low | – |

| 02/2017 | 09/2017* | Pembrolizumab | Keytruda | Hodgkin lymphoma | 6286 | 226 | 4 | low | – |

| 02/2017 | 04/2018 | Ixazomib | Ninlaro | Multiple myeloma | 6893 | 2617 | 38 | low | – |

| 01/2017 | 03/2017* | Palbociclib | Ibrance | Breast cancer | 3029 | confidential | confidential | low | high |

| 12/2016 | 01/2017* | Ixekizumab | Taltz | Plaque psoriasis | – | – | 7 | low | – |

| 12/2016 | 06/2017 | Daratumumab | Darzalex | Multiple myeloma | 10,311 | – | – | low | – |

| 09/2016 | 05/2020 | Lumacaftor, Ivacaftor | Orkambi | Cystic fibrosis | – | confidential | confidential | high | – |

| 07/2016 | 08/2018* | Osimertinib | Tagrisso | Lung cancer | 6027 | confidential | confidential | high | high |

| 06/2016 | 08/2017 | Elotuzumab | Empliciti | Multiple myeloma | 6119 | 1649 | 27 | low | – |

| 04/2016 | 07/2017* | Alirocumab | Praluent | Hypercholesterolemia | – | confidential | confidential | low | – |

| 04/2016 | 11/2016 | Tolvaptan, Tolvaptan | Jinarc | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | – | – | – | – | – |

| 04/2016 | 05/2016* | Grazoprevir, Elbasvir | Zepatier | Chronic hepatitis C | – | – | – | low | – |

| 02/2016 | 10/2017 | Blinatumomab | Blincyto | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 34,577 | – | – | high | – |

| 02/2016 | 07/2016 | Trametinib | Mekinist | Melanoma | 6944 | 2750 | 40 | high | high |

| 02/2016 | 06/2017* | Evolocumab | Repatha | Hypercholesterolemia | – | confidential | confidential | low | – |

| 11/2015 | 04/2016* | Nivolumab | Opdivo | Renal cell carcinoma | 7429 | 1538 | 21 | high | high |

| 11/2015 | 06/2017* | Carfilzomib | Kyprolis | Multiple myeloma | 5721 | 309 | 5 | high | – |

| 10/2015 | 03/2016* | Ramucirumab | Cyramza | Colorectal carcinoma | 4494 | confidential | confidential | low | low |

| 08/2015 | 05/2016 | Cobimetinib | Cotellic | Melanoma | 5993 | 3493 | 58 | high | high |

| 12/2014 | 02/2015* | Sofosbuvir, Ledipasvir | Harvoni | Chronic hepatitis C | – | – | – | high | – |

| 06/2014 | 08/2014* | Pomalidomid | Imnovid | Multiple myeloma | 9839 | 1768 | 18 | high | – |

| 01/2014 | 02/2014* | Dabrafenib | Tafinlar | Melanoma | 4716 | 1489 | 32 | high | high |

| 12/2013 | 03/2014 | Enzalutamid | Xtandi | Prostate cancer | 3581 | – | – | high | high |

| 05/2013 | 01/2014* | Trastuzumab emtansin | Kadcyla | Breast cancer | 5069 | confidential | confidential | low | high |

| 02/2013 | 06/2013* | Regorafenib | Stivarga | Colorectal carcinoma | 4726 | – | – | low | low |

| 12/2012 | 03/2020 | Hydrocortison | Plenadren | Primary adrenal insufficiency | – | confidential | confidential | – | – |

| 08/2012 | 07/2015 | Pertuzumab | Perjeta | Breast cancer | 4957 | 1065 | 21 | high | high |

| 04/2011 | 10/2012 | Cabacitaxel | Jevtana | Hormone refractory prostate cancer | 4322 | – | – | low | low |

| 01/2010 | 02/2012* | Eculizumab | Soliris | Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria | – | – | 5 | – | – |

| 08/2007 | 07/2008* | Lenalidomid | Revlimid | Multiple myeloma | 6050 | 1248 | 21 | – | – |

| 12/2004 | 01/2005* | Bevacizumab | Avastin | Renal cell carcinoma | 5607 | 2346 | 42 | – | low |

| 09/2002 | 11/2002* | Darbepoetin alfa | Aranesp | Myelodysplastic syndrome | – | – | 12 | – | – |

Rebate granted after first inclusion on the special list/price determination.

The ESMO-MCBS is limited to solid tumours (23 drugs in our study cohort). Applying the ESMO-MCBS, 12 (52%) cancer drugs with a rebate had a high benefit and 11 (48%) had a low benefit.

Monthly treatment costs for cancer drugs with rebates based on official list prices varied between EUR 3029 palbociclib (Ibrance) and EUR 34,577 blinatumomab (Blincyto), and had a median price of EUR 5053 (Table 2). Applied rebates (at monthly treatment cost level) varied between 4% (EUR 226) and 58% (EUR 3493), with a median reduction of 27% (EUR 1538) (Table 2).

4. Discussion

The amount of drugs with granted rebates has increased substantially in recent years in Switzerland, with a majority indicated for solid or haematologic tumours. However, less than a third of these drugs had a high clinical benefit and time duration until price determination was longer compared to drugs without rebates.

Using Switzerland as an example, the results demonstrate that the amount of drugs with newly granted rebates increased from 1 in 2012 to 15 drugs with a rebate 2020, with a total of 51 drugs by 1 October 2020. Publicly accessible rebates for cancer drugs ranged from 4% and EUR 226 for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) to 58% and EUR 3493 for cobimetinib (Cotellic), with a median reduction of 27% and EUR 1538.

In most European countries, drug rebates are subject to confidentiality clauses [29]. Some countries, for example France, publishes aggregated information regarding drug rebates. Also in France, an increase of drugs with granted rebates can be observed between 2018 and 2019 [30, 31]. As in Switzerland, most drugs with rebates target solid or haematologic tumours. In France, the highest number of drugs with rebates was allocated to cancer drugs (67 drugs) with an average discount of 32%, followed by 19 immune suppressants (average rebate of 24%), 18 neurologic drugs (average discount of 19%) and 14 antidiabetic drugs (average rebate of 14%) [32].

Our results demonstrate that the granted rebate amounts vary strongly and the actual price can vary substantially from the official list price. The goal of external reference pricing is to derive a benchmark or reference price with the purpose of setting or negotiating the price of the drug in a given country in order to contain health care costs [32, 33]. It shall ensure that the price paid for a drug in a specific country does not exceed unreasonably the price paid in the comparator countries [8, 9]. However, external reference pricing only serves its purpose if the official list prices reflect the actual prices or, if at the least, the drugs with a rebate and the specific amount of the rebate are not confidential. Former studies demonstrate that confidential rebates may lead to an overpayment, thus, the increasing secrecy undermine the objective of external reference pricing [12, 16, 34]. Furthermore, lack of transparency of actual drug prices does not enable to understand whether value-based drug pricing has been applied and how limited financial resources were distributed.

By contrast to the communication of national authorities and manufacturers [35, 36], the study results demonstrate that drugs with rebates often do not have high clinical benefit for patients and duration between approval and price determination takes longer compared to drugs without rebates. These results suggest that the actual goals of drug rebates, as stated by the national authorities and manufacturers, may not be met. We believe that confidential rebates have an even higher risk for politically motivated black box-pricing. This could undermine the cost-containing drug pricing regulations in Europe, which have the goal to achieve affordable access of drugs to patients.

To enable timely access to patients, national authorities have the pressure to not only approve but also determine the drug prices for coverage by the social health insurances as quickly as possible. Therefore, the strategy of (confidential) rebates may seem at first glance a promising solution. However, the study results demonstrate – in line with the WHO's resolution [19] – that time duration between approval and price determination was longer for drugs with rebates compared to those without rebates, thus, rebates may actually hamper timely access of patients to important drugs.

Our study results support the importance of the World Health Assembly's resolution urging for transparency on actual drug prices paid by governments. Our results also indicate that the goal of the European Commission – to ensure access to affordable drugs for patients in Europe – may not be achieved with the strategy of drug rebates.

It is crucial that the limited resources are spent on innovative drugs that offer improved outcomes. To achieve this goal, one approach could be for countries to be more transparent about the actual prices and collaborate more closely. For example, the Beneluxa initiative on pharmaceutical policy – including Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Austria, and Ireland – has the goal to ensure timely access and affordability of drugs by, among other things, exchanging expertise and joint pricing negotiations for specific drugs [37].

Another consideration could be to focus on transparent value-based pricing that enable informed, systematic, and carefully considered decisions about allocations of restricted resources [7, 38]. Previous studies criticized external reference pricing since differential drug pricing between countries may actually be justified due to factors, such as supply, demand, competition, risk, reimbursement policies, government subsidies, taxes, and regulatory constraints [38].

This study has limitations. We only assessed drugs with publicly available rebates in Switzerland since other countries, such as England or France, do not publish such data. Therefore, it remains unclear if these results are also valid for other European countries. We relied on the assumption that the manufacturers started the price negotiations with the Federal Office for Public Health (national authority in Switzerland responsible for the determination of the drug price) subsequently after drug approval. This assumption my not always hold. Furthermore, our cohort covered the drugs on the special list as of 1 October 2020. There are most likely drugs approved in recent years for which price negotiations are still in process. This leads to an underestimation of the time between approval and price determination.

Using Switzerland as an example, drugs with granted rebates have increased in the past years with a focus on cancer drugs. Rebates were not limited to high-cost drugs and the amount of granted rebates varied strongly Furthermore, these drugs often did not have a high clinical value, and price determination (i.e., access to drugs) may be prolonged. The results demonstrate the importance of the WHO's resolution urging for information on actual prices paid by governments, and indicate that the goal of the European Commission – to ensure access to affordable drugs for patients in Europe – may not be achieved with the strategy of drug rebates. Improving transparency on actual drug prices and stronger cooperation between countries could help to identify drugs that should be made rapidly available across countries, help national authorities to make better informed pricing decisions, and ultimately improve access of innovative drugs to patients.

Author Contributions

DLC contributed to study design, data collection, data interpretation, and revision of the manuscript. KNV contributed to study design, data interpretation, drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors were involved at each stage of manuscript preparation and approved the final version.

Data sharing statement

All data used in this study are publicly available (see methods section).

Declaration of Interests

KNV reports grants from the Swiss Cancer Research Foundation and Swiss National Foundation (SNF) during the conduct of the study. DLC has nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Swiss Cancer Research Foundation (Krebsforschung Schweiz) and the Swiss National Foundation (SNF).

Footnotes

This study has not been submitted to another journal and has not been published in whole or in part elsewhere previously.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100050.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

German translation of abstract

References

- 1.IQVIA. Medicine use and spending in the us.https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-use-and-spending-in-the-us-review-of-2017-outlook-to-2022. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 2.Eurostat. Healthcare expenditure statistics.https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Current_healthcare_expenditure,_2012-2017_SPS20.png. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 3.OECD. Pharmaceutical spending.https://data.oecd.org/healthres/pharmaceutical-spending.htm. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 4.European Commission. A pharmaceutical strategy for Europe.https://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/strategy_en. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 5.WHO. WHO guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies, 2020.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240011878. (Accessed Jan 16, 2021). [PubMed]

- 6.Vogler S., Paris V., Ferrario A. How can pricing and reimbursement policies improve affordable access to medicines? Lessons learned from European countries. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(3):307–321. doi: 10.1007/s40258-016-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vokinger K.N., Hwang T.J., Grischott T. Prices and clinical benefit of cancer drugs in the USA and Europe: a cost–benefit analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):664–670. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30139-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.PPRI. External price referencing.https://ppri.goeg.at/node/693. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 9.Kanavos P., Frontrier A.-.M., Gill J., Kyriopoulos D. The implementation of external reference pricing within and across country borders.http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/84223/. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 10.WHO. National medicine price sources.https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/access/sources_prices/national_medicine_price_sources.pdf. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 11.De Block M. The difficulty of comparing drug prices between countries. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):e125. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogler S., Zimmermann N., Habl C., Piessnegger J., Bucsics A. Discounts and rebates granted to public payers for medicines in European countries. South Med Rev. 2012;5(1):38–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bundesamt für Gesundheit. KVG-Änderung: massnahmen zur kostendämpfung - Paket 2.https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-revisionsprojekte/kvg-aenderung-massnahmen-zur-kostendaempfung-paket-2.html. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 14.Rand L.Z., Kesselheim A.S. International reference pricing for prescription drugs in the United States: administrative limitations and collateral effects. Value Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.11.009. S1098301520345277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Technical report. Pricing of cancer medicines and its impacts, 2018.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/277190. (Accessed Jan 16, 2021).

- 16.Morgan S.G., Vogler S., Wagner A.K. Payers’ experiences with confidential pharmaceutical price discounts: a survey of public and statutory health systems in North America, Europe, and Australasia. Health Policy. 2017;121(4):354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seiter A. World Bank; Washington, D.C: 2010. A practical approach to pharmaceutical policy. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danzon P.M., Towse A. Differential pricing for pharmaceuticals: reconciling access, R&D and patents. Int J Health Care Financ Econ. 2003;3:183–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1025384819575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. World health assembly update, 2019.https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-world-health-update-28-may-2019. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 20.Bundesamt für Gesundheit. Spezialitätenliste (SL).http://www.spezialitaetenliste.ch. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 21.Swissmedic. Listen und verzeichnisse.https://www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/de/home/services/listen_neu.html. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 22.Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss.https://www.g-ba.de/english/ (accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 23.Hwang T.J., Ross J.S., Vokinger K.N., Kesselheim A.S. Association between FDA and EMA expedited approval programs and therapeutic value of new medicines: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020:m3434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherny N.I., de Vries E.G.E., Dafni U. Comparative assessment of clinical benefit using the ESMO-magnitude of clinical benefit scale version 1.1 and the ASCO value framework net health benefit score. JCO. 2019;37(4):336–349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherny N.I., Dafni U., Bogaerts J. ESMO-magnitude of clinical benefit scale version 1.1. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2340–2366. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Compendium.https://compendium.ch/. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 27.Art. 65d kvv (Verordnung über die krankenversicherung, sr 832.102).

- 28.European Central Bank. Statistical data warehouse.https://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/quickview.do?org.apache.struts.taglib.html.TOKEN=d1b44f4cb85fc394d136601046b364d7&SERIES_KEY=120.EXR.D.CHF.EUR.SP00.A&start=01-11-2011&end=&submitOptions.x=0&submitOptions.y=0&trans=N. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 29.WHO. Medicines reimbursement policies in Europe.https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/376625/pharmaceutical-reimbursement-eng.pdf. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 30.Comité Économique Des Produits De Santé. Rapport d'activité 2018.https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/ceps_rapport_d_activite_2018_20191122.pdf. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 31.Comité économique des produits de santé. Rapport d'activité 2019.https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/ceps_rapport_d_activite_2019_20201001.pdf. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 32.WHO. Glossary of pharmaceutical terms. Update 2019.https://ppri.goeg.at/sites/ppri.goeg.at/files/inline-files/PPRI_Glossary_EN_DE_ES_RU_NL_Dec2019_1.pdf. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 33.Kanavos P., Fontrier A.-.M., Gill J., Efthymiadou O. Does external reference pricing deliver what it promises? Evidence on its impact at national level. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(1):129–151. doi: 10.1007/s10198-019-01116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Pharmaceutical regulation in 15 European countries.https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/322444/HiT-pharmaceutical-regulation-15-European-countries.pdf?ua=1. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 35.https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-revisionsprojekte/kvg-aenderung-massnahmen-zur-kostendaempfung-paket-2.html.

- 36.Interpharma. Pharmaindustrie trägt bereits überproportional zur kostendämpfung bei.https://www.interpharma.ch/blog/pharmaindustrie-traegt-bereits-ueber-proportional-zur-kostendaempfung-bei/. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 37.Beneluxa. Initiative on pharmaceutical policy.https://beneluxa.org/collaboration. (Accessed Jan 12, 2021).

- 38.Fojo T., Lo A.W. Price, value, and the cost of cancer drugs. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00564-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

German translation of abstract