Abstract

Snakebite is a neglected tropical disease that inflicts severe socioeconomic burden on developing countries by primarily affecting their rural agrarian populations. India is a major snakebite hotspot in the world, as it accounts for more than 58,000 annual snakebite mortalities and over three times that number of morbidities. The only available treatment for snakebite is a commercially marketed polyvalent antivenom, which is manufactured exclusively against the ‘big four’ Indian snakes. In this review, we highlight the influence of ecology and evolution in driving inter- and intra-specific venom variations in snakes. We describe the repercussions of this molecular variation on the effectiveness of the current generation Indian antivenoms in mitigating snakebite pathologies. We highlight the disturbing deficiencies of the conventional animal-derived antivenoms, and review next-generation recombinant antivenoms and other promising therapies for the efficacious treatment of this disease.

Keywords: Antivenom, Evolution, Proteomics, Venom

V enom is a complex biochemical concoction that is contrasted from poisons in being actively injected by the producing animal into the target prey or predator. Given their medical importance, snake venoms have fascinated humans since time immemorial, and have been extensively studied to date. Animal venoms can be chemically constituted by proteins, amino acids, carbohydrates, salts, and polyamines [1]. Snake venoms, however, are primarily proteinaceous. Historically, an anthropocentric bias has led to an erroneous understanding that only animals capable of inflicting medically significant envenomation are ‘venomous’. However, venoms represent an evolutionary adaptation for self-defense and prey capture. Therefore, venom may attain remarkable specificity towards target animals and become ineffective against non-target species. For instance, certain venom toxins in arboreal ‘tree snakes’ (e.g., genus Boiga) exhibit extreme potency towards their avian and reptilian prey, while exhibiting reduced effectiveness against mammals, including humans. The potency and composition of snake venom cocktails are driven by diverse factors, such as varying diet (e.g., ontogenetic dietary shifts), geographical distribution and environmental conditions [2,3].

A Million Deaths

Despite being the non-target species, accidental snake envenoming in humans has resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths and disabilities worldwide. Snake envenoming affects between 4.5 to 5.4 million people globally, inflicting over 100,000 deaths and 400,000 disabilities, annually [4]. Tragically, India accounts for 58,000 snakebite deaths and three-times as many immutable morbidities, making it a major snakebite hotspot [5]. Snakebite disproportionately affects the impoverished rural populations that often lack essential health infrastructure. As most bite victims are the primary breadwinners of their families, snakebite devastates far greater numbers of lives and livelihoods than currently recognized. Although snakebites kill nearly as many people in India as HIV infections, they only receive a fraction of the research attention and medical investment devoted to HIV. Since snakebite primarily affects the poor, and young males are at the highest risk of getting bitten, it results in severe socioeconomic consequences in developing countries. These considerations have led to the enlisting of snake envenoming as a high priority ‘neglected tropical disease’ (NTD) by the World Health Organization (WHO) [4].

Venoms to Drugs

On the flip side, snake venoms have saved many more lives than they have taken. Millions of years of evolution has resulted in diverse snake venom toxins with remarkable target specificities, and this property is being extensively exploited for drug discovery. Many snake venom proteins have been engineered into highly specific and efficient lifesaving drugs. For instance, Captopril, an angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitor used for the treatment of hypertension, is derived from the venom of the Brazilian pit viper, Bothrops jararaca, and has become the poster child for drug discovery from snake venoms. This exceptional drug has saved millions of lives globally since its introduction in the early 1980s. Many other snake venom-derived therapeutics for the treatment of various diseases, including multiple sclerosis, thrombosis, and cardiovascular diseases, are under various phases of clinical trials [6].

Clinical Consequences of Venom Variation

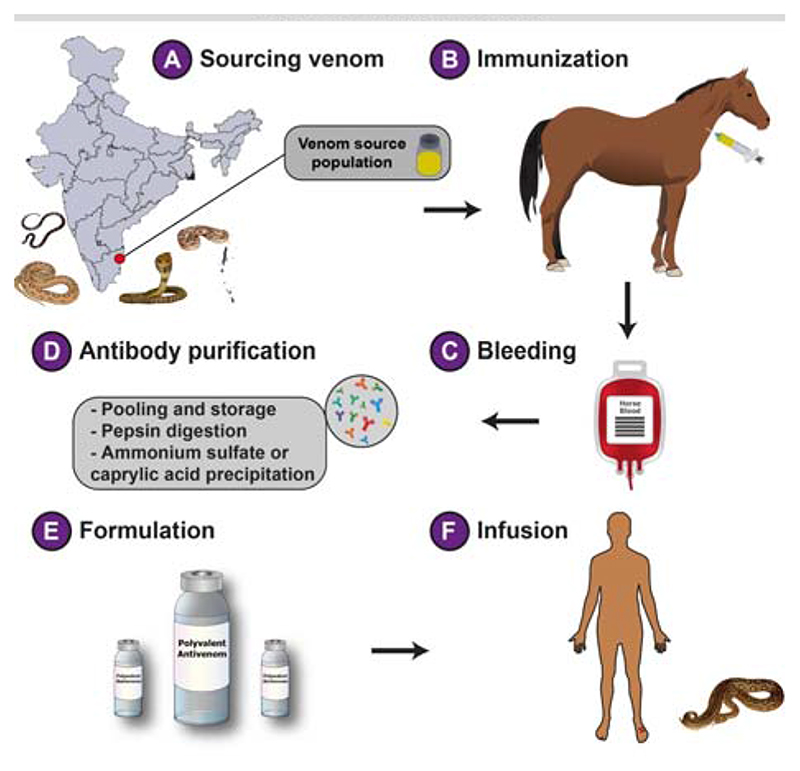

Antivenom is the mainstay treatment of snakebite, whose manufacturing protocols have remained essentially unchanged since their inception in the late 1800s: purification of immunoglobulins (IgG) from horses hyperimmunized with sublethal and subtoxic doses of snake venom (Fig. 1). The efficacy of conventional antivenom is restricted to the immunogenic potential of venoms used in its manufacture. Since venom is an adaptive trait that underpins various quotidian functions, it often exhibits dramatic inter-(between) and intraspecific (within species) variability. This variation may result in very distinct clinical outcomes and, thus, severely limits the cross-population/species antivenom efficacy – i.e., treatment of snakebites of one population/ species using antivenom raised for another. However, for the commercial production of Indian antivenoms, venoms are exclusively sourced in Tamil Nadu from the so-called ‘big four’ snakes: the spectacled cobra (Naja naja), common krait (Bungarus caeruleus), Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii), and saw-scaled viper (Echis carinatus). Moreover, India is abode to many other medically important snake species capable of inflicting fatalities and morbidities in their accidental human bite victims. Northeast India, for example, is devoid of the ‘big four’ snakes, but is dominated by other medically important snake species. Unfortunately, however, a single polyvalent antivenom manufactured for treating bites from the ‘big four’ snakes is marketed throughout the country, including in regions that lack these species. As Indian antivenoms fail to account for the inter- and intraspecific variability in venoms, they are preclinically shown to be less effective in mitigating bites from the pan-Indian populations of both ‘big four’ snakes and the ‘neglected many’, medically important snakes for which antivenoms are not manufactured [7,8].

Fig. 1. The production of conventional Indian antivenoms.

The manufacturing process of Indian antivenoms involves a) sourcing of venoms from the ‘big four ‘ snakes in a couple of districts in Tamil Nadu, followed by b) the immunization of healthy equines with these venoms in sublethal and subtoxic doses; c) immunized equines are then bled and the plasma is separated from the blood. The processed blood without plasma is mixed with saline and often reintroduced into the immunized animal; d) The serum is first digested with pepsin to cleave off immunoglobulin heavy chains, resulting in divalent F(ab’)2 fragments, followed by the treatment with ammonium sulfate or caprylic acid to precipitate antibodies, and ultracentrifugation of the precipitate to obtain purified antibodies; e) The purified antivenom is formulated either in liquid or lyophilized form before being marketed for f) the treatment of snakebite victims.

Disturbing Deficiencies of Antivenom

Hyperimmunization of animals with crude ‘whole’ venoms, which often contain antigens and other impurities, is the major shortcoming of the conventional antiserum therapy, as it increases the amount of contaminant antibodies in the finished product. In fact, the proportion of therapeutically relevant antibodies in an antivenom vial may be lower than 10-15% of the content [9], necessitating the requirement of a considerably large number of vials for efficacious treatment. This, in turn, increases the cost of treatment to the point that it becomes unaffordable to many in low- and middle-income countries. Fortunately, Indian antivenoms are heavily subsidized by the government and are freely administered without charges in government hospitals. Infusion of substantial amounts of therapeutically redundant antivenom; however, leads to complications, including serum sickness and the fatal anaphylactic shock. It is, therefore, not surprising that nearly 80% of snakebite victims who were treated with the Indian antivenoms were found to exhibit multiple adverse effects [10]. This highlights the pressing need to increase the dose effectiveness of currently available commercial antivenoms in the country.

In addition to the low dose efficacy, the poor cross-species/population neutralization capability are the other major deficiencies of the commercial Indian antivenoms. The marketed antivenoms, which are manufactured exclusively against the ‘big four’ snake venoms from a couple of districts in Tamil Nadu, have been shown to poorly mitigate the toxic effects inflicted by the geographically disparate populations of the ‘big four’ snakes and the ‘neglected many’ [7,8]. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of commercial Indian antivenoms has been largely evaluated by in vitro methods [e.g., enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), western blotting and immunochromatography (Web Table I)]. In contrast to in vivo experiments in the mouse model (e.g., Effective Dose 50 or ED50), in vitro methods do not reveal the underlying neutralization potencies of antivenoms, but are only useful for understanding their venom recognition potential. Furthermore, low-molecular-weight toxins, such as three-finger toxins (3FTx), which dominate the venoms of many elapid snakes (e.g., Naja and Bungarus spp.) and are responsible for the morbid and fatal symptoms, exhibit poor immunogenicity, likely leading to a reduced proportion of neutralizing antibodies against them [22].

Web Table I. Efficacy of Marketed Indian Antivenoms.

| Snake Species | Venom source | Antivenom tested | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. naja, N. kaouthia | West Bengal” [11] | S | In vitro: NA In vivo: Antivenom is more effective against N. naja than N. kaouthia. The former venom was more potent than that ofN. kaouthia. |

| N. naja | West Bengal,e Maharashtra,c Tamil Nadud [12] | M (prepared against venom from Eastern India) | In vitro: Poor recognition of venoms from Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. In vivo: NA |

| N. naja | West Bengal,e Tamil Nadud Maharashtrac [8] | H, M | In vitro: Specific monovalent antivenoms neutralized many enzymatic activities In vivo: Specific monovalent antivenoms outperformed the commercial antivenom |

| N. naja | Tamil Nadud [13] | VI, C-V1 | In vitro: NA In vivo: Soy protein nanoparticle conjugated antivenom was more effective than the commercia antivenom. |

| N. naja | Maharashtrac [14] | B, P, V | In vitro: Poor immunorecognition of low molecular weight toxins In vivo: NA |

| D. russelii | Delhia West Bengal,e Maharashtra,c Tamil Nadu [15] | M (prepared against venom from Southern India) | In vitro: Poor recognition of venoms from Delhi, West Bengal and Maharashtra In vivo: NA |

| D. russelii | Tamil Nadu,d Kerala,b Karnataka,West Bengale [16] | B | In vitro: Poor recognition of venoms of West Bengal and Kerala populations In vivo: NA |

| D. russelii | Tamil Nadud [17] | B, P, V,BE | In vitro: Poor recognition of low molecular weight toxins In vivo: NA |

| D. russelii | Tamil Nadu,d Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka [18] | I, H, VI, BE, P, ICP | In vitro: Efficient immunorecognition of venoms of Tamil Nadu, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh In vivo: NA for venom from Tamil Nadu |

| E. carinatus | Tamil Nadud [19] | B, P, V | In vitro: Poor recognition of low molecular weight toxins In vivo: NA |

| B. caeruleus | Tamil Nadud [20] | B, P, BE | In vitro: NA Poor recognition of low molecular weight toxins In vivo: NA |

| B. caeruleus, B. sindanus, B. romulusi | Maharashtra and Karnataka [21] | H, P | In vitro: Poor recognition of low molecular weight toxins In vivo: Antivenom ineffective in neutralizing the venoms of B. sindanus and B. romulusi |

| B. caeruleus, B. sindanus, B. fasciatus, N. naja, N. kaouthia, E. carniatus, E. c. sochureki | Punjab, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Arunachal Pradesh, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh [7] | B, P, H, VI | In vitro: Poor recognition of venoms of the ‘neglected many’ species, as well as one of the ‘big four’ snake venoms In vivo: Antivenom ineffective in neutralizing the venoms of B. caeruleus and the ‘neglected many’ species except one, while neutralizing E. carniatus, E. c. sochureki and N. naja venoms |

B: BSVL (Bharat Serums and Vaccines Ltd.); BE: Biological E. Limited; H: Haffkine Biopharmaceuticals Corporation Ltd.; M: monovalent antivenom raised in the study; C-VI: nanoparticle conjugated with VINSASV; S: SIIPL (Serum Institute of India Pvt. Ltd.); P: PSVPL (Premium Serums and Vaccines Pvt. Ltd.); VI: VINS Bioproducts Ltd.; V: Virchow Biotech; I: Incepta Vaccine Ltd. (Dhaka, Bangladesh); ICP: Instituto Clodomiro Picado (San Jose, Costa Rica); NA: data not available/notperformed. aChest Institute; bAgadathantra Snake Park; cHaffkine Institute; dIrula Snake Catchers’ Industrial Cooperative Society; eCalcutta Snake Park.

Upcoming Therapies for Snakebites

To date, hyperimmunized animal-derived antivenom remains the only available treatment for snakebites. The inefficacy of such antivenoms in neutralizing the toxic effects of distinct medically important species and their geographically disparate populations have been well-documented. In recent times, several innovative strategies are being explored to develop next-generation antivenoms with increased potency, paraspecificity, and cost-effectiveness. Some of these strategies have been briefly described below.

Phage display

It facilitates the identification of antibodies specific to toxins of interest. Phage display essentially involves biopanning of antibody phage display libraries against a particular antigen, in this case, venom proteins, followed by the amplification and enrichment of the antigen-specific library. Selected phages are used for infecting bacteria, which are then allowed to express toxin-specific antibody fragments. Specific antibodies against various toxin types can also be combined to form a biosynthetic oligoclonal antibody (BOA) cocktail, which exhibits less batch-to-batch variation and increased efficacy and safety profiles than the conventional antivenoms [23]. Phage display technology has been shown to be effective in characterizing antibodies against medically important snake venom toxins, including crotoxin, cobratoxin, and dendrotoxin [24].

Synthetic epitope strategy

Next-generation antivenoms containing toxin-specific antibodies could also be produced through novel immunization strategies, such as immunization with synthetic epitope-strings. Herein, strings of nucleotide sequences coding for specific regions of various toxins are cloned into expression vectors and injected into animals for eliciting toxinspecific antibody response [25].

Aptamers

The use of aptamers, oligonucleotides or oligopeptides that bind to target molecules with high specificity, have also been considered for the development of novel antivenom therapies [26]. This strategy can be advantageous over animal-derived antibodies in terms of production, affordability, and ethical considerations.

Mimotopes

Structurally mimicking regions of clinically important toxins known as ‘mimotopes’ can elicit immune responses and generate toxin-specific antibodies. Examples include mutalysin-II mimotopes that have been shown to neutralize hemorrhagic activity induced by Lachesis muta venom [27]. These mimotopes are usually identified from a phage display library and have high specificity and stability.

Nanoparticle engineering

Another alternative to the current intravenous antivenom administration is the subcutaneous use of nanoparticle drug delivery systems that can facilitate the controlled release of highly stable toxin neutralizing nanoparticles. Synthetic hydrogel nanoparticles, for example, have been shown to inhibit phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and 3FTx pathologies [28,29]. Similarly, nanoparticles, such as C60 fullerene, have been shown to exhibit significant neutralization against rattlesnake envenomation [30].

In addition, several small molecular inhibitors, such as varespladib are currently being tested for their ability to neutralize snakebite pathologies [28]. Unfortunatel, very few products originating from these next-generation technologies are under various phases of clinical trials, while most others are being preclinically evaluated. Thus, while the aforementioned technologies are promising and are likely to result in highly efficacious and affordable snakebite treatment therapies, they are far from fruition. It is therefore imperative, in the interim, to address the deficiencies of the current generation Indian antivenoms. Procurement of venoms from the pan-Indian populations of ‘big four’ and other medically important snakes by region for the production of region-specific antivenoms, while also accounting for the ecological specializations and molecular evolutionary dynamics of venoms of clinically relevant species, could be effective in countering the geographic and phyletic variations in venom compositions and potencies. Furthermore, adoption of novel immunization strategies (e.g., the use of medically important toxin fractions and/or poor immunogenic toxin proteins for animal immunization) and purification technologies (e.g., chromatographic purification of antivenoms during manufacture) are highly likely to increase the proportion of therapeutically significant antibodies in the marketed product. Thus, in the absence of next-generation antivenoms, these measures are anticipated to save the lives, limbs and livelihoods of India’s hundred thousand annual snakebite victims.

Summary.

The rapid SARS-Cov-2 antigen test (SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Test (Roche Diagnostics), was compared in symptomatic patients with PCR testing both in emergency departments and primary health care centres. It showed an overall sensitivity of 80.3% and specificity of 99.1%; these were higher with lower PCR cycle threshold numbers and with a shorter onset of symptoms.

Acknowledgements

RR Senji Laxme and Suyog Khochare (Evolutionary Venomics Lab, IISc) for their inputs.

Funding

KS: Department of Science and Technology (DST) INSPIRE Faculty Award, DST-FIST, DBT-IISc Partnership Program, and the DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Fellowship.

Footnotes

Contributors:

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Competing interest:

None stated.

References

- 1.Sunagar K, Casewell N, Varma S, Kolla R, Antunes A, Moran Y. Venom Genomics and Proteomics. Springer; 2014. Deadly innovations: Unraveling the molecular evolution of animal venoms; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suranse V, Iyer A, Jackson T, Sunagar K. Early origin and diversification of the enigmatic reptilian venom cocktail. Systematic Association Special Volume. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casewell NR, Jackson TN, Laustsen AH, Sunagar K. Causes and consequences of snake venom variation. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutierrez JM, Calvete JJ, Habib AG, Harrison RA, Williams DJ, Warrell DA. Snakebite envenoming. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17063. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suraweera W, Warrell D, Whitaker R, Menon GR, Rodrigues R, Fu SH, Begum R, Sati P, Piyasena K, Bhatia M, Brown P. Trends in snakebite mortality in India from 2000 to 2019 in a nationally representative mortality study. medRxiv. 2020 Jan 1; doi: 10.7554/eLife.54076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohamed Abd El-Aziz T, Soares AG, Stockand JD. Snake venoms in drug discovery: valuable therapeutic tools for life saving. Toxins (Basel) 2019;11:564. doi: 10.3390/toxins11100564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laxme RS, Khochare S, de Souza HF, et al. Beyond the ‘big four’: Venom profiling of the medically important yet neglected Indian snakes reveals disturbing antivenom deficiencies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shashidharamurthy R, Kemparaju K. Region-specific neutralization of Indian cobraNaja najavenom by polyclonal antibody raised against the eastern regional venom: A comparative study of the venoms from three different geographical distributions. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casewell NR, Cook DA, Wagstaff SC, et al. Pre-clinical assays predict pan-African Echis viper efficacy for a species-specific antivenom. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ariaratnam CA, Sjostrom L, Raziek Z, et al. An open, randomized comparative trial of two antivenoms for the treatment of envenoming by Sri Lankan Russell’s viper (Daboia russeliirusselii) . Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:74–80. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukherjee AK, Maity CR. Biochemical composition, lethality and pathophysiology of venom from two cobras - Naja naja and N. kaouthia . Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;131:125–32. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shashidharamurthy R, Jagadeesha DK, Girish KS, Kemparaju K. Variations in biochemical and pharmacological properties of Indian cobra (Naja naja naja)venom due to geographical distribution. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;229:93–101. doi: 10.1023/a:1017972511272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadali R, Kadiyala G, Gurunathan J. Pre clinical assessment of the effectiveness of modified polyvalent antivenom in the neutralization of Naja naja venom toxicity. Biotechnol Appl Bioc. 2016;63:827–33. doi: 10.1002/bab.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chanda A, Kalita B, Patra A, Senevirathne WDST, Mukherjee AK. Proteomic analysis and antivenomics study of Western India Naja naja venom: correlation between venom composition and clinical manifestations of cobra bite in this region. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2019;16:171–84. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2019.1559735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasad NB, Uma B, Bhatt SK, Gowda VT. Comparative characterisation of Russell’s viper (Daboia/Vipera russelli) venoms from different regions of the Indian peninsula. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1428:121–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma M, Gogoi N, Dhananjaya B, Menon JC, Doley R. Geographical variation of Indian Russell’s viper venom and neutralization of its coagulopathy by polyvalent antivenom. Toxin Reviews. 2014;33:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalita B, Singh S, Patra A, Mukherjee AK. Quantitative proteomic analysis and antivenom study revealing that neurotoxic phospholipase A2 enzymes, the major toxin class of Russell’s viper venom from southern India, shows the least immuno-recognition and neutralization by commercial polyvalent antivenom. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;118:375–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pla D, Sanz L, Quesada-Bernat S, et al. Phylovenomics of Daboia russelii across the Indian subcontinent. Bioactivities and comparative in vivo neutralization and in vitro third-generation antivenomics of antivenoms against venoms from India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. J Proteom. 2019;207:103443. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.103443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patra A, Kalita B, Chanda A, Mukherjee AK. Proteomics and antivenomics of Echis carinatus carinatus venom: Correlation with pharmacological properties and pathophysiology of envenomation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patra A, Chanda A, Mukherjee AK. Quantitative proteomic analysis of venom from Southern India common krait Bungarus caeruleus and identification of poorly immunogenic toxins by immune-profiling against commercial antivenom. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2019;16:457–69. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2019.1609945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunagar K, Khochare S, Laxme RS, et al. A wolf in another wolf’s clothing: Post-genomic regulation dictates venom profiles of medically-important cryptic kraits in India [preprint] bioRxiv. 2020:12.15.422536. doi: 10.3390/toxins13010069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández J, Alape-Girón A, Angulo Y, et al. Venomic and antivenomic analyses of the Central American coral snake,Micrurus nigrocinctus(Elapidae) J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1816–27. doi: 10.1021/pr101091a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kini RM, Sidhu SS, Laustsen AH. Biosynthetic oligoclonal antivenom (boa) for snakebite and next-generation treatments for snakebite victims. Toxins. 2018;10:534. doi: 10.3390/toxins10120534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulkeaw K, Sakolvaree Y, Srimanote P, et al. Human monoclonal ScFv neutralize lethal Thai cobra,Naja kaouthianeurotoxin. J Proteomics. 2009;72:270–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira RN, Machado de Avila RA, Sanchez EF, et al. Antibodies against synthetic epitopes inhibit the enzymatic activity of mutalysin II, a metalloproteinase from bushmaster snake venom. Toxicon. 2006;48:1098–103. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye F, Zheng Y, Wang X, et al. Recognition ofBungarus multicinctus venom by a DNA aptamer against beta-bungarotoxin. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machado de Avila RA, Stransky S, Velloso M, et al. Mimotopes of mutalysin-II fromLachesis mutasnake venom induce hemorrhage inhibitory antibodies upon vaccination of rabbits. Peptides. 2011;32:1640–6. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewin M, Samuel S, Merkel J, Bickler P. Varespladib (LY315920) appears to be a potent, broad-spectrum, inhibitor of snake venom phospholipase A2 and a possible pre-referral treatment for envenomation. Toxins. 2016;8:248. doi: 10.3390/toxins8090248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Brien J, Lee SH, Gutierrez JM, Shea KJ. Engineered nanoparticles bind elapid snake venom toxins and inhibit venom-induced dermonecrosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karain BD, Lee MKH, Hayes WK. C60 Fullerenes as a novel treatment for poisoning and envenomation: A proof-of-concept study for snakebite. J Nanosci Nanotech. 2016;16:7764–71. [Google Scholar]