Abstract

Humans globally have similar nutritional needs but face large differences in natural resource endowments and local food production. This study quantifies food system inequality across countries based on natural resource inputs, food/nutrient outputs, and nutrition/health outcomes, from 1970 to 2010. Animal source foods and overweight/obesity show rapid convergence while availability of selected micronutrients demonstrate slower convergence. However, all variables are more equally distributed than national income per capita, whose Gini coefficient declined from 0·71 to 0·65. Inequalities in total and animal-source dietary energy declined from 0·16 to 0·10 and 0·55 to 0·36, respectively. There was convergence in overweight/obesity prevalence from 0·39 to 0·27, while undernutrition and stunting became increasingly concentrated in a few high-burden countries. Characterizing cross-country inequalities in agricultural resources, foods, nutrients, and health can help identify critical opportunities for agriculture and food policies, as well as prioritize research objectives and funding allocation for the coming decade.

Motivation

The distribution of agricultural resources and food supplies is a central determinant of human development and health outcomes. Nutritional needs are similar across locations but people live in different environments each with its own limited set of agricultural resources1. Previous research on inequality has found convergence across countries in some aspects of the food system such as dietary patterns2, 3, 4, but inequalities in other aspects of global food systems such as nutrient availability and health outcomes have not yet been quantified and may have worsened or improved as economic, environmental, and population-related conditions have changed5, 6.

This paper quantifies the degree of convergence across countries in food system inputs (agricultural resources), outputs (food and nutrients) and outcomes (nutrition and health), using Lorenz Curves and Gini coefficients to measure inequality in each outcome from 1970 to 2010. These methods were developed to study inequality of income and wealth, and later applied to other aspects of well-being and human capabilities in general7, as well as social epidemiology8, 9, with other applications for example on water use10, 11, industrial goods12, carbon emissions and energy use13, 14 and subjective well-being15. The food system elements that correspond to different inputs, outputs, and outcomes were selected based on data availability.

Previous work on nutrition and health disparities such as Afshin et al. (2019)16 focuses on average levels of each variable. Our focus on inequality is designed to help visualize and quantify the magnitude of relative deprivation and the location of relative scarcity around the world from 1970 to 2010, and thereby reveal the degree to which some countries have caught up while others fall behind changes in other regions. The results indicate whether convergence in the availability of selected dietary components has occurred faster or slower than the convergence of either positive or negative health outcomes, and how inequality in nutritional and health outcomes relate to inequalities in national income and natural resources. These findings can help guide agriculture and food policies, as well as prioritize research objectives and donor funding to help achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other targets linked to global food systems.

Results

Findings for each variable are shown in Lorenz curves and quantile plots to quantify inequality across countries, using a standardized scale for each variable. Each geographic region is color-coded to show how the rank of countries in the global distribution differs across variables and changes over time. Lorenz curves show each country’s share of the cumulative proportion of the population on the horizontal axis and the cumulative proportion of the variable of interest on the vertical axis, plotted generally for 1970 and 2010. A 45-degree line indicates the line of perfect equality against which the Gini coefficient of inequality can be calculated. Each country is a line segment whose horizontal run represents the country’s share of the world population. To complement the Lorenz curves, we use quantile plots, also known as Pen’s parade or ‘parade plots’, showing the absolute level of each variable with a bar width that corresponds to the country’s population size.

Inequality in GDP, land, and livestock

Figures 1 and 2 show how inequality among countries has changed in terms of income and agricultural resources, starting with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita between 1970 and 2010. The between-country equality of GDP distribution has improved in the past 40 years for the bottom 80 percent of the global population (Figure 1, upper panel), reflected by the shift of the Lorenz curve towards equality and the decreasing Gini coefficient (from 0·71 to 0·65). This observation is in line with other empirical work that has found that within-country inequality is more concerning than between-country inequality at this stage17, 18. We further observe an increase in the mean GDP rising by ~16% globally and a clear reordering of countries whereby Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries were in the middle of the distribution in 1970 but by 2010 largely occupy the bottom of the distribution as they have been displaced largely by the rise of China (CH) (Figure 1, lower panel).

Figure 1. Gross domestic product per capita.

Data shown are from the World Bank. Countries are sorted by GDP per capita, and color-coded by region. Lorenz curves (top panels) show cumulative percent of global totals, relative to diagonal line of equality. Parade plots (lower panel) show country averages, relative to the global mean. BR = Brazil, CH = China, ET = Ethiopia, ID = Indonesia, IN = India, MX = Mexico, NG = Nigeria, PK = Pakistan, RU = Russia, US = United States.

Figure 2. Area harvested per rural capita and livestock units per rural capita.

Data shown are from the Food and Agriculture Organization. Countries are sorted by the natural log of the area harvested per rural capita and livestock units per rural capita and color-coded by region. Lorenz curves (top panels) show cumulative percent of global totals, relative to diagonal line of equality. Parade plots (lower panels) show country averages, relative to the global mean. BR = Brazil, CH = China, ET = Ethiopia, ID = Indonesia, IN = India, MX = Mexico, NG = Nigeria, PK = Pakistan, RU = Russia, US = United States.

Figure 2 (top-left panel) reveals that 20% of the world’s rural population in the most land-scarce countries rely on less than 10% of the world’s harvested area with little change between 1970 and 2010. In contrast, the most land-abundant countries – representing 20% of the global rural population – account for almost 60% of the world’s harvested area (upper portion of the curve).

The Gini coefficient rose slightly from 0·42 to 0·43 between 1970 and 2010. In absolute terms, harvested area has remained essentially the same (bottom left panel) between time periods with only a slight decrease in the global mean (6.16 to 5.98 ln ha/rural capita). Specifically, China and India have switched places as the hectares per rural capita has increased in China with increasing urbanization. For other countries such as Pakistan and Ethiopia the average number of hectares per rural capita has reduced as rural populations have continued to expand.

Figure 2 (right panel) also shows the major livestock units (LSU) per rural capita and indicates the stocks of major livestock types. LSU per capita has increased between 1970 and 2010 for the middle portion of the Lorenz curve while the Gini has decreased from 0·53 to 0·48. However, for the lower 20% and upper 10% of the global population, the distribution has remained largely unchanged. About 50% of the LSU are held by the top 15% of the global population. In absolute terms, the global rural per capita LSU has remained essentially the same between time periods increasing slightly from 5.76 to 5.86 LSU/capita.

Inequality in foods and nutrients

Turning to diet quality, Figures 3 and 4 show how inequality among countries has changed in consumption of fruits and vegetables (F&V) as well as animal-source foods (ASF). F&V consumption has consistently been more equal than income or land distribution, but consumption of animal-source foods (ASF) had been very unequal in 1970 and converged to more similar levels by 2010 (Figure 3, left panel). The worldwide Gini coefficient for ASF/capita plummeted from 0·55 to 0·36 as China (CH) and others moved up in the global ranking, leaving roughly a fifth of the world population with ASF consumption below 10% of dietary energy. These trends related to ASF consumption have implications for both the global burden of non-communicable diseases and environmental impacts including biodiversity loss and increased greenhouse gas emissions16, 19.

Figure 3. Energy from animal source foods and from fruits and vegetables.

Data shown are derived from NBS estimates, based on FAO data on food use by country and USDA data on nutrient composition of each food. Countries are sorted by nutrient availability per capita and color-coded by region. Lorenz curves (top panels) show cumulative percent of global totals, relative to diagonal line of equality. Parade plots (lower panel) show country averages, relative to the global mean. BR = Brazil, CH = China, ET = Ethiopia, ID = Indonesia, IN = India, MS = Mexico, NG = Nigeria, PK = Pakistan, RU = Russia, US = United States, RW = Rwanda.

Figure 4. Micronutrient availability per capita.

Data shown are derived from NBS estimates, based on FAO data on food use by country and USDA data on nutrient composition of each food. Countries are sorted by nutrient availability per capita and color-coded by region. Lorenz curves (top panels) show cumulative percent of global totals, relative to diagonal line of equality. Parade plots (lower panel) show country averages, relative to the global mean. BR = Brazil, CH = China, ET = Ethiopia, ID = Indonesia, IN = India, MS = Mexico, NG = Nigeria, PK = Pakistan, RU = Russia, US = United States, SL = Sierra Leone.

Dietary energy from fruits and vegetables (F&V) has increased in the past 40 years from 108 to 205 kcal/capita, again with significant increases in China. However other countries, particularly in SSA, remain below the mean and for some the amount of energy from F&V has stayed the same or decreased (e.g., Nigeria) (Figure 3, right panel). The Lorenz curve shows that the roughly doubling in available energy from F&V has been generally evenly distributed, reflected in the Gini shifting from 0·35 to 0·27 and the lowest 15% of the global population not moving towards the line of equality.

Turning to nutrients, available vitamin A per capita increased from an average of 439 mcg/capita to 637 mcg/capita from 1970 to 2010 (Figure 4, panel 1). Equality in vitamin A availability also increased indicated by the reduction in Gini from 0·40 to 0·25. However, while the gap between average vitamin A requirements and availability has narrowed for some countries, for many others - particularly from SSA and South Asia - per capita availability is still significantly less than the average daily requirement (AR) for adult men (570 mcg) and women (490 mcg)20.

Zinc availability has increased over the past 40 years with the global mean rising from 13·9 mg/capita to 16·2 mg/capita (Figure 4, panel 2). While these levels exceed the AR for zinc for both men (10.67 mg) and women (9.67 mg), as with vitamin A, a number of countries in SSA and South Asia are still below or just near the requirements. Equality of zinc availability across countries has also increased, evidenced by the change in Gini coefficient from 0·20 in 1970 to 0· 13 in 2010. The increase in equality has again resulted in redistribution of the global rankings as China has displaced countries such as India, Mexico, Ethiopia and Pakistan backward in the global ranking.

For dietary iron, mean availability per capita has increased from 17·6 mg/capita to 21·2 mg/capita between 1970 and 2010, approximately three times the daily average requirement of 6.0mg for men and 7.0mg for women (Figure 4, panel 3). As with vitamin A and zinc, countries in SSA and South Asia have available iron much closer to daily requirements. Distributions around these means likely reflect inadequate intake among populations in these countries, particularly if there are significant additional nutrient losses due to food loss and waste21. Equality has increased but only in the upper 50% of the distribution. Of note is that iron availability in China increased significantly, thrusting China from within the lower 35% to the upper 30% of the distribution. The Gini has decreased slightly from 0· 17 to 0· 13.

Results shown here for dietary iron and zinc may mask inequality in diet quality and nutritionally available minerals, because diets dominated by vegetal foods may be high in compounds such as phytates and oxalates that bind these elements, and further reduce absorption. To the extent that bioavailability varies across the distribution based on availability of ASF and other factors, the inequality profiles of bioavailable iron and zinc are likely to look different. For example, when considering iron, the Gini coefficient for heme iron is 0.50 in 1970 and 0.36 in 2010, while for non-heme iron it is 0.16 in 1970 and 0.12 in 2010 (not shown). Likewise, the Gini for animal-sourced zinc (which is not accompanied by phytates) changed from 0.54 (1970) to 0.37 (2010) while the Gini for plant-sourced zinc changed more modestly from 0.15 in 1970 to 0.10 in 2010 (not shown).

Among other nutrients, availability of protein (g/capita) also increased and became more equal (Supplementary Figure 2, left panel), evidenced by the Lorenz curve shift toward equality and the lower slope on the Parade graph for 2010. Mean availability increased from 76·4 g/capita in 1970 to 92·4 g/capita in 2010; however, countries in SSA have increasingly fallen below the mean as large countries such as China, Brazil and Mexico have increased their protein availability at faster rates. Overall, the Gini coefficient for protein availability decreased from 0·20 in 1970 to 0·14 in 2010, with a greater reduction coming from animal-sourced protein (0.52 to 0.34) than for plant-based protein (0.13 to 0.09) between 1970 and 2010 (not shown). Availability of fat in the food supply has also increased (Supplementary Figure 2, right panel), from 61·1 g/capita in 1970 to 88·0 g/capita in 2010, a 44% increase in per capita fat availability. This change has largely been attributed to increased availability of plant oils (e.g., soybean and palm oil) and ASF (e.g., milk, bovine meat and poultry). Availability has also equalized significantly, as the global Gini fell from 0·38 to 0·24 between 1970 and 2010 and affects all but those countries that comprise the lowest 10% of the global population.

Inequality in anthropometric outcomes

Next, we examine health and diet-related nutrition outcomes. Stunting prevalence – an indicator of child development – is measured as the percentage of children under five years of age that are at least two standard deviations below the median height for age. The Parade plot shows a large decrease in the global mean from 35·0% to 22·0%, as stunting is increasingly geographically concentrated in a few countries shown by the lower portion of the Lorenz curve. Other countries continue to have very low stunting rates so its Gini coefficient has risen over this period, from 0·23 to 0·29 (Figure 5, panel 1).

Figure 5. Stunting per children <5, underweight, and overweight per adult population.

Data shown are from the UNICEF/World Bank/WHO Joint Monitoring Program for stunting and NCD RisC Group for underweight and overweight/obesity. Stunting data come from a range of years and were grouped based on earliest data point and most recent data point. Countries are sorted by prevalence of stunting, underweight, or overweight and obesity, and color-coded by region. Lorenz curves (top panels) show cumulative percent of global totals, relative to diagonal line of equality. Parade plots (lower panels) show country averages, relative to the global mean. BR = Brazil, CH = China, ET = Ethiopia, ID = Indonesia, IN = India, MX = Mexico, NG = Nigeria, PK = Pakistan, RU = Russia, US = United States.

Prevalence of underweight is defined as body mass index (BMI) <18·5 for men and women over 18 years of age. Globally, underweight has decreased 33% from a mean prevalence of 14·5% to 9·7% between 1975 and 2010. Like stunting, underweight has become more geographically concentrated as reflected in the Lorenz curve shifting to the right (Figure 5, panel 2).

While undernutrition has declined and become more concentrated in a few countries, rates of overweight or obesity have risen and are converging to more similar levels among countries. Overweight/obesity prevalence, defined as a BMI >25 for men and women over 18 years of age, has increased 15 percentage points (from a mean prevalence of 21 ·4% in 1975 to nearly 36·3% in 2010) (Figure 5, panel 3) and is becoming more similar across countries with a decrease in the global Gini from 0·39 to 0·27.

Inequality in diet-related diseases

Hypertension is a diet-related disease whose risk factors include high sodium and/or low potassium intake, low physical activity, stress, etc., and is defined as having blood pressure above 140+ mm Hg (systolic bp) or 90+ mm Hg (diastolic bp). The Lorenz curves for women and men show increasing inequality in the global distribution of hypertension with smaller changes for women (0·16 in 1975 and 0·13 in 2010) compared to men (0·17 in 1975 to 0·09 in 2010). Over this period, mean prevalence of hypertension decreased from 25.7% to 21.3% for women and 29.0% to 25.0% for men; however, countries have reordered. Figure 6 shows that women and men in higher income regions have shifted from the right to the left side of the distribution between 1975 and 2010. This is particularly striking in the case of women (Figure 6, panel 1), where in 2010, SSA and South Asian countries appeared clustered on the right side of the distribution as a result. The lower prevalence in high-incomes countries is likely due to improvements in detection and treatment, in addition to changes in risk factors22. Other reasons for the decreased prevalence of hypertension, particularly in middle-income countries, might include unmeasured improvements in childhood nutrition and year-round availability of fruits and vegetables22.

Figure 6. Hypertension, female and male.

Data shown are from the NCD RisC Group. Countries are sorted by the prevalence of hypertension and color-coded by region. Lorenz curves (top panels) show cumulative percent of global totals, relative to diagonal line of equality. Parade plots (lower panels) show country averages, relative to the global mean. BR = Brazil, CH = China, ET = Ethiopia, ID = Indonesia, IN = India, MX = Mexico, NG = Nigeria, PK = Pakistan, RU = Russia, US = United States.

The prevalence of diabetes – characterized by a fasting plasma glucose of 7·0+ mmol/L, a diabetes diagnosis, or the need for insulin or oral hypoglycemic drugs – is a rising concern worldwide. The Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient show greater divergence for women (Gini: 0·12 to 0·15) but greater convergence for men (Gini: 0·14 to 0·11) between 1980 and 2010 (Supplementary information). In contrast to hypertension, the mean prevalence of diabetes has increased from 5·0% to 7·7% (a 53·9% increase) for women and from 4·2% to 8·4% for men (a 98·6% increase) between 1980 and 2010, with countries in South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean carrying most of the increase. In addition, the number of adults affected has also increased, with a higher burden in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) than in high-income countries23.

Comparing inequality across domains

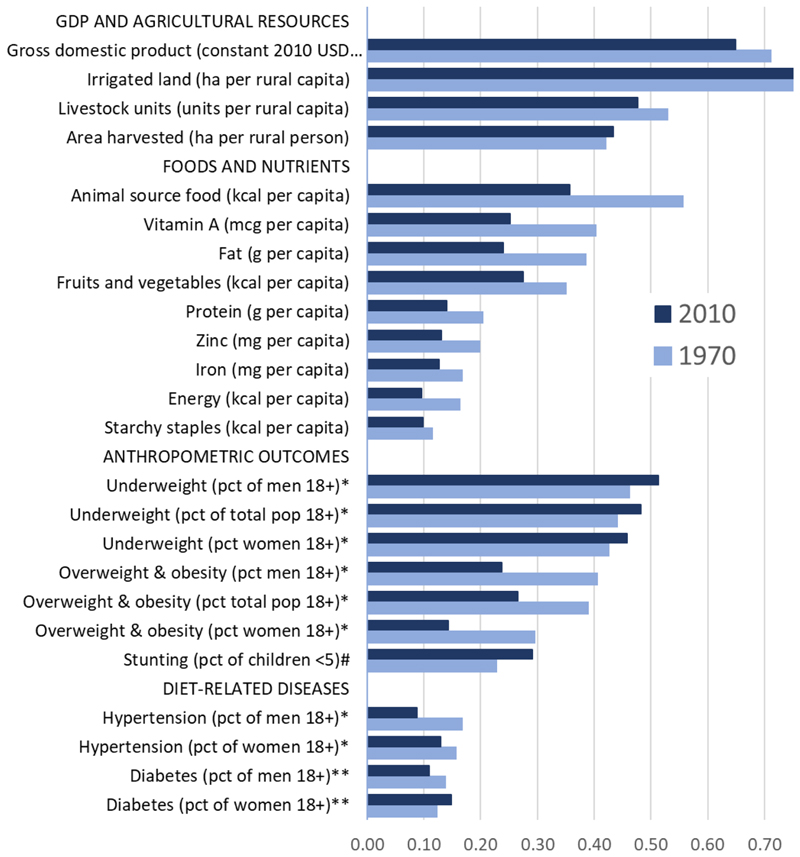

Figure 7 provides Gini coefficients ordered from the largest to smallest value in 1970. The most uniform distributions around the world are for select foods and nutrients and non-communicable diseases, whereas the most unequal distributions are generally for GDP, agricultural resources, and anthropometric outcomes.

Figure 7. Levels and changes in Gini coefficients (1970 and 2010).

Data shown are Gini coefficients, ranging from unity (complete inequality) to zero (perfect equality), constructed as detailed in the text from national totals in 2010 compared to 1970 or the earliest available year, denoted *= 1975, ** =1980, #Years for stunting data vary by country.

GDP is the most unequal of the variables shown. Irrigated land, LSU, and area harvested have relatively high and sustained Gini coefficients as well. Despite this observation, equality increased substantially for energy from ASF and to a lesser extent energy from F&V. Correspondingly, inequality in the availability of nutrients has greatly reduced, most significantly for dietary fat and vitamin A. With respect to outcomes, we observe increased convergence in overweight/obesity. On the other end of the spectrum, child stunting and total underweight have become more highly concentrated in a few high-burden countries.

Strengths and limitations

This research quantifies the level of inequality across countries in agriculture, food, nutrition, and health, providing a unified view of whether and how the world food system has converged from 1970 to 2010. The work aims to identify patterns whose causes could be investigated in future research. A strength of this approach is that it enables summarizing a large amount of information both succinctly (using the Gini coefficient) and intuitively (though visualizations that show relative changes between countries). This research focuses on food system inequalities (i.e., the uneven distribution of key inputs, outcomes, and impacts), future work could explore similar themes with individual level data, as well as structural and underlying inequities in the food system both within and between countries such as differences in affordability of nutrient-rich foods over space and time24, 25.

A principal limitation is that we measure inequality between countries only, while many observers are additionally interested in inequality within countries and for which different kinds of data would be needed. For national totals, the available data vary, for example, with regard to the quality and completeness of the underlying Food Balance Sheets (FBS). These data are sourced from estimated production and non-food uses, as well as international trade records for major crops and livestock products with limited information on the diverse items that do not enter commodity markets such as garden produce and wild foods. In addition, data that are included vary in quality as only some estimates come from official national accounts (38% in 2005 and 61% in 2010) while the rest are filled in through additional triangulation methods26. Another limitation of using FBS data is that the food and nutrient data reflects availability rather than individual level consumption (dietary) data. Finally, given that the most recent observation in our data is from ten years ago, trends may have shifted since the data were compiled.

Discussion

The second Universal Value of the SDGs states “leave no one behind” which is repeated multiple times in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, along with the phrase that “we will endeavour to reach the furthest behind first” 27, 28. Our findings highlight changes in key food system inputs, outputs, and outcomes across countries, showing global improvement in some areas, and persistent inequality in others.

The largest and most enduring inequalities relate to the agricultural resources used by each country’s rural population. Across Asia and other regions where population growth has slowed rapidly, continued out-migration from rural areas put an end to decades of shrinking farm sizes, allowing the remaining farmers to cultivate increasing land area from year to year. This ‘structural transformation turning point’, when average farm sizes stop shrinking and start expanding, happened around 1914 in the United States, and eventually spread from East Asia in the 1970s across Southeast and South Asia in the 2000s29. For SSA as a whole, that turning point will not occur until after 2050, despite rapid growth of cities, due to the continent’s very young population and the large fraction of its population whose livelihoods depend on agriculture30. In parallel, many countries - especially in Asia - have experienced increasing productivity due to agricultural intensification as use of high-yielding seeds, fertilizer, pesticides, irrigation and other technologies have expanded31, 32.

Poor diets are one of the leading risk factors for death and disease globally16, 33. Our results show that all foods and nutrients are more equally distributed in 2010 compared to 1970. The greatest absolute changes in the Gini were observed for energy from ASF (20 percentage points) followed by total dietary fat (14 percentage points). Increased equality of the global distribution of additional foods and nutrients are observed in the data to a lesser extent in absolute terms (ranging from 2-7 percentage points), though reductions ranged from 13% in the case of starchy staples to 41% for overall dietary energy. Despite the shift towards greater equality, the absolute level of consumption of most healthy foods remains sub-optimal. For example, findings from the 2002-2003 World Health Survey found that 77 ·6% of men and 78 ·4% of women in 52 (mostly) LMICs consumed less than the five servings (or 400 g) of F&V per day recommended by the World Health Organization. This is particularly concerning as low intake of fruit is one of the top three contributors -- along with high intake of sodium and low intake of whole grains -- accounting for half of all diet-related deaths and two-thirds of diet related DALYs16. This underscores the fact that while in general, availability of fruits and vegetables has generally increased among LMICs, this analysis does not account fully for other barriers to sufficient consumption such as important sources of food loss and waste that further limit eventual intake34 and within-country inequalities in access to fruits and vegetables specifically among the poorest35.

We find that convergence of several potentially harmful outcomes has occurred faster than convergence of several beneficial outcomes. Trade and markets have been critical in increasing a more equitable global distribution of food and nutrients, and ultimately health outcomes, given the inherent inequality of agricultural resources and food production across countries36. Yet, trade and well-functioning markets have not benefitted the equitable distribution of all foods and nutrients, and the impact on nutrition and health outcomes is mixed. Overall, the convergence of some foods and nutrients (e.g., ASF, fat) has increased more rapidly, compared to the distribution of other foods and nutrients such as F&V, zinc, iron, and Vitamin A. In addition to trade and functioning markets allowing for increased availability of diverse foods and nutrients, other factors such as consumer preferences, relative prices, food processing, and marketing of specific foods and products have further contributed to the observed patterns of convergence. The nutrition and health implications related to these dietary changes have contributed to concomitant decreases in stunting and underweight37 and increases in overweight and obesity, and non-communicable diseases like diabetes23, 38, 39.

In sum, our results show that inequality between countries generally declined from 1970 to 2010 but did so very differently across the outcomes of interest. We find that despite high and sustained levels of between-country inequality in per capita income and food system resources, food and nutrient availability and health outcomes have converged around the world. However, whether this convergence is considered positive or negative depends on the outcome in question. In the case of many – but not all -- foods and nutrients this is a positive trend, while for other variables such as overweight and obesity and hypertension this convergence has negative implications. In particular, there have been significant changes in some countries in the 40-year period, particularly regarding food and nutrient availability in large economies such as China, India, and Brazil, and yet availability of food and nutrients have also improved for countries at the lowest end of the distribution. Given the negative health trends such as increasing overweight and obesity and non-communicable diseases around the world, policies are necessary to ensure that not only dietary quantity increases but also dietary quality across all countries with not one left behind. These results provide insight for prioritizing research objectives and donor funding to achieve the UN SDGs and other targets linked to global food systems and population health.

Methods

Data

Data for this paper were drawn from a variety of publicly available sources (Supplementary Table 1). The variable for Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is reported in 2010 dollars and comes from the World Bank World Development Indicators40. This variable shows each country’s total production. Variables for area harvested, livestock units, and inputs (irrigated land and fertilizer use) come from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) FAOSTAT with most data available41. Livestock units (LSU) are a reference unit that allows for the aggregation of different types and sizes of livestock based on the feed requirements of each species and category. The LSU reference unit is equivalent to the amount grazed by one adult dairy cow producing 3000 kg of milk annually that is not fed any additional foods.

The food and nutrient supply variables, including overall dietary energy, other macronutrients and micronutrients come from the Nutrient Balance Sheet (NBS) database (publication forthcoming). The NBS parallels the FAO’s food balance sheets (FBS), matching the 97 food categories in the FBS with the nutritional composition of roughly 1000 foods to track the global flow of 33 nutrients through production, international trade, animal feed, seed, manufacturing, waste, and human consumption in terms of the originating primary commodity equivalents. The NBS is developed specifically to examine changes in production, international trade, food system transformations and availability of nutrients over time. While other databases have been developed that provide estimates of nutrient availability based on FBS data42, 43, these databases do not include additional FBS-related variables. Data are currently available for 1961-2013. From this dataset dietary energy was further disaggregated into variables for energy from animal source foods, energy from fruits and vegetables, and energy from starchy staples.

FBS show supply-side variables on the left-hand side of the balance equation (production, imports and exports) and demand-side variables on the right (supply used as seed, feed, food manufacturing, other use, waste, and food) for 97 food categories. In the NBS, FBS food category definitions of primary originating food forms were used to match the FBS categories (which may each include many individual food commodities) to food items in the USDA SR legacy database available at Food Data Central44. The food composition table (FCT) information for each nutrient including the edible portion of each food item, was then collapsed as an average of the food items corresponding to each FBS food category and multiplied by the FBS food category quantity to standardize the FBS for each macro- and micronutrient. The data were then converted into per capita values using country-specific annual population totals (see below) for 173 countries.

Data for adult nutrition outcomes and health variables come from the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) comprised of a network of health scientists around the world who work in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO). Three different sources of data from the NCD-RisC were used for measuring body mass index (BMI), blood pressure and diabetes. The data on adult underweight and overweight were taken from a pooled analysis of 1·698 population-based adult BMI studies with over 19·2 million participants from 189 countries. Both the mean BMI and the prevalence were used with standard cut-offs for BMI categories applied in the original analysis (<18·5 kg/m2 [underweight] and >25 ·0 kg/m2 [overweight and obesity]38. Stunting data come from the Joint Monitoring Programming, a collaboration between the World Bank, the World Health Organization, and UNICEF. The number of data observations varies by country and the years of data collection are staggered.

The variable for blood pressure – defined as systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher -- is based on 1·479 population-based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants22. Trends in diabetes prevalence, measured as the fasting plasma glucose of 7·0 mmol/L or higher, or history of diagnosis with diabetes, or use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic drugs, were drawn from a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants from 146 countries23. NCD-RisC uses Bayesian hierarchical models to estimate trends over time in 200 countries and all data are age-standardized to the WHO standard population by taking weighted means of age–sex-specific estimates, with use of age weights from the standard population.

Demographic information including rural population, total population, women over 18 years of age, men over 18 years of age, and children under five are drawn from the United Nations Population Division (UN DESA), who produce country-level estimates of urban and rural populations by age and sex from 1950 through 201545. For all variables, estimates for rural and urban populations come from the World Urbanization Prospects, 2018 Revision46.

Data cleaning and variable transformation

All analyses compare data between 1970 and 2010 or use the closest available years; this time period was selected as it spans considerable changes in terms of agriculture, food, and health outcomes. There was also a practical element that inhibited the ability to start at an earlier time point, which was that some data were reported every five years (e.g., UNDESA sex disaggregated population data) and other data are only available beginning in 1961 (e.g., FAOSTAT) thus eliminating the option to start in 1960 (or earlier). The cut-off of 2010 was used because it was a year in which all data were available. To provide comparability across years, data are presented for both timepoints based on currently existing territories (e.g., Ethiopia and Eritrea are presented individually for 1970 rather than the combined Ethiopia PDR for 1970). To do so, the per capita value of the “parent” country for the earlier timepoint (e.g., Ethiopia PDR) was applied to each constituent (i.e., Ethiopia and Eritrea) for that year, and the estimated population of each constituent territory was applied using information from UNDESA to avoid under- or double-counting of the applicable population. The UN DESA population estimates use contemporary country borders for past, present, and future estimates.

Several variables required additional cleaning and transformation. Area harvested sums hectares of all crops produced by country and year. Energy from fruits and vegetables and energy from animal source foods sum the energy from fruit and vegetables or animal source foods available by each country and year. Total overweight and obesity and total underweight combine the original NCD RisC data which are presented separately for men and women into a single value. For stunting, given the varied observations per country and the different years available, we selected the earliest data point and the most recent data point for each country. For the earlier time period, most fall between 1983 and 2005. However, there are several countries that collected stunting prevalence for the first time in 2006 (Belize, South Sudan, Sudan). For the most recent time point, most countries have an observation that falls between 2005 and 2018 but for a few countries the most recent measure comes before 2005 (Bahrain (1995), Mauritius (1995), Czech Republic (2001), Romania (2002), Fiji (2004), Lebanon (2004)).

All available countries, regardless of population size, were retained in the sample. When considering absolute levels, outliers were included but truncated so as not to affect the optics of the distribution. For several highly skewed variables (e.g., area harvested, livestock units) the natural log was taken. The regional groupings used are based on the World Bank region classification and were separated into seven distinct regions: East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, North America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa47. All countries were matched across datasets using the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 3166-1 alpha-3 codes (ISO 3) and ISO numeric country codes.

Data analysis

Global inequality can be measured at three different levels, each with varying degrees of nuance. The most basic approach measures unweighted international inequality, where each country counts the same. With this approach, the country is the unit of observation and uses a per capita measure but does not take account of the population. A second approach is population-weighted international inequality in which the mean value of each country is weighted by the population. This approach says nothing about within-country distribution of resources and assumes equal distribution of resources within the country. The third option is to use actual individual level data and calculate inequality across all individuals in the world from poorest to richest48.

For our analyses, we use the population-weighted measure of inequality, where the country is the unit of observation, but accounting for population size. Using this method, we are able to draw conclusions about the overall levels of inequality (land, food, nutrients etc.) but cannot draw any conclusions about the within-country distribution of resources. This is an oversimplification of reality in which within-country nutrition and health inequality is a critical concern, and often associated with income, education, and other socio-economic factors, but the objective of this analysis is to show global trends across countries.

We use techniques borrowed from the field of economics and applied in an innovative way to provide a stylized picture of the distribution of resources. We use Lorenz curves to show how inequality has changed over time. The Lorenz curve is a graphical representation with each country’s share of the cumulative proportion of the population on the horizontal axis and the cumulative proportion of the variable of interest on the vertical axis. The Lorenz curves are plotted for two time points (generally 1970 and 2010, depending on data availability) with a 45-degree line indicating the line of perfect equality and the Lorenz curve appearing below it. If the variable on the vertical axis were distributed equally among all countries, then the Lorenz curve would be a diagonal line. The greater the amount of bowing of the Lorenz curve from the line, the greater the inequality across countries. Another feature of the Lorenz curves shown here is that countries are distinguished as segments on the curves (with the horizontal run of the segments based on countries’ relative population sizes), enabling the viewer to see how countries have shifted along the inequality spectrum over time. The Gini coefficient can be derived from the Lorenz curve by taking the ratio of the area between the line of equality and the Lorenz curve as the numerator and the area of the triangle (everything under the line of equality) as the denominator. The Gini coefficient can range from 0-1 with higher numbers indicating greater inequality. In this case we used the Gini index generated by using the fastgini Stata command and applying pweights to account for country population size.

To complement the Lorenz curves, we present figures of Pen’s parade or parade plots for each variable to provide a more nuanced perspective of the changes over time (1970 and 2010), particularly highlighting the population of the country. This type of data visualization - also known as a quantile plot - was first developed for use in income inequality analysis, where typically the height is proportional to the income and observations are ordered from lowest to greatest49. The data are arrayed from the lowest per capita value to the highest per capita value with the width of each bar corresponding to the country’s population size50. This set of figures provides information on the absolute, per capita values and includes a line for the mean value of each variable in 1970 and 2010. The mean line is shown in order to indicate whether the global level of each outcome is increasing or decreasing and to maintain a link with the Lorenz curve; the ratio of each country mean to the global mean is equal to the slope of the country’s line segment on the Lorenz curve.

For both the Lorenz curves and parade plots, national level data were used, and per capita values calculated with Stata 15 statistical software. Graphics were designed using the color palette from Color Brewer 2·0 from Pennsylvania State University51. Additional results for an expanded set of variables can be found in the Supplementary information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Alan Dangour and Bhavani Shankar for initiating this project with funding for WB and KL from the Wellcome Trust (grant number 210794/Z/18/Z). WM was supported by the United States Agency for International Development (cooperative agreement 720-OAA-18-LA-00003). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed here are those of the authors alone.

Footnotes

Ethics declaration: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and code

All data used in this study are publicly available from open sources as indicated in the references in the Methods section. All figures were produced in Stata with the exception of Figure 7 which was produced using Excel. Inquiries related to the NBS should be made to Keith Lividini, keith.lividini@tufts.edu or k.lividini@cgiar.org.

References cited

- 1.Rockström J, Stordalen GA, Horton R. Acting in the anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet commission. The Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2364–2365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30681-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentham J, Singh GM, Danaei G, et al. Multidimensional characterization of global food supply from 1961 to 2013. Nature Food. 2020;1:70–75. doi: 10.1038/s43016-019-0012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popkin BM. Relationship between shifts in food system dynamics and acceleration of the global nutrition transition. Nutrition Reviews. 2017;75(2):73–82. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuw064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khoury CK, Bjorkman AD, Dempewolf H, Ramirez-Villegas J, Guarino L, Jarvis A, Rieseberg LH, Struik PC. Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2014. pp. 4001–4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkes C, Chopra M, Friel S. Globalization, Trade, and the Nutrition Transition. Ch. 10. In: Labonté R, Schrecker T, Packer C, Runnel V, editors. Globalization and Health: Pathways, evidence and policy. 1st. Routledge; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker P, Friel S. Food systems transformations, ultra-processed food markets and the nutrition transition in Asia. Globalization and Health. 2016;12(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0223-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sen Amartya. The Tanner Lecture on Human Values. Stanford University; 1979. Equality of What? [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagstaff A, Paci P, Van Doorslaer E. On the measurement of inequalities in health. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;33(5):545–557. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90212-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper S, Lynch J. Health inequalities: Measurement and Decomposition. Ch. 5. In: Oakes JM, Kaufman J, editors. Methods in Social Epidemiology. 2nd. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seekell DA, D’Odorico P, Pace ML. Virtual water transfers unlikely to redress inequality in global water use. Environmental Research Letters. 2011;6(2) doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/6/2/024017. 024017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guragai B, Takizawa S, Hashimoto T, Oguma K. Science of the Total Environment Effects of inequality of supply hours on consumers’ coping strategies and perceptions of intermittent water supply in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Science of the Total Environment. 2017;599-600:431–441. doi: 10.1016/?.scitotenv.2017.04.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinberger JK, Krausmann F, Eisenmenger N. Global patterns of materials use: A socioeconomic and geophysical analysis. Ecological Economics. 2010;69(5):1148–1158. doi: 10.1016/?.ecolecon.2009.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groot L. Carbon Lorenz curves. Resource and Energy Economics. 2010;32(1):45–64. doi: 10.1016/?.reseneeco.2009.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence S, Liu Q, Yakovenko VM. Global inequality in energy consumption from 1980 to 2010. Entropy. 2013;15(12):5565–5579. doi: 10.3390/e15125565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gluzmann P, Gasparini L. International Inequality in Subjective Welfare: An exploration with the Gallup World Poll. 2014:1–22. doi: 10.1111/rode.12356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afshin A, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990--2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milanovic B. Worlds apart: Measuring international and global inequality. University Press; Princeton NJ: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milanovic B. Global Inequality. The Belknap Press; Cambridge MA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willett WC, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2020;393(10170):447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition & Allergies. Dietary reference values for nutrients. Summary Report EFSA Supporting publication. 2017;2017 e15121. Update: 4 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food and Agriculture Organization. Global food losses and food waste – Extent, causes and prevention. Rome: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.NCD RisC. Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19 · 1 million participants. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31919-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NCD RisC. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants. The Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1513–1530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herforth A, Bai Y, Venkat A, Mahrt K, Ebel A, Masters WA. FAO Agricultural Development Economics Technical Study No. 9. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Rome: 2020. Cost and affordability of healthy diets across and within countries. Background paper for The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bai Y, Naumova EN, Masters WA. Seasonality of diet costs reveals food system performance in East Africa. Science Advances. 2020;6(49) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc2162. eabc2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Food and Agriculture Organization. African Commission on Agricultural Statistics: Issues in the collection of FAO data. 2013 http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/documents/afcas23/DOC_-_3f_Eng_.pdf.

- 27.UN Sustainable Development Goals. Universal Values: Leave No One Behind. [Accessed 4 December 2020]; https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/universal-values/leave-no-one-behind.

- 28.UN Sustainable Development Goals. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [Accessed 4 December 2020]; https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld.

- 29.Tomich TP, Kilby P, Johnston B. Transforming Agrarian Economies: Opportunities Seized, Opportunities Missed. Cornell University Press; Ithaca: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masters WA, Rosenblum NZ, Alemu RG. Agricultural Transformation, Nutrition Transition and Food Policy in Africa: Preston Curves Reveal New Stylised Facts. The Journal of Development Studies. 2018;54(5):788–802. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2018.1430768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matson PA, Parton WJ, Power AG, Swift MJ. Agricultural Intensification and Ecosystem Properties. Science. 1997;227(5325):504–509. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudel TK, Schneider S, Uriarte M, Turner BL, DeFries R, Lawrence D, Geoghegan J, Hecht S, Ickowitz A, Lambin EF, Birkenholtz T, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2009. pp. 20675–20680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forouzanfar MH, et al. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Global, regional and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2015;386:2287–323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.FAO. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. Rome: 2019. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 35.FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. FAO; Rome: 2020. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood SA, Smith MR, Fanzo J, et al. Trade and the equitability of global food nutrient distribution. Nat Sustain. 2018;1:34–37. doi: 10.1038/s41893-017-0008-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Black RE, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middleincome countries. The Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NCD RisC. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19 · 2 million participants. The Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1377–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NCD RisC. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128 · 9 million children, adolescents, and adults. 2017:2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Bank. World Development Indicators. [Accessed November 2019]; http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.

- 41.Food and Agriculture Organization. FAOSTAT. [Accessed November 2019]; http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/

- 42.Smith Matthew R, Micha Renata, Golden Christopher D, Mozaffarian Dariush, Myers Samuel S. Global Expanded Nutrient Supply (GENuS) model: a new method for estimating the global dietary supply of nutrients. PLoS One. 2016;11(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146976. e0146976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidhuber J, Sur P, Fay K, Huntley B, Salama J, Lee A, Cornaby L, Horino M, Murray C, Afshin A. The Global Nutrient Database: availability of macronutrients and micronutrients in 195 countries from 1980 to 2013. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2018;2(8):e353–e368. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30170-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Legacy. 2018 Apr; Internet: http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata Version Current.

- 45.Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. World Population Prospects 2018. [Accessed November 2019]; https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/

- 46.Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects 2018. [Accessed November 2019]; https://population.un.org/wup/

- 47.World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. [Accessed January 2018]; https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

- 48.Milanovic B. The Three Concepts of Inequality Defined, from Worlds Apart: Measuring International and Global Inequality. University Press; Princeton NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pen J. Income Distribution. Allen Lane; London: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jann B. Variable bar widths in two-way graphs. The Stata Journal. 2015;15(1):316–318. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brewer, et al. Color Brewer 2.0: Color advice for cartography. 2013 http://colorbrewer2.org/#.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are publicly available from open sources as indicated in the references in the Methods section. All figures were produced in Stata with the exception of Figure 7 which was produced using Excel. Inquiries related to the NBS should be made to Keith Lividini, keith.lividini@tufts.edu or k.lividini@cgiar.org.