Abstract

Background

Accuracy of high sensitive troponin (hs-cTn) to detect coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients with renal insufficiency is not established. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognostic role of hs-cTn T and I in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Methods

All consecutive patients with chest pain, renal insufficiency (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and high sensitive troponin level were included. The predictive value of baseline and interval troponin (hs-cTnT and hs-cTnI) for the presence of CAD was assessed.

Results

One hundred and thirteen patients with troponin I and 534 with troponin T were included, with 95 (84%) and 463 (87%) diagnosis of CAD respectively. There were no differences in clinical, procedural and outcomes between the two assays. For both, baseline hs-cTn values did not differ between patients with/without CAD showing low area under the curve (AUC). For interval levels, hs-cTnI was significantly higher for patients with CAD (0.2 ± 0.8 vs. 8.9 ± 4.6 ng/mL; p = 0.04) and AUC was more accurate for troponin I than hs-cTnT (AUC 0.85 vs. 0.69). Peak level was greater for hs-cTnI in patients with CAD or thrombus (0.4 ± 0.6 vs. 15 ± 20 ng/mL; p = 0.02; AUC 0.87: 0.79–0.93); no differences were found for troponin T assays (0.8 ± 1.5 vs. 2.2 ± 3.6 ng/mL; p = 1.7), with lower AUC (0.73: 0.69–0.77). Peak troponin levels (both T and I) independently predicted all cause death at 30 days.

Conclusions

Patients with CKD presenting with altered troponin are at high risk of coronary disease. Peak level of both troponin assays predicts events at 30 days, with troponin I being more accurate than troponin T. (Cardiol J 2017; 24, 2: 139–150)

Keywords: high sensitive troponin, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease

Introduction

Accelerated atherosclerosis increases the risk of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1–4] compared with general population. Moreover, after a coronary thrombotic event, mortality rates are extremely elevated, due to peri-procedural complications and a high risk of recurrent events [5, 6] also due to complicated and technically challenging lesions [7–9].

Cardiac troponins (cTn, either the T or I iso-form) are the preferred biomarkers measured in patients with suspected AMI. Recently accuracy of high-sensitivity cTn assays (hs-cTn) have been demonstrated to be up to 96% [10]. However this study excluded patients with a reduced renal clearance, who have a greater prevalence of persistently elevated cTn compared with non-CKD patients. Many explanations have been suggested for this. While it appears unlikely that this could be related only to reduced clearance, subclinical subacute cardiac damage or even previous subclinical myocardial necrosis or left ventricular hypertrophy [11] may be causative.

In this population the diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) can be particularly challenging. Electrocardiograms are frequently abnormal because of a higher prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy and electrolyte imbalances, while persistent elevation of cTn represents a frequent finding. A high percentage of CKD patients have increased levels of troponin T and troponin I, which decreases the accuracy in predicting cardiac ischemia and diagnosing AMI [12–14].

Moreover, coronary computed tomography seems unlikely to be useful, because of high rates of coronary calcification [15].

Only a few studies [16] have tested the accuracy of hs-cTn in ACS settings, but patients included had a median clearance higher than 60 mL/min/m2, consequently limiting their applicability into everyday practice.

Methods

This study conforms to the STROBE guidelines [17].

The study was approved by the local bioethical committee; the retrospective nature of the study did not required anticipated patient consent.

Study design, setting and participants

Retrospectively all patients presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with chest pain of recent onset (less than 6 hours) in 7 centres (Turin, Thoraxcenter, Edinburgh, Bologna, Siena, Catania, Krakow) between 2009 and 2011.

Inclusion criteria were: 1) elevation of hs-cTn levels above the upper limit of reference at baseline and 2) renal clearance below 60 mL/min/m2, elaborated according to Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula [15].

Clinical variables and end points

Troponin levels assessed 3 and 6 h after ED presentation were recorded along with peak level before coronary angiography, relative increase of the second level compared to baseline and relative increase of the peak level compared to baseline. Age, gender, cardiovascular risk factors and renal clearance on admission (elaborated through MDRD formula [15]) were also collected. Cardiovascular risk factors were appraised during ED or cardiology ward stay as part of usual care, according to current guidelines for hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus (both already known and new diagnosis) [18–20]. Ejection fraction on admission was also assessed.

All these variables were collected separately for patients with high sensitive troponin T and I. All clinical, procedural and outcomes were analyzed according to tertiles of troponin.

Venous blood sampling was performed at 3 and 6 h after ED presentation, before coronary angiography and every 24 h thereafter. All samples were immediately transported to the laboratory, where plasma was separated with standard centrifugation. Every center used its own laboratory, but assays were standardized: exploited assays for troponin T were ECLIA Roche Diagnostics (with an upper reference limit [99th percentile] of 0.14 ng/L) and for troponin I high sensitive Abbott-Architect troponin (with an upper reference limit [99th percentile] of 0.26 ng/L).

Accuracy (defined as area under the curve [AUC] of the two different assays at 3 and 6 h, at the peak and their relative increase to detect coronary artery disease (CAD). Significant coronary stenosis defined as (more than 50% for left main and 70% for other epicardial coronary vessels) or thrombus, was the primary end point. Secondary end points were incidence of major adverse cardiac events at 30 days and at follow up defined as a composite end point of all cause death, cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, revascularization, target vessel revascularization and stent thrombosis defined according to ARC definitions [21, 22] and its single components.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables are presented as counts and percentage were compared with χ 2 test. Normality of troponin values was assessed through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were compared either with ANOVA (if normal distribution) or with Kruskal-Wallis (if not normal distribution). A logistic regression was performed to evaluate the independent predictive power for all cause death at 30 days exploiting all features with a significant difference (p < 0.10) at univariate analysis. To account for different length of follow up, a Cox multivariate adjustment with no parsimonious model was exploited to assess the independent predictive power of peak troponin for all cause death [23].

Area under the curve was calculated with 95% confidence interval for diagnosis of thrombus or significant coronary stenosis for first, second and peak of troponin before percutaneous coronary intervention, and for relative increase of second on first and of peak on second. Sensitivity analysis for AUC was also performed according to renal clearance, for those above and below 30 mL/min/m2. Correlation between renal function (creatinine and clearance) and troponin levels were evaluated with Pearson or Rho Sperman, according to parametric distribution.

Results

One hundred and thirteen patients with troponin I assays and 534 with troponin T were included. At angiography, a significant coronary stenosis or a thrombus was found in 95 (84%) patients with hs-cTnI measurements and in 463 (87%) patients with hs-cTnT measurements.

For troponin T patients, 120 (23%) were in the lowest tertile of troponin (less than 0.19 ng/mL), 246 (46%) in the medium (between 0.19 and 2.4 ng/mL) and 147 (28%) in the highest. For troponin I, 29 (25%) patients were in the lowest levels (less than 0.43 ng/mL), 57 (50%) between 0.43 and 21 ng/mL, and 27 (25%) in the upper.

Baseline features were similar (Table 1); in both groups the GRACE score was significantly higher in patients in the upper tertile. Ejection fraction evaluated on admission in 83% of patients showed a trend towards lower values in both groups.

Table 1. Baseline features.

| Troponin T | Troponin I | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak troponin level < 0.19 ng/mL (n = 120; 23%) | Peak troponin 0.19–2.4 ng/mL (n = 246; 46%) | Peak troponin level > 2.4 ng/mL (n = 147; 28%) | Peak troponin level < 0.43 ng/mL (n = 29; 25%) | Peak troponin 0.43–21 ng/mL (n = 57; 50%) | Peak troponin level >21 ng/mL (n = 27; 25%) | |||

| Age [years] | 76 ± 9 | 75 ± 11 | 75 ± 10 | 0.65 | 71 ± 9 | 70 ± 8 | 69 ± 10 | 0.86 |

| Female gender | 36 (30) | 55 (24) | 32 (22) | 0.06 | 9 (30) | 25 (24) | 8 (22) | 0.08 |

| Hypertension | 107 (89) | 192 (78) | 99 (67) | < 0.001 | 17 (63) | 31 (57) | 10 (46) | 0.45 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 75 (63) | 131 (53) | 62 (42) | 0.004 | 16 (57) | 34 (63) | 9 (43) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus non-insulin dependent | 52 (43) | 78 (32) | 38 (26) | 0.009 | 11 (39) | 16 (29) | 5(24) | 0.73 |

| Diabetes mellitus insulin dependent | 20 (17) | 26 (11) | 13 (9) | 0.09 | 4 (13) | 3 (12) | 3(3) | 0.86 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 48 (52) | 72 (38) | 27 (28) | 0.03 | 11 (55) | 10 (22) | 3(16) | 0.009 |

| Previous surgical revascularization | 19 (16) | 33 (14) | 12 (8) | 0.14 | 6 (28) | 4(9) | 1 (6) | 0.05 |

| Previous percutaneous revascularization | 46 (38) | 70 (28) | 27 (18) | < 0.001 | 9 (33) | 12 (25) | 1 (6) | 0.11 |

| Ejection fraction at admission | 48 ± 12 | 48 ± 11 | 43 ± 12 | 0.002 | 45 ± 15 | 44 ± 8 | 42 ± 10 | 0.84 |

| Grace score for in hospital mortality | 161 ± 35 | 175 ± 36 | 185 ± 33 | < 0.001 | 151 ± 25 | 165 ± 33 | 175 ± 323 | 0.03 |

| Creatinine at admission [mg/dL] | 1.7 ± 1.23 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 0.87 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 0.74 |

| Renal clearance (MDRD) [mL/min/1.73 m2] | 41 ± 14 | 43 ± 13 | 39 ± 14 | 0.06 | 42 ± 10 | 44 ± 13 | 46 ± 12 | 0.52 |

MDRD — Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

Overall, left main disease was diagnosed in 67 (13%) and two and three vessel coronary stenosis in 191 (41%) and 138 (25%) patients, respectively (Table 2). Most patients (403; 78%) were treated with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, while only 28 (7%) were managed conservatively.

Table 2. Procedural features.

| Troponin T | Troponin I | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak troponin level < 0.19 ng/mL (n = 120; 23%) | Peak troponin 0.19–2.4 ng/mL (n = 246; 46%) | Peak troponin level > 2.4 ng/mL (n = 147; 28%) | Peak troponin level < 0.43 ng/mL (n = 29; 25%) | Peak troponin 0.43–21 ng/mL (n = 57; 50%) | Peak troponin level >21 ng/mL (n = 27; 25%) | |||

| Significative stenosis or thrombosis | 99 (83) | 219 (89) | 132 (91) | 0.08 | 21 (72) | 53 (95) | 27 (100) | < 0.001 |

| Significative stenosis | 99 (90) | 219 (96) | 132 (96) | 0.03 | 21 (74) | 53 (90) | 26 (96) | 0.006 |

| Thrombosis of native vessel | 7(8) | 26 (14) | 44 (46) | 0.03 | 6(21) | 15 (26) | 24 (89) | < 0.001 |

| Left main disease | 14 (15) | 26 (14) | 15 (16) | 0.89 | 2(7) | 10 (18) | 0(0) | 0.039 |

| Two vessels disease | 33 (35) | 73 (38) | 40 (39) | 0.85 | 10 (34) | 29 (51) | 6 (22) | 0.034 |

| Three vessels disease | 32 (34) | 57 (30) | 34 (34) | 0.59 | 5(17) | 8 (14) | 3 (11) | 0.81 |

| Management: | 0.017 | 0.027 | ||||||

| Medical therapy | 8(7) | 13(5) | 2 (1.4) | 4(5) | 12 (21) | 1 (4) | ||

| PTCA | 84 (70) | 176 (72) | 90 (61) | 21 (58) | 40 (72) | 26 (96) | ||

| CABG | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 3(2) | 3 (11) | 5(9) | 0(0) | ||

| PTCA on left main | 8(8.7) | 15(8) | 10 (10) | 0.78 | 2(8) | 3(6) | 2(8) | 0.92 |

| PTCA on proximal descending anterior | 27 (29) | 72 (38) | 34 (35) | 0.37 | 5(19) | 17 (35) | 11 (42) | 0.19 |

| PTCA on proximal circumflex artery | 21 (23) | 52 (27) | 16 (17) | 0.13 | 3 (12) | 9 (17) | 5(19) | 0.74 |

| PTCA on proximal right coronary artery | 25 (27) | 40 (21) | 19 (20) | 0.41 | 4(15) | 15 (28) | 7(27) | 0.46 |

| Medium contrast (cc) | 303 ± 73 | 301 ± 128 | 289 ± 82 | 0.71 | 298 ± 53 | 315 ± 118 | 269 ± 72 | 0.98 |

PTCA — percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; CABG — coronary artery bypass graft

At 30 days and during the follow-up (Tables 3, 4), rates of adverse events were higher in patients in the highest tertile, mainly driven by re-infarctions, as they were after a follow up of 52 (13–70) months.

Table 3. Thirty day outcomes.

| Troponin T | Troponin I | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak troponin level < 0.19 ng/mL (n = 120; 23%) | Peak troponin 0.19–2.4 ng/mL (n = 246; 46%) | Peak troponin level > 2.4 ng/mL (n = 147; 28%) | Peak troponin level < 0.43 ng/mL (n = 29; 25%) | Peak troponin 0.43–21 ng/mL (n = 57; 50%) | Peak troponin level >21 ng/mL (n = 27; 25%) | |||

| MACE | 8(9) | 13 (8) | 9 (10) | 0.79 | 4 (14) | 13 (23) | 3 (11) | 0.34 |

| All cause death | 1 (1.2) | 4 (2.3) | 5 (5.5) | 0.18 | 1 (3) | 7(12) | 3 (11) | 0.41 |

| Cardiovascular death | 3 (3.5) | 4 (2.3) | 3 (3.2) | 0.84 | 1 (3) | 4(4) | 1 (3) | 0.12 |

| Myocardial infarction | 8(9) | 5(3) | 4 (4.3) | 0.07 | 3 (10) | 5(9) | 0(0) | 0.25 |

| Repeated PTCA | 5(6) | 2 (1.2) | 4 (4.3) | 0.09 | 1 (6) | 5(11) | 2(8) | 0.76 |

| Repeated PTCATVR | 4 (4.7) | 1 (1) | 4 (4.3) | 0.07 | 1 (6) | 4(9) | 1 (4) | 0.69 |

| Stent thrombosis: | 0.23 | 0.56 | ||||||

| Definite | 3 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (3.5) | 0(0) | ||

| Probable | 2 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | ||

| Possible | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | ||

| Acute kidney injury: | 0.29 | 0.21 | ||||||

| Risk | 22 (23) | 52 (28) | 16 (17) | 7(19) | 25 (28) | 5(14) | ||

| Injury | 18 (21) | 27 (14) | 16 (17) | 6 (20) | 18 (14) | 5(13) | ||

| Failure | 6(7) | 7(4) | 6 (6.5) | 3(2) | 7(1) | 4 (6.5) | ||

MACE — major adverse cardiac events; PTCA — percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; PTCATVR — percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty-target vessel revascularization

Table 4. Follow up outcomes.

| Troponin T | Troponin I | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak troponin level < 0.19 ng/mL (n = 120; 23%) | Peak troponin 0.19–2.4 ng/mL (n = 246; 46%) | Peak troponin level > 2.4 ng/mL (n = 147; 28%) | Peak troponin level < 0.43 ng/mL (n = 29; 25%) | Peak troponin 0.43–21 ng/mL (n = 57; 50%) | Peak troponin level >21 ng/mL (n = 27; 25%) | |||

| MACE | 11 (14) | 34 (22) | 22 (24) | 0.25 | 3 (10) | 9(16) | 4(15) | 0.78 |

| All cause death | 5 (6.5) | 17 (11.1) | 8(9) | 0.57 | 1 (3.4) | 10 (18) | 5(19) | 0.16 |

| Cardiovascular death | 2 (2.6) | 5 (3.3) | 8 (10) | 0.03 | 0(0) | 3 (4.3) | 3(4) | 0.6 |

| Myocardial infarction | 4(5) | 11 (7) | 11 (12) | 0.19 | 3 (10) | 4(7) | 1 (4) | 0.36 |

| Repeated PTCA | 5(6) | 19 (12) | 5(6) | 0.13 | 1 (4) | 4(8) | 2(6) | 0.15 |

| Repeated PTCATVR | 5(6) | 14 (9) | 4(9) | 0.76 | 0(0) | 0.54 | 0(0) | 0.26 |

| Stent thrombosis: | 0.34 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Definite | 2 (2.6) | 3(2) | 5 (5.7) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (3.5) | 0(0) | ||

| Probable | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.3) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | ||

MACE — major adverse cardiac events; PTCA — percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; PTCATVR — percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty-target vessel revascularization

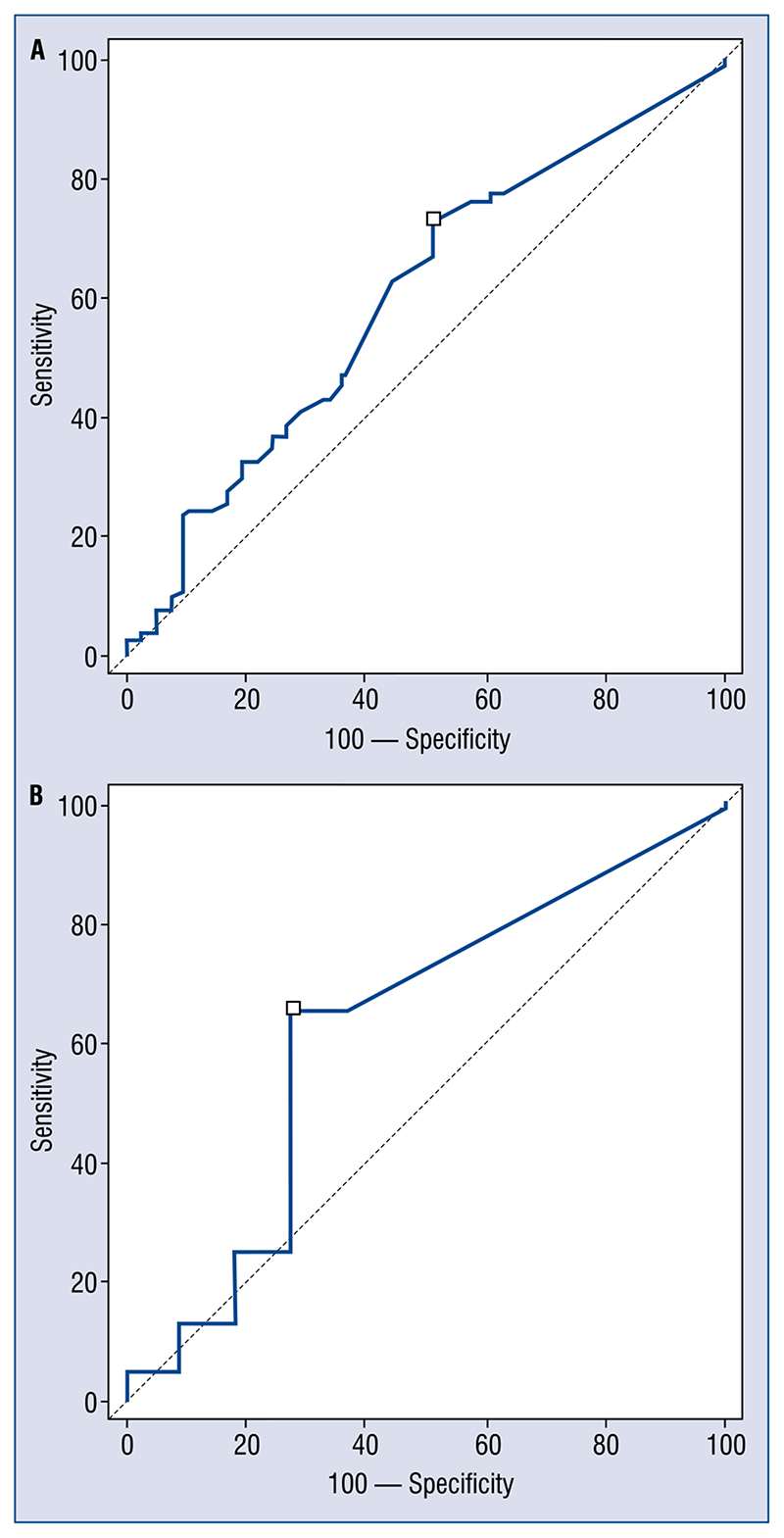

For both assays, baseline hs-cTn values were recorded after a median of 3.5 (3–6) h and did not differ between patients with or without CAD, also showed low AUCs (troponin T: AUC 0.61; 0.56–0.64; sensitivity 73; specificity 49, for patients with renal clearance between 30 and 60 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.57; 0.51–0.61; sensitivity 65; specificity 45; for patients with renal clearance less than 30 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.52; 0.45–0.64; sensitivity 59; specificity 43; troponin I: AUC 0.61; 0.52–0.71; sensitivity 69; specificity 45, for patients with renal clearance between 30 and 60 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.57; 0.51–0.61; sensitivity 65; specificity 45, for patients with renal clearance less than 30 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.60; 0.57–0.69; sensitivity 64; specificity 49) (Fig. 1A, B).

Figure 1.

A. First troponin level for patients without (on the right) and with (on the left) coronary disease. On the left troponin T; on the right troponin I [ng/mL]. Hours from presentation: 3.5 (3–6); B. Area under the curve (AUC) of first troponin level to detect thrombus or significant stenosis for troponin T on the left (AUC 0.61; 0.56–0.64; sensitivity 73; specificity 49) and for troponin I on the right (AUC 0.61; 0.52–0.71; sensitivity 69; specificity 45)

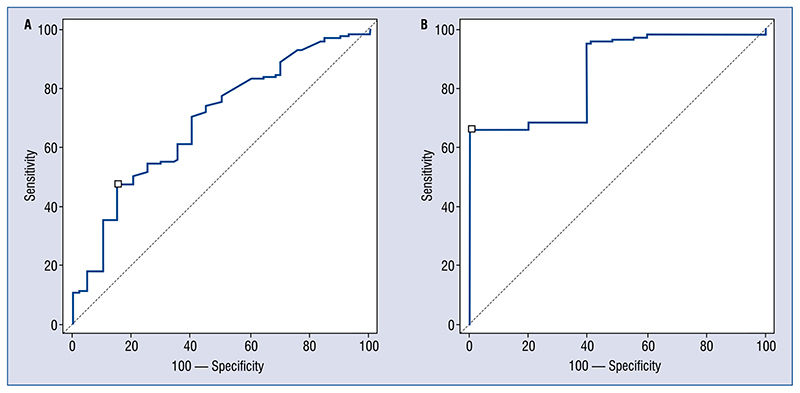

For interval levels (evaluated after 7; 5–13 h), hs-cTn I was significantly higher for patients with CAD (0.2 ± 0.8 vs. 8.9 ± 4.6 ng/mL; p = 0.04; Fig. 2A) but not troponin T (Fig. 2A): similarly AUC was more predictive for troponin I than hs-cTnT (troponin T: AUC 0.69; 0.64–0.74; sensitivity 70; specificity 56, for patients with renal clearance between 30 and 60 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.65; 0.63–0.68; sensitivity 63; specificity 49, for patients with renal clearance less than 30 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.62; 0.58–0.71; sensitivity 58; specificity 54; troponin I: AUC 0.85; 0.65–0.92; sensitivity 65; specificity 100, for patients with renal clearance between 30 and 60 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.86; 0.81–0.94; sensitivity 78; specificity 95, for patients with renal clearance less than 30 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.81; 0.59–0.85; sensitivity 64; specificity 81) (Fig. 2B). Also increase of interval on baseline level showed the same trend (AUC 0.8; 0.71–0.96 vs. AUC 0.64; 0.60–0.70; Fig. 3A).

Figure 2.

A. Second troponin level for patients without (on the right) and with (on the left) coronary disease. On the left troponin T; on the right troponin I [ng/mL]. Hours from presentation: 7 (5–13); B. Area under the curve (AUC) of second troponin level to detect thrombus or significant stenosis for troponin T on the left (AUC 0.69; 0.64–0.74; sensitivity 70; specificity 56) and for troponin I on the right (AUC 0.85; 0.65–0.92; sensitivity 65; specificity 100).

Figure 3.

A. Area under the curve (AUC) of increment of second on first troponin level to detect thrombus or significant stenosis for troponin T on the left (AUC 0.64; 0.60–0.70; sensitivity 58; specificity 69) and for troponin I on the right (AUC 0.8; 0.71–0.96; sensitivity 72; specificity 100); B. AUC of increment of peak on first troponin level to detect thrombus or significant stenosis for troponin T on the left (AUC 0.69; 0.65–0.74; sensitivity 61; specificity 72) and for troponin I on the right (AUC 0.79; 0.69–0.84; sensitivity78; specificity 75).

All these results were consistent after sensitivity analysis was performed according to level of renal clearance (Figs. 1–4).

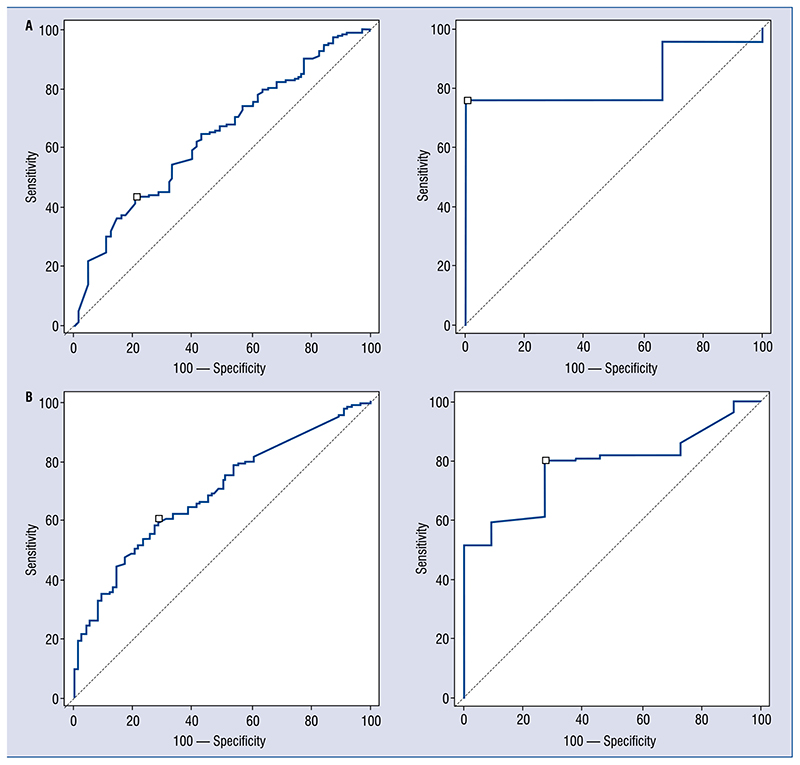

Figure 4.

A. Peak troponin level for patients without (on the right) and with (on the left) coronary disease. On the left troponin T; on the right troponin I [ng/mL]. Hours from presentation: 9.5 (6.5–14); B. AUC of peak troponin level before percutaneous coronary intervention to detect thrombus or significant stenosis for troponin T on the left (AUC 0.73; 0.69–0.77; sensitivity 83; specificity 51) and for troponin I on the right (AUC 0.87; 0.79–0.93; sensitivity 73; specificity 91); AUC — area under the curve.

Peak level (recorded after 9.5; 6.5–14 h from clinical presentation, Fig. 4A) was greater for hs-cTnI in patients with CAD or thrombus (0.4 ± 0.6 vs. 15 ± 20 ng/mL; p = 0.02), with an AUC of 0.87; on the contrary no differences were found for troponin T assays (0.8 ± 1.5 vs. 2.2 ± 3.6 ng/mL; p = 1.7), with lower AUC (troponin T: AUC 0.73; 0.69–0.77; sensitivity 83; specificity 51, for patients with renal clearance between 30 and 60 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.74; 0.65–0.81; sensitivity 84; specificity 54, for patients with renal clearance less than 30 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.74; 0.63–0.79; sensitivity 83; specificity 52; troponin I: AUC 0.87; 0.79–0.93; sensitivity 73; specificity 91, for patients with renal clearance between 30 and 60 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.88; 0.79–0.95; sensitivity 79; specificity 90, for patients with renal clearance less than 30 mL/min/m2, AUC 0.80; 0.76–0.84; sensitivity 65; specificity 88) (Fig. 4B).

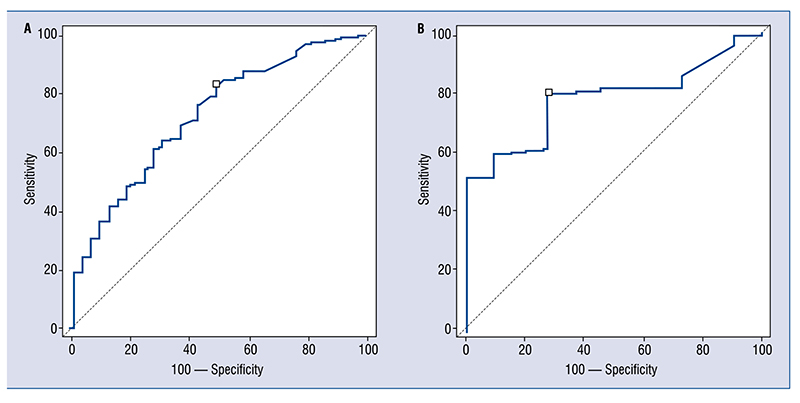

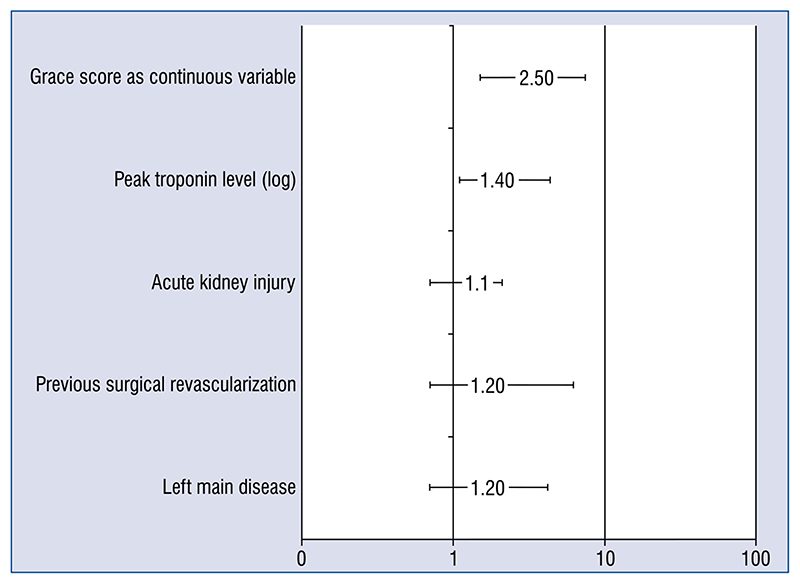

At logistic regression, two models were performed for each population; in both of them GRACE score (OR 2.5; 1.5–5) and peak troponin level (T as log of values OR 1.4; 1.1–4.4 and I OR 1.3; 1.1–2.5) were independently related to all cause death, while only ejection fraction was a predictor of long term death (OR 3; 2–4; Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Independent predictors values for 30 days all cause death. Peak troponin level (log) T:I 1.3: (1.1.2.5).

Both for troponin I and T, no significant correlation was found with renal function, evaluated with creatinine and renal clearance (Table 5).

Table 5. Correlation between troponin T and I and creatinine and renal clearance.

| Creatinine [mg/dL] | Renal clearance (MDRD) [mL/min/1.73 m2] | |

|---|---|---|

| Troponin I [ng/mL] | ||

| First level | r = 0.15; p = 0.11 | r = -0.07; p = 0.45 |

| Second level | r = -0.13; p = 0.45 | r = 0.175; p = 0.19 |

| Peak level | r = -0.16; p = 0.88 | r = 0.17; p = 0.06 |

| Troponin T [ng/mL] | ||

| First level | r = 0.07; p = 0.15 | r = -0.06; p = 0.34 |

| Second level | r = -0.13; p = 0.45 | r = -0.03; p = 0.61 |

| Peak level | r = -0.05; p = 0.56 | r = 0.32; p = 0.04 |

Pearson or Spearman Correlation (r)

Discussion

The main results of this multicenter registry are: (a) patients with CKD presenting to the ED with alterations of troponin are at high risk of coronary disease; (b) peak level of both troponin assays predicts events at 30 days; (c) troponin I may be more accurate than troponin T in this population.

High risk of coronary disease in patients with even a small reduction of renal function is well documented. In primary prevention, a recent study involving more than one million patients demonstrated an incidence of myocardial infarction similar in CKD patients compared to diabetic patients [24], introducing the concept of renal disease as another coronary heart disease equivalent. Actually CKD at its different stages is characterized by oxidative stress, inflammation, and dyslipidemia, a combination which promotes accelerated atherosclerosis [25, 26]. Oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), endothelial injury and dysfunction, and simultaneously compromise high density lipoprotein (HDL) represents the primary etiology: moreover oxidized lipids promote inflammation, thus reducing the protective function of HDL [27, 28]. These biochemical findings clinically translate into a high risk of coronary disease for these patients, which currently constitutes up to 80% in our population. It should be remembered, however, that the present paper is based on a retrospective registry: consequently a non indifferent risk of selection towards a high risk population may be possible. It could have occured at several points of the clinical decision making process, from the choice of hospitalization for the patient at ED evaluation, to that of performing coronary angiography. On the other hand, this registry represents a real life pragmatic approach, aiming to describe the risk of patients clinically depicted as “high risk”.

In an examination of the research, this is the first study to demonstrate the prognostic role of high sensitivity peak level of troponin (both T and I) in patients with CKD. The role of this elevation is well documented for non high sensitive troponin, which was predictive for short and long-term risk of death or myocardial infarction in ACS patients across all degrees of kidney disease [29–31]. Moreover no differences among various assays were recently demonstrated in subgroup analysis of CRUSADE [32], especially for patients reporting higher levels of troponin (for TnT 9% vs. 14%; for Tnl 6% vs. 14%). Similarly, in patients with preserved kidney function, hs-cTn levels correlated to mid and long term mortality [33, 34]. In the present study, prognostic value of hsTn (both T and I) was demonstrated for short term all cause death, but not all long term. Several explanations may be deduced; for these patients a slight basal elevation of troponin is very frequent, consequently limiting clinical validity of peak level [9] and moreover at follow up depressed ejection fraction, which is strictly connected to cardiac damage (that is troponin release) may confine prognostic role of hs-cTn.

High sensitive TnI was more accurate than hsTnT in detecting coronary disease. Both of them are derived from genes that are specific to the heart, and show the same accuracy and prognostic value in patients without renal disease [35, 36]. Patients tested with troponin I and T were similar both for baseline and procedural features, both for 30 days and long term outcomes (see Tables 3 and 4).

On the contrary, in the era of non high sensitivity troponin, non specific TnT elevations were demonstrated in patients with renal failure [37–39]. Many explanations have been provided, from total lack of expression of cardiac Tnl in non-cardiac tissue to less susceptibility of troponin I compared to T to proteolysis which is enhanced by uremia. In the present population, accuracy of troponin I was higher than that of T, stressing the need for an accurate choice of assays according to a specific population of interest. Performance of hs-cTnT was lower than in the recent study of Chenevier-Gobeaux [16], but median values of clearance in that study (75.3; 62.7–91.7 mL/min/1.73 m2) were significantly higher than in this study (49: 35–53), thus explaining limited performance. Moreover both for troponin T and I, accuracy was higher in patients with less severely reduced renal clearance, stressing the need to test these results in a prospective way, to increase evidence about troponin assays in patients with CKD.

Limitations of the study

This study has some limitations. Firstly, it is a retrospective study, with all the inherent risks of bias. Moreover hs-cTnT and hs-cTnI were not directly compared, but were tested with different populations. These were however, very similar in baseline characteristics, procedural features and outcomes, thus allowing indirect comparisons. These findings are supported by previous evidence on non high sensitivity troponin. Data about completeness of revascularization were not collected, although we reported about revascularization on proximal and consequently prognostic vessels. Finally we did not collect data about patients without elevated troponin levels, in order to focus on a homogeneous population.

Conclusions

Patients with CKD presenting to the ED with alterations of troponin are at high risk of coronary disease. Peak levels of both troponin assays predicts events at 30 days, but troponin I may be more accurate than troponin T in this population.

Footnotes

Contributions: The Food and Drug Administration conceived the paper and took whole responsibility of the paper. All the other authors were involved for the data collection, analysis and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Gupta S, de Lemos JA. Use and misuse of cardiac troponins in clinical practice. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;50(2):151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, Authors/Task Force Members Chairpersons, Biomarker Subcommittee, ECG Subcommittee, Imaging Subcommittee, Classification Subcommittee, Intervention Subcommittee, Trials & Registries Subcommittee, Trials & Registries Subcommittee, Trials & Registries Subcommittee, Trials & Registries Subcommittee, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG), Document Reviewers. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(16):1581–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller T, Zeller T, Peetz D, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):868–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Ascenzo F, Presutti DG, Picardi E, et al. Prevalence and non-invasive predictors of left main or three-vessel coronary disease: evidence from a collaborative international meta-analysis including 22 740 patients. Heart. 2012;98(12):914–919. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budano C, Levis M, D’Amico M, et al. Impact of contrast-induced acute kidney injury definition on clinical outcomes. Am Heart J. 2011;161(5):963–971. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Ascenzo F, Gonella A, Quadri G, et al. Comparison of mortality rates in women versus men presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(5):651–654. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang HD, Alam M, Hamzeh I, et al. Patients with severe chronic kidney disease benefit from early revascularization after acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(4):3741–3746. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bataille Y, Plourde G, Machaalany J, et al. Interaction of chronic total occlusion and chronic kidney disease in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(2):194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quadri G, D’Ascenzo F, Moretti C, et al. Diffuse coronary disease: short- and long-term outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention. Acta Cardiol. 2013;68(2):151–160. doi: 10.2143/AC.68.2.2967272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):858–867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang AYM, Lai KN. Use of cardiac biomarkers in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(9):1643–1652. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis K, Dreisbach AW, Lertora JL. Plasma elimination of cardiac troponin I in end-stage renal disease. South Med J. 2001;94(10):993–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu AHB, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, et al. NACB Writing Group, NACB Committee. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry laboratory medicine practice guidelines: use of cardiac troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide or N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide for etiologies other than acute coronary syndromes and heart failure. Clin Chem. 2007;53(12):2086–2096. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.095679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafari Fesharaki M, Alipour Parsa S, Nafar M, et al. Serum troponin I level for diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome in patients with chronic kidney disease. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2016;10(1):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Ascenzo F, Cerrato E, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Coronary computed tomographic angiography for detection of coronary artery disease in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(8):782–789. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Meune C, Freund Y, et al. Influence of age and renal function on high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T diagnostic accuracy for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(12):1701–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. http://www.strobe-statement.org/index.phpPid=available-checklists.

- 18. http://mdrd.com/

- 19.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology, Task Force Members. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2013;34(28):2159–2219. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2889–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones AG, Knight BA, Baker GC, et al. Practical implications of choice of test in National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance for the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2013;30(1):126–127. doi: 10.1111/dme.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thygesen K, Mair J, Giannitsis E, et al. Study Group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care. How to use high-sensitivity cardiac troponins in acute cardiac care. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(18):2252–2257. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Academic Research Consortium. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115(17):2344–2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Ascenzo F, Cavallero E, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Use and misuse of multivariable approaches in interventional cardiology studies on drug-eluting stents: a systematic review. J Interv Cardiol. 2012;25(6):611–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2012.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: a population-level cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380(9844):807–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navab KD, Elboudwarej O, Gharif M, et al. Chronic inflammatory disorders and accelerated atherosclerosis: chronic kidney disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(1):17–20. doi: 10.2174/138161211795049787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaziri ND, Navab M, Fogelman AM. HDL metabolism and activity in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:287–296. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Ascenzo F, Agostoni P, Abbate A, et al. Atherosclerotic coronary plaque regression and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events: a meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. Atherosclerosis. 2013;226(1):178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclero-sis.2012.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. Mechanisms of disease: proatherogenic HDL--an evolving field. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2(9):504–511. doi: 10.1038/ncpend-met0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryu DR, Park JT, Chung JH, et al. A more appropriate cardiac troponin T level that can predict outcomes in end-stage renal disease patients with acute coronary syndrome. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52(4):595–602. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.4.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricchiuti V, Voss EM, Ney A, et al. Cardiac troponin T isoforms expressed in renal diseased skeletal muscle will not cause false-positive results by the second generation cardiac troponin T assay by Boehringer Mannheim. Clin Chem. 1998;44(9):1919–1924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apple FS, Murakami MM, Pearce LA, et al. Predictive value of cardiac troponin I and T for subsequent death in end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 2002;106(23):2941–2945. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000041254.30637.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melloni C, Alexander KP, Milford-Beland S, et al. Crusade Investigators. Prognostic value of troponins in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes and chronic kidney disease. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31(3):125–129. doi: 10.1002/clc.20210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reichlin T, Twerenbold R, Reiter M, et al. Introduction of high-sensitivity troponin assays: impact on myocardial infarction incidence and prognosis. Am J Med. 2012;125(12):1205–1213.:e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balmelli C, Meune C, Twerenbold R, et al. Comparison of the performances of cardiac troponins, including sensitive assays, and copeptin in the diagnostic of acute myocardial infarction and long-term prognosis between women and men. Am Heart J. 2013;166(1):30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coudrey L. The troponins. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(11):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.11.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidenreich PA, Alloggiamento T, Melsop K, et al. The prognostic value of troponin in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(2):478–485. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin GS, Becker BN, Schulman G. Cardiac troponin-I accurately predicts myocardial injury in renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13(7):1709–1712. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.7.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li D, Keffer J, Corry K, et al. Nonspecific elevation of troponin T levels in patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Biochem. 1995;28(4):474–477. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(95)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]