Abstract

Metabolic engineering aims at modifying the endogenous metabolic network of an organism to harness it for a useful biotechnological task, e.g., production of a value-added compound. Several levels of metabolic engineering can be defined and are the topic of this review. Basic ‘copy, paste and fine-tuning’ approaches are limited to the structure of naturally existing pathways. ‘Mix and match’ approaches freely recombine the repertoire of existing enzymes to create synthetic metabolic networks that are able to outcompete naturally evolved pathways or redirect flux towards non-natural products. The space of possible metabolic solution can be further increased through approaches including ‘new enzyme reactions’, which are engineered on the basis of known enzyme mechanisms. Finally, by considering completely ‘novel enzyme chemistries’ with de novo enzyme design, the limits of nature can be breached to derive the most advanced form of synthetic pathways. We discuss the challenges and promises associated with these different metabolic engineering approaches and illuminate how enzyme engineering is expected to take a prime role in synthetic metabolic engineering for biotechnology, chemical industry and agriculture of the future.

Introduction

The introduction of the concept of ‘total synthesis’ by Friedrich Wöhler 1828 [1] was one of the milestones in chemistry [2]. The possibility to create non-natural compounds, color pigments, drugs, materials and catalysts from simple chemical building blocks catapulted chemistry into one of the key sciences of the 20th century and to a driving force of our modern world.

It has been one of the ultimate goals in biology to achieve the same conceptual and synthetic level as reached in chemistry, ever since the principle of ‘metabolic engineering’ was developed in the early 1990s. Yet, cells are still far from being ‘little chemical factories’ [3] and metabolic engineering has been limited in its synthetic capabilities so far, relying mainly on the transplanting known pathways to a new host followed by optimization.

To realize the full potential of metabolic engineering new strategies and approaches are required. Recent advances in molecular genetics, computational biology, and protein design open the chance to move metabolic engineering from a ‘tinkering science’ towards a truly synthetic discipline. Through combination of these approaches we will no longer be limited to existing pathways and enzymes but be able to design entirely novel pathways in a rational fashion and thereby realize synthetic metabolism. Here, we classify different metabolic engineering efforts according to the extent that they go beyond existing metabolic network structures. We provide an experimental roadmap towards achieving the synthetic metabolism goal, define the challenges and chances of de novo pathway design, and discuss possible future applications of synthetic metabolism.

Five levels of metabolic engineering

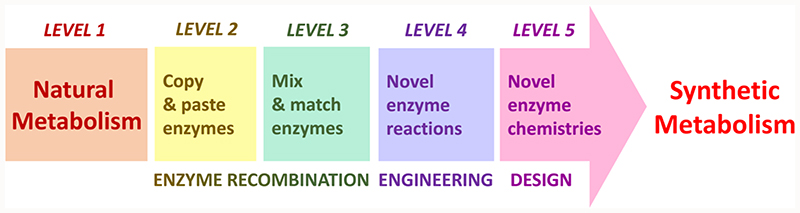

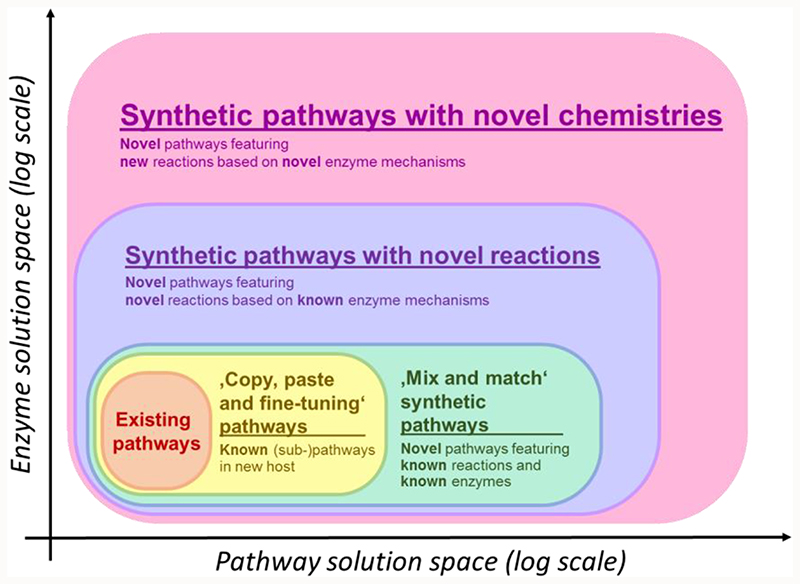

Several levels of metabolic engineering can be defined according to the synthetic character and the resulting biochemical solution space (Figure 1 and Table 1). Basic metabolic engineering efforts operate on the level of existing pathways within their natural host. Here, pathway productivity is improved only through gene deletions and overexpressions. In more advanced ‘copy, paste and fine tuning’ approaches, existing (sub-)pathways are introduced to another host, often a biotechnologically relevant strain, where they are eventually further modified by replacing individual enzymes. This results in relatively small changes to the overall metabolic structure supporting faster kinetics, an improved thermodynamic profile, or a more sustainable cofactor use. For example, in a pathway for n-butanol production, expressed in E. coli, substituting the thermodynamically limiting acetoacetyl-Coa synthetase with an irreversible acetyl-CoA:malonyl-CoA acetyltransferase (decarboxylating) substantially improved product titers [4]. Such mild tinkering, however, does not alter the basic structure of the engineered pathways.

Figure 1. The five different levels of metabolic engineering as defined in this review.

The enzyme solution space describes the number of possible enzymes reactions available for a given strategy while the pathway solution space corresponds to the number of possible pathways that can be constructed. While level 1, 2 and 3 metabolic engineering efforts do not differ in enzyme solution space, because they all rely on known enzymes, level 4 and 5 metabolic engineering efforts provide new enzymes created through enzyme engineering or de novo-design.

Table 1. Definitions, features and examples for the five different levels of metabolic engineering.

| Definition | Typical feature | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Optimize existing pathway in natural host | Knock out and overexpression of individual genes in natural host | Calvin cycle for CO2-fixation: overexpresssion of transketolase to increase flux [61] |

| Level 2 | Transfer and exchange of known (sub-)pathways in new host | Natural route replaced or modified with better-performing reactions | T ransfer of Calvin cycle for CO2-fixation into E. coli to allow for sugar synthesis from CO2 [62] |

| Level 3 | Novel pathways created from known reactions | Non-natural route constructed from natural enzymes | MOG pathway for CO2-fixation: recombination of known enzymes into a synthetic pathway [6] |

| Level 4 | Novel pathways created from novel reactions that are based on known enzvme mechanisms | Non-natural route containing enzymes of modified substrate specificity | CETCH cycle for CO2-fixation: recombination of known enzymes and engineered enzymes with new substrate and reaction specificities into a synthetic pathway [13] |

| Level 5 | Novel pathways created from novel reactions that are based on novel enzymatic mechanisms | Non-natural route containing de novo designed enzymes | A CO2-fixation cycle based on an not-yet developed Ni-Ga cofactor in an not-yet evolved artificial metalloprotein |

In contrast to above strategies that mainly build on existing pathways, ‘mix and match’ approaches expand the metabolic solution space. In these efforts, existing enzymes that are not known to work together in nature are integrated into synthetic pathways to perform a given metabolic task with higher efficiency or novel functionality. Recent examples are a designer pathway for the biosynthesis of propane from glucose [5], a non-oxidative glycolysis for complete carbon conservation [6], or artificial C1 assimilation pathways that were designed by freely recombining existing enzyme reactions, even though these routes were not experimentally realized so far [6,7]. Such combinatorial design efforts can be automatized by software programs [8,9], though it is important to keep in mind that databases such as KEGG are not complete relative to the existing literature. To identify the most promising pathways out of many different possible routes, a comprehensive pathway analysis is recommended. Such an analysis compares different pathway candidates according to physicochemical properties, including resources consumption, thermodynamic feasibility, kinetic proficiency, toxicity and hydrophobicity of intermediates, as well as overlap with endogenous metabolism [10].

The main advantage of the ‘mix and match’ approach is that without the need to evolve novel reactions, a wide array of potential pathways can be identified. Yet, to fully tap into the (bio)chemical solution space, more synthetic metabolic engineering efforts aim at implementing pathways that include new reactions that are not known to exist in nature through enzyme engineering and de novo-enzyme design (see below). So far, only a handful of studies have implemented synthetic pathways that involve novel catalytic transformations. These rare examples include a synthetic route to 1,4-butanediol [11], a novel didanosine biosynthetic pathway [12] and a synthetic pathway for the fixation of carbon dioxide [13]. These examples demonstrate how metabolic engineering can access novel products and non-natural pathways of improved efficiency with new reactions, paving the way towards truly ‘synthetic metabolism’, in which designer pathways are first drafted based on rational considerations. Only afterwards is the actual route realized experimentally by identifying, designing and recombining individual enzyme reactions.

Designer reactions for designer pathways

‘New reactions’ for synthetic pathways can be realized in several ways. One approach considers the backward reactions of enzymes that are mistakenly considered as irreversible, but which can actually sustain in vivo flux in both directions. While this approach is restricted to a small number of enzymes, it can offer a wide array of new options. For example, the ‘irreversible’ pyruvate formate-lyase was recently found to support formate assimilation in vivo [14], which allows multiple promising formate pathways to be established around this reaction [7]. Similarly, by acknowledging that the glycine cleavage system [15] is fully reversible in vivo [16], a new approach for carbon or formate assimilation could be developed [7].

Another way to find ‘new reactions’ is based on exploring and extending the substrate repertoire of existing enzymes. These strategies are promising if prospectives substrates are structurally related to the native substrates of known enzymes. In many enzyme superfamilies, only a limited amount of representatives have been experimentally characterized so far. This means that a sought enzyme activity might already naturally exist in an enzyme superfamily, only it was not discovered yet. For instance, the family of B12-dependent acyl-CoA mutases was for a long time only thought to consist of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase. However, very recently, enzymes specific also for ethylmalonyl-CoA [17], isobutyryl-CoA, 2-hydroxybutyryl-CoA, and most recently isovaleryl-CoA [18] were identified. New tools like sequence similarity and genome neighborhood networks, as well as advanced structure prediction and docking tools will help to identify promising candidates to be tested experimentally [19–23].

Even if a sought reaction does not exist naturally, many enzymes are known to be intrinsically promiscuous, so that the reaction might be established (or ‘extended’) from a side-reaction of a given enzyme. Such promiscuous activity can provide an excellent starting point for further engineering to improve catalytic efficiency, especially when assisted by structural information [24]. Isovaleryl-CoA mutase activity was engineered from a side-reaction of isobutyryl-CoA mutase, providing novel options for the synthesis of branched C4 and C5 building blocks [18]. The naturally promiscuous CoA ligase matB was further engineered to feed novel substrates into polyketide biosynthetic assembly lines, giving rise to novel natural products [25,26]. Screening and structurally guided mutagenesis was used to provide carboxylating enoyl-CoA ester reductases (ECR) that can deliver novel building blocks for polyketide biosynthesis [27,28]. Promiscuous enzymes were also used to establish metabolic routes for the production of non-natural lactate-based polymers and esters in Ralstonia eutropha [29,30] and Escherichia coli [31,32]. Similarly, harnessing the intrinsic promiscuous catalytic potential of squalene hopene cyclases could provide new ways towards valuable cyclohexanoid monoterpenes if successfully integrated into metabolism [33].

Exploring the natural biochemical space and the promiscuity of enzymes will potentially cover many of the ‘new reactions’ required in synthetic pathway design. Yet, in some cases, it will be necessary also to design a required enzyme reaction de novo. An example is an artificial ‘retro-aldolase’ that was created through computational design and experimental evolution and can directly use acetone as donor in contrast to natural aldolases, [34]. Even more progressive are efforts that give access to completely novel enzyme chemistries, which have not evolved in nature. A ‘formolase enzyme’ that could form the basis for a novel formaldehyde assimilation pathway was conceived by computational design [35].The metathesis reaction that was exclusively used in synthetic chemistry so far was successfully functionalized for biology through the directed evolution of an artificial metalloenzyme [36], which opens the chance to harness the principle of metathesis also for metabolic engineering. Very recently an enzyme that is catalyzes silicon-carbon bonds was evolved, providing a first step towards engineering the bio-technological production of organosilicon compounds [37]. These pioneering studies provide exciting examples how the field of enzyme design will be able to provide many more novel catalysts for synthetic metabolism in future.

In silico-analysis of synthetic metabolic routes

For the de novo design of synthetic pathways it is essential to confirm that no thermodynamic or kinetic barriers are expected to constraint the activity of the new pathways. While it is difficult to obtain reliable estimation for the kinetics of yet to be evolved new reactions, the thermodynamic profile of a pathway can be calculated with rather high precision, even for pathways whose components are not fully defined yet [13,38–40]. Such computational analyses will also need to take into account barriers that are generated by the sequential operation of several enzymes. Even though each reaction in a sequence might be thermodynamically feasible by itself, their sequential combination might lead to severe energetic barriers [40].

Another problem is the possibility of an overlap between the new pathway and endogenous metabolism. Such an overlap can result in an unregulated rewiring of cellular metabolic fluxes, which could have a deleterious effect on growth rate and yield. Alternatively, and equally problematic is the ability of endogenous metabolic fluxes to suppress the activity of synthetic pathways; especially if one of the pathway enzymes operates in the reverse direction under normal cell conditions. Uncontrolled drainage of pathway intermediates through other reactions, especially by enzymes in central carbon metabolism may also limit pathway activity. It is therefore important to analyze the compatibility of the novel pathways with endogenous metabolism prior to the in vivo implementation stage; this could be, at least partially, achieved by applying constrained based modeling strategies, such as flux balance analysis [6].

Challenges during implementation of synthetic metabolism

One of the biggest experimental challenges in realizing synthetic metabolic routes is the recombination of enzymes from very different biological backgrounds with no common evolutionary and physiological history into one pathway. This could result in sub optimal kinetics that could substantially limit the efficiency of the novel pathways. Another major difficulty in expressing novel enzymes and pathways within a non-native host is the fact that enzymes in the cell are expected to face metabolites to which they were never exposed in their native metabolic context. This can result in a cross-inhibition of a given enzyme by the reaction products of other pathway enzymes, or cause undesired side reactions of a given enzymes with other pathway intermediates, resulting in the formation of inhibitory side-products or dead-end metabolites [13,41]. Consequently, it is important to include appropriate mitigation strategies – ‘hermeting strategies’ (from Hermes, god of the travelers and crossroads)–into synthetic pathway design. Generally it can be anticipated that the more “synthetic” a pathway is, the more important it might become to include such strategies into pathway design.

An obvious strategy to minimize side reactions is to replace promiscuous enzymes with more specific isoenzymes or homologs. Alternatively, promiscuous enzyme can be improved by enzyme engineering to increase the discrimination factor between the desired reaction and an undesired side-reaction [13]. Another solution is to apply ‘metabolic proofreading’. This strategy includes the addition of auxiliary enzymes to the core sequence of a given synthetic pathway. These proofreading enzymes are not part of the actual pathway, but serve in removing toxic side products or recycling dead-end metabolites. Although metabolic proofreading and scavenging mechanisms apparently exist in naturally evolved pathways [42–47], these concepts have been largely neglected in synthetic metabolism design so far. However, through the combination of metabolic proofreading and enzyme redesign, the activity of a synthetic in vitro CO2-fixation pathway was improved by more than an order of magnitude [13]. Likewise, implementing a pathway for recycling the dead-end metabolite erythrose-4-phosphate was essential to establish an in vitro pathway for the conversion of glucose into polyhydroxybutyrate [48].

Another approach to bypass deleterious overlap with central metabolism is to spatially confine synthetic pathways or parts thereof. Through the use of microcompartments pathway enzymes and intermediates can be insulated from the rest of cellular metabolism [49]. This approach has an additional advantage if a pathway intermediate is reactive and can damage the cellular machinery. Alternatively, synthetic protein scaffolds can keep pathway enzymes at near proximity, thereby increasing the effective concentration of intermediates [50,51].

Opportunities for synthetic metabolic pathways

Despite the challenges, there are many advantages for realizing synthetic metabolism. Generally this typically takes the form of a metabolic by-pass or the redirection of metabolic flux towards end-products that do not naturally accumulate in cultures of the chosen biotechnological host. By freely combining existing and novel enzymatic reactions from various biological sources, optimal routes for a metabolic task can be drafted that allow to overcome any historical and ecological constraints of natural pathway evolution (i.e., the serendipity of enzymes coming together in time and space). Combining an ACP-fatty acid thioesterase from plants with an engineered, chimeric monooxygenase allowed to establish a de novo pathway for ω-hydroxy octanoic acid production in E. coli [52]. In a bioretrosynthetic approach, a pathway for the production of non-natural compound didanosine was developed [12]. Finally, through metabolic retrosynthesis, artificial pathways for CO2-fixation were drafted that are up to 30% more energy efficient compared to natural existing carbon fication routes, such as the Calvin cycle of plants, algae and cyanobacteria [6,13].

While the implementation of non-natural, synthetic biochemical routes in living organisms poses a challenge because of potential interference with natural metabolism and the challenge of finding or engineering suitable catalysts, non-natural pathways also bear the chance that their intermediates can be completely decoupled from central metabolism and the genetic program of the cell. Thus, their implementation might actually prove easier from a physiological or regulatory point of view. In efforts to improve production of the terpenoid amorphadiene in E. coli, for instance, the transplantation of the mevalonate-isoprenoid route from yeast was more successful than classical engineering of the native E. coli deoxyxylulose 5- phosphate (DXP) isoprenoid pathway. Most probably, because the DXP pathway’s native regulatory elements and feedback loops are deeply rooted in E. coli and could be circumvented by the non-native mevalonate-isoprenoid route that does not interact with the regulatory machinery of the cell [53].

Future applications for synthetic metabolic pathways

For a future sustainable economy that is independent of fossil carbon, the capture and utilization of CO2 will be crucial [54]. Designer pathways for the optimal and direct conversion of CO2 into value-added products or feedstocks could provide alternative solutions to conventional biomass production via photosynthesis [6,13,41,55]. This also includes a reconsideration of current production processes in the chemical industry, which are still based on petrochemically-derived feedstocks, but might be shifted to and fueled by synthetic pathways in the future (e.g. an extended formate or methanol metabolism [7,56,57]). Another challenge relates to agricultural productivity, which needs to be increased to feed a growing world population. So far, many efforts focused on improving natural existing CO2-fixation pathways and enzymes in plants [58]. Through synthetic metabolism, however, novel options could be provided, such as synthetic CO2-fixation pathways or photorespiration bypasses of higher efficiency [58–60]. Such novel solutions are currently explored by several laboratories and initiatives, including ours. The future will tell whether synthetic metabolism can indeed provide viable solutions for these grand social, economic and environmental challenges of the future.

Highlights.

Multiple levels of metabolic engineering can be defined, from ‘copy and paste’ to various forms of ‘synthetic metabolism’

The biochemical solution space for ‘synthetic metabolism’ can be increased by designing and evolving new enzyme reactions and chemistries.

Implementation of synthetic pathways is challenged by interference with endogenous metabolism, side-reactions and dead-end metabolites.

Integration of ‘hermeting strategies’ into synthetic pathway design may help to overcome these challenges.

Global challenges could be addressed if we harness synthetic metabolism to its fullest extent

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Research Council Grant 637675 (‘SYBORG’), FET-Open Grant 686330 (‘FutureAgriculture’), and the Max-Planck-Society.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Wöhler F. Ueber künstliche Bildung des Harnstoffs. Ann Phys Chem. 1828;88:253–256. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolaou KC, Vourloumis D, Winssinger N, Baran PS. The Art and Science of Total Synthesis at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2000;39:44–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolston BM, Edgar S, Stephanopoulos G. Metabolic engineering: past and future. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2013;4:259–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061312-103312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen CR, Lan EI, Dekishima Y, Baez A, Cho KM, Liao JC. Driving forces enable high-titer anaerobic 1-butanol synthesis in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2905–2915. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03034-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kallio P, Pasztor A, Thiel K, Akhtar MK, Jones PR. An engineered pathway for the biosynthesis of renewable propane. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4731. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Bogorad IW, Lin TS, Liao JC. Synthetic non-oxidative glycolysis enables complete carbon conservation. Nature. 2013;502:693–697. doi: 10.1038/nature12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bar-Even A, Noor E, Lewis NE, Milo R. Design and analysis of synthetic carbon fixation pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907176107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bar-Even A. Formate Assimilation: The Metabolic Architecture of Natural and Synthetic Pathways. Biochemistry. 2016;55:3851–3863. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigo G, Carrera J, Prather KJ, Jaramillo A. DESHARKY: automatic design of metabolic pathways for optimal cell growth. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2554–2556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbonell P, Parutto P, Baudier C, Junot C, Faulon JL. Retropath: automated pipeline for embedded metabolic circuits. ACS Synth Biol. 2014;3:565–77. doi: 10.1021/sb4001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bar-Even A, Flamholz A, Noor E, Milo R. Rethinking glycolysis: on the biochemical logic of metabolic pathways. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:509–517. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yim H, Haselbeck R, Niu W, Pujol-Baxley C, Burgard A, Boldt J, Khandurina J, Trawick JD, Osterhout RE, Stephen R, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:445–452. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birmingham WR, Starbird CA, Panosian TD, Nannemann DP, Iverson TM, Bachmann BO. Bioretrosynthetic construction of a didanosine biosynthetic pathway. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:392–399. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **13.Schwander DM, Schada von Borzyskowski L, Burgener S, Cortina NS, Erb TJ. A synthetic pathway for the fixation of carbon dioxide in vitro. Science. 2016;354:900–904. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5237. [ Reports on the design and realization of the CETCH cycle, a synthetic CO2-fixation pathway consisting of 17 different enzymes from nine different organisms of all three domains of life. The pathway was drafted by metabolic retrosynthesis and optimized in several rounds using enzyme engineering and metabolic proofreading, representing a level 4 metabolic engineering effort. ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zelcbuch L, Lindner SN, Zegman Y, Vainberg Slutskin I, Antonovsky N, Gleizer S, Milo R, Bar-Even A. Pyruvate Formate-Lyase Enables Efficient Growth of Escherichia coli on Acetate and Formate. Biochemistry. 2016;55:2423–2426. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douce R, Bourguignon J, Neuburger M, Rebeille F. The glycine decarboxylase system: a fascinating complex. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maaheimo H, Fiaux J, Cakar ZP, Bailey JE, Sauer U, Szyperski T. Central carbon metabolism of Saccharomyces cerevisiae explored by biosynthetic fractional (13)C labeling of common amino acids. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2464–2479. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erb TJ, Retey J, Fuchs G, Alber BE. Ethylmalonyl-CoA mutase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides defines a new subclade of coenzyme B12-dependent acyl-CoA mutases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32283–32293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitanishi K, Cracan V, Banerjee R. Engineered and Native Coenzyme B12-dependent Isovaleryl-CoA/Pivalyl-CoA Mutase. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:20466–20476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.646299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao S, Sakai A, Zhang X, Vetting MW, Kumar R, Hillerich B, San Francisco B, Solbiati J, Steves A, Brown S, et al. Prediction and characterization of enzymatic activities guided by sequence similarity and genome neighborhood networks. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.03275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *20.Gerlt JA, Bouvier JT, Davidson DB, Imker HJ, Sadkhin B, Slater DR, Whalen KL. Enzyme Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST): A web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854:1019–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.04.015. [ Description of a novel online tool that generates sequence similartiy networks for the detailed analysis of enzyme super families. This tool allows to predict and detect novel reactions within an enzyme super family ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang H, Carter MS, Vetting MW, Al-Obaidi N, Patskovsky Y, Almo SC, Gerlt JA. A General Strategy for the Discovery of Metabolic Pathways: d-Threitol, l-Threitol, and Erythritol Utilization in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14570–14573. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Steffen-Munsberg F, Vickers C, Kohls H, Land H, Mallin H, Nobili A, Skalden L, van den Bergh T, Joosten H-J, Berglund P, et al. Bioinformatic analysis of a PLP-dependent enzyme superfamily suitable for biocatalytic applications. Biotech Adv. 2015;33:566–604. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.12.012. [ Detailed description of how to analyze structure-function relationship in an enzyme superfamily examplified with PLP-dependent enzymes, and in particular class III transaminases. ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stiel AC, Nellen M, Höcker B. PocketOptimizer and the Design of Ligand Binding Sites. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1414:63–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3569-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS. Enzyme promiscuity: a mechanistis and evolutionary perspective. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:471–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-030409-143718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes AJ, Keatinge-Clay A. Enzymatic extender unit generation for in vitro polyketide synthase reactions: structural and functional showcasing of Streptomyces coelicolor MatB. Chem Biol. 2011;18:165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crosby HA, Rank KC, Rayment I, Escalante-Semerena JC. Structure-guided expansion of the substrate range of methylmalonyl coenzyme A synthetase (MatB) of Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:6619–6629. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01733-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peter DM, Schada von Borzyskowski L, Kiefer P, Christen P, Vorholt JA, Erb TJ. Screening and Engineering the Synthetic Potential of Carboxylating Reductases from Central Metabolism and Polyketide Biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:13457–13461. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Mori T, Zheng Q, Awakawa T, Yan Y, Liu W, Abe I. Rational Control of Polyketide Extender Units by Structure-Based Engineering of a Crotonyl-CoA Carboxylase/Reductase in Antimycin Biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:13462–13465. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SJ, Jang YA, Lee H, Park AR, Yang JE, Shin J, Oh YH, Song BK, Jegal J, Lee SH, et al. Metabolic engineering of Ralstonia eutropha for the biosynthesis of 2-hydroxyacid-containing polyhydroxyalkanoates. Metab Eng. 2013;20:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochi A, Matsumoto K, Ooba T, Sakai K, Tsuge T, Taguchi S. Engineering of class I lactate-polymerizing polyhydroxyalkanoate synthases from Ralstonia eutropha that synthesize lactate-based polyester with a block nature. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:3441–3447. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi SY, Park SJ, Kim WJ, Yang JE, Lee H, Shin J, Lee SY. One-step fermentative production of poly(lactate-co-glycolate) from carbohydrates in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:435–440. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez GM, Tashiro Y, Atsumi S. Expanding ester biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:259–265. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammer SC, Marjanovic A, Dominicus JM, Nestl BM, Hauer B. Squalene hopene cyclases are protonases for stereoselective Brønsted acid catalysis. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:121–126. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obexer R, Pott M, Zeymer C, Griffiths AD, Hilvert D. Efficient laboratory evolution of computationally designed enzymes with low starting activities using fluorescence-activated droplet sorting. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2016;29:355–366. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzw032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **35.Siegel JB, Smith AL, Poust S, Wargacki AJ, Bar-Even A, Louw C, Shen BW, Eiben CB, Tran HM, Noor E, et al. Computational protein design enables a novel one-carbon assimilation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3704–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500545112. [ Describes efforts to create a pathway for the conversion of formaledehyde into dihydroxyacetone. To that end, a novel enzyme ‘formolase’ was computationally designed and experimentally demonstrated. This work represents one of the rare level 5 metabolic engineering approaches. ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36.Jeschek M, Reuter R, Heinisch T, Trindler C, Klehr J, Panke S, Ward TR. Directed evolution of artificial metalloenzymes for in vivo metathesis. Nature. 2016;537:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature19114. [ The metathesis reaction is an organometallic double-bond exchange reaction used in the chemical industry without any equivalent in nature so far. Here, the authors sucessfully created an artifical metalloenzyme that is able to catalyze a metathesis reaction in vivo and further improved its activity byexperimental evolution. ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *37.Kan JBS, Lewis RD, Chen K, Arnold FH. Directed evolution of cytochrome c for carbon-silicon bond formation: Bringing silicon to life. Science. 2016;354:1048–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6219. [ A cyctochrome c from Rhodothermus marinus was shown to catalyze formation of carbon-silicon bonds. The enzyme was further improved through active site mutagenesis. ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noor E, Bar-Even A, Flamholz A, Lubling Y, Davidi D, Milo R. An integrated open framework for thermodynamics of reactions that combines accuracy and coverage. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2037–2044. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noor E, Haraldsdottir HS, Milo R, Fleming RM. Consistent estimation of Gibbs energy using component contributions. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1003098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noor E, Bar-Even A, Flamholz A, Reznik E, Liebermeister W, Milo R. Pathway thermodynamics highlights kinetic obstacles in central metabolism. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattozzi M, Ziesack M, Voges MJ, Silver PA, Way JC. Expression of the sub-pathways of the Chloroflexus aurantiacus 3-hydroxypropionate carbon fixation bicycle in E. coli: Toward horizontal transfer of autotrophic growth. Metab Eng. 2013;16:130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Schaftingen E, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Linster CL. Enzyme complexity in intermediary metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38:721–727. doi: 10.1007/s10545-015-9821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veiga-da-Cunha M, Chevalier N, Stroobant V, Vertommen D, Van Schaftingen E. Metabolite proofreading in carnosine and homocarnosine synthesis: molecular identification of PM20D2 as beta-alanyl-lysine dipeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:19726–19736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.576579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linster CL, Noel G, Stroobant V, Vertommen D, Vincent MF, Bommer GT, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Van Schaftingen E. Ethylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase, a new enzyme involved in metabolite proofreading. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42992–43003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linster CL, Van Schaftingen E, Hanson AD. Metabolite damage and its repair or pre-emption. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:72–80. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collard F, Baldin F, Gerin I, Bolsée J, Noёl G, Graff J, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Stroobant V, Vertommen D, Houddane A, et al. A conserved phosphatase destroys toxic glycolytic side products in mammals and yeast. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:601–607. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang L, Khusnutdinova A, Nocek B, Brown G, Xu X, Cui H, Petit P, Flick R, Zallot R, Balmant K, et al. A family of metal-dependent phosphatases implicated in metabolite damage-control. Nat Chem Biol. 12:621–627. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **48.Opgenorth PH, Korman TP, Bowie JU. A synthetic biochemistry module for production of bio-based chemicals from glucose. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:393–395. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2062. [ Describes a synthetic pathway consisting of 18 enzymes that convert glucose into polyhydroxybutaryte in vitro. One of the first studies that consequently uses metabolic proofreading as strategy to overcome side-reactions in synthetic patwhays ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cai F, Sutter M, Bernstein SL, Kinney JN, Kerfeld CA. Engineering bacterial microcompartment shells: chimeric shell proteins and chimeric carboxysome shells. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;4:444–453. doi: 10.1021/sb500226j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castellana M, Wilson MZ, Xu Y, Joshi P, Cristea IM, Rabinowitz JD, Gitai Z, Wingreen NS. Enzyme clustering accelerates processing of intermediates through metabolic channeling. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1011–1018. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wheeldon I, Minteer SD, Banta S, Barton SC, Atanassov P, Sigman M. Substrate channelling as an approach to cascade reactions. Nat Chem. 2016;8:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirtz M, Klebensberger J, Otte KB, Richter SM, Hauer B. Production of ω-hydroxy octanoic acid with Escherichia coli . J Biotech. 2016;230:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin VJ, Pitera DJ, Withers ST, Newman JD, Keasling JD. Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:796–802. doi: 10.1038/nbt833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cuellar-Franca RM, Garcia-Gutierrez P, Taylor SF, Hardacre C, Azapagic A. A novel methodology for assessing the environmental sustainability of ionic liquids used for CO2 capture. Faraday Discuss. 2016 doi: 10.1039/c6fd00054a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keller MW, Schut GJ, Lipscomb GL, Menon AL, Iwuchukwu IJ, Leuko TT, Thorgersen MP, Nixon WJ, Hawkins AS, Kelly RM, et al. Exploiting microbial hyperthermophilicity to produce an industrial chemical, using hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5840–5845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222607110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muller JE, Meyer F, Litsanov B, Kiefer P, Potthoff E, Heux S, Quax WJ, Wendisch VF, Brautaset T, Portais JC, et al. Engineering Escherichia coli for methanol conversion. Metab Eng. 2015;28:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ochsner AM, Sonntag F, Buchhaupt M, Schrader J, Vorholt JA. Methylobacterium extorquens: methylotrophy and biotechnological applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:517–534. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Erb TJ, Zarzycki J. Biochemical and synthetic biology approaches to improve photosynthetic CO2-fixation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;34:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hagemann M, Bauwe H. Photorespiration and the potential to improve photosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;35:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Betti M, Bauwe H, Busch FA, Fernie AR, Keech O, Levey M, Ort DR, Parry MA, Sage R, Timm S, et al. Manipulating photorespiration to increase plant productivity: recent advances and perspectives for crop improvement. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:2977–2988. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liang F, Lindblad P. Effects of overexpressing photosynthetic carbon flux control enzymes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Metab Eng. 2016;38:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *62.Antonovsky N, Gleizer S, Noor E, Zohar Y, Herz E, Barenholz U, Zelcbuch L, Amram S, Wides A, Tepper N, et al. Sugar Synthesis from CO2 in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2016;166:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.064. [ Implementation of a functional Calvin cycle in E. coli that is able to generate 35% of the biomass from CO2. The sucesful transplantation and tuning of an Calvin cycle in an alien host represents a level 2 metabolic effort. ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]