Summary

A relatively small number of proteins have been suggested to act as morphogens, signalling molecules that spread within tissues to organize cell fate specification during development and tissue repair. Among them are Wnt proteins, which carry a palmitoleate moiety that is essential for signalling activity1–3. How can a hydrophobic lipoprotein spread in the aqueous extracellular space? A variety of mechanisms, some invoking lipoprotein particles, exosomes or a specific chaperone, have been proposed to overcome this so-called Wnt solubility problem4–6. Here we provide evidence against these models and show that the Wnt lipid is shielded by the core domain of a subclass of glypicans defined by the Dally-like protein (Dlp). Structural analysis shows that, in the presence of palmitoleated peptides, these glypicans change conformation to create a hydrophobic space. Thus, glypicans of the Dlp family protect the lipid of Wnts from the aqueous environment and serve as a reservoir from where Wnts can be handed over to signalling receptors.

Keywords: Wnt, palmitoleate, glypicans, crystal structure, morphogens

Wnt proteins are lipidated1, with a palmitoleate2 appended to a conserved serine (Ser 209 in WNT3A). Crystal structures have shown how the Wnt palmitoleate contributes directly to engagement with the Frizzled receptor and hence signalling activity3. Despite being lipidated, and therefore hydrophobic, Wnts can act over several cell diameters, although the range may vary depending on the tissue. Long range action has been suggested to organize the anterior-posterior axis of Xenopus embryos7 while juxtacrine action could suffice in the mouse intestinal crypt8. Flies relying solely on membrane-tethered Wingless (the main Wnt in Drosophila) are morphologically normal, but suffer from a number of phenotypes including delayed development, sterility, and reduced food intake9(see also reference10). Even in wing precursors, where long range action is not essential for patterning, Wingless spreads over more than 10 cell diameters11 and contributes to timely growth and full target gene activation9. Because extracellular Wingless is readily detectable in wing imaginal discs, they constitute a good tissue in which to study its spread in a physiological setting.

Models of Wnt transport

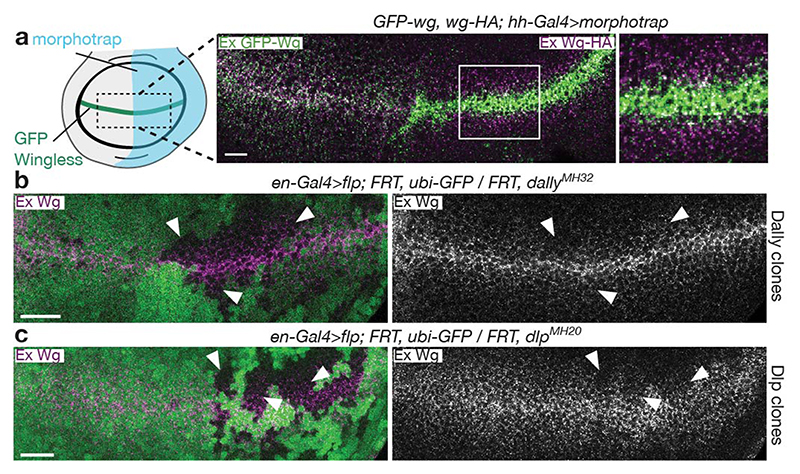

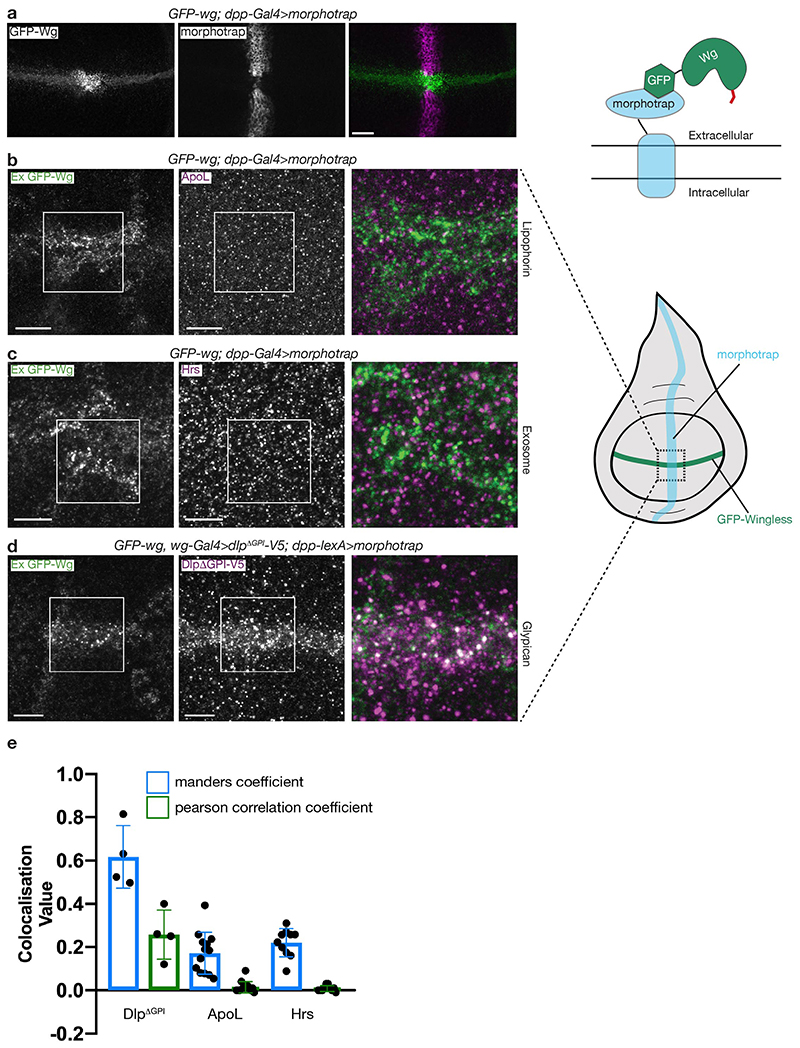

Earlier work has suggested that lipoprotein particles (LPPs) or exosomes could transport Wnt in the extracellular space4,5. To test whether endogenously expressed Wingless interacts with these structures, we devised a trapping assay inspired by the morphotrap approach12. A membrane-tethered anti-GFP nanobody (Vhh4-CD8) was used to capture GFP-Wingless expressed from a knock-in allele. This led to enrichment of GFP-Wingless at the surface of expressing cells (Extended Data Fig. 1a), but not of Lipophorin, a component of LPPs, or the ESCRT protein Hrs, a marker of exosomes (Extended Data Fig. 1b, c). A secreted form of Dlp (DlpΔGPI), which is known to bind Wingless13,14, served as a positive control (Extended Data Fig. 1d). Moreover, we found that GFP-Wingless trapped by Neurotactin-LaG16 (another morphotrap) had no effect on the distribution of HA-Wingless expressed from the other endogenous allele (Fig 1a). This result argues against transport mechanisms involving multiple Wingless molecules such as exosomes, LPPs, or micelles.

Figure 1. Spread of Wingless does not involve multimeric assemblies but requires Dlp.

a) Morphotrap (NRT-MYC-LaG16) driven in the posterior compartment by hh-Gal4 captures GFP-Wingless, but not Wingless-HA (both expressed from knock-in alleles). In the control anterior compartment, both forms of Wingless show a graded distribution. The experiment was repeated independently three times with similar results. b, c) Extracellular Wingless is reduced to a greater extent in clones lacking Dlp than clones lacking Dally (clones marked by the absence of GFP (white arrowheads). Scale bars represent 10μm in a and 25μm in b and c. The experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results.

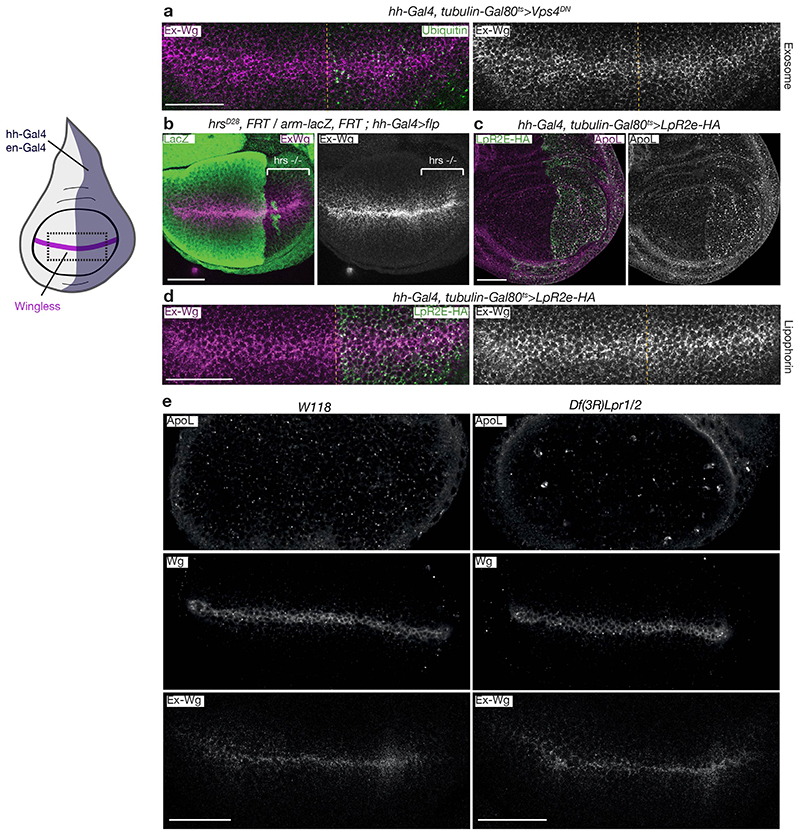

We next designed genetic tests to further assess the possible roles of exosomes and LPPs. As there is no specific way to prevent exosome formation, we inhibited the biogenesis of multivesicular bodies from where exosomes originate. This was achieved by expressing VPS4DN, a dominant negative form of VPS4, which is required for the final step in the invagination of luminal vesicles. Within 8 hours of expression, ubiquitinated proteins accumulated, as expected, but no impact on the distribution of extracellular Wingless could be seen (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Similarly, the spread of Wingless appeared normal within tissues lacking Hrs, another ESCRT component (Extended Data Fig. 2b). To assess the role of LPPs, we modulated the activity of their receptors (Lpr1 and Lpr2) by gain and loss of function manipulations. Overexpression of the Lpr2E isoform (for a period of 36 hours) depleted available Lipophorin from the extracellular space (Extended Data Fig. 2c) but did not impact extracellular Wingless levels (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Conversely, deletion of both Lpr1 and Lpr2 also had no effect on extracellular or total Wingless, despite perturbing LPP uptake (Extended Data Fig. 2e).

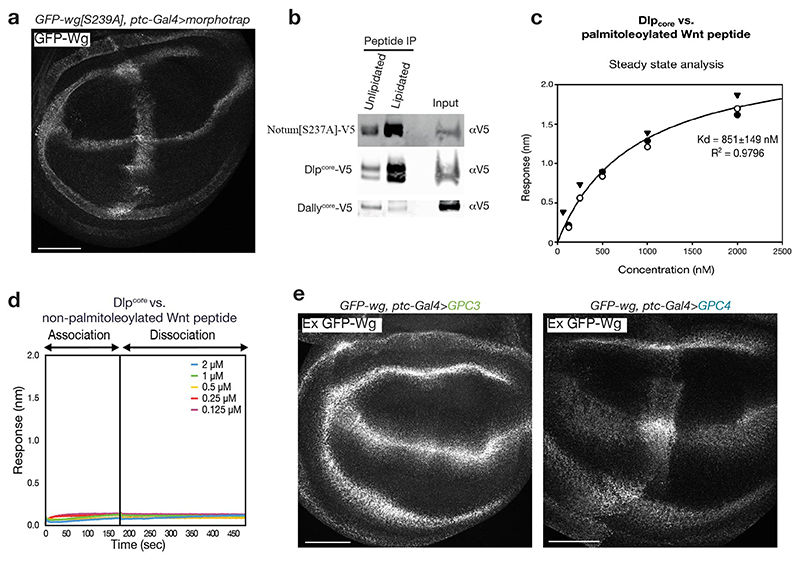

One alternative model for Wnt transport involves SWIM, a lipocalin that solubilizes Wingless in S2 cell culture medium6. To confirm an initial RNAi-based assessment of SWIM’s role (Extended Data Fig. 3a), we generated a genomic deletion that removes the entire coding region (SWIMKO) (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Homozygotes, lacking all gene function, were healthy and fertile with no apparent phenotype. Moreover, the distribution of total and extracellular Wingless was indistinguishable in SWIMKO homozygotes and control wing imaginal discs (Extended Data Fig. 3c). No change in the Wingless target gene Distal-less was observed (Extended Data Fig. 3c). We conclude that SWIM is entirely dispensable for Wingless transport although we cannot exclude a possible redundant role, say in combination with another lipocalin. In summary, our analysis so far has provided evidence against all the previously proposed mechanisms of Wnt transport, except for that involving cytonemes15, for which specific genetic tools are lacking. We therefore set out to re-investigate the role of glypicans, a class of proteins known to modulate the extracellular distribution of Wnt13,14.

A subset of glypicans bind the Wnt lipid

Extensive genetic analysis has demonstrated the role of the Drosophila glypicans Dally and Dlp in ensuring proper extracellular distribution of Wingless13,14,16. Indeed, Wingless is markedly reduced at the surface of cells lacking both glypicans (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Mutations in sulfateless, which impair the addition of heparan sulfate (HS) chains on glypicans, also lead to a strong reduction in extracellular Wingless, and phenocopy loss of Wingless signalling16. This is consistent with Wnts binding HS chains17, which decorate both Dlp and Dally. Intriguingly though, loss of Dlp has a more marked impact on extracellular Wingless than loss of Dally (Fig. 1b, c). Dlp binding to Wingless has been reported to involve two sites: one involving the HS chains and the other, the protein core13. We considered the possibility that the core site could mediate the elusive interaction that shields the palmitoleate of Wnt.

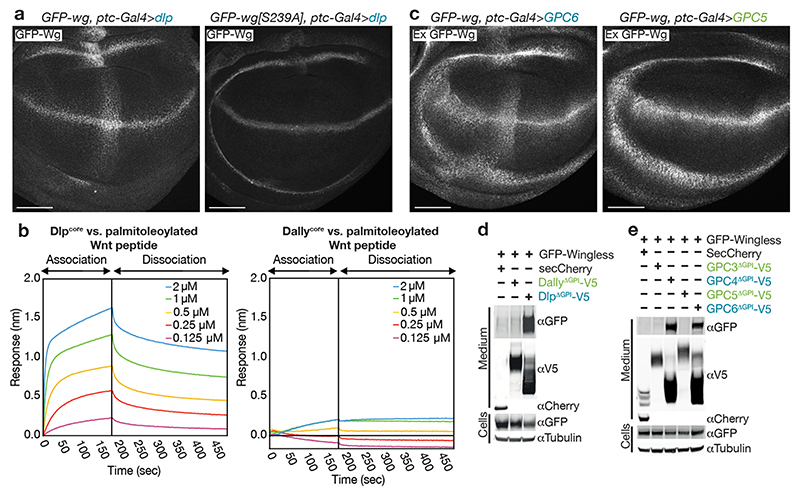

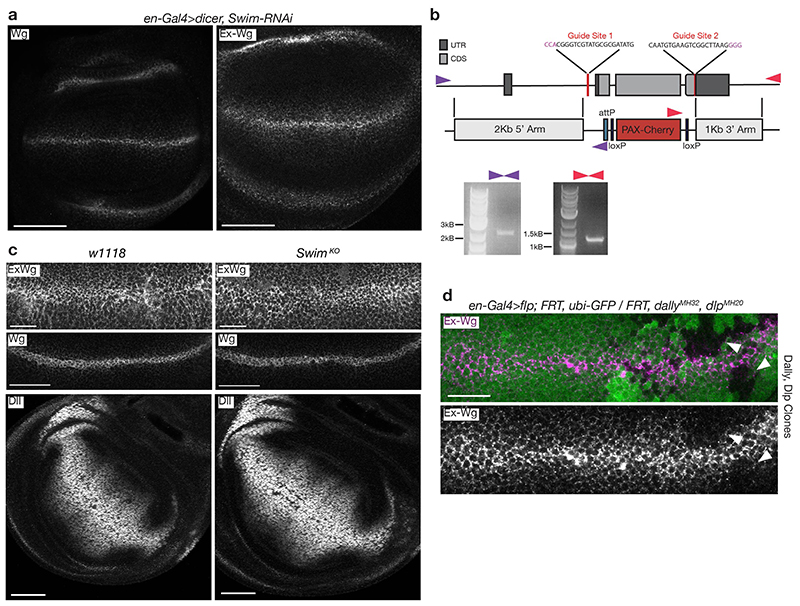

We first asked to what extent Wingless needs to be lipidated in order to bind Dlp in vivo by comparing the ability of overexpressed Dlp to trap palmitoleoylated and non-palmitoleoylated Wingless at the surface of imaginal discs cells. Dlp overexpressed in a stripe that transects the normal stripe of wingless expression duly trapped endogenous-level GFP-Wingless (Fig. 2a). By contrast, Dlp did not detectably trap GFP-Wingless[S239A], even though this unlipidated form of Wingless is secreted14,18,19 and trappable by Vhh4-CD8 (morphotrap) (Extended Data Fig. 4a). We next assessed whether Dlp has standalone palmitoleate-binding activity by measuring its interaction with palmitoleoylated and control unlipidated peptide (both biotinylated). Catalytically dead Notum, which has a marked preference for the palmitoleoylated peptide20 served as a positive control. Dlpcore (the minimal globular protein core lacking the GPI anchor and HS chains) also bound preferentially to the palmitoleoylated peptide while Dallycore had no such activity (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Prompted by these findings, we purified Dlpcore and Dallycore and investigated their binding properties by biolayer interferometry (BLI). Dlpcore bound the palmitoleoylated version with sub-micromolar affinity (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 4c) but had no detectable affinity for the non-palmitoleoylated peptide (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Dallycore showed no measurable interaction with palmitoleoylated peptide (Fig. 2b). We conclude that Dlp, but not Dally, has palmitoleate-binding activity.

Figure 2. A subset of glypicans bind palmitoleate.

a) Dlp driven by ptc-Gal4 (transversal to Wingless stripe) captures GFP-Wingless but not GFP-Wingless[S239A]. The experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results. Scale bars represent 50μm b) Representative reference-subtracted BLI traces of Dlpcore and Dallycore tested against biosensors loaded with palmitoleoylated peptides (sequence from human Wnt7a, chosen because of improved solubility relative to the Wingless sequence). Only the Dlpcore/palmitoleoylated peptide pair gave a signal. The experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results. c) Human GPC6 (Dlp family), but not human GPC5 (Dally family), expressed with ptc-Gal4 captured GFP-Wingless at the cell surface. Scale bars represent 50μm. d, e) Members of the Dlp, but not Dally, family stabilise GFP-Wingless in solution. S2 cells, cultured in serum free medium, were co-transfected with GFP-Wingless and non-membrane tethered (ΔGPI) V5-tagged forms of the indicated glypicans, or a secreted form of Cherry (negative control). Media were collected and concentrated 20-fold and the amount of Wingless in solution was determined by Western blot. Note that these proteins could be sulfated, which may contribute to their solubilizing activity. Dlp family members run at lower sizes than predicted, perhaps because of processing by furin. The experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results.

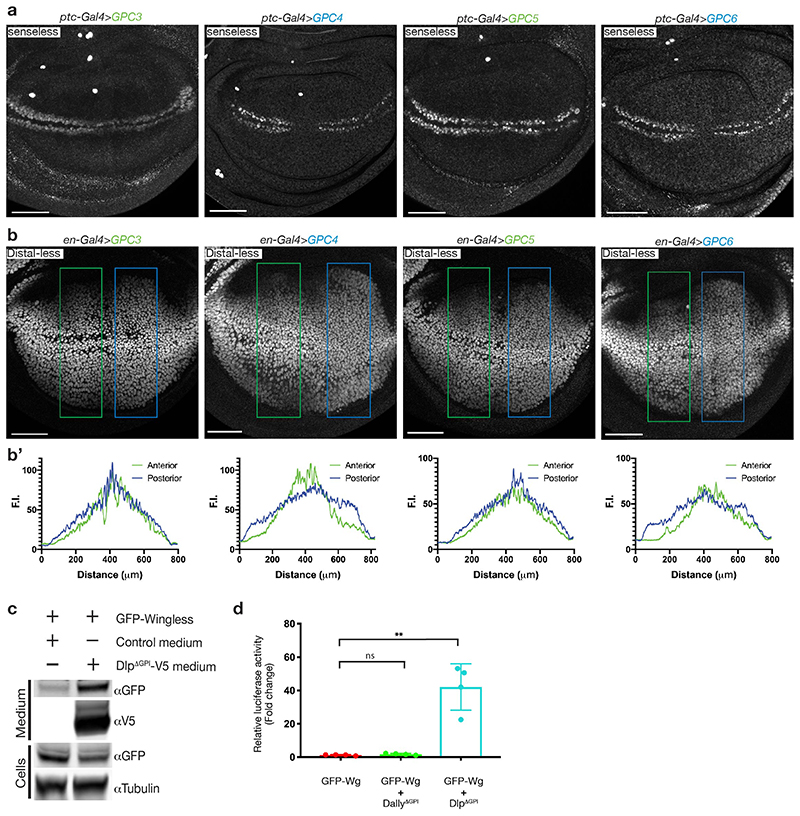

Sequence conservation shows that the six human glypicans can been distinguished according to their homology to Dlp or Dally. We expressed two of each class in wing imaginal discs. Of these, hGPC4 and hGPC6 (homologous to Dlp) trapped Wingless while hGPC3 and hGPC4 (homologous to Dally) did not (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Fig. 4e). Therefore, lipid binding activity seems to be a hallmark of the Dlp class of glypicans. Overexpressed Dlp has previously been shown to have biphasic activity in wing imaginal discs13,14, inhibiting the high target gene senseless, but extending the range of the low target gene distal-less. This could be explained if Dlp competed with Frizzled for lipid binding (decreasing signalling) while at the same time promoting long range transport by shielding the Wingless lipid. Tellingly, hGPC4 and hGPC6, but not hGPC3 and hGPC5, displayed a similarly biphasic activity (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). It appears therefore that human glypicans of the Dlp family could modulate the extracellular behaviour of Wnts through their palmitoleate-binding activity.

Solubilisation of Wingless by glypicans

Soluble Wnt cannot be recovered from serum-free medium conditioned by Wnt-expressing cells1,6,21. This is likely because of the absence of an activity that shields the palmitoleate. Indeed, addition of lipid-binding proteins, such as Afamin or SWIM, to the culture medium enables the release of soluble Wnt6,22. To confirm the lipid-binding activity of Dlp and mammalian Dlp orthologs, we tested whether they too could solubilize Wingless. S2 cells were induced to co-express secreted forms of glypicans (lacking their membrane anchor, ΔGPI) and GFP-Wingless in serum-free medium. While DlpΔGPI allowed large amounts of GFP-Wingless to be recovered in the supernatant, DallyΔGPI did not (Fig. 2d). A similar effect was seen upon addition of DlpΔGPI in the culture medium of GFP-Wingless-expressing cells (Extended Data Fig. 5c), showing that co-secretion is not needed for DlpΔGPI to solubilise Wingless. Similarly, secreted hGPC4 and hGPC6 solubilized GFP-Wingless while secreted hGPC3 and hGPC5 did not (Fig. 2e). Solubilization enables signalling since co-expression with Dlp was needed for transfected GFP-Wingless to activate a luciferase-based reporter (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Accordingly, an unidentified HSPG shown previously to stabilise Wnt activity21 is probably a Dlp-class glypican. We conclude that glypicans of the Dlp family bind palmitoleate and thus contribute to the release of signalling-competent Wnt.

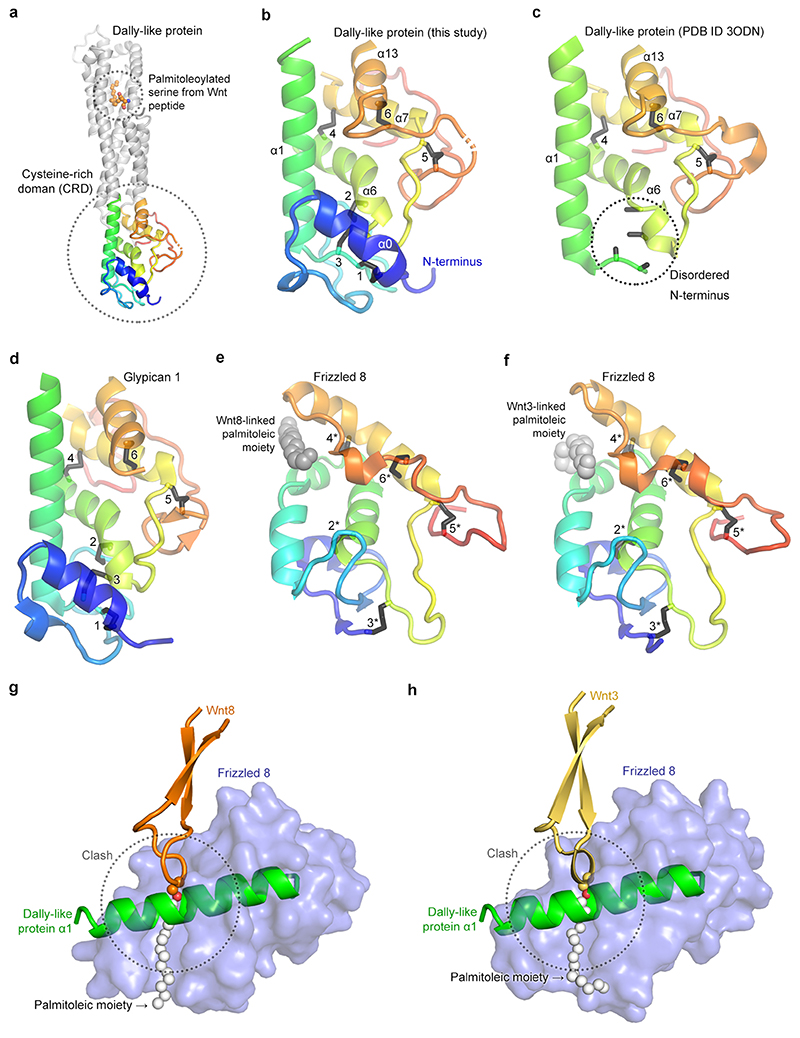

Palmitoleate-bound conformation of Dlp

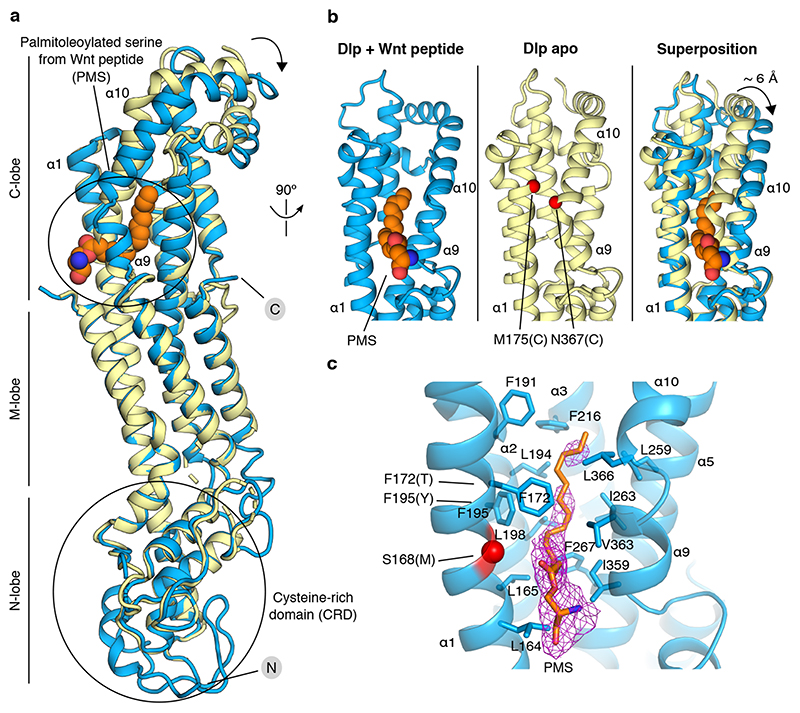

We set out to identify the molecular determinants of palmitoleate binding by the Dlp protein core. The crystal structure of Dlpcore has been reported previously23 and structural comparison has suggested that its N-terminal region is distantly related to the extracellular cysteine-rich domain (CRD) of the Frizzled family of Wnt receptors24. Given that the Frizzled CRD (FzdCRD) provides a groove-like binding site for palmitoleate3, we first looked for the equivalent groove in the uncomplexed (apo) structure of Dlpcore. Superposition of the structure of apo Dlpcore onto those of FzdCRD – Wnt complexes3,25 showed that, in Dlp, the CRD is more compact and the putative binding groove shallower (Extended Data Figure 6a-f). Notably, glypican CRDs contain an additional α-helix that is located transversally to the entrance of the groove, thereby blocking lipid insertion (Extended Data Figure 6g-h). This holds for structures of Dlp and hGPC126.

The groove-blocking helix of the glypican CRD architecture renders an analogy with the palmitoleate-binding properties of the Frizzled CRDs untenable. We therefore sought to discover the site of palmitoleate-binding in Dlpcore by direct experiment. We determined a 2.21 Å resolution crystal structure for Dlpcore in complex with a palmitoleoylated peptide. The overall structure of uncomplexed Dlpcore 23 is conserved in the complex, with a global mainchain RMSD of 1.98 Å (for 355 equivalent Cα pairs) (Fig. 3a). Some additional portions of the Dlpcore N-terminal segment were visible. These include an α-helix, which we named αH0 (for helix nomenclature see Extended Data Fig. 7a) and a 30-residue unstructured loop, similar to that seen in the published structure of hGPC126. However, the region corresponding to the palmitoleate-binding groove of FzdCRD remains occluded by the transversal α-helix (αH1) (Extended Data Fig. 6g-h). Crucially, additional electron density, consistent with a palmitoleate acyl chain (see Methods and Extended Data Fig. 8), was present on the opposite side of the Dlpcore, in the so-called C-lobe23. Well-ordered electron density revealed the acyl chain, the ester bond with associated serine sidechain and the serine mainchain of the palmitoleoylated peptide. The remainder of the peptide lacks a well-defined conformation in the complexed structure. Most of the interactions between Dlp and the Wnt peptide are hydrophobic and involve the palmitoleate, consistent with our biophysical and biochemical data showing the interaction requires the lipid moiety.

Figure 3. Structural basis of glypican-Wnt peptide interaction.

a) Superposition between Dlpcore apo structure (PDB ID: 3odn, pale yellow) and Dlpcore in complex with human Wnt7a palmitoleoylated peptide (marine). The palmitoleoylated serine (PMS) from Wnt7a peptide is depicted in spheres in atomic colouring (C: orange, N: blue, O: red). N- and C-termini are indicated. The black arrow indicates domain movement of the C lobe between apo and palmitoleoylated Wnt7 peptide-bound form. b) Close-up view of the Dlp C-lobe, revealing the conformational rearrangement of helices α9 and α10 opening the Wnt binding pocket. Dlp-M175 and -N367 mutated to cysteines to form a disulphide bridge to interfere with Wnt binding are indicated by red spheres. c) Close-up view of the lipid-binding pocket. Stick representation of residues lining the binding pocket (located within a 4.5 Å range from the Wnt peptide lipid for hydrophobic interactions). The red sphere indicates the site of one of the mutations predicted to interfere with Wnt binding (S168M). The positions of the F172T/F195Y mutations are also labelled. The Fo-Fc omit electron density map for the Wnt peptide palmitoleate is shown in purple chicken wire presentation, contoured at 2.5 σ.

Superposition of the apo and complexed Dlpcore structures revealed that palmitoleate binding is associated with a conformational rearrangement in which helix αH9 and αH10 tilt away from the opposing helix, αH1, to generate a substantial shift in position (~ 6 Å between apo and complexed structures at P365). An analysis of lattice contacts with neighbouring molecules indicated that the rearrangement was unlikely to result from the crystal environment (see Methods). This movement opens a tunnel-like cavity to accommodate the palmitoleate (Fig. 3b). The cavity is lined with hydrophobic residues contributed by six C-lobe α-helices (L164, L165, F172 of αH1; F191, L194, F195, L198 of αH2; F216 of αH3; L259, I263, F267 of αH5; I359, V363 of αH9 and L366 of αH10, see Fig. 3c). The sixteen-carbon (C16) acyl chain of the palmitoleate adopts an extended conformation resembling those reported for the Wnt-attached lipid in FzdCRD – Wnt complexes3,25, but markedly different from that observed for lipid-binding to Notum20, which requires a kink in the palmitoleate (at the C9-C10 cis double bond). Notably, the palmitoleate only occupies the narrower, top part of the cavity generated by the conformational change in complexed Dlpcore, leaving substantial space in the bottom part of the cavity (Extended Data Fig. 7b).

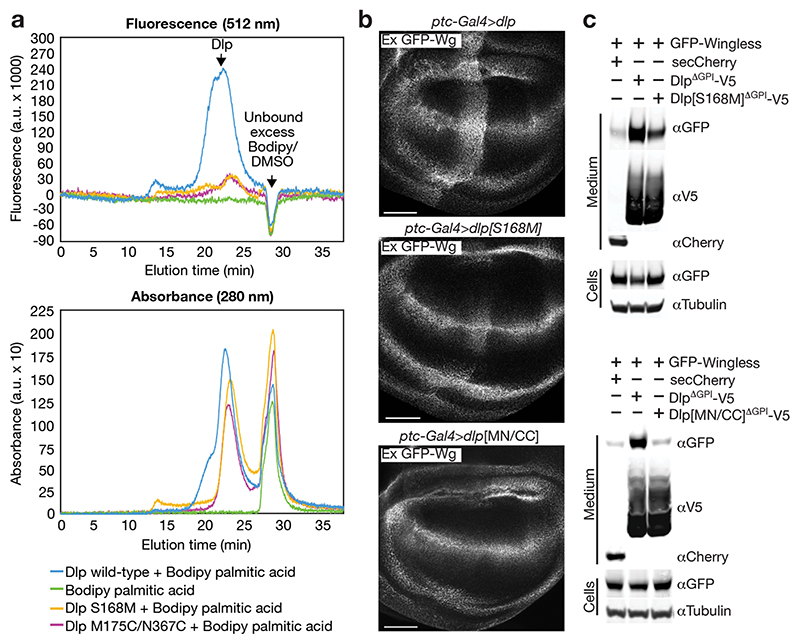

Mutations impairing palmitoleate-binding

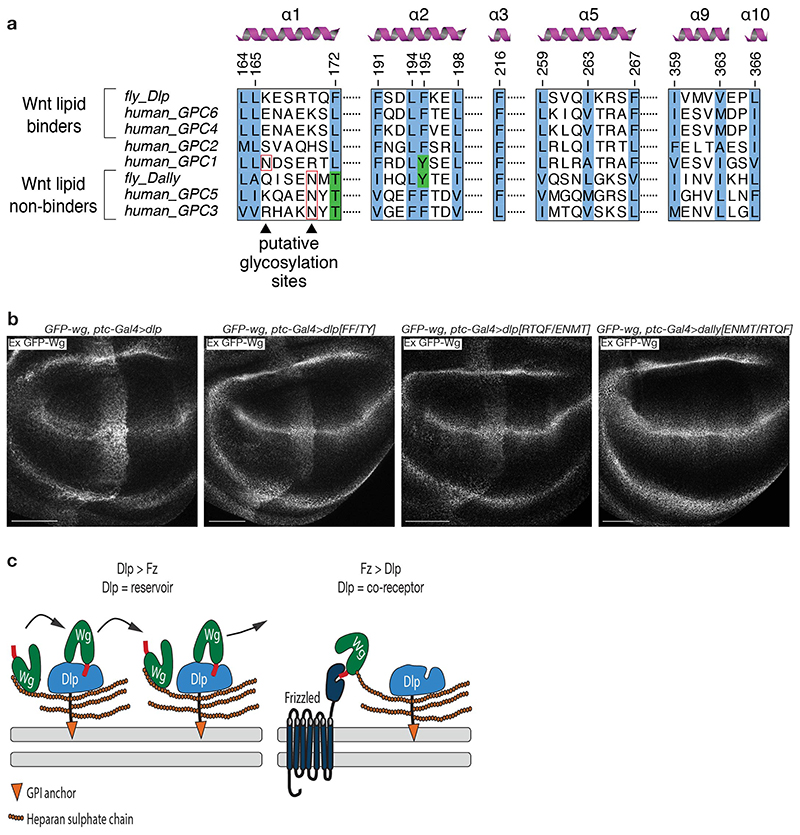

To functionally validate our structural findings, we designed Dlp mutants to interfere with Wnt binding (Fig. 3b, c). We initially aimed to hamper lipid insertion into the cavity either by introducing a bulky residue (S168M) at the entrance, or by engineering a disulphide bridge to prevent αH10 and αH1 from coming apart and hence locking Dlp in the closed, apo conformation (N367C on αH10 and M175C on αH1). As a first step, Fluorescence-detection Size Exclusion Chromatography (FSEC) was used to assess the binding of purified Dlpcore variants to bodipy 505/512-labelled palmitic acid. Dlpcore (as recognised by the 280nm protein peak) co-eluted with bodipy fluorescence, indicating binding and hence some level of promiscuity in its lipid-binding activity. As expected, binding to bodipy-palmitate was substantially reduced for both mutant proteins (Fig. 4a). These proteins were also impaired in their ability to trap endogenous Wingless in vivo, albeit to different extents; of the two, only the [N367C, M175C] mutation completely abrogated in vivo trapping while Dlp[S168M]ΔGPI retained some activity (Fig. 4b). Accordingly, Dlp[S168M]ΔGPI and Dlp[N367C, M175C]ΔGPI were less efficient than wild type DlpΔGPI at solubilising GFP-Wingless in culture medium (Fig. 4c). We further used the in vivo trapping assay to investigate the functional relevance of sequence differences between Dally and Dlp (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Mutations in Dlp to replace hydrophobic residues with polar ones (Dlp[F172T, F195Y]; FF/TY), or to introduce the putative glycosylation site of Dally (Dlp[R169E, T170N, Q171M, F172T]; RTQF/ENMT), reduced trapping, though not completely (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Dally mutations that remove the predicted glycosylation site and restore the hydrophobic F (Dally[E149R, N150T, M151Q, T152F]; ENMT/RTQF) did not confer lipid-binding activity. These results suggest that the difference in Wnt-binding activity between Dlp and Dally cannot be solely ascribed to residues at the entrance or within the tunnel. Since Dlp[N367C, M175C]ΔGPI had no in vivo trapping activity (Fig. 4b), even at the high level of expression achieved by the Gal4 system, we suggest that the movement of αH10 relative to αH1, as observed in the crystal structure, is essential for tunnel formation and lipid-binding.

Figure 4. Structure-guided point mutants impair Dlp lipid interaction.

a) Representative FSEC profiles of purified Dlpcore wild-type (blue), S168M (yellow), M175C/N367C (purple) mutants incubated with bodipy-labelled palmitic acid (C16:0), showing a reduction of fluorescence emission of mutants with respect to wild-type. This is suggestive of diminished binding affinity. The fluorophore profile in absence of proteins (green) is presented as control. 280 nm protein absorbance confirms protein presence, similar elution of wildtype and mutant proteins (ruling out mis-folding artefacts) and co-elution with the fluorescent peak. The experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results. b) Dlp-HA, Dlp[S168M]-HA and Dlp[M175C/N367C]-HA were overexpressed with ptc-gal4 and wing discs stained for extracellular Wingless. Scale bars represent 50μm. The experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results. c) Dlp[S168M]ΔGPI less efficiently stabilises GFP-Wingless in solution than DlpΔGPI, while Dlp[M175C/N367C] ΔGPI has virtually no solubilisation activity. S2 cells, cultured in serum free medium, were co-transfected with GFP-Wingless and either V5-tagged Dlp[S168M] ΔGPI, Dlp[M175C/N367C] ΔGPI, DlpΔGPI, or a secreted Cherry. Medium was collected and concentrated 20-fold and the amount of wingless in solution determined via Western blot. The experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results.

Discussion

Based on various lines of evidence against the possible roles of exosomes, lipoprotein particles and SWIM in the spread of Wingless, we re-examined the binding of Wingless to glypicans. We found that, of the two glypicans encoded by the Drosophila genome, Dlp, but not Dally, has palmitoleate-binding activity. This activity is conserved among human glypicans of the Dlp class and is not present among human homologs of Dally. We suggest that Dlp-class glypicans have evolved lipid-binding activity to shield the lipid of Wnts, and possibly, that of other signalling molecules such as palmitate and/or cholesterol on Hedgehog family members. As we showed, Dlp’s core (devoid of HS chains) can sequester the palmitoleate moiety of Wnt peptides by forming a tunnel-like binding cavity. A combination of differences between Dlp and Dally, such as the nature of residues at the entrance and within the cavity, as well as structural features that allow αH9 and αH10 to shift relative to αH1, could account for the lipid-binding activity of Dlp-class glypicans.

Glypicans of the Dlp class are not the only extracellular lipid-binding proteins. For example, Drosophila Frizzled3, a decoy receptor of Wingless27 has been shown to hold signalling-competent Wingless at the cell surface28. And secreted Frizzled related proteins (sFRPs) are known to aid Wnt diffusion in vertebrates29. Thus, a number of extracellular proteins have the capacity to shield the palmitoleate of Wnt. We suggest nevertheless that several features of Dlp-class glypicans make them particularly suitable for Wnt transport along epithelia. Their GPI anchor facilitates rapid diffusion within the cell membrane while ensuring retention in the plane of the epithelium. Moreover, dual binding, through long HS chains and the hydrophobic tunnel, could enable handover from one Dlp-class glypican to another facilitating cell-to-cell transfer (Extended Data Fig. 9c). At some frequency, Wnts would transfer from Dlp-class glypicans to Frizzled receptors to initiate signalosome assembly, as previously suggested (see Fig. 5D in reference 14). Although Dally is not essential for Wingless activity in Drosophila, it must contribute since the phenotype of dally dlp double mutants is stronger than that of the single dlp mutant (partial redundancy)13,14,30,31. It is likely that Dally-class glypicans bind Wnts via their HS chains. However, because they lack lipid-binding activity, the glypicans of this class would promptly off-load their cargo to a Frizzled receptor, thus serving only as co-receptors. Our results suggest that Dlp-class glypicans constitute an easily accessible reservoir of signalling-competent Wnt at the surface of signalling cells. In chick embryos, neural crest cells have been shown to carry and deliver Wnts at a distance in a GPC4-dependent manner32, suggesting that this reservoir can be brought to distant sites by cell migration. Cytonemes, which are coated with glypicans33 could similarly boost the mobility of the Wnt reservoir by allowing cell membranes carrying signalling-competent Wnt to reach distant sites more rapidly. The capacity of this reservoir could readily be modulated by changes in expression or activity of Dlp class glypicans, perhaps explaining why the range of Wnts differs in various contexts.

Methods

Immunostaining and microscopy

The following primary antibodies were used: guinea-pig anti-Senseless (1:1000, gift from H. Bellen), rabbit anti-V5 (1:500, Cell Signalling), mouse anti-V5 (1:500, Invitrogen), rabbit anti-GFP (1:500, Abcam), mouse anti-Wingless (1:200, Hybridoma bank), anti-Hrs (1:250, DSHB), anti-ApoL (1:1000, gift from S. Eaton), rat anti-HA (1:250, Roche, 3F10), anti-Ubiquitin (1:1000, EMD Millipore), guinea-pig anti-Distal-less (1:1000, gift from Richard S. Mann). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa 488, Alexa 555 and Alexa647 (1:500, Molecular Probes). Total and extracellular immunostaining of imaginal discs was performed as previously described. Imaginal discs were mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and imaged using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope. Confocal images were processed with ImageJ (N.I.H) and Photoshop CS5.1 (Adobe). Images were analysed using ImageJ to determine Mander’s overlap coefficient and Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Colocalization was measured where the morphotrap expression domain and the domain of GFP-Wingless overlap. Images were manually thresholded to remove background signal.

Drosophila husbandry and clone induction

All crosses were performed at 25°C except those to generate discs shown in Extended Data Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 2a, 2c and 2d, where larvae were reared at 18°C, the Gal80ts permissive temperature, and then shifted to 29°C, the restrictive temperature for the indicated time (see figure legends).

Drosophila genotypes

All lines are available upon request. Detailed Drosophila genotypes are listed Supplementary Table 1.

Expression vectors for cultured Drosophila cells

Drosophila S2 or S2R+, obtained from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Centre (DGRC), were cultured at 25°C in Schneider’s medium + L-glutamine (Sigma) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies) and 0.1 mg/mL Pen/Strep (Life Technologies). Cell lines were not authenticated, but were tested for, and free from, mycoplasma. To generate plasmids expressing V5-tagged forms of DlpΔGPI and Dlpcore, amino acids 53-723 and 53-622 of Dlp was amplified from pOT2-Dlp (DGRC gold collection) adding a V5 tag (GKPIPNPLLGLDST) at the C-terminus and a BIP-signal peptide at the N-terminus and inserted into pMT-V5-HisA (ThermoFisher). For Dlp[S168M]ΔGPI-V5 a gene fragment encoding a region around the point mutation was generated (Integrated DNA Technologies) and subcloned into pMT-Dlp ΔGPI-V5. To generate plasmids expressing V5-tagged DallyΔGPI and Dallycore, amino acids 1-600 and 1-546 of Dally were amplified from pUAST-secDally-Myc (DNA from Nakato H.) adding a V5 tag (GKPIPNPLLGLDST) at the C-terminus. SecCherry was generated by adding BIP-signal peptide at the N-terminus and inserting it into pMT-V5-HisA. To generate V5-tagged Notum[S237A], Notum[S237A] cDNA was amplified, adding a V5 tag (GKPIPNPLLGLDST) at the C terminus and cloned into pMT-V5-HisA. To generate pMT-GFP-Wg, GFP-IgG2 linker was placed after the signal peptide of Wingless. To generate GPC3ΔGPI-V5 amino acids 1-535 were amplified from a GPC3 (NM_004484) human cDNA clone (Origene) adding a V5 tag at the C-terminus. To generate GPC4ΔGPI-V5 amino acids 1-487 were amplified from a GPC4 (NM_001448) human cDNA clone (Origene) adding a V5 tag at the C-terminus. To generate GPC5ΔGPI-V5 amino acids 1-528 were amplified from a GPC5 (NM_004466) human cDNA clone (Origene) adding a V5 tag at the C-terminus. To generate GPC6ΔGPI-V5 amino acids 1-529 were amplified from a GPC6 (NM_005708.3) human cDNA clone (Sino Biological Inc.) adding a V5 tag at the C-terminus.

Generation of transgenic flies

The SwimKO line was generated by deleting all three coding exons depicted in Extended Data Fig 2e. The regions were replaced with a PAX-Cherry selection cassette, which was used to identify potential candidates, subsequently confirmed by PCR. The KO line is homozygous viable and fertile with no apparent morphological phenotype. Two variants of morphotrap were generated. The nanobody Vhh4, preceded by a BIP signal peptide, was cloned in frame with the transmembrane region of CD8 and an intracellular HA-tag and inserted into the pUAST vector, lines on the second and third chromosome were subsequently generated by random integration. The nanobody LaG16 was cloned in frame with the type II transmembrane protein NRT with a Myc-tag as a spacer to generate NRT-Myc-LaG16, which was cloned into pUAS-attB and inserted into the attP2 landing site. GFP-Wingless[S239A] was generated by inserting full-length GFP-wg[S239A] cDNA along with 135 bp of 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and 1,200 bp of 3′ UTR into RIV{mini-white} and reintegrating it into the wgKO line 9. The GFP was placed after the signal peptide and an IgG2 linker was inserted after the GFP. UAS-attB vectors encoding GPC3, GPC4, GPC5 and GPC6 were generated by amplifying coding regions from cDNA clones (see expression vectors for cultured Drosophila cells for more info on cDNA clones) and adding a V5 tag immediately after the signal peptides. The resulting UAS-attB vectors were inserted into the attP2 landing site. UAS-DlpΔGPI-V5 was generated by sub-cloning DlpΔGPI-V5 from pMT-DlpΔGPI-V5 into the UAS-attB vector and inserting it into the attP2 landing site. UAS-Dlp[S168M] was generated by sub-cloning a region encoding Dlp[S168M] from pMT-Dlp[S168M]ΔGPI-V5 into UAS-Dlp-HA (from Stephen Cohen) and inserting it into the attP2 landing site. UAS-Dlp[M175C/N367C]-HA, UAS-Dlp[F172T/F195Y]-HA and UAS-Dlp[R169E/T170N/Q171M/F172T]-HA were generated by sub-cloning gene fragments (synthesized by Integrated DNA technologies) altered to encode the relevant mutations into UAS-Dlp-HA. UAS-Dally[E149R/N150T/M151Q/T152F]-HA was generated by sub-cloning a gene fragment (synthesized by Integrated DNA technologies) altered to encode the relevant mutations into pAct-Dally-HA and subsequently sub-cloning into UAS-attB. All Dlp and Dally transgenes were inserted into the attP2 landing site. Transgenic lines were generated in house or with BestGene Inc.

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

Cell lysates were produced using Triton Extraction Buffer (TEB): 50 mM Tris pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton-X100. Cells were incubated in TEB for 10 min on ice then spun at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to remove remaining cell debris. Samples were run on 4-12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen) with MES buffer. Proteins on gel were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane using Biorad gel transfer System (Invitrogen). The membranes were washed with dH2O and blocked with 5% skimmed milk in 0.1% tween-20 PBS (PBS-T) for 30 min at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (mouse monoclonal anti-V5 (Life Technologies, 1:5000), rabbit anti-GFP (Abcam, 1:5000), anti-Beta-Tubulin (DSHB, 1:2000) and anti-Cherry (Abcam, 1:3000)) diluted in 5% milk PBS-T overnight at 4°C and washed with PBS-T 3 times before incubation with 680RD or 800CW conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-mouse or anti-rabbit; LI-COR, 1:7000). Membranes were washed again in PBS-T and 0.02% SDS, developed using an Odyssey Clx western blotting detection system (LI-COR). Uncropped Western blot images can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1.

For peptide immunoprecipitations S2 cells were transiently transfected with either Dlpcore-V5, Dallycore-V5 or Notum[S237A]-V5. 72 hours later medium was collected and spun at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. Biotinylated palmitoleoylated and biotinylated non-palmitoleoylated Wingless peptides resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 35 mM NaCl and 10% DMSO were added to the cleared medium at a final concentration of 10μM and incubated for 8 hours at 4 degrees. Neutravidin beads were added and incubated overnight at 4 degrees. Beads were then washed in wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 35 mM NaCl) four times and protein was subsequently eluted from the beads by boiling in LDS sample buffer for 5mins.

Topflash signalling assay

S2R+ cells were plated in 60cm dish and transfected with 1μg of a plasmid containing a Wingless-responsive promoter driving Firefly luciferase and a ubiquitous Copia promoter driving Renilla luciferase (made by Cyrille Alexandre). After 48 hours the S2R+ cells were counted and 1×106 cells were plated in each well of a 12 well plate and allowed to attach. After 6 hours the medium was removed and replaced with concentrated conditioned medium (20×). After 24 hours of treatment, the cells were lysed using cold passive lysis buffer (Promega), Firefly and Renilla luciferase levels were measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and the Firefly/Renilla ratio calculated to give the Wingless signalling activity. Each condition was tested in triplicate and the experiment was repeated four times.

Large scale expression and purification of Dlpcore wild-type and Dallycore

The cDNA coding for Drosophila melanogaster Dlpcore (residues D74-Q617, UNIPROT ID: Q9VUG1; note that this is slightly different from the Dlpcore described above, P52-Y622) was cloned into pHR-STRUBI-3c-Twin-Strep-IRES-EmGDP: the plasmid encodes the protein of interest adding a Human Rhinovirus (HRV) 3C Protease-cleavable Twin-Strep tag at the C-terminus, and allows both transient expression and lentiviral-based transduction of target cells36.

Dlp contains one canonical and one cryptic furin cleavage site at position 397 and 437, respectively. To produce homogenous batches of protein and to account for potential effects of furin processing on lipid binding, two protein forms were generated, one wild-type form containing the native furin cleavage site and one form where both furin sites were destroyed (K398Q, K399A, R402Q, R438Q, R441A). No difference in lipid binding behaviour was observed between these two forms. For crystallisation purposes, the furin mutant form was used.

The protein was expressed – secreted in the culture medium - either by transient transfection of HEK293S GnTI(-) cells or by lentiviral transduction of HEK293S GnTI(-) TetR cells37 (which allow doxycycline-controlled inducible expression) according to published protocols36,38. In the latter case, expression was induced using 1 ug/mL of doxycycline for 96 hours at 37 °C. For transient transfection, conditioned media was collected seven days post-transfection.

In both cases, harvested conditioned media was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 200 mM NaCl using using a QuixStand™ benchtop system (GE Healthcare) connected to a 60 cm Xampler Cartridge (GE Healthcare) with a 10 kDa nominal MWCO. Initial purification was performed by Strep-tag™ affinity chromatography (StreptactinXT High Capacity column, IBA Lifesciences). Briefly, the protein was loaded overnight with continuous circulation on the column, before being eluted in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM biotin. The protein was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) (Superdex 200 Increase 10_300 GL column, GE Healthcare) in a final buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 35 mM NaCl. Between the affinity chromatography and SEC steps, the Twin-Strep-tag was removed by incubation for 48 hours at 4 °C with HRV 3C Protease, added at a 1:50 (w/w) protease:protein ratio.

Drosophila melanogaster Dallycore (residues 65-541, Uniprot ID: Q24114), fused C-terminally with a hexa-histidine (6xHis) tag, was cloned into the pHLsec vector and expressed by transient transfection in HEK293T cells in the presence of the class I α-mannosidase inhibitor, kifunensine38,39. Conditioned media was collected five days post-transfection. Media was concentrated and diafiltrated as before into 25 mM phosphate pH 8, 250 mM NaCl. The protein was incubated with TALON® beads for 1 hour at 16°C. Beads were washed with 25 mM Phosphate pH 8, 250 mM NaCl, followed by washes in wash buffer containing 5 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted in wash buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. Samples were subjected to SEC using a Superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl.

Man(5)GlcNAc(2) and Man(5–9)GlcNAc(2) residual glycosylation produced by expression in GnTI(-) HEK293S or by HEK293T cells with kifunensine, respectively, was preserved for biophysical and HPLC analysis of protein-lipid interaction, while the samples for crystallisation were further deglycosylated by in situ deglycosylation by endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase F1 treatment 39.

Peptide synthesis

Abbreviations

DCM (dichloromethane); DIPEA (N,N-diisopropylethylamine); DMAP (dimethylaminopyridine); DMF (dimethylformamide); HATU (1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate); MeCN (acetonitrile); MeOH (methanol); MMT (monomethoxytrityl); RT (room temperature); TFA (trifluoroacetic acid); TIS (triisopropylsilane);

General Information

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources (VWR, Fisher Scientific, Novabiochem, Fluorochem) and used without further purification.

Synthesis of dmWg S239 ox Bio (CH3CO-KC(S-)HGMSGSC(S-)TVLK-(EDA)-Bio) and dmWg S239 (C16:1) ox Bio (CH3CO-KC(S-)HGMS(-C=0-(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)5CH3)GSC(S-)TVLK-(EDA)-Bio)

Solid phase synthesis took place on an Activotec P-11 peptide synthesizer (Activotec) using a Fmoc-Biotin NovaTag ™ resin (0.2 mmol; Merck) and N(α)-Fmoc amino acids, including Fmoc-Ser-OH (Merck). Fmoc-Ser-OH was incorporated at the palmitoleoylation site. HATU was used as the coupling reagent with 5- fold excess of amino acids. Acetylation of the N terminal of the peptide took place on the synthesiser by activation of acetic acid. Following chain assembly, the peptidyl resin was split into two portions of approximately one third and two thirds.

For dmWg S239 ox Bio the peptide was cleaved from the resin and protecting groups removed by addition of a cleavage solution (95% TFA, 2.5% H2O, 2.5% TIS). After 2 h, the resin was removed by filtration and peptides were precipitated with diethyl ether on ice. The peptide was isolated by centrifugation, then dissolved in H2O and freeze dried overnight. Next, disulphide bridge formation was as follows. Clear-Ox™ (Peptides International) resin (3 eq, 0.109 mmol, 330 mg of 0.33 mmol/g) was conditioned by swelling in DCM for 40 min, then washed with DMF, MeOH and water. The peptide (0.036 mmol, 60 mg) was dissolved in 10 mL of deionised water, added to the resin, then reacted at RT with gentle agitation for 2 days. Following filtration to remove the resin and freeze drying, portions of the peptide were purified on a C8 reverse phase HPLC column (Agilent PrepHT Zorbax 300SB-C8, 21.2x250 mm, 7 m) using a linear solvent gradient of 10-50% MeCN (0.08% TFA) in H2O (0.08% TFA) over 40 min at a flow rate of 8 mL/min. The peak fraction was analyzed by LC–MS on an Agilent 1100 LC-MSD. The calculated molecular weight of the peptide was in agreement with the mass found. Calculated MW: 1657.65, actual mass: 1657.65.

For dmWg S239 (C16:1) ox Bio the peptidyl resin was palmitoleoylated as follows. Palmitoleoyl chloride (20 eq, 3 mmol, 903 uL) was added to DMF (6 mL) and the solution added to the peptidyl resin (0.15 mmol). DMAP (0.1 eq, 2 mg) was dissolved in 2.25 mL pyridine and added to resin. Following reaction at RT, 16 h, gentle agitation, the peptidyl resin was washed with 3xDMF and 2 x DCM. The palmitoleoylated peptide was cleaved from the resin and protecting groups removed by addition of a cleavage solution (95% TFA, 2.5% H2O, 2.5% TIS). After 1 h, the resin was removed by filtration and peptides were precipitated with diethyl ether on ice. The peptide was isolated by centrifugation, then dissolved in H2O and freeze dried overnight. Next, disulphide bridge formation was as follows. Clear-Ox™ (Peptides International) resin (3 eq, 0.127 mmol, 384 mg 0f 0.33 mmol/g) was conditioned by swelling in DCM for 40 min, then washed with DMF, MeOH and water. The peptide (0.042 mmol, 80 mg) was dissolved in 10 mL of deionised water, added to the resin, then reacted at RT with gentle agitation for 3 days. Following filtration to remove the resin and freeze drying, portions of the peptide were purified on a C8 reverse phase HPLC column (Agilent PrepHT Zorbax 300SB-C8, 21.2x250 mm, 7 m) using a linear solvent gradient of 5-100% MeCN (0.08% TFA) in H2O (0.08% TFA) over 40 min at a flow rate of 8 mL/min. The peak fraction was analyzed by LC–MS on an Agilent 1100 LC-MSD. The calculated molecular weight of the peptide was in agreement with the mass found. Calculated MW: 1894.33, actual mass: 1894.27.

mmWNT7A 204-213 S206 C16:1 ox Bio

NH2-K(Cys-S-) HGV(Ser-palmitoleoyl)GS(Cys-S-)TTKT-PEG-Bio

Solid phase synthesis took place on an Activotec P-11 peptide synthesizer (Activotec) using a Fmoc-PEG-Biotin NovaTag ™ resin (0.2 mmol; Merck) and N(α)-Fmoc amino acids, including Fmoc-Ser-OH (Merck) and Boc-Lys(Boc)-OH (Fluorochem). Fmoc-Ser-OH was incorporated at the palmitoleoylation site and Boc-Lys(Boc)-OH was incorporated at the N terminal. HATU was used as the coupling reagent with 5- fold excess of amino acids. the peptidyl resin was palmitoleoylated as follows. Palmitoleoyl chloride (20 eq, 1.5 mmol, 452 uL) was added to DMF (6 mL) and the solution added to the peptidyl resin (0.075 mmol). DMAP (0.1 eq, 1 mg) was dissolved in 2.25 mL pyridine and added to resin. Following reaction at RT, 16 h, gentle agitation, the peptidyl resin was washed with 3xDMF and 2 x DCM. The palmitoleoylated peptide was cleaved from the resin and protecting groups removed by addition of a cleavage solution (95% TFA, 2.5% H2O, 2.5% TIS). After 1 h, the resin was removed by filtration and peptides were precipitated with diethyl ether on ice. The peptide was isolated by centrifugation, then dissolved in H2O and freeze dried overnight. Next, disulphide bridge formation was as follows. Clear-Ox™ (Peptides International) resin (3 eq, 0.147 mmol, 700 mg 0f 0.21 mmol/g) was conditioned by swelling in DCM for 40 min, then washed with DMF, MeOH and water. The peptide (0.049 mmol, 96 mg) was dissolved in 10 mL of deionised water, added to the resin, then reacted at RT with gentle agitation for 3 days. Following filtration to remove the resin and freeze drying, portions of the peptide were purified on a C8 reverse phase HPLC column (Agilent PrepHT Zorbax 300SB-C8, 21.2x250 mm, 7 m) using a linear solvent gradient of 10-75% MeCN (0.08% TFA) in H2O (0.08% TFA) over 40 min at a flow rate of 8 mL/min. The peak fraction was analyzed by LC–MS on an Agilent 1100 LC-MSD. The calculated molecular weight of the peptide was in agreement with the mass found. Calculated MW: 1971.39, actual mass: 1969.90.

mmWNT7A 201-213 S206 ox C16:1

NH2-K(Cys-S-)HGV(Ser-16:1) GS(Cys-S-)TTKT-COOH

Solid phase synthesis took place on an Activotec P-11 peptide synthesizer (Activotec) using a Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-Wang resin LL (0.2 mmol; Merck) and N(α)-Fmoc amino acids, including Fmoc-Ser-OH, Fmoc-Cys(MMT)-OH, Fmoc-Gly-Ser(psiMe,Mepro)-OH (all Merck) and Boc-Lys(Boc)-OH (Fluorochem). Fmoc-Ser-OH was incorporated at the palmitoleoylation site and Boc-Lys(Boc)-OH was incorporated at the N terminal. HATU was used as the coupling reagent with 5-fold excess of amino acids. Palmitoleoyl chloride (18.5 eq, 3.7 mmol, 1000 uL) was added to DMF (4 mL) and the solution added to the peptidyl resin (0.075 mmol). DMAP (0.1 eq, 2.5 mg) was dissolved in 2.50 mL pyridine and added to resin. Following reaction at RT, 16 h, gentle agitation, the peptidyl resin was washed with 3 x DMF and 2 x DCM. Next disulphide bridge formation on the resin was performed as follows. Methoxytrityl was remove from the two cysteine residues by treatment of the peptidyl resin for 2 min with 10 ml of 1% TFA, 5% TIS, rest DCM, then washed with DCM. This was repeated 7 times more. Next the peptidyl resin was treated with N-chlorosuccinimide (1 eq) in 10 mL DMF for 10 min then washed with 3 x DMF and 2 x DCM. The palmitoleoylated, disulphide-bridged peptide was cleaved from the resin and protecting groups removed by addition of a cleavage solution (95% TFA, 2.5% H2O, 2.5% TIS). After 1 h, the resin was removed by filtration and peptides were precipitated with diethyl ether on ice. The peptide was isolated by centrifugation, then dissolved in H2O and freeze dried overnight. Portions of the peptide were purified on a C8 reverse phase HPLC column (Agilent PrepHT Zorbax 300SB-C8, 21.2x250 mm, 7 m) using a linear solvent gradient of 20-90% MeCN (0.08% TFA) in H2O (0.08% TFA) over 40 min at a flow rate of 8 mL/min. The peak fraction was analyzed by LC–MS on an Agilent 1100 LC-MSD. The calculated molecular weight of the peptide was in agreement with the mass found. Calculated MW: 1542.00, actual mass: 1541.85.

mmWNT7A 201-213 S206 ox C16:1

NH2-K(Cys-S-)HGV(Ser-16:1) GS(Cys-S-)TTKT-COOH

Solid phase synthesis took place on an Activotec P-11 peptide synthesizer (Activotec) using a Fmoc-PEG-Biotin NovaTag ™ resin (100 μmol; Merck) and N(α)-Fmoc amino acids, including Fmoc-Cys(MMT)-OH, Fmoc-Gly-Ser(psiMe,Mepro)-OH (all Merck) and Boc-Lys(Boc)-OH (Fluorochem). The first Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-OH was double coupled. Boc-Lys(Boc)-OH was incorporated at the N terminal. HATU was used as the coupling reagent with 5-fold excess of amino acids. Following chain assembly, disulphide bridge formation on the resin was performed as follows. Methoxytrityl was remove from the two cysteine residues by treatment of the peptidyl resin for 2 min with 10 ml of 1% TFA, 5% TIS, rest DCM, then washed with DCM. This was repeated 7 times more. Next the peptidyl resin was treated with N-chlorosuccinimide (1 eq) in 10 mL DMF for 10 min then washed with 3 x DMF and 2 x DCM. The disulphide-bridged peptide was cleaved from the resin and protecting groups removed by addition of a cleavage solution (95% TFA, 2.5% H2O, 2.5% TIS). After 1 h, the resin was removed by filtration and peptides were precipitated with diethyl ether on ice. The peptide was isolated by centrifugation, then dissolved in H2O and freeze dried overnight. Portions of the peptide were purified on a C8 reverse phase HPLC column (Agilent PrepHT Zorbax 300SB-C8, 21.2x250 mm, 7 m) using a linear solvent gradient of 10-50% MeCN (0.08% TFA) in H2O (0.08% TFA) over 40 min at a flow rate of 8 mL/min. The peak fraction was analyzed by LC–MS on an Agilent 1100 LC-MSD. The calculated molecular weight of the peptide was in agreement with the mass found. Calculated MW: 1734.99, actual mass: 1733.99.

Biolayer interferometry

Data were collected with Octet RED96 and Octet RED384 instruments (FortéBio). All steps were performed in 10 mM Tris, 35 mM NaCl, pH 8. Initially, Dip and Read Streptavidin Biosensors (FortéBio) were activated by dipping them in buffer for 10 min before starting the analysis. Sensors were then loaded with 0.05 mg/mL of biotinylated palmitoleoylated and non-palmitoleoylated human Wnt7a peptide. After baseline reference collection in wells containing only buffer, biosensors were dipped in analyte dilution series, before allowing dissociation in the same buffer wells where the baseline reference was collected. Peptide-loaded sensors tested against buffer were used for blank subtraction. Unloaded sensors dipped into the analyte dilution series were used as reference to account for non-specific binding.

Upon reference subtraction, data were analysed by the FortéBio (version 11.1) and SigmaPlot (version 14.0) data analysis software. The model used for curve fitting in kinetic and steady-state analysis was a 1:1 Langmuir binding isotherm model. Data were collected in three independent experiments.

Crystallisation, data collection, and structure determination

Purified proteins were concentrated by ultrafiltration to 3.5 mg/mL and incubated for 16 hours at 4 °C with palmitoleoylated human Wnt7a peptide (resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 35 mM NaCl and added at a final concentration of 5 mM). After incubation, 96-well crystallisation plates were set up at 20 °C using a Cartesian Technologies pipetting robot dispensing nanolitre-scale drops consisting of 100 nl of protein solution and 100 nl of reservoir solution40. Crystals appeared after 2 weeks in a variety of conditions with 20% (w/v) PEG4000 as precipitant and different pH values.

Prior to crystal freezing, crystals were additionally soaked with palmitoleoylated human Wnt7a peptide resuspended in DMSO, at a final concentration of 1 mM peptide in 10% (v/v) DMSO. The crystals were soaked for 1 hour before flash-cooling by dipping into liquid nitrogen, using mother liquor supplemented with 25% (v/v) glycerol as cryoprotectant.

Since initial crystals diffracted at 3 Å with a high degree of anisotropy in the c* dimension, optimization of the crystal growth was performed, designing a two-dimensional pH/precipitant screening matrix (5-9 pH interval using 0.1 M MMT41 buffer, 15-25% w/v PEG4000 concentration interval). The best diffracting crystals grew in 16.25% (w/v) PEG4000, 0.1 M MMT pH 9.

Data were collected at 100 K at Diamond Light Source (Didcot, UK) beamline i04 equipped with an Eiger2 X 16M detector using a wavelength of 0.9795 Å.

Data were processed using Xia242, scaled using DIALS43 and merged using AIMLESS44,45.

The structure of Dlpcore in complex with hWnt7a palmitoylated peptide was solved to a resolution of 2.21 Å by molecular replacement with PHASER46 using the previously published apo-form of Dlp (PDB ID: 3odn)23 as a search model. Iterative cycles of refinement and manual rebuilding were performed using phenix.refine 47 and COOT48. To avoid model bias, the Wnt7a peptide model was added only at the latest stages of refinement. PEG was also present in the crystallisation cocktail, however a number of reasons provided the rationale for fitting palmitoleate into the density: several types of omit maps, generated using phenix.refine and phenix.polder (see Fig. 3c and Extended Data Figure 8), show clear evidence of continuous electron density not only for the lipid part but also for the peptide moiety of the palmitoleoylated peptide; although crystallized in a different space group, PEG was also present in the crystallization cocktail of the published apo form and no conformational rearrangement and no lipid-like density is present in the latter; to fit the electron density, a fragment of PEG of the exact same dimensions as the palmitoleate would be required; the highly hydrophobic binding cavity is less compatible with a polar molecule like PEG than with a lipid. Subsequent results for mutant Dlps showing reduced in vitro and in vivo lipid binding confirmed the identification of the pocket as the palmitoleate binding unit.

SMILES for the chemical structure of the peptide was designed using CHEMDRAW and peptide model and restraints for refinement were generated by the GRADE webserver49. Refinement models were validated with MOLPROBITY50. No Ramachandran outliers are present in the final model, with 97.83% of the residues in the favoured region of the Ramachandran plot. Data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Extended Data Table 1.

Inspection of crystal contacts revealed one in the region of the conformational change, however PISA (Protein Interfaces, Surfaces and Assemblies, EMBL-EBI51 server analysis reported this to be only a minor interface (554 Å2 out of 22260 Å2 of accessible surface area), with a CSS (Complex Significance Score) of 0, indicating that it is an energetically very weak interface and therefore not be expected to trigger a significant conformational rearrangement in the structure. Structural superpositions were performed in COOT, using the LSQ algorithm. Structural figures were created by PYMOL (v.2.2.0) and assembled using INKSCAPE. Sequence alignments were generated using JALVIEW52 (v. 2.10.5). Lipid-binding cavity analysis and visualization were performed using CASTp53 and its related PYMOL plugin.

Large-scale expression and purification of mutants for in vitro binding analysis

Mutations were generated by a two-step overlapping PCR and mutants were cloned into the pHLSec vector encoding for C-terminal 6xHis and AviTag™ tags54. The mutant Dlp forms were expressed by transient transfection of GnTI(-) HEK293S, dialyzed against 20 mM Tris, pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole and initially purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (HisTrap HP, GE Healthcare). Subsequently, proteins were further purified by SEC using the same experimental setting described for the wild-type protein.

Protein – lipid binding tests by Fluorescence detection size exclusion chromatography (FSEC)

Fluorescently-labelled C16:0 palmitic acid BODIPY™ FL C16 (4,4-Difluoro-5,7-Dimethyl-4-Bora-3a,4a-Diaza-s-Indacene-3-Hexadecanoic Acid, Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with the proteins of interest for 16 hours at 4 °C in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 35 mM NaCl, 7.5% DMSO. The proteins were used at a concentration of 2 uM, and the fluorescent lipid was added at a 1:20 (w/w) protein:lipid ratio. The runs were performed at a flow rate of 0.08 ml/min.

After incubation, the samples were run on a Superose 6 Increase 3.2/200 column in a FSEC Prominence HPLC system (Shimadzu) equipped with a RF-10AXL fluorescent detector. The running buffer was 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 35 mM NaCl. The fluorescent dye was excited at 505 nM and emission registered at 512 nM; absorbance at 280 nM was also registered to compare the elution profiles with those of the fluorescence emission. BODIPY™ FL C16 in absence of proteins was run as control. Data were collected in three independent experiments.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Extracellular wingless, captured by morphotrap, colocalizes with DlpΔGPI but not exosomes or lipophorin particles.

a) A membrane tethered anti-GFP nanobody (Vhh4-CD8-HA, morphotrap), expressed in a transversal stripe with dpp-Gal4, leads to accumulation of GFP-Wingless (from a knock-in allele34) where the two expression domains overlap. The apparent gap in morphotrap expression is due to the known low activity of dpp-gal4 there. Residual expression is nevertheless sufficient to trap GFP-Wingless. b-d) Immunofluorescent localization of morphotrap-enriched GFP-Wingless and endogenous ApoL or endogenous Hrs. d) Immunofluorescent localization of morphotrap-enriched GFP-Wingless and overexpressed DlpΔGPI-V5. Here, morphotrap is expressed with dpp-LexA and DlpΔGPI-V5 with wg-Gal4. White colour indicates extensive colocalisation. DlpΔGPI-V5 expression was limited to 24 hrs with Gal80ts to avoid pleiotropic effects. e) Colocalisation was quantified where the morphotrap and GFP-Wingless expression domains intersect. Error bars show standard deviation from the mean, n=4 (DlpΔGPI-V5), n=13 (ApoL) and n=10 (Hrs), where n=number of wing discs. Scale bars represent 50μm in a and 10μm in b-d. All experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results.

Extended Data Figure 2. Genetic perturbation of exosomes or lipophorin particles does not alter the distribution of extracellular Wingless.

a) Expression of dominant negative Vps4 with hh-Gal4 in the posterior compartment (limited to 8 hrs with Gal80ts to avoid pleiotropic effects of sustained VPS4 inhibition) does not affect extracellular Wingless despite disruption of MVB formation indicated by accumulation of ubiquitin. Anterior compartment serves as a control. Dashed line denotes anterior posterior boundary. b) Expression of extracellular Wingless is largely unaffected by the loss of Hrs activity. The posterior compartment was rendered homozygous for a null hrs mutation using the indicated genotype. c-d) Overexpression of the lipophorin receptor Lpr2E-HA for 24hrs with the hh-Gal4 driver increases the uptake of ApoL in the posterior compartment but has no effect on extracellular Wingless. The anterior compartment serves as a control. e) Extracellular Wingless and ApoL in wing discs from w118 (control) or homozygotes for a deficiency that removes the two main lipophorin receptors Lpr1/2. Lipophorin uptake is reduced in the deficiency line but neither total or extracellular Wingless is altered. Scale bars represent 50μm. All experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results.

Extended Data Figure 3. Genetic perturbation of Dlp and dally but not of SWIM alters the distribution of extracellular Wingless.

a) Expression of an RNAi against SWIM in the posterior compartment (en-Gal4) does not alter extracellular or total Wingless. Scale bar represents 50μm. b) Schematic representation of the SWIM locus and the CRISPR-Cas9 strategy used to delete the gene. Successful deletion was verified by PCR using two independent primer pairs indicated by purple and red arrowheads. c) Extracellular Wingless and Distal-less expression in control (w1118) and SwimKO wing discs. Neither is altered upon SWIM deletion. Scale bars represent 50μm. d) Extracellular Wingless is reduced in clones lacking both Dlp and Dally (marked by the absence of GFP (white arrowheads). Scale bars represent 25μm. All experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results.

Extended Data Figure 4. Further evidence for the lipid binding activity of Dlp class glypicans.

a) GFP-Wingless[S239A] expressed from a knock-in allele is trapped by CD8-VHH expressed with dpp-Gal4. This result shows that GFP-Wingless[S239A] is secreted and can be captured in the extracellular space and thus serves as a positive control for Fig. 2a. Scale bars represent 50μm. b) Dlpcore and Notum[S237A], but not Dallycore, preferentially bind a palmitoleoylated peptide (sequence from the Wingless protein). Biotinylated palmitoleoylated and non-palmitoleoylated peptides were incubated with medium from S2 cells expressing Dlpcore-V5, Notum[S237A]-V5 or Dallycore-V5. Biotinylated peptides were pulled down with streptavidin beads and the extent to which Dlpcore, Notum[S237A]-V5 and Dallycore are co-pulled down was determined by western blot. A peptide-based approach was used because of difficulties associated with the production of soluble Wingless protein. Binding was estimated from the amount of protein co-pulled down from conditioned medium by streptavidin beads. c) Steady-state analysis of the Dlpcore vs. palmitoleoylated hWnt7a peptide interaction measured by BLI shown in Fig. 2b. Kd is calculated from a global fit of three independent experiments. Due to the effect of non-specific binding on the shape of the binding isotherm curves (which could not be alleviated by detergents in light of the lipid-based nature of the interaction) we could not perfectly fit a 1:1 Langmuir model, therefore the indicated apparent dissociation constant is an estimate, not an exact value. d) Representative reference-subtracted BLI traces of Dlpcore against biosensors loaded with non-palmitoleoylated peptide (sequence from relevant region of human Wnt7a). No significant binding could be detected (compare to Fig. 2b). The experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results. e) Human GPC4 (Dlp family), but not human GPC3 (Dally family), expressed with ptc-Gal4 captured GFP-Wingless at the cell surface. This panel extends the data of Fig. 2c. Scale bars represent 50μm. All experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results.

Extended Data Figure 5. Effects of Dlp class glypicans on Wingless signalling.

a) GPC4 and GPC6, but not GPC3 and GPC5, driven with ptc-Gal4 inhibit the high target gene senseless. Scale bars represent 50μm. b) GPC4 and GPC6, but not GPC3 and GPC5, expressed with en-Gal4 extend the range of the low target gene Distal-less in the posterior compartment. Scale bars represent 50μm. b’) Distal-less immunoreactivity was quantified in the indicated boxed regions and plotted separately for the anterior and posterior, where the glypicans were overexpressed. c) Dlp conditioned medium stabilises GFP-Wingless in solution. Conditioned medium from S2 cells or S2 cells expressing DlpΔGPI-V5 was added to S2 cells expressing GFP-Wingless. 12hrs later the medium was collected, concentrated 20-fold and the amount of GFP-Wingless in solution was determined via Western blot. d) Wingless solubilized by DlpΔGPI is signalling competent. Medium from cells that were mock-transfected, transfected with GFP-Wingless alone, or co-transfected with either V5 tagged DallyΔGPI or DlpΔGPI was collected, concentrated and added to S2R+ cells expressing a luciferase reporter of Wingless signaling. Error bars show standard deviation from the mean. n=4, n=independent experiments and each independent experiment was performed in triplicate. Asterisk denotes statistical significance, as assessed by an unpaired (two tailed) t-test (p=0.0011). ns denotes no statistical significance (p=0.128). All experiments were repeated independently three times with similar results.

Extended Data Figure 6. Steric clashes prevent Wnt lipid binding to glypican CRD.

Comparison of the conserved CRD architecture of: a, b) Drosophila Dlpcore structure in complex with Wnt palmitoleoylated serine from Wnt peptide. We could confirm that the DlpCRD contains the full set of canonical disulphide-bonds. c) apo Drosophila Dlpcore (PDB ID: 3odn); d) human GPC1 (PDB ID: 4ywt); e) mouse Frizzled 8 in complex with palmitoleic moiety from Xenopus Wnt8 (PDB ID: 4f0a); f) mouse Frizzled 8 in complex with palmitoleic moiety from human Wnt3 (PDB ID: 6ahy). Evolutionary conserved disulphides are shown in black and numbered. g,h) Superposition of Dlpcore CRD and mouse Frizzled 8 CRD bound to lipidated Wnt8 (g) and Wnt3 (h), showing that a conserved helix of glypican CRD sterically hinders binding of the Wnt palmitoleate.

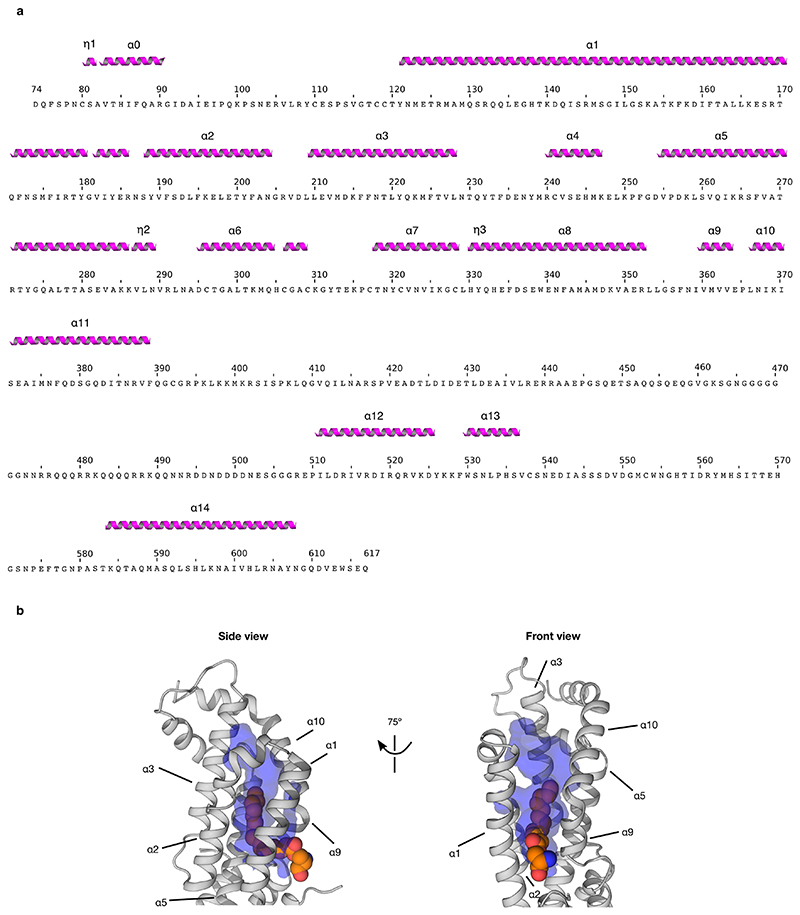

Extended Data Figure 7. Additional structural information on Dlpcore in complex with hWnt7a peptide.

a) Sequence of Dlpcore construct from the complexed structure annotated with secondary structure elements. To facilitate comparison between the complexed and apo structure, secondary structure nomenclature of the complex reflects that of the previously published apo structure (PDB ID: 3odn). α indicates alpha-helices, η indicates 310-helices. b) Side and front view of the lipid binding cavity of Dlpcore in complex with the Wnt palmitoleoylated peptide, showing the cavity extension beyond the end of the Wnt peptide acyl chain. This additional space likely accommodates the bodipy moiety of bodipy-palmitate for the assays presented in Fig. 4a. The internal volume of the cavity is coloured in blue, with the palmitoleoylated serine from the Wnt peptide represented as spheres in atomic colouring (C: orange, N: blue, O: red).

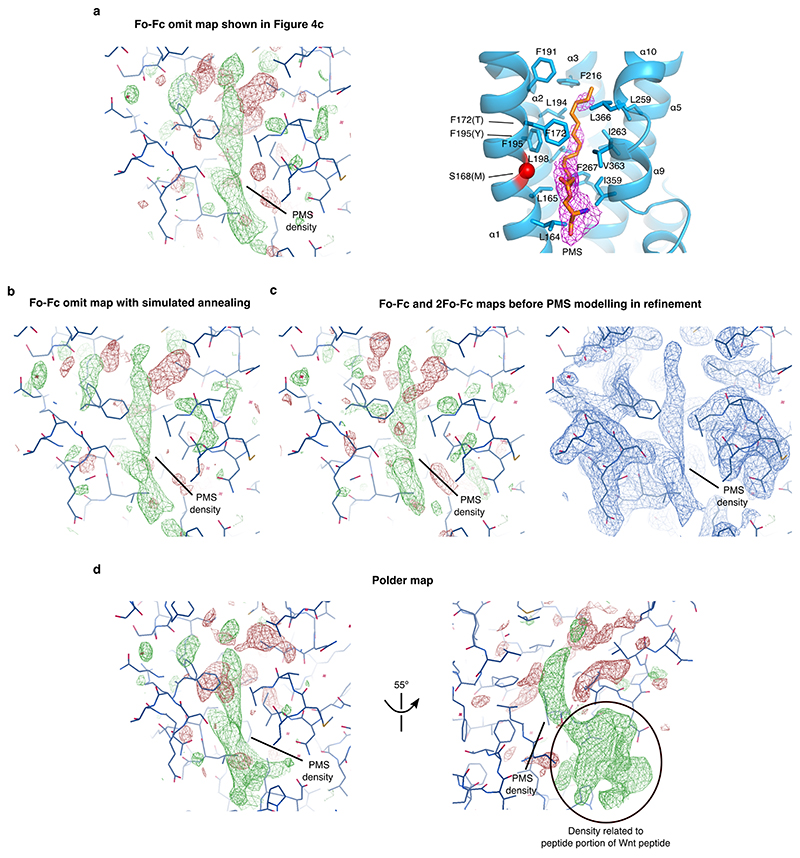

Extended Data Figure 8. Several types of omit maps show and support the modelling of the electron density in the binding pocket as palmitoleoylated serine (PMS) from the palmitoleoylated Wnt peptide.

a) Coot-displayed Fo-Fc omit map (left) generated from the refined model after removal of PMS, as shown in Figure 3c. To help orientation and comparison, panel c from Figure 3 is duplicated here, displaying the same map in Pymol (right). The maps are contoured at the same level in the two programmes (±2.5 σ). b) Coot-displayed Fo-Fc omit map (contoured at ±2.5 σ) generated from the refined model, after removal of PMS, application of simulated annealing and one round of coordinate and B-factor refinement. c) Coot-displayed Fo-Fc map (left) and 2Fo-Fc map (right) of the last refinement iteration before modelling PMS in the electron density. As PMS was never modelled, these maps are unbiased. The Fo-Fc map and 2Fo-Fc map are contoured at ±2.5 σ and 1 σ, respectively. d) Polder map generated from the refined model using phenix.polder35. This omit map, whose characteristic is to enhance weak electron density features in the omit region, shows additional electron density that can be assigned to the peptide portion of the palmitoleoylated peptide, therefore further supporting PMS modelling into the electron density. The map is contoured at ±2.5 σ.

Extended Data Figure 9. In vivo characterization of Dlp/Dally chimeras.

a) Multiple sequence alignment of residues forming binding pocket of human and Drosophila melanogaster glypicans. Sequences are coloured according to Clustal X colouring scheme (blue = hydrophobics; green = polar). b) Extracellular distribution upon overexpression of Dlp-HA, Dlp[F172T,F195Y]-HA, Dlp[R169E,T170N,Q171M,F172T]-HA or - Dally[E149R,N150T,M151Q,T152F]-HA with ptc-gal4. Scale bars represent 50μm. c) Model illustrating how Dlp acts both as a reservoir of signalling competent Wnt and as a co-receptor. The weight of these activities depends on the relative abundance of Dlp to Frizzled and on the relative affinities of Dlp and Frizzled for Wnt. Configuration of glypican core and HS chains are inspired from the structure of hGPC126. All molecules drawn approximately to scale. The HS chains are presented as orange circles, the glypican stalk regions from which they originate as black lines, and the GPI anchors as orange triangles.

Extended Data Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics (molecular replacement).

| Dlp-Wnt7a-peptide_complex | |

|---|---|

| PDB ID code | 6XTZ |

| Ligand code | 018 |

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 63.7, 77.4, 118.8 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 56.14-2.21 (2.25-2.21)* |

| R merge | 0.176 (2.026) |

| I/σI | 8(1.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) |

| Redundancy | 13.1 (11.2) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 56.14-2.21 |

| No. reflections | 30027(2687) |

| R work / R free | 0.2267/0.2553 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 3395 |

| Ligand/other | 23/46 |

| Water | 82 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 62.93 |

| Ligand | 78.40 |

| Water | 53.29 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.38 |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

The diffraction dataset was collected from a single crystal.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cyrille Alexandre for plasmids and advice, Joachim Kurth for Drosophila injections. Thomas Walter for technical support with crystallization, Weixian Lu and Yuguang Zhao for help with tissue culture and advice. We thank Karl Harlos and staff at Diamond Light Source beamlines (i03, i04 and i04-1) for assistance with x-ray data collection (proposal MX19946). This work was supported by core funding to the Francis Crick Institute to JPV (CRUK FC001204, MRC FC001204, and Wellcome Trust FC001204), the European Union (ERC grants WNTEXPORT (294523) to JPV, and CilDyn (647278) to CS), Cancer Research UK (C375/A17721 to EYJ, and C20724/A26752 to CS). LV is supported by Wellcome Trust PhD Training Programme 102164/B/13/Z. The Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics is supported by Wellcome Trust Centre grant 203141/Z/16/Z.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

METHODS are linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions

Experimental contributions were as follows: Drosophila developmental genetics and cell-based assays (IMcG), genetic analysis of LPPs (KB), biophysics and structural biology (LV, BB, TM, CS); peptide synthesis (DJ, NO’R). The project was conceived by IMcG, LV, EYJ, and JPV. The first draft of the paper was written by JPV, EYJ, IMcG, and LV. All the authors contributed to the design and interpretation of experiments.

Data Availability Statement

X-ray crystallographic coordinates and structure factor files generated during the current study are available from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), accession code 6XTZ. Full scans for all western blots are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Source Data behind Figs. 2 and 4 and Extended Data Figs. 1, 4–5 are available within the manuscript files.

References

- 1.Willert K, et al. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takada R, et al. Monounsaturated fatty acid modification of Wnt protein: its role in Wnt secretion. Dev Cell. 2006;11:791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janda CY, Waghray D, Levin AM, Thomas C, Garcia KC. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science. 2012;337:59–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1222879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panakova D, Sprong H, Marois E, Thiele C, Eaton S. Lipoprotein particles are required for Hedgehog and Wingless signalling. Nature. 2005;435:58–65. doi: 10.1038/nature03504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross JC, Chaudhary V, Bartscherer K, Boutros M. Active Wnt proteins are secreted on exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1036–1045. doi: 10.1038/ncb2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulligan KA, et al. Secreted Wingless-interacting molecule (Swim) promotes long-range signaling by maintaining Wingless solubility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:370–377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119197109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiecker C, Niehrs C. A morphogen gradient of Wnt/beta-catenin signalling regulates anteroposterior neural patterning in Xenopus. Development. 2001;128:4189–4201. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farin HF, et al. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem cell niche. Nature. 2016;530:340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature16937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexandre C, Baena-Lopez A, Vincent JP. Patterning and growth control by membrane-tethered Wingless. Nature. 2014;505:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature12879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian A, Duwadi D, Benchabane H, Ahmed Y. Essential long-range action of Wingless/Wnt in adult intestinal compartmentalization. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1008111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zecca M, Basler K, Struhl G. Direct and long-range action of a wingless morphogen gradient. Cell. 1996;87:833–844. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81991-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmansa S, Hamaratoglu F, Affolter M, Caussinus E. Dpp spreading is required for medial but not for lateral wing disc growth. Nature. 2015;527:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature15712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan D, Wu Y, Feng Y, Lin SC, Lin X. The core protein of glypican Dally-like determines its biphasic activity in wingless morphogen signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;17:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franch-Marro X, et al. Glypicans shunt the Wingless signal between local signalling and further transport. Development. 2005;132:659–666. doi: 10.1242/dev.01639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanganello E, et al. Filopodia-based Wnt transport during vertebrate tissue patterning. Nat Commun. 2015;6:5846. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baeg GH, Selva EM, Goodman RM, Dasgupta R, Perrimon N. The Wingless morphogen gradient is established by the cooperative action of Frizzled and Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan receptors. Dev Biol. 2004;276:89–100. doi: 10.1016/Jydbio.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reichsman F, Smith L, Cumberledge S. Glycosaminoglycans can modulate extracellular localization of the wingless protein and promote signal transduction. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:819–827. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baena-Lopez LA, Franch-Marro X, Vincent JP. Wingless promotes proliferative growth in a gradient-independent manner. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra60. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang X, et al. Roles of N-glycosylation and lipidation in Wg secretion and signaling. Dev Biol. 2012;364:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakugawa S, et al. Notum deacylates Wnt proteins to suppress signalling activity. Nature. 2015;519:187–192. doi: 10.1038/nature14259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuerer C, Habib SJ, Nusse R. A study on the interactions between heparan sulfate proteoglycans and Wnt proteins. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:184–190. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mihara E, et al. Active and water-soluble form of lipidated Wnt protein is maintained by a serum glycoprotein afamin/alpha-albumin. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.11621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim MS, Saunders AM, Hamaoka BY, Beachy PA, Leahy DJ. Structure of the protein core of the glypican Dally-like and localization of a region important for hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13112–13117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109877108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pei J, Grishin NV. Cysteine-rich domains related to Frizzled receptors and Hedgehog-interacting proteins. Protein Sci. 2012;21:1172–1184. doi: 10.1002/pro.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirai H, Matoba K, Mihara E, Arimori T, Takagi J. Crystal structure of a mammalian Wnt-frizzled complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2019;26:372–379. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0216-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awad W, et al. Structural Aspects of N-Glycosylations and the C-terminal Region in Human Glypican-1. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22991–23008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.660878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sivasankaran R, Calleja M, Morata G, Basler K. The Wingless target gene Dfz3 encodes a new member of the Drosophila Frizzled family. Mech Dev. 2000;91:427–431. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schilling S, Steiner S, Zimmerli D, Basler K. A regulatory receptor network directs the range and output of the Wingless signal. Development. 2014;141:2483–2493. doi: 10.1242/dev.108662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mii Y, Taira M. Secreted Frizzled-related proteins enhance the diffusion of Wnt ligands and expand their signalling range. Development. 2009;136:4083–4088. doi: 10.1242/dev.032524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashi Y, Kobayashi S, Nakato H. Drosophila glypicans regulate the germline stem cell niche. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:473–480. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Page-McCaw A. A matrix metalloproteinase mediates long-distance attenuation of stem cell proliferation. J Cell Biol. 2014;206:923–936. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201403084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serralbo O, Marcelle C. Migrating cells mediate long-range WNT signaling. Development. 2014;141:2057–2063. doi: 10.1242/dev.107656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez-Mendez L, Gradilla AC, Guerrero I. The cytoneme connection: direct long-distance signal transfer during development. Development. 2019;146 doi: 10.1242/dev.174607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Port F, Chen HM, Lee T, Bullock SL. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2967–2976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405500111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liebschner D, et al. Polder maps: improving OMIT maps by excluding bulk solvent. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2017;73:148–157. doi: 10.1107/S2059798316018210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elegheert J, et al. Lentiviral transduction of mammalian cells for fast, scalable and high-level production of soluble and membrane proteins. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:2991–3017. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: high-level expression of rhodopsin with restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation by a tetracycline-inducible N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative HEK293S stable mammalian cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aricescu AR, Lu W, Jones EY. A time-and cost-efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cells. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1243–1250. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906029799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang VT, et al. Glycoprotein structural genomics: solving the glycosylation problem. Structure. 2007;15:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter TS, et al. A procedure for setting up high-throughput nanolitre crystallization experiments. Crystallization workflow for initial screening, automated storage, imaging and optimization. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:651–657. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905007808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newman J. Novel buffer systems for macromolecular crystallization. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:610–612. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903029640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winter G, Lobley CM, Prince SM. Decision making in xia2. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:1260–1273. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913015308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winter G, et al. DIALS: implementation and evaluation of a new integration package. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2018;74:85–97. doi: 10.1107/S2059798317017235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]